Abstract

Objectives

We evaluated the effects of three doses of a behavioral intervention for obesity (High dose = 24 sessions, Moderate = 16 sessions, Low = 8 sessions) compared with a nutrition education control group (Control) on binge eating. We also examined whether participants with clinically significant improvements in binge eating had better treatment adherence and weight-loss outcomes than those who did not experience clinically significant improvements in binge eating. Finally, we examined the relation of pretreatment binge eating severity to changes at six months.

Methods

Participants included 572 adults (female = 78.7%; baseline mean ±SD: age = 52.7 ±11.2 years, BMI = 36.4 ±3.9 kg/m2) who provided binge eating data at baseline. We evaluated binge eating severity (assessed via the Binge Eating Scale) and weight status at baseline and six months, as well as treatment adherence over six months.

Results

At six months, participants in the Moderate and High treatment conditions reported greater reductions in binge eating severity than participants in the Low and Control conditions, ps < .02. Participants who demonstrated improvements in binge eating severity reported greater dietary self-monitoring adherence and attained larger weight losses than those who did not experience clinically significant reductions, ps < .001. Pretreatment binge eating severity predicted less improvement in binge eating severity over six months and fewer days with dietary self-monitoring records completed, ps ≤ .002.

Conclusion

A moderate or high dose of behavioral weight-loss treatment may be required to produce clinically significant reductions in binge eating severity in adults with obesity.

Keywords: Obesity, Binge Eating, Weight Management, Treatment Dose

1. Introduction

Binge eating – generally defined as consuming what is perceived as a large amount of food within a discrete period of time accompanied by a loss of control and negative feelings such as disgust, shame, and guilt – is common among adults seeking obesity treatment (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Klatzkin, Gaffney, Cyrus, Bigus, & Brownley, 2015). While eating large amounts of food in one sitting is not unusual in the United States, binge eating is a distinct behavioral pattern associated with distress and loss of control, and Binge Eating Disorder (BED) is a clinical diagnosis with specific requirements regarding the period of time during which the food is eaten and the frequency of the binge eating behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Previous studies have found that as many as 55% of adults seeking weight-management treatment for obesity report episodes of binge eating (de Zwaan, 2001; Gormally, Black, Daston, & Rardin, 1982; Linde et al., 2004). Estimates of lifetime prevalence of BED in the United States range from 2.0%–3.5% (Hudson et al., 2007; Kessler et al., 2013), yet 20%–30% of treatment-seeking adults with obesity meet full criteria for BED (Hudson et al., 2007; Spitzer et al., 1992; Striegel-Moore & Franko, 2008) and adults who meet diagnostic criteria for BED are more likely to have a Body Mass Index (BMI) in the obese range than those without a history of eating disorders (Pike, Dohm, Striegel-Moore, Wilfley, & Fairburn, 2001). However, there is currently limited research on the effects of behavioral weight-loss treatment on binge eating and the dose of treatment needed to produce significant reductions in binge eating severity. In the current study, we evaluated the effect of three doses of a behavioral weight-loss intervention on binge eating symptom severity in obese adults.

Evidence is mixed regarding whether behavioral weight-loss interventions for obesity can reduce participants’ binge eating symptom severity. Some previous studies suggest that behavioral weight-management interventions are less effective at reducing symptoms of binge eating than cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and other specialized treatments for BED but more effective at inducing weight loss (Berkman et al., 2015; Iacovino, Gredysa, Altman, & Wilfley, 2012; Vocks et al., 2010; Wilson, Wilfley, Agras, & Bryson, 2010; Wilson, 2011). However, Grilo, Masheb, Wilson, Gueorguieva, and White (2011) found that CBT induced significantly greater reductions in BED symptoms up to 12-months than behavioral weight-loss treatment, yet both treatment options were effective; 51% of participants receiving CBT, 36% of participants receiving behavioral weight-loss treatment, and 40% of participants receiving both CBT and behavioral weight-loss treatment experienced remission from BED. Additionally, Munsch et al. (2007) found that the superior posttreatment effect of CBT over a behavioral weight-loss intervention in treating BED diminished at the 12-month follow-up. Given these conflicting findings, further research is warranted regarding the effectiveness of behavioral weigh-loss interventions for adults with symptoms of binge eating.

To our knowledge, there is no research on the effect of different doses of a behavioral weight loss treatment on binge eating severity. While several studies have found that 16 sessions of a weight-loss program for obese adults is associated with significant reductions in binge eating severity over six months (e.g., Devlin, Goldfein, Petkova, Liu, & Walsh, 2007; Grilo et al., 2011), none has specifically compared treatment doses to identify a threshold dose that can elicit clinically meaningful improvements.

Currently, there is also no empirical consensus on whether obese individuals who binge eat experience greater difficulties with treatment adherence or achieve poorer weight-loss outcomes in behavioral weight-loss treatments than their non-binge eating counterparts. Several studies have found that individuals who binge eat are more likely to drop out of a standard weight management intervention for obesity (e.g., Goode et al., 2016; Moroshko, Brennan, & O'Brien, 2011; Teixeira, Going, Sardinha, & Lohman, 2005) and achieve poorer weight-loss outcomes (e.g., Gorin et al., 2008; Masheb et al., 2015). While other studies have failed to find a relationship between pretreatment binge eating and either dietary self-monitoring adherence or weight-loss outcomes (e.g., de Zwaan, 2001; Raymond, de Zwaan, Mitchell, Ackard, & Thuras, 2002; Stunkard & Allison, 2003), there are data to suggest that improvements in uncontrolled eating are associated with better weight loss outcomes and treatment adherence in adults with obesity (e.g., Nurkkala et al., 2015; Keränen et al., 2009; Wilson, Wilfley, Agras, & Bryson, 2010).

1.1 Current Study Aims

The primary aim of the present study was to evaluate the impact of three doses of behavioral treatment for obesity compared with a nutrition education control group on participants’ self-reported symptoms of binge eating. A secondary aim of the current study was to determine whether participants who experienced clinically significant improvements in binge eating symptoms had better treatment adherence and larger weight losses than those who did not report improvements. As a third aim, this study examined the relation of pretreatment binge eating severity to changes in binge eating severity, treatment adherence, and weight outcomes at six months.

1.2 Hypotheses

Given that longer treatment should afford participants greater opportunities to acquire the skills to manage binge eating, we hypothesized that participants in the High dose treatment condition would report greater reductions in binge eating behaviors over six months than participants in the Low dose and Control conditions. We further hypothesized that participants who reported clinically meaningful improvements in binge eating severity would have greater treatment adherence (i.e., completion of dietary self-monitoring records and treatment session attendance) and weight loss than those who did not report clinically meaningful improvements. Additionally, we hypothesized that greater pretreatment binge eating severity would predict less improvement in binge eating severity, lower treatment adherence, and smaller weight losses over six months.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants in the current study included 572 of the 612 men and women (ages 21–75) with obesity who volunteered to take part in a study examining the effects of three doses of a group lifestyle intervention on weight outcomes; the 40 participants who did not complete the Binge Eating Scale at baseline were excluded from the analyses. Participants were required to have a baseline BMI (kg/m2) ≥ 30 and ≤ 45 and live in one of ten rural counties in northern Florida. Eligible participants were free of uncontrolled medical conditions (e.g., hypertension and diabetes). The use of medications known to affect body weight, a net weight change ≥ 4.5 kg in the preceding six months, musculoskeletal conditions that impede walking for 30 minutes, psychosocial conditions such as substance abuse, and clinically significant depression were similarly exclusionary (see Perri et al., 2014 for a detailed description of eligibility requirements, recruitment and screening procedures, and treatment content). Participants in the current study were not required to endorse symptoms of binge eating or meet criteria for BED.

2.2 Content and Doses of Treatment

Participants attended weekly in-person meetings in groups of 6–15 women and men for up to six months. Eligible participants were randomized into one of the four study conditions: High dose behavioral treatment (HIGH = 24 weekly sessions), moderate dose behavioral treatment (MOD = 16 weekly sessions), low dose behavioral treatment (LOW = 8 weekly sessions), and a nutrition education control group (CONTROL = 8 weekly sessions). The intervention in the HIGH, MOD, and LOW dose lifestyle treatments were modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program (Diabetes Prevention Program Group, 2002) and focused on implementing a low-calorie diet (e.g., 1200 kcal/day), increasing physical activity (e.g., additional 30 minutes of walking), and utilizing behavior change strategies (e.g., goal setting, written self-monitoring of food and drink intake, stimulus control, cognitive restructuring) aimed at creating a negative energy balance. Intervention content and accompanying written materials provided to participants was the same for LOW, MOD, and HIGH, but the time available for discussion varied according to the dose of treatment. The nutrition education condition (CONTROL) served as a control for staff attention and for delivery of information relevant to weight management.

2.3 Measures

Measures in this study were administered at baseline and six months. Given the differing doses of treatment, the assessment at six months is not synonymous with posttreatment (e.g., HIGH dose treatment lasted six months, MOD lasted four months, and LOW and CONTROL lasted two months).

2.3.1 Binge Eating Severity

In the current study, specific diagnostic criteria for BED were not formally assessed. Rather, the Binge Eating Scale (BES; Gormally et al., 1982) was used to assess binge eating symptomatology and behaviors. The BES is a self-report measure created using a sample of treatment-seeking obese adults. Each question on the BES provides three or four options of increasing severity regarding participants’ eating behaviors and cognitions. Scores ranging from 0–46 reflect a sum of 16 questions, with higher scores indicating more severe binge eating. The BES also classifies participants based upon their scores into clinically meaningful categories: Mild/No Binge Eating (0–17), Moderate Binge Eating (18–26), and Severe Binge Eating (27–46). The major differences between those with Moderate and Severe Binge Eating were identified as the degree and frequency of self-control over eating urges and the severity of the emotional consequences of overeating. In previous studies, the BES yielded internally consistent scores, Cronbach's α = 0.85, internally valid scores as measured by associations with concurrent food records, r = 0.20–0.40, p < .05, adequate sensitivity of .85 and specificity of 0.20, appropriate test-retest reliability, r = .87, p < .001, and satisfactory discriminant validity for binge eating severity levels in both men and women (Celio, Wilfley, Crow, Mitchell, & Walsh, 2004; Gormally et al., 1982; Timmerman, 1999). In the current study, the BES similarly yielded internally consistent scores, Cronbach's α = .88.

2.3.2 Weight Change

A calibrated, certified digital scale (Tanita, Model BWB-800S, Arlington Heights, IL) was used to measure body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg at baseline and Month 6. A study nurse, who was blind to treatment condition, weighed participants in light indoor clothing without shoes and with empty pockets. Percentage of initial body weight lost was calculated for all participants at Month 6.

2.3.3 BMI

Height was measured at baseline using a calibrated Seca stadiometer (Shorr Productions, Olney, MD). Participants were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm without shoes by the study nurse. Height and body weight were used to calculate BMI (kg/m2).

2.3.4 Treatment Adherence

Dietary Self-Monitoring

Percentage of days with dietary self-monitoring records completed (i.e., daily food logs submitted with caloric value of foods and drinks totaled) and percentage days with caloric intake goals met (i.e., participant reported calories equal to or less than their established daily calorie goals) were calculated for participants across behavioral treatment conditions (LOW, MOD, and HIGH).

Session Attendance

Percentage of total treatment sessions attended, including make-up sessions, was calculated for participants based upon the total number of sessions offered in their treatment condition.

3. Statistical Analyses

Prior to analyses with IBM®'s statistical software package SPSS® 21.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., IL), Multiple Imputation using SPSS® missing values procedure was conducted in order to ensure that the full sample was utilized and to acquire improved parameter estimates. We used 10 imputations to address missing binge eating severity data (19.6% at Month 6) and 50 imputations to address missing weight data (8.7% at Month 6); a more conservative imputation approach was employed for missing weight data because weight loss was a primary outcome in the parent trial. Treatment condition, baseline age, baseline weight, baseline BMI, baseline binge eating severity, baseline self-efficacy for weight management (as measured by the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire), percentage of treatment sessions attended, and percentage of daily self-monitoring logs completed were used as predictors to impute missing data at Month 6. A range of values provided by the multiple imputations is provided where a pooling approach for imputation results has not yet been defined.

For the primary aim, a repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc tests with simple effects decomposition was used to evaluate between-group differences in change in binge eating severity. Little's Missing Completely at Random test, which tests the assumption that data is missing completely at random, was significant for binge eating severity data at Month 6, χ2(2) = 12.709, p = .002.

For the secondary aim, we identified two groups of individuals based on pre- to posttreatment changes on the BES. Only participants with BES data at Month 6 who reported eating patterns indicative of Moderate (73.5%) or Severe Binge Eating (26.5%) at baseline were used for these analyses (n = 151, female = 88.7%; M ± SD: age = 52.5 ± 10.3 years, BMI = 36.9 ± 4.0 kg/m2). The Clinically Significant Improvement Group (n = 113) was comprised of those who improved from the Severe or Moderate Binge Eating categories to the Mild/No Binge Eating category over six months, and the No Significant Improvement Group (n = 38) included those who remained in the Severe or Moderate Binge Eating categories. Independent samples t-tests were used to evaluate the effects of group on treatment adherence, percent weight change, and BMI change.

For the third aim, hierarchical regressions controlling for treatment condition in the first block were used to assess the relation between pretreatment binge eating severity and change in binge eating, treatment adherence, and weight-loss outcomes at six months. Little's test was non-significant, χ2(2) = 5.13, p = .077; however, independent samples t-tests indicated that participants with missing weight data at Month 6 were significantly younger than those with weight data available, p < .001. Independent samples t-tests were also utilized to examine the effects of race (Caucasian compared to all other races) and ethnicity (Hispanic compared to non-Hispanic) on change in binge eating severity over six months.

All measures of binge eating, treatment adherence, and weight change were normally distributed and linearly related with the exception of percent treatment sessions attended, which was negatively skewed and positively kurtotic given the high rates of attendance. As such, we utilized a Blom transformation to normalize percent of sessions attended in the analyses.

4. Results

4.1 Demographics

A total of 572 participants randomized into three doses of a weight-loss intervention for obesity were included in the present study (Table 1). Preliminary analyses using chi-squared tests and ANOVA F-tests indicated that there were no significant pretreatment differences between conditions.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Treatment Condition

| Characteristics | CONTROL | LOW | MOD | HIGH | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 158 | n = 136 | n = 127 | n = 151 | n = 572 | |

| Sex, N (%) | |||||

| Men | 29 (18.4) | 34 (25.0) | 21 (16.5) | 38 (25.2) | 122 (21.3) |

| Women | 129 (81.6) | 102 (75.0) | 106 (83.5) | 113 (74.8) | 450 (78.7) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 52.3 (10.4) | 52.1 (12.0) | 52.6 (10.4) | 53.6 (12.0) | 52.7 (11.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |||||

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 27 (17.1) | 21 (15.4) | 16 (12.6) | 22 (14.6) | 86 (15.0) |

| Hispanic | 8 (5.1) | 3 (2.2) | 4 (3.2) | 5 (3.3) | 20 (3.5) |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 117 (74.1) | 111 (81.6) | 105 (82.7) | 116 (76.8) | 449 (78.5) |

| Other/multiple | 6 (3.8) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | 8 (5.3) | 17 (3.0) |

| Education, highest level completed, N (%) | |||||

| < High school | 26 (16.5) | 24 (17.6) | 22 (17.3) | 27 (17.9) | 99 (17.3) |

| High school | 82 (51.9) | 58 (42.7) | 75 (59.1) | 77 (51.0) | 292 (51.1) |

| Associate's degree | 16 (10.1) | 20 (14.7) | 17 (13.4) | 22 (14.6) | 75 (13.1) |

| Bachelor's degree | 14 (8.9) | 22 (16.2) | 8 (6.3) | 19 (12.6) | 63 (11.0) |

| Advanced degree | 20 (12.7) | 12 (8.8) | 5 (3.9) | 6 (4.0) | 43 (7.5) |

| Annual household income, N (%) | |||||

| < $20,000 | 26 (16.5) | 11 (8.1) | 15 (11.8) | 15 (9.9) | 67 (11.7) |

| $20,000-$34,999 | 30 (19.0) | 27 (19.9) | 22 (17.3) | 27 (17.9) | 106 (18.5) |

| $35,000-$49,999 | 28 (17.7) | 24 (17.6) | 27 (21.3) | 35 (23.2) | 114 (19.9) |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 28 (17.7) | 31 (22.8) | 30 (23.6) | 36 (23.8) | 125 (21.9) |

| ≥ $75,000 | 43 (27.2) | 35 (25.7) | 25 (19.7) | 33 (21.9) | 136 (23.8) |

| Unknown/Refused | 3 (1.9) | 8 (5.9) | 8 (6.3) | 5 (3.3) | 24 (4.2) |

| Body weight, kg, mean (SD) | 100.2 (14.6) | 102.6 (16.7) | 98.6 (15.8) | 101.5 (14.8) | 100.8 (15.5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 36.4 (3.9) | 36.3 (4.1) | 36.2 (3.8) | 36.7 (4.0) | 36.4 (3.9) |

4.2 Pretreatment Prevalence of Binge Eating

Binge eating was prevalent in 34.8% of the sample at baseline; 9.3% reported Severe Binge Eating (n = 53; M ± SD: 31.36 ± 3.98), 25.5% reported Moderate Binge Eating (n = 146; 21.34 ± 2.43), and 65.2% reported Mild/No Binge Eating (n = 373; 9.98 ± 4.69).

4.3 Effect of Treatment Dose on Binge Eating

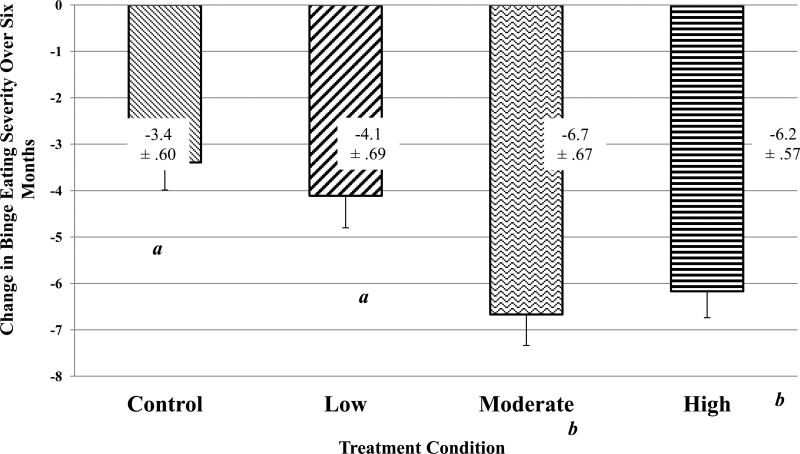

There was a significant interaction between treatment condition and time, F range (df = 3,568) = 6.16–10.08, ps < .001, partial ƞ2 range = .031–.051. Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc comparisons indicated that there were no significant differences in binge eating severity between treatment conditions at baseline, ps > .9. However, at Month 6, participants in the HIGH dose treatment condition reported significantly lower binge eating severity than those in CONTROL, p = .002, and LOW, p = .01; participants in the MOD dose treatment condition similarly reported significantly lower binge eating severity at Month 6 than those in CONTROL and LOW, ps < .001 (Table 2). Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc comparisons further indicated that participants in HIGH experienced significantly greater reductions in binge eating severity over six months than participants in both LOW, p = .01, and CONTROL, p = .001; participants in MOD also experienced significantly greater reductions in binge eating severity than participants in LOW, p = .004, and CONTROL, p < .001 (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Binge Eating Scale Scores at Baseline and Month 6 by Treatment Condition

| CONTROL | LOW | MOD | HIGH | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | n = 158 | n = 136 | n = 127 | n = 151 | n = 572 |

| Binge Eating Severity | |||||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 14.8 (8.9) | 15.1 (8.1) | 14.5 (8.2) | 15.0 (8.0) | 14.9 (8.3) |

| Month 6, mean (SD) | 11.5 (7.3)a | 11.0 (7.4)a | 7.9 (5.9)b | 8.7 (6.4)b | 9.8 (7.0) |

| Percentage Reporting Moderate or Severe Binge Eating | |||||

| Baseline, n (%) | 54 (34.2) | 47 (34.6) | 45 (35.4) | 53 (35.1) | 199 (34.8) |

| Month 6, n (%) | 28.4 (18.0)a | 22.6 (16.6)a | 5.6 (4.4)b | 14.3 (9.5)b | 70.9 (12.4) |

Note. Month 6 data are pooled across 10 imputations, and Month 6 standard deviations are averages derived from those imputations. Groups with dissimilar superscripts are significantly different, ps < .05.

Figure 1.

Change in Binge Eating Severity from Baseline to Month 6 by Treatment Condition

Figure 1. Mean (SE) change in binge eating severity from baseline to Month 6 across treatment conditions.

Note. Groups with dissimilar subscripts are significantly different, ps ≤ .01.

Chi-square analyses indicated that there were no significant baseline differences between treatment conditions in the proportion of participants reporting Moderate or Severe Binge Eating at baseline, p = .99. At Month 6, however, there were significant between-group differences in the proportion of participants reporting Mild/No Binge Eating, χ2(3) = 10.2–21.2, ps < .017 (Table 2). A significantly lower percentage of participants in the CONTROL (82.0%) and LOW (83.4%) conditions reported Mild/No Binge Eating at Month 6 than participants in the MOD (95.6%) or HIGH (90.5%) conditions. Additionally, an exact McNemar's test determined that there was a significant within-group difference in the proportion of participants reporting Mild/No Binge Eating at pre- and posttreatment, ps < .003; all treatment conditions had significantly greater proportions of participants reporting Mild/No Binge Eating at Month 6 compared to baseline (Table 2).

4.4 Month 6 Associations with Clinically Significant Improvements in Binge Eating Severity

Independent samples t-tests indicated significant effects of group (Clinically Significant Improvement Group vs. No Significant Improvement Group) on weight loss and dietary self-monitoring adherence, ps < .001, but not on percentage of treatment sessions attended, p = .50. Compared to the No Significant Improvement Group at Month 6, participants in the Clinically Significant Improvement Group reported greater percent weight losses, t(149) = −5.76, M ± SD: −10.6% ± 6.0 vs. −4.2% ± 5.7; greater decreases in BMI, t(149) = −5.59, −3.89 kg/m2 ± 2.3 vs. −1.53 kg/m2 ± 2.1; greater percent of days with dietary self-monitoring records completed, t(112) = 4.9, 76.3% ± 22.7 vs. 49.9% ± 26.1; and greater percent of days with caloric intake goals met, t(112) = 4.74, 55.8% ± 22.9 vs. 31.2% ± 21.4.

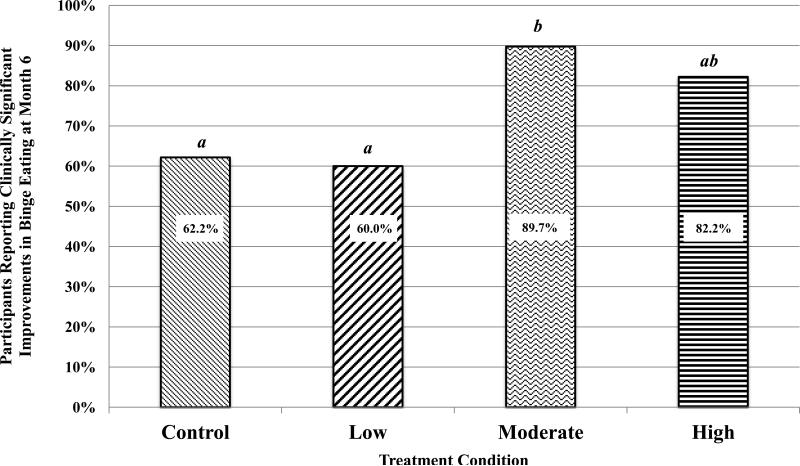

A one-way ANOVA indicated that the proportion of participants with Clinically Significant Improvements in binge eating over six months (i.e., from the Moderate or Severe Binge Eating categories to Mild/No Binge Eating) differed significantly across treatment conditions, F(3,115.994) = 4.25, p = .007. Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc analyses indicated that the MOD dose treatment condition had a greater proportion of participants who experienced clinically significant improvements in binge eating over six months than the LOW dose, p = .025, and CONTROL conditions, p = .03 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Participants Reporting Clinically Significant Improvements in Binge Eating at Month 6 by Treatment Condition

Figure 2. Proportion of participants who reported clinically significant improvements in binge eating over six months (i.e., from the Moderate or Severe Binge Eating categories to Mild/No Binge Eating) across treatment conditions.

Note. Groups with dissimilar subscripts are significantly different, ps ≤ .03.

4.5 Month 6 Associations with Pretreatment Binge Eating

Pretreatment binge eating severity predicted less improvement in binge eating severity over six months, B = −.49, t = −16.66, p < .001, and fewer percent of days with dietary self-monitoring records completed, B = −1.11, t = −3.07, p = .002. Pretreatment binge eating severity did not significantly predict percent of treatment sessions attended, p = .051, percent of days with caloric intake goals met, p = .09, or weight loss over six months, p = .95.

4.6 Associations between Race, Ethnicity, and Change in Binge Eating Over Six Months

There were no significant effects of race, t(149,14.816) = 1.578, p = .115, or ethnicity, t(149,1.021) = .442, p = .658, on change in binge eating severity over six months.

5. Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to determine the effects of three doses of a behavioral weight-loss treatment on participants’ self-reported binge eating severity. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to directly examine the impact of varied doses of behavioral treatment for obesity on binge eating severity. There were two major findings. All doses of a behavioral intervention for obesity improved participants’ binge eating, but a moderate or high dose of treatment (i.e., 16–24 sessions over six months) was associated with significantly greater reductions in binge eating severity than a low dose of treatment (i.e., eight sessions) or a nutrition education control condition. Significantly fewer participants in the MOD and HIGH dose treatment conditions (4.4% and 9.5%, respectively) reported Moderate or Severe Binge Eating at Month 6 than in the LOW dose and CONTROL conditions (16.6% and 18.0%, respectively), and a greater proportion of participants in the MOD dose treatment condition (89.7%) reported experiencing clinically significant improvements in binge eating over six months than in the LOW dose and CONTROL conditions (60.0% and 62.2%, respectively). Of note, it appears that the HIGH dose treatment condition did not provide additional benefits over the MOD dose treatment condition likely due to a diminishing rate of return on time spent in session; increasing the dose of treatment from 16 to 24 sessions over six months does not appear to add incremental benefit for participants’ binge eating symptoms. It is also possible that given the differing doses of treatment, results at Month 6 may reflect a lack of stability or durability of improvements in binge eating rather than a true effect of different doses of treatment (e.g., the two-month LOW dose treatment could have been more effective in producing benefits in binge eating, but the effects simply diminished over time and were less evident at Month 6).

Notably, the behavioral weight management program delivered in this intervention did not specifically address binge eating behaviors beyond the typical components of a standard behavioral intervention for obesity. Rather, it is likely that the program's emphasis on self-monitoring, regulating eating patterns, non-restrictive dietary recommendations, stress management techniques, and individual problem solving – which are also components of CBT for binge eating (Iacovino, Gredysa, Altman, & Wilfley, 2012) – address some of the underlying mechanisms that maintain binge eating behaviors. Specifically, researchers have argued that behavioral interventions for weight management that focus on self-monitoring and the establishment of regular eating patterns may reduce binge eating episodes (Niego, Pratt, & Agras, 1997). Given that interpersonal therapy (IPT) is effective at improving symptoms of binge eating (Wilson, Wilfley, Agras, & Bryson, 2010), it is also likely that increased contact with group members and interventionists in the higher-dose treatment conditions likely provided greater support for individuals who reported binge eating at baseline. Greater social support may have increased participants’ abilities to execute and maintain key behavioral changes that interrupt the maladaptive cycle of binge eating and restrictive dieting. As Berkman et al. (2015) concluded, behavioral weight-loss interventions may be a better choice for some obese individuals who endorse binge eating depending upon their goals for treatment; while CBT and other interventions targeting binge eating may more effectively reduce symptoms, behavioral weight-loss interventions do elicit symptom reductions and are more effective at short-term weight loss.

We found that compared to those who did not experience clinically meaningful improvements in binge eating severity, those who improved from the Severe or Moderate Binge Eating categories to the Mild/No Binge Eating category exhibited greater dietary self-monitoring adherence and larger weight losses. These findings suggest that clinically significant improvements in binge eating severity, or lack thereof, during a behavioral weight management program are related to treatment adherence and weight-loss outcomes. Considering that the BES is a self-report inventory and categories may reflect subjective interpretations of symptoms (Bulik, Brownley, & Shapiro, 2007), additional research is needed to ascertain the directionality of these associations.

Several prior studies have found higher rates of attrition among participants who report binge eating at baseline compared to those who do not (e.g., Teixeira et al., 2005). In the current study, pretreatment binge eating severity predicted less improvement in binge eating severity and lower percent of days with dietary self-monitoring records completed over six months, but did not predict treatment session attendance or participants’ ability to meet daily caloric intake goals. These results suggest that individuals who binge eat may avoid self-monitoring during periods of loss-of-control eating (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991). However, the findings showed that pretreatment binge eating severity was unrelated to treatment session adherence and attainment of caloric intake goals.

Self-reported binge eating severity at baseline was also not associated with poorer weight loss outcomes at Month 6. The majority of previous research, including a systematic review conducted by Teixeira et al. (2005), have similarly found that binge eating severity does not predict posttreatment weight loss following a behavioral intervention for obesity. The results of the current study indicate that obese adults who binge eat can be as successful as their non-binge eating peers in achieving weight reductions. What remains unknown is whether they demonstrate equivalent weight-loss outcomes over the long term.

Participants in the present study reported moderate and severe binge eating, but presence of symptoms on the BES is not equivalent to meeting diagnostic criteria for BED. Moreover, the lack of objective data on binge eating (i.e., presence of objective binge eating episodes on dietary self-monitoring logs), the use a self-report measure of binge eating symptomatology, and the focus on short-term outcomes at six months are limitations in the current study. Given that previous studies examining the effectiveness of behavioral weight-loss interventions for obese individuals utilized the clinical diagnosis of BED (e.g., Wilson et al., 2010; Grilo, Masheb, Wilson, Gueorguieva, & White, 2011; Munsch et al., 2007), we acknowledge that individuals with BED may not respond to behavioral weight-loss treatment in the same ways as those with elevated binge eating symptoms who do not meet full diagnostic criteria for BED. We also note that there may be issues with generalizability because the participants in this study were mostly white and female from rural counties in Florida. Additionally, 19.6% of BES data at Month 6 were missing, and we identified that these data were not Missing Completely At Random. We addressed this issue through the use of Multiple Imputation and controlled for variables that differentiated those with and without data. Nonetheless, our results should be interpreted with caution until the findings are replicated.

This study has a number of strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of various doses of behavioral treatment on participants’ binge eating severity. The study included a large sample (n = 572) of obese adults seeking a weight management intervention and had a low attrition rate (5.0%) over six months. The study also provided a sufficient number of participants who reported Moderate or Severe Binge Eating at baseline without missing data at Month 6 (n = 151) to permit an examination of participant characteristics and behaviors associated with improvements in binge eating and weight status.

In summary, this study highlights several important clinical implications regarding treatment-seeking obese adults who report moderate or severe binge eating. Our results indicate that low dose treatments with or without behavioral strategies elicit improvements in binge eating, but moderate (16 sessions) and high (24 sessions) doses of a behavioral intervention produce significantly greater improvements in binge eating severity. Although pretreatment binge eating severity predicted less improvement in binge eating severity over six months and fewer days with dietary self-monitoring records completed, pretreatment binge eating was not associated with decreased session attendance or poorer weight loss outcomes at six months. These findings highlight the benefits of standard behavioral weight management programs for obese adults who report binge eating. However, it remains unclear whether treatments tailored specifically to address binge eating produce outcomes superior to standard behavioral weight-loss treatment. Given that reductions in binge eating severity may be temporary (Hildebrandt & Latner, 2006; Niego, Pratt, & Argas, 1997), further research is needed to replicate these findings and to examine the effects of dose using a sample of individuals with obesity who meet criteria for BED as determined by diagnostic interviews. Future studies should also aim to evaluate whether improvements in binge eating elicited by behavioral weight management programs are sustained at follow-ups of one year or longer.

Highlights.

Examined effects of dose of behavioral treatment for obesity on binge eating.

Moderate or high doses were associated with greater reductions in binge eating.

Binge eating improvements were associated with treatment adherence and weight loss.

Acknowledgments

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida approved and monitored the parent study. The authors would like to acknowledge the participants for their time, as well as the graduate students, study staff, and research assistants who collected data for this study.

Role of Funding Source

Funding for the Rural LITE study was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; R01HL87800). NHLBI had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

All authors participated in this research. Dr. Michael Perri and Aviva Ariel jointly designed the current study. Dr. Perri designed the parent study and worked on drafts of the paper. Aviva Ariel completed the literature searches, conducted the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest with regards to this study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, Lohr KN, Cullen KE, Morgan LC, Bulik CM. Management and outcomes of Binge-Eating Disorder. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Brownley KA, Shapiro JR. Diagnosis and management of Binge Eating Disorder. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio AA, Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Mitchell J, Walsh BT. A comparison of the Binge Eating Scale, Questionnaire for Eating and Weight Patterns – Revised, and Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire with Instructions with the Eating Disorder Examination in the assessment of Binge Eating Disorder and its symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36(4):434–444. doi: 10.1002/eat.20057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Zwaan M. Binge Eating Disorder and obesity. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders. 2001;25(s1):S51–S55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, Liu L, Walsh BT. Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for Binge Eating Disorder: Two-year follow-up. Obesity. 2007;15(7):1702–1709. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(6):393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode RW, Ye L, Sereika SM, Zheng Y, Mattos M, Acharya SD, Chasens E. Socio-demographic, anthropometric, and psychosocial predictors of attrition across behavioral weight-loss trials. Eating Behaviors. 2016;20:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin AA, Niemeier HM, Hogan P, Coday M, Davis C, DiLillo VG, Yanovski SZ. Binge eating and weight loss outcomes in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes: Results from the Look AHEAD trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1447–1455. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, White MA. Cognitive–behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with Binge-Eating Disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(5):675. doi: 10.1037/a0025049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(1):86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt T, Latner J. Effect of self-monitoring on binge eating: Treatment response or ‘binge drift’? European Eating Disorders Review. 2006;14(1):17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovino JM, Gredysa DM, Altman M, Wilfley DE. Psychological treatments for Binge Eating Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2012;14(4):432–446. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0277-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keränen AM, Savolainen MJ, Reponen AH, Kujari ML, Lindeman SM, Bloigu RS, Laitinen JH. The effect of eating behavior on weight loss and maintenance during a lifestyle intervention. Preventive Medicine. 2009;49(1):32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, Deitz AC, Hudson JI, Shahly V, Benjet C. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;73(9):904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatzkin RR, Gaffney S, Cyrus K, Bigus E, Brownley KA. Binge Eating Disorder and obesity: Preliminary evidence for distinct cardiovascular and psychological phenotypes. Physiology & Behavior. 2015;142:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Levy RL, Sherwood NE, Utter J, Pronk NP, Boyle RG. Binge Eating Disorder, weight control self-efficacy, and depression in overweight men and women. International Journal of Obesity. 2004;28(3):418–425. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masheb RM, Lutes LD, Myra Kim H, Holleman RG, Goodrich DE, Janney CA, Damschroder LJ. High-frequency binge eating predicts weight gain among veterans receiving behavioral weight loss treatments. Obesity. 2015;23(1):54–61. doi: 10.1002/oby.20931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroshko I, Brennan L, O'Brien P. Predictors of dropout in weight loss interventions: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(11):912–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch S, Biedert E, Meyer A, Michael T, Schlup B, Tuch A, Margraf J. A randomized comparison of cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss treatment for overweight individuals with Binge Eating Disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(2):102–113. doi: 10.1002/eat.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niego SH, Pratt EM, Agras WS. Subjective or objective binge: Is the distinction valid? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22(3):291–298. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199711)22:3<291::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurkkala M, Kaikkonen K, Vanhala ML, Karhunen L, Keränen AM, Korpelainen R. Lifestyle intervention has a beneficial effect on eating behavior and long-term weight loss in obese adults. Eating Behaviors. 2015;18:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri MG, Limacher MC, Castel-Roberts K, Daniels MJ, Durning PE, Janicke DM, Martin AD. Comparative effectiveness of three doses of weight-loss counseling: Two-year findings from the Rural LITE trial. Obesity. 2014;22(11):2293–2300. doi: 10.1002/oby.20832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike KM, Dohm FA, Striegel-Moore RH, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG. A comparison of black and white women with Binge Eating Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1455–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond NC, de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Ackard D, Thuras P. Effect of a very low calorie diet on the diagnostic category of individuals with Binge Eating Disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;31(1):49–56. doi: 10.1002/eat.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Devlin M, Walsh BT, Hasin D, Wing R, Marcus M, Agras S. Binge Eating Disorder: A multisite field trial of the diagnostic criteria. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1992;11(3):191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL. Should Binge Eating Disorder be included in the DSM-V? A critical review of the state of the evidence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:305–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ, Allison KC. Two forms of disordered eating in obesity: Binge eating and night eating. International Journal of Obesity. 2003;27(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira P, Going S, Sardinha L, Lohman T. A review of psychosocial pre-treatment predictors of weight control. Obesity Reviews. 2005;6(1):43–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman GM. Binge Eating Scale: Further assessment of validity and reliability. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 1999;4(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Vocks S, Tuschen-Caffier B, Pietrowsky R, Rustenbach SJ, Kersting A, Herpertz S. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for Binge Eating Disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43(3):205–217. doi: 10.1002/eat.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Bryson SW. Psychological treatments of Binge Eating Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT. Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2011;34(4):773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]