Abstract

Gene conversions occur when genomic double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) trigger unidirectional transfer of genetic material from a homologous template sequence. Exogenous or mutated sequence can be introduced through this homology-directed repair (HDR). We leveraged gene conversion to develop a method for genomic editing of existing transgenic insertions in Drosophila melanogaster. The clustered regularly-interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 system is used in the homology assisted CRISPR knock-in (HACK) method to induce DSBs in a GAL4 transgene, which is repaired by a single-genomic transgenic construct containing GAL4 homologous sequences flanking a T2A-QF2 cassette. With two crosses, this technique converts existing GAL4 lines, including enhancer traps, into functional QF2 expressing lines. We used HACK to convert the most commonly-used GAL4 lines (labeling tissues such as neurons, fat, glia, muscle, and hemocytes) to QF2 lines. We also identified regions of the genome that exhibited differential efficiencies of HDR. The HACK technique is robust and readily adaptable for targeting and replacement of other genomic sequences, and could be a useful approach to repurpose existing transgenes as new genetic reagents become available.

Keywords: gene conversion, CRISPR/Cas9, homology-directed repair, genomic engineering, updating transgenes

DOUBLE-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) in genomic DNA are potentially lethal to the cell as they are substrates for genomic rearrangements. Two major endogenous repair mechanisms exist to resolve such DNA damage. Nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) involves ligation of the damaged ends and often results in small insertion/deletion (indel) mutations at the site of the DSB (Lieber 2010). This causes frameshifting and the expression of mutated or nonfunctional protein. In contrast, homologous recombination (HR) uses a homologous template for repair to preserve genomic integrity. Gene conversion is one form of HR and involves unidirectional transfer of genetic material from a donor sequence to a highly homologous target (Engels et al. 1990; Gloor et al. 1991; Chen et al. 2007). Donors can be from the sister chromosome (allelic gene conversion) or dispersed sequences not at the same locus (ectopic gene conversion).

Current genomic engineering methods use a DSB induced at a target genomic locus to generate disrupting mutations, driven by NHEJ, or to introduce new genetic sequences, driven by homology-directed repair (HDR). Several techniques have been developed to introduce target-specific DSBs, including zinc-finger nucleases, transcription-activator-like effecter nucleases, and, most recently, clustered regularly-interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR) (Jinek et al. 2012; Doudna and Sontheimer 2014). Cas9 is the endonuclease of the type II CRISPR system and creates a DSB at genomic locations directed by a guide RNA (gRNA). The CRISPR/Cas9 system is favored for its high efficiency and ability to use a small gRNA to specifically target most genomic DNA locations (Cong et al. 2013; Hsu et al. 2013).

Genomic engineering methods for investigating biological questions are often complemented by the use of transgenic manipulations. The development of binary expression systems in Drosophila has allowed for the precise manipulation of specific cell types. A binary expression system consists of two components: an exogenous transcription factor [e.g., GAL4 (Brand and Perrimon 1993), QF (Potter et al. 2010; Riabinina et al. 2015), and LexAVP16 (Lai and Lee 2006)] that is expressed in a specific pattern, and an effecter gene under the regulatory control of the exogenous transcription factor (DNA sequences: UAS, QUAS, and LexAOP, respectively). Currently, two methods are used to generate most driver lines. In the first approach, enhancer trap lines are generated by random insertion of a transposable element carrying a minimal promoter and the exogenous transcription factor (e.g., GAL4) into the genome (Brand and Perrimon 1993; Ito et al. 1997; Yoshihara and Ito 2000). The transgene is able to capture expression patterns induced by its inserted genomic location. This is a useful approach, as it does not require the enhancer regions driving expression to be characterized, nor that these enhancer regions be within a small genomic region. However, generating enhancer trap lines can require labor-intensive in vivo screens to identify expression patterns of interest. A second systematic approach uses defined sizes of 5′ regulatory regions to generate transgenic binary expression libraries. The Janelia Research GAL4 collection uses short elements of genomic DNA (∼3 kb) as potential enhancer elements, and inserts expression constructs at the same site in the genome by PhiC31 integration [GMR-GAL4 lines (Pfeiffer et al. 2008; Jenett et al. 2012)]. The expression patterns of the GMR lines are well defined (Jenett et al. 2012). To date, >10,000 enhancer trap GAL4 lines and 7000 GMR-GAL4 lines have been generated. Many GAL4 enhancer traps are recognized as representatives for different tissues (e.g., elav-GAL4 is a marker for neurons and repo-GAL4 is a marker for glia).

Complex tissues, such as the nervous system, often require the use of two binary expression systems to drive intersectional expression patterns or to examine interactions between cells (Potter et al. 2010). However, unlike GAL4, relatively few QF or LexAVP16 lines have been generated. Several methods have been developed to swap transcription factor drivers between transgenic binary expression systems. However, this requires either de novo generation of new driver lines [integrase swappable in vivo targeting element (InSITE)] (Gohl et al. 2011) or PhiC31-induced insertion of a transcription factor cassette into an existing minos mediated integration cassette (MiMIC) genomic insertion (Venken et al. 2011; Diao et al. 2015; Gnerer et al. 2015).

Here, we developed a method that converts existing transgenic GAL4 lines into QF2 lines with two simple genetic crosses. This method uses the CRISPR/Cas9 system to induce DSBs in transgenic GAL4, and HDR to drive conversion of GAL4 into a QF2-expressing line through the use of a single transgenic donor cassette in the genome. A total of >20 commonly-requested GAL4 lines (e.g., tubP-GAL4, elav-GAL4, repo-GAL4, D42-GAL4, and Mef2-GAL4) distributed across the genome were successfully converted into QF2 lines. The expression patterns of the converted lines ranged from pan-cellular, neuron, glia, muscle, hemocyte, to adipose tissue. The QF2 donor and the GAL4 target could be either on the same or different chromosomes (trans-chromosomal). We found that conversion frequency was influenced by the chromosomal locations and the relative orientations of donor and target. Targets at some cytological locations exhibited generally high conversion rates (“hot” spots), while others were rarely converted (“cold” spots). Our method introduces a quick and easy approach to target existing GAL4 lines, and eliminates the necessity for expensive injections or time-consuming repetitive cloning. The approach can be adapted for similar targeting or conversion of other genetic elements (such as GAL80, split-GAL4, LexA, FLPase, and GFP). We named this method homology assisted CRISPR knock-in or HACK.

Materials and Methods

Construction of the QF2G4H HACK vector

To generate a versatile construct with multiple synthetic components, we de novo designed the donor vector for DNA synthesis (DNA2.0, Newark, CA). The construct contains 5′ and 3′ P-element sequences, attB sequence, T2A, origin of replication, and ampicillin resistance sequence. 3xP3-RFP flanked with LoxP sites was PCR amplified from pXL-BACII-LoxP-3xP-RFP-LoxP (Addgene #26852; C. J. Potter, unpublished vector) to serve as the marker for the construct. QF2 and hsp70 terminator were PCR amplified from pQF2WB (Addgene #61312; Riabinina et al. 2015). The two empty tandem gRNAs driven by U6:1 and U6:3 promoters were PCR amplified from pCFD4-U6:1_U6:3 (Addgene #49411; Port et al. 2014). We named the backbone construct pHACK-QF2 (Addgene #80274).

The manufacture of the QF2G4H HACK donor construct required two steps. First was the selection of the gRNAs to generate DSBs in GAL4. Two gRNAs targeting the GAL4 middle region were designed through an online program (http://flycrispr.molbio.wisc.edu/tools) (Gratz et al. 2014) and cloned into pHACK-QF2 through BbsI sites. We targeted 120 bp of sequence in the middle of GAL4. Selection criteria for the gRNA included no off-targets in the Drosophila genome and generation of roughly equal 5′ and 3′ homology sequences. Next, 5′ truncated homology GAL4 (1182 bp) and 3′ truncated homology GAL4 (1368 bp) sequences not including the gRNA targeted sequences were cloned through the MluI and SpeI sites. Flanking FRT sites between 5′ and 3′ homology arms and one I-SceI site upstream of the 5′ homology arm were included in case the donor cassette needed to be excised and linearized for efficient conversion (Supplemental Material, Figure S2) (Rong and Golic 2000). This proved unnecessary and was not experimentally tested for conversion. The final construct was named pHACK-G4 > QF2 (Addgene #80275). The constructs were sent to Rainbow Transgenic Flies (Camarillo, CA) for injections for random P-element insertion or PhiC-31 site-specific integration at the attP2 site. In-Fusion cloning was used for all the cloning steps (Clontech Laboratories). The attP2 QF2G4H donor line was verified to integrate correctly into the attP2 locus by using primers annealing to the genomic DNA sequence upstream of P2 and the other to the donor sequence (Figure S7D).

gRNA candidates used to target GAL4 sequence (PAM sequence underlined) (http://flycrispr.molbio.wisc.edu/tools):

G4_gRNA1 GATGTGCAGCGTACCACAACAGG

G4_gRNA2 TGTATTCTGAGAAAGCTGGATGG

gRNA primers to clone into pHACK-QF2:

G4_gRNA-FOR TCCGGGTGAACTTCGATGTGCAGCGTACCACAACGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAGTTA

G4_gRNA-REV TTCTAGCTCTAAAACTCCAGCTTTCTCAGAATACACGACGTTAAATTGAAAATAGGTC

Primers for 5′ homology arm (5′ homology was cloned into pHACK-QF2 through MluI site and synthetic I-SceI and FRT sequence was added into BglII site):

H1-BglII-BamHI-FOR CCCTTACGTAACGCGagatctggatccATGAAGCTACTGTCTTCTATCGAA

H1-BamHI-REV CGCGGCCCTCACGCGaggatccAAGCAGGGACAATTGGATCT

H1-I-SceI-FRT ACGTAACGCGAGATCtGAAGTTCCTATTCTCTAGAAAGTATAGGAACTTCTAGGGATAACAGGGTAATaGATCTGGATCCATGA

Primers designed for 3′ homology arm (3′ homology with FRT sequence in the reverse primer was cloned into pHACK-QF2 through SpeI site):

H2-SpeI-FOR GTTATAGATCACTAGtCATGGCATCATTGAAACAG

H2-SpeI-FRT-REV AATTCAGATCACTAGAAGTTCCTATACTTTCTAGAGAATAGGAACTTCactagtCTATTACTCTTTTTTTGGGTTTG

PCR primers used for verification of HDR and indel mutation:

pGaw2 CAGATAGATTGGCTTCAGTGGAGACTG

GAL4-mdg3_genomic_FOR1 GCGTTTGGAATCACTACAGGG

GAL4_FOR2 GCACTCACCGACGCTAATGATG

PCR verification of the location of pHACK_G4 > QF2 at the P2 site:

A2_3L_REV CTCTTTGCAAGGCATTACATCTG

Pry#4 CAATCATATCGCTGTCTCACTCA

The Cas9 gRNAs directed highly efficient targeting of GAL4 sequences (Figure S7 and Figure S8). The gRNAs were chosen using the “high stringency” algorithm to have no predicted off-targets in the Drosophila genome (http://tools.flycrispr.molbio.wisc.edu/targetFinder/index.php) (Gratz et al. 2014). However, the “maximum stringency” algorithm identified two predicted off-target sites for gRNA1, and three predicted off-target sites for gRNA2. We examined if these predicted off-target sites contained HACK-induced mutations by PCR amplifying the genomic DNA of two fly stocks containing Cas9 endonuclease and gRNAs combined for at least six generations [Act5C-Cas9; QF2G4-HACK (57C1) and Act5C-Cas9; ;QF2G4-HACK (70F4)]. This would allow sufficient opportunities for any Cas9/gRNA-mediated indel mutations to accumulate in germline or somatic tissues. The sizes of the PCR products were indistinguishable from those of the control (Act5C-Cas9) (Figure S11). Furthermore, sequencing of the PCR products revealed no mutations (n = 10). These results suggest that endogenous genomic loci are unlikely to be targeted by GAL4 gRNAs used by the HACK method.

Primers for potential off-target sites generated by gRNA1:

gRNA1_OT1F AACAACCCATCAGGACGAGC

gRNA1_OT1R AAAACGGCTGGCTTAGTTGC

gRNA1_OT2F TTGATCGTTTGGGTTTGTGC

gRNA1_OT2R GCTCTTGCACCCAGGAAAAG

Primers for potential off-target sites generated by gRNA2:

gRNA2_OT1F TCGCTCATGGTAAATGGTGC

gRNA2_OT1R TTAACGGCATGATCCTGTGC

gRNA2_OT2F ATGAGACTAGCCGAAAGGCG

gRNA2_OT2R TGGGCCTCTTCAATGTTTCC

gRNA2_OT3F TCATTTCGCAAGGATTGCAG

gRNA2_OT3R AAGCTGCGGATTTATGGGTG

The pHACK_G4 > QF2 insertion at the attP2 site by PhiC31 integrate is in the opposite orientation of GMR-GAL4 lines inserted at attP2 as generated using the pBPGUw vector (Addgene #17575; Figure 5C) (Pfeiffer et al. 2008). To address this, we used the pBPGUw vector as a backbone to generate a compatible HACK_G4 > QF2 plasmid. The pHACK_QF2 vector was digested with SnaBI and PacI followed by ligation to the pBPGUw backbone amplified by PCR from pBPGUw. The ampicillin resistance site and bacterial origin of replication might potentially affect HDR accuracy; therefore, this vector region was flanked by mFRT71 sites for removal by mFLP5 if necessary (Hadjieconomou et al. 2011). The final construct was named pBPGUw_HACK_QF2 (Addgene #80276). We cloned GAL4 5′ and 3′ homology arms and gRNAs as described above (pBPGUw_HACK_G4 > QF2, Addgene #80277; Figure S2D).

Figure 5.

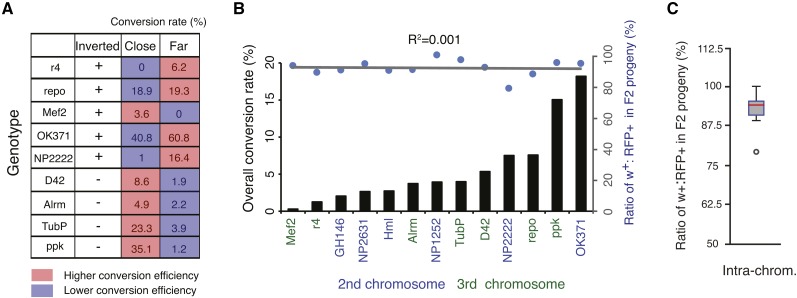

HACK efficiency depends on the genomic distance and orientation of target and donor and reveals hot and cold spots of homology-directed gene conversion. (A) Comparison of conversion efficiencies using close (donor and target within 0–3 cytological bands) and far (donor and target within 3–6 cytological bands) revealed relative orientations of target and donor influence HACK conversion efficiencies. (B) Overall conversion rates of the 13 GAL4 lines show >50-fold range differences (black bars) but are not correlated with a reduced fitness caused by DSB HACK events in GAL4, as measured by the ratio of w+ (GAL4+) to RFP+ (QF2G4H) F2 animals. (C) During the HACK process, the presence of the gRNA target sequence (GAL4) decreases the survival rate of flies containing GAL4 chromosomes by 7.4% when compared to progeny lacking GAL4 target sequences. N = 21,293 flies.

Primers to PCR amplify the backbone from pBPGUw:

pBPGUw-FOR TAATGCGTATGCTTAattaaTATGTTCGGCTTGTCGACATG

pBPGUw-REV CAGATCTCGCGTTACgtaCTTGAAGACGAAAGGGCCTC

Primers to insert mFRT71 at the SnaBI site:

TTCGTCTTCAAGTACGAAGTTTCTATACTTTCTAGAGAATAGAAACTTCtacGTAACGCGAGATCTG

Primers to insert mFRT71 at the PciI site:

GTCGACGGTAACATGtGAAGTTTCTATACTTTCTAGAGAATAGAAACTTCCATGTGAGCAAAAGG

Drosophila genetics

The fly stocks used in the study are 10xQUAS-6xGFP (BS#52264) (Shearin et al. 2014), 5xUAS-mtdt-3HA (Potter et al. 2010), 5xQUAS-nucLacZ (BS#30006) (Potter et al. 2010), 5xUAS-GFPnls (BS#4775), Act5C-Cas9 (BS#54590) (Port et al. 2014), Vas-Cas9 (BS#51323 on X chromosome and BS#51324 on third chromosome) (Gratz et al. 2013), and Crey+1B (BS#766) (Siegal and Hartl 1996). The specific GAL4 lines from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center are listed in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1. GAL4 lines converted to QF2 lines using the HACK method.

| GAL4 line | Expression pattern | BS# | Chr. | Note | QF2 line |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alrm-GAL4 | Glial subset | III | Alrm-QF2G4H | ||

| D42-GAL4 | Motor neurons | 8816 | III | ET | D42-QF2G4H |

| elav-GAL4 | Pan-neuronal | 458 | X | ET | elav-QF2G4H |

| GH146-GAL4 | Olfactory PNs | 30026 | II | ET | GH146-QF2G4H |

| Hml-GAL4 | Hemocytes | 30139 | II | Hml-QF2G4H | |

| Mef2-GAL4 | Pan-muscle | 27390 | III | Mef2-QF2G4H | |

| NP2222-GAL4 | Glial subset | 112830 | II | ET | NP2222-QF2G4H |

| NP2631-GAL4 | MB subset | 104266 | II | ET | NP2631-QF2G4H |

| OK107-GAL4 | Pan-MB | 106098 | IV | ET | OK107-QF2G4H |

| OK371-GAL4 | vGlut neurons | 26160 | II | ET | OK371-QF2G4H |

| Pebbled-Gal4 | Pan-ORN, GN | Sweeney (2007) | X | ET | Pebbled-QF2G4H |

| Ppk-GAL4 | Type IV MD neurons | 32079 | III | Ppk-QF2G4H | |

| r4-GAL4 | Adipose tissue | 33832 | III | r4-QF2G4H | |

| repo-GAL4 | Pan-glial | 7415 | III | ET | repo-QF2G4H |

| tubP-GAL4 | Pan-cellular | 5138 | III | tubP-QF2G4H |

BS, Bloomington Stock; Chr., chromosome; ET, enhancer trap; PN, projection neuron; MB, mushroom body; vGlut, ventrolateral glutamatergic; ORN, olfactory receptor neuron; GN, gustatory neuron; MD, multidendritic.

Table 2. GMR-GAL4 lines converted to QF2 lines using the HACK method.

| GAL4 linea | Neuronal expression pattern | BS# | QF2 line |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMR57C10-GAL4 | Pan-neuronal | 39171 | GMR57C10-QF2G4H |

| GMR58E02-GAL4 | Dopaminergic subset | 41347 | GMR58E02-QF2G4H |

| GMR10A06-GAL4 | Olfactory receptor neurons | 48237 | GMR10A06-QF2G4H |

| GMR20A02-GAL4 | DN1 central body neurons | 48870 | GMR20A02-QF2G4H |

| GMR24C12-GAL4 | Olfactory interneurons | 49076 | GMR24C12-QF2G4H |

| GMR71G10-GAL4 | Mushroom body subset | 39604 | GMR71G10-QF2G4H |

| GMR82G02-GAL4 | Mushroom body subset | 40339 | GMR82G02-QF2G4H |

| GMR16A06-GAL4 | Mushroom body subset | 48709 | GMR16A06-QF2G4H |

GMR-GAL4 lines inserted at attP2 on third chromosome (68A4).

Genetic crosses in the study are summarized in Figure 2B. In short, the parental cross combines target GAL4 lines to QF2G4H donor stocks that include Act5C-Cas9 or vasa-Cas9 on the X chromosome. Next, for F1 crosses, four pairs of single male to double balancer virgin females vials (3–4 females/vial) were established for each genotype. Only F2 male progeny were examined under light and fluorescence microscope (see below for detailed description of the setup) for w+ and red fluorescent protein (RFP)+ eye markers. Male flies were examined between day 10 and 18 of the F1 crosses. Typically, each vial gave rise to ∼20 w+ and ∼20 RFP+ male flies. The candidate HACKed flies (w+ and RFP+) were further examined by crossing to reporter lines (10xQUAS-6xGFP) (Shearin et al. 2014). The 3xP3-RFP marker can be removed by crossing to Crey+1B flies (Siegal and Hartl 1996). All the crosses were maintained in a 25° incubator to ensure precise timing of the life cycle.

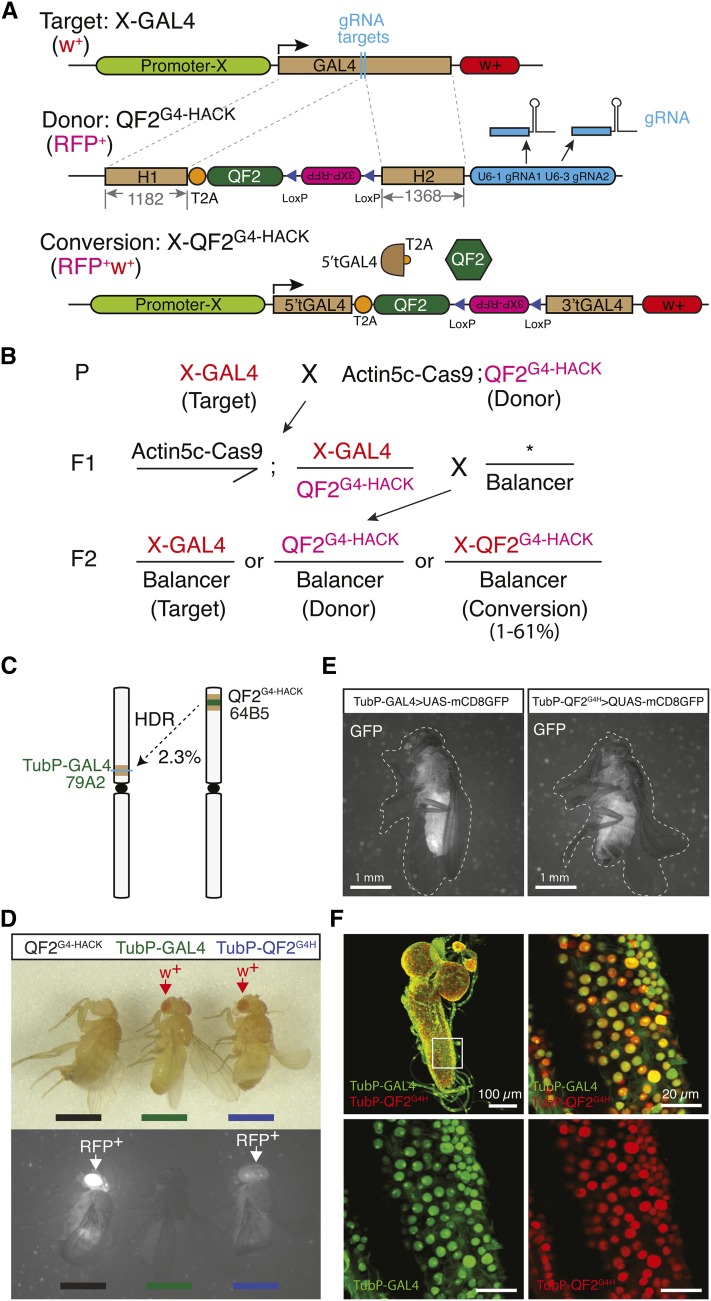

Figure 2.

HACK can be used to convert GAL4 lines into QF2 lines. (A) Genetic reagents for GAL4 to QF2 HACKing. The target is a GAL4 transgenic line (X-GAL4). The QF2G4-HACK donor consists of 5′ and 3′ GAL4 homology arms flanking an in-coding frame T2A-QF2 and a 3xP3-RFP eye marker. Outside the GAL4 homology arms are U6:1 and U6:3 promoters used to express two independent gRNAs that target GAL4 for DSBs in the presence of the Cas9 protein. After conversion, the X-QF2G4-HACK line contains the T2A-QF2 cassette and the 3xP3-RFP marker. The U6-gRNAs are not included in the converted target. (B) Converting GAL4 lines to QF2 lines using the HACK system involves two genetic crosses. The success rate depends on both the target and donor lines but ranges from 0 to 60%. (C) TubP-GAL4 (79A2) was HACKed using a TubP-QF2G4H (64B5) insertion. (D) The donor (QF2G4H) and target (TubP-GAL4) contain a single eye marker, RFP or w+, respectively. A successfully HACKed line (TubP-QF2G4H) is double positive for the eye markers (RFP and w+). (E) The pan-tissue expression pattern of TubP-QF2G4H is consistent with that of TubP-GAL4. Bar, 1 mm. (F) Second instar larvae labeled by nuclear-localized reporters for both TubP-GAL4 (green) and TubP-QF2G4H (red). Note that GFPnls and nucLacZ show different subnuclear localization. GFPnls is found more concentrated in the nucleolus while nucLacZ is excluded from the nucleolus. Genotype: TubP-GAL4>UAS-nucGFP, TubP-QF2G4H > QUAS-nucLacZ. Bar, 100 µm (left top image) and 20 µm (zoomed-in images). Left top image is 118 µm Z stack and the other three are 3.84 µm stacks.

Fluorescence microscope setup

For adult images, a Carl Zeiss (Thornwood, NY) Discovery V8 SteREO microscope equipped with Achromat S 1.0× FWD 63-mm objective and illuminated with X-Cite 120Q excitation light source was used. Images could be detected through eyepieces or directed to a charge-coupled device camera (Jenoptik ProgRes MF cool) for real time image acquisition (ProgRes Mac Capture 2.7.6). A microscope filter shield (Nightsea, #SFA-LFS-GR) was used to protect against strong reflection of green excitation light from the CO2 pad while screening for RFP+ flies.

Acj6-GAL4 and GH146-QF2 colabeling experiment

To eliminate the olfactory neuron innervations in the antennal lobe from Acj6-GAL4, the antennae were removed 6 days before brain dissection for antennal nerve degeneration.

Nervous system dissection and immunohistochemistry

Dissection of the adult nervous system was performed as described previously (Potter et al. 2010). In short, brains and ventral nerve cords of second and third instar larvae or 4- to 6-day-old flies were dissected in 1× PBS solution and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (dissolved in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100) for 15 min. Fixation and washes were done at room temperature. Fixed tissues were washed three times with PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 (PBT) before incubating in PBT twice for 20 min. A 5% normal goat serum dissolved in PBT blocking solution was used to wash tissues for 30 min. Next, the tissues were placed in primary antibody mixes for 1–2 days at 4° followed by two 20 min PBT washes. The tissues were placed in secondary antibody mixes for 1 day in the dark at 4°. The following day the tissues were washed in PBT for 20 min and placed in mounting solution (Slow Fade Gold) for at least 1 hr before imaging. All wash steps were performed at room temperature.

For the nuclear colocalization experiments of TubP and repo drivers, the primary antibodies included preabsorbed rabbit anti-LacZ (1:50, Cat#559761; MP Biochemicals) and chicken anti-GFP (1:1000, #GFP1020; Aves Labs) antibodies. Secondary antibodies were Alexa 649 anti-rabbit (1:200, #DI-1649; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and Alexa 488 anti-chicken (1:200, #A11039; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To label the cell nucleus, nervous tissues were incubated with DAPI (1:1000 dissolved in PBT, #21094; Invitrogen) for 10 min at room temperature after the secondary antibody wash step.

To enhance GFP signals, primary antibodies used in the study were rabbit anti-GFP (1:250, #A11122; Life Technologies), chicken anti-GFP (1:1000, #GFP1020; Aves Labs), and rat anti-mCD8 (1:250, MCD0800, in the experiments using mCD8:GFP as the reporter; Invitrogen). Secondary antibodies were Alexa 488 anti-rabbit (1:200, #A11034; Invitrogen), Alexa 488 anti-chicken (1:200, #A11039; Invitrogen) and Alexa 488 anti-rat (1:200, #A11006; Invitrogen). For mtdt-3HA, we used rat anti-HA (1:250, #11867423001; Hofmann La Roche, Nutley, NJ) as the primary antibody and Cy3 anti-rat (1:200, #112-165-167; Jackson ImmunoResearch) as the secondary antibody. If 3xP3-RFP was not removed, we used Alexa 633 anti-rat (1:200, #A21094; Invitrogen) as secondary the antibody. To visualize the structure of the nervous system, mouse anti-nc82 (1:25; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) was used as the primary antibody and Alexa 647 (1:200, Z25008; Life Technologies) or Cy3 anti-mouse (1:200, 115-165-166; Jackson Immuno Research) as the secondary antibody.

Confocal imaging and image processing

Confocal images were taken on a Carl Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope equipped with 10× (Fluar 10×/0.5, Carl Zeiss) and 40× (Plan-Apochromat 40×/1.3 oil DIC, Carl Zeiss) objectives. Zen 2012 software was used for image acquisition. For illustration purposes, Z-stack images were collapsed onto a single image by ImageJ using maximum-intensity projection and pseudocolored into different acquisition channels using a red-green-blue plug-in.

Data availability

Drosophila lines are available at Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center or upon request. Plasmid constructs are available at Addgene or upon request.

Results

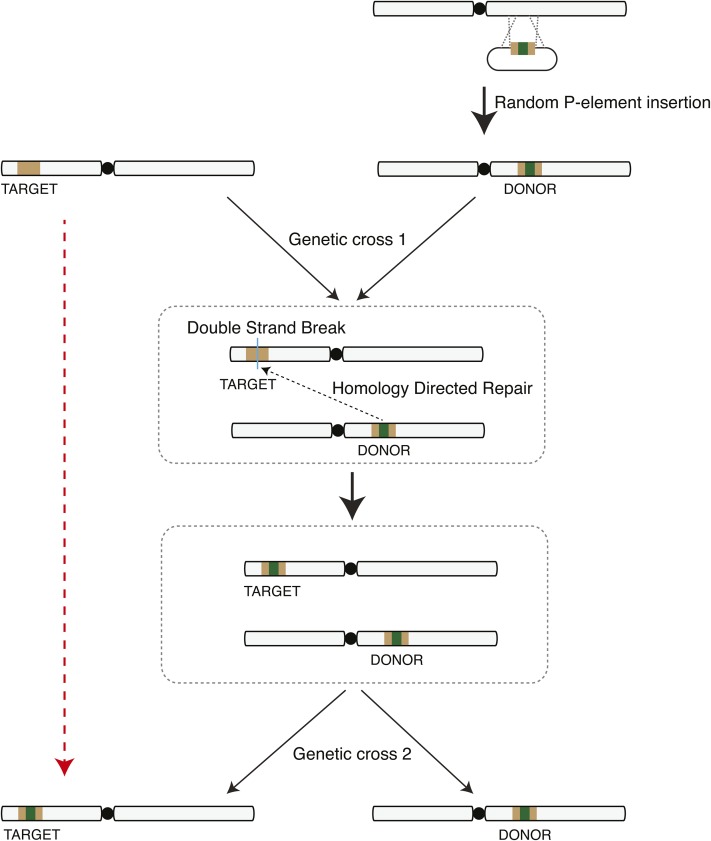

Editing DNA sequences by targeted gene conversion

We describe a genomic engineering process that drives gene conversion using a single DNA donor template (Figure 1). DNA donors are integrated into the genome by random P-element insertions. The donor consists of two components: homology sequences for repair searching and genetic material for HDR-mediated insertion. When a DSB is introduced at the target sequence, the donor is employed as a template for DNA repair through HDR and the DNA of interest is also incorporated. The donor can then be separated from the target by genetic crosses. The final result is generation of a target containing the DNA of interest (Figure 1, dashed red arrow, and Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Schematic outlining gene conversion using homology-directed repair from an integrated transgene. A donor plasmid consisting of a core cassette carrying the DNA of interest for incorporation (green) flanked by target homology arms (brown) is randomly inserted into the genome by P-element transposition. A genetic cross brings the target and donor together into the same cell. A DSB is induced in the target DNA to trigger HDR-mediated insertion of the DNA of interest into the target. A second genetic cross segregates the converted target and donor insertions. The final result (red dashed arrow) is insertion of donor sequence into the target site.

HACK converts GAL4 transgenes into QF2

We employed an artificial gene conversion method to target the GAL4 sequence for insertion of donor DNA (Figure 2). Given the need for well-defined transactivators of other binary expression systems, we chose to design DNA sequences that would convert GAL4 into a different binary expression transactivator: QF2. GAL4 homology arms are required for repair searching in HDR and will remain in the genome after conversion. To generate a functional QF2-expressing line, the donor DNA sequence inserted is a T2A-QF2 coding cassette in frame with the targeted GAL4 (Figure 2A and Figure S2). T2A is a ribosomal skipping sequence that allows polycistronic protein translation from the same RNA transcript (Diao and White 2012). Thus, the genomic enhancer/promoter would drive 5′ truncated GAL4 and QF2 proteins (Figure 2A). This converts a GAL4 transgene into a QF2 transgene (Figure 2A).

To monitor a successful HDR-mediated insertion of the desired sequence, the QF2 donor also contains an eye marker for transgenic screening (3xP3-RFP) (Figure 2A). Outside the homologous target regions are RNA polymerase III-dependent U6 promoters used to transcribe Cas9 gRNAs targeting the middle region of the GAL4 sequence. In the presence of Cas9 protein driven by Act5C or Vasa promoters (Ren et al. 2013; Gratz et al. 2014), two independent DSBs will be generated in the GAL4 sequence. The damaged DNA could be repaired by either NHEJ or HDR. In the case of HDR, the damaged double-stranded DNA associates with a repair protein complex that initiates a search for homologous sequences in the genome as a template for repair (Bernstein and Rothstein 2009). If the exogenous QF2 donor is used then the T2A-QF2 and 3xP3-RFP are inserted into the GAL4 sequence (Figure 2A). Successful HACK events can be screened by identifying animals that express RFP in the eyes (Figure 2B and Figure S1). The 3xP3-RFP is flanked by loxP sites and can be subsequently removed with Cre recombinase (Figure S3) (Siegal and Hartl 1996).

Crossing scheme and nomenclature of HACK system

Through genetic crosses, target (X-GAL4), donor (QF2G4HACK), and Act5C-Cas9 (or Vas-Cas9) were combined in the same animal (Figure 2B, parental cross). The F1 male progeny were crossed to wild type or balancer flies. Since Drosophila males do not undergo chromosomal recombination during meiosis, the F2 male will contain either the w+ or RFP marker, which indicates GAL4 and QF2G4HACK transgenes, respectively. F2 males containing double markers (w+ and RFP) indicate successful HDR-mediated incorporation of T2A-QF2 and 3xP3-RFP into the GAL4 sequence (Figure 2B and Figure S1). Due to positional effects (Levis et al. 1985), the GAL4-to-QF2 converted flies might demonstrate different patterns and levels of RFP expression compared to the HACK donor. Successfully HACKed lines were named X-QF2G4HACK (or X-QF2G4H for short). This establishes a nomenclature X-YZHACK in which X refers to the original enhancer/promoter locus, Y refers to the introduced DNA element, Z refers to the replaced DNA element, and HACK indicates the reagent was generated using the HACK method.

HACK conversion with a ubiquitously-expressed GAL4 line

Tubulin is a major component of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton and as such the tubulin promoter can drive ubiquitous GAL4 as detected by a GFP reporter (TubP-GAL4 > UAS-mCD8:GFP). We used QF2G4H at cytological location 64B5 to HACK the TubP-GAL4 at 79A2 (Figure 2C). Of the 128 F2 w+ males screened, 3 of them exhibited both w+ and RFP eye markers (Figure 2D). We calculated the efficiency of HACK conversion as 3/128 (2.3%) (see Figure S1 for definition of conversion rate). Note, this involved setting up four single male F1 crosses (Figure 2B), yet a single male F1 cross may have been sufficient to identify a conversion event. We verified the TubP-QF2G4H lines by genomic sequencing and expression pattern comparison (Figure 2E and Figure S3). All three TubP-QF2G4H lines drive GFP expression under control of QUAS, and no mtdt-3HA signal was detected when crossed to UAS-mdt-3HA (TubP-QF2G4H > 10XQUAS-6xGFP, 5XUAS-mtdt-3HA) (Figure 2E, Figure S3, C and D). Similarly, TubP-QF2G4H failed to drive expression in salivary glands from a UAS-GFPnls reporter (Figure S3E). Nuclear reporters driven by TubP-GAL4 and TubP-QF2G4H colocalized in the dissected larval brain tissue (Figure 2F). These data suggested that TubP-QF2G4H recapitulated the expression pattern of the original TubP-GAL4 line.

The X-QF2G4H expresses a 5′ truncated GAL4 that contains the GAL4 DNA-binding domain and could potentially bind to UAS sequences, which might interfere with the function of other GAL4 transgenes. To address this, we examined the effects of X-QF2G4H coexpressed with Y-GAL4 using olfactory projection neuron lines that target well-characterized subsets of neuronal populations. We first generated GH146-QF2G4H from GH146-GAL4 (Figure S4, A and B). GH146 drives expression in ∼150 well-defined projection neurons situated around the antennal lobes (Jefferis et al. 2007). The Acj6-GAL4 expression pattern partially overlaps with GH146 in anterodorsal projection neurons. When combined (Acj6-GAL4 > 5XUAS-mtdt-3HA, GH146-QF2G4H>10XQUAS-6xGFP) (Komiyama et al. 2004), GH146-QF2G4H does not appear to affect the UAS-geneX signal of Acj6 positive neurons (Figure S4C), suggesting that the truncated GAL4 protein is either nonfunctional or possibly degraded. In addition, the GH146-QF2G4H line more closely mimics the original GH146-GAL4 enhancer trap expression pattern than an enhancer-cloned transgenic GH146-QF2 line (Figure S4D).

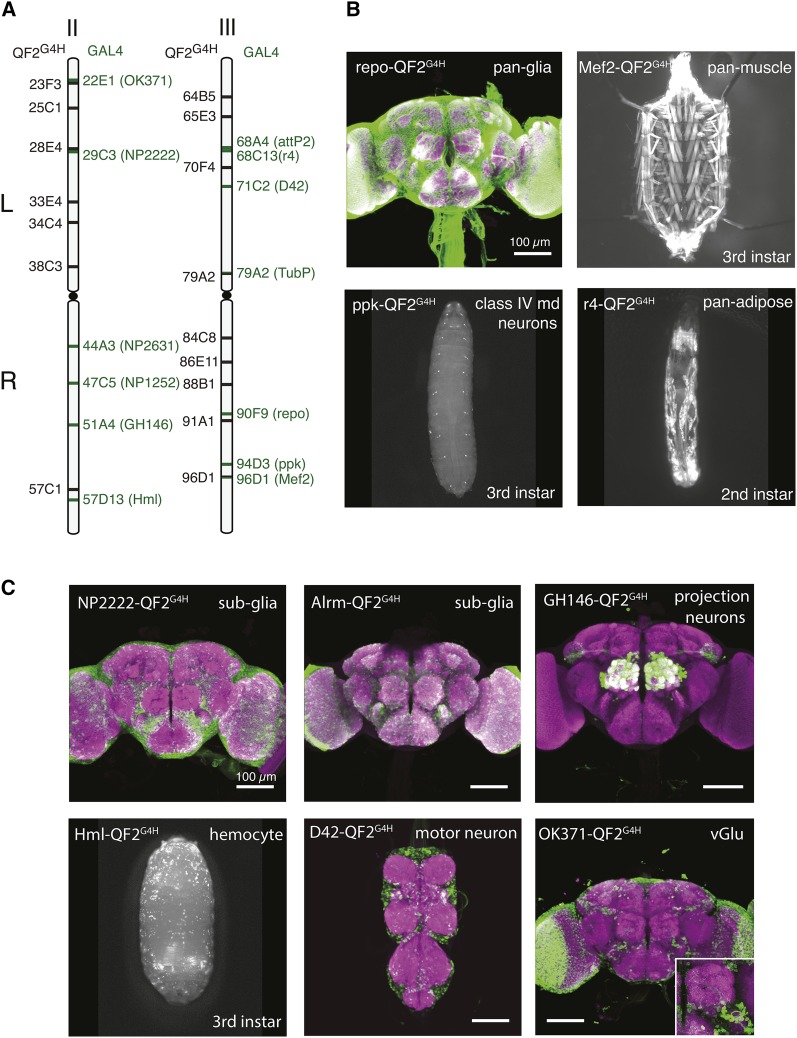

Establishing a collection of QF2G4H donor lines throughout the genome

Previous studies in human somatic cells have found that homologous chromosomes make contact at the sites of DSBs (Gandhi et al. 2012). Furthermore, in yeast, the efficiency of repair after DSB is correlated with the contact frequency of the donor and damaged sites (Lee et al. 2016). We reasoned that the locations of the target and the donor relative to each other might contribute to the success rate of HACK, with greatest efficiency when the donor and the target are in close proximity on sister chromosomes. To enable essentially any GAL4 target to be HACKed, and to examine efficiencies of gene conversion by different donor lines, we generated a QF2G4H donor collection by random P-element transgenesis (Figure 1). A total of 7 out of 9 lines on the second chromosome and 9 out of 18 lines on the third chromosome were selected as candidate QF2G4H donors for their fairly even distribution along the chromosomes (Figure 3A and Figure S5).

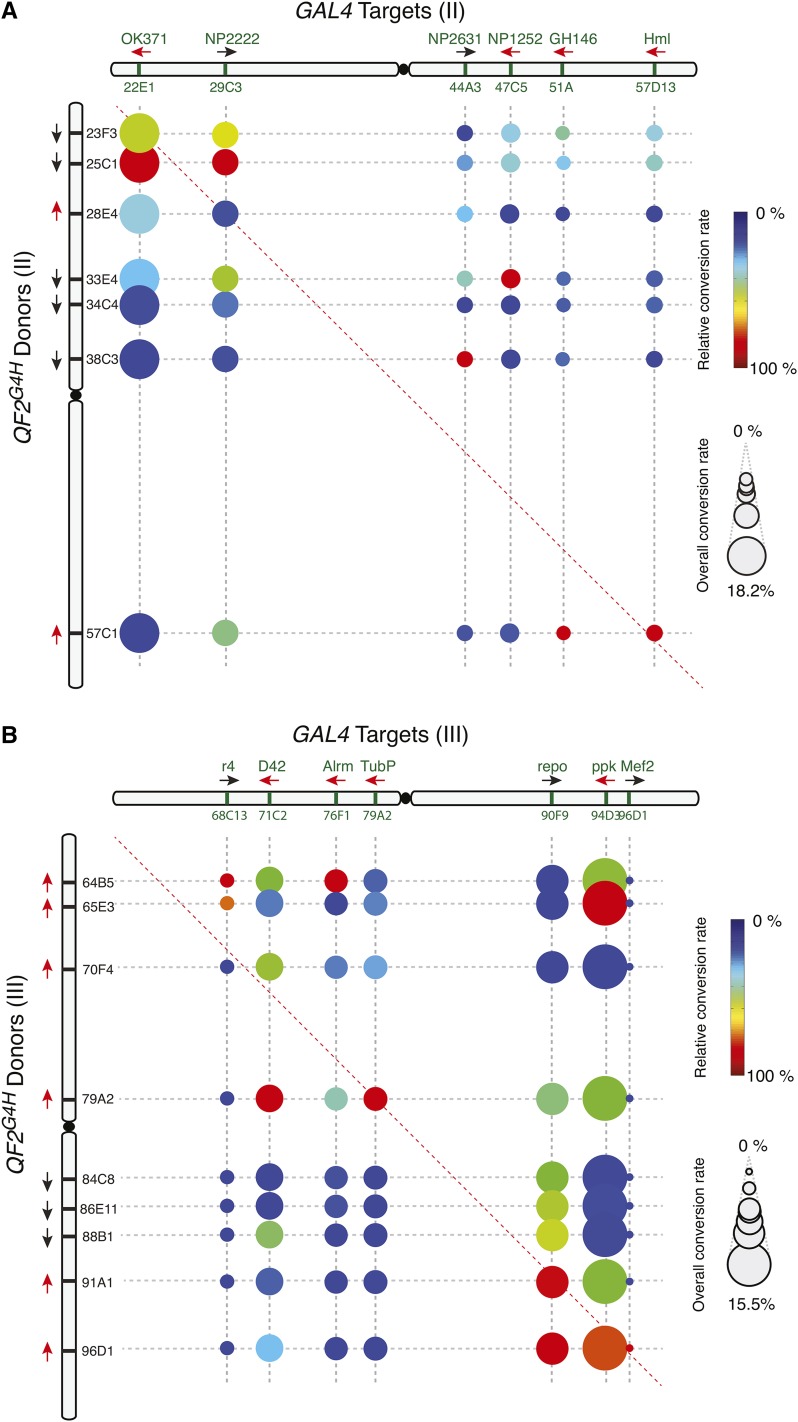

Figure 3.

HACK can be applied to convert commonly-used GAL4 lines at various genomic locations. (A) Cytological locations of QF2G4H and GAL4 lines used in this study. The GAL4 lines are distributed across the second and third chromosomes. (B–C) Examples of QF2G4H lines generated by the HACK method using GAL4 lines with (B) broad (e.g., pan-glial) and (C) defined (e.g., class IV multidendritic neurons) expression patterns. Purple, nc82 antibody staining; Green, GFP antibody staining. Bar, 100 µm (brain and ventral nerve cord).

HACK is effective for the conversion of GAL4 lines inserted across the whole genome

GAL4 enhancer traps are useful reagents, yet reproducing the desired expression pattern as a transgene may be difficult to accomplish (Potter and Luo 2010). To test if HACK can be used to convert a variety of genomic locations, we targeted the most frequently requested GAL4 stocks available from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Table 1; Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, personal communication). These GAL4 lines were systematically crossed to the QF2G4H donor collection to generate X-QF2G4H lines and assess conversion success rates.

Toxicity was occasionally an issue for QF constructs, but was recently solved with the introduction of QF2 (Riabinina et al. 2015). To further verify that high QF2 expression levels would not affect HACK efficiencies, additional pan-tissue GAL4 lines were first assayed: repo-GAL4 (pan-glia), Mef2-GAL4 (pan-muscle), Hml-GAL4 (hemocyte), and r4-GAL4 (pan-adipose tissue). All lines were successfully converted into QF2G4H lines with the expected expression patterns (Figure 3). Next, we examined widely-used GAL4 lines with defined expression patterns: NP2222-GAL4 (glial subset), Alrm-GAL4 (glial subset), GH146-GAL4 (olfactory projection neurons; see above), ppk-GAL4 (type IV multidendritic neurons), D42-GAL4 (motor neurons), NP2631-GAL4 (mushroom body subset), and OK371-GAL4 (ventrolateral glutamatergic neurons). We included NP1252-GAL4 at 47C5 to test the efficiency of targeting a GAL4 in that region. These lines were all successfully HACKed, and expression patterns driven by QF2 were consistent with those of the GAL4 lines (Figure 3, Figure S6, and Table 1). Of the 14 GAL4 lines we tested, only 1 GAL4 line (en2.4-GAL4 at 47F15, BS#30564) could not be HACKed after two attempts (see Discussion). Of the successfully HACKed flies with both eye markers, all of them exhibited consistent expression patterns as compared to the original GAL4 lines (N > 100).

HACK efficiency varies with different target and donor pairs

We examined all pairwise conversion efficiencies between the second chromosomal GAL4 target and QF2G4H donor lines, as well as all pairwise conversion efficiencies between the third chromosomal GAL4 target and QF2G4H donor lines. In general, the efficiency of gene conversion appears to relate directly to the proximity of the donor and target insertion sites in the homologous chromosomes (Figure 4, A and B). The closer a donor line is to a GAL4 target in the homologous chromosome, the higher the efficiency of conversion. However, we observed >50-fold differences in the overall conversion rates, ranging from 0.28% for Mef2-GAL4 to 18.2% for OK371-GAL4 (Figure 5, A and B). Thus, some genomic regions appeared more efficient at gene conversion (hot spots) and some were more difficult to convert (cold spots).

Figure 4.

HACK efficiencies across the second and third chromosome. (A–B) Conversion frequencies were tested for each donor and target pair on the (A) second or (B) third chromosome. The size of the circle represents the overall conversion rate of the target GAL4 line to all tested donor lines. Larger circles represent target GAL4 sites that were easier to convert (hot spots), while smaller circles represent target GAL4 sites that demonstrated low conversions (cold spots). For example, 18.2% of all F2 progeny of crosses from OK371-GAL4 and all seven second chromosome donors demonstrated conversions. The color indicates the relative conversion rate of the donor normalized to the highest conversion rate for the corresponding GAL4 lines. Thus colors indicate which donor line is most efficient for driving QF2G4H HACK conversions for a particular GAL4 line. For example, for OK371-GAL4, QF2G4H donor at 25C1 was the most effective (relative conversion rate 100%), and QF2G4H at 23F3 roughly two-thirds as effective (relative conversion rate 67%). Black and red arrows indicate the inserted transgene is in the forward and reverse orientation, respectively, relative to the reference Drosophila genome (Flybase R6.10).

Consistent with previous observations (Engels et al. 1994), the orientation of the donor and target (forward or reverse in relation to the sequenced genome) can also affect gene conversion frequency. We compared HACK frequencies of donor and target pairs that are within 3 cytological bands (close pairs) with those between 3–6 cytological bands (far pairs). When the donors and targets are in the same orientation, 4 out of 4 close pairs exhibit high conversion rates. In contrast, 4 out of 5 far pairs exhibit higher conversion when donors and targets are inverted (Figure 5A).

DSBs are potent inducers of genomic mutations and cell death. In the HACK process, the GAL4 sequence serves as the target for Cas9 endonuclease. We examined whether HACK affects the general health of individual flies by comparing the number of observed RFP (QF2G4H) and w+ (X-GAL4 and X-QF2G4H) flies in the F2 generation (see crossing scheme in Figure 2B). Mendelian genetics predicts that RFP+ and w+ F2 progeny should be in a 1:1 ratio, and deviations from this ratio indicate fitness costs. There is a ∼7.4% decrease in the number of predicted w+ (GAL4+) progeny as compared to control RFP+ donor flies (Figure 5C, ratio = 0.926, SEM = 0.015, n = 13 F1 crosses with a total of 21,293 F2 flies). A regression curve showed no correlation between survival percentage of GAL4+ flies and the HACK success rate (Figure 5B, slope = −0.004, R2 = 0.001). This suggests that DSBs occur equally in all GAL4 targets, and that the introduction of a DSB in the GAL4 gene is a likely factor in reducing progeny fitness. Furthermore, the data suggest that differences in GAL4 conversion rates are more likely due to differences in HDR efficiencies.

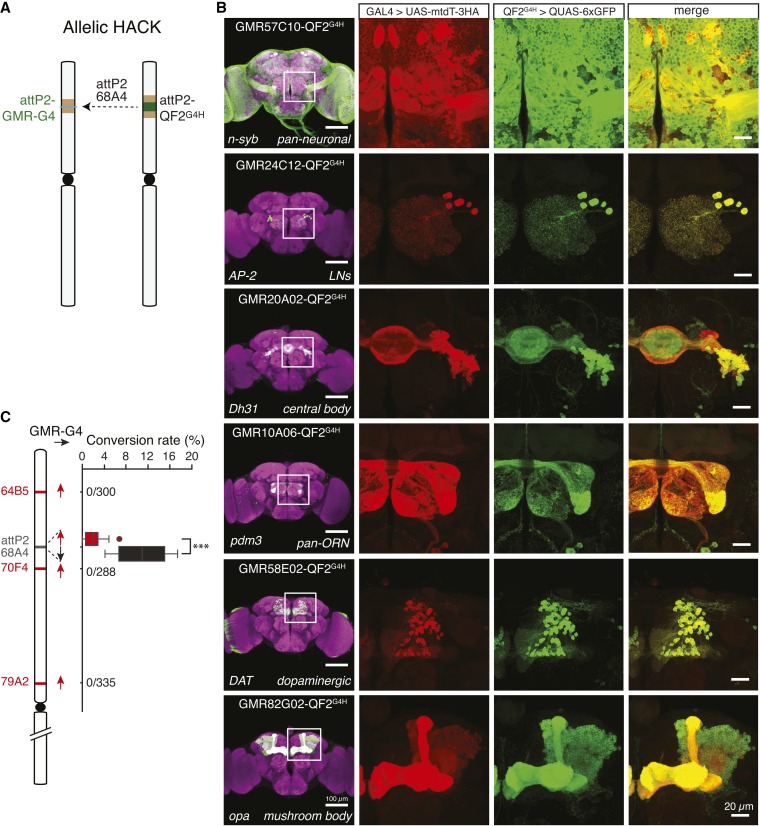

Allelic genes do not necessarily lead to high conversion rates

A simple prediction would be that donors and targets at allelic sites on homologous chromosomes would demonstrate maximal gene conversion rates. In Drosophila, transgenes can be inserted into a specific locus using the PhiC31/attP integrase system (Groth et al. 2004; Bischof et al. 2007). Many GAL4 transgenes, most notably the GMR-GAL4 collection from the Janelia Research Campus, have been inserted at the attP2 locus (Jenett et al. 2012). To directly investigate gene conversion from the same genomic locus, we inserted QF2G4H donor constructs at the attP2 locus (Figure 6A). The donor lines would be of special interest to the Drosophila community since >7000 GMR GAL4 lines have been targeted to the attP2 site.

Figure 6.

Donor and target inserted at the same loci do not necessarily lead to high conversion frequencies. (A) An attB-QF2G4H donor insert at the attP2 site is used to HACK Janelia GMR-GAL4 lines inserted at attP2. (B) Examples of QF2 lines that were HACKed from widely used attP2-GMR-GAL4 lines. Colabeling experiments demonstrate expression patterns of QF2G4H recapitulate those of the original attP2-GMR-GAL4 insertion. Bar, 100 µm (brains, left panel), 20 µm (inset magnification). (C) The conversion rate of attP2-GMR-GAL4 lines using attP2-QF2G4H or nearby QF2G4H lines. The attP2-QF2G4H donors were either in forward (black arrow, as generated by pBPGUw-HACK_G4 > QF2) or reverse (red arrow, as generated by pHACK_G4 > QF2) orientations. Both exhibited significantly higher success rates than three nearby donors (ANOVA, P < 0.001). The conversion rate mediated by attP2-QF2G4H in the same orientation as attP2-GMR-GAL4 was significantly higher than the conversion rate mediated by attP2-QF2G4H inserted in the opposite orientation (P = 4.7 × 10−5, Student’s t-test).

With the attP2-QF2G4H donors, eight commonly-ordered attP2-GMR-GAL4 lines were successfully converted to QF2G4H and expression patterns were consistent with those of the original GAL4 as shown in the colabeling experiments (Figure 6B, Figure S9, and Table 2). Interestingly, HACK efficiency differed if attP2-QF2G4H was inserted in the same or opposite orientation relative to attP2-GMR-GAL4 (Figure 6C). The efficiency of conversion was low when using the oppositely-oriented attP2-QF2G4H donor (Figure 6C red box plot, 2.02 ± 0.5 (SEM) %, n = 15 F1 crosses with a total of 3,014 F2 males). The HACK efficiency was five times higher when using the attP2-QF2G4H donor in the same orientation as the GMR-GAL4 lines (Figure 6C black box plot, 10.9 ± 2.8 (SEM) %, n = 4 F1 crosses with a total of 943 F2 males). This confirms the results described for other genomic locations that the relative orientation of donor and target influence conversion efficiency (Figure 5A).

Donor and targets inserted at allelic sites should represent maximal conversion efficiencies. However, the observed allelic conversion rate of ∼10% was low relative to other genomic locations (e.g., OK371 demonstrates ∼60% conversion efficiency). To understand if a low conversion rate was due to the attP2 QF2G4H donor, we tested three other QF2G4H donors inserted in genomic locations close to attP2 (64B5, 70F4, and 79A2) paired with three different GMR lines (GMR57C10-GAL4, GMR20A02-GAL4, and GMR24C12-GAL4). None of them were successful in generating a QF2G4H line (n = 9 F1 crosses with a total of 1,769 F2 males) (Figure 6C). The HACK method can be divided into two sequential steps: CRISPR/Cas9 generates a DSB in a target locus, followed by HDR-mediated insertion of exogenous donor DNA. To determine if GAL4 sequences had been successfully targeted by CRISPR/Cas9, we genotyped individual GAL4+ F2 males from the F1 HACK cross that had not been successfully converted (Figure 2B, GAL4 w+ positive but QF2G4H 3xP3-RFP negative). All examined F2 males with only the w+ marker showed indel mutations at the gRNA targeted sequences (N = 10; Figure S7). These results suggest that DSBs at the attP2 locus occur efficiently, but HDR is limited. Thus the attP2 locus might be a cold spot for HDR.

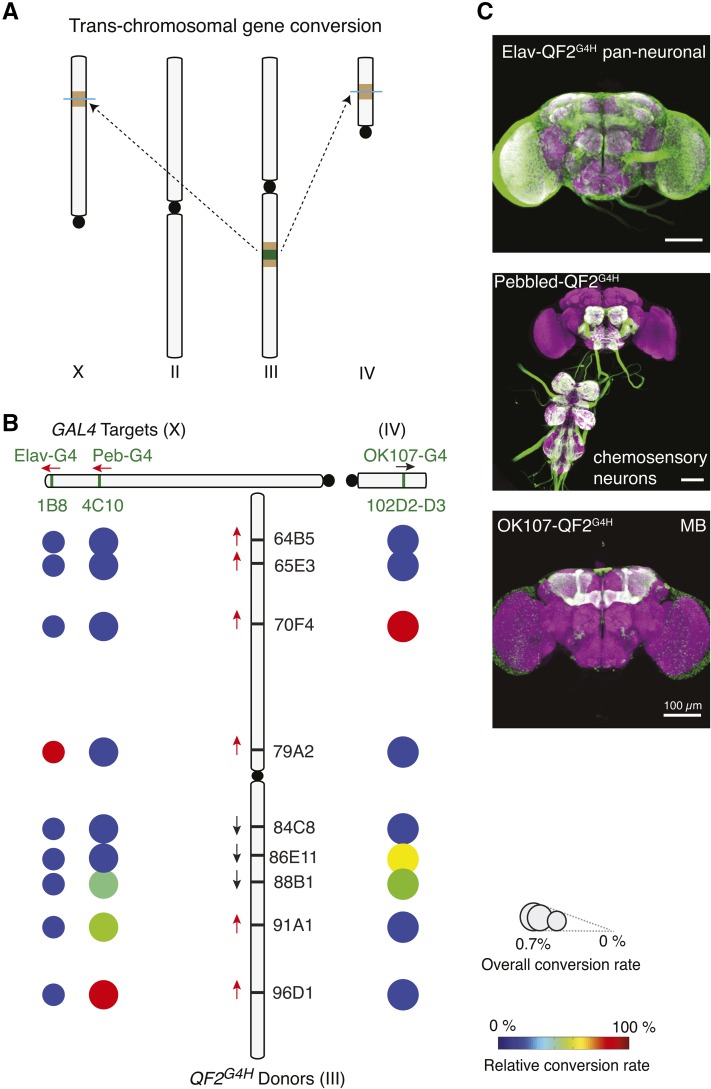

HACK can mediate trans-chromosomal gene conversion

We next asked if the HACK strategy could be applied to targets and donors on different chromosomes. When HDR is used for DSB repair, damaged ends search the whole genome for homologous sequences (Szostak et al. 1983). Thus, trans-chromosomal HACK might work, but it would be expected to be less efficient. Indeed, pan-neuronal (elav-GAL4) and pan-chemosensory (pebbled-GAL4) target GAL4 lines on the X chromosome were successfully HACKed by QF2G4H donors on the third chromosome (Figure 7). This trans-chromosomal HACK strategy was not limited to targets on the X chromosome. The pan-mushroom body GAL4 line, OK107-GAL4, on the fourth chromosome could be HACKed by QF2G4H donors on the third chromosome (Figure 7 and Figure S8). The overall conversion rate in trans-chromosomal HACK was low, as expected (0.3–0.7%). We reasoned that this was the result of inefficient HDR and sequenced non-HACKed F2 GAL4 flies (GAL4 w+ positive but QF2G4H 3xP3-RFP negative). Indeed, all GAL4+ flies examined revealed indel mutations, indicating successful DSB events at the GAL4 sequence (N = 6, Figure S8B). In summary, these results suggest that trans-chromosomal HACKing is possible, albeit at a reduced frequency.

Figure 7.

HACK can be used for trans-chromosomal gene conversion. (A) Schematic demonstrating the use of a third chromosome QF2G4H donor to HACK target GAL4 lines on the X (Elav-GAL4, pebbled-GAL4) and fourth chromosomes (OK107-GAL4). (B) Results summarizing the efficiency of trans-chromosomal HACKing using different donor lines on the third chromosome. See Figure 4 legend for explanation of schematics. (C) The expression patterns of converted QF2G4H lines are consistent with the original GAL4 lines. Bar, 100 µm.

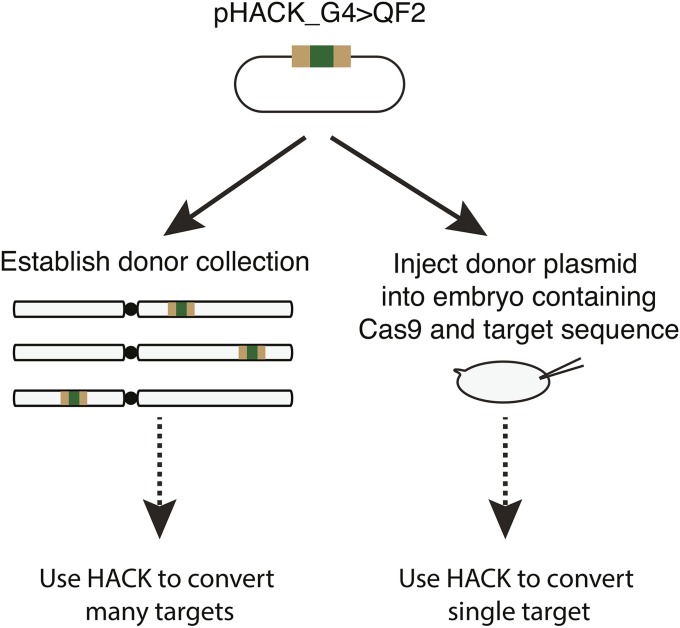

The HACK method is applicable to direct embryo injection of a pHACK donor plasmid

In cases in which only a single HACK target conversion is required, it might be preferable to directly inject a HACK donor plasmid into a target strain instead of first generating a donor HACK collection (Figure 8). We thus tested if the pHACK_G4 > QF2 plasmid DNA could be used directly as a donor for HACK-mediated conversion when injected into embryos containing Cas9 endonuclease (Gratz et al. 2014) and GAL4 target sequence. Using Vas-Cas9; OK371-GAL4 as the injection strain, we successfully converted OK371-GAL4 into OK371-QF2G4H using standard embryo injection procedures with a success rate of 5.8% (64/1107 G1 males) (Figure S10).

Figure 8.

The HACK method can be used with embryo injections to convert a single target at a time. The HACK donor plasmid can be used to generate a collection of integrated donors for use in converting many targets via genetic crosses. Alternatively, the HACK donor plasmid can be injected directly into embryos containing a target and a source of germline Cas9. See Figure S10 for details.

Discussion

We developed a genetic method that uses endogenous HDR mechanisms to modify existing transgenic components. The HACK method allows GAL4 lines to be converted to QF2 lines via two sequential crosses. The genetic crosses combine CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene conversion with a transgenic donor cassette to introduce T2A-QF2 elements into a GAL4 target. This allows QF2 protein to be expressed instead of a functional GAL4. The HACK technique is easy and efficient, and can be adapted to introduce other donor sequences. Instead of conducting multiple laborious, expensive, and time-consuming injections and screens aimed at introducing and characterizing different genetic elements, the HACK technique could be applied to convert essentially any GAL4 line into a range of different genetic reagents, such as GAL80, split-GAL4, LexA, FLPase, Cre, attP, FRT, and more. Future HACK donors could also be designed to replace the entire GAL4 gene by targeting 5′ and 3′ homologous components specific to the target transgenic sequence (e.g., the 5′ DSCP promoter and 3′ yeast terminator sequences in GMR-GAL4 insertions). Similarly, the HACK technique could be applied to other transgenic sequences besides GAL4 for conversion. This simplifies strategies aimed at generating transgenes containing different genetic components.

The recommended approach to HACK a GAL4 line to a QF2 line involves two steps. The first is to map the target GAL4 line for conversion (Potter and Luo 2010) (if its position is not already known). The second is to proceed with crosses outlined in Figure 2 with 2–3 QF2G4H donor lines that map closest to the target GAL4 region. Conversion efficiencies will depend on the orientation of the GAL4 target and QF2G4H donors, but a successful conversion typically required screening ∼150 w+ F2 progeny. If the GAL4 target is in a cold spot, then more F2 progeny may need to be screened. All 24 HACK conversion phenotypes we detected (showing both w+ and RFP+) represented actual conversion events, and we did not detect any false positives. This suggests that screening could be terminated after finding a single positive conversion phenotype.

P-element swapping is a previously developed unique genetic strategy for changing existing P-element transgenic lines (Sepp and Auld 1999). This technique relies on targeted transposition, in which one P element acts as a homology source for an excised P element that has left behind small homology arms (Sepp and Auld 1999). The efficiency of P-element swapping is low: at best, ∼1.5% of all single F1 male crosses will yield any P-element-swapped progeny (Sepp and Auld 1999). In comparison, the HACK method at best requires only a single F1 cross to yield a swap (e.g., 100% efficiency). In addition, the crossing schemes required for P-element swapping are more complicated, and since it requires the replacement of one P element for another, it cannot be applied to transgenic components generated using other transposons, such as piggyBac (Handler et al. 1998) or Minos (Metaxakis et al. 2005). Furthermore, since piggyBac and Minos elements excise precisely during transposition, transgenes generated by these elements are not amendable to similar transposase-mediated replacement strategies.

The QF2-driven expression patterns were similar to the GAL4 expression patterns and levels for most converted lines. However, there were exceptions. For example, GH146-QF2G4H generally drove weaker reporter expression than the original GH146-GAL4. In addition, some GMR-GAL4 lines, such as GMR10A06-GAL4, GMR71G10-GAL4, and GMR16A06-GAL4, exhibited very weak QUAS reporter expression after conversion to T2A-QF2 lines (Figure S9). Interestingly, QF2 transgenes generated based on these same GMR enhancer sequences were also very weak (O. Schuldiner, personal communication), suggesting that the problem is not with the activity of the T2A-QF2. Instead, it suggests that the intrinsic properties of the GAL4 or QF2 DNA sequences may influence expression of the targeted line.

Characterization of the HACK technique required investigation into the efficiencies of using different target and donor pairs for HDR. As such, it represents an in vivo system for investigating allelic/ectopic gene conversion in a model genetic animal. Gene conversion has been examined at a limited set of target genes and homologous donor loci. Due to intergene differences, the data sets could not be compared (Chen et al. 2007). The HACK system provides the first opportunity to comprehensively investigate how genomic location affects gene conversion across the genome. We identified target GAL4 sites that exhibited greatly increased (hot) or greatly decreased (cold) rates of HACK conversion. Of the 25 GAL4 lines we attempted to HACK, only 1 GAL4 target proved unable to convert in two attempts: en2.4-GAL4 (in crosses to the seven QF2G4H HACK donor lines on the second chromosome). Since ubiquitous or pan-tissue GAL4 lines can be converted, failure to convert was unlikely due to acquired expression of QF2. Instead, it is possible that en2.4-GAL4 represents an extreme cold spot. The reason for the observed variation in HACK efficiencies is unknown. One possible explanation is that local genomic structure could prevent Cas9-mediated excision at the DNA (Horlbeck et al. 2016). However, our data suggest this is unlikely. We found that cold spots (such as the OK107-GAL4 insertion site and attP2-GAL4) were efficiently targeted for DSB by CRISPR/Cas9. Instead, it suggests that HDR mechanisms are not equally efficient throughout the genome, and cold spots represent loci with repressed HDR activity. A previous study in yeast suggested a correlation between local transcription and HDR efficiency of the target, but the precise mechanism underlying this correlation remains unknown (Gonzalez-Barrera et al. 2002). A recent technique called mutagenic chain reaction (MCR) uses HDR to generate self-copying mutations in a target gene at high frequency (Gantz and Bier 2015). Our work suggests that MCR may not be equally applicable to all genomic loci.

The HACK technique also indicates that single integrated compatible donor sequences at distant locations can be used for HDR. For example, we were able to generate gene conversions to the X and fourth chromosomes using a donor sequence on the third chromosome. This suggests that techniques like MCR could be jump-started by a random integration of a compatible MCR transgene, which might prove to be easier to achieve in nonmodel organisms such as mosquitoes. Similarly, gene conversion using compatible HACK insertions might provide possible strategies for gene therapy in disease tissues (Chen et al. 2007) or as a reliable mechanism to introduce targeted genomic knock-ins in insect and mammalian systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Marr for splinkerette genetic mapping of the GAL4 and QF2G4H donor lines in this study. We thank Q. Liu, D. Task, and R. Reed for comments on the manuscript and the Potter laboratory members for discussions. We thank A. Parks at Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for providing a list of the frequently ordered stocks from 01/01/2013 to 10/01/2015. Stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (National Institutes of Health P40OD018537). We thank the Center for Sensory Biology Imaging Facility (National Institutes of Health P30 DC-005211) for LSM710 confocal microscopy. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (R01 DC-013070) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R21 NS-088521). The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: C.-C.L. and C.J.P. conceived and designed the experiments. C.-C.L. performed the experiments. C.-C.L. analyzed the data. C.-C.L. generated the DNA and transgenic reagents and materials. C.-C.L. and C.J.P wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: N. Perrimon

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.116.191783/-/DC1.

Literature Cited

- Bernstein K. A., Rothstein R., 2009. At loose ends: resecting a double-strand break. Cell 137: 807–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof J., Maeda R. K., Hediger M., Karch F., Basler K., 2007. An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 3312–3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. H., Perrimon N., 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-M., Cooper D. N., Chuzhanova N., Férec C., Patrinos G. P., 2007. Gene conversion: mechanisms, evolution and human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 762–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., et al. , 2013. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339: 819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao F., White B. H., 2012. A novel approach for directing transgene expression in Drosophila: T2A-Gal4 in-frame fusion. Genetics 190: 1139–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao F., Ironfield H., Luan H., Diao F., Shropshire W. C., et al. , 2015. Plug-and-Play Genetic Access to Drosophila Cell Types using Exchangeable Exon Cassettes. Cell Reports 10: 1410–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudna, J. A., and E. J. Sontheimer, 2014 The Use of CRISPR/cas9, ZFNs, TALENs in Generating Site Specific Genome Alterations (Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 546). Academic Press, San Diego. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels W. R., Johnson-Schlitz D. M., Eggleston W. B., Sved J., 1990. High-frequency P element loss in Drosophila is homolog dependent. Cell 62: 515–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels W. R., Preston C. R., Johnson-Schlitz D. M., 1994. Long-range cis preference in DNA homology search over the length of a Drosophila chromosome. Science 263: 1623–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi M., Evdokimova V. N., Cuenco K. T., Nikiforova M. N., Kelly L. M., et al. , 2012. Homologous chromosomes make contact at the sites of double-strand breaks in genes in somatic G0/G1-phase human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 9454–9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz V. M., Bier E., 2015. The mutagenic chain reaction: A method for converting heterozygous to homozygous mutations. Science 348: 442–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloor G. B., Nassif N. A., Johnson-Schlitz D. M., Preston C. R., Engels W. R., 1991. Targeted gene replacement in Drosophila via P element-induced gap repair. Science 253: 1110–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnerer J. P., Venken K. J. T., Dierick H. A., 2015. Gene-specific cell labeling using MiMIC transposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohl D. M., Silies M. A., Gao X. J., Bhalerao S., Luongo F. J., et al. , 2011. A versatile in vivo system for directed dissection of gene expression patterns. Nat. Methods 8: 231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Barrera S., Garcia-Rubio M., Aguilera A., 2002. Transcription and double-strand breaks induce similar mitotic recombination events in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 162: 603–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz S. J., Cummings A. M., Nguyen J. N., Hamm D. C., Donohue L. K., et al. , 2013. Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics 194: 1029–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz S. J., Ukken F. P., Rubinstein C. D., Thiede G., Donohue L. K., et al. , 2014. Highly Specific and Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-Catalyzed Homology-Directed Repair in Drosophila. Genetics 196: 961–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth A. C., Fish M., Nusse R., Calos M. P., 2004. Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage phiC31. Genetics 166: 1775–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjieconomou D., Rotkopf S., Alexandre C., Bell D. M., Dickson B. J., et al. , 2011. Flybow: genetic multicolor cell labeling for neural circuit analysis in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Methods 8: 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handler A. M., McCombs S. D., Fraser M. J., Saul S. H., 1998. The lepidopteran transposon vector, piggyBac, mediates germ-line transformation in the Mediterranean fruit fly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 7520–7525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horlbeck M. A., Witkowsky L. B., Guglielmi B., Replogle J. M., Gilbert L. A., et al. , 2016. Nucleosomes impede Cas9 access to DNA in vivo and in vitro. eLife 5: e12677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. D., Scott D. A., Weinstein J. A., Ran F. A., Konermann S., et al. , 2013. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 827–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Awano W., Suzuki K., Hiromi Y., Yamamoto D., 1997. The Drosophila mushroom body is a quadruple structure of clonal units each of which contains a virtually identical set of neurones and glial cells. Development 124: 761–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis G. S. X. E., Potter C. J., Chan A. M., Marin E. C., Rohlfing T., et al. , 2007. Comprehensive maps of Drosophila higher olfactory centers: spatially segregated fruit and pheromone representation. Cell 128: 1187–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenett A., Rubin G. M., Ngo T.-T. B., Shepherd D., Murphy C., et al. , 2012. A GAL4-Driver Line Resource for Drosophila Neurobiology. Cell Reports 2: 991–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., et al. , 2012. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337: 816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama T., Carlson J. R., Luo L., 2004. Olfactory receptor neuron axon targeting: intrinsic transcriptional control and hierarchical interactions. Nat. Neurosci. 7: 819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai S.-L., Lee T., 2006. Genetic mosaic with dual binary transcriptional systems in Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci. 9: 703–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-S., Wang R. W., Chang H.-H., Capurso D., Segal M. R., et al. , 2016. Chromosome position determines the success of double-strand break repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113: E146–E154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis R., Hazelrigg T., Rubin G. M., 1985. Effects of genomic position on the expression of transduced copies of the white gene of Drosophila. Science 229: 558–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber M. R., 2010. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79: 181–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metaxakis A., Oehler S., Klinakis A., Savakis C., 2005. Minos as a genetic and genomic tool in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 171: 571–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer B. D., Jenett A., Hammonds A. S., Ngo T.-T. B., Misra S., et al. , 2008. Tools for neuroanatomy and neurogenetics in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 9715–9720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port F., Chen H. M., Lee T., Bullock S. L., 2014. Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: E2967–E2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter C. J., Luo L., 2010. Splinkerette PCR for mapping transposable elements in Drosophila. PLoS One 5: e10168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter C. J., Tasic B., Russler E. V., Liang L., Luo L., 2010. The Q system: a repressible binary system for transgene expression, lineage tracing, and mosaic analysis. Cell 141: 536–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Sun J., Housden B. E., Hu Y., Roesel C., et al. , 2013. Optimized gene editing technology for Drosophila melanogaster using germ line-specific Cas9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 19012–19017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riabinina O., Luginbuhl D., Marr E., Liu S., Wu M. N., et al. , 2015. Improved and expanded Q-system reagents for genetic manipulations. Nat. Methods 12: 219–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Y. S., Golic K. G., 2000. Gene targeting by homologous recombination in Drosophila. Science 288: 2013–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepp K. J., Auld V. J., 1999. Conversion of lacZ enhancer trap lines to GAL4 lines using targeted transposition in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 151: 1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearin, H. K., I. S. Macdonald, L. P. Spector and R. S. Stowers, 2014 Hexameric GFP and mCherry Reporters for the Drosophila GAL4, Q, and LexA Transcription Systems. Genetics. 196: 951–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal M. L., Hartl D. L., 1996. Transgene Coplacement and high efficiency site-specific recombination with the Cre/loxP system in Drosophila. Genetics 144: 715–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney L. B., Couto A., Chou Y.-H., Berdnik D., Dickson B. J., et al. , 2007. Temporal target restriction of olfactory receptor neurons by Semaphorin-1a/PlexinA-mediated axon-axon interactions. Neuron 53: 185–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak J. W., Orr-Weaver T. L., Rothstein R. J., Stahl F. W., 1983. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell 33: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venken K. J. T., Schulze K. L., Haelterman N. A., Pan H., He Y., et al. , 2011. MiMIC: a highly versatile transposon insertion resource for engineering Drosophila melanogaster genes. Nat. Methods 8: 737–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara M., Ito K., 2000. Improved Gal4 screening kit for large-scale generation of enhancer-trap strains. Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 83: 199–202. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Drosophila lines are available at Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center or upon request. Plasmid constructs are available at Addgene or upon request.