Abstract

Non-motor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease (PD) can begin well before motor PD begins. It is now clear, from clinical and autopsy studies, that there is significant Lewy type alpha-synucleinopathy present outside the nigro-striatal pathway, and that this may underlie these non-motor manifestations. This review will discuss neuropathological findings that may underlie non-motor symptoms that either predate motor findings or occur as the disease progresses.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, synuclein, non-motor signs

Non-motor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease (PD) can begin well before motor PD begins. The concept of a prodromal stage of PD has been discussed in many reviews,1, 2 and it is the non-motor signs that have led to this concept. It is important to gain a better understanding of these non-motor signs and symptoms as they have a significant impact on quality of life and they may be critical to defining an at-risk population for future PD prevention trials.

It is now clear, from clinical and autopsy studies, that Lewy type α-synucleinopathy (LTS) is never restricted to the nigrostriatal pathway, and that non-motor manifestations of PD likely arise from a diverse neuroanatomical distribution of LTS. This review will begin with the neuropathological findings that may underlie the non-motor manifestations of prodromal PD then discuss those that are seen in individuals with motor PD. It should be noted that as neuropathological methods differ greatly between laboratories (including tissue preparation, antibodies used, staining techniques, etc.) comparing studies can be difficult.3

Prodromal Parkinson’s Disease

Incidental Lewy body disease

There are a number of disorders that are neuropathologically found to be α-synucleinopathies. These include PD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), multiple system atrophy (MSA), and primary autonomic failure (PAF). Additionally, it is clear from autopsy studies that 10–30% of autopsied elderly with no clinical signs of motor parkinsonism or dementia have LTS in the brain, and this has been called incidental Lewy body disease (ILBD).4–6 Subjects with ILBD may have been in the prodromal stage of a clinically manifest α-synucleinopathy, and thus, had they lived longer, may have gone on to develop PD, MSA, or DLB. Evidence to suggest that ILBD is prodromal PD includes the finding of an approximately 50% decrease in striatal dopaminergic markers as well as significantly decreased numbers of substantia nigra pigmented neurons.7–10 A reduction in epicardial tyrosine hydroxylase activity has also been found.11 Autopsy studies of ILBD therefore offer a critical opportunity to map the whole-body distribution of clinically prodromal LTS and relate this to non-motor prodromal signs and symptoms. Additionally, longitudinal clinicopathological studies of ILBD that incorporate premortem biomarker studies of normal elderly control populations with eventual neuropathological diagnosis may identify markers valuable in identifying prodromal PD.

Autopsy studies have documented the distribution of LTS in both the CNS and PNS of elderly subjects.4, 6, 12–15 Our original CNS-wide survey of 417 autopsy cases,4 as well as our (unpublished) accumulated data since then (766 brain-only autopsies and 466 whole-body autopsies with brain) from the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders (AZSAND) indicate that the olfactory bulb is most likely to be the first-affected brain or body region, with 52 cases for which it was the sole affected site. In comparison, the amgydala (2 cases), locus ceruleus (10 cases) and dorsal medulla (5 cases) are much less frequently the sole site. There were no cases with substantia nigra as the sole affected site. We do not have a single case in which LTS was present in a peripheral (body) region but not in the CNS, arguing against Braak’s hypothesis that LTS begins in the GI tract. Of 55 autopsied subjects with ILBD, 20% were classified as Stage I (Olfactory Bulb Only), 42% were Stage IIa (Brainstem Predominant), 14% were stage IIB (Limbic Predominant), 22% were Stage III (Brainstem and Limbic) and 2% (1 case) was Stage IV (Neocortical), according to the Unified Staging System for Lewy Body Disorders.4 In our original study mapping the peripheral distribution of LTS in ILBD,12 we found the sympathetic ganglia affected in 50% of cases, the vagus nerve (not the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus which is in the brainstem) in 33% of cases and the gastrointestinal tract in 14% and these percentages have not significantly changed with subsequent autopsies (unpublished data). Notably, however, one other respected group has found, in a small percentage of cases, LTS affecting solely the paraspinal peripheral sympathetic ganglia.13

By definition, autopsied subjects with ILBD should not have had PD or dementia while alive. One study has shown that there were no clear motor or cognitive differences between ILBD and control subjects.16 However, the neuropathological and neurochemical findings may have other clinical correlates. The presence of LTS in the olfactory bulb appears to underlie the hyposmia/anosmia seen in PD and also in ILBD.4 This concurrence of clinical and pathological findings has been shown in multiple studies of ILBD17, 18 and PD.15, 19, 20

Some non-motor findings in ILBD and PD may be due to peripheral LTS, but at present there are still insufficient numbers of subjects with whole-body autopsies to clearly distinguish the relative contributions of CNS and peripheral LTS. The evidence to date for a peripheral contribution, however, will be reviewed here.

A common non-motor finding in both PD and ILBD is constipation. In a study of 245 autopsied men, those with less than one bowel movement per day were 4.3 times more likely to have ILBD, as compared to those with greater than one bowel movement per day.21 In a study of LTS in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of ILBD subjects, only 1/4 had LTS staining in the colon, and there was no loss of enteric neuronal cell bodies.22 Additionally, LTS is often present in the spinal cord in ILBD and it is possible that this also underlies the constipation seen in ILBD.12, 13, 23–25

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a sleep disorder characterized by lack of atonia during REM sleep. Multiple studies have shown that RBD is more common in PD than controls with up to 65% of PD patients having RBD.26–29 Additionally, idiopathic RBD appears to be a strong risk factor for the development of PD or DLB. Of great interest has been the finding of many non-motor features of PD in the RBD population. Hyposmia is present in RBD and those with both RBD and hyposmia appear to progress to PD or DLB at a faster rate.28, 30–32 A second non-motor finding in PD that is also found in RBD is an abnormality in color vision.28, 30 This may well be due to the presence of synucleinopathy in the retina.33, 34

The neuropathology underlying RBD is consistent with it being a synucleinopathy. In the few autopsy studies of idiopathic RBD published to date, the presence of LTS suggests a pathologic role. In a multi-center study of the neuropathology underlying RBD, a recent study showed that 93% of 172 autopsied cases that had RBD had either pathologically defined PD or DLB (79%), or MSA (11%).35 Of those without synucleinopathy six had AD and two had PSP.35 Most recently it was reported that of 81 autopsied PD subjects 40 had probable RBD.36 The PD + RBD cases had an increased synuclein density in 9/10 regions studied, including both subcortical and cortical regions.36 This may suggest that RBD in PD cases may be related to a diffuse and extensive, rather than localized, distribution of CNS synuclein pathology, although as RBD may begin decades prior to death, precise anatomical correlations require further studies of RBD cases without other neurodegenerative disorders.36

Parkinson’s Disease

As described above, LTS can be present in multiple organs outside of the brain, including the heart, GI tract, submandibular gland and skin, and this may play a role in the non-motor complications. Additionally, LTS in the spinal cord is present at all levels and may play a role in some of the non-motor findings in PD as well.12, 13, 23–25, 37

Hyposmia

As discussed above there are numerous papers that have provided evidence for hyposmia in PD, including pathologically confirmed PD.17–20 One hypothesis is that LTS in the olfactory bulb may be the underlying pathology for the hyposmia, while other papers have found a central pathology including LTS in regions of the primary olfactory cortex.4, 15, 38

Constipation

Much has been written in the past few years regarding LTS in the colon, but there have been conflicting reports. As almost all studies have used differing methods and there have been very few replication studies, it is difficult to come to clear conclusions. Findings that have been replicated by multiple groups include a rostral-caudal GI tract gradient of LTS and a greater LTS involvement of the intermyenteric plexus, as compared to the submucosal plexus.12, 22, 39–42 One study reported a correlation of colonic LTS with constipation39 while another did not.22 Within the CNS there is LTS involvement and neuronal loss in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus early in PD and this may also underlie constipation.43 Finally, LTS in the spinal cord,12, 23, 42 including the recent findings in the lateral collateral pathway of the sacral spinal dorsal horn, could explain constipation as well.13, 23–25, 37 It will take many more whole-body autopsies to determine the relative contributions of central and peripheral nervous system pathology to constipation in PD.

Dysphagia

While likely a motor aspect of PD recent data suggests that the pathology that underlies dysphagia may be peripheral rather than central. In small studies of PD cases with and without dysphagia as well as controls, the PD cases with dysphagia had denervated and atrophied muscle fibers, fiber type grouping, and fast-to-slow myosin heavy chain transformation.44 There was also a higher density of LTS in the pharyngeal nerves in PD cases with dysphagia45 as well as axonal LTS in pharyngeal sensory nerves of all PD cases, and not controls, and a higher LTS density in the internal superior laryngeal nerve as compared to the glossopharyngeal nerve or pharyngeal sensory branch of the vagus nerve.46 Further autopsy research with larger numbers of subjects is needed.

Urinary Urgency and Frequency

While there has been little data to suggest LTS is present at high frequency in the bladder itself,12, 47 spinal cord involvement,12, 13, 23–25, 42 including a recent study finding LTS in the lateral collateral pathway of the sacral spinal dorsal horn, could explain this non-motor complication.37

Orthostatic hypotension

This non-motor complication can appear early in PD but most often has a significant impact on quality of life in more advanced cases. Orthostatic hypotension may be due to multiple factors including sympathetic denervation of the heart,48 as well as LTS in the sympathetic ganglia, adrenal gland and cardiac tissue.12, 13, 42, 49 At this time it remains unclear however which may be the primary mechanism and further research is needed.

Cognitive Impairment

The pathologic substrate for PD with mild cognitive impairment (PD-MCI) and PD with dementia (PDD) appears to be heterogeneous and includes LTS, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology, cerebrovascular disease, and other findings.50–55 Neuropathological studies of PD-MCI suggest that neocortical LTS may play a role56 although other studies suggest a higher distribution of LTS in the brainstem or limbic regions.50, 57 These studies found a variable amount of Alzheimer’s disease pathology as well as cerebral amyloid angiopathy.50, 57

In PDD, one important factor appears to be the density and distribution of LTS in the cerebral cortex.51, 58–64 In one study of 12 PDD cases there was a tenfold increase in neocortical and limbic LTS compared to non-demented PD cases.65 However, the influence of cortical LTS is not absolute, as it has been reported that not all patients with cortical LTS will have dementia.59, 66, 67 The AZSAND experience to date is that, of 33 PD subjects with Unified Neocortical Stage IV (without concurrent AD), 17 had dementia while 16 did not (unpublished data).

It is very likely that AD pathology contributes to dementia in many PDD cases but results from many studies are conflicting. Some studies rarely found PDD cases with pathologically defined AD,65, 68 while other studies found a much higher occurrence51, 53, 59, 69 Some studies found the degree of AD changes did not meet neuropathological criteria for AD in any PDD case.56 Neuritic plaque pathology was greater in PDD cases compared with non-demented cases in one study.52 However, PDD cases with and without AD pathology were clinically indistinguishable in one study.53 The AZSAND experience is that the influence of AD pathology on cognition is dominant and the contribution of LTS may only be ascertained with multivariable statistical methods or by excluding subjects meeting neuropathological diagnostic criteria for AD.4 Even when AD lesions do not meet criteria for AD there is still a positive correlation between neocortical LTS and both senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.65,51, 59 It appears likely that there is a pathological and clinical synergism between AD and synuclein disorders, and this requires further research.

The role of other pathologic findings in causing cognitive impairment in PD remains unclear partly due to the common findings of pathologies in all elderly autopsied cases. Vascular changes have been found in some studies54, 56 but less so in others.65, 68, 70 Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, not uncommon in aged controls, has been correlated with PDD,59, 71 and had a positive correlation to LTS in a second study.72

Summary

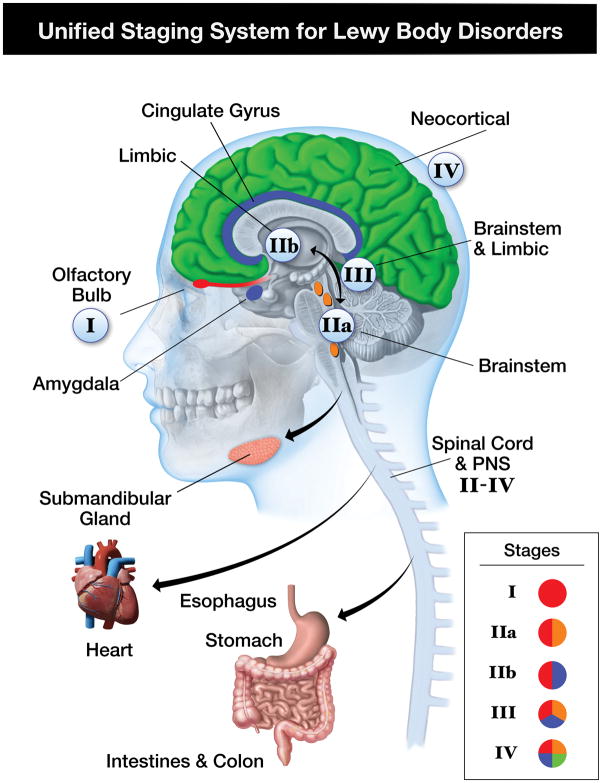

It is now increasingly clear that non-motor findings can predate motor PD and often have a marked impact on quality of life. Recent neuropathological studies have suggested that the basis for these non-motor findings is the systemic distribution of LTS and that it is unlikely that disease of the nigrostriatal pathway is the principal cause. In an effort to classify how synuclein pathology may be associated with clinical findings the Unified Staging System for Lewy Body Disorders (USSLB) was proposed.4 In this system stage I is involvement of the olfactory bulb only, and given that there are almost no cases of ILBD without olfactory bulb involvement, and there are many cases with olfactory bulb as the only region involved, this staging system differs from that of Braak where stage I already involves the medulla/dorsal motor nucleus.73 Clinically this would account for the hyposmia present in ILBD as mentioned above. Stage IIa is brainstem predominant and stage IIb is limbic predominant, and in these stages there can be non-motor features as well as the beginning of motor (IIa) and cognitive (IIb) features. Stage III is when there is a fairly equal amount of involvement of the brainstem and limbic regions while stage IV is the neocortical stage, at which point cognitive impairment is very likely. The involvement of the spinal cord occurs as early as stage II and very likely plays a major role in autonomic and gastrointestinal non-motor symptoms that occur in pre-motor PD as discussed above. It has yet to be determined how early the multi-organ involvement begins although at this time there are only very rare reported cases of synucleinopathy in peripheral organs prior to CNS involvement.12, 15 The USSLB is shown in graphic form in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Unified Staging System for Lewy Body Disorders. In this staging system the presence of peripheral synuclein does not occur until Stage II–IV.

It should be noted that this review paper focuses mainly on the role α-synuclein may play in the non-motor symptoms of PD. At this time it has not been proven that α-synuclein accumulation clearly causes the dysfunction seen and therefore some caution is needed when drawing conclusions on the mechanism of these symptoms.

Conclusion

Extranigral pathology, including synucleinopathy in the spinal cord and multiple non-CNS organs, may explain many of the non-motor signs and symptoms present before and after the onset of motor PD.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Adler has received consulting fees from Allergan, Abbvie, Ipsen, Lundbeck, Merz, and Teva, and received research funding from the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, and the NIH/NINDS.

Dr. Beach receives consulting fees from GE Healthcare and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, receives research funding from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, is paid to conduct neuropathological services for Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Navidea Biopharmaceuticals and Janssen Research and Development and receives research funding from the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, and the NIH/NINDS/NIA.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest for any author on this manuscript.

References

- 1.Postuma RB, Aarsland D, Barone P, et al. Identifying prodromal Parkinson’s disease: pre-motor disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27(5):617–626. doi: 10.1002/mds.24996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler CH, Stern MB. Redefining Parkinson’s Disease. Clinical Insights: Parkinson’s Disease: Diagnosis, Motor Symptoms and Non-Motor Features. 2013:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beach TG, White CL, Hamilton RL, et al. Evaluation of alpha-synuclein immunohistochemical methods used by invited experts. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116(3):277–288. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0409-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beach TG, Adler CH, Lue L, et al. Unified staging system for Lewy body disorders: correlation with nigrostriatal degeneration, cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117(6):613–634. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibb WR, Lees AJ. The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51(6):745–752. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito Y, Ruberu NN, Sawabe M, et al. Lewy body-related alpha-synucleinopathy in aging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2004;63(7):742–749. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.7.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, et al. Reduced striatal tyrosine hydroxylase in incidental Lewy body disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115(4):445–451. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0313-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DelleDonne A, Klos KJ, Fujishiro H, et al. Incidental Lewy body disease and preclinical Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(8):1074–1080. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iacono D, Geraci-Erck M, Rabin ML, et al. Parkinson disease and incidental Lewy body disease: Just a question of time? Neurol. 2015;85:1670–1679. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milber JM, Noorigian JV, Morley JF, et al. Lewy pathology is not the first sign of degeneration in vulnerable neurons in Parkinson disease. Neurol. 2012;79:2307–2314. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318278fe32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickson DW, Fujishiro H, DelleDonne A, et al. Evidence that incidental Lewy body disease is pre-symptomatic Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115(4):437–444. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, et al. Multi-organ distribution of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein histopathology in subjects with Lewy body disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(6):689–702. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0664-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumikura H, Takao M, Hatsuta H, et al. Distribution of α-synuclein in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia in an autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0236-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito S, Takao M, Hatsuta H, et al. Alpha-synuclein immunohistochemistry of gastrointestinal and biliary surgical specimens for diagnosis of Lewy body disease. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:1714–1723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sengoku R, Saito Y, Ikemura M, et al. Incidence and extent of Lewy body-related alpha-synucleinopathy in aging human olfactory bulb. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2008;67(11):1072–1083. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31818b4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adler CH, Connor DJ, Hentz JG, et al. Incidental Lewy body disease: clinical comparison to a control cohort. Mov Disord. 2010;25(5):642–646. doi: 10.1002/mds.22971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross GW, Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, et al. Association of olfactory dysfunction with incidental Lewy bodies. Mov Disord. 2006;21(12):2062–2067. doi: 10.1002/mds.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driver-Dunckley E, Adler CH, Hentz JG, et al. Olfactory dysfunction in incidental Lewy body disease and Parkinson’s disease. Park Rel Disord. 2014;20(11):1260–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stern MB, Doty RL, Dotti M, et al. Olfactory function in Parkinson’s disease subtypes. Neurol. 1994;44(2):266–268. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKinnon J, Evidente V, Driver-Dunckley E, et al. Olfaction in the elderly: A cross-sectional analysis comparing Parkinson’s disease with controls and other disorders. Int J Neurosci. 2010;120:36–39. doi: 10.3109/00207450903428954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbott RD, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, et al. Bowel movement frequency in late-life and incidental Lewy bodies. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2007;22(11):1581–1586. doi: 10.1002/mds.21560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Annerino DM, Arshad S, Taylor GM, Adler CH, Beach TG, Greene JG. Parkinson’s disease is not associated with gastrointestinal myenteric ganglion neuron loss. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124(5):665–680. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1040-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Del Tredici K, Braak H. Spinal cord lesions in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124(5):643–664. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oinas M, Paetau A, Myllykangas L, Notkola IL, Kalimo H, Polvikoski T. alpha-Synuclein pathology in the spinal cord autonomic nuclei associates with alpha-synuclein pathology in the brain: a population-based Vantaa 85+ study. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(6):715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamura T, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y, Sobue G. Lewy body-related α-synucleinopathy in the spinal cord of cases with incidental Lewy body disease. Neuropathol. 2012;32:13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2011.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schenck CH, Bundlie SR, Mahowald MW. Delayed emergence of a parkinsonian disorder in 38% of 29 older men initially diagnosed with idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Neurol. 1996;46(2):388–393. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.2.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ, Lucas JA, Parisi JE. Association of REM sleep behavior disorder and neurodegenerative disease may reflect an underlying synucleinopathy. Mov Disord. 2001;16(4):622–630. doi: 10.1002/mds.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postuma RB, Lang AE, Massicotte-Marquez J, Montplaisir J. Potential early markers of Parkinson disease in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurol. 2006;66(6):845–851. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000203648.80727.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adler CH, Hentz JG, Shill HA, et al. Probable RBD is increased in Parkinson’s disease but not in essential tremor or restless legs syndrome. Park Rel Disord. 2011;17(6):456–458. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Bertrand JA, Genier Marchand D, Montplaisir JY. Parkinson risk in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: preparing for neuroprotective trials. Neurol. 2015;84(11):1104–1113. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahlknecht P, Iranzo A, Hogl B, et al. Olfactory dysfunction predicts early transition to a Lewy body disease in idiopathic RBD. Neurol. 2015;84(7):654–658. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Postuma RB, Iranzo A, Hogl B, et al. Risk factors for neurodegeneration in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a multicenter study. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(5):830–839. doi: 10.1002/ana.24385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bodis-Wollner I, Kozlowski PB, Glazman S, Miri S. alpha-synuclein in the inner retina in parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(6):964–966. doi: 10.1002/ana.24182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beach TG, Carew J, Serrano G, et al. Phosphorylated alpha-synuclein-immunoreactive retinal neuronal elements in Parkinson’s disease subjects. Neurosci Lett. 2014;571:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ, et al. Clinicopathologic correlations in 172 cases of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder with or without a coexisting neurologic disorder. Sleep Med. 2013;14(8):754–762. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Postuma RB, Adler CH, Dugger BN, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder and neuropathology in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(10):1413–1417. doi: 10.1002/mds.26347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.VanderHorst VG, Samardzic T, Saper CB, et al. alpha-Synuclein pathology accumulates in sacral spinal visceral sensory pathways. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(1):142–149. doi: 10.1002/ana.24430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silveira-Moriyama L, Holton JL, Kingsbury A, et al. Regional differences in the severity of Lewy body pathology across the olfactory cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2009;453(2):77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lebouvier T, Neunlist M, Bruley des Varannes S, et al. Colonic biopsies to assess the neuropathology of Parkinson’s disease and its relationship with symptoms. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pouclet H, Lebouvier T, Coron E, et al. A comparison between rectal and colonic biopsies to detect Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of disease. 2012;45(1):305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Takeda S, Ohama E, Ikuta F. Parkinson’s disease: the presence of Lewy bodies in Auerbach’s and Meissner’s plexuses. Acta Neuropathol. 1988;76(3):217–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00687767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gelpi E, Navarro-Otano J, Tolosa E, et al. Multiple organ involvement by alpha-synuclein pathology in Lewy body disorders. Mov Disord. 2014;29(8):1010–1018. doi: 10.1002/mds.25776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Del Tredici K, Rub U, De Vos RA, Bohl JR, Braak H. Where does parkinson disease pathology begin in the brain? J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2002;61(5):413–426. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mu L, Sobotka S, Chen J, et al. Altered pharyngeal muscles in Parkinson disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2012;71(6):520–530. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318258381b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mu L, Sobotka S, Chen J, et al. Alpha-synuclein pathology and axonal degeneration of the peripheral motor nerves innervating pharyngeal muscles in Parkinson disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2013;72(2):119–129. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182801cde. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mu L, Sobotka S, Chen J, et al. Parkinson disease affects peripheral sensory nerves in the pharynx. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2013;72(7):614–623. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182965886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minguez-Castellanos A, Chamorro CE, Escamilla-Sevilla F, et al. Do alpha-synuclein aggregates in autonomic plexuses predate Lewy body disorders?: A cohort study. Neurol. 2007;68(23):2012–2018. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264429.59379.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orimo S, Amino T, Itoh Y, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation precedes neuronal loss in the sympathetic ganglia in Lewy body disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109(6):583–588. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-0995-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fumimura Y, Ikemura M, Saito Y, et al. Analysis of the adrenal gland is useful for evaluating pathology of the peripheral autonomic nervous system in lewy body disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2007;66(5):354–362. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3180517454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adler CH, Caviness JN, Sabbagh MN, et al. Heterogeneous neuropathological findings in Parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:829–830. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0744-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hurtig HI, Trojanowski JQ, Galvin J, et al. Alpha-synuclein cortical Lewy bodies correlate with dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Neurol. 2000;54(10):1916–1921. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.10.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jellinger KA. Pathological substrate of dementia in Parkinson’s disease--its relation to DLB and DLBD. Park Rel Disord. 2006;12(2):119–120. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sabbagh MN, Adler CH, Lahti TJ, et al. Parkinson disease with dementia: comparing patients with and without Alzheimer pathology. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(3):295–297. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819c5ef4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi SA, Evidente VG, Caviness JN, et al. Are there differences in cerebral white matter lesion burdens between Parkinson’s disease patients with or without dementia? Acta Neuropatholog. 2009;119:147–149. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0620-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dugger BN, Davis K, Malek-Ahmadi M, et al. Neuropathological comparisons of amnestic and nonamnestic mild cognitive impairment. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:146. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0403-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aarsland D, Perry R, Brown A, Larsen JP, Ballard C. Neuropathology of dementia in Parkinson’s disease: a prospective, community-based study. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(5):773–776. doi: 10.1002/ana.20635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jellinger KA. Neuropathology in Parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(6):829–830. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0755-1. author reply 831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mattila PM, Rinne JO, Helenius H, Dickson DW, Roytta M. Alpha-synuclein-immunoreactive cortical Lewy bodies are associated with cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100(3):285–290. doi: 10.1007/s004019900168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Irwin DJ, White MT, Toledo JB, et al. Neuropathologic substrates of Parkinson disease dementia. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(4):587–598. doi: 10.1002/ana.23659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Yu L, Boyle PA, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. Cognitive impairment, decline and fluctuations in older community-dwelling subjects with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 10):3005–3014. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haroutunian V, Serby M, Purohit DP, et al. Contribution of Lewy body inclusions to dementia in patients with and without Alzheimer disease neuropathological conditions. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1145–1150. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.8.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Braak H, Rub U, Jansen Steur EN, Del Tredici K, de Vos RA. Cognitive status correlates with neuropathologic stage in Parkinson disease. Neurol. 2005;64(8):1404–1410. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158422.41380.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, et al. Modeling the association between 43 different clinical and pathological variables and the severity of cognitive impairment in a large autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Brain Pathol. 2010;20(1):66–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Howlett DR, Whitfield D, Johnson M, et al. Regional Multiple Pathology Scores Are Associated with Cognitive Decline in Lewy Body Dementias. Brain Pathol. 2015;25(4):401–408. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Apaydin H, Ahlskog JE, Parisi JE, Boeve BF, Dickson DW. Parkinson disease neuropathology: later-developing dementia and loss of the levodopa response. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(1):102–112. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Colosimo C, Hughes AJ, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Lewy body cortical involvement may not always predict dementia in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2003;74(7):852–856. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kempster PA, O’Sullivan SS, Holton JL, Revesz T, Lees AJ. Relationships between age and late progression of Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 6):1755–1762. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hely MA, Reid WG, Adena MA, Halliday GM, Morris JG. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson’s disease: the inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov Disord. 2008;23(6):837–844. doi: 10.1002/mds.21956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mattila PM, Roytta M, Torikka H, Dickson DW, Rinne JO. Cortical Lewy bodies and Alzheimer-type changes in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1998;95(6):576–582. doi: 10.1007/s004010050843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Halliday G, Hely M, Reid W, Morris J. The progression of pathology in longitudinally followed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115(4):409–415. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bertrand E, Lewandowska E, Stepien T, Szpak GM, Pasennik E, Modzelewska J. Amyloid angiopathy in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Folia Neuropathol. 2008;46(4):255–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ghebremedhin E, Rosenberger A, Rub U, et al. Inverse relationship between cerebrovascular lesions and severity of lewy body pathology in patients with lewy body diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2010;69(5):442–448. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181d88e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]