Abstract

Alcanivorax borkumensis is an ubiquitous model organism for hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria, which dominates polluted surface waters. Its negligible presence in oil-contaminated deep waters (as observed during the Deepwater Horizon accident) raises the hypothesis that it may lack adaptive mechanisms to hydrostatic pressure (HP). The type strain SK2 was tested under 0.1, 5 and 10 MPa (corresponding to surface water, 500 and 1000 m depth, respectively). While 5 MPa essentially inactivated SK2, further increase to 10 MPa triggered some resistance mechanism, as indicated by higher total and intact cell numbers. Under 10 MPa, SK2 upregulated the synthetic pathway of the osmolyte ectoine, whose concentration increased from 0.45 to 4.71 fmoles cell−1. Central biosynthetic pathways such as cell replication, glyoxylate and Krebs cycles, amino acids metabolism and fatty acids biosynthesis, but not β-oxidation, were upregulated or unaffected at 10 MPa, although total cell number was remarkably lower with respect to 0.1 MPa. Concomitantly, expression of more than 50% of SK2 genes was downregulated, including genes related to ATP generation, respiration and protein translation. Thus, A. borkumensis lacks proper adaptation to HP but activates resistance mechanisms. These consist in poorly efficient biosynthetic rather than energy-yielding degradation-related pathways, and suggest that HP does represent a major driver for its distribution at deep-sea.

Enhanced microbial hydrocarbons degradation represents one of the most important remediation strategies for marine petroleum contamination. While the use of booms with skimmers and dispersants may account for recovering or dissolving the largest fraction of the spilled oil1, the last, fine hydrocarbons removal step relies on bacterial degradation. Soon after oil is spilled, microbial community structures on surface waters are largely modified2 and members of the genus Alcanivorax frequently dominate such bacterial blooms accounting for more than 80% of the total bacterial population3,4,5. Such a prominent role in petroleum-affected environments is due to some critical features possessed by Alcanivorax, including the ability to efficiently use branched-chain alkanes6 and the capacity to enhance the bioavailability of hydrophobic compounds in water. Further, in hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria utilization of carbon sources alternative to oil is limited to few metabolic intermediates, such as acetate and pyruvate, making them very selective towards hydrocarbons6,7. The Alcanivorax genus was initially described by Yakimov and co-workers in 1998, who isolated A. borkumensis SK2 and proposed it as the type strain. It was later recognized that this ubiquitous genus, and A. borkumensis in particular, dominates oil-contaminated surface marine waters all over the world8,9, background to why A. borkumensis SK2 is being today adopted as a model organism to investigate hydrocarbon degradation pathways in marine environments10.

A limitation to oil bioremediation is the tendency of oil to create tar balls and droplets, which eventually sink to the seafloor together with bacterial biomass belonging to the surface11. Overwhelming oil release to the environment enhances also marine snow formation12, which has been recognized as the main driver for seafloor contamination in the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) spill in April 201013. These phenomena postulate that microbial oil degraders at the sea surface will eventually deal with increased hydrostatic pressure (HP) typical of the deep sea. Oil in the deep sea also results from the release by natural seeps or following the use of dispersants14, by adsorption to heavier particulate or non-miscible components, or due to problems encountered at deep-sea drilling sites as in the case of the DWH spill15. Studies on the fate of the deep oil plume occurring after the DWH spill indicated that bacteria other than Alcanivorax were mainly enriched during hydrocarbon biodegradation16,17,18,19,20,21. Several environmental factors such as low temperature or lack of nutrients were proposed as conditional for the enrichment of Alkanivorax in the deep water oil plume22, but supporting evidence was not supplied20. On the contrary, to our knowledge the HP occurring at the depth of the DWH spill has been neglected as a possible factor to explain the low abundance of Alcanivorax detected after the oil spill. Considering the ubiquity of Alcanivorax in polluted surface marine waters, including those in the Gulf of Mexico after the DWH oil spill23, the low frequency of Alcanivorax in the DWH oil plume in the deep water column raises the hypothesis that this organism may not effectively respond to HP. Our hypothesis is that mild HP (up to 10 MPa, equivalent to1 km in the marine water column, approximately the depth of the DWH oil spill) may be sufficiently stressing to exert an impact on A. borkumensis metabolism and potentially impair its remarkable oil-bioremediation capacity. In the present study, A. borkumensis SK2 physiological response to 0.1, 5 and 10 MPa grown on the alkane n-dodecane was compared, and integrated with information derived from the analysis of the transcriptome at 0.1 and 10 MPa.

Results

Growth yields under atmospheric and increased HP in A. borkumensis SK2

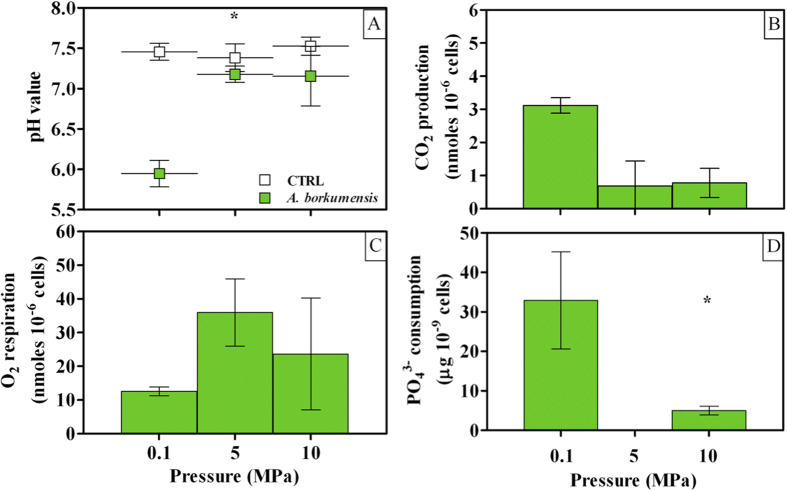

Cell replication and metabolism in A. borkumensis cultures were examined under atmospheric (0.1 MPa) and mild (5 or 10 MPa) HP. Change in OD610 was substantial under atmospheric pressure, but dramatically decreased under 5 and 10 MPa (P < 0.05; Fig. 1A) as also observed for total (Fig. 1B) and intact cell number (Fig. 1C). However, both these latter values were significantly higher under 10 MPa than 5 MPa (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B,C) indicating that some pressure-resistance mechanism was activated over the stressing HP of 5 MPa. Dodecane concentration was evaluated by analyzing its solubilized fraction in the culture broth at the end of the incubation (Fig. S1). This analysis aimed at understanding whether experimental conditions limited the access to the supplied carbon source, provided that dodecane solubility in saline waters is lower than 2 μg L−1 24. Notwithstanding the very different cell number (Fig. 1B), comparable values were found in cultures incubated under 0.1 and 10 MPa (Fig. S1), suggesting that access to dodecane was not a limiting factor. The highest values of solubilized dodecane were observed under 5 MPa (Fig. S1) despite cells did not grow (Fig. 1B). This may be explained with an increasingly impaired metabolism in SK2 during incubation under HP, where solubilized dodecane is eventually not taken up. Full understanding of this mechanism requires further experimental evidence, the outcome of which would be out of the scope of the present investigation.

Figure 1. Culture growth of A. borkumensis SK2 cells under different HPs (0.1, 5 and 10 MPa).

(A) Net optical density increase; (B) Net cell number increase; (C) final cell integrity. Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05), that is: in (A), mean average value at 0.1 MPa is higher than at 5 and 10 MPa; in (B), mean average values at 10 MPa are higher than at 5 MPa.

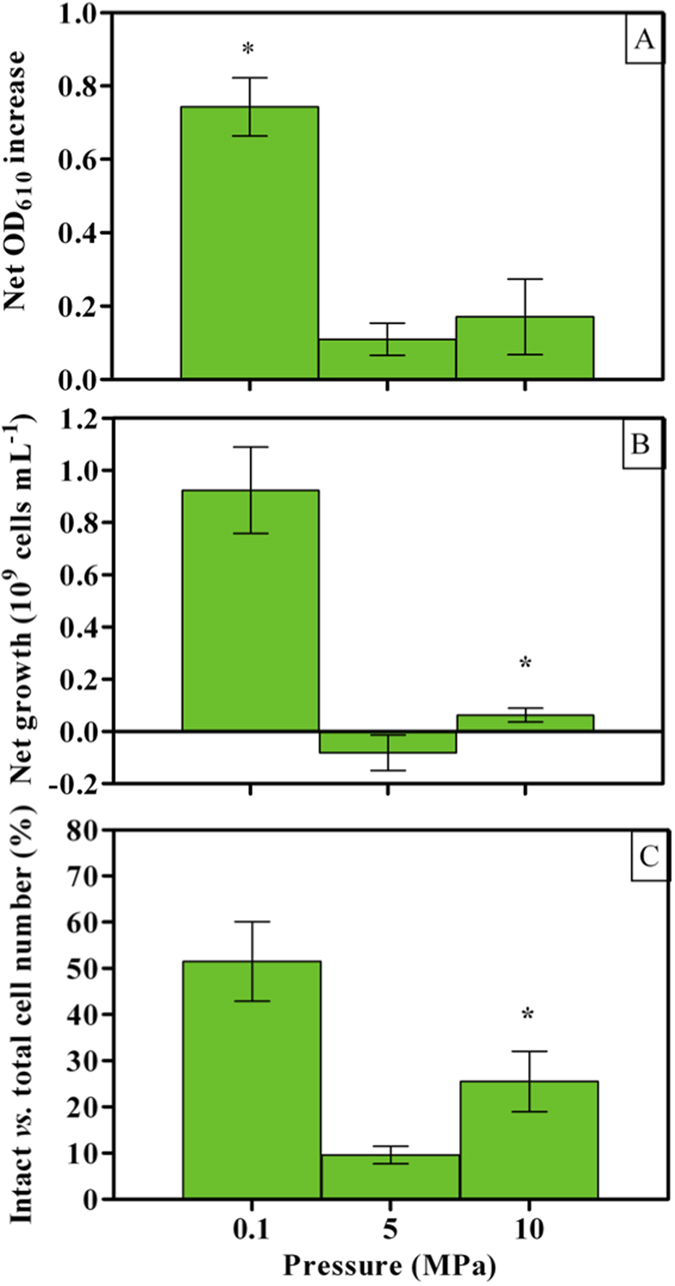

Since dodecane was the sole carbon source supplied to A. borkumensis cells, its degradation could be estimated by following pH decrease and measuring CO2 production with respect to sterile controls. Sustained medium acidification was detected under 0.1 MPa (Fig. 2A) in agreement with a higher OD610 and cell number (Fig. 1A,B, respectively), while little difference in pH was observed under 5 and 10 MPa as compared to sterile controls (Fig. 2A). Variations in pH were mirrored by CO2 production, as the latter significantly decreased under mild HP to low, comparable values at 5 and 10 MPa (P > 0.05, Fig. 2B). Conversely, respiration capacity was generally enhanced by increased HP (Fig. 2C). The lack of a linear relation between CO2 production (Fig. 2B) and O2 respiration (Fig. 2C) when comparing atmospheric and mild HP may be considered as an indication of the shift in cell metabolism under increased HP. PO43− uptake was completely inhibited when increasing HP to 5 MPa, although some activity was restored with further HP increase to 10 MPa (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Cell metabolism in A. borkumensis SK2 cells grown under different HPs (0.1, 5 and 10 MPa).

(A) pH decrease with respect to sterile controls (keys reported in the graph); (B) CO2 production per cell; (C) O2 respiration per cell; (D) uptake of PO43−. Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05), that is: in (A), mean average value at 0.1 MPa is lower than at 5 and 10 MPa; (B), mean average value at 0.1 MPa is higher than at 10 MPa.

As a whole, a mild HP increase to 5 MPa was lethal for A. borkumensis SK2 while doubling such a HP re-established some cell replication and improved cell integrity and activity, indicating that some pressure-resistance mechanism was triggered. To ascertain this hypothesis the transcriptomic response of cells grown under 0.1 and 10 MPa was compared.

Transcriptomic response in A. borkumensis SK2 cells under 0.1 and 10 MPa

Application of 10 MPa HP resulted into a reduced expression of the majority of the genes (56%, 1242/2202), while only a minor fraction was upregulated (16%, 354/2202) and the rest remained unaffected (28%, 606/2202). Increased expression involved various clusters of orthologous genes (COG), the most represented of which were protein translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, amino acid and coenzyme metabolism, energy production and transcription (Fig. S2). Several genes that are not presently categorized in any COG were also upregulated (Fig. S2).

Fatty acids and alkane metabolism

Genes related to fatty acids metabolism were generally upregulated or showed the same expression level at 10 MPa as at ambient pressure (6/11, Table 1), and in particular enzymes related to alkanes activation (such as cytochrome P450 and the alkane 1 mono-oxygenase, Table 1). However, biosynthesis of fatty acids rather than β-oxidation appeared to be triggered by HP. In fact, genes related with fatty acids degradation were generally downregulated (6/9, Table 1) while those expressing enzymes linked with fatty acids biosynthesis were more highly expressed or remained unaffected (6/7, Table 1). An alternative pathway to produce energy with fatty acids is the glyoxylate cycle, whose genes were either more highly expressed under HP or remained unaffected (6/7, Table 2). The glyoxylate cycle generates oxalacetate and is strictly connected to several pathways among which the Krebs (or tricarboxylic acid [TCA]) cycle25. In the latter, the large majority of the genes was either upregulated or remained unaffected under HP (18/21, Table 2). Other pathways involved in the production of energy, such as glycolysis-gluconeogenesis and the pentose phosphate pathway, were generally downregulated (data not shown). However, gene expression of the enzymes connecting the TCA cycle to the purine, pyrimidine and histidine metabolism through glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and the pentose phosphate pathway were either upregulated or unaffected (Table S1), suggesting that under HP these pathways may have been served with metabolic intermediates to support the production of nucleotides.

Table 1. Expression of genes related with alkane and fatty acid metabolism in A. borkumensis SK2 under 0.1 and 10 MPa.

| Pathway | Regulation | log2 FC | 10 MPa | 0.1 MPa | Cluster ID | Locus Tag | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acid metabolism | |||||||

| + | 1.89 | 1557.7 | 421.7 | 764 | ABO_0201 | cytochrome P450 family protein | |

| + | 1.78 | 1183.1 | 345.7 | 764 | ABO_2288 | cytochrome P450 | |

| + | 1.70 | 834.6 | 257.1 | 914 | ABO_0203 | FAD-dependent oxidoreductase family protein | |

| + | 1.10 | 867.5 | 405.8 | 407 | ABO_0122 | alkane-1-monooxygenase | |

| = | −0.20 | 37.0 | 42.5 | 169 | ABO_0162 | rubredoxin reductase | |

| = | −0.44 | 159.4 | 215.9 | 1408 | ABO_1231 | alcohol dehydrogenase | |

| − | −0.53 | 43.3 | 62.5 | 1119 | ABO_0117 | alcohol dehydrogenase/ formaldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| − | −0.64 | 106.3 | 166.2 | 30 | ABO_0061 | alcohol dehydrogenase | |

| − | −0.99 | 31.4 | 62.5 | 696 | ABO_2483 | alcohol dehydrogenase | |

| − | −1.54 | 28.1 | 81.7 | 2020 | ABO_0962 | aldehyde dehydrogenase family protein | |

| − | −1.65 | 55.3 | 173.5 | 1325 | ABO_2384 | cytochrome P450 | |

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | |||||||

| + | 0.97 | 190.9 | 97.2 | 1167 | ABO_1071 | fabF; 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase | |

| + | 0.77 | 374.4 | 219.1 | 2166 | ABO_1154 | FabZ; (3R)-hydroxymyristoyl-[acyl carrier protein] dehydratase | |

| + | 0.76 | 264.6 | 156.2 | 299 | ABO_0835 | fabA; 3-hydroxydecanoyl-(acyl carrier protein) dehydratase | |

| + | 0.57 | 136.3 | 91.8 | 49 | ABO_1069 | fabG; 3-oxoacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) reductase | |

| = | 0.12 | 113.6 | 104.5 | 1382 | ABO_0834 | 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase | |

| = | −0.17 | 43.0 | 48.5 | 2093 | ABO_1215 | enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase | |

| − | −3.48 | 87.5 | 979.0 | 1649 | ABO_1713 | 3-ketoacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) reductase | |

| Fatty acid degradation | |||||||

| = | 0.50 | 100.8 | 71.5 | 143 | ABO_1653 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase | |

| = | −0.07 | 104.4 | 109.9 | 1313 | ABO_1652 | multifunctional fatty acid oxidation complex subunit alpha | |

| = | −0.40 | 66.1 | 86.9 | 1467 | ABO_0957 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | |

| - | −0.67 | 59.6 | 94.9 | 660 | ABO_1566 | fatty oxidation complex subunit alpha | |

| − | −0.71 | 83.2 | 135.9 | 644 | ABO_0571 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | |

| − | −1.55 | 30.6 | 89.5 | 1976 | ABO_0253 | acetyl-CoA acyltransferase | |

| − | −1.55 | 19.4 | 56.9 | 689 | ABO_1702 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase middle domain-containing protein | |

| − | −1.70 | 52.0 | 168.7 | 55 | ABO_1772 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | |

| − | −2.57 | 77.6 | 459.3 | 1865 | ABO_1121 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | |

Table 2. Gene expression of glyoxylate and TCA cycle, ATP synthase subunits, cytochromes C and B, and alternative respiration pathways in A. borkumensis SK2 cells grown under 10 MPa as compared to 0.1 MPa.

| Pathway | Regulation | log2 FC | 10 MPa | 0.1 MPa | Cluster ID | Locus Tag | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyoxylate cycle | |||||||

| + | 2.46 | 1080.6 | 196.5 | 1810 | ABO_2741 | isocitrate lyase | |

| + | 1.98 | 224.4 | 56.9 | 1871 | ABO_1201 | bifunctional aconitate hydratase 2/2-methylisocitrate dehydratase | |

| + | 1.69 | 312.3 | 97.0 | 2127 | ABO_1267 | malate synthase G | |

| = | 0.22 | 132.7 | 113.8 | 338 | ABO_1248 | malate dehydrogenase | |

| = | 0.08 | 169.1 | 160.3 | 1864 | ABO_1501 | type II citrate synthase | |

| = | −0.12 | 82.3 | 89.3 | 1152 | ABO_1431 | aconitate hydratase | |

| − | −1.27 | 321.6 | 778.2 | 872 | ABO_0694 | aconitate hydratase | |

| TCA cycle | |||||||

| + | 1.98 | 224.4 | 56.9 | 1871 | ABO_1201 | bifunctional aconitate hydratase 2/2-methylisocitrate dehydratase | |

| + | 1.15 | 186.7 | 84.2 | 1441 | ABO_0296 | isocitrate dehydrogenase | |

| + | 0.92 | 559.4 | 295.7 | 1344 | ABO_1493 | succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit beta | |

| + | 0.79 | 77.5 | 45.0 | 691 | ABO_1540 | fumarate hydratase | |

| + | 0.73 | 75.5 | 45.4 | 2058 | ABO_0275 | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | |

| + | 0.53 | 591.8 | 409.7 | 2110 | ABO_1496 | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component | |

| = | 0.26 | 93.9 | 78.4 | 247 | ABO_1497 | succinate dehydrogenase, iron-sulfur | |

| = | 0.22 | 132.7 | 113.8 | 338 | ABO_1248 | malate dehydrogenase | |

| = | 0.08 | 169.1 | 160.3 | 1864 | ABO_1501 | type II citrate synthase | |

| = | −0.01 | 282.6 | 284.6 | 991 | ABO_1495 | dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase | |

| = | −0.04 | 98.0 | 100.8 | 475 | ABO_1498 | succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit | |

| = | −0.04 | 157.3 | 161.3 | 486 | ABO_1499 | succinate dehydrogenase, hydrophobic membrane anchor protein | |

| = | −0.05 | 307.8 | 318.3 | 1918 | ABO_1492 | succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit alpha | |

| = | −0.08 | 282.6 | 298.4 | 1943 | ABO_1494 | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase lipoamide dehydrogenase component | |

| = | −0.11 | 121.7 | 131.6 | 1539 | ABO_2749 | fumarate hydratase | |

| = | −0.12 | 82.3 | 89.3 | 1152 | ABO_1431 | aconitate hydratase | |

| = | −0.48 | 182.4 | 253.9 | 1044 | ABO_0622 | pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit E1 | |

| = | −0.5 | 110.3 | 156.3 | 1267 | ABO_1282 | isocitrate dehydrogenase | |

| − | −0.56 | 346.8 | 512.4 | 1237 | ABO_1500 | succinate dehydrogenase, cytochrome b556 subunit | |

| − | −0.76 | 162.4 | 275.5 | 128 | ABO_0623 | pyruvate dehydrogenase, E2 component | |

| − | −1.27 | 321.6 | 778.2 | 872 | ABO_0694 | aconitate hydratase | |

| ATP synthase | |||||||

| + | 3.38 | 1345.4 | 129.3 | 506 | ABO_2730 | atpF; ATP synthase F0 subunit B | |

| + | 3.08 | 332.4 | 39.4 | 942 | ABO_2729 | atpH; ATP synthase subunit delta | |

| + | 1.70 | 521.2 | 160.6 | 163 | ABO_2728 | atpA; ATP synthase subunit alpha | |

| + | 1.28 | 304.1 | 125.5 | 485 | ABO_2727 | atpG; ATP synthase subunit gamma | |

| + | 1.07 | 599.1 | 286.3 | 323 | ABO_2732 | atpB; F0F1 ATP synthase subunit A | |

| + | 0.95 | 321.1 | 166.7 | 1566 | ABO_2726 | atpD; F0F1 ATP synthase subunit beta | |

| + | 0.77 | 325.4 | 191.4 | 1581 | ABO_2725 | atpC; ATP synthase subunit epsilon | |

| + | 0.73 | 340.4 | 204.8 | 1637 | ABO_2733 | atpI; ATP synthase subunit I | |

| − | −0.69 | 35.1 | 56.5 | 1610 | ABO_2731 | ATP synthase F0 subunit C | |

| Energy Production (alternative respiration) | |||||||

| + | 1.10 | 196.8 | 91.9 | 2010 | ABO_1032 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit A | |

| + | 1.02 | 393.5 | 194.5 | 359 | ABO_1034 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit C | |

| = | 0.19 | 205.1 | 179.2 | 337 | ABO_1037 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit F | |

| = | −0.08 | 149.1 | 157.8 | 1158 | ABO_1033 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit B | |

| = | −0.23 | 92.8 | 108.7 | 615 | ABO_1035 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit D | |

| − | −2.11 | 46.1 | 198.7 | 781 | ABO_1036 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit E | |

| Cytochrome C reductase | |||||||

| + | 1.45 | 241.3 | 88.1 | 1648 | ABO_0578 | ubiquinol–cytochrome c reductase, iron-sulfur subunit | |

| + | 1.17 | 437.0 | 194.1 | 1172 | ABO_0580 | ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase cytochrome c1 subunit | |

| = | 0.00 | 267.1 | 268.0 | 285 | ABO_0579 | ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase cytochrome subunit B | |

| Cytochrome C oxidase | |||||||

| + | 0.89 | 201.5 | 108.5 | 1142 | ABO_1900 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit II, CoxB | |

| = | 0.01 | 201.0 | 199.7 | 947 | ABO_1897 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit III, CoxC | |

| = | −0.07 | 120.4 | 126.5 | 1852 | ABO_1899 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit I, CoxA | |

| − | −0.58 | 99.0 | 148.0 | 1941 | ABO_1905 | cytochrome c oxidase assembly protein, CtaA | |

| − | −1.04 | 106.6 | 219.2 | 1533 | ABO_1898 | cytochrome c oxidase assembly protein, CtaG | |

| − | −1.61 | 57.2 | 174.9 | 447 | ABO_2036 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit I, CyoB | |

| − | −1.86 | 44.6 | 161.5 | 1213 | ABO_2037 | cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase subunit II, CyoA | |

| − | −2.13 | 19.0 | 83.1 | 955 | ABO_2035 | cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase subunit III, CyoC | |

| − | −2.41 | 90.6 | 480.1 | 398 | ABO_2034 | cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase, protein CyoD | |

| Other Cytochromes C and B | |||||||

| + | 3.18 | 2551.5 | 280.9 | 1326 | ABO_2651 | cytochrome c-type protein | |

| + | 2.13 | 173.7 | 39.7 | 288 | ABO_2540 | cytochrome c5 | |

| + | 1.65 | 374.4 | 119.4 | 1440 | ABO_2650 | cytochrome c4 | |

| + | 0.57 | 80.7 | 54.4 | 864 | ABO_2539 | cytochrome c5 | |

| = | −0.39 | 72.1 | 94.3 | 611 | ABO_0838 | cytochrome c biogenesis protein, CcmH | |

| − | −1.02 | 58.4 | 118.4 | 1697 | ABO_0839 | cytochrome c-type biogenesis protein | |

| − | −1.04 | 54.6 | 112.1 | 386 | ABO_0874 | cytochrome c-type biogenesis protein, CcmE | |

| − | −1.75 | 24.7 | 83.0 | 2031 | ABO_1185 | cytochrome c family protein | |

| − | −1.83 | 30.0 | 106.6 | 421 | ABO_0836 | cytochrome c-type biogenesis protein CcmF | |

| − | −2.59 | 109.9 | 663.6 | 1794 | ABO_0099 | cytochrome B651 | |

Amino acids and derivate compounds

Several pathways related to the synthesis of amino acids were upregulated. Genes involved in the metabolism of glycine, serine and threonine (15/16, Table 3), biosynthesis of L-leucine (10/10, Table 3), and biosynthesis of valine, leucine and isoleucine (11/13, Table 3) were either upregulated or remained unaffected, together with the majority of those supporting cell division (6/11, Table 3). As a notable exception, the whole pathway leading to the production of the nitrogen-based osmolyte ectoine was upregulated (Table 4). Analysis of the different biomasses grown at 0.1 and 10 MPa confirmed a remarkable 10-fold increase in the amount of ectoine produced per cell in cultures grown under HP (from 0.45 to 4.71 fmoles cell−1, respectively; P < 0.05; Fig. 3).

Table 3. Gene expression in amino acid and cell division pathways in A. borkumensis SK2 cells grown under 10 MPa as compared to 0.1 MPa.

| Pathway | Regulation | log2 FC | 10 MPa | 0.1 MPa | Cluster ID | Locus Tag | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine, Serine and Threonine Metabolism | |||||||

| + | 1.97 | 337.3 | 86.4 | 1005 | ABO_2594 | glycine cleavage system T protein | |

| + | 1.37 | 590.4 | 228.6 | 1355 | ABO_0807 | threonine synthase | |

| + | 1.22 | 125.4 | 53.9 | 222 | ABO_2176 | serine hydroxymethyltransferase | |

| + | 0.79 | 160.3 | 93.0 | 1666 | ABO_2593 | glycine cleavage system H protein | |

| + | 0.76 | 136.6 | 80.6 | 709 | ABO_2442 | phosphoserine phosphatase | |

| + | 0.71 | 135.0 | 82.4 | 1054 | ABO_0806 | homoserine dehydrogenase | |

| + | 0.51 | 147.1 | 103.5 | 360 | ABO_1769 | phosphoglycerate mutase | |

| = | 0.46 | 40.7 | 29.5 | 136 | ABO_2592 | glycine dehydrogenase subunit 1 | |

| = | 0.45 | 127.7 | 93.7 | 223 | ABO_0688 | TRAP dicarboxylate transporter | |

| = | 0.3 | 24.3 | 19.8 | 1494 | ABO_2591 | glycine dehydrogenase subunit 2 | |

| = | 0.18 | 92.3 | 81.4 | 149 | ABO_1436 | phosphoserine phosphatase | |

| = | -0.02 | 169.2 | 171.2 | 1271 | ABO_0042 | phosphotransferase family protein | |

| = | −0.08 | 282.6 | 298.4 | 1943 | ABO_1494 | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase lipoamide | |

| = | −0.23 | 89.2 | 104.5 | 490 | ABO_2605 | threonine dehydratase, biosynthetic | |

| = | −0.23 | 89.2 | 104.5 | 490 | ABO_2605 | threonine dehydratase, biosynthetic | |

| − | −0.61 | 76.1 | 116.1 | 1056 | ABO_1750 | phosphoserine aminotransferase | |

| L-leucine Biosynthesis | |||||||

| + | 4.91 | 3676.8 | 122.4 | 510 | ABO_2437 | ilvE; branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase | |

| + | 2.45 | 159.5 | 29.2 | 1318 | ABO_2301 | ilvE; branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase | |

| + | 1.53 | 833.4 | 289.3 | 2145 | ABO_1470 | leuC; isopropylmalate isomerase large subunit | |

| + | 1.00 | 674.3 | 337.8 | 559 | ABO_0482 | ilvH; acetolactate synthase 3 regulatory subunit | |

| + | 0.81 | 122.0 | 69.5 | 1715 | ABO_0481 | ilvB-1; acetolactate synthase 3 catalytic subunit | |

| = | 0.39 | 215.5 | 164.5 | 595 | ABO_0485 | ketol-acid reductoisomerase | |

| = | 0.27 | 43.4 | 36.0 | 394 | ABO_2312 | dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | |

| = | 0.23 | 272.9 | 232.5 | 339 | ABO_1467 | 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase | |

| = | 0.20 | 436.2 | 378.6 | 1492 | ABO_1469 | 3-isopropylmalate dehydratase small subunit | |

| = | 0.11 | 86.9 | 80.3 | 1428 | ABO_0638 | 2-isopropylmalate synthase | |

| Valine, Leucine and Isoleucine Biosynthesis | |||||||

| + | 4.91 | 3676.8 | 122.4 | 510 | ABO_2437 | 2-isopropylmalate synthase | |

| + | 2.45 | 159.5 | 29.2 | 1318 | ABO_2301 | branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase | |

| + | 1.53 | 833.4 | 289.3 | 2145 | ABO_1470 | isopropylmalate isomerase large subunit | |

| + | 1 | 674.3 | 337.8 | 559 | ABO_0482 | acetolactate synthase 3 regulatory subunit | |

| + | 0.81 | 122.0 | 69.6 | 1715 | ABO_0481 | acetolactate synthase 3 catalytic subunit | |

| = | 0.39 | 215.5 | 164.5 | 595 | ABO_0485 | ketol-acid reductoisomerase | |

| = | 0.27 | 43.4 | 36.0 | 394 | ABO_2312 | dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | |

| = | 0.23 | 272.9 | 232.5 | 339 | ABO_1467 | 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase | |

| = | 0.2 | 436.2 | 378.6 | 1492 | ABO_1469 | 3-isopropylmalate dehydratase small subunit | |

| = | 0.11 | 86.9 | 80.3 | 1428 | ABO_0638 | 2-isopropylmalate synthase | |

| = | −0.23 | 89.2 | 104.5 | 490 | ABO_2605 | threonine dehydratase, biosynthetic | |

| − | −0.53 | 62.3 | 89.9 | 1571 | ABO_0180 | dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | |

| − | −0.78 | 46.8 | 80.4 | 2136 | ABO_0704 | acetolactate synthase | |

| Cell division | |||||||

| + | 1.44 | 461.9 | 170.6 | 1439 | ABO_0591 | cell division protein FtsL | |

| + | 0.78 | 287.3 | 166.8 | 1367 | ABO_0948 | cell division protein ZipA | |

| + | 0.75 | 69.9 | 41.5 | 2142 | ABO_2566 | cell division protein FtsY | |

| = | 0.36 | 165.4 | 128.5 | 778 | ABO_1290 | cell division protein FtsK | |

| = | −0.07 | 843.5 | 882.6 | 1176 | ABO_0322 | cell division protein FtsH | |

| = | −0.07 | 65.9 | 69.4 | 2138 | ABO_0603 | cell division protein FtsZ | |

| − | −0.86 | 15.1 | 27.5 | 1319 | ABO_2568 | cell division protein FtsX | |

| − | −0.91 | 52.6 | 98.8 | 1374 | ABO_0601 | cell division protein FtsQ | |

| − | −0.94 | 88.6 | 169.5 | 539 | ABO_0597 | cell division protein FtsW | |

| − | −1.05 | 13.4 | 27.8 | 1874 | ABO_2567 | cell division ATP-binding protein FtsE | |

| − | −1.66 | 34.0 | 107.6 | 449 | ABO_0602 | cell division protein FtsA | |

Table 4. Gene expression in the ectoine biosynthesis pathway in A. borkumensis SK2 cells grown under 10 MPa as compared to 0.1 MPa.

| Pathway | Regulation | log2 FC | 10 MPa | 0.1 MPa | Cluster ID | Locus Tag | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ectoine biosynthesis | |||||||

| + | 2.90 | 704.4 | 94.5 | 661 | ABO_2150 | ectA; DABA acetyltransferase | |

| + | 2.26 | 1697.1 | 355.1 | 471 | ABO_2152 | ectC; L-ectoine synthase | |

| + | 2.07 | 538.8 | 128.4 | 1377 | ABO_1797 | lysC; aspartokinase | |

| + | 1.90 | 321.4 | 86.1 | 1212 | ABO_2151 | ectB; diaminobutyrate–2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase | |

| + | 0.76 | 553.4 | 325.7 | 628 | ABO_1466 | asd-2; aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | |

Figure 3. Accumulation of intracellular ectoine per cell in A. borkumensis SK2 grown under different HPs (0.1 and 10 MPa).

Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Asterisk indicates that values obtained under 10 MPa were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those observed under 0.1 MPa.

Respiration and ATP generation

Expression of almost all the genes involved in the formation of the ATP synthase complex was upregulated (8/9, Table 2), indicating that HP may have deeply affected such multimeric enzyme and energy production. Genes involved in respiration were also highly impacted by HP. The large majority of the genes encoding for cytochrome c oxidases (6/9, Table 2) and cytochrome b (1/1, Table 2) were downregulated, the latter being the most downregulated gene involved in respiration. On the contrary, cytochrome c reductases were either upregulated or remained unaffected (3/3, Table 2). Furthermore, the majority of the genes expressing subunits of the Na+-translocating NADH-quinone reductase were either upregulated or unaffected (5/6, Table 2), supporting the hypothesis that the microbial respiration chain under HP may follow different pathways with respect to that occurring at ambient pressure.

Transcription and translation

The transcriptional machinery appeared to be only slightly impacted by HP. While genes coding for transcriptional regulators generally showed a lower expression level (29/46, Table S2), 5/8 genes coding for elongators, activators and termination factors were upregulated (Table S2). Similarly, genes involved in DNA replication and repair were only partially expressed at a higher level under HP (1/10 and 2/9, respectively, Table S3). On the contrary, protein translation was highly affected, as several translation (4/6) and elongation factors (3/3) were upregulated (Table S4). All RNA polymerase genes (4/4, Table S4) were upregulated, while the tRNA regulator pseudouridine synthase was either upregulated or unaffected (3/3, Table S4). Notably, genes encoding for ribosomal proteins were largely upregulated (45/53, Table S5), suggesting that mild HP deeply affected this multicomponent protein complex. On the contrary, some of the typical HP-responsive pool of genes (such as sigma factors, chaperonins and outer membrane proteins) were marginally affected by HP increase (Table S6).

Discussion

Worldwide, microbial communities developing on oil-contaminated surface waters were dominated by A. borkumensis, which grows rapidly right after oil spills10,26,27. In deep-sea waters A. borkumensis, and in general the genus Alcanivorax, is much less common according to studies following the actual enriched microbial community developed after the DWH oil spill at depths of 1000–1300 m16,17,18,19,20. Alcanivorax signatures in the DWH case studies were reported in sediments at a low relative abundance (only few tens of the Oceanospirillales sequences that represented just 1.4–1.7% of total bacterial sequences) and it was concluded that they did not correlate with the hydrocarbon levels associated with the sample28. Gutierrez and co-workers identified A. borkumensis SK2-like sequences in deep waters from the DWH oil spill20. However, according to sequence abundance they considered Alcanivorax contribution to oil degradation rather negligible20. They also obtained Alcanivorax isolates with enrichment experiments performed on decompressed samples, thereby eliminating a specific environmental factor of the DWH plume20. This methodology has been typically applied to the known Alcanivorax species isolated from deep-sea environments29,30,31. Our findings indicate that A. borkumensis SK2 might not be enriched under the mild HP of the DWH deep waters, suggesting that the lack of such a selection factor would restore the capacity of Alcanivorax to grow. The role of HP on A. borkumensis physiological and molecular response has never been investigated, leaving a knowledge gap about its role, deep-sea distribution and activity. Our experiments on strain SK2 indicate that it is a piezosensitive microbe and that mild HP remarkably affects A. borkumensis growth and physiology, explaining its low abundance in the sea water column. While temperature may also play a role in determining such a low abundance in deep-sea environments, it must be noted that strain SK2 does grow with temperatures as low as 4 °C7.

The stoichiometric mineralization of dodecane would yield a maximum CO2:O2 molar ratio of 0.649, as 12 moles of CO2 would be generated from 1 mole of dodecane using 18.5 moles of O2 (Eq. 1).

|

As part of the supplied dodecane may be used to build up microbial biomass through some metabolic intermediates, Eq. 1 overestimates the effective mineralization rate and it rather represents the upper limit for dodecane degradation by the cells. Growth yields were high under surface-water-resembling conditions (0.1 MPa; Fig. 1A,B). Coherently, dodecane biodegradation rates were about 1/3 of the stoichiometric conversion ratio (0.248 vs. 0.649, Eq. 1). Application of a HP equivalent to 5 MPa was lethal, as it essentially inactivated SK2: final cell number was lower than what initially inoculated, decreasing to almost undetectable values (58 ± 47*106 cells mL−1) with more than 90% of such surviving cells being damaged (Fig. 1C). Uptake of PO43− was completely inhibited (Fig. 2D), while O2 respiration increased (Fig. 2C) and CO2 production dropped (Fig. 2B), resulting in a CO2:O2 molar ratio of 0.019. The lack of a significant difference (P > 0.05) in pH value between sterile controls and cells incubated under 5 MPa (Fig. 2A) is a good indication of the effects of HP on the metabolic potential of A. borkumensis SK2. However, application of HPs twice as high as this lethal one triggered some HP-resistance mechanism. While the bioremediation potential remained as low as that observed at 5 MPa (Fig. 2A), under 10 MPa some culture growth was re-established (Fig. 1B), cell integrity improved (Fig. 1C), CO2:O2 molar ratio slightly increased (0.033) and uptake of some critical nutrients restored (Fig. 2D).

HP resistance conferred by the piezolyte ectoine

Enhanced bacterial fitness upon further HP increase to 10 MPa was consistent with the synthesis of the osmolyte ectoine (Table 4 and Fig. 3). Several organic and inorganic solutes accumulate intracellularly under osmotic and thermal stress to maintain turgor pressure, cell hydration or stabilize macromolecular structures, while little is known about solutes implicated in counteracting the destabilizing effects exerted by HP32. Ectoine is a very well known nitrogen-based organic osmolyte33 produced in response to an increased salinity33,34, and has been found in genera that include several piezophilic species such as Vibrio and Photobacterium35. However, previous studies failed to observe accumulation of ectoine under increased HP in both piezophilic36 and piezosensitive bacteria37. Hence, the present study is the first describing ectoine as a piezolyte, a class that includes solutes accumulated under both osmotic and HP. The exact protective mechanisms exerted by ectoine are not clear as well as the triggering effect leading to its enhanced production. In principle, HP does not result into a pressure difference across the membrane rather in destabilization of macromolecules32. Observation that other piezosensitive bacteria such as A. dieselolei KS 293 do not upregulate synthetic pathways under 10 MPa38 leads to two hypothesis: 1) either ectoine synthesis under HP is a peculiar response of A. borkumensis cells or, more likely, 2) critical thresholds for membrane integrity exist, as in A. dieselolei KS 293 intact cell number was almost unaffected at 0.1 and 10 MPa (about 70%38). However, non-linear responses between HP and cell integrity have already been reported39, therefore the possibility that other mechanisms may (co-)regulate ectoine production should be thoroughly investigated.

Provided that the averaged bacterial cell dry weight (CDW) is 10−12 g40,41, estimates of the highest ectoine accumulation capacity in A. borkumensis SK2 cells at 10 MPa would yield 0.59 gectoine g−1CDW. This value is higher than what reported with some of the most productive strains in the literature (Halomonas salina42, Brevibacter linens43 and B. epidermis44 yielding 0.35, 0.21 and 0.16 gectoine g−1CDW, respectively), cultivated at ambient pressure under increased salinity (between 0.5 and 1 M NaCl42,43,44 vs. 0.4 M of the present study). However, owe to SK2 limited growth yields at 10 MPa (Fig. 1B), ectoine concentration in the culture broth was rather low (0.12 gectoine L−1), while much higher productivities could be achieved in H. salina42 and B. epidermis44 (6.9 and 8 gectoine L−1). The apparently counter-productive investment in the energy-intensive43 de novo ectoine synthesis under the stressing conditions of 10 MPa (Figs 1C and 2D) may be considered as a good indication of SK2 limited capability to adapt to HP.

Alkane and fatty acids metabolism

Genome expression was largely suppressed by exposure to 10 MPa, confirming a general deleterious effect on SK2 metabolism and its piezosensitive nature. However, unaffected and upregulated pathways described an integrated response aimed at supporting cell replication. Genes involved in alkanes activation45 were upregulated under HP (Table 1). Introduction of an oxygen atom into saturated hydrocarbons may proceed through a terminal or subterminal pathway, which can coexist within the same microorganism46. In the present study this would result into the generation of dodecanoyl-CoA (terminal oxidation) and/or decanoyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA (subterminal oxidation). While the exact mechanisms of alkane activation and the generated metabolic intermediate remain unknown, it appears that once such fatty acids were introduced into cell metabolism their elongation rather than their degradation was preferred under 10 MPa (Table 1). None of the genes associated with β-oxidation was upregulated (0/9, Table 1), contrary to what observed with fatty acids biosynthesis (4/7, Table 1). Reduced expression of genes related with β-oxidation under HP does not exclude that this pathway may have been active to some extent. However, A. borkumensis SK2 is also known to be able to withdrawn oxidized n-alkanes from the degradation pathway and incorporate them as their corresponding fatty acids in the membrane47, a mechanism already observed in other hydrocarbon-degrading microbes (e.g., Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus48 and Rhodococcus erythropolis49). The main fatty acid components in A. borkumensis membrane range between C14 and C18 7, therefore their elongation would be needed prior to incorporation. Strain SK2 does possess the capacity to elongate n-alkane-oxidized fatty acids by addition of C2 units47. Membranes represent 10% of bacterial biomass47, and using this pathway would avoid synthesizing fatty acids de novo, thus representing an effective energy-saving strategy under stress conditions.

Nonetheless, alternative pathways related with energy generation also making use of fatty acids were upregulated, such as the glyoxylate and TCA cycle. These pathways share several genes and metabolic intermediates and were both found to be active under HP (Table 2). The glyoxylate cycle is the main biosynthetic route starting from fatty acids25 serving several other pathways such as glycine synthesis starting from glyoxylate itself 50. Enzymes related with glycine synthesis are interconnected with serine and threonine metabolism51, the synthesis of all of the three being enhanced under HP (Table 3). As such, upregulated genes involved in cell division (Table 3) would be potentially served with energy (glyoxylate and TCA cycles [Table 2]) and some of the major building blocks to produce bacterial biomass (fatty acids through reverse β-oxidation [Table 1] and amino acids [Table 3]). Further, the biotin synthesis pathway was found to be active under HP (Table S7). Generation of this cofactor takes advantage of metabolic intermediates derived from fatty acids biosynthesis52, which was enhanced under HP (Table 1).

Notwithstanding the enhanced expression under mild HP of genes related to biosynthetic pathways, the final number of cells at 10 MPa was markedly lower than that measured at 0.1 MPa (Fig. 1B). This may indicate that the actual activity of the related enzymes may have been compromised under HP, or that other key pathways supporting cell replication were critically impaired. This could be the case of ATP generation and protein translation.

ATP generation and alternative respiration pathways

Mild HP may have deeply affected ATP generation in strain SK2, as almost all ATP synthase subunits were upregulated under 10 MPa (Table 2). Energetic hurdles due to extreme, stressing conditions are known to impact ATP intracellular balance at high pH53 and salinity54, with acid55 or HP stress (about 40 MPa56). Although increased cell damaging (Fig. 1C) may have contributed significantly to raise the energy requirement for cell maintenance, PO43− uptake per cell did not increase between 0.1 and 10 MPa (Fig. 2). In this perspective, enhanced biosynthesis rather than degradation of fatty acids (Table 1) may be part of an energy-saving strategy, where incorporating n-alkane-oxidized fatty acids47 to build up cell components would be more convenient than degrading dodecanoyl- or decanoyl-CoA to di- or tri-carboxylic acids and synthesize them again through the glyoxylate and TCA cycle, especially when ATP generation is impaired. As concerns respiration, mild HP shifted cytochrome c species from oxidases to reductases (Table 2) and downregulated the expression of cytochrome b. Accordingly, genes related with several Na+-translocating quinone reductase subunits were more highly expressed (Table 2). A similar response to mild HP in oil-degrading Alcanivorax species was previously observed35. In agreement, the present data support the hypothesis that mild HP (10 MPa) could induce alternative respiration pathways as those proposed in Shewanella benthica under high HP (60 MPa57,58). As it stands, the increased HP impact on A. borkumensis cells (Fig. 1B,C) as compared to A. dieselolei35 resulted into a larger and higher level of expression of genes belonging to these alternative respiration pathways and ATP generation (Table 2).

DNA transcription, synthesis and repair, and protein translation

DNA integrity and synthesis was not compromised by mild HP (Table S3), while several transcriptional regulators, elongators and termination factors were upregulated (Table S2), likely serving cell replication purposes. Concerning protein translation, this is one of the most HP-sensitive processes. Aminoacyl-tRNA binding to ribosomes determines a conformational change in the latter that leads to an increase in volume59. As processes determining a volume increase are not favored under HP60, protein synthesis efficiency and accuracy is slowed down or impaired by high HP (as tested between 55 to 400 MPa61,62,63,64,65). Expression of almost all ribosome subunits was upregulated under 10 MPa (Table S5) together with translation, elongation and tRNA modifying factors such as the pseudouridine synthase (Table S4). These results are consistent with the response observed with other hydrocarbonoclastic piezosensitive bacteria subjected to 10 MPa35, indicating that protein synthesis is highly impacted already under mild HP. Maintenance of functional multicomponent proteins and organelles such as ribosomes32 may play a major role in the development of microbial community structures with enhanced bioremediation potential.

Materials and Methods

Strain, culture media and growth conditions

Alcanivorax borkumensis SK2 was kindly provided by Prof. Fernando Rojo (CSIC, Spain), and cultivated axenically in static glass bottles of 250 mL (operating volume 100 mL), using ONR7a medium66, initial pH 7.6, for 4 to 7 days at 20 °C. Cultures were provided with 1% (v:v) n-dodecane (Sigma Aldrich, Belgium) as sole carbon source (equivalent to about 7.5 g L−1) in order to imitate the conditions of an oil spill (high C/N ratio) as previously suggested with this strain39.

Mild HP experiments

Early stationary phase cells were collected by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C (Sorval RC5c PLUS, Beckman, Suarlée, Belgium) and resuspended in fresh ONR7a medium at an initial optical density (OD610) of 0.100 ± 0.005, corresponding to 140 ± 30 × 106 cells mL−1. Then, 3.5 mL of culture suspension was transferred into sterile 10 mL syringes and n-dodecane (C12) 1% (v:v) supplied as the sole carbon source. Gas phase (equal to 6.5 mL) was constituted of air, which provided O2 to the cells during the subsequent incubation. Syringes were closed using a sterile three-way valve, and placed in a 1L T316 stainless steel high-pressure reactor (HPR) (Parr, USA). The reactor was filled with deionized water and HP was increased up to 5 or 10 MPa by pumping water with a high-pressure pump (HPLC pump series III, SSI, USA). Pressure was transmitted to the cultures through the piston of the syringe. Experiments at atmospheric pressure were run adjacent to the HPR. Control experiments were constituted by sterile syringes supplied only with sterile non-inoculated medium. Reactors were incubated in a temperature-controlled room at 20 °C for 4 days reaching the stationary phase. At the end of the experiments, pressure was gently released and syringes set aside for 30 min before running biochemical analyses, unless otherwise specified.

Cell counts and related analyses

Optical density was measured at 610 nm (OD610) with a spectrophotometer (Isis 9000, Dr Lange, Germany). Pressure-induced cell membrane damaged analysis and total cell count was adapted after67 using flow cytometry: SYBR® Green I and Propidium Iodide were used in combination to discriminate cells with intact and damaged cytoplasmic membranes using a protocol previously described68.

Chemical analyses

O2 respiration and CO2 production rates were assessed by comparing the headspace biogas composition of syringes inoculated with strain SK2 cells and sterile controls. Gas-phase was analyzed with a Compact GC (Global Analyser Solutions, Breda, The Netherlands), equipped with a Molsieve 5A pre-column and two channels. In channel 1, a Porabond column detected CH4, O2, H2 and N2. In channel 2, a Rt-Q-bond pre-column and column detected CO2, N2O and H2S. Biogas concentrations were determined with a thermal conductivity detector. pH was measured using a pH meter (Herisau, Metrohm, Switzerland). Phosphate was quantified with a Compact Ion Chromatograph (Herisau, Metrohm, Switzerland) equipped with a conductivity detector. Dodecane concentration was assessed using a GC equipped with a flame ionized detector (FID) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) and a HP-5 capillary column (30 m; 0.25 mm), set for an isothermal run at 100 °C for 5 min. The injector (splitless mode) was set at 270 °C, while the FID was kept at 320 °C; the carrier gas (N2) flow rate was 60 mL min−1 and injected sample volume was 5 μL. Samples were prepared as follows: first, 0.7 mL of culture were removed from syringes and extracted from the water-phase using 1:1 n-hexane; then, they were vigorously shaken for 1 min and set aside for 15 min. The upper layer of hexane and extracted dodecane was collected and injected into the GC-FID. Ectoine was assessed according to Onraedt et al.46.

Transcriptomic analysis

Ten independent cultures of A. borkumensis SK2 were grown at 0.1 and 10 MPa as described above. At the end of the experiments, HP was gently released and cultures pooled together for centrifugation within 5 min. Centrifuge was pre-refrigerated at 4 °C and cells centrifuged at 13000rpm for 5min (Sorval RC5c PLUS, Beckman, Suarlée, Belgium). Supernatant was discarded, RNAlater added (ThermoFischer, Gent, Belgium) and pellets stored at −80 °C for further RNA extraction.

RNA extraction and QC

RNA was isolated from pelleted cells using the Rneasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Antwerp, Belgium) following manufacturer’s instructions. On-column DNase digestion was performed during RNA extraction. RNA concentration was determined using the NanoDrop 2000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Pellets recovered after incubation at 0.1 and 10 MPa yielded 855.4 and 164.3 ng RNA/μL, respectively. RNA quality control was performed using the 2100 Bioanalyzer microfluidic gel electrophoresis system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA).

RNA library prep and sequencing

Libraries for RNA-sequencing were prepared using the ScriptSeq Complete (Bacteria) sample prep kit (Epicentre – Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Starting material (1 μg) of total RNA was depleted of rRNAs using Ribo-Zero magnetic bead based capture-probe system (Illumina, Hayward, USA). Remaining RNA (including mRNAs, lin-cRNAs and other RNA species) was subsequently purified (Agencourt RNA- Clean XP, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and fragmented using enzymatic fragmentation. First and second strand synthesis were performed and double stranded cDNA was purified (AgencourtAMPure XP). RNA stranded libraries were pre-amplified and purified (AgencourtAMPure XP). Library size distribution was validated and quality inspected using the 2100 Bioanalyzer (high sensitivity DNA chip, Agilent Technologies). High quality libraries were quantified using the Qubit Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), concentration normalized and samples pooled according to number of reads. Sequencing was performed on a NextSeq500 instrument using Mid Output sequencing kit (150 cycles) according to manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina).

Data processing workflow

Data analysis pipeline was based on the Tuxedo software package. Components of the RNA-seq analysis pipeline included Bowtie2 (v. 2.2.2), TopHat (v2.0.11) and Cufflinks (v2.2.1) and are described in detail below. TopHat is a fast splice junction mapper for RNA-Seq reads, which aligns sequencing reads to the reference genome using the sequence aligner Bowtie2. It uses sequence alignments to identify splice junctions for both known and novel transcripts. Cufflinks takes the alignment results from TopHat to assemble the aligned sequences into transcripts, constructing a map of the transcriptome, based on a previously reported transcriptome annotation69.

Data analysis

Genes were grouped according to orthologous clusters using the database provided by Ortholuge DB70. Only clusters classified as supporting-species-divergence (SSD) and Borderline-SSD were considered and the rest were discarded (Divergent-SSD, Similar Non-SSD and unevaluated orthologs [RBB]). Up and downregulation analysis was expressed on a log2 basis, indicating fold changes in fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) between samples at 0.1 and 10 MPa. Gene clusters were arbitrarily considered up-regulated under HP when their log2 fold change was higher than 0.5 between 0.1 and 10 MPa. On the contrary, it was considered that downregulated genes had a −0.50 fold change. All gene clusters that were expressed between −0.5 and 0.5 were considered to be unaffected by the increase in HP. Hence, the ±0.5 log2 fold change was established in order to have a reasonable compromise in the definition of both upregulated and unaffected genes, provided that a higher threshold may be more appropriate to assess upregulation but would result into an overestimation of unaffected genes. Final analysis of up and down-regulated genes, and clusters of orthologous gene (COG) category was done using the database provided by KEGG (www.genome.jp/kegg).

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean values of experiments made in 4 to 20 independent replicates. Bars in the graphs indicate a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) calculated using a Student t-test with a two-sided distribution. Statistical significance was assessed using a nonparametric test (Mann-Whitney test) which considered a two-sided distribution with 95% CI.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Scoma, A. et al. An impaired metabolic response to hydrostatic pressure explains Alcanivorax borkumensis recorded distribution in the deep marine water column. Sci. Rep. 6, 31316; doi: 10.1038/srep31316 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by FP-7 project Kill Spill (No. 312139, “Integrated Biotechnological Solutions for Combating Marine Oil Spills”) and by the Geconcentreerde Onderzoeksactie (GOA) of Ghent University (BOF15/GOA/006). The authors thank the support of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (baseline research funds to D.D.). Ms Maria Elena Antinori is acknowledged for her technical assistance. The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the Reviewers, whose comments remarkably improved the quality of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions A.S. conceived the paper, designed and performed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper. M.B. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. S.B. and D.D. conceived the project and co-wrote the paper. N.B. conceived the project, designed the experiments and co-wrote the paper.

References

- Casselman A. 10 biggest oil spills in history (2010). Available at: http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/energy/coal-oil-gas/biggest-oil-spills-in-history. (Accessed: 17th April 2016).

- Bargiela R. et al. Bacterial population and biodegradation potential in chronically crude oil-contaminated marine sediments are strongly linked to temperature. Sci Rep. 5 doi: 10.1038/srep11651 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara A., Syutsubo K. & Harayama S. Alcanivorax which prevails in oil-contaminated seawater exhibits broad substrate specificity for alkane degradation. Environ Microbiol. 5, 746–753 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakimov M. M. et al. Natural microbial diversity in superficial sediments of Milazzo Harbor (Sicily) and community successions during microcosm enrichment with various hydrocarbons. Environ Microbiol. 7(9), 1426–1441 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syutsubo K., Kishira H. & Harayama S. Development of specific oligonucleotide probes for the identification and in situ detection of hydrocarbon-degrading Alcanivorax strains. Environ Microbiol. 3, 371–379 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta T. K. & Harayama S. Biodegradation of n-alkylcycloalkanes and n-alkylbenzenes via new pathways in Alcanivorax sp. strain MBIC 4326. Appl Environ Microbiol. 67, 1970–1974 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakimov M. M. et al. Alcanivorax borkumensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new, hydrocarbon-degrading and surfactant-producing marine bacterium. Int J Sys Bacteriol. 48(2), 339–348 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakimov M. M., Timmis K. N. & Golyshin P. N. Obligate oil-degrading marine bacteria. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 18, 257–266 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head I. M., Jones D. M. & Röling W. F. Marine microorganisms make a meal of oil. Nature Rev Microbiol. 4(3), 173–182 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai Y. et al. Predominant growth of Alcanivorax strains in oil-contaminated and nutrient-supplemented sea water. Environ Microbiol 4, 141–147 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziervogel K. et al. Microbial activities and dissolved organic matter dynamics in oil-contaminated surface seawater from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill site. Plos One 7(4), e34816 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton J. S., Rigler M. W., Boehm P. D. & Fiest D. L. Ixtoc 1 oil spill: flaking of surface mousse in the Gulf of Mexico. Nature Lett Nature 290, 235–238 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Solution group, Oil budget calculator (2010) Available at: www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2010/PDFs/OilBudgetCalc_Full_HQ-Print_111110.pdf (Accessed: 17th April 2016).

- Fu J., Gong Y., Zhao X., O’Reilly S. E. & Zhao D. Effects of oil and dispersant on formation of marine oil snow and transport of oil hydrocarbons. Env Sci Technol. 48(24), 14392–14399 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy C. M. et al. Composition and fate of gas and oil released to the water column during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. PNAS 109(50), 20229–20234 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen T. C. et al. Deep-sea oil plume enriches indigenous oil-degrading bacteria. Science 330(6001), 204–208 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine D. L. et al. Propane respiration jump-starts microbial response to a deep oil spill. Science 330(6001), 208–211 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bælum J. et al. Deep-sea bacteria enriched by oil and dispersant from the Deepwater Horizon spill. Environ Microbiol. 14(9), 2405–2416 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason O. U. et al. Metagenome, metatranscriptome and single-cell sequencing reveal microbial response to Deepwater Horizon oil spill. ISME J. 6(9), 1715–1727 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez T. et al. Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria enriched by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill identified by cultivation and DNA-SIP. ISME J. 7(11), 2091–2104 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yergeau E. et al. Microbial Community Composition, Functions, and Activities in the Gulf of Mexico 1 Year after the Deepwater Horizon Accident. Appl Environ Microbiol. 81(17), 5855–5866 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilli R. et al. Tracking hydrocarbon plume transport and biodegradation at Deepwater Horizon. Science 330(6001), 201–204 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostka J. E. et al. Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria and the bacterial community response in Gulf of Mexico beach sands impacted by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. App Env Microbiol. 77(22), 7962–7974 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button D. K. The influence of clay and bacteria on the concentration of dissolved hydrocarbon in saline solution. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 40(4), 435–440 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Elías E. J. & McKinney J. D. Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacteria. Cell Microbiol. 8(1), 10–22 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harayama S., Kishira H., Kasai Y. & Shutsubo K. Petroleum biodegradation in marine environments. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1(1), 63–70 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harayama S., Kasai Y. & Hara A. Microbial communities in oil-contaminated seawater. Curr Op Biotechnol. 15(3), 205–214 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimes N. E. et al. Metagenomic analysis and metabolite profiling of deep–sea sediments from the Gulf of Mexico following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Front Microbiol. 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. & Shao Z. Alcanivorax dieselolei sp. nov., a novel alkane-degrading bacterium isolated from sea water and deep-sea sediment. Int J Sys Ev Microbiol. 55(3), 1181–1186 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Q., Wang J., Gu L., Zheng T. & Shao Z. Alcanivorax marinus sp. nov., isolated from deep sea water of Indian Ocean. Int J Sys Ev Microbiol. 63, 4428–4432 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Q. et al. Alcanivorax pacificus sp. nov., isolated from a deep-sea pyrene-degrading consortium. Int J Sys Ev Microbiol. 61(6), 1370–1374 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oger P. M. & Jebbar M. The many ways of coping with pressure. Research Microbiol. 161(10), 799–809 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinski E. A., Pfeiffer H. P. & Trüper H. G. 1, 4, 5, 6 – Tetrahydro – 2 – methyl – 4 - pyrimidinecarboxylic acid. Eur J Biochem. 149(1), 135–139 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M. F. Organic compatible solutes of halotolerant and halophilic microorganisms. Saline Sys. 1(5), 1–30 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz R. P. & Galinski E. A. Compatible solutes in luminescent bacteria of the genera Vibrio, Photobacterium and Photorhabdus (Xenorhabdus): occurrence of ectoine, betaine and glutamate. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 142(2–3), 195–201 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Martin D., Bartlett D. H. & Roberts M. F. Solute accumulation in the deep-sea bacterium Photobacterium profundum. Extrem 6(6), 507–514 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish A. et al. High-pressure tolerance in Halobacterium salinarum NRC-1 and other non-piezophilic prokaryotes. Extrem. 16(2), 355–361 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoma A. et al. Microbial oil-degradation under mild hydrostatic pressure (10 MPa): which pathways are impacted in piezosensitive hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria? Sci Rep. 6, doi: 10.1038/srep23526 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagàn R. & Mackey B. Relationship between membrane damage and cell death in pressure-treated Escherichia coli cells: differences between exponential- and stationary-phase cells and variation among strains. App Env Microbiol. 66(7), 2829–2834 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D. & Eisen G. In Bacterial physiology: microbiology (eds Harper & Row) 96–97 (Maryland, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- Loferer-Krößbacher M., Klima J. & Psenner R. Determination of bacterial cell dry mass by transmission electron microscopy and densitometric image analysis. Appl Env Microbiol. 64(2), 688–694 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. H., Lang Y. J. & Nagata S. Efficient production of ectoine using ectoine-excreting strain. Extrem 13(4), 717–724 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard T. et al. Ectoine accumulation and osmotic regulation in Brevibacterium linens. Microbiol. 139(1), 129–136 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Onraedt A. E., Walcarius B. A., Soetaert W. K. & Vandamme E. J. Optimization of ectoine synthesis through fed-batch fermentation of Brevibacterium epidermis. Biotechnol prog. 21(4), 1206–1212 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabirova J. S., Ferrer M., Regenhardt D., Timmis K. N. & Golyshin P. N. Proteomic insights into metabolic adaptations in Alcanivorax borkumensis induced by alkane utilization. J Bacteriol 188, 3763–3773 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo F. Degradation of alkanes by bacteria. Environ Microbiol. 11(10), 2477–2490 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naether D. J. et al. Adaptation of the hydrocarbonoclastic bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis SK2 to alkanes and toxic organic compounds: a physiological and transcriptomic approach. Appl Environ Microbiol. 79(14), 4282–4293 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumenq P. et al. Influence of n-alkanes and petroleum on fatty acid composition of a hydrocarbonoclastic bacterium: Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus strain 617. Chemosph. 44, 519–528 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho C., Wick L. Y. & Heipieper H. J. Cell wall adaptations of planktonic and biofilm Rhodococcus erythropolis cells to growth on C5 to C16 n-alkane hydrocarbons. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 82, 311–320 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg H. L. The role and control of the glyoxylate cycle in Escherichia coli. Biochemic J 99(1), 1–11 (1966). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan M. T., Martinko J. M., Parker J. & Brock T. D. Biology of microorganisms (Prentice Hall, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- Lin S., Hanson R. E. & Cronan J. E. Biotin synthesis begins by hijacking the fatty acid synthetic pathway. Nature Chem Biol. 6(9), 682–688 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krulwich T. A., Ito M., Hicks D. B., Gilmour R. & Guffanti A. A. pH homeostasis and ATP synthesis: studies of two processes that necessitate inward proton translocation in extremely alkaliphilic Bacillus species. Extrem 2(3), 217–222 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohwada T. & Sagisaka S. An immediate and steep increase in ATP concentration in response to reduced turgor pressure in Escherichia coli B. Arch Biochem Biophys. 259(1), 157–163 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J. W., Venema G. & Kok J. Environmental stress responses in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 23(4), 483–501 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura P. & Marquis R. E. Energetics of streptococcal growth inhibition by hydrostatic pressure. Appl Env Microbiol. 33(4), 885–892 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato C. & Qureshi M. H. Pressure response in deep-sea piezophilic bacteria. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1(1), 87–92 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe F., Kato C. & Horikoshi K. Pressure-regulated metabolism in microorganisms. Trends Microbiol. 7(11), 447–453 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz J. R. & Landau J. V. Inhibition of cell-free protein synthesis by hydrostatic pressure. J Bacteriol. 112(3), 1222–1227 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somero G. N. Adaptations to high hydrostatic pressure. Ann Rev Physiol. 54(1), 557–577 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard E. C. & Weller P. K. The effect of hydrostatic pressure on the synthetic processes in bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Biophys Photosynt. 112(3), 573–580 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yayanos A. A. & Pollard E. C. A study of the effects of hydrostatic pressure on macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Biophys J. 9(12), 1464 (1969). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch T. J., Farewell A., Neidhardt F. C. & Bartlett D. H. Stress response of Escherichia coli to elevated hydrostatic pressure. J Bacteriol. 175(22), 7170–7177 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammi M. J. et al. Hydrostatic pressure-induced changes in cellular protein synthesis. Biorheol. 41(3–4), 309–314 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jofré A. et al. Protein synthesis in lactic acid and pathogenic bacteria during recovery from a high pressure treatment. Res Microbiol. 158(6), 512–520 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyksterhouse S. E., Gray J. P., Herwig R. P., Lara J. C. & Staley J. T. Cycloclasticus pugetii gen. nov., sp. nov., an aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium from marine sediments. Int J Sys Bacteriol. 45(1), 116–123 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito A., Ventoura G., Casadei M., Robinson T. & Mackey B. Variation in resistance of natural isolates of Escherichia coli O157 to high hydrostatic pressure, mild heat, and other stresses. Appl Env Microbiol. 65(4), 1564–1569 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Roy K., Clement L., Thas O., Wang Y. & Boon N. Flow cytometry for fast microbial community fingerprinting. Water Res. 46(3), 907–919 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiker S. et al. Genome sequence of the ubiquitous hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis. Nature Biotechnol. 24(8), 997–1004 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside M. D., Winsor G. L., Laird M. R. & Brinkman F. S. OrtholugeDB: a bacterial and archaeal orthology resource for improved comparative genomic analysis. Nuc Acid Res. 41(D1), D366–D376 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.