Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to examine current hookah users’ perceptions, attitudes, and normative beliefs regarding hookah smoking to further elucidate the rise in hookah smoking prevalence among young adults (aged 18–24 years) and reveal why hookah smoking is perceived as less harmful than other forms of tobacco consumption.

Study Design

Qualitative.

Methods

Data analysis of six focus group interviews with hookah smokers between 18–24 years was analyzed using a grounded theory approach. Focus groups were evenly split between frequent and infrequent hookah users, and were predominantly composed of college students, with two groups of hookah users consisting of 18–24 year olds of non-student status.

Results

Hookah users shared a much larger set of positive hookah smoking behavioral beliefs as opposed to negative behavioral beliefs. Generational traits served as the overarching commonality among the behavior performance initiation determinants observed. The most notable generational trends observed were within the cultural category, which included the following millennial characteristics: autonomy, personalization, novelty appeal, convenience, globally oriented, entertainment, collaboration, health conscious, and valuing their social network.

Conclusions

Millennial hookah users revealed mindfulness regarding both potential negative and positive reasons stemming from continued hookah use; however, behavioral beliefs were primarily fixated on the perception that hookah smoking was a healthier alternative to cigarette smoking. Future implications for this study’s findings include generating more positive ways to express these traits for young adults; policy implications include raising hookah bar age limits, implementing indoor smoking restrictions, and limiting the ease of accessibility for purchasing hookah supplies.

Keywords: Young adult tobacco use, Hookah, Qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

The literature has indicated both long and short-term hazardous health effects associated with hookah smoking, including lung cancer, respiratory illness, and increased toxicant exposure. 1–4 For instance, a two condition study crossover design revealed that a single hookah smoking episode produced peak carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) levels three times higher than those observed in a single cigarette session, and similar peak plasma nicotine levels to those observed in cigarette smoking. 3 Furthermore, puff topography data and hookah smoke analyses indicated a 45 minute hookah session produced over 40-fold the smoke volume of that produced from a single cigarette and, in addition to carbon monoxide (CO) and nicotine, the smoke contained exposure to various toxicants including carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, volatile aldehydes, and various heavy metals. 3

Despite the available research indicating strong associations between hookah smoking and adverse health outcomes, hookah smoking prevalence rates pose a rising global health concern, particularly among adolescents and young adults. 3 Various university-based cross sectional studies have established rising hookah use prevalence rates ranging from 20–40% for lifetime use and 5–20% for current use. 5–9 Furthermore, dual hookah and cigarette use has been reported at 58.7% in a university study sample. 9 Moreover, trends in early hookah smoking, as observed in a 13-month longitudinal study, indicated a gradual upward trend in participant hookah ever use from pre-college (29%) to freshman year of college (34%), and from the end of the academic year (41%) to the end of summer (45%). 8

Nonetheless, while downward trends have been observed in college students’ cigarette use, evidence based findings suggest that hookah use has synchronously been on the rise. 10,2 This polarized phenomenon across cigarette users and exclusive hookah users suggests attitudinal differences among both forms of tobacco consumption. Cross-sectional studies examining hookah smoking risk perceptions among the college population have noted that positive perceptions toward hookah smoking as well as perceptions of reduced health risks (relative to cigarette smoking) were both significantly associated with current hookah use and intention to use hookah tobacco in the future. 6,11,5 For instance, a cross-sectional study among first and second year undergraduate and graduate college students examining positive and negative attitudes as well as normative beliefs regarding hookah use indicated positive attitudes toward hookah use were significantly associated with current hookah use and intention to use hookah tobacco in the future. 5 On the other hand, results regarding negative attitudes toward hookah yielded nonsignificant findings, for both current hookah use and future intentions to engage in hookah use.

The purpose of this study was to examine current hookah users’ positive and negative normative beliefs and attitudes, with respect to hookah use, in order to further elucidate the rise in hookah smoking prevalence among young adults, and help uncover why these tobacco consumption activities are perceived differently. These study findings are expected to inform targeted educational health approaches as well as cessation programming for young adults.

METHODS

Six focus groups were conducted with hookah smokers aged 18–24 years. Focus group size ranged from 5 – 9; totaling 40 participants in the study. Four groups were composed of college students from a large university in southeastern United States, and two groups included non-college student young adults. Focus groups were split between frequent and infrequent hookah users. Hookah use frequency was defined as infrequent for individuals who had smoked hookah three times per month or less and frequent for those who had smoked more than three times per month, approximately once a week or more. Participant recruitment consisted of: 1) flyers posted around the community (targeted young adult high traffic areas, such as movie theatre parking lots, bars, malls, and restaurants); 2) on-campus flyers posted at bus stops, housing complexes, and near dorms. IRB approval was obtained from the university prior to focus group data collection and all participants received full study disclosure from the research team before consenting to participate. The data were analyzed using a grounded theory approach.12

Participant demographics included a mean age of 19 years (SD 1.4) with just over half (55%) females. Overall, participants’ racial background was predominantly white (72%), followed by Asian (10%), and black (7.5%). The ethnic composition included 30% who identified as Hispanic, and 12.5% who identified as Middle Eastern descent. Additionally, occupation status primarily consisted of full-time students (75.5%); with part-time workers (15%), full-time workers (10%), and unemployed individuals (5%).

All six focus groups were structured in the same manner and averaged 40 minutes in duration. Following past work using Outcome Expectancy Theory applied to cigarettes,13 participants were asked to complete a word elicitation exercise, whereby participants were asked to complete the phrase “Hookah smoking is ____”. The word elicitation exercise was followed by a categorizing process, wherein participants were asked to categorize the list of words that had been generated during the word elicitation activity as either positive or negative and into the following five hookah literature themes identified by the researchers: social, harmful, toxins, socially acceptable and other. Next, participants were asked to rank each category in descending order with respect to level of importance. Lastly, participants were asked to individually describe their first hookah smoking experience, whether or not they currently owned a hookah pipe, and if so, how they had obtained the hookah pipe.

The research team conducting each focus group consisted of one professor with expertise and training in qualitative data collection (moderator) and one graduate research assistant who took notes and audio recorded the focus group session; recordings were then transcribed verbatim for data analysis.

The analysis was first performed by reading the data once and listing the words elicited under the categories stated by participants. All six focus groups indicated a much larger set of positive perceptions and behavioral beliefs, with respect to hookah use, as opposed to negative perceptions and behavioral beliefs. Closer examination comparing all six groups’ lists of positive and negative categories (derived from the word elicitation process) eventually uncovered trends in intersecting generational characteristics between hookah use and positive perceptions and behavioral beliefs as key influencers for hookah smoking initiation.

The data analysis was conducted using selective coding procedures. 12 Coding consisted of concepts that emerged from each groups’ list of positive and negative categories, such as beliefs regarding hookah smoking’s non-addictive nature, ability to choose a variety of flavors and mix them, and perception of a foreign cultural practice. The emergent identification of generational identity as an overarching phenomenon within participants’ hookah smoking behavior allowed the researchers to draw across both positive and negative categories.

The purpose of the project was to solicit hookah users to provide outcomes associated with hookah smoking. Specifically, the analysis aimed to uncover why hookah smoking is appealing to the 18–24 age group. During analysis emerging similarities in generational traits to hookah smoking characteristics within the data steered the analysis to a focus on hookah smoking behavior initiation in the context of the Millennial Generation, those born from 1977 to 1995 (demonstrated in results section).

Emerging theme analyses and interpretations were confirmed via a peer review process until no new themes could be identified. This process led to the development of nine major themes: autonomy, personalization, novelty appeal, convenience, globally oriented, entertainment, collaboration, health conscious, and valuing their social network. Each of these themes represented key cultural determinants which were explored as dimensions of the central phenomenon: hookah smoking initiation among the Millennial Generation.

RESULTS

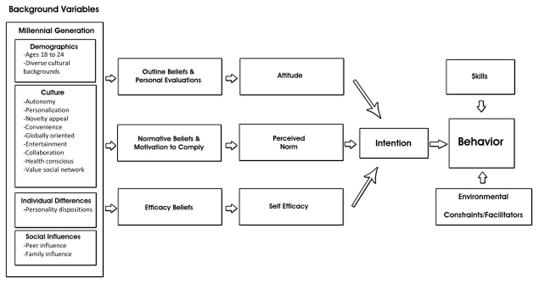

Millennial hookah users shared a much larger set of positive behavioral beliefs, as opposed to negative behavioral beliefs, with respect to hookah use, as evidenced by the data. These observations are best understood through the application of the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction (see Figure 1). 14 The Integrative Model is a revision of the reasoned action approach, which adds control beliefs as a predictor of behavioral intention to the original three constructs: behavioral intention, attitude, and subjective norm. Furthermore, the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction extends the scope of subjective norm by acknowledging the role of skills and environmental constraints and/or facilitators as moderators of the intention–behavior relationship in addition to: 1) attitude (individual’s evaluation of behavior favorability), 2) perceived norms (social pressure expected from behavior performance), and 3) self-efficacy (perceived capability to successfully perform the behavior). 14

Figure 1.1.

The integrative model of behavioral prediction in the context of millennial hookah smoking initiation

When viewed concurrently with the integrative model, observations on hookah smoking initiation among Millennials revealed the majority of hookah users lacked the necessary skills (e.g., assembly and pipe preparation, inhalation methods, etc.) for their initial smoking experience. Therefore, contextual factors such as social network support and the large extent to which members of the individual’s social network were also engaging in the behavior served as influential facilitators for the behavior initiation process among this age group. For instance, one participant noted the following regarding his initial hookah smoking experience: “It was also in a big group, people I was comfortable with, I probably would have been more nervous and embarrassed when I didn’t know what I was doing. Yeah, it was fun.”

Additionally, hookah smoking was described as a unique social experience with cultural characteristics closely aligning to those of the Millennial Generation. Numerous positive links between generational characteristics and hookah use emerged as key determinants of behavior initiation in the data. As illustrated in Figure 1, Millennial characteristics15 served as the overarching commonality among the hookah smoking initiation characteristics observed in this sample. The most notable trends were observed within the cultural category, which included the following Millennial characteristics: autonomy, personalization, novelty appeal, convenience, globally oriented, entertainment, collaboration, health conscious, and valuing their social network.

Autonomy

The majority of hookah users expressed a strong sense of perceived control over their hookah use; this factor presented itself as a driver for greater behavioral intention. Trends in the data suggested Millennial hookah users had commonly held beliefs that hookah use was non-addictive and viewed their recurrent use as a transient behavior that was a part of their college experience. As one student stated: “Sometimes I will smoke hookah a couple days a week, and then other times I’ll go several weeks or several days without doing it or considering it. I wouldn’t say hookah is addictive.”

Personalization

From the hookah pipe preparation process to mixing flavors and performing smoke tricks, the ability to personalize the hookah smoking experience was a highly attractive smoking feature that correlated with Millennials’ desire for personalization, creativity, and within-group individuality. Young Millennials noted the hookah pipe’s preparation process as one that catered to a wide array of smoker preferences ranging from thicker smoke to longer lasting tobacco. For instance, one participant noted “So, if you put two coals down you’ll get thicker smoke, but the tobacco will burn faster; it’s kind of like a preference.”

Similarly, participants communicated the ability to further personalize the preparation process by experimenting with combining flavor elements in the hookah pipe’s setup process. For instance, several preparation flavoring options noted included: carving an orange or an apple to use as a bowl, and using ice, wine, milk, or energy drinks in the water bowl that serves to cool the smoke for the user. However, apart from the wide variety of flavor choices and the ability to mix flavors, some flavoring options were also distinguished as catering to particular ethnic preferences. For instance one participant stated:

And also like, as your culture too, cause like we smoke “pan”. But a lot of, like if you go to shops that are owned by I would say maybe like just Americans or that they probably wouldn’t have that flavor, but if you go to a shop that is owned by like Indian people, they would definitely have that flavor.

These three distinct versatile areas of ‘expertise’ (preparation, flavor mixing, and smoke tricks), as termed by participants, also served as both an opportunity to promote within-group individuality (via a reputation corresponding to their level of skill), as well as an opportunity for a dynamic experience, thus creating a “unique [hookah smoking] experience every time”.

Novelty appeal

The majority of participants expressed a mystical appeal tied to their initial unfamiliarity with hookah smoking and its role as a cultural practice. From the typical hookah lounge’s décor to the dim lighting and comfortable seating, the atmosphere created by hookah smoking settings was perceived as novel and there was a notable level of respect tied to partaking in this foreign cultural custom. One participant stated:

Even if it’s not a part of your culture I feel like that’s something that makes it more acceptable is like the, you can look at it from the perspective that like you’re trying someone else’s, like something from their culture.

Convenience

Participants reiterated the ease and convenience of obtaining access to a hookah bar or purchasing a hookah pipe themselves. Many of the hookah users indicated that hookah supplies were widely available in bulk at brick-and-mortar shops, online, and even at gas stations. In addition, Millennial users also noted that the legality of hookah smoking indoors as well as the 18-year age limit were significant drivers for use among individuals under the age of 21.

Globally oriented

Closely tied to the novelty perceived from a foreign cultural custom, a high level of tolerance and appreciation for cultural diversity was also found to play a role among participants’ hookah smoking initiation. Many participants expressed a yearning for authentic ethnic experiences strongly characterizing the multicultural peer groups of the Millennial Generation. For instance, one participant stated: “Something you do in like their culture, rather than, “Oh, I’m smoking tobacco.”

Entertainment

Many socially entertaining elements also emerged as key determinants of hookah smoking initiation. For instance, smoke tricks such as blowing smoke rings or blowing smoke bubbles were commonly described as “fun” and “visually stimulating”. Other subcategories identified within this theme included competition and creativity with respect to the hookah smoke. Individuals noted the hookah smoke served as a vehicle to express creativity and their competitive nature via smoke tricks. One participant stated: “It’s entertaining. Like even just to watch other people do it. Actually, you know some people like to compete about who can be the most creative, so . . . like “O”s”.

Collaboration

The entire process of hookah pipe assembly, preparation, and smoking session was described as an organized effort. Varying tasks were shared (such as packing the bowl, cleaning, and pipe assembly) and assigned among group members. Compromise played a key role in the process from taking turns on assigned tasks to deciding flavor choices. Furthermore, participants described an element of trust in each member’s ability to carry out their tasks properly so as to not ruin the group’s hookah smoking experience via improper setup or even breaking the hookah pipe. Similarly, an enjoyable hookah smoking experience was equally contingent on all members’ willingness to share hoses within the group. Thus, the contingency for a minimal required skill level on pipe assembly and preparation was also conducive to within-group mentorship roles during the initial stages of knowledge transfer and skill acquisition.

Health conscious

Millennial hookah users were notably aware of both the negative and positive consequences that may stem from continued hookah use; however, behavioral beliefs were primarily fixated on the perception that hookah smoking was a healthier alternative (had less toxins) as compared to cigarette smoking. For instance, when participants were asked to classify the elicited words or phrases, the following words or phrases were classified as both enjoyable and harmful: stress reliever, escape from other parts of the party, a lot of smoke at once, light-headed, and complementary to other substances. In addition, natural hookah-related product varieties were also described to contribute to this healthier comparative perception of hookah smoking as compared to other forms of tobacco consumption. One participant stated: “Can it be healthy too? There’s like, instead of like fast acting coals there’s natural coals that they use so I guess that people think that those are better.”

Additionally, healthier comparative beliefs held by Millennials were also closely associated with hookah pipe aesthetics, pleasant scent, “smoother” smoke (for passersby and smokers alike), and low likelihood of daily use, as compared to cigarettes.

Value social network

Millennial hookah users primarily described the hookah smoking experience as a highly accepted recreational social interaction predominantly initiated by strong peer and (closely followed by) family influences. Participant self-efficacy was shown to be significantly enhanced via these intimate and small social group settings, where peers were often described as supportive and encouraging of the individuals’ hookah smoking initiation via comments such as “it’s easy”, “this is what you do” or “it tastes good”. Family influences were often depicted as similarly socially pressing small and intimate gatherings, with many family members (e.g., parents, cousins, and grandmothers) gifting hookah pipes for birthdays and high school graduations. Such social influences were key drivers in shaping users’ normative beliefs regarding hookah use. Thus, these findings are consistent with the behavior initiation process as described by the Integrated Model of Behavioral Prediction, being that social influences played a key role on all three determinants of intention: outcome, normative, and efficacy beliefs. 14 Thus, efficacy beliefs were enhanced via social influences as well as hookah characteristics closely corresponding to those of Millennials’ generational culture.

Environmental Access

While facilitators appeared to outweigh participants environmental constraints, those that were expressed by Millennials included factors linked to convenience, such as affordability and accessibility. For instance, one participant noted he had discontinued use after his initial hookah smoking attempt until after he arrived to the college environment.

I didn’t really get a chance to do it again after [high school] that up until I got to college and one of the guys in the fraternity had one and so I started back doing it again and then I eventually decided to get my own.

On the other hand, facilitators were abundant and typically included: the density of hookah shops and hookah bars/lounges in surrounding neighborhood environments, legality, age limit, convenience of online hookah-related purchases, affordability, sorority/fraternity affiliation, and college party environment (e.g., house parties). Affordability emerged as both a constraint and facilitator depending upon the participant’s locality, with urban environments tending to have higher price points. Additionally, findings also revealed smoking skill level to moderate behavior performance, although social influences were typically strong enough to boost individuals’ confidence in initiating hookah smoking despite their commonly low level of skill from the outset, as many participants indicated that hookah smoking had been their first smoking experience.

As previously mentioned, the hookah smoking experience was described as a highly collaborative experience, with the majority of the group members expressing their willingness to share hookah skills and knowledge among initiating group members. One participant stated:

Yeah the same, like, when they explain it to you, cause when you don’t know how to do it, you breathe in through your lungs and that’s when you cough. So, you just breathe in through your mouth. When you get more used to it you get more confident. But I wasn’t confident my first time.

Smoking Experience

Although the majority of participants initiating hookah smoking did not have former smoking experience, those who did evidenced higher levels of self-efficacy for hookah smoking. Moreover, data on participants with greater hookah smoking frequency indicated trends in voicing more of the possible negative aspects of hookah smoking, as compared to their lower smoking frequency counterparts. Topics uncovered included: discontent with group compromise over flavor choice, boredom emerging from longer hookah sessions (lasting more than 2 hours), greater report of the negative side effects from prolonged hookah smoking (e.g., irritated throat), and annoyance from others within the group (e.g., blowing too many smoke rings in another’s face).

DISCUSSION

This study’s findings highlight the powerful influence of contextual environmental factors, such as individuals’ generational culture, with respect to corresponding perceptions toward and initiation of hookah smoking. Findings from this study are consistent with the literature denoting a predominantly held perception of hookah smoking as a less toxic form of tobacco consumption (when compared to cigarette smoking) among individuals aged 18–24.6,11,5,16 Overall, participant responses reflected congruence with existing behavior initiation theory. The nine generational culture determinants identified (autonomy, personalization, novelty appeal, convenience, globally oriented, entertainment, collaboration, health conscious, and valuing their social network) manifested as key cultural determinants following the schema for behavior performance initiation described by the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction. 14 While the generational culture determinants identified were observed to strengthen hookah smoking behavior initiation, individuals’ smoking skill level, as well as environmental constraints (e.g., affordability) or facilitators (accessibility), were found to moderate hookah smoking initiation among Millennials.

Study limitations included the highly structured format in which the focus group interviews were conducted, thus reducing data richness. For instance, participants were not able to form categories of their own in which to categorize the words as these were developed from the literature. Similarly, despite the moderators’ effective use of probes during the focus group interviews, ranking exercises (for each predetermined hookah category) hindered the generation of more elaborate responses from participants. Moreover, given the sample composition, drawing college student (4 groups, 30 participants) versus non-student group (2 groups, 10 participants) comparisons was another study limitation. While efforts were made to recruit community-dwelling young adults, very few contacted the research team to participate in the study. Generational differences, however, should transcend college vs non-college status and thus are perhaps not important distinctions for hookah use.

Given the data examined provided an understanding of key factors driving hookah smoking initiation among the young adult population, future implications for this study’s findings include enhanced hookah smoking prevention and cessation programming capitalizing on the promotion of positive health behaviors that support and/or align with Millennial characteristics. For intervention development, generational culture determinants identified in this study can serve as generative schema17 conveying broader motivating constructs conducive to Millennials’ choice to initiate hookah smoking. Using a generative approach17, campus health promotion initiatives can seek to develop intervention models satisfying identified Millennial generational culture schemata via substitute positive recreational outlets for young adults. Ideal positive recreational outlets would foster opportunities for schemata such as autonomy, personalization, novelty appeal, convenience, globally oriented, entertainment, collaboration, health consciousness, and a valued social network to flourish among young adults.

In addition, campus health promotion efforts must also seek to dispel prevailing myths regarding hookah smoking as a healthier alternative to cigarette smoking. Moreover, anti-hookah smoking health education initiatives should be reinforced by policy efforts aiming to include hookah smoking in all current smoke-free ordinances. The lack of policies restricting hookah smoking indoors has exacerbated misconceptions regarding hookah smoking’s safety, and hookah bar establishments continue to remain exempt from clean indoor air legislation.18, 19 Policy efforts can help curb young adult misconceptions regarding the safety of hookah use and reduce accessibility. Examples of policy implications for the reduction of hookah smoking initiation and continued use among the young adult population could include: raising hookah bar age limits, restrictions for indoor smoking, and limiting the density of hookah cafes surrounding areas with high young adult populations, such as near University campuses.

We observed current young adult hookah users’ perceptions, attitudes, and normative beliefs regarding hookah smoking harmfulness as compared to other forms of tobacco consumption.

Millennial Generational traits served as the overarching commonality among the hookah smoking initiation determinants observed.

Notable cultural generational trends identified included: autonomy, personalization, novelty appeal, convenience, globally oriented, entertainment, collaboration, health conscious, and valuing their social network.

Health policy implications include: raising hookah bar age limits, implementing indoor smoking restrictions, and limiting the ease of accessibility for purchasing hookah supplies.

Acknowledgments

All authors take full responsibility for the integrity of the data.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health: National Cancer Institute (Grant Number CA165766, principal investigator Tracey Barnett, PhD).

Footnotes

Ethical approval

University of Florida Institutional Review Board.

Competing Interests

None declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, "tar", and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. [Accessed August 4, 2014];Food Chem Toxicol. 2005 43(5):655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.12.013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15778004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson D, Aveyard P. Waterpipe smoking in students: prevalence, risk factors, symptoms of addiction, and smoke intake. Evidence from one British university. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):518–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Honeine R, Jaoude PA, Irani J. The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(3):834–57. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett TE, Smith T, He Y, et al. Evidence of emerging hookah use among university students: a cross-sectional comparison between hookah and cigarette use. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eissenberg T, Ward KD, Smithsimone S, Maziak W. Waterpipe tobacco smoking on a U.S. College campus: prevalence and correlates. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(5):526–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Primack BA, Sidani J, Agarwal AA, Shadel WG, Donny EC, Eissenberg TE. Prevalence of and associations with waterpipe tobacco smoking among U.S. university students. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(1):81–6. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fielder RL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Prevalence, frequency, and initiation of hookah tobacco smoking among first-year female college students: a one-year longitudinal study. Addict Behav. 2012;37(2):221–4. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Primack BA, Shensa A, Kim KH, et al. Waterpipe smoking among U.S. university students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):29–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnett TE, Shensa A, Kim KH, Cook RL, Nuzzo E, Primack BA. The predictive utility of attitudes toward hookah tobacco smoking. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(4):433–9. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.4.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun RE, Glassman T, Wohlwend J, Whewell A, Reindl DM. Hookah use among college students from a Midwest University. J Community Health. 2012;37(2):294–8. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research, techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendricks PS, Brandon TH. Smoking expectancy associates among college smokers. Addict Behav Feb. 2005;30(2):235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and Changing Behavior, The Reasoned Action Approach. Taylor & Francis; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Nielsen Company. MILLENNIALS-BREAKING THE MYTHS. The Nielsen Company; [Accessed August 4, 2014]. https://www.cangift.org/upload/market-monitor-april-2014-millennial-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2008;10:393–398. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edberg MC, Edberg AP, Baker DE, et al. Essentials of Health Behavior. Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noonan D. Exemptions for hookah bars in clean indoor air legislation: a public health concern. Public Health Nurs. 2010;27(1):49–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Primack BA, Hopkins M, Hallett C, et al. US health policy related to hookah tobacco smoking. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):e47–51. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]