Abstract

Purpose

Survival for children and young adults with high-risk B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia has improved significantly, but 20% to 25% of patients are not cured. Children’s Oncology Group study AALL0232 tested two interventions to improve survival.

Patients and Methods

Between January 2004 and January 2011, AALL0232 enrolled 3,154 participants 1 to 30 years old with newly diagnosed high-risk B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. By using a 2 × 2 factorial design, 2,914 participants were randomly assigned to receive dexamethasone (14 days) versus prednisone (28 days) during induction and high-dose methotrexate versus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate plus pegaspargase during interim maintenance 1.

Results

Planned interim monitoring showed the superiority of the high-dose methotrexate regimens, which exceeded the predefined boundary and led to cessation of enrollment in January 2011. At that time, participants randomly assigned to high-dose methotrexate during interim maintenance 1 versus those randomly assigned to Capizzi methotrexate had a 5-year event-free survival (EFS) of 82% versus 75.4% (P = .006). Mature final data showed 5-year EFS rates of 79.6% for high-dose methotrexate and 75.2% for Capizzi methotrexate (P = .008). High-dose methotrexate decreased both marrow and CNS recurrences. Patients 1 to 9 years old who received dexamethasone and high-dose methotrexate had a superior outcome compared with those who received the other three regimens (5-year EFS, 91.2% v 83.2%, 80.8%, and 82.1%; P = .015). Older participants derived no benefit from dexamethasone during induction and experienced excess rates of osteonecrosis.

Conclusion

High-dose methotrexate is superior to Capizzi methotrexate for the treatment of high-risk B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia, with no increase in acute toxicity. Dexamethasone given during induction benefited younger children but provided no benefit and was associated with a higher risk of osteonecrosis among participants 10 years and older.

INTRODUCTION

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common malignancy in children and a major cause of cancer death before age 40 years. Approximately 85% of pediatric ALL cases are B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), subclassified as National Cancer Institute (NCI) standard risk and high risk (HR) based on age and WBC count.1 Clinical trials have produced incremental improvements in event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) for children with HR B-ALL2 through intensification of postinduction therapy and more accurate risk stratification.3-13

Compared with prednisolone, dexamethasone has greater cytotoxic effects on ALL cells in vitro,14,15 superior CNS penetration, and a longer CSF half-life.16 In clinical trials, dexamethasone has a greater antileukemic effect than prednisone17-20 but is associated with increased toxicities, including induction death, fractures, osteonecrosis, and behavioral disturbances.21-24

Methotrexate is a critical component of ALL therapy and plays an important role in CNS prophylaxis. Worldwide, two different methotrexate intensification strategies have been studied: High-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) regimens of 2 to 5 g/m2 administered over 24 hours followed by leucovorin rescue5,6,26 and the Capizzi regimen with lower, escalating doses of intravenous methotrexate (C-MTX) of 100 to 300 mg/m2 through short infusions, without leucovorin rescue, followed by asparaginase.3,4 Both strategies are effective, but they have never been directly compared in childhood ALL. Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL0232 tested the safety and efficacy of dexamethasone versus prednisone during induction and HD-MTX with leucovorin rescue versus C-MTX plus pegaspargase during interim maintenance 1.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Characteristics

AALL0232 enrolled participants between January 2004 and January 2011. Patients with newly diagnosed B-ALL age 1 to 9 years with initial WBC ≥ 50,000/μL or 10 to 30 years with any WBC were eligible. The diagnosis was determined by morphologic, biochemical, and immunologic features.3,4 CNS status was defined based on CSF obtained before therapy as follows: CNS1 (no blasts), CNS2 (CSF WBC < 5/μL with blasts), or CNS3 (CSF WBC ≥ 5/μL with blasts and/or clinical signs of CNS leukemia). AALL0232 was approved by NCI and the institutional review boards of participating institutions. Informed consent was obtained from participants or a parent/guardian in accordance with Department of Health and Human Services guidelines.

Treatment

AALL0232 used a 2 × 2 factorial design with a COG-modified augmented intensity Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster backbone.3 Eligible participants were randomly assigned at study entry to receive dexamethasone (10 mg/m2/day) on days 1 to 14 versus prednisone (60 mg/m2/day) on days 1 to 28 during induction and HD-MTX versus C-MTX during interim maintenance 1. Treatment regimens PC, PH, DC, and DH were designated by the corticosteroid (prednisone [P], dexamethasone [D]) and methotrexate (Capizzi [C], high dose [H]) assignments. Early response was used to refine treatment.

Rapid early responders (RERs) had an M1 marrow (< 5% blasts) by induction day 15 and < 0.1% minimal residual disease (MRD) in the day 29 marrow by flow cytometry.28 Slow early responders (SERs) had an M1 marrow on induction day 29 but with either an M2 (5% to 25% blasts) or M3 (> 25% blasts) marrow on induction day 15 or MRD ≥ 0.1% on day 29 marrow. They received a second interim maintenance with C-MTX, a second delayed intensification, and 12-Gy cranial irradiation. Patients with an M2 marrow or ≥ 1% MRD at day 29 received 2 additional weeks of induction therapy and were considered SERs if their day 43 marrow was M1 with < 1% MRD; otherwise, they were considered induction failures and removed from protocol therapy, as were those with an M3 marrow at day 29. Patients with CNS3 status were nonrandomly assigned to receive HD-MTX and 18-Gy cranial irradiation. Those with testicular leukemia at diagnosis and those who received > 48 hours of corticosteroid therapy in the week before diagnosis participated in the induction corticosteroid random assignment but were nonrandomly assigned to HD-MTX with two interim maintenance and delayed intensification phases. If testicular involvement was not resolved at end induction, 24-Gy testicular irradiation was given during consolidation. Patients with very-high-risk (VHR) ALL—BCR-ABL1 fusion, hypodiploidy with < 44 chromosomes, and/or DNA index < 0.81, induction failure, or SER with MLL rearrangement—were removed from protocol therapy after induction. Therapy was continued for 2 years for females and 3 years for males from the beginning of interim maintenance 1. Therapy details are provided in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

Therapy amendments were made during the conduct of AALL0232. Patients with Down syndrome were initially eligible, and 44 were randomly assigned between the DC and PC treatment regimens, but this group experienced excessive toxic mortality and were made ineligible for enrollment in 2006. An increased incidence of osteonecrosis was observed in children 10 years of age and older assigned to dexamethasone during induction. Consequently, AALL0232 was amended in 2008 to exclude patients 10 years of age and older from the corticosteroid assignment. Additionally, all subsequently received discontinuous dexamethasone during delayed intensification and prednisone during maintenance.

Toxicity Assessment

Data on adverse events and clinically significant laboratory findings were collected using the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0 until December 2010 and version 4.0 thereafter. Adverse event reporting was supplemented with the NCI Adverse Event Expedited Reporting System and MedWatch reports.

Statistical Analysis

The study was originally designed as a 2 × 2 randomized factorial design, with the first factor comparing the induction corticosteroid (prednisone versus dexamethasone) and the second comparing methotrexate approaches (HD-MTX versus C-MTX) during interim maintenance 1. Random assignment occurred at study entry. Power calculations are based on log-rank test, with 10 planned interim analyses monitoring for efficacy. Two-sided log-rank tests were to be used for EFS comparisons.

Interim monitoring in January 2011 revealed that the predefined efficacy monitoring boundary had been crossed by showing increased efficacy for HD-MTX compared with C-MTX, which led to early closure of accrual. All patient assigned to C-MTX who had not yet finished the first cycle of maintenance therapy crossed over to the HD-MTX regimen.

EFS was defined as the time from study entry to first event (induction failure, induction death, relapse, second malignancy, remission death) or date of last follow-up for event-free patients. Those who crossed over to the HD-MTX arm were censored at the time of crossover. OS was defined as the time from study entry to death or date of last follow-up. Survival rates were estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier method with standard errors.29,30 Survival curves were compared by using the log-rank test. Cumulative incidence rates between regimens were computed by using the cumulative incidence function for competing risks, and comparisons were conducted with the K-sample test.31 P < .05 was considered significant for all comparisons. All analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Graphics were generated with R version 2.13.1 (http://www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Participants

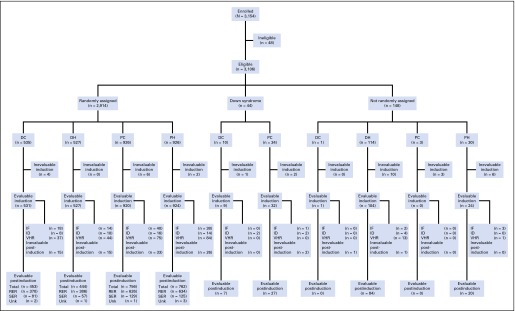

AALL0232 enrolled 3,154 participants—48 were ineligible; 44 had Down syndrome; and 148 were nonrandomly assigned to specific regimens due to CNS3 status, testicular involvement, or extensive corticosteroid pretreatment (Fig 1). The remaining 2,914 participants were randomly assigned to the four treatment regimens—PC (n = 926), PH (n = 926), DC (n = 535), DH (n = 527). Randomly assigned participants with VHR ALL features—BCR-ABL1 (n = 135), hypodiploidy (n = 81), MLL rearrangement with SER (n = 24)—were removed from protocol therapy after induction and are excluded from this report. Of the randomly assigned participants with complete data at the end of induction (n = 2,554), 80.3% were classified as RERs (n = 2,051) and 19.7% were classified as SERs (n = 503). These include 35 RERs and 111 SERs classified as induction failures or induction deaths.

Fig 1.

Consort diagram for Children’s Oncology Group AALL0232. DC, dexamethasone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen; DH, dexamethasone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen; IF, induction failure; ID, induction death; PC, prednisone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen; PH, prednisone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen; RER, rapid early responder; SER, slow early responder; Unk, unknown; VHR, very high risk.

Age distribution ranged from 12 months to 30 years, with 33% 1 to 9 years old, 47% 10 to 15 years old, and 20% 16 to 30 years old, including 2% age 21 years and older. Fifty-four percent were male and 46% female. African American enrollment was 6.7%, and Hispanic enrollment was 23.8%. The presenting WBC distribution was 37.6% < 10,000/μL, 18.9% 10 to 49,999/μL, 23.9% 50 to 99,999/μL, 12.6% 100 to 199,999/μL, and 7.0% ≥ 200,000/μL. The distribution of CNS status at entry was 85.9% CNS1 and 14.1% CNS2 for the randomized cohort.

Treatment Outcome

The 5-year EFS and OS for the 2,979 participants eligible and evaluable for postinduction therapy was 75.2 ± 1.1% and 85.0 ± 0.9%, respectively (Fig 2A). For the 2,573 participants considered in the evaluation of the randomized questions (eligible, evaluable for postinduction therapy, not VHR, and not Down syndrome), the 5-year EFS was 77.5 ± 1.2%, and OS was 87.5 ± 0.9% (Fig 2B). As expected, RERs had better 5-year EFS (83.9 ± 1.1% v 53.3 ± 3.1%, P < .001; Appendix Fig A1A) and OS (91.3 ± 0.9% v 74.3 ± 2.8%, P < .001; Appendix Fig A1B) than SERs.

Fig 2.

(A) Event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) for eligible, evaluable enrolled participants. The 5-year EFS and OS rates were 75.3 ± 1.1% and 85.0 ± 0.9%, respectively. (B) EFS and OS for non–Down syndrome, non–very-high-risk randomly assigned participants. The 5-year EFS and OS rates were 77.5 ± 1.2% and 87.5 ± 0.9%, respectively.

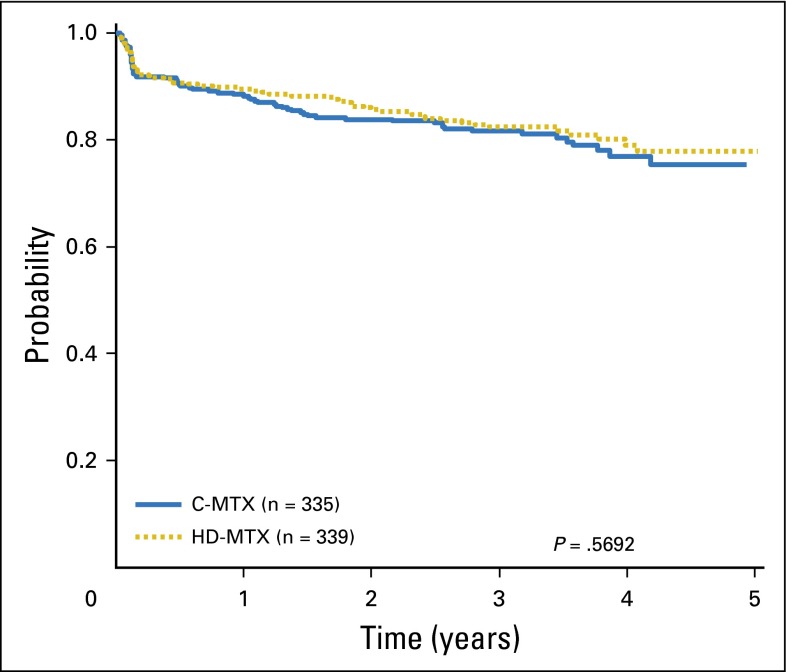

Methotrexate Random Assignment

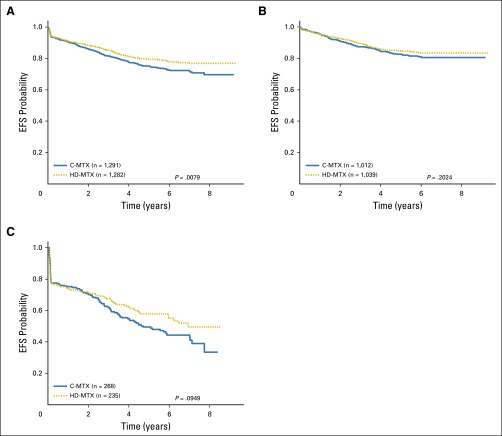

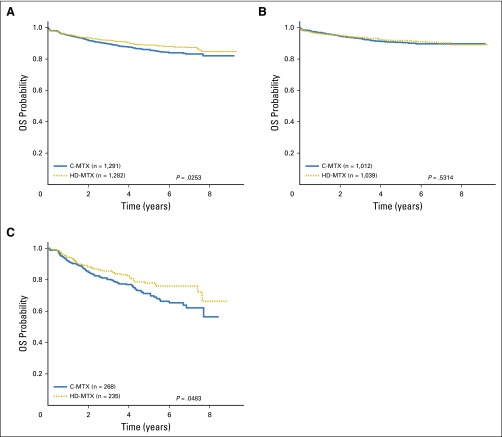

Interim monitoring in January 2011 showed that the predefined efficacy monitoring boundary had been crossed, with superior outcomes for participants assigned to HD-MTX versus C-MTX, and AALL0232 accrual was halted. At that time, the estimated 5-year EFS rates were 82 ± 3.4% (HD-MTX) versus 75.4 ± 3.6% (C-MTX; P = .006). Therapy changes were recommended to provide HD-MTX to all participants who had not yet completed course 1 of maintenance or received cranial irradiation. For the final analyses, the outcome of those assigned to C-MTX who subsequently received HD-MTX was censored at the time of therapy crossover (n = 127). These analyses showed 5-year EFS rates of 79.6 ± 1.6% for the HD-MTX regimens versus 75.2 ± 1.7% for the C-MTX regimens (P = .008; Fig 3A) and 5-year OS rates of 88.9 ± 1.2% for HD-MTX and 86.1 ± 1.4% for C-MTX (P = .025; Appendix Fig A2A). For RERs, the 5-year EFS rates were 84.9 ± 1.6% for HD-MTX versus 82.8 ± 1.7% for C-MTX (P = .202; Fig 3B), and OS rates were 91.8 ± 1.2% versus 90.7 ± 1.3% (P = .531; Appendix Fig A2B). For SERs, the 5-year EFS rates were 57.8 ± 4.6% for HD-MTX and 49.4 ± 4.2% for C-MTX (P = .095; Fig 3C), and OS rates were 77.9 ± 3.8% versus 71.2 ± 3.9% (P = .048; Appendix Fig A2C). For patients 10 years of age and older nonrandomly assigned to receive prednisone during induction after April 2008, those randomly assigned to receive HD MTX had a nonsignificant trend towards improved outcome (4-year EFS 79.1% v 77% with C-MTX; P = .569; Figure A4). Five-year cumulative incidence rates for HD-MTX versus C-MTX were 7.0 ± 0.8% and 8.6 ± 0.9% for marrow relapse (P = .089), 2.9 ± 0.5% versus 4.1 ± 0.6% for CNS relapse (P = .09), and 2.0 ± 0.4% versus 2.1 ± 0.4% for remission deaths (P = .89). Table 1 provides the raw number of events by methotrexate regimen.

Fig 3.

(A) Event-free survival (EFS) comparisons by methotrexate regimen, all randomly assigned participants. The 5-year EFS rates for Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate (C-MTX) and high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) were 75.2 ± 1.7% and 79.6 ± 1.6%, respectively. (B) EFS comparisons by methotrexate regimen, randomly assigned participants with a rapid early response. The 5-year EFS rates for C-MTX and HD-MTX were 82.8 ± 1.7% and 84.9 ± 1.6%, respectively. (C) EFS comparisons by methotrexate regimen; randomly assigned participants with a slow early response. The 5-year EFS rates for C-MTX and HD-MTX were 49.4 ± 4.2% and 57.8 ± 4.6%, respectively.

Table 1.

Event Summary by Randomly Assigned Regimen

| Methotrexate Regimen | Corticosteroid Regimen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | C-MTX | HD-MTX | P* | Total | Dex | Prednisone | P* | Total |

| None | 993 | 1,036 | .02 | 2,029 | 747 | 735 | .38 | 1,482 |

| Induction failure | 58 | 52 | .58 | 110 | 32 | 38 | .48 | 70 |

| Induction death | 24 | 24 | .98 | 48 | 18 | 17 | .85 | 35 |

| Relapse | ||||||||

| Marrow | 104 | 82 | .10 | 186 | 80 | 74 | .59 | 154 |

| CNS | 49 | 34 | .10 | 83 | 27 | 39 | .14 | 66 |

| Testicular | 3 | 4 | .70 | 7 | 4 | 2 | .41 | 6 |

| Combined + other | 27 | 16 | .10 | 43 | 19 | 20 | .88 | 39 |

| Second malignant neoplasm | 8 | 10 | .63 | 18 | 5 | 11 | .13 | 16 |

| Death | 25 | 24 | .90 | 49 | 15 | 16 | .87 | 31 |

Abbreviations: C-MTX, Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate; Dex, dexamethasone; HD-MTX, high-dose methotrexate.

χ2 test.

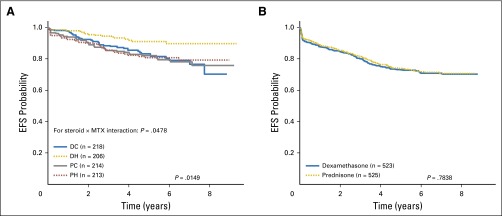

Corticosteroid Random Assignment

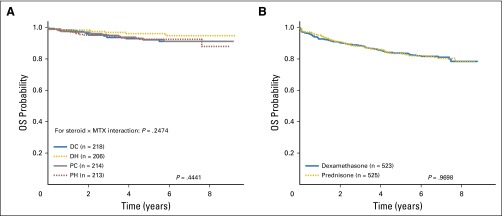

Participants 1 to 9 years of age (n = 851) were randomly assigned to the corticosteroid and methotrexate regimens—DH (n = 206), DC (n = 218), PH (n = 213), PC (n = 214). Because there was a significant qualitative interaction between the corticosteroid and methotrexate assignments (P = .048), EFS comparisons were made among the four regimens. The DH regimen was superior, with a 5-year EFS rate of 91.2 ± 2.8% compared with 83.2 ± 3.4% (DC), 80.8 ± 3.7% (PH), and 82.1 ± 3.5% (PC; P = .015; Fig 4A) and a nonsignificant trend toward improved 5-year OS (P = .444; Appendix Fig A3A). Five-year cumulative incidence rates for the four regimens were 3.2 ± 1.3% (DH), 7.3 ± 2.0% (DC), 3.5 ± 1.4% (PH), and 4.8 ± 1.7% (PC) for marrow relapse (P = .024) and 2.0 ± 1.0% (DH), 4.9 ± 1.5% (DC), 5.0 ± 1.6% (PH), and 5.4 ± 1.6% (PC) for CNS relapse (P = .28).

Fig 4.

(A) Event-free survival (EFS) comparisons by treatment regimen, randomly assigned participants age 1 to 9 years. The 5-year EFS rates by regimen were prednisone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen (PC), 82.1 ± 3.5%; prednisone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen (PH), 80.8 ± 3.7%; dexamethasone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen (DC), 83.2 ± 3.4%; and dexamethasone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen (DH), 91.2 ± 2.8%. (B) EFS comparisons by steroid regimen, participants age 10 years or older. The 5-year EFS rates for dexamethasone regimens and prednisone regimens were 73.1 ± 2.1% and 73.9 ± 2.2%, respectively.

Before June 2008, when the induction corticosteroid random assignment was closed to older patients due to excess rates of osteonecrosis with dexamethasone, 1,048 participants 10 years of age and older were randomly assigned to dexamethasone (n = 523) and prednisone (n = 525). The 5-year EFS rates for the older participants were virtually identical at 73.1 ± 2.1% (dexamethasone) and 73.9 ± 2.2% (prednisone; P = .78; Fig 4B) as were 5-year OS rates (P = .97; Appendix Fig A3B). Appendix Table A2 provides the raw number of events by corticosteroid regimen.

Toxicity

Nonrelapse mortality.

Among the 3,106 eligible and evaluable participants, 104 experienced death as a first event, with 53 (1.7%) induction deaths and 51 (1.7%) remission deaths. Among all eligible, evaluable, randomly assigned participants (n = 2,573), 97 experienced death as a first event, with 48 (1.9%) induction deaths and 49 (1.9%) remission deaths. Induction deaths occurred in 1.7% (18 of 1,062) participants assigned to dexamethasone and 1.7% (30 of 1,852) of those assigned to prednisone. The 5-year cumulative incidence rate for remission deaths was 2.0 ± 0.3%. The 5-year cumulative incidence rates of remission deaths among all randomly assigned participants were as follows: DC, 1.8 ± 0.6%; DH, 1.4 ± 0.6%; PC, 2.3 ± 0.6%; and PH, 2.3 ± 0.6% (P = .77). The higher rates observed on the prednisone induction arms are due to nonrandom assignment of older patients to these arms after 2008.

Methotrexate random assignment.

There was a higher rate of febrile neutropenia during interim maintenance 1 in the C-MTX regimens (8.3% v 5.1% with HD-MTX; P = .003; Table 2). Ischemic cerebrovascular toxicity was observed in five patients who received HD-MTX, whereas no patients who received C-MTX had this toxicity (P =.03). No other statistically significant differences were found in toxicity between the methotrexate regimens during interim maintenance 1, including mucositis, neurotoxicity, osteonecrosis, and death in remission.

Table 2.

Interim Maintenance and Induction Toxicities by Treatment Regimen

| Methotrexate Regimen | Corticosteroid Regimen | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/Phase | C-MTX, No. (%) | HD-MTX, No. (%) | P | Dex, No. (%) | Prednisone, No. (%) | P |

| Age < 10 years | ||||||

| Interim maintenance 1 toxicity | ||||||

| No. of participants | 408 | 389 | ||||

| Mucositis oral | 15 (3.7) | 42 (10.8) | < .001 | |||

| Mucositis (any) | 18 (4.4) | 43 (11.1) | .001 | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 25 (6.1) | 22 (5.7) | .78 | |||

| Infections/infestations | 40 (9.8) | 48 (12.3) | .25 | |||

| Seizure | 14 (3.4) | 7 (1.8) | .15 | |||

| Ischemia cerebrovascular | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | .49 | |||

| Induction toxicity | ||||||

| No. of participants | 424 | 427 | ||||

| Colitis | 6 (1.4) | 1 (0.2) | .07 | |||

| Typhlitis | 4 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) | .72 | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 110 (25.9) | 64 (15.0) | < .001 | |||

| Infections/infestations | 149 (35.1) | 108 (25.3) | .002 | |||

| Induction deaths | 3 (0.7) | 4 (0.9) | .71 | |||

| Age ≥ 10 years | ||||||

| Interim maintenance 1 toxicity | ||||||

| No. of participants | 744 | 736 | ||||

| Mucositis oral | 129 (17.3) | 110 (14.9) | .21 | |||

| Mucositis (any) | 144 (19.4) | 119 (16.2) | .11 | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 70 (9.4) | 35 (4.8) | < .001 | |||

| Infections/infestations | 101 (13.6) | 90 (12.2) | .44 | |||

| Seizure | 7 (0.9) | 11 (1.5) | .33 | |||

| Ischemia cerebrovascular | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) | .06 | |||

| Induction toxicity | ||||||

| No. of participants | 522 | 525 | ||||

| Colitis | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | .45 | |||

| Typhlitis | 10 (1.9) | 4 (0.8) | .12 | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 62 (11.9) | 41 (7.8) | .03 | |||

| Infections/infestations | 129 (24.7) | 85 (16.2) | < .001 | |||

| Induction deaths | 15 (2.9) | 13 (2.5) | .69 | |||

| Total | ||||||

| Interim maintenance 1 toxicity | ||||||

| No. of participants | 1,152 | 1,125 | ||||

| Mucositis oral | 144 (12.5) | 152 (13.5) | .49 | |||

| Mucositis (any) | 162 (14.1) | 162 (14.4) | .86 | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 95 (8.3) | 57 (5.1) | .003 | |||

| Infections/infestations | 141 (12.2) | 138 (12.3) | 1.00 | |||

| Seizure | 21 (1.8) | 18 (1.6) | .68 | |||

| Ischemia cerebrovascular | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.4) | .03 | |||

| Induction toxicity | ||||||

| No. of participants | 946 | 952 | ||||

| Colitis | 10 (1.1) | 3 (0.3) | .05 | |||

| Typhlitis | 14 (1.5) | 7 (0.7) | .13 | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 172 (18.2) | 105 (11.0) | < .001 | |||

| Infections/infestations | 278 (29.4) | 193 (20.3) | < .001 | |||

| Induction deaths | 18 (1.9) | 17 (1.8) | .87 | |||

Abbreviations: C-MTX, Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate; Dex, dexamethasone; HD-MTX, high-dose methotrexate.

Corticosteroid random assignment.

During induction, dexamethasone was associated with higher rates of febrile neutropenia (18.2% v 11.0% with prednisone; P < .001) and infections/infestations (29.4% v 20.3% with prednisone; P < .001; Table 2). Despite higher rates of infection on the dexamethasone arms, there was no difference in the induction death rate compared with the prednisone regimens (18 of 946 [1.9%] v 17 of 952 [1.8%] with dexamethasone and prednisone, respectively; P = .87). Among patients younger than 10 years of age, induction deaths were three of 424 (0.71%) for dexamethasone and four of 427 (0.94%) for prednisone (P = .71). For those 10 years of age and older, induction deaths occurred in 15 of 522 (2.9%) assigned to dexamethasone versus 13 of 525 (2.5%) assigned to prednisone (P = .69).

Among patients 10 years of age and older who participated in the induction corticosteroid arm before it was closed in 2008, the 5-year cumulative incidence of osteonecrosis was 24.3 ± 2.3% for those assigned to 14 days of dexamethasone and 15.9 ± 2.0% for those assigned to 28 days of prednisone (P = .001). There were no other significant differences in toxicities during induction between the two corticosteroid regimens.

DISCUSSION

Survival for children and young adults with HR-ALL has improved over time due to more precise risk stratification and refinement of postinduction therapy through serial clinical trials.2,5,8-13 AALL0232 improved survival further for these patients and has changed clinical practice in North America.

Methotrexate Random Assignment

Intravenous methotrexate is a key component of ALL postinduction intensification strategies. When this study was undertaken, the COG used escalating C-MTX without leucovorin rescue plus asparaginase and vincristine, whereas most other groups used HD-MTX plus leucovorin rescue with mercaptopurine with similar outcomes. However, the impact of the HD-MTX regimen remained uncertain. AALL0232 establishes that the HD-MTX regimen is superior to C-MTX for the treatment of HR B-ALL, with mature data showing significant improvements in both 5-year EFS (80% v 75%; P = .008) and OS (88.9 ± 1.2% v 86.1 ± 1.4%; P = .025) rates. The improved outcome associated with HD-MTX occurred in all subgroups analyzed, was due to decreased rates of both marrow and CNS relapse, and was especially evident in SERs. In contrast to RERs, all SERs received a second interim maintenance phase with C-MTX. AALL0232 cannot be considered a direct comparison of methotrexate doses and schedules alone because each regimen contained additional agents (eg, 6-mercaptoputine in HD-MTX, pegaspargase in C-MTX).

Close monitoring revealed no statistically significant difference in occurrence of mucositis, neurotoxicity, osteonecrosis, or other toxicities, including death, during remission between the methotrexate regimens during interim maintenance 1. C-MTX was associated with a greater frequency of febrile neutropenia than HD-MTX (8.3% v 5.1%; P = .003). This may be due to the myelosuppressive effects of MTX given without leucovorin rescue or to the additive myelosuppressive effect of asparaginase.32 Ischemic cerebrovascular toxicity was observed in five patients who received HD-MTX compared with none who received C-MTX. Although this reached statistical significance, the small numbers preclude any definite conclusion on the clinical significance of these observations. On the basis of these findings, we conclude that HD-MTX is both efficacious and safe and should be the standard of care during interim maintenance for children and adolescents with HR B-ALL.

Corticosteroid Random Assignment

Prior studies showed that dexamethasone had greater antileukemic activity compared with prednisone but was also associated with higher rates of several toxicities.17-24 Due to concern for serious acute infectious toxicity associated with 4 weeks of dexamethasone combined with an anthracycline in a four-drug ALL induction, AALL0232 compared dexamethasone 10 mg/m2/day for 14 days to 60 mg/m2/day of prednisone for 28 days. Participants assigned to dexamethasone experienced higher rates of febrile neutropenia and infections than those assigned to prednisone; however, no significant difference in induction deaths was found. Of note, the brief, but continuous exposure to dexamethasone during induction contributed to a higher rate of subsequent osteonecrosis compared with participants assigned to prednisone (24.3% v 15.9%; P = .001) 10 years of age or older. This finding led to the termination of the corticosteroid assignment for patients 10 years and older in 2008. With consideration of the relative efficacy and toxicity of the corticosteroid regimens, AALL0232 establishes that children and adolescents 10 years of age or older with HR B-ALL should receive 28 days of prednisone during induction.

Because there was a statistical interaction between the corticosteroid and methotrexate assignments, a direct comparison between dexamethasone and prednisone is not possible in the patients younger than 10 years. Comparison of the four regimens demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in EFS and a trend toward improved OS with DH compared with the other three regimens DC, PH, and PC. On the basis of this result, AALL0232 has established a new standard of care for patients 1 to 9 years old with HR B-ALL, who should receive 14 days of dexamethasone during induction and HD-MTX during interim maintenance 1.

Dexamethasone intriguingly had more antileukemic efficacy than prednisone in younger patients, but no difference was seen among those 10 years and older. This observation may be due to age-related differences in corticosteroid pharmacokinetics. Younger patients have more rapid clearance of dexamethasone, and hence dexamethasone, a more potent corticosteroid, may enhance the impact of corticosteroid differences in this population.33,34 In contrast, older patients have slower clearance of corticosteroids, which might minimize any improvement in efficacy while contributing to an increase in bone toxicity with dexamethasone.

In conclusion, over the past 50 years, the dramatic improvement in survival for children with ALL has been a direct result of serial clinical trials conducted worldwide. The key strategies that have led to this success have been more accurate risk stratification, prophylactic treatment of the CNS, and refinement of postinduction intensification. Given the high survival of children with ALL, there have been concerns about whether outcome has reached a plateau. COG AALL0232 has demonstrated that optimization of conventional chemotherapy agents remains a viable strategy by showing superior outcome with HD-MTX for all patients with HR B-ALL as does 14 days of dexamethasone during induction for patients 1 to 9 years of age. It is likely that continued improvements in the treatment of children, adolescents, and young adults with B-ALL will derive from both further refinements in the use of conventional agents and application of targeted therapies based on novel genomic discoveries.35

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We pay special tribute to and acknowledge the significant contributions that Jim Nachman made to this article. He continually challenged our premises and kept us on task through the entire process. His keen insight, untiring work ethic, and sense of humor will never be forgotten.

Appendix

Fig A1.

(A) Event-free survival (EFS) comparison of rapid early responders (RERs) and slow early responders (SERs). The 5-year EFS rates for RERs and SERs were 83.9 ± 1.1% and 53.3 ± 3.1%, respectively. (B) Overall survival (OR) RERs and SERs. The 5-year OS rates for RERs and SERs were 91.3 ± 0.9% and 74.3 ± 2.8%, respectively.

Fig A2.

(A) Overall survival (OS) comparisons by methotrexate regimen, all randomly assigned participants. The 5-year OS rates for Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate (C-MTX) and high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) were 86.1 ± 1.4% and 88.9 ± 1.2%, respectively. (B) OS comparisons by methotrexate regimen, randomly assigned rapid early responders. The 5-year OS rates for C-MTX and HD-MTX were 90.7 ± 1.3% and 91.8 ± 1.2%, respectively. (C) OS by methotrexate regimen, randomly assigned slow early responders. The 5-year OS rates for C-MTX and HD-MTX were 71.2 ± 3.9% and 77.9 ± 3.8%, respectively.

Fig A3.

(A) Overall survival (OS) comparisons by treatment regimen, randomly assigned participants age 1 to 9 years. The 5-year OS rates by regimen were prednisone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen (PC), 92.4 ± 2.5%; prednisone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen (PH), 92.7 ± 2.4%; dexamethasone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen (DC), 92.3 ± 2.4%, and dexamethasone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen (DH), 96.3 ± 1.9%. (B) OS comparisons by steroid regimen, participants age 10 years or older. The 5-year OS rates for dexamethasone regimens and prednisone regimens were 83.8 ± 1.8% and 83.7 ± 1.8%, respectively.

Fig A4.

Event-free survival (EFS) comparison by methotrexate regimen, randomly assigned participants age 10 years and older assigned to prednisone (enrolled after April 2008). The 4-year EFS rates Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate (C-MTX) and high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) were 77.0 ± 4.8% and 79.1 ± 4.3%, respectively. Note that there was insufficient follow-up to report 5-year EFS.

Table A1.

Therapy Details

| Phase and Regimen | Drug | Dose | Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induction DC/DH | IT cytarabine | Age adjusted* | Day 0 |

| Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2 (2 mg maximum) | Days 1, 8, 15, 22 | |

| Pegaspargase | 2,500 units/m2 | Day 4, 5, or 6 | |

| Dexamethasone | 5 mg/m2/dose twice a day | Days 1-14 | |

| Daunorubicin | 25 mg/m2 | Days 1, 8, 15, 22 | |

| IT-MTX | Age adjusted* | Days 8, 29 (CNS3: +15, 22) | |

| Extended induction DC/DH | Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2 (2 mg maximum) | Days 1, 8 |

| Pegaspargase | 2,500 units/m2 | Day 4, 5, or 6 | |

| Dexamethasone | 5 mg/m2/dose twice a day | Days 1-14 | |

| Daunorubicin | 25 mg/m2 | Day 1 | |

| Induction PC/PH | IT cytarabine | Age adjusted* | Day 0 |

| Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2 (2 mg maximum) | Days 1, 8, 15, 22 | |

| Pegaspargase | 2,500 units/m2 | Day 4, 5, or 6 | |

| Prednisone | 30 mg/m2/dose twice a day | Days 1-28 | |

| Daunorubicin | 25 mg/m2 | Days 1, 8, 15, 22 | |

| Extended induction PC/PH | IT-MTX | Age adjusted* | Days 8, 29 (CNS3: +15, 22) |

| Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2 (2 mg maximum) | Days 1, 8 | |

| Pegaspargase | 2,500 units/m2 | Day 4, 5, or 6 | |

| Prednisone | 30 mg/m2/dose twice a day | Days 1-14 | |

| Daunorubicin | 25 mg/m2 | Day 1 | |

| Consolidation all | Cyclophosphamide | 1,000 mg/m2 | Days 1, 29 |

| Cytarabine | 75 mg/m2 | Days 1-4, 8-11, 29-32, 36-39 | |

| Mercaptopurine | 60 mg/m2 | Days 1-14, 29-42 | |

| Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2 (2 mg maximum) | Days 15, 22, 43, 50 | |

| Pegaspargase | 2,500 units/m2 | Days 15, 43 | |

| IT-MTX | Age adjusted* | Days 1, 8, 15, 22 | |

| Interim maintenance 1 PC/DC | Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2 (2 mg maximum) | Every 10 days × 5 doses |

| IV-MTX† | 100 mg/m2 | Every 10 days × 5 doses | |

| Pegasparagase | 2,500 units/m2 | Days 2, 22 | |

| IT-MTX | Age adjusted* | Days 1, 31 | |

| Interim maintenance 1 PH/DH | Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2 (2 mg maximum) | Days 1, 15, 29, 43 |

| IV-MTX | 5,000 mg/m2 | Days 1, 15, 29, 43 | |

| Mercaptopurine | 25 mg/m2 | Days 1-56 | |

| IT-MTX | Age adjusted* | Day 1, 29 | |

| Delayed intensification 1 all | Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2 (2 mg maximum) | Days 1, 8, 15, 43, 50 |

| Pegaspargase | 2,500 units/m2/dose | Day 4 or 5 or 6 and 43 | |

| Dexamethasone | 10 mg/m2/day | Days 1-7, 15-21 | |

| Doxorubicin | 25 mg/m2/day | Days 1, 8, 15 | |

| Cytarabine | 75 mg/m2/day | Days 29-32, 36-39 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1,000 mg/m2 | Day 29 | |

| Thioguanine | 60 mg/m2/day | Days 29-42 | |

| IT-MTX | Age adjusted* | Days 1, 29, 36 | |

| Interim maintenance 2 all | Same as interim maintenance 1 PC/DC | ||

| PC/DC start methotrexate 50 mg/m2 less than previous maximum tolerated dose | |||

| PH/DH start methotrexate at 100 mg/m2 | |||

| Delayed intensification 2 all | Same as delayed intensification 1 | ||

| Maintenance‡ (12-week cycles) | Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2 (2 mg max) | Days 1, 29, 57 |

| Prednisone | 20 mg/m2/dose twice a day | Days 1-5, 29-33, 57-61 | |

| Mercaptopurine | 75 mg/m2/day | Daily | |

| Methotrexate (oral) | 20 mg/m2/dose | Weekly | |

| IT-MTX | Age adjusted* | Days 1 (and 29 first four cycles) | |

Abbreviations: DC, dexamethasone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen; DH, dexamethasone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen; IT, intrathecal; IT-MTX, intrathecal methotrexate; IV-MTX, intravenous methotrexate; PC, prednisone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen; PH, prednisone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen.

IT cytarabine: 1 to 1.99 years, 30 mg; 2 to 2.99 years, 50 mg; ≥ 3 years, 70 mg. IT-MTX: 1 to 1.99 years, 8 mg; 2 to 2.99 years, 10 mg; 3 to 8.99 years, 12 mg; ≥ 9 years, 15 mg.

IV-MTX: 100 mg/m2 (dose escalated by 50 mg/m2 every 10 days for a total of five doses, adjusted for toxicity).

Total duration of treatment from start of interim maintenance 1: females, 2 years; males, 3 years.

Table A2.

Events by Corticosteroid Assignment

| Variable | DC | DH | PC | PH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| < 10 | 218 | 206 | 214 | 213 |

| ≥ 10 | 261 | 262 | 598 | 601 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 244 | 254 | 437 | 467 |

| Female | 235 | 214 | 375 | 347 |

| WBC, μl | ||||

| < 50 | 214 | 227 | 491 | 520 |

| ≥ 50 | 265 | 241 | 321 | 294 |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Asian | 15 | 23 | 22 | 31 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2 | 4 | 4 | 9 |

| Black or African American | 31 | 25 | 59 | 57 |

| White | 383 | 351 | 616 | 599 |

| Other | 4 | 9 | 11 | 8 |

| Unknown | 44 | 53 | 97 | 102 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 102 | 106 | 200 | 204 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 352 | 346 | 586 | 581 |

| Unknown | 25 | 16 | 26 | 29 |

| End-of-induction response | ||||

| Yes | 461 | 454 | 772 | 776 |

| No | 18 | 14 | 40 | 38 |

| MRD day 29 | ||||

| MRD < 0.01% | 310 | 335 | 560 | 579 |

| 0.01% ≤ MRD < 0.1% | 71 | 59 | 103 | 90 |

| 0.1% ≤ MRD < 1.0% | 46 | 35 | 75 | 75 |

| 1.0% ≤ MRD < 10.0% | 27 | 21 | 37 | 38 |

| MRD ≥ 10% | 8 | 3 | 21 | 19 |

| Indeterminate | 17 | 15 | 16 | 13 |

Abbreviations: DC, dexamethasone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen; DH, dexamethasone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen; MRD, minimal residual disease; PC, prednisone plus Capizzi escalating-dose methotrexate regimen; PH, prednisone plus high-dose methotrexate regimen.

Footnotes

Listen to the podcast by Dr Inaba at www.jco.org/podcasts

Supported by Children’s Oncology Group Chairs Operations grants U10 CA98543 and U10 CA180886 and Children’s Oncology Group Statistics and Data Center grants U10 CA098413 and U10 CA180899.

Presented at the 2011 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, June 3-7, 2011.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Eric C. Larsen, Meenakshi Devidas, Wanda L. Salzer, Mignon L. Loh, Leonard A. Mattano Jr, Catherine Cole, Alisa Eicher, Maureen Haugan, Mark Sorenson, Julie M. Gastier-Foster, Naomi J. Winick, Stephen P. Hunger, William L. Carroll

Collection and assembly of data: Eric C. Larsen, Meenakshi Devidas, Wanda L. Salzer, Elizabeth A. Raetz, Mignon L. Loh, Leonard A. Mattano Jr, Nyla A. Heerema, Andrew A. Carroll, Julie M. Gastier-Foster, Michael J. Borowitz, Brent L. Wood, Naomi J. Winick, Stephen P. Hunger, William L. Carroll

Data analysis and interpretation: Eric C. Larsen, Meenakshi Devidas, Si Chen, Wanda L. Salzer, Elizabeth A. Raetz, Mignon L. Loh, Andrew A. Carroll, Julie M. Gastier-Foster, Brent L. Wood, Cheryl L. Willman, Naomi J. Winick, Stephen P. Hunger, William L. Carroll

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dexamethasone and High-Dose Methotrexate Improve Outcome for Children and Young Adults With High-Risk B-Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Report From Children’s Oncology Group Study AALL0232

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Eric C. Larsen

No relationship to disclose

Meenakshi Devidas

No relationship to disclose

Si Chen

No relationship to disclose

Wanda L. Salzer

No relationship to disclose

Elizabeth A. Raetz

No relationship to disclose

Mignon L. Loh

No relationship to disclose

Leonard A. Mattano Jr

Employment: Pfizer (I)

Stock or Other Ownership: Pfizer, Pfizer (I), Amgen, Amgen (I), Monsanto, Monsanto (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Mylan, Novartis, Celldex

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer, Mylan

Catherine Cole

No relationship to disclose

Alisa Eicher

No relationship to disclose

Maureen Haugan

No relationship to disclose

Mark Sorenson

No relationship to disclose

Nyla A. Heerema

No relationship to disclose

Andrew A. Carroll

No relationship to disclose

Julie M. Gastier-Foster

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Michael J. Borowitz

Consulting or Advisory Role: HTG Molecular Diagnostics

Research Funding: Becton Dickinson, Amgen, MedImmune, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Brent L. Wood

Honoraria: Amgen, Seattle Genetics

Cheryl L. Willman

No relationship to disclose

Naomi J. Winick

No relationship to disclose

Stephen P. Hunger

Stock or Other Ownership: Express Scripts, Amgen, Merck (I), Amgen (I), Pfizer (I)

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Sigma Tau Pharmaceuticals, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Coinventor on US patent 8,568,974, B2 Identification of Novel Subgroups of High-Risk Pediatric Precursor-B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Outcome Correlations and Diagnostic and Therapeutic Methods Related to Same. It has not been licensed, and there is no income.

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Amgen

William L. Carroll

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith M, Arthur D, Camitta B, et al. Uniform approach to risk classification and treatment assignment for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:18–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1663–1669. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seibel NL, Steinherz PG, Sather HN, et al. Early postinduction intensification therapy improves survival for children and adolescents with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2008;111:2548–2555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-070342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nachman JB, Sather HN, Sensel MG, et al. Augmented post-induction therapy for children with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia and a slow response to initial therapy. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1663–1671. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pui CH, Carroll WL, Meshinchi S, et al. Biology, risk stratification, and therapy of pediatric acute leukemias: An update. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:551–565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vrooman LM, Stevenson KE, Supko JG, et al. Postinduction dexamethasone and individualized dosing of Escherichia coli L-asparaginase each improve outcome of children and adolescents with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results from a randomized study—Dana-Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium Protocol 00-01. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1202–1210. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teachey DT, Hunger SP. Predicting relapse risk in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2013;162:606–620. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Möricke A, Zimmermann M, Reiter A, et al. Long-term results of five consecutive trials in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia performed by the ALL-BFM study group from 1981 to 2000. Leukemia. 2010;24:265–284. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conter V, Aricò M, Basso G, et al. Long-term results of the Italian Association of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology (AIEOP) Studies 82, 87, 88, 91 and 95 for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:255–264. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilmer E, Suciu S, Ferster A, et al. Long-term results of three randomized trials (58831, 58832, 58881) in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A CLCG-EORTC report. Children Leukemia Cooperative Group. Leukemia14:2257-2566, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pui CH, Pei D, Sandlund JT, et al. Long-term results of St Jude Total Therapy Studies 11, 12, 13A, 13B, and 14 for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.252. 24:371-382, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vora A, Goulden N, Wade R, et al. Treatment reduction for children and young adults with low-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia defined by minimal residual disease (UKALL 2003): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:199–209. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borowitz MJ, Wood BL, Devidas M, et al. Prognostic significance of minimal residual disease in high risk B-ALL: A report from Children’s Oncology Group study AALL0232. Blood. 2015;126:964–971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-633685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaspers GJ, Veerman AJ, Popp-Snijders C, et al. Comparison of the antileukemic activity in vitro of dexamethasone and prednisolone in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27:114–121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199608)27:2<114::AID-MPO8>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito C, Evans WE, McNinch L, et al. Comparative cytotoxicity of dexamethasone and prednisolone in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2370–2376. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.8.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balis FM, Lester CM, Chrousos GP, et al. Differences in cerebrospinal fluid penetration of corticosteroids: Possible relationship to the prevention of meningeal leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:202–207. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverman LB, Gelber RD, Dalton VK, et al. Improved outcome for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results of Dana-Farber Consortium Protocol 91-01. Blood. 2001;97:1211–1218. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz CL, Thompson EB, Gelber RD, et al. Improved response with higher corticosteroid dose in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1040–1046. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bostrom BC, Sensel MR, Sather HN, et al. Dexamethasone versus prednisone and daily oral versus weekly intravenous mercaptopurine for patients with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Blood. 2003;101:3809–3817. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell CD, Richards SM, Kinsey SE, et al. Benefit of dexamethasone compared with prednisolone for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Results of the UK Medical Research Council ALL97 randomized trial. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:734–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurwitz CA, Silverman LB, Schorin MA, et al. Substituting dexamethasone for prednisone complicates remission induction in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2000;88:1964–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawedia JD, Kaste SC, Pei D, et al. Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacogenetic determinants of osteonecrosis in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2011;117:2340–2347, quiz 2556. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pound CM, Clark C, Ni A, et al. Corticosteroids, behavior, and quality of life in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia; a multicentered trial. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:517–523. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318257fdac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattano LA, Jr, Sather HN, Trigg ME, et al. Osteonecrosis as a complication of treating acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children: A report from the Children’s Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3262–3272. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reference deleted.

- 26.Schrappe M, Reiter A, Zimmermann M, et al. Long-term results of four consecutive trials in childhood ALL performed by the ALL-BFM study group from 1981 to 1995. Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster. Leukemia. 2000;14:2205–2222. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reference deleted.

- 28.Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: A Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood. 2008;111:5477–5485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. Analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray R. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merryman R, Stevenson KE, Gostic WJ, II, et al. Asparaginase-associated myelosuppression and effects on dosing of other chemotherapeutic agents in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:925–927. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen KB, Jusko WJ, Rasmussen M, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of prednisolone in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:465–473. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang L, Panetta JC, Cai X, et al. Asparaginase may influence dexamethasone pharmacokinetics in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1932–1939. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts KG, Li Y, Payne-Turner D, et al. Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.