Abstract

Objective

To evaluate safety and explore efficacy of recombinant human lactoferrin (talactoferrin, TLf) to reduce infection.

Study design

We conducted a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial in 6 0 infants with birth weights of 750 to 1500 grams. Each infant received enteral TLf or placebo on day 1 through 28 days of life; TLf dose was 150 mg/kg/12 hour. Primary outcomes were bacteremia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, meningitis and necrotizing enterocolitis. Secondary outcomes were sepsis syndrome and suspected NEC. We recorded clinical, laboratory and radiologic findings, diseases, and adverse events in a database used for statistical analyses.

Results

Infants in the two groups had similar demographics. We attributed no enteral or organ-specific adverse events to TLf. There were two deaths in the group with TLf (posterior fossa hemorrhage and post-discharge sudden infant death), and one infant given placebo died of necrotizing enterocolitis. Hospital-acquired infections in the group with Tlf were 50% of that observed in infants fed placebo (p<0.04), including fewer blood or line infections, urinary tract infections, and pneumonia. Fourteen infants treated with TLf-weighing <1 kg at birth weight had no Gram-negative infections versus three of 14 infants given placebo. Non-infectious outcomes did not differ statistically in the two arms. No differences in growth or neurodevelopment occurred among infants treated with TLf and placebo during a one-year, post-hospitalization period.

Conclusion

We found no clinical or laboratory toxicity and a trend towards less infectious morbidity in infants treated with TLf.

Trial registration

Keywords: lactoferrin, safety, hospital-acquired infections, VLBW infants

Hospital-acquired infections represent the majority of diseases affecting preterm infants in NICUs.1 Because hospital-acquired infections increase the hospital stay and escalate significantly the cost of care, the American Academy of Pediatrics called for strategies to reduce hospital-acquired infections in NICUs.2,3 Among hospital-acquired infections, bacteria resistant to broad-spectrum antibiotics cause >50% of patient-associated disease,4 which has led to an emphasis on antibiotic stewardship.

Modified health care practices have reduced hospital-acquired infections in extremely preterm infants,2,3 but do not address the underlying immaturity of the mucosal and systemic immune systems.5 Maternal milk is known to reduce the occurrence of bacteremia and necrotizing enterocolitis.6,7 Biomolecules in human milk are proposed to synchronously modify the intestinal microbiome and nascent gut and systemic immunity, thereby reducing susceptibility to infection.5,8 Extremely preterm infants (<1 kg birth weight) have the highest vulnerability to infection because maternal colostrum is either limited immediately after birth or intestinal dysmotility hinders full enteral feedings for days to weeks.

Human milk proteins enhance development of intestinal epithelia, facilitate a healthy intestinal microflora, establish host defenses, and heighten mucosal defenses. We propose that the human milk protein lactoferrin partly explains these beneficial effects.9,10 Commercial recombinant human lactoferrin became available 20 years ago.11 We found feeding TLf prophylactically to neonatal rats prevented morbidity and mortality caused by enteroinvasive Escherichia coli.12 Our research then became focused on enteral lactoferrin deficiency that occurs in the early life of immature infants. We hypothesized that feeding TLf would be safe, and conducted a randomized controlled trial to assess its safety and efficacy in VLBW infants.

METHODS

This double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial fed TLf or placebo to infants with birth weights between 750 and 1500 grams within 24 hours of birth and through 28 days of life (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00854633). We excluded infants if they had a major congenital malformation, chromosomal abnormality, documented prenatal or intrapartum neonatal infection, absence of parental consent, or were moribund at birth. We enrolled and randomized subjects from the period of July 1, 2009, to March 17, 2012. After hospital discharge, a one-year outpatient follow-up period took place. Agennix Inc (Houston, TeXas), the trial sponsor, ended the final data analyses in December 2013.

Agennix provided TLf to three academic health care systems in the United States. Agennix used good manufacturing practice and suspended TLf in sterile, endotoxin-free, phosphate-buffered saline. The excipient served as the placebo with excellent color matching. The institutional human review board for each site approved the study. We obtained written consent from the parents or legal guardians before 24 hours of age. Thereafter, each institutional pharmacy randomized a subject via a central computer system (inVentiv Clinical Solutions, Houston, TX). The inVentiv Web Response system also recorded data about participants in this RCT. Agennix sponsored the research under a FDA investigational new drug policies and procedures. Study design included a data safety monitoring committee, a centralized serious adverse event reporting system, and periodic on-site monitoring visits that verified clinical, health care, laboratory, radiologic information, and pharmacy record keeping.

We randomized infants so they received either TLf solution (150 mg/ml) at a dose of 300 mg/kg/day or an identical volume of the excipient. We gave doses every 12 hours via nasogastric tube from day 1 through the 28th day of life or until discharge, whichever occurred first. We extrapolated the dose of TLf from lactoferrin consumed during enteral breast milk feeding (150 ml/kg/d) with the content of lactoferrin in human milk estimated at 2 mg/ml. In all subjects, we administered the first dose before 24 hours of age. We adjusted the dose at weekly intervals if the weight increased from a prior weight by ≥10 percent.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was a significant reduction in hospital-acquired infections, including bacteremia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, meningitis and NEC. Our criteria were based on CDC-related definitions for hospital-acquired infection.13 The sponsor established strict criteria for infection, including blood stream infections, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, meningitis and necrotizing enterocolitis.14 A diagnosed infection required antibiotics for ≥72 hours.

Secondary outcomes were mortality, duration of hospitalization, time to regain birth weight, and the time to reach full enteral feeds. Disease-related morbidities included a medically- or surgically-treated patent ductus arteriosus, intracerebral hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, retinopathy of prematurity, chronic lung disease defined as O2 therapy at 36 weeks of post-conceptual age, suspected NEC, clinical sepsis syndrome and neonatal inflammatory response syndrome. We defined a clinical sepsis syndrome as a negative blood culture, but clinical and laboratory findings necessitating empiric antibiotic therapy. These criteria included elevated inflammatory markers, namely serial C-reactive protein levels (≥1.5 mg/dL), abnormal serial white blood cell counts, or an elevated immature/total neutrophil ratio (≥0.3), central thermal instability, apnea and bradycardia, or respiratory distress. We established suspected NEC as a clinical scenario that involved a cessation of enteral feedings and initiation of antibiotics based on gastric residuals, occult or gross blood in the stool, abdominal distention, radiographs showing dilated loops of bowel and an abnormal bowel gas pattern, but without a sentinel loop nor pneumatosis intestinalis.

Safety Assessment

We used the MedDRA system to report safety outcomes to the FDA.15 Investigators underwent training to use this grading and severity scoring system. This system reports adverse or severe adverse events occurring daily using an acceptable FDA measurement scale.15 The FDA mandated daily recording of clinical information during the 28-day prophylactic period, and infants were then evaluated at weekly intervals until discharge. At 6- and 12-month post-discharge visits, we collected growth measurements including head circumference, health outcomes and developmental progress using the Bayley screener. If the participant did not return, investigators contacted the primary care physician, parents by telephones call, or parents by US mail to ascertain clinical status.

Agennix did not require any specific collection of clinical findings, laboratory tests, or radiologic studies. The FDA IND required information on daily weight and abdominal circumference, vital signs, physical examination findings, type and duration of respiratory support, O2 saturation, volume and type of enteral feeding, intravenous fluids and total parenteral nutrition volume and composition, urinary output, gastric residual volumes, number and description of feces passed, concomitant medications. The study protocol collected laboratory and radiographic tests as ordered by the supervising neonatal attending. Tests included complete blood counts, C-reactive protein, complete metabolic and electrolyte panels, blood gas reports, gross or occult blood in feces, and results of all radiographic studies. We used the cumulative weight gain from birth and the duration of hospitalization as biomarkers of nutritional support.

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

This RCT focused on safety. We based the original sample size for the Phase 1 study on the recommendations of Cohen (similar to G* Power 3.1) for an ANOVA with four groups. Using a power of .80, an effect size of .5, and an alpha of 0.05, a minimum of 48 total subjects was necessary to complete the safety phase of the study. We based the Phase 2 sample size calculations on the same statistical parameters, but with a reduction in the effect size to .175 resulting in a minimum total sample of 360 subjects. Allowing for 10% attrition, we estimated 396 subjects were necessary. Because of reduced funding, we lowered our sample size from 396 to 120 VLBW infants in two groups, TLf (n = 60) and placebo (n = 60). Thus, the investigation was underpowered to identify significant primary or secondary outcomes.

Investigators recorded clinical, laboratory and radiologic findings, disease states, and adverse events into the inVentiv SAS database. We performed statistical analysis using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics included frequencies, percentages, and measures of central tendency. We analyzed ratio level data such as blood count values, C-reactive protein, and the volume of gastric residuals with the independent-samples t test; however, if the data was not normally distributed, we used the Mann-Whitney U test. Nominal data was analyzed with the Chi-square test of Independence or the Fisher exact test if cells had values less than five. To measure cumulative weight gain at discharge, we utilized a mixed effects regression model that accounted for treatment, feeding strata, birth weight, and days since birth as explanatory variables. Clinical significance was determined using risk indices, namely relative risk (RR), 95% confidence interval, and numbers needed to treat (NNT). The safety monitoring board used these measures to ascertain TLf-related adverse events and to determine primary and secondary outcomes.

RESULTS

Table I shows demographics of the preterm infants and mothers associated with the clinical trial. Mothers declared their decision regarding breast milk or formula feeding during the consent process. The pharmacy used a mother’s feeding decision during randomization. Hence, assignments were equal to TLf or versus placebo and enteral nutrition with mother’s milk and formula. Human donor milk was not used. during the trial.

TABLE 1.

Maternal and Infant Demographics

| Characteristics | TLf (n = 60) | Placebo (n = 60) |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational Age (week ± Standard Deviation)1 | 28 ± 6/7 | 28 ± 6/7 |

| Birth weight (grams ± Standard Deviation)1 | 1152 ± 206 | 1143 ± 220 |

| 750 to 1000 g: number (%)2 | 14 (23) | 14 (23) |

| 1001 to 1500 g: number (%)2 | 46 (75) | 46 (75) |

| Small for Gestational Age2 | 9 (15) | 11 (18) |

| Male (%)2 | 33 (55) | 36 (60) |

| Median Apgar Score @ 1 and 5 min3 | 5 and 8 | 7 and 8 |

| # Multiple Births (%)2 | 18 (30) | 13 (22) |

| Preterm Labor2 | 42 (70) | 41 (68) |

| Premature Rupture of Membranes2 | 19 (32) | 21 (35) |

| >12 hour Rupture of Membranes2 | 8 (13) | 15(25) |

| Maternal Antibiotics2 | 32 (53) | 35 (58) |

| One or More Doses of Betamethasone2 | 48 (80) | 45 (75) |

| Cesarean/Vaginal Delivery2 | 49/11 | 48/12 |

| RACE/ETHNICITY | TLf | Placebo |

| White2 | 36 | 33 |

| African American2 | 5 | 11 |

| Asian2 | 1 | 0 |

| Multi-racial and/or ethnicity2 | 5 | 4 |

| Ethnicity - Hispanic2 | 13 | 12 |

All comparisons had p values ≥0.25.

Statistical analyses:

independent t test;

Chi-square test;

Mann-Whitney U test

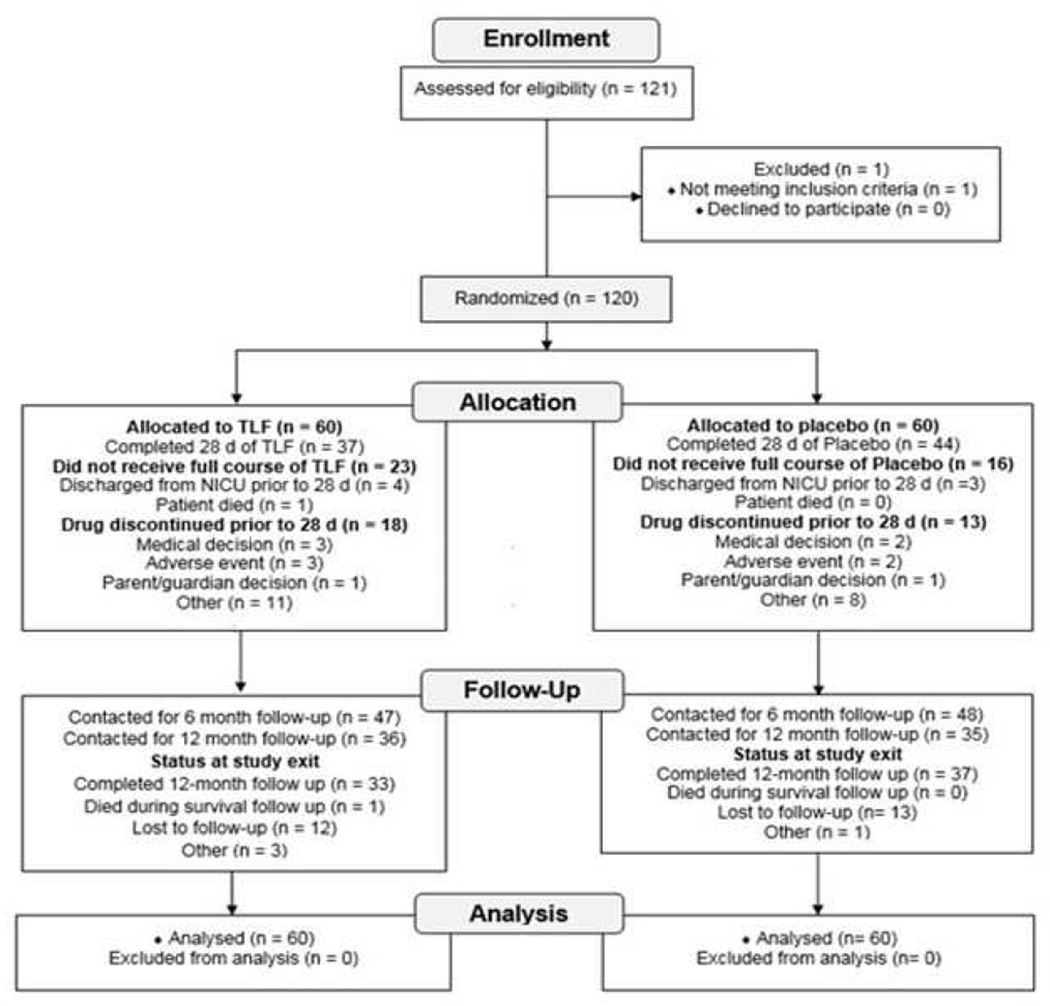

We present a CONSORT diagram as the Figure (available at www.jpeds.com). Thirty-seven infants (62%) completed the entire 28-day TLf-treatment period and 44 infants (73%) completed the entire placebo arm. One infant assigned to the TLf arm died of brain stem hemorrhage at 30 hours of age and we excluded this infant from outcome assessment. One infant in the TLf arm died of sudden infant death syndrome after discharge. One infant in the placebo arm died of necrotizing enterocolitis with sepsis. Among 23 infants in the TLf arm who did not complete an entire course, the reasons for discontinuing therapy included: (1) discharge before the 28th day (n=4); (2) death; (3) medical or surgical therapy for a hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus, suspected NEC, or enteral feeding problems (n=18). In the placebo arm of the study, thirteen infants ended the placebo dosing before the 28th study day; reasons for cessation of the placebo were a) discharge home before the 28th day (n=13), b) withdrawal of consent (n=1), and c) an attending neonatologist stopped the placebo in four infants.

Figure 1.

Trial Profile

The number of doses received, duration of drug exposure, and total drug intake (mg) were not statistically different between the two arms. Drug compliance was 94.6% in the group with Tlf and 96% in the placebo group.

At the 6-month follow-up visit, we ascertained the health and developmental status in 88 and 80% of subjects treated with TLf and placebo, respectively. At the 12-month follow-up visit, we evaluated 55% and 52% percent of infants given TLf or placebo, respectively. Telephone calls indicated that missed appointments were due to good health and development in the infant, time away from work, or travel-related distance.

Safety Outcomes

Table II shows the incidence and type of adverse events occurring in the study population. The overall rate of at least one treatment emergent AE was similar between the two study arms. We identified adverse events related most often to preterm birth rather than TLf or the placebo. Gastrointestinal (76%), blood and lymphatic (60%), nutrition and metabolism (72%) and respiratory disorders (72%) were the most commonly reported treatment emergent AE. These events were often the reason for study drug or placebo discontinuation. Rates of at least one SAE were also similar between treatment and placebo arms. All SAE were associated with complications of very preterm birth rather than administration of TLf or placebo. The Data Safety Monitoring Board never halted the progression of the RCT.

Table 2.

SUMMARY OF ADVERSE EVENTS

| Study Adverse Events | Total - n (%) | TLf - n (%) | Placebo - (n) (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At Least One AE | 118 (98.3) | 58 (97) | 60 (100) | 0.99 |

| At Least One AE of grade 3/4/5 |

52 (43) | 27 (45) | 25 (42) | 0.91 |

| At Least One SAE | 15 (13) | 7 (12) | 8 (13) | 0.95 |

| At Least One TLf or placebo Adverse Event |

0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| At Least One AE Causing Drug Discontinuation |

22 (18) | 14 (23) | 8 (13) | 0.33 |

| AEs Related to Study Drug | Total | TLf | Placebo | – |

| Not Related | 106 (88) | 53 (88) | 53 (88) | 0.94 |

| Possibly related | 12 (10) | 5 (8) | 7 (12) | 0.83 |

| AE by Degree of Severity | Total | TLf | Placebo | – |

| Grade 1 | 29 (24) | 14 (23) | 15 (25) | 0.94 |

| Grade 2 | 37 (31) | 17 (28) | 20 (33) | 0.84 |

| Grade 3 | 46 (38) | 25 (42) | 21 (35) | 0.83 |

| Grade 4 | 4 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 0.65 |

| Grade 5 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0.48 |

| Deaths | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Treatment Related Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

Definitions: MedDRA Version 14.1 defined Class, Organ system & Preferred Terms. Scoring criteria please view: http://www.meddra.org/

Abbreviations: TLf – talactoferrin; AE – adverse event; SAE – severe adverse event.

Primary Outcomes

Table III summarizes the primary outcome. Infants who received TLf had a reduced risk for hospital-acquired infections during the NICU stay (RR 0.52 [95% CI 0.26–0.99], p<0.045). There were no cases of meningitis. Two infants treated with TLf developed NEC and both survived, and one formula-fed infant given placebo died from NEC.

Table 3.

First Episode Hospital Acquired Infections in Study Groups1

| Number (%)2 | Statistics: TLF vs Placebo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Type | TLf (n = 59) |

Placebo (n = 60) |

RR (% CI) | NNT | p value3 |

| Hospital-acquired infection1 | 10 (17%) | 20 (33%) | .52 .26 – .99 |

6 | P<0.04 |

| Blood/Line Infection CoNS – two positive cultures required (1) |

6 (10%) | 10 (17%) | .64 (0.3,1.7) |

14 | 0.52 |

| Urinary Tract Infection Aseptic Catheter or Suprapubic Tap Isolated Pathogen >104 CFU/mL in urine |

0 (0%) | 5 (8%) | .10 (0.01,1.8) |

13 | 0.09 |

| Trachea Aspirate Pathogen-related Pneumonia + CDC criteria (14) |

2 (3%) | 4 (7%) | .52 (0.1,2.8) |

25 | 0.72 |

| Intestine Necrotizing Enterocolitis Bell stage II or higher (15) |

2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | .23 (0.1,1.0) |

61 | 1.0 |

| Infections per Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Stay | |||||

| Total Hospital Days | 3460 | 3446 | N.S. | ||

| Hospital-acquired infection/1000 hospital days |

2.0 | 4.4 | .52 (0.1, 2.8) |

25 | 0.10 |

First identified episode of hospital-acquired infection in blood stream, spinal fluid, urine, and lung fluid.

n/N (%) denotes the # of hospital-acquired infection/total number of infants per group.

p value used Chi-square test for infectious comparisons; hospital-acquired infection/1000 hospital days from t test;

Table IV shows the types of bacteria causing infections. In the TLf group, there was a reduction in Gram-positive bacterial isolates with coagulase-negative staphylococci accounting for most of these isolates. In 14 infants <1 kg birth weight, we identified no cases of Gram-negative bacterial infection and two cases of CoNS-related bacteremia (14%). In the placebo group, five of 14 (36%) of infants with a birth weight <1 kg had bacteremia caused by CoNS (n=2) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=1); two infants had pneumonia caused by Klebsiella oxytoca.

Table 4.

Bacteria Identified with First hospital-acquired infection1

| Bacteria (n)/Total hospital- acquired infection2 |

TLF vs Placebo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | TLf 8 (14%) n = 59 |

Placebo 20 (33%) n = 60 |

RR (CI) |

NNT | P value3 |

| Bacterial Isolate1 | |||||

| Gram-negative Bacteria |

4 (50%) | 5 (25%) | 1.6 (0.5,4.8) |

8 | 0.96 |

| Gram-positive bacteria |

4 (50%) | 15 (75%) | .76 (0.3,1.8) |

3 | 0.04 |

| # of CoNS per Gram-positive infection4 |

3 of 4 (75%) | 11 of 15 (73%) | .74 (0.3,2.2) |

5 | 0.09 |

All n are based on the type of bacteria identified by Gram stain result and culture identification methods for 1st episode of hospital-acquired infection

n/N denotes the number of each type of infection/total number of study subjects by type (%)

p value from Chi square test, significance p ≤ 0.05

n/N is the number of CoNS infections per total gram positive bacterial infections

Abbreviations: CoNS - coagulase-negative staphylococcus; RR – relative risk; NNT – number needed to treat

Secondary and Other Efficacy Outcomes

Secondary outcomes including cumulative weight gain from birth and duration of hospitalization did not differ between study arms or feeding type. Follow-up records in the SAS database after hospital discharge identified no abnormalities in growth or development between infants treated with TLf and placebo. We proposed TLf might reduce inflammation in treated infants.9 The peak C-reactive protein level was not different between infants fed TLf (n = 30) vs placebo (n = 38) (1.6 ± 1.6 mg/dL vs 2.8 ± 6.0 mg/, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Four investigative groups have published clinical trial information using enteral administration of bovine lactoferrin to prevent late-onset sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis during hospitalization of infants with birth weights ≤2000 grams.16–19 The current RCT is a Phase 1/2 trial that provides safety and preliminary efficacy data associated with enteral administration of TLf. The study used a recombinant human lactoferrin produced under ‘good manufacturing practices’ and with Food and Drug Administration approval as an Investigational New Drug. This study also used the MedDRA system to measure safety during and after administration of TLf, an instrument used by the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use.12 The results demonstrate the safety of the TLf molecule and provide an initial report of efficacy related to reducing hospital-acquired infections and possibly other non-infectious related outcomes.

Among the four previous studies using bovine lactoferrin in preterm infants, each observed a reduced rate of infection of a variable magnitude, and one report using prophylaxis with bovine lactoferrin noted a reduction in late onset sepsis among infants <1 kg birth weight.16 In the current TLf trial, we found a 14% rate of infection in <1 kg birth weight infants given enteral TLf versus 36% in babies fed placebo. Our report is in agreement with Manzoni et al,16 with comparable reductions in infection in extremely preterm infants. In all studies using bovine lactoferrin, the biologic agent was “generally regarded as safe” as a food supplement. In contrast, the source of taloctoferrin was biotechnology rather than a food supplement isolated from bovine milk. Furthermore, compared to the aforementioned RCT using bovine lactoferrin,16 TLf had therapeutic efficacy in reducing Gram-positive bacterial infections similar to bLf (Table IV). We propose this decline caused the overall reduction in hospital-acquired infections in infants treated with TLf vs. placebo (Table III).

Infants fed TLf had no urinary tract infections compared to placebo, but this was not statistically significant. Recently, an association between urinary infections and NEC was reported.20 Because the fecal microbiome is a microbial reservoir for urogenital colonization, we suggest a possible relationship between enteric prophylaxis with TLf and reduced urinary infections, and would encourage examination of this association in upcoming clinical trials of bovine lactoferrin. Future studies of lactoferrin prophylaxis should study the fecal microbiome because the microbiota present may be transferred other body sites. Metagenomic technology can accurately classify the fecal translocation of pathogenic bacteria originating in the feces.21

Finally, studies in progress should evaluate the safety of lactoferrin by using an internationally accepted method like MedDRA. Based on the suggested mechanisms of action for lactoferrin,9,18 we suggest that future RCTs also report on differences in inflammatory biomarkers between lactoferrin- and placebo-control subjects. One attractive strategy might be examining inflammation in twins that are randomized to enteral lactoferrin vs. placebo. Thoughtful adaptations of the traditional RCT design may provide opportunities to test whether lactoferrin supplementation will reduce infectious and other morbidities in VLBW infants.

Table.

Study Drug Exposure and Compliance

| TLf & Placebo Dosing | TLf (n = 60) | Placebo (n = 60) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Doses Received | 46 ± 14 | 49 ± 10 |

| Duration Drug Exposure (d) | 25 ± 7 | 26 ± 5 |

| Total Drug Intake (mg) | 5461 ± 4739 | 6221.50 ± 4999 |

| Percent Compliance | 94.9 | 96.0 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation

Duration of drug exposure = (date of last dose - date of first dose) +1

Total drug exposure = sum (dose (mg/kg) × daily weight (kg))

% compliance = 100 × (# Complete or Partial Doses) ÷ (# Doses Taken + # Missed Doses)

Table.

Patient Demographics for First episode hospital-acquired infection

| Assessment | mean ± standard deviation | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finding | TLf n = 59 |

Control n = 60 |

p value |

| Time of Onset (days of life)1 | 19 ± 4 | 16 ± 2 | 0.40 |

| Gestational Age (weeks)1 | 27 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 0.80 |

| Birth weight (grams)1 | 994 ± 61 | 1003 ± 58 | 0.92 |

| Infections <1000 grams2 | 2 of 14 (14%) | 8 of 14 (57%) | 0.14 |

| Infections >1001 grams3 | 5 of 45 (11%) | 6 of 46 (13%) | 0.96 |

t test,

Fisher Exact test,

Chi-square test for independence

Abbreviations: TLf – talactoferrin

Table.

SECONDARY OUTCOMES IN BREAST-FED INFANTS

| Breast-fed | Talactoferrin1 (n = 45) |

Placebo1 (n = 46) |

Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary efficacy endpoints/outcomes |

N | n (%) | N | n (%) | p value2 |

| Suspected NEC | 45 | 6/46 (11) | 46 | 8/46 (15) | 0.89 |

| Neonatal Sepsis Syndrome or Inflammatory Response Syndrome |

45 | 3/46 (8) | 46 | 1/46 (2) | 0.61 |

| Death | 45 | 3/60 (3) | 46 | 0/60 (2) | 0.26 |

| Other outcomes | 45 | 11/46 (24) | 46 | 11/46 (22) | 0.89 |

| Growth & Care Characteristics |

N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | p value3 |

| Days to regain birth weight3 |

44 | 4 ± 4 | 46 | 5 ± 5 | 0.26 |

| Days to full enteral feeds3 |

37 | 23 ± 13 | 46 | 20 ± 15 | 0.24 |

| Days of assisted ventilation therapy3 |

36 | 10 ± 9 | 30 | 9 ± 9 | 0.76 |

| Days of oxygen therapy3 |

37 | 13 ± 14 | 35 | 19 ±19 | 0.32 |

| Duration (days) of hospital stay3 |

45 | 60 ± 31 | 46 | 59 ± 29 | 0.83 |

| Cumulative Weight Gain at Discharge |

45 | 1702 ± 20 g | 46 | 1663 ± 20 g | 0.15 |

n denotes the # of events/total number of infants in a feeding group.

p values based Chi-square or Fisher Exact Test (no calculation if a row of cells has all

p value based on Mann Whitney U test.

Table.

Secondary Outcomes in Formula-fed Infants

| Formula-fed | Talactoferrin1 (n = 15) |

Placebo1 (n = 14) |

Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary efficacy endpoints/outcomes |

N | n (%) | N | n (%) | p value2 |

| NEC Scares | 15 | 1 (8) | 14 | 1 (7) | 1.0 |

| Neonatal Sepsis Syndrome or Inflammatory response syndrome |

15 | 0 (0) | 14 | 0 (0) | –– |

| Death | 15 | 0 (0) | 14 | 0 (0) | –– |

| Other endpoints/outcomes | 15 | 1 (8) | 14 | 2 (14) | 1.0 |

| Growth & Care Characteristics |

N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | p value3 |

| Days to regain birth weight3 | 15 | 4 ± 5 | 14 | 2 ± 5 | 0.50 |

| Days to full enteral feeds3 | 13 | 16 ± 8 | 10 | 22 ± 15 | 0.58 |

| Days of assisted ventilation therapy3 |

8 | 6 ± 9 | 10 | 11 ± 11 | 0.18 |

| Days of oxygen therapy3 | 13 | 16 ± 10 | 9 | 29 ± 33 | 0.48 |

| Duration of hospital stay3 | 15 | 51 ± 22 | 14 | 58 ± 29 | 0.82 |

| Cumulative Weight Gain at Discharge |

13 | 1713 ± 31 g | 9 | 1710 ± 30 g | 0.94 |

n denotes the # of events/total number of infants in a feeding group.

p values based Chi-square or Fisher Exact Test (no calculation if a row of cells has all

p value based on Mann Whitney U test.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the care provided by our fellow neonatologists, neonatal-perinatal medicine fellows, neonatal intensive care nurses, respiratory care practitioners, and pharmacists during this RCT.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health (HD057744 to Agennix, Inc [PI: K.P. and M.S.]). K.P. served as project coordinator and Vice-President for Research at Agennix, Inc until 2012.

Abbreviations

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration of the United States Government

- NEC

necrotizing enterocolitis

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- NNT

number needed to treat

- RCT

randomized controlled clinical trial

- RR

Relative Risk

- TLf

talactoferrin (the drug designation for recombinant human lactoferrin)

- AE

adverse event

- SAE

serious adverse event

- VLBW

very low birth weight (≤1.5 kg birth weight)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of the study were presented at a Mead Johnson Pediatric Nutrition Institute, Boston, MA, <month and days>

REFERENCES

- 1.Polin RA, Denson S, Brady MT Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Committee on Infectious Diseases. Epidemiology and diagnosis of health care-associated infections in the NICU. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1104–e1109. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bizzarro MJ, Shabanova V, Baltimore RS, Dembry LM, Ehrenkranz RA, Gallagher PG. Neonatal sepsis 2004 – 2013: the rise and fall of coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Pediatr. 2015;166:1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polin RA, Denson S, Brady MT Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Committee on Infectious Diseases. Strategies for prevention of health care-associated infections in the NICU. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1085–e1093. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantey JB, Milstone AM. Bloodstream infections: epidemiology and resistance. Clin Perinatol. 2015;42:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collado MC, Cernada M, Neu J, Pérez-Martínez G, Gormaz M, Vento M. Factors influencing gastrointestinal tract and microbiota immune interaction in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2015;77:726–731. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel AL, Johnson TJ, Engstrom JL, Fogg LF, Jegier BJ, Bigger HR, et al. Impact of early human milk on sepsis and health-care costs in very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol. 2013;33:514–519. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan S, Schanler RJ, Kim JH, Patel AL, Trawöger R, Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, et al. An exclusively human milk-based diet is associated with a lower rate of necrotizing enterocolitis than a diet of human milk and bovine milk-based products. J Pediatr. 2010;156:562.e1–567.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neu J, Mihatsch WA, Zegarra J, Supapannachart S, Ding ZY, Murguía-Peniche T. Intestinal mucosal defense system, Part 1. Consensus recommendations for immunonutrients. J Pediatr. 2013;162:S56–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherman MP, Adamkin DH, Radmacher PG, Sherman J, Niklas V. Protective 16 Proteins in Mammalian Milks: Lactoferrin Steps Forward. NeoReviews. 2012;13:e293–e300. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang R, Du X, Lönnerdal B. Comparison of bioactivities of talactoferrin and lactoferrins from human and bovine milk. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:642–652. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward PP, Piddington CS, Cunningham GA, Zhou X, Wyatt RD, Conneely OM. A system for production of commercial quantities of human lactoferrin: a broad spectrum natural antibiotic. Biotechnology (NY) 1995;13:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nbt0595-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edde L, Hipolito RB, Hwang FF, Headon DR, Shalwitz RA, Sherman MP. Lactoferrin protects neonatal rats from gut-related systemic infection. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1140–G1150. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKibben L, Horan TC, Tokars JI, Fowler G, Cardo DM, Pearson ML, et al. Guidance on public reporting of healthcare-associated infections: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:580–587. doi: 10.1086/502585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1986;33:179–201. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3955(16)34975-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MedDRA Use at FDA. http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/Training/GCG_-_Endorsed_Training_Events/ASEAN_MedDRA_March_2010/Day_3/Regulatory_Perspective_SBrajovic.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manzoni P, Rinaldi M, Cattani S, Pugni L, Romeo MG, Messner H, et al. Bovine lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of late-onset sepsis in very low-birth-weight neonates: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302:1421–1428. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manzoni P, Meyer M, Stolfi I, Rinaldi M, Cattani S, Pugni L, et al. Bovine lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight neonates: a randomized clinical trial. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90:S60–S65. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3782(14)70020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akin IM, Atasay B, Dogu F, Okulu E, Arsan S, Karatas HD, et al. Oral lactoferrin to prevent nosocomial sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis of premature neonates and effect on T-regulatory cells. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:1111–1120. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1371704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochoa TJ, Zegarra J, Cam L, Llanos R, Pezo A, Cruz K, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Lactoferrin for Prevention of Sepsis in Peruvian Neonates Less than 2500 g. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:571–576. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pineda LC, Hornik CP, Seed PC, Cotten CM, Laughon MM, Bidegain M, et al. Association between positive urine cultures and necrotizing enterocolitis in a large cohort of hospitalized infants. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91:583–586. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherman MP, Minnerly J, Curtiss W, Rangwala S, Kelley ST. Research on neonatal microbiomes: what neonatologists need to know? Neonatology. 2014;105:14–24. doi: 10.1159/000354944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]