A randomized, controlled trial of peer mentoring for out-of-care persons hospitalized with human immunodeficiency virus infection had no effect on retention in care and viral load 6 months after discharge. Data suggest more intense and system-focused interventions warrant further study.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, retention in care, adherence to care, peer, patient navigation

Abstract

Background. Few interventions have been shown to improve retention in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care, and none have targeted the hospitalized patient. Peer mentoring has not been rigorously tested.

Methods. We conducted a randomized, controlled clinical trial of a peer mentoring intervention. Eligible adults were hospitalized and were either newly diagnosed with HIV infection or out of care. The intervention included 2 in-person sessions with a volunteer peer mentor while hospitalized, followed by 5 phone calls in the 10 weeks after discharge. The control intervention provided didactic sessions on avoiding HIV transmission on the same schedule. The primary outcome was a composite of retention in care (completed HIV primary care visits within 30 days and between 31 and 180 days after discharge) and viral load (VL) improvement (≥1 log10 decline) 6 months after discharge.

Results. We enrolled 460 participants in 3 years; 417 were in the modified intent-to-treat analysis. The median age was 42 years; 74% were male; and 67% were non-Hispanic black. Baseline characteristics did not differ between the randomized groups. Twenty-eight percent of the participants in both arms met the primary outcome (P = .94). There were no differences in prespecified secondary outcomes, including retention in care and VL change. Post hoc analyses indicated interactions between the intervention and length of hospitalization and between the intervention and receipt of linkage services before discharge.

Conclusions. Peer mentoring did not increase reengagement in outpatient HIV care among hospitalized, out-of-care persons. More intense and system-focused interventions warrant further study.

Clinical Trials Registration. NCT01103856.

In the United States as many as 40% of people who are aware of their human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are not in regular HIV primary care [1, 2]. Poor retention in HIV care affects access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and survival [3, 4] and is associated with lower rates of HIV viral suppression. As a result, more HIV transmissions originate from the population that is poorly retained in care than both the population in care and the population unaware of their infection combined [3, 5–8]. Despite the critical role retention in care plays in both individual and population health, there are few interventions proven to better retain patients in HIV primary care [9].

Hospitalization is not uncommon in persons with HIV infection, especially in persons with uncontrolled or advanced HIV infection [10–13]. Hospitalization may be an opportunity to engage patients when they are particularly apt to consider behavior change, given their acute illness.

Peer navigator interventions using patients or paraprofessionals as interventionists have proven effective at improving self-management for cancer and some chronic diseases [14–16]. Because of their credibility with fellow patients and their own experiences in successfully overcoming barriers and achieving lifestyle changes, peer mentors possess unique skills and power to promote confidence, model success, and provide navigation to patients who do not adhere to adaptive self-management routines. The information, motivation, and behavioral (IMB) skills health behavior model suggests that providing information and increasing motivation and skills around treatment retention would contribute to engaging individuals in care [17].

Few studies have rigorously examined the efficacy of peer-mentoring interventions in HIV-infected persons [18–20]. The Thomas Street Health Center (TSHC) in Houston, Texas, is one of the largest outpatient HIV clinics in the United States. It has a long-standing volunteer peer mentor program for patients new to the clinic. Based on that program, we developed a structured, IMB theory-based, patient mentor program to improve retention in HIV primary care for hospitalized patients. We reasoned that the intervention needs to be brief, since any patient who could be recruited into a multisession intervention could likely be recruited back into primary care. We tested the efficacy of the intervention in a randomized, controlled trial of patients hospitalized in our public hospital. We hypothesized that the intervention, called the Mentor Approach for Promoting Patient Self-care (MAPPS), would improve retention in care and viral load (VL), as well as a number of secondary outcomes, over a 6-month period.

METHODS

Participants and Performance Sites

The study was performed in Houston's Harris Health System, which operates both Ben Taub General Hospital (BTGH) and TSHC. Harris Health System provides care primarily to uninsured and publically insured persons. TSHC is a free-standing HIV clinic located about 6 miles from BTGH. Patients with HIV infection were recruited from BTGH regardless of reason for admission. Eligibility criteria included the following: expectation to spend at least 1 more night in the hospital (to allow time for intervention delivery); age at least 18 years; able to speak English or Spanish; no intension of using a clinic other than TSHC for HIV primary care after discharge from the hospital, because the mentoring was TSHC specific; and cognitively and physically able to provide informed consent and participate in the study. Potential participants were excluded if they were currently in prison or if, in the opinion of the primary medical team, they were likely to be discharged to an institutional setting, die during the hospital stay, or be discharged to hospice. Finally, to be eligible, patients could not be “in care,” which we defined as having completed an HIV primary care visit at TSHC in at least 3 of the 4 previous quarter-years and having had at least 3 consecutive HIV VL results <400 c/mL over at least 6 months, the most recent of which was within 3 months of enrollment. All persons not in care were defined as “out of care,” including persons who were diagnosed with HIV infection for less than 1 year and patients who intended to transfer care to TSHC after discharge.

Peer Mentoring and Control Interventions

The peer mentoring intervention was originally developed as a programmatic intervention for outpatients newly entering care at TSHC, and we adapted that intervention using the IMB model [17, 21]. The modified intervention, that is, MAPPS, was designed to provide services to hospitalized HIV-infected patients who had never been in outpatient HIV care, are poorly retained in care, or have detectable HIV VL despite adequate retention in care.

The intervention, mentor training, and quality-control processes have been previously described [22]. Briefly, the intervention is delivered during 2 in-person sessions in the hospital, each typically lasting between 20 and 45 minutes, followed by 5 telephone calls after discharge over the next 10 weeks. The intervention focused on mentors serving as role models for successfully managing HIV infection and for encouraging active self-management. The tone of the interactions was conversational, not didactic. Information was provided in the form of standard brochures and brief instruction as needed regarding navigating the HIV care system, options for care, and the impact of medications, all focused around the importance of obtaining outpatient HIV care. Motivational factors relied on the mentors sharing their personal stories, many of which involved overcoming substance use, incarceration, and other barriers to care, in order to build rapport and instill hope. Behavioral skills components asked participants to identify barriers and facilitators to outpatient care, followed by goal-setting and action-planning to increase care-seeking behavior. Mentor training included in-person group workshops, informal role-playing, standardized role-playing, and then certification with standardized patients. Mentors were recertified with standardized patients every 6 months [22]. Seven volunteer mentors provided intervention services over the course of the study.

The control intervention was delivered on the same schedule as the MAPPS intervention but with a different goal and approach. It was based on Project Respect and provided instruction on safer sex and safer drug use for persons living with HIV infection [23]. Its contact time was comparable to that of MAPPS, including in-person and telephone sessions, but was didactic and did not promote therapeutic bonding between instructors and participants. Paid educators delivered the intervention. The control intervention had no focus on retention in care or HIV treatment.

Measures and Outcomes

Enrolled persons completed a baseline survey before receiving any intervention. Follow-up interviews were conducted 3 and 6 months after discharge and included a survey and phlebotomy for VL and CD4 cell count testing. Follow-up interviews were not conducted at TSHC in order to avoid biasing the participants to come to TSHC. Participants were compensated for the baseline and follow-up interviews. Participants were not compensated for completing intervention sessions or intervention phone calls.

Surveys assessed demographics; alcohol and substance use [24, 25]; physical functioning, role limitations due to physical functioning, social functioning, and general health domains of health-related quality of life [26]; unmet need for 19 different medical and social services [27]; depressive symptomatology [28]; and adherence to ART [29]. Date of HIV diagnosis and prescription of ART were confirmed by medical record review. Appointment data from TSHC were electronically available and imported into study databases. If participants reported using medical facilities outside the Harris Health System during follow-up, those medical records were reviewed and abstracted.

The prespecified primary outcome was a composite dichotomous variable. It consisted of a “retention in care” component and a “VL improvement” component. The retention in care component included attending at least 1 HIV primary care visit within 30 days of discharge and attending at least 1 HIV primary care visit between 31 and 180 days after discharge. The VL improvement component was defined as achieving at least a 1 log10 decrease in VL or a VL <400 c/mL (if baseline VL was <4000 c/mL) at 6 months after discharge. Participants with no indication for ART at the time of discharge, according to treatment guidelines at the time [30], only needed to meet the retention in care component of the definition to be considered a “success”; all others needed to meet both the retention and VL components to be considered a success. Participants who did not meet the definition of success were considered “failures.”

Additional details on the methods, including blinding and randomization procedures, are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Sample Size and Data Analyses

The primary analysis was prespecified as a modified intent-to-treat (mITT) analysis that included participants regardless of dose of intervention received. We prespecified that we would exclude participants who withdrew consent and participants reported by themselves or their contacts to have moved out of the Houston, Texas, area or to have been incarcerated or institutionalized during follow-up. Participants with missing outcome data or who died during follow-up were considered failures.

We powered the study to detect a minimum absolute difference of 15% in the primary outcome between the study arms, similar to the Antiretroviral Treatment and Access to Services Study [31]. Based on preliminary data, we estimated that 37% of participants in the control arm would meet the primary outcome. Assuming 80% power and a 2-sided alpha-error level equal to .05, we needed 173 participants per arm. We estimated that up to 20% of participants would be removed from the primary analysis due to the prespecified exclusion criteria, resulting in a need for 217 participants per arm. During enrollment and before any data analysis, we realized that a baseline VL had not been obtained for a small number of participants as a standard of care during their hospitalization, complicating their outcome assignment. We therefore increased the enrollment target to 460 participants.

Wald χ2 tests and their accompanying P values were calculated to compare success in the intervention and control groups. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with Poisson binary regression. Except for the increase in sample size, there were no changes to the protocol or the outcome measures. No interim analyses were conducted.

The institutional review board for the Baylor College of Medicine and affiliated hospitals approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

Participants and Follow-up

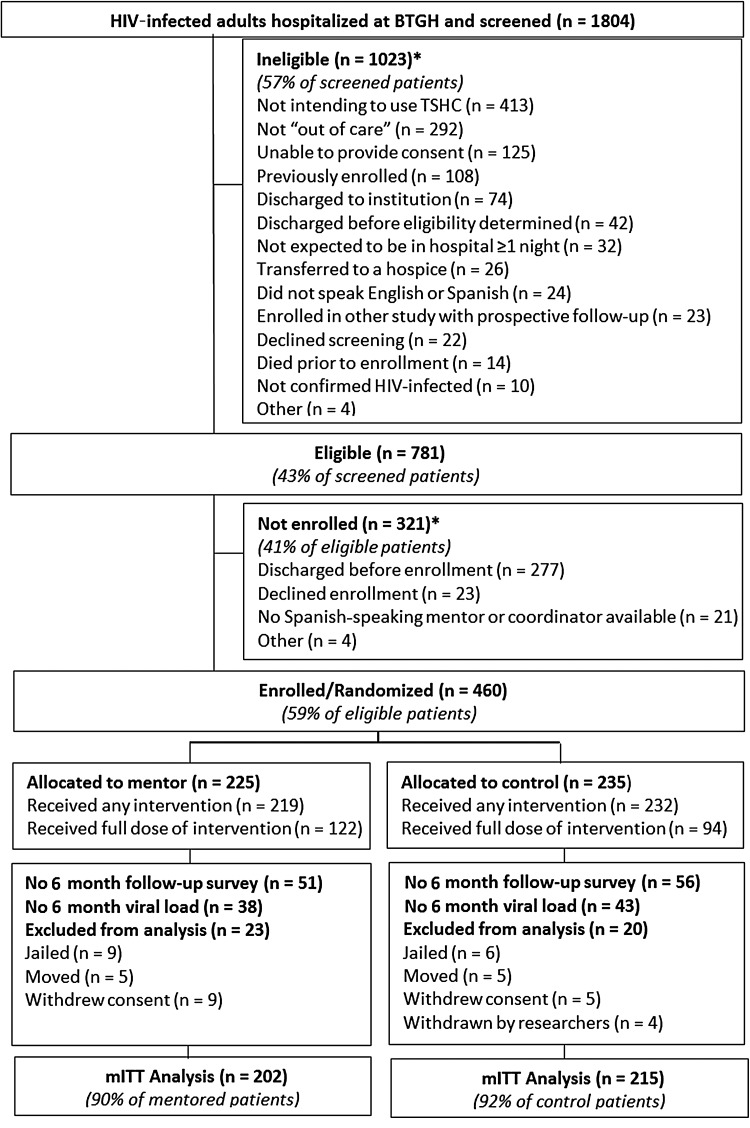

Between August 2010 and August 2013, we screened 1804 HIV-infected patients hospitalized at BTGH, of whom 781 (43%) were eligible for the study; 460 (59% of those eligible), the target number, were enrolled (Figure 1). Patients who were eligible yet not enrolled were similar in age and sex to patients who did enroll in the study. More enrolled participants had CD4 cell count <200 cells/µL than eligible persons who were not enrolled (64% vs 50%). Because Spanish-speaking mentors and research staff were not available every work day, the percentage of persons who were Hispanic was higher in the group that was eligible but not enrolled than in the enrolled group (30% vs 19%, respectively; P < .0001; Supplementary Table 1). Very few patients declined screening (n = 21) or enrollment (n = 23).

Figure 1.

Definition of the Mentor Approach for Promoting Patient Self-care study cohort. *Reasons not mutually exclusive. Abbreviations: BTGH, Ben Taub General Hospital; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; mITT, modified intent to treat; TSHC, Thomas Street Health Center.

Per protocol, 43 enrolled participants were dropped before data analysis (Figure 1), leaving 417 participants (91% of enrolled) in the mITT analyses. A total of 202 participants (48%) received the mentoring intervention and 215 (52%) received the control intervention. Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics did not differ between the arms (Table 1). Eighty-one percent of participants in the mentor group and 88% in the control group received both inpatient sessions. Sixty-one percent of mentored participants and 44% of control participants received 2 inpatient sessions plus at least 3 phone calls (P < .01). Six-month follow-up for study interviews was 74% in both arms and was 81% among participants alive and eligible for follow-up; 88% had a 6-month VL (some participants who did not complete a study visit had a VL obtained from medical record review).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 417 Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Enrolled in the Mentor Approach for Promoting Patient Self-care Study, Houston, Texas, Between 2010 and 2013

| Characteristic | Mentored Arm n = 202 (%) | Control Arm n = 215 (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | .54 | ||

| Male | 145 (72) | 160 (74) | |

| Female | 57 (28) | 55 (26) | |

| Race | .34 | ||

| Black | 131 (65) | 147 (68) | |

| Hispanic | 45 (22) | 36 (17) | |

| White | 26 (13) | 32 (15) | |

| Age, y | .94 | ||

| <30 | 26 (13) | 26 (13) | |

| 30–39 | 53 (26) | 61 (28) | |

| 40–49 | 73 (36) | 73 (34) | |

| ≥50 | 50 (25) | 55 (26) | |

| Initial viral load, c/mL | .16 | ||

| ≤400 | 44 (22) | 41 (19) | |

| 400–100 000 | 70 (35) | 60 (28) | |

| >100 000 | 86 (43) | 111 (52) | |

| Initial CD4 count, cells/µL | .11 | ||

| <200 | 132 (66) | 137 (64) | |

| 200–349 | 19 (10) | 37 (17) | |

| 350–500 | 13 (7) | 12 (6) | |

| >500 | 36 (18) | 29 (13) | |

| ART indication | .52 | ||

| On ART or has indication for ART | 191 (95) | 200 (93) | |

| No Indication for ART | 11 (5) | 15 (7) | |

| ART use and adherence | |||

| Prescribed ART | 133 (66) | 146 (68) | .65 |

| Taking ART in the last 4 weeks | 79 (39) | 81 (37) | .69 |

| Adherence (n = 187), median (25th, 75th percentile) | 91 (33, 99) | 75 (3, 99) | .31 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus diagnosis | .77 | ||

| New this hospitalization | 24 (12) | 23 (10) | |

| Previous, <1 y since diagnosis | 33 (16) | 32 (15) | |

| >1 y since diagnosis | 145 (72) | 161 (75) | |

| Substance abuse in last 3 mo | .10 | ||

| Any drug use not including marijuana | 45 (23) | 66 (31) | |

| Marijuana only | 28 (14) | 33 (16) | |

| None | 126 (63) | 114 (54) | |

| Depression | .55 | ||

| Not depressed: PHQ8 < 10 | 111 (56) | 112 (52) | |

| Depressed: PHQ8 ≥ 10 | 89 (45) | 102 (48) | |

| Employment status | .40 | ||

| Employed | 45 (23) | 41 (19) | |

| Not employed | 155 (76) | 174 (81) | |

| Insurance | .75 | ||

| Private insurance, Medicare or Medicaid | 56 (28) | 67 (31) | |

| Harris Health System enrollee | 83 (42) | 89 (42) | |

| No insurance, not Harris Health System enrollee | 58 (29) | 57 (28) | |

| Unmet needs | .74 | ||

| Median count (25th, 75th percentile) | 3 (1, 6) | 3 (1, 6) | |

| Health-related quality-of-life scores | |||

| General health, mean (SD) | 43.3 (24) | 44.8 (25) | .52 |

| Social function, mean (SD) | 50.3 (29) | 52.5 (31) | .44 |

| Physical function, mean (SD) | 50.9 (33) | 53.9 (34) | .44 |

| Physical limitation, mean (SD) | 36.0 (31) | 40.8 (34) | .13 |

| Hospital stay characteristics | |||

| Days hospitalized, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 6 (4, 10) | 6 (4, 11) | .76 |

| Saw service linkage worker before discharge | 136 (67) | 147 (68) | .82 |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; PHQ, patient health questionnaire; SD, standard deviation.

Outcomes

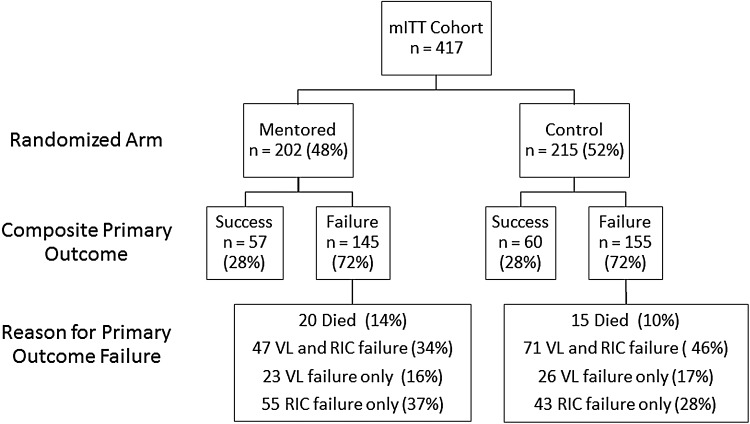

In the primary outcome 117 participants attained success (28%). There were no significant differences in success between the mentor and the control intervention groups, both with 28% success for the primary outcome (P = .94; Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes at 6 Months in the Mentor Approach for Promoting Patient Self-care Study

| Outcome | Mentored Arm n = 202 (%) |

Control Arm n = 215 (%) |

P Value | Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval) Mentored vs Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome at 6 mo | ||||

| Both retention in carea and VL improvementb | 57 (28) | 60 (28) | .94 | 1.0 (.81, 1.26) |

| Secondary outcomes at 6 mo | ||||

| Retention measures | ||||

| Visit within 30 d of discharge | 99 (49) | 104 (48) | .90 | 1.01 (.83, 1.24) |

| Retention in carea | 80 (40) | 86 (40) | .93 | 0.99 (.81, 1.21) |

| Laboratory measures | ||||

| VL improvementb | 110 (54) | 103 (48) | .18 | 1.15 (.94, 1.40) |

| VL < 400 c/mL | 92 (46) | 84 (39) | .18 | 1.15 (.94, 1.40) |

| CD4 ≥ 350 cells/µL | 52 (26) | 47 (22) | .35 | 1.11 (.89, 1.39) |

| CD4 ≥ 500 cells/µL | 35 (17) | 27 (13) | .17 | 1.20 (.94, 1.53) |

| ART and adherence measures | ||||

| Prescribed ART | 153 (76) | 165 (77) | .81 | 0.97 (.77, 1.22) |

| Taking ART | 123 (61) | 130 (61) | .93 | 1.01 (.82, 1.24) |

| Adherence to ART (n = 249), median (25th, 75th percentile) | 98 (90, 100) | 97 (80, 100) | .23 | |

| Healthcare utilization measures | ||||

| Hospitalized, at least once | 87 (43) | 85 (40) | .46 | 1.08 (.88, 1.32) |

| Emergency room visit not resulting in admission, at least once | 58 (29) | 72 (34) | a.29 | 0.89 (.71, 1.11) |

| Health-related quality-of-life measures (n = 309), mean change from baseline (SD) | ||||

| General health | 5.90 (27) | 7.96 (25) | .49 | N/A |

| Social function | 9.52 (38) | 4.73 (40) | .32 | N/A |

| Physical function | 6.06 (40) | 0.86 (35) | .19 | N/A |

| Physical limitation | 13.27 (54) | 4.14 (45) | .05 | N/A |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; N/A, not applicable; SD, standard deviation; VL, viral load.

a Retention in care is defined as completing at least 1 primary care visit between 1 and 30 days after hospital discharge and at least 1 subsequent primary care visit between 31 and 180 days after discharge.

b VL improvement is defined as VL at 6 months after discharge that was reduced by 1 log10 from baseline or was <400 c/mL (if baseline VL was <4000 c/mL). Missing VL = failure.

Figure 2.

Outcomes in the Mentor Approach for Promoting Patient Self-care (MAPPS) study by arm. Primary outcome and reason for failure in the MAPPS study. P value for success in the primary outcome = 0.94. Viral load (VL) success is a 6-month VL that is reduced by 1 log10 from baseline or is <400 c/mL if the baseline VL was <4000. Missing VL = failure. Retention in care (RIC) success is at least 1 primary care visit between 1 and 30 days after hospital discharge and at least 1 subsequent primary care visit between 31 and 180 days after discharge. Abbreviation: mITT, modified intent to treat.

There were no statistically significant differences in our prespecified secondary outcomes (Table 2). Forty percent of participants in both arms met the definition for the retention in care component of the primary outcome (P = .93). The mentor group and control group were also equally likely to attend a primary care visit within 30 days of discharge (49% vs 48%, P = .90), have VL improvement (54% vs 48%, P = .18), and reach a VL < 400 c/mL (46% vs 39%, P = .18). A number of other prespecified secondary outcomes measured improvements in varying aspects of health, including HIV-specific indicators, health services use, and patient-reported outcomes. Similar success was found across the 2 groups in these secondary outcomes (Table 2). There were no differences in outcomes in prespecified analyses limited to persons who had a 6-month follow-up visit (Supplementary Table 2). No adverse events or harm attributable to the interventions were reported.

To better understand these null results, we conducted a number of post hoc analyses. There were no differences in outcomes by randomized group in analyses restricted to participants who received a high dose of the intervention (Supplementary Table 3). There were also no meaningful differences in outcomes when we stratified the participants by age, sex, and race/ethnicity, as well as by baseline levels of depression, substance use, and unmet social service needs (Supplementary Table 4).

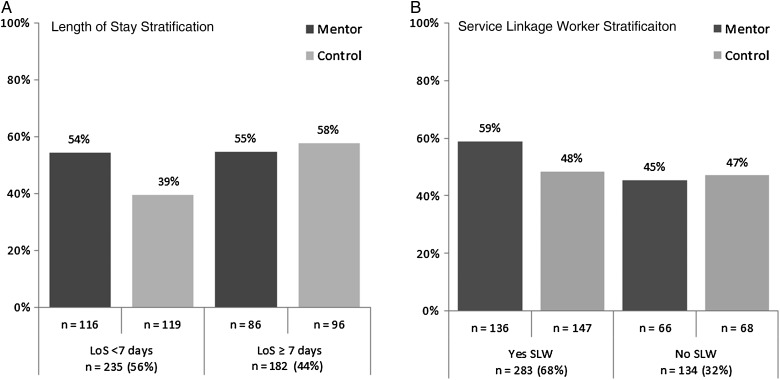

Next, we turned to system factors and identified 2 factors that impacted effectiveness of the MAPPS intervention: length of hospital stay and receipt of services from a service linkage worker. In participants with shorter hospital stays, a significantly greater proportion of participants had VL improvement in the mentor arm compared with the control arm. This difference was not apparent in participants with longer lengths of stay (Figure 3A). Regarding receipt of services from a service linkage worker, Harris Health has an HIV service linkage worker stationed at BTGH. The worker provides brief HIV counseling and ensures that HIV-infected persons throughout the hospital have follow-up appointments scheduled at TSHC or helps them link to the clinic of their choice. Two-thirds of the participants received these services (Table 3). We found an interaction between the mentoring intervention and a visit from the service linkage worker, with benefit from the combination of the 2 (Figure 3B). In a single Poisson binary multivariable regression model of VL improvement, adjusted for baseline CD4 cell count, there were interactions between mentoring and length of stay (P = .04) and between mentoring and a service linkage worker visit (P = .12). Mentored participants with a service linkage worker visit and length of stay <7 days had a 1.58 relative risk (95% CI, 1.10, 2.27) of VL improvement at 6 months compared with other participants (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Viral load improvement by arm, stratified by length of stay (LOS) in the hospital (A) and by seeing a service linkage worker (SLW) before discharge (B), in the Mentor Approach for Promoting Patient Self-care study.

Table 3.

Multivariable Model of the Interactions Between Mentoring, Service Linkage Worker Visit, and Length of Stay on Viral Load Improvement at 6 Months in the Mentor Approach for Promoting Patient Self-care Study

| Service Linkage Worker Visit During Hospitalization | Length of Hospital Stay | Randomized Group | Viral Load Improvement (%) | Adjusted Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval)a Mentored vs Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | <7 d | Mentor | 39 (58) | 1.58 (1.10, 2.27) |

| Control | 27 (37) | Referent | ||

| ≥7 d | Mentor | 41 (59) | 1.04 (.80, 1.37) | |

| Control | 44 (59) | Referent | ||

| No | <7 d | Mentor | 24 (49) | 0.88 (.56, 1.40) |

| Control | 20 (44) | Referent | ||

| ≥7 d | Mentor | 6 (35) | 0.67 (.32, 1.40) | |

| Control | 12 (55) | Referent |

a Adjusted for baseline CD4 cell count.

DISCUSSION

Few interventions to improve retention in HIV have been studied in rigorous trials [32]. We conducted a randomized, controlled trial to determine if peer mentors could improve retention in care and virologic control among hospitalized patients out of HIV care. While the proportion of participants with VL < 400 c/mL doubled between baseline and 6 months, the mentoring intervention was no more successful in improving retention and virologic status than the control intervention. The mentoring intervention also had little effect on secondary outcomes.

There are a number of possible explanations for the failure of the intervention in comparison to the control intervention. The mentoring intervention was brief (10 weeks); a longer intervention period may be needed to improve outcomes. The intervention largely focused on improving IMB skills. While these components may be important drivers of care-seeking behavior and self-management, they may not be adequate to overcome other structural, economic, and social barriers to care, such as transportation problems, housing and food needs, substance use, and mental health problems. Coupling mentoring with case management and social services provision could be a more fruitful intervention; indeed, in post hoc analyses, we saw evidence supporting that approach.

The mentoring intervention also may have failed in comparison to the control intervention because the control intervention may have included effective elements, that is, support and motivation over and above the didactic lessons on safer sex. This effect would limit our ability to see differences between the arms. We did not have a “usual care” arm with which to compare outcomes.

In post hoc analyses, the mentoring intervention did result in higher rates of VL improvement in participants with shorter hospitalizations and participants who received HIV linkage services before discharge. Persons with longer lengths of stay had better virologic outcomes regardless of arm, while the mentoring intervention brought persons with the shorter lengths of stay to levels comparable to persons with longer lengths of stay (Figure 3A). The intervention may be particularly potent in persons who are not as acutely ill (manifest by a shorter length of stay) who are therefore in better condition to receive the intervention. Such persons may also have a greater need for increased motivation to care for their illness, since less advanced HIV disease is a known predictor of worse retention in care [33]. Participants who received service linkage services and mentoring were also more likely to achieve VL improvement. Mentoring to provide motivation, support, and information could be particularly potent in collaboration with services to overcome structural barriers. A more prolonged intervention that adjusts to the length of stay or that is customized to a participant's social service needs might be more universally potent.

Our study had a number of limitations. It enrolled participants from a single hospital, which may have affected generalizability. There were few mentors and control interventionists, and so interventionist effects could have impacted the outcomes; the sample size was not sufficient to assess for interventionist effects. Loss to follow-up may have limited the study's power, especially for patient-reported outcomes.

Despite considerable uptake, interventions using mentors have been proven successful in a limited number of studies [14–16]. In this randomized study of a patient mentoring intervention for persons with HIV infection, we did not find a significant effect on retention in HIV care or VL improvement. While our results do not support implementation of the MAPPS approach broadly, they do suggest a role for mentors for persons hospitalized with less severe disease and in concert with linkage services, and clearly support the need for additional research.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://cid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors express their deep gratitude to the volunteer patient mentors who dedicated their time and effort to this study, the many research and education staff who conducted critical elements of the study, and the patients who volunteered for the study.

Disclaimer. The funding agencies had no role in the study design or conduct and did not review or approve this report.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01MH085527; T. P. G.), use of core services of the Baylor College of Medicine–University of Texas Houston Center for AIDS Research (grant number AI036211; J. Butel), a training grant to A. B. (grant number T32AI07456; W. Shearer), and the facilities and resources of the Harris Health System and the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center.

Potential conflicts of interest. K. R. A. has disclosed the following potential conflicts of interest: consultancy with Gilead Sciences and an educational grant from Gilead Sciences. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ et al. Vital signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63:1113–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, Crepaz N. Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons: a meta-analysis. AIDS 2010; 24:2665–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC Jr et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:1493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giordano TP, White AC Jr, Sajja P et al. Factors associated with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients newly entering care in an urban clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003; 32:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doshi RK, Milberg J, Isenberg D et al. High rates of retention and viral suppression in the US HIV safety net system: HIV care continuum in the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, 2011. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skarbinski J, Rosenberg E, Paz-Bailey G et al. Human immunodeficiency virus transmission at each step of the care continuum in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joy R, Druyts EF, Brandson EK et al. Impact of neighborhood-level socioeconomic status on HIV disease progression in a universal health care setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47:500–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Recsky MA, Brumme ZL, Chan KJ et al. Antiretroviral resistance among HIV-infected persons who have died in British Columbia, in the era of modern antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2004; 190:285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann Intern Med 2012; 156:817–284, W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry SA, Fleishman JA, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Trends in reasons for hospitalization in a multisite United States cohort of persons living with HIV, 2001–2008. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 59:368–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford N, Shubber Z, Meintjes G et al. Causes of hospital admission among people living with HIV worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 2015; 2:e438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metsch LR, Bell C, Pereyra M et al. Hospitalized HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Public Health 2009; 99:1045–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nijhawan AE, Clark C, Kaplan R, Moore B, Halm EA, Amarasingham R. An electronic medical record-based model to predict 30-day risk of readmission and death among HIV-infected inpatients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 61:349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, Xie B. Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med 2007; 44:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long JA, Jahnle EC, Richardson DM, Loewenstein G, Volpp KG. Peer mentoring and financial incentives to improve glucose control in African American veterans: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012; 156:416–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinrich SP, Boyd MD, Weinrich M, Greene F, Reynolds WA Jr, Metlin C. Increasing prostate cancer screening in African American men with peer-educator and client-navigator interventions. J Cancer Educ 1998; 13:213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith LR, Fisher JD, Cunningham CO, Amico KR. Understanding the behavioral determinants of retention in HIV care: a qualitative evaluation of a situated information, motivation, behavioral skills model of care initiation and maintenance. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012; 26:344–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purcell DW, Latka MH, Metsch LR et al. Results from a randomized controlled trial of a peer-mentoring intervention to reduce HIV transmission and increase access to care and adherence to HIV medications among HIV-seropositive injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007; 46(suppl 2):S35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simoni JM, Huh D, Frick PA et al. Peer support and pager messaging to promote antiretroviral modifying therapy in Seattle: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 52:465–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genberg BL, Shangani S, Sabatino K et al. Improving engagement in the HIV care cascade: A systematic review of interventions involving people living with HIV/AIDS as peers. AIDS Behav 2016; doi:10.1007/s10461-016-1307-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol 2006; 25:462–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cully JA, Mignogna J, Stanley MA et al. Development and pilot testing of a standardized training program for a patient-mentoring intervention to increase adherence to outpatient HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012; 26:165–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM Jr et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. JAMA 1998; 280:1161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158:1789–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction 2008; 103:1039–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rumptz MH, Tobias C, Rajabiun S et al. Factors associated with engaging socially marginalized HIV-positive persons in primary care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2007; 21(suppl 1):S30–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord 2009; 114:163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giordano TP, Guzman D, Clark R, Charlebois ED, Bangsberg DR. Measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a diverse population using a visual analogue scale. HIV Clin Trials 2004; 5:74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DHHS Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services, ed, 2011:1–166.

- 31.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS 2005; 19:423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.CDC. Using HIV Surveillance Data to Support the HIV Care Continuum. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giordano TP, Hartman C, Gifford AL, Backus LI, Morgan RO. Predictors of retention in HIV care among a national cohort of US veterans. HIV Clin Trials 2009; 10:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.