Highlights

-

•

Pregabalin and azithromycin therapy is associated with a potentially fatal occurrence of rhabdomyolysis.

-

•

We report an extremely rare case of rhabdomyolysis with purpura caused by a drug interaction between pregabalin and azithromycin.

-

•

The details of the interaction between azithromycin and the pregabalin are still unknown.

Keywords: Pregabalin, Azithromycin, Rhabdomyolysis, Purpura, Adverse reaction, Drug interaction

Abstract

Introduction

Rhabdomyolysis associated with the use of pregabalin or azithromycin has been demonstrated to be a rare but potentially life-threatening adverse event. Here, we report an extremely rare case of rhabdomyolysis with purpura in a patient who had used pregabalin and azithromycin.

Presentation of case

We present the case of a 75-year-old woman with a history of fibromyalgia who was admitted with mild limb weakness and lower abdominal purpura. She was prescribed pregabalin (75 mg, twice daily) for almost 3 months to treat chronic back pain. Her medical history revealed that 3 days before admission, she began experiencing acute bronchitis and was treated with a single dose of azithromycin (500 mg). She had developed rapid onset severe myalgia, mild whole body edema, muscle weakness leading to gait instability, abdominal purpura and tender purpura on the lower extremities. Laboratory values included a white blood cell count of 25,400/mL and a creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) concentration of 1250 IU/L. Based on these findings and the patient’s clinical history, a diagnosis of pregabalin- and azithromycin-induced rhabdomyolysis was made.

Discussion

The long-term use of pregabalin and the initiation azithromycin therapy followed by a rapid onset of rhabdomyolysis is indicative of a drug interaction between pregabalin and azithromycin.

Conclusion

We report an extremely rare case of rhabdomyolysis with purpura caused by a drug interaction between pregabalin and azithromycin. However, the mechanisms of the interactions between azithromycin on the pregabalin are still unknown.

1. Introduction

The typical clinical presentation of rhabdomyolysis includes muscle weakness, myalgia and dark-colored urine due to myoglobinuria. The diagnosis is usually based on elevated serum skeletal muscle enzyme levels [1]. Pregabalin is a ligand that acts as a γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) analogue and binds to the alpha-2-δ subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channels in the central nervous system. The FDA has approved its use for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), fibromyalgia, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, and several neuropathic pain [2]. Azithromycin interferes weakly with cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and has been reported to cause rhabdomyolysis through interactions with several statins [3]. Pregabalin is not recognized as a cause of rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis associated with the use of pregabalin has been demonstrated to be rare but potentially life-threatening [4]. Cutaneous eruptions and purpura in cases of rhabdomyolysis are infrequent. Here, we report an extremely rare case of rhabdomyolysis with purpura in a patient who had used pregabalin and azithromycin. To our knowledge, this case is the first report of pregabalin- and azithromycin-induced rhabdomyolysis with purpura. We report this rare case and review the related literature.

2. Presentation of case

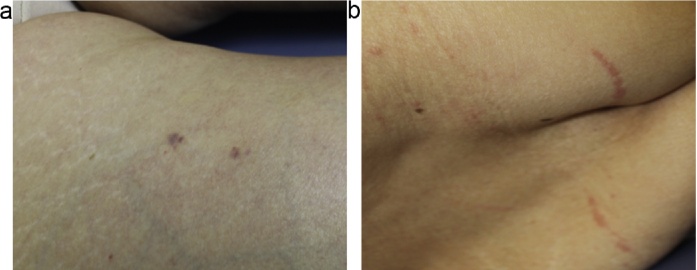

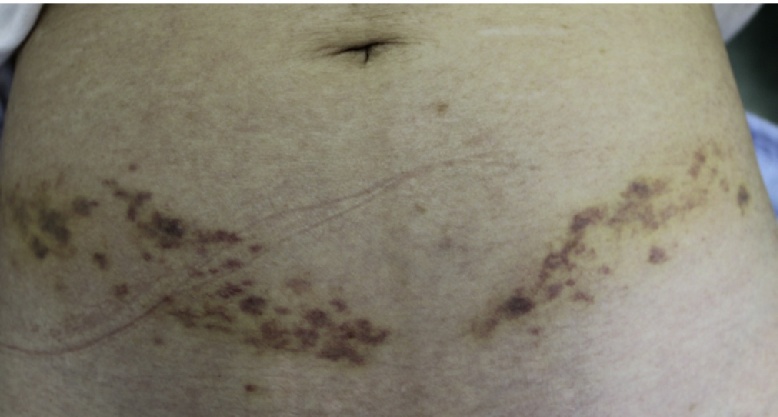

The patient was a 75-year-old woman with chronic back pain who also had hyperlipidemia. Her past medical history included the use of fenofibrate (100 mg, once daily) to treat hypertriglyceridemia (serum triglyceride level: 366 mg/dl) for almost 3 months. Fenofibrate was discontinued once her triglyceride level returned to normal. Two months later, she was started on pregabalin (75 mg, twice daily) for chronic lower back pain. This occurred 3 months before presentation with rhabdomyolysis. Her past medical history included the following pertinent factors: no recent viral illness, history of trauma, or epilepsy, and the absence of any other medications that could potentially be associated with rhabdomyolysis. The patient’s medical history revealed that 3 days before admission, she began experiencing acute bronchitis and was treated with a single dose of azithromycin (500 mg). She had developed rapid-onset severe myalgia and muscle weakness over these 3 days, which led to gait instability. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated bilateral purpura on the lower abdomen in a straight line with a small lesion in the right anterior femoral area (Fig. 1, Fig. 2a). Azithromycin use was then discontinued.

Fig. 1.

Bilateral purpura on the lower abdomen in a straight line with slight edema.

Fig. 2.

a, b: Purpura on the lower extremities and ecchymotic lesions on the back.

Upon admission, the patient had slight, generalized muscle pain and weakness and the following laboratory values: white blood cell count, 24,000/μl; platelet count, 294,000/μl; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 38 U/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 31 U/L; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 329 U/L; triglycerides, 138 mg/dl; total cholesterol, 187 mg/dl; creatine, 0.7 mg/dl; creatinine phosphokinase (CPK), 1250 U/L (reference range: 40–170 U/L); blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 26 mg/dl (reference range: 8–15 mg/dl); prothrombin time, 11.3 s; active partial prothrombin time, 31.4 s; fibrinogen degradation product, 41.6 μg/mL; and D-dimer, 22.9 mic/mL (reference range: 0–1.0 mic/mL). The elevated CPK was not cardiac in origin because both electrocardiography and myocardial enzyme markers were within normal limits. Urinalysis was consistent with myoglobinuria. One day after admission, she had tender erythematous lesions on her back (Fig. 2b). A computed tomography (CT) scan of her head was negative for a hemorrhage and an infarction. Based on these findings and the clinical history, a diagnosis of pregabalin- and azithromycin-induced rhabdomyolysis with lower abdominal purpura was made [5]. Pregabalin was then discontinued. Five days later, the patient had significantly improved and CPK levels began to decline. All conditions, including purpura, returned to normal within three weeks.

3. Discussion

Rhabdomyolysis can be caused by various drugs and toxins, as well as by mechanical, viral and metabolic factors. Several factors have been identified that increase the risk for both myopathy and rhabdomyolysis, including advanced age, chronic renal failure (CRF), metabolic disorders, major surgery, and alcohol abuse [6], [7]. The clinical manifestations of rhabdomyolysis are nonspecific. This condition presents as myalgia, weakness, fatigue, and dark-colored urine, which usually develop within a few days of starting the treatment. The most noteworthy adverse reactions associated with statins are elevations in symptoms associated with myopathy and rhabdomyolysis, which is characterized by massive muscle necrosis, myoglobinuria, and acute renal failure [8]. Pravastatin monotherapy is associated with the potentially fatal occurrence of rhabdomyolysis, which induces DIC and purpura fulminans [9]. In a recently published review, it was suggested that myopathy occurred in 20% of patients receiving statin therapy [10]. The risk of rhabdomyolysis with statin monotherapy is dose-dependent. The adverse events associated with pravastatin, simvastatin, atorvastatin, and rosuvastatin submitted to the FDA include myalgia, rhabdomyolysis, an increase in CPK levels and other muscular events.

Pregabalin is not recognized as a cause of rhabdomyolysis. A previous report showed a 0.8% incidence of CPK elevation in a pregabalin group compared with a 0.4% incidence in a control group [11]. There are three case reports and three premarketing reports of rhabdomyolysis associated with pregabalin [1], [2], [12], [13]. The mechanism by which rhabdomyolysis occurs with pregabalin is poorly defined. The occurrence is known to increase with dosage [14]. Sakamoto [15] found that fluvastatin and pravastatin induced the formation of numerous vacuoles in the myofibers of rats after 72 h of treatment and the inactivation of Rab GPTase, which is involved in intracellular membrane transport and is a crucial factor in statin-induced-morphological abnormalities in skeletal muscle fibers. This risk increase in patients taking concomitant drugs that inhibit cytochrome P450 (mainly CYP2C9 or CYP3A4)-related statin metabolism, such as azole antifungals, cyclosporine, fibrates, macrolides, and non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers [16].

Pregabalin does not inhibit hepatic metabolism or cytochrome P450 metabolism. Pregabalin is rapidly absorbed after oral administration, with 90% oral bioavailability. The plasma concentration is obtained in 24–48 h. It does not bind plasma proteins, has an elimination half-life of approximately 6 h, and 98% is excreted unchanged in urine [17]. Common adverse reactions include central nervous system depression and dizziness. Various infectious agents may cause rhabdomyolysis [18], and consequently, the infection for which azithromycin was given could have led to rhabdomyolysis without any drug interaction. Rhabdomyolysis associated with azithromycin monotherapy is extremely rare and may result in myoglobinuria. Clarithromycin and erythromycin, but not azithromycin, inhibit CYP3A4.

Recently, several case reports have suggested that the interaction between azithromycin and statins may result in rhabdomyolysis [3]. Azithromycin has been reported to increase the bioavailability of ivermectin, a substrate or the transporter of P-glycoprotein and CYP3A4 [3], [19]. This evidence is suggestive of a drug interaction between statins and azithromycin. The long-term use of pregabalin associated with a rapid onset, within few days, of rhabdomyolysis after azithromycin use is indicative of a drug interaction in our case. It is not known whether the combination of pregabalin and azithromycin increases the risk of myositis or rhabdomyolysis. No known interactions have been published to date between pregabalin and azithromycin. Cutaneous eruption or purpura is extremely rare in patients with rhabdomyolysis. Some authors have reported that well demarcated erythema, violaceous plaques and petechiae, and ulcers occur several hours or days after the application of pressure to a specific area. Tissue hypoxia and pressure are considered to be causative factors for skin eruption or purpura [5], [20]. Bilateral linear purpura might be caused by the pressure from underwear in our case.

This case report suggests an interaction between pregabalin and azithromycin resulting in rhabdomyolysis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a combined therapy with pregabalin and azithromycin resulting in rhabdomyolysis with purpura.

4. Conclusions

In summary, pregabalin was associated with a potentially fatal event of rhabdomyolysis in a patient using azithromycin. However, the details of the interaction between azithromycin and the pregabalin are still unknown. We report an extremely rare case of pregabalin- and azithromycin-induced rhabdomyolysis with purpura.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have identified a conflict interest.

Funding

No funds supported this study.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by our hospital’s institutional review board. The patient provided informed consent for this report.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images. Copies of the written consent are available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

This study was approved by our hospital’s institutional review board and included a waiver of informed consent.

Author contributions

Dr. Kato had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Kato, Onodera.

Acquisition of data: Kato. Ki, Taniguchi, Tsutsui.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Kato, Taniguchi

Drafting of the manuscript: Kato, Onodera.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kato, Matsuda.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Higuchi, Kato Y.

Study supervision: Onodera, Tsutsui.

Guarantor

Kazuya Kato, M.D., Ph.D.

Key learning points

-

•

Pregabalin and azithromycin therapy is associated with a potentially fatal occurrence of rhabdomyolysis with purpura.

-

•

The mechanisms of the interactions between azithromycin on the pregabalin are still unknown.

References

- 1.Sauret J., Marinides G., Wnag G. Rhabdomyolysis. Am. Fam. Phys. 2002;65:907–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2012. Pfizer Australlia Product Information Lyrica (pregabalin). Canberra: Therapic Goods Admisnistration.http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=561 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strandell J., Bate A., Hagg S. Rhabdomyolysis a result of azithromycin and statins: an unrecognized interaction. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009;68:427–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunathilake R., Boyce L.E., Knight A.T. Pregabalin-associated rhabdomyolysis. MJA. 2013;199:624–625. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasternak R.C., Simth S.C., Bairey-Merz C.N. ACC/AHA/NHLBI Clinical advisory on the use and safety of statins. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002;40:567–572. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ludmer L.M., Chandeysseon P., Barth W.F. Diphosphonate bone scan in an unusal case of rhabdomyolysis: a report and literature review. J. Rheumatol. 1993;20:382–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhabdomyolysis Khan F.Y. A review of he literature. Neth. J. Med. 2009;67:272–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.William D., Freely J. Pharmacokinetic-pharmaco dynamic drug interactions with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Clin. Pharmacokeinet. 2002;41:343–370. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato K., Iwasaki Y., Matsuda M. Pravastatin-induced rhabdomyolysis and purpura fulminans in a patient with chronic renal failure. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2015;8:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez G., Spatz E.S., Jablecki C. Statin myopathy: a common dilemma not reflected in clinical troials. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2011;78:393–403. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78a.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S.K., Kim Y.C., Lee B.J. Sclerodrma-like changes in cutaneous eruption of rhabdomyolysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005;53:177–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufman M.B., Choy M. Pregabalin and simvastatin: first report of a case of rhabdomyolysis. P&T. 2012;37:579–595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn M., Sriharan K., McFarland M.S. Gemfibrozil-induced myositis in a patient with normal renal function. Ann. Pharmacother. 2010;44:211–213. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham D., Staffa J.A., Shatin D. Incidence of hospitalized rhabdomyolysis in patients treated with lipid-lowering drugs. JAMA. 2004;292:2585–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.21.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakamoto K., Honda T., Yokoya S. Rab-small GPTases are involved in fluavastatin and pravastatin-induced vacuolation in rat skeletal myofibers. FASEB. 2007;21:4087–4094. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8713com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellosta S., Paoletti R., Corsini A. Safety of statins: focus on clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Circulation. 2004;109(23 (Suppl. 1)):11150–11157. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131519.15067.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bockbrader H.N., Radulovic E.L., Posvar L.L. Clinical pharmacokinetics of pregabalin in healthy volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010;50:941–950. doi: 10.1177/0091270009352087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen K.E., Hilderbrand J.P., Fergusson E.E. Outcomes in 45 patients with statin-associated myopathy. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005;165:2671–2676. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neuvonen P., Backman J.T., Niemi M. Pharmacokinetic comparison of the potential over-the-counter statins simvastatin, lovastatin, fluvastatin and pravastatin. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:463–474. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyamoto T., Ikehara A., Kobayahi T. Cutaneous eruptions in coma patients with nontraumatic rhabdomyolysis. Dermatology. 2001;203:233–237. doi: 10.1159/000051755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]