Abstract

The chemical 3-hydroxypropionate (3HP) is an important starting reagent for the commercial synthesis of specialty chemicals. In this study, a part of the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle from Metallosphaera sedula was utilized for 3HP production. To study the basic biochemistry of this pathway, an in vitro-reconstituted system was established using acetyl-CoA as the substrate for the kinetic analysis of this system. The results indicated that 3HP formation was sensitive to acetyl-CoA carboxylase and malonyl-CoA reductase, but not malonate semialdehyde reductase. Also, the competition between 3HP formation and fatty acid production was analyzed both in vitro and in vivo. This study has highlighted how metabolic flux is controlled by different catalytic components. We believe that this reconstituted system would be valuable for understanding 3HP biosynthesis pathway and for future engineering studies to enhance 3HP production.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10295-016-1793-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 3-Hydroxypropionate, 3-Hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle, Escherichia coli, Metallosphaera sedula, Metabolic engineering

Introduction

The chemical 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3HP) is an important building block and is ranked among the top third of the 12 platform chemicals selected by the US Department of Energy [42]. The bifunctionality of 3HP makes it a versatile platform chemical for numerous applications, including the production of acrylic acid, acryl amide, malonic acid, and 1,3-propanediol [10]. Also, 3HP is a useful starting material for cyclization and polymerization reactions to produce propiolactone, polyesters, poly(3-hydroxypropionate), and other oligomers [18, 22, 32]. Recently, there has been great interest in producing 3HP at an industrial scale from renewable sources, instead of via traditional chemical synthesis.

Several biosynthetic pathways involved in glycerol, glucose, or carbon dioxide metabolism have been proposed for 3HP production [7, 16, 24]. Although significant advances have been made in manipulating microorganisms to produce useful products from carbon dioxide and hydrogen, this strategy is challenging, and few successful trials have been reported. Until now, exploring non-photosynthetic routes for biological fixation of carbon dioxide into valuable industrial chemical precursors and fuels is moving from concept to reality [15]. Recently, an engineered Pyrococcus furiosus strain was shown to be able to use hydrogen gas and incorporate carbon dioxide into 3HP by exploiting microbial hyperthermophilicity [14, 19]. Also, the conversion of glycerol to 3HP via glycerol dehydratase and aldehyde dehydrogenase has been investigated extensively using recombinant Escherichia coli strains [34–36]. Through systematic engineering of the glycerol dehydrogenase GabD4 from Cupriavidus necator, industrial-scale yields of 3HP from glycerol have been achieved [8]. Additionally, the US-based agricultural company Cargill proposed seven important biochemical pathways for 3HP production from glucose via different intermediates, including lactate, glycerate, propionate, beta-alanine, and malonyl-CoA [31]. However, because the reaction is thermodynamically unfavorable, only a few strains have been constructed that can further process the intermediates lactate, glycerate, or propionate [22]. Recently, a synthetic pathway was engineered and optimized for the de novo biosynthesis of beta-alanine and its subsequent conversion into 3HP using a novel beta-alanine–pyruvate aminotransferase discovered in Bacillus cereus. This synthetic pathway was expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, enabling the production of 13.7 g/L 3HP [5].

Utilizing the component enzymes of the 3-hydroxypropionate or 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycles to reduce the common intracellular intermediate malonyl-CoA is another attractive route for biosynthetic 3HP production. The metabolite 3HP is a key intermediate in the 3-hydroxypropionate and 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycles, which are two of the six pathways responsible for autotrophic carbon dioxide fixation [11, 37]. The 3-hydroxypropionate cycle was first observed in the thermophilic, phototrophic eubacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus, which secretes 3HP during phototrophic growth [17]. In this cycle, carbon dioxide is fixed by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Acc) and propionyl-CoA carboxylase. The newly formed malonyl-CoA metabolite is reduced to 3HP via a bifunctional enzyme, with both alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase activities [12]. In 2007, a fifth autotrophic fixation pathway for carbon dioxide, the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle, was discovered in Metallosphaera sedula [4]. In M. sedula, malonyl-CoA is reduced to 3HP via two separate enzymes, namely malonyl/succinyl-CoA reductase (Mcr) and malonate semialdehyde reductase (Msr). Utilizing the malonyl-CoA pathway to produce 3HP is expected to have some advantages. For example, this pathway is easy to implement, as only one or two enzymatic steps are used to reduce the malonyl-CoA intermediate. Additionally, various C5 and C6 sugars derived from lignocellulosic biomass can be used as raw materials for 3HP production, as acetyl-CoA is a common intermediate in sugar metabolism. Furthermore, a high recovery of carbon resource is expected from glucose-based pathway, because the carbon dioxide released during glycolysis is reabsorbed in the acetyl-CoA carboxylase-mediated reaction.

In metabolic engineering, discovering and targeting kinetic bottlenecks and stoichiometric inefficiencies are very important. However, the methods used to accomplish these goals are sometimes labor-intensive combinations of molecular cloning and high-throughput screening. To simplify this process, a cell-free system was developed. This system has been applied to transient or steady-state analysis and manipulation of substrates, cofactors, allosteric regulators, and enzyme levels in fatty acid biosynthesis, and these analyses could be completed over a span of a few hours [30]. Subsequently, an escalated in vitro-reconstituted system was developed for the precise analysis of different elements related to fatty acid synthesis [43, 48]. This in vitro-reconstituted system could provide data on critical parameters easily and rapidly, thereby becoming an ideal approach for identifying the rate-limiting step of an optimized system and for understanding any biosynthetic pathway at the biochemical level. This strategy was also extended to cyanobacteria for the overproduction of fatty acids [23] and to E. coli for the overproduction of alkenes and alkanes through the iterative polyketide pathway [29].

In this study, a part of the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle from M. sedula was utilized for 3HP production which allowed for adjusting the ratio between MCR and MSR to obtain the best catalyzing results (Fig. 1). An in vitro-reconstituted system for 3HP biosynthesis was established to assess this pathway for a better understanding of this system. We also analyzed the competition between 3HP formation and fatty acid production based on this in vitro-reconstituted system. Finally, we blocked fatty acid synthesis in vivo to enhance 3HP production.

Fig. 1.

3-Hydroxypropionate (3HP) biosynthesis pathway from glucose through malonyl-CoA. a The in vivo 3HP biosynthesis pathway. b The in vitro reconstitution assay. Acc acetyl-CoA carboxylase, Mcr malonyl-CoA reductase from Metallosphaera sedula; Msr malonate semialdehyde reductase, Fas fatty acid synthetase, TesA thioesterases

Materials and methods

Materials

DNA polymerase and restriction endonucleases were purchased from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). T4 DNA ligase was purchased from Fermentas (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kits, QIAquick PCR Purification Kits, and gel-extraction kits were obtained from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). The 3HP standard was purchased from TCI, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). All other reagents used in the in vitro experiments were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. [1-14C]acetyl-CoA (55 mCi/mmol) was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Genomic DNA of M. sedula strain DSM 5348 was purchased from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany).

Plasmid construction

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1, and the sequences of all oligonucleotides are shown in Table 2. The gene Msed_0709 (GenBank gene ID: 5103747), which encodes Mcr, was codon-optimized (GenBank accession number: KT962989) and synthesized by GENEWIZ Corp (Suzhou, China). Then, Msed_0709 was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the forward primer NdeI-Mcr-F and reverse primer EcoRI-SpeI-Mcr-R. Msed_1993 (GenBank gene ID: 5103380), which encodes Msr, was amplified from M. sedula genomic DNA [3] using the forward primer NdeI-Msr-F and reverse primer HindIII-Msr-R. The NdeI/EcoRI-digested mcr gene was inserted into the pET28 vector (Novagen) to generate plasmid pZL37, which was then used to overexpress the Mcr protein as an N-terminal 6 × His-tagged fusion protein. The NdeI/HindIII-digested msr gene was inserted into pET28 to generate plasmid pYW4, which was then used to overexpress the Msr protein as an N-terminal 6 × His-tagged fusion protein. Then, the XbaI/HindIII-digested msr gene from pYW4 was subcloned into SpeI/HindIII-digested pZL37, yielding the plasmid pZL38, which was then used to overexpress both the Mcr and Msr proteins simultaneously. The pBR322 origin of replication in pET21a was replaced with the p15A origin using the following method. The pET21a backbone fragment was amplified using the forward primer pET21a-F and reverse primer pET21a-R, while the p15A origin-of-replication fragment was amplified using the forward primer p15A-F and reverse primer p15A-R. Subsequently, these two fragments were assembled using a simple cloning method described previously [47] to yield plasmid pXL010. The ketoacyl-ACP synthase gene fabF (GenBank gene ID: 946665) was amplified using the forward primer BamHI-FabF-F and reverse primer XhoI-FabF-R from E. coli genomic DNA. The ketoacyl-ACP synthase gene fabH (GenBank gene ID: 946003) was amplified using the forward primer NdeI-FabH-F and reverse primer BamHI-FabH-R from E. coli genomic DNA. Then, the BamHI/XhoI-digested fabF gene and the NdeI/BamHI-digested fabH gene were separately inserted into pXL010 to yield plasmids pXL035 and pXL036. The detailed construction diagram is listed in Fig. S1.

Table 1.

Plasmids and strains used in this study

| Name | Genotype/properties | Resource |

|---|---|---|

| pET28a(+) | pBR322 origin, KanR, PT7 | Novagen |

| pXL010 | pET21a(+); replace the pBR322 origin with p15A origin | This study |

| pZL37 | pET28a; PT7: N-terminal his6-tag mcr | This study |

| pYW4 | pET28a; PT7: N-terminal his6-tag msr | This study |

| pZL38 | pET28a; PT7: mcr–msr | This study |

| pXL035 | PXL010; PT7: fabF | This study |

| pXL036 | PXL010; PT7: fabH | This study |

| BL21 (DE3) | E. coli B dcm ompT hsdS(r −B m −B) gal | Invitrogen |

| MG1655 (DE3) | E. coli F − λ − ilvG rfb-50 rph-1 | Invitrogen |

| XL011 | MG1655 (DE3) derivative; {pZL38: PT7-mcr-msr} | This study |

| XL030 | MG1655 (DE3) derivative; {pZL38: PT7-mcr-msr; pXL035: PT7-fabF} | This study |

| XL031 | MG1655 (DE3) derivative; {pZL38: PT7-mcr-msr; pXL035: PT7-fabH} | This study |

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|

| NdeI-Mcr-F | GGACATATGCGCCGTACCCTGAA |

| EcoRI-SpeI-Mcr-R | CTTGAATTCACTAGTTTAGCGTTTATCAATATAGC |

| EcoRI-SpeI-F | CGCCATATGACTGAAAAGGTATCTGT |

| HindIII-Msr-R | CCCAAGCTTTTATTTTTCCCAAACTAGTT |

| pET21a-F | ATCTTCCAGGAAATCTCCGCCCCGGATATCAACGCCAGCAACGCGGCCTTTT |

| pET21a-R | TCATCTTATTAATCAGATAAAATATTTGATATCGAAGATCCTTTGATCTTTTCTACGG |

| p15A ori-F | CCGTAGAAAAGATCAAAGGATCTTCGATATCAAATATTTTATCTGATTAATAAGATGA |

| p15A ori-R | AAAAGGCCGCGTTGCTGGCGTTGATATCCGGGGCGGAGATTTCCTGGAAGAT |

| BamHI-FabF-F | TATACGGATCCATGTCTAAGCGTCGTGTAGTTG |

| XhoI-FabF-R | CGAGCCTCGAGTTAGATCTTTTTAAAGATCAAAGAAC |

| NdeI-FabH-F | GACGACATATGTATACGAAGATTATTGGTACTG |

| BamHI-FabH-R | ATATAGGATCCCTAGAAACGAACCAGCGCGG |

aFor plasmid construction via restriction enzyme digestion and ligation, complementary sequences were designed using the Primer Premier 5 software, and suitable restriction sites and protective bases were introduced; for plasmid construction via the simple cloning method, complementary sequences were designed using the Primer Premier 5 software, flanked by the homologous sequence. The restriction sites and homologous sequence used for cloning are underlined

Strains and media

The strains constructed and used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli MG1655 (DE3) was used as the background strain for 3HP production. E. coli XL1-Blue was used to propagate the recombinant plasmids.

Escherichia coli transformants were selected in LB medium (5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L tryptone, and 10 g/L NaCl) with the appropriate antibiotics (50 μg/mL kanamycin and/or 100 μg/mL ampicillin). Modified M9 medium was used for shake-flask cultivations and was prepared (per liter) with 6 g-Na2HPO4, 3-g KH2PO4, 0.5-g NaCl, 1-g NH4Cl, 1-mM MgSO4, 10-mg vitamin B1, 0.1-mM CaCl2, 5-g yeast extract, 20 g glucose, and 1 mL of 1000 × Trace Metal Mix (27-g FeCl3·6H2O, 2-g ZnCl2·4H2O, 2-g CaCl2·2H2O, 2-g Na2MoO4·2H2O, 1.9-g CuSO4·5H2O, 0.5-g H3BO3, and 100-mL HCl per liter water), as described previously [2]. The initial pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 5 M NaOH.

Protein purification

To purify the Mcr and Msr proteins, E. coli BL21 (DE3) was transformed with plasmids pZL37 and pYW4. The transformed cells were grown in LB media containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C until the OD600 reached approximately 0.6. Then, the cells were allowed to cool to 18 °C and induced with 0.1-mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16–18 h at 18 °C. The cells were centrifuged (6000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C), resuspended in 35 mL of Buffer A (50 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.0), and lysed by sonication. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation (19,000 rpm, 60 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was loaded into a 5-mL gravity flow column, and the proteins were sequentially eluted with 20 mL of Buffer A (50 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.0) supplemented with 50, 150, 300, and 500 mM imidazole. Purified proteins were buffer-exchanged with storage buffer (100 mM phosphate, 10 % glycerol, pH 7.6) and concentrated by centrifugation using an Amicon® Ultra-4 filter (10 kDa, GE Healthcare). Freshly purified proteins were frozen and stored at −80 °C. The four proteins (AccA/B/C/D) expressed in E. coli cells were purified as described previously [26]. The ten individual proteins of E. coli fatty acid synthetase (Fas) were purified as described previously [48]. Protein concentrations were measured with a Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) to generate a standard curve.

In vitro reconstitution of the 3HP-synthesis system

In vitro assays with the reconstituted system were performed as described previously [29, 48]. Briefly, the reactions were performed in 50-mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) in a volume of 140 μL, with 5-mM NADPH, 1-mM TCEP, 5-mM ATP, 10-mM NaHCO3, 10-mM MgCl2, 1-mM acetyl-CoA (with 5 % [1-14C] acetyl-CoA), 3 or 10 μM each of AccA/B/C/D, and increasing concentrations of Mcr and/or Msr for the titration assays. At various intervals, 20 μL of the reaction mixture was withdrawn and quenched with 180 μL of an 80:80:20 (v/v) solution of methanol:isopropanol:acetic acid. The samples were dried and resuspended in 30 μL of methanol, and then spotted on a silica-gel thin-later chromatography plate. Finally, the samples were chromatographed using a solvent system comprised of a 70:40:2 (v/v) mixture of chloroform:methanol:acetic acid. Radioactivity was quantified on a Packard Phosphor imager (GE Healthcare), using [1-14C]acetyl-CoA as the calibration standard.

For competitive radioassays between 3HP and fatty acid production, the reaction mixtures included 3 or 10 μM each of AccA/B/C/D, 0.2 or 1 μM Mcr, 1 μM Msr, 1 μM each of FabA/B/D/F/G/H/I/Z, 10 μM holo-ACP, 10 μM TesA, and/or 200 μM cerulenin. To separate the products (3HP and fatty acid), the samples were first chromatographed using a mobile phase comprised of a 50:60:2 (v/v) mixture of hexane:diethylether:acetic acid, followed by a second mobile phase comprised of a 70:40:2 (v/v) mixture of chloroform:methanol:acetic acid.

Flask fermentation procedure

The E. coli strain was cultivated in modified M9 minimal media (described above) for flask fermentation. Single colonies were inoculated in 5 mL of LB media and cultured overnight at 37 °C. Then, 1 mL of seed culture was added to 100 mL of M9 media containing the appropriate antibiotics (50 μg/mL kanamycin and/or 100 μg/mL ampicillin) in a 500-mL flask and grown at 37 °C and 220 rpm. IPTG (0.1 mM) was added when the OD600 reached 0.7. Cerulenin (10 mg/L) was added at 4 h after induction. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Analysis of 3HP production by HPLC

The 3HP concentration was analyzed using a previously described method [5]. The sample was separated using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 HPLC system (Thermo Scientific, USA) and analyzed for 35 min using an Aminex HPX-87H ion-exclusion column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) with a mobile phase of 5-mM H2SO4 and a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The temperature of the column was maintained at 50 °C. The refractive index at 45 °C and the UV absorption (RS Variable Wavelength Detector, UltiMate 3000, Thermo Scientific, USA) at 210 nm were measured. The concentrations of 3HP were detected using a refractive index detector (Shodex RI-101, Japan) and were verified by measuring their UV spectra in comparison with the spectrum of the 3HP standard.

Results

Effects of Mcr and Msr concentrations on the 3HP-synthesis rate

The metabolite 3HP was previously described as a key intermediate of the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle [4]. However, this separated system from M. sedula has not been investigated to produce 3HP. To obtain detailed biochemical information regarding the capacity of this cycle for 3HP biosynthesis, we generated an in vitro-reconstituted system. Six individual proteins, namely, AccA/B/C/D, Mcr, and Msr, were purified to assemble the 3HP synthetic pathway in vitro. [1-14C]acetyl-CoA was used as the substrate.

To examine the effects of the Mcr and Msr protein concentrations on the steady-state activity of this reconstituted system, the concentration of Acc was fixed at 10 μM. We first investigated the effect of the 3HP-biosynthesis rate on the concentration of Msr, using a fixed Mcr concentration of 1 μM. The results showed that the level of 3HP increased only slightly when the concentration of Msr was increased from 0.2 to 15 μM (Fig. 2a). We further investigated the dependence of Mcr on 3HP biosynthesis when the concentration of Msr was fixed at 1 μM. The results showed that Mcr had a marked effect when the concentration was varied from 0.2 to 3 μM, resulting in a 4.2-fold increase in the rate of 3HP formation. Mcr concentrations ranging from 3 to 15 μM did not appreciably influence the rate of 3HP synthesis (Fig. 2b). Also, similar results were observed when the Acc concentration was reduced to 3 μM (Fig. 2a, b). These data showed that the reaction catalyzed by Mcr, rather than that catalyzed by Msr, is the critical limiting step in the 3HP biosynthesis pathway.

Fig. 2.

In vitro reconstitution of 3HP production from acetyl-CoA. a Titration of Msr; the assay mixture included 1-μM Mcr and 10-μM Acc (blue) or 3-μM Acc (red). b Titration of Mcr; the assay mixture included 1-μM Msr and 10-μM Acc (blue) or 3-μM Acc (red). c Titration of Acc; the assay mixture included 5-μM Mcr and 1-μM Msr. d Competitive radioassay between 3HP and fatty acid production. Each assay mixture included 1 μM of each Fab, 10-μM holo-Acp, 10-μM TesA, 1-μM Msr, 10-μM Acc (blue) or 3-μM Acc (red), and (1) 0.2-μM Mcr or (2) 1-μM Mcr or (3) 1-μM Mcr, and 200-μM cerulenin. Solid circle, 3HP; Solid triangle, fatty acid

Effects of Acc concentration on the 3HP synthesis rate

Conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA by Acc is the initial step in 3HP biosynthesis (Fig. 1). Many researchers have overexpressed this enzyme to increase the production level of downstream products [9, 30, 38, 41]. Therefore, we employed this enzyme in our in vitro-reconstituted system to evaluate the contribution of Acc to 3HP biosynthesis. To prevent limitations caused by downstream proteins, the concentration of Mcr was fixed at 5 μM, while that of Msr was fixed at 1 μM. Acc supplementation increased the 3HP synthesis rate at concentrations below 10 μM, while the 3HP synthesis rate was reduced at Acc concentrations exceeding 10 μM (Fig. 2c). This phenomenon indicated that, although the production of 3HP was dependent on the concentration of Acc, excessive Acc would inhibit 3HP formation.

Analysis of the competition between 3HP and fatty acid synthesis

Acetyl-CoA is a critical intermediate metabolite in the metabolic network of the cell. Acetyl-CoA is the substrate for the tri-carboxylic acid cycle and a precursor metabolite for amino acid, nucleotide base, and porphyrin synthesis, as well as the substrate for protein acetylation [21]. However, when malonyl-CoA is formed through the condensation of bicarbonate with acetyl-CoA, the product primarily flows into fatty acid synthesis [39]. Thus, fatty acid biosynthesis is the main competitive pathway for exogenously introduced 3HP formation, with malonyl-CoA as the substrate (Fig. 1). In the in vitro titration assays, reconstitution of the fatty acid synthase was performed as described previously [48]. The concentrations of FabA/B/D/F/G/H/I/Z were 1 μM each, and those of holo-ACP and TesA were 10 μM [48].

Here, we first introduced the fatty acid biosynthesis system into the 3HP-formation system and analyzed the competitive relation between 3HP and the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway in vitro. When 0.2-μM Mcr and 1-μM Msr were titrated with the fatty acid synthesis system, an 8.9-fold higher initial consumption rate for fatty acids versus 3HP was observed (Fig. 2d). When 1-μM Mcr and 1-μM Msr were titrated with the fatty acid synthesis system, the ratio was reduced to 1.8 (Fig. 2d). This result indicated that when the Mcr concentration was low, the fatty acid pathway was the main competitive pathway, and when Mcr concentration increased to an equal amount with Msr, the ability of 3HP production was comparable to fatty acid biosynthesis. Also, 200-μM cerulenin, a specific inhibitor of the fabB–fabF gene products [27], was added to block the production of fatty acids. In this experiment, no fatty acids were produced, and the rate of 3HP production increased marginally (Fig. 2d).

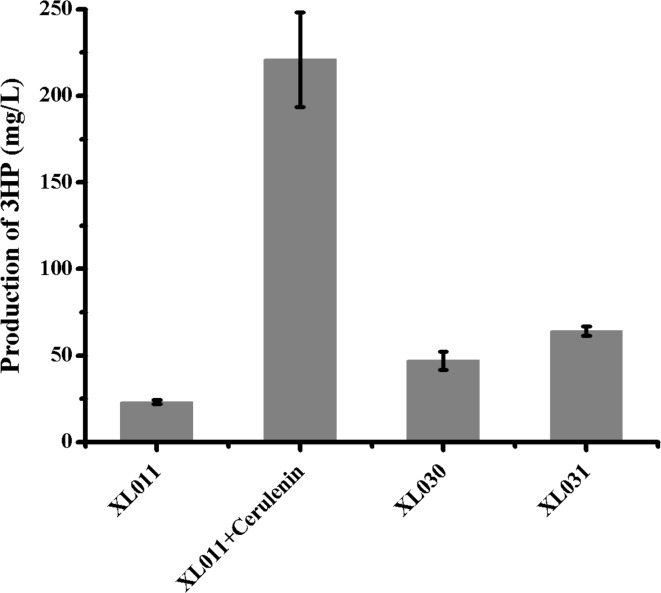

To investigate the effect of repression of fatty acid synthases on 3HP biosynthesis in vivo, the production of 3HP was evaluated by repressing FabB and FabF activities using 10 mg/L cerulenin. The 3HP production was identified by NMR (Fig. S2) and quantified via HPLC (Fig. S3). The amount of 3HP produced was approximately 221 mg/L, which is 10-fold that produced by strain XL011 without cerulenin addition (Fig. 3). However, the addition of cerulenin is cost-prohibitive for an industrial scale fermentation process. Therefore, an alternative metabolic engineering strategy was attempted. Previous studies have shown that increasing the amount of FabF or FabH could significantly inhibit the production of fatty acids [48]. When fabF was overexpressed, strain XL030 produced 47.0 mg/L 3HP, while a fabH-overexpressing strain XL031 produced 64.2 mg/L 3HP (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Production of 3HP by blocking fatty acid biosynthesis

Discussion

In this study, we reconstituted an in vitro synthetic pathway for 3HP production from three purified components using acetyl-CoA as the substrate. Our results indicate that 3HP synthesis is sensitive to Acc and Mcr, but not to Msr. It was reported that the Km value and specific activity of Mcr equaled 100 μM and 4.6 μM min−1 mg−1, respectively [1], while the Km value and specific activity of Msr equaled 70 ± 10 μM and 200 μM min−1 mg−1, respectively [20]. Although lacking the biochemistry parameter of Acc, it has been shown to have a limited specific activity in E. coli cell-free extract [9, 30]. All these data are consistent with the results of our in vitro reconstitution experiment. This finding has provided key clues for conducting targeted engineering of 3HP production in future studies. For example, our results suggest that more attention should be paid to the expression levels of Acc and Mcr. Also, we extended the application of the in vitro-reconstituted system to analyze the competition between 3HP formation and fatty acid synthesis. The results revealed that when the Mcr concentration in the system is low, more carbon flows into the fatty acid synthesis system than into the 3HP synthesis pathway. However, when the amount of Mcr is equal to the molar ratio of fatty acid synthase, the 3HP formation rate is similar to that of fatty acid synthesis. This result also implied that the cells were as capable of synthesizing 3HP as they were of synthesizing fatty acids.

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase is a widely used target in different organisms to overproduce various downstream products for metabolic engineering [9, 30, 38, 41]. However, altering the rate-limiting step to improve production is not simply a matter of “the more the better.” The balance of protein expression levels is also essential. It was reported that the expression of the ACA module by low-copy-number plasmids led to higher fatty acid production than with expression via high-copy-number plasmids [44]. In our in vitro titration assays, we found that supplementation of Acc increased the initial rate of 3HP synthesis only within an appropriate range, beyond which 3HP synthesis was inhibited. So, the expression level of Acc should be precisely regulated. In fact, fine-tuning the expression of Acc can be achieved via altering the promoters. Also, development of malonyl-CoA-responsive sensors that control Acc expression levels based on intracellular malonyl-CoA concentrations [28, 45] may hold great promise in overcoming critical limitations of Acc and optimizing 3HP titers and yields.

Blocking fatty acid biosynthesis has been applied previously to increase the production of resveratrol or plant flavonoid polyphenols [25, 27]. In this study, we found that carbon was mainly fluxed into the fatty acid biosynthetic pathway when a low concentration of Mcr was titrated into the fatty acid system. However, the highest 3HP-production rate was achieved only when cerulenin was added. Overexpression of fabF or fabH yielded only modest improvement. Recently, antisense RNA methods with high interference efficiencies of up to 80 % were developed to enhance the rate of biosynthesis of natural products [46]. Additionally, an RNA-based method, CRISPRi (clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats interference), that can efficiently silence a target gene with up to 99.9 % repression in E. coli has been developed recently [33]. Application of antisense RNA or CRISPRi technology may represent a better metabolic engineering strategy for increasing 3HP production by blocking fatty acid biosynthesis.

In this work, critical information regarding 3HP formation from acetyl-CoA was obtained using an in vitro-reconstituted system. The competition analysis between fatty acid biosynthesis and 3HP formation indicated that the potential of 3HP production was comparable to that of fatty acid biosynthesis. This study highlights the utility of the in vitro-reconstituted system. More efforts need to be directed at enhancing 3HP production in future work through in vivo metabolic engineering. Some feasible and effective strategies have been exploited in engineering the 3HP pathway in previous studies. Deletion of acetyl-CoA synthetase I and acetyl-CoA synthetase II, which competes with the heterologous pathway for acetyl-CoA, markedly improved 3HP production [40]. The 3HP level was also enhanced in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae by increasing the availability of the precursor malonyl-CoA and by coupling the production with increased NADPH supply [6]. Besides, combining different metabolic pathways to enhance 3HP production is an attractive strategy. A recombinant E. coli has been successfully constructed harboring a 3HP-synthetic pathway that transfers glucose to 3HP via a glycerol intermediate [32]. Engineering 4HB to acetyl-CoA [13] and its subsequent conversion to 3HP might also represent an effective production strategy. Also, exploiting the hyperthermophilicity of M. sedula to enhance 3HP production is attractive, and this strategy has been established successfully in P. furiosus [19]. These targeted metabolic engineering strategies have demonstrated enhanced 3HP production and have paved the way for future work. In conclusion, combination of the in vitro assay with an in vivo metabolic engineering strategy would further improve 3HP formation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Authors’ contributions

LT, LX, and YZ designed the study, performed the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. LX and YZ performed the experiments and edited the manuscript. CY, LZ, TG, ZF, and FS performed some experiments. DZ participated in the coordination and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 3HP

3-Hydroxypropionate

- Acc

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- Mcr

Malonyl-CoA reductase

- Msr

Malonate semialdehyde reductase

- Fas

Fatty acid synthetase

- TesA

Thioesterase

- FabF

Ketoacyl-ACP synthase

- FabH

Ketoacyl-ACP synthase

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Grant information

This research was supported by grants from the 863 and 973 Projects from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012AA02A701, 2011CBA00800, 2012CB721000) awarded to Tiangang Liu, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31222002, 31170096) awarded to Tiangang Liu.

Footnotes

Ziling Ye and Xiaowei Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Alber B, Olinger M, Rieder A, Kockelkorn D, Jobst B, Hugler M, Fuchs G. Malonyl-coenzyme A reductase in the modified 3-hydroxypropionate cycle for autotrophic carbon fixation in archaeal Metallosphaera and Sulfolobus spp. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8551–8559. doi: 10.1128/JB.00987-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atsumi S, Cann AF, Connor MR, Shen CR, Smith KM, Brynildsen MP, Chou KJ, Hanai T, Liao JC. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for 1-butanol production. Metab Eng. 2008;10:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auernik KS, Maezato Y, Blum PH, Kelly RM. The genome sequence of the metal-mobilizing, extremely thermoacidophilic archaeon Metallosphaera sedula provides insights into bioleaching-associated metabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:682–692. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02019-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg IA, Kockelkorn D, Buckel W, Fuchs G. A 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon dioxide assimilation pathway in Archaea. Science. 2007;318:1782–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1149976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borodina I, Kildegaard KR, Jensen NB, Blicher TH, Maury J, Sherstyk S, Schneider K, Lamosa P, Herrgård MJ, Rosenstand I. Establishing a synthetic pathway for high-level production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via β-alanine. Metab Eng. 2015;27:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Bao J, Kim I-K, Siewers V, Nielsen J. Coupled incremental precursor and co-factor supply improves 3-hydroxypropionic acid production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng. 2014;22:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Nielsen J. Advances in metabolic pathway and strain engineering paving the way for sustainable production of chemical building blocks. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu HS, Kim YS, Lee CM, Lee JH, Jung WS, Ahn JH, Song SH, Choi IS, Cho KM. Metabolic engineering of 3-hydroxypropionic acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:356–364. doi: 10.1002/bit.25444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis MS, Solbiati J, Cronan JE., Jr Overproduction of acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity increases the rate of fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28593–28598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Della Pina C, Falletta E, Rossi M. A green approach to chemical building blocks. The case of 3-hydroxypropanoic acid. Green Chem. 2011;13:1624–1632. doi: 10.1039/c1gc15052a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs G. Alternative pathways of carbon dioxide fixation: insights into the early evolution of life? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:631–658. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hügler M, Menendez C, Schägger H, Fuchs G. Malonyl-coenzyme A reductase from Chloroflexus aurantiacus, a key enzyme of the 3-hydroxypropionate cycle for autotrophic CO2 fixation. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2404–2410. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.9.2404-2410.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkins AB, Adams MW, Kelly RM. Conversion of 4-hydroxybutyrate to acetyl coenzyme A and its anapleurosis in the Metallosphaera sedula 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate carbon fixation pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:2536–2545. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04146-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkins AB, Lian H, Zeldes BM, Loder AJ, Lipscomb GL, Schut GJ, Keller MW, Adams MW, Kelly RM. Bioprocessing analysis of Pyrococcus furiosus strains engineered for CO2-based 3-hydroxypropionate production. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:1533–1543. doi: 10.1002/bit.25584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkins AS, McTernan PM, Lian H, Kelly RM, Adams MW. Biological conversion of carbon dioxide and hydrogen into liquid fuels and industrial chemicals. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry CS, Broadbelt LJ, Hatzimanikatis V. Discovery and analysis of novel metabolic pathways for the biosynthesis of industrial chemicals: 3-hydroxypropanoate. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106:462–473. doi: 10.1002/bit.22673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holo H. Chloroflexus aurantiacus secretes 3-hydroxypropionate, a possible intermediate in the assimilation of CO2 and acetate. Arch Microbiol. 1989;151:252–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00413138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang X, Meng X, Xian M. Biosynthetic pathways for 3-hydroxypropionic acid production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;82:995–1003. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1898-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller MW, Schut GJ, Lipscomb GL, Menon AL, Iwuchukwu IJ, Leuko TT, Thorgersen MP, Nixon WJ, Hawkins AS, Kelly RM. Exploiting microbial hyperthermophilicity to produce an industrial chemical, using hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5840–5845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222607110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kockelkorn D, Fuchs G. Malonic semialdehyde reductase, succinic semialdehyde reductase, and succinyl-coenzyme A reductase from Metallosphaera sedula: enzymes of the autotrophic 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle in Sulfolobales. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6352–6362. doi: 10.1128/JB.00794-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krivoruchko A, Zhang Y, Siewers V, Chen Y, Nielsen J. Microbial acetyl-CoA metabolism and metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2015;28:28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar V, Ashok S, Park S. Recent advances in biological production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:945–961. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo J, Khosla C. The initiation ketosynthase (FabH) is the sole rate-limiting enzyme of the fatty acid synthase of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Metab Eng. 2014;22:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwak S, Park Y-C, Seo J-H. Biosynthesis of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from glycerol in recombinant Escherichia coli expressing Lactobacillus brevisdhaB and dhaR gene clusters and E. coli K-12 aldH. Bioresour Technol. 2013;135:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard E, Yan Y, Fowler ZL, Li Z, Lim C-G, Lim K-H, Koffas MA. Strain improvement of recombinant Escherichia coli for efficient production of plant flavonoids. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:257–265. doi: 10.1021/mp7001472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Guo D, Cheng Y, Zhu F, Deng Z, Liu T. Overproduction of fatty acids in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111:1841–1852. doi: 10.1002/bit.25239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim CG, Fowler ZL, Hueller T, Schaffer S, Koffas MA. High-yield resveratrol production in engineered Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:3451–3460. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02186-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu D, Xiao Y, Evans BS, Zhang F. Negative feedback regulation of fatty acid production based on a malonyl-CoA sensor–actuator. Acs Synth Biol. 2014;4:132–140. doi: 10.1021/sb400158w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Q, Wu K, Cheng Y, Lu L, Xiao E, Zhang Y, Deng Z, Liu T. Engineering an iterative polyketide pathway in Escherichia coli results in single-form alkene and alkane overproduction. Metab Eng. 2015;28:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu T, Vora H, Khosla C. Quantitative analysis and engineering of fatty acid biosynthesis in E. coli. Metab Eng. 2010;12:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsakas L, Topakas E, Christakopoulos P. New trends in microbial production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid. Curr Biochem Eng. 2014;1:141–154. doi: 10.2174/2212711901666140415200133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng D-C, Wang Y, Wu L-P, Shen R, Chen J-C, Wu Q, Chen G-Q. Production of poly (3-hydroxypropionate) and poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxypropionate) from glucose by engineering Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2015;29:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Doudna JA, Weissman JS, Arkin AP, Lim WA. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raj SM, Rathnasingh C, Jo J-E, Park S. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from glycerol by a novel recombinant Escherichia coli BL21 strain. Process Biochem. 2008;43:1440–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2008.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raj SM, Rathnasingh C, Jung W-C, Park S. Effect of process parameters on 3-hydroxypropionic acid production from glycerol using a recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;84:649–657. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1986-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rathnasingh C, Raj SM, Jo JE, Park S. Development and evaluation of efficient recombinant Escherichia coli strains for the production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from glycerol. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;104:729–739. doi: 10.1002/bit.22429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saini R, Kapoor R, Kumar R, Siddiqi T, Kumar A. CO2 utilizing microbes—a comprehensive review. Biotechnol Adv. 2011;29:949–960. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tai M, Stephanopoulos G. Engineering the push and pull of lipid biosynthesis in oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for biofuel production. Metab Eng. 2013;15:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takamura Y, Nomura G. Changes in the intracellular concentration of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA in relation to the carbon and energy metabolism of Escherichia coli K12. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2249–2253. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-8-2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorgersen MP, Lipscomb GL, Schut GJ, Kelly RM, Adams MW. Deletion of acetyl-CoA synthetases I and II increases production of 3-hydroxypropionate by the metabolically-engineered hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus. Metab Eng. 2014;22:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wattanachaisaereekul S, Lantz AE, Nielsen ML, Nielsen J. Production of the polyketide 6-MSA in yeast engineered for increased malonyl-CoA supply. Metab Eng. 2008;10:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Werpy T, Petersen G. Top value added chemicals from biomass. Washington: US Department of Energy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao X, Yu X, Khosla C. Metabolic flux between unsaturated and saturated fatty acids is controlled by the FabA: FabB ratio in the fully reconstituted fatty acid biosynthetic pathway of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2013;52:8304–8312. doi: 10.1021/bi401116n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu P, Gu Q, Wang W, Wong L, Bower AG, Collins CH, Koffas MA. Modular optimization of multi-gene pathways for fatty acids production in E. coli. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1409. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu P, Wang W, Li L, Bhan N, Zhang F, Koffas MA. Design and kinetic analysis of a hybrid promoter–regulator system for malonyl-CoA sensing in Escherichia coli. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;9:451–458. doi: 10.1021/cb400623m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y, Lin Y, Li L, Linhardt RJ, Yan Y. Regulating malonyl-CoA metabolism via synthetic antisense RNAs for enhanced biosynthesis of natural products. Metab Eng. 2015;29:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.You C, Zhang X-Z, Zhang Y-HP. Simple cloning via direct transformation of PCR product (DNA multimer) to Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:1593–1595. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07105-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu X, Liu T, Zhu F, Khosla C. In vitro reconstitution and steady-state analysis of the fatty acid synthase from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci Usa. 2011;108:18643–18648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110852108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.