Abstract

Discrimination is related to depression and poor self-esteem among Black men. Poorer self-esteem is also associated with depression. However, there is limited research identifying how self-esteem may mediate the associations between discrimination and depressive symptoms for disparate ethnic groups of Black men. The purpose of this study was to examine ethnic groups as a moderator of the mediating effects of self-esteem on the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms among a nationally representative sample of African American (n=1,201) and Afro-Caribbean American men (n=545) in the National Survey of American Life. Due to cultural socialization differences, we hypothesized that self-esteem would mediate the associations between discrimination and depressive symptoms only for African American men, but not Afro-Caribbean American men. Moderated-mediation regression analyses indicated that the conditional indirect effects of discrimination on depressive symptoms through self-esteem were significant for African American men, but not for Afro-Caribbean men. Our results highlight important ethnic differences among Black men.

Keywords: discrimination, depression, self-esteem, Black Americans, men

INTRODUCTION

Depression is currently the leading cause of disability within the United States and is projected to become the second leading cause of disability worldwide within the next twenty years1. Depression has been found to have a unique and pronounced impact upon Black Americans. Although the prevalence of major depression is lower for Black Americans than non-Hispanic White Americans, it is often untreated and its consequences are more severe and disabling for Black Americans2. Research has documented that racism, such as discrimination, is associated with increased depressive symptoms and other poor health outcomes among Black Americans3–10. Yet there has been limited attention given to Black American men’s experiences of discrimination and depression8. Given the sparsity of research on Black American men’s health, we examined the effects of discrimination on depressive symptoms and focused on cultural differences among Black men living in the U.S.

There is a dearth of research examining the underlying mediating processes by which discrimination negatively contributes to poor health outcomes5–7,10. Some scholars posit that individuals’ experiences and perceptions of discrimination are associated with poor self-esteem3,11–14, and this relationship is dependent on their evaluations of the discrimination experience15,16. Consequently, lower self-esteem is associated with poor health outcomes, including depression17. A few studies have examined and found support for self-esteem as a mediator of the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms, with significant findings supporting this process more so for men than women12,18. Some studies have also suggested that self-esteem might buffer (i.e., moderate) the effects of stressful life events among Black Americans15,16. However, these studies have provided mixed findings and results have varied when discrimination was the stressor19. Due to some support for the relevance of self-esteem for men, we tested the potential mediating effects of self-esteem on the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms among Black American men.

In considering the effects of discrimination on depression of Black American men, it is necessary to recognize the heterogeneity that exists within this community. Although Black American men share similar experiences of anti-Black racism overall, ethnicity contributes to distinct differences in sociocultural socialization and practices, cultural histories, languages, and values among these men. The two largest subgroups of the U.S. Black population are African Americans, who largely trace their original ancestry in the U.S. to antebellum slavery, and Afro-Caribbean Americans, who have immigrated to the United States from various Caribbean nations20–22. These two groups demonstrate differing risks for depression, with Afro-Caribbean men demonstrating a higher risk of mood disorders2. Further, the prevalence rates of mental health disorders are higher among second- and third-generation Afro-Caribbean Americans relative to first-generation and newly arriving immigrants2. These differences in mental health have been explained in terms of generational and immigrant status, wherein greater time spent in the U.S. increases exposure to discrimination and in turn poorer mental health outcomes2,23–25.

Despite their disparate cultural socialization, there is a dearth of literature examining differences in self-esteem between African-Americans and Afro-Caribbean Americans. From our review of the literature, we found only one study examining differences in self-esteem between these two groups; it found no significant differences20, but gender differences were not examined. Considering that the ways in which discrimination may relate to self-esteem is dependent on the person’s evaluation of the discrimination experience15,16, the cultural differences between African American and Afro-Caribbean American men might affect their perceptions of discrimination and, therefore, affects their self-esteem. African American and Afro-Caribbean American men may internalize or externalize the effects of discrimination on their self-esteem or identity differently. If so, their interpretations of discrimination experiences may affect the extent to which self-esteem mediates the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms. Thus, more research is needed that tests ethnic group differences as moderators of self-esteem’s possible meditation of the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms among these men.

Purpose of Current Study

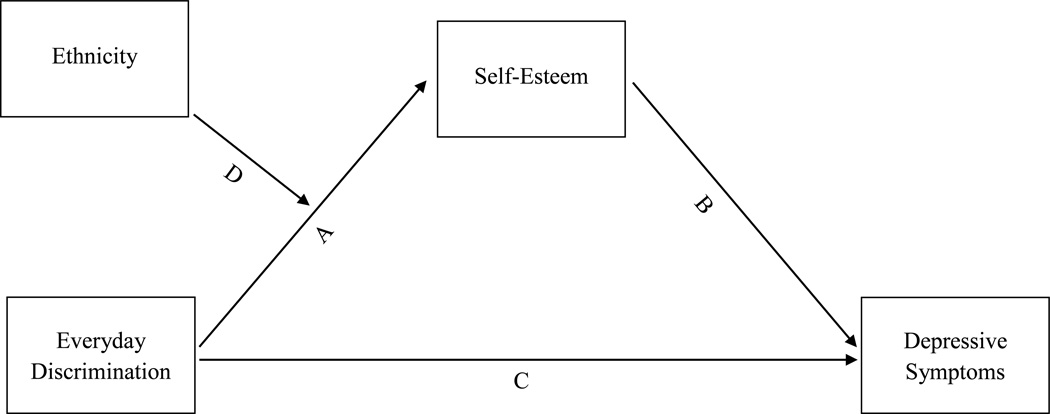

The purpose of the current study was to examine one mechanism by which discrimination is related to depressive symptoms among Black American men, after disaggregating ethnic groups. Specifically, we tested the mediating effects of self-esteem on the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms. As demonstrated in Figure 1 and supported by prior research6,7,9,10, we hypothesized that discrimination would be associated with depressive symptoms (Path C). We also hypothesized that discrimination would be associated with poorer self-esteem (Path A) and poorer self-esteem would be associated with more depressive symptoms (Path B). In sum, we hypothesized that self-esteem would mediate the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms. Given the diversity of racial socialization experiences and cultural practices among Black American men, we also examined how the mediating process might differ for African American and Afro-Caribbean American men. As such, we hypothesized that the mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms would be moderated by ethnic group membership for African American and Afro-Caribbean American men (Path D). Specifically, given that African American men have generally lived longer in the United States than Afro-Caribbean Americans and consequently have been exposed to discrimination intended to destroy their self-esteem for generations, we hypothesized that discrimination would be more strongly associated with poorer self-esteem for African American men than Afro-Caribbean American men.

Figure 1.

Moderated-mediation model of ethnicity and self-esteem on the relationship between everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms among African American and Afro-Caribbean American men.

METHODS

Procedure

Data from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research were used for the present study. Secondary data analyses were conducted on the National Survey of American Life data set (NSAL)26, which is part of the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys27. The NSAL is the first study that included a nationally representative sample of African Americans and Afro-Caribbean Americans. It was designed to examine the intra- and inter-group racial and ethnic differences on various factors (e.g., mental disorders, risk and protective factors, coping resources). Participants who self-identified as Black with non-Caribbean ancestry were considered African American, whereas participants who self-identified as Black with Caribbean ancestry were considered Afro-Caribbean Americans27.

Samples were generated using multi-stage probability methods of national household units, based on the 1990 census26,27. Data from the NSAL were collected from 2001 to 2003 mostly using face-to-face interviews, in which race/ethnic matching of interviewers was used. On average, interviews lasted 2 hours and 20 minutes for African Americans and 2 hours and 43 minutes for Afro-Caribbean Americans. A response rate of 70.7% for African Americans (N = 3,570) and 77.7% for Afro-Caribbean Americans (N = 1,623) was reported26. More information about consent and methods is provided elsewhere26,27. Only participants who identified as male were included in the study, which were 1,271 African American males and 562 Afro-Caribbean American males. Missing values were analyzed, and 87 cases were eliminated due to excessive missing data on the measures used for the study.

Participants

African American men

Participants were 1,201 African American males who ranged in age from 18 to 93 years (M = 43.29, SD = 16.22). Most of the participants were born in the United States (97.3%). Most sample participants had at least 12 years of education (75.1%) and were employed (70.4%). Participants were from the following regions in the U.S.: South (65%), Midwest (15.2%), Northeast (11.7%), and West (8.0%).

Afro-Caribbean American men

Participants were 545 Afro-Caribbean American males who ranged in age from 18 to 83 (M = 40.62 SD = 15.44). Only 26.3% of the participants were born in the United States, and 51.7% of the non U.S. born participants lived in the U.S. for at least 11 years. Some countries of origin for the Afro-Caribbean American participants included Jamaica (36.5%), Haiti (21.9%), and Trinidad and Tobago (10.9%). The sample participants had at least 12 years of education (78.7%) and were mostly employed (77.2%). Participants were from the following regions in the U.S.: Northeast (63.9%), South (33.9%), West (1.5%), and Midwest (0.7%).

Measures

Everyday perceived discrimination

Participants reported frequency of recent minor experiences of unfair treatment and character assaults using a 10-item measure of everyday perceived discrimination28. Participants were asked, “In your day-to-day life how often have any of the following things happened to you:” followed by items, such as “You are treated with less courtesy than other people,” “People act as if they are afraid of you,” and “You are followed around in stores.” Response options ranged from 1 (almost everyday) to 6 (never), and were reverse coded so that higher scores represent more frequent day-to-day discrimination experiences. For this investigation, Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients were α = .89 for African American men and α = .90 for Afro-Caribbean American men.

Self-esteem

The 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale29 was used to assess an individual’s overall perception of self-worth and value. Examples of items are: “I am a failure,” and “I am satisfied with myself.” Response options ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). All items except for positively worded items were reverse scored, so that higher scores indicated higher levels of self-esteem. The reliability coefficients for this investigation were α = .75 and .76 for African Americans and Afro-Caribbean Americans, respectively.

Depressive symptoms

The 12-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale was used to assess depressive symptoms experienced during the week (i.e., 7 days) prior to administration30. Sample items include, “I felt that everything I did was an effort,” and “I had crying spells.” Response options ranged from 0 [rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day)] to 3 [most or all of the time (5–7 days)]. Positively worded items were reverse scored; a high score on the scale indicated a greater number of depressive symptoms. The Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients for this investigation were α = .72 for both African American and Afro-Caribbean American men.

Nativity status

A one-item measure assessed for nativity status in the United States by coding US-born participants as 0 and foreign-born participants as 1, which is consistent with prior research using the NSAL dataset25.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

We first examined the correlations between the variables for each sample. The results of the correlations are presented in Table 1 for African American and Afro-Caribbean American men as well as basic descriptive data of the measures. Depressive symptoms, everyday discrimination, and self-esteem were all significantly associated for African American men. Similar patterns were found for Afro-Caribbean American men, with the exception that everyday discrimination and self-esteem were not associated.

Table 1.

Correlations among the Measures and Descriptive Statistics

| Measures | Depressive Symptoms |

Self-Esteem | Everyday Perceived Discrimination |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Symptoms | AA | −.50* | .27* | ACA | |

| Self-esteem | −.50* | −.06 | |||

| Everyday Perceived Discrimination | .29* | −.18* | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| African American Men (n = 1,201) | 0.51 (0.43) | 3.62 (0.42) | 2.34 (0.95) | ||

| Afro-Caribbean American Men (n = 545) | 0.49 (0.42) | 3.63 (0.41) | 2.32 (0.94) | ||

Note. Correlations results for African American (AA) men are in grey and are below the diagonal and results for Afro-Caribbean American (ACA) men are above the diagonal. SD = standard deviation.

p < .01

Moderated-Mediation Analyses

We conducted two hierarchical regressions to test the mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms and to test the moderating effect of ethnicity on the relationship between everyday discrimination and self-esteem. We accounted for nativity status in all analyses. Results are reported in Table 2. The results of the first regression model indicate that everyday discrimination was associated with more depressive symptoms while accounting for nativity status (B = .28, p < .001). The results of the last step of the model indicate that discrimination’s effects on depressive symptoms decreased (B = .22, p < .001) and self-esteem was associated with fewer depressive symptoms in the model (B = −.47, p < .001), providing support for partial mediation for the entire sample. The second regression model indicated that everyday discrimination was associated with less self-esteem (B = −.14, p < .001) and that ethnicity moderated the relationship between discrimination and self-esteem (B = .16, p < .05).

Table 2.

Results of the Mediation and Moderation Regression Models

| Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Depressive Symptoms | |

| B | β | |

| Step 1 | ||

| Nativity | −.04 | −.04 |

| Step 2 | ||

| Nativity | −.02 | −.02 |

| Discrimination | .13 | .28** |

| Step 3 | ||

| Nativity | −.03 | −.03 |

| Discrimination | .10 | .21** |

| Self-Esteem | −.48 | −.47** |

| Self-Esteem | ||

| Step 1 | ||

| Nativity | −.01 | −.01 |

| Step 2 | ||

| Nativity | −.07 | −.07 |

| Discrimination | −.07 | −.15** |

| Ethnicity | −.06 | −.07 |

| Step 2 | ||

| Nativity | −.06 | −.06 |

| Discrimination | −.03 | −.07 |

| Ethnicity | .06 | .07 |

| Ethnicity × Discrimination | −.05 | −.15* |

Note.

p < .05

p < .001

To test for potential moderated-mediation effects, a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure with 1,000 samples and 95% Confidence Interval (CI)31,32 was conducted using the PROCESS Macro v2.13 in SPSS 22. This analysis procedure provides at the levels of the moderator the conditional indirect effects of discrimination on depressive symptoms through self-esteem. The results indicate that the conditional indirect effects of everyday discrimination on depressive symptoms were significant for African American men (B = .04, SE = .01; 95% CI: .025, .054) but not Afro-Caribbean men (B = .02, SE = .01; 95% CI: −.004, .037), providing support for the mediation model only for African American men.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with the large body of research on the relationship between discrimination and poorer health outcomes4–7,10,33, we found support for our hypothesis that experiences of everyday discrimination are associated with depressive symptoms for both African American and Afro-Caribbean American men among a nationally representative U.S. sample. Thus, discrimination plays an important role in depressive symptoms for both groups of Black American men. Building on the existing literature, our study examined the mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between self-reported everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms and provided further nuance into this relationship by testing ethnic differences within the Black male population.

Our results provided support for self-esteem as a mediator of the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms for African American men but not for Afro-Caribbean American men. More specifically, everyday discrimination was associated with poorer self-esteem and in turn depressive symptoms only for African American men but not for Afro-Caribbean American men. This is an important finding as it underscores within-group variability in the experience of, and reaction to, discrimination among Black men in the U.S. Our results indicate that ethnic group membership served to protect Afro-Caribbean American’s self-esteem against everyday discrimination.

Possible explanations for the mixed findings of the mediation model for the two groups of Black men might be related to the length of time spent within in the U.S., differing racial socialization practices, and ways in which discrimination is perceived and evaluated. Of the participants in our study, almost all of the African American men were born in the U.S. whereas only about one fourth of the Afro-Caribbean American men were born in the U.S. Several researchers have posited that living longer in the U.S. is linked to more exposure to race-based stressors and in turn poorer health2,23–25. African American men have a longer history in the U.S. and exposure to racism; thus, discrimination may be internalized and consequently more deleterious to their self-esteem.

Given that a person’s evaluation of the discrimination experience affects how it may relate to their self-esteem15,16, the cultural differences between African American and Afro-Caribbean American men might affect their perceptions of discrimination and in turn affects their self-esteem. For example, depending on levels of acculturation, Afro-Caribbean American men might not identify or perceive experiences of discrimination in a similar way as a African American men2,25. Moreover, Afro-Caribbean Americans are more likely to exhibit some level of social distancing from African Americans and, by extension, their race-based experiences21,34. For first-generation Afro-Caribbean Americans who have likely spent years in a Caribbean setting where Blacks were the majority race and race-based discrimination differed from that encountered in the U.S., scholars have argued that they might be more likely to “maintain some distance between society’s unfavorable views of African Americans and their image of themselves as a different kind of black” (p. 383)35. This social distancing could serve to assist Afro-Caribbean American men in externalizing their experiences of discrimination thereby protecting their sense of self-esteem. Additionally, scholars have underscored that, although Afro-Caribbean Americans are portrayed as the “Black model minority” but might become similar to African Americans over years of socialization in the U.S., Afro-Caribbean Americans have distinctive group experiences and racial and ethnic constructions, and uniquely engage with U.S. systems and institutions36, which might serve to protect their self-esteem.

There were several limitations of our study. The study is limited by its cross-sectional design; thus, longitudinal research would provide stronger evidence for the directionality of the associations found in our study. The Afro-Caribbean sample was comprised of individuals from different ethnic groups and countries, thus it could be the case that they have varying experiences relative to their national, political, social, and economic histories of their home countries that uniquely influence their response to discrimination in the U.S. Further, the relatively large percentage of the Afro-Caribbean American sample were born outside of the United States and spent less than 11 years within the country largely limited the study to one of African Americans and first generation Caribbean immigrants. Given that research has identified the race-related experiences of subsequent generations of Afro-Caribbean American as differing from their first generation predecessors2,23,24, further study on the moderating effect of self-esteem within these groups is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results indicate that self-esteem is a mediator of the relationship between everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms for African American men but it was not for Afro-Caribbean men. We also found that everyday discrimination was significantly associated with depressive symptoms and self-esteem was significantly associated with depressive symptoms for both groups of men. The findings of the present study emphasize the need for further research aimed at exploring the influence of discrimination on depressive symptoms among heterogeneous samples of Black populations, especially relative to psychological resources, such as self-esteem. Additional research understanding the ways in which discrimination affects self-esteem, especially for African American men is warranted. Further exploration is needed to understand the role racial and ethnic identities play in moderating the effects of discrimination for immigrants of African ancestry living in the U.S. and for African Americans. More research is also need to better identify and understand other psychological processes operating in explaining the relationships between racism and discrimination and poorer health outcomes among heterogeneous samples of Black Americans. Furthermore, research including constructs related to gender socialization (e.g., masculinity) and its intersectionality with racial and ethnic socialization (e.g., gender racism) is needed to better understand Black American men’s experiences in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

Article preparation was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health (T32DA016184 ) in support of E. H. Mereish.

Contributor Information

Ethan H. Mereish, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, Brown University, ethan_mereish@brown.edu.

Hammad S. N’cho, Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University..

Carlton E. Green, Counseling Center, University of Maryland, College Park, cegreen@umd.edu.

Maryam M. Jernigan, Department of Psychology, University of Saint Joseph, 1678 Asylum Avenue, West Hartford, CT 06117, mjernigannoesi@usj.edu.

Janet E. Helms, Institute for the Study and Promotion of Race and Culture, Department of Counseling, Developmental, and Educational, Boston College, helmsja@bc.edu.

References

- 1.González HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the united states: Too little for too few. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DR, Haile R, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, Baser R, Jackson JS. The mental health of Black Caribbean immigrants: results from the National Survey of American Life. American journal of public health. 2007 Jan;97(1):52–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Utsey SO, Giesbrecht N, Hook J, Stanard PM. Cultural, sociofamilial, and psychological resources that inhibit psychological distress in African Americans exposed to stressful life events and race-related stress. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(1):49–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, Race-Based Discrimination, and Health Outcomes Among African Americans. Annual review of psychology. 2007;58:201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006 Aug 1;35(4):888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pascoe EA, Richman LS. Perceived Discrimination and Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological bulletin. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pieterse AL, Carter RT. An examination of the relationship between general life stress, racism-related stress, and psychological health among black men. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54(1):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR, Postmes T, Garcia A. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(4):921–948. doi: 10.1037/a0035754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. 2009/02/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown TN, Sellers SL, Gomez JP. The Relationship between Internalization and Self-Esteem among Black Adults. Sociological Focus. 2002;35(1):55–71. 2002/02/01. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassidy C, O'Connor RC, Howe C, Warden D. Perceived Discrimination and Psychological Distress: The Role of Personal and Ethnic Self-Esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51(3):329–339. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernando S. Racism as a cause of depression. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1984;30(1–2):41–49. doi: 10.1177/002076408403000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(5):1288–1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96(4):608–630. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crocker J, Quinn D. Racism and self-esteem. In: Fiske JLEST, editor. Confronting racism: The problem and the response. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1998. pp. 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139(1):213–240. doi: 10.1037/a0028931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Díaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: findings from 3 US cities. American journal of public health. 2001;91(6):927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. 2001/06/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer AR, Shaw CM. African Americans' mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: The moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46(3):395–407. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson JS, Antonucci TC. Physical and Mental Health Consequences of Aging in Place and Aging Out of Place Among Black Caribbean Immigrants. Research in Human Development. 2005;2(4):229–244. 2005/09/01. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waters MC. Black identities. Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Model S. Caribbean Immigrants: A Black Success Story? International Migration Review. 1991;25(2):248–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miranda J, Siddique J, Belin T, Kohn-Wood L. Depression prevalence in disadvantaged young black women. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol. 2005;40(4):253–258. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0879-0. 2005/04/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Case AD, Hunter CD. Cultural Racism–Related Stress in Black Caribbean Immigrants: Examining the Predictive Roles of Length of Residence and Racial Identity. Journal of Black Psychology. 2014 Oct 1;40(5):410–423. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall GL, Hooyman NR, Hill KG, Rue TC. Association of socio-demographic factors and parental education with depressive symptoms among older African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Aging & Mental Health. 2013;17(6):732–737. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.777394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, et al. The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The Prevalence, Distribution, and Mental Health Correlates of Perceived Discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent child. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977 Jun 1;1(3):385–401. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preacher K, Hayes A. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. 2008/08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modelling. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown TN, Williams DR, Jackson JS, et al. “Being black and feeling blue”: the mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race and Society. 2000;2(2):117–131. // [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones C, Erving CL. Structural Constraints and Lived Realities: Negotiating Racial and Ethnic Identities for African Caribbeans in the United States. Journal of Black Studies. 2015 Jul 1;46(5):521–546. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deaux K, Bikmen N, Gilkes A, et al. Becoming American: Stereotype Threat Effects in Afro-Caribbean Immigrant Groups. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2007 Dec 1;70(4):384–404. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers RR. Afro-Caribbean immigrants and the politics of incorporation: Ethnicity, exception, or exit. Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]