Abstract

Introduction

Links between childhood residential mobility and multiple adverse outcomes through to maturity, and effect modification of these associations by familial SES, are incompletely understood.

Methods

A national cohort of people born in Denmark in 1971–1997 were followed from their 15th birthdays until their early forties (N=1,475,030). Residential moves during each age year between birth and age 14 years were examined, with follow-up to 2013. Incidence rate ratios for attempted suicide, violent criminality, psychiatric illness, substance misuse, and natural and unnatural deaths were estimated. The analyses were conducted during 2014–2015.

Results

Elevated risks were observed for all examined outcomes, with excess risk seen among those exposed to multiple versus single relocations in a year. Risks grew incrementally with increasing age of exposure to mobility. For violent offending, attempted suicide, substance misuse, and unnatural death, sharp spikes in risk linked with multiple relocations in a year during early/mid-adolescence were found. With attempted suicide and violent offending, the primary outcomes, a distinct risk gradient was observed with increasing age at exposure across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Conclusions

The links between childhood residential mobility and negative outcomes in later life appear widespread across multiple endpoints, with elevation in risk being particularly marked if frequent residential change occurs during early/mid-adolescence. Heightened vigilance is indicated for relocated adolescents and their families, with a view to preventing longer-term adverse outcomes in this population among all socioeconomic groups. Risk management will require close cooperation among multiple public agencies, particularly child, adolescent, and adult mental health services.

Introduction

Residential mobility occurs commonly in developed countries. The U.S., for instance, has been a mobile society for generations. In the early 1950s, around a fifth of its population moved annually1 and during 2014, more than 11% of Americans relocated.2 Although this topic has been researched since the early post-war years,1 the impact of residential transience during childhood remains incompletely understood. It has been examined from various perspectives: health scientists have studied psychopathology, substance misuse, and suicide,3, 4, 5 whereas social scientists have reported on well-being,6 social capital,7 behavioral,8 and educational outcomes.9

Multiple approaches have been applied in measuring mobility, including total number of relocations, time since last move, and time in current residence.3 Most studies have not specifically examined moves between municipalities or cities or distance moved.3 Investigators have relied on subject self-reported exposure status,10 which could be affected by recall bias, especially if residential changes occurred often or at an early age. Attrition bias, with loss to follow-up more likely for transient families, is another common limitation.3 Register-based studies have not been subject to these biases, but they have tended to report on a single outcome like severe mental illness.4 Multiple interrelated adverse outcomes, with complete follow-up from adolescence to early middle age, have not been reported. It is also unclear how risks vary by familial SES, which has often been treated as a confounder11 rather than an effect modifier, or the research focus has been solely on low-income families.12, 13

This national cohort examined risks across three adverse outcome domains:

-

1

Self-directed and interpersonal violence: attempted suicide, violent criminality;

-

2

Mental illness and substance misuse: any psychiatric diagnosis, substance misuse; and

-

3

Premature mortality: natural and unnatural deaths.

Injury is the leading cause of death between childhood and middle age in Europe.14 For a program of work funded by the European Research Council, the authors investigated an array of fatal and nonfatal outcomes that reflect self-destructive, hazardous, and violent behavior in younger people to better understand their determinants. For comparative purposes, natural deaths were also examined. Relative risk was estimated against people unexposed to residential mobility, and strength of association was assessed by age at exposure from birth through mid-adolescence and by relocation frequency during each age year of upbringing. It was hypothesized that relocated children from lower-SES families would have higher relative risks, as families of higher SES may more frequently move in a controlled manner to attain improved employment or to access better housing or schooling, whereas those of lower SES may more often make unplanned or chaotic moves, owing to acute financial crises or threats.

Methods

All people born in Denmark to Danish-born parents during 1971–1997, who were residing in the country on their 15th birthday, were examined (N=1,475,030). Unique personal identification numbers in the Civil Registration System enabled virtually complete inter-register and parent–offspring linkage.15 Follow-up was from 15th birthday until adverse outcome (including death), emigration, or the final observation date, whichever came first. These final observation dates varied according to outcome data availability: December 31, 2011, for cause-specific mortality; December 31, 2012, for attempted suicide and violent crime conviction; and December 31, 2013, for any psychiatric disorder and substance misuse. The analyses were conducted during 2014–2015.

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (file 2013-41-2265), and data access was agreed by the State Serum Institute and Statistics Denmark (FSE ID 820). In accordance with the Danish Act on Processing of Personal Data, Section 10, cohort members’ informed consent was not required.

Measures

Frequency of relocation across municipal boundaries was calculated for each age year between birth and 15th birthday4 and this study also determined the aggregate number of moves between these two time points. Intra-municipality movement was not measured, thereby precluding dilution of exposure by including moves on the same street or one nearby, and distance of relocation was also not examined. Restructuring in 2007 reduced the number of municipalities from 276 to 96. The data were transformed to the pre-2007 structure to enable consistent exposure classification throughout the study period (mean municipality population size, 19,926 residents; mean surface area, 156 km2).

Since 1980, the National Crime Register has recorded all charges and convictions.16 Interpersonal violent crime was defined as encompassing convictions for homicide, attempted homicide, assault, robbery, aggravated burglary or arson, possessing a weapon in a public place, violent threats, extortion, human trafficking, abduction, kidnapping, rioting, terrorism, and all sexual offenses (except possession of child pornographic material). Hospital-treated suicide attempts were identified from the Psychiatric Central Research Register17 and the National Patient Register.18, 19

Cohort members’ mental illness histories, as well as those of their parents and siblings, were obtained from the Psychiatric Central Research Register. From 1969, this has captured all psychiatric admissions, with information on outpatients also included since 1995. The ICD was applied: 8th revision (ICD-8)20 1969–1993; ICD-10 from 1994.21 Onsets of any psychiatric disorder (ICD-10, F00–F99; ICD-8, 290–315) and alcohol or drug misuse disorders (ICD-10, F10–F19; ICD-8, 291.x9, 294.39, 303.x9, 303.20, 303.28, 303.90, 304.x9) were delineated by first diagnosis date.

To measure premature mortality, unnatural (ICD-8, E800–E999; ICD-10, V01–Y89) and natural deaths (all other ICD mortality codes) were extracted from the Register of Causes of Death.22 Parental SES data were obtained from the Integrated Database for Labor Market Research.23 Parental SES was measured in the year of cohort members’ 15th birthdays as follows:

-

1.

Income (annual quintiles);

-

2.

Highest educational attainment level (primary school, high school/vocational training, higher education); and

-

3.

Employment status (employed, unemployed, outside workforce for other reasons).

To examine confounding, these three maternal/paternal SES variables were fitted separately in multivariable models (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3). For the stratified models (Figure 4), the following composite parental SES variable was applied:

-

1.

“Lower”—Both parents score low in at least one of the three domains: income=lowest quintile; highest education=primary school; employment status=outside the workforce.

-

2.

“Higher”—Mother and father both employed and score high in at least one of the other two domains: income=highest quintile; education=higher education.

-

3.

“Middle”—All other combinations.

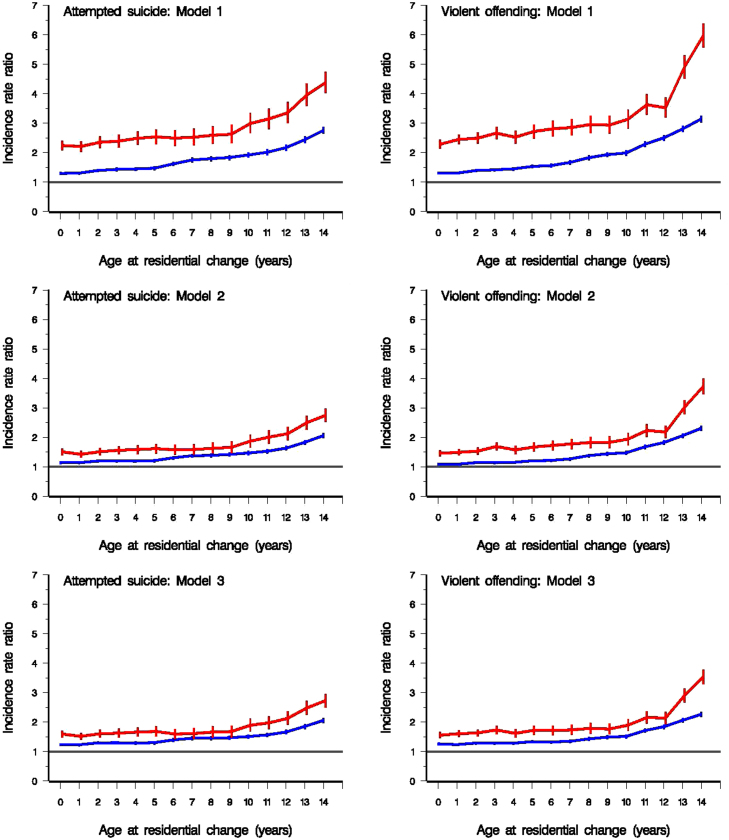

Figure 1.

IRRs for attempted suicide and violent criminal offending associated with residential mobility during each age year of childhood.

Note: Blue line=single residential move in an age year of childhood; red line=multiple residential moves in a year. Model 1: IRRs adjusted for age, gender, and calendar year. Model 2: IRRs adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, parental age, degree of urbanization at cohort member’s birth, and history of mental illness in a parent or sibling. Model 3: IRRs adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, and parental SES.

IRR, incidence rate ratio.

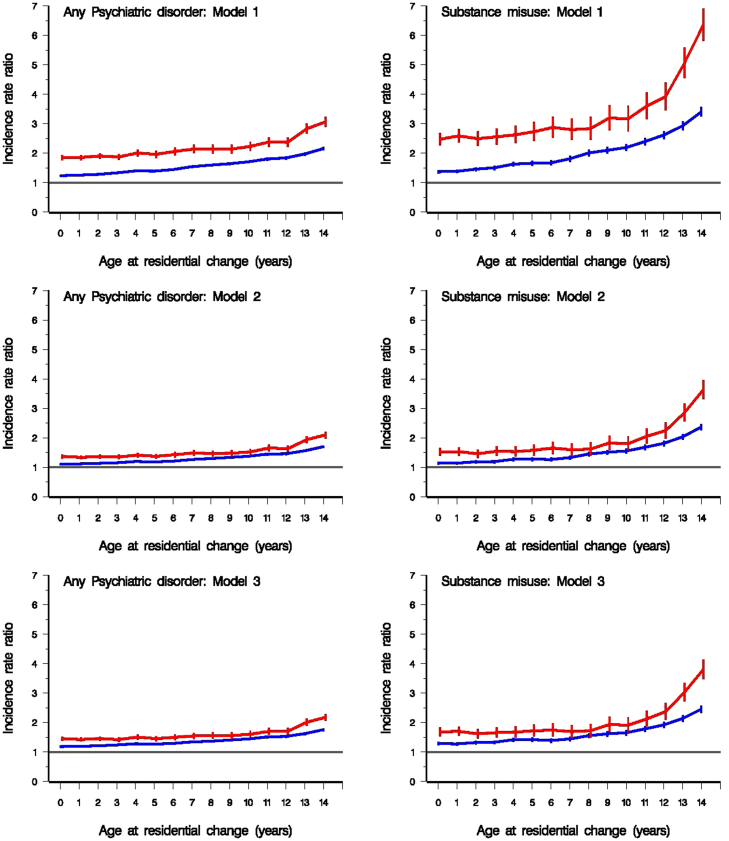

Figure 2.

IRRs for any psychiatric disorder and substance misuse associated with residential mobility during each age year of childhood.

Note: Blue line=single residential move in an age year of childhood; red line=multiple residential moves in a year. Model 1: IRRs adjusted for age, gender and calendar year. Model 2: IRRs adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, parental age, degree of urbanization at cohort member’s birth, and history of mental illness in a parent or sibling. Model 3: IRRs adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, and parental SES.

IRR, incidence rate ratio.

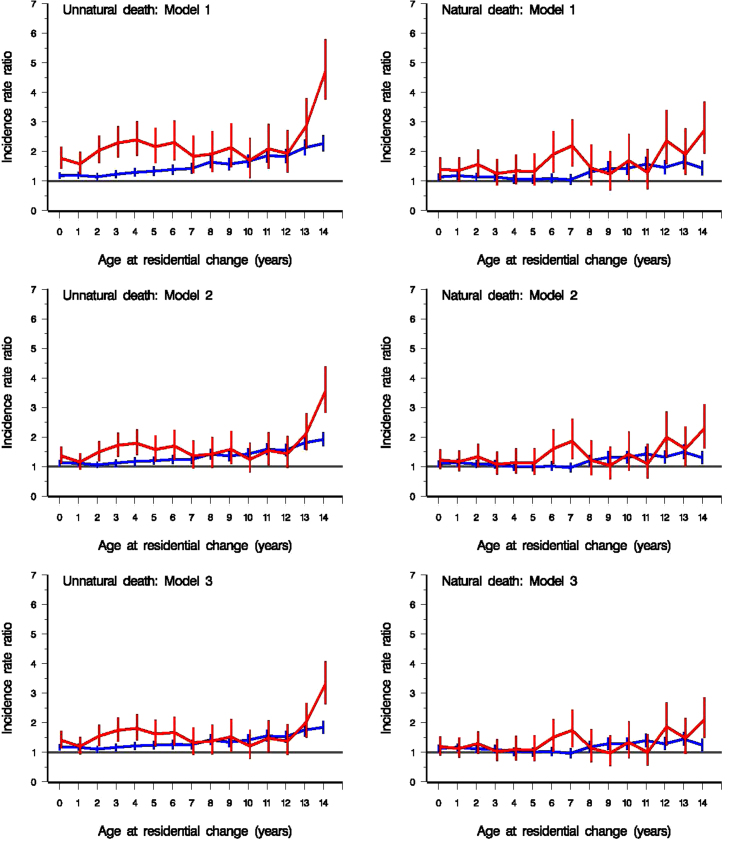

Figure 3.

IRRs for unnatural and natural mortality associated with residential mobility during each age year of childhood.

Note: Blue line=single residential move in an age year of childhood; red line=multiple residential moves in a year. Model 1: IRRs adjusted for age, gender, and calendar year. Model 2: IRRs adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, parental age, degree of urbanization at cohort member’s birth, and history of mental illness in a parent or sibling. Model 3: IRRs adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, and parental SES.

IRR, incidence rate ratio.

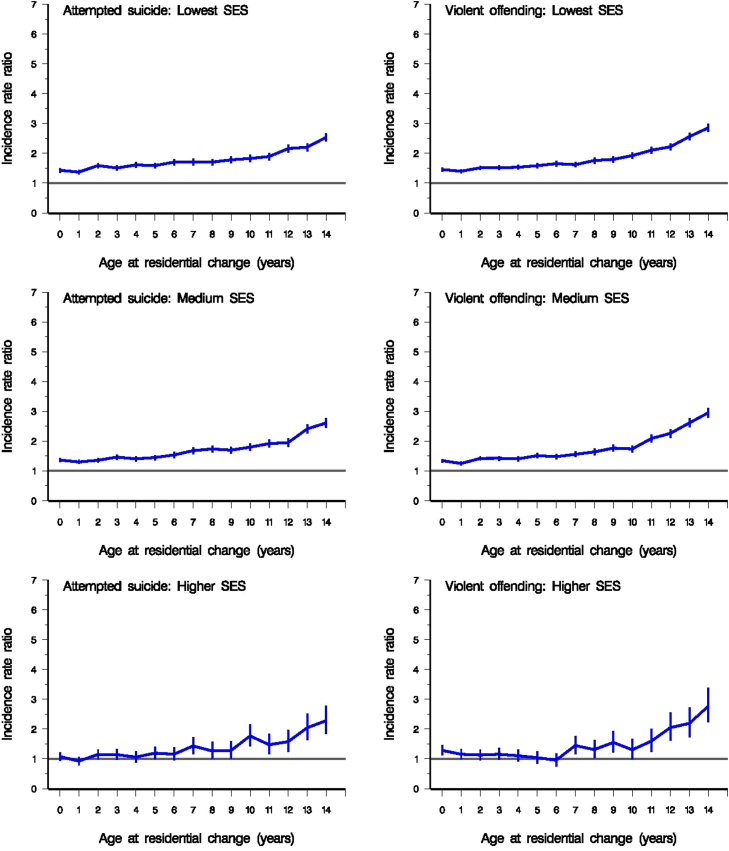

Figure 4.

IRRs for attempted suicide and violent criminal offending stratified by parental SES strata.

Note: Blue line=at least one residential move in an age year of childhood. IRRs were adjusted for age, gender, and calendar year.

IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Statistical Analysis

Poisson regression models were fitted using the SAS, version 9.2, GENMOD procedure, with the logarithms of the aggregated person-years counts set as offset variables. This is equivalent to the Cox proportional hazards model, assuming piecewise constant incidence rates.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 The generic reference category consisted of children who did not move during each age year observed. All incidence rate ratio (IRR) estimates were adjusted for age, gender, and calendar year. Further adjustments were made for

-

1.

urbanicity at birth,32 parental age at birth, history of mental disorder in a parent or sibling; and

-

2.

parental SES.

Age during follow-up, calendar year, and family psychiatric history were included as time-varying covariates; gender, parental age, urbanicity, and parental SES were time fixed. Likelihood ratio–based 95% CIs and interaction tests were calculated. A detailed explanation of how cohort members’ ages were analyzed is provided in the Appendix (Section 1, available online).

Results

Thirty-seven percent of cohort members relocated across a municipal boundary at least once before reaching their 15th birthdays. Appendix Figure 1 (available online) shows the frequency of residential moves by age at exposure. Moving just once in a year was relatively common, especially in early childhood. Thus, during the first year of life, 7.3% of the cohort moved once compared with 2.6% at age 14 years. Moving twice or three or more times in a year was uncommon. Again, multiple relocations occurred most frequently during infancy; 0.8% of the cohort moved twice and 0.1% moved three times or more in the first year of life. These values decreased with rising age. On the basis of these plots, and given the rarity of the examined outcomes, exposure for IRR estimation was classified as one versus two or more moves in a year.

In this and the next two sections, IRRs adjusted for age, gender, and calendar year are reported. Figure 1 (Model 1) plots IRRs for attempted suicide and violent offending associated with single or multiple relocations in a year from birth to 15th birthday. Attempted suicide risk was significantly elevated in relation to each exposure period and for one as well as multiple moves in a year. Risk increased steadily with rising age at exposure, and was markedly raised if multiple annual relocations occurred at ages 12–14 years. For all exposure periods, risk was greater with multiple moves versus a single move, as indicated by the non-overlapping CIs for the two sets of IRRs. The pattern of association between childhood mobility and later violent offending showed the same trends, except for an even sharper spike in risk with exposure to multiple relocations in a year during mid-adolescence than was observed in relation to attempted suicide risk.

Risk of developing psychopathology increased gradually across the age year exposure periods, with either one or multiple relocations (Figure 2, Model 1). The observed associations were weaker than for attempted suicide and violent offending, and there was no steep gradient of rising risk linked with mobility during early/mid-adolescence. The observed associations for substance misuse were of a greater strength than they were for any psychiatric disorder, and the IRRs indicated a sharp spike in risk linked with exposure at ages 12–14 years.

Figure 3 (Model 1) shows that for all natural deaths, single relocations in a year at ages 0–3 years were linked with a marginally increased risk, but there was no elevation in risk with exposure at ages 4–7 years. Mobility at ages 8–14 years was linked with modestly raised IRRs. Relative risks for natural death associated with multiple relocations in a year were somewhat higher. However, the CIs for these IRRs overlapped with those linked with a single move, with the exception of exposure at ages 6, 7, and 14 years.

Unnatural mortality risk was significantly elevated, albeit only slightly, if a child moved once in a year before its second birthday. The strength of association with a single relocation increased incrementally across the age year exposure periods. Relative risk of unnatural death associated with multiple moves in a year was much higher than with single relocations. This differential for exposure to multiple versus single moves was pronounced at ages 2–6 years. With exposure at ages 7–12 years, the risk elevations were quite similar whether children moved once or several times in a year. A sharp spike in risk was observed with multiple moves at ages 13–14 years. Across all the age year exposure periods, the relative risks for both single and multiple relocations were consistently greater for unnatural versus natural deaths.

Further adjustments for parental age, urbanization, and psychiatric history in a parent or sibling, and for parental SES, are shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 (Models 2 and 3, respectively). Consistently across all six adverse outcomes, these additional adjustments partially attenuated the observed associations, and they also narrowed the risk differentials with exposure to multiple versus single moves in a year. However, for each outcome, the pattern of increasing relative risk with rising age at exposure to relocation persisted.

Gender-specific associations are presented in Appendix Section 3 (available online). The elevation in violent offending risk was considerably greater in females versus males exposed to residential mobility at age 14 years. Figure 4 shows relative risk for attempted suicide and violent offending linked with at least one residential move in a year, stratified by parental SES. For both of these primary outcomes, quite similar associations were observed across SES strata. However, some specific differences merit detailed consideration. In the lower and middle SES strata, residential mobility before age 7 years was linked with modest elevations in risk that became pronounced as age at exposure to relocation increased. In the higher SES stratum, a slightly different pattern was found. For mobility before age 7 years, there was little evidence of subsequent increased risk. However, among higher-SES cohort members who moved at age 7 years or older, the elevated risks observed were in line with the equivalent IRR estimates for the middle and lower SES strata. Section 4 of the Appendix (available online) contains further exploration of these analyses.

For the analyses presented in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, a critical period approach was taken in measuring exposure to mobility during each childhood age year. The cumulative number of relocations through upbringing was also examined (Appendix Section 5, available online). Across all six considered adverse outcomes, the highest risks were among cohort members who moved frequently before their 15th birthday. “Dose–response” relationships were evident for all outcomes in that each additional move was associated with an incremental risk increase.

Discussion

Across all six adverse outcomes examined, a generally consistent pattern of long-term risk elevation was found between mid-adolescence and early middle age in relation to residential mobility during upbringing. For each endpoint, there were excess risks linked with exposure to multiple versus single moves in a year, and risks rose incrementally in a dose–response fashion with increasing number of total moves during upbringing and also with rising age at relocation. For violent offending, attempted suicide, substance misuse, and unnatural death, there was a sharp spike in risk linked with multiple moves in a year during early/mid-adolescence. Adjustment for parental age and urbanization at birth, familial mental illness, and parental SES partially explained the observed elevated risks. Stratification of the IRRs for attempted suicide and violent offending by parental SES revealed markedly elevated risk with increasing age at exposure across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Owing to its uniquely complete and accurate registration of all residential changes in its population, Denmark is the only country where it is currently possible to conduct such a comprehensive national investigation of childhood residential mobility and risk of adverse outcomes in later life. Statistical power was abundant for examining rare exposure–outcome relationships and gender interactions, and for stratifying relative risk by SES. National registry data enabled full ascertainment of secondary care treated mental illnesses and attempted suicides, all violent crime convictions, and all natural and unnatural deaths, as well as comprehensive right censoring for death or emigration.

The findings concur with previous studies that have reported elevated risks of suicidality,5 violence,33 psychopathology,34, 35 substance misuse,5 and premature death.36 More specifically, and consistent with existing evidence,12 this study indicates that the link between residential relocation and adverse outcomes is especially marked when moves occur during early/mid-adolescence. The published literature, however, cannot be used to compare risk across multiple outcomes because each study generally reports a single endpoint only, whereas in this national registry study, direct comparison across outcomes was possible. A further restriction to the scope of previous research is that very few studies report longer-term outcomes beyond childhood and adolescence.11 These major gaps in the evidence base illustrate the utility of this study in quantifying risk patterns by age and frequency of exposure through childhood linked with multiple adverse outcomes followed up to early middle age.

Frequent residential moves may be a marker for family dysfunction and chaotic households.37, 38 Residential changes also often result in disruption of social ties. In this study, measurement of mobility included only those residential relocations that transcended municipal boundaries. For Danish children aged 7 years and older, such moves would usually also require a school transfer. Relocated adolescents often face a double stress of adapting to an alien environment, a new school, and building new friendships and social networks, while simultaneously coping with the fundamental biological and developmental transitions that their peers also experience.39

Markedly elevated risk linked with exposure to residential mobility during early/mid-adolescence was not restricted to lower-SES families, and stratified analyses of this nature have not been reported previously. This finding perhaps indicates that the mechanisms implicated in adverse outcome may be at least partially causal. In theory, the association between exposure to childhood residential mobility and subsequent adverse outcome could be confounded by multiple interrelated antecedents,10 and it could also be restricted to lower-income households where psychosocial difficulties cluster strongly. These novel stratified analyses indicate that this notion appears not to hold true, and that, in higher-SES families, elevated risk is linked with exposure to mobility during middle childhood and early/mid-adolescence. Absence of elevated risk in relation to residential mobility before age 7 years in the higher SES stratum may reflect aspirational residential movements for better employment, housing, and schooling opportunities before children formally enter the educational system. Residential mobility among older children, even in more-affluent households, may occur in parallel with severe family stressors such as parental separation.13, 36

Limitations

Although several important confounders were adjusted for, the observed independent associations may nonetheless have been prone to residual confounding. This is because many salient adverse childhood experiences, including most instances of abuse and neglect, are not routinely registered.5 The underlying reasons for residential change, such as family dissolution, were also unknown. Furthermore, socioeconomic trajectories among the cohort members beyond their 15th birthdays, which could have mediated the observed associations, were not examined. Selection of potential confounders was essentially restricted according to their availability, which is a common limitation of many studies conducted using administrative registers.40 An unknown degree of reverse causality bias41 may also have been present. Earlier unregistered problematic behaviors among older children and adolescents may have motivated some families to relocate to start afresh. However, it seems unlikely that these hidden biases could wholly explain the strong links observed between residential mobility in early/mid-adolescence and subsequent adverse outcomes. Finally, the findings may not apply universally beyond Denmark, although it seems likely that they are relevant to other western societies with similar drivers of residential mobility.

Conclusions

Childhood residential mobility is associated with multiple long-term adverse outcomes. Although frequent residential mobility could be a marker for familial psychosocial difficulties, the elevated risks were observed across the socioeconomic spectrum, and mobility may be intrinsically harmful. Health and social services, schools, and other public agencies should be vigilant of the psychological needs of relocated adolescents, including those from affluent as well as deprived families. Effective monitoring and risk management will require close cooperation among multiple public agencies, and in particular among child, adolescent, and adult mental health services. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms that explain how residential relocation during upbringing, and in early/mid-adolescence in particular, impacts negatively in combination with other determinants to produce this array of serious adverse outcomes. In particular, future analyses could consider hierarchical structuring in population-based data sets, for example, by examining clustering effects within neighborhoods and by comparing exposed versus unexposed siblings.42

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a European Research Council starting grant awarded to Roger T. Webb (ref no. 335905). The funder had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Authors’ contributions: Dr. Pedersen had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. Study concept and design: all authors. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Webb wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to subsequent revisions. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: Pedersen. Obtained funding: Webb. Administrative, technical, or material support: Pedersen, Webb.

Key findings from this manuscript were presented orally by Pearl L.H. Mok on June 18, 2015, at the 28th International Association for Suicide Prevention World Congress, Montreal, Canada. They were presented orally by Roger T. Webb on October 9, 2015 at the 15th Congress of the International Foundation for Psychiatric Epidemiology, Bergen, Norway, and they will also be presented orally by Roger T. Webb at the 16th Annual Conference of the International Association of Forensic Mental Health Services, New York City, USA, during June 2016.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found at doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.011.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Stubblefield R.L. Children’s emotional problems aggravated by family moves. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1955;25(1):120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1955.tb00122.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1955.tb00122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau. Geographical Mobility: 2014 to 2015. www.census.gov/hhes/migration/. Updated November 2015; Published February 2016. Accessed February 29, 2016.

- 3.Jelleyman T., Spencer N. Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(7):584–592. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.060103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.060103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paksarian D., Eaton W.W., Mortensen P.B., Pedersen C.B. Childhood residential mobility, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder: a population-based study in Denmark. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(2):346–354. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu074. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong M., Anda R.F., Felliti V.J. Childhood residential mobility and multiple health risks during adolescence and adulthood: the hidden role of adverse childhood experiences. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1104–1110. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scanlon E., Devine K. Residential mobility and youth well-being: research, policy, and practice issues. J Sociol Soc Welfare. 2001;28(1):119–137. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagan J., MacMillan R., Wheaton B. New kid in town: social capital and the life course effects of family migration on children. Am Sociol Rev. 1996;61(June):368–385. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2096354 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gasper J., DeLuca S., Estacion A. Coming and going: explaining the effects of residential and school mobility on adolescent delinquency. Soc Sci Res. 2010;39(3):459–476. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.08.009 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pribesh S., Downey D.B. Why are residential and school moves associated with poor school performance? Demography. 1999;36(4):521–534. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2648088 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong M., Anda R.F., Felitti V.J. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(7):771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown D., Benzeval M., Gayle V., Macintyre S., O’Reilly D., Leyland A.H. Childhood residential mobility and health in late adolescence and adulthood: findings from the West of Scotland Twenty-07 Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(10):942–950. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pettit B. Moving and children’s social connections: neighborhood context and the consequences of moving for low-income families. Sociol Forum. 2004;19(2):285–311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:SOFO.0000031983.93817.ff [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adam E.K., Chase-Landsdale P.L. Home sweet home(s): parental separations, residential moves, and adjustment problems in low-income adolescent girls. Dev Psychol. 2002;38(5):792–805. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Regional Office for Europe. Violence and Injuries. www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/violence-and-injuries/violence-and-injuries. Accessed February 29, 2016.

- 15.Pedersen C.B., Gøtzsche H., Møller J.O., Mortensen P.B. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53(4):441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen M.F., Greve V., Høyer G., Spencer M. 3rd ed. DJØF Publishing; Copenhagen: 2006. The Principal Danish Criminal Acts. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mors O., Perto G.P., Mortensen P.B. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 suppl):54–57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynge E., Sandegaard J.L., Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 suppl):30–33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordentoft M., Mortensen P.B., Pedersen P.B. Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1058–1064. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. Classification of Diseases . Danish National Board of Health; Copenhagen: 1971. Extended Danish-Latin Version of the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, 8th Revision, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO . . WHO; Geneva: 1993. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juel K., Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish registers of causes of death. Dan Med Bull. 1999;46(4):354–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danmarks Statistik . Danmarks Statistiks trykkeri; Copenhagen: 1991. IDA—en Integret Database for Arbejdsmarkedsforskning. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laird N., Olivier D. Covariance analysis of censored survival data using log-linear analysis techniques. J Am Stat Assoc. 1981;76(374):231–240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1981.10477634 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breslow N.E., Day N.E. IARC Scientific Publications No. 82; Lyon, France: 1987. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research Volume II—The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clayton D., Hills M. Oxford University Press;; Oxford: 1993. Statistical Models in Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen P., Borgen O., Gill R., Kieding N. Corrected 1st ed. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1997. Statistical Models Based on Counting Processes. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothman J., Greenland S. 2nd ed. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1998. Modern Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carstensen B. Demography and epidemiology: Practical use of the Lexus diagram in the computer age. Who needs the Cox-model anyway? Paper presented at: the Annual Meeting of the Finnish Statistical Society; May 23–24, 2005; Oulu, Finland. http://publichealth.ku.dk/sections/biostatistics/reports/2006/rr-06-2.pdf/. Revised December 2005. Accessed February 29, 2016.

- 30.Carstensen B. Example and programs for splitting follow-up time in cohort studies. Institute of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, 2007. http://staff.pubhealth.ku.dk/~bxc/Lexis/. Accessed February 29, 2016.

- 31.Macaluso M. Exact stratification of person-years. Epidemiology. 1992;3(5):441–448. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199209000-00010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199209000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedersen C.B. No evidence of time trends in the urban-rural differences in schizophrenia risk among five million people born in Demark from 1910 to 1986. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):211–219. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500663X. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S003329170500663X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haynie D.L., South S.J. Residential mobility and adolescent violence. Soc Forces. 2005;84(1):361–374. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0104 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh S.P., Winsper C., Wolke D., Bryson A. School mobility and prospective pathways to psychotic-like symptoms in early adolescence: a prospective birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(5):518–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.01.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Millegan J., McLay R., Engel C. The effect of geographic moves on mental healthcare utilization in children. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(2):276–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juon H.S., Ensminger M.E., Feehan M. Childhood adversity and later mortality in an urban African American cohort. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(12):2044–2046. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2044. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.12.2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Astone N.M., McLanahan S.S. Family structure, residential mobility, and school dropout: a research note. Demography. 1994;31(4):575–584. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2061791 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boynton-Jarrett R., Hair E., Zuckerman B. Turbulent times: effects of turbulence and violence exposure in adolescence on high school completion, health risk behavior, and mental health in young adulthood. Soc Sci Med. 2013;95:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown A.C., Orthner D.K. Relocation and personal well-being among early adolescents. J Early Adolesc. 1990;10(3):366–381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431690103008 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mortensen P.B., Allebeck P., Munk-Jørgensen P. Population-based registers in psychiatric research. Nord J Psychiatry. 1996;50(suppl 36):67–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/08039489609104316 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maselko J., Hayward R.D., Hanlon A., Buka S., Meador K. Religious service attendance and major depression: a case of reverse causality? Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(6):576–583. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bramson L.M., Rickert M.E., Class Q.A. The association between childhood relocations and subsequent risk of suicide attempt, psychiatric problems, and low academic achievement. Psychol Med. 2016;46(5):969–979. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002469. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material