To the editor:

Here we present a case of a patient with JAK2V617F- and IDH2-mutation–positive myelofibrosis (MF) with elevated blasts on ruxolitinib therapy for 8 years with a complete hematologic, histomorphologic, cytogenetic, and molecular remission. MF is a rare Philadelphia chromosome–negative myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by debilitating symptoms, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and bone marrow fibrosis resulting in pancytopenia.1 Because of significant morbidity, too few patients are suitable candidates for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, the only potentially curative approach.2 The JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib rapidly improves disease-related symptoms, organomegaly, and quality of life and provides a survival benefit in many patients with symptomatic MF, as demonstrated in clinical trials leading to its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration.3-7 Recently, reports of improvements in bone marrow fibrosis and significant reductions in JAK2 allele burden have begun to emerge.8-10

A 62-year-old woman presented to our institution in July 2007 with profound fatigue and weakness, a 9-kg weight loss over 6 months, and symptomatic massive splenomegaly. She had been diagnosed with polycythemia vera at age 44 (in 1989) and treated with hydroxycarbamide and occasional phlebotomies. Physical examination revealed splenomegaly and hepatomegaly at 20 cm and 5 cm below left and right costal margins, respectively. Her Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status was 1. Blood counts showed leukocytosis of 30.6 × 109/L with a prominent left shift (85% neutrophils, 35% lymphocytes, 3% monocytes, 7% metamyelocytes, and 2% blasts), hemoglobin of 14.2 g/L, and a platelet count of 558 × 109/L with giant platelets. Peripheral blood smear revealed microcytosis (mean corpuscular volume = 75 fL), significant anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, polychromasia, tear drop-shaped red blood cells, and ovalocytosis. Serum chemistry showed elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (2487 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase (154 IU/L), and uric acid (8.3 mg/dL). A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular bone marrow with left-shifted granulopoiesis, markedly increased atypical megakaryocytes in clusters, and 10% blasts. A diffuse and dense increase in reticulin fibers with many intersections, without focal formation of collagen (MF-1) was present. Cytogenetic evaluation showed deletion of chromosome 20q (q11.2q13.3) in 5 of 20 metaphases; no BCR-ABL transcript was detected. The JAK2V617F allele burden, as assessed by the pyrosequencing method (analytical sensitivity of 5% to 10%) was 94.6%, which was later confirmed by next-generation sequencing (analytical sensitivity of 1%) at 97.5%. Next-generation sequencing also revealed an additional molecular abnormality, an IDH2 (R140Q) mutation, at an allele frequency of 31%. A diagnosis of post–polycythemia vera MF was confirmed according to International Working Group Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment diagnostic criteria11 and was assessed as high-risk disease per the International Prognostic Scoring System, with an expected survival of only 2 years.12 The presence of the IDH2 mutation and 10% blasts in the bone marrow, which are both negative prognostic factors,13 further complicated this patient’s chance for a meaningful survival.

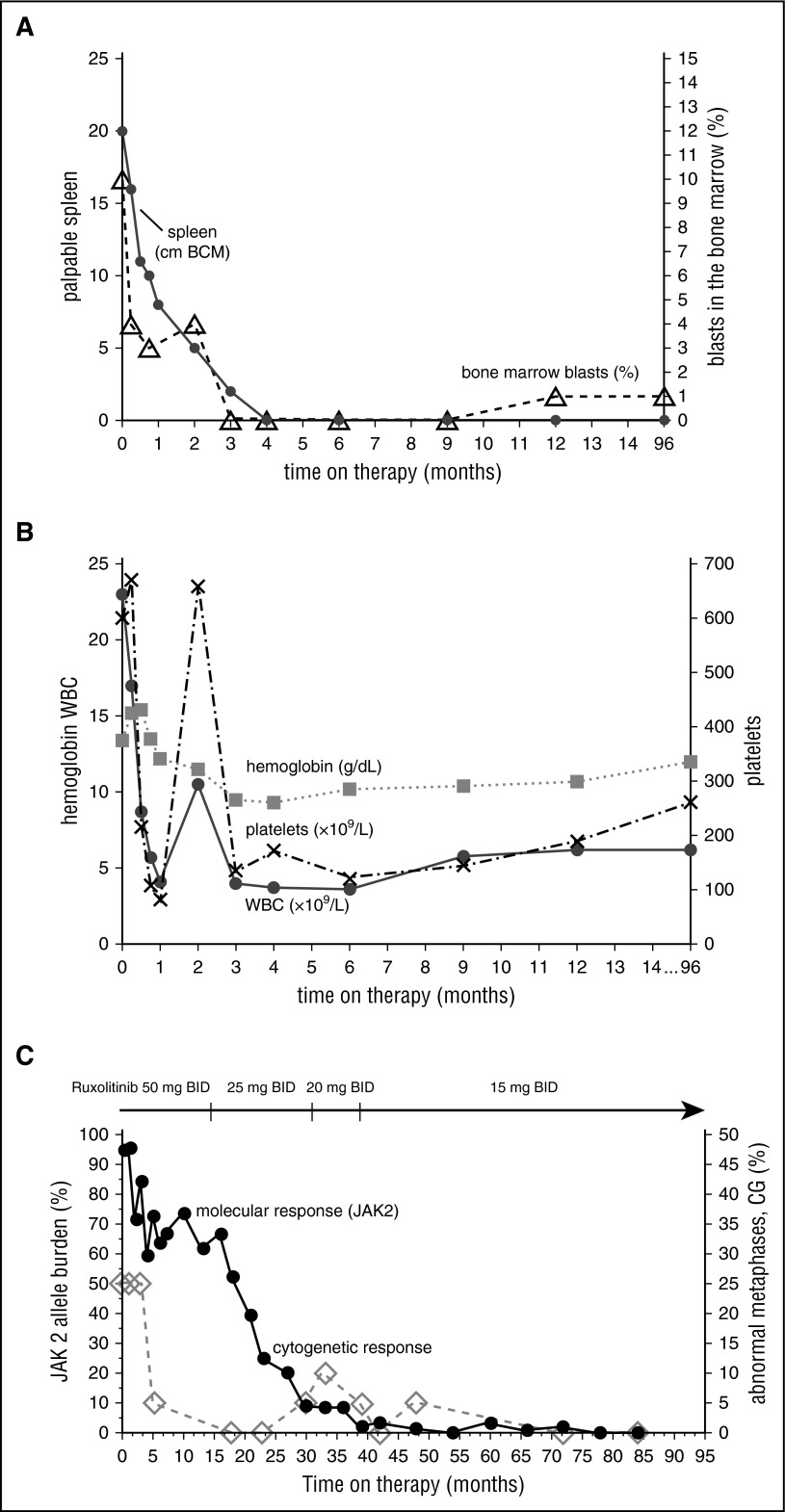

After signing informed consent, the patient was enrolled into a phase 1/2 clinical trial of ruxolitinib (www.clinicaltrial.gov, #NCT00509899) approved by the International Review Board at MD Anderson Cancer Center,3 with an initial starting dose of 50 mg twice daily. By the end of the first week, she experienced a marked improvement in all constitutional symptoms, which completely resolved by the third week, and >50% reduction in palpable spleen (Figure 1A). By week 24, her spleen was no longer palpable by physical examination. On day 34 of therapy, the patient developed grade 3 thrombocytopenia (platelets 49 × 109/L; Figure 1B). The therapy was held for 12 days as per protocol requirements; however, she was able to resume on the same dose owing to complete platelet recovery. Her hemoglobin levels gradually declined to a minimum of 9.3 g/dL at 3 months and recovered to 12 g/dL by the 16th month. The anemia was not symptomatic, and no transfusions were received. The dose was first reduced to 25 mg twice daily after 15 months on therapy for grade 1 anxiety, ankle swelling, and >23-kg weight gain, and later it was reduced to a final dose of 15 mg twice daily because of persistent anxiety. At 100 months from enrollment, the patient remained on a dose of 15 mg twice daily without any toxicity.

Figure 1.

Change in clinical parameters with time on ruxolitinib. Spleen and bone marrow (A), hematologic (B), and molecular and cytogenetic (C) responses over time.

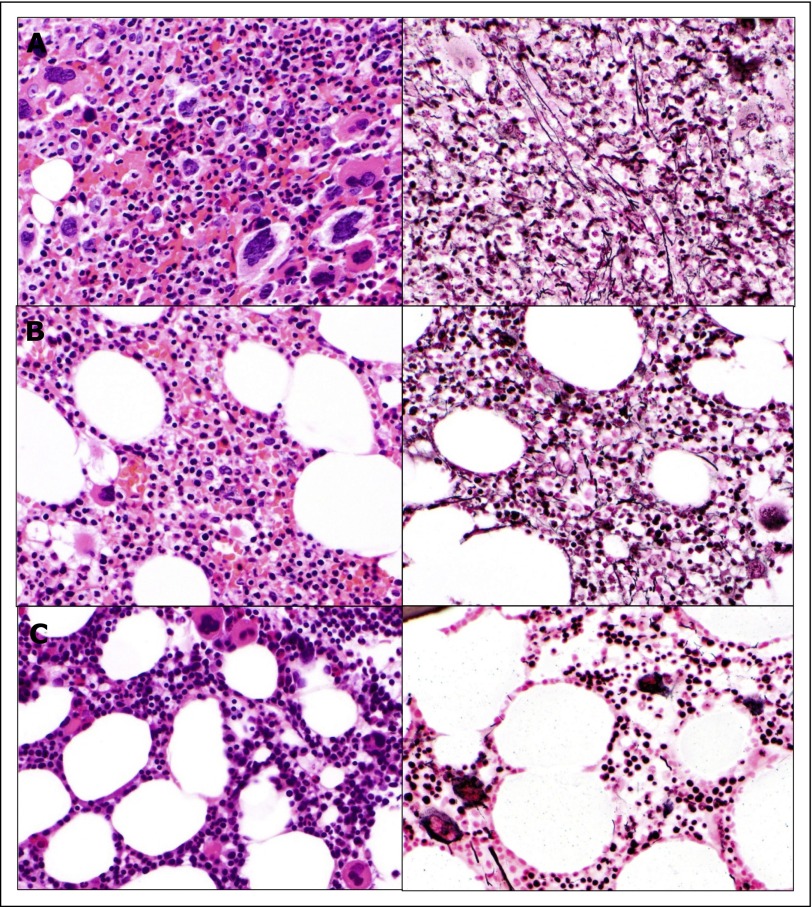

Rapid clinical improvement was followed by a complete hematologic remission within first 12 months, characterized by resolution of leukocytosis by the first month, disappearance of peripheral blasts by the second month, and normalization of peripheral blood smear by the 12th month. The JAK2 allele burden decreased steadily with time and remained undetectable after 77 months on therapy along with the IDH2 mutation, which was also undetectable (complete molecular response) (Figure 1C). Deletion 20q was repeatedly detected along with trisomy 8, which was acquired at a later time point; however, after 72 months, only a normal diploid karyotype was present. Bone marrow improvement was slowly observed over time (Figure 2). At the pretrial assessment (Figure 2A), a 100% cellular bone marrow contained hyperplastic, clustered megakaryocytes with abnormal chromatin clumping and hyperchromatic nuclei, and diffuse, dense reticulin fibrosis with many intersections. After 24 months of therapy (Figure 2B), the bone marrow cellularity had returned to normal (40%) with some features of dyshemopoiesis and occasional atypical megakaryocytes. No blasts were detected, and the reticulin fibers were less prominent, though still present as patches of dense reticulin. After 88 months on therapy (Figure 2C), the bone marrow remained normocellular, with all cells showing normal morphology, restored trilineage hemopoiesis, and complete disappearance of the reticulin fiber patterns (MF-0), confirming a complete bone marrow remission. Hematopoiesis was polyclonal, as assessed by the human androgen receptor X-chromosome inactivation assay (supplemental Figure 1).14

Figure 2.

Histomorphologic assessment of bone marrow core biopsy samples. (A) Bone marrow before therapy. Bone marrow after 24 months (B) and after 88 months (C) on therapy. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, original magnification ×500.

Phase 3 clinical trials and their long-term follow-up have shown that ruxolitinib elicits marked and durable clinical responses and extends survival in patients with MF, regardless of molecular or histomorphologic response.6,7 However, recent meta-analyses of these studies shows that significant reductions and even complete molecular response, as well as improvement in bone marrow fibrosis, are possible with prolonged treatment.8,9,15 It has been suggested that such deep responses may have prognostic significance and could delay disease progression. IDH2 mutations are subclonal mutations found in ∼4% of patients with MF that are correlated with an increased risk of leukemic transformation and shorter leukemia-free survival.13,16,17 Our report suggests that, in selected patients, ruxolitinib may be capable of affecting not only JAK2V617F clones but also IDH2 mutant clones, as well as cells with cytogenetic abnormalities.

How long the complete response can be maintained or whether a complete response can be maintained if therapy is withdrawn are questions we should begin to address as more MF patients achieve complete remission with ruxolitinib.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health through the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672.

Contribution: L.M., S.V., W.W., and H.K. participated in the patient’s care and wrote the manuscript; W.W. performed all pathology analyses; L.M., S.V., and K.J.N. wrote the manuscript; and all authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.V. receives research funding from Incyte Corporation. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Srdan Verstovsek, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Unit 428, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: sverstov@mdanderson.org.

References

- 1.Mesa RA, Niblack J, Wadleigh M, et al. The burden of fatigue and quality of life in myeloproliferative disorders (MPDs): an international Internet-based survey of 1179 MPD patients. Cancer. 2007;109(1):68–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballen KK, Shrestha S, Sobocinski KA, et al. Outcome of transplantation for myelofibrosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(3):358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verstovsek S, Kantarjian H, Mesa RA, et al. Safety and efficacy of INCB018424, a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1117–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison C, Kiladjian JJ, Al-Ali HK, et al. JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):787–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Passamonti F, Maffioli M, Cervantes F, et al. Impact of ruxolitinib on the natural history of primary myelofibrosis: a comparison of the DIPSS and the COMFORT-2 cohorts. Blood. 2014;123(12):1833–1835. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-544411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. COMFORT-I investigators. Efficacy, safety, and survival with ruxolitinib in patients with myelofibrosis: results of a median 3-year follow-up of COMFORT-I. Haematologica. 2015;100(4):479–488. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.115840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deininger M, Radich J, Burn TC, Huber R, Paranagama D, Verstovsek S. The effect of long-term ruxolitinib treatment on JAK2p.V617F allele burden in patients with myelofibrosis. Blood. 2015;126(13):1551–1554. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-635235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kvasnicka HM, Thiele J, Bueso-Ramos CE, et al. Effects of five-years of ruxolitinib therapy on bone marrow morphology in patients with myelofibrosis and comparison with best available therapy [abstract]. Blood. 2013;122(21) Abstract 4055. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pieri L, Pancrazzi A, Pacilli A, et al. JAK2V617F complete molecular remission in polycythemia vera/essential thrombocythemia patients treated with ruxolitinib. Blood. 2015;125(21):3352–3353. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-624536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barosi G, Mesa RA, Thiele J, et al. International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) Proposed criteria for the diagnosis of post-polycythemia vera and post-essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis: a consensus statement from the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. Leukemia. 2008;22(2):437–438. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cervantes F, Dupriez B, Pereira A, et al. New prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis based on a study of the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. Blood. 2009;113(13):2895–2901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vannucchi AM, Lasho TL, Guglielmelli P, et al. Mutations and prognosis in primary myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1861–1869. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boudewijns M, van Dongen JJM, Langerak AW. The human androgen receptor X-chromosome inactivation assay for clonality diagnostics of natural killer cell proliferations. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9(3):337–344. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kvasnicka HM, Thiele J, Bueso-Ramos C, et al. Exploratory analysis of the effect of ruxolitinib on bone marrow morphology in patients with myelofibrosis [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl) Abstract 7030. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutation studies in 1473 patients with chronic-, fibrotic- or blast-phase essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera or myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2010;24(7):1302–1309. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tefferi A, Jimma T, Sulai NH, et al. IDH mutations in primary myelofibrosis predict leukemic transformation and shortened survival: clinical evidence for leukemogenic collaboration with JAK2V617F. Leukemia. 2012;26(3):475–480. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]