Abstract

The diagnosis of a child with autism has short- and long-term impacts on family functioning. With early diagnosis, the diagnostic process is likely to co-occur with family planning decisions, yet little is known about how parents navigate this process. This study explores family planning decision making process among mothers of young children with autism spectrum disorder in the United States, by understanding the transformation in family vision before and after the diagnosis. A total of 22 mothers of first born children, diagnosed with autism between 2 and 4 years of age, were interviewed about family vision prior to and after their child’s diagnosis. Grounded Theory method was used for data analysis. Findings indicated that coherence of early family vision, maternal cognitive flexibility, and maternal responses to diagnosis were highly influential in future family planning decisions. The decision to have additional children reflected a high level of adaptability built upon a solid internalized family model and a flexible approach to life. Decision to stop childrearing reflected a relatively less coherent family model and more rigid cognitive style followed by ongoing hardship managing life after the diagnosis. This report may be useful for health-care providers in enhancing therapeutic alliance and guiding family planning counseling.

Keywords: autism, diagnosis, family functioning and support, family planning, family vision

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong disability in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, and restrictive and repetitive behaviors. The diagnosis of ASD has a significant impact on the well-being of the entire family. It is known that families who have a child with ASD report higher levels of stress than families who have a typically developing child, as well as families with a child with Down syndrome, physical disability, or a chronic health condition (Baker-Ericzen, 2007; Bouma and Schweitzer, 1990; Donovan, 1988; Gray, 1994; Hayes and Watson, 2013; Mugno et al., 2007; Olson and Hwang, 2002; Sanders and Morgan, 1997). Being a parent to a child with ASD involves dealing with child behavioral problems in the context of limited access to care in most environments. Families must actively seek out therapeutic opportunities and implement recommendations to be advocates for their child with ASD; this often occurs within familial and cultural stigma and financial strain.

The effects of a significant stressor, such as the diagnosis of ASD, on a person and family have been conceptualized by various models. These models usually share three conceptual domains: (1) the initial stressor, (2) mediators of the ability to deal with the stressor, and (3) the outcome (e.g. adaptation) (Patterson, 2002). McCubbin and Patterson’s multivariate Double ABCX model has provided a basis for investigating processes of adaptation among families of children with ASD, particularly the adjustment of mothers (Bristol, 1987; Manning et al., 2011; Pakenham et al., 2005). The model suggests that families going through a primary stressor have to deal simultaneously with multiple demands. Meeting the demands of the stressful situation involves mobilizing the family’s adaptive resources, mainly soliciting social support and forming a constructive cognitive appraisal of the situation. Coping is a bridging concept, defined as the overall cognitive and behavioral efforts to restore balance in family functioning. Adaptation, often used interchangeably with adjustment, is the possible continuum of outcomes (McCubbin and Patterson, 1983). The Family Adjustment and Adaptation Response (FAAR) Model (Patterson, 1988) emphasizes how the stressors themselves, as well as the resources and the response, are the products of three interfacing systems: individual, family, and community (Patterson, 1988). In this model, family adaptation is defined as the process of restoring balance between capabilities and demands between both family members and the family unit and between the family unit and community (Patterson, 2002). The term resilience appears in discussions of adaptive responses to stress. It is defined most commonly as the phenomenon of doing well in the face of adversity (Walsh, 1998). Thus, the term resilience, in the light of the family stress theories, is not a new concept but simply shifts the focus of adaptation toward family’s success and competence (Patterson, 2002). For the purpose of this study, we will use the term adaptation, defined as the process of restructuring family characteristics to adjust to the impact of a major life stressor (Patterson, 1988).

There is a growing body of literature about the multiple factors that influence a family’s adaptation process. Most of this literature highlights parental maladaptation and negative outcomes. Raising a child with ASD is associated with psychological problems in parents such as deterioration of self-esteem, feelings of helplessness, depression, anxiety, and marital dissatisfaction (Cohen and Tsiouris, 2006; DeLong, 2004; Gray and Holden, 1992; Hoppes and Harris, 1990; Marvin and Pianta, 1996; Risdal and Singer, 2004; Sharpley et al., 1997). Some use the term tragedy to describe the lifelong hardship of parenting a child with a developmental disability, like ASD (Ferguson, 2001). A more limited number of studies has focused on positive mediators and adaptive resources, promoting restoration of positive balance and adjustment, including personal growth, increased tolerance, compassion, a change in philosophical and spiritual values, and, ultimately, becoming a better parent (Erwin and Soodak, 1995; Nelson, 2002; Rolland, 1998; Scorgie and Sobsey, 2000; Stainton and Besser, 1998).

Most studies on parental responses have focused on measuring specific factors that contribute to the outcome of the adaptive or maladaptive response to the birth of a child with ASD (Bekhet and Zauszniewski, 2013; Faso et al., 2013). There is little research, most of it qualitative, that seeks to explore the broader parent perspective and evolving life experience of what it is like to raise a child with ASD (Corcoran et al., 2015; Hoogsteen and Woodgate, 2013; King et al., 2006; Safe et al., 2012). Rutter (2007) pointed out that when studying parental reactions to adversity, it is important to consider the life span perspective in addition to past and present mental operations, and individual traits and experiences. This type of exploration allows detecting more expansive themes such as isolation, confusion, lost dreams, and change in parent’s self (Cashin, 2004; King et al., 2006; Midence and O’neill, 1999; Woodgate et al., 2008).

Little is known about how the experience of having a child with ASD affects parents’ decisions about future childbearing and family planning, and how it is related to the overall process of adaptation to the diagnosis. Results from a population-based cohort showed that families whose first child had ASD, were less likely to have a second child, at a rate of 0.668 compared to that of control families (Hoffmann et al., 2014). In a sample of 10 Japanese mothers of children with ASD, the decision making process about subsequent pregnancies suggested unique cultural and societal influence, causing extreme psychological conflicts when considering a second child (Kimura et al., 2010). As far as we know, the Kimura study is the only research on this topic. Since it has a strong cultural component, it does not clarify the reproductive decision making process for mothers of children with ASD outside of Japan.

This study seeks to better understand family planning decisions and transformation in family vision in the United States, after a young child was diagnosed with ASD, by elucidating attitudes and experiences that differentiate mothers of children with ASD who do not go on to bear more children from those who do. Although family planning decisions involve both parents, we chose to focus on mothers for two reasons. First, studies have shown that stressful life events cause more psychological distress in women than they do in men, especially when these events affect family and friends, and they also tend to use different coping resources and strategies (Aneshensel, 1992; Thoits, 1995). Second, mothers are usually the ones providing the majority of child care. We interviewed biological mothers about their fantasized family vision before having children, and after the diagnosis of ASD in a first born child. We considered individual views and values. We also looked at parental initial concerns about development, diagnostic process, and overall psychological adjustment to diagnosis, in order to obtain a comprehensive understanding about how such a complex decision is made.

Methods

Participants

Participants in this study were mothers of children with a clinical diagnosis of Autistic Disorder or Pervasive Developmental Disorder–Not Otherwise Specified based on child observation, direct testing, and parent interview (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), who took part in a National Institutes of Health (NIH) study of early development of children 24 to 59 months of age with ASD. Inclusion criteria for the original study included Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale–2nd Edition (VABS-II; Sparrow et al., 2005) motor standard scores >70. ASD was defined as meeting criteria for autism or ASD on module 1 (no words, N = 18; some words, N = 38) or module 2 (N = 29) of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Gotham et al., 2007; Lord et al., 2000). Excluded from the original study were children with serious medical or neurological history/conditions; serious motor impairments; uncorrected hearing or vision loss; birth weight <1500 g and/or gestational age <34 weeks; prenatal exposure to known neurotoxins, tobacco, alcohol, or category C/D/X medications; diagnosis of known genetic syndrome related to ASD; English not the primary language; adoption; maternal diabetes; and multiple birth.

For this study, biological primary caregiver mothers of first born children with ASD were identified from their prior participation in the NIH study.

Of mothers of the 85 children in the original study, 54 were mothers of first born children with ASD. Mothers in which the second or later born child had ASD or with a second or third child with ASD were excluded (N = 31), assuming it was likely that they had already completed their family planning. From this sample, 54 biological primary caregiver mothers whose first born biological child was diagnosed with ASD were mailed letters for this study. The final sample included 22 mothers: 7 mothers had one child with ASD and no other children, 15 mothers had one ASD child and one (n = 13) or two (twins, n = 2) later born full-sibling children. A total of 18 mothers lived with their child’s biological father. There was an equal ratio of verbal and low verbal children among the families with one child and more than one child. Mothers were interviewed within 2–5 years of the initial ASD diagnosis when the ASD child was 48 to 84 months old. There was no difference among the two groups of families in the average time passed since the child was diagnosed with ASD. We considered this an appropriate time range as this is the time frame in which reproductive decisions are usually being made. As part of the original study, all mothers had been offered counseling about the risk of ASD in future children, according to the most up-to-date research of the time.

Participants came from varied socio economic, educational, and racial backgrounds (36% minority) and included families living in poverty and families in top earning categories. Mothers tended to be well educated, all of them having some amount of post high school education.

Procedure

Grounded Theory qualitative approach

Given the sensitivity and complexity of the issues involved, we chose a Grounded Theory (GT) qualitative approach. This approach seeks not only to understand but also to build a substantive theory of the phenomenon of interest (Merriam, 2009). It enables the researcher to interpret the varied expressions of human experience within the context of social environment (Strauss, 1993) and identify connections between social and psychological aspects of human experience. The themes and concepts used to explain the GT are formed using a process of axial and selective coding (Corbin and Strauss, 2008) creating a matrix that depicts how concepts are related to each other and represented in the data.

Interview

A semi-structured interview, based on themes identified in previous studies exploring parental experience (King et al., 2006; Woodgate et al., 2008), was developed for the purpose of this study. Follow-up questions were specific to the individual answers provided. Each interview lasted about 1.5–2 h and was audiotaped.

The interviews were conducted in person, by an experienced child psychiatrist (N.N.), at the mother’s primary residence. The interview was designed to explore the multidimensional topics of lived experience before, during, and after the diagnosis, and the processes the families went through to reach reproductive decisions. Mothers were specifically asked about family of origin as well as original family vision, developmental concerns and ASD diagnosis, the process of adaptation to having a child with ASD, and future childbearing plans.

Data analysis

Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. The initial study questions were refined through an iterative process of data collection and analysis that followed standardized qualitative methods utilizing a GT approach (Charmaz, 2014). Two of the authors (N.N. and A.J.) independently read, re-read, and coded the transcripts. Transcripts were analyzed line-by-line creating brief descriptive codes. Initial codes were then used to categorize data into broader focused codes. An overall theoretical framework was created by analyzing relationships between focused codes. Categories considered to represent key themes within the data were elevated to the status of “concepts.” New data was continually compared against codes that had already been developed in order to find points of similarity and divergence and to ground the developing theoretical model. Throughout this process, the first author (N.N.) kept memos of observations and reflections about how a theoretical framework could be developed from the data. These hypotheses were tested against existing data and new data gained from subsequent interviews.

Results

The findings were divided into three sections, representing three important phases along the family planning timeline: (1) family vision and its origins before having children; (2) birth of first child followed by developmental concerns and adaptation to the ASD diagnosis; and (3) subsequent family planning decisions. The core categories and related themes for each section will be described, accompanied by illustrative quotes. Names were redacted and replaced with the individual’s role in the family (e.g. “Child” refers to the child with ASD, “Sib” refers to the subsequent born child, and “Husband” refers to the spouse/partner of the mother).

Family vision and its origins before having children

All mothers in this study reported wanting to have more than one child, with the majority planning on two children and some reporting wanting two or more. Reasons to want a second child included a desire for their children to have siblings and the hope that the children and their future families would be a source of joy and support when parents themselves age. All the participants preferred a gap of about 2 to 3 years between the children, with many mothers saying that a small gap would help to create a deeper bond between children. Mothers talked about the role of their spouse in the creation of the family vision. Most of them shared the vision with their spouse, foreseeing the future together, and planned everyday details together. Most mothers had confidence in their ability to fulfill the dream. In those already experiencing marital discord, mothers did not experience the creation of a family vision as a shared one with their spouse.

Family of origin model

Mothers were asked about different aspects of their own family of origin including composition, relationships with parents and siblings, and family’s ability to cope with stress. Some described a wish to create a family similar to the one they had grown up in. They expressed warm, appreciative feelings of their family of origin, and felt that they successfully dealt with challenges. These mothers’ vision was to create a similar family, reflecting a high level of internalization of the positive aspects, values, and standards of their original family:

I am the youngest of three. The three of us, five years apart. So I was like I will have three children, and they will be about five years apart, even though I knew my children would have a different childhood than mine. I think there were things I wanted to mimic from my family because I feel like we had a great family.

Other participants described problematic and complicated family systems: dealing with harsh parental relationships, poverty, and parental mental and physical illness. These mothers reported a desire to create a different kind of family with different patterns of relationships and modes of dealing with challenges, reflecting a coherent internalized desired family model, different from their own experiences:

In my family there are many mental illnesses. The home I was raised in was different. I wasn’t listened to. My mother has some sort of personality disorder. I was always treated as an extension of her and I existed to prop her up. That’s why I was always sensitive about that. I didn’t want to be manipulating towards my children, so that I can look good to other people. I try to stay aware of that.

The majority of participants shared the ability to observe and reflect on their past relationships and establish a coherent internalized desired family vision. However, some mothers could not reflect back on their childhood environment in a cohesive way. They described their family of origin without connecting past experiences to present thoughts. Their own family vision was similarly fragmented and incoherent:

I didn’t know what a family actually looked like. I grew up with a single mom and I visited my dad whenever he wanted me to. And they didn’t have a healthy relationship. So I just, I didn’t really know. I just wanted multiple children. I didn’t really think of how I would pay for children, I just wanted a big family.

Future plans: flexibility versus rigidity

In addition to the influence of past family experiences, the flexibility of the family vision was also important. When mothers reflected on past family experiences and desired future vision, they differed by the level of cognitive flexibility expressed. Some mothers could describe their family vision and its connection to the past in a flexible way, allowing for different options and perspectives:

My husband and I are both only children, so the sibling relationship is something we don’t know a lot about. I grew up accepting how things were … When we got married we had a loosely held idea, that we wanted two, but we wanted to start with one and see how that kind of went. I felt comfortable only having one if that was the way it turned out.

For others the primary family vision was more rigid:

Having a family meant you could not do crazy things, you had to be responsible. It was all very thought out. If we make mistakes, we do not have the ability to undo them. We really thought things through. The vision was to have two children about 2.5 years apart and for me not to work. And when they went to school I would work. Later, I wanted them to get a degree. I wanted them to go to Harvard.

The various degrees of flexibility, expressed by the mothers when describing the family vision along with the characteristics of the internalized family of origin model of upbringing, are the resources that families use when approaching change in life circumstances.

Adaptation to ASD diagnosis

All families had gone through the painful process of acknowledging that their child was not developing as expected, followed by a diagnosis of ASD, and the need to adapt and develop a new life routine. Six main themes were detected from the mothers’ descriptions of their experience during that challenging phase: guilt and blame, focus on the present moment, future fear and confusion, competence, isolation, and support. Each of these themes naturally seemed to interlink with another theme in the course of coding the interviews. We identified three dialectic response style processes that create a unified model of parents’ emotional response and adaptability to the circumstances. In the section that follows, we address each of the three response styles in more detail.

Guilt and blame versus present moment focus

Guilt and blame

Almost all mothers described some degree of guilt emerging during the phase after diagnosis. For some, guilt was focused on their perceived contribution to their child’s ASD. There were some mothers that were preoccupied with guilt. They frequently ruminated about the past, which seemed to dominate their thoughts about their child and themselves:

I was doing stuff that may cause it. Everything I was doing people said would cause autism. My Sister said watching TV would cause him autism. I shouldn’t place him in front of the TV. But watching TV was the only way to help him fall asleep. The TV was my savior … Maybe it is because he would watch so much TV or he was getting vaccinated or I didn’t talk to him much … Talking to [Child] was not doing any good and cause frustration. I felt that was me being a bad mom. I wasn’t doing anything to prevent it. I was doing everything to possibly have it happen. I wish I could go back and no TV, no vaccinations, and talk to him all of the time.

Did I do something? I try to recount my steps backwards. Should I have been down there communicating with him and engaging with him more? I didn’t know. For me there is just a mother guilt.

Other mothers felt guilty for not noticing that something was wrong earlier and not intervening earlier:

He was very content when being alone. So content, just sitting and playing by himself. He was our first child so we didn’t think that it was super weird. We ended up wasting another year until getting the diagnosis. In the meantime things were going downhill in preschool. And what did I do? Nothing.

A few mothers were preoccupied not only with their own guilt but also blamed others for their child’s situation, for example, the nonfunctioning health system or insurance companies:

I feel like I am in a perpetual angry state. There is always just part of me that is angry/upset, not at my son but at a community or a system that is not giving me what I feel I need.

For others, religion was a source of frustration and they blamed God for their misfortune:

After [Child] was diagnosed I was really angry with the God. My frustration was only towards Him. Why would you do that to the people who really believe in you?

Focusing on the present moment

In contrast to the excessive guilt, blame, and preoccupation with the past, other mothers described the ability to focus on the present moment which provided moments of joy, gratitude, appreciation, and connection. This present focus seemed to allow mothers to focus on what the child needs and how he can grow, instead of what he will never be able to accomplish:

I don’t have a master plan. I am just taking it one day at a time. I have not been doing a lot of future projections in my mind, but just trying to address what I see going on now.

There were times I felt why is this our story and there are things that maybe someday will work for us, but not today. But this is life, and this is the happiest I have ever been. I am always so thankful. Every day you get a new chance.

Future fear and confusion versus competence

In addition to shifting between different degrees of guilt about the past and present focus, mothers also varied in their ability to balance fears for the future with a sense of competence.

Future fear and confusion

Adaptation to the diagnosis and subsequent new life routine was more difficult for some mothers. They described a loss of direction, confusion, and fears about the future. They felt dispossessed of their basic maternal assets: the belief that they can take the best care of their child, understand him, and make him thrive. The future, instead of bringing their child all the best they hoped for, seemed threatening and unclear:

I was shocked. They said he is moderate … And I have this step brother that is severely autistic. I knew how hard it will be if we can’t get him talking, if we can’t get him out of moderate and into mild. He will be like my brother. All these people have all these high needs and I am only me and I don’t stretch that far.

For another mother, a future that was previously well planned according to a coherent set of values suddenly became scary and vague. She was left with not knowing what she could hope and look forward to:

We were planning on taking him to kindergarten earlier. Now all of a sudden your child is in special education. You don’t know what his future is going to be. From looking forward to planning for his college, your world changes into this different world which you’re following which has no target, no end point. You don’t know when the turn is going to come.

Competence

Some mothers described the diagnosis as a starting point for gaining knowledge and understanding about what ASD actually is. This led to a better understanding of how their child experiences the world and what his needs are, leading to the establishment of a sense of competence as a parent:

I’m definitely sad for him that he has this diagnosis hanging over his head. But if anything the diagnosis to me was a relief, so I didn’t feel negatively about it. Obviously it’s a change from what you expect. But to me it was, okay this is what it is, and so we can work with him to not fix it, because I don’t think you can ever … I don’t think there’s anything to fix. We can just work with him to make him understand the world in his own way. It gave us a direction.

One mom described how her religious beliefs helped to establish a sense of competence:

The things that really made me feel okay was, you know, “God won’t give you something you can’t handle” which really lifted me up, like “okay, this is doable.”

One might think that the availability of knowledge has a critical role in assisting parents in establishing a sense of competence over confusion. However, this was not as important as the parental ability to process new information and then use this new information to better understand their child:

We watched so many videos and a lot of books about Autism behavior and the therapies. It was just like a mess. Literally like a mess.

[A year later], I remember watching a video about a father … I still remember watching it and he said, he tried to fix his son, but he never realized that it’s not going to be fixed, it’s something that you have to live with. I think the first year we were trying to do the same thing. I really liked what he said at that time, and my husband and I had a talk. Then came the time we started living with it.

Isolation versus support

Just as mothers varied in the degree of guilt versus present focus and future fear versus competence, the sense of isolation versus support was a key component of their experience during these challenging times.

Isolation

Mothers described different reactions by family and friends upon hearing about the diagnosis. For many mothers, these responses created a profound sense of isolation. For others, isolation emerged when they had to deal with the overwhelming reality of spending most of their time indoors because of the difficulty handling their child outside. It was difficult for others to understand that ASD is a spectrum with varying degrees of severity. Some friends assumed that the diagnosis was a devastating catastrophe leading to expression of excessive sympathy or pity:

They don’t know what to say, so their response is just “Oh My God, I am so sorry, how are you doing? I’m so impressed with the way you are handling this.” I’m like am I supposed to be falling apart here? How am I supposed to be reacting? What do people expect? It adds this isolating, and disorienting aspect.

Others, mainly mothers of higher functioning children, described the opposite reaction, disbelief and denial, as isolating:

We had a pretty negative response. Nobody really believed us. I have heard “You are labeling him, this is not good.” We even have some close friends who are doctors and they asked, “Are you sure?”

One mother described an everyday reality in which going outside is a struggle:

I couldn’t take him anywhere because he would run off and scream and have a tantrum and it would be a two hour ordeal. So we would just lock ourselves in. I felt closed off to other people. Like he and I are in this world where everyone else is an outsider.

For another, the support in everyday tasks was appreciated, but she did not feel emotional support:

Our family is very supportive of us. They watch him and they all love him very much. They would throw their lives in front of a bus for him but I do not think any of them understand the stress that I am going through. They don’t realize how exhausting it is, how every day is a battle.

Support

The mothers in this study identified different circles of support: spouse, parents, religion, social networks, support groups, and therapists. Two types of support were recognized: emotional support and physical assistance in everyday tasks. Most mothers emphasized the value of emotional support. The spouse was the most important source of emotional support. High levels of spousal support seemed to mitigate the effects of isolation:

I feel like [Husband] listened to me and listened to me and responded to my feelings of guilt and grief. He was always the cheerleader and always told me, “You know, you’re doing a good job finding the best services for our kids. They’re lucky to have you.” So, he does give me that kind of support.

Without spousal support, the world was seen as more isolating:

I am handling most of the childcare burden since [Husband] is usually working and busy. He doesn’t worry and I worry so much. I am not able to share my feelings with him. It has affected our relationship because I don’t feel like we are on the same page.

Meeting other parents, social networking, and the child’s therapists were meaningful sources of support for many mothers. This led to a feeling of not being alone and of going through something that other people had gone through before and managed:

I didn’t post anything, but just to know that others were in the same position as I, was supportive. I’m not alone. If they can do it, I can do it.

Family planning decisions after first child diagnosed with ASD

Among our sample of 22 women, 15 chose to have another child and 7 decided not to. Of note, the severity of child’s ASD symptoms was similar in these two groups of mothers. Some of the mothers that decided to have another child had a non/low-verbal ASD child whereas others had higher functioning children. This was also the case for the mothers that did not have another child.

When going through the process of adaptation to the ASD diagnosis, each of the mothers had her own personal “map” in terms of her location on each of the three response dimensions described previously (i.e. guilt versus present moment, future fear versus competence, and isolation versus support), which informed her future family planning decisions. Although each mother had her own unique life circumstances and decision making process, we will describe the main features that were identified.

The decision to have another child

The majority of mothers decided to have a second child. These mothers came from various backgrounds but had a coherent internalized desired family model before having children and expressed a relatively high level of flexibility when commenting on future expectations. When considering the three response dimensions, these mothers had at least one of the more adaptive poles overweighing the less adaptive. Overall, there was a sense of effectively accommodating to their life situation. Thus, when considering the choice to have more children, they were focused on the present, felt supported and competent in handling everyday challenges, and connected to their earlier values and family vision. They chose to fulfill their desire to have more than one child, while simultaneously recognizing that things had changed, and family life might look very different from their early vision:

Initially I was thinking more close together, maybe two years apart. My husband was ready earlier to add to the family than I was. Most of the childcare falls on me and I really had to be ready. I did not have enough reserves for another child or to manage with transition-to help my [Child] through that. Once he was stabilized then I was ready to have [Sib].

I imagined taking a few months off and going back part time and having childcare. After having [Child] I felt I couldn’t go back. I am really happy because I don’t think he would have done well in a daycare and now I am able to spend so much time with both of them and to get to know them.

The decision not to have another child

The mothers who decided to not have a second child came from various backgrounds as well. These mothers presented with a less coherent family vision and lower levels of flexibility while discussing future plans. When adjusting to the ASD diagnosis, they tended to feel isolated and confused. They tended to struggle with overwhelming fear about their child’s future as well as feelings of guilt and blame. When these mothers were considering whether to have more children, they felt a lack of control over their lives. They thought that they would not be able to manage with a bigger family, since they were struggling to manage as it is. Most of them expressed sadness about their decision. They reported feeling disconnected from their early family vision—it was no longer relevant to their lives:

My whole life I wanted two. But it has been so hard. [Child] use to run out and if I had two, which way do you go? If we had two kids, how would we do that? Maybe it was a mistake to have kids. In your mind you don’t see this. That’s why I don’t want to do two kids. My Husband understands that it is mostly on me. I am doing about 99% of the work. I could never have two.

I would have loved to have one more child, but we now understand what it takes. Our family might be destroyed. We could not give both of them what they need, and then everyone would loose. I still wish we could have another one. It is totally illogical. My heart hurts. [Child] is 6 and I have refused to give anything away. I am getting older and older, and we haven’t had another child but I can’t get rid of [Child]’s things.

Recurrence risk and ASD heritability

ASD heritability knowledge factored into the decision making process for the minority of mothers. One mother said that she would have another child only if she could do a genetic test that would prevent the possibility of recurrence. Two others said that the possibility of recurrence was among the main factors in their decision to not have more children. One mother, who already had a second child, reported that if she knew what the recurrence rates were at the time, she would not have taken the chance and had him. However, for the majority of mothers, recurrence was an option they knew about, but it did not play a major role in their family planning decision. For most, the updated knowledge was available, but they were not very interested in the numbers:

There is a little bit of fear about that (having another child with autism), but at the same time we feel like we know so much, so if there were anything happening, we would be so much better equipped to do something.

Look how happy [Child] is. He is so happy, even though he has autism. And I just think, now that we’re in a good place with [Child], we know what to expect. He’s just brought us so much joy, that how could we not want another person to bring joy into the house?

Discussion

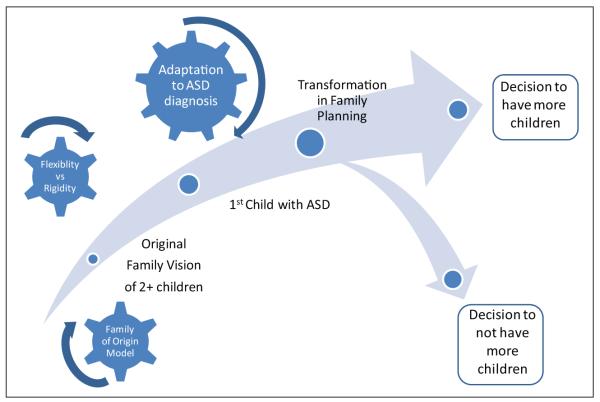

This study focused on family vision and family planning decisions of mothers with a newly ASD diagnosed child. Our findings suggest that coherence of early internalized family vision, level of cognitive flexibility (Flexibility/Rigidity), and response to the child diagnosis (Guilt and Blame vs Present Focus, Future Fear and Confusion vs Competence, and Isolation vs Support) were highly influential in the family planning decision making process (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of transformation in family vision and family planning decision process.

This study supports past findings of how a sense of competence, taking it one day at a time, and the emotional support of the spouse can promote maternal well-being while raising a child with ASD (Bristol et al., 1988, 1993; Teti and Gelfand, 1991). Almost all studies examining the process of adaptation are cross-sectional which is problematic when investigating “a process.” However, Benson has found, in a recently published longitudinal study, that maternal competence, in particular, did not change over time, and that a mother’s belief about her ability to successfully parent her child with ASD was stable (Benson, 2014). In regard to the role of cognitive flexibility, it is the basic condition for the formation of cognitive reframing, which is the ability to positively alter how a stressor is perceived. Cognitive reframing was found to increase maternal well-being and moderate the impact of child’s behavior on maternal outcome (Benson, 2010). Our study also highlights the tendency for mothers to blame themselves for their child’s problems and have their identities threatened by illness and disability in their children, which has been shown in other studies (Anderson and Elfert, 1989; Kuhn and Carter, 2006). In addition, effects of isolation, confusion, and fear may take over the parental experience (Kenny and Meena, 1999; Woodgate et al., 2008).

The data collected in our broad qualitative investigation integrate these previously examined components to a unified model of maternal functioning and adaptability, and suggest that is highly related to family planning decisions. Maternal adjustment to the diagnosis of ASD can be characterized into a spectrum of dialectic response styles: (1) Guilt and Blame versus Present Moment Focus; (2) Future Fear and Confusion versus Competence; (3) Isolation versus Support. Present focus, competence, and support all enhance maternal adaptability, whereas guilt and blame, confusion and fear, and isolation can lead to maladjustment. Using the FAAR model terminology, these are the mediators that come into play to restore a new balance between demands and adaptation. The outcome, the new level of maternal adaptability, is a key part of the family planning decision making process. Furthermore, the unique “map” of response styles that characterize each mother seems to be related to the internalized family of origin model and their own level of cognitive flexibility. The decision about future childbearing was the end point of a pathway that was built upon the characteristics of the early family vision, and transformed according to the nature of mothers’ response style to the diagnosis as illustrated in Figure 1.

In our sample, every mother’s ideal vision was to have more than one child. The decision to go on and have additional children after the first child’s diagnosis, reflects a high level of maternal adaptability to the diagnosis, built upon a solid internalized family model and a flexible approach to life. These factors seem to be crucial for obtaining satisfaction from parenthood, and for reestablishing direction, hope, and a feeling that life is on track. The decision to stop childrearing reflected a less coherent family model and more rigid cognitive style, followed by ongoing hardship managing life after the diagnosis.

Child adaptive functioning was not a key factor in later family planning decisions. Another factor that did not play a major role in family planning was knowledge about ASD heritability and recurrence rate. ASD is unique among other developmental disorders, since known genetic syndromes are responsible for the minority of the cases, leaving more than 80% of families without a definitive cause and an uncertain risk of recurrence (Carter and Scherer, 2013). In contrast, family planning decisions among families with a first born child with Cystic Fibrosis, found that only 47% of the families had another pregnancy, and that this effect was attributed mostly to the knowledge of recurrence risk (Evers-Kiebooms et al., 1990). In our study, most mothers did not know the up-to-date recurrence rate prior to making decisions, nor did they express high interest in knowing. Most mothers who decided to have another child felt that if their second child had ASD, they would be able to handle it well, expressing confidence in their problem solving ability.

Limitations

This was a retrospective investigation, with a cross-sectional design as the interviews were conducted at one time point, 2 to 5 years from the time of the developmental assessment and diagnosis. Thus, this design does not allow an understanding about change over time of parents’ perspective. Since our sample consisted only of mothers, further study is needed to investigate father’s perspective. This study should also be appreciated in the cultural context of the United States, though there was significant racial and economic diversity in this sample of mothers.

Conclusion

This qualitative investigation of family planning decisions provides better understanding of the transformation of the maternal family vision after the diagnosis of a child with ASD. For the mothers in this study, reestablishing the family vision and adapting to their new situation, was a process deeply influenced by who they were before they had a child and what had happened to them while grappling with the diagnosis of ASD. The understanding of the characteristics of mothers and families dealing with raising a child with ASD, their needs and struggles, response styles, and values, is essential for creating a meaningful dialogue between parents and service providers. It can help providers adopt a better family-centered model of intervention and tailor service delivery that will suit family’s needs. Providers discussing family planning with the families can benefit from the understanding that it is highly related to the process of adaptation to the diagnosis, and that the process of reconciliation of family vision to current circumstances, may be an added source of distress and challenge.

Acknowledgements

We thank the families who participated in the SPARCS study. Additional contributions were provided by Sarah Corrigan, Sheila Ghods, Brooke Zappone, and the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, Econometrics and Programming Core at Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

Funding

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development [R01 HD064820 Webb]; and the Crown Family Foundation (Navot).

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–IV) 4th ed American Psychiatric Press Inc; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JM, Elfert H. Managing chronic illness in the family: women as caretakers. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1989;14:735–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS. Social stress: theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology. 1992;18:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Ericzen MJ. Child demographic associated with outcomes in community-based pivotal response training program. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions. 2007;1:52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet AK, Zauszniewski JA. Psychometric assessment of the depressive cognition scale among caregivers of persons with autism spectrum disorder. Archive of Psychiatric Nursery. 2013;27:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson PR. Coping, distress, and well-being in mothers of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2010;4:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Benson PR. Coping and psychological adjustment among mothers of children with ASD: an accelerated longitudinal study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(8):1793–1807. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouma R, Schweitzer R. The impact of chronic childhood illness on family stress: a comparison between autism and cystic fibrosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1990;6:722–730. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199011)46:6<722::aid-jclp2270460605>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristol MM. Mothers of children with autism or communication disorders: successful adaptation and the double ABCX model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1987;17(4):469–486. doi: 10.1007/BF01486964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristol MM, Gallagher JJ, Holt KD. Maternal depressive symptoms in autism: response to psychoeducational intervention. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1993;38(1):3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol MM, Gallagher JJ, Schopler E. Mothers and fathers of young developmentally disabled and nondisa-bled boys: adaptation and spousal support. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24(3):441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Carter MT, Scherer SW. Autism spectrum disorder in the genetics clinic: a review. Clinical Genetics. 2013;83(5):399–407. doi: 10.1111/cge.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashin A. Painting the vortex: the existential structure of the experience of parenting a child with autism. International Forum of Psychoanalysis. 2004;13:164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed SAGE; London: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen IL, Tsiouris JA. Maternal recurrent mood disorders and high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36(8):1077–1088. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran J, Berry A, Hill S. The lived experience of US parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2015 Mar 27; doi: 10.1177/1744629515577876. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong R. Autism and familial major mood disorder: are they related? The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2004;16(2):199–213. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan AM. Family stress and ways of coping with adolescents who have handicaps: maternal perceptions. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1988;92:502–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin EJ, Soodak LC. I never knew I could stand up the system: families’ perspectives on pursuing inclusive education. The Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1995;2:136. [Google Scholar]

- Evers-Kiebooms G, Denayer L, Van Den Berghe H. A child with cystic fibrosis: subsequent family planning decisions, reproduction and use of prenatal diagnosis. Clinical Genetics. 1990;37:207–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1990.tb03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faso DJ, Neal-Beevers A, Carlson CL. Vicarious futurity, hope, and well-being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013;7(2):288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson P. Mapping the family: disability studies and the exploration of parental response to disabilities. In: Albrecht GL, Seelman KD, Bury M, editors. Handbook of Disability Studies. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. pp. 373–395. [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Risi S, Pickles A, et al. The autism observation diagnostic schedule: revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(4):613–627. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DE. Coping with autism: stress and strategies. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1994;15:102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gray DE, Holden WJ. Psychosocial well-being among the caregivers of children with autism. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 1992;18:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SA, Watson SL. The impact of parenting stress: a meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(3):629–642. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JT, Windham GC, Anderson M, et al. Evidence of reproductive stoppage in families with autism spectrum disorder: a large, population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(8):943–951. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogsteen L, Woodgate RL. The lived experience of parenting a child with autism in a rural area: making the invisible, visible. Pediatric Nursing. 2013;39(5):233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppes K, Harris SL. Perception of child attachment and maternal gratification in mothers of children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990;19:365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny M, Meena O. The experience of parents in the diagnosis of autism: a pilot study. Autism. 1999;3:273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Yamazaki Y, Mochizuki M, et al. Can I have a second child? Dilemmas of mothers of children with pervasive developmental disorder: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2010;10:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JA, ZwAigenbaum LZ, King S, et al. A qualitative investigation of changes in the beliefs systems of families of children with autism or Down syndrome. Child: Care and Health Development. 2006;32:353–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn JC, Carter AS. Maternal self-efficacy and associated parenting cognitions among mothers of children with autism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:564–575. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Hambrecht L, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associates with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(3):205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin HI, Patterson JM. The family stress process: the double ABCX model of adjustment and adaptation. In: McCubbin HI, Sussman M, Patterson JM, editors. Social Stress and the Family: Advances and Development in Family Stress Theory and Research. Haworth; New York: 1983. pp. 7–38. [Google Scholar]

- Manning MM, Wainwright L, Bennett J. The double ABCX model of adaptation in racially diverse families with a school-age child with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41(3):320–331. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin RS, Pianta RC. Mothers’ reaction to their child’s diagnosis: relations with security and attachment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:436–445. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam S. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Jossey-Bas; San Francisco, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Midence K, O’neill M. The experience of parents in the diagnosis of autism. Autism. 1999;3:273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Mugno D, Ruta L, D’arrigo VG, et al. Impairment of quality of life in parents of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorder. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AM. A metasynthesis: mothering other than normal children. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12:515–530. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson MB, Hwang CP. Sense of coherence in parents of children with different developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research. 2002;46:548–559. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2002.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham KI, Samios C, Sofronoff K. Adjustment in mothers of children with Asperger syndrome: an application of the double ABCX model of family adjustment. Autism. 2005;9(2):191–212. doi: 10.1177/1362361305049033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM. Families experiencing stress: I. The Family Adjustment and Adaptation Response Model: II. Applying the FAAR Model to health-related issues for intervention and research. Family Systems Medicine. 1988;6(2):202–237. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM. Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:349–360. [Google Scholar]

- Risdal D, Singer GHS. Mental adjustment in parents of children with disabilities: a historical review and meta-analysis. Research and Practice for People with Severe Disabilities: Special Family and Disability. 2004;29:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland JS. Beliefs and collaboration in illness: evolution over time. Family Systems Health. 1998;17:7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience, competence and coping. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe A, Joosten A, Molineux M. The experiences of mothers of children with autism: managing multiple roles. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 2012;37(4):294–302. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2012.736614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JL, Morgan JB. Family stress and adjustment as perceived by caregivers of children with autism or Down syndrome: implication for intervention. Child and Family Behavior Therapy. 1997;19:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Scorgie K, Sobsey D. Transformational outcomes associated with parenting children who have disabilities. Mental Retardation. 2000;38:195–206. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2000)038<0195:TOAWPC>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley CE, Bitsika V, Efremidis V. Influence of gender, parental stress and perceived expertise of assistance upon stress, anxiety and depression among parents of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 1997;22:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow S, Cicchetti D, Balla D. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. 2nd ed AGS Publishing; Pine Circles, MN: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stainton T, Besser H. The positive impact of children with an intellectual disability on the family. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 1998;23:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Gelfand DM. Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: the mediational role of maternal self-efficacy. Child Development. 1991;62:918–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress, coping, and social support processes: where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:53–79. (extra issue) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. Strengthening Family Resilience. Guilford; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL, Ateah C, Secco L. Living in a world of our own: the experience of parents who have a child with autism. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:1075–1083. doi: 10.1177/1049732308320112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]