Abstract

An important aspect of human thought is the value we place on unique individuals. Adults place higher value on authentic works of art than exact replicas, and young children at times value their original possessions over exact duplicates. What is the scope of this preference in early childhood, and when do children understand its subjective nature? On a series of trials, we asked three-year-olds (N=36) to choose between two toys for either themselves or the researcher: an old (visibly used) toy versus a new (more attractive) toy matched in type and appearance (e.g., old vs. brand-new blanket). Focal pairs contrasted the child's own toy with a matched new object; Control pairs contrasted toys the child had never seen before. Children preferred the old toys for Focal pairs only, and treated their own preferences as not shared by the researcher. By 3 years of age, young children place special value on unique individuals, and understand the subjective nature of that value.

An important aspect of human thought is the significance we place on unique individuals. From early in development, people track individual agents and objects through space and time (Rich & Bullot, 2014; Xu & Carey, 1996), tag individual people (and sometimes animals and objects) with proper names (Hall, 2009), determine identity and ownership based on an item's historical path (Gelman, Manczak, & Noles, 2012; Gutheil, Gelman, Klein, Michos, & Kelaita, 2008; Nancekivell & Friedman, 2014), and treat owned objects as non-fungible (McEwan, Pesowski, & Friedman, 2016). Additionally, adults in modern Western societies place value (positive or negative) on certain objects because of their past. Objects with special histories are displayed in museums, auctioned off at high prices, and prized as religious relics (Frazier, Gelman, Wilson, & Hood, 2009; Newman & Bloom, 2014; Newman, Diesendruck, & Bloom, 2011), and objects that have been owned by criminals are treated with disgust (Nemeroff & Rozin, 1994). This sensitivity to individual objects reflects an early-emerging and pervasive attention to an item's history--its origins, who has owned it, and where it has been (Bloom, 1996; Newman, in press).

The question of when and why unique objects have special value is a matter of debate. Placing value on unique objects may be a culturally specific perspective that requires extensive immersion in Western traditions (Evans, Mull, & Poling, 2002). Additionally, authenticity per se may play a relatively minor role in evaluation of items in a museum display (Hampp & Schwan, 2014). Thus, people may require experience with museums, economic markets, and/or the signaling value of luxury objects in order to value object features that are neither obvious nor functionally relevant. In contrast, others have proposed that high evaluation of unique objects follows from a foundational, early-emerging belief that objects are imbued with their history (Friedman, Vondervoort, Defeyter, & Neary, 2013; Gelman, 2013; Nancekivell & Friedman, 2014; Newman, in press). On this view, even young children should care about an object's past when evaluating its desirability. In partial support of this latter position, preschool children judge that celebrity possessions belong in museums, and that people would pay more money for them than comparable objects owned by non-celebrities (Frazier & Gelman, 2009; Gelman, Frazier, Noles, Manczak, & Stilwell, 2015). On the other hand, when asked about the monetary value of original creations versus comparable brand-new objects (e.g., the very first teddy bear vs. a brand-new teddy bear), children did not accord higher value to the original creations (Gelman et al., 2015), and reported that they themselves would prefer the brand-new objects (Frazier & Gelman, 2009). Yet understanding the value of original creations may require knowledge of how cultural artifacts change over time, which young children do not yet appreciate.

Children's attitudes toward their own possessions provide an intriguing arena within which to examine these questions further. It is estimated that roughly 60% of young children in middle-class U.S. families have an attachment to a non-social object, such as a blanket or soft toy (Lehman, Arnold, & Reeves, 1995; Passman & Hallonen, 1979), and such attachments seem to be specifically tied to a particular item. Parents report that, by 6 months of age, most infants show a preference for at least one “specific, individual, favorite object” (Furby & Wilke, 1982). By 2 years of age, children with a “security” blanket prefer to play with, and to be in close proximity to, their own blanket rather than another blanket that obviously differs in appearance (Weisberg & Russell, 1971). By early childhood, children believe that their attachment objects have special histories, with two-thirds of children 4-5 years of age reporting that they possessed their special object from infancy (“I've always had Blankie”; Lehman et al., 1995). Thus, attention to unique individuals is potentially a foundational aspect of young children's interactions with objects.

A striking example of the early value of unique objects is provided by Hood and Bloom (2008), who found that 4.5-year-old children with a strong emotional attachment to a special object (e.g., stuffed toy or blanket) chose that original object over an exact duplicate, after the researcher convinced the child that a duplicating machine could generate such an entity. In a second study, Hood and Bloom found that older children (6.7 years of age) placed higher value on an authentic object (spoon or goblet once owned by Queen Elizabeth II; participants were British children) than an exact duplicate. These results demonstrate children's early sensitivity to unique individuals in the absence of perceptible differences--although, as noted by the authors, it is possible that children assumed that the copies differed from the originals in subtle, non-obvious ways.

Altogether, the results to date suggest that unique objects with special history have value early in childhood. However, there are several unresolved questions regarding the scope of the phenomenon, with implications for why and how children hold such representations. These questions include: whether the value of a unique object is thought to be shared by others; whether this understanding is a general perspective children have about owned objects or is instead restricted to special attachment objects, or to children who possess attachment objects; whether original objects are deemed better than even newer, more attractive versions; and whether this understanding can be found below 4 years of age. We discuss each of these issues below.

Is the value of a unique object thought to be shared by others? To what extent are owned objects thought to reflect a special connection to the individual owner based on their shared history? If authentic objects are valued because of a belief in their unique essence (Bloom, 2010), then this belief need not be shared with others, and indeed the specificity of an owned object's history may encourage a belief that its value would not be shared by others. As the saying goes, “One man's trash is another man's treasure.” Alternatively, authentic objects may be valued because they signal one's taste and status (Pinker, 2003), in which case this value must be assumed to be shared with others, rather than being a subjectively held preference. Possession of an authentic object does not have signaling value if others read the signals differently. Once again, the available evidence is mixed. Understanding that the greater value of owned objects is specific to the owner could potentially emerge quite early, because by 18 months of age infants recognize the subjectivity of desires, such that different people can have different preferred foods (Repacholi & Gopnik, 1997). On the other hand, self-report measures suggest that young children may have some difficulty appreciating the subjective and person-specific nature of attachment to special objects, perhaps because attachment to a special object is more powerful than preference for a food type. Lehman et al. (1995) interviewed children 4-8 years and found that most reported that their own attachment object could comfort another person, even though they also reported that the reverse could not happen (i.e., another person's attachment object couldn't comfort the child). They often explained the special properties of their favored item as inherent in the object: “Mine is more specialer.” Thus, young children may have a representation of unique objects as objectively better than other items.

Which items are treated as unique? Is a preference for unique objects a general expectation about owned objects, or a special way of reasoning about attachment objects? Hood and Bloom (2008, Study 1) found that, among their younger children, a preference for unique individuals was found only among those with attachment objects. Given that many children do not develop strong object attachments, this may suggest that early in development, attention to uniqueness may be an individual difference rather than a broadly available perspective. However, prior work did not distinguish individual differences in children's attachment, from the types of toys being tested. Specifically, children with attachment objects were asked about their sleep objects, whereas those without attachments were asked about non-sleep toys. Thus, an alternative possibility is that certain kinds of objects elicit preferences for unique objects more than others. For example, children may particularly care about unique objects when they are dolls, stuffed animals, or other animate representations. Examining different types of objects would also provide important cues regarding the the mechanisms by which objects attain special value.

Do children prefer their original objects to newer, “better” versions? Prior work has shown that children prefer their original object to a perceptually identical one, even when the duplicate was produced by a special, “cool” machine (Hood & Bloom, 2008). However, if children prize historical continuity in unique objects, then a further prediction is that they should prefer objects that carry visible traces of that history, even when such items are worn, scratched, ragged, or otherwise less attractive. In other words, history may be prized not only when all other features are equated and thus controlled, but even in the strong case when history is pitted against beauty. The existing literature is mixed on this point. On the one hand, anecdotal reports suggest that children dislike changes in their attachment objects, to the point of objecting to parental efforts to wash or clean them (Winnicott, 1953). When children with an attachment object were asked if they would hypothetically be willing to trade it for a brand-new object, only 20% of 4- to 8-year-olds said they would be willing to make the trade (Lehman et al., 1995). On the other hand, those who did wish to trade mentioned cleanliness and newness as reasons to trade it in. Furthermore, by 3 years of age, children dislike items that are dirty or come into contact with a contaminant such as a leaf, and view this as a legitimate reason to reject them (Legare, Wellman, & Gelman, 2009), and by kindergarten age, children place lower monetary value on objects that are old and visibly worn (Gelman et al., 2015). Thus, an unresolved question is whether marks of history add to or subtract from the value of owned objects. If historical continuity per se is valued, then we may find that young preschoolers prefer shabby originals to shiny replacements, despite their well-known attention to surface appearances.

Do younger children place value on unique objects? Prior work examining children's preferences or monetary evaluations of authentic owned objects have not examined children younger than 4.5 years of age (Gelman et al., 2015; Hood & Bloom, 2008; Lehman et al., 1995). In contrast, observational and parent-report studies on attachment objects reviewed earlier have typically focused on infants and young children below 4 years of age, yet did not directly test the uniqueness of children's attachments. Thus, there is a gap in the evidence, with no direct tests of object preferences in children younger than age 4.5 years of age. This is a particularly critical period to consider, given important changes in children's concepts from ages 3 to 5, in children's appearance/reality contrasts (Deák, Ray, & Brenneman, 2003), perspective-taking (Moll, Meltzoff, Merzsch, & Tomasello, 2013), and spontaneous reference to ownership in their explanations (Nancekivell & Friedman, 2016).

The Present Study

The present study was designed to assess the four questions described above, concerning the scope of young children's preference for unique objects. First, we assessed whether preschool-aged children prefer their own, worn objects to brand-new replacements. On each of a series of trials, we asked children to choose between their own toy and a newer, more attractive version (e.g., old blue blanket versus brand-new blue blanket). This allowed us to test whether object history overrides observable features, such as newness or attractiveness, in explaining the strength of children's attachment to an object. Second, we asked not only about children's own preferences, but also about the experimenter's preferences, to assess whether children judged value to be shared by others or specifically tied to their own history with the object. Third, we controlled for object type by asking all children, those with an attachment object and those without, about the same types of toys (sleep objects such as blankets, animate representations such as stuffed animals, and inanimate toys such as cars). This permitted us to disentangle effects due to whether or not the child had an attachment object, from effects due to the nature of the object. Finally, the children in the current study were younger than in past work (3-year-olds, versus 4- to 6-year-olds).

Method

Participants

Participants were 36 children between the ages of 2.95 and 4.0 (M age = 3.45, SD=0.31; 18 boys, 18 girls). Children were predominantly middle-class and white (64% White, 3% African American, 3% Asian, 3% Latino, 14% Biracial, and 14% Unreported). An additional 3 children were tested but excluded from the sample because appropriate toys were not available for the testing session. All children were from a midsize city in the Midwestern United States. Seventy-one adults recruited via Amazon's Mechanical Turk rated the materials for similarity and relative age (see Materials).

Materials

Each child saw six item pairs that contrasted an old item (previously used and visibly worn) with a new item (never used and visibly unmarked), of the same type and appearance. For example, if the old item was a worn, faded, slightly tattered blanket, the new item was a brand-new version of the same type of blanket. For each participant, three of the six item pairs were Focal Object pairs, contrasting an old item brought from the child's home with a new, lab-purchased item. Focal Object pairs were individualized such that each child received a different set, yielding a total of 108 pairs across the entire study sample (36 participants × 3 pairs each; see Table 1 for summary).

Table 1.

Focal objects brought from home, as a function of object type.

| Sleep | Animate | Inanimate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Object type | |||

| • Cloth (blanket, diaper, pillow, clothing) | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| • Animal/Doll | 17 | 30 | 0 |

| • Toy vehicle | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| • Other toy | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| • Other | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Percent with faces | 58% | 100% | 36% |

In contrast, three of the six item pairs were Control Object pairs, for which both the old and new items were provided by the lab. The Control Object pairs were identical for all participants. Both Focal and Control object pairs included one pair of sleep objects, one pair of animate objects, and one pair of inanimate objects. For Focal pairs, these were: a blanket, pillow, stuffed animal, or other item the child currently slept with (Sleep), a stuffed animal, doll, or action figure the child currently played with (Animate), or a toy the child currently played with that was not an animal or doll, such as a vehicle or phone (Inanimate). For Control pairs, these were: a small, silk-edged “Silkie” blanket (Sleep), a stuffed husky dog (Animate), and a plastic boat (Artifact). See Figure 1 for examples of Focal object pairs, as well as all three Control object pairs. Two additional pairs of objects were used during warm-up trials: a red toy car and a white sock; a yellow rubber duck and an unpainted wooden rectangular block.

Figure 1. Control object pairs and sample Focal object pairs. (Old item in each pair is on the left.).

Prior to their child's participation, parents were requested to select three toys to bring to the lab that the child actively played with, that were clearly used and well-loved, not new toys: a sleep object, an animate object, and an inanimate object. For the Focal sleep object, the parents were instructed to bring the child's attachment object (defined as “an object that your child regularly sleeps with, has possessed for at least 1/3 of their life, and that provides comfort or helps your child get to sleep”), if he or she had one. The parent emailed the lab a picture of the three objects that would be used in the study. Based on these photos and parent descriptions, the researchers purchased new versions, matched as closely as possible to the toys from home, in time for the child's session in the lab.

Ratings

To confirm that items in each pair were closely matched, we asked adults (N=36) to provide similarity ratings between the two items in each pair, from photographs. M-Turkers rated 106 item pairs (103 Focal Pairs and 3 Control Pairs; due to experimenter error, 5 Focal Pairs were omitted) as well as 9 dissimilar pairs of objects (included just for the purposes of comparison in the ratings task, and not included in the study with children), on a scale of 1 (“very different”) to 7 (“identical”). Mean ratings were 5.12 and 5.32 for Focal and Control pairs, respectively, indicating that paired items were highly similar. Focal and Control pairs did not significantly differ from one another by paired-t test, p = .31, but pairs of both test types were more similar than the dissimilar item pairs (M=1.75), ps < .001.

To confirm that old items were visibly older-looking than new items, a separate set of MTurkers (N=35) were asked to judge which of the two items in each pair was older than the other, for 108 item pairs (105 Focal Pairs and 3 Control Pairs; due to experimenter error, 3 Focal Pairs were omitted). On average, adults' accuracy at judging which item was older was 71% for Focal pairs and 86% for Control pairs, both of which were significantly above chance, ps < .001. Accuracy was higher on Control than on Focal pairs, ps < .001. These ratings provided a conservative test, as minor signs of wear (e.g., scuff marks) that were visible when viewing the objects up-close were difficult to detect in the photographs. To demonstrate, we asked an additional set of 13 adults to provide old-new judgments for the inanimate Control pair of objects (boats), and compared their responses to the MTurk ratings of photographs of the same items. Accuracy was substantially higher when judging the actual objects (94%) compared to photos of the same objects (63%), p < .05.

Procedure

Participants were tested individually in a quiet, child-friendly room in an on-campus laboratory. Sessions were video-recorded. Children received a Preference task, a vocabulary assessment (PPVT), and an Own-Object Recognition task. Parents filled out a set of questionnaires (described below).

The Preference task consisted of two blocks (Child-Preference, Researcher-Preference) of six trials each, with a warm-up trial prior to the start of each block, for a total of 14 trials. The researcher introduced the task by explaining that she had some things to show the child, and some of them were things that the child brought from home. Then, on each trial, participants saw a pair of objects as described in the Materials section, presented side-by-side on a child-size table. In the Child-Preference block of trials, the child was asked, “Which one do you [pointing to child] like best?” In the Experimenter-Preference block, the child was asked, “Which one do I [pointing to herself] like best?” The participant responded by pointing to one of the two objects in the pair. No feedback was provided. Left-right ordering of the old vs. new item was counterbalanced within participant, and the order of the blocks, the order of presentation of the six pairs of objects within each block, and the side on which the old item was presented to the child were counterbalanced across participants.

The warm-up trials each compared a toy to a non-toy (e.g., toy car vs. sock), and served to give the children practice on the task, and to ensure that they understood the instructions. Which warm-up pair was assigned to which block was counterbalanced, as was the left-right orientation. Children performed above-chance at selecting the toy versus the non-toy on both the child warm-up and the researcher warm-up (86% and 78% respectively, ps < .001), and the two trials did not differ from one another, t(35) = 1.00, p = .324.

Following the Preference tasks, the child was administered the PPVT™-4 (Dunn & Dunn, 2012). Then children's ability to recognize their own toys from home was tested by presenting each of the three Focal Object pairs, one pair at a time (i.e., an old and a new item, side-by-side), and asking for each, “Which one is yours?” The order of presentation of the three pairs of Focal Objects and the side of presentation of the child's own old toy were counterbalanced across participants.

At the end of the session, the experimenter took photos of each of the three Focal Object pairs, both the child's own old object and the new object, for later use in the adult ratings (described in Method).

Parent Questionnaires

During the child testing session, the parent filled out four questionnaires: a Toy Questionnaire (24 questions about the strength of the child's attachment to the toys the child brought to the lab [8 questions × 3 toys]; see Appendix), an Attachment Questionnaire (five questions for parents who reported that their child had an attachment object; aside from the first question which simply asked whether the child had an attachment object, these were included for exploratory purposes only and will not be reported further), the Children's Saving Inventory (23 questions about the child's tendency to save objects and toys, rated on a 5 point scale scale from 0 [“None”, “Never”, “Not at all”] to 4 [“Almost all/Completely”, “Very often”, “Extreme”]; Storch et al., 2011), and the short form of the Children's Behavior Questionnaire (94 questions about the child's behavior rated on a scale from 1 [“Extremely Untrue”] to 7 [“Extremely True”]; Putnam & Rothbart, 2006).

Results

The results are reported in four sections: (1) Preference Task, (2) Own-Object Recognition Task, (3) Attachment measures, and (4) PPVT, Children's Saving Inventory, and Children's Behavior Questionnaire.

Preference Task

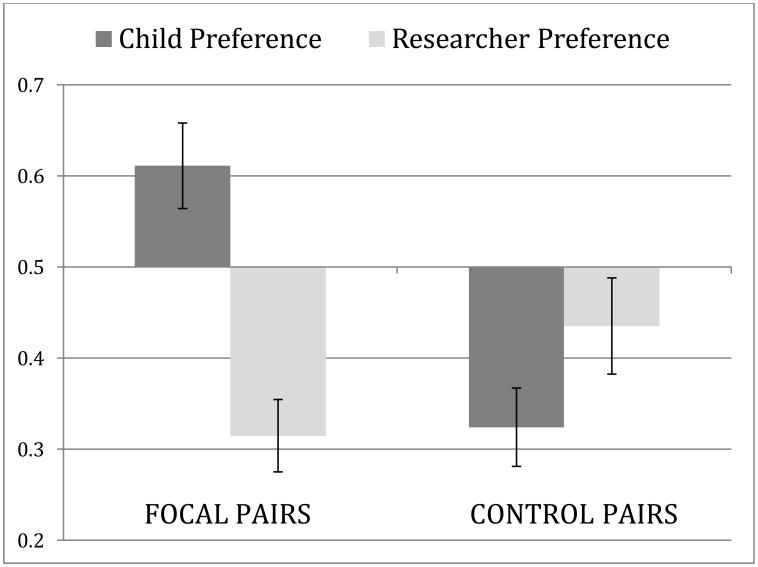

Our primary focus was children's performance on the Preference task, permitting us to test three questions: (1) Did children prefer their old objects from home to the newer, matched objects? (2) Did children prefer their old objects from home more than they preferred old objects from the lab? (3) Did children believe that the experimenter would share their preferences? We conducted a 2 (task: Child Preference, Researcher Preference) × 2 (item type: Focal Pairs, Control Pairs) repeated measures ANOVA, with mean number of old-object choices (out of 3) as the dependent variable. There were no significant main effects of task or item type. However, there was a significant task × item type interaction, F(1,35) = 20.86, p < .001, ηp2 = .37. Post-hoc tests revealed that children preferred the old Focal objects more than they judged that the researcher would (61% vs. 32%), p < .001, but that they preferred the old Control objects at the same rate as they judged that the researcher would (32% vs. 44%), p = .103. Furthermore, they preferred the old item more in Focal than Control Pairs, p < .001, but they showed the reverse pattern when judging the researcher's preferences, reporting that the researcher would prefer the old item more in Control than Focal Pairs, p = .051. We also compared scores to chance (50%). For Focal Pairs, children selected the old item above chance, t(35) = 2.37, p = .024, indicating a preference for their original toys. In contrast, for Control Pairs, children preferred the old item below chance, t(35) = -4.09, p < .001, indicating that for items they had not seen before, the new items were clearly more attractive. In contrast, on the Researcher-Preference trials, children selected the old item below chance for Focal Pairs, t(35) = -4.66, p < .001, and at-chance for Control Pairs, t(35) = -1.23, p = .23.

We next conducted a 2 (task: Child Preference, Researcher Preference) × 2 (item type: Focal Pairs, Control Pairs) repeated measures ANOVA on each of the toy types separately (Sleep object, Animate object, and Inanimate object), with selection of the old object as the dependent variable (see Table 2 for the results). The analyses for both the Sleep pairs and the Animate pairs again revealed no main effects of task or item type, but significant task × item type interactions, F(1,35) ≥ 7.68, ps < .01, ηp2s ≥ .18. In contrast, there were no significant effects for the Inanimate pairs, all ps ≥ .37.

Table 2.

Mean preference judgments (out of 1), as a function of Task, Item Type, and Toy Type, with SDs in parentheses.

| Sleep | Animate | Inanimate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FOCAL PAIRS: | |||

| • Child Preference | .72 (.45) | .61 (.49) | .50 (.51) |

| • Researcher Preference | .25 (.44) | .31 (.47) | .39 (.49) |

| CONTROL PAIRS: | |||

| • Child Preference | .31 (.47) | .22 (.42) | .44 (.44) |

| • Researcher Preference | .47 (.51) | .42 (.50) | .42 (.50) |

Finally, we conducted correlations between children's selection of the old items on the Focal Pair trials, and the adult similarity ratings and old-new judgments for the Focal Pairs (see Method for details). This allowed us to test whether variation in the items might account for the obtained patterns of results. For example, perhaps children preferred the older item when it was less visibly used, or when it was more dissimilar from the new item. We conducted 12 correlations: 2 kinds of adult ratings (similarity, old-new) × 2 tasks (Child-Preference, Researcher Preference) × 3 toy types (Sleep, Animate, Inanimate). None of the 12 correlations was significant, suggesting that children's preferences were due neither to individual variation in item similarity, nor to the perceived relative age of the items.

Own-Object Recognition Task

We next examined whether children could accurately identify their toys from home, on the Own-Object Recognition task that took place at the end of the testing session. Not only was this likely to be a prerequisite for selecting owned objects on the Preference tasks, but it is also of interest in its own right, given the subtle differences between the old and new versions of each object. Children performed extremely well, selecting their old object versus the newer object 97%, 94%, and 83% of the time, for Sleep, Animate, and Inanimate objects, respectively, greater than chance (50%), all ps < .001. A repeated-measures ANOVA indicated no significant effects of object type.

All of the ANOVA results reported in the Preference Task section, above, replicated when we included only those trials for which children correctly identified their own object on the Own-Object Recognition Task.

Attachment Status

We defined an attachment object as an object that a child regularly sleeps with, has possessed for at least 1/3 of their life, and that provides comfort or helps the child get to sleep, but not a bottle or pacifier. Based on parent report using this definition, 23 of the 36 participants had an attachment object and 13 did not. Attached and non-attached children did not significantly differ from one another on any of the post-test measures (PPVT, CSI subscales, or CBQ subscales), using t-tests with Bonferroni's correction.

Of key interest was how children performed on the Preference Task as a function of their attachment to the objects from home. We first examined whether children with an attachment object differed from children without an attachment object, in their preference for the old items in the Focal pairs. We conducted t-tests on each of the three items separately (Sleep, Animate, Inanimate) as well as the composite score (summing over the three items). None of these four t-tests yielded a significant difference. Thus, attachment status per se does not predict performance on this task. Additionally, we conducted a supplementary analysis of those children (n=13) who were reported by their parents to have no attachment object. Planned comparisons indicated that children without an attachment object selected the old Focal object more often for themselves than for the experimenter (Ms = .59, .23), t(12) = 2.94, p = .012, but selected the old Control object equally often for themselves as the experimenter (Ms = .38, .36), t(12) = 0.25, p = .81.

We also conducted a series of analyses focusing on each of the three item types (Sleep, Animate, Inanimate), given that different children were attached to different objects (19 to the Sleep object, 6 to the Animate object, and 6 to the Inanimate object; scores sum to more than 23 because some children had multiple attachment objects). Specifically, we conducted more sensitive tests by examining how degree of attachment to each toy predicted their preference for that unique toy on the Preference Task. Degree of attachment to a given toy was measured by averaging parent responses on questions 3-8 on the parental Toy Questionnaire regarding that toy. Table 3 provides the data from the Toy Questionnaire for each of the three toy types.

Table 3.

Parental responses on the Toy Questionnaire for each of the three toy types, to which children were attached (ns = 19 for Sleep, 6 for Animate, 6 for Inanimate) or unattached (ns = 17 for Sleep, 30 for Animate, 30 for Inanimate), as well as overall (n = 36); SDs in parentheses.

| Sleep | Animate | Inanimate | Effects of toy type* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| (Q1) Object name (%) | ||||

| • Attached | 95% | 100% | 100% | |

| • Unattached | 53% | 73% | 50% | |

| • Overall | 75% | 78% | 58% | n.s. |

|

| ||||

| (Q2) Awake time with object (hours/day) | ||||

| • Attached | 2.53 (1.58) | 3.50 (2.07) | 2.17 (1.17) | |

| • Unattached | 1.50 (3.31) | 1.49 (2.17) | 1.50 (2.61) | |

| • Overall | 2.09 (2.58) | 1.84 (2.26) | 1.64 (2.46) | n.s. |

|

| ||||

| (Q3-8) Composite attachment score (1-10 scale) | ||||

| • Attached | 6.54 (1.58) | 7.25 (1.59) | 6.06 (1.65) | p < .001 |

| • Unattached | 3.08 (1.11) | 3.20 (1.35) | 2.28 (0.93) | |

| • Overall | 4.90 (2.22) | 3.87 (2.06) | 2.91 (1.77) | |

Effects of toy type were examined for the overall sample only; on the Composite attachment score, all three items differ significantly from each other, ps < .05.

A binomial logistic regression revealed that selecting the old toy from home was associated with higher scores on the composite attachment measure for the Sleep toy (odds ratio = 1.57, B = .45, SE B = .22, χ2(1) = 4.10, p = .043), and a non-significant trend for the Animate toy (odds ratio = 1.48, B = .39, SE B = .22, χ2(1) = 3.17, p = .075), but no relation for the Inanimate toy (odds ratio = 1.10, B = .98, SE B = .18, χ2(1) = 0.31, p > .57). We also calculated Pearson correlations between the composite attachment scores and children's selection of the old object from home on the Child-Preference Task. Children's preference for the Sleep object correlated significantly with the composite attachment score for the Sleep object, Pearson correlation of .36, N = 36, p = .031. Children's preference for the Animate object showed a non-significant trend for correlating with the composite attachment score for the Animate object, .32, N = 36, p = .061. No significant correlation was obtained for the Inanimate object, -.09, p = .62.

Finally, we examined whether attachment status predicted children's performance on the Own-Object Recognition Task. For each of the original Focal objects, we conducted a Pearson's correlation between the child's score on the Own-Object Recognition Task, and the composite measure of attachment. None of the three correlations was significant or even approached significance (correlations ranging from .08 to .23, ps ranging from .17 to .63).

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to determine when and why young children place special value on owned objects, even though ownership as such is non-visible and abstract (Friedman & Ross, 2011; Gelman et al., 2012, 2016; Hood & Bloom, 2008). On a series of trials, three-year-olds judged their own and the researcher's preferences for an old (visibly used) toy versus a new (more attractive) toy matched in type and appearance (e.g., old vs. brand-new stuffed dog). Focal pairs contrasted the child's own toy with a matched new object; Control pairs contrasted toys the child had never seen before. This design permitted a test of four key questions: (1) Do children prefer their original objects to newer, “better” versions? (2) Do children think that the value of a unique object is shared by others? (3) Which items are treated as unique? (4) Do children below 4.5 years of age place value on unique objects? Below, we summarize and discuss the data in terms of these questions.

Do children prefer their original objects to newer, “better” versions? Yes. Children preferred their original, visibly used objects to newer replacements that were matched in overall appearance, indicating that unique objects have special value in early childhood. Children's preferences did not simply indicate a penchant for old objects, because they avoided the old objects in the control object pairs, preferring the newer objects in such sets above chance. Instead, oldness was negatively valenced in novel objects, but positively valenced in familiar owned objects. The effect is also not just an overall preference for familiar items, because children did not show a preference for the old (familiar) item on the inanimate sets (despite accurately identifying them). Finally, children's preferences did not reflect aesthetic preferences for particular features or colors of the objects, as the items were matched closely for appearance, and degree of similarity between old and new items did not predict children's preference for the old items. Instead, the findings indicate that children's own objects are viewed as uniquely desirable.

Is the value of a unique object thought to be shared by others? No. Children understood that their own objects have special value only to themselves. For the focal pairs, children preferred their own old objects from home above chance, but they expected the experimenter to prefer such objects below chance (and to select the new objects instead). This result indicates that children have not simply recalibrated the features of these objects (e.g., viewing the object's idiosyncrasies as inherently of greater value), but rather have determined value in terms of each person's connection to that object. As further evidence that children understood the subjective nature of unique objects, they predicted that the researcher would prefer the old Control objects (which came from the lab) over the old Focal objects (which came from the child's home). Not only is this pattern the reverse of children's own preferences, but also it intriguingly suggests that perhaps children expect others to develop their own special object attachments—an idea that would need to be tested more directly in future research. The person-specific nature of children's judgments also indicates that higher evaluation of unique objects does not strictly reflect social signaling. If that were the case, then children should have expected the researcher to show the same evaluations. Instead, these findings are consistent with an early belief that an object's value is unique to the individual owner who shares a history with that object, and in this sense that possessions are extensions of the self (Belk, 1988; Rochat, 2011).

Which items are treated as unique? We found that a preference for unique objects does not apply only to children who have attachment objects; children without attachment objects also selected the old Focal object more often for themselves than for the experimenter. There were also no overall differences as a function of whether or not children had an attachment object. Thus, we did not find that children with attachment objects behave in a qualitatively distinct way from children without attachment objects. However, we did find more targeted effects of children's attachment to a particular object (e.g., attachment to a sleep object correlated with preference for the old sleep object; attachment to an animate object correlated with preference for the old animate object). This more fine-grained level of analysis indicates that attachment to a particular object—though not necessary for placing higher value on it—did intensify the effect.

Additionally, there were important object type differences: uniqueness was valued for sleep objects and animate toys, but not for inanimate toys. Indeed, for inanimate objects, children's degree of attachment did not predict their preferences (in contrast to the patterns for sleep and animate objects, where as stated above, the more attached children were to a particular object, the more they preferred that unique object). The distinction between animate and inanimate items provides an interesting analogue to the domain-specificity of proper names in language, wherein animate items (people and animals) are more nameable than inanimate objects (Hall et al., 2004). However, in contrast to a domain-specific perspective, the sleep objects that children were attached to were as likely to be inanimate items (blanket or cloth diaper; 53%) as to be animate toys (stuffed animal or doll; 47%), and all but one of the attachment objects across object types received proper names from their child owners (see Table 3). These results suggest that attachment to unique objects is not limited to, or strictly determined by, animacy per se.

Do younger children place value on unique objects? Yes. This study provides the first demonstration of a general preference for unique objects in children as young as 3 years of age. The age at which children demonstrate this preference is notable, given that treating an attachment object as special to the self but not others—despite a more attractive competing choice—requires skills that are still developing between 3-5 years of age, including appearance-reality understanding, perspective-taking, and sensitivity to non-visible aspects of ownership (Deák et al., 2003; Moll et al., 2013; Nancekivell & Friedman, 2016). Although not our primary focus, it is also striking how attuned these young children were to subtle featural differences indicating the uniqueness of their own objects. Children easily identified which object in each focal pair was their own (overall 90% accuracy) despite only slight differences in their appearance, and this was true regardless of the child's attachment to the object being tested. That 3-year-olds attend to and remember unique yet subtle details of their owned objects suggests that ownership may highlight the uniqueness of objects and attention to detail (see Ashby, Dickert, & Glöckner, 2012, for a related finding with adults), a possibility that would be interesting to test more directly in the future.

Several important questions remain for future research. Perhaps most centrally, what are the mechanism(s) by which an individual object becomes valued for its uniqueness and history, and thus non-interchangeable with others of the same kind? To what extent do features of the object pull for this sort of construal, and to what extent do certain experiences promote this way of thinking? We propose that ownership status, emotional attachment, and anthropomorphism may all play a significant role. With regarding to ownership, prior research indicates that the mere act of assigning ownership encourages an individual to place higher value on an object, as evident in the endowment effect, in which even ordinary objects such as mugs and keychains increase in value once they come into someone's possession (Morewedge & Giblin, 2015; Thaler, 1980). The endowment effect has been documented in young children as well as adults (Gelman et al., 2012; Harbaugh, Krause, & Vesterlund, 2001; Hood, Weltzien, Marsh, & Kanngiesser, 2016). Additionally, a wealth of research indicates that children are sensitive to ownership as a critical factor in determining an agent's rights and actions (e.g., Neary & Friedman, 2013; Petraszewski & Shaw, 2015). Thus, ownership per se— often cued via language (“This is yours”)—may distinctively boost children's evaluation of individual objects. Another relevant factor appears to be the child's emotional attachment to the object in question, given that preference for certain owned objects was stronger when attachment to such objects was stronger. Again, language may play a role here, given the finding that attachment objects nearly always received a proper name (in 30/31 instances), and at significantly higher rates than non-attachment objects. Importantly, however, effects of both ownership and emotional attachment were limited to two of the three object types under investigation: sleep and animate objects, but not inanimate objects.

We speculate that anthropomorphism of a toy—that is, treating a toy as if it were a person, by imbuing it with emotions, intentions, and motivations (Epley, Waytz, & Cacioppo, 2007)—may be a crucial additional ingredient that heightens children's preference for unique individuals. Certainly throughout development, actual people and animals are considered to be unique individuals, such that it would be unacceptable to accept a replacement for one's own mother, spouse, friend, or pet--no matter how much newer or more attractive such a replacement might be. Perhaps, then, attention to unique objects is heightened when objects are conceptualized as if they were animate. Children are more likely to anthropomorphize toys to which they are emotionally attached (Gjersoe, Hall, & Hood, 2015), and in our own data, children were more likely to provide a proper name for toys to which they are attached. However, features of an object (e.g., eyes, face, a soft or furry texture) are also likely to elicit anthropomorphism. Thus, ownership, attachment, and anthropomorphism may combine to yield the patterns obtained in this study: a preference for objects that are owned, to which the child is attached, and that have animate features, including faces (animate objects) or a soft or furry texture (sleep objects). Anthropomorphism is unlikely to fully account for all cases of attention to unique history (e.g., greater value of JFK's golf clubs), but it may be a crucial factor when reasoning about attachment objects, or one's own objects more generally.

Another factor that may shape children's concepts of unique objects are cultural practices and values. The rates at which children form attachments to objects varies across cultures; for example, mothers in a white, urban, U.S. sample report much higher rates of object attachment in their young children than do mothers in an urban Japanese sample (Hobara, 2003). It would be informative to test if preferences for original objects are less pronounced or even absent in cultures where attachment objects are less typical. Relatedly, multiple studies have found cultural variation in children's reasoning about ownership and owned objects (e.g., Kanngiesser, Rossano, & Tomasello, 2015; Rochat et al., 2014). These differences suggest a fruitful arena for addressing how cultural practices may influence children's object concepts and value.

Extending beyond the question of attachment per se, these data also have potentially broader implications for concepts of individuals versus kinds. Human conceptual systems honor a distinction between object kinds (e.g., dogs) and unique individuals (e.g., Fido) (Xu, 2007). This distinction is evident in formal distinctions in language (count nouns vs. proper nouns; Hall et al., 2004), judgments of identity (Hall, 1998; Karmiloff-Smith, 1981; Rips, Blok, & Newman, 2006), symbolic reasoning (Csibra & Shamsudheen, 2015), and inductive generalizations (Baldwin, Markman, & Melartin, 1993; Butler & Tomasello, 2016). At the same time, in numerous contexts, people gloss over individual differences and treat specific instances of a kind as interchangeable (e.g., one is unlikely to keep track of differences among individual Cheerios within a bowl of cereal, or individual pennies in a coin jar). A central task of development is to determine when it is important to exert the extra cognitive resources to track the individual identity of an item. The present line of research provides evidence on this broader question.

Finally, although typically kinds are thought to be collections of individuals, the present data suggest one way in which the relation does not fully hold. Specifically, the value of an attribute (e.g., “old”) can flip, depending on whether the focus is on the kind (blankets: new > old) or a unique individual (my blanket: old > new). Whereas signs of wear and age are desirable in one's own objects, they are negatively evaluated when judging unfamiliar objects. This phenomenon raises a more general question of what other features may shift depending on whether one is considering the kind vs. an individual member of that kind. The intriguing possibility exists that individuals do not just inherit attributes from the kinds to which they belong, but rather may be construed in terms of an altogether different assortment or weighting of features.

Figure 2.

Preference task, mean proportion of selections of the old object, as a function of Task (Child vs. Researcher Preference) and Item Type (Focal Pairs vs. Control Pairs). Error bars indicate SEs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NICHD grant HD-36043 to Gelman. We are grateful to the children and parents who participated in the research. We thank Bryana Bayly, Cara Brennan, Bridget Gallagher, Dhara Gosalia, Jaime Kobak, Lauren Leibach, Conrad Mahr, Ananya Mayukha, Merranda McLaughlin, Natasha Patel, Kary Richardson, Elena Ross, and Madeline Sowatsky for their research assistance.

Appendix – Toy Questionnaire

Does the child have a name for this object? (yes/no)

How much time does your child spend with this object during awake time? (hours/day)

How often does your child sleep with this object?

How often does your child carry this object to preschool/daycare/babysitter?

How often does your child carry this object when going on outings?

How strongly would your child object to this object being put away while at home?

How strongly would your child object to not being able to take this object with him/her when you go on outings?

How strong do you think your child's attachment is to this object?

Any other comments or observations:

Note: Questions 3-8 were on a 1-10 Likert Scale.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashby NJ, Dickert S, Glöckner A. Focusing on what you own: Biased information uptake due to ownership. Judgment and Decision Making. 2012;7(3):254–267. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DA, Markman EM, Melartin RL. Infants' ability to draw inferences about nonobvious object properties: Evidence from exploratory play. Child Development. 1993;64(3):711–728. doi: 10.2307/1131213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belk RW. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research. 1988;15(2):139–168. doi: 10.1086/209154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom P. Intention, history, and artifact concepts. Cognition. 1996;60(1):1–29. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)00699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom P. How pleasure works: The new science of why we like what we like. New York: Random House; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Butler LP, Tomasello M. Two-and 3-year-olds integrate linguistic and pedagogical cues in guiding inductive generalization and exploration. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2016;145:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csibra G, Shamsudheen R. Nonverbal generics: Human infants interpret objects as symbols of object kinds. Annual Review of Psychology. 2015;66:689–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deák GO, Ray SD, Brenneman K. Children's perseverative appearance-reality errors are related to emerging language skills. Child Development. 2003;74:944–964. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn DM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT™-4) Johannesburg: Pearson Education Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Epley N, Waytz A, Cacioppo JT. On seeing human: a three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review. 2007;114(4):864–886. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EM, Mull MS, Poling DA. The authentic object? A child's-eye view. In: Paris SG, editor. Perspectives on object-centered learning in museums. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier BN, Gelman SA. Developmental changes in judgments of authentic objects. Cognitive Development. 2009;24(3):284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier BN, Gelman SA, Wilson A, Hood BM. Picasso paintings, moon rocks, and hand-written Beatles lyrics: Adults' evaluations of authentic objects. Journal of Cognition and Culture. 2009;9(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman O, Vondervoort JW, Defeyter MA, Neary KR. First possession, history, and young children's ownership judgments. Child Development. 2013;84(5):1519–1525. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furby L, Wilke M. Some characteristics of infants' preferred toys. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1982;140(2):207–219. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1982.10534193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA. Artifacts and essentialism. Review of Philosophy and Psychology. 2013;4(3):449–463. doi: 10.1007/s13164-013-0142-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA, Frazier BN, Noles NS, Manczak EM, Stilwell SM. How much are Harry Potter's glasses worth? Children's monetary evaluation of authentic objects. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2015;16(1):97–117. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2013.815623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA, Manczak EM, Noles NS. The nonobvious basis of ownership: Preschool children trace the history and value of owned objects. Child Development. 2012;83(5):1732–1747. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA, Manczak EM, Was AM, Noles NS. Children seek historical traces of owned objects. Child Development. 2016;87(1):239–255. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjersoe NL, Hall EL, Hood B. Children attribute mental lives to toys when they are emotionally attached to them. Cognitive Development. 2015;34:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2014.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutheil G, Gelman SA, Klein E, Michos K, Kelaita K. Preschoolers' use of spatiotemporal history, appearance, and proper name in determining individual identity. Cognition. 2008;107(1):366–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DG. Continuity and the persistence of objects: When the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Cognitive Psychology. 1998;37(1):28–59. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1998.0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DG. Proper names in early word learning: Rethinking a theoretical account of lexical development. Mind & Language. 2009;24(4):404–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0017.2009.01368.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hampp C, Schwan S. The role of authentic objects in museums of the history of science and technology: Findings from a visitor study. International Journal of Science Education, Part B. 2015;5(2):161–181. doi: 10.1080/21548455.2013.875238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harbaugh WT, Krause K, Vesterlund L. Are adults better behaved than children? Age, experience, and the endowment effect. Economics Letters. 2001;70:175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Hobara M. Prevalence of transitional objects in young children in Tokyo and New York. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24(2):174–191. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hood BM, Bloom P. Children prefer certain individuals over perfect duplicates. Cognition. 2008;106(1):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood B, Weltzien S, Marsh L, Kanngiesser P. Picture yourself: Self-focus and the endowment effect in preschool children. Cognition. 2016;152:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanngiesser P, Rossano F, Tomasello M. Late emergence of the first possession heuristic: Evidence from a small-scale culture. Child Development. 2015;86(4):1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff-Smith A. A functional approach to child language: A study of determiners and reference. Vol. 24. Cambridge University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Legare CH, Wellman HM, Gelman SA. Evidence for an explanation advantage in naïve biological reasoning. Cognitive Psychology. 2009;58(2):177–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman EB, Arnold BE, Reeves SL. Attachments to blankets, teddy bears, and other nonsocial objects: A child's perspective. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1995;156(4):443–459. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan S, Pesowski ML, Friedman O. Identical but not interchangeable: Preschoolers view owned objects as non-fungible. Cognition. 2016;146:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll H, Meltzoff AN, Merzsch K, Tomasello M. Taking versus confronting visual perspectives in preschool children. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(4):646. doi: 10.1037/a0028633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morewedge CK, Giblin CE. Explanations of the endowment effect: an integrative review. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2015;19(6):339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nancekivell SE, Friedman O. Preschoolers selectively infer history when explaining outcomes: Evidence from explanations of ownership, liking, and use. Child Development. 2014;85(3):1236–1247. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nancekivell SE, Friedman O. “Because it's hers”: When preschoolers use ownership in their explanations. Cognitive Science. 2016 doi: 10.1111/cogs.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary KR, Friedman O. The origin of children's appreciation of ownership rights. In: Banaji M, Gelman SA, editors. Navigating the social world: What infants, children, and other species can teach us. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 356–360. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff C, Rozin P. The contagion concept in adult thinking in the United States: Transmission of germs and of interpersonal influence. Ethos. 1994;22(2):158–186. [Google Scholar]

- Newman GE. An essentialist account of authenticity. Journal of Cognition and Culture in press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman GE, Bloom P. Physical contact influences how much people pay at celebrity auctions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111(10):3705–3708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313637111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman GE, Diesendruck G, Bloom P. Celebrity contagion and the value of objects. Journal of Consumer Research. 2011;38(2):215–228. doi: 10.1086/658999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Passman RH, Halonen JS. A developmental survey of young children's attachments to inanimate objects. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1979;134(2):165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Pietraszewski D, Shaw A. Not by strength alone. Human Nature. 2015;26(1):44–72. doi: 10.1007/s12110-015-9220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S. The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. New York: Penguin; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Rothbart MK. Development of short and very short forms of the Children's Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2006;87(1):102–112. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8701_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repacholi BM, Gopnik A. Early reasoning about desires: evidence from 14- and 18-month-olds. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(1):12–21. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich AN, Bullot NJ. Keeping track: The tracking and identification of human agents. Topics in Cognitive Science. 2014;6(4):560–566. doi: 10.1111/tops.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rips LJ, Blok S, Newman G. Tracing the identity of objects. Psychological Review. 2006;113(1):1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat P. Possession and morality in early development. In: Ross H, Friedman O, Ross H, Friedman O, editors. Origins of ownership of property. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass; 2011. pp. 23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat P, Robbins E, Passos-Ferreira C, Oliva AD, Dias MD, Guo L. Ownership reasoning in children across cultures. Cognition. 2014;132(3):471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Muroff J, Lewin AB, Geller D, Ross A, McCarthy K, et al. Steketee G. Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of the Children's Saving Inventory. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2011;42(2):166–182. doi: 10.1007/s10578-010-0207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler R. Towards a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 1980;1:39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg P, Russell JE. Proximity and interactional behavior of young children to their “security” blankets. Child Development. 1971:1575–1579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott DW. Transitional objects and transitional phenomena—A study of the first not-me possession. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 1953;34:89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F. Sortal concepts, object individuation, and language. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11(9):400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Carey S. Infants' metaphysics: the case of numerical identity. Cognitive Psychology. 1996;30:111–153. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1996.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]