Abstract

After a high-throughput screening campaign identified thioether 1 as an antagonist of the nuclear androgen receptor, a zone model was developed for structure–activity relationship (SAR) purposes and analogues were synthesized and evaluated in a cell-based luciferase assay. A novel thioether isostere, cyclopropane (1S,2R)-27, showed the desired increased potency and structural properties (stereospecific SAR response, absence of a readily oxidized sulfur atom, low molecular weight, reduced number of flexible bonds and polar surface area, and drug-likeness score) in the prostate-specific antigen luciferase assay in C4-2-PSA-rl cells to qualify as a new lead structure for prostate cancer drug development.

Keywords: Androgen receptor, CRPC, advanced prostate cancer, luciferase assay, isoxazoles, thioether isostere

The steroidal hormones testosterone and dihydrotestosterone are the major endogenous androgens that cause nuclear translocation and subsequent activation of androgen receptor (AR).1 In prostate cancer, AR shows a higher nuclear concentration in the presence of androgens,2,3 and androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) is one of the primary treatments.4 Unfortunately, even with ADT, almost all patients eventually progress to the stage of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC, formerly known as hormone-refractory prostate cancer), a fatal condition that makes prostate cancer the second most deadly cancer type in men in the U.S.5 Despite a high survival rate with early detection and treatment with surgery or radiation, prostate cancer is responsible for the death of 30,000 patients each year in the U.S.5,6

CRPC is postulated to arise through either adaption or selection of cancer cells in a low androgen environment7 as a result of the initial ADT.4,8 In the laboratory setting, studies of overexpression9 and knockdown10 of AR have shown that this receptor plays a key role in the progression of CRPC.11,12 Enzalutamide (MDV3100) and bicalutamide are AR antagonists that are currently used as treatments for CRPC and can extend the lifespan of patients for 3–5 months (Figure 1). Enzalutamide, in particular, attenuates nuclear translocation of AR but does not seem to reduce nuclear levels of AR in prostate cancer cells.13 Since these therapeutics are only partially effective, there is a definite need for new regimens that extend life expectation beyond several months.14 Unfortunately, there are no known therapies that decisively inhibit nuclear localized AR in CRPC cells.15−22 Herein, we investigate a novel series of small molecules identified by their ability to reduce the nuclear level of AR and, subsequently, AR activity.

Figure 1.

Structures of clinically used AR antagonists enzalutamide and bicalutamide.

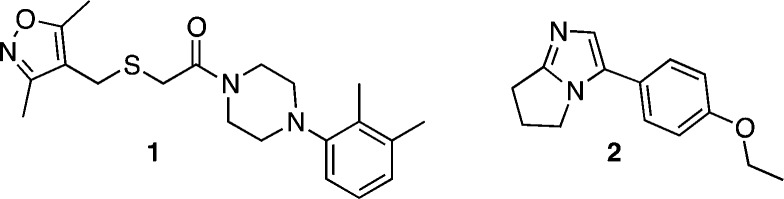

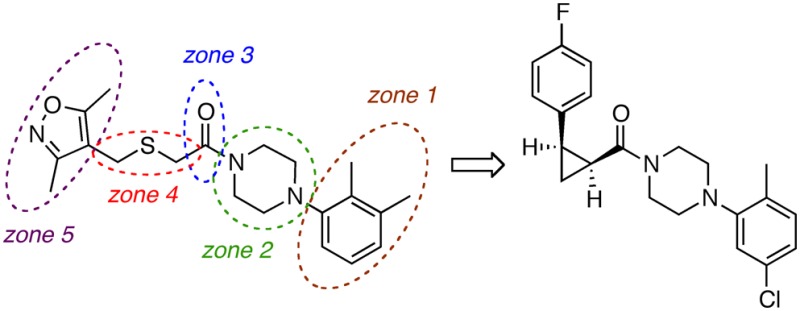

Prior to the onset of our medicinal chemistry efforts, a high-throughput screening (HTS) campaign for antagonists of AR nuclear localization identified compounds 1 and 2 that also reduced levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA), a key marker for CRPC, in a PSA luciferase reporter assay performed in CRPC cell lines (Figure 2).23 Both HTS hits demonstrated low micromolar potency with little to no cytotoxicity or activity in AR negative cell lines. Close structural analogues of 3-phenyl-6,7-dihydro-5-pyrrolo[1,2-a]imidazole (2) were previously found to have antifungal effects, which raised off-target concerns.24 In contrast, 2-((isoxazol-4-ylmethyl)thio)-1-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)ethanone (1) had not yet been biologically annotated, and this structural novelty led us to prioritize this scaffold over 2. In an effort to determine a structure–activity relationship and identify more potent antagonists of CRPC, we designed and synthesized analogues of 1 in a series of structural modifications of subunits 1–5 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

HTS hits that reduced PSA levels in a luciferase assay in CRPC cell lines.23

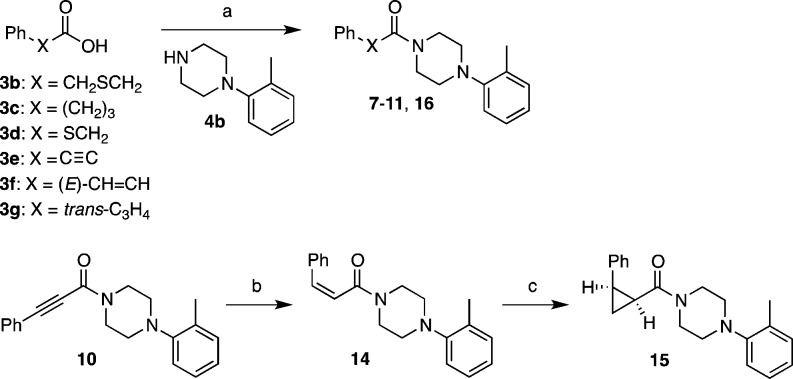

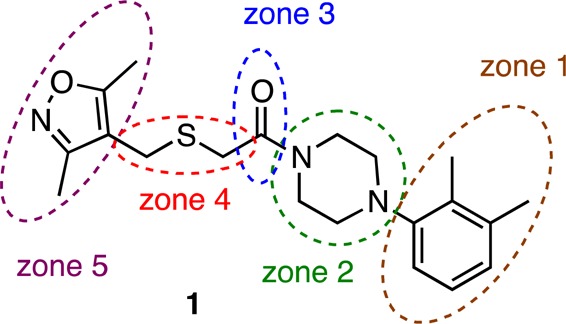

Figure 3.

Zones of planned structural modifications of 1.

Our goal was to probe five key moieties in compound 1: the benzene substitution pattern (zone 1), modifications at the piperazine (zone 2), carbonyl replacements (zone 3), a sulfur-atom exchange in the 3-atom linker and the use of less flexible linkers (zone 4), and variations of the 3,5-dimethylisoxazole (3,5-DMI) ring (zone 5) (Figure 3).

In the synthesis of zone 1–3 analogues, we used the amide bond as the lynchpin disconnection. Compounds 5a–h were synthesized directly from commercially available carboxylic acid 3a and N-arylated piperazines 4a–h under amide coupling conditions with T3P (Scheme 1 and Table 1).25 We also examined the diamine linker in zone 2 in more detail through the synthesis of analogues 5i–5m. For these target molecules, the requisite diamines 4i–m were prepared by a Buchwald–Hartwig cross-coupling of mono-Boc-protected diamines with bromoarenes.26,27 Reduction of amide 5b with lithium aluminum hydride led to diamine 6. For an initial set of zone 4 analogues, thioether 5b was also oxidized to sulfoxide 12 and sulfone 13 in good yields with sodium periodate and m-chloroperbenzoate, respectively (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of DMI-Containing Analogues 5, 6, 12, and 13.

Reagents and conditions: (a) T3P, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, overnight, 52–98%; (b) LiAlH4, dry THF, 0 °C, 1 h, 42%; (c) NaIO4, MeOH, H2O, rt, 15 h, 68%; (d) m-CPBA, CH2Cl2, rt, 15 h, 44%.

Table 1. Structures of Amine Building Blocks 4 and Analogues 5, 7–11, and 16 (Schemes 1 and 2).

Additional zone 4 and zone 5 analogues with a phenyl group in place of the isoxazole ring were obtained from carboxylic acids 3b–3g (Scheme 2 and Table 1). Coupling to piperazine 4b provided amides 7–11 and 16 in high yields. Alkynyl amide 10 was further hydrogenated to cis-alkene 14 using a Lindlar catalyst. The cis-cyclopropane 15 was prepared by a Simmons–Smith cyclopropanation of cis-alkene 14,28 whereas the trans-cyclopropane 16 was obtained by coupling of commercially available trans-2-phenylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid 3g with piperazine 4b.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Piperazines 7–11 and 14–16.

Reagents and conditions: (a) T3P, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, overnight, 62–96%; (b) Lindlar’s catalyst, quinoline, H2, EtOAc, quant.; (c) CrCl2, CH2ICl, THF, reflux, overnight, 57%.

Further modifications in zones 3–4 were accomplished by acylation of piperazine 4b with either 2-chloroacetyl chloride or chloromethanesulfonyl chloride to form the corresponding amide 17a or sulfonamide 17b in good yields (Scheme 3). SN2 reaction of 17a and 17b led to ether 18a, amine 18b, and thioether 18c. Starting with carboxylic acid 3a, urea 20a and carbamate 20b were obtained in moderate yields via a Curtius rearrangement and addition of the intermediate isocyanate 19 to amine 4b and alcohol 4n, respectively (Scheme 3).29

Scheme 3. Alkylation of 17a and 17b To Give Analogues 18a–18c and Conversion of Isocyanate 19 To Give Thioethers 20a/b.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 2-chloroacetyl chloride, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, overnight, 99%; (b) chloromethanesulfonyl chloride, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, overnight, 85%; (c) NaH, THF, rt, 1–2 d, 4–99%; (d) DPPA, Et3N, toluene, reflux, overnight, 17–65%.

A bridged bicyclic ring was introduced to add a strong conformational constraint in zone 2 (Scheme 4). Boc-protection of nortropinone hydrochloride 21 followed by enolization with NaHMDS and trapping of the enolate with N-phenyltriflimide provided vinyl triflate 22 in good yield. A Suzuki coupling was used to install the o-tolyl group, and the styrene double bond was reduced with Pd/C to afford 23 as a mixture of diastereomers. Without separation, this mixture was deprotected and acylated with α-chloroacetyl chloride. Finally, the chloride was displaced using thiol 25 and sodium hydride to afford the thioether. Diastereomers 26a and 26b were separated by chromatography on SiO2 to afford both analogues in modest yields.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Bridged Analogues 26a and 26b.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Boc2O, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt, overnight, 78%; (b) NaHMDS, PhNTf2, THF, −78 °C to rt, 4 h, 78%; (c) Pd(PPh3)4, LiCl, Na2CO3, (2-Me)PhB(OH)2, DME, H2O, 60 °C, 3 h, 78%; (d) H2, Pd/C, EtOH, rt, 14 h, 90%; (e) TFA, CH2Cl2, rt, 16 h, quant.; (f) 2-chloroacetyl chloride, Et3N, THF, rt, 22 h, 79%; (g) 25, NaH, THF, rt, 1 d, 30%.

The biological activity of analogs 5–16, 18, 20, and 26 was determined and compared to HTS hit 1 (EC50 7.3 μM) and enzalutamide (EC50 1.1 μM) using the Dual-Glo luciferase system (Promega, WI, USA) in the presence of 1 nM synthetic androgen R1881 in C4-2-PSA-rl cells, which were generated by stable cotransfection of C4-2 cells with a PSA promoter driven luciferase reporter vector (pPSA6.1) and a Renilla luciferase reporter vector as a control. Relative luciferase activity was calculated as the quotient of androgen-induced PSA-firefly/Renilla luciferase activity. Since PSA promoter activity correlates to AR transcriptional activity, inhibition of AR will result in decreased PSA-luciferase activity. EC50 values were calculated using graphpad prism, and data represent the mean and SD of 2–6 independent experiments (Table 2). To verify that these compounds did not have undesirable electrophilic properties, their stability was tested in the presence of thiols. Neither thiophenol in CDCl3 nor 2-mercaptoethanol in PBS resulted in any trapping products by 1H NMR and LCMS analysis.

Table 2. In Vitro Activity of Analogues in the PSA Luciferase Assay in C4-2-PSA-rl Cells.

| entry | compd | EC50 (μM) | entry | compd | EC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 7.3 ± 2.5c | 19 | 10 | 20.3 ± 11.6a |

| 2 | 5a | >25a | 20 | 11 | >25a |

| 3 | 5b | 14.5 ± 3.2b | 21 | 12 | >25b |

| 4 | 5c | >25a | 22 | 13 | 16.1 ± 3.3b |

| 5 | 5d | >25a | 23 | 14 | 12.7 ± 0.8a |

| 6 | 5e | 12.0 ± 1.6b | 24 | 15 | 2.9 ± 1.0b |

| 7 | 5f | 12.6 ± 7.7b | 25 | 16 | >25b |

| 8 | 5g | 11.1 ± 5.3b | 26 | 18a | >25b |

| 9 | 5h | >25a | 27 | 18b | >25b |

| 10 | 5i | 18.4 ± 9.2b | 28 | 18c | 7.2 ± 2.7c |

| 11 | 5j | 11.1 ± 3.3a | 29 | 20a | >25a |

| 12 | 5k | 3.1 ± 1.1a | 30 | 20b | >25c |

| 13 | 5l | 14.7 ± 4.4a | 31 | 26a | 7.7 ± 1.6b |

| 14 | 5m | 16.6 ± 4.8b | 32 | 26b | 7.9 ± 2.8a |

| 15 | 6 | 10.8 ± 5.7b | 33 | enzalutamide | 1.1 ± 0.5e |

| 16 | 7 | 13.7 ± 0.8b | 34 | 27 | 2.7 ± 1.1d |

| 17 | 8 | 14.4 ± 3.7b | 35 | (1S,2R)-27 | 1.7 + 0.2a |

| 18 | 9 | >25a | 36 | (1R,2S)-27 | 15.2 ± 3.3a |

Assay repeats. n = 2.

n = 3.

n = 4.

n = 5.

n = 6. For assay description and complete structural information, please see the Supporting Information and Table S1.

Simple modifications of the substituents on the benzene ring in zone 1 revealed that methyl groups in the 3- and 4-positions (5c, 5d) led to loss of activity, while the 2-methyl analogue 5b (EC50 14.5 μM) retained about half of the activity of the 2,3-dimethylated 1 (Table 2). Removal of the 2-methyl group in 5a deleted activity. In agreement with this trend in zone 1, the bulky 1-naphthyl substituent (5g) recovered activity (EC50 11.1 μM). Analogues with electron-withdrawing substituents at the benzene 2-position (2-NC, 5e, and 2-F, 5f) also maintained or slightly increased activity (EC50 12–13 μM); however, the electron-donating 2-methoxy substituted 5h was not tolerated and resulted in a complete loss of activity, possibly due to an increase in the pKa of the aniline and/or an unfavorable increase in the π-electron density of the aromatic ring.30 To potentially reduce the expected rapid metabolism of benzylic methyl groups by cytochrome P450 enzymes,31 we selected the minimally required substitution in zone 1, e.g., the 2-methyl group, for further structure–activity relationship (SAR) investigations.

The piperazine core (zone 2) was queried through substitutions with flexible as well as constrained acyclic and cyclic diamines. The flexible N,N′-dimethylethylenediamine linker in 5i (EC50 18.4 μM) and the 7-membered diazepane 5j (EC50 11.1 μM) both dropped off in activity. The dimethylated piperazines 5l and 5m (EC50 15–17 μM) were also less active than the initial hit. In contrast, the conformationally more highly constraint 2,6-dimethylpiperazine 5k was more active with an EC50 of 3.1 μM. Installment of an ethylene bridge and a carbon-linked (2-Me)Ph group decreased activity again since both diastereomers of the bicyclo[3.2.1] ring systems 26a and 26b showed an EC50 of 8 μM.

Reduction of amide 5b to amine 6 resulted in a 1.3-fold increase in activity to an EC50 of 10.8 μM. Sulfonamide 18c (EC50 7.2 μM) was as active as the initial hit 1, but urea 20a and carbamate 20b were inactive.

The replacement of the thioether linkage in zone 2 with an ether group abolished activity in 18a. Substituting the thioether with the N-methylated amine in 18b also abolished activity. In contrast, in an analogous system with a phenyl group in place of the isoxazole, both thioether 7 as well as the all-carbon chain containing 8 showed decreased yet consistent activity (EC50 ≈ 14 μM).

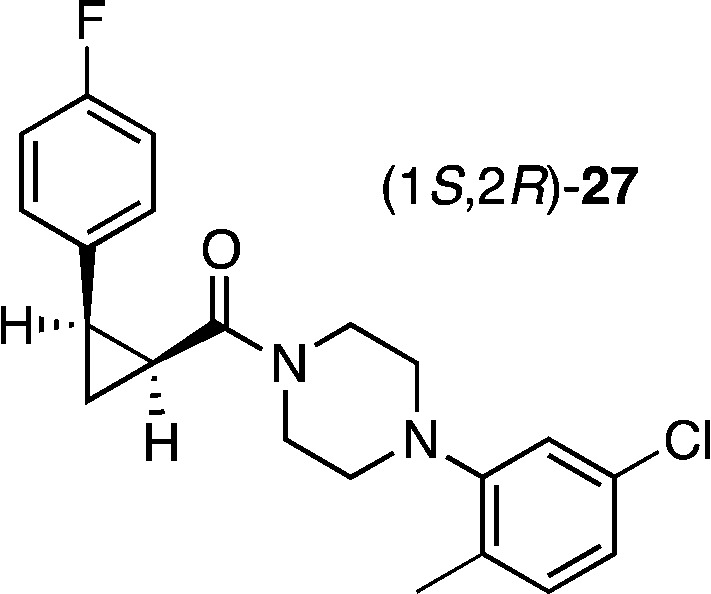

In order to verify that the biological effect in the thioether series was not a result of S-oxidation in the cellular assay, common products of thioether oxidation, i.e., sulfoxide 12 and sulfone 13, were tested. While sulfone 13 retained some activity (EC50 16.1 μM), sulfoxide 12 was inactive. Shortening the three-atom chain to afford the two-atom thioether-linked 9 also abolished activity. The rigidified alkyne 10 and the corresponding (E)-alkene 11 and its cyclopropane isostere 16 were also found to be essentially inactive. In contrast, we were pleasantly surprised to find that the (Z)-alkene 14 showed an EC50 of 12.7 μM and that the corresponding cis-fused cyclopropane isostere3215 was even more potent than analogue 1, showing an EC50 of 2.9 μM (Table 2). More significantly, chiral resolution of the bis-halogenated cyclopropane 27 (EC50 2.7 μM, entry 34) provided a more potent enantiomer (1S,2R)-27 (EC50 1.7 μM, entry 35) and the ca. 10-fold less potent (1R,2S)-27 (EC50 15.2 μM, entry 36), and supporting specific contact of this scaffold at a still to be defined AR binding site (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

More potent enantiomer of cyclopropane 27.

In summary, 35 analogues were synthesized, and the resulting SAR evaluated 5 zones of modification in the starting hit, compound 1. We discovered several attributes that proved essential for activity. Zone 1 modifications showed that the ortho-substituent on the phenyl ring was important for activity. In zone 2, the sterically encumbered 2,6-dimethylpiperazine proved superior to flexible, unsubstituted, and bridged analogues. In zone 3, a carbonyl group was not required, and a sulfonamide and even the reduced amine were well tolerated. In zone 4, thioether oxidation reduced activity, and only the cis-cyclopropane significantly improved the EC50. Limited substitutions were performed in zone 5, but in general, analogues with a phenyl group were equipotent with their 3,5-dimethylisoxazole congeners (see, for example, 7 vs 5b). The cis-cyclopropane (1S,2R)-27 was found to be substantially equipotent to the commercial AR antagonist, enzalutamide. Compound (1S,2R)-27 is of particular interest in comparison to 1 due to the isosteric replacement of the thioether linker with the metabolically more stable cyclopropane, a reduction of the topological polar surface area (TPSA) from 49.6 to 23.6 Å2, a reduction of the number of rotatable bonds from 3 to 2, and an improvement in the drug-likeness score from 6.3 to 8.0.33 Further modifications of lead structure 27 based on these SAR results as well as in vivo tumor xenograft data will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Department of Urology, University of Pittsburgh and the Johnson & Johnson Corporate Office of Science and Technology (COSAT) – University of Pittsburgh Translational Innovation Partnership Program. The authors thank Ms. Taber Lewis (University of Pittsburgh) for LCMS analyses, Dr. Marianne Sadar (University of British Columbia) for the PSA6.1--luc plasmid, and Dr. Leland W. K. Chung (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center) for the C4-2 cell line.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- AR

androgen receptor

- 3,5-DMI

3,5-dimethylisoxazole

- CRPC

castration-resistant prostate cancer

- HTS

high-throughput screen

- MW

molecular weight

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- SD

standard deviation

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00186.

Methods for all assays, cell cultures, treatment conditions, and compound synthesis (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bruchovsky N.; Wilson J. D. Discovery of the role of dihydrotestosterone in androgen action. Steroids 1999, 64, 753–759. 10.1016/S0039-128X(99)00054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins C.; Hodges C. V. Studies on prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Res. 1941, 1, 293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linja M. J.; Visakorpi T. Alterations of androgen receptor in prostate cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 92, 255–264. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong Y.; Goldstein A. S. Adaptation or selection-mechanisms of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2013, 10, 90–98. 10.1038/nrurol.2012.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R.; Ma J.; Zou Z.; Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2014, 64, 9–29. 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Prostate Cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html.

- Waltering K. K.; Urbanucci A.; Visakorpi T. Androgen receptor (AR) aberrations in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 360, 38–43. 10.1016/j.mce.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haendler B.; Cleve A. Recent developments in antiandrogens and selective androgen receptor modulators. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 352, 79–91. 10.1016/j.mce.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. D.; Welsbie D. S.; Tran C.; Baek S. H.; Chen R.; Vessella R.; Rosenfeld M. G.; Sawyers C. L. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 33–39. 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegarra-Moro O. L.; Schmidt L. J.; Huang H.; Tindall D. J. Disruption of androgen receptor function inhibits proliferation of androgen-refractory prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 1008–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory C. W.; Johnson R. T.; Mohler J. L.; French F. S.; Wilson E. M. Androgen receptor stabilization in recurrent prostate cancer is associated with hypersensitivity to low androgen. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2892–2898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathkopf D.; Scher H. I. Androgen receptor antagonists in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer J. 2013, 19, 43–49. 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318282635a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran C.; Ouk S.; Clegg N. J.; Chen Y.; Watson P. A.; Arora V.; Wongvipat J.; Smith-Jones P. M.; Yoo D.; Kwon A.; Wasielewska T.; Welsbie D.; Chen C. D.; Higano C. S.; Beer T. M.; Hung D. T.; Scher H. I.; Jung M. E.; Sawyers C. L. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science 2009, 324, 787–790. 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarese C.; Santoni M.; Brunelli M.; Buti S.; Modena A.; Nabissi M.; Artibani W.; Martignoni G.; Montironi R.; Tortora G.; Massari F. AR-V7 and prostate cancer: The watershed for treatment selection?. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 43, 27–35. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran F.; Xing H.; Liu Y.; Zhang D.; Li P.; Zhao G. Recent developments in androgen receptor antagonists. Arch. Pharm. 2015, 348, 757–775. 10.1002/ardp.201500187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S.; Kobayashi H.; Kaku T.; Aikawa K.; Hara T.; Yamaoka M.; Kanzaki N.; Hasuoka A.; Baba A.; Ito M. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 3-aryl-3-hydroxy-1-phenylpyrrolidine derivatives as novel androgen receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 70–83. 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balog A.; Rampulla R.; Martin G. S.; Krystek S. R.; Attar R.; Dell-John J.; Dimarco J. D.; Fairfax D.; Gougoutas J.; Holst C. L.; Nation A.; Rizzo C.; Rossiter L. M.; Schweizer L.; Shan W.; Spergel S.; Spires T.; Cornelius G.; Gottardis M.; Trainor G.; Vite G. D.; Salvati M. E. Discovery of BMS-641988, a novel androgen receptor antagonist for the treatment of prostate cancer. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 908–912. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury R. H.; Acton D. G.; Broadbent N. L.; Brooks A. N.; Carr G. R.; Hatter G.; Hayter B. R.; Hill K. J.; Howe N. J.; Jones R. D. O.; Jude D.; Lamont S. G.; Loddick S. A.; Mcfarland H. L.; Parveen Z.; Rabow A. A.; Sharma-Singh G.; Stratton N. C.; Thomason A. G.; Trueman D.; Walker G. E.; Wells S. L.; Wilson J.; Wood J. M. Discovery of AZD3514, a small-molecule androgen receptor downregulator for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 1945–1948. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini A.; Tesei A.; Ferroni C.; Paganelli G.; Zamagni A.; Carloni S.; Di Donato M.; Castoria G.; Leonetti C.; Porru M.; De Cesare M.; Zaffaroni N.; Beretta G. L.; Del Rio A.; Varchi G. A new avenue toward androgen receptor pan-antagonists: C2 Sterically hindered substitution of hydroxypropanamides. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 7263–7279. 10.1021/jm5005122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njar V. C. O.; Brodie A. M. H. Discovery and development of galeterone (TOK-001 or VN/124–1) for the treatment of all stages of prostate cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 2077–2087. 10.1021/jm501239f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg N. J.; Wongvipat J.; Joseph J. D.; Tran C.; Ouk S.; Dilhas A.; Chen Y.; Grillot K.; Bischoff E. D.; Cai L.; Aparicio A.; Dorow S.; Arora V.; Shao G.; Qian J.; Zhao H.; Yang G.; Cao C.; Sensintaffar J.; Wasielewska T.; Herbert M. R.; Bonnefous C.; Darimont B.; Scher H. I.; Smith-Jones P.; Klang M.; Smith N. D.; De Stanchina E.; Wu N.; Ouerfelli O.; Rix P. J.; Heyman R. A.; Jung M. E.; Sawyers C. L.; Hager J. H. ARN-509: A novel antiandrogen for prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 1494–1503. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen A.-M.; Riikonen R.; Oksala R.; Ravanti L.; Aho E.; Wohlfahrt G.; Nykanen P. S.; Tormakangas O. P.; Kallio P. J.; Palvimo J. J. Discovery of ODM-201, a new-generation androgen receptor inhibitor targeting resistance mechanisms to androgen signaling-directed prostate cancer therapies. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12007. 10.1038/srep12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston P. A.; Nguyen M. M.; Dar J. A.; Ai J.; Wang Y.; Masoodi K. Z.; Shun T.; Shinde S.; Camaro D. P.; Hua Y.; Huryn D. M.; Wilson G. M.; Lazo J. S.; Nelson J. B.; Wipf P.; Wang Z. Development and implementation of a high-throughput high-content screening assay to identify inhibitors of androgen receptor nuclear localization in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2016, 14, 226–239. 10.1089/adt.2016.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demchenko A. M.; Sinchenko V. G.; Prodanchuk N. G.; Kovtunenko V. A.; Patratii V. K.; Tyltin A. K.; Babichev F. S. Synthesis and antimycotic activity of 3-aryl-6,7-dihydro-5H-pyrrolo[1,2-a]imidazoles. Pharm. Chem. J. 1987, 21, 789–791. 10.1007/BF01151185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanatha T. M.; Panguluri N. R.; Sureshbabu V. V. Propanephosphonic acid anhydride (T3P)—A benign reagent for diverse applications inclusive of large-scale synthesis. Synthesis 2013, 45, 1569–1601. 10.1055/s-0033-1338989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello-Sanchez N.; Jean L.; Maddaluno J.; Lasne M.-C.; Rouden J. Palladium-mediated N-arylation of heterocyclic diamines: insights into the origin of an unusual chemoselectivity. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 2030–2039. 10.1021/jo062301i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen S. B.; Bang-Andersen B.; Johansen T. N.; Jørgensen M. Palladium-catalyzed monoamination of dihalogenated benzenes. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 2938–2950. 10.1016/j.tet.2008.01.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Concellón J. M.; Rodríguez-Solla H.; Méjica C.; Blanco E. G. Stereospecific cyclopropanation of highly substituted C–C double bonds promoted by CrCl2. Stereoselective synthesis of cyclopropanecarboxamides and cyclopropyl ketones. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2981–2984. 10.1021/ol070896d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogen S. L.; Pan W.; Ruan S.; Chen K. X.; Arasappan A.; Venkatraman S.; Nair L. G.; Sannigrahi M.; Bennett F.. Inhibitors of hepatitis C virus NS3 protease. WO 2005/085275.

- Morgenthaler M.; Schweizer E.; Hoffmann-Roder A.; Benini F.; Martin R. E.; Jaeschke G.; Wagner B.; Fischer H.; Bendels S.; Zimmerli D.; Schneider J.; Diederich F.; Kansy M.; Muller K. Predicting and tuning physicochemical properties in lead optimization: Amine basicities. ChemMedChem 2007, 2, 1100–1115. 10.1002/cmdc.200700059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Montellano P. R. Hydrocarbon hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2010, 2, 932–948. 10.1021/cr9002193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins C. D.; Schmitz J. C.; Chu E.; Wipf P. Total synthesis of (−)-CP2-disorazole C1. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4088–4091. 10.1021/ol2015994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug-relevant properties were calculated with Instant JChem 15.8.31.0 (ChemAxon; http://www.chemaxon.com) and OSIRIS Property Explorer (http://www.organic-chemistry.org/prog/peo/).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.