Abstract

Over the past 30 years, a plethora of pathogenic mutations affecting enhancer regions and epigenetic regulators have been identified. Coupled with more recent genome‐wide association studies (GWAS) and epigenome‐wide association studies (EWAS) implicating major roles for regulatory mutations in disease, it is clear that epigenetic mechanisms represent important biomarkers for disease development and perhaps even therapeutic targets. Here, we discuss the diversity of disease‐causing mutations in enhancers and epigenetic regulators, with a particular focus on cancer. © 2015 The Authors. The Journal of Pathology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

Keywords: enhancer, epigenetics, chromatin, cancer, leukaemia, mutations

Introduction

The modern polymath Conrad H Waddington (1905–1975) was the first to coin the term ‘epigenetics’ to describe heritable changes in gene expression not caused by changes in the DNA sequence 1. Now, we know that the DNA is segregated into chromosomes inside the nucleus of each cell and that packaging proteins, called histones, associate with DNA to form the chromatin. Nucleosomes are the basic units of the chromatin and are formed by an octamer of histones (two copies of a tetramer; H2A, H2B, H3, and H4). If the DNA is well packed in these nucleosomes (condensed chromatin), genes will be switched off, whereas if the DNA is uncovered, as in decondensed chromatin, and thus more accessible to transcription factors (TFs), genes are more likely to be switched on. The level of compaction of these nucleosomes is influenced by chemical tags or ‘epigenetic modifications’, which associate with the histones or directly with the DNA. Just as each organism has its own unique DNA sequence, each cell type at each developmental stage has a distinctive epigenetic modification profile. As such, cellular commitment and differentiation are by definition an epigenetic phenomenon 2. Critically, the presence of these epigenetic modifications can be associated with changes in the environment (eg diet, stress, smoke inhalation, etc).

Genetic diseases are caused by a variety of mutations affecting the genes or the regulatory regions (promoters, enhancers, etc) controlling the expression of these genes, as well as by chromosomal alteration, such as translocations or aneuploidy. Enhancers are regulatory regions that increase the rate or the probability of transcription of a target gene. An enhancer may lie far away, upstream or downstream from the gene that it regulates or may be located in an intron of its target gene 3, 4. Mutations of enhancer sequences, and of the protein factors regulating enhancer function, contribute to a growing class of ‘enhanceropathies’ 5. α‐ and β‐thalassaemia are key examples of monogenic diseases which can be caused by the deletion of remote enhancers in certain patients 6.

Epigenetic alterations including DNA methylation and histone post‐translational modifications are catalysed by families of epigenetic regulators such as DNA and histone methyltransferases. Only five DNA modifications have been identified in eukaryotes, whereas approximately 130 specific histone modifications have been described, grouped into 16 classes 7, 8, 9. These histone modifications involve many different amino acids on each histone protein and have specific functions 7, 8. Epigenetic modifications can be generated by ‘writer’ enzymes and removed by ‘eraser’ enzymes. Specialized ‘reader’ proteins contain unique domains that specifically recognize these modifications and use them as docking sites 10. Some epigenetic regulators are required for transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, cell cycle, and differentiation – hence their important role in many cancers.

Multigenic diseases (eg cancer) result from the accumulation of mutations in genes such as oncogenes (gain‐of‐function mutations) and/or tumour suppressor genes (loss‐of‐function mutations). This causes a loss of coordination between proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells. Diseases involving mutations of epigenetic regulators have been recently described in a variety of solid tumours and blood malignancies 8. This has highlighted the importance of epigenetics in disease, but also implies that these diseases are genetic after all.

In this review, we will discuss the complexity of pathogenic mutations and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) affecting enhancer activity. Next, we will look at the importance of epigenetic signatures that are associated with diseases as biomarkers for disease development. We will then discuss the role that epigenetic regulator mutations play in disease and the interplay of these genetic mutations and pure epigenetic mutations. Although unique research advantages become available when studying different model organisms it is important to note the fundamental differences in the epigenetic regulation between different species, which we will discuss throughout this review.

The molecular basis of aberrant gene expression

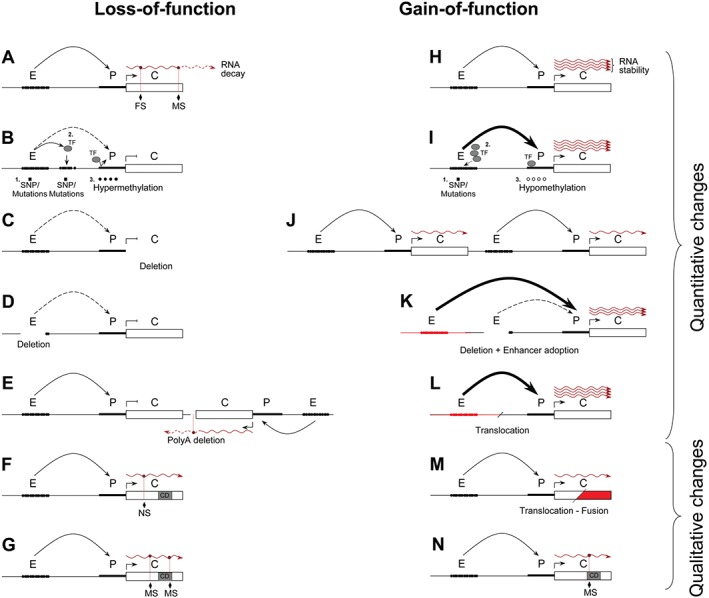

The effects of loss‐ and gain‐of‐function mutations can be quantitative or qualitative. These are summarized in Figure 1. The nature of a disease‐inducing mutation greatly influences the types of tests needed to diagnose and the therapeutic approaches used. A quantitative change directly causes an increase or a decrease in abundance of the final gene product. Quantitative changes in expression are relatively easily detected with classical and low‐cost techniques such as immunohistochemistry (IHC), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), colorimetric in situ hybridization (CISH), and real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) 11. Qualitative changes can alter the function of a mutated gene. Their detection may require more sophisticated and high‐cost sequencing techniques such as targeted exome sequencing or whole genome sequencing (which can now be achieved at a single cell level) 12, 13, 14. However, when a qualitative mutation occurs in a master regulator, this often influences the transcription levels of downstream target genes, which can be measured using quantitative means. For example, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) patients with MLL rearrangements (discussed below) have a distinct gene expression profile which distinguishes them from other ALL patients and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) patients 15.

Figure 1.

Molecular basis of genetic diseases. Effects of loss‐ and gain‐of‐function mutations affecting gene expression are quantitative and/or qualitative. (A) A missense mutation or a small insertion/deletion mutation (frameshift) in a coding sequence or at a PolyA signal often leads to abortive translation or RNA decay 162. (B) Reduction of chromosomal looping between the enhancer and the promoter might be due to (1) natural variant or mutation at the enhancer 163, (2) the presence of a new SNP forming a new enhancer/promoter region which titrates the remote enhancer activity 43, or (3) promoter or enhancer hypermethylation 164. (C) Deletion of the gene 165. (D) Deletion of the remote enhancer 166. (E) Deletion of the PolyA signal of a downstream and convergent gene, leading to the production of antisense RNA 167. (F) Nonsense mutation adding a new premature stop codon producing a truncated protein 168. Note that truncated proteins may also have a gain‐of‐function activity 169. (G) Missense mutation affecting the non‐enzymatic activity or abolishing the catalytic domain of an enzyme 104. (H) Normal rate of transcription, but increased accumulation of final gene product due to the presence of an RNA 170 or a protein 171 stabilizing molecule. (I) Increased enhancer activity due to (1) enhancer mutation 25, (2) overexpression of a transcription factor 172, or (3) promoter hypomethylation 173. (J) An increase in gene copy number, including regulatory regions 174. (K) Large genomic deletion bringing a strong (but irrelevant) enhancer closer 175. (L) Translocation with a heterologous chromosome (red) creating a fusion locus with a new strong enhancer regulating an illegitimate gene 176. (M) Translocation with a heterologous chromosome (red) producing a fusion gene, with increased biological activity 96. (N) Missense mutation improving enzymatic activity 81. E, enhancer; P, promoter; C, coding region; TF, transcription factor; CD, catalytic domain; MS, missense mutation; NS, nonsense mutation; FS, frameshift mutation. Dashed curved arrows represent impaired enhancer–promoter interaction (looping); thin curved arrows, normal looping; and thick curved arrows, strong looping. Wavy red lines indicate mRNA.

Transcriptional enhancers and diseases

Loss‐of‐function enhancer mutations

Thirty years ago, human genetics studies pioneered the identification of functional remote regulatory elements in patients with α‐ and β‐thalassaemia (reviewed in ref 6). In most cases, a deletion removing a globin gene causes its down‐regulation (Figure 1C). However, in rare cases, the genes (including their promoters) remain intact but the deletion of one (or several) remote enhancer(s) causes their down‐regulation (Figure 1D). There are many other instances in which enhancer deletions have been shown to cause pathologies. Deletions in enhancers of FOXL2 16, POU3F4 17, SOST 18, 19, and SOX10 20, 21 have been linked to blepharophimosis syndrome, X‐linked deafness type 3, van Buchem disease, and Waardenburg syndrome type 4, respectively.

Deletions are not the only mutations affecting enhancer function. Although the exact mechanism of pathogenesis is currently unclear, a variety of SNPs can affect enhancer activity by changing TF binding affinity and/or specificity (Figures 1B and 1I). Hirschsprung disease (HSCR), a multigenic, heritable disorder affecting the ganglion cells in the large intestine or gastrointestinal tract, is an example. Less than 30% of HSCR patients have identified mutations in the coding sequence of candidate genes, such as RET (encoding a tyrosine kinase receptor), but SNPs within the enhancers of either the SOX10 (a transcription factor regulating RET expression) or the RET genes have been identified in other patients 20, 21, 22. SNPs in SOX10 enhancers in isolated HSCR and Waardenburg syndrome type 4 patients (a rare condition characterized by deafness and pigmentation anomalies) have been shown to significantly reduce Sox10 expression, also leading to down‐regulation of RET expression 20, 21. A single base‐pair change in one of the RET enhancers is also overrepresented in affected populations 22. This SNP reduces the activity of the enhancer in gene reporter assays compared with the normal allele, apparently by disruption of a SOX10 binding site which subsequently reduces RET expression 23.

Gain‐of‐function enhancer mutations

One example of gain‐of‐function pathogenic mutations identified in enhancer sequences is in patients with preaxial polydactyly 24, 25. Point mutations in the long‐distant, limb‐specific enhancer for sonic hedgehog (SHH) can cause ectopic expression of this gene, leading to the formation of extra digits in human and other animal patients 26.

More recently, high‐throughput sequencing technology has allowed GWAS to identify a large number of candidate SNPs associated with diseases 27, 28. A number of independent GWAS have identified distinct breast, prostate, and colon cancer risk regions in the 8q24 region, each enriched with histone modifications that are characteristic of enhancers 29. Within these enhancer regions, various SNPs have been identified and that predispose susceptibility to certain cancer types. For example, the prostate cancer risk allele rs11986220 exhibits stronger binding to the TF forkhead box protein A1 (FOXA1) 30. This increased binding of FOXA1 can facilitate the recruitment of FOXA1‐dependent androgen receptor, which is associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer 31.

Using chromatin conformation capture (3C) technology 32, a number of risk regions in the 8q24 region have been shown to form large chromosomal loops to the promoter of the MYC oncogene 29, 30, 33, 34, 35, 36. However, none of these studies has successfully demonstrated a correlation between the occurrence of these SNPs and an increase in downstream MYC expression. MYC expression may be enhanced by these SNPs, but only at specific times during tumourigenesis, or only in a particular subset of cells (eg cancer stem cells). The prostate cancer risk locus at 8q24 also forms contacts with multiple other genomic loci, sometimes in a cell‐type‐specific manner, suggesting that the pathogenic mechanisms of identified susceptibility alleles may be MYC‐independent 37. Of note, a number of susceptibility alleles in the 8q24 region have been shown to increase the expression of the oncogene PVT1 35.

In cells of the same type but from different individuals, SNPs associated with disease (quantitative trait loci; QTL) affect the variability of TF binding and therefore can lead to changes in the associated chromatin state. This would cause local epigenetic variability between individuals. Recently, Waszak et al and Grubert et al found that such local chromatin changes due to distinct genetic variation at TF binding sites are also influenced by the state of other regulatory elements (local, but also hundreds of kilobases away), and thus affect large genomic compartments forming regulatory units, called variable chromatin modules (VCMs) 38. Variability within each of these VCMs is mediated by the spatial chromatin interactions 39, which may affect the expression of several genes. This might also suggest that very few apparent ‘epi‐mutations’ might be wholly distinguishable from DNA sequence changes.

Epigenetic signatures of disease

True epi‐mutations (ie epigenetic modifications differentially represented in a diseased versus healthy population) represent important biomarkers 40, which can be exploited for patient stratification 41, 42, identification of candidate pathways in disease 43, 44, and potential targets for novel epigenetic editing therapies 45. Disease‐specific DNA methylomes have been identified in patients with active ovarian cancer 46, distinct forms of AML 47, colorectal cancer 48, and other diseases. Thousands of loci have been found to be differentially enriched for epigenetic signatures marking enhancers (monomethylation of lysine 4 at histone H3) in a given colorectal cancer cell sample when compared with normal crypt cells 49.

EWAS are now underway to identify epi‐mutations associated with disease 50. These studies are focused mainly on changes of DNA methylation (methylation quantitative trait loci – methQTLs) as this is more feasible than histone modification analyses. EWAS have already identified differentially methylated genomic regions that may mediate the epigenetic risk of rheumatoid arthritis 51 and that may be induced by regular smoking 52, 53. Intrinsic challenges in epigenetic analyses include the epigenetic variance between different cell types and different developmental stages. New study design and analysis techniques are now being developed to help circumvent these issues 54, 55. However, epigenetic variance between single cells of the same type and development stage may also cause difficulty in separating true signals from noise 50, 56.

Epigenetic regulation in disease

Regulators of DNA modifications

Five different DNA modifications have been described in eukaryotes. The methylation of number 5 carbon on cytosine residues (5mC) in CpG dinucleotides was the first described covalent modification of DNA 57. 5mC oxidative intermediates such as 5‐hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5‐formylcytosine (5fC), and 5‐carboxylcytosine (5caC) are other metabolites found at CpGs 8. Recently, a new modification of eukaryote DNA, N6‐methyladenine, was described 9.

In vertebrates, DNA regions with a high density of CpG dinucleotides form CpG islands. These are short (∼1000 bp) interspersed CpG‐rich and predominantly unmethylated DNA sequences 58. They are found in all housekeeping genes and in a proportion of tissue‐specific and developmental regulator genes. Although DNA methylation is well documented in vertebrates, it is less well understood in other organisms. In fact, the most commonly studied invertebrate model organisms, the fly Drosophila melanogaster and the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, and also the fungus Saccharomyces cereviceae all lack DNA methylation 58. However, in some insects, such as the Hymenoptera honey bee (Apis mellifera, discussed later), DNA methylation occurs but is primarily found in gene bodies affecting the splicing of ubiquitously expressed genes 59. In mammals, however, DNA methylation appears in intergenic regions, where it can, for example, impede TF binding at promoter regions 58 (Figure 1B).

DNA modifications and disease

Methylated CpG dinucleotides are more sensitive to mutation by deamination to TpG or CpA 60, and thus represent a key example where epi‐mutations can generate genetic mutations. Early studies found that CpG islands are underrepresented in the rodent compared with the human genome, as they have been eroded during evolution 61, 62. These studies suggest that CpG dinucleotides within the mouse CpG islands were accidentally methylated and mutated to TpG or CpA during evolution. This could have dramatic consequences when studying a mouse model where the gene of interest might be regulated differently compared with its human orthologue. For example, the human α‐globin gene is regulated by Polycomb group repressive complexes during differentiation, whereas the mouse α‐globin gene is not 6. This led to the development of a humanized mouse model for the in vivo study of the regulation of the human α‐globin gene expression 63.

Cytosine is methylated by a family of enzymes called de novo (DNMT1) and maintenance (DNMT3) DNA methyltransferases. One of the DNMTs, DNMT3A, is inactivated in related haematological malignancies 64 such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) 65 and AML 66. Around 30% of MDS cases progress to acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) 67. Interestingly, loss‐of‐function mutations of DNMT3A that do not affect its catalytic domain disrupt the formation of a tetramer with another protein, DNMT3L 68, 69. These mutations have a dominant‐negative effect, which prevents the wild‐type protein from functioning normally 68, 69. The ten–eleven translocation (TET 1–3) family of proteins are the mammalian DNA hydroxylases responsible for catalytically converting 5mC to 5hmC 70. Loss‐of‐function of TET2 and DNMT3A seems to be a primary event during leukaemogenesis 71. Disruption of normal methylation patterns in colorectal cancer cells correlates with underexpression of tumour suppressor genes (Figure 1B) and overexpression of oncogenes (Figure 1I) 48.

Regulators of histone modifications

The opposing effects of the Polycomb group (PcG, associated with gene repression) and Trithorax group (associated with gene activation) remodelling proteins regulate many cellular decisions in stem cell biology, development, and cancer. Histone H3 trimethylated at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) is generated by Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) and involves a ‘reader’, EED, which recognizes a pre‐existing modified histone (H3K27me3), and a ‘writer’, methyltransferase EZH2, which modifies the histones nearby 72. Histone H3K27 methylation is removed by ‘erasers’, which prevent the maintenance/propagation of this modification. Three histone demethylases, UTX (KDM2A), UTY, and JMJD3 (KDM2B), have been reported to remove H3K27me3 73, 74. Disease‐causing mutations may affect the histone genes themselves, or the enzymes (readers, writers, and erasers) regulating the post‐translational modifications of their products.

In contrast to DNA methylation, some histone modifications and their functions are conserved from yeast to human (eg H3K4me3), but the families of enzymes catalysing the addition or removal of these modifications have expanded during evolution. For example, one single protein catalyses the deposition of H3K4me3 in yeast (Set1, part of the COMPASS complex), whereas in mammals up to six (SET1B, SET1B, MLL1, MLL2, MLL3, and MLL4) enzymes have been reported 75. This expansion follows the shift from unicellular to multicellular organisms, although the expression of each enzyme is not necessarily tissue‐specific, which explains why redundancy is often observed. PcGs, involved in the deposition of histone marks (H2AK118ub for PRC1 and H3K27me3 for PRC2) associated with transcriptional repression, were first identified in Drosophila melanogaster 76. The mechanism of PcG recruitment in Drosophila is different as these are recruited to specific DNA sequences called polycomb repressive elements 76, whereas in mammals these complexes are recruited by CpG islands 77, 78.

Histone modification regulators in disease

EZH2 is the most frequently mutated PRC2 component in cancer. However, both gain‐of‐function 79 and loss‐of‐function 80, 81, 82, 83 mutations have been observed in lymphoma and leukaemia, respectively (reviewed in refs 84 and 85). Certain evidence suggests that genomic loss or hypoxia‐induced down‐regulation of microRNA‐101 (miR‐101) is the cause of EZH2 overexpression in many solid tumours 86, 87, 88, 89.

As epigenetic regulators target vast numbers of genes influencing their transcription rates, it is unsurprising that both inactivation and hyperactivation of these enzymes can lead to disease, depending on the tissue type and the developmental stage. Other genes involved in cancer have also been found to have opposing roles in different tissues. This is the case for NOTCH1, encoding a transmembrane receptor, which has been described as an oncogene in leukaemia 90 and a tumour suppressor gene in solid tumours 91, 92. Mutations affecting protein–protein interactions may explain these opposing effects. For example, certain missense mutations of the tumour suppressor p53 (TP53) can exhibit oncogenic activities with a dominant‐negative effect achieved by the oligomerization of the mutant and the wild‐type proteins 93, 94.

Chromosomal translocations, originally identified in leukaemic cells, can also affect epigenetic regulators by creating novel fusion proteins, with different functions compared with the wild‐type protein (Figure 1 M). Almost all leukaemias and lymphomas harbour translocations (reviewed in ref 95). Chromosomal rearrangements affecting the Trithorax group MLL gene occur in over 70% of infant leukaemia cases 96. The resulting fusion proteins cause overexpression of a number of different target genes despite the fact that most of these rearrangements cause a deletion of the catalytic SET domain of MLL 96, 97. One mechanism of this deviant gene activation by MLL fusion proteins is the aberrant recruitment of DOT1L, a H3K79 histone methyltransferase, associated with transcriptional elongation 96, 98, 99, 100, 101.

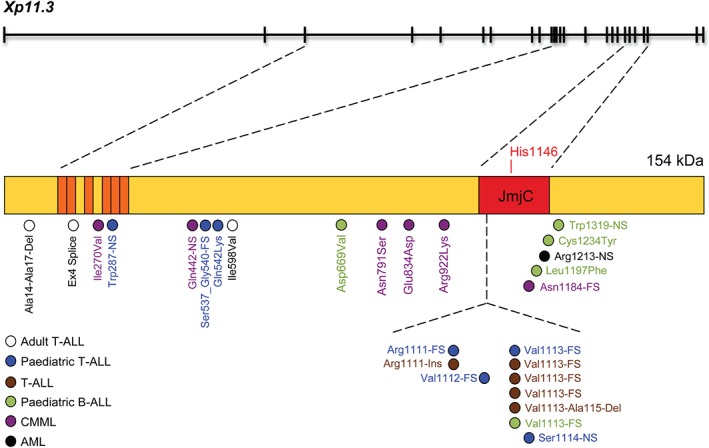

Sequence conservation is high in the Jumonji C (JmjC) catalytic domain amongst the histone H3K27 demethylases, UTX (KDM2A), UTY, and JMJD3 (KDM2B) (Figure 2) 102, 103. Other domains involved in protein–protein interactions may be important for substrate specificity and segregate the function or targets of these enzymes. For example, in T‐ALL, UTX functions as a tumour suppressor, whereas JMJD3 works as an oncoprotein, despite their common enzymatic activity 104. Histone H3K27 demethylases have several functions besides their enzymatic activities, such as nucleosome depletion 105 or transcription elongation 106. Mutations seen in cancer may cause quantitative changes to overall expression, or qualitative changes that enhance or repress specific domain functions. Figure 2 depicts the UTX gene and its inactivating mutations found in T‐ and B‐cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T‐ALL and B‐ALL), and also in chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML) 107. From this diagram it is not clear if the tumour suppressor activity of UTX depends on its demethylase activity as some mutations (affecting the TRP domain) leave the catalytic domain intact. Also, the sequence conservation within this family of enzymes makes it difficult to design specific inhibitors against each individual H3K27 demethylase (eg cross‐reactivity of GSK‐J3/GSK‐J4 for JMJD3 and UTX) 108. Moreover, epigenetic regulators do not target just histones, but other proteins also 109.

Figure 2.

Mutations of the UTX gene in leukaemia. The UTX (ubiquitously transcribed X chromosome tetratricopeptide repeat protein) gene contains 29 exons (black boxes) that encode a 1401‐amino acid (aa) protein with a molecular weight of 154 kDa. The amino‐terminal region shows six tetratricopeptide repeat (TRP) domains (indicated in orange) and one JmjC domain (aa 1095 to 1258) which contains a catalytic histidine (His1146) (indicated in red). Blue circles depict frameshift mutations (FS) in the JmjC domain in paediatric T‐ALL 177, and white circles depict an in‐frame deletion, a splice acceptor site mutation, and a missense mutation in adult T‐ALL 104. Additional T‐ALL patients have been identified with mutations (brown circles) in the same hotspot region of the JmjC domain 120. These include three frameshift (Val1113‐FS) and two in‐frame insertions/deletions. Other mutations have been found in paediatric B‐ALL (green circles), with one frameshift, two missense, and one nonsense mutations in the JmjC domain, and an additional missense mutation between the TRP and JmjC domains 178. Other mutations have been found in CMML (purple circles) 107, 179 and AML (black circle) patients. A deletion was also detected in a patient with MDS 180. In patients with an inactivated catalytic domain, the mutant protein may have a dominant‐negative activity as the protein‐interacting TRP domain at the N‐terminus is preserved. This may allow the mutant protein to still interact with other proteins, and thus compete with the wild‐type protein (UTX for female and UTY for male) expressed by the other chromosome. Note that this gene also produces many splice variants.

Histone variants in disease

As described above, histones are the building blocks of nucleosomes, which are involved in chromatin packaging. Many histone variants exist, expanding the traditional roles of histones to include mechanisms such as DNA repair and maintenance of genomic stability 110. Histone H3.3 is one such variant, which is essential for mouse development, genomic stability, and normal heterochromatin function 111. The first mutations linking human disease to histone variants were identified in the genes H3F3A and HIST1H3B encoding H3.3 and canonical H3.1, respectively 112, 113. These recurrent gain‐of‐function mutations, affecting residues at or close to the position where H3K27me3 occurs, have been found in approximately 50% of paediatric high‐grade gliomas 112, 113. One of these mutations, K27M in H3.3, is a dominant‐negative inhibitor of H3K27me2/3 deposition, reducing global H3K27me2/3 on wild‐type H3.1 and H3.3 histones 114, 115, 116, 117. H3.3‐K27M prevents H3K27me2/3 deposition through direct interaction with, and inhibition of, PRC2 components 115, 116. The global reduction of H3K27me3 is concurrent with changes in DNA methylation patterns specific to tumours from H3.3‐K27M patients, leading to distinct changes in gene expression 115.

Conclusion

To date, 125 genes with driver mutations for cancer have been discovered, and nearly half of them encode epigenetic regulators 118. The high frequency of these mutations reflects the critical role of epigenetics in disease. Disease‐specific epigenome signatures suggest that epigenetics plays an important role even in cancers where epigenetic regulators have not been mutated 49. These changes in the epigenetic landscape are strongly correlated with transcriptional changes in cancer driver genes 48. Importantly, the potency of these epigenetic regulators makes them excellent therapeutic targets; modulation of their activity by use of inhibitors could potentially reset the epigenome to a ‘normal’ state. For instance, inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases such as azacitidine (5‐azacytidine) and decitabine (5‐aza‐deoxycytidine; DAC) lead to DNA hypomethylation and have shown promising results in the treatment of MDS 119. Even when a tumour suppressor gene is missing, targeted inhibition of its antagonist can potentially reset epigenetic imbalances and mediate beneficial responses 120. To illustrate, loss‐of‐function of a H3K27 demethylase creates an imbalanced preponderance of H3K27me3 modifications in a cell. These effects could be minimized by the use of a large number of promising EZH2 inhibitors (DZNep 121, EI1 122, GSK126 123, 124, GSK926 125, GSK343 124, EPZ005687 126, CPI‐169 127, UNC1999 128, 129, and others 130). A list of current inhibitors under development for all epigenetic regulators is beyond the scope of this review, but all the current epigenetic therapies and their relevance to leukaemia can be found elsewhere 131. We must still also consider that during cancer progression, cells accumulate mutations that generate genetic and/or epigenetically distinct subclones displaying both genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity 132. Such heterogeneity presents another challenge to treatment.

The question still remains: is a genetic mutation always required, or are pure epi‐mutations sufficient to cause a disease? Studies across many species have shown how environmental factors can directly influence phenotypes through epigenetic mechanisms. For example, queen honey bees are fed with royal jelly throughout their lifetime, with effects involving DNA methylation changes 133, gene expression changes 134, and phenotypic differences including increases in size and longevity 135, when compared with their worker bee siblings (reviewed in ref 136). Interestingly, the royal jelly contains a histone deacetylase inhibitor 137, 138 that significantly increases lifespan in Drosophila 135. In humans, the study of monozygotic twins (genetically identical individuals) with discordant diseases represents an excellent system with which to identify environmental causes of epi‐mutations because potential confounders (genetic factors, age, gender, maternal effects, cohort effects, etc) can be controlled 139. For example, studies of monozygotic twins showed that epigenetic differences arise during their lifetimes 140, and that twins rarely develop the same disease 141, 142. Although different somatic mutations can accumulate over time in these individuals, environmental factors causing epigenetic changes may be important in disease. A recent study on a pair of identical twins discordant for common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) revealed that differential DNA methylation was associated with deregulation of genes involved in maturation of B‐cells, but without considering potential somatic mutations that may have occurred during adult life 143. Overall, most discordant monozygotic twin studies seem to involve autoimmune, psychiatric, and neurological diseases, but also different types of cancer 139. The importance of the environment during adulthood has been shown in a recent EWAS, which has identified differentially methylated CpGs in smokers versus non‐smokers that could potentially be associated with increased breast cancer risk 53.

Epigenetic modifications also vary during lifespan and between different tissues, making disease‐causing epi‐mutations difficult to separate from normal variation. It is therefore important to ensure that age‐ and tissue‐matched reference epigenomes are available for comparison. In some cases, epi‐mutations might be inherited through the germline, suggesting a possible existence of purely epigenetically transmissible diseases. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance studies have been described in plants 144, invertebrates 145, and mammals 146, 147, usually using changes of diet conditions as a model (reviewed in refs 148 and 149). However, these studies are mostly descriptive and require more mechanistic insights 150.

SNPs in enhancers and epi‐mutations have been strongly correlated with disease risk in many cases 51, 53, 151, 152. However, correlation does not equate to causation. Although effects of mutations in coding sequences are relatively easy to investigate, SNPs located in enhancer sequences, and associated with disease, are more difficult to validate. For example, the previously GWAS‐identified SNPs in obese patients are located in the first intron of the FTO gene. Smemo et al recently published that this intron acts as an enhancer, not for the FTO gene but for another gene, IRX3, located 500 kb away, thus revealing the role of IRX3 (and not FTO) in obesity 153. Many excellent studies mentioned in this review and beyond have aimed to dissect the mechanism by which an enhancer SNP or deletion may lead to disease, but the true ‘gold standard’ technique would be to replicate the mutation in vivo and examine the results. Classical gene targeting techniques have achieved this in some cases 154 but recently described genetic editing tools could make a rigorous characterization of these mutations more widely achievable 155. Similarly, the use of targeted epigenetic editing techniques 156, 157 will expand the ability of epigeneticists to investigate the phenotypes of epi‐mutations.

These recently described genome and epigenetic editing techniques could be used in the clinic to completely reset a disease‐causing mutation in a patient. Certainly, many studies are already underway investigating the use of genetic editing techniques in treating diseases such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) 158 and X‐linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID‐XI) 159 (reviewed in ref 160). Epigenetic editing, although in its infancy, is proving extremely effective and could potentially be used as a means of disease treatment 45, 157. However, particularly in cancer treatment, where mutation load can reach into the hundreds in certain tumours 118, it would be extremely difficult to correct every driver mutation in every cell. Meanwhile, the debate continues over the ethical use of genetic editing techniques as a form of disease treatment for humans 161. The use of inhibitor drugs in a clinical setting to target the effects of these mutations still remains a much more realistic option for the treatment of many cancers. As some of the proteins targeted by these drugs can have opposing effects (oncogene versus tumour suppressor) in cells from the same tissue, it is important to understand the biology of the mutations and the function of these proteins in each lineage to identify the tumourigenic pathways that they may regulate.

Author contribution statement

AJB and DV wrote the manuscript together.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Kamil Kranc, Duncan Sproul, and Paul Digard for their comments during the preparation of this manuscript. We apologize to those whose publications we were unable to cite due to space limitations. The Vernimmen laboratory benefits from funding by the British Society for Haematology (BSH) and the Roslin Foundation. Douglas Vernimmen is supported by a Chancellor's Fellowship at The University of Edinburgh and The Roslin Institute receives Institute Strategic Grant funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC).

No conflicts of interest were declared.

References

- 1. Slack JM. Conrad Hal Waddington: the last Renaissance biologist? Nature Rev Genet 2002; 3 : 889–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldberg AD, Allis CD, Bernstein E. Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell 2007; 128: 635‐638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim TK, Shiekhattar R. Architectural and functional commonalities between enhancers and promoters. Cell 2015; 162: 948–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andersson R, Sandelin A, Danko CG. A unified architecture of transcriptional regulatory elements. Trends Genet 2015; 31: 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith E, Shilatifard A. Enhancer biology and enhanceropathies. Nature Struct Mol Biol 2014; 21: 210–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vernimmen D. Uncovering enhancer functions using the alpha‐globin locus. PLoS Genet 2014; 10: e1004668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tan M, Luo H, Lee S, et al. Identification of 67 histone marks and histone lysine crotonylation as a new type of histone modification. Cell 2011; 146: 1016–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell 2012; 150: 12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Breiling A, Lyko F. Epigenetic regulatory functions of DNA modifications: 5‐methylcytosine and beyond. Epigenetics Chromatin 2015; 8: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tarakhovsky A. Tools and landscapes of epigenetics. Nature Immunol 2010; 11: 565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maire CL, Ligon KL. Molecular pathologic diagnosis of epidermal growth factor receptor. Neuro Oncol 2014; 16 ( Suppl 8 ):viii1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saadatpour A, Guo G, Orkin SH, et al. Characterizing heterogeneity in leukemic cells using single‐cell gene expression analysis. Genome Biol 2014; 15: 525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gawad C, Koh W, Quake SR. Dissecting the clonal origins of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia by single‐cell genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111: 17947–17952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paguirigan AL, Smith J, Meshinchi S, et al. Single‐cell genotyping demonstrates complex clonal diversity in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:281re282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Armstrong SA, Staunton JE, Silverman LB, et al. MLL translocations specify a distinct gene expression profile that distinguishes a unique leukemia. Nature Genet 2002; 30: 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. D'Haene B, Attanasio C, Beysen D, et al. Disease‐causing 7.4 kb cis‐regulatory deletion disrupting conserved non‐coding sequences and their interaction with the FOXL2 promotor: implications for mutation screening. PLoS Genet 2009; 5: e1000522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Naranjo S, Voesenek K, de la Calle‐Mustienes E, et al. Multiple enhancers located in a 1‐Mb region upstream of POU3F4 promote expression during inner ear development and may be required for hearing. Hum Genet 2010; 128: 411–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Balemans W, Patel N, Ebeling M, et al. Identification of a 52 kb deletion downstream of the SOST gene in patients with van Buchem disease. J Med Genet 2002; 39: 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Loots GG, Kneissel M, Keller H, et al. Genomic deletion of a long‐range bone enhancer misregulates sclerostin in Van Buchem disease. Genome Res 2005; 15: 928–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bondurand N, Fouquet V, Baral V, et al. Alu‐mediated deletion of SOX10 regulatory elements in Waardenburg syndrome type 4. Eur J Hum Genet 2012; 20: 990–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lecerf L, Kavo A, Ruiz‐Ferrer M, et al. An impairment of long distance SOX10 regulatory elements underlies isolated Hirschsprung disease. Hum Mutat 2014; 35: 303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Emison ES, McCallion AS, Kashuk CS, et al. A common sex‐dependent mutation in a RET enhancer underlies Hirschsprung disease risk. Nature 2005; 434: 857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emison ES, Garcia‐Barcelo M, Grice EA, et al. Differential contributions of rare and common, coding and noncoding Ret mutations to multifactorial Hirschsprung disease liability. Am J Hum Genet 2010; 87: 60–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lettice LA, Heaney SJ, Purdie LA, et al. A long‐range Shh enhancer regulates expression in the developing limb and fin and is associated with preaxial polydactyly. Hum Mol Genet 2003; 12: 1725–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lettice LA, Hill AE, Devenney PS, et al. Point mutations in a distant sonic hedgehog cis‐regulator generate a variable regulatory output responsible for preaxial polydactyly. Hum Mol Genet 2008; 17: 978–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson E, Peluso S, Lettice LA, et al. Human limb abnormalities caused by disruption of hedgehog signaling. Trends Genet 2012; 28: 364–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hindorff LA, Sethupathy P, Junkins HA, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome‐wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 9362–9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Manolio TA. Genomewide association studies and assessment of the risk of disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ahmadiyeh N, Pomerantz MM, Grisanzio C, et al. 8q24 prostate, breast, and colon cancer risk loci show tissue‐specific long‐range interaction with MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 9742–9746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jia L, Landan G, Pomerantz M, et al. Functional enhancers at the gene‐poor 8q24 cancer‐linked locus. PLoS Genet 2009; 5: e1000597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sahu B, Laakso M, Ovaska K, et al. Dual role of FoxA1 in androgen receptor binding to chromatin, androgen signalling and prostate cancer. EMBO J 2011; 30: 3962–3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. de Wit E, de Laat W. A decade of 3C technologies: insights into nuclear organization. Genes Dev 2012; 26: 11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tuupanen S, Turunen M, Lehtonen R, et al. The common colorectal cancer predisposition SNP rs6983267 at chromosome 8q24 confers potential to enhanced Wnt signaling. Nature Genet 2009; 41: 885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pomerantz MM, Ahmadiyeh N, Jia L, et al. The 8q24 cancer risk variant rs6983267 shows long‐range interaction with MYC in colorectal cancer. Nature Genet 2009; 41: 882–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meyer KB, Maia AT, O'Reilly M , et al. A functional variant at a prostate cancer predisposition locus at 8q24 is associated with PVT1 expression. PLoS Genet 2011; 7: e1002165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yochum GS. Multiple Wnt/ss‐catenin responsive enhancers align with the MYC promoter through long‐range chromatin loops. PLoS One 2011; 6: e18966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Du M, Yuan T, Schilter KF, et al. Prostate cancer risk locus at 8q24 as a regulatory hub by physical interactions with multiple genomic loci across the genome. Hum Mol Genet 2014;24: 154–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Waszak SM, Delaneau O, Gschwind AR, et al. Population variation and genetic control of modular chromatin architecture in humans. Cell 2015; 162: 1039–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grubert F, Zaugg JB, Kasowski M, et al. Genetic control of chromatin states in humans involves local and distal chromosomal interactions. Cell 2015; 162: 1051–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Heyn H, Carmona FJ, Gomez A, et al. DNA methylation profiling in breast cancer discordant identical twins identifies DOK7 as novel epigenetic biomarker. Carcinogenesis 2013; 34: 102–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mohammad HP, Smitheman KN, Kamat CD , et al. A DNA hypomethylation signature predicts antitumor activity of LSD1 inhibitors in SCLC. Cancer Cell 2015; 28: 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stone A, Zotenko E, Locke WJ, et al. DNA methylation of oestrogen‐regulated enhancers defines endocrine sensitivity in breast cancer. Nature Commun 2015; 6: 7758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. De Gobbi M, Viprakasit V, Hughes JR, et al. A regulatory SNP causes a human genetic disease by creating a new transcriptional promoter. Science 2006; 312: 1215–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Trynka G, Sandor C, Han B, et al. Chromatin marks identify critical cell types for fine mapping complex trait variants. Nature Genet 2013; 45: 124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rivenbark AG, Stolzenburg S, Beltran AS, et al. Epigenetic reprogramming of cancer cells via targeted DNA methylation. Epigenetics 2012; 7: 350–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Teschendorff AE, Menon U, Gentry‐Maharaj A, et al. An epigenetic signature in peripheral blood predicts active ovarian cancer. PLoS One 2009; 4: e8274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Figueroa ME, Lugthart S, Li Y, et al. DNA methylation signatures identify biologically distinct subtypes in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2010; 17: 13–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Irizarry RA, Ladd‐Acosta C, Wen B, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo‐ and hypermethylation at conserved tissue‐specific CpG island shores. Nature Genet 2009; 41: 178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Akhtar‐Zaidi B, Cowper‐Sal‐lari R, Corradin O, et al. Epigenomic enhancer profiling defines a signature of colon cancer. Science 2012; 336: 736–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rakyan VK, Down TA, Balding DJ, et al. Epigenome‐wide association studies for common human diseases. Nature Rev Genet 2011; 12: 529–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu Y, Aryee MJ, Padyukov L, et al. Epigenome‐wide association data implicate DNA methylation as an intermediary of genetic risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Nature Biotechnol 2013; 31: 142–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Breitling LP, Yang R, Korn B, et al. Tobacco‐smoking‐related differential DNA methylation: 27 K discovery and replication. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 88: 450–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shenker NS, Polidoro S, van Veldhoven K, et al. Epigenome‐wide association study in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC‐Turin) identifies novel genetic loci associated with smoking. Hum Mol Genet 2013; 22: 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Michels KB, Binder AM, Dedeurwaerder S, et al. Recommendations for the design and analysis of epigenome‐wide association studies. Nature Methods 2013; 10: 949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zou J, Lippert C, Heckerman D, et al. Epigenome‐wide association studies without the need for cell‐type composition. Nature Methods 2014; 11: 309–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Smallwood SA, Lee HJ, Angermueller C, et al. Single‐cell genome‐wide bisulfite sequencing for assessing epigenetic heterogeneity. Nature Methods 2014; 11: 817–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Johnson TB, Coghill RD. Researches on pyrimidines. C111. The discovery of 5‐methyl‐cytosine in tuberculinic acid, the nucleic acid of the tubercle bacillus. J Am Chem Soc 1925; 47: 7. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Deaton AM, Bird A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev 2011; 25: 1010–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Glastad KM, Hunt BG, Yi SV, et al. DNA methylation in insects: on the brink of the epigenomic era. Insect Mol Biol 2011;20: 553–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Roberts SA, Gordenin DA. Hypermutation in human cancer genomes: footprints and mechanisms. Nature Rev Cancer 2014; 14: 786–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Matsuo K, Clay O, Takahashi T, et al. Evidence for erosion of mouse CpG islands during mammalian evolution. Somat Cell Mol Genet 1993; 19: 543–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Antequera F, Bird A. Number of CpG islands and genes in human and mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90: 11995–11999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wallace HA, Marques‐Kranc F, Richardson M, et al. Manipulating the mouse genome to engineer precise functional syntenic replacements with human sequence. Cell 2007; 128: 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yang L, Rau R, Goodell MA. DNMT3A in haematological malignancies. Nature Rev Cancer 2015; 15: 152–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pellagatti A, Boultwood J. The molecular pathogenesis of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Eur J Haematol 2015; 95: 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2424–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Beurlet S, Chomienne C, Padua RA. Engineering mouse models with myelodysplastic syndrome human candidate genes; how relevant are they? Haematologica 2012; 98: 10–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Holz‐Schietinger C, Matje DM, Reich NO. Mutations in DNA methyltransferase (DNMT3A) observed in acute myeloid leukemia patients disrupt processive methylation. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 30941–30951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kim SJ, Zhao H, Hardikar S, et al. A DNMT3A mutation common in AML exhibits dominant‐negative effects in murine ES cells. Blood 2013; 122: 4086–4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wu H, Zhang Y. Mechanisms and functions of Tet protein‐mediated 5‐methylcytosine oxidation. Genes Dev 2011; 25: 2436–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schubeler D. Function and information content of DNA methylation. Nature 2015; 517: 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Margueron R, Justin N, Ohno K, et al. Role of the polycomb protein EED in the propagation of repressive histone marks. Nature 2009; 461: 762–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Agger K, Christensen J, Cloos PA, et al. The emerging functions of histone demethylases. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2008; 18: 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Walport LJ, Hopkinson RJ, Vollmar M, et al. Human UTY(KDM6C) is a male‐specific N‐methyl lysyl demethylase. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 18302–18313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Herz HM, Garruss A, Shilatifard A. SET for life: biochemical activities and biological functions of SET domain‐containing proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 2013; 38: 621–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kassis JA, Brown JL. Polycomb group response elements in Drosophila and vertebrates. Adv Genet 2013; 81: 83–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mendenhall EM, Koche RP, Truong T, et al. GC‐rich sequence elements recruit PRC2 in mammalian ES cells. PLoS Genet 2010; 6: e1001244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lynch MD, Smith AJ, De Gobbi M, et al. An interspecies analysis reveals a key role for unmethylated CpG dinucleotides in vertebrate Polycomb complex recruitment. EMBO J 2012; 31 : 317–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yap DB, Chu J, Berg T, et al. Somatic mutations at EZH2 Y641 act dominantly through a mechanism of selectively altered PRC2 catalytic activity, to increase H3K27 trimethylation. Blood 2011; 117: 2451–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nikoloski G, Langemeijer SM, Kuiper RP, et al. Somatic mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nature Genet 2010; 42: 665–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Morin RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas of germinal‐center origin. Nature Genet 2010; 42: 181–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhang J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, et al. The genetic basis of early T‐cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 2012; 481: 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Simon C, Chagraoui J, Krosl J, et al. A key role for EZH2 and associated genes in mouse and human adult T‐cell acute leukemia. Genes Dev 2012; 26: 651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hock H. A complex Polycomb issue: the two faces of EZH2 in cancer. Genes Dev 2012; 26: 751–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lund K, Adams PD, Copland M. EZH2 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Leukemia 2014; 28: 44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Varambally S, Cao Q, Mani RS, et al. Genomic loss of microRNA‐101 leads to overexpression of histone methyltransferase EZH2 in cancer. Science 2008; 322: 1695–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Friedman JM, Liang G, Liu CC, et al. The putative tumor suppressor microRNA‐101 modulates the cancer epigenome by repressing the Polycomb group protein EZH2. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 2623–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Alajez NM, Shi W, Hui AB, et al. Enhancer of Zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) is overexpressed in recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma and is regulated by miR‐26a, miR‐101, and miR‐98. Cell Death Dis 2010; 1: e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Cao P, Deng Z, Wan M, et al. MicroRNA‐101 negatively regulates Ezh2 and its expression is modulated by androgen receptor and HIF‐1α/HIF‐1β. Mol Cancer 2010; 9: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science 2004; 306: 269–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, et al. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science 2011; 333: 1154–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science 2011; 333: 1157–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Gualberto A, Aldape K, Kozakiewicz K , et al. An oncogenic form of p53 confers a dominant, gain‐of‐function phenotype that disrupts spindle checkpoint control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95: 5166–5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Brosh R, Rotter V. When mutants gain new powers: news from the mutant p53 field. Nature Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 701–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Nambiar M, Raghavan SC. How does DNA break during chromosomal translocations? Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39: 5813–5825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem‐cell development. Nature Rev Cancer 2007; 7: 823–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Daser A, Rabbitts TH. Extending the repertoire of the mixed‐lineage leukemia gene MLL in leukemogenesis. Genes Dev 2004; 18: 965–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Okada Y, Feng Q, Lin Y, et al. hDOT1L links histone methylation to leukemogenesis. Cell 2005; 121: 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Mueller D, Bach C, Zeisig D, et al. A role for the MLL fusion partner ENL in transcriptional elongation and chromatin modification. Blood 2007; 110: 4445–4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Krivtsov AV, Feng Z, Lemieux ME, et al. H3K79 methylation profiles define murine and human MLL‐AF4 leukemias. Cancer Cell 2008; 14: 355–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Bernt KM, Zhu N, Sinha AU, et al. MLL‐rearranged leukemia is dependent on aberrant H3K79 methylation by DOT1L. Cancer Cell 2011; 20: 66–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Klose RJ, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. JmjC‐domain‐containing proteins and histone demethylation. Nature Rev Genet 2006; 7: 715–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument‐Bromage H, et al. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain‐containing proteins. Nature 2006; 439: 811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ntziachristos P, Tsirigos A, Welstead GG, et al. Contrasting roles of histone 3 lysine 27 demethylases in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 2014; 514: 513–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Miller SA, Mohn SE, Weinmann AS. Jmjd3 and UTX play a demethylase‐independent role in chromatin remodeling to regulate T‐box family member‐dependent gene expression. Mol Cell 2010; 40: 594–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Chen S, Ma J, Wu F, et al. The histone H3 Lys 27 demethylase JMJD3 regulates gene expression by impacting transcriptional elongation. Genes Dev 2012; 26: 1364–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Jankowska AM, Makishima H, Tiu RV, et al. Mutational spectrum analysis of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia includes genes associated with epigenetic regulation: UTX, EZH2, and DNMT3A . Blood 2011; 118: 3932–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Kruidenier L, Chung CW, Cheng Z, et al. A selective jumonji H3K27 demethylase inhibitor modulates the proinflammatory macrophage response. Nature 2012; 488: 404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Hamamoto R, Saloura V, Nakamura Y. Critical roles of non‐histone protein lysine methylation in human tumorigenesis. Nature Rev Cancer 2015; 15: 110–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Talbert PB, Henikoff S. Histone variants – ancient wrap artists of the epigenome. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11: 264–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Jang CW, Shibata Y, Starmer J, et al. Histone H3.3 maintains genome integrity during mammalian development. Genes Dev 2015; 29: 1377–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, et al. Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non‐brainstem glioblastomas. Nature Genet 2012; 44: 251–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, et al. Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature 2012; 482: 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Chan KM, Fang D, Gan H, et al. The histone H3.3K27M mutation in pediatric glioma reprograms H3K27 methylation and gene expression. Genes Dev 2013; 27: 985–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Bender S, Tang Y, Lindroth AM, et al. Reduced H3K27me3 and DNA hypomethylation are major drivers of gene expression in K27M mutant pediatric high‐grade gliomas. Cancer Cell 2013; 24: 660–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Lewis PW, Muller MM, Koletsky MS, et al. Inhibition of PRC2 activity by a gain‐of‐function H3 mutation found in pediatric glioblastoma. Science 2013; 340: 857–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Venneti S, Garimella MT, Sullivan LM, et al. Evaluation of histone 3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and enhancer of Zest 2 (EZH2) in pediatric glial and glioneuronal tumors shows decreased H3K27me3 in H3F3A K27M mutant glioblastomas. Brain Pathol 2013; 23: 558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013; 339: 1546–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom‐Lindberg E, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher‐risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open‐label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10: 223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Van der Meulen J, Sanghvi V, Mavrakis K, et al. The H3K27me3 demethylase UTX is a gender‐specific tumor suppressor in T‐cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2015; 125: 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Tan J, Yang X, Zhuang L, et al. Pharmacologic disruption of Polycomb‐repressive complex 2‐mediated gene repression selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Genes Dev 2007; 21: 1050–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Qi W, Chan H, Teng L, et al. Selective inhibition of Ezh2 by a small molecule inhibitor blocks tumor cells proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109: 21360–21365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. McCabe MT, Ott HM, Ganji G, et al. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2‐activating mutations. Nature 2012; 492: 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Kim W, Bird GH, Neff T, et al. Targeted disruption of the EZH2–EED complex inhibits EZH2‐dependent cancer. Nature Chem Biol 2013; 9: 643–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Verma SK, Tian X, LaFrance LV, et al. Identification of potent, selective, cell‐active inhibitors of the histone lysine methyltransferase EZH2. ACS Med Chem Lett 2012; 3: 1091–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Knutson SK, Wigle TJ, Warholic NM, et al. A selective inhibitor of EZH2 blocks H3K27 methylation and kills mutant lymphoma cells. Nature Chem Biol 2012; 8: 890–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Bradley WD, Arora S, Busby J, et al. EZH2 inhibitor efficacy in non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma does not require suppression of H3K27 monomethylation. Chem Biol 2014; 21: 1463–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Konze KD, Ma A, Li F, et al. An orally bioavailable chemical probe of the lysine methyltransferases EZH2 and EZH1. ACS Chem Biol 2013; 8: 1324–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Xu B, On DM, Ma A, et al. Selective inhibition of EZH2 and EZH1 enzymatic activity by a small molecule suppresses MLL‐rearranged leukemia. Blood 2015; 125: 346–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Garapaty‐Rao S, Nasveschuk C, Gagnon A, et al. Identification of EZH2 and EZH1 small molecule inhibitors with selective impact on diffuse large B cell lymphoma cell growth. Chem Biol 2013; 20: 1329–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Greenblatt SM, Nimer SD. Chromatin modifiers and the promise of epigenetic therapy in acute leukemia. Leukemia 2014; 28: 1396–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Easwaran H, Tsai HC, Baylin SB. Cancer epigenetics: tumor heterogeneity, plasticity of stem‐like states, and drug resistance. Mol Cell 2014; 54: 716–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Lyko F, Foret S, Kucharski R , et al. The honey bee epigenomes: differential methylation of brain DNA in queens and workers. PLoS Biol 2010; 8: e1000506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Lev Maor G, Yearim A, Ast G. The alternative role of DNA methylation in splicing regulation. Trends Genet 2015; 31: 274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Kang HL, Benzer S, Min KT. Life extension in Drosophila by feeding a drug. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002; 99: 838–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Chittka A, Chittka L. Epigenetics of royalty. PLoS Biol 2010; 8: e1000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Spannhoff A, Kim YK, Raynal NJ, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor activity in royal jelly might facilitate caste switching in bees. EMBO Rep 2011; 12: 238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Li X, Huang C, Xue Y. Contribution of lipids in honeybee (Apis mellifera) royal jelly to health. J Med Food 2013; 16: 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Castillo‐Fernandez JE, Spector TD, Bell JT. Epigenetics of discordant monozygotic twins: implications for disease. Genome Med 2014; 6: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, et al. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102: 10604–10609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer – analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Roberts NJ, Vogelstein JT, Parmigiani G, et al. The predictive capacity of personal genome sequencing. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4:133ra158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Rodriguez‐Cortez VC, Del Pino‐Molina L, Rodriguez‐Ubreva J, et al. Monozygotic twins discordant for common variable immunodeficiency reveal impaired DNA demethylation during naive‐to‐memory B‐cell transition. Nature Commun 2015; 6: 7335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Schmitz RJ, Schultz MD, Lewsey MG, et al. Transgenerational epigenetic instability is a source of novel methylation variants. Science 2011; 334: 369–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Greer EL, Maures TJ, Ucar D, et al. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans . Nature 2011; 479: 365–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Ng SF, Lin RC, Laybutt DR, et al. Chronic high‐fat diet in fathers programs beta‐cell dysfunction in female rat offspring. Nature 2010; 467: 963–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Dias BG, Ressler KJ. Parental olfactory experience influences behavior and neural structure in subsequent generations. Nature Neurosci 2014; 17: 89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Heard E, Martienssen RA. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: myths and mechanisms. Cell 2014; 157: 95–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Rando OJ, Simmons RA. I'm eating for two: parental dietary effects on offspring metabolism. Cell 2015; 161: 93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Holland ML, Rakyan VK. Transgenerational inheritance of non‐genetically determined phenotypes. Biochem Soc Trans 2013; 41: 769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012; 489: 57–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Andersson R, Gebhard C, Miguel‐Escalada I, et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature 2014; 507: 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Smemo S, Tena JJ, Kim KH, et al. Obesity‐associated variants within FTO form long‐range functional connections with IRX3. Nature 2014; 507: 371–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Sur IK, Hallikas O, Vaharautio A, et al. Mice lacking a Myc enhancer that includes human SNP rs6983267 are resistant to intestinal tumors. Science 2012; 338: 1360–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Kim H, Kim JS. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nature Rev Genet 2014; 15: 321–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Mendenhall EM, Williamson KE, Reyon D, et al. Locus‐specific editing of histone modifications at endogenous enhancers. Nature Biotechnol 2013; 31: 1133–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Hilton IB, D'Ippolito AM, Vockley CM, et al. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR‐Cas9‐based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nature Biotechnol 2015; 33: 510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Tebas P, Stein D, Tang WW, et al. Gene editing of CCR5 in autologous CD4 T cells of persons infected with HIV. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 901–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Genovese P, Schiroli G, Escobar G, et al. Targeted genome editing in human repopulating haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2014; 510: 235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Cox DB, Platt RJ, Zhang F. Therapeutic genome editing: prospects and challenges. Nature Med 2015; 21: 121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Lanphier E, Urnov F, Haecker SE, et al. Don't edit the human germ line. Nature 2015; 519: 410–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Higgs DR, Goodbourn SE, Lamb J, et al. Alpha‐thalassaemia caused by a polyadenylation signal mutation. Nature 1983; 306: 398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Bhatia S, Bengani H, Fish M, et al. Disruption of autoregulatory feedback by a mutation in a remote, ultraconserved PAX6 enhancer causes aniridia. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 93: 1126–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Aran D, Sabato S, Hellman A. DNA methylation of distal regulatory sites characterizes dysregulation of cancer genes. Genome Biol 2013; 14: R21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Higgs DR. The molecular basis of alpha‐thalassemia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013; 3: a011718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Kioussis D, Vanin E, deLange T, et al. Beta‐globin gene inactivation by DNA translocation in gamma beta‐thalassaemia. Nature 1983; 306: 662–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Tufarelli C, Stanley JA, Garrick D, et al. Transcription of antisense RNA leading to gene silencing and methylation as a novel cause of human genetic disease. Nature Genet 2003; 34: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Fearnhead NS, Britton MP, Bodmer WF. The ABC of APC. Hum Mol Genet 2001; 10: 721–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Balasubramani A, Larjo A, Bassein JA, et al. Cancer‐associated ASXL1 mutations may act as gain‐of‐function mutations of the ASXL1–BAP1 complex. Nature Commun 2015; 6: 7307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Noubissi FK, Elcheva I, Bhatia N, et al. CRD‐BP mediates stabilization of βTrCP1 and c‐myc mRNA in response to β‐catenin signalling. Nature 2006; 441: 898–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Gustafson WC, Weiss WA. Myc proteins as therapeutic targets. Oncogene 2010; 29: 1249–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Bosher JM, Totty NF, Hsuan JJ, et al. A family of AP‐2 proteins regulates c‐erbB‐2 expression in mammary carcinoma. Oncogene 1996; 13: 1701–1707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Nagarajan RP, Zhang B, Bell RJ, et al. Recurrent epimutations activate gene body promoters in primary glioblastoma. Genome Res 2014; 24: 761–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174. King CR, Kraus MH, Aaronson SA. Amplification of a novel v‐erbB‐related gene in a human mammary carcinoma. Science 1985; 229: 974–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Giorgio E, Robyr D, Spielmann M, et al. A large genomic deletion leads to enhancer adoption by the lamin B1 gene: a second path to autosomal dominant adult‐onset demyelinating leukodystrophy (ADLD). Hum Mol Genet 2015; 24: 3143–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Adams JM, Harris AW, Pinkert CA, et al. The c‐myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature 1985; 318: 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177. Huether R, Dong L, Chen X, et al. The landscape of somatic mutations in epigenetic regulators across 1000 paediatric cancer genomes. Nature Commun 2014; 5: 3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. Mar BG, Bullinger L, Basu E, et al. Sequencing histone‐modifying enzymes identifies UTX mutations in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2012; 26: 1881–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179. Kar SA, Jankowska A, Makishima H, et al. Spliceosomal gene mutations are frequent events in the diverse mutational spectrum of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia but largely absent in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Haematologica 2012; 98: 107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180. Gelsi‐Boyer V, Trouplin V, Adelaide J, et al. Mutations of polycomb‐associated gene ASXL1 in myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 2009; 145: 788–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]