Abstract

The cycle of mitochondrial division and fusion disconnect and reconnect individual mitochondria in cells to remodel this energy-producing organelle. Although dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) plays a major role in mitochondrial division in cells, a reduced level of mitochondrial division still persists even in the absence of Drp1. It is unknown how much Drp1-mediated mitochondrial division accounts for the connectivity of mitochondria. The role of a Parkinson’s disease-associated protein—parkin, which biochemically and genetically interacts with Drp1—in mitochondrial connectivity also remains poorly understood. Here, we quantified the number and connectivity of mitochondria using mitochondria-targeted photoactivatable GFP in cells. We show that the loss of Drp1 increases the connectivity of mitochondria by 15-fold in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). While a single loss of parkin does not affect the connectivity of mitochondria, the connectivity of mitochondria significantly decreased compared with a single loss of Drp1 when parkin was lost in the absence of Drp1. Furthermore, the loss of parkin decreased the frequency of depolarization of the mitochondrial inner membrane that is caused by increased mitochondrial connectivity in Drp1-knockout MEFs. Therefore, our data suggest that parkin negatively regulates Drp1-indendent mitochondrial division.

1. Introduction

Mitochondria are critical for many cellular and physiological processes such as ATP production, metabolism, cell death and aging [1,2]. Although mitochondria form many discrete structures in cells, these structures continuously connect and disconnect via highly regulated membrane remodeling processes, fusion and division [3,4,5]. Controlling mitochondrial connectivity is fundamental to the maintenance of the function of this essential organelle. Decreased mitochondrial division results in increased connectivity and size of this organelle, leading to inhibition of proper mitochondrial movements and removal by autophagy [2,6]. On the other hand, decreased fusion compromises mitochondrial connectivity, leading to inhibition of intramitochondrial mixing of mitochondrial components such as proteins, lipids and DNA [7,8]. Such defects in mitochondrial connectivity have been linked to human disorders such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy, autosomal dominant optic atrophy, Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease [9,10,11].

Dynamin-related protein 1, Drp1, is an evolutionarily conserved key mediator of mitochondrial division [12,13,14]. Mutations in human Drp1 result in a variety of developmental disorders that strongly affect the nervous system and can lead to neonatal death, microcephaly and pain insensitivity, and epilepsy [15,16,17]. Drp1 physically and genetically interacts with an E3 ubiquitin ligase, parkin, whose defects are associated with familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease. For example, it has been shown that parkin suppresses mitochondrial division by ubiquitinating Drp1 and promoting its proteosomal degradation in mammalian cells [18]. In contrast, in Drosophila, parkin promotes mitochondrial division; parkin mutants exhibit enlarged mitochondria that can be rescued via the overexpression of Drp1 [19,20]. Therefore, deciphering how Drp1 and parkin regulate mitochondrial connectivity would shed light on the many human diseases associated with defects in these proteins. In this study, we have developed an assay to measure the connectivity and number of mitochondria using mitochondria-targeted photoactivatable GFP, and we have quantitatively assessed the role of Drp1 and parkin in mitochondrial morphology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts

Wild-type (WT), Drp1-KO, parkin-knockout (KO), Drp1parkin-KO mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were immortalized spontaneously via serial passage, as described [21,22]. The MEFs were cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin and streptomycin [21].

2.2. Lentivirus production

A lentiviral vector carrying mitochondria-targeted Su9-GFP (GFP fused to the Su9 presequence) [23] was generated by subcloning Su9-GFP into pHR-SIN-CSGW [14,24]. A plasmid containing Su9-photoactivatable GFP (PAGFP) was created by replacing GFP with phosoactivatable GFP [25,26] into the Su9-GFP plasmid. Lentivirus carrying Su9-GFP or Su9-PAGFP was generated as described previously [14,24]. Briefly, pHR-SIN-CSGW carrying Su9-GFP or Su9-PAGFP was cotransfected in HEK293T cells with two other constructs, pHR-CMV8.2ΔR and pCMV-VSVG, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Two days after transfection, the culture medium of transfected cells containing released lentiviruses was collected. The viruses were quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

2.3. Fluorescence microscopy

WT, Drp1-KO, parkin-KO and Drp1parkin-KO MEFs were used for the analysis. Cells carrying Su9-GFP or Su9-PAGFP were stained with 14 nM tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRE) for 20 minutes in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium containing 10% FBS media. The culture medium was replaced with L-15 Lebovitz (1X) medium supplemented with 14 nM TMRE, and the cells were examined using a Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope with a 63× objective lens and an environmental enclosure to control temperature, CO2 and humidity. Images were obtained at 10-second intervals for a total duration of 15 minutes or 1 hour. To measure the area of single mitochondria in cells carrying Su9-PAGFP, a portion of a single mitochondrion that was observed based on TMRE staining was irradiated using a 405 nm laser at 50% power to photoactivate the Su9-PAGFP in the cells. Immediately after the photoactivation of Su9-PAGFP (3–5 seconds), a fluorescent signal of the activated Su9-PAGFP was recorded. The total mitochondrial area of the mitochondria was calculated based on the TMRE staining. The number of mitochondria in each cell was determined by dividing the area of total mitochondria (TMRE signal) by that of a single mitochondrion (Su9-PAGFP signal). The fluorescent images were quantified and analyzed using Image J software and Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. A Drp1-mediated mechanism accounts for ~95% of mitochondrial division

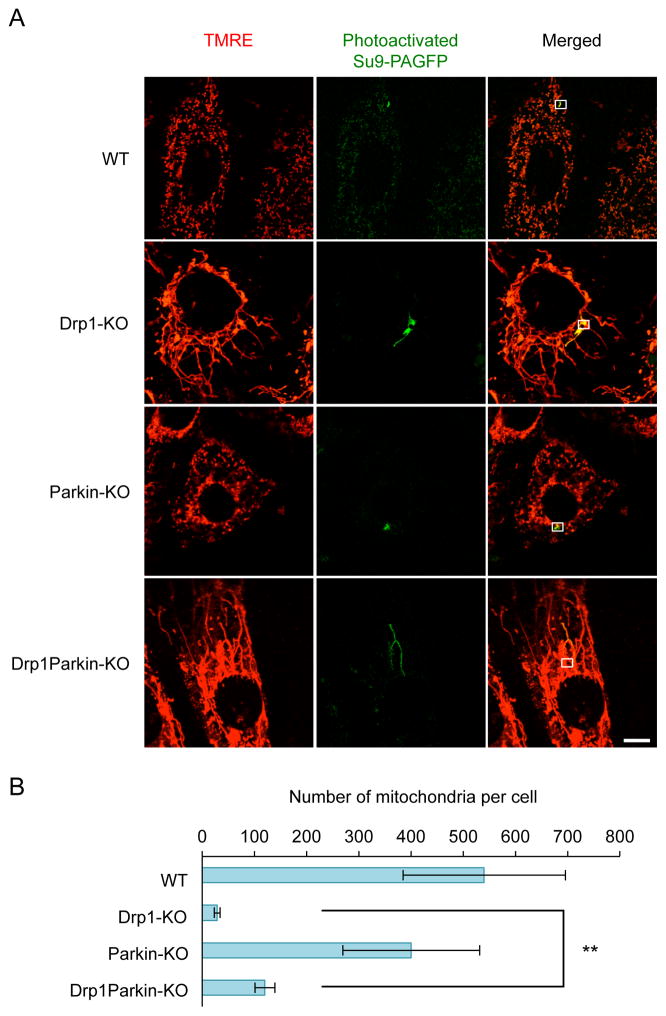

To quantitatively assess the number and connectivity of mitochondria in cells, we adapted matrix-targeted Su9-PAGFP [21,23,26]. WT MEFs were infected with lentiviruses carrying Su9-PAGFP and stained with TMRE, a red fluorescent dye that labels mitochondria in live cells (Fig. 1A) [27]. We located a part of a single mitochondrion using TMRE staining and irradiated it with a short pulse of laser irradiation to photoactivate Su9-PAGFP on the scanning laser confocal microscope (Fig. 1A). We confirmed that the laser irradiation did not affect the overall mitochondrial morphology. Photoactivated Su9-PAGFP was immediately diffused into the connected matrix space, labeling a single mitochondrion within 5 seconds. Within 3–5 seconds of irradiation, we captured the image for TMRE and activated Su9-PAGFP; the effect of mitochondrial fusion on the diffusion of Su9-PAGFP was negligible. By dividing the area of activated Su9-PAGFP signal by that of the TMRE signal, we calculated the relative area of a single mitochondrion containing Su9-PAGFP (Fig. 1B). We then converted the relative area into the number of mitochondria in each cell. We found that a signal mitochondrion represents roughly 0.2% of the total mitochondria area in each cell; we accordingly estimated that WT MEFs contain roughly 500 mitochondria on average (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Parkin controls the number of mitochondria in the absence of Drp1.

(A) Wild-type, Drp1-KO and parkin-KO and Drp1parkin-KO MEFs expressing Su9-PAGFP were stained with TMRE to visualize all of the mitochondria. A small fraction of the mitochondria were photoactivated using a 405-nm laser on a Zeiss confocal microscope. Within 3–5 seconds after photoactivation, images were obtained of both the photoactivated Su9-PAGFP and TMRE. The boxes correspond to areas that were subjected to photoactivation. (B) To determine the connectivity of mitochondria, the area containing Su9-PAGFP signals was divided by the area containing the TMRE signal (total mitochondria). The number of mitochondria was estimated by reversing the connectivity. Values represent mean ± SEM (n= 5). The Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. The scale bar corresponds to 10 μm.

To assess decreases in the activity of mitochondrial division in the absence of Drp1, we applied our Su9-PAGFP assay to Drp1-KO MEFs. As expected based on previous studies [14,21], mitochondrial tubules are highly connected in Drp1-KO MEFs. We found that the number of mitochondria decreased by approximately 15-fold in Drp1-KO MEFs compared with WT MEFs (Figs. 1A and B). Importantly, mitochondria are still not completely connected; there were roughly 30 separate mitochondria per cell in Drp1-KO MEFs on average (Figs. 1A and B). These data suggest that while Drp1 accounts for the majority of mitochondrial division activity, there is a Drp1-independent mechanism that maintains separate mitochondria in MEFs.

3.2. Parkin negatively regulates the number and connectivity of mitochondria via a Drp1-independent mechanism

Next, we tested the function of parkin in mitochondrial connectivity in the presence or absence of Drp1-mediated mitochondrial division in parkin-KO and Drp1parkin-KO MEF. We found that, similar to WT MEFs, parkin-KO MEFs contained roughly 500 mitochondria on average (Fig. 1A and B). Intriguingly, the loss of parkin increased the number of mitochondria by roughly 3-fold in Drp1parkin-KO MEFs (roughly 100 mitochondria per cell) relative to Drp1-KO MEFs (roughly 30 mitochondria per cell) (Fig. 1A and B). Therefore, parkin controls the number and connectivity of mitochondria when Drp1-mediated mitochondrial division is absent.

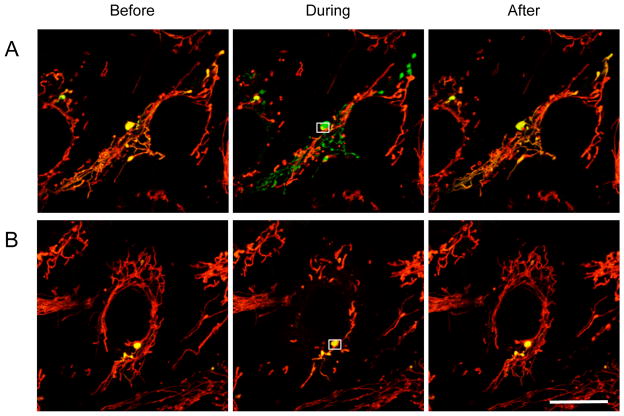

3.3. Connected mitochondria transiently depolarize in a synchronized manner

TMRE labels mitochondria in a manner that depends on the membrane potential across the inner membrane [27]. It has been shown that TMRE fluorescence transiently drops due to depolarization in a fraction of elongated mitochondria in cells defective in Drp1 [28,29]. The additional inhibition of mitochondrial fusion results from decreased Opa1, which decreases the connectivity of mitochondria and decreases the rate of the fluorescent flickering [28]. To further test our model that parkin loss reduces the connectivity of mitochondria in Drp1parkin-KO MEFs, we examined TMRE flickering in cells. We reasoned that if mitochondrial connectivity is decreased in Drp1parkin-KO MEFs compared with Drp1-KO MEFs, the frequency of TRME flickering should decrease in parallel with the decreased connectivity. We first determined whether TMRE fluorescence flickers in connected single connected mitochondria, but not separate mitochondria. We stained mitochondria using TMRE in Drp1-KO MEFs expressing Su9-PAGFP and first photoactivated Su9-PAGFP in a small portion of the mitochondria to label the connected single mitochondrion (Fig. 2). We subsequently observed Su9-PAGFP and TMRE fluorescence for the next 15 min. The frequency of TMRE flickering was unaffected by the photoactivation of Su9-PAGFP. We found that the TMRE flickering was synchronized in a connected mitochondrion (Fig. 2A). In another example, the TRME fluorescence flickered in mitochondria in which Su9-PAGFP was not photoactivated; TMRE fluorescence in nearby mitochondria in which Su9-PAGFP was activated remained unchanged (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the membrane potential drops in a synchronized manner in connected mitochondria of Drp1-KO MEFs.

Figure 2. TMRE flickering occurs in connected mitochondria in Drp1-KO MEFs.

Drp1-KO MEFs carrying Su9-PAGFP were stained with TMRE and observed at 10-second intervals using laser confocal microscopy. Selected movie frames are presented before (−10 seconds), during (0 seconds) and after (+40 seconds) TMRE flickering. The cell in (A) exhibits TMRE flickering in connected mitochondria labeled by photoactivated Su9-PAGFP. The cell in (B) shows TMRE flickering in mitochondria that do not have photoactivated Su9-PAGFP. The scale bar corresponds to 20 μm.

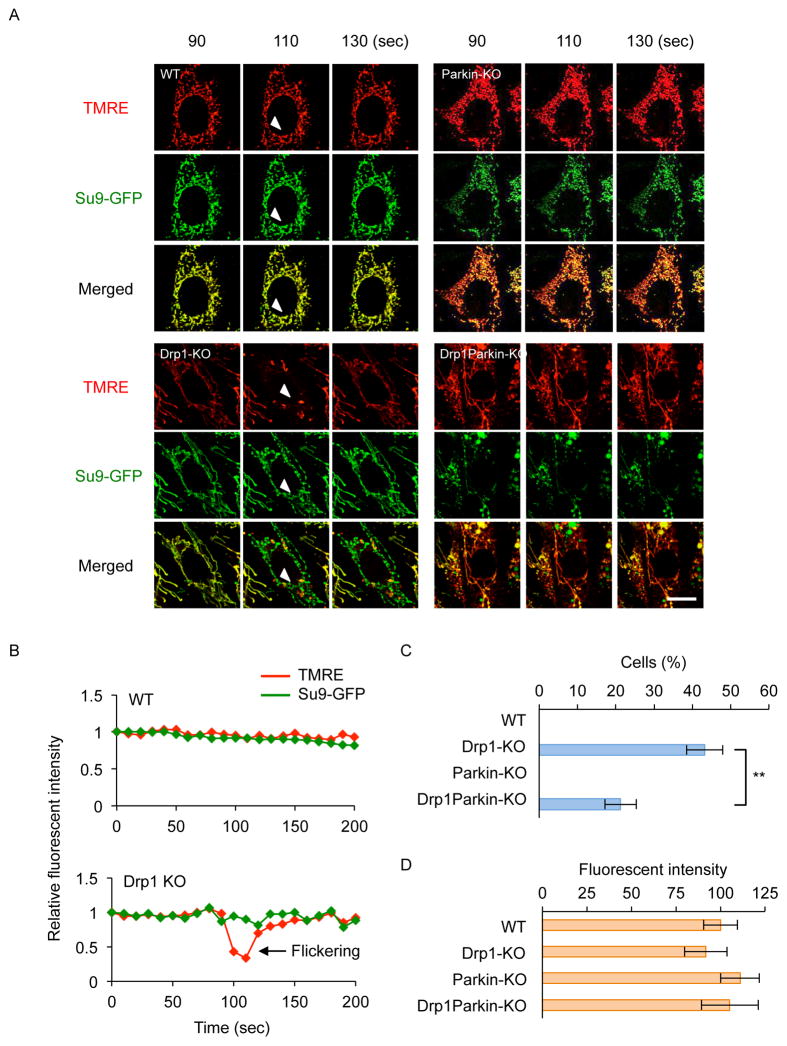

3.4. Parkin loss decreases the frequency of TMRE flickering in Drp1-KO MEFs

We then compared the frequency of TMRE flickering in WT, Drp1-KO, parkin-KO and Drp1parkin-KO MEFs (Fig. 3). In this experiment, MEFs that carried Su9-GFP were stained with TMRE and observed for 1 hour using laser confocal microscopy. In WT MEFs, the fluorescent intensity of TMRE and Su9-GFP remained relatively constant (Figs. 3A and B, WT). In contrast, Drp1-KO MEFs exhibited a transient drop in the fluorescent intensity of TMRE, but not that of Su9-GFP (Figs. 3A and B, Drp1-KO). Approximately 40% of Drp1-KO MEFs exhibited at least one flickering event over the course of one hour (Fig. 3C). When we examined parkin-KO MEFs, we found no TMRE flicking, similar to WT MEFs, over the observation duration (Fig. 3A and C). In contrast, the loss of parkin exhibited a dramatic impact on the frequency of TMRE in the absence of Drp1; Drp1parkin KO MEFs significantly decreased the number of cells that showed TMRE flicking by roughly 50% compared with Drp1-KO MEFs (Fig. 3A and C). This decrease is not due to decreases in the staining of TMRE since a similar fluorescent intensity of TMRE in mitochondria was observed in WT, Drp1-KO, parkin-KO MEFs and parkinDrp1-KO MEFs (Fig. 3D). Therefore, our data further support that the loss of parkin decreases the connectivity of mitochondria when Drp1-mediated mitochondrial division is blocked.

Figure 3. The frequency of TRME flickering decreases in the absence of parkin.

(A) Wild-type, Drp1-KO, parkin-KO and Drp1parkin-KO MEFs carrying Su9-GFP were stained with 14 nM TMRE and observed using laser confocal microscopy. Images were obtained at 10-second intervals for 1 hour. Images from three frames at 20-second intervals are shown. (B) Quantification of the Su9-GFP and TMRE signal in WT and Drp1-KO MEFs. The fluorescent intensity was measured on mitochondria indicated with the arrowheads in (A). (C) The percentage of cells that exhibited TMRE flickering in 1 hour was determined. Values represent mean ± SEM (n= 3). The Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. (D) The fluorescent intensity of TMRE. Cells were stained with TMRE in a 96-well plate and the fluorescence intensity was measure using a fluorescence plate reader. Values represent mean ± SEM (n= 6).

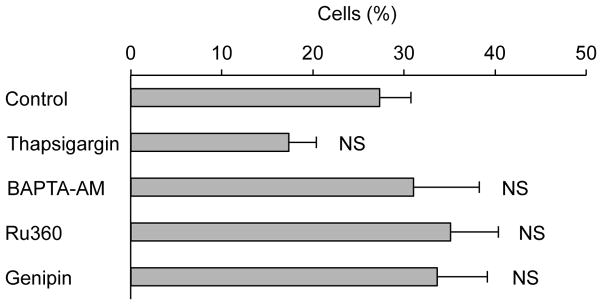

3.5. TMRE flickering is independent of calcium signaling and uncoupling protein 2

Finally, to analyze the mechanism underlying TMRE flickering, we determined whether TMRE flickering was mediated by uncoupling protein 2 in the mitochondrial inner membrane using its pharmacological inhibitor, genipin [30,31]. However, we found no significant effects of genipin on TMRE flickering in Drp1-KO MEFs (Fig. 4). We also tested whether a second messenger, calcium, regulated TMRE flickering using thapsigargin (which increases the cytoplasmic calcium concentration by inhibited calcium ATPaes in the ER membrane) [32], 1,2-Bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetrakis(acetoxymethyl ester) (BAPTA-AM, which is a membrane-permeable calcium chelator) [33], Ru360 (which inhibits calcium influx into mitochondria by inhibiting the mitochondrial calcium uniporter) [34]. We found that none of these inhibitors significantly affected the frequency of TMRE flickering in Drp1-KO MEFs. These results suggest that uncoupling protein 2 and calcium signaling likely do not control TMRE flickering in Drp1-KO MEFs.

Figure 4. Uncoupling protein 2 and calcium are dispensable for TMRE flickering.

Drp1-KO MEFs expressing Su9-GFP were stained with TMRE and treated with 1 μM thapsigargin (an ER-located calcium ATPaes inhibitor) for 60 minutes, 10 μM BAPTA-AM (a calcium chelator) for 60 minutes, 10 μM Ru360 (a mitochondrial calcium uniporter inhibitor) for 30 hours, or 10 μM genipin (an uncoupling protein 2 inhibitor) for 120 minutes. DMSO was used as a control. After the treatments, the cells were observed using laser confocal microscopy, and the percentage of cells that exhibited TMRE flickering over the 15-min observation time was recorded. Values represent mean ± SEM (n≧3). The Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

4. Discussion

In this study, we measured the connectivity and number of mitochondria using mitochondria-targeted photoactivatable GFP in cells. Our data suggest that Drp1 participates in the majority of mitochondrial division; a significant, albeit low, activity of mitochondrial division maintains separate organelles even in the absence of Drp1. Although it is currently unknown how mitochondria become separated without Drp1, several potential mechanisms may mediate such activity. For example, mitochondria may be torn into two structures by the traction force generated by the cytoskeleton and its motor proteins. In mammalian cells, mitochondria translocate along microtubules via interactions with dynein and kinesin motors that move in opposite directions [35,36]. If mitochondria are pulled by both dynein and kinesin, they can be pulled apart into two structures. As an alternative possibility, mitochondria may be cut in two by the force generated by the actin-mediated contractile ring during cell division. We also speculate that there is an unidentified, dedicated mechanism that divides mitochondria distinct from the Drp1 mechanism. It would be interesting to decipher such mechanisms underlying Drp1-independent mitochondrial division in future studies.

Previous studies using Drosophila have suggested that parkin promotes Drp1-mediated mitochondrial division and suppresses mitofusin- and Opa1-mediated mitochondrial fusion [19,20]. These functions of parkin predict that the loss of parkin increases the connectivity of mitochondria due to decreased Drp1-mediated mitochondrial division or increased mitochondrial fusion. However, the loss of parkin in a variety of cell types in mammals including MEFs (Fig. 1) [22], cardiomyocytes [22] and cerebellar Purkinje neurons [14] is not associated with an alteration in mitochondrial morphology. Our study has demonstrated that parkin regulates the connectivity of mitochondria in a Drp1-independent manner. We suggest that parkin negatively regulates Drp1-independent mitochondrial division—instead of stimulating mitochondrial fusion—since the impact of the loss of parkin is clearly observed only when the majority of mitochondrial division activity mediated by Drp1 is absent. Another Parkinson’s disease-related protein, alpha-synuclein, has been suggested to divide mitochondria in a Drp1-independent manner [37]. It would be interesting to test whether parkin is directly involved in this process as a part of this division machinery or whether it regulates the activity or abundance of components of the machinery via ubiquitination as an E3 ligase.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A Drp1-mediated mechanism accounts for ~95% of mitochondrial division

Parkin controls the connectivity of mitochondria via a mechanism that is independent of Drp1.

In the absence of Drp1, connected mitochondria transiently depolarize.

The transient depolarization is independent of calcium signaling and uncoupling protein 2.

Acknowledgments

We thank past and present members of the Iijima and Sesaki laboratories for discussions and technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants to M.I. (GM084015) and H.S. (GM089853).

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Madhuparna Roy, Email: mroy17@jhmi.edu.

Kie Ito, Email: kito5@jhmi.edu.

Miho Iijima, Email: miijima@jhmi.edu.

Hiromi Sesaki, Email: hsesaki@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Nunnari J, Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell. 2012;148:1145–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy M, Reddy PH, Iijima M, Sesaki H. Mitochondrial division and fusion in metabolism. Current opinion in cell biology. 2015;33C:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamura Y, Itoh K, Sesaki H. SnapShot: Mitochondrial dynamics. Cell. 2011;145:1158, 1158, e1151. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shutt TE, McBride HM. Staying cool in difficult times: Mitochondrial dynamics, quality control and the stress response. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishihara T, Kohno H, Ishihara N. Physiological roles of mitochondrial fission in cultured cells and mouse development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2015;1350:77–81. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Youle RJ, van der Bliek AM. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science. 2012;337:1062–1065. doi: 10.1126/science.1219855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrepfer E, Scorrano L. Mitofusins, from Mitochondria to Metabolism. Molecular cell. 2016;61:683–694. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishra P, Chan DC. Mitochondrial dynamics and inheritance during cell division, development and disease. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2014;15:634–646. doi: 10.1038/nrm3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itoh K, Nakamura K, Iijima M, Sesaki H. Mitochondrial dynamics in neurodegeneration. Trends in Cell Biology. 2013;23:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kandimalla R, Reddy PH. Multiple faces of dynamin-related protein 1 and its role in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2016;1862:814–828. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bereiter-Hahn J. Mitochondrial dynamics in aging and disease. Progress in molecular biology and translational science. 2014;127:93–131. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394625-6.00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bui HT, Shaw JM. Dynamin assembly strategies and adaptor proteins in mitochondrial fission. Current biology: CB. 2013;23:R891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sesaki H, Adachi Y, Kageyama Y, Itoh K, Iijima M. In vivo functions of Drp1: Lessons learned from yeast genetics and mouse knockouts. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1842:1179–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kageyama Y, Zhang Z, Roda R, Fukaya M, Wakabayashi J, Wakabayashi N, Kensler TW, Reddy PH, Iijima M, Sesaki H. Mitochondrial division ensures the survival of postmitotic neurons by suppressing oxidative damage. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;197:535–551. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheffer R, Douiev L, Edvardson S, Shaag A, Tamimi K, Soiferman D, Meiner V, Saada A. Postnatal microcephaly and pain insensitivity due to a de novo heterozygous DNM1L mutation causing impaired mitochondrial fission and function. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2016 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanstone JR, Smith AM, McBride S, Naas T, Holcik M, Antoun G, Harper ME, Michaud J, Sell E, Chakraborty P, Tetreault M, Majewski J, Baird S, Boycott KM, Dyment DA, MacKenzie A, Lines MA. DNM1L-related mitochondrial fission defect presenting as refractory epilepsy. European journal of human genetics: EJHG. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waterham HR, Koster J, van Roermund CW, Mooyer PA, Wanders RJ, Leonard JV. A lethal defect of mitochondrial and peroxisomal fission. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1736–1741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Song P, Du L, Tian W, Yue W, Liu M, Li D, Wang B, Zhu Y, Cao C, Zhou J, Chen Q. Parkin ubiquitinates Drp1 for proteasome-dependent degradation: implication of dysregulated mitochondrial dynamics in Parkinson disease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:11649–11658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.144238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poole AC, Thomas RE, Andrews LA, McBride HM, Whitworth AJ, Pallanck LJ. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1638–1643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709336105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng H, Dodson MW, Huang H, Guo M. The Parkinson’s disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14503–14508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803998105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakabayashi J, Zhang Z, Wakabayashi N, Tamura Y, Fukaya M, Kensler TW, Iijima M, Sesaki H. The dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 is required for embryonic and brain development in mice. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:805–816. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kageyama Y, Hoshijima M, Seo K, Bedja D, Sysa-Shah P, Andrabi SA, Chen W, Hoke A, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Gabrielson K, Kass DA, Iijima M, Sesaki H. Parkin-independent mitophagy requires Drp1 and maintains the integrity of mammalian heart and brain. The EMBO journal. 2014;33:2798–2813. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eura Y, Ishihara N, Yokota S, Mihara K. Two mitofusin proteins, mammalian homologues of FZO, with distinct functions are both required for mitochondrial fusion. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2003;134:333–344. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JS, Lee C, Bonifant CL, Ressom H, Waldman T. Activation of p53-dependent growth suppression in human cells by mutations in PTEN or PIK3CA. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:662–677. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00537-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bannwarth S, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Chaussenot A, Genin EC, Lacas-Gervais S, Fragaki K, Berg-Alonso L, Kageyama Y, Serre V, Moore DG, Verschueren A, Rouzier C, Le Ber I, Auge G, Cochaud C, Lespinasse F, N’Guyen K, de Septenville A, Brice A, Yu-Wai-Man P, Sesaki H, Pouget J, Paquis-Flucklinger V. A mitochondrial origin for frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis through CHCHD10 involvement. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2014 doi: 10.1093/brain/awu138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patterson GH, Lippincott-Schwartz J. A photoactivatable GFP for selective photolabeling of proteins and cells. Science. 2002;297:1873–1877. doi: 10.1126/science.1074952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry SW, Norman JP, Barbieri J, Brown EB, Gelbard HA. Mitochondrial membrane potential probes and the proton gradient: a practical usage guide. BioTechniques. 2011;50:98–115. doi: 10.2144/000113610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H, Yoon Y. Transient contraction of mitochondria induces depolarization through the inner membrane dynamin OPA1 protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:11862–11872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.533299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galloway CA, Lee H, Nejjar S, Jhun BS, Yu T, Hsu W, Yoon Y. Transgenic control of mitochondrial fission induces mitochondrial uncoupling and relieves diabetic oxidative stress. Diabetes. 2012;61:2093–2104. doi: 10.2337/db11-1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang CY, Parton LE, Ye CP, Krauss S, Shen R, Lin CT, Porco JA, Jr, Lowell BB. Genipin inhibits UCP2-mediated proton leak and acutely reverses obesity- and high glucose-induced beta cell dysfunction in isolated pancreatic islets. Cell metabolism. 2006;3:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toda C, Diano S. Mitochondrial UCP2 in the central regulation of metabolism. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2014;28:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thastrup O, Cullen PJ, Drobak BK, Hanley MR, Dawson AP. Thapsigargin, a tumor promoter, discharges intracellular Ca2+ stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2(+)-ATPase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:2466–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsien RY. New calcium indicators and buffers with high selectivity against magnesium and protons: design, synthesis, and properties of prototype structures. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2396–2404. doi: 10.1021/bi00552a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hajnoczky G, Csordas G, Das S, Garcia-Perez C, Saotome M, Sinha Roy S, Yi M. Mitochondrial calcium signalling and cell death: approaches for assessing the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in apoptosis. Cell calcium. 2006;40:553–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin MY, Sheng ZH. Regulation of mitochondrial transport in neurons. Experimental cell research. 2015;334:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarz TL. Mitochondrial trafficking in neurons. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura K, Nemani VM, Azarbal F, Skibinski G, Levy JM, Egami K, Munishkina L, Zhang J, Gardner B, Wakabayashi J, Sesaki H, Cheng Y, Finkbeiner S, Nussbaum RL, Masliah E, Edwards RH. Direct membrane association drives mitochondrial fission by the Parkinson disease-associated protein alpha-synuclein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:20710–20726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.213538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.