Abstract

Objective

To discover the frequency of psychosocial and other diagnoses occurring at the end of a visit when patients present to their FPs with concerns about fatigue.

Design

Cross-sectional study of patient-FP encounters for fatigue.

Setting

Ten FP practices in southwestern Ontario.

Participants

A total of 259 encounters involving 167 patients presenting to their FPs between March 1, 2006, and June 30, 2010, with concerns about fatigue.

Main outcome measures

The frequency of psychological and social diagnoses made at the end of visits, and whether diagnoses were made by FPs at the end of the visits versus whether the code for fatigue remained. The associations between patient age, sex, fatigue presenting with other symptoms, or the presence of previous chronic conditions and the outcomes was tested.

Results

Psychosocial diagnoses were made 23.9% of the time. Among psychosocial diagnoses made, depressive disorder and anxiety disorder or anxiety state were diagnosed more often in women (P = .048). Slightly less than 30% of the time, the cause of patients’ fatigue remained undiagnosed at the end of the encounter. A diagnosis was made more often in men.

Conclusion

Causes of fatigue frequently remain undiagnosed; however, when there is a diagnosis, psychosocial diagnoses are common. Therefore, it would be appropriate for FPs to screen for psychosocial issues when their patients present with fatigue, unless some other diagnosis is evident. Depression and anxiety could be considered particularly among female patients with fatigue.

Résumé

Objectif

Établir la fréquence des diagnostics psychosociaux et des autres types de diagnostics au terme d〉une consultation lorsque les patients se présentent chez leur médecin de famille se plaignant de fatigue.

Conception

Étude transversale de consultations de patients auprès de médecins de famille pour cause de fatigue.

Contexte

Dix cliniques de médecine familiale dans le sud-ouest de l’Ontario.

Participants

L’étude portait sur 259 visites impliquant 167 patients ayant consulté leur médecin de famille entre le 1er mars 2006 et le 30 juin 2010 et se plaignant de fatigue.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

La fréquence des diagnostics psychologiques et sociaux posés à la fin de la visite, de même qu’un diagnostic posé par le médecin de famille au terme de la consultation par opposition à un code de fatigue consigné au dossier. Des associations ont été établies entre l’âge du patient, le sexe, la fatigue accompagnée d’autres symptômes ou la présence de problèmes chroniques antérieurs et les résultats.

Résultats

Un diagnostic psychosocial a été posé dans 23,9 % des cas. Parmi les diagnostics psychosociaux, le trouble dépressif, le trouble anxieux ou l’état d’anxiété étaient diagnostiqués plus souvent chez les femmes (p = ,048). Dans un peu moins de 30 % des cas, la cause de la fatigue des patients n’avait pas été diagnostiquée à la fin de la visite. Un diagnostic avait été posé plus souvent chez les hommes.

Conclusion

Les causes de la fatigue demeurent souvent sans diagnostic; par contre, lorsqu’un diagnostic est posé, il est souvent d’ordre psychosocial. Par conséquent, il serait approprié pour les médecins de famille de dépister les problèmes psychosociaux lorsque leurs patients se plaignent de fatigue, à moins que certains autres diagnostics soient évidents. La dépression et l’anxiété pourraient être envisagées, surtout chez les patientes présentant de la fatigue.

The problem of fatigue is common, with a prevalence of 6.0% to 25.0% according to American, British, Dutch, and Australian population studies.1–4 In the United States, the 2-week period prevalence rises to 38%.5

Fatigue is a symptom that presents frequently in family practice, accounting for 5% to 10% of total visits to FPs.6–8 In the Deliver Primary Healthcare Information (DELPHI) database in Canada, it is the third most common symptom presentation for women and the sixth for men.9

Fatigue is also the most common unexplained patient concern, which is defined as a concern for which no diagnosis is made at the first visit.10 There is a relative paucity of studies examining the specific diagnoses arising from patient concern about fatigue or tiredness. The largest studies examining the symptom of fatigue have been carried out in the Netherlands, using the International Classification of Primary Care, revised 2nd edition (ICPC-2-R).11,12 No Canadian studies have identified the range of diagnoses made when patients present to their FPs with fatigue.

Fatigue causes substantial individual disability leading to an estimated annual loss of $136 billion in productive work time in the United States.5 Global dysfunction is similar to that reported for patients with substantial medical illnesses.13 People with fatigue score statistically significantly lower on the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, which contains subscales on physical and emotional role functioning, social functioning, bodily pain, mental health, vitality, and general health.14 Family physicians are challenged to find a standardized approach to dealing with this common yet disabling symptom.

There is an association between fatigue symptoms and psychosocial problems.11,15–19 Patients with fatigue symptoms have greater perceived stress, more pathologic symptom attributions, and greater worries about having emotional problems.15 A diagnosis of depression requires the presence of at least 5 of 9 symptoms, 1 of which is fatigue.20 In other words, fatigue is not necessary or sufficient to diagnose a common psychosocial problem such as depression. Owing to the association with psychosocial problems, it has been suggested that physicians assess fatigued patients for these types of problems.21

Of patients visiting their FPs complaining of fatigue, 64.7% to 73.9% are women, a range that is similar to that for patients without fatigue.2,6,13–15,22–24 Depression presents with neurovegetative symptoms more often in women.25 As fatigue is associated with psychosocial problems, it is possible that psychosocial diagnoses such as depression might be identified more often in women than men when they present with fatigue. However, this has not been studied.

In addition, no Canadian studies were found that analyzed the diagnoses arising from a patient complaint of fatigue. For Canadian patients with fatigue, it was not known whether psychosocial diagnoses were more common than physical diagnoses or whether diagnoses were made at all.

The primary purpose of this study was to elucidate the frequency of psychosocial diagnoses in comparison with physical diagnoses made by Canadian FPs when their patients visit with concerns about fatigue. A secondary purpose was to reveal how often a diagnosis could be made. Additionally, this study aimed to examine whether patient age, sex, fatigue symptoms occurring in isolation, or the presence of a previous chronic disease were associated with the frequency of psychosocial diagnoses or arriving at any diagnosis.

METHODS

Setting

Ten primary care practices situated in southwestern Ontario were studied using encounter data from the DELPHI database. The DELPHI database was developed in 2005 and contains de-identified electronic medical record data.26,27 The database is located at the Centre for Studies in Family Medicine at Western University in London, Ont.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study of encounters with FPs for patients who presented with fatigue. Inclusion criteria were patient encounters for fatigue occurring between March 1, 2006, and June 30, 2010, and a minimum of 6 months after the date of recruitment, among patients older than 18 years of age on March 1, 2006. Exclusion criteria were encounters with FPs who coded inconsistently (consistent coders were defined as those who continued to code at least 80% of the time in the last 2 years of the study period); encounters with FP coders who contributed fewer than 10 encounters for fatigue during the study; and absence of an end-of-visit (EOV) code. These criteria were created to exclude data from physicians who were not consistently using the reason for encounter (RFE) fatigue code for their patients with fatigue.

Sample of physicians

Physician sampling occurred via a 3-pronged approach adapted from that of Borgiel and colleagues28 and described by Stewart et al.27 A total of 23 FPs from 10 group practices who contributed to the database were selected. After applying the exclusion criteria, this was reduced to 8 FPs.

The characteristics of the participating FPs were comparable to those of all southwestern Ontario FPs, demonstrating that the physicians in this study were comprehensive FPs, not focused practitioners.27

Encounter data coded in ICPC-2-R

The FPs coded patient problems using the ICPC-2-R12 for an approximate 10% random sample of their patients. The ICPC-2-R coding provides for multiple stated RFEs and multiple EOV codes based on the FPs’ assessments. The EOV codes include symptoms as well as diagnoses. All FPs were trained and supported closely regarding coding methods to ensure that high-quality data were obtained throughout the development of the DELPHI database.

Sample of patients

Using a random number generator, 2 patients per day were selected from the FPs’ appointment schedules. Patient recruitment ceased after approximately 10% of the patients in each practice were selected. There were only 3 patients of participating FPs who asked to be excluded from the DELPHI extracts. Therefore, the representativeness of patients was high. These encounters generated a total of 3168 patients who represented the sample of patients whose encounters were coded using ICPC-2-R by 23 FPs, before the inclusion criteria were applied.

Variables

The 4 independent variables were age (grouped as 18 to 44 years, 45 to 64 years, and ≥ 65 years), sex, fatigue occurring in isolation versus multiple-symptom encounters, and presence of a chronic disease in the past 6 months. The chronic diseases were identified using a modified version of the tool created by Okkes et al.11

The 2 dependent variables were whether psychosocial diagnoses at the EOV were present or absent; and whether a diagnosis was made versus fatigue remaining as the code at the EOV.

Analysis

The encounter was the unit of analysis; frequency distributions are presented. Multivariable tests of significance (of 4 independent variables in relation to 2 outcomes) were calculated using logistic regression with basic adjustment for clustering of encounters within patients, as some patients had more than 1 symptom and encounter. The multivariable analysis, including adjustment for clustering, was accomplished using STATA software.

Ethics

The DELPHI project was approved by the Review Board for Health Sciences Research Involving Human Subjects at Western University.

RESULTS

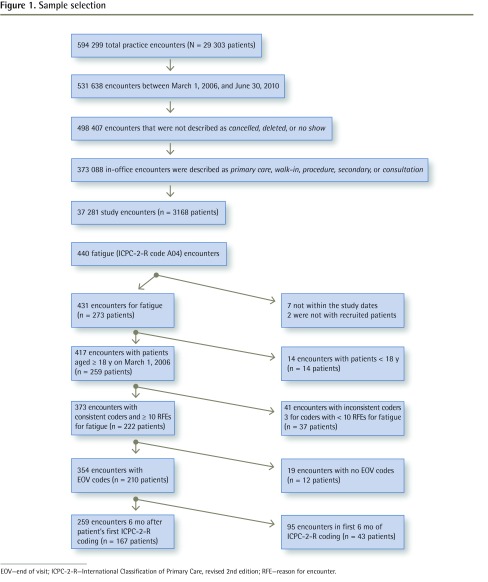

Figure 1 shows the sample selection of the encounters in this study. This illustrates that of the 3168 DELPHI patients (shown in row 5 of Figure 1), FPs coded 431 patient encounters that had fatigue as 1 of the RFEs within the study dates. After some patients and some encounters were eliminated using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 259 encounters and 167 patients remained.

Figure 1.

Sample selection

EOV—end of visit; ICPC-2-R—International Classification of Primary Care, revised 2nd edition; RFE—reason for encounter.

Table 1 shows the frequency of the characteristics of the encounters. The largest proportion of encounters involved individuals 65 years of age and older and the smallest involved those younger than 45 years; there were more encounters with women than with men; fatigue as the only symptom for the RFE occurred less than half of the time; and 86.9% of encounters occurred in patients who had a previous chronic condition.

Table 1.

Frequency of independent variables for fatigue encounters: N = 259.

| VARIABLE | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| • 18–44 | 39 (15.1) |

| • 45–64 | 85 (32.8) |

| • ≥ 65 | 135 (52.1) |

| Sex | |

| • Female | 179 (69.1) |

| • Male | 80 (30.9) |

| Fatigue as only reason for encounter | |

| • Yes | 115 (44.4) |

| • No | 144 (55.6) |

| Previous chronic condition | |

| • Present | 225 (86.9) |

| • Absent | 34 (13.1) |

Table 2 displays EOV ICPC-2-R disease chapters or body systems according to ICPC-2-R code in order of frequency for fatigue patients. Circulatory diagnoses are the most common, general and unspecified diagnoses are second, and combined psychological and social problems are third.

Table 2.

Frequencies of ICPC-2-R chapters in EOV symptom and diagnosis codes, arising from the RFE of fatigue: N = 259 encounters; total EOV code frequency (N = 533) includes codes for chapters that are not shown, as they were recorded in < 5 encounters.

| CHAPTER | CHAPTER TITLE | FREQUENCY OF CHAPTER DIAGNOSIS AT EOV* | ENCOUNTERS,* % |

|---|---|---|---|

| K | Circulatory | 117 | 45.2 |

| A04 | General weakness or tiredness remains as a symptom | 77 | 29.7 |

| P and Z | Psychological and social problems, combined | 62† | 23.9† |

| T | Endocrine, metabolic, or nutritional | 53 | 20.5 |

| P | Psychological | 49 | 18.9 |

| R | Respiratory | 47 | 18.1 |

| L | Musculoskeletal | 46 | 17.8 |

| D | Digestive | 28 | 10.8 |

| A | General or unspecified, other than A04 | 20 | 7.7 |

| N | Neurologic | 19 | 7.3 |

| U | Urinary system | 16 | 6.2 |

| B | Blood, blood-forming organs, or immune mechanism | 15 | 5.8 |

| S | Skin | 14 | 5.4 |

| Z | Social problems | 13 | 5.0 |

| X | Female genital system including breast | 7 | 2.7 |

| H | Ear | 5 | 1.9 |

EOV—end of visit; ICPC-2-R—International Classification of Primary Care, revised 2nd edition; RFE—reason for encounter.

Totals are greater than 259 and 100.0% because some encounters have > 1 EOV code.

P and Z combined values were not included in the EOV code total.

Table 3 displays the EOV ICPC-2-R diagnostic codes (distinct from disease chapters) in order of frequency. The most common EOV code is A04 (general weakness or tiredness; ie, fatigue remaining undiagnosed) at 29.7%.

Table 3.

Frequency of EOV symptom and diagnosis ICPC-2-R codes, arising from the RFE of fatigue: N = 259 encounters; total EOV code frequency (N = 533) includes codes not shown, as they were recorded in < 5 encounters.

| CODE | NAME | FREQUENCY OF EOV CODES* | ENCOUNTERS,* % |

|---|---|---|---|

| A04 | Weakness or tiredness, general | 77 | 29.7 |

| K86 | Hypertension, uncomplicated | 52 | 20.1 |

| T90 | Diabetes, non–insulin dependent | 33 | 12.7 |

| P76 | Depressive disorder | 20 | 7.7 |

| K78 | Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 15 | 5.8 |

| P74 | Anxiety disorder or anxiety state | 12 | 4.6 |

| R74 | Upper respiratory infection, acute | 12 | 4.6 |

| A85 | Adverse effect, medical agent | 11 | 4.2 |

| K74 | Ischemic heart disease with angina | 10 | 3.9 |

| K76 | Ischemic heart disease without angina | 10 | 3.9 |

| R81 | Pneumonia | 9 | 3.5 |

| B82 | Anemia, other or unspecified | 8 | 3.1 |

| L17 | Foot or toe symptom or complaint | 6 | 2.3 |

| P06 | Sleep disorder | 6 | 2.3 |

| R95 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6 | 2.3 |

| T86 | Hypothyroidism or myxedema | 6 | 2.3 |

| T93 | Lipid disorder | 6 | 2.3 |

EOV—end of visit; ICPC-2-R—International Classification of Primary Care, revised 2nd edition; RFE—reason for encounter.

Totals are greater than 259 and 100.0% because some encounters have > 1 EOV code.

Logistic regression revealed that none of the 4 independent variables were associated with the EOV chapter of psychological or social problems. Although sex was not related to the frequency of psychosocial diagnoses, Table 4 shows the results of a post hoc analysis indicating that there was a significant difference between sexes regarding a subset of psychological problems (P = .048). Depressive disorder and anxiety disorder or anxiety state were more common diagnoses made for women (73.0% of the time) while other psychological diagnoses were more common for men (58.3% of the time).

Table 4.

End-of-visit psychosocial code subset for depressive disorder and anxiety disorder, by sex: = .920, P = .048.

| SEX | DEPRESSIVE DISORDER AND ANXIETY DISORDER OR ANXIETY STATE, N (%) | OTHER PSYCHOSOCIAL DIAGNOSES, N (%) | TOTAL, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 27 (73.0) | 10 (27.0) | 37 (100.0) |

| Male | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | 12 (100.0) |

| Total | 32 (65.3) | 17 (34.7) | 49 (100.0) |

Table 5 shows the logistic regression analysis for the dependent variable of cause of fatigue diagnosed by the EOV, revealing that there were no significant differences. Table 6 shows the bivariable sex analysis, illustrating that a diagnosis was made more often in men.

Table 5.

Fatigue code remaining versus a diagnosis made at the EOV, by independent variable

| VARIABLE | ODDS OF FATIGUE CODE REMAINING AT EOV | STANDARD ERROR |

|---|---|---|

| Age 45–64 y | 0.588* | 0.299 |

| Age ≥ 65 y | 0.657* | 0.327 |

| Female sex | 1.981† | 0.711 |

| Fatigue symptom was only RFE | 1.177 | 0.304 |

| Previous chronic condition | 1.255 | 0.530 |

EOV—end of visit, RFE—reason for encounter.

Age 18–44 y was the reference group.

Logistic regression, P < .1.

Table 6.

Relationship between sex and whether a diagnosis was made versus fatigue code remaining at EOV: = 5.245, P = .05.

| SEX | DIAGNOSIS CODED AT EOV | FATIGUE CODED AT EOV | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 118 (65.9) | 61 (34.1) | 179 (100.0) |

| Male | 64 (80.0) | 16 (20.0) | 80 (100.0) |

| Total | 182 (70.3) | 77 (29.7) | 259 (100.0) |

EOV—end of visit.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first Canadian study to examine diagnoses arising from concerns about fatigue. The primary purpose of this study was to gain insight into psychosocial diagnoses made when patients present to FPs with fatigue.

Psychosocial diagnoses were made 23.9% of the time, reaffirming the frequent coexistence of these diagnoses and fatigue. These diagnoses were more frequent than diagnoses of many common physical diseases. Although there was no difference between sexes regarding the presence of a psychosocial diagnosis at the EOV, there was a difference regarding the type of psychosocial diagnoses made by FPs, with depressive disorder and anxiety disorder or anxiety state diagnosed more often in women and other psychosocial problems diagnosed more often in men. The reasons for this are unclear. A possible explanation is that depression and anxiety present differently in women than men. Alternatively, men might present less often to their physicians for psychosocial problems. Finally, there is the possibility that physician perspectives regarding sex are a factor. This new finding requires further research.

The large proportion of encounters regarding fatigue for female and senior patients is similar to other studies.2,6,13,14,22,23 Fatigue remained undiagnosed slightly less than 30% of the time, compared with findings in the United States and Europe in which 28% to 43% of the cases of fatigue remained undiagnosed.13,18,23,24,29–32 A diagnosis was made more often when the patient was male. The reasons for this are unclear and require further study.

The results of this study suggest that when diagnosing patients with fatigue, FPs should consider underlying psychosocial problems, particularly depression and anxiety among their female patients. A diagnosis was made more often for men. For physical diagnoses other than pre-existing chronic diseases, physicians should consider infectious diseases and medication side effects. Blood tests are not necessarily required to make a diagnosis, as anemia and hypothyroidism are less common.

Limitations

This was a real-world, practice-based study and physicians were not asked to collect a lot of data, merely to code using the ICPC-2-R, which mandates that all EOV codes are included. Therefore, this study could not discern what clinicians thought were the precise diagnoses for fatigue. Further studies examining symptom presentations could instruct physician coders to specifically link an EOV categorization to the fatigue symptom.

An attempt was made to reduce the percentage of encounters in which a previous chronic disease was present. In spite of this, 86.9% of study encounters were for patients with a previous chronic disease. This must be considered when interpreting the results.

The diagnosis for a patient’s fatigue might not have been revealed at the first visit. We recommend a future longitudinal study. Such a quantitative study would need to identify a link between fatigue encounters.

Conclusion

Fatigue is common and disabling, and frequently remains undiagnosed; however, when there is a diagnosis, psychosocial diagnoses are frequent. Therefore, it would be appropriate for FPs to screen for psychosocial issues when their patients present with fatigue, unless another diagnosis is evident. Depression and anxiety should be considered, particularly among female patients with fatigue.

Acknowledgments

The DELPHI (Deliver Primary Healthcare Information) project was funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Primary Health Care Transition Fund, and the Enhancing Quality Management in Primary Care Initiative of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Dr Stewart is funded by the Dr Brian W. Gilbert Canada Research Chair in Primary Health Care Research.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Psychosocial diagnoses were made for 23.9% of patients presenting with fatigue, reaffirming the frequent coexistence of these diagnoses and fatigue. Psychosocial diagnoses were more frequent than diagnoses of many common physical diseases.

Fatigue remained undiagnosed slightly less than 30% of the time. A diagnosis was made more often when the patient was male. Depressive disorder and anxiety disorder or anxiety state were diagnosed more often in women and other psychosocial problems were diagnosed more often in men.

When diagnosing patients with fatigue, FPs should consider underlying psychosocial problems, particularly depression and anxiety among their female patients.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Chez des patients se plaignant de fatigue, des diagnostics psychosociaux ont été posés dans 23,9 % des cas, ce qui confirme la coexistence fréquente de tels diagnostics et de la fatigue. Les diagnostics psychosociaux étaient posés plus souvent que celui de nombreuses autres maladies physiques courantes.

Dans un peu moins de 30 % des cas, la cause de la fatigue n’a pas été diagnostiquée. Le diagnostic était posé plus souvent chez les hommes. Le trouble dépressif, le trouble anxieux ou l’état d’anxiété était diagnostiqué plus souvent chez les femmes tandis que d’autres problèmes psychosociaux étaient diagnostiqués plus fréquemment chez les hommes.

Lorsque les médecins de famille posent un diagnostic dans un cas de fatigue, ils devraient envisager des problèmes psychosociaux sousjacents, en particulier la dépression et l’anxiété chez leurs patientes.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Lawrie SM, Manders DN, Geddes JR, Pelosi AJ. A population-based incidence study of chronic fatigue. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):343–53. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawlikowska T, Chalder T, Hirsch SR, Wallace P, Wright DJ, Wessely SC. Population based study of fatigue and psychological distress. BMJ. 1994;308(6931):763–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenter EG, Okkes IM. Patients with fatigue in family practice: prevalence and treatment [article in Dutch] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1999;143(15):796–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickie IB, Hooker AW, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Bennett BK, Wilson AJ, Lloyd AR. Fatigue in selected primary care settings: sociodemographic and psychiatric correlates. Med J Aust. 1996;164(10):585–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb122199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricci JA, Chee E, Lorandeau AL, Berger J. Fatigue in the U.S. workforce: prevalence and implications for lost productive work time. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(1):1–10. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000249782.60321.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullen W, Kearney Y, Bury G. Prevalence of fatigue in general practice. Ir J Med Sci. 2002;171(1):10–2. doi: 10.1007/BF03168931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson E, Kirk J, McHugo G, Douglass R, Ohler J, Wasson J, et al. Chief complaint fatigue: a longitudinal study from the patient’s perspective. Fam Pract Res J. 1987;6(4):175–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharpe M, Wilks D. Fatigue. BMJ. 2002;325(7362):480–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7362.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed S, Chevendra V, Marshall JN, Stewart M, Terry AL, Thind A. Describing the workload of primary care providers: results from the use of the International Classification of Primary Care in the DELPHI project. Presented at: 2007 North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting; 2007 Jun 22; Vancouver, BC. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch H, van Bokhoven MA, ter Riet G, Hessels KM, van der Weijden T, Dinant GJ, et al. What makes general practitioners order blood tests for patients with unexplained complaints? A cross-sectional study. Eur J Gen Pract. 2009;15(1):22–8. doi: 10.1080/13814780902855762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okkes IM, Oskam SK, Lamberts H. The Amsterdam Transition Project. Amsterdam, Neth: Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Department of Family Medicine; 2005. ICPC. [CD-ROM]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WONCA International Classification Committee . International Classification of Primary Care. Revised 2nd ed. Oxford, Engl: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroenke K, Wood DR, Mangelsdorff AD, Meier NJ, Powell JB. Chronic fatigue in primary care. Prevalence, patient characteristics, and outcome. JAMA. 1988;260(7):929–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nijrolder I, van der Windt DA, van der Horst HE. Prognosis of fatigue and functioning in primary care: a 1-year follow-up study. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(6):519–27. doi: 10.1370/afm.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cathébras PJ, Robbins JM, Kirmayer LJ, Hayton BC. Fatigue in primary care: prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity, illness behaviour and outcome. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(3):276–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02598083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dick ML, Sundin J. Psychological and psychiatric causes of fatigue. Assessment and management. Aust Fam Physician. 2003;32(11):877–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Jackson JL. Outcome in general medical patients presenting with common symptoms: a prospective study with a 2-week and a 3-month follow-up. Fam Pract. 1998;15(5):398–403. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.5.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridsdale L, Evans A, Jerrett W, Mandalia S, Osler K, Vora H. Patients who consult with tiredness: frequency of consultation, perceived causes of tiredness and its association with psychological distress. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44(386):413–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward MH, DeLisle H, Shores JH, Slocum PC, Foresman BH. Chronic fatigue complaints in primary care: incidence and diagnostic patterns. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1996;96(1):34–46. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.1996.96.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godwin M, Delva D, Miller K, Molson J, Hobbs N, MacDonald S, et al. Investigating fatigue of less than 6 months’ duration. Guideline for family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:373–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridsdale L, Evans A, Jerrett W, Mandalia S, Osler K, Vora H. Patients with fatigue in general practice: a prospective study. BMJ. 1993;307(6896):103–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6896.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valdini AF, Steinhardt S, Valicenti J, Jaffe A. A one-year follow-up of fatigued patients. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(1):33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirk J, Douglass R, Nelson E, Jaffe J, Lopez A, Ohler J, et al. Chief complaint of fatigue: a prospective study. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(1):33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dekker J, Koelen JA, Peen J, Schoevers RA, Gijsbers-van Wijk C. Gender differences in clinical features of depressed outpatients: preliminary evidence for subtyping of depression? Women Health. 2007;46(4):19–38. doi: 10.1300/j013v46n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centre for Studies in Family Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry . DELPHI: Deliver Primary Healthcare Information. London, ON: Western University; 2005. Available from: www.schulich.uwo.ca/familymedicine/research/csfm/research/current_projects/delphi.html. Accessed 2016 Jul 12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart M, Thind A, Terry AL, Chevendra V, Marshall JN. Implementing and maintaining a researchable database from electronic medical records: a perspective from an academic family medicine department. Health Policy. 2009;5(2):26–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borgiel AE, Dunn EV, Lamont CT, MacDonald PJ, Evensen MK, Bass MJ, et al. Recruiting family physicians as participants in research. Fam Pract. 1989;6(3):168–72. doi: 10.1093/fampra/6.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenter EG, Okkes IM, Oskam SK, Lamberts H. Tiredness in Dutch family practice. Data on patients complaining of and/or diagnosed with “tiredness.”. Fam Pract. 2003;20(4):434–40. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elnicki DM, Shockcor WT, Brick JE, Beynon D. Evaluating the complaint of fatigue in primary care: diagnoses and outcomes. Am J Med. 1992;93(3):303–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison JD. Fatigue as a presenting complaint in family practice. J Fam Pract. 1980;10(5):795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugarman JR, Berg AO. Evaluation of fatigue in a family practice. J Fam Pract. 1984;19(5):643–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]