SUMMARY

In cancer genomics, recurrence of mutations in independent tumor samples is a strong indicator of functional impact. However, rare functional mutations can escape detection by recurrence analysis owing to lack of statistical power. We enhance statistical power by extending the notion of recurrence of mutations from single genes to gene families that share homologous protein domains. Domain mutation analysis also sharpens the functional interpretation of the impact of mutations, as domains more succinctly embody function than entire genes. By mapping mutations in 22 different tumor types to equivalent positions in multiple sequence alignments of domains, we confirm well-known functional mutation hotspots; identify uncharacterized rare variants in one gene that are equivalent to well-characterized mutations in another gene; detect previously unknown mutation hotspots; and provide hypotheses about molecular mechanisms and downstream effects of domain mutations. With the rapid expansion of cancer genomics projects, protein domain hotspot analysis will likely provide many more leads linking mutations in proteins to the cancer phenotype.

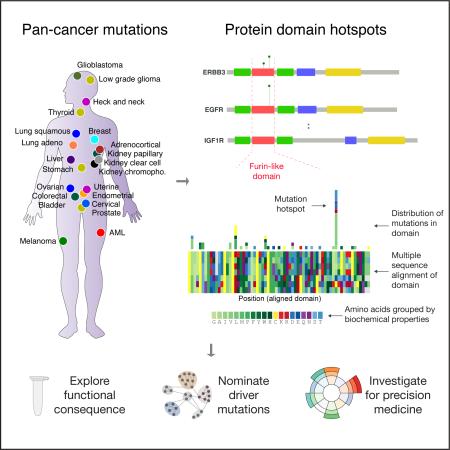

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The landscape of somatic mutations in cancer is extraordinarily complex, making it difficult to distinguish oncogenic alterations from passenger mutations. Many approaches use the recurrence of alterations in a single gene across tumor samples to identify potential driver genes. However, the molecular functions of genes are often pleiotropic, and in many cases it may not be a gene as an entity itself, but rather the specific function of a gene or a set of genes that is under selective pressure in cancer. For example, in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the transmembrane signaling receptor NOTCH1 is activated by mutations in the heterodimerization and the PEST domains (Weng et al., 2004), while in squamous cell carcinomas, notch-signaling has a tumor suppressive role and notch receptors (NOTCH1-4) are inactivated by mutations in the ligand binding EGF-like domains (Wang et al., 2011). Thus, an alternative approach to assessing the relevance of somatic alterations is to determine the recurrence of mutations in genes involved in similar molecular functions. One powerful method for systematically assessing common biological function of genes is through the analysis of protein domains, which are evolutionarily conserved, structurally related functional units encoded in the protein sequence of genes (Holm and Sander, 1996; Chothia et al., 2003). By coupling the observation of mutations across genes in a domain family together, it may be possible to identify additional functional alterations that confer a selective, functional advantage to cancer cells and learn more about the details of pathway organization downstream of activated domains.

Large cross-institutional projects, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), have recently profiled the major human cancer types genomically, including glioblastoma (McLendon et al., 2008), lung (Hammerman et al., 2012; Ding et al., 2008), ovarian (Bell et al., 2011), breast (Koboldt et al., 2012), endometrial (Getz et al., 2013), kidney (Creighton et al., 2013) and colorectal cancer (Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2012). Through whole-exome sequencing of tumor-normal pairs, these and other studies have provided catalogues of somatically mutated genes that are frequently altered and therefore likely associated with disease development. However, despite a collection of mutation data from nearly 5,000 samples encompassing 21 tumor types, the results from a recent pan-cancer study illustrate that by using recurrence of mutations in genes, thousands of samples per tumor type are needed to confidently identify genes that are mutated at low but clinically relevant frequencies (2-5%) (Lawrence et al., 2014a).

Several analytical approaches have been developed to detect genes associated with oncogenesis (Gonzalez-Perez and Lopez-Bigas, 2012; Dees et al., 2012; Lawrence et al., 2014b). One of these widely applied algorithms, MutSigCV, compares the gene-specific mutation burden to a background model using silent mutations in the gene and gene neighborhood as well as contextual information (DNA replication timing and general level of transcriptional activity) to estimate the probability that the gene is significantly mutated (Lohr et al., 2012; Lawrence et al., 2014b). Additional approaches have been developed to predict the functional impact of specific amino acid changes. These approaches generally rely on analyzing physico-chemical properties of amino acid substitutions (e.g., changes in size and polarity), structural information (e.g., hydrophobic propensity and surface accessibility), and the evolutionary conservation of the mutated residues across a set of related genes (Reva et al., 2011; Yue et al., 2006; Bromberg et al., 2008; Ng, 2003; Adzhubei et al., 2010). Other approaches analyze mutations across sets of functionally related genes to test for a possible enrichment of mutation events in signaling pathways (Cerami et al., 2010; Ciriello et al., 2012; Hofree et al., 2013; Torkamani and Schork, 2009) or investigate how alterations/modifications alter protein–protein or protein–nucleic interactions (Betts et al., 2015) as well as phosphorylation-dependent signaling motifs (Reimand and Bader, 2013; Reimand et al., 2013).

Protein domains represent particular sequence variants that have been formed over evolution by duplication and/or recombination (Holm and Sander, 1996; Chothia et al., 2003). Domains often encode structural units associated with specific cellular tasks, and large proteins with multiple domains can have several molecular functions each exerted by a specific domain. The structure-function relationship encoded in domains has been used as a tool for understanding the effect of mutations across functionally related genes. For example, some of the most frequent oncogenic mutations in human cancer affect analogous residues of the activation segment of the kinase domain and cause constitutive activation of several oncogenes, including FLT3 D835 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia, KIT D816 mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and BRAF V600 mutations in melanoma (Dibb et al., 2004; Greenman et al., 2007). Proteome-wide bioinformatics analysis of mutations in domains have been performed to identify domains enriched for alterations (Nehrt et al., 2012; Peterson et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2015) as well as to detect significantly mutated domain hotspots using multiple sequence analysis (Peterson et al., 2010; Yue et al., 2010). We here extend upon these analyses by performing a systematic pan-cancer analysis of recurrence of mutations in protein domains (hotspots and enrichment of mutations across the domain body) and identify dozes of unreported cancer-associated mutations that are not detection using standard gene-based approaches.

Here, we performed a systematic and comprehensive analysis of mutations in protein domains using data from more than 5,000 tumor-normal pairs from 22 cancer types profiled by the TCGA consortium and domains from the protein family database Pfam-A (Punta et al., 2011). Using multiple sequence analysis, we determined if conserved residues in protein domains were affected by mutations across related genes and identified many putative “domain hotspots”. We further exposed rare mutations that associated with well-characterized oncogenic mutations, including the furin-like domain where uncharacterized mutations in ERBB4 (S303F) are analogous to known oncogenic mutations in the same domain of ERRB2 (S310F), suggesting similar functional consequences. In several cases, we associated rare mutations in potential cancer genes with therapeutically actionable hotspots in known oncogenes, underlining the potential clinical implications of our findings.

RESULTS

Mapping somatic mutations to protein domains

To systematically analyze somatic mutations in the context of conserved protein domains, we retrieved whole-exome sequencing data from 5496 tumor-normal pairs of 22 different tumor types profiled by the TCGA consortium. To obtain a uniform data set of mutation calls, annotation of somatic mutations were based on the publicly available data (Oct 2014) from the cBioPortal for cancer genomics data (Cerami et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013) (Fig. 1). After filtering out ultra-mutated samples and mutations in genes with low mRNA expression levels (Supplemental Experimental Procedures), the data consisted of a total of 727,567 mutations in coding regions with 463,842 missense, 192,518 silent, and 71,207 truncating or small in-frame mutations. Focusing on missense mutations, we observed that the relative proportion of amino acids affected by mutations varied considerably between cancer types (Supplementary Fig. 1A). These amino acid mutation biases are due to a combination of variations in the codon usage between different amino acids and the variations in the base-pair transitions and transversions observed between different cancer types (Lawrence et al., 2014b; Alexandrov et al., 2013). Because of the high mutation rate of CG dinucleotides across all cancers, arginine (R) is the most frequently altered amino acid despite being the ninth most common amino acid as CG dinucleotides are present in four out of six of arginine's codons (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

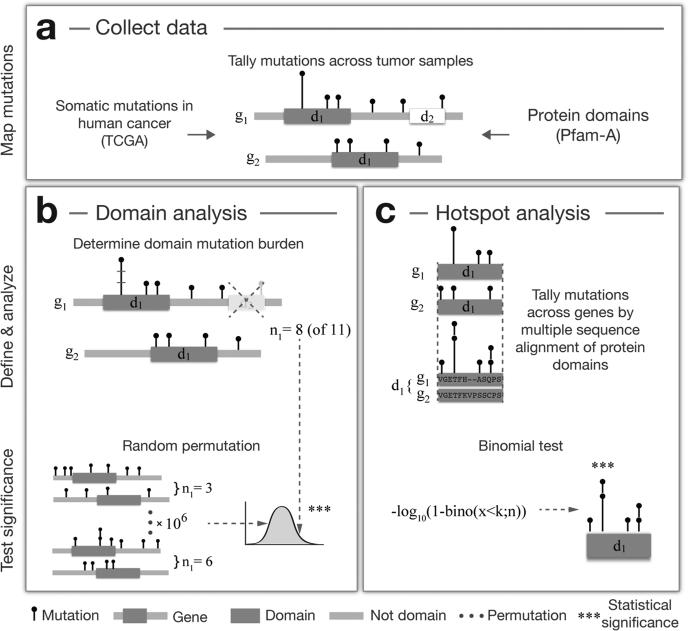

Figure 1. Work flow for analyzing recurrently mutated protein domains in cancer.

(A) Missense mutation data from recent genomic profiling projects of human cancers (TCGA) are collected and all mutations are tallied across tumor samples and cancer types. Mutations are mapped to protein domains obtained from the Pfam-A database, which contains a manually curated set of highly conserved domain families in the human proteome. Two separate analyses are performed on this data to (B) identify domains enriched for missense mutations and (C) to detect mutation hotspots in domains through multiple sequence alignment. In the first analysis (B), the observed mutation burden (n1) of a specific domain (d1) is calculated by counting the total number of mutations in all domain-containing genes (g1&g2). Mutations in other domains (e.g., d2) are excluded. A permutation test is applied to determine if the observed mutation burden (n1 = 8) is larger than expected by chance. Mutations are randomly shuffled 106 times across each gene separately and the observed mutation count is compared to the distribution of randomly estimated mutation counts. In the second analysis (C), domains are aligned across related genes by multiple sequence alignment and mutations are tallied at each residue of the alignment. A binomial test is applied to determine if the number of mutations at a specific residue is significantly different than the number of mutations observed at other residues of the alignment.

We next mapped the mutations to conserved protein domains obtained from the database of protein domain families, Pfam-A version 26.0 (Punta et al., 2011) (Fig. 1A). Overall, 4401 of 4758 unique Pfam domains in the human genome were mutated at least once across all samples. The fraction of missense mutations that map to domains (46.7%, 216,676 of 463,842) was consistent across samples and tumor types and was similar to the proportion of the proteome assigned as conserved domains (45.4%, Supplementary Fig. 1A).

Identification of domains with enriched mutation burden

Our first aim was to identify domains that display an increased mutation burden. We defined the domain mutation burden as the total number of missense mutations in a domain, excluding domains only present in only one gene. After tallying mutations across samples, the domain with the highest mutation burden was the protein kinase domain with 7203 mutations in 353 genes (not including genes with tyrosine kinase domains), while the P53 domain present in TP53, TP63, and TP73 had the most mutations when normalizing for the domain length and the size of the domain family. To systematically investigate if the mutation burden for a given domain was larger than would be expected by chance, we performed a permutation test that takes into account the number of mutations within and outside of the domain, the domain length, and the length and number of genes in the domain family. To specifically compare domain versus non-domain areas, we excluded other domains present in the domain-containing gene family. Assuming that each mutation is an independent event and that all residues of the protein have an equal chance of being mutated, we randomly reassigned all mutations 106 times across each gene separately and calculated if the observed domain mutation burden was significantly different from the distribution of burdens observed by chance (Fig. 1B).

Using this permutation approach, we identified 14 domains that were significantly enriched for missense mutations within the domain boundaries compared to other areas of the same genes (p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected, Fig. 2 and Table 1). As both the number of gene members per domain (domain family) and the number of mutations per gene varies greatly, we wanted to distinguish between two cases: 1) only a single or a few genes in the domain family contributed to the domain mutation burden, and 2) genes contributed more evenly to the mutations in the domain. We were particularly interested in the latter as mutations in domains contributed by many infrequently mutated genes may represent new functional alterations that would not have been discovered using traditional gene-by-gene approaches. To investigate this, we calculated an entropy score (S̄) that was normalized to the size of the domain family, so a low score indicates that the mutation burden is unevenly distributed between domain-containing genes and a high score indicates that the mutation burden is distributed evenly among the genes in the domain family (Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

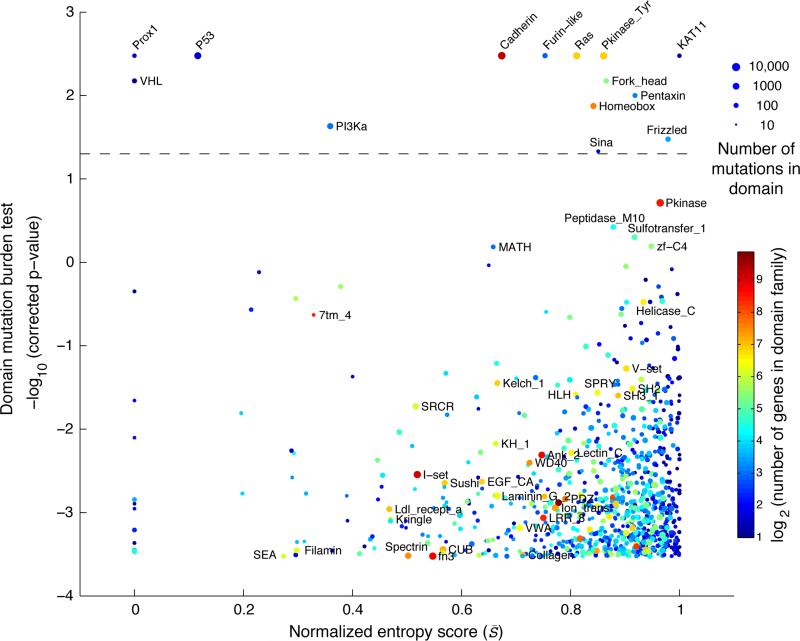

Figure 2. Identification of protein domains enriched for missense mutations.

The estimated significance level of the domain mutation burden test is plotted against the domain entropy score (S̄). The domain mutation burden test captures the enrichment of mutations within the domain boundaries compared to non-domain areas of the same genes. The entropy score captures the degree to which individual or multiple genes contribute to the mutations in the domain, where low and high scores indicate that the mutation burden is unevenly or evenly distributed between domain-containing genes, respectively. S̄ is normalized to the highest possible score so that when S̄ = 1 all genes are evenly mutated and when S̄ = 0 then only one gene is mutated. Domains with a significant mutation burden are indicated above the dashed line (p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected). The sizes of the dots reflect the number of mutations in each domain. Domains are color coded by the number of genes in the domain family.

Table 1. Protein domains significantly enriched for mutations.

Domains are listed by their Pfam domain identifiers, the number of genes in the domain family, the Bonferroni-corrected p-value, the entropy score (S̄) the number of mutations in the domain, the mutation enrichment score (ed ) expressed as the ratio of the observed number of domain mutations to the expected number of domain mutations, the genes with the most domain mutations, and the two cancers with most domain mutations. Genes are in italic font if they were reported to be significantly mutated in a recent pan-cancer study (Lawrence et al., 2014a) and bold font if not. The list is sorted by p-value followed by entropy score.

| Row | Domain | Genes (#) | p-val (−log10) | S̄ | Mutations (#) | ed | Top Genes (Gene symbol and # of mutations) | Top Cancers (Cancer and # of mutations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KAT11 | 2 | 2.48 | 1 | 65 | 1.94 | CREBBP 33; EP300 32; | HNSC 14; BLCA 10; |

| 2 | Pkinase_Tyr | 120 | 2.48 | 0.861 | 2059 | 1.17 | BRAF 427; EGFR 50; ERBB2 43; | SKCM 428; THCA 246; |

| 3 | Ras | 124 | 2.48 | 0.811 | 1369 | 1.08 | KRAS 269; NRAS 177; HRAS 46; | SKCM 206; COADREAD 166; |

| 4 | Furin-like | 7 | 2.48 | 0.753 | 147 | 1.77 | EGFR 67; ERBB3 30; ERBB2 23; | GBM 42; LGG 14; |

| 5 | Cadherin | 614 | 2.48 | 0.674 | 3358 | 1.06 | FAT4 214; FAT3 184; FAT1 116; | SKCM 607; LUAD 474; |

| 6 | P53 | 3 | 2.48 | 0.116 | 1333 | 1.63 | TP53 1301; TP63 23; TP73 9; | OV 182; BRCA 171; |

| 7 | Prox1 | 3 | 2.48 | 0 | 56 | 1.05 | PROX1 56; PROX2 0; | HNSC 13; SKCM 11; |

| 8 | Fork_head | 42 | 2.18 | 0.866 | 165 | 1.4 | FOXA1 25; FOXA2 10; FOXK2 10; | BRCA 22; SKCM 18; |

| 9 | VHL | 2 | 2.18 | 0 | 103 | 1.24 | VHL 103; VHLL 0; | KIRC 95; SKCM 2; |

| 10 | Pentaxin | 9 | 2 | 0.918 | 99 | 1.42 | NPTX2 22; SVEP1 17; NPTXR 16; | SKCM 23; HNSC 13; |

| 11 | Homeobox | 190 | 1.87 | 0.842 | 375 | 1.23 | ZFHX4 28; NKX3-1 11; ONECUT2 11; | SKCM 48; UCEC 44; |

| 12 | PI3Ka | 8 | 1.63 | 0.359 | 356 | 1.21 | PIK3CA 296; PIK3CG 20; PIK3CB 13; | BRCA 126; UCEC 44; |

| 13 | Frizzled | 11 | 1.48 | 0.979 | 164 | 1.21 | FZD10 24; FZD9 20; FZD3 19; | BRCA 18; LUAD 18; |

| 14 | Sina | 3 | 1.33 | 0.851 | 31 | 1.43 | SIAH2 16; SIAH1 12; SIAH3 3; | UCEC 5; COADREAD 4; |

As expected, we found that the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) and the P53 domains were significantly enriched for mutations and had low entropy scores as they were dominated by mutations in the canonical tumor suppressor genes VHL and TP53, respectively (Fig. 2 and Table 1, row 6 and 9). On the other end of the spectrum, the KAT11 domain encoding the lysine acetyltransferase (KAT) activity of CREBBP and EP300 was significantly mutated and had a high normalized entropy score with around 30 mutations in each gene (Table 1, row 1). CREBBP and EP300 are transcriptional co-activators that regulate gene expression through acetylation of lysine residues of histones and other transcription factors (Liu et al., 2008). In our analysis, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC) was the tumor type with most mutations in KAT11 and nearly half fell in the domain (14 of 29) that spans only about 4% of the length of both CREBBP and EP300 (Supplementary Fig. 2). One the two genes (EP300) has previously been reported as significantly altered in HNSC (Lawrence et al., 2014a). Supporting the enrichment of mutations in the KAT11 domain, inactivating mutations in KAT11 have been associated with oncogenesis in tumor types not part of this analysis, including B-cell lymphoma (Pasqualucci et al., 2012; Cerchietti et al., 2010; Morin et al., 2012) and small-cell lung cancer (Peifer et al., 2012). In small-cell lung cancer, CREBBP and EP300 were reported to be deleted in a mutually exclusive fashion (Peifer et al., 2012), which often indicates that genes are functionally linked (Ciriello et al., 2012).

Confirming canonical mutation events in cancer, we found mutations clustering in domains of genes involved in receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) signaling, including the tyrosine kinase domain itself (Pkinase Tyr), the furin-like domain involved in RTK aggregation, and downstream signaling through genes with the ras GTPase domain and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3Ka) domain (Table 1, row 2, 3, 4 and 12). These domains have also been reported in other systematic studies of mutations in domains (Yue et al., 2010; Nehrt et al., 2012), consistent with the fact that the RTK signaling pathways are often high-jacked in cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). In a similar manner, we identified multiple domains in genes that have previously been associated with cancer, including the DNA-binding forkhead domain in Fox family transcription factors and the frizzled domain in G protein-coupled receptors of the Wnt signaling pathway. Interestingly, these domains have high entropy scores with a substantial amount of mutations contributed by genes not reported as altered in a recent pan-cancer study (Lawrence et al., 2014a) (see color code in Table 1, row 8 and 13). Thus, from the perspective of the structure-function relationship encoded in domains, these are candidate cancer driver genes due to the enrichment of mutations in these functional regions.

We also identified several domain families in which most of the genes had no apparent link to cancer. Such domains include the homeobox domain involved in DNA-binding and the cadherin domain involved in cell adhesion (Table 1, rows 5 and 11). As cell-cell adhesion and DNA-binding are critical cellular processes, it is plausible that domain-contained genes involved in these processes are under positive selective pressure in the cancer environment, although it remains to be tested if mutations in these domains are functionally disruptive and may play a critical role in cancer. Several additional domains were found to be enriched for mutations and may potentially be of interest in a cancer context (Table 1).

Protein domain alignment reveals mutation hotspots across related genes

We next aligned each domain using multiple sequence alignment and tallied mutations across analogous residues of domain-containing genes (Fig. 1C). The goals of this analysis were to identify new domain hotspots with recurrent mutations across functionally related genes and to associate hotspots in well-established cancer genes with rare events in genes not previously linked to cancer. We used a binomial test to determine if a mutation peak at a specific residue was significantly different from other residues in the domain alignment, and we applied the same entropy analysis to investigate the degree to which individual or multiple genes contributed mutations to each hotspot. Based on Bonferroni-corrected p-value (p < 0.05), we identified 82 significant hotspots in 42 different domains (Supplementary Table 1) with the subset of hotspots detected in mutations in at least two genes presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Identified mutation hotspots in protein domains.

The detected domain hotspots are listed by their Pfam domain identifiers, the number of genes in the domain family, the position of the hotspot in the domain alignment, the Bonferroni-corrected p-values, the entropy score (S̄), the number of mutations in the hotspot, the two genes with the most mutations in the hotspot, and the cancer type with most mutations in the hotspot. Genes are in italic font if they were reported to be significantly mutated in a recent pan-cancer study (Lawrence et al., 2014a) and bold font if not. The list is sorted by p-value followed by entropy score. Hotspots in domains where only one gene was mutated (S̄ = 0) were excluded. All significant domain hotspots (82) are provided in (Supplementary Table S1)

| Row | Domain | Genes (#) | Position | pValue (−log10) | S̄ | Mut (#) | Top Gene 1 (# mut, gene, site) | Top Gene 2 (# mut, gene, site) | Top Cancer (# mut, cancer) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KAT11 | 2 | 94 | 10 | 0.88 | 10 | 7 EP300 D1399 | 3 CREBBP D1435 | 3 BLCA |

| 2 | Orn_DAP_Arg_deC | 3 | 86 | 10 | 0.28 | 11 | 10 AZIN1 S367 | 1 ODC1 R369 | 10 LIHC |

| 3 | Ras | 124 | 17 | 10 | 0.27 | 56 | 31 KRAS G13 | 11 NRAS G13 | 12 COADREAD |

| 4 | MH2 | 8 | 46 | 10 | 0.25 | 14 | 11 SMAD4 R361 | 3 SMAD3 R268 | 8 COADREAD |

| 5 | Furin-like | 7 | 119 | 10 | 0.20 | 30 | 27 EGFR A289 | 2 ERBB3 G284 | 23 GBM |

| 6 | PI3K_C2 | 7 | 130 | 10 | 0.19 | 17 | 15 PIK3CA E453 | 2 PIK3CB E470 | 7 BRCA |

| 7 | Ras | 124 | 88 | 10 | 0.18 | 189 | 142 NRAS Q61 | 22 HRAS Q61 | 78 SKCM |

| 8 | Iso_dh | 5 | 128 | 10 | 0.14 | 292 | 274 IDH1 R132 | 18 IDH2 R172 | 232 LGG |

| 9 | WD40 | 170 | 16 | 10 | 0.13 | 37 | 31 FBXW7 R465 | 2 FBXW7 Y545 | 12 COADREAD |

| 10 | Ras | 124 | 16 | 10 | 0.12 | 224 | 192 KRAS G12 | 17 NRAS G12 | 74 COADREAD |

| 11 | Pkinase_Tyr | 120 | 291 | 10 | 0.09 | 415 | 382 BRAF V600 | 14 FLT3 D835 | 235 THCA |

| 12 | Recep_L_domain | 14 | 52 | 10 | 0.08 | 17 | 16 ERBB3 V104 | 1 ERBB2 I101 | 5 COADREAD |

| 13 | P53 | 3 | 181 | 10 | 0.07 | 141 | 139 TP53 R273 | 2 TP63 R343 | 44 LGG |

| 14 | PI3Ka | 8 | 27 | 10 | 0.02 | 164 | 163 PIK3CA E545 | 1 PIK3CB E552 | 66 BRCA |

| 15 | Furin-like | 7 | 136 | 7.24 | 0.22 | 13 | 11 ERBB2 S310 | 2 ERBB4 S303 | 4 STAD |

| 16 | zf-H2C2_2 | 940 | 7 | 7.21 | 0.62 | 79 | 2 ZNF208 R613 | 2 ZNF286A R430 | 27 UCEC |

| 17 | P53 | 3 | 157 | 5.25 | 0.14 | 29 | 28 TP53 R249 | 1 TP63 R319 | 8 LIHC |

| 18 | RasGAP | 12 | 23 | 4.03 | 0.53 | 8 | 3 RASAL1 R342 | 2 NF1 R1276 | 2 HNSC |

| 19 | BicD | 2 | 570 | 3.3 | 0.97 | 5 | 3 BICD2 R635 | 2 BICD1 R633 | 2 SKCM |

| 20 | Pro_isomerase | 19 | 31 | 3.13 | 0.48 | 9 | 4 PPIAL4G R37 | 2 PPIG R41 | 7 SKCM |

| 21 | DUF3497 | 11 | 3 | 2.91 | 0.40 | 7 | 4 BAI3 R588 | 2 ELTD1 K132 | 4 SKCM |

| 22 | MT | 15 | 36 | 2.79 | 0.14 | 8 | 7 DNAH5 D3236 | 1 DNAH11 H3139 | 8 SKCM |

| 23 | Choline_transpo | 5 | 186 | 2.56 | 0.42 | 5 | 3 SLC44A1 R437 | 2 SLC44A4 R496 | 1 BRCA |

| 24 | bZIP_2 | 9 | 21 | 2.4 | 0.61 | 6 | 2 HLF R243 | 2 NFIL3 R91 | 2 UCEC |

| 25 | Fork_head | 42 | 88 | 2.4 | 0.46 | 11 | 3 FOXP1 R514 | 2 FOXJ1 R170 | 4 COADREAD |

To assess the power of the domain-based approach to identify mutations that would have been missed using a traditional gene-by-gene approach, we systematically compared the two approaches using the same data set and similar binomial statistics. Using the domain-based approach, we identifying an additional 68 mutations in genes that were not detected when analyzing genes individually, indicating that the domain-based analysis complements the gene-based (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2). Although previous studies have used multiple sequence analysis to discover hotspots in domains (Peterson et al., 2010; Yue et al., 2010), these studies were conducted before the recent wave of published cancer genomics studies, hindering a direct performance comparison due to extensive differences of data availability at the time of analysis. A recent report investigated mutations in domains using current cancer genomics data sets (Yang et al., 2015), however this analysis did not include multiple sequence alignment and hotspot detection across domain-containing genes making a direct comparison the methods infeasible.

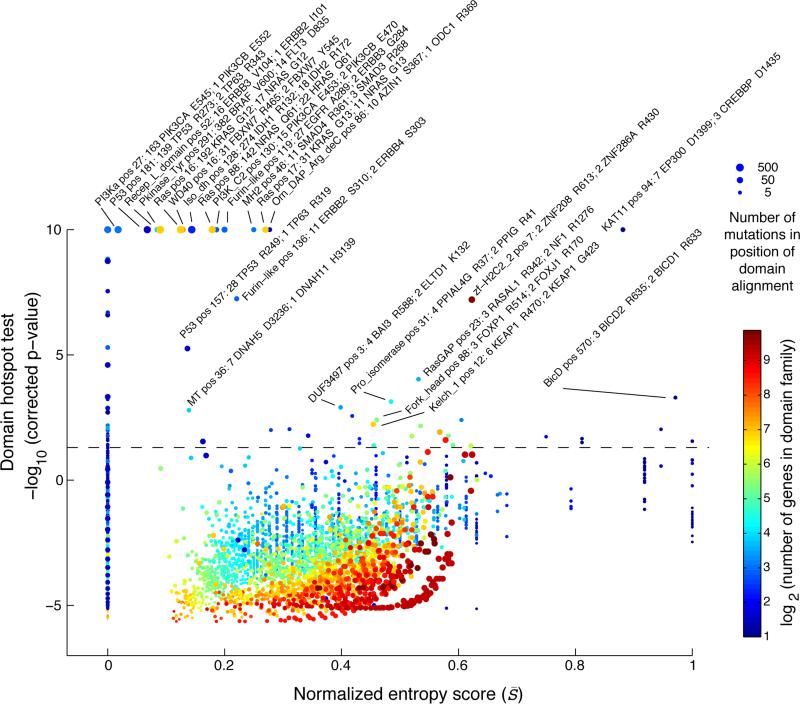

We recapitulated several well-known hotspots in domains where only one gene was mutated such as the P53 and PI3Ka domains with mutations in TP53 and PIKC3A, respectively (entropy≅0, Fig. 3 and Table 2, row 13, 14, and 17). We also confirmed several known domain-specific hotspots such as the isocitrate/isopropylmalate dehydrogenase domain (Iso_dh) with homologous mutations in IDH1 (position R132) and IDH2 (R172) as well as the ras domain with mutations in KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS at positions G12, G13, and Q61 in the GTP binding region (Table 2, row 3, 7, 8, and 10). Furthermore, we found that well-characterized hotspots in KIT D816 in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), FLT3 D835 in AML, and BRAF V600 in thyroid carcinoma and melanoma aligned perfectly in the conserved activation segment of the tyrosine kinase domain (Table 2, row 11). These mutations are known to cause constitutive kinase activity, which promotes cell proliferation independent of normal growth factor control (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011; Dibb et al., 2004). We further superimposed the crystal structures of the three proteins and found that the residues overlap in structure space (Supplementary Fig. 4), offering support that the alignment approach captures structurally relevant information. Notably, in the same domain hotspot many singleton mutations in lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma mapped to the equivalent position in other RTKs, including EPHA2 V763M, FGFR1 D647N, PDGFRA D842H, and three mutations in EGFR L861Q. Although these are rare events in lung cancer, this analysis reveals that they likely affect the same activation loop residue and may be therapeutically actionable in a similar manner as the hotspot mutations in KIT, FLT3, and BRAF.

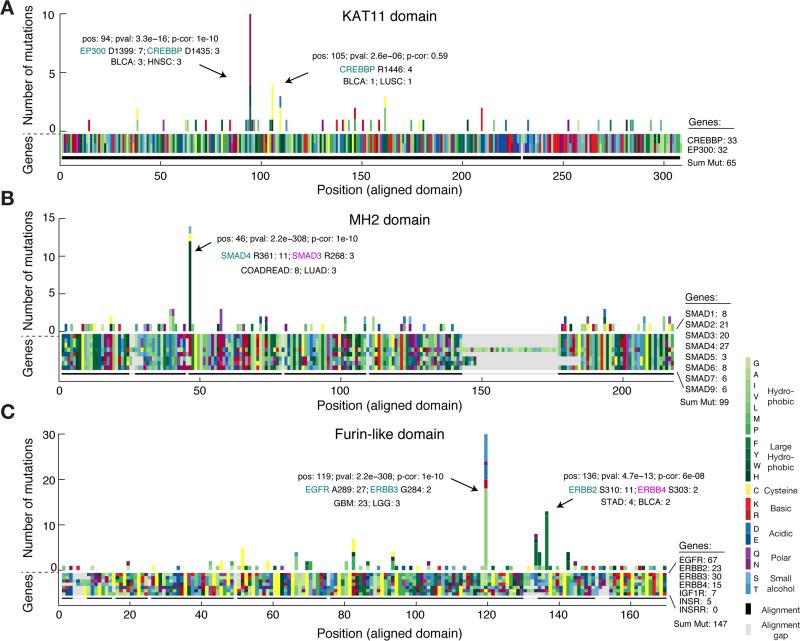

Figure 3. Domain alignment detects mutation hotspots across related genes.

The estimated significance level of each mutation hotspot in the domain alignment is plotted against the domain entropy score (S̄), which is described elsewhere. Significant hotspots are indicated above the dashed line (p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected). The maximal significance was set to 10 [−log10 (p-value)]. Hotspots are named by the Pfam identifiers followed by the position in the domain alignment and the number of mutations in the top two mutated genes. The size of the dots reflects the number of mutations at each residue and the dots are color coded by the number of domain-containing genes in the genome.

Similar to the previous analysis of entropy in recurrently mutated domains, we were interested in domain hotspots with high entropy scores. Again, the lysine acetylase domain, KAT11, was identified with high entropy for a significant hotspot at position 94 of the domain alignment with mutations in EP300 at D1399 and CREBBP at D1435 (Table 2, row 1). These sites are located in the substrate binding loop of KAT11 and mutations in these residues affect the structural conformation of the substrate binding loop (Liu et al., 2008). Recently, both genes have been implicated in other cancers not analyzed here such as small-cell lung cancer (Peifer et al., 2012) and B-cell lymphoma (Pasqualucci et al., 2012; Cerchietti et al., 2010; Morin et al., 2012). Confirming the functional relevance of the identified hotspot, both EP300 D1399 and CREBBP D1435 mutations have been found to reduce lysine acetylase activity in vitro (Peifer et al., 2012; Pasqualucci et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2008). We additionally identified a potential hotspot in KAT11 at position 105 with mutations in CREBBP (R1446) although this hotspot was not significant when correcting for multiple hypothesis testing (p = 2.6e−6, corrected p = 0.59, Fig. 4A). CREBBP R1446 is also located within the substrate binding loop (Liu et al., 2008) and R1446 mutations have been found in B-cell neoplasms (Pasqualucci et al., 2012).

Figure 4. Multiple sequence alignment of domains identifies mutation hotspots and associates rare mutations with known oncogenic hotspots.

(A) The amino acid sequence alignment of the KAT11 histone acetylate domain in CREBBP (position 1342–1648) and EP300 (position 1306–1612) is represented as a block of two by 308 rectangles. Using the resulting alignment coordinates, missense mutations are tallied across the domains of the two genes. Both amino acids of the alignment (block) and the resulting amino acids due to mutations (histogram) are color coded by their biochemical properties. Alignment gaps are indicated by gray rectangles. Significant hotspots are indicated with position in alignment (pos), p-value (pval), Bonferroni corrected p-value (p-cor), and number of mutations in top mutated genes and cancer types. Similar plots are shown for the MAD homology 2 (MH2) domain involved in SMAD protein-protein interactions (B) and the furin-like domain involved in RTK aggregation and signal activation (C).

Associating rare mutations with known oncogenic hotspots

The MAD homology 2 (MH2) domain is found in SMAD genes and mediates interaction between SMAD proteins and their interaction partners through recognition of phosphorylated serine residues (Wu et al., 2001). We found the known R361H/C hotspot mutation in SMAD4 (Shi et al., 1997; Ohtaki et al., 2001) aligned with three R268H/C mutations in SMAD3 (Fig. 4B and Table 2, row 4). In both proteins these residues are located in the conserved loop/helix region that is directly involved in binding TGFBR1 (Shi et al., 1997). R361C mutations inactivate the tumor suppressor SMAD4 (Shi et al., 1997), and recently, R268C mutations in SMAD3 were also found to repress SMAD3-mediated signaling (Fleming et al., 2013), supporting our association of rare arginine mutations in SMAD3 with known inactivating mutations in SMAD4. The majority of the mutations in the hotspot were from colorectal adenocarcinoma samples (COADREAD) and it is known that SMAD genes are recurrently mutated in this disease (Fleming et al., 2013). Interestingly, we found a non-significant (p = 0.25) tendency towards better survival for patients with hotspot mutations in colorectal cancer although more data is needed to confirm this, to our knowledge, unreported observation (Supplementary Fig. 5).

We associated several known hotspots in well-characterized cancer genes with rare but potentially functional mutations in genes not frequently mutated in cancer. For example, we found rare mutations in PIK3CB at E470 and at E552 in the PI3K C_2 domain and PI3Ka domain, respectively, that associated with known recurrent hotspots in PIK3CA (Table 2, row 6 and 14). Furthermore, in the cysteine-rich Furin-like domain, which is involved in receptor aggregation and signaling activation of ERBB-family RTKs, we identified several significant hotspots including rare mutations in ERBB3 (G284R) and ERBB2 (A293V) that aligned with the known activating driver mutations in EGFR (A289V/T) in glioblastoma (Lee et al., 2006) (Fig. 4C). Recently, one of these mutations, ERBB3 G284R, was found to promote tumorigenesis in mice (Jaiswal et al., 2013), suggesting that the singleton ERBB2 A293V mutation found in a melanoma sample could represent an infrequent oncogenic event. We also identified a hotspot at position 137 of the alignment with rare S303F mutations in ERBB4 aligning with S310F/Y mutations in ERBB2. Interestingly, in a functional analysis of ERBB2 mutations in lung cancer cell lines, S310F/Y mutations were found to increase ERBB2 signaling activity, promote tumorigenesis, and enhance sensitivity to ERBB2 inhibitors in vitro (Greulich et al., 2012). Future work will show if analogous mutations in ERBB4 (S303F) may have similar effects.

Identification of new hotspots in protein domains

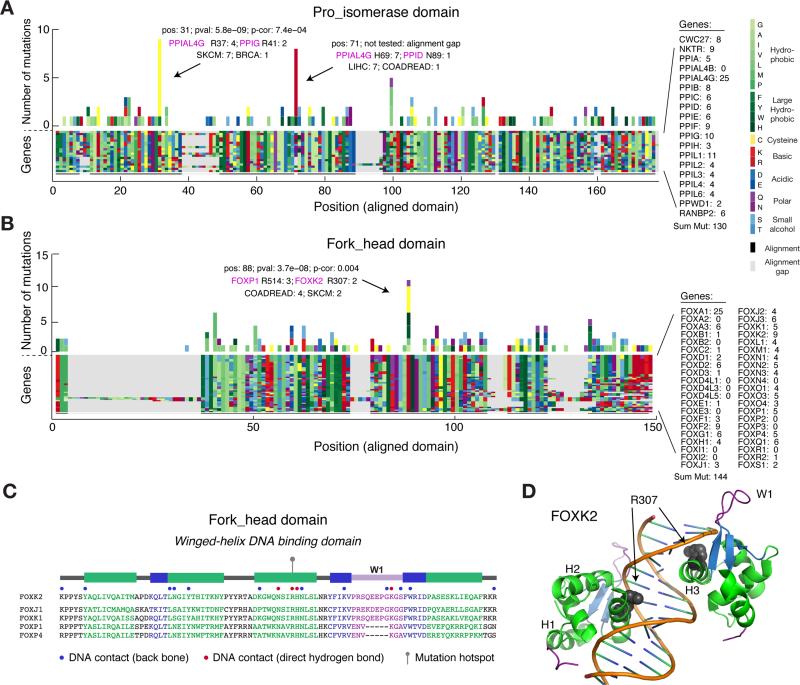

We also identified several additional hotspots in domains with mutations in genes not previously associated with cancer. We detected a hotspot in the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase domain (Pro_isomerase) with nine mutations distributed between PPIAL4G (R37C), PPIG (R41C), PPIA (R37C), PPIE (R173C) and PPIL2 (I308F) (Fig. 5A). The Pro_isomerase domain, which is distinct from the rotamase domain of PIN1, is present in genes that catalyze cis-trans isomerization of proline imidic peptide bonds and have been implicated in folding, transport, and assembly of proteins (Gothel and Marahiel, 1999). Seven of the nine mutations found in this hotspot were from melanoma samples, and interestingly we found that in melanoma these mutations correlate with significant upregulation of about a dozen genes including the cancer-testis antigens CTAG2, CTAG1B, CSAG2, and CSAG3 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Figure 5. Identification of new hotspots affecting conserved residues of protein domains.

Missense mutations are tallied across multiple sequence alignments of genes containing the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (Pro_isomerase) domain (A) and the forkhead domain (B). (C) Secondary structure of the forkhead domain consisting of four α-helices (H1-4), three β-sheets (S1-3), and one wing-like loop (W1). Sequences are shown for selected Fox transcription factors that had mutations in the identified hotspot in H3. Of note, the selected genes have a fourth α-helix rather than the canonical second wing-like loop found in other Fox genes. (D) Ribbon drawing of the crystal structure of two FOXK2 forkhead domains binding to a 16-bp DNA duplex containing a promoter sequence (pdb ID: 2C6Y) (Tsai et al., 2006). The R307 residue that we identified as mutated is shown with spheres.

The forkhead domain mediates DNA binding of forkhead box (Fox) transcription factors and encodes a conserved “winged helix” structure comprising three α-helices and three β-sheets flanked by one or two “wing”-like loops (Carlsson and Mahlapuu, 2002). In the forkhead domain, we identified a hotspot with 11 mutations distributed between FOXP1 (R514C/H), FOXK2 (R307C/H), FOXK1 (R354W), FOXJ1 (R170G/L), and FOXP4 (R516C) in several different cancer types (Fig. 5B). The identified hotspot was located in the third α-helix (H3), which exhibits a high degree of sequence homology across Fox proteins and binds to the major groove of DNA targets. Specifically, the arginine residue that we found mutated forms direct hydrogen bonding with DNA in both in FOXP and FOXK family transcription factors (Wu et al., 2006; Stroud et al., 2006; Chu et al., 2011) (Tsai et al., 2006) (Fig. 5C, D). Furthermore, experimental R307A substitution in FOXK2 abolishes DNA binding (Tsai et al., 2006), suggesting that the identified arginine mutations may play an important role in cancer by inhibiting DNA-binding of FOXP, FOXK, and related Fox transcription factors, although the hypothesis that the identified forkhead domain hotspot is an inactivating mutational event remains speculative.

We identified several other domain hotspots of potential interest such as a hotspot in the rasGAP GTPase activating domain with mutations in the tumor suppressors NF1, RASA1, and RASAL1, a hotspot in the kelch motif (Kelch 1 domain) with mutations in KEAP1 and KLHL4, as well as a hotspot in a domain of unknown function, DUF3497 (Supplementary Fig. 7). The potential biological consequence of these mutations remains to be elucidated. Many additional domain hotspots were identified and we make all analysis of hotspots in protein domains available via an interactive web-service at http://www.mutationaligner.org.

DISCUSSION

We have extended the principle of recurrence analysis for protein mutations observed in surgical cancer specimens. Instead of only summing the occurrence of mutations over all tumor samples, we also sum over all homologous sisters of a protein domain. This increases the power of inferring likely functional mutations in several ways by enabling or providing: (1) higher statistical power to detect mutation hotspots (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2); (2) functional characterization of rare mutations that are in homologous positions relative to mutations with known functions (Table 2, Fig. 4); (3) mechanistic clues or pathway linkage about the downstream effects of oncogenic mutations (Fig. 4); (4) prediction of new therapeutically actionable alterations by homologous relationship to known drug targets (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 4); (5) identification of subpathways from selective alteration in a subset of upstream domains (Fig. 4B); and (6) identification of novel domains with plausible oncogenic function based on aggregation of sub-threshold mutation counts (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 7). The impact of these methodological improvements on linking genotype and phenotype in cancer, as well as technical limitations, will be discussed below.

By extending the notion of recurrence of mutations from single genes to gene families, one immediately gains statistical power for interpreting recurrence (above random) of mutations across many cancer samples as evidence for a functional contribution to oncogenesis or tumor maintenance. This is especially useful for mutations, which are infrequently observed in a particular domain in the family, but for which there are analogous alterations in sister domains in the domain family. For example, we identified a hotspot in the forkhead domain, where the crucial DNA-contacting arginine residue in the third helix of the forkhead-encoded winged-helix structure was mutated in several FOXP and FOXK family transcription factors. We speculate that this mutation in the DNA binding part of the forkhead domain is a novel inactivating oncogenic event. Both examples illustrate the power of connecting the observation of mutations across common members of a domain family, enabling us to identify entirely new hotspots in domains with mutations in genes not previously associated with cancer.

Beyond the assertion of likely functional impact in cancer based on aggregate occurrence, we assigned specific functional consequences to some of the infrequent mutations in cases where the analogous residues in other family members have well-characterized functional roles. As many protein domains have been functionally characterized, one of the strengths of our approach is that such knowledge can provide mechanistic insight into the potential effect of alterations. For example, we associated mutations in infrequently altered genes with mutations in paralogous genes that have previously been implicated in cancer (see e.g. the identified hotspots in MH2, Furin-like, and PI3K_C2 domains). Thus, transfer of knowledge from well-studied oncogenes to less-studied homologues (“guilt by association”) can lead to testable hypotheses about the effect of rare alterations and hereby facilitate the functional interpretation of mutations in large cancer genomics datasets.

This analysis may also shed light on how oncogenic alterations in homologous domains are related in signaling pathways. While the effect of an oncogenic mutation on the function of an individual protein, such as signaling-independent enzymatic activity, may be known or can be ascertained experimentally, the downstream consequences are enmeshed in the full complexity of cell biological signaling pathways. Fortunately, the evolutionary relationships within a domain family plus the recurrence of specific residue alterations in the oncogenic selection process may provide clues as to similarity of mechanism and similarity of downstream consequences on cell physiology. For example, a furin-like domain is present in the extracellular region of both the ERBB2 and ERBB4 receptor tyrosine kinases. Our analysis clearly relates the known and fairly frequent oncogenic S310F/Y in ERRB2 mutations with two uncharacterized mutations S303F in ERBB4. Both sets of mutations plausibly execute similar biophysical mechanisms, in which the replacement of a small amino acid with an O-H side chain (S) with a large hydrophobic amino acid (F or Y) in a conserved region modifies receptor multimerization and activates downstream mitogenic signaling (Greulich et al., 2012). This example, and others in the current dataset, is suggestive of the general principle that recurrent mutations in analogous positions in evolutionarily related protein domains share aspects of molecular mechanism as well as downstream cell biological effects.

That mutations in domains of related genes may have similar mechanistic consequence or effects on downstream signaling, may also have therapeutic implications. In some cases plausibly actionable alterations can be identified through a homologous relationship to alterations in known drug targets. As the S310F/Y mutations in ERBB2 sensitize cancer cell lines to the RTK inhibitors neratinib, afatinib, and lapatinib (Greulich et al., 2012), the same may be true for the analogous S310F/Y mutations in ERBB4. Furthermore, using sequence and 3D structure analysis of the tyrosine kinase domain, we also find that the canonical hotspots of BRAF (V600E), FLT3 D835Y, and KIT D816V superimpose in the activation loop of the kinase domain controlling the enzymatic activity state (Supplementary Fig. 4). Notably, we found four EGFR L861Q/R mutations in lung cancer affecting an analogous residue in the activation loop. Based on the conserved structure-function relationship of the tyrosine kinase domain, these rare EGFR L861Q/R mutations may also represent activating events and could therefore be therapeutically actionable in analogy to the targetable BRAF V600E mutations. Encouragingly, non-small cell lung cancer patients with EGFR L861 mutations have recently shown positive clinical response when treated with EGFR-targeted therapy (Wu et al., 2011). In the spirit of personalized therapy and basket clinical trials (Garraway and Lander, 2013), this type of convergence of downstream consequences of analogous mutations may suggest specific therapeutic choices for an additional set of observed cancer-associated mutations.

The mutational patterns across a set of sequence-similar domains may also be useful in elucidating fine-grained detail of pathway signaling, such as a useful distinction between subpathways. For example, in the current dataset, out of the eight members of the MH2 domain-containing SMAD family, only SMAD3 and SMAD4 are mutated at analogous positions involved in TGFBR1 binding. While there is inherent uncertainty in any finite dataset, this observation raises the hypothesis that signaling events of SMAD3 and SMAD4 in cancer – or perhaps in general – are more closely related than those involving other MH2 domain containing proteins. In general, based on the mutational patterns in a large gene family, one may be able to uncover functional similarity between members of a family and thereby predict which subset of genes are involved in similar processes or particular signaling subpathways.

These examples illustrate the principle of using domains for linking genotype and phenotype and for inferring the biological relevance of rare mutations in homologous genes. This process of informational aggregation may also lead to the discovery of the functional roles of domains not previously associated with oncogenesis, particularly in cases where the frequency of mutations in each of the domains separately is below the recurrence threshold, but rises above the threshold when the multiple domain instances are equivalenced. For example, DUF3497, which is found in members of the G-protein coupled receptor 2 family, has not been previously described as being involved in cancer processes, but mutations in lung cancer and melanoma samples significantly cluster in a hotspot in this domain with a total of seven mutations observed in BAI3 (R588P/Q), ELTD1 (K132E/N), and CELSR1 (T2124A) (Supplementary Fig. 7C). This hotspot, with recurrent mutations in mostly basic amino acids (six out of seven mutations in K and R), is tantalizing as it suggests that mutations in this “domain of unknown function” confer a selective, functional advantage to cancer cells.

We here analyze mutations across domains in a set of related genes with the aim of identifying recurrent mutations with functional relevance (positive hotspots). However, if passenger mutations without functional relevance are aggregated across several genes, an approach based on homologous domains may incur the risk of detecting false positive hotspots compared to a gene-based approach. The detection of spurious domain hotspots could be exacerbated by mutation biases that alter amino acids disproportionately. For example, arginine is the most frequently altered amino acid in the majority of tumor types (Supplementary Fig. 1) as it has four codons containing CG dinucleotides, which are frequently subject to C→T transitions due to deamination of methylated cytosine to thymine. In several domains, such as the tetramerization (K_tetra) domain of potassium channel proteins (Supplementary Table 1) and the zf-H2C2 2 domain of zinc finger proteins (Table 2, row 16), we identified significant hotspots where arginine mutations align across a large set of genes in the domain family. Although the frequency of such hotspots may be driven by the arginine mutation bias, the mutations themselves may nevertheless be functional.

Future work will aim to refine the analysis of mutations in domains and expand the scope of our analysis to other functional elements in genes. Our focus here was on somatic missense mutations, but this requirement may be relaxed to include germ-line mutations or other somatic alterations (e.g., truncating mutations and small in-frame insertions and deletions). Importantly, truncating mutations affecting a particular domain may not necessarily actually be located in the domain but upstream of it, so we excluded truncating mutations from this work. An additional extension of our work would be to implement a sliding window for peak detection of clusters of mutations in domain alignments. However, our own observations suggest that mutation hotspots are largely limited to single residues. Other types of regulatory protein motifs can be analyzed, including short linear motifs that guide protein phosphorylation by kinases, which have previously been shown to be enriched for cancer-associated mutations in some genes (Reimand and Bader, 2013; Reimand et al., 2013). Finally, assessment of the functional impact of mutations using structural information and evolutionary sequence conservation, for example as applied in our mutation assessor method (Reva et al., 2011), and evolutionary residue-residue couplings derived from correlated mutations in protein family alignments (Marks et al., 2011; Marks et al., 2012), can be incorporated to provide additional insight into the potential role of mutations in cancer.

As more data become available, integrative approaches combining functional evidence across multiple scales such as genes, domains, and signaling pathways will be needed to improve the computational pipelines for variant function prediction. To make the results of our analysis directly useful to the community at large, we have made all findings available through an interactive web service (http://www.mutationaligner.org), which is connected to our cBioPortal database for cancer genomics data (http://www.cbioportal.org) through bidirectional links. The MutationAligner web resource will be periodically updated as mutation data on genomically profiled tumor samples becomes available in the public domain.

METHODS

Data collection and analysis

Detailed description of methods can be found in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures in the Supplemental Information. Briefly, around 460,000 missense mutations from 5496 exosome-sequenced tumor-normal pairs of 22 different tumor types studied by the TGCA consortium were obtained from the cBioPortal (Cerami et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013) in the format of TCGA level 3 variant data. Missense mutations were mapped to protein sequences and protein domains annotated by Pfam-A version 26 (Punta et al., 2011). Pfam-A domains were excluded from the analysis if a) no missense mutations were present, b) the Pfam-A expectancy score (e-value) was greater than 1e−5 or c) the domain was only present as one instance in the human genome. To assess if the mutation burden of the domain was larger than would be expected by chance, we a) implemented a permutation test, which compared the observed mutation burden of the domain to the distribution of burdens generated by randomly distributing mutations across genes containing the domain, and b) calculated a domain mutation enrichment score (equation 1, Supplemental Experimental Procedures). To identify putative hotspots for mutations within domains we used multiple sequence alignment of domain regions across protein families using BLOSUM80 as a scoring matrix. Mutations were tallied across samples and across domain-containing genes using the coordinates of the multiple sequence alignment. We used a binomial test, taking into account the length and total number of mutations observed in the domain, to generate a p-value by comparing the number of mutations observed at that domain position to what would be observed by chance assuming a random distribution of mutations (equation 2 and 3, Supplemental Experimental Procedures). We calculated an entropy score (S) based on Shannon information entropy to estimate how uniformly mutations are spread across domain-containing genes, where a high score indicates that multiple genes contribute to the observed mutations in the domain. The entropy score was normalized (S̄) to the domain family size, with a maximum score of 1, signifying that mutation counts are the same for all genes (equation 4 and 5, Supplemental Experimental Procedures). In total, 17,273 positions in the domain sequence alignments were analyzed based on the following criteria: a) at least two mutations occurred at each position and b) at least three quarters of the domain alignments were non-gaps at each position (residues with alignment gaps in more than 75% of the sequences were excluded from the domain hotspot analysis). All p-values were adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing using the stringent Bonferroni correction method.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Comprehensive analysis of cancer mutations in protein domains (mutationaligner.org)

Identification of new mutation hotspots across homologous domains

Functional coupling of rare, uncharacterized mutations and known oncogenic mutations

Mechanistic clues about downstream effects of mutations in signaling domains

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge C. Kandoth for technical assistance. C. Carmona-Fontaine, Debora S. Marks and A. Hanrahan for helpful discussions. V.A. Pedicord for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Genome Atlas grant (U24CA143840) and in part by Cancer Research UK (reference number C14303/A17197).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions

M.L.M. and E.R. designed analysis. N.P.G. designed and developed the web-site. M.L.M., E.R., N.P.G, B.A.A., A.K., J.G., G.C., N.S., and C.S. analyzed data. M.L.M. conceived and developed the concept. M.L.M. and C.S. managed the project. M.L.M, E.R, N.P.G and C.S. wrote manuscript. All authors contributed to discussions and editing of the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, seven figures, and two tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/...

REFERENCES

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature Chemical Biology. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SAJR, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Børresen-Dale A-L, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D, Berchuck A, Birrer M, Chien J, Cramer DW, Dao F, Dhir R, DiSaia P, Gabra H, Glenn P, et al. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts MJ, Lu Q, Jiang Y, Drusko A, Valtierra I, Schlessner M, Jaeger N, Jones DT, Pfister S, Eils R, et al. Mechismo : predicting mechanistic impact of mutations and modifications on molecular interactions. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:1–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg Y, Yachdav G, Rost B. SNAP predicts effect of mutations on protein function. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2008;24:2397–2398. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson P, Mahlapuu M. Forkhead Transcription Factors: Key Players in Development and Metabolism. Developmental Biology. 2002;250:1–23. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E, Demir E, Schultz N, Taylor BS, Sander C. Automated Network Analysis Identifies Core Pathways in Glioblastoma. PloS one. 2010;5:e8918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et al. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data. Cancer Discovery. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerchietti LC, Hatzi K, Caldas-Lopes E, Yang SN, Figueroa ME, Morin RD, Hirst M, Mendez L, Shaknovich R, Cole PA, et al. BCL6 repression of EP300 in human diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells provides a basis for rational combinatorial therapy. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120:4569–4582. doi: 10.1172/JCI42869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C, Gough J, Vogel C, Teichmann SA. Evolution of the protein repertoire. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2003;300:1701–1703. doi: 10.1126/science.1085371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y-P, Chang C-H, Shiu J-H, Chang Y-T, Chen C-Y, Chuang W-J. Solution structure and backbone dynamics of the DNA-binding domain of FOXP1: Insight into its domain swapping and DNA binding. Protein Science. 2011;20:908–924. doi: 10.1002/pro.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriello G, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Mutual exclusivity analysis identifies oncogenic network modules. Genome Research. 2012;22:398–406. doi: 10.1101/gr.125567.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton CJ, Morgan M, Gunaratne PH, Wheeler DA, Gibbs RA, Gordon Robertson A, Chu A, Beroukhim R, Cibulskis K, Signoretti S, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dees ND, Zhang Q, Kandoth C, Wendl MC, Schierding W, Koboldt DC, Mooney TB, Callaway MB, Dooling D, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, Ding L. MuSiC: Identifying mutational significance in cancer genomes. Genome Research. 2012;22:1589–1598. doi: 10.1101/gr.134635.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibb NJ, Dilworth SM, Mol CD. Switching on kinases: oncogenic activation of BRAF and the PDGFR family. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4:718–727. doi: 10.1038/nrc1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Greulich H, Muzny DM, Morgan MB, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming NI, Jorissen RN, Mouradov D, Christie M, Sakthianandeswaren A, Palmieri M, Day F, Li S, Tsui C, Lipton L, et al. SMAD2, SMAD3 and SMAD4 Mutations in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Research. 2013;73:725–735. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Science signaling. 2013;6:pl1–pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway LA, Lander ES. Lessons from the Cancer Genome. Cell. 2013;153:17–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz G, Gabriel SB, Cibulskis K, Lander E, Sivachenko A, Sougnez C, Lawrence M, Kandoth C, Dooling D, Fulton R, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. Functional impact bias reveals cancer drivers. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40:e169–e169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göthel SF, Marahiel MA. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases, a superfamily of ubiquitous folding catalysts. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 1999;55:423–436. doi: 10.1007/s000180050299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greulich H, Kaplan B, Mertins P, Chen T-H, Tanaka KE, Yun C-H, Zhang X, Lee S-H, Cho J, Ambrogio L, et al. Functional analysis of receptor tyrosine kinase mutations in lung cancer identifies oncogenic extracellular domain mutations of ERBB2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:14476–14481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203201109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerman PS, Lawrence MS, Voet D, Jing R, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Stojanov P, McKenna A, Lander ES, Gabriel S, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofree M, Shen JP, Carter H, Gross A, Ideker T. Network-based stratification of tumor mutations. Nature Chemical Biology. 2013;10:1108–1115. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Sander C. Mapping the protein universe. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1996;273:595–603. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal BS, Kljavin NM, Stawiski EW, Chan E, Parikh C, Durinck S, Chaudhuri S, Pujara K, Guillory J, Edgar KA, et al. Oncogenic ERBB3 Mutations in Human Cancers. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:603–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt DC, Fulton RS, McLellan MD, Schmidt H, Kalicki-Veizer J, McMichael JF, Fulton LL, Dooling DJ, Ding L, Mardis ER, et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Mermel CH, Robinson JT, Garraway LA, Golub TR, Meyerson M, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Getz G. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature. 2014a;505:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Stewart C, Mermel CH, Roberts SA, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2014b;499:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Vivanco I, Beroukhim R, Huang JHY, Feng WL, DeBiasi RM, Yoshimoto K, King JC, Nghiemphu P, Yuza Y, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation in glioblastoma through novel missense mutations in the extracellular domain. PLoS medicine. 2006;3:e485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnemann C, Buuren MMV, Bies L, Verdegaal EME, Schotte R, Calis J. J. a., Behjati S, Velds A, Hilkmann H, Atmioui D, et al. High-throughput epitope discovery reveals frequent recognition of neo-antigens by CD4 + T cells in human melanoma. Nature Medicine. 2014;21:1–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wang L, Zhao K, Thompson PR, Hwang Y, Marmorstein R, Cole PA. The structural basis of protein acetylation by the p300/CBP transcriptional coactivator. Nature. 2008;451:846–850. doi: 10.1038/nature06546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr JG, Stojanov P, Lawrence MS, Auclair D, Chapuy B, Sougnez C, Cruz-Gordillo P, Knoechel B, Asmann YW, Slager SL, et al. Discovery and prioritization of somatic mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) by whole-exome sequencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:3879–3884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121343109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks DS, Colwell LJ, Sheridan R, Hopf TA, Pagnani A, Zecchina R, Sander C. Protein 3D structure computed from evolutionary sequence variation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks DS, Hopf T. a., Sander C. Protein structure prediction from sequence variation. Nature biotechnology. 2012;30:1072–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLendon R, Friedman A, Bigner D, Van Meir EG, Brat DJ, M Mastrogianakis G, Olson JJ, Mikkelsen T, Lehman N, Aldape K, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ, Goya R, Mungall KL, Corbett RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, Chiu R, Field M, et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. 2012;476:298–303. doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehrt NL, Peterson TA, Park D, Kann MG. Domain landscapes of somatic mutations in cancer. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-S4-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaki N, Yamaguchi A, Goi T, Fukaya T, Takeuchi K, Katayama K, Hirose K, Urano T. Somatic alterations of the DPC4 and Madr2 genes in colorectal cancers and relationship to metastasis. International journal of oncology. 2001;18:265–270. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualucci L, Dominguez-Sola D, Chiarenza A, Fabbri G, Grunn A, Trifonov V, Kasper LH, Lerach S, Tang H, Ma J, et al. Inactivating mutations of acetyltransferase genes in B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2012;471:189–195. doi: 10.1038/nature09730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer M, Fernandez-Cuesta L, Sos ML, George J, Seidel D, Kasper LH, Plenker D, Leenders F, Sun R, Zander T, et al. Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer. Nature Genetics. 2012;44:1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/ng.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson TA, Adadey A, Santana-Cruz I, Sun Y, Winder A, Kann MG. DMDM: domain mapping of disease mutations. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2010;26:2458–2459. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson TA, Nehrt NL, Park D, Kann MG. Incorporating molecular and functional context into the analysis and prioritization of human variants associated with cancer. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2012;19:275–283. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;40:D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimand J, Bader GD. Systematic analysis of somatic mutations in phosphorylation signaling predicts novel cancer drivers. Molecular Systems Biology. 2013;9:637. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimand J, Wagih O, Bader GD. The mutational landscape of phosphorylation signaling in cancer. Scientific Reports. 2013;3 doi: 10.1038/srep02651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reva B, Antipin Y, Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:e118–e118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Hata A, Lo RS, Massagué J, Pavletich NP. A structural basis for mutational inactivation of the tumour suppressor Smad4. Nature. 1997;388:87–93. doi: 10.1038/40431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud JC, Wu Y, Bates DL, Han A, Nowick K, Paabo S, Tong H, Chen L. Structure of the Forkhead Domain of FOXP2 Bound to DNA. Structure. 2006;14:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torkamani A, Schork NJ. Identification of rare cancer driver mutations by network reconstruction. Genome Research. 2009;19:1570–1578. doi: 10.1101/gr.092833.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai KL, Huang CY, Chang CH, Sun YJ, Chuang WJ, Hsiao CD. Crystal Structure of the Human FOXK1a-DNA Complex and Its Implications on the Diverse Binding Specificity of Winged Helix/Forkhead Proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:17400–17409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang NJ, Sanborn Z, Arnett KL, Bayston LJ, Liao W, Proby CM, Leigh IM, Collisson EA, Gordon PB, Jakkula L, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in Notch receptors in cutaneous and lung squamous cell carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:17761–17766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114669108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JP, Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Blacklow SC, Look AT, Aster JC. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2004;306:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JW, Hu M, Chai J, Seoane J, Huse M, Li C, Rigotti DJ, Kyin S, Muir TW, Fairman R, Massagué J, Shi Y. Crystal structure of a phosphorylated Smad2. Recognition of phosphoserine by the MH2 domain and insights on Smad function in TGF-beta signaling. Molecular Cell. 2001;8:1277–1289. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Yu CJ, Chang YC, Yang CH, Shih JY, Yang PC. Effectiveness of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors on ”Uncommon” Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations of Unknown Clinical Significance in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17:3812–3821. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Borde M, Heissmeyer V, Feuerer M, Lapan AD, Stroud JC, Bates DL, Guo L, Han A, Ziegler SF, Mathis D, Benoist C, Chen L, Rao A. FOXP3 Controls Regulatory T Cell Function through Cooperation with NFAT. Cell. 2006;126:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Petsalaki E, Rolland T, Hill DE, Vidal M, Roth FP. Protein Domain-Level Landscape of Cancer-Type-Specific Somatic Mutations. PLoS computational biology. 2015;11:e1004147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue P, Forrest WF, Kaminker JS, Lohr S, Zhang Z, Cavet G. Inferring the functional effects of mutation through clusters of mutations in homologous proteins. Human Mutation. 2010;31:264–271. doi: 10.1002/humu.21194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue P, Melamud E, Moult J. SNPs3D: candidate gene and SNP selection for association studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.