Abstract

Objective

To better understand the role of hope among terminally ill cancer patients.

Design

Qualitative analysis.

Setting

A tertiary specialized cancer centre in Canada.

Participants

Cancer patients in palliative care with an estimated remaining life expectancy of 12 months or less (N = 12) and their loved ones (N = 12) and treating physicians (N = 12).

Methods

Each patient underwent up to 3 interviews and identified a loved one who participated in 1 interview. Treating physicians were also interviewed. All interviews were fully transcribed and analyzed by at least 2 investigators. Interviews were collected until saturation occurred.

Main findings

Seven attributes describe the experiences of palliative cancer patients and their caregivers: hope as an irrational phenomenon that is a deeply rooted, affect-based response to adversity; initial hope for miraculous healing; hope as a phenomenon that changes over time, evolving in different ways depending on circumstances; hope for prolonged life when there is no further hope for cure; hope for a good quality of life when the possibility of prolonging life becomes limited; a lack of hope for some when treatments are no longer effective in curbing illness progression; and for others hope as enjoying the present moment and preparing for the end of life.

Conclusion

Approaches aimed at sustaining hope need to reflect that patients’ reactions might fluctuate between despair and a form of acceptance that leads to a certain serenity. Clinicians need to maintain some degree of hope while remaining as realistic as possible. The findings also raise questions about how hope influences patients’ perceptions and acceptance of their treatments.

Résumé

Objectif

Mieux comprendre le rôle de l’espoir chez un patient cancéreux en phase terminale.

Type d’étude

Analyse qualitative.

Contexte

Un établissement tertiaire spécialisé en oncologie situé au Canada.

Participants

Des patients cancéreux en phase palliative avec une espérance de vie estimée à moins d’un an (N = 12), leurs proches (N = 12) et leurs médecins traitants (N = 12).

Méthodes

Les patients ont été interviewés jusqu’à 3 reprises; chacun a désigné un proche qui a été interviewé une fois. Toutes les entrevues ont été transcrites intégralement et analysées par au moins 2 chercheurs. On a effectué des entrevues jusqu’à l’atteinte de la saturation.

Principales observations

Des patients en phase terminale et leurs soignants ont décrit leur expérience à l’aide de 7 caractéristiques : l’espoir comme un phénomène irrationnel profondément ancré, correspondant à une réaction affective à l’adversité; l’espoir initial d’une guérison miraculeuse; l’espoir comme un phénomène qui change avec le temps et qui évolue différemment selon les circonstances; l’espoir de vivre plus longtemps même s’il n’y a plus d’espoir de guérison; l’espoir d’une bonne qualité de vie lorsque la possibilité de vivre plus longtemps est de plus en plus limitée; pour certains, une diminution de l’espoir quand les traitements n’arrivent plus à ralentir la progression de la maladie; et pour d’autres, une forme d’espoir qui consiste à apprécier le moment présent et à se préparer à mourir.

Conclusion

Les façons de soutenir l’espoir chez un patient doivent tenir compte du fait que ses réactions peuvent fluctuer entre le désespoir et une forme d’acceptation menant à une certaine sérénité. Le clinicien se doit de maintenir un certain degré d’espoir tout en demeurant le plus réaliste possible. Les présentes observations nous amènent également à nous demander comment l’espoir modifie la façon dont le patient perçoit son traitement et comment il l’accepte.

Supporting patients at the end of their lives is a recurring theme in articles aimed at general practitioners,1–3 as end-of-life care has become a core family physician role.4–6 For professionals working with these patients, preserving and raising their level of hope should be a therapeutic goal.7–9 Accordingly, considerable attention has been paid to the concept of hope in the medical literature in recent decades.10–12 It is considered an important coping mechanism in the care of cancer13,14 and other life-threatening illnesses. A high level of hope is positively associated with well-being and good quality of life, not only for patients but also for their families.15–17 An inverse association has been shown between hope and pain intensity, although this association disappears when controlling for depression or spiritual well-being.18

Dufault and Martocchio19 defined hope as a multidimensional concept characterized by a confident but uncertain anticipation of a future that is positive, realistic, and important from a personal standpoint. While this definition subsequently inspired other work,20–22 several authors contend that hope remains misunderstood and poorly defined,11,23,24 particularly among patients’ loved ones and health professionals.25

Given the many noncurative treatments now offered to cancer patients, there is a need to reevaluate what hope represents for people faced with a terminal illness like cancer. The aim of the present study was to better understand the role of hope among people with cancer in the palliative phase and to examine whether hope changes over the course of the illness. To explore this topic, we collected the experiences of hope from different participants (patients, loved ones, and treating physicians) dealing with incurable cancer.

METHODS

Because hope among the terminally ill is a complex phenomenon, in-depth analysis is essential to its understanding. We therefore used a qualitative analysis methodology to develop a detailed conceptualization based on in-depth interviews with people directly involved.26

Population studied

The study was conducted in Montreal, Que, in one of Canada’s main cancer diagnosis and treatment centres, comparable to most large North American hospitals. After approval by the research ethics committee, the project was shared with the hospital’s oncologists to obtain their collaboration. They were asked to identify patients who could participate in the study, based on the following inclusion criteria: being 18 years of age or older, not cognitively impaired, and in the palliative stage of their cancer, with an estimated remaining life expectancy of no more than 12 months. Exclusion criteria were the inability to express themselves in English or French or being unable to provide free and informed consent.

Data collection

Patients identified by their oncologists were contacted by a member of the research team who gave them detailed information about the study and what their participation would involve, verified their interest in participating (only 1 patient declined to participate at this stage), and scheduled a first interview. The consent form, which included permission to consult the medical chart, was signed at the first interview, usually conducted in the patient’s home. Recruited patients were advised that 3 different interviews could take place at various intervals determined by the course of the illness and treatments. At the end of the first interview, patients provided sociodemographic data and were asked to designate a loved one who would also consent to be interviewed.

Researchers contacted these designated persons and obtained their consent after informing them about the study. Each was interviewed individually without the patient being present so they could freely discuss their own experiences of hope.

All the patients’ treating physicians agreed to be interviewed shortly after the selection. Thus, patient– physician–loved one triads were created that could theoretically generate 5 interviews.

The semistructured interviews began with open-ended questions (interview guide is available from the corresponding author, S.D., on request). These initial questions did not suggest predetermined responses. They focused on the illness experience, the concept of hope, and how hope changed over time. All interviews were fully transcribed, and transcripts were then systematically verified by the interviewer. Interviews were conducted by one researcher (S.D.) or by a research assistant. Sample quotations were translated after the analysis and manuscript preparation were complete.

As data collection and analysis were concurrent, a sampling approach aligned with our theoretical objectives27,28 was used progressively to avoid recruiting participants of the same age, sex, or diagnosis, so as to broaden the spectrum of experiences studied. At the same time, we refined the interview template with more detailed questions to explore the material in greater depth and validate the conceptualization items emerging from the concurrent analysis. Thus, questions were added to the original interview template as new attributes emerged during the analysis.

Following the analysis, the resulting theoretical model was presented to the loved ones and physicians in 2 different discussion groups for validation.

Data analysis

Analysis was conducted in 3 phases, following the recommendations of Charmaz.26 The first phase involved open coding of each unit of text in the transcripts, staying as close as possible to the words used by participants. A more focused coding was performed in a second phase, in which more abstract categories were defined. Last, a theoretical analysis identified links among the categories, presented in a conceptual diagram describing the experience of hope in people (patients, loved ones, and physicians) affected by incurable cancer. All analyses were performed by at least 2 researchers who worked independently and then compared their results. Divergences were discussed until consensus was reached; such divergences involved less than 5% of all the data.

The scientific merit of the analysis was established based on criteria suggested by Marcus and Liehr.29 The credibility of findings was ensured by confirming the analyses with patients in the second and third interviews, and with their loved ones and physicians in group discussions held to present the theoretical model. The quality of the analysis was validated by cross-analyses conducted by at least 2 researchers and by regular validation meetings attended by the entire research team.

We continued the interviews until we reached saturation, when the last interviews yielded no new categories or new relationships among the themes in the theoretical model.

The interview transcripts were analyzed using QSR NVivo 7.30

FINDINGS

Sample

The sample consisted of 36 participants whose characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Sample quotations from participants illustrating the various attributes of hope appear in Table 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patient participants and their loved ones

| PATIENT | SEX | AGE, Y | TYPE OF CANCER | LOVED ONE’S RELATION TO PATIENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT-01 | Male | 63 | Brain | Wife |

| PT-02 | Female | 50 | Ovarian | Mother |

| PT-03 | Female | 44 | Breast | Husband |

| PT-04 | Male | 53 | Lung | Friend |

| PT-05 | Female | 60 | Lung | Sister |

| PT-06 | Male | 47 | Stomach | Sister |

| PT-07 | Female | 67 | Undetermined site, metastasis | Son |

| PT-08 | Female | 39 | Appendix, breast | Father |

| PT-09 | Female | 59 | Colon | Daughter |

| PT-10 | Male | 63 | Bile ducts | Son |

| PT-11 | Male | 65 | Melanoma | Wife |

| PT-12 | Male | 61 | Head and neck | Wife |

Table 2.

Characteristics of physician participants

| PHYSICIAN | SEX | YEARS IN PRACTICE | SPECIALTY |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD-01 | Male | 33 | Medical |

| MD-02 | Female | 34 | Surgical |

| MD-03 | Male | 6 | Medical |

| MD-04 | Male | 43 | Medical |

| MD-05 | Male | 20 | Medical |

| MD-06 | Male | 18 | Medical |

| MD-07 | Male | 11 | Medical |

| MD-08 | Male | 33 | Medical |

| MD-09 | Male | 6 | Medical |

| MD-10 | Male | 37 | Surgical |

| MD-11 | Female | 3 | Medical |

| MD-12 | Male | 19 | Medical |

Table 3.

Quotations illustrating the themes that emerged during interviews

| ATTRIBUTE | SAMPLE QUOTATIONS |

|---|---|

| 1. Hope as an irrational phenomenon |

|

| 2. Hope for a miracle |

|

| 3. Hope as a phenomenon that changes over time |

|

| 4. Hope for prolonged life |

|

| 5. Hope for good quality of life |

|

| 6. Lack of hope |

|

| 7. Hope as enjoying the present and preparing for the end |

|

LO—loved one, MD—physician, PT—patient, Q—question, R—response.

Hope pathway in people living with incurable cancer.

By conceptualizing the data, we were able to discern the hope pathway in terminally ill cancer patients in the palliative phase. This pathway is not rectilinear and it includes several states, to which we assigned certain attributes. Rather than present the results of the interviews separately by group (patients, loved ones, and physicians), we present them together, as all 3 groups raised the same themes, and as it is more relevant to highlight how the different groups’ statements mirrored one another.

Attribute 1. Hope as an irrational phenomenon: For the respondents, hope was akin to a human reflex, a coping mechanism shared by all humans contending with life-threatening illness. One metaphor, that of radar guiding a ship on a stormy sea, was particularly striking. Hope is a deeply rooted, affect-based disposition that eschews rational, linear logic. It is created through a combination of people denying part of what they have been told and maintaining self-preserving illusions, and a communication approach that one physician described as “white lies.”

Attribute 2. Hope for a miracle: Hope is also a phenomenon by which the person projects himself or herself into the future. Even though all the patients in our study had been advised of the palliative status of their illness, most envisioned a future for themselves in which they were cured, even if that projected status required a miracle. Patients might assume a cure is impossible and give up expecting one, while at the same time entertaining the small, irrational possibility of a miracle. Loved ones shared this hope for a miraculous cure, whereas physicians found it difficult to deal with patients whose decisions about treatment were not based on plausible scenarios.

Attribute 3. Hope as a phenomenon that changes over time: With progression of the patient’s illness—as revealed, for example, by test results—the hope for a cure, being a dynamic phenomenon, was modified. The objectives of patients and their loved ones changed over time, expressing another type of adjustment that was more focused on reality.

Attribute 4. Hope for prolonged life: As they moved toward a more rational understanding of their illness, fostered by the progression of symptoms showing they were not moving toward a cure, patients adjusted and redirected their hope toward new goals. They understood a cure was unrealistic and instead envisioned a future in which their life expectancy might be prolonged. In some cases the hoped-for prolongation remained unrealistic, such as living another 20 years, which would essentially correspond to a cure. One patient even associated this desire for longer life with the desire for immortality, which he transformed into a more acceptable form of longer life. For several respondents, this perception represented a sort of bargaining in which the patient “buys time” by undergoing treatments.

Attribute 5. Hope for good quality of life: Over time, as patients absorbed the reality that the possibility of prolonging their lives was probably limited, they focused their hope instead on quality of life. The desire to live longer might simply be part of the survival instinct that characterizes all biologic species. However, the patients and their loved ones did not want longer lives if quality of life would be impaired, which meant different things to different individuals. For some, a good-quality life was simply a comfortable life, whereas for others, it meant being able to have experiences that were not always possible given the limitations imposed by their illness. For several, it meant “normal life”—that is, life as it was before their illness.

Attribute 6. Lack of hope: For one group of patients, the end of hope for effective medical intervention gave way to hopelessness, accompanied by sadness and nonacceptance of the advancing illness. In some cases, it was actually despair related to a letting go, expressed as withdrawal in the face of illness and from life itself. With no hope of cure, these patients sank into a state of distress prompted by their direct confrontation of death. However, many physicians interviewed saw this recognition of reality as a necessary phase, as hope cannot be limitless.

Attribute 7. Hope as enjoying the present and preparing for the end: When all hope for successful treatment had evaporated, some patients did not accept the inevitable; they succumbed to hopelessness or despair and were devastated. Others, however, focused their residual hope on preparing for the end of their life and enjoying the present. As their illness advanced, they abandoned magical thinking. For some, their illness led to positive self-transformation accompanied by acceptance of what was to come. They achieved a measure of reconciliation with their personal experience and their incurable illness, and the remainder of their lives became an opportunity for further living. Some even spoke of “healing” when talking about this acceptance and the resulting inner peace.

Conceptualization of hope.

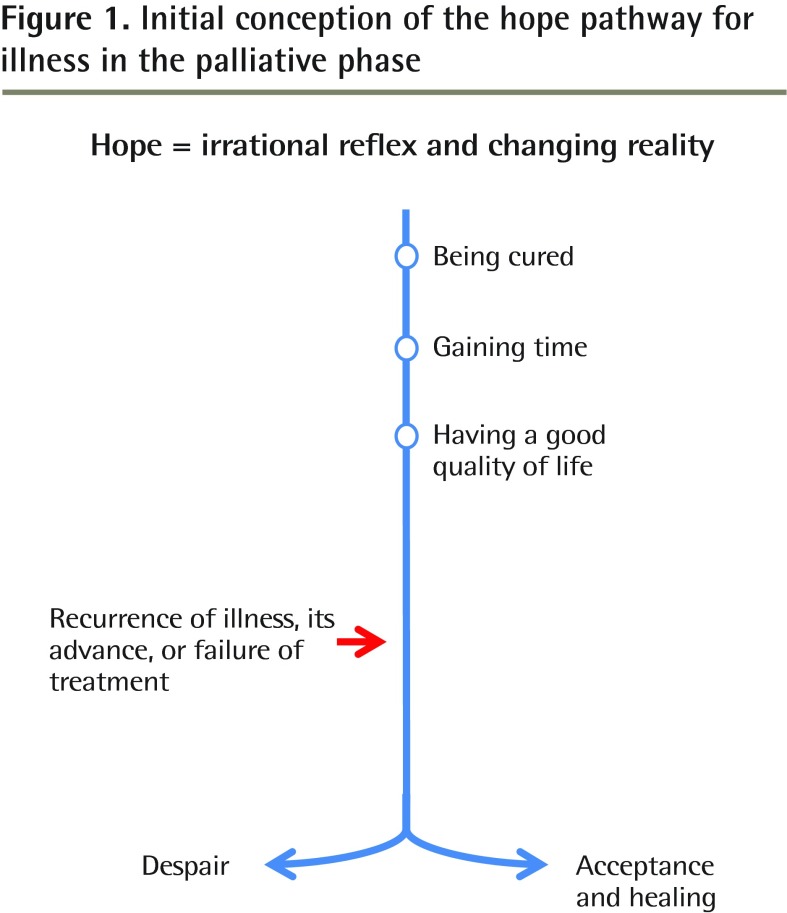

We first conceptualized hope using a linear model (Figure 1). In this initial model, patients passed through states that were each assimilated into successive stages of hope, which was a progressive adjustment to reality, up to the point where a second shock occurred, such as recurrence of the illness, its advance, or treatment failure. This second shock placed patients at a sort of crossroads, from which they could proceed either toward despair and sadness with no possible solution or toward acceptance and a form of serenity.

Figure 1.

Initial conception of the hope pathway for illness in the palliative phase

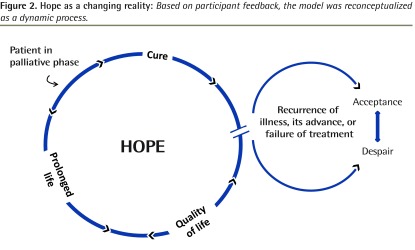

When the elements of this model were presented to the 3 groups of participants, they did not fully embrace the model because they thought its static nature did not reflect their experience. We therefore continued working on the theoretical analysis to achieve a model that would reflect their reality more accurately (Figure 2). In this model, the same attributes coexist, but in a circular relationship, recognizing that patients might experience the different attributes in any direction. In this model, as the illness advances to a confirmed terminal phase, patients might vacillate between despair and acceptance, a phenomenon that more closely reflects clinical experience in the field. The arrow between despair and acceptance can go in both directions. The phenomenon of acceptance, when it arises, can bring a new cycle of hope for the patient.

Figure 2.

Hope as a changing reality: Based on participant feedback, the model was reconceptualized as a dynamic process.

DISCUSSION

The present study adds to the body of knowledge in palliative care by highlighting attributes of hope that we believe more accurately reflect the current experiences of people with terminal illnesses. This knowledge is important for family physicians, as there is increasing recognition, both in Canada and elsewhere in the world, that they should be involved at every stage in the cancer process.31–34 One of these attributes, likely the most important, is that hope is a deeply rooted, affect-based disposition that eschews rational, linear logic—a fact that has an effect on care providers’ interactions with such patients. This study also suggests a hope dynamic that underlies this process, the complexity of which has been well described by others.35,36 In the successive attributes, we see that patients do not hesitate to contradict themselves, as this phenomenon is not strictly in the realm of the rational. Some authors,37,38 for instance, have observed that hope, despair, and acceptance can coexist within a single person.

It is interesting to note that spirituality is not included among the constituent attributes of the model of hope suggested by this study. In fact, we were unable to retain this attribute, as it exercised a potential influence on hope in only 5 of the patients, and even in those, spirituality figured in their statements only to a limited extent. The explanations for this might have to do with culture (for example, 3 patients reported having no spiritual reference in their experience) or with the fact that exploration of spirituality—a very complex phenomenon that extends beyond religion—did not appear in the objectives of the present study. Further research specifically on this subject would be useful to shed light on this phenomenon.

Some of this study’s results concur partly with reports published in recent decades,39–41 which supports the validity of our conclusions. Indeed, a few studies have shown that patients might hope for a cure while being simultaneously cognizant of the terminal nature of their illness.42–44 This phenomenon could well be on the rise now that patients are offered myriad treatment options not available 30 or 40 years ago. Concretely, this finding should encourage family physicians, when listening to their patients, to keep in mind that hope is, increasingly, a continuously changing reality that needs to be monitored closely.

The physicians’ statements showed that they were inclined to adopt a more realistic position, but many seemed conscious that hope should not be taken away abruptly, definitively, and absolutely, and this awareness complicated their clinical practice. They constantly needed to maintain a delicate balance between telling the truth and holding out some form of hope. It is therefore important for family physicians, who follow their patients with cancer throughout the course of their illness and play an even more active role in the palliative phase, to encourage realistic forms of hope at each stage of the illness so that patients and their loved ones can make the most appropriate decisions.

Limitations

This exploratory study does have certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting and generalizing the results to other populations of terminally ill patients. The qualitative design precludes any statistical generalization. The sample composition does, however, allow for comparisons with other settings in which practices are essentially similar to those of the recruitment setting.

The participant selection process might also limit the relevance of the results, in that the referring physicians for this study chose patients who wanted and were able to talk about their experiences with illness and hope. Less talkative patients were thus underrepresented in this design, and their experiences might be different from what we encountered. Nevertheless, the fact that our data allowed us to identify an attribute related to despair suggests that the study participants represented a spectrum of possible patients. On the other hand, the participants’ characteristics with regard to basic pathology, age, and sex make the results of this study applicable to patients with similar characteristics.

Moreover, as suggested by Kendall et al,45 results pertaining to cancer patients might not apply to patients with terminal illnesses not related to cancer.

In terms of future research, the findings of this study raise questions about the influence of various attributes of hope on how patients perceive their treatments, their understanding of those treatments, and their decisions to accept or refuse them. It would also be useful to explore further how patient-physician relationships and those between loved ones and care providers influence hope. Finally, according to Duggleby et al,23 it is possible that hope changes in interaction with suffering. Further research is needed on potential links between hope and suffering (prevented or caused), keeping in mind that the prime mission of medicine is to prevent and alleviate suffering.46

Conclusion

This study sheds further light on what hope represents for patients with a terminal illness, their loved ones, and their physicians. The attributes of hope focus initially on cure, then shift toward prolonging survival, and then to improving quality of life. As the illness advances, this hope might evolve into a form of acceptance or, conversely, give way to despair, phenomena that can alternate over time in either direction. This study also highlights the need to avoid oversimplifications, both in clinical interactions and in research, as it provides valuable insights from both the clinical and research perspectives. Family physicians clearly need to maintain some degree of hope in their patients while remaining as realistic as possible, even if this balance is tenuous. It is important for clinicians to understand and remember that hope is a dynamic phenomenon to which they must adapt from one day to the next.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, their loved ones, and the clinicians who participated in this study. We thank Lucie Le Blanc for transcription and administrative support, Rémi Coignard-Freidman for assistance with data collection, and Donna Riley for English translation of the manuscript. We also thank the Department of Family and Emergency Medicine at the University of Montreal for financial support of translation. This study was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Fondation Jacques-Bouchard, and Fondation PalliAmi.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Hope is positively associated with well-being and good quality of life for patients and their families. This study aimed to better understand the role of hope among people with cancer in the palliative phase and to examine whether hope changes over the course of the illness.

After interviewing patients, their loved ones, and their physicians, the authors initially conceptualized hope using a linear model: patients passed through states that were each assimilated into successive stages of hope, which was a progressive adjustment to reality until the illness recurred or advanced, or treatment failed. In response to participant feedback, the authors then proposed a model in which, as the illness advances to a confirmed terminal phase, patients vacillate between despair and acceptance, a phenomenon that more closely reflected the clinical experience.

For family physicians, who follow patients with cancer throughout their illness, it is important to play an active role in the palliative phase and to encourage realistic forms of hope at each stage of illness so that patients and their loved ones can make the most appropriate decisions.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

L’espoir est associé de façon positive au bien-être et à la qualité de vie, et ce, tant pour le patient que pour sa famille. Cette étude voulait mieux comprendre le rôle que joue l’espoir chez un patient cancéreux en phase palliative et vérifier si l’espoir varie au cours de sa maladie.

Après avoir interviewé des patients, leurs proches et leurs médecins, les auteurs ont d’abord conceptualisé l’espoir à l’aide d’un modèle linéaire selon lequel le patient passe par des états successifs dont chacun est assimilé à un niveau différent d’espoir, ce qui correspond à un ajustement progressif à la réalité jusqu’au moment où la maladie récidive ou s’aggrave, ou que le traitement échoue. En réponse à la rétroaction des participants, les auteurs ont alors proposé un modèle dans lequel le patient, à mesure que sa maladie progresse vers une phase terminale inéluctable, oscille entre le désespoir et l’acceptation, un phénomène qui correspond mieux à l’expérience clinique.

Pour le médecin de famille qui suit un patient cancéreux durant toute sa maladie, il est important de jouer un rôle actif durant la phase palliative et d’encourager une forme réaliste d’espoir à chaque stade de la maladie de façon à ce que le patient et ses proches puissent prendre les décisions les plus appropriées.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Crow FM. Final days at home. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:543–5. (Eng), e304–7 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemire F. Accompanying our patients at the end of their journey. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:860. (Eng), 859 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence K. Reflecting on end-of-life care. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:953. (Eng), 954 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall D, Howell D, Brazil K, Howard M, Taniguchi A. Enhancing family physician capacity to deliver quality palliative home care. An end-of-life, shared-care model. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1703, e1–7. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/54/12/1703.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2016 Jun 24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann F, Daneault S. Palliative care. First and foremost the domain of family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:417–8. (Eng), 424–5 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daneault S, Dion D. Suffering of gravely ill patients. An important area of intervention for family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:1343–5. (Eng), 1348–50 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kakuta M, Kakikawa F, Chida M. Concerns of patients undergoing palliative chemotherapy for end-stage carcinomatous peritonitis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(8):810–6. doi: 10.1177/1049909114546544. Epub 2014 Aug 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsman E, Leget C, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Willems D. Should palliative care patients’ hope be truthful, helpful or valuable? An interpretative synthesis of literature describing healthcare professionals’ perspectives on hope of palliative care patients. Palliat Med. 2014;28(1):59–70. doi: 10.1177/0269216313482172. Epub 2013 Apr 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olver IN. Evolving definitions of hope in oncology. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6(2):236–41. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283528d0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith TJ, Dow LA, Virago EA, Khatcheressian J, Matsuyama R, Lyckholm LJ. A pilot trial of decision aids to give truthful prognostic and treatment information to chemotherapy patients with advanced cancer. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(2):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alidina K, Tettero I. Exploring the therapeutic value of hope in palliative nursing. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8(3):353–8. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClement SE, Chochinov HM. Hope in advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(8):1169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folkman S. Stress, coping, and hope. Psychooncology. 2010;19(9):901–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felder BE. Hope and coping in patients with cancer diagnoses. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(4):320–4. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200407000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duggleby W, Williams A, Holstlander L, Thomas R, Cooper D, Hallstrom LK, et al. Hope of rural women caregivers of persons with advanced cancer: guilt, self-efficacy and mental health. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14:2561. Epub 2014 Mar 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duggleby W, Williams A, Holstlander L, Cooper D, Ghosh S, Hallstrom LK, et al. Evaluation of the living with hope program for rural women caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Utne I, Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Rustøen T. Association between hope and burden reported by family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(9):2527–35. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1824-5. Epub 2013 Apr 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawdin B, Evans C, Rabow M. The relationships among hope, pain, psychological distress, and spiritual well-being in oncology outpatients. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(2):167–72. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0223. Epub 2012 Oct 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dufault K, Martocchio BC. Hope: its spheres and dimensions. Nurs Clin North Am. 1985;20(2):379–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herth K. Relationship of hope, coping styles, concurrent losses, and setting to grief resolution in the elderly widow(er) Res Nurs Health. 1990;13(2):109–17. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herth K. Fostering hope in terminally-ill people. J Adv Nurs. 1990;15(11):1250–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1990.tb01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17(10):1251–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duggleby W, Hicks D, Nekolaichuk C, Hostlander L, Williams A, Chambers T, et al. Hope, older adults, and chronic illness: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(6):1211–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05919.x. Epub 2012 Jan 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wein S. The oncologist’s duty to provide hope: fact or fiction?. In: Govindan R, Smith C, Burke L, Dottellis D, Greaves L, editors. American Society Of Clinical Oncology 2012 educational book. 48th Annual Meeting, June 1–5, 2012; Chicago, Illinois. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2012. pp. e20–3. Available from: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/120-114. Accessed 2016 Jun 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kylmä J. Despair and hopelessness in the context of HIV—a meta-synthesis on qualitative research findings. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(7):813–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, UK: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glaser B, Strauss A. La découverte de la théorie ancrée. Stratégies pour la recherche qualitative. Paris, Fr: Armand Colin; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcus M, Liehr P. Qualitative approaches to research. In: LoBiondo-Wood G, Haber J, editors. Nursing research: methods, critical appraisal and utilization. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002. pp. 139–64. [Google Scholar]

- 30.QSR International . NVivo qualitative data analysis software. 7th ed. Doncaster, Aust: QSR International; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen MJ, Binz-Scharf M, D’Agostino T, Blakeney N, Weiss E, Michaels M, et al. A mixed-methods examination of communication between oncologists and primary care providers among primary care physicians in underserved communities. Cancer. 2015;121(6):908–15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29131. Epub 2014 Nov 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duns G. Cancer and primary care. Aust Fam Physician. 2014;43(8):501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aubin M, Vézina L, Verreault R, Fillion L, Hudon E, Lehmann F, et al. Family physician involvement in cancer care and lung cancer patient emotional distress and quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(11):1719–27. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1010-y. Epub 2010 Sep 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aubin M, Vézina L, Verreault R, Fillion L, Hudon E, Lehmann F, et al. Family physician involvement in cancer care follow-up: the experience of a cohort of patients with lung cancer. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(6):526–32. doi: 10.1370/afm.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaufel MA, Nordrehaug JE, Malterud K. Hope in action—facing cardiac death: a qualitative study of patients with life-threatening disease. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2011;6(1):5917. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v6i1.5917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clayton JM, Hancock K, Parker S, Butow PN, Walder S, Carrick S, et al. Sustaining hope when communicating with terminally ill patients and their families: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2008;17(7):641–59. doi: 10.1002/pon.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sachs E, Kolva E, Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. On sinking and swimming: the dialectic of hope, hopelessness, and acceptance in terminal cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(2):121–7. doi: 10.1177/1049909112445371. Epub 2012 May 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kylmä J, Duggleby W, Cooper D, Molander G. Hope in palliative care: an integrative review. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(3):365–77. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grube M. Compliance and coping potential of cancer patients treated in liaison-consultation psychiatry. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(2):211–29. doi: 10.2190/73UU-R7AY-P0LE-QQ5L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyckholm LJ. Thirty years later: an oncologist reflects on Kübler-Ross’s work. Am J Bioeth. 2004;4(4):W29–31. doi: 10.1080/15265160490908059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kübler-Ross E. On death & dying. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, Touchstone; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olsman E, Leget C, Duggleby W, Willems D. A singing choir: understanding the dynamics of hope, hopelessness, and despair in palliative care patients. A longitudinal qualitative study. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(6):1643–50. doi: 10.1017/S147895151500019X. Epub 2015 Apr 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson CA. “Our best hope is a cure.” Hope in the context of advance care planning. Palliat Support Care. 2012;10(2):75–82. doi: 10.1017/S147895151100068X. Epub 2012 Feb 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, Tattersall MN. Fostering coping and nurturing hope when discussing the future with terminally ill cancer patients and their caregivers. Cancer. 2005;103(9):1965–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kendall M, Carduff E, Lloyd A, Kimbell B, Pinnock H, Murray SA. Dancing to a different tune: living and dying with cancer, organ failure and physical frailty. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;5(1):101–2. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(11):639–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198203183061104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]