Abstract

Our aim was to investigate the associations of regional fat distribution with home and office blood pressure (BP) levels and variability. Participants in the Dallas Heart Study, a multiethnic cohort, underwent five BP measurements on three occasions over 5 months (two in-home and one in-office) and quantification of visceral (VAT), abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), and liver fat by MRI, and lower body subcutaneous fat by dual x-ray absorptiometry. The relation of regional adiposity with short-term (within-visit) and long-term (over all visits) mean BP and average real variability (ARV) was assessed with multivariable linear regression.

2,595 participants mean age 44 years; 54% women, 48% black; and mean BMI 29 kg/m2 were included. Mean SBP/DBP was 127/79mmHg and ARVSBP was 9.8mmHg over 3 visits. In multivariable-adjusted models, higher amount of VAT was associated with higher short-term (both home and office) and long-term mean SBP (β[SE]: 1.9[0.5], 2.7[0.5], and 2.1[0.5], respectively, all P<0.001), and with lower long-term ARVSBP (β[SE]: -0.5[0.2], P<0.05). In contrast, lower body fat was associated with lower short-term home and long-term mean BP (β[SE]: -0.30[0.13] and -0.24[0.1], respectively, both P<0.05). Neither SAT or liver fat were associated with BP levels or variability.

In conclusion, excess visceral fat was associated with persistently higher short- and long-term mean BP level and with lower long-term BP variability whereas lower body fat was associated with lower short- and long-term mean BP. Persistently elevated BP, coupled with lower variability, may partially explain increased risk for cardiac hypertrophy and failure related to visceral adiposity.

Keywords: Blood pressure, blood pressure variability, obesity, visceral adiposity, retroperitoneal fat mass

Introduction

Obesity is a well-established risk factor for the development of hypertension.1-8 Most studies linking obesity with hypertension have used office blood pressure (BP) measured on a single occasion, a “snapshot” of BP that may not fully characterize an individual's BP status.9, 10 Alternative BP phenotypes, including out-of-office BP measurements and BP variability, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of vascular damage and stroke independent of office BP.11-14 However, previous population-based studies have shown an inconsistent relationship between obesity and BP level and variability.14-19

Many population studies examining the relationship between obesity and BP have used body mass index (BMI) as a measure of adiposity.1-4 However, obesity is a complex and heterogeneous condition, with varying amounts of ectopic fat deposition (e.g., visceral adipose tissue, VAT) despite similar BMI among individuals.20, 21 Therefore, prior studies assessing BMI alone may not accurately characterize the impact of adiposity on BP. How individual variation in regional fat distribution, a key determinant of adverse cardiovascular phenotypes,20, 22, 23 contributes to out-of-office BP levels and short- and long-term BP variability remains uncertain since previous studies have focused primarily on the relationship of adipose depots with in-office BP levels in isolation.1-4, 6-8

Therefore, using data from the Dallas Heart Study (DHS), a multiethnic population cohort, we assessed the relationship between regional fat distribution and BP phenotypes including short-term (home and office) BP levels, long-term BP levels (3 visits over 5 months), and short- and long-term BP variability. Given that visceral adiposity may mediate sympathetic nerve activity, impaired (pressure) natriuresis, insulin resistance, and adipokine and aldosterone dysregulation,3, 5, 24, 25 we hypothesized that: (1) those with excess visceral adiposity would have sustained short- and long-term BP elevation with higher BP variability, and (2) the association between visceral adiposity and BP would be modified by circulating natriuretic peptides, adipokines (i.e., adiponectin and leptin), insulin resistance, and aldosterone levels.

Methods

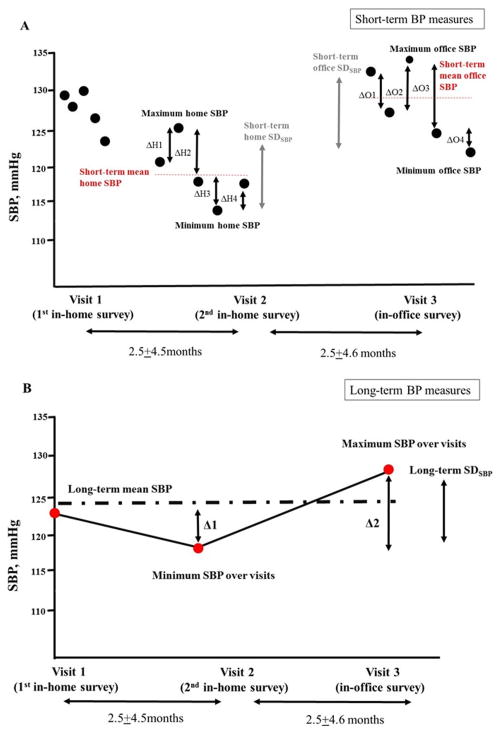

The DHS is a multiethnic (blacks, whites, and Hispanics), probability-based population study, recruiting Dallas County residents ages 18 to 65 years. Details of the DHS have been described previously.26 Briefly, between 2000 and 2002, 2,595 participants completed 3 visits during which BP was measured as described below. The 1st and 2nd examinations were an in-home survey during which a trained surveyor measured the participant's BP using an oscillometric device; the 3rd examination was an in-office survey during which BP was measured with the same oscillometric device. The mean (±SD) interval between each DHS visit was 2.5 ± 4.5 months. Figure 1 provides a timeline for the sequence and timing of the BP measurements over the three DHS visits. Participants also underwent laboratory testing, and assessment of body fat distribution by abdominal MRI and DEXA scanning. All participants provided written informed consent, and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center institutional review board approved the protocol.

Figure 1. Defining Blood Pressure Phenotypes.

The figures show an example of individual blood pressure (BP) measures across 3 visits (two in-home and one in-office). Five BP measures were taken at each of the 3 visits (black circles, panel A), and their average was defined as mean home and office BP, respectively (red dashed line in panel A and red circle, panel B). Short-term BP variability was defined as average real variability (ARV) and standard deviation (SD) over 5 reading at each of the 3 visits. Short-term home ARV is calculated as (ΔH1+ΔH2+ΔH3+ΔH4)/4 and short-term office ARV as (ΔO1+ΔO2+ΔO3+ΔO4)/4. SDs were calculated from all 5 BP values within each visit, and coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated as SD×100/mean BP. Maximum and minimum BP difference (MMD) was calculated as maximum BP minus minimum BP within each visit.

In panel B, the absolute differences of mean BP between successive visits are shown as Δ1 and Δ2. Red circles represent average of five BP measures taken at each of the 3 visits. For example, Δ1 represents the difference in SBP between the visit 1 BP and visit 2 BP. Long-term ARV is calculated as (Δ1+Δ2)/2. Mean BP and SD were calculated from all 3 BP values from visit 1 to visit 3 for each individual, and CV was calculated as SD×100/mean BP. MMD was calculated as maximum BP minus minimum BP over the entire follow-up.

The mean (±SD) interval between visits was 2.5±4.5 months.

BP measurements and BP phenotype definitions

Trained medical staff took five BP measurements with one minute intervals using the appropriate cuff size after 5 minutes of rest in seated position at both the home and office settings. An automated oscillometric device (Series #52,000, Welch Allyn, Arden, North Carolina) was used.8 Staff were trained to choose the appropriate cuff size for the participants and wrap the cuff around the arm with the center of the bladder over the brachial artery. The average of five BP measures taken during the 1st and 2nd in-home visit was defined as home BP. The average of five BP measures taken during the in-office visit was defined as office BP. Hypertension was defined as average systolic BP (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg, average diastolic BP (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg, or antihypertensive medication use.

Alternative BP phenotypes evaluated here include mean BP at each visit and over all 3 visits (BP level), within-visit (defined as short-term) home and office BP variability, and visit-to-visit (defined as long-term) BP variability over the 3 visits. For BP variability, we calculated the standard deviation (SDSBP and SDDBP), coefficient of variation, the maximum and minimum BP difference, and average real variability (ARVSBP and ARVDBP) over 5 readings taken at each visit (i.e., within-visit home or office BP variability) or across 3 visits (i.e., visit-to-visit BP variability) (Figure 1). These measures have been used to describe BP variability in previous studies.11-19, 27-30 ARV is calculated as (ΔBP1+ΔBP2+ΔBP3+ΔBP4)/4 for short-term ARV and as (ΔBP1+ΔBP2)/2 for long-term ARV where ΔBP is the absolute difference between successive BP measurements. In contrast with SD, ARV takes the order of the BP measurements into account.12, 13

Variable definitions

Data on smoking, physical activity, medication use, clinical history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), and fasting laboratory values were collected using standardized protocols.26 Physical activity was derived using self-reported frequency and type of leisure-time physical activity and a standard conversion for metabolic equivalence units (METs) and is reported as MET-min/week.31 Diabetes was defined by fasting blood glucose≥ 126 mg/dL, nonfasting blood glucose ≥200 mg/dL, or ongoing medical treatment for diabetes. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula.32 Serum aldosterone was measured using a standard assay. Measurement methods of circulating N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP: Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana), BNP (Alere Inc., San Diego, California), adiponectin (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), leptin (Linco Research Inc., St. Charles, Missouri) have been described previously.24 The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) was calculated with the following: (fasting insulin [μIU/mL] × fasting glucose [mmol/L]) divided by 22.5.33 The intraassay and interassay coefficients of these tests were all <12%.

Body fat distribution and imaging measures

BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m). Retroperitoneal, intraperitoneal, and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) abdominal fat masses were quantified by 1.5-T MRI (Intera, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands), with a single MRI slice taken at the L2–L3 level using manual contours, as previously validated against cadaveric samples.34 Areas were converted to mass (kg) using previously determined regression equations.35 VAT was defined as the combination of both retroperitoneal and intraperitoneal fat masses to express the total intra-abdominal (visceral) fat mass. DEXA (Delphi W scanner, Hologic, and Discovery software version 12.2) was used to measure lower body subcutaneous fat. Lower body subcutaneous fat was delineated by 2 oblique lines crossing the femoral necks and converging below the pubic symphysis and included gluteal-femoral fat.36 Participants also underwent 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy for hepatic triglyceride quantification, as previously described.37

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented as means and SD, and proportions where appropriate. Correlations between BP phenotypes and clinical characteristics were calculated by Pearson correlation method. Cubic smoothing spline curves were drawn to describe the shape of the associations between adiposity variables and BP phenotypes.

Multivariable-adjusted linear regression models were used to assess the association between adiposity variable and BP phenotype (both as continuous variables). We verified the model assumptions of linearity, normality of residuals, homoscedasticity and absence of collinearity.38 Variance inflation factors were calculated to examine for substantial multicollinearity among adiposity-related parameters, and values >5.0 were considered to indicate collinearity. Covariates included demographic variables: age, sex, and race and clinical characteristics: BMI, smoking, physical activity, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, use of antihypertensive medications, prevalent diabetes, and prevalent CVD. These covariates were selected a priori because they have known correlations with BP levels or BP variability.11-19 Analyses for heterogeneity of effect between the adiposity variable and BP phenotype by sex and race were performed. We also assessed the associations between adiposity-related biomarkers and BP phenotypes and whether the relationship between adiposity variables and BP phenotypes would be attenuated after adjustment for heart rate, eGFR, and adiposity-related biomarkers (i.e., circulating NT-proBNP, BNP, adiponectin, leptin, HOMA-IR, and aldosterone levels), which all represent potential mediators in the adiposity-BP relationship.20, 24, 25 We conducted additional sensitivity analyses by: (1) excluding individuals taking antihypertensive medications; and (2) assessing ARV defined by the two in-home visit BPs only. Statistical significance was defined as a P<0.05 on 2-sided tests. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Of the 2,595 participants, 54 % were women, 48 % were black, mean age was 44 years, and 20% used antihypertensive medication (Table 1). Long-term mean (±SD) SBP and DBP, SDSBP, and ARVSBP were 127±17mm Hg, 79±9 mm Hg, 8±6mm Hg, and 10±7 mm Hg, respectively. The coefficient of variation and the maximum and minimum BP differences were strongly correlated with SD (Pearson's r>0.95; Supplementary Table S1), and therefore we only report BP variability by SD and ARV. The mean BP level at each visit and short-term BP variability are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The mean (±SD) interval between visits was 2.5±4.5 months (Figure 1). Short-term home and office ARVSBP were only weakly associated with long-term ARVSBP (r=0.11-0.17; P<0.001). Higher age, male sex, black race, higher BMI, lower physical activity, and diabetes were associated with higher SBP in all settings (i.e., at home, office, and over 3 visits), as well as higher short- and long-term ARVSBP (P<0.05 for all).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of study cohort (n=2,595).

| Descriptive variable | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 43.9±10.0 |

| Men, % | 46 |

| Ethnicity, % | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 32.0 |

| African American | 48.4 |

| Hispanic | 17.4 |

| Other | 2.2 |

| Hypertension, % | 33 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 10 |

| Current smoker, % | 28 |

| Physical activity, MET-min/week | 452±772 |

| Antihypertensive medication, % | 20 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 181±39 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 50±15 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 102±43 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 124±105 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 100.4±9.0 |

| Pre-existing CVD, % | 7 |

| Long-term BP values, over 3 visits | |

| Mean SBP, mmHg | 126.8±16.7 |

| Mean DBP, mmHg | 79.0±9.0 |

| SDSBP, mmHg | 7.8±5.5 |

| SDDBP, mmHg | 4.8±2.8 |

| ARVSBP, mmHg | 9.8±7.1 |

| ARVDBP, mmHg | 6.0±3.8 |

| Adiposity variables | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.3±6.6 |

| VAT, kg | 2.2±1.0 |

| Retroperitoneal fat mass, kg | 0.8±0.5 |

| Intraperitoneal fat mass, kg | 1.3±0.7 |

| SAT, kg | 4.9±3.0 |

| VAT/SAT ratio | 0.5±0.3 |

| Hepatic triglyceride, % | 5.6±5.7 |

| Lower body subcutaneous fat, kg | 9.5±4.6 |

Data are expressed as the means ± SD or percentage. Participants underwent three examinations on different occasions during 5 months, including the 1st visit (in-home survey), the 2nd visit (in-home survey), and the 3rd visit (in-office survey), over 5 months. VAT was defined as the combination of both retroperitoneal and intraperitoneal fat mass.

SBP indicates systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SD, standard deviation; ARV, average real variability; VAT, visceral adipose tissue; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue.

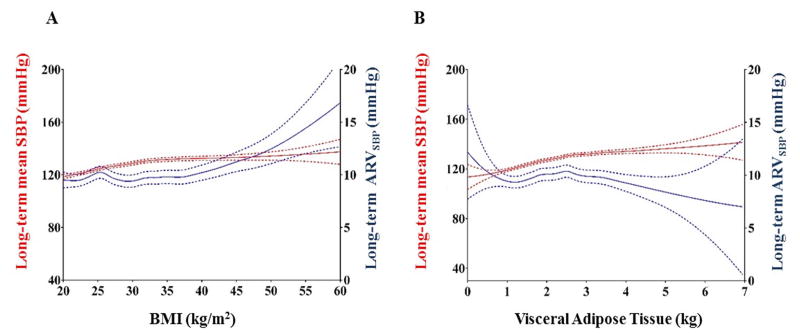

Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S1 show the associations of BMI and VAT with each BP phenotype. Higher BMI and VAT were both associated with higher mean SBP in all settings. In contrast, BMI was positively associated with long-term ARVSBP, whereas the association between VAT and long-term ARVSBP was inverse.

Figure 2. Body mass index, Visceral Adiposity, and Blood Pressure Phenotype.

The figures show associations of BMI (A) and visceral fat mass (B) with BP phenotype over all 3 visits. Red lines represent mean SBP over visits and blue lines represent long-term ARVSBP. Solid line is the cubic smoothing spline fit, and dotted line is 95% confidence interval.

Linear regression models examining the associations of adiposity variables with SBP phenotypes are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S3, and with DBP phenotypes in Supplementary Table S3. With adjustments for covariates including BMI, higher VAT was associated with higher mean SBP in all settings, whereas greater lower body subcutaneous fat was associated with lower mean SBP over 3 visits (Table 2). When VAT, SAT, and lower body subcutaneous fat were analyzed jointly, the associations with VAT and lower body subcutaneous fat remained statistically significant (Table 3, left column). When retroperitoneal fat mass and intraperitoneal fat mass were considered jointly, both were independently associated with mean BP in all settings (Table 3, right column). Within VAT, more retroperitoneal but not intraperitoneal fat mass was associated with higher short-term office ARVSBP, and with lower long-term ARVSBP (Table 2). Results were generally similar after additional adjustment for heart rate (data not shown), eGFR, circulating NT-proBNP, BNP, adiponectin, leptin, HOMA-IR, and aldosterone levels (Supplementary Table S4). We examined the associations between adiposity-related biomarkers and short- and long-term BP levels (Supplementary Table S5) and with BP variability (Supplementary Table S6) accounting for adiposity. We did not find an association of HOMA-IR with short- and long-term BP levels or variability. Positive associations were observed between NT-proBNP and short- and long-term BP levels and variability and between adiponectin and aldosterone levels with higher long-term BP variability.

Table 2. Multivariable-adjusted linear regression models to examine the association between adiposity variable and short-term and long-term mean BP and BP variability (n=2,595).

| Adiposity variable | Short-term home SBP | Short-term office SBP | Long-term SBP over 3 visits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| β (SE) | R2,% | β (SE) | R2,% | β (SE) | R2,% | |

|

|

||||||

| Mean SBP | ||||||

| VAT | 1.91 (0.52)‡ | 28 | 2.66 (0.51)§ | 28 | 2.14 (0.46)§ | 33 |

| Retroperitoneal fat mass | 1.82 (0.83)* | 28 | 2.26 (0.81)† | 27 | 1.93 (0.73)† | 32 |

| Intraperitoneal fat mass | 1.54 (0.60)† | 28 | 2.29 (0.58)§ | 27 | 1.78 (0.52)‡ | 32 |

| SAT | 0.41 (0.23) | 27 | 0.44 (0.23) | 27 | 0.38 (0.20) | 32 |

| VAT/SAT ratio | 3.30 (1.60)* | 27 | 3.39 (1.58)* | 27 | 2.72 (1.41) | 32 |

| Hepatic triglyceride | 0.02 (0.07) | 28 | 0.08 (0.07) | 27 | 0.03 (0.06) | 33 |

| Lower body subcutaneous fat | -0.30 (0.13)* | 28 | -0.22 (0.13) | 27 | -0.24 (0.12)* | 32 |

| ARVSBP | ||||||

| VAT | 0.08 (0.08) | 5 | 0.09 (0.08) | 5 | -0.46 (0.23)* | 10 |

| Retroperitoneal fat mass | 0.08 (0.12) | 5 | 0.27 (0.13)* | 5 | -0.95 (0.36)† | 10 |

| Intraperitoneal fat mass | 0.06 (0.09) | 5 | -0.02 (0.09) | 5 | -0.11 (0.26) | 9 |

| SAT | 0.01 (0.03) | 5 | 0.04 (0.04) | 5 | 0.09 (0.10) | 9 |

| VAT/SAT ratio | 0.13 (0.24) | 5 | 0.04 (0.25) | 5 | -0.29 (0.70) | 9 |

| Hepatic triglyceride | -0.01 (0.01) | 5 | -0.01 (0.01) | 5 | -0.02 (0.03) | 10 |

| Lower body subcutaneous fat | 0.01 (0.02) | 5 | 0.003 (0.02) | 5 | -0.07 (0.06) | 10 |

Each adiposity-related parameter was analyzed separately. Home SBP was defined as SBP values measured at the 2nd in-home survey (visit 2 examination), office SBP was defined as SBP values measured at in-office survey (visit 3 examination), and SBP over 3 visits were calculated from visit 1 BP (the 1st in-home survey), visit 2 BP (the 2nd in-home survey), and visit 3 BP (the 3rd in-office survey).

represents unstandardized regression coefficient, and R2 represents a measure for the model prediction. Adjusted βs (95% CIs) associated with a 1kg increment (retroperitoneal fat mass, intraperitoneal fat mass, VAT, SAT, lower body subcutaneous fat), a 1% increment (hepatic triglyceride), and a 1 unit increment (VAT/SAT ratio) are shown. As adjustment factors, all models include demographic variables (age, sex, and race)+clinical characteristics at visit 1 (BMI, smoking, physical activity, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, HDL, use of antihypertensive drugs, prevalent diabetes, and prevalent CVD).

VAT indicates visceral adipose tissue; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue. Statistical significance was defined as P <0.05.

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

P<0.0001.

Table 3. Multivariable-adjusted linear regression models to examine the associations between adiposity variable and short-term and long-term mean SBP (n=2,595).

| Adiposity variable | β (SE) | VIF | R2,% | β (SE) | VIF | R2,% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Short-term mean home SBP | |||||||

| VAT | 1.93 (0.52)‡ | 2.4 | 28 | Retroperitoneal fat | 3.97 (0.78)§ | 1.3 | 26 |

| SAT | 1.15 (0.23)§ | 3.8 | Intraperitoneal fat | 3.62 (0.52)§ | 1.3 | ||

| Lower body subcutaneous fat | -0.44 (0.14)† | 4.1 | |||||

| Short-term mean office SBP | |||||||

| VAT | 2.48 (0.52)§ | 2.4 | 27 | Retroperitoneal fat | 4.02 (0.76)§ | 1.3 | 27 |

| SAT | 0.87 (0.22)§ | 3.8 | Intraperitoneal fat | 3.87 (0.51)§ | 1.3 | ||

| Lower body subcutaneous fat | -0.36 (0.14)† | 4.1 | |||||

| Long-term mean SBP | |||||||

| VAT | 2.06 (0.46)§ | 2.4 | 33 | Retroperitoneal fat | 3.80 (0.69)§ | 1.3 | 31 |

| SAT | 0.96 (0.20)§ | 3.8 | Intraperitoneal fat | 3.56 (0.46)§ | 1.3 | ||

| Lower body subcutaneous fat | -0.36 (0.12)† | 4.1 | |||||

In left column, VAT, SAT, LBT, and total fat-free (lean) mass were analyzed jointly. In right column, retroperitoneal fat mass and intraperitoneal fat mass were analyzed jointly. β means unstandardized regression coefficient, and R2 means a measure for the model prediction. VAT was defined as retroperitoneal plus intraperitoneal fat masses. Adjusted βs (95% CIs) associated with a 1kg increment (VAT, SAT, lower body subcutaneous fat, retroperitoneal fat mass, and intraperitoneal fat mass) are shown.

As adjustment factors, we used demographic variables (age, sex, and race), clinical characteristics (smoking, physical activity, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, HDL, use of antihypertensive drugs, prevalent, and prevalent CVD), and total fat free (lean) mass were used.

VAT indicates visceral adipose tissue; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue. Statistical significance was defined as P <0.05.

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

P<0.0001.

When DBP was analyzed in place of SBP and SD was used to represent BP variability instead of ARV, results were similar (Supplementary Table S3). Results were generally similar in sex-stratified analyses (Supplementary Table S7, men and Supplementary Table S8, women) and there was no heterogeneity of effect between adiposity variables and mean SBP level or long-term ARVSBP by sex or race (all P>0.06). Results were similar when participants taking antihypertensive medications were excluded (n=2,070, Supplementary Table S9). When long-term ARVSBP was defined using only the two in-home visit SBPs, results were similar (data not shown). Neither BP level nor BP variability in all settings was associated with SAT or liver fat after multivariable adjustment (Table 2).

Discussion

In this multiethnic community-based cohort of younger and middle-aged adults, higher visceral adiposity was associated with persistently elevated mean SBP and DBP with lower long-term BP variability over 5 months, independent of BMI. Conversely, greater lower body subcutaneous fat was associated with lower long-term mean SBP, independent of both BMI and visceral adiposity. Neither short- or long-term mean SBP and DBP nor BP variability was associated with SAT or liver fat after multivariable adjustment. These findings highlight the heterogeneity of obesity sub-phenotypes and demonstrate the divergent relationships between various fat depots and BP level and variability.

Higher short- and long-term BP variability have been shown to be associated with higher risk for CVD morbidity and mortality, and all-cause mortality, independent of mean BP.11-13, 28, 29 The associations between obesity (defined by BMI) and BP variability, have been inconsistent.14-16 In our study, participants with higher BMI had higher long-term ARVSBP with a modest increase in mean SBP across BMIs, whereas an increase in mean SBP with less variable long-term ARVSBP was observed with increasing visceral adiposity. Regional fat distribution may therefore be a determinant of individual BP level and variability, independent of BMI, which would partially explain the complex associations of obesity with BP variability. Although visceral adiposity may increase sympathetic tone, its effect on baroreflex sensitivity is controversial. Much of the literature on baroreflex sensitivity associated with visceral obesity has only addressed baroreflex control of heart rate (cardiovagal baroreflex).39 However, the role of visceral obesity on baroreflex control of muscle sympathetic nerve activity (sympathetic baroreflex), which is more important for BP regulation, is more controversial.40, 41 While one study showed impaired sympathetic baroreflex,40 another showed no impairment in humans with visceral obesity.41 Thus, high muscle sympathetic nerve activity coupled with relatively intact sympathetic baroreflex could explain high BP without increasing BP variability in individuals with visceral obesity in our study.

When visceral adiposity was analyzed by its components, retroperitoneal but not intraperitoneal fat mass was associated with higher long-term BP level with lower variability. A previous observation from the DHS with a median follow-up of 7 years demonstrated that retroperitoneal fat mass (i.e. fat surrounding the kidneys) was more strongly associated with incident hypertension compared with intraperitoneal fat mass.8 The Framingham Heart Study also found that excess retroperitoneal fat around the kidneys was associated with hypertension risk independent of BMI or visceral adiposity.42

Multiple biological mechanisms may underlie the associations we observed between VAT and sustained BP elevation. First, natriuretic peptide deficiency and abnormal adipokine regulation might contribute to sustained BP elevation in those with excess VAT.5, 24 However, in our study, the association between excess VAT and higher long-term BP level with less variability was not attenuated after adjustments for circulating natriuretic peptide, adiponectin, and leptin levels. Second, neurohormonal activation, such as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and sympathetic nerve activity,3, 5, 20, 21 might contribute to sustained BP elevation. To test this possibility, analyses were performed adjusting for aldosterone or heart rate, with similar results observed. However, aldosterone measurements reflect only one aspect of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and resting heart rate is an indirect marker of sympathetic nerve activity and strongly affected by vagal activity.43 Third, impaired natriuresis may occur due to physical compression of the kidneys by fat (particularly, retroperitoneal fat),5 resulting in volume expansion and sodium retention. The potential mechanisms and clinical implications of less long-term ARVSBP at higher levels of visceral adiposity require further investigation. Positive associations were observed between NT-proBNP and short- and long-term BP levels and variability. The relationship between natriuretic peptides and BP is complex; natriuretic peptides reduce BP by decreasing blood volume and systemic vascular resistance, whereas higher serum concentration of natriuretic peptides reflect pressure-induced cardiac damage.44 Given the nature of cross-sectional analysis, causality cannot be determined and is beyond the scope of this study.

The strengths of this study include a large multiethnic epidemiologic cohort with well-phenotyped measures of adiposity. However, several limitations should be noted. First, since this is a cross-sectional study, we are unable to assign causality to our findings. Further studies are needed to determine whether reducing visceral adiposity or improving regional fat distribution can result in BP reduction in younger and middle-aged adults. Second, studies have shown that BP variability assessment will vary according to the number of measurements obtained, with a larger number of measurements allowing more accurate characterization of the BP variability.27 In our study, we were able to assess only 5 BP measurements obtained at each of the 3 study visits for determination of short and long term BP variability. We acknowledge that our study would be better powered to identify additional relationships between fat depots and ARV if further measurements were made. Further study with a greater number of visits and longer term follow-up is warranted. Third, there remains possible residual confounding in the adiposity-BP phenotype relationship, such as individual dietary patterns, environmental factors, or genetics, which we are unable to account for. Fourth, home BP was obtained by surveyors, not by self-measurement. Therefore, the definition of home BP used in our study may not be exactly congruent with other definitions used in the literature.45 However, the use of local lay, ethnically congruent field staff members likely minimized the alerting reaction during home BP measurements in the DHS, making the measurement more consistent with a “home” measurement. Furthermore, a recent study from the DHS used the same home BP definition to describe the associations of white coat and masked hypertension with target organ complications and cardiovascular events.46 Fifth, we did not adjust for multiple testing, although findings remained consistent after multivariable adjustment; validation of our findings in other epidemiological cohorts is warranted. Lastly, our findings may not be generalizable to individuals older than 65 years or other racial/ethnic groups not included in the DHS (e.g., Asians).

Perspective

In this study of younger and middle-aged adults, higher visceral adiposity was associated with higher BP level with lower variability over multiple visits. The presence of persistently elevated BP, coupled with lower BP variability, may impose a higher cardiac workload and may partly explain the increased risk for cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure seen with excess visceral adiposity.22,23 Further studies are needed to determine whether modification of adipose tissue distribution may help improve diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What's New

Excess visceral fat is associated with persistently higher long-term mean BP level with lower variability, whereas more lower body fat is associated with lower long-term BP level, independent of BMI.

What Is Relevant?

Persistently elevated BP, coupled with lower variability, may partially explain increased risk for cardiac hypertrophy and failure related to visceral adiposity.

Summary

Regional fat distribution is an important determinant of individual BP level and variability independent of BMI.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: The Dallas Heart Study was supported by a grant from the Reynolds Foundation and grant UL1TR001105 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yano is supported by the AHA Strategically Focused Research Network (SFRN) Fellow Grant. Dr. Neeland is supported by grant K23DK106520 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institute of Health and by the Dedman Family Scholarship in Clinical Care from UT Southwestern. This work is also supported by an AHA SFRN grant to UT Southwestern and to Northwestern University and a grant to Northwestern University from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Brand N, Skinner JJ, Jr, Dawber TR, McNamara PM. The relation of adiposity to blood pressure and development of hypertension. The framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1967;67:48–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-67-1-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamler R, Stamler J, Riedlinger WF, Algera G, Roberts RH. Weight and blood pressure. Findings in hypertension screening of 1 million americans. JAMA. 1978;240:1607–1610. doi: 10.1001/jama.240.15.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeMarco VG, Aroor AR, Sowers JR. The pathophysiology of hypertension in patients with obesity. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2014;10:364–376. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canoy D, Luben R, Welch A, Bingham S, Wareham N, Day N, Khaw KT. Fat distribution, body mass index and blood pressure in 22,090 men and women in the norfolk cohort of the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (epic-norfolk) study. J Hypertens. 2004;22:2067–2074. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200411000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME. Obesity-induced hypertension: Interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res. 2015;116:991–1006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sironi AM, Gastaldelli A, Mari A, Ciociaro D, Positano V, Buzzigoli E, Ghione S, Turchi S, Lombardi M, Ferrannini E. Visceral fat in hypertension: Influence on insulin resistance and beta-cell function. Hypertension. 2004;44:127–133. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000137982.10191.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi T, Boyko EJ, Leonetti DL, McNeely MJ, Newell-Morris L, Kahn SE, Fujimoto WY. Visceral adiposity is an independent predictor of incident hypertension in japanese americans. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:992–1000. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-12-200406150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandra A, Neeland IJ, Berry JD, Ayers CR, Rohatgi A, Das SR, Khera A, McGuire DK, de Lemos JA, Turer AT. The relationship of body mass and fat distribution with incident hypertension: Observations from the dallas heart study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yano Y, Kario K. Nocturnal blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: A review of recent advances. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:695–701. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2368–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra060433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, O'Brien E, Dobson JE, Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010;375:895–905. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60308-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hastie CE, Jeemon P, Coleman H, McCallum L, Patel R, Dawson J, Sloan W, Meredith P, Jones GC, Muir S, Walters M, Dominiczak AF, Morrison D, McInnes GT, Padmanabhan S. Long-term and ultra long-term blood pressure variability during follow-up and mortality in 14,522 patients with hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;62:698–705. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parati G, Ochoa JE, Lombardi C, Bilo G. Assessment and management of blood-pressure variability. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:143–155. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yano Y, Ning H, Allen N, Reis JP, Launer LJ, Liu K, Yaffe K, Greenland P, Lloyd-Jones DM. Long-term blood pressure variability throughout young adulthood and cognitive function in midlife: The coronary artery risk development in young adults (cardia) study. Hypertension. 2014;64:983–988. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muntner P, Shimbo D, Tonelli M, Reynolds K, Arnett DK, Oparil S. The relationship between visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure and all-cause mortality in the general population: Findings from nhanes iii, 1988 to 1994. Hypertension. 2011;57:160–166. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yano Y, Fujimoto S, Kramer H, Sato Y, Konta T, Iseki K, Iseki C, Moriyama T, Yamagata K, Tsuruya K, Narita I, Kondo M, Kimura K, Asahi K, Kurahashi I, Ohashi Y, Watanabe T. Long-term blood pressure variability, new-onset diabetes mellitus, and new-onset chronic kidney disease in the japanese general population. Hypertension. 2015;66:30–36. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muntner P, Levitan EB, Reynolds K, Mann DM, Tonelli M, Oparil S, Shimbo D. Within-visit variability of blood pressure and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among us adults. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14:165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Liu J, Wang W, Zhao D. The association between within-visit blood pressure variability and carotid artery atherosclerosis in general population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schutte R, Thijs L, Liu YP, Asayama K, Jin Y, Odili A, Gu YM, Kuznetsova T, Jacobs L, Staessen JA. Within-subject blood pressure level--not variability--predicts fatal and nonfatal outcomes in a general population. Hypertension. 2012;60:1138–1147. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.202143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Despres JP. Body fat distribution and risk of cardiovascular disease: An update. Circulation. 2012;126:1301–1313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.067264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karpe F, Pinnick KE. Biology of upper-body and lower-body adipose tissue--link to whole-body phenotypes. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2015;11:90–100. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu G, Jousilahti P, Antikainen R, Katzmarzyk PT, Tuomilehto J. Joint effects of physical activity, body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio on the risk of heart failure. Circulation. 2010;121:237–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neeland IJ, Gupta S, Ayers CR, Turer AT, Rame JE, Das SR, Berry JD, Khera A, McGuire DK, Vega GL, Grundy SM, de Lemos JA, Drazner MH. Relation of regional fat distribution to left ventricular structure and function. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2013;6:800–807. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neeland IJ, Winders BR, Ayers CR, Das SR, Chang AY, Berry JD, Khera A, McGuire DK, Vega GL, de Lemos JA, Turer AT. Higher natriuretic peptide levels associate with a favorable adipose tissue distribution profile. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:752–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang ZV, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, cardiovascular function, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;51:8–14. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, Peshock RM, Vaeth PC, Leonard D, Basit M, Cooper RS, Iannacchione VG, Visscher WA, Staab JM, Hobbs HH. The dallas heart study: A population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1473–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitan EB, Kaciroti N, Oparil S, Julius S, Muntner P. Blood pressure measurement device, number and timing of visits, and intra-individual visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14:744–750. doi: 10.1111/jch.12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diaz KM, Tanner RM, Falzon L, Levitan EB, Reynolds K, Shimbo D, Muntner P. Visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2014;64:965–982. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Thijs L, Richart T, Li Y, Hansen TW, Boggia J, Kuznetsova T, Kikuya M, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Staessen JA. Blood pressure variability in relation to outcome in the international database of ambulatory blood pressure in relation to cardiovascular outcome. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:757–766. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin JH, Shin J, Kim BK, Lim YH, Park HC, Choi SI, Kim SG, Kim JH. Within-visit blood pressure variability: Relevant factors in the general population. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:328–334. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O'Brien WL, Bassett DR, Jr, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, Jacobs DR, Jr, Leon AS. Compendium of physical activities: An update of activity codes and met intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, Ckd EPI A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abate N, Burns D, Peshock RM, Garg A, Grundy SM. Estimation of adipose tissue mass by magnetic resonance imaging: Validation against dissection in human cadavers. J Lipid Res. 1994;35:1490–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abate N, Garg A, Coleman R, Grundy SM, Peshock RM. Prediction of total subcutaneous abdominal, intraperitoneal, and retroperitoneal adipose tissue masses in men by a single axial magnetic resonance imaging slice. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:403–408. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vega GL, Adams-Huet B, Peshock R, Willett D, Shah B, Grundy SM. Influence of body fat content and distribution on variation in metabolic risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4459–4466. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szczepaniak LS, Babcock EE, Schick F, Dobbins RL, Garg A, Burns DK, McGarry JD, Stein DT. Measurement of intracellular triglyceride stores by h spectroscopy: Validation in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E977–989. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.5.E977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenland S. Introduction to regression. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd. Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 418–458. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beske SD, Alvarez GE, Ballard TP, Davy KP. Reduced cardiovagal baroreflex gain in visceral obesity: Implications for the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H630–635. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00642.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grassi G, Dell'Oro R, Facchini A, Quarti Trevano F, Bolla GB, Mancia G. Effect of central and peripheral body fat distribution on sympathetic and baroreflex function in obese normotensives. J Hypertens. 2004;22:2363–2369. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200412000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alvarez GE, Beske SD, Ballard TP, Davy KP. Sympathetic neural activation in visceral obesity. Circulation. 2002;106:2533–2536. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000041244.79165.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foster MC, Hwang SJ, Porter SA, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. Fatty kidney, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease: The framingham heart study. Hypertension. 2011;58:784–790. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grassi G, Vailati S, Bertinieri G, Seravalle G, Stella ML, Dell'Oro R, Mancia G. Heart rate as marker of sympathetic activity. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1635–1639. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816110-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freitag MH, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Wilson PW, Vasan RS, Framingham Heart S. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels and blood pressure tracking in the framingham heart study. Hypertension. 2003;41:978–983. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000061116.20490.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stergiou GS, Asayama K, Thijs L, Kollias A, Niiranen TJ, Hozawa A, Boggia J, Johansson JK, Ohkubo T, Tsuji I, Jula AM, Imai Y, Staessen JA. International Database on HbpirtCOI. Prognosis of white-coat and masked hypertension: International database of home blood pressure in relation to cardiovascular outcome. Hypertension. 2014;63:675–682. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tientcheu D, Ayers C, Das SR, McGuire DK, de Lemos JA, Khera A, Kaplan N, Victor R, Vongpatanasin W. Target organ complications and cardiovascular events associated with masked hypertension and white-coat hypertension: Analysis from the dallas heart study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2159–2169. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.