Abstract

Objectives:

Prior U.S. population studies have found that childhood adversity influences the quality of relationships in adulthood, with emerging research suggesting that this association might be especially strong for black men. We theorize psychosocial and behavioral coping responses to early life adversity and how these responses may link early life adversity to strain in men’s relationships with their indeterminate partners and children across the life course, with attention to possible racial variation in these experiences and implications for later life well-being.

Method:

We analyze in-depth interviews with 15 black men and 15 white men. We use qualitative analysis techniques to connect childhood experiences to psychosocial processes in childhood and behavioral coping strategies associated with relationship experiences throughout adulthood.

Results:

Black men describe much stronger and more persistent childhood adversity than do white men. Findings further suggest that childhood adversity contributes to psychosocial processes (e.g., diminished sense of mastery) that may lead to ways of coping with adversity (e.g., self-medication) that are likely to contribute to relationship difficulties throughout the life span.

Discussion:

A life course perspective directs attention to the early life origins of cumulative patterns of social disadvantage, patterns that extend to later life. Our findings suggest psychosocial and behavioral pathways through which early life adversity may constrain and strain men’s relationships, possibly contributing to racial inequality in family relationships across the life span.

Keywords: Cumulative advantage/disadvantage, Family sociology, In-depth interviews, Minority aging (race/ethnicity), Qualitative methods, Stress

Access to and participation in stable and supportive family relationships has emerged as a key buffer against stress, a predictor of successful aging, and, relatedly, an important nexus of inequality in the United States (McLanahan & Percheski, 2008). This process is launched early in the life course. A recent population-based study implicates childhood adversity—high levels of stress and disadvantage in childhood—as a strong predictor of relationship strain in adulthood for men, and even more so for black men compared with white men as well as compared with black and white women (Umberson, Williams, Thomas, Liu, & Thomeer, 2014). Indeed, this recent study found that childhood adversity is not linked to adult relationship strain among women (Umberson et al., 2014). At this point, we lack information on the nature of the life course processes through which childhood adversity interferes with lasting and supportive family relationships for men throughout life. Given the importance of close relationships for successful aging, health, well-being, and even longevity (Umberson & Montez, 2010), it is important to understand how childhood experiences launch a lifelong influence on men’s family relationships. Our examination of experiences of childhood adversity and adult relationships for men is guided by a stress and life course perspective, emphasizing the processes through which structural disadvantages in childhood reinforce and exacerbate inequalities throughout the life course including at the oldest ages (Gee, Walsemann, & Brondolo, 2012).

We are particularly interested in the link between childhood adversity and relationships with intimate partners and children among men because prior studies show that these relationships are most salient to men’s health and well-being throughout the life course (Fuhrer & Stansfeld, 2002). Men’s relationships are also unique from women’s in several ways. Men tend to have smaller social networks than women (Fuhrer & Stansfeld, 2002; Taylor, 2011) and are more likely to withdraw from others in response to stress (Taylor et al., 2000), perhaps placing men at particular risk for poor relationship quality and social isolation in the wake of stressful experiences. Moreover, gendered stress and relationship experiences may unfold in different ways for black men and white men over the life course. Prior research suggests that the processes linking childhood adversity to adult family relationships may differ by race (Umberson et al., 2014). Indeed, recent research emphasizes that the experience of being a man in U.S. society is quite different for black men and white men (Williams, 2003), and these differences begin early in the life course, with implications for adult family relationships at older ages.

We use qualitative data from in-depth interviews with 15 black men and 15 white men to (i) consider psychosocial and behavioral responses to childhood adversity, (ii) understand how these responses to childhood adversity may influence men’s relationships with intimate partners and children at older ages, and (iii) consider how the experience of childhood adversity and its influence on relationships in later life may be distinctive for black men compared with white men.

A Life Course Perspective on Childhood Adversity and Family Relationships in Adulthood

A growing scientific consensus implicates childhood adversity as a fundamental determinant of lifelong well-being operating through psychosocial, socioeconomic, behavioral, and physiological pathways (see Shonkoff et al., 2012). For example, an emerging body of quantitative scholarship suggests that childhood adversity shapes important aspects of adult well-being, including the quality of close personal relationships (Kogan et al., 2013; Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002; Umberson et al., 2014) as well as a range of health conditions decades later and at very old ages (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Hatch, 2005). Indeed, the quality of close relationships in adulthood partially mediates adverse effects of childhood adversity on men’s health throughout the life course (Umberson et al., 2014). Although informative, these quantitative studies do not explore the specific psychosocial and behavioral life course processes through which childhood adversity has an enduring impact on adult relationships. This information is essential for developing effective policies and interventions to disrupt the accumulation and consequences of social disadvantage over the life course, including health disparities in late life.

The integration of a life course perspective with the stress process model (Pearlin & Skaff, 1996), particularly when coupled with qualitative analysis of in-depth interviews, can provide unique insights into how childhood conditions continue to shape social experiences throughout the life span (Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003). Exposure to stress, which is strongly shaped by social position (Turner, Wheaton, & Lloyd, 1995), may undermine the specific psychosocial resources (e.g., a sense of mastery over life circumstances) that facilitate effective coping with stress and thus precipitate a cascade of future additional stressors, a process referred to as stress proliferation (Pearlin, 2010; Pearlin, Schieman, Fazio, & Meersman, 2005). In this way, the individual process of stress proliferation translates to a structural process of cumulative disadvantage (Thoits, 2010) that exacerbates inequalities into older ages. Although stress proliferation can occur at any point in the life course, vulnerability to certain types of stressors appears to be heightened during “sensitive periods” in the life course. For example, childhood seems to be a sensitive period during which high levels of stress are particularly detrimental to health in adulthood and later life (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011; Shonkoff et al., 2012).

Although most commonly used to explain the long reach of childhood conditions on health in adulthood and later life (Warner & Hayward, 2006), the central tenets of the life course perspective are equally relevant to understanding the link between childhood adversity and adult relationship strain. Research and theory on attachment suggest that childhood is a sensitive period for the acquisition of trust and security that ground the formation and maintenance of close intimate ties throughout life (Bowlby, 1980). Childhood experiences that disrupt trust and security may then contribute to relationship difficulties across the life course (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990; Mickelson, Kessler, & Shaver, 1997; Shaw & Krause, 2002).

Exposure to childhood adversity may be the first step in a long process of stress proliferation in central relationships of adulthood, particularly those with intimate partners and children. This may occur because individuals develop certain ways of coping with childhood adversity that may be at least partially adaptive in dealing with childhood stress but then later interfere with the formation and maintenance of close relationships in adulthood. For example, children may attempt to cope with adversity by withdrawing from stressful social situations. This coping strategy might be somewhat effective in reducing the stress of childhood adversity yet, if continued into adulthood, withdrawing in the face of stress may impose strain in intimate relationships.

Men’s Relationships in Adulthood and Racial Inequality: A Stress and Life Course Perspective

Central to a life course perspective on social stress (Pearlin & Skaff, 1996) is the recognition that structural disadvantage produces differences in exposure and vulnerability to stress with consequences for inequalities in well-being later in life. Building on a stress and life course perspective, we emphasize that race, as a structural system of inequality (Sternthal, Slopen, & Williams, 2011; Williams & Mohammed, 2013), is central to the experience of childhood adversity that then has consequences for men’s close relationships throughout life. Reflecting systems of discrimination, including racial segregation, which contribute to higher rates of poverty and other hardships among black families, black children are more likely than white children to live in poverty and to experience a range of additional stressors throughout childhood (Child Trends Data Bank, 2013; Williams & Mohammed 2013). Black youth are more likely than their white counterparts to live in disadvantaged and dangerous neighborhoods (Peterson & Krivo, 2005), to witness or experience violence (Buka, Stichick, Birdthistle, & Earls, 2001), and to experience discrimination in schools, stores, and daily encounters (Grollman, 2012). In sum, racial differences in stress exposure begin early in life and continue throughout the life course, with likely consequences for the quality of relationships later in life.

Although some studies find higher (Taylor, Chatters, Woodward, & Brown, 2013) or similar levels (Kiecolt, Hughes, & Keith, 2008; Mouzon, 2013) of support in the relationships of black family members compared with those of white families, most research suggests greater strain in black family relationships (Mouzon, 2013, but see also Kiecolt et al., 2008) and lower marital quality among black compared with white spouses (Broman, 2005; Bulanda & Brown, 2007). Recent longitudinal evidence also shows that black Americans’ close relationships with family and friends are characterized by higher levels of strain, on average, compared with white Americans’ (Umberson et al., 2014). These differences in relationship strain are hypothesized to be due to the greater structural strains black families experience in adulthood, such as discrimination and higher rates of unemployment and poverty. However, we argue, in line with recent longitudinal evidence (Umberson et al., 2014), that differential exposure to childhood adversity may also shape racial differences in family relationships in mid to late adulthood.

In sum, despite evidence that childhood adversity is linked to strain in men’s adult relationships, we lack an understanding of the underlying processes that unfold over the life course to link childhood experiences to men’s relationship strain later in life, and how such processes may be unique for black men. The primary goal of the present study, then, is to develop a conceptual model of the psychosocial processes and behavioral coping responses through which childhood adversity influences men’s relationships with intimate partners and children in adulthood, with consideration of the different life course experiences of black men compared with white men.

Methods

We recruited 30 men from a large metropolitan area in the Southwestern United States to participate in in-depth interviews between 2008 and 2009. Participants were recruited through listservs, distribution of fliers to local groups (e.g., African American chambers of commerce and senior centers) and in public spaces (e.g., coffee shops, libraries, and barber shops), and snowball sampling techniques. Phone screening ensured that participants were selected with attention to sample composition, with an equal number of black and white respondents distributed across multiple ages, with relative similarity across groups by socioeconomic and marital status. Interviews were conducted in person, lasted one and a half hours on average, and consisted of open-ended questions directed toward understanding relationship and health processes over the life course. All interviewers were white women with experience interviewing diverse populations. We conducted and analyzed interviews with awareness that men, and particularly men of color, might filter or shape their narratives in response to the gender/race of interviewers (Corbin Dwyer & Buckle, 2009). This is a particular concern in that racial discrimination and past mistreatment of racial minorities in research may contribute to mistrust in researchers in ways that influence both who volunteers to participate in this study and how participants respond to interview questions. We conducted interviews with sensitivity to these possibilities and treat the data as narratives provided by respondents in light of possible concerns they may have had about the interview process.

An interview guide that included semistructured questions ensured that major conceptual issues were covered. For example, participants were asked about sources of stress across the life course and adult relationships including when they had children, contact with children, entering/exiting serious intimate relationships, the quality of those relationships, as well as ways of coping with stress throughout the life course. Interview questions were first tested and refined in pilot interviews; subsequent interviews (analyzed for the present study) used the edited and tested interview guide. Interviews were conducted in a private location chosen by the study participant and were recorded and transcribed. Pseudonyms were assigned to maintain confidentiality. A short close-ended questionnaire was used to obtain information on basic background characteristics of respondents (Table 1). The analytic sample included 15 black men and 15 white men. The mean age was 54.7 years, mean household income was about $47,000, and all but two respondents had some college education. Black respondents were slightly younger than white respondents on average and slightly less likely to have completed a college degree, but, due to an intentional sampling strategy, the average income of each group was similar. Within each group, about 40% of the men were currently married.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents (as reported by respondents)

| Black men | White men | Total sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years) | 51.1 | 58.2 | 54.7 |

| Education | |||

| High school | 13.3% | 0% | 6.7% |

| Some college | 40% | 26.7% | 33.3% |

| College degree | 46.7% | 60% | 53.3% |

| Graduate degree | 0% | 13.3% | 6.7% |

| Income (mean) | $47000 | $47000 | $47000 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 40% | 40% | 40% |

| Cohabiting | 6.7% | 0% | 3.3% |

| Never married / Single | 6.7% | 20% | 13.3% |

| Divorced once | 13.3% | 26.7% | 20% |

| Divorced more than once | 33.3 % | 6.7% | 20% |

| Widowed | 0% | 6.7% | 3.3% |

| Number of children (mean) | 2.6 | 1.3 | 1.97 |

| Employment status | |||

| Part-time | 20% | 20% | 20% |

| Full-time | 53.3% | 40% | 46.7% |

| Retired | 0% | 33.3% | 16.7% |

| Unemployed/Unreported/Disabled/Other | 26.7% | 6.7% | 16.7% |

| N = 15 | N = 15 | N = 30 | |

Analytic Strategy

In line with our intention to use the data both to explore processes suggested by the literature and to pursue open-ended exploration of other potential processes, we blended a priori and inductive approaches (Miles & Huberman, 1984). This approach goes beyond description to evaluate conceptual linkages and build theoretical insights. We focused on childhood adversity and its implications for adult relationships. Two of the authors independently coded these qualitative data using Nvivo (2012) software, first reading through all of the transcripts and field notes multiple times. We excerpted all data that described difficult, stressful, or traumatic childhood conditions and the quality of adult relationships. We performed initial coding, creating codes for childhood adversity, responses to childhood adversity, and adult relationships. For example, we created codes for types of childhood adversity described by respondents (e.g., poverty, neighborhood violence, and parental drug/alcohol abuse). Next we performed “focused” coding, combining smaller codes into larger ones and examining the connections between codes in order to develop our conceptual model. These focused codes organize the results sections. Finally, we systematically examined the distribution of respondents within codes by race and examined processes underlying the experiences of childhood adversity for the relationships of black men and white men. In this final stage of analysis, we explored linkages between childhood stressors, responses to childhood stressors, and adulthood relationship experiences, noting both implicit and explicit connections between these two arenas. For example, we systematically examined whether men who talked about experiencing childhood adversity and social isolation in childhood also talked about feeling isolated in their adult relationships and then linked these constructs in our analysis. In addition, respondents sometimes explicitly linked their childhood experiences to their adult relationships.

Results

The primary goal of this qualitative analysis is to increase understanding of the major psychosocial and behavioral processes through which childhood adversity may contribute to relationship strain among men later in life. The most common themes of childhood adversity as described by respondents include poverty, violence and abuse, alcohol or drugs in the household, relationship loss/disruption (e.g., separation from a parent and death of family members), and neglect. Paralleling national data (Child Trends Data Bank, 2013; Umberson et al., 2014; Warner & Hayward, 2006), black men in our study are more likely than white men to describe experiences of childhood adversity. About half of the white men in the sample do not describe any childhood adversity, whereas all but one black male respondent describe adversity, with the majority of black men describing at least three major stressors in childhood. In general, the childhood adversity described by white men was more temporary and less extreme than the childhood adversity described by black men. However, we do not find major differences in how black men and white men describe reactions to childhood adversity or in how childhood adversity appears to influence relationships in adulthood. Because white men were less likely than black men to experience childhood adversity, the excerpts we present below in describing processes linking childhood adversity to family relationships in adulthood are drawn more heavily from interviews with black men. We now turn to the major themes from our analysis of how childhood adversity seems to shape lifelong patterns that may influence relationships in adulthood. Based on our analysis, we develop a conceptual model of how childhood adversity may shape adult relationships with intimate partners and children.

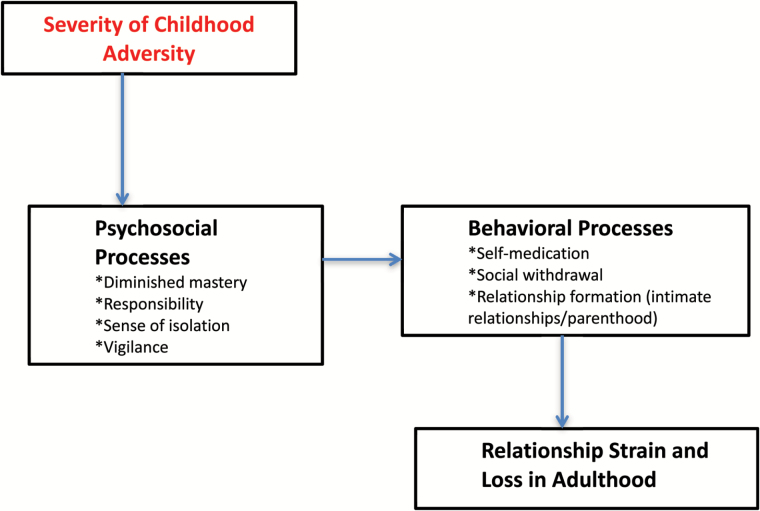

Psychosocial Processes: Childhood Adversity and Sense of Self

Our analysis suggests that childhood adversity influences respondents in a number of ways that may shape the quality of relationships throughout life. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model that summarizes key themes from the analysis and suggests that childhood adversity influences study participants’ sense of self in several ways that may be carried forward through the life course: (i) a sense that one has little mastery over life circumstances, (ii) early and extreme feelings of responsibility for self and others, (iii) a sense of social isolation, and (iv) a need to remain vigilant for external threats. In turn, our analysis demonstrates that these aspects of self are associated with characteristic psychosocial and behavioral responses that persist from childhood into adulthood and contribute to relationship strain though mid to later life (described later). These responses seem to occur among black men and white men, though more so among black men as they report greater childhood adversity.

Figure 1.

Thematic linkages of childhood adversity and relationships in adulthood.

Diminished Mastery

Our analysis suggests that respondents who grew up with high levels of childhood adversity and chronic stress learn early on that they have little control over their life circumstances, and this diminished sense of mastery is often carried over into adulthood. Childhood adversity was typically described by respondents in ways suggesting that nothing could have been done to alter their stressful childhood circumstances. Because black men are much more likely to describe experiencing chronic stress in early childhood, this theme is more prevalent for them, though this process was also described by a few white men. Karl (black, age 61 years) talks about the inability to control his circumstances when he says of growing up without his parents: “I didn’t have any feelings…. I didn’t grow up like, ‘Why isn’t my mother here? Why isn’t my daddy here?’” Similarly, Terry (black, age 41 years) who was raised by his grandmother says, “You still want to know what it would have been like to be around your mother [but] you can’t go and change that.”

It should be noted that once children became old enough to impose change over their life circumstances, many attempted to do so, demonstrating personal agency. Many men describe deliberate efforts to cope with their childhood circumstances, particularly during adolescence, whether that meant running away from home, getting a job, or taking drugs. These efforts may have meant escaping stressful childhood circumstances at least temporarily and, in this sense, may have been partly adaptive in coping with adversity. However, the fundamental sense of low mastery over the conditions of life seems to carry over into adulthood. For example, respondents who grew up with diminished mastery often talk about the poor quality and disintegration of their adult relationships as inevitable and not under their control. Jared (black, age 31 years), who does not see his son (born when Jared was in college) anymore, says, “It’s my situation, and I’ve come to accept it. I understand. It’s not like I want it to be, but it’s just the way it is. There’s not much I can really do about it.”

Responsibility for Self and Others

Under circumstances of significant childhood adversity, men often described how they assumed or were assigned responsibilities that most people would not associate with childhood, such as seeking paid work to support themselves and their families. One third of the black men in our sample went to work when they were children. Mark (black, age 57 years) did so when he realized that others would not be providing for him: “I started working my first job when I was thirteen years old. I worked a part-time job washing dishes…. And that was kind of how life was from that point forward.” One white man in our sample describes working in childhood to help support his family. George (white, age 47 years) describes: “My father’s death. And I was 11 then. That’s when I started working. I went to work when I was 11. And I started delivering newspapers and doing other things. And then I moved into the mechanical departments at 12 at the newspaper. I was setting type and doing the presswork and all that kind of stuff.”

In addition to seeking employment, early responsibilities sometimes involved protecting others, as when James (black, age 42 years) comforted and cared for his younger sister after their father sexually abused her. James was also physically abused by his father. He recalls, “[My father] came up after he got out of jail and then [my mother] informed us that she was thinking of letting him move back in…. He used to beat me with extension cords and stuff like that. My mother used to come in and I would have blood all on my back.” In order to keep his father from moving back in with the family, James began contributing financially to support his mother and sister. He says, “I manned up then and that’s when I started working. I was thirteen.”

Social Isolation

Men who describe high levels of childhood adversity often talk about being on their own or having a caregiver who was overwhelmed by poverty or other difficult circumstances. For most white men, even if they experienced the death of a loved one or a strained relationship with a parent, they tend to describe less social isolation than black men. For example, Jim (white, age 68 years) was 4 years of age when his father died. Jim was raised by his mother and two sisters, and says his mother “kind of tried to overcompensate.” Thus even though Jim did not know his father, he still had caregivers who were not themselves overwhelmed by stressful life circumstances. The higher levels of childhood adversity experienced by black men reflect structural conditions that caused stress for everyone in the family, so that social safety nets were quite thin. Notably, black men often talked about being surrounded by family members during childhood yet how they still felt socially isolated—an experience of being “alone together” in a family. Doug (black, age 55 years) rarely saw his mother because she was very ill or his father because “he worked all the time…he didn’t have a lot of time at home.” Doug also says he did not have a close relationship with any of his nine siblings:

My oldest brother, he was gone by the time I was old enough to realize he was in the military and then the brother next to him, he was athletic. And then the other two after that, they worked, man, you know, because there just wasn’t money… So they started working when they were thirteen years old. And then my brother next to me, he got into the criminal element when he was in elementary school… I didn’t get to see him much because he stayed in juvenile detention.

Vigilance

Childhood adversity tended to be described as chronic and evoking a feeling that one must remain vigilant for the ever-present yet unpredictable threat of stress, loss, neglect, and even violence. This was a more common theme among black men, as their levels of childhood adversity were much higher and more constant than white men’s. Phil (black, age 64 years) says he learned from an early age to be ever vigilant against physical threats: “Like my first day at school, I saw a guy get killed. [A guy] broke a bottle, cut his throat. That was tough. They hung the guy up on the fence and he died on the fence.” Phil says he responded to this experience by becoming “defensive in nature.” Several black men describe how force and violence finally allowed them to gain some control after they got old enough to fight back. Phil was abused by his father and describes this turning point:

And you just don’t take any stuff. That’s how I was able to get to my old man and put it to him. I could take it, baby, and I knew it and he knew it too. That’s after so many fights and stuff. So here it is. It gives you drive. You can take a lot of stuff.

Behavioral Processes Linking Childhood Adversity and Psychosocial Processes to Relationships in Adulthood

The analysis yielded three recurring themes of behavioral processes through which childhood adversity may influence relationship patterns in adulthood: (i) self-medication, (ii) withdrawal from others, and (iii) early initiation of intimate relationships and parenthood. These responses follow from the underlying psychosocial processes summarized in Figure 1; these responses are ways of escaping the stress of childhood adversity, and each has implications for relationships throughout life. These pathways are discussed more often by black men than white men, both in terms of how many black men identified these pathways and how often these pathways were repeated across the life course.

Self-Medication

In response to the chronic stress of childhood adversity, many men (black and white) describe how they began to smoke, drink, and take drugs at a young age. These behaviors may provide some relief in the short run (and, in this sense, are effective coping responses), but they typically take a toll on relationships in the long run. Short-term relief comes in the form of pleasure seeking, social connection, and escape from stress. Karl had two alcoholic parents and began to drink with friends around age twelve. Karl describes himself as addicted to drugs and alcohol by the time he was an adult. Similarly, Doug, who began working to support his family at the age of eleven after his grandmother died, was also drinking heavily and taking drugs to cope with the stress of living by age twelve:

When I started using…the drugs took everything else away. You didn’t concentrate on anything that was negative. You just enjoy being high and so you have a tendency to cover up what you are feeling with substances. You learn how to survive the pain with that—the pain of life, anyway.

Jim, who lost his father during early childhood, says, “When I was growing up, I had no close male relationships other than friends my own age…. It affects your outlook.” Jim began drinking heavily in his 20s and was eventually hospitalized for his addiction. George (white, age 47 years), who began drinking heavily in his 20s and 30s, says, “In my teens I realized that when my dad drank he got angry. Then looking at his father and my uncle and seeing how much they consumed, I started to realize that this was an issue with my family and that I needed to watch out for it. And I didn’t do a very good job.”

Respondents describe how substance abuse creates more stress, turmoil, and instability in their relationships with intimate partners and children—often leading to additional relationship losses. Indeed, the sheer number of divorces and relationship breakups reported by black men in our sample stands in contrast to the white men (paralleling national statistics). Almost half of the black men in our sample report two or more divorces, whereas only two white men report more than one divorce. For example, after drugs led to divorce and time in prison, Doug decided to move to a new city with a new girlfriend, but alcohol abuse led to yet another breakup: “I wasn’t shooting heroin, but I was drinking alcohol, which has the same effect… so our relationship didn’t last a long time.” Billy (black, age 52 years) was divorced four times and describes how his expectations and desires to be a husband and father were incompatible with his drug use: “The reason why it never worked was because I was doing things I shouldn’t have been doing, such as using drugs, drinking, smoking, running clubs, running with the wrong guys.”

Withdrawal From Others

An early sense of responsibility and isolation may also carry over into adult relationships by leading to withdrawal from others during times of stress. None of the white men we interviewed discuss social isolation as a dominant feeling in childhood. In contrast, several of the black men report feeling this way. These feelings of isolation have important implications for adult relationships. Barry (black, age 60 years) says:

I was just used to being isolated. When my mother and dad got divorced, instead of me talking about it to anybody, my brothers and stuff like that, I just felt like I was on the street. I didn’t feel like I was part of a family.

Learning to cope with a sense of isolation is difficult to cast off once in adult intimate relationships. This can extend to relationships with children as well as intimate partners. Barry says, “I didn’t like myself. As a father, I felt isolated from my son. We have had to really work to restore some of those bonds, even today. I was just used to being isolated.” Allen (black, age 78 years) has been divorced three times and says this occurred in part because of poor social skills he developed as a child when, despite having seven siblings: “Playing and social interaction…was foreign.” Terry recalls how childhood experiences did not prepare him to seek or receive support from others when he needed it: “I always had people I knew, like friends, to talk to, but never when I was real down.” The isolation in adulthood was compounded for black men who did not feel connected to their families and then moved into majority white adult environments where they felt even more isolated. Barry attended a majority white college and says of being a black student there, “None of us felt like we belonged….We didn’t get the kind of support that black students get on black college campuses….It was so big and so damn impersonal…. I had no real family life. No place in college to call home.”

Early Initiation of Intimate Relationships and Parenthood

In the context of childhood adversity, some men say they sought to establish new family ties at a very young age, initiating intimate relationships in adolescence and wanting to have children of their own. Many young black men in our sample had children during their teenage years (paralleling national statistics). When Jared’s girlfriend became pregnant, he dropped out of school to find a job: “We lived together all through the pregnancy. I basically quit going to school and was working fulltime, … but I couldn’t manage it.” James, who became a father at age 14, says of balancing parental responsibilities with being a high school student: “I was taking [the baby] to class because her mama wanted to run the streets rather than be a parent…. Teachers would let me sit in class with my baby while I went to school.” Men described their motivation for early relationships arising partly from the desire to create new connections in response to the social isolation and stress of childhood. Billy (black, age 52 years) says, “Growing up, I always thought that to become a man you had to go have a baby and be with that person and raise that child. It never lasted, it never worked out. So I would try again.”

A sense of responsibility for self and others in childhood may add to a sense of feeling overburdened by adult responsibilities. Reflecting this burden, several black men described a longing to be free from responsibility for others, a desire that sometimes caused them to push intimate partners away. Billy says, “I was always involved in a relationship…. I would usually leave because I was good at running away. I would always run away. A lot of times I would run away and end up somewhere else. Run into someone else’s arms to comfort me.” Karl says, “My divorces weren’t about my wives, they were about me…. So the stability wasn’t there for me. Like I said, I had great wives. They were great women. It was just me…. I wasn’t really stable. I was still wanting to be free.” Men who experienced little childhood adversity were more likely to marry and have children in their mid-20s or later. For example, Timothy (black, age 36 years), who experienced the least childhood adversity of any of the black men in the sample, married his college girlfriend when he was 28 years old and describes their marriage as “very enjoyable.” Mitch (white, age 48 years) says of his relationships, “I did a little dating in high school, not much. Mostly both of my parents were like, ‘women are trouble so stay away until you’re older and you get through school and maybe you start your career.’ And I listened to that.”

Discussion

Supportive family relationships throughout the life course are a key predictor of successful aging—which includes low risk of disease and disability, high mental and physical functioning, and continued engagement with life (Rowe & Kahn, 2015). If supportive, relationships can be a tremendous resource, contributing to better quality of life as well as enhanced mental and physical well-being throughout life. However, if strained, relationships undermine the quality of life and impose measurable damage on health and well-being, especially at older ages (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, 2006). Decades of research establish childhood adversity as a fundamental determinant of well-being throughout the life course (Shonkoff et al., 2012), and growing evidence suggests that childhood adversity plays an important role in shaping men’s—especially black men’s—social relationships in mid to late adulthood (Umberson, et al., 2014). Building on a life course perspective of social stress and drawing on qualitative data from in-depth interviews with 15 black men and 15 white men, we develop a conceptual model of the psychosocial and behavioral processes that unfold over the life course to link childhood adversity to strain in family relationships throughout the life span. Our sample allowed us to explore whether the patterns we observe may be more or less relevant for black or white men, an important focus given that structural systems of inequality disproportionately expose black men to high levels of stress throughout life with implications for late-life well-being (Williams, 2003).

Our central conclusion is that childhood adversity—especially when severe—triggers several psychosocial and behavioral responses that may initially help children to cope with the stress of early life adversity but are generally disadvantageous in adulthood in that they interfere with the formation and maintenance of close family relationships. Psychosocial responses to childhood adversity include diminished mastery over life circumstances, a sense of responsibility for self and others, feelings of social isolation, and chronic vigilance. As a result of their greater exposure to childhood adversity, young black men are particularly likely to take on adult responsibilities at young ages, to remain ever vigilant for unexpected threats in their daily lives, and to feel little control over their circumstances. Taking on adult responsibilities at young ages prompts feelings of not being able to rely on others and fosters a sense of social isolation for children, even when around other family members. Further, recent evidence points to the chronic exposure to structural racism and discrimination that black men face throughout life, including racial profiling and the need to be ever vigilant for the possibility of violence (Thomas & Sha’Kema, 2015). Previous studies show that heightened vigilance activates psychological and physiological arousal that takes a toll on relationships (Repetti et al., 2002). Childhood adversity may launch a long process of environmental insults accumulating across the life course to produce cumulative disadvantage over time, disproportionately affecting black men (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh 2002; Warner & Hayward, 2006).

Our findings suggest three primary behavioral processes through which childhood adversity may influence men’s relationships from early to late adulthood. These behavioral processes launched early in the life course have important implications for aging and late-life health, including late-life health disparities. First, some men respond to childhood adversity by engaging in early-onset use of drugs and alcohol as a way to self-soothe, escape reality, and connect to others (Williams, 2003). Other studies have pointed to the early-onset of risky health behavior for disadvantaged children (Repetti et al., 2002), and early substance abuse is strongly associated with later life risk for substance abuse (Platt, Sloan, & Costanzo, 2010). For the men in our sample, risky health behaviors such as drug and alcohol use seem to foster additional disadvantage because they contribute to stress in intimate and family relationships in adulthood and increase the risk of relationship loss. The stress proliferation stemming from responses to adversity in childhood can then lead to the accumulation of greater social disadvantage as men age. The deleterious physical and social effects of lifelong substance and alcohol abuse accumulate over time, contributing to poorer physical health, more social isolation, and even greater cognitive decline among men who abused drugs and alcohol throughout the life course (Anttila et al., 2004). Indeed, past research shows that health behaviors launched early in life have consequences for later life health (Ferraro & Shippee, 2009; Ferraro, Su, Gretebeck, Black, & Badylak, 2002; Pudrovska & Anishkin, 2012) and heavy drinking and drug use contribute to relationship dissolution (Reczek, Pudrovska, Carr, Thomeer, & Umberson, in press).

Second, under conditions of high childhood adversity, the men in our study reported a strong desire for family connection and stability. This often led to the formation of intimate unions, as well as parenthood at a young age. As previous studies find, intimate relationships formed in adolescence are highly unstable (Ogolsky, Lloyd, & Cate, 2013), and these new relationships impose additional responsibilities and stress that contribute to more stress, relationship conflict, and relationship loss. Early parenthood—particularly teenage parenthood—has long-term effects, contributing to greater risk of depression, worse self-rated health, more activity limitations, and increased mortality at older ages (Henretta 2007; Mirowsky and Ross, 2002; Spence 2008; Taylor 2009). Past studies also show that multiple marriages and breakups increase risk of chronic conditions, mobility limitations, and mortality risk in later life even if remarried (Henretta, 2010; Hughes and Waite, 2009). Third, men’s experiences of childhood adversity and psychosocial responses to the resulting stress contributed to psychological and physical withdrawal from the stress and burden of relationships in adulthood, leading to additional relationship losses and social isolation throughout the life course. Social isolation is associated with health-risk behaviors as well as high blood pressure and C-reactive protein among older adults (Shankar, McMunn, Banks, & Steptoe, 2011), and these negative effects may be even more salient among those with chronic histories of social isolation (Machielse, 2015). Thus, experiencing adversity in childhood can set in motion processes that compromise adult relationships and lead to the accumulation of further disadvantage in later life.

The key difference in narratives by race is the more prevalent, severe, and chronic childhood adversity for black men than for white men, a pattern that parallels findings in nationally representative data (Child Trends Data Bank, 2013; Umberson et al., 2014; Warner & Hayward, 2006). Although black respondents reported more persistent, repeated, and higher levels of childhood adversity than whites, they rarely referred specifically to racism or racial inequality as the source of their adversity. However, it is important to keep in mind that many of the specific sources of adversity mentioned by respondents (e.g., poverty, violence, and separation from parents) reflect broader patterns of structural inequality on the basis of race (Williams & Mohammed, 2013). Our in-depth interviews tell a story of immense adversity in childhood for black men, within the context of structural disadvantages that shape their childhoods and early family lives, with cascading consequences for relationships at older ages and, in turn, implications for racial disparities in health and well-being across the life course. We contribute to the cumulative disadvantage literature by using qualitative data to illuminate life course processes that link childhood adversity to adult family relationships, with implications for racial inequalities at older ages.

Past studies have tended to emphasize either economic adversity in childhood or global measures of childhood adversity that incorporate a range of adversities. Future studies should consider the possibility that the persistence of specific types of adversity (economic, family strains, violence, and abuse) may operate through distinctly different pathways to influence different types of outcomes or that these linkages vary by race. The specificity offered by a more nuanced approach is essential to the development of focused policy and intervention strategies, some of which should be targeted toward children in order to prevent adverse consequences that continue to influence adults through later life and some of which should be targeted toward older populations who are at particular risk stemming from their childhood experiences. Our findings clearly point to the importance of considering the implications of race differences in repeated and chronic exposure to early life adversities and how the greater exposure of black children to early adversity has lifelong implications for the relationships of black men. In turn, as recent research shows, race differences in relationships contribute to cumulative disadvantage in the health of black men through mid and later life (Umberson et al., 2014).

Evidence that childhood adversity contributes to strain in black men’s adult family relationships stands in stark contrast to cultural explanations that pathologize the family relationships of black men. Rather, the preponderance of the evidence supports a structural resiliency approach emphasizing that differences in black and white family ties arise from structural differences in education, income, and wealth as well as institutional and individual discrimination processes that begin early in the life course (Sarkisian & Gerstel, 2004). It is clear that stress exposure takes a toll on the very coping resources that facilitate resilience to stress (e.g., a sense of personal mastery over life circumstances) and the many disadvantages that minority groups face also extend to coping resources (see Thoits, 2010). Further, gendered systems of masculinity encouraging strength, independence, and controlled emotions that can generally threaten men’s relationships may be further exaggerated among black men who face structural impediments in expressing other forms of masculinity such as through economic success (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Although we have focused primarily on childhood adversities in relation to adult relationships, future research should also focus on childhood resources that contribute to resiliency through old age. A growing body of research in gerontology focuses on factors that contribute to successful aging (Rowe & Kahn, 2015). Indeed, literatures on childhood (Wright, Masten, & Narayan, 2013) and older age resiliency (Rowe & Kahn, 2015) emphasize the importance of close relationships as contributing to resiliency. Moreover, some of this research, as well as findings of the present study, indicate that maladaptive behaviors at one age may actually be adaptive at a later point in time (Wright et al., 2013). Our research points to an important need for collaborations between child development researchers and gerontologists, to provide an interdisciplinary perspective on childhood and aging that highlights both the changing and compounding roles of adversity and resilience throughout the life course.

Limitations

The generalizability of our findings is limited by the small, purposive sample used for the analysis. These findings suggest new theoretical propositions that should be tested with larger, more representative samples and quantitative methods. Our analysis of childhood adversity relies on adults’ retrospective reports that may be limited to more severe events that are easier to recall, and with limited estimation of duration and timing of events (Avison, 2010). Yet, the validity and reliability of retrospective reports of childhood and early life experiences are generally supported by previous studies (Hardt & Rutter, 2004; Schwarz & Sudman, 1994). Additionally, connections between themes (illustrated in Figure 1) are based on a systematic analysis of the data, but it is likely that there are alternative explanations for adult relationship experiences beyond childhood adversity. These additional pathways are beyond the scope of this current study and analytic strategy, but future research should consider contemporaneous explanations for adult relationship disadvantages. Likewise, analyzing age and cohort differences in race and the link between childhood adversity and later life relationships was beyond the scope of the present study, and our findings should be interpreted within the context of this limitation. However, this is an important direction for future research. In addition, because our sample is composed of individuals who are willing to talk with researchers, there may be selection against the inclusion of black respondents who have experienced institutional and personal racism. Similarly, all of the interviewers were white women, and responses may differ for interviews conducted by interviewers of different races and genders (Oyinlade & Losen, 2014). Our goal was to present an understanding of the adverse childhood experiences of black men and white men and how those experiences have shaped their relationships throughout the life course—and to allow men to describe those experiences in their own words. However, we recognize that race and gender shape social interactions in ways that may have influenced sample composition and interpretation of data. This influence may have encouraged or discouraged fuller disclosure about childhood and later life experiences, but we are not able to assess this influence. Further, our emphasis was on adverse childhood experiences; future qualitative and quantitative research may consider positive childhood experiences as a path to identify privileges and resources that enhance adulthood relationships and health, considering cumulative advantage alongside cumulative disadvantage. In addition, although our sample includes equal numbers of blacks and whites with similar average income and marital status, the education levels were higher than the population averages for black Americans; the most likely consequence of this is we understate levels of childhood adversity and its consequences for black study participants.

Conclusion

Life course theory and previous quantitative research suggest the importance of early life events and adversity for later life relationship quality, with implications for successful aging. Yet research also shows that childhood experiences are diverse, and childhood adversity is more prevalent in the lives of black children. By considering qualitatively the experiences of black and white men and focusing on possible variations in their life course experiences, our research sheds light on a missing piece of the puzzle of why black men have more strained relationships than white men. The greater childhood adversity experienced by black men often stems from structural disadvantage associated with race in America (Warner & Hayward, 2006). Relationships in adulthood are not mere matters of personal choice but reflect a lifetime of exposure to environmental adversity that constrains the opportunities and choices available to individuals (Palloni, 2006; Warner & Hayward, 2006). Institutional racism, stress, and discrimination directly impose adversity on black men across the life course (Williams, 2003; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). This adversity begins in childhood and may have lasting negative consequences for men’s relationships (Umberson et al., 2014)—consequences that may partly explain stark racial disparities in family formation and stability (Phillips & Sweeney, 2006), as well as racial disparities in health prevalent among older men in the United States (Umberson et al., 2014; Warner & Brown, 2011). Future research should use an intersectionality framework to consider women’s lives as linked to and distinct from men’s lives, continuing to build on our life course understanding of the ways in which childhood adversity shapes relationships throughout the life span.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R01AG026613, PI: D. Umberson), a career award from the National Institute on Aging (K01AG043417, PI: H. Liu), and a center grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin (R24 HD042849; PI, Mark Hayward).

Acknowledgments

D. Umberson planned the study, supervised and participated in the data analysis, and wrote the initial paper. M. Thomeer participated in data collection and data analysis and helped with conceptualization as well as writing and revision of the paper. K. Williams, P. A. Thomas, and H. Liu participated in conceptualization, writing, and revision of the paper.

References

- Anttila T. Helkala E. Viitanen M. Kåreholt I. Fratiglioni L. Winblad B. Soininen H. Tuomilehto J. Nissinen A., & Kivipelto M (2004). Alcohol drinking in middle age and subsequent risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in old age: A prospective population based study. British Medical Journal, 329, 539–544. doi:10.1136/bmj.38181.418958.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avison W. (2010). Incorporating children’s lives into a life course perspective on stress and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51, 361–375. doi:10.1177/0022146510386797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y., Kuh D. (2002). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 285–293. doi:10.1093/ije/31.2.285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. 1980. Attachment and loss: Loss, sadness and depression (Vol. 3). New York, NY: Basic. [Google Scholar]

- Broman C. L. 2005. Marital quality in black and white marriages. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 434–441. doi:10.1177/0192513X04272439 [Google Scholar]

- Buka S. L., Stichick T. L., Birdthistle I., Earls F. J. (2001). Youth exposure to violence: Prevalence, risks, and consequences. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71, 298–310. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.71.3.298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulanda J. R., & Brown S. L (2007). Race-ethnic differences in marital quality and divorce. Social Science Research, 36, 945–967. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.04.001 [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends Data Bank. (2013). Adverse experiences: Indicators on children and youth. Bethesda, MD: http://www.childtrends.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/07/124_Adverse_Experiences.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W., & Messerschmidt J. W (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19, 829–859. doi:10.1177/0891243205278639 [Google Scholar]

- Corbin Dwyer S., & Buckle J. L (2009). The space between: On being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge K. A. Bates J. E., & Pettit G. S (1990). Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science, 250, 1678–1683. doi:10.1126/science.2270481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. H. Jr. Johnson M. K., & Crosnoe R (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In Mortimer J. T., Shanahan M. J.(Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1 [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro K. F., & Shippee T. P (2009). Aging and cumulative inequality: How does inequality get under the skin? Gerontologist, 49, 333–343. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro K. F., Su Y. P., Gretebeck R. J., Black D. R., Badylak S. F. (2002). Body mass index and disability in adulthood: A 20-year panel study. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 834–840. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.5.834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer R., Stansfeld S. A. (2002). How gender affects patterns of social relations and their impact on health: A comparison of one or multiple sources of support from “close persons”. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 54, 811–825. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00111-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G. C. Walsemann K. M., & Brondolo E (2012). A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 967–974. doi:10.2105/ajph.2012.300666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grollman E. A. (2012). Multiple forms of perceived discrimination and health among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 199–214. doi:10.1177/0022146512444289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J., & Rutter M (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 260–273. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch S. L. (2005). Conceptualizing and identifying cumulative adversity and protective resources: Implications for understanding health inequalities. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60B, 130–134. doi:10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henretta J. C. (2007). Early childbearing, marital status, and women’s health and mortality after age 50. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48, 254–266. doi:10.1177/002214650704800304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henretta J. C. (2010). Lifetime marital history and mortality after age 50. Journal of Aging and Health, 22, 1198–1212. doi:10.1177/0898264310374354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. E., Waite L. J. (2009). Marital biography and health at mid-life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50:344–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt K. J. Hughes M., & Keith V (2008). Race, social relationships and mental health. Personal Relationships, 15, 229–245. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00195.x [Google Scholar]

- Kogan S. M. Lei M.-K. Grange C. R. Simons R. L. Brody G. H. Gibbons F. X., & Chen Y-F (2013). The contribution of community and family contexts to African American young adults’ romantic relationship health: A prospective analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 878–890. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9935-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machielse A. (2015). The heterogeneity of socially isolated older adults: A social isolation typology. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 58, 338–356. doi:10.1080/01634372.2015.1007258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S., & Percheski C (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134549 [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson K. D., Kessler R. C., Shaver P. R. (1997). Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 1092–1106. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M. B., & Huberman A. M (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. E. Chen E., & Parker K. J (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 959. doi:10.1037/a0024768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J., Ross C. E. (2002). Depression, parenthood, and age at first birth. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 54, 1281–1298. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00096-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouzon D. M. (2013). Can family relationships explain the race paradox in mental health? Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 470–485. doi:10.1111/jomf.12006 [Google Scholar]

- NVivo qualitative data analysis software. (2012). QSR International, version 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ogolsky B. G. Lloyd S. A., & Cate R. M (2013). The developmental course of romantic relationships. New York, NY: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203383094 [Google Scholar]

- Oyinlade A. O., & Losen A (2014). Extraneous effects of race, gender, and race-gender homo-and heterophily conditions on data quality. SAGE Open, 4. doi:2158244014525418. [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A. (2006). Reproducing inequalities: Luck, wallets, and the enduring effects of childhood health. Demography, 43, 587–615. doi:10.1353/dem.2006.0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L.I. (2010). The life course and the stress process: Some conceptual comparisons. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 65B, 207–215. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Schieman S., Fazio E. M., Meersman S. C. (2005). Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 205–219. doi:10.1177/002214650504600206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Skaff M. M. (1996). Stress and the life course: A paradigmatic alliance. The Gerontologist, 36, 239–247. doi:10.1093/geront/36.2.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R. D., & Krivo L. J (2005). Macrostructural analyses of race, ethnicity, and violent crime: Recent lessons and new directions for research. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 331–356. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122308 [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. A., & Sweeney M. M (2006). Can differential exposure to risk factors explain recent racial and ethnic variation in marital disruption? Social Science Research, 35, 409–434. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.04.002 [Google Scholar]

- Platt A., Sloan F. A., Costanzo P. (2010). Alcohol-consumption trajectories and associated characteristics among adults older than age 50. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71, 169–179. doi:10.15288/jsad.2010.71.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudrovska T., & Anishkin A (2012). Early-life socioeconomic status and physical activity in later life: Evidence from structural equation models. Journal of Aging and Health, 25, 383–404. doi:10.1177/0898264312468601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek C. Pudrovska T. Carr D. Thomeer M. B., & Umberson D.(in press). Marital histories and heavy alcohol use among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti R. L., Taylor S. E., Seeman T. E. (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 330–366. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J. W., Kahn R. L. (2015). Successful aging 2.0: Conceptual expansions for the 21st century. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 593–96. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian N., & Gerstel N (2004). Kin support among Blacks and Whites: Race and family organization. American Sociological Review, 69, 812–837. doi:10.1177/000312240406900604 [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N., & Sudman S (1994). Autobiographical memory and the validity of retrospective reports. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-2624-6 [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A. McMunn A. Banks J., & Steptoe A (2011). Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychology, 30, 377–385. doi:10.1037/a0022826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw B. A., Krause N. (2002). Exposure to physical violence during childhood, aging, and health. Journal of Aging and Health, 14, 467–494. doi:10.1177/089826402237179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J. P. Garner A. S. Siegel B. S. Dobbins M. I. Earls M. F. McGuinn L., & Wood D. L (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232–e246. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence N. J. (2008). The long-term consequences of childbearing. Research on Aging, 30, 722–751. doi:10.1177/0164027508322575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal M. J. Slopen N., & Williams D. R (2011). Racial disparities in health. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8, 95–113. doi:10.1017/s1742058x11000087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. L. (2009). Midlife impacts of adolescent parenthood. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 484–510. doi:10.1177/0192513X08329601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. J. Chatters L. M. Woodward A. T., & Brown E (2013). Racial and ethnic differences in extended family, friendship, fictive kin, and congregational informal support networks. Family Relations, 62, 609–624. doi:10.1111/fare.12030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. E. (2011). Social support: A review. In Friedman H. S. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology (pp. 189–214). NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/ 9780195342819.013.0009 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. E., Klein L. C., Lewis B. P., Gruenewald T. L., Gurung R. A., Updegraff J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107, 411–429. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.107.3.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. A. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51, S41–S53. doi:10.1177/0022146510383499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A. J., & Sha’Kema M. B (2015). The influence of the Trayvon Martin shooting on racial socialization practices of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology, 41, 75–89. doi:10.1177/0095798414563610 [Google Scholar]

- Turner R. J. Wheaton B., & Lloyd D, A, (1995). The epidemiology of social stress. American Sociological Review, 60, 104–25. doi:10.2307/2096348 [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., & Montez J. K (2010). Social relationships and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51, S54–S66. doi:10.1177/0022146510383501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Williams K. Thomas P. A. Liu H., & Thomeer M. B (2014). Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage childhood adversity, social relationships, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55, 20–38. doi:10.1177/0022146514521426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., Williams K., Powers D. A., Liu H., Needham B. (2006). You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 1–16. doi:10.1177/002214650604700101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F., & Brown T. H (2011). Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age trajectories of disability: An intersectionality approach. Social Science & Medicine, 72, 1236–1248. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F., Hayward M. D. (2006). Early-life origins of the race gap in men’s mortality. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 209–226. doi:10.1177/002214650604700302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. (2003). The health of men: Structured inequalities and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 724–731. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.5.724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., & Mohammed S. A (2013). Racism and health: I. Pathways and scientific evidence. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 1152–1173. doi:10.1177/0002764213487340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright M. O’D. Masten A. S., & Narayan A. J (2013). Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In Goldstein S., Brooks R. B. (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 15–37). New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_2 [Google Scholar]