Abstract

Objectives:

Passive suicide ideation (PSI) is common among older adults, but prevalences have been reported to vary considerably across European countries. The goal of this study was to assess the role of individual-level risk factors and societal contextual factors associated with PSI in old age.

Method:

We analyzed longitudinal data from the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) on 6,791 community-dwelling respondents (75+) from 12 countries. Bayesian logistic multilevel regression models were used to assess variance components, individual-level and country-level risk factors.

Results:

About 4% of the total variance of PSI was located at the country level, a third of which was attributable to compositional effects of individual-level predictors. Predictors for the development of PSI at the individual level were female gender, depression, older age, poor health, smaller social network size, loneliness, nonreligiosity, and low perceived control (R 2 = 25.8%). At the country level, cultural acceptance of suicide, religiosity, and intergenerational cohabitation were associated with the rates of PSI.

Discussion:

Cross-national variation in old-age PSI is mostly attributable to individual-level determinants and compositional differences, but there is also evidence for contextual effects of country-level characteristics. Suicide prevention programs should be intensified in high-risk countries and attitudes toward suicide should be addressed in information campaigns.

Keywords: Composition, Context, Cross-national, Determinants, Passive suicide ideation

Introduction

In Europe, the lifetime suicide risk increases sharply with age and reaches a peak among people aged 75 years and older (Shah, Bhat, McKenzie, & Koen, 2007). Against the backdrop of a rapid population aging in many European countries, suicide in old age represents a troubling and growing public health issue that has received little attention from public health planners so far (De Leo, Krysinska, Bertolote, Fleischmann, & Wasserman, 2009). Passive suicide ideation (PSI), that is, the wish to die, is part of the established nomenclature of suicide-related behaviors (Silverman, Berman, Sanddal, O’Carroll, & Joiner, 2007) and represents an early stage and potential target of intervention within the continuity of suicidality, ranging from PSI across active suicide ideation, suicide plans, and attempts to actual suicide (Baca-Garcia et al., 2011; Scocco & De Leo, 2002). PSI correlates with less prevalent and more severe active suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and actual suicide (Baca-Garcia et al., 2011; Brown, Beck, Steer, & Grisham, 2000; Scocco, Girolamo, Vilagut, & Alonso, 2008; Suokas, Suominen, Isometsä, Ostamo, & Lönnqvist, 2001; Szanto et al., 1996), and it has been identified as an indicator for psychological distress (Forsell, 2000; Van Orden, Simning, Conwell, Skoog, &Waern, 2013) and found to be predictive of all-cause premature mortality among older adults (Raue et al., 2010).

Estimates regarding the prevalence of PSI among the older population (65+) in Europe range between 5% and 10% (Ayalon, 2011; Fässberg et al., 2014; Rurup, Deeg, Poppelaars, Kerkhof, & Onwuteaka-Philipsen, 2011a; Saïas et al., 2012). Interestingly, the prevalence of PSI varies substantially between European countries. For example, Saïas et al. (2012) found more than twice the proportion of older adults reporting PSI in France (13.2%) as in Denmark (5.5%). These cross-national differences in the desire among elders to die have received only little attention so far, as previous research had exclusively focused on individual-level determinants of PSI—much unlike the cross-national variation in suicide rates that had motivated decades of comparative research ever since the days of Durkheim (1897/1983).

A number of previous studies identified certain individual-level risk factors: female gender, older age, depression, physical illness, functional disabilities, perceived burdensomeness, living alone, low social support, and lack of religious practice (Almeida et al., 2012; Ayalon, 2011; Corna, Cairney, & Streiner, 2010; Cukrowicz, Cheavens, Van Orden, Ragain, & Cook, 2011; Dennis et al., 2009; Fässberg et al., 2014; Rurup et al., 2011a; Saïas et al., 2012). In a qualitative interview study, Rurup and colleagues (2011b) documented that living with age- and illness-related limitations and little perceived control over one’s life, together with the feeling of being useless, were critical for developing a death wish.

In stark contrast to the broad literature on individual-level risk factors, only little is known about country-level differences or contextual risk factors for PSI. Although several recent studies noted a stark cross-national variation of PSI in Europe (Ayalon, 2011; Fässberg et al., 2014; Saïas et al., 2012), none has engaged in explaining them. The central question in this regard is the degree to which this observed cross-national variation might be due to different prevalences of individual risk factors (compositional effects) and/or to country-level characteristics (contextual effects; Diez, 2002). This distinction is important when it comes to developing suicide prevention strategies at the national level. A higher rate of PSI in a country that is due to a higher proportion of older adults with poor health compared with other European countries (compositional effect) would call for a different set of public prevention strategies than would a higher rate of old-age PSI due to societal characteristics such as low social trust or positive attitudes toward suicide (contextual effects).

Methodologically speaking, studies on old-age PSI so far suffered from two weaknesses: Firstly, most of the evidence stems from analyses of cross-sectional data that do not allow inferring causality. The second issue is the lack of attention for potential country-level factors. The scarcity of comparable cross-national data on PSI has hampered comparative cross-national analyses of PSI to integrate explanatory factors from both micro- and macro-levels. In fact, none of the existing studies on PSI has ever used multilevel regression modeling of nationally representative data that would indeed be necessary to assess both individual and societal determinants simultaneously.

We sought to address these shortcomings using panel data from a large European health survey (Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe [SHARE]) and Bayesian multilevel regression analysis, an approach that allowed us to disentangle individual- and country-level components of the country-level variation of PSI in a dozen European countries. With regard to the individual level, we included a number of established risk factors for PSI, conceptually ordered in a process model (Erlemeier, 2002). This included (a) predisposing factors such as sex, age, health status, and functioning and (b) vulnerability factors incorporating psychosocial resources such as perceived control over one’s life, religiosity, and social support. The latter factors were thought to determine how well older individuals cope with (c) critical life events, such as the loss of their partner, health deterioration, or loss of functioning after an injury (Figure 1). Vulnerability factors and critical events were expected to have a more immediate and thus stronger effect on developing PSI compared with the predisposing factors.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Regarding societal risk factors, we relied on factors identified by research on the cross-national variation of aggregated suicide rates that are potentially applicable also to PSI in old age, subsumed in three categories: social integration, public health care, and cultural acceptance of suicide (Figure 1). Social integration, that is, the degree to which individuals are embedded in social networks that provide a sense of belonging and meaning, has long been acknowledged as crucial for individual’s well-being and has been associated with cross-national differences in suicide (Durkheim, 1897/1983; Stack, 2000). More recently, intergenerational familial cohabitation has been considered beneficial in this regard, given the higher integration in everyday family life and the ability of younger family members to more easily provide cohabiting older adults with growing physical impairments with instrumental and emotional support on a daily basis (Shah, 2009; Yur’yev et al., 2010). Furthermore, a high level of social trust among individuals within a given society has been associated with higher quality of life in general and fewer suicides more specifically (Helliwell, 2007; Kelly, Davoren, Mhaoláin, Breen, & Casey, 2009; Netuveli, Wiggins, Hildon, Montgomery, & Blane, 2006). This could be particularly relevant in older age due to an increased reliance on and required support from others in everyday activities. Religiosity has also been portrayed as a protective factor for the support within religious networks, the provision of meaning and comfort, but also for the moral objections against and stigmatization of suicide. According to the moral community thesis regarding suicide, exposure to a religious social environment should reduce suicide-related behaviors (Clarke, Bannon, & Denihan, 2003; Neeleman & Lewis, 1999; Stack & Kposowa, 2011). Finally, negative attitudes toward older adults, that is, a low valuation of older adults’ qualities and role in society have been associated with lowered self-esteem, internalization of negative age stereotypes, a weakened will to live, and suicide mortality among older adults (Levy & Dror, 2000; Rodin & Langer, 1980; Yur’yev et al., 2010). Due to the substantial impact of health status on old-age PSI at the individual level, national differences in both the quantity and the quality of physical and mental health care provision could also relate to cross-national differences in PSI. On a global scale, Shah, Bhat, Mckenzie, and Koen (2008), however, found a positive correlation between public health care spending and old-age suicide rates. As a more specific indicator, higher national prescription rates for and utilization of antidepressants have also been associated with lowered suicide rates in Europe (Gusmao et al., 2013). Finally, it has been suggested that positive attitudes toward suicide may constitute a “culture of suicide” that, particularly in the face of old-age adversaries, may encourage suicide-related behavior (Cutright & Fernquist, 2000a, 2000b; Stack & Kposowa, 2008). This could also extend to attitudes toward end-of-life decisions such as assisted suicide and euthanasia (Verbakel & Jaspers, 2010).

Societal factors can exert a direct influence on individual-level PSI, as when all older individuals in the community benefit from religious community structures irrespective of their own religious commitment, or benefit from easier access to antidepressants. Societal factors can also work with or through individual-level characteristics, as when, for example, higher levels of social trust in a society make finding companionship outside the family easier after bereavement or when negative age stereotypes exacerbate the negative impact of a loss of functioning on the subjective well-being of older adults.

In a nutshell, the specific objectives of this study were (a) to assess cross-national variation in PSI among those older adults with the highest suicide risk, that is, aged 75 years or older, in a dozen European countries; (b) to test the impact of a comprehensive number of individual-level determinants of PSI; (3) to assess the degree to which cross-national variation in PSI can be attributed to compositional differences, that is, to varying national prevalences of individual-level risk factors, such as poor health; and finally, (d) which of the above-mentioned societal characteristics, if any, affect old-age PSI as contextual factors.

Method

Data

The SHARE provides representative, cross-nationally comparable panel data (computer-assisted personal interviews and pen-and-paper drop-off questionnaires) about more than 58,000 individuals in residential households, aged 50 years and older, in 16 European countries (Börsch-Supan et al., 2013). The target population for the fourth and the fifth wave of SHARE was those born in 1960 and 1962 or earlier, and fieldwork mostly took place in 2011 and 2013, respectively. The panel response rate for participants of Wave 4 ranged between 70.9% in France and 89.0% in Denmark in the subsequent Wave 5. The analysis was limited to countries and individuals (75+) who participated in both waves. Furthermore, Estonia was excluded from the analysis since the drop-off questionnaire including the central variable “loneliness” was not used in this country. This resulted in a total sample of 6,791 respondents in 12 countries: Austria (AT), Belgium (BE), Switzerland (CH), Czech Republic (CZ), Germany (DE), Denmark (DK), Spain (ES), France (FR), Italy (IT), Netherlands (NL), Sweden (SE), and Slovenia (SI). Country-level data on societal risk factors for all the 12 countries were obtained from international organizations, such as Eurostat, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), World Health Organization (WHO), and also by aggregating individual-level data from two well-established cross-national social science surveys: the European Social Survey (ESS) and the European Values Study (EVS; for review, see http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/about/ [accessed January 11, 2015] and http://www.europeanvaluesstudy.eu/page/about-evs.html [accessed January 11, 2015]).

Individual-Level Measures

PSI was assessed using a dichotomous item from the EURO-D scale: “In the last month, have you felt that you would rather be dead?” The mentioning of suicidal feelings or the wish to be dead were coded as 1. This dichotomous item had been used previously in order to assess PSI (Ayalon, 2011; Fässberg et al., 2014; Saïas et al., 2012), and Desseilles et al. (2012) outlined that single suicide items from depression scales can be used as valid measures of suicidal ideation.

Predisposing factors included gender and age, next to education, measured by the International Standard Classification of Education-97 (0–2 = low, 3–4 = medium, 5–6 = high). Respondents further reported whether their households were able to make ends meet with their monthly household incomes easily or with difficulty. Health variables included subjectively reported poor health (no/yes), the number of restrictions in basic activities of daily living (ADL: 0–6) and instrumental ADL (IADL: 0–7) as well as whether or not respondents had ever been treated for depression and/or had been diagnosed to suffer from other affective or emotional disorders (no/yes).

Vulnerability factors included perceived control, religiosity, and social support. Perceived control was measured by an additive index based on 3 Likert-scaled items (Cronbach’s α = 0.70) extracted from the quality of life index CASP-12, for example, “How often do you feel what happens to you is out of your control?,” where answers included “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” and “never.” This resulted in a sum index of perceived control over one’s life ranging from 3 (low) to 12 (high). Additionally, we assessed whether perceived control remained stable, improved, or worsened between measurements. Respondents’ religiosity was measured by the frequency of prayer (daily/less often/never). Social support was measured by respondents’ partner status in Wave 4 (yes/no), the size of their personal social network (0–7), and whether respondents reported to often feel lonely (no/yes). Furthermore, we accounted for changes in the loneliness status between waves (stable/improved/worsened).

Critical events included changes in the partner status, in health, and in functioning. We assessed whether respondents had lost their partner between waves due to divorce, separation, or bereavement (no/yes). Subjective health was rated to be either stable, improved (from poor to nonpoor health), or worsened (from nonpoor health to poor health) over the 2-year follow-up period. Similarly, ADL and IADL limitations could either remain stable, decrease, or increase between measurements.

Country-Level Measures

Social integration included intergenerational familial cohabitation involving older adults and was measured by the percentage of households with three or more generations of cohabiting family members (Eurostat). Furthermore, the level of social trust in other members of society was measured by the national average of the following item from the 2010 EVS: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people,” with answer categories ranging from 0 (can’t be too careful) to 10 (most people can be trusted). The religious population (in %) within a country was estimated based on the ESS from 2012 (2008 for Austria) and measured as the proportion of respondents who attended religious ceremonies or prayed at least monthly and who rated themselves as religious (6–10 on a scale 0–10; Voas, 2009). Finally, the perception of older adults as a burden in a given country was measured by the mean response value of the following item from the 2008 ESS: “Please tell me whether or not you think people over 70 are a burden on [country]’s health service these days?,” with answer categories ranging from 0 (no burden) to 10 (a great burden). This variable was not available for Italy.

Public health care provision included the national health care expenditure in percentage of the GDP for 2011 (OECD database), and the national antidepressant consumption was measured as the daily dosage of antidepressants per 1,000 individuals per day defined by WHO, and averaged across the years 2005–2009, as provided in Gusmao et al. (2013).

Cultural acceptance of suicide referred to a high social acceptance of both suicide and euthanasia as legitimate end-of-life decisions and was measured by the combined national mean values of the following 2 items taken from the 2008 EVS: “Please tell me whether you think [suicide, euthanasia] can always be justified (10), never be justified (1), or something in between.”

Statistical analyses

All data analyses were performed using R (version 3.2.2). We used multivariate lagged logistic regression models with PSI (Wave 5) as dependent variable, controlling for baseline PSI (Wave 4), that is, modeling stability of PSI over time, in order to predict the changes in PSI. Several variables, particularly from the drop-off questionnaires, contained missing data—death wish (Wave 5: 4.3%), frequency of prayer (12.1%), and loneliness (17.2 %)—therefore, multiple imputation via a bootstrapping-based expectation–maximization algorithm (Amelia version 1.7.3) was applied, resulting in 10 complete data sets. Due to the small number of countries for which individual-level data were available for both waves (n = 12), Bayesian multilevel logistic regression analysis (MCMCglmm version 2.22) was applied instead of maximum likelihood (ML) procedures, in order to receive unbiased estimates of both variance components of PSI and country-level predictors (Stegmueller, 2013). A noninformative, flat prior was used, and the draws from the posterior distribution of each imputed data set were mixed to summarize the overall posterior distribution (Zhou & Reiter, 2010). Inspection of trace and density plots and diagnostics indicated convergence.

We fitted the following model types: random intercept-only (M0) to evaluate country-level variation of PSI, random intercept (M1) to assess the impact of individual-level factors and associated compositional effects, and intercept as outcome (M2a-M2g) with one country-level indicator included at a time to assess contextual effects. Compositional effects due to nationally varying prevalences of individual-level factors were assessed by the reduction of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), that is, the proportion of variance of PSI located at the country level, before and after adjustment for individual-level predictors.

Results

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics: 57.6% of the sample were women, the mean age was 80.5 years. Over 60% of the respondents had completed primary education, just over half of them had a partner, and about 5% lost their partner between measurements. In all, 14.4% of the respondents indicated to be in poor health, and worsened health and functioning were more often reported than improvements. The overall prevalence of PSI was 11.2% (in Wave 4) and 12.2% (in Wave 5). Of the total, 81.9% of the sample did not report PSI in either of the waves, whereas 4.9% reported PSI in both waves, 6.1% reported PSI only in Wave 4, and 7.2% only in Wave 5. This indicates some dynamics in PSI status across the 2 years of measurement. Ninety-six respondents, or 8.4% of those reporting PSI in Wave 4, died between waves, which is slightly more than among those not reporting PSI (6.6%, χ2 = 5.03, df = 1, p = .021). The cause of death was unknown, but the respondents with PSI who died were on average 2 years older and more likely to report poorer health (χ2 = 4.22, df = 1, p = .04), whereby sex, education, partner status, loneliness, or mental health did not differ from those with PSI remaining in the sample.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variables | n | % or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Death wish (Wave 5) | ||

| No | 5,707 | 87.8% |

| Yes | 790 | 12.2% |

| Death wish (Wave 4) | ||

| No | 5,900 | 88.8% |

| Yes | 742 | 11.2% |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 3,913 | 57.6% |

| Male | 2,878 | 42.4% |

| Age in years (75–102) | 6,791 | 80.50 (4.49) |

| Education | ||

| Low | 4,007 | 61.4% |

| Mid | 1,603 | 25.6% |

| High | 919 | 14.1% |

| Ends meet | ||

| Easily | 4,477 | 67.2% |

| With difficulty | 2,186 | 32.8% |

| Poor health | ||

| No | 5,804 | 85.6% |

| Yes | 974 | 14.4% |

| Change in poor health (t 0–t 1) | ||

| Stable | 5,700 | 84.3% |

| Improved | 395 | 5.8% |

| Worsened | 663 | 9.8% |

| Number of ADLs (0–6) | 6,780 | 0.45 (1.13) |

| Change in ADLs (t 0–t 1) | ||

| Stable | 4,878 | 72.1% |

| Improved | 629 | 9.3% |

| Worsened | 1,253 | 18.6% |

| Number of IADLS (0–7) | 6,780 | 0.78 (1.53) |

| Change in IADLs (t 0–t 1) | ||

| Stable | 3,994 | 59.1% |

| Improved | 864 | 12.8% |

| Worsened | 1,898 | 28.1% |

| Depression/affective disorder | ||

| No | 5,929 | 87.3% |

| Yes | 862 | 12.7% |

| Perceived control (3–12) | 6,540 | 8.01 (2.46) |

| Change in perceived control (t 0–t 1) | ||

| Stable | 3,074 | 49.8% |

| Improved | 1,466 | 23.7% |

| Worsened | 1,639 | 26.5% |

| Frequency of prayer | ||

| Daily | 2,381 | 39.9% |

| Less often | 1,668 | 28.0% |

| Never | 1,912 | 32.1% |

| Partner status | ||

| With partner | 3,686 | 54.3% |

| Without partner | 3,105 | 45.7% |

| Lost partner (t 0–t 1) | ||

| No | 6,465 | 95.2% |

| Yes | 326 | 4.8 |

| Size of social network (0–7) | 6,791 | 2.32 (1.55) |

| Often lonely | ||

| No | 5,229 | 92.9% |

| Yes | 397 | 7.1% |

| Change in often lonely (t 0–t 1) | ||

| Stable | 4,850 | 89.2% |

| Improved | 202 | 3.7% |

| Worsened | 388 | 7.1% |

Notes. SHARE, Waves 4 (version 1.1.1) and 5 (version 1.0), sample size = 6,791, unweighted data. ADLs = activities of daily living, IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living, SD = standard deviation.

On the country level (Table 2), social trust was highest in Scandinavian countries. Health care spending was highest in Northern and Central Europe, and the utilization of antidepressants was most widespread in Denmark and Sweden. Intergenerational cohabitation was most widespread in both Southern and Eastern Europe, whereas religiosity was highest in Southern European countries but least prevalent in the Czech Republic. Social acceptance of suicide and euthanasia was highest in countries such as France or the Netherlands. The tendency for elders to be considered as a burden for the health system was strongest in the Czech Republic and weakest in Spain.

Table 2.

Country-Level Characteristics

| Variable | Country | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | BE | CH | CZ | DE | DK | ES | FR | IT | NL | SI | SE | |

| Sample size (SHARE) | 694 | 830 | 526 | 722 | 210 | 351 | 806 | 916 | 532 | 414 | 418 | 372 |

| PSI (Wave 5) in % (SHARE) | 8.7 | 15.5 | 7.1 | 14.8 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 12.1 | 21.1 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 12.3 | 8.0 |

| Intergenerational cohabitation in % (Eurostat) | 13.2 | 7.4 | 8.7 | 15.3 | 7.2 | 1.7 | 20.5 | 5.8 | 17.1 | 5.6 | 14.2 | 2.9 |

| Social trust (0–10) (EVS) | 5.4 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 6.4 |

| Health expenditure in % of GDP (OECD) | 10.8 | 10.5 | 11.0 | 7.5 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 11.6 | 9.2 | 11.9 | 8.9 | 9.5 |

| Utilization of antidepressants (WHO) | 49.8 | 67.7 | 46.6 | 30.9 | 33.3 | 68.5 | 40.1 | 49.5 | 33.3 | 39.4 | 38.6 | 70.1 |

| Cultural acceptance suicide and euthanasia (0–10) (EVS) | 3.7 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 5.4 |

| Religious population in % (ESS) | 32.1 | 27.4 | 36.5 | 9.6 | 32.1 | 16.4 | 31.2 | 25.7 | 51.5 | 30.7 | 23.7 | 15.8 |

| Burdensomeness (0–10) (ESS) | 6.4 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 7.4 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 6.1 | - | 5.3 | 4.9 | 5.3 |

Notes. SHARE = Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe; PSI = passive suicide ideation; ESS = European Social Survey; EVS = European Values Study; GDP = gross domestic product; WHO = World Health Organization; OECD = Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; AT = Austria; BE = Belgium; CH = Switzerland; CZ = Czech Republic; DE = Germany; DK = Denmark; ES = Spain; FR = France; IT = Italy; NL = Netherlands; SI = Slovenia; SE = Sweden.

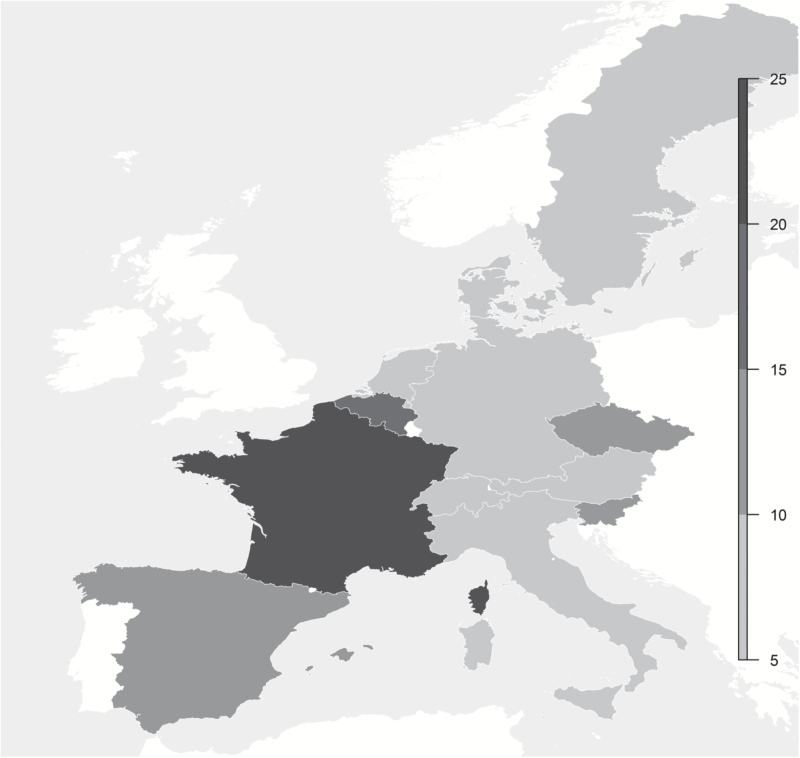

The prevalence of PSI in Europe (Table 2) varied considerably between countries such as France (21.1%) or Belgium (15.5%) on the one hand, and Italy (6.9%) or the Netherlands (6.9%) on the other hand (χ2 = 133, df = 11, p < .001) without, however, following obvious North–South or East–West gradients (Figure 2). The prevalence of PSI per country in percent correlated with social trust (r = −0.49), attitudes toward suicide/euthanasia (r = 0.38), religiosity (r = −0.38), and older adults perceived as a burden (r = 0.21) but not with intergenerational cohabitation (r = 0.04), health care expenditure (r = −0.08), or utilization of antidepressants (r = 0.07). Furthermore, country-level PSI correlated with the suicide rate (2010) among the 75+ (r = 0.44), with the latter also being particularly high in Belgium and France.

Figure 2.

Passive suicide ideation in percentage of the older population (75+). SHARE, fifth (version 1.0) wave, longitudinal sample, unweighted data, n = 6,497.

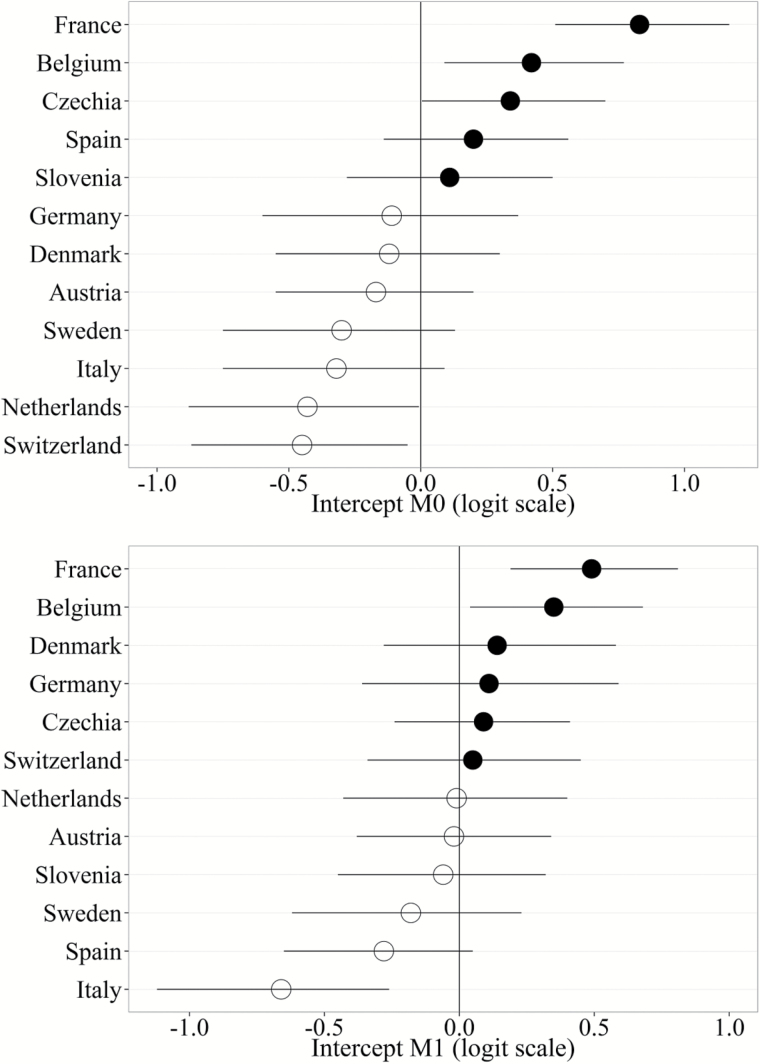

The median variance estimate for country σ2 = 0.19 (confidence interval [CI] = 0.07–0.54) and ICC = 0.041 in M0 indicated nonnegligible cross-national variation of PSI. The inclusion of individual-level predictors decreased country-level variation (σ2= 0.120, CI = 0.04–0.38, ICC = 0.027). Figure 3 shows the country-level residuals for the intercept for M0 and M1. Table 3 shows the results of the fixed determinants at the individual level (M1). PSI in Wave 4 was highly predictive of PSI 2 years later, indicating that although dynamic, PSI does not change volatilely. The odds of developing respectively of overcoming PSI increased respectively decreased with age (3% per year). Chances of developing PSI were higher for women (+31%), for older adults with poor health (+106%) and for those suffering from depressive or other affective disorders (+85%). Perceived control in Wave 4 predicted the development of PSI, and changes in perceived control were associated with developing (+54%) respectively overcoming PSI (+33%). Similarly, older adults who never prayed were at higher risk of developing PSI (+37%) compared with those who prayed on a daily basis. Furthermore, those with smaller personal social networks, and particularly those who reported to often feel lonely (+85%) or whose frequency of loneliness increased between waves (+54%), were at increased risk of developing PSI and had lowered chances of overcoming PSI. Regarding critical life events, the loss of a partner (+77%) or a recent deterioration in health (+148%) substantially increased the odds of developing PSI. Refitting M1 with ML showed highly similar results and a marginal R 2 (Nakagawa, Schielzeth, & O’Hara, 2013) of 0.258.

Figure 3.

Intercept residuals by country (M0 & M1). Posterior means and 95 % credible intervals.

Table 3.

Multilevel Logistic Regression Analysis (MCMC) of PSI (Individual-Level Coefficients)

| Variable | OR | CI (95 %) | pMCMC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | |||

| Death wish (Wave 4): (ref.: No) | |||

| Yes | 6.14 | 4.87–7.75 | <0.001 |

| Sex (ref.: Male) | |||

| Female | 1.31 | 1.04–1.66 | 0.020 |

| Age in years (75–102) | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 0.075 |

| Education (ref.: Low) | |||

| Mid | 0.76 | 0.59–0.99 | 0.038 |

| High | 0.84 | 0.61–1.16 | 0.294 |

| Ends meet (ref.: Easily) | |||

| With difficulty | 1.02 | 0.82–1.28 | 0.840 |

| Poor health (ref.: No) | |||

| Yes | 2.06 | 1.46–2.90 | <0.001 |

| Number of ADLs (0–6) | 1.07 | 0.95–1.20 | 0.284 |

| Number of IADLS (0–7) | 1.00 | 0.91–1.10 | 0.976 |

| Depression/affective disorder (ref.: No) | |||

| Yes | 1.85 | 1.45–2.36 | <0.001 |

| Vulnerability factors | |||

| Perceived control (3–12) | 0.86 | 0.81–0.91 | <0.001 |

| Change in perceived control (t 0−t 1) (ref.: Stable) | |||

| Improved | 0.75 | 0.57–0.99 | 0.036 |

| Worsened | 1.54 | 1.20–1.98 | <0.001 |

| Frequency of prayer (ref.: Daily) | |||

| Less often | 1.13 | 0.88–1.45 | 0.323 |

| Never | 1.37 | 1.06–1.75 | 0.016 |

| Partner status (ref.: With partner) | |||

| Without partner | 1.14 | 0.91–1.42 | 0.249 |

| Size of social network (0–7) | 0.93 | 0.87–1.00 | 0.036 |

| Often lonely (ref.: No) | |||

| Yes | 1.85 | 1.32–2.58 | <0.001 |

| Change in loneliness (t 0−t 1)(ref.: Stable) | |||

| Improved | 0.77 | 0.51–1.17 | 0.220 |

| Worsened | 2.14 | 1.58–2.90 | <0.001 |

| Critical event | |||

| Lost partner (t 0−t 1) (ref.: No) | |||

| Yes | 1.77 | 1.16–2.68 | <0.001 |

| Change in poor health (t 0−t 1) (ref.: Stable) | |||

| Improved | 0.54 | 0.35–0.84 | 0.006 |

| Worsened | 2.48 | 1.87–3.31 | <0.001 |

| Change in ADLs (t 0−t 1) (ref.: Stable) | |||

| Improved | 1.26 | 0.87–1.83 | 0.221 |

| Worsened | 1.22 | 0.94–1.58 | 0.138 |

| Change in IADLs (t 0−t 1) (ref.: Stable) | |||

| Improved | 0.72 | 0.51–1.02 | 0.066 |

| Worsened | 1.28 | 1.01–1.63 | 0.040 |

| Intercept | 0.02 | 0.02–0.03 | <0.001 |

Notes. SHARE, Waves 4 (1.1.1) and 5 (1.0), unweighted data, N = 6,791. MCMC: 55,000 iterations, burn-in = 5,000, thinning 20 = eff. sample size = ~2,500 per chain. OR = adjusted odds ratio of posterior mean, CI = 95 % credible intervals, pMCMC = Bayesian p value. ADLs = activities of daily living; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living.

Table 4 summarizes the impact of societal context factors. The inclusion of country-level indicators reduced ICC further in M2a, M2c, M2e, and M2g compared with M1. Regarding social integration, a 10% increase in intergenerational cohabitation reduced the odds of developing PSI by 45% (pMCMC = 0.054). Country-level religiosity (odds ratio = 0.84, pMCMC = 0.092) showed a smaller and less consistent effect, whereas social trust, older adults as perceived national burden, as well as the two indicators of public health care provision, were not statistically significantly associated with PSI. Finally, a higher national acceptance of suicide/euthanasia by 1 point (of 10) increased the odds of developing PSI by 44% (pMCMC = 0.030).

Table 4.

Multilevel Logistic Regression Analysis (MCMC) of PSI (Country-Level Coefficients)

| Model | OR | CI (95 %) | pMCMC | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0: Empty model | — | — | — | 0.041 |

| M1: Individual-level predictors only | — | — | — | 0.027 |

| M2a: Intergenerational cohabitation/10 | 0.69 | 0.48–0.99 | 0.054 | 0.017 |

| M2b: Social trust | 1.07 | 0.75–1.55 | 0.683 | 0.030 |

| M2c: Religious population/10 | 0.84 | 0.68–1.03 | 0.092 | 0.021 |

| M2d: Burdensome eldersa | 1.12 | 0.90–1.40 | 0.266 | 0.013 |

| M2e: Health care expenditure | 1.14 | 0.95–1.35 | 0.141 | 0.022 |

| M2f: Utilization antidepressants/10 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.376 | 0.026 |

| M2g: Approval suicide/euthanasia | 1.44 | 1.08–1.91 | 0.030 | 0.021 |

Notes. SHARE, waves 4 (1.1.1) and 5 (1.0), unweighted data, n = 6,791. MCMC: 55,000 iterations, burn-in = 5,000, thinning 20 = eff. sample size ~ 2,500 per chain. OR = adjusted odds ratio of posterior mean, CI = 95 % credible intervals, pMCMC = Bayesian p-value, ICC = intraclass-correlation coefficient. M1 includes all individual-level variables, M2a-M2g include all individual-level variables and one country-level variable each.

aData not available for Italy, model M2g refers to 11 remaining countries. ICC for the reduced reference model M1noIT = 0.013.

Discussion

The suicide risk in Europe is highest among people aged 75 years or older, but it has only received limited attention from public health planners. Passive death wishes are markers of suicidal behavior and constitute an early target for suicide prevention in older adults. As with suicide rates, the prevalence of PSI among the population 75+ varies substantially across European countries, but unlike suicide rates, the cross-national variation of PSI has not been addressed by research so far. With this paper, we seek to contribute to the understanding of (a) individual-level determinants, but particularly of (b) societal-level determinants of PSI in the older high suicide-risk population (75+) in Europe.

On average, we found 12% of the sampled elders to report passive death wishes that is expectedly higher than reported figures from other studies based on the population 65+ (Ayalon, 2011; Fässberg et al., 2014). PSI showed some dynamism within 2 years that highlights the need for careful longitudinal analyses and confirms the results of a previous longitudinal analysis using SHARE (Ayalon, 2011). Central to the study, we found substantial and similar cross-national variation in the prevalence of PSI as reported previously (Saïas et al. 2012). Using a multilevel Bayesian regression approach, we showed that 4% of the total variance of PSI was located at the country level, a percentage that was further reduced to 2.7% when compositional differences were accounted for. This means that more than a third of the cross-national differences in aggregated PSI, which motivated this study, was due to a higher prevalence of individual-level risk factors in some countries, for example, to a higher proportion of older adults feeling lonely or suffering from poor physical or mental health.

Regarding the individual-level risk factors, our study confirmed a number of findings established by previous research. Regarding predisposing characteristics, we found older (Corna et al., 2010; Fässberg et al., 2014) as well as female respondents (Ayalon 2011; Saïas et al., 2012) but also respondents in poor physical health or with a history of depression or other affective disorders to be more likely to develop PSI (Almeida et al., 2012; Corna et al., 2010; Fässberg et al., 2014). Unlike cross-sectional studies that linked functional limitations in ADL and IADL with PSI (Dennis et al., 2009; Fässberg et al., 2014), but in line with results of the longitudinal study from Ayalon (2011), we only found limited evidence in this regard independent of subjective health, which might be attributable to adaptation processes in the face of growing functional limitations (Baltes & Baltes, 1990). Regarding vulnerability factors, and in line with the results from Rurup et al. (2011b), we found lower levels of perceived control over one’s life, the size of the personal social network, and frequent loneliness to increase the odds of developing respectively not overcoming PSI which is again compatible with previous findings (Ayalon & Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011; Fässberg et al., 2014; Rurup et al., 2011a). As expected and based on the outlined theoretical model, vulnerability factors and critical life events, such as the loss of the partner or health deterioration, were among the most salient predictors of developing PSI.

After controlling for a comprehensive number of individual-level risk factors, a small (2.7%), but statistically significant, share of variance of PSI remained that is potentially attributable to country-level contextual factors. We subsequently found some evidence for country-level contextual effects on PSI, but it was difficult to evaluate these findings, as there is virtually no cross-national literature to refer to in this respect. A higher cultural acceptance of suicide and euthanasia was linked to a higher incidence rate of PSI. The increase of one unit in this variable, that is, the difference between Italy and the Czech Republic, resulted in an increased chance of developing PSI by 44%. Substantively, this finding—which is in line with the results from ecological studies by Cutright and Fernquist (2000a, 2000b)—can be interpreted as a contextual effect of national differences in attitude toward the legitimacy of individual choices in end-of-life decisions when everyday life is perceived as cumbersome in old age and no longer worth living and hence more likely leads to the wish to die. On the other hand, normative differences could also affect the inclination to report a death wish that may exist in similar orders of magnitude among elders in other countries but where open social communication about this issue is more frowned upon.

Smaller or slightly less consistent effects were found regarding social integration. The positive contextual effect of religiosity, regardless of the individual level of prayer frequency, could be due to a higher chance of concrete beneficial interaction with religious members of society regarding PSI (“moral community effect”) but, more abstractly speaking, could also reflect social norms regarding death and suicide as codetermined by religious institutions (Cohen et al., 2006). This includes the possibility of survey responses being biased by country-level religiosity. Furthermore, the country differences in PSI remaining after controlling for individual-level risk factors (Figure 3), particularly the vicinity of countries like Italy, Spain, and Sweden, did not imply a divergent confessional impact of Catholicism or Protestantism on PSI (cf. Durkheim, 1897/1983; Stack, 2000). In line with the results from ecological studies (Shah, 2009; Yur’yev et al., 2010), we found older adults in countries with higher levels of intergenerational cohabitation, irrespective of individual-level social support, less likely to develop PSI. This effect could be due to a higher level of familial integration of elders in such countries in the form of support with household tasks, grandparenting, or financial assistance or to a higher level of socially expected emotional and instrumental daily support for older family members with health deterioration. Regarding social trust and attitudes toward older adults, we found bivariate associations with aggregated PSI—in line with some ecological studies (Kelly et al., 2009; Yur’yev et al., 2010)—but these associations did not hold after individual-level determinants were controlled for.

Against the backdrop of demographic aging in European societies, it is paramount to understand why a considerable share of older members of society wants to die and to address this growing public health issue. Therefore, it is important to identify the sources of such cross-national differences in terms of death wishes among older adults, in order to tailor national suicide prevention programs to their needs. Cross-national research on PSI can help identify why some countries provide more favorable living environments for the oldest members of society, particularly in case of health deterioration and social isolation and what may be learned from these countries. It may also help to focus on preventive efforts at the European Union level, especially in countries for whose older population we identified a higher risk of developing PSI, such as France and Belgium. On the one hand, our results highlight the role of individual-level risk factors—and their different prevalences (compositional effects)—which should be addressed more comprehensively by conventional suicide prevention strategies, particularly in high-risk countries. On the other hand, there is the role of contextual, country-level effects on PSI, that is, social integration in the form of intergenerational cohabitation and religiosity but also cultural acceptance of suicide, that is, the normative adequacy of not wanting to live on in the face of restrictions associated with old age. Particularly the latter attitudes are potentially modifiable through information campaigns that promote active aging, and highlight the potential contributions of older people to society and that life is worth living despite any age-based restrictions.

Strengths and Limitations

Among the strengths of our study is the fact that it addresses the lacunae of cross-national research on PSI by utilizing recent, cross-nationally comparable, longitudinal panel data from 12 European countries, a large sample of older adults aged 75 years and older (n = 6,791) and an appropriate method of statistical analysis. A number of individual-level and societal-level indicators were tested within a theoretical framework in order to decompose and explain cross-national variation in PSI. This study also has several limitations. Firstly, PSI was measured by a single item from a depression scale, whereas a more fine-grained measure and a clearer distinction between passive and active suicide ideation would be desirable. Also, panel data from SHARE is likely subject to a positive health selection bias that could result in an underestimation of PSI. It is important to note that PSI represents only a first step in a row of suicide-related behaviors and must, therefore, not be equated with active suicide ideation, suicide attempts, or actual suicide and their respective cross-national variation. Finally, country-level variables were added one at a time due the small number of countries participating in SHARE which is why statistical control of country-level indicators was not possible, although country-level indicators correlated with each other.

Conclusion

This study utilized longitudinal, cross-national survey data (SHARE) and multilevel regression modeling in order to assess both individual and societal risk factors regarding death wishes among the older population (75+) and to explain their substantial cross-national variation. Overall, PSI in old age is mostly determined by individual-level factors and their varying prevalence across countries. Nonetheless, cultural acceptance of suicide, religiosity, and intergenerational cohabitation were found to be predictive of national PSI rates among older adults.

Funding

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 4 and 5 (10.6103/SHARE.w4.111, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.100), see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details. The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: N°227822, SHARE M4: N°261982). Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Acknowledgments

E. S. co-planned the study, performed all statistical analysis, and wrote the paper; B. F. contributed to the conceptual model and the methodological approach; H. M. and E. R. critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed to revising the paper; W. F. planned the study and supervised the analyses. All authors have read and approved the final version. This work was supported by no specific institution but only by the Medical University of Graz and the University of Salzburg. The views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not represent their employers.

References

- Almeida O. P. Draper B. Snowdon J. Lautenschlager N. T. Pirkis J. Byrne G., … Pfaff J. J (2012). Factors associated with suicidal thoughts in a large community study of older adults. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 201, 466–472. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.110130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L. (2011). The prevalence and predictors of passive death wishes in Europe: A 2-year follow-up of the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 923–929. doi:10.1002/gps.2626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L., & Shiovitz-Ezra S (2011). The relationship between loneliness and passive death wishes in the second half of life. International Psychogeriatrics/IPA, 23, 1677–1685. doi:10.1017/S1041610211001384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca-Garcia E. Perez-Rodriguez M. M. Oquendo M. A. Keyes K. M. Hasin D. S. Grant B. F., & Blanco C (2011). Estimating risk for suicide attempt: Are we asking the right questions? Passive suicidal ideation as a marker for suicidal behavior. Journal of Affective Disorders, 134, 327–332. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes P. B., & Baltes M. M (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In Baltes P.B., Baltes M. M. (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 1–34). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan A. Brandt M. Hunkler C. Kneip T. Korbmacher J. Malter F., … Zuber S (2013). Data resource profile: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology, 42, 992–1001. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. K. Beck A. T. Steer R. A., & Grisham J. R (2000). Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 371–377. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.68.3.371 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke C. S. Bannon F. J., & Denihan A (2003). Suicide and religiosity–Masaryk’s theory revisited. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38, 502–506. doi:10.1007/s00127-003-0668-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Marcoux I. Bilsen J. Deboosere P. van der Wal G., & Deliens L (2006). European public acceptance of euthanasia: Socio-demographic and cultural factors associated with the acceptance of euthanasia in 33 European countries. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 743–756. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corna L. M. Cairney J., & Streiner D. L (2010). Suicide ideation in older adults: Relationship to mental health problems and service use. The Gerontologist, 50, 785–797. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukrowicz K. C. Cheavens J. S. Van Orden K. A. Ragain R. M., & Cook R. L (2011). Perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 26, 331–338. doi:10.1037/a0021836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutright P., & Fernquist R (2000. a). Social integration, culture and period: Their impact on female age-specific suicide rates in 20 developed countries, 1955–1989. Sociological Focus, 33, 299–319. doi:10.1080/00380237.2000.10571172 [Google Scholar]

- Cutright P., & Fernquist R (2000. b). Effects of societal integration, period, region and culture of suicide on male age-specific suicide rates: 20 developed countries, 1955–1989. Social Science Research, 29, 148–172. doi:10.1006/ssre.1999.0658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D. Krysinska K. Bertolote J. M. Fleischmann A., & Wasserman D (2009). Suicidal behaviours on all the continents among the elderly. In: Wasserman D., Wasserman C. (Eds.), Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention (pp. 693–702). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M. Baillon S. Brugha T. Lindesay J. Stewart R., & Meltzer H (2009). The influence of limitation in activity of daily living and physical health on suicidal ideation: Results from a population survey of Great Britain. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44, 608–613. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0474-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desseilles M. Perroud N. Guillaume S. Jaussent I. Genty C. Malafosse A., & Courtet P (2012). Is it valid to measure suicidal ideation by depression rating scales? Journal of Affective Disorders, 136, 398–404. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez R. (2002). A glossary for multilevel analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56, 588–594. doi:11.1136/jech.56.8.588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. (1897/1983). Der Selbstmord [Suicide]. Berlin, Germany: Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Erlemeier N. (2002). Suizidalität und Suizidprävention im Alter [Suicidality and suicide prevention in old age]. Stuttgart, Germany: Kohlhammer. [Google Scholar]

- Fässberg M. Östling S. Braam A. W. Bäckman K. Copeland J. R. M., & Fichter M (2014). Functional disability and death wishes in older Europeans: Results from the EURODEP concerted action. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 1475–1482. doi:10.1007/s00127-014-0840-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsell Y. (2000). Death wishes in the very elderly: Data from a 3-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia, 102, 135–138. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102002135.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusmao R. Quintao S. McDaid D. Arensman E. Van Audenhove C. Coffey C., … Hegerl U (2013). Antidepressant utilization and suicide in Europe: An ecological multi-national study. PLoS ONE, 8, 1–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell J. F. (2007). Well-being and social capital: Does suicide pose a puzzle? Social Indicators Research, 81, 455–496. doi:10.1007/s11205-006-0022-y [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B. D. Davoren M. Mhaoláin A. N. Breen E. G., & Casey P (2009). Social capital and suicide in 11 European countries: An ecological analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44, 971–977. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0018-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B., & Dror I (2000). To be or not to be: The effect of aging stereotypes on the will to live. Omega–Journal of death and dying, 40, 409–420. doi:10.2190/y2ge-bvyq-nf0e-83vr [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S. Schielzeth H., & O’Hara R (2013). A general and simple method for obtaining R 2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4, 133–142. doi:10.1111/j2041-210x.2012.00261.x [Google Scholar]

- Neeleman J., & Lewis G (1999). Suicide, religion and socioeconomic conditions. An ecological study in 26 countries, 1990. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 53, 204–210. doi:10.1136/jech.53.4.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netuveli G. Wiggins R. D. Hildon Z. Montgomery S. M., & Blane D (2006). Quality of life at older ages: evidence from the English longitudinal study of aging (wave 1). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 357–363. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.040071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raue P. J. Morales K. H. Post E. P. Bogner H. R. Have T. T., & Bruce M. L (2010). The wish to die and 5-year mortality in elderly primary care patients. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18, 341–350. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c37cfe [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J., & Langer E (1980). Aging labels: The decline of control and the fall of self-esteem. Journal of Social Issues, 36, 12–29. doi:10.1111/j.1540–4560.1980.tb02019.x [Google Scholar]

- Rurup M. L. Deeg D. J. H. Poppelaars J. L. Kerkhof A. J. F. M., & Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D (2011. a). Wishes to die in older people. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 32, 194–203. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rurup M. L. Pasman H. R. Goedhart J. Deeg D. J. H. Kerkhof A. J. F. M., & Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D (2011. b). Understanding why older people develop a wish to die. A qualitative interview study. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 32, 204–216. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saïas T. Beck F. Bodard J. Guignard R. Du Roscoät E., & Bayer A (2012). Social participation, social environment, and death ideations in later life. PLoS ONE, 7, 1–8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scocco P., & De Leo D (2002). One-year prevalence of death thoughts, suicide ideation and behaviours in an elderly population. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 842–846. doi:10.1002/gps.691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scocco P. de Girolamo G. Vilagut G., & Alonso J (2008). Prevalence of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts and related risk factors in Italy: results from the European Study on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders–World Mental Health study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49, 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. (2009). The relationship between elderly suicide rates, household size and family structure: A cross-national study. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 13, 259–264. doi:10.3109/13651500902887656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. Bhat R. Mckenzie S., & Koen C (2007). Elderly suicide rates: Cross-national comparisons and association with sex and elderly age-bands. Medicine, Science, and the Law, 47, 244–252. doi:10.1258/rsmmsl.47.3.244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. Bhat R. Mckenzie S., & Koen C (2008). A cross-national study of the relationship between elderly suicide rates and life expectancy and marker of socioeconomic status and health care. International Psychogeriatrics, 20, 347–360. doi:10.1017/S1041610207005352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman M. M. Berman A. L. Sanddal N. D. O’Carroll P. W., & Joiner T. E (2007). Rebuilding the tower of Babel: A revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: Suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 37, 264–277. doi:10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S. (2000). Suicide: A 15-year review of the sociological literature Part II: Modernization and social integration perspectives. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 30, 163–176. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.2000.tb01074.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S., & Kposowa A (2008). The association of suicide rates with individual-level suicide attitudes: A cross-national analysis. Social Science Quarterly, 89, 39–59. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2008.00520.x [Google Scholar]

- Stack S., & Kposowa A (2011). Religion and suicide acceptability: A cross-national analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50, 289–306. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2011.01568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmueller D. (2013). How many countries for multilevel modeling? A comparison of frequentist and Bayesian approaches. American Journal of Political Science, 57, 748–761. doi:10.1111/ajps.12001 [Google Scholar]

- Suokas J. Suominen K. Isometsä E. Ostamo A., & Lönnqvist J (2001). Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide—Findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 104, 117–121. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00243.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szanto K. Reynolds C. F. Frank E. Stack J. Fasiczka A. L. Miller M., … Kupfer D (1996). Suicide in elderly depressed patients: Is active vs. passive suicidal ideation a clinically valid distinction? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 4, 197–207. doi:10.1097/00019442-199622430-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden K. A. Simning A. Conwell Y. Skoog I., & Waern M (2013). Characteristics and comorbid symptoms of older adults reporting death ideation. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21, 803–810. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbakel E., & Jaspers E (2010). A comparative study on permissiveness toward euthanasia. Religiosity, slippery slope, autonomy, and death with dignity. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74, 109–139. doi:10.1093/poq/nfp074 [Google Scholar]

- Voas D. (2009). The rise and fall of fuzzy fidelity in Europe. European Sociological Review, 25, 155–168. doi:10.109/esr/jcn044 [Google Scholar]

- Yur’yev A. Leppik L. Tooding L. M. Sisask M. Värnik P. Wu J., & Värnik A (2010). Social inclusion affects elderly suicide mortality. International Psychogeriatrics/IPA, 22, 1337–1343. doi:10.1017/S1041610210001614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., & Reiter J (2010). A note on Bayesian inference after multiple imputation. The American Statistican, 64, 159–163. doi:10.1198/tast.2010.09109 [Google Scholar]