Abstract

After severe neurocognitive decline developed in an otherwise healthy 63-year-old man, brain magnetic resonance imaging showed eosinophilic meningoencephalitis and enhancing lesions. The patient tested positive for antibodies to Baylisascaris spp. roundworms, was treated with albendazole and dexamethasone, and showed improvement after 3 months. Baylisascariasis should be considered for all patients with eosinophilic meningitis.

Keywords: Baylisascaris procyonis, baylisascariasis, eosinophilic meningitis, raccoon, roundworm, nematode, parasite, intestinal parasite, encephalitis, meningitis, meningoencephalitis, eosinophilia, zoonoses, helminths, United States, California

Over the past 30 years, the raccoon-associated roundworm Baylisascaris procyonis has emerged as an uncommon but noteworthy human pathogen associated with devastating eosinophilic meningoencephalitis in 25 patients (1–4). We report a case of neural larva migrans in an otherwise generally healthy man in California, USA.

Case Report

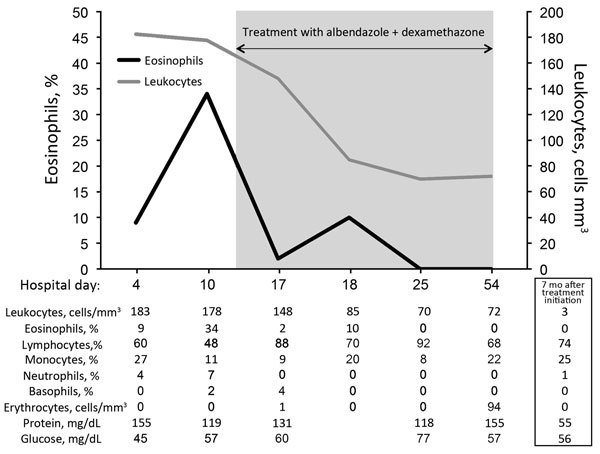

On May 18, 2015, a 63-year-old man was hospitalized in Humboldt County, California, after 2 weeks of fatigue, memory impairment, and progressive confusion accompanied by right-sided occipital headache and right-sided allodynia involving his arm and head. He was confused and disoriented to date but could recognize family; engage in brief, logical conversations; and walk independently. His medical history included essential thrombocytosis, hypothyroidism, and a remote episode of shingles. Vital signs were normal; physical examination showed no focal abnormalities. His complete blood count showed a leukocyte count of 11.5 × 109 cells/L (reference range 3.4–10 × 109 cells/L), eosinophil count of 0.75 × 109 cells/L (reference range <0.4 × 109 cells/L), and neutrophil count of 6.1 × 109/L (reference range 1.8–6.8 × 109 cells/L). Chemistry and liver panel results were normal. A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated no intracranial pathology. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed a leukocyte count of 183 × 109 cells/L (60% lymphocytes, 27% monocytes, 9% eosinophils, 4% neutrophils); protein level of 155 mg/dL; and glucose level of 45 mg/dL (Figure 1). He was started on empiric vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and acyclovir.

Figure 1.

Cell counts and laboratory values in cerebrospinal fluid from a previously healthy adult with Baylisascaris meningoencephalitis, California, USA. Hospital day 4 was June 1, 2015; hospital day 54 was July 25, 2015. Samples for 7-month values were obtained on January 1, 2016.

Over the next 3 days, the patient sustained precipitous cognitive and functional declines; incontinence, right-sided facial droop, dysarthria, diffuse hyperreflexia, and ataxia developed. Initial infectious disease diagnostics returned negative results (Table 1), so antimicrobial drugs were discontinued. CSF analysis on day 11 showed persistent pleocytosis and marked elevation of eosinophils to 34% (Figure 1). CSF cytologic and flow cytometric testing showed no malignant cells but did show reactive lymphocytes and many eosinophils, consistent with chronic inflammation.

Table 1. Microbiologic diagnostics obtained during testing of a previously healthy patient with Baylisascaris meningoencephalitis, California, USA*.

| Diagnostic study | Site | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial cultures ×4 | Blood and CSF | Negative |

| Coxiella antibody | Blood | Negative |

| Bartonella henselae and B. quintana antibodies | Blood | Negative |

| Mycoplasma antibody | Blood | IgM negative, IgG 1:5 |

| Rickettsial antibody panel | Blood | Negative |

| Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test | CSF | Negative |

| Lyme disease antibody | CSF | Negative |

| Cytomegalovirus PCR | CSF | Negative |

| Epstein–Barr virus PCR | CSF | Negative |

| Enterovirus PCR | CSF | Negative |

| Herpes simplex virus PCR | CSF | Negative |

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus IgM, IgG | CSF | IgM 1:2, IgG negative† |

| Varicella zoster virus PCR, IgM, IgG | CSF | Negative |

| West Nile virus IgM, IgG | CSF | Negative |

| Baylisascaris antibody | Blood and CSF | Positive |

| Strongyloides antibody | Blood | Negative |

| Trichinella antibody | Blood | Negative |

| Toxocara antibody | Blood | Negative |

| Toxoplasma antibody | Blood | Negative |

| Ova and parasite stain | CSF | Negative |

| Fungal stains and cultures ×4 | Blood and CSF | Negative |

| Coccidiodes antibody by complement fixation | Blood and CSF | Negative |

| Coccidiodes antibody by immunodiffusion | Blood | Negative |

| Cryptococcal antigen |

Blood and CSF |

Negative |

| AFB stains and cultures ×4 | CSF | Negative |

| Broad-range PCR (bacteria, fungi, AFB) |

CSF |

Negative |

| Cytology | CSF | Chronic inflammation |

*AFB, acid-fast bacilli; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid. †A low-titer IgM for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus was considered to be a false-positive result.

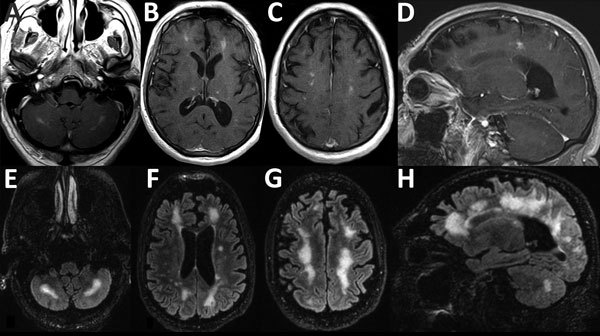

A brain MRI on day 13 showed new nodular enhancement at the gray–white junction (Figure 2, panels A–D) and patchy T2 signal abnormalities in the cerebellar, pontine, and supratentorial white matter. Due to progressive severe functional and cognitive decline, an unclear diagnosis, and concerning MRI abnormalities, the patient was transferred on day 15 to the University of California San Francisco Medical Center for evaluation. Upon transfer, he was lethargic and had moderate global aphasia and echolalia, a left forehead–sparing facial droop, spasticity in the arms, diffuse hyperreflexia, and mute plantar responses.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging scans showing brain abnormalities in a previously healthy adult with Baylisascaris meningoencephalitis, California, USA. A–D) Postgadolinium contrast T1 images obtained 4 weeks after symptom onset. A–C) Axial images, moving inferiorly to superiorly, demonstrating nodular bilateral enhancement within the cerebellar hemispheres, thalami, and subcortical white matter. D) Sagittal image further demonstrates multifocal areas of enhancement in cerebral hemispheres. Additional, mild T2 abnormalities (not shown) were present at the same time. E–H) T2/FLAIR (fluid attenuation inversion recovery) images obtained 6 weeks after symptom onset. E–G) Axial images, moving inferiorly to superiorly, demonstrating patchy and confluent hyperintense lesions throughout the supratentorial white matter and cerebellum. H) Sagittal image further demonstrates the high degree of white matter abnormality, which was not present on the earlier imaging. Postcontrast enhancement on T1 imaging (not shown) had nearly resolved at this time.

Additional history from his family revealed that the patient had worked as a contractor for >40 years in northern California. Several weeks before symptom onset, he had completed a project under his house, where raccoons and a skunk had been observed, and he had spent significant time working in a rural area with suspected raccoon activity. His occupation necessitated routine contact with soil, dust, and yard debris, and his wife said he regularly ate lunch at job sites without washing his hands. The patient was an avid hunter and had consumed bear meat 3 months before symptom onset.

Based on the patient’s exposure history, we considered infection with Baylisascaris, Toxocara, Trichinella, Coccidioides, or other microbial pathogens (Table 1). Because of the patient’s rapid neurologic decline, we initiated albendazole (20 mg/kg/d, given in doses every 12 h) and dexamethasone (4 mg every 6 h) on day 17 for empiric treatment of baylisascariasis or other helminth infection; we also initiated empiric fluconazole and doxycycline. His neurologic symptoms stabilized 1 week later.

On day 17, serum and CSF samples were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA, USA) for Baylisascaris procyonis immunoassay testing. This test uses a recombinant BpRAG1 antigen and has a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 98% (5). Thirteen days later, the results showed B. procyonis antibodies in the serum and CSF samples; results for all other studies were negative (Table 1). Repeat brain MRI on day 29 showed progression of white matter hyperintensity, near complete resolution of enhancement, and mild atrophy (Figure 2, panels E–H). The patient began to show slow, but tangible, improvement in neurologic function after 4 weeks on albendazole and dexamethasone. This combination was continued for 6 weeks, after which albendazole was stopped and a 12-week dexamethasone taper was initiated. By 3 months, the patient had recovered orientation to person and place and limited motor coordination. After 7 months, he could walk with assistance, engage in simple conversations, and perform basic activities of daily living. At that time, CSF showed normalized cell counts (Figure 1).

Most B. procyonis roundworm infections occur in young children because their frequency of oral exploration predisposes children to ingestion of infective eggs (1–6). However, B. procyonis infections have been reported in 3 adults and 2 teenagers (7–11). Of note, those 5 patients had preexisting neuropsychiatric conditions that predisposed them to ingestion of infective eggs via geophagic pica (Table 2) (7–11). In the case we report, the patient had no predisposing condition, but he probably had occupational exposure, potentiated by insufficient hand hygiene, to raccoon feces.

Table 2. Cases of cerebrospinal fluid infection with Baylisascaris spp. roundworms in adults and adolescents, United States and Canada, 1986–2015.

| Year | Patient age, y | Location | Risk factor(s) | Treatment | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | 21 | Oregon, USA | Developmental delay and geophagia | Not recorded | Persistent residual deficits | (7) |

| 2000 | 17 | California, USA | Developmental delay and geophagia | Albendazole and antiinflammatory drugs | Died | (8) |

| 2007 | 17 | Oregon, USA | Altered mentation from drug abuse | None | Aphasia and memory deficits | (9) |

| 2009 | 54 | Missouri, USA | Intellectual disability; eating food scraps from public garbage cans | None | Died | (10) |

| 2012 | 73 | British Columbia, Canada | Dementia | None | Identified at time of autopsy | (11) |

| 2015 | 63 | California, USA | Home or occupational exposure | Albendazole (20 mg/kg/d) + dexamethasone (1 mg/kg/d) | Partial recovery after 6 weeks | This report |

Most symptomatic cases of neural larva migrans caused by infection with Baylisascaris roundworms have resulted in irreversible neurologic damage, and 5 deaths have been reported (1–3). Partial to complete recovery occurred in 4 cases, presumably due to a low level of infection at the time of diagnosis, early aggressive treatment, or both (9,12–14).

Because the differential diagnosis for eosinophilic meningitis is relatively restricted, we principally considered infectious etiologies consistent with the patient’s demographics and exposure history. His risk factors associated with an infectious etiology included living and working near a region where Coccidiodes immitis is endemic and exposure to raccoon-associated Baylisascaris roundworms. For this patient, MRI findings similar to those for other B. procyonis–infected patients included subcortical nodular enhancement and linear hyperintensities in the cerebellar white matter on T1- and T2-weighted images (Figure 2) (14).

The optimal treatment for baylisascariasis in adults is not known; the current recommendation for albendazole (25–50 mg/kg/d) comes from successful empiric regimens used in children (http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/baylisascaris/health_professionals/index.html#tx). Albendazole is the cornerstone of therapy for B. procyonis neural larva migrans and is combined with a corticosteroid to enhance central nervous system (CNS) penetration and mitigate inflammation-associated tissue necrosis (3,4,15). Due to low CNS penetration, ivermectin is ineffective for treating B. procyonis neural larva migrans (1,3). Despite treatment, outcomes are often poor because extensive CNS inflammatory damage and tissue necrosis usually occurs before diagnosis (3,4,6); thus, early recognition of baylisascariasis and prompt initiation of treatment are essential. Because of concern for adverse side effects, including agranulocytosis and hepatotoxicity, we used a 6-week regimen of albendazole plus dexamethasone. We observed reversal of disease progression and a modest neurocognitive recovery after 3 months.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates that severe neurologic disease from infection with B. procyonis roundworms can develop in otherwise healthy adults with incidental exposures. The patient in this report had no history of overt immune compromise and few concurrent conditions and was generally well until the inadvertent ingestion of occult B. procyonis eggs. This case highlights the importance of considering baylisascariasis in all patients with eosinophilic meningitis, and it underscores the importance of obtaining a detailed exposure history, understanding the causes of eosinophilic meningitis, and initiating early aggressive therapy when infection is suspected.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient’s wife and son, who were instrumental in diagnosis and care of the patient.

Biography

Dr. Langelier is a clinical fellow in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of California, San Francisco. His research interests involve using metagenomics and transcriptional profiling to investigate host–pathogen interactions and understand the causes of diagnostically challenging diseases.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Langelier C, Reid MJ, Halabi C, Wietek N, LaRiviere A, Shah M, et al.. Baylisascaris procyonis–associated meningoencephalitis in a previously healthy adult, California, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Aug [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2208.151939

References

- 1.Kazacos KR. Baylisascaris and related species. In: Samuel WM, Pybus MJ, Kocan AA, editors. Parasitic diseases of wild mammals, 2nd ed. Ames (IA): State University Press; 2001. p. 301–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray WJ, Kazacos KR. Raccoon roundworm encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1484–92. 10.1086/425364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavin PJ, Kazacos KR, Shulman ST. Baylisascariasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:703–18. 10.1128/CMR.18.4.703-718.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazacos KR, Jelicks LA, Tanowitz HB. Baylisascaris larva migrans. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;114:251–62. 10.1016/B978-0-444-53490-3.00020-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rascoe LN, Santamaria C, Handali S, Dangoudoubiyam S, Kazacos KR, Wilkins PP, et al. Interlaboratory optimization and evaluation of a serological assay for diagnosis of human baylisascariasis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:1758–63. 10.1128/CVI.00387-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazacos KR. Protecting children from helminthic zoonoses. Contemp Pediatr. 2000;17(Suppl):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham CK, Kazacos KR, McMillan JA, Lucas JA, McAuley JB, Wozniak EJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of Baylisascaris procyonis infection in an infant with nonfatal meningoencephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:868–72. 10.1093/clinids/18.6.868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazacos KR, Gavin PJ, Shulman ST, Tan TQ, Gerber SI, Kennedy WA, et al. Raccoon roundworm encephalitis—Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;50:1153–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun CS, Kazacos KR, Glaser C, Bardo D, Dangoudoubiyam S, Nash R. Global neurologic deficits with baylisascaris encephalitis in a previously healthy teenager. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:925–7. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181a648f1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciarlini P, Gutierrez Y, Gambetti P, Cohen M. Necrotizing eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. Presented at the 87th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Neuropathologists; 2011. Jun 23–26; Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung T, Neafie RC, Mackenzie IRA. Baylisascaris procyonis infection in elderly person, British Columbia, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:341–2. 10.3201/eid1802.111046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pai PJ, Blackburn BG, Kazacos KR, Warrier RP, Bégué RE. Full recovery from Baylisascaris procyonis eosinophilic meningitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:928–30. 10.3201/eid1306.061541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajek J, Yau Y, Kertes P, Soman T, Laughlin S, Kanani R, et al. A child with raccoon roundworm meningoencephalitis: a pathogen emerging in your own backyard? Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2009;20:e177–80. 10.1155/2009/304625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters JM, Madhavan VL, Kazacos KR, Husson RN, Dangoudoubiyam S, Soul JS. Good outcome with early empiric treatment of neural larva migrans due to Baylisascaris procyonis. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e806–11. 10.1542/peds.2011-2078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites—Baylisascaris infection. Resources for health professionals [cited 2016 Feb 1]. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/baylisascaris/health_professionals/index.html#tx