Abstract

Background:

Serum 25(OH) vitamin D levels are inversely associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, mediated in part by independent positive relationships with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC) and inverse relationships with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC), triglyceride, and homocysteine.

Aims:

In this study, we assessed relationships between fasting serum vitamin D and lipids, lipoprotein cholesterols, and homocysteine.

Materials and Methods:

We studied 1534 patients sequentially referred to our center from 2007 to 2016. Fasting serum total 25(OH) vitamin D, plasma cholesterol, triglyceride, HDLC, LDLC, and homocysteine were measured. Stepwise regression models were used with total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDLC, LDLC, and homocysteine as dependent variables and explanatory variables age, race, gender, body mass index (BMI), and serum vitamin D levels. Relationships between quintiles of serum vitamin D and triglycerides, HDLC, LDLC, and homocysteine were assessed after covariance adjusting for age, race, gender, and BMI.

Results:

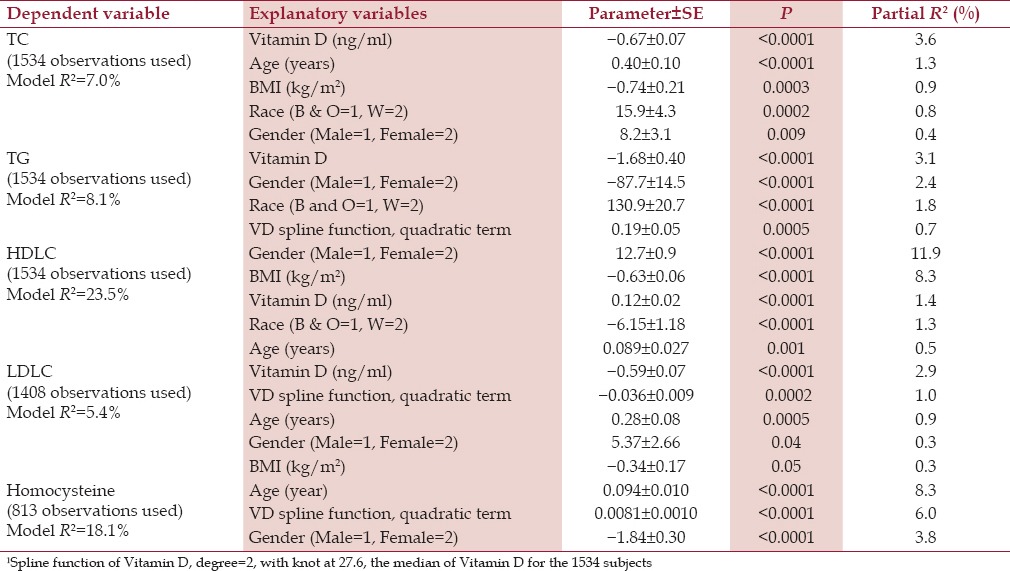

Fasting serum vitamin D was positively correlated with age, HDLC, and White race, and was inversely correlated with BMI, total and LDL cholesterol, triglyceride, and fasting serum homocysteine (P ≤ 0.0001 for all). Serum vitamin D was a significant independent inverse explanatory variable for total cholesterol, triglyceride, and LDL cholesterol, and accounted for the largest amount of variance in serum total cholesterol (partial R2 =3.6%), triglyceride (partial R2 =3.1%), and LDLC (partial R2 =2.9%) (P < 0.0001 for all). Serum vitamin D was a significant positive explanatory variable for HDLC (partial R2 = 1.4%, P < 0.0001), and a significant inverse explanatory variable for homocysteine (partial R2 = 6.0–12.6%).

Conclusions:

In hyperlipidemic patients, serum vitamin D was a significant independent inverse determinant of total cholesterol, LDLC, triglyceride, and homocysteine, and a significant independent positive determinant of HDLC. Thus, serum vitamin D might be protective against CVD.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, homocysteine, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, myocardial infarction, triglycerides, Vitamin D

Introduction

Serum vitamin D levels are associated with adiposity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome,[1,2] and it is not surprising that low levels of serum vitamin D are significant independent predictors of cardiovascular disease (CVD).[3,4] High levels of vitamin D and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC) are associated with a lower risk of CVD.[5] There are independent and significant positive correlations between serum vitamin D and apolipoprotein A1 and HDLC in adult men and women.[6] Vitamin D deficiency has been reported to be an independent predictor of elevated triglycerides in Spanish school children.[7] Vitamin D supplementation in Argentine school children increased HDLC and decreased triglyceride.[8] In women with polycystic ovary syndrome, vitamin D therapy decreased total cholesterol, triglyceride, and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC), however, did not affect HDLC or apolipoprotein A1.[9]

In some studies, vitamin D supplementation has been reported to have no significant effect on CVD mortality[10] or on the incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke.[11] Wang et al. reported a nonsignificant reduction in CVD with moderate-to-high doses of vitamin D (risk ratio: 0.90; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.77–1.05).[12] Vitamin D supplementation may protect against cardiac failure in older people, however, in a meta-analysis, it did not appear to protect against MI or stroke.[13]

In 1534 patients referred to our Cholesterol Center from 2007 to 2016, we assessed pretreatment entry relationships between fasting serum vitamin D and lipids, lipoprotein cholesterols, and homocysteine to better understand the independent relationships of serum vitamin D to CVD risk factors.

Materials and Methods

The study was carried out following protocol #12-03 approved by the Jewish Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We evaluated routine lipid, lipoprotein, homocysteine, and serum vitamin D determinations drawn at study entry after an overnight fast as part of our standard clinical initial evaluation of referred patients, following a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati. We studied 1534 patients in the consecutive order of their referral from 2007 to 2016.

Laboratory determinations

At the initial visit, after an overnight fast, blood was drawn for serum total 25(OH) vitamin D levels quantitated by two-dimensional high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with tandem mass spectrometry detection after protein precipitation.[14] The laboratory lower normal limit for total 25(OH) vitamin D was 32 ng/ml.[14] Additional measures included plasma cholesterol, triglyceride, HDLC, LDLC, and in some patients, fasting serum homocysteine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Statistical analysis

Because the data was not normally distributed, Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated between serum vitamin D and other variables. Stepwise regression models were used with total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDLC, LDLC, and homocysteine as dependent variables, and explanatory variables such as age, race, gender, body mass index (BMI), and serum vitamin D levels.

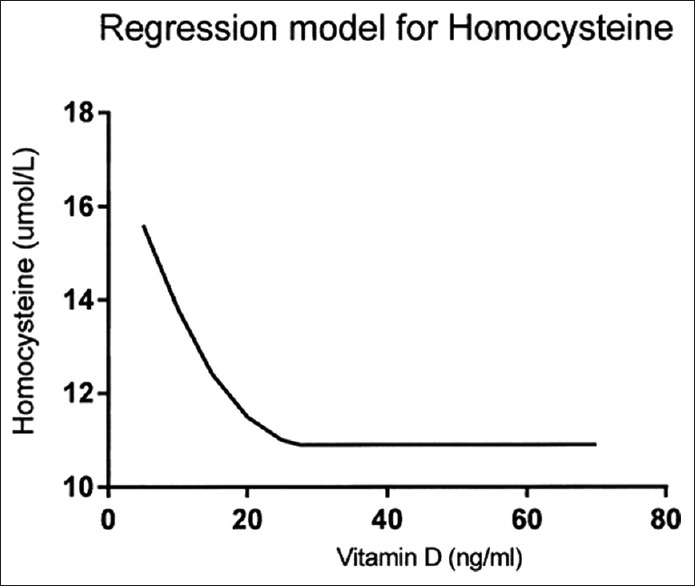

To assess whether the association between serum vitamin D and homocysteine (or lipids) might be nonlinear, a spline second-degree function of vitamin D with a single knot at the cohort median of serum vitamin D (27.6 ng/ml) [Figure 1] was included in the linear regression model[15] to test the hypothesis that the association between serum vitamin D and homocysteine (or lipids) existed up to the median of serum vitamin D, but not above it.

Figure 1.

Curvilinear relationship between serum vitamin D and homocysteine. A splined function of vitamin D was used in regression models, knot = 27.6 ng/ml (cohort median for serum vitamin D), and degree = 2

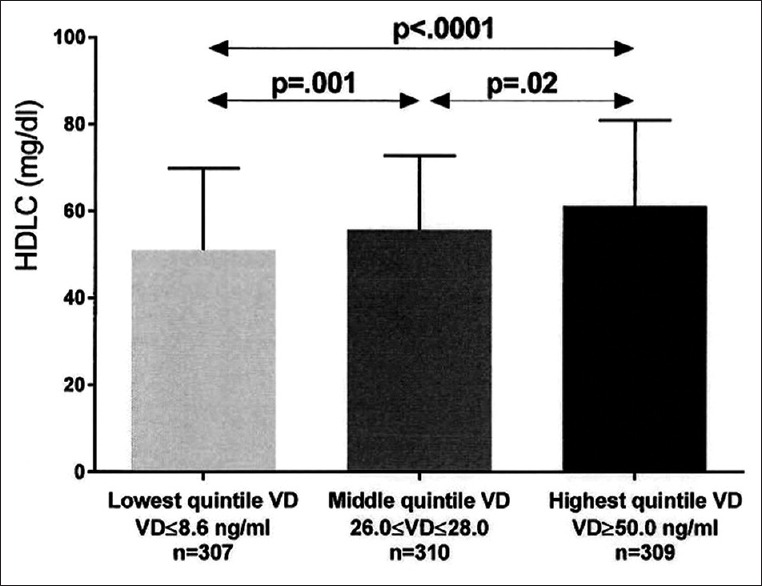

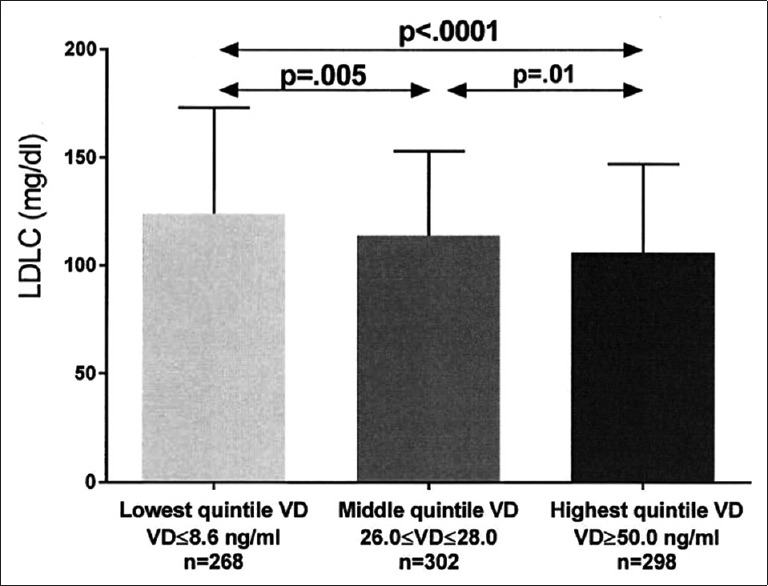

We categorized serum vitamin D in quintiles, and assessed least square mean triglyceride, HDLC, LDLC, and homocysteine by D quintiles, after covariance adjusting for age, race, gender, and BMI [Figures 2–5].

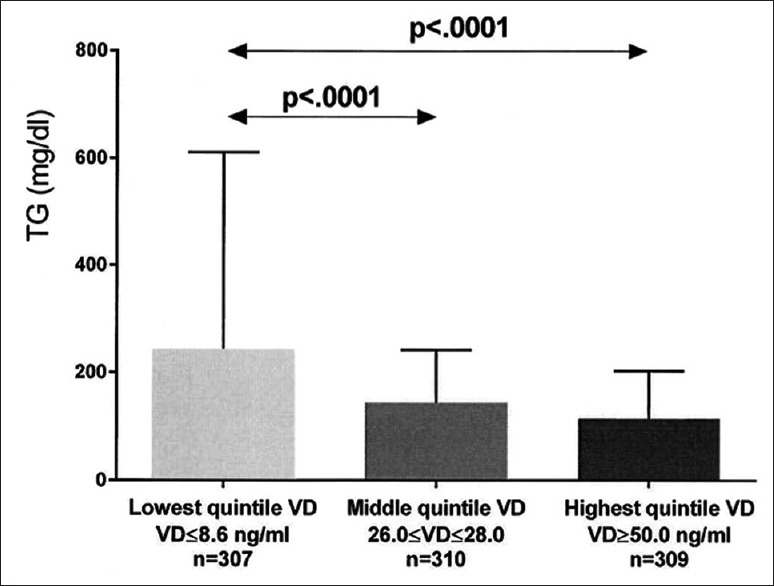

Figure 2.

Unadjusted triglyceride (mean ± SD) in the lowest, middle, and highest vitamin D (VD) quintiles exhibited. Significant differences between groups are shown, with P values taken from comparisons of least squares means after adjustment for age, race, gender, and body mass index

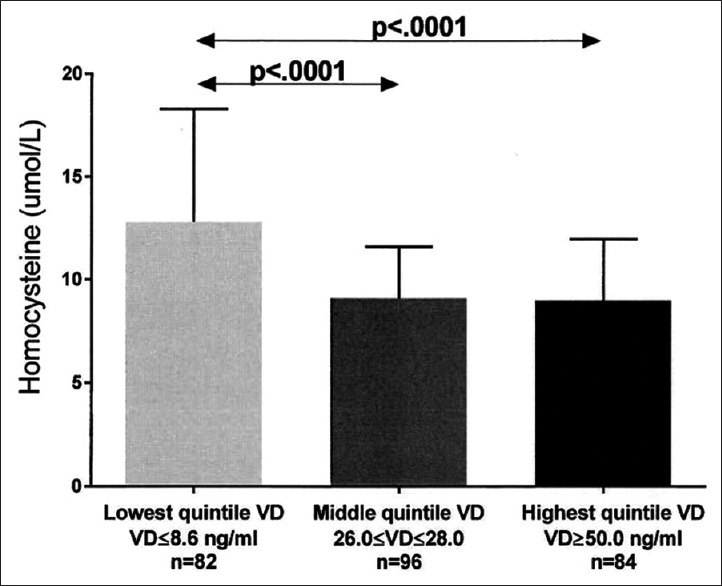

Figure 5.

Unadjusted serum homocysteine (mean ± SD) in the lowest, middle, and highest vitamin D quintiles exhibited. Significant differences between groups are shown, with P values taken from comparisons of least squares means after adjustment for age, race, gender, and body mass index

Results

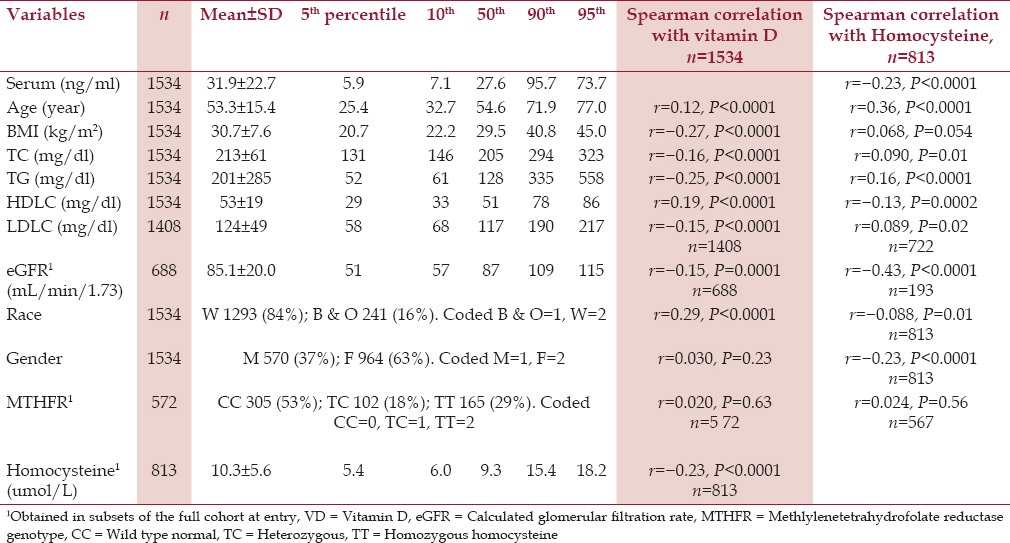

As displayed in Table 1, fasting serum vitamin D was positively correlated with age, HDLC, and White race (P < 0.0001 for all). Serum vitamin D was inversely correlated with BMI, total cholesterol and LDLC, triglyceride, eGFR, and fasting serum homocysteine (P ≤ 0.0001 for all) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Vitamin D, lipids, lipoprotein cholesterols, glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), 1MTHFR genotype, 1and homocysteine1 in 1534 patients at study entry

Homocysteine was positively correlated with age, BMI, total cholesterol, LDLC, and was inversely correlated with HDLC, eGFR, female gender, and White race [Table 1].

Vitamin D, as a significant negative independent determinant, accounted for the largest amount of variance in serum total cholesterol (partial R2 =3.6%), triglyceride (partial R2 =3.1%), and LDLC (partial R2 =2.9%) [Table 2]. Serum vitamin D was also a significant positive independent predictor for HDLC (partial R2 =1.4%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Significant predictors for lipids, lipoprotein cholesterols, and homocysteine with explanatory variables race, gender, age, body mass index, serum vitamin D level (VD), and spline function1 of VD

Vitamin D was a significant negative independent determinant of triglyceride, with a linear term and a splined quadratic term [Table 2, panel 2]. The spline quadratic term of vitamin D (with a positive coefficient) was significant for triglyceride in addition to the linear term [Table 2, panel 2]. The spline quadratic term for vitamin D accounted for an extra decrement in triglyceride up to the cohort mean of vitamin D, 26.7 ng/ml with no further decrements above the median.

Vitamin D was a significant negative independent determinant of LDLC [Table 2, panel 4] as a linear term, whereas the spline function for vitamin D provided a reduced decrement in LDLC up to the cohort vitamin D median, 26.7 ng/ml.

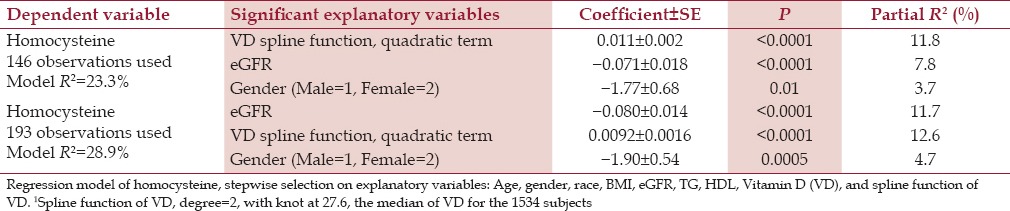

The curvilinear relationship between homocysteine and vitamin D is displayed in three regression models, which included the splined quadratic function of vitamin D [Table 2, panel 5 and Table 3, panels 1 and 2] [Figure 1]. The spline vitamin D quadratic term was a significant predictor of homocysteine; homocysteine decreased when vitamin D increased from low levels up to the cohort median (27.6 ng/ml), however, it did not decrease further as vitamin D increased above 27.6 ng/ml [Figure 1].

Table 3.

Homocysteine 193 observations: Regression model of homocysteine, stepwise selection of explanatory variables: Age, gender, race, BMI, eGFR, TG, HDL, Vitamin D (VD), and spline function of VD

As displayed in Table 3, beyond the spline function of vitamin D, other significant explanatory variables for homocysteine included eGFR (inverse) and gender (female lower). Removing the MTHFR genotype, a nonsignificant explanatory variable, allowed an increase in the size of the model [Table 3, panel 2], and the resultant model was similar. Of the 3 regression models for homocysteine [bottom panel Table 2 and 3], the spline function of vitamin D was an important explanatory variable, partial R2 = 6.0–12.6%.

After covariance adjusting for age, race, gender, and BMI, least square (LS) mean triglyceride was highest in patients with the lowest quintile serum vitamin D versus patients in both the middle and top quintiles [Figure 2]. Covariance adjusted HDLC was lowest in patients with lowest quintile serum vitamin D versus those with middle and top quintile vitamin D, and was lower in patients with middle quintile vitamin D than those with top quintile vitamin D [Figure 3]. Covariance adjusted LDLC was highest in patients with the lowest quintile serum vitamin D, lower in patients with middle quintile vitamin D, and was lowest in patients with highest quintile vitamin D [Figure 4]. Covariance adjusted fasting serum homocysteine was highest in patients with the lowest quintile serum vitamin D, and lower in patients with both middle and top quintile serum vitamin D levels [Figure 5].

Figure 3.

Unadjusted high density lipoprotein cholesterol (mean ± SD) in the lowest, middle, and highest vitamin D quintiles exhibited. Significant differences between groups are shown, with P values taken from comparisons of least squares means after adjustment for age, race, gender, and body mass index

Figure 4.

Unadjusted low density lipoprotein cholesterol (mean ± SD) in the lowest, middle, and highest vitamin D quintiles exhibited. Significant differences between groups are shown, with P values taken from comparisons of least squares means after adjustment for age, race, gender, and body mass index

Discussion

Our data is congruent with previous studies that reported that higher serum vitamin D levels are associated with lower CVD risk lipid profiles.[16,17] In our current study of patients referred for the diagnosis and treatment of hyperlipidemia and CVD, serum vitamin D was a significant independent inverse determinant of total cholesterol, LDLC, triglyceride, and homocysteine, and a significant independent positive determinant of HDLC. Within this frame of reference, if vitamin D supplementation lowered total cholesterol, LDLC, and triglyceride, as well as serum homocysteine, and elevated HDLC, it should be antiatherogenic.

Significant independent positive correlations between serum vitamin D and apolipoprotein A1 and HDLC have been reported in adult men and women.[6] In a database of 20360 participants,[18] serum vitamin D was positively associated with HDLC and inversely associated with triglyceride and LDLC. Low serum vitamin D was associated with high LDLC and triglyceride in diabetic and nondiabetic patients with stable CVD.[19] Low vitamin D levels were associated independently with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.[19] In early childhood, serum vitamin D was inversely associated with nonHDLC, total cholesterol, and triglyceride.[20] Vitamin D deficiency was an independent predictor of elevated triglycerides in Spanish school children.[7]

Several mechanisms have been identified that might partially explain the effects of vitamin D on lipids and lipoproteins. In vitro, vitamin D metabolites can upregulate lipoprotein lipase,[21] increasing HDLC and lowering triglyceride. Vitamin D has anti-inflammatory effects, and might, speculatively, reduce insulin resistance by reducing low-grade chronic inflammation,[22,23] thus lowering triglycerides and increasing HDLC.

In placebo-controlled vitamin D intervention studies in adults, effects on LDLC, HDLC, and triglyceride have been varied and inconclusive.[24,25] In the Women's Health Initiative, where 1 g calcium-400 IU vitamin D were given in a double-blind randomized trial, LDLC reduced significantly (P = 0.03), and higher serum concentrations of vitamin D were associated with higher HDLC levels (P = 0.003), along with lower LDLC (P = 0.02) and triglyceride levels (P < 0.001).[26] In a placebo-controlled trial of vitamin D in patients with type 2 diabetes,[27] vitamin D reduced serum total cholesterol, but not triglyceride or HDLC. Although most vitamin D supplementation trials have not demonstrated reduction in CVD, they have used relatively low doses of vitamin D supplementation, emphasizing the important of future trials with higher levels of vitamin D intervention, with focus on cardiovascular events.[25]

Inverse associations between serum vitamin D and homocysteine have been reported in Chinese[28] and North American (NHANES)[15] studies, but not in a Canadian[29] study. An curvilinear inverse association between serum vitamin D and homocysteine has been reported by Amer et al. in individuals with serum vitamin D below the group median (≤21 ng/ml),[15] however, in those with vitamin D levels >21 ng/ml, homocysteine did not fall as serum vitamin D increased. In our study, congruent with the report by Amer et al.,[15] vitamin D supplementation should lower homocysteine in subjects with serum vitamin D below the cohort median (27.6 ng/ml-our study), but may not be of benefit for those with serum vitamin D above 27.6 ng/ml. Overall, in the current report, with the spline term[15] in the model, vitamin D independently accounted for 6.0–12.6% of the variance of homocysteine, and, as such, vitamin D supplementation for subjects with serum vitamin D below the median should, speculatively, reduce the homocysteine-mediated risk of ischemic stroke.[30,31]

Risk factors for CVD including blood pressure,[32] smoking,[23] obesity,[33,34] physical inactivity,[35] and advanced age[36] are associated with lower serum vitamin D, making it difficult to ascribe an independent role of vitamin D in the development of CVD. However, there is an inverse association between vitamin D and all-cause mortality,[37] and Shotker et al. reported consistent inverse associations between vitamin D quintiles and both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.[38] We speculate that the relationships between serum vitamin D and both lipoprotein cholesterols and homocysteine underlie the reported[38] inverse association of vitamin D with cardiovascular mortality. Placebo-controlled clinical trials of vitamin D supplementation in hyperlipidemic and hyperhomocysteinemic cohorts will be required to cross the bridge from correlation to causation.

Conclusion

In hyperlipidemic patients, serum vitamin D is a significant independent inverse determinant of total cholesterol, LDLC, triglyceride, and homocysteine, and a significant independent positive determinant of HDLC. We speculate that through these relationships, serum vitamin D might be protective against CVD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ford ES, Ajani UA, McGuire LC, Liu S. Concentrations of serum vitamin D and the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1228–30. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiu KC, Chu A, Go VL, Saad MF. Hypovitaminosis D is associated with insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:820–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson JL, May HT, Horne BD, Bair TL, Hall NL, Carlquist JF, et al. Relation of vitamin D deficiency to cardiovascular risk factors, disease status, and incident events in a general healthcare population. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:963–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beveridge LA, Witham MD. Vitamin D and the cardiovascular system. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2167–80. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, Jacques PF, Ingelsson E, Lanier K, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117:503–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auwerx J, Bouillon R, Kesteloot H. Relation between 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, apolipoprotein A-I, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12:671–4. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Rodriguez E, Aparicio A, Lopez-Sobaler AM, Ortega RM. Vitamin D status in a group of Spanish schoolchildren. Minerva Pediatr. 2011;63:11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirschler V, Maccallini G, Tamborenea MI, Gonzalez C, Sanchez M, Molinari C, et al. Improvement in lipid profile after vitamin D supplementation in indigenous argentine school children. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2014;12:42–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahimi-Ardabili H, Pourghassem Gargari B, Farzadi L. Effects of vitamin D on cardiovascular disease risk factors in polycystic ovary syndrome women with vitamin D deficiency. J Endocrinol Invest. 2013;36:28–32. doi: 10.3275/8303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Nikolova D, Whitfield K, Krstic G, Wetterslev J, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of cancer in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD007469. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007469.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elamin MB, Abu Elnour NO, Elamin KB, Fatourechi MM, Alkatib AA, Almandoz JP, et al. Vitamin D and cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1931–42. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Manson JE, Song Y, Sesso HD. Systematic review: Vitamin D and calcium supplementation in prevention of cardiovascular events. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:315–23. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford JA, MacLennan GS, Avenell A, Bolland M, Grey A, Witham M. Cardiovascular disease and vitamin D supplementation: Trial analysis, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:746–55. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.082602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsugawa N, Suhara Y, Kamao M, Okano T. Determination of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in human plasma using high-performance liquid chromatography--Tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2005;77:3001–7. doi: 10.1021/ac048249c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amer M, Qayyum R. The relationship between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and homocysteine in asymptomatic adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:633–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martins D, Wolf M, Pan D, Zadshir A, Tareen N, Thadhani R, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and the serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the United States: Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1159–65. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng S1, Massaro JM, Fox CS, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, McCabe EL, et al. Adiposity, cardiometabolic risk, and vitamin D status: The Framingham Heart Study. Diabetes. 2010;59:242–8. doi: 10.2337/db09-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lupton JR, Faridi KF, Martin SS, Sharma S, Kulkarni K, Jones SR, et al. Deficient serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is associated with an atherogenic lipid profile: The Very Large Database of Lipids (VLDL-3) study. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:72–81 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pekkanen MP, Ukkola O, Hedberg P, Piira OP, Lepojärvi S, Lumme J, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is associated with major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiac structure and function in patients with coronary artery disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:471–8. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birken CS, Lebovic G, Anderson LN, McCrindle BW, Mamdani M, Kandasamy S, et al. Association between Vitamin D and Circulating Lipids in Early Childhood. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Querfeld U, Hoffmann MM, Klaus G, Eifinger F, Ackerschott M, Michalk D, et al. Antagonistic effects of vitamin D and parathyroid hormone on lipoprotein lipase in cultured adipocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2158–64. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10102158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewison M. An update on vitamin D and human immunity. Clin Endocrinol. 2012;76:315–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chagas CE, Borges MC, Martini LA, Rogero MM. Focus on vitamin D, inflammation and type 2 diabetes. Nutrients. 2012;4:52–67. doi: 10.3390/nu4010052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorde R, Grimnes G. Vitamin D and metabolic health with special reference to the effect of vitamin D on serum lipids. Prog Lipid Res. 2011;50:303–12. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnatz PF, Manson JE. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease: An appraisal of the evidence. Clin Chem. 2014;60:600–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.211037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnatz PF, Jiang X, Vila-Wright S, Aragaki AK, Nudy M, O’sullivan DM, et al. Calcium/vitamin D supplementation, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and cholesterol profiles in the Women's Health Initiative calcium/vitamin D randomized trial. Menopause. 2014;21:823–33. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jafari T, Fallah AA, Barani A. Effects of vitamin D on serum lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.03.001. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao X, Xing X, Xu R, Gong Q, He Y, Li S, et al. Folic Acid and Vitamins D and B12 Correlate With Homocysteine in Chinese Patients With Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension, or Cardiovascular Disease. Medicine. 2016;95:e2652. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Bailo B, Da Costa LA, Arora P, Karmali M, El-Sohemy A, Badawi A. Plasma vitamin D and biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease risk in adult Canadians, 2007-2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E91. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spence JD, Bang H, Chambless LE, Stampfer MJ. Vitamin Intervention For Stroke Prevention trial: An efficacy analysis. Stroke. 2005;36:2404–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185929.38534.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, Spence JD, Pettigrew LC, Howard VJ, et al. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death: The Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:565–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witham MD, Nadir MA, Struthers AD. Effect of vitamin D on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1948–54. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832f075b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliai Araghi S, van Dijk SC, Ham AC, Brouwer-Brolsma EM, Enneman AW, Sohl E, et al. BMI and Body Fat Mass Is Inversely Associated with Vitamin D Levels in Older Individuals. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:980–5. doi: 10.1007/s12603-015-0657-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren W, Gu Y, Zhu L, Wang L, Chang Y, Yan M, et al. The effect of cigarette smoking on vitamin D level and depression in male patients with acute ischemic stroke. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;65:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker CP, Kulkarni B, Radhakrishna KV, Charyulu MS, Gregson J, Matsuzaki M, et al. Is the Association between Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Confounded by Obesity? Evidence from the Andhra Pradesh Children and Parents Study (APCAPS) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savji N, Rockman CB, Skolnick AH, Guo Y, Adelman MA, Riles T, et al. Association between advanced age and vascular disease in different arterial territories: A population database of over 3.6 million subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1736–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chien KL, Hsu HC, Chen PC, Lin HJ, Su TC, Chen MF, et al. Total 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration as a predictor for all-cause death and cardiovascular event risk among ethnic Chinese adults: A cohort study in a Taiwan community. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schottker B, Jorde R, Peasey A, Thorand B, Jansen EH, Groot LD, et al. Vitamin D and mortality: Meta-analysis of individual participant data from a large consortium of cohort studies from Europe and the United States. BMJ. 2014;348:g3656. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]