Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

Transcription profiles associated with mutated MYD88, CXCR4, ARID1A, abnormal cytogenetics including 6q−, and familial WM are described.

Mutated CXCR4 profiles show impaired expression of the tumor suppressor response induced by MYD88L265P and also G-protein/MAPK inhibitors.

Abstract

Whole-genome sequencing has identified highly prevalent somatic mutations including MYD88, CXCR4, and ARID1A in Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM). The impact of these and other somatic mutations on transcriptional regulation in WM remains to be clarified. We performed next-generation transcriptional profiling in 57 WM patients and compared findings to healthy donor B cells. Compared with healthy donors, WM patient samples showed greatly enhanced expression of the VDJ recombination genes DNTT, RAG1, and RAG2, but not AICDA. Genes related to CXCR4 signaling were also upregulated and included CXCR4, CXCL12, and VCAM1 regardless of CXCR4 mutation status, indicating a potential role for CXCR4 signaling in all WM patients. The WM transcriptional profile was equally dissimilar to healthy memory B cells and circulating B cells likely due increased differentiation rather than cellular origin. The profile for CXCR4 mutations corresponded to diminished B-cell differentiation and suppression of tumor suppressors upregulated by MYD88 mutations in a manner associated with the suppression of TLR4 signaling relative to those mutated for MYD88 alone. Promoter methylation studies of top findings failed to explain this suppressive effect but identified aberrant methylation patterns in MYD88 wild-type patients. CXCR4 and MYD88 transcription were negatively correlated, demonstrated allele-specific transcription bias, and, along with CXCL13, were associated with bone marrow disease involvement. Distinct gene expression profiles for patients with wild-type MYD88, mutated ARID1A, familial predisposition to WM, chr6q deletions, chr3q amplifications, and trisomy 4 are also described. The findings provide novel insights into the molecular pathogenesis and opportunities for targeted therapeutic strategies for WM.

Introduction

Whole-genome sequencing identified several highly recurring somatic mutations in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM).1,2 In over 90% of WM patients, a single point mutation at NM_002468:c.978T>C (rs387907272) in MYD88 is found, resulting in a p.Leu265Pro (L265P) amino acid change.1,3 MYD88 is an adaptor for Toll-like (TLR) and interleukin 1 (IL1) receptors, and the MYD88L265P mutation triggers constitutive activation of NF-κB through IRAK and BTK.1,4,5 Mutated MYD88 WM patients show greater overall survival and clinical responses to the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib.6,7

Activating CXCR4 frameshift or nonsense mutations in the C-terminal tail are found in 30% to 40% of WM patients, are primarily subclonal, and almost always associated with MYD88L265P.2,3,8 These somatic mutations are similar to the causal germ line variants that underlie WHIM (warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infection, and myelokathexis) syndrome.2,9 In WM, somatic CXCR4 mutations (CXCR4WHIM) are determinants of disease presentation, as well as resistance to ibrutinib.3,6,10 Somatic mutations in ARID1A, a member of the SWItch/sucrose nonfermentable family and epigenetic regulator, are also found in 20% of WM patients. Gene losses affecting NF-κB signaling (ie, HIVEP2, TNFAIP3), as well as the ARID1A homolog ARID1B are present in most WM patients.2,11 Deletions in chromosome 6q with and without concurrent 6p amplifications, trisomy 3, and amplifications of 3q, as well as trisomy 4, are also commonly found in WM.12-14 Previous array-based gene expression studies of WM were largely conducted prior to these genomic discoveries and therefore the effects of recurrent somatic events on transcriptional regulation remain to be clarified.15-17 We therefore performed next-generation RNA sequencing in 57 WM patients and compared findings to sorted healthy donor-derived nonmemory (CD19+CD27−) and memory (CD19+CD27+) B cells. The latter represent the B-cell population from where most cases of WM are thought to be derived.18,19

Methods

Sample selection and characterization

Bone marrow (BM) aspirates were collected from 57 patients with the WM consensus diagnosis.20 Participants provided informed consent for sample collection per the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board. WM cells were isolated by CD19+ magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) microbead selection (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) from Ficoll-Paque (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) separated BM mononuclear cells. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from nine healthy donors (HDs) were sorted for nonmemory (CD19+CD27−) and memory B cells (CD19+CD27+) using a memory B-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). RNA and DNA were purified using the AllPrep mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Most samples were previously characterized by whole-genome sequencing and all samples were screened for MYD88 and CXCR4 gene mutations by Sanger sequencing.2 MYD88L265P and CXCR4 c.1013C>G and c.1013C>A mutations were analyzed by allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as previously described.8,21

Next-generation sequencing and analysis

Transcriptome profiling was conducted by the Center for Cancer Computational Biology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA) using the NEBNext Ultra RNA library prep kit (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). The paired-end samples were run 2 per lane for 50 cycles on an Illumina HiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Read-level data are available through dbGAP accession (applied). Reads were aligned to KnownGene HG19/GRCh37 reference using STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference).22 Genes with mean raw read counts of <10 were not analyzed, leaving 16 888 expressed genes for analysis. Read counts per gene were obtained using featureCounts from Rsubread, and analyzed using voom from the edgeR/limma Bioconductor packages in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).23-27 Differential expression models accounted for sex, prior treatment, as well as MYD88 and CXCR4 mutation status. A false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of 10% was used to determine significant differentially expressed genes. Functional enrichment analysis was conducted using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Qiagen). Clustering and correlation analysis was conducted using the variance stabilizing transformation of the count data from the Bioconductor DESeq2 package.28 In all other cases, estimates of gene expression levels are represented in transcripts per million (TpM). Log-fold change (LFC) listed in text and tables are derived from the limma analysis.

CXCR4 transduced cell lines and gene expression analysis

Previously described BCWM.1 and MWCL-1 cell lines transduced to express CXCR4 with or without activating mutations observed in WM patients were used to model CXCR4-stimulated gene expression changes in WM.10 Briefly, CXCR4 complementary DNA (cDNA) transcripts were subcloned into plenti-internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)–green fluorescent protein (GFP) vectors, and stably transduced using a lentiviral system.4 In addition to wild-type (WT) CXCR4, vectors with the mutations c.1013C>G (p.Ser338*), c.932_933insT (p.Thr311fs), and c.1030_1041delinsGT (p.Ser344fs) were generated. Cell lines were stimulated with 50 nM of the CXCR4 ligand CXCL12 (SDF1A) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN) for 2 hours. RNA from each sample was extracted at baseline and at 2 hours. Gene expression was assessed using Affymetrix Human Gene ST 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Array data are archived in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE83150). Array data were analyzed using the Oligo and limma R bioconductor packages.24,29

Statistical analysis

Random forest analysis was implemented using the cforest function in the party package in R.30 Models were constructed using the cforest_unbiased function with 20 predictors per tree over 10 000 trees. As variable importance scores of nonsignificant genes are distributed around zero, genes were further filtered for those with permutation importance scores greater than the absolute value of the lowest scoring predictor. For reproducibility, the random seed for the analysis was set to 265. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted using R’s prcomp, Pearson’s product-moment coefficient was used for correlation studies, and cohort mean values were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Gene expression, sequencing, and methylation studies

Gene expression results were validated by using TaqMan gene expression assays Hs01027785_m1 (DUSP4), hs00244839_m1 (DUSP5), Hs00243182_m1 (RGS13), Hs00892674_m1 (RGS16), Hs00698249_m1 (RASSF6), Hs00396602_m1 (WNK2), Hs00924602_m1 (PRDM5) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA). Methylation-specific PCR assays for RASSF6, WNK2, and PRDM5 were conducted on bisulfite-converted DNA using previously established protocols.31-33

Results

The clinical characteristics for the 57 WM patients are presented in Table 1. The distribution of somatic mutations and cytogenetic findings in these patients was similar to those previously described.34 The top 500 differentially expressed genes for each comparison discussed below are available as a part of the supplemental Data (available on the Blood Web site).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Median or count | Range or percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, female | 21/57 | 36.8% |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 60 | 40-78 |

| β2 microglobulin at diagnosis >3, mg/L | 19/46 | 41.3% |

| Age at biopsy, y | 62 | 41-83 |

| Familial history of WM | 3/57 | 5.3% |

| Splenomegaly | 13/57 | 22.8% |

| Lymphadenopathy | 30/57 | 52.6% |

| Bone marrow involvement, % | 60 | 5-95 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 11.1 | 8.2-14.5 |

| Serum IgM, mg/dL | 3750 | 416-8320 |

| Serum IgG, mg/dL | 517 | 82-3890 |

| Serum IgA, mg/dL | 40 | 6-516 |

| MYD88 mutations | 52/57 | 91.2% |

| CXCR4 mutations | 23/57 | 40.0% |

| ARID1A mutations | 5/51 | 9.8% |

| CD79B mutations | 4/51 | 7.8% |

| Deletion chromosome 6q | 24/53 | 45.3% |

| Amplification chromosome 6p | 6/53 | 11.3% |

| Amplification chromosome 3q | 11/52 | 19.2% |

| Amplification chromosome 4 | 10/52 | 21.1% |

Comparing WM to healthy donor B cells

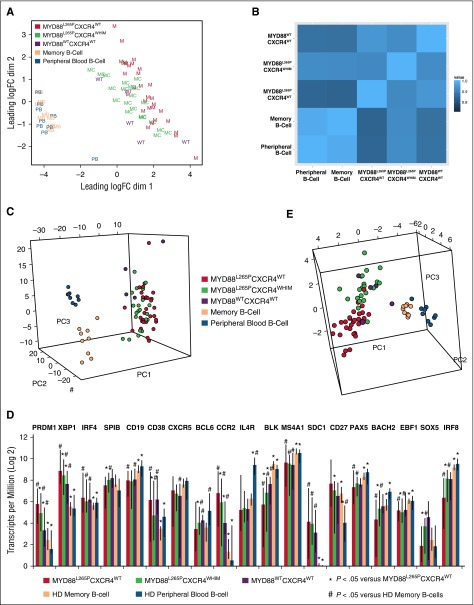

Comparison of WM and HD samples generated a list of 13 571 differentially expressed genes. To gain further insight into these gene expression differences, this gene list was sorted by absolute log2 fold change, revealing a marked upregulation of DNTT, RAG1, RAG2, and IGLL1 in WM samples. These genes have important functional roles in VDJ recombination and B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling. Other upregulated genes relevant to WM biology and pathogenesis included CXCL12, VCAM1, CD5L, BMP3, and IGF1. Among the top 40 differentially expressed genes sorted by absolute expression in WM as measured in TpM were CXCR4, the WM prognostic marker B2M, and 2 genes related to BCR signaling: CD79A and CD79B. To examine transcriptional similarities between the samples in an unbiased manner, multidimensional scaling of the 500 genes with the highest variance was used to best represent the data in 2 dimensions (Figure 1A). Although peripheral B cells (PBs) and HD memory B cells (MBs) clustered together, separation between MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM and MYD88L265PCXCR4WT genotyped WM patient samples was observed. To examine whether the patterns of expression were similar between HD samples and patient mutational groups, a correlation coefficient based on overall gene expression was generated for each sample-to-sample comparison. These values were averaged together by HD PB/MB cell type and WM MYD88/CXCR4 genotype to show the extent of correlation between groups (Figure 1B). Strong correlations were observed across all subsets, though mean correlation values between HD B cells and MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM patients were significantly higher vs those between HD B cells and MYD88L265PCXCR4WT patients (P = .025 and P = .036 for PB and MB cells, respectively).

Figure 1.

Comparisons of transcriptional activity for genotyped WM patient samples and healthy donor B cells. (A) Multidimensional scaling of the top 500 genes for all HD and WM samples using Voom transformed expression values in Limma’s plotMDS function.24 (B) Pearson correlation coefficients from the correlation matrix of gene expression were averaged over all the samples for each major group. Correlation values with the HD samples were higher for those WM patients with CXCR4 mutations (P = .025 and P = .036 for HD PB and HD MB cells, respectively). (C) The 596 genes differentially expressed between the HD PB and HD MB cells were analyzed across all samples using PCA. No preferential relationship between WM samples and HD B-cell type was observed. The first 3 principal components were used to plot the samples representing 54% of the overall variability. (D) Median expression levels for 19 genes known to regulate B-cell to plasma cell transition for HD B-cell and genotyped WM samples. Error bars represent full data range per for each group. (E) PCA of the 19 genes related to B-cell to plasma cell transition shown in panel D depicting the first 3 principal components which covered over 65% of the overall gene expression variability.

No preferential association was noted between WM samples and HD B-cell type using PCA of the 596 genes differentially expressed between HD PB and MB cells (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 1). To better understand the role of B-cell differentiation in WM, we analyzed 19 genes linked to the transition from MB to plasmablasts and plasma cells (Figure 1D).35,36 Many of these genes were not only significantly differentially expressed between HD and WM samples, but between WM patients based on MYD88 and CXCR4 mutation status suggesting reduced differentiation in both MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM and, in particular, MYD88WTCXCR4WT samples. Separation of patient samples by genotype can be seen in the PCA of these 19 genes in Figure 1E. BCL2 and BCL2L1 were upregulated in all WM samples, however, analysis of the larger BCL2 family revealed stratification of samples by HD cell type and MYD88/CXCR4 mutation status (supplemental Figure 2). The proapoptotic BAX gene was downregulated in WM samples and PMAIP1 was uniquely upregulated in MYD88L265PCXCR4WT WM.

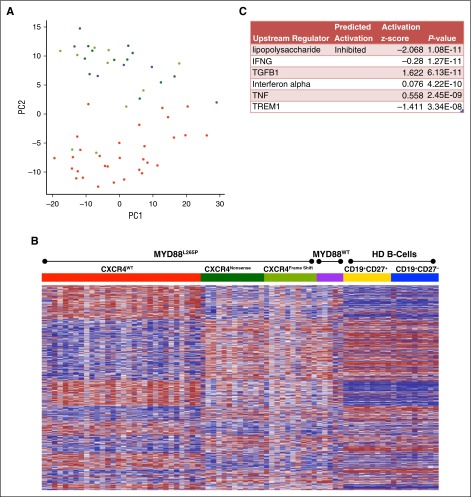

Transcriptional effects of CXCR4WHIM

Restricting the analysis to WM patients, PCA of the top 500 high variance genes accounted for 41% of the overall variability within the first 2 components (Figure 2A). Tumor suppressors including WNK2, TP53I11, PRDM5, and CABLES1 influence the second principal component that separates MYD88L265PCXCR4WT from MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM and MYD88WTCXCR4WT samples (supplemental Figure 1). Supervised clustering of the 3103 genes differentially expressed between MYD88L265PCXCR4WT and MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM revealed that most expression differences in MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM patients followed a pattern resembling HD samples, despite carrying the MYD88L265P mutation (Figure 2B). The top predicted upstream regulator for this gene signature was the inhibition of lipopolysaccharide signaling (Figure 2C). To further explore how CXCR4 mutations modulate MYD88 signaling in WM, the gene signature was filtered for genes involved in TLR signaling. MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM patients showed downregulation of the lipopolysaccharide receptors TLR4 and NOD2, and upregulation of TLR7 and IRAK3 (supplemental Figure 3A). The most significant results associated with CXCR4 mutation status were silencing of genes in patients with MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM that were elevated in MYD88L265PCXCR4WT patients (supplemental Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Role of CXCR4WHIM mutations in MYD88L265P-mutated WM. (A) PCA of the top 500 high variance genes within the WM patient samples using the first 2 principal components. WM patients with the MYD88L265PCXCR4WT genotype are shown in red; patients mutated for MYD88 with CXCR4 nonsense (NS) or frameshift (FS) mutations are shown in dark and light green, respectively; and patients with MYD88WTCXCR4WT are shown in purple. (B) Heat map of the 3103 genes differentially expressed between the MYD88L265PCXCR4WT and MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM genotyped samples. Gene order was determined using hierarchical clustering of MYD88L265PCXCR4WT and MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM expression data whereas the samples where arranged by genotype. Expression data for MYD88WTCXCR4WT WM and healthy donor B-cell samples were added to the heat map for comparison with intact clustered gene order. (C) Top predicted upstream targets of the differentially expressed genes from Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

Promoter methylation studies

To investigate the role of methylation in genes differentially expressed based on CXCR4 and MYD88 mutation status, 3 such genes were selected for screening based on their regulation by promoter methylation in other malignancies: PRDM5, WNK2, and RASSF6.32,33,37 Gene expression was validated by PCR in HD B-cell samples as well as in MYD88 and CXCR4 genotyped WM patient samples (supplemental Figure 4A). Mirroring the transcriptome data, RASSF6 expression was elevated in MYD88L265PCXCR4WT and MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM samples but not in HD or MYD88WT samples whereas WNK2 and PRDM5 were elevated only in the MYD88L265PCXCR4WT patients. To determine relevance of these methylation sites in hematologic malignancies, WM, B-cell lymphoma, and myeloma cell lines were assessed for promoter methylation using methylation-specific PCR assays (supplemental Figure 4B). Sixteen MYD88 and CXCR4 genotyped primary WM patient samples and 4 healthy donor B-cell samples were then tested (supplemental Figure 4C). Robust promoter methylation was observed for WNK2 and PRDM5 in the MYD88WTCXCR4WT patients but was absent in HD samples. Partial promoter methylation of WNK2 and PRDM5 was also observed in some MYD88L265P samples. This correlated to a relative reduction in gene expression only for WNK2 in the MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM genotyped patient sample with the strongest methylation signal.

Cell line models of CXCR4WHIM signaling

To better understand interactions between CXCR4WHIM and MYD88L265P in WM, lentiviral transduction was performed to overexpress CXCR4WT, or 1 of 3 documented CXCR4WHIM transcripts (c.1013C>G, c.932_933insT, or c.1030_1041delinsGT) in MYD88L265P expressing BCWM.1 WM cells. Transduced cells were stimulated in triplicate with CXCL12 for 2 hours and gene expression profiling performed. The relative change in gene expression from baseline was then compared between CXCR4WT and CXCR4WHIM transduced cells revealing 61 differentially expressed genes. Of these genes, 16 of 61 (26.2%) were encompassed in the gene expression signature for MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM patient samples (supplemental Table 1). In 8 of 16 (50%) of these genes, the direction of the change relative to MYD88L265PCXCR4WT was same as that observed in the patient samples. However, it was the genes whose direction of change was opposed that revealed the most about the underlying biology. These discordant genes were enriched for suppressors of MAPK and G-protein signaling downstream of CXCR4. They were preferentially induced in CXCR4WHIM cell lines by CXCL12 stimulation and suppressed in MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM patient samples.10,38 Interrogation of these dual specificity phosphatases (DUSP) and regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) genes revealed RGS1, RGS2, RGS13, DUSP1, DUSP2, DUSP4, DUSP5, DUSP10, DUSP16, and DUSP22 were all significantly suppressed in MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM vs MYD88L265PCXCR4WT patients. Expression in patients of DUSP4, DUSP5, RGS13, and RGS16, which were selected for validation based on the cell line studies, can be seen in supplemental Figure 5A. The increased expression of these genes in CXCR4WHIM compared with CXCR4WT transduced lines was validated by real-time PCR (supplemental Figure 5B). Dose-response curves for these genes following CXCL12 stimulation was conducted in transduced BCWM.1 and MWCL-1 (supplemental Figure 5C).

Gene signatures associated with other clinical and genomic features

For the 5 patients with ARID1A mutations, 16 differentially expressed genes were observed. The ARID1A-mutated population also demonstrated elevated BM disease infiltration (median, 90%; range, 70%-95%) when compared with non-ARID1A-mutated patients (median, 58%; range, 5%-95%; P = .0259). No statistically significant gene expression changes were observed in the 4 patients with CD79B mutations. Analysis based on somatic cytogenetic abnormalities included deletion of chromosome 6q (131 genes), amplification of chromosome 6p (65 genes), amplification of chr3q including trisomy 3 (11 genes), and trisomy 4 (776 genes). A distinct gene expression signature for 263 genes was also observed in the 3 patients who had first-degree relatives with WM. No statistically significant differences in gene expression were observed based on presence of extramedullary disease, elevated B2M levels (>3 mg/dL), or International Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Prognostic Scoring System score.

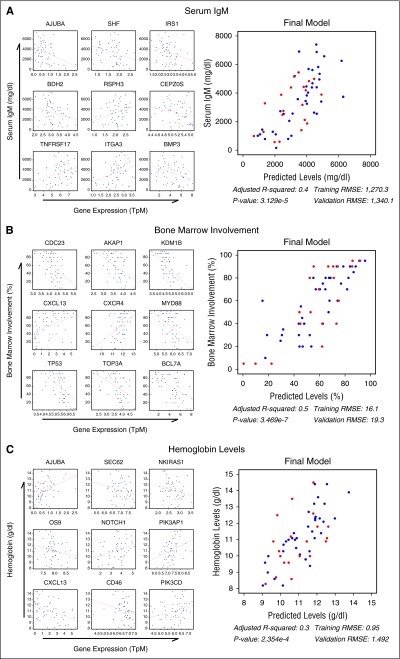

To identify genes associated with relevant WM clinical parameters, all genes were tested for correlation with serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels, hemoglobin, and BM disease involvement. After filtering the results by significance (P < .05) and the absolute value of the correlation estimate >0.3, 312 genes were found to be associated with IgM, 965 with hemoglobin, and 3738 with BM involvement. These genes were combined with MYD88/CXCR4 genotype, age, sex, and treatment status in a random forest regression analysis for the first 37 study patients, leaving the remaining 20 patients for cross-validation. Filtering genes/predictors by variable importance score resulted in 40, 236, and 143 associated genes for IgM, BM, and hemoglobin, respectively (supplemental Figure 6). Functional analysis was conducted on each gene list and top genes from each group were selected based on biological significance. The 40 genes associated with IgM were predicted to be downstream of IL6 signaling (P = .0018) and included many genes of WM pathogenic interest including TNFRSF17, BMP3, IRS1, and CEPZOS (Figure 3A). Many genes relevant to WM biology, including CXCL13, TP53, CXCR4, MYD88, CDC23, and AKAP1, were associated with BM disease involvement (Figure 3B). Although MYD88 and CXCR4 were both correlated to BM disease involvement (ρ = −0.50; P < .0001 and ρ = 0.46; P = .0003, respectively), they were negatively correlated with each other (ρ = −0.46; P = .0004). As shown in supplemental Figure 7, this relationship may be influenced by MD88/CXCR4 mutation status. The gene list associated with hemoglobin included CXCL13, as well as PIK3AP1, PIK3CD, AJUBA, and OS9 (Figure 3C). Based on these findings, CXCL13 was included in an independent serum cytokine profiling study of 86 WM patients that validated the CXCL13 correlation between BM (Spearman ρ = 0.562; P = 2.192 × 10−8) and hemoglobin (Spearman ρ = −0.567; P = 1.53 × 10−8).39

Figure 3.

Random forest analysis of gene expression identifies genes predictive of important clinical features in WM patients. Gene expression from the first 37 WM samples were analyzed for their utility in predicting serum IgM (A), BM disease involvement (B), and hemoglobin (C) levels using a random forest analysis. Of the statistically significant genes, the top 9 genes from each group deemed the most biologically relevant are shown as single variable correlates and incorporated into a final linear model using the full data set to demonstrate their predictive utility. The final 20 samples withheld for validation are shown in red and the root mean squared error (RMSE) of the final model for both the training and validation subsets is shown. P values have been adjusted for multiple hypotheses testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR.

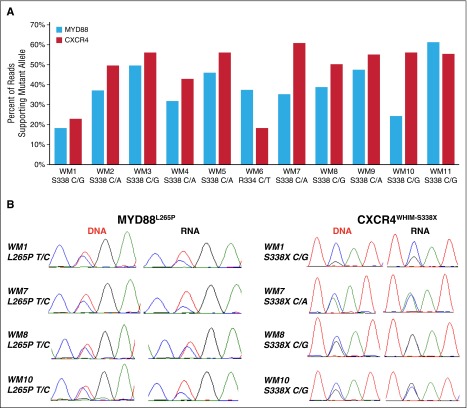

Analysis of mutant allele burden

The percentage of reads supporting the mutant allele relative to WT allele was calculated for MYD88, CXCR4, ARID1A, and CD79B in the RNA sequencing data. Although the relevant mutations were observed in the RNA in all cases, many samples with CXCR4WHIM mutations had mutant allele burdens in excess of 50%, an unexpected finding for a typically subclonal variant.8 As there can be differences in mapping efficiencies between indels and single-nucleotide variants, MYD88L265P allele burden was then compared with the CXCR4WHIM allele burden at the RNA level for the 11 patients with nonsense CXCR4 somatic mutations (Figure 4A). The median percentage of mutant reads was 37.4% (range, 18.4%-61.4%) and 54.5% (range, 18.2%-60.9%) for MYD88 and CXCR4, respectively (P = .0537) with the mutant allele burden of CXCR4 being greater than MYD88 in 9 of 11 patients (81.8%). Sanger sequencing of paired DNA and cDNA confirmed the mutant allele was underrepresented in the cDNA relative to the DNA for MYD88L265P in many patients whereas the opposite was true for CXCR4 mutations (Figure 4B). This reduced expression of MYD88L265P at the RNA level was also observed in some CXCR4WT patients.

Figure 4.

Mutant allele fraction analysis for MYD88 and CXCR4 in concurrent DNA and RNA WM patient samples. (A) Percentage of reads supporting the mutant allele of MYD88 and CXCR4 for 11 patients with MYD88L265P and nonsense (NS) CXCR4WHIM mutations. Median coverage of the affected nucleotide was 193 (range, 38-456) reads for MYD88 and 11 760 (range, 3318-15 883) reads for CXCR4. The amino acid location and nucleotide change for the CXCR4WHIM-NS mutation is listed for each patient sample. (B) Sanger sequencing of paired DNA and cDNA validated the mutant allele fraction for CXCR4 and MYD88 at the RNA and DNA levels.

Discussion

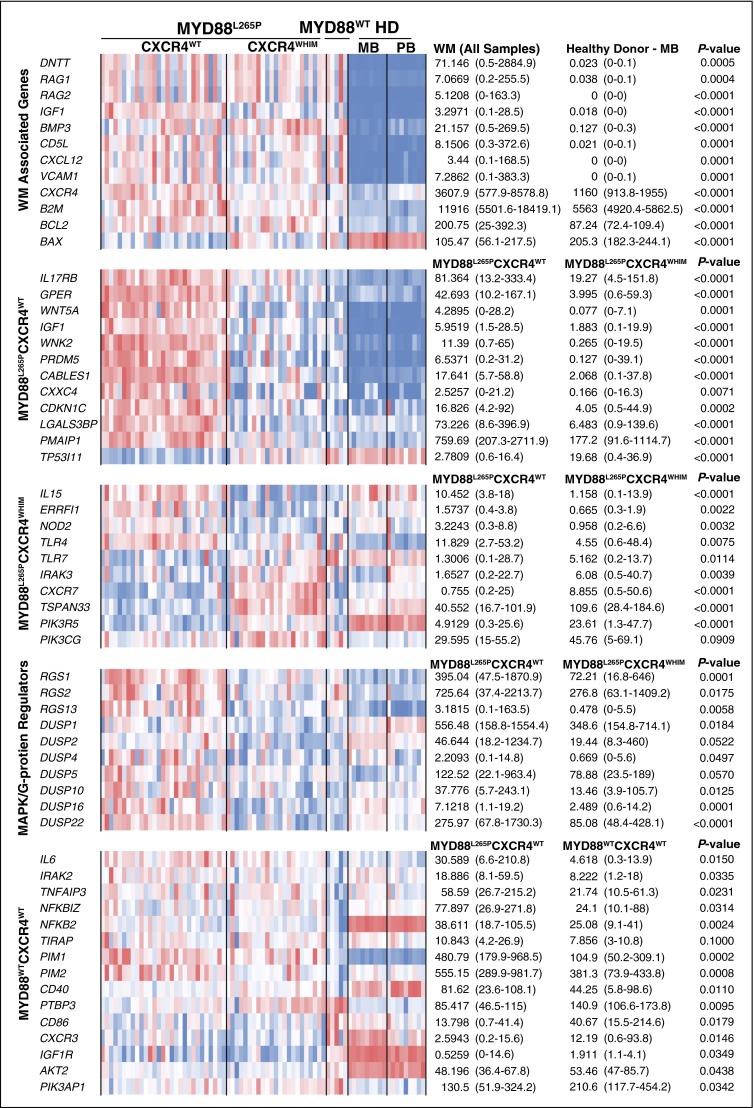

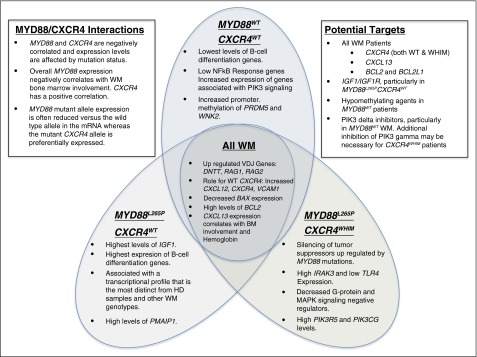

This study represents the first profile of the transcriptional landscape of WM by next-generation sequencing. Among the most striking findings was a >7.8 log-fold upregulation of VDJ recombination related genes including RAG1, RAG2, and DNTT in WM patients samples (Figures 5 and 6). The class switch recombination gene AICDA was not observed at meaningful levels consistent with the lack of immunoglobulin class switching in WM. The overexpression of RAG1 and RAG2 is notable because specific somatic mutation patterns such as deletions in BTG1 and ETV6 are associated with their aberrant expression, and are commonly observed in WM patients.2,40,41 The universal expression of CXCR4 and the upregulation of its ligand CXCL12 are suggestive of autocrine/paracrine signaling. CXCR4 activation has been reported to increase cell adhesion to VCAM1 via VLA4, and VCAM1 was the eighth most upregulated gene relative vs HD samples.42,43 Taken together, these findings suggest that VCAM1, CXCR4, and CXCL12 may facilitate the homotypic WM cell clustering observed in the BM of many WM patients. Likewise, IGF1, an inducer of AKT1 survival signaling in WM, was a top hit among the most upregulated genes. IGF1 and its receptor IGF1R may therefore be potential therapeutic targets in WM and warrant further investigation.44

Figure 5.

Summary of key gene expression differences. Gene expression levels for all study samples are shown depicting key differences for WM vs normal B-cell samples as well as WM patient intrapatient differences based on MYD88 and CXCR4 genotype. The heat map represents log2 transformed TpM values with median and range TpM values listed for each relevant comparator. P values have been adjusted for multiple hypotheses testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR.

Figure 6.

Summary of key findings by MYD88 and CXCR4 mutation status. Key findings from the transcriptome analysis for all WM samples as well as findings specific to MYD88L265PCXCR4WT, MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM, and MYD88L265PCXCR4WT WM patients. Additional notes on potential therapeutic targets and findings regarding MYD88 and CXCR4 interactions are also listed.

Despite previous studies suggesting that WM was derived from MB, we did not observe increased similarity at the transcription level for MB relative PB as shown in Figure 1B, C, and E. WM represents activated B cells in the processes of differentiating to plasma cells, evidenced by the high levels of XBP1, PRDM1, and SDC1, which may obscure signaling indicative of the true cell of origin. However, clustering by genes related to B-cell differentiation effectively sorted samples from patients with MYD88L265PCXCR4WT vs MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM and MYD88WTCXCR4WT suggesting that the latter may represent an earlier stage of B-cell differentiation, consistent with the previously established lower rate of IgH somatic hypermutation in MYD88WT WM.45

The majority of transcriptional differences between MYD88L265PCXCR4WT and MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM represented normalization of the latter for TLR4 signaling associated gene expression. This finding may help explain why CXCR4WHIM mutations are found almost exclusively in MYD88-mutated patients. Others have also reported that CXCR4 activation can affect TLR4 signaling.46-48 Regardless of mechanism, the direct downregulation of TLR4, and upregulation of IRAK3 in CXCR4WHIM patients may be the most proximal explanation for this phenomenon. Although IRAK3 is a negative regulator of the IRAK4/1 signaling cascade, it has been shown that BTK activation downstream of MYD88 occurs independently of IRAK4/1 and is likely unaffected by IRAK3 upregulation.4,49 In addition, TLR7 is upregulated in CXCR4WHIM patients and can use the MYD88/IRAK4/IRAK3 complex to initiate regulatory signaling through MAP3K3-dependent activation of NF-κB.50

Compared with the other WM genotypes and healthy donor B cells, WM patients with the MYD88L265PCXCR4WT genotype strongly upregulate a number of surface receptors and signaling molecules including IL17RB, GPER1, WNT5A, and IGF1. IL17RB signaling may provide an additional source of NF-κB activation whereas GPER1 and IGF1 activate AKT1 and MAPK signaling in marginal zone lymphoma and WM, respectively.44,51,52 However, WNT5A is a suppressor of B-cell proliferation.53 Many of the genes upregulated in the MYD88L265PCXCR4WT patient cohort such as PMAIP1, WNK2, PRDM5, CABLES1, CXXC4, and CDKN1C are tumor suppressors that either promote apoptosis, inhibit cell cycle, or block MAPK signaling.54-58 Normalization of MYD88L265P-associated tumor suppressor expression in CXCR4-mutated WM patients may provide the clearest explanation for the selective inhibition of MYD88 signaling observed in CXCR4WHIM patients. This yin-and-yang relationship between MYD88 and CXCR4 is further supported by the modulation of allele specific transcription, decreasing and increasing the mutation allele burden of each gene, respectively. CXCR4 and MYD88 total transcription levels were negatively correlated and inversely predictive of BM disease involvement. Although aberrant promoter methylation of WNK2 and PRDM5 was prominent in MYD88WTCXCR4WT samples, it did not explain the low levels of WNK2 and PRDM5 observed in patients with CXCR4WHIM mutations, thereby strengthening the case that these findings are related to CXCR4WHIM signaling rather than unrelated epigenomic events.

The strongest gene markers for patients with MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM was the upregulation of CXCR7, which like CXCR4 is activated by CXCL12, and TSPAN33 which is upregulated in activated B cells.59,60 IL15 was uniquely suppressed in patients with MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM and warrants functional studies to assess its role in WM microenvironment. Preclinical studies have shown that CXCR4WHIM transduced cell lines are resistant to PIK3CD inhibitors such as idelalisib.10,38 Both PIK3R5 and PIK3CG were significantly higher in CXCR4WHIM patients. PIK3R5 interacts with the β/γ G-protein subunits downstream of G-protein–coupled receptors such as CXCR4 to activate PIK3CG which may explain the observed resistance.61 The G-protein and MAPK inhibitors RGS1, RGS2, RGS13, DUSP1, DUSP2, DUSP4, DUSP5, DUSP10, DUSP16, and DUSP22 as well as the MAPK-inducible tumor suppressor ERRFI1 were significantly downregulated in patients with MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM vs MYD88L265PCXCR4WT.62 The fact that DUSP2, DUSP4, DUSP5, RGS13, and ERRFI1 were all significantly induced by CXCL12 in CXCR4WHIM vs CXCR4WT-transduced lines supports a role for these genes as negative regulators of CXCR4 signaling and may have implications for MYD88 MAPK signaling as well.63,64 This is similar to a number of secondary events such as MYBBP1A mutations and deletions of TRAF3, TNFAIP3, and HIVEP2, which are thought to represent loss of negative regulators for NF-κB signaling in WM.2,11,65 The mechanism(s) by which negative regulators of CXCR4 signaling are lost in patients with CXCR4WHIM mutations remain to be clarified warranting further investigation.

Of the 1155 genes that were differentially expressed between MYD88L265P and MYD88WT patients, 552 were not observed in the MYD88L265PCXCR4WT vs MYD88L265PCXCR4WHIM gene signature. MYD88WT patient expression was quite heterogeneous indicating pathogenetic diversity in this population. Large-scale genomic exploration will invariably be needed to help clarify the genetic basis for MYD88WT WM disease. Regardless, a clear downregulation of genes associated with NF-κB signaling including IL6, IRAK2, TNFAIP3, NFKBIZ, NFKB2, TIRAP, PIM1, and PIM2 was observed in these patients. Other genes of interest included the downregulation of CD40, and upregulation of PTBP3, CD86, and CXCR3. Notably, IGF1R, PIK3AP1, and AKT2 were all upregulated, suggesting a reliance on PIK3 signaling. The antiapoptotic gene BCL2, known to play an important role in WM, was overexpressed expressed in all patient samples while the proapoptotic BAX was underexpressed, suggesting a mechanism independent of the MYD88 and CXCR4 mutations.65-67

Somatic mutations in ARID1A were associated with increased CXCL13, as well as increased BM infiltration. CXCL13 has not been previously described in WM and was also a strong predictor of BM disease involvement and hemoglobin levels. CXCL13 may also play a role in mast cell recruitment.68 Mast cells can be observed admixed with the WM B cells in patient BM histology and are thought to play an important supportive role in the tumor microenvironment of WM.69 Deletions of chromosome 6q were associated with over 131 differentially expressed genes. Levels of previously identified target genes such as the NF-κB negative regulator HIVEP2, as well as BCLAF1, FOXO3 and ARID1B were all suppressed in the presence of 6q deletions.2 Although only 3 patients had strong familial predisposition to WM, these patients demonstrated significant dysregulation of several cancer-associated genes including RB1, STAT5B, ZNF300, MAPK9, and NFKB1.

These studies highlight the pivotal roles of MYD88 and CXCR4 signaling in WM. CXCR4 mutations appear to function primarily as dampeners of negative regulators that are upregulated in response to mutant MYD88 signaling. The upregulation of the ligand, adhesion targets, and CXCR4 itself in all WM patients provides evidence for uniform CXCR4 dysregulation in WM and supports the development of CXCR4 antagonists for WM therapy. The upregulation of PIK3 pathway members and the increased promoter methylation in MYD88WT patients creates a strong rationale for preclinical studies of PIK3 inhibitors and demethylating agents in this population. The upregulation of BCL2 across all WM patient genotypes also supports the development of BCL2 antagonists. Finally, CXCL13 is highly expressed by WM cells, and its expression correlates with important clinical parameters. Further studies to delineate therapeutic targeting of this cytokine in WM are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Yaoyu Wang and John Quackenbush at the Center for Cancer Computational Biology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for RNA Sequencing, and Mathew Temple, Leutz Buon, Terry Haley, and the Dana-Farber Research Computing Center for their invaluable assistance. The authors acknowledge the generous support of the WM patients who provided their samples.

This work was supported by Peter S. Bing, a Translational Research grant from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, a grant from the International Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia Foundation, a National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Spore 5P50CA100707-12 Research Development Award, and the Orzag Family Fund for WM Research.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: Z.R.H. and S.P.T. designed the study and wrote the manuscript; Z.R.H. performed the data analysis and informatics studies; X.L. and N.T. performed the validation and methylation studies; G.Y., X.L., and J.C. transduced the cell lines and ran the stimulations; L.X., X.L., J.C., J.G.C., J.M.V., and N.T. prepared the study samples; S.P.T., J.J.C., and T.D. provided patient care and obtained consent and samples; R.J.M., P.B., J.G., and C.J.P. selected samples and provided clinical data analysis; and S.P.T., N.M.M., and K.C.A. reviewed the data and provided expert guidance.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Steven P. Treon, Bing Center for Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, M547, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: steven_treon@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, et al. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):826–833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter ZR, Xu L, Yang G, et al. The genomic landscape of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia is characterized by highly recurring MYD88 and WHIM-like CXCR4 mutations, and small somatic deletions associated with B-cell lymphomagenesis. Blood. 2014;123(11):1637–1646. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-525808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treon SP, Cao Y, Xu L, Yang G, Liu X, Hunter ZR. Somatic mutations in MYD88 and CXCR4 are determinants of clinical presentation and overall survival in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2014;123(18):2791–2796. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-550905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang G, Zhou Y, Liu X, et al. A mutation in MYD88 (L265P) supports the survival of lymphoplasmacytic cells by activation of Bruton tyrosine kinase in Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2013;122(7):1222–1232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-475111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ngo VN, Young RM, Schmitz R, et al. Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature. 2011;470(7332):115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature09671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treon SP, Tripsas CK, Meid K, et al. Ibrutinib in previously treated Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):1430–1440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treon SP, Xu L, Hunter Z. MYD88 mutations and response to ibrutinib in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(6):584–586. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1506192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu L, Hunter ZR, Tsakmaklis N, et al. Clonal architecture of CXCR4 WHIM-like mutations in Waldenström macroglobulinaemia. Br J Haematol. 2016;172(5):735–744. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez PA, Gorlin RJ, Lukens JN, et al. Mutations in the chemokine receptor gene CXCR4 are associated with WHIM syndrome, a combined immunodeficiency disease. Nat Genet. 2003;34(1):70–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao Y, Hunter ZR, Liu X, et al. The WHIM-like CXCR4(S338X) somatic mutation activates AKT and ERK, and promotes resistance to ibrutinib and other agents used in the treatment of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Leukemia. 2015;29(1):169–176. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braggio E, Keats JJ, Leleu X, et al. Identification of copy number abnormalities and inactivating mutations in two negative regulators of nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathways in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Cancer Res. 2009;69(8):3579–3588. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braggio E, Dogan A, Keats JJ, et al. Genomic analysis of marginal zone and lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas identified common and disease-specific abnormalities. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(5):651–660. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schop RFJ, Van Wier SA, Xu R, et al. 6q deletion discriminates Waldenström macroglobulinemia from IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;169(2):150–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Treon SP, Hunter ZR, Aggarwal A, et al. Characterization of familial Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(3):488–494. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chng WJ, Schop RF, Price-Troska T, et al. Gene-expression profiling of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia reveals a phenotype more similar to chronic lymphocytic leukemia than multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108(8):2755–2763. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutiérrez NC, Ocio EM, de Las Rivas J, et al. Gene expression profiling of B lymphocytes and plasma cells from Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia: comparison with expression patterns of the same cell counterparts from chronic lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma and normal individuals. Leukemia. 2007;21(3):541-549. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Poulain S, Roumier C, Venet-Caillault A, et al. Genomic landscape of CXCR4 mutations in Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(6):1480–1488. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahota SS, Babbage G, Weston-Bell NJ. CD27 in defining memory B-cell origins in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9(1):33–35. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2009.n.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janz S. Waldenström macroglobulinemia: clinical and immunological aspects, natural history, cell of origin, and emerging mouse models. ISRN Hematol. 2013;2013:815325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Owen RG, Treon SP, Al-Katib A, et al. Clinicopathological definition of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: consensus panel recommendations from the Second International Workshop on Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(2):110–115. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2003.50082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu L, Hunter ZR, Yang G, et al. MYD88 L265P in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, IgM monoclonal gammopathy, and other B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders using conventional and quantitative allele-specific PCR [published correction appears in Blood. 2013;121(26):5259]. Blood. 2013;121(11):2051–2058. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-454355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014;15(2):R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(7):923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5(10):R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carvalho BS, Irizarry RA. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2363–2367. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hothorn T, Hornik K, Zeileis A. Unbiased recursive partitioning: a conditional inference framework. J Comput Graph Stat. 2006;15(3):651–674. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiong Z, Laird PW. COBRA: a sensitive and quantitative DNA methylation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(12):2532–2534. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moniz S, Martinho O, Pinto F, et al. Loss of WNK2 expression by promoter gene methylation occurs in adult gliomas and triggers Rac1-mediated tumour cell invasiveness. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(1):84–95. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan S-X, Hu R-C, Liu J-J, Tan Y-L, Liu W-E. Methylation of PRDM2, PRDM5 and PRDM16 genes in lung cancer cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(5):2305–2311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Treon SP. How I treat Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2015;126(6):721–732. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-553974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarte K, Zhan F, De Vos J, Klein B, Shaughnessy J., Jr Gene expression profiling of plasma cells and plasmablasts: toward a better understanding of the late stages of B-cell differentiation. Blood. 2003;102(2):592–600. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jourdan M, Caraux A, Caron G, et al. Characterization of a transitional preplasmablast population in the process of human B cell to plasma cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2011;187(8):3931–3941. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Djos A, Martinsson T, Kogner P, Carén H. The RASSF gene family members RASSF5, RASSF6 and RASSF7 show frequent DNA methylation in neuroblastoma. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Jimenez C, et al. C1013G/CXCR4 acts as a driver mutation of tumor progression and modulator of drug resistance in lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123(26):4120–4131. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-564583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vos JM, Tsakmaklis N, Brodsky PS, et al. Biologically meaningful changes in cytokine and chemokine production following ibrutinib therapy in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Hematologica. 2016. Abstract P312. In press.

- 40.Waanders E, Scheijen B, van der Meer LT, et al. The origin and nature of tightly clustered BTG1 deletions in precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia support a model of multiclonal evolution. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(2):e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papaemmanuil E, Rapado I, Li Y, et al. RAG-mediated recombination is the predominant driver of oncogenic rearrangement in ETV6-RUNX1 acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):116–125. doi: 10.1038/ng.2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ngo HT, Leleu X, Lee J, et al. SDF-1/CXCR4 and VLA-4 interaction regulates homing in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2008;112(1):150–158. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petty JM, Lenox CC, Weiss DJ, Poynter ME, Suratt BT. Crosstalk between CXCR4/stromal derived factor-1 and VLA-4/VCAM-1 pathways regulates neutrophil retention in the bone marrow. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):604–612. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leleu X, Jia X, Runnels J, et al. The Akt pathway regulates survival and homing in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2007;110(13):4417–4426. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiménez C, Sebastián E, Chillón MC, et al. MYD88 L265P is a marker highly characteristic of, but not restricted to, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Leukemia. 2013;27(8):1722–1728. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seemann S, Lupp A. Administration of a CXCL12 analog in endotoxemia is associated with anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and cytoprotective effects in vivo. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fan H, Wong D, Ashton SH, Borg KT, Halushka PV, Cook JA. Beneficial effect of a CXCR4 agonist in murine models of systemic inflammation. Inflammation. 2012;35(1):130–137. doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9297-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Triantafilou M, Lepper PM, Briault CD, et al. Chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) is part of the lipopolysaccharide “sensing apparatus”. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(1):192–203. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi K, Hernandez LD, Galán JE, Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. IRAK-M is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. 2002;110(2):191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou H, Yu M, Fukuda K, et al. IRAK-M mediates Toll-like receptor/IL-1R-induced NFκB activation and cytokine production. EMBO J. 2013;32(4):583–596. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang C-K, Yang C-Y, Jeng Y-M, et al. Autocrine/paracrine mechanism of interleukin-17B receptor promotes breast tumorigenesis through NF-κB-mediated antiapoptotic pathway. Oncogene. 2014;33(23):2968–2977. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rudelius M, Rauert-Wunderlich H, Hartmann E, et al. The G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER-1) contributes to the proliferation and survival of mantle cell lymphoma cells. Haematologica. 2015;100(11):e458–e461. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.127399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liang H, Chen Q, Coles AH, et al. Wnt5a inhibits B cell proliferation and functions as a tumor suppressor in hematopoietic tissue. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(5):349–360. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moniz S, Veríssimo F, Matos P, et al. Protein kinase WNK2 inhibits cell proliferation by negatively modulating the activation of MEK1/ERK1/2 [published correction appears in Oncogene. 2008;27(1):155]. Oncogene. 2007;26(41):6071–6081. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deng Q, Huang S. PRDM5 is silenced in human cancers and has growth suppressive activities. Oncogene. 2004;23(28):4903–4910. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi Z, Park HR, Du Y, et al. Cables1 complex couples survival signaling to the cell death machinery. Cancer Res. 2015;75(1):147–158. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu H, Jin W, Sun J, et al. New tumor suppressor CXXC finger protein 4 inactivates mitogen activated protein kinase signaling. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(18):3322–3326. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Borriello A, Caldarelli I, Bencivenga D, et al. p57(Kip2) and cancer: time for a critical appraisal. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9(10):1269–1284. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Décaillot FM, Kazmi MA, Lin Y, Ray-Saha S, Sakmar TP, Sachdev P. CXCR7/CXCR4 heterodimer constitutively recruits beta-arrestin to enhance cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(37):32188–32197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luu VP, Hevezi P, Vences-Catalan F, et al. TSPAN33 is a novel marker of activated and malignant B cells. Clin Immunol. 2013;149(3):388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brock C, Schaefer M, Reusch HP, et al. Roles of G beta gamma in membrane recruitment and activation of p110 gamma/p101 phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma. J Cell Biol. 2003;160(1):89–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Y-W, Staal B, Su Y, et al. Evidence that MIG-6 is a tumor-suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2007;26(2):269–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berthebaud M, Rivière C, Jarrier P, et al. RGS16 is a negative regulator of SDF-1-CXCR4 signaling in megakaryocytes. Blood. 2005;106(9):2962–2968. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lang R, Hammer M, Mages J. DUSP meet immunology: dual specificity MAPK phosphatases in control of the inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2006;177(11):7497–7504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang JQ, Jeelall YS, Beutler B, Horikawa K, Goodnow CC. Consequences of the recurrent MYD88(L265P) somatic mutation for B cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2014;211(3):413–426. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cao Y, Yang G, Hunter ZR, et al. The BCL2 antagonist ABT-199 triggers apoptosis, and augments ibrutinib and idelalisib mediated cytotoxicity in CXCR4 Wild-type and CXCR4 WHIM mutated Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia cells. Br J Haematol. 2015;170(1):134–138. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ogmundsdóttir HM, Sveinsdóttir S, Sigfússon A, Skaftadóttir I, Jónasson JG, Agnarsson BA. Enhanced B cell survival in familial macroglobulinaemia is associated with increased expression of Bcl-2. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117(2):252–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tripodo C, Gri G, Piccaluga PP, et al. Mast cells and Th17 cells contribute to the lymphoma-associated pro-inflammatory microenvironment of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(2):792–802. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tournilhac O, Santos DD, Xu L, et al. Mast cells in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia support lymphoplasmacytic cell growth through CD154/CD40 signaling. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(8):1275–1282. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]