Significance

Large-scale biological network analyses often use concepts used in social networks analysis (e.g. finding “communities,” “hubs,” etc.). However, mathematically advanced engineering concepts have only been applied to analyze small and well-characterized networks so far in biology. Here, we applied a sophisticated engineering tool, from control theory, to analyze a large-scale directed human protein–protein interaction network. Our analysis revealed that the proteins that are indispensable, from a network controllability perspective, are also commonly targeted by disease-causing mutations and human viruses or have been identified as drug targets. Furthermore, we used the controllability analysis to prioritize novel cancer genes from cancer genomic datasets. Altogether, we demonstrated an application of network controllability analysis to identify new disease genes and drug targets.

Keywords: network biology, controllability, protein–protein interaction network, disease genes, drug targets

Abstract

The protein–protein interaction (PPI) network is crucial for cellular information processing and decision-making. With suitable inputs, PPI networks drive the cells to diverse functional outcomes such as cell proliferation or cell death. Here, we characterize the structural controllability of a large directed human PPI network comprising 6,339 proteins and 34,813 interactions. This network allows us to classify proteins as “indispensable,” “neutral,” or “dispensable,” which correlates to increasing, no effect, or decreasing the number of driver nodes in the network upon removal of that protein. We find that 21% of the proteins in the PPI network are indispensable. Interestingly, these indispensable proteins are the primary targets of disease-causing mutations, human viruses, and drugs, suggesting that altering a network’s control property is critical for the transition between healthy and disease states. Furthermore, analyzing copy number alterations data from 1,547 cancer patients reveals that 56 genes that are frequently amplified or deleted in nine different cancers are indispensable. Among the 56 genes, 46 of them have not been previously associated with cancer. This suggests that controllability analysis is very useful in identifying novel disease genes and potential drug targets.

The need to control engineered systems has resulted in a mathematically rich set of tools that are widely applied in the design of electric circuits, manufacturing processes, communication systems, aircraft, spacecraft, and robots (1–3). Control theory deals with the design and stability analysis of dynamic systems that receive information via inputs and have outputs available for measurement. Issues of control and regulation are central to the study of biological systems (4, 5), which sense and process both external and internal cues using a network of interacting molecules (6). The dynamic regulation of this molecular network in turn drives the system to various functional states, such as triggering cell proliferation or inducing apoptosis. This feature of specific input signals driving networks from an initial state to a specific functional state suggests that the need to control a biological system plays a potentially important role in the evolution of molecular interaction networks. Note that the term “state” is also used in a control context where the “state space” of a control system is the space of values the “state variables” can attain. For a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, the state variables are the specific protein concentrations and the state space is all positive real numbers of dimension equal to the total number of proteins in the PPI network.

According to control theory, a dynamic system is controllable if, with a suitable choice of inputs, the system can be driven from any initial state to any desired final state in finite time (2, 7). Previous studies have shown that network components exhibit properties of control systems such as proportional action, feedback control, and feed-forward control (8–12). However, the main challenges that hinder systematic controllability analysis of biological networks are the availability of large-scale biologically relevant networks and efficient tools to analyze their controllability. To address these issues, two resources were integrated in this work: (i) a directed human PPI network (13); and (ii) an analytical framework to characterize the structural controllability of directed weighted networks (14). The directed human PPI network represents a global snapshot of the information flow in cell signaling. For a given weighted and directed network associated with linear time-invariant dynamics, the analytical framework identifies a minimum set of driver nodes, whose control is sufficient to fully control the dynamics of the whole network (14, 15).

In this work, we classified the proteins (nodes) as “indispensable,” “neutral,” or “dispensable,” based on the change of the minimum number of driver nodes needed to control the PPI network when a specific protein (node) is absent. In addition, we analyzed the role of different node types in the context of human diseases. Using known examples of disease-causing mutations, virus targets, and drug targets, we identified indispensable nodes that are key players in mediating the transition between healthy and disease states. Our study illustrates the potential application of network controllability analysis as a powerful tool to identify new disease genes.

Results

Characterizing the Controllability of the Directed PPI Network.

We applied linear control tools to access local controllability of PPI networks whose dynamics are inherently nonlinear. The experimentally obtained network, however, can be assumed to capture linear affects around homeostasis. Furthermore, given that the tools developed in ref. 14 are for linear dynamics, we are careful to only assume that we can ascertain local controllability around homeostasis. Controllability henceforth referred to local controllability (see SI Text for details).

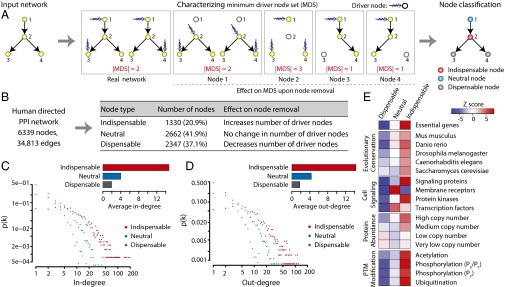

The directed human PPI network consists of 6,339 proteins (nodes) and 34,813 directed edges, where the edge direction corresponds to the hierarchy of signal flow between the interacting proteins and the edge weight corresponds to the confidence of the predicted direction. We applied structural controllability theory to identify a minimum set of driver nodes (i.e., nodes through which we can achieve control of the whole network). Note that the identified minimum driver node set (MDS) is not unique, but its size, denoted as ND, is uniquely determined by the network topology. We found that the MDS of the directed human PPI network contains 36% of nodes. We also classified the nodes as indispensable, neutral, or dispensable, based on the change of ND upon their removal. A node is (i) indispensable if removing it increases ND (e.g., node 2 in Fig. 1A), (ii) neutral if its removal has no effect on ND (e.g., node 1 in Fig. 1A), and (iii) dispensable if its removal reduces ND (e.g., nodes 3 and 4 in Fig. 1A). In the directed human PPI network, 21% of nodes are indispensable, 42% are neutral, and the remaining 37% are dispensable (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, we found that all of the three node types have a heterogeneous degree distribution, and indispensable nodes tend to have higher in- and out-degrees compared with neutral and dispensable nodes (Fig. 1 B and C). Similarly, indispensable nodes are associated with more PubMed records (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) and Gene Ontology (16) term annotation than neutral and dispensable nodes (Fig. S1 A and B). However, the correlation between the node-degree and the literature bias is weak (correlation coefficient of 0.37 and 0.41 for in- and out-degree, respectively), suggesting that the higher degree of indispensable nodes is not explained by the literature bias alone (Fig. S1 C and D).

Fig. 1.

Characterizing the controllability of human directed PPI network. (A) Schematic representation of the node classification using controllability framework. (B) Identification of indispensable, neutral, and dispensable nodes in human directed PPI network. (C) In-degree distribution and average in-degree for three different node types. (D) Out-degree distribution and average out-degree for three different node types. (E) Distinct enrichment profiles of indispensable, neutral, and dispensable nodes in the context of essential genes, evolutionary conservation, cell signaling, protein abundance, and PTMs.

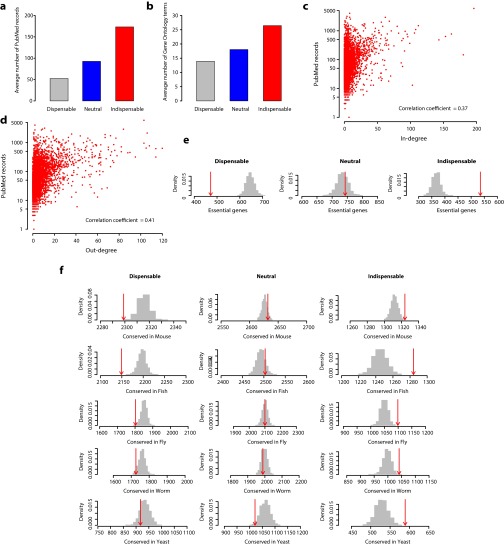

Fig. S1.

(A and B) Literature and annotation bias for the three node types. Bar plots show average PubMed records associated (A) and Gene Ontology terms annotated (B) for each node type. (C and D) Correlation of node degree vs. literature bias. The plots show the correlation of in-degree (C) and out-degree (D) to the number of PubMed records associated with each node in the entire network. (E) Enrichment analysis of essential genes. Numbers of essential genes overlapping with dispensable, neutral, and indispensable nodes are shown in red arrows. The essential genes are compiled from the Database of Essential Genes (DEG) (tubic.tju.edu.cn/deg) (50) and Online GEne Essentiality database (OGEE) (ogeedb.embl.de) (51). Numbers of essential genes overlapping with size-controlled random sets are shown in gray bars. (F) Enrichment analysis of conserved genes. Numbers of genes conserved in Mus musculus (mouse), Danio rerio (fish), Drosophila melanogaster (fly), Caenorhabditis elegans (worm), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) are shown in red arrows, and their respective size-controlled random set distributions are shown in gray bars. The ortholog mapping was performed using the Drosophila RNAi Screening Center (DRSC) Integrative Ortholog Prediction Tool (DIOPT) (www.flyrnai.org/DIOPT) (52).

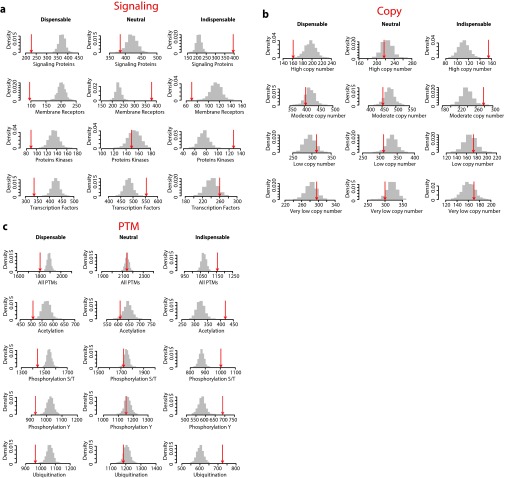

We characterized indispensable, neutral, and dispensable nodes in the context of essentiality, evolutionary conservation, and regulation at the level of translational and posttranslational modifications (PTMs). Our gene essentiality analysis indicated that indispensable nodes are enriched in essential genes, whereas essential genes are underrepresented among dispensable nodes (Fig. 1E, Fig. S1E, and Dataset S1). Furthermore, indispensable nodes are evolutionarily conserved from human to yeast compared with the other two node types (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1F). Next, we analyzed the different node types in the context of cell signaling, which is at the core of cellular information processing. In general, known signaling proteins are enriched as indispensable nodes. However, dissecting different functional classes within signaling proteins reveals that kinases are enriched as indispensable nodes whereas membrane receptors and transcription factors are enriched as neutral nodes (Fig. 1E and Fig. S2A). Analysis of the protein steady-state abundance in cell lines, as a measure of translational regulation, reveals that indispensable nodes are enriched as high copy number proteins, whereas low-copy number proteins show moderate enrichments for both indispensable and dispensable nodes (Fig. 1E and Fig. S2B). Similarly, indispensable nodes are highly regulated through PTM, including acetylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation (pS/pT and pY) (Fig. 1E and Fig. S2C). Altogether, our enrichment analyses revealed distinct functional and regulatory roles for indispensable, neutral, and dispensable nodes.

Fig. S2.

(A) Enrichment analysis of signaling proteins. Numbers of nodes overlapping with signaling proteins (annotated with signaling pathways in Cell Signaling Technology database www.cellsignal.com/common/content/content.jsp?id=science-pathways) (53), receptors (54), protein kinases (55, 56) (kinase.com/kinbase/index.html), and transcription factors (57) are shown in red arrows and, their respective size-controlled random set distributions in gray bars. (B) Enrichment analysis of protein abundance. Numbers of nodes overlapping with high copy numbers (>100,000 copies) (A), moderate copy numbers (5000–100,000 copies), low copy numbers (500–5,000 copies) (C), and very low copy numbers (<500 copies) are shown in red arrows, and their respective size-controlled random set distributions in gray bars. The copy number dataset was obtained from Beck et el. (58). (C) Enrichment analysis of protein PTMs. Numbers of nodes overlapping with any PTM [Acetylation, Tyrosine Phosphorylation (Phosphorylation Y), Serine/Threonine Phosphorylation (S/T), or Ubiquitination], Acetylation, Tyrosine Phosphorylation, Serine/Threonine Phosphorylation, and Ubiquitination datasets are shown in red arrows and their respective size-controlled random set distributions in gray bars. The PTM dataset was obtained from Woodsmith et al. (59).

Understanding Healthy to Disease State Transition Using Network Controllability.

We analyzed the node classification in the context of driving the system from healthy to disease condition and vice versa. Specifically, we analyzed the impact of three different transitions: (i) healthy to disease transition induced by mutations or other genetic alterations; (ii) healthy to infectious transition induced by human viruses; and (iii) disease to healthy transition induced by drugs or small molecules. Note that our goal is to determine whether specific node types (indispensable, neutral, or dispensable) are enriched for (i) disease-causing mutations, (ii) targets of human viruses, and (iii) drug targets.

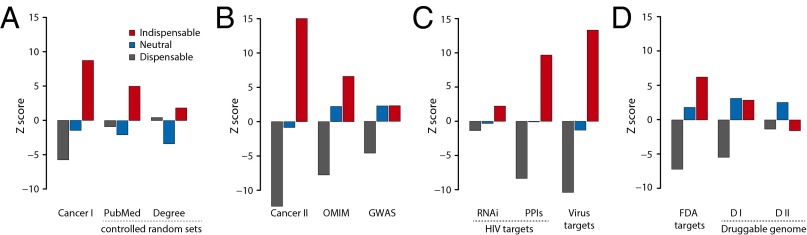

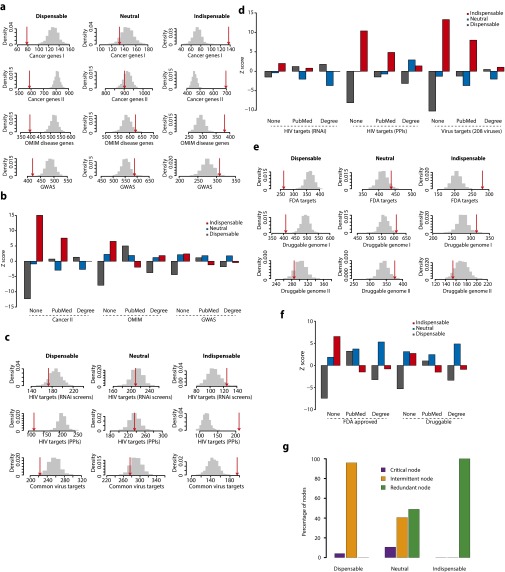

First, we analyzed 445 genes annotated by the Sanger Center as causally implicated in oncogenesis (Cancer Gene Census; cancer.sanger.ac.uk/census) (17). Interestingly, we found that indispensable nodes are highly enriched in cancer genes, whereas neutral nodes showed no enrichment and dispensable nodes are underrepresented (Fig. 2A, Cancer I; Fig. S3A; and Dataset S2). To ensure that the observed enrichment of indispensable nodes is not attributable to the literature and degree bias, we repeated our analysis using literature- and degree-controlled random sets (SI Text). After adjusting for literature and degree bias (Fig. 2A, PubMed and Degree; and Dataset S2), indispensable nodes remain significantly enriched as cancer genes. Note that for enrichment analysis below, the degree- and literature-controlled enrichments results were shown in Fig. S3B. To further substantiate that indispensable nodes are enriched as cancer genes, we analyzed 3,164 genes predicted as cancer related genes (18) and observed a similar enrichment for indispensable nodes (Fig. 2B, Cancer II; and Fig. S3A).

Fig. 2.

Characterizing network controllability in transition from healthy to disease state. (A) Bar graph showing the enrichment results (z scores) of cancer genes compared with the random sets (Cancer I, cancer gene census) and the random sets controlled for literature (PubMed) or degree (Degree) bias. In the case of degree- or literature-controlled random sets, the random sets are sampled such that the average degree or average PubMed records of random sets matches the average of node type N. (B) Results from enrichment analysis of dataset corresponding to extended list of cancer genes (Cancer II), other human diseases (OMIM), and GWAS. (C) Results from enrichment analysis of the targets of HIV identified using RNAi screens (RNAi) and PPI networks (PPIs) and targets of other human virus (208 viruses). (D) Enrichment results from targets of FDA-approved drugs and druggable genome. DI, druggable genome; DII, druggable genome excluding FDA-approved targets.

Fig. S3.

(A) Enrichment analysis of disease genes. Numbers of nodes overlapping with genes causally associated with cancer (Cancer genes I, cancer gene census) (Cancer Gene Census; cancer.sanger.ac.uk/census) (17) and a list of predicted cancer genes (Cancer genes II, extended list of cancer genes) (18), annotated as disease genes in the OMIM database (omim.org) and associated with disease in GWAS (www.genome.gov/gwastudies), are shown in red arrows, and their respective size-controlled random set distributions in gray bars. (B) Enrichment analysis of disease genes using literature- and degree-controlled random sets. In the case of degree- or literature-controlled random sets, the random sets are sampled such that the average degree or average PubMed records of random sets matches the average of node type N. (C) Enrichment analysis of virus targets. Numbers of nodes overlapping with genes identified to have an adverse effect on HIV-1 replication when knocked down (RNAi screens) (21–24), human proteins that directly interact with HIV proteins (HIV targets PPI) (26, 27), and human proteins that are known to physically interact with proteins from 208 viruses (common virus targets) (26–29) are shown in red arrows, and their respective size-controlled random set distributions in gray bars. (D) Enrichment analysis of virus targets using literature- and degree-controlled random sets. Random sets are generated as explained in B. (E) Enrichment analysis of drug targets. Numbers of nodes overlapping with proteins that are targeted by FDA-approved drugs (31), proteins with domains or folds that could bind to drug-like molecules (druggable genome I) (32), and a subset of druggable genome I excluding the FDA-approved drug targets (druggable genome II) are shown in red arrows, and their respective size-controlled random set distributions in gray bars. (F) Enrichment analysis of drug targets using literature- and degree-controlled random sets. Random sets are generated as explained in B. (G) Characterizing indispensable, neutral, and dispensable nodes based on their roles as driver nodes. The recently developed approach is used to classify a node as critical, intermittent, or redundant if it acts as a driver node in all, some, or none of the control configurations, respectively (33). The bar graph compares the indispensable, neutral, and dispensable nodes against the critical, intermittent, and redundant node classification.

Next, we analyzed 1,403 genes annotated by Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) (omim.org) as causal genes for various genetic diseases, aiming to test whether the perturbation of indispensable nodes is a specific feature of cancer or a general feature of human diseases. Our analysis showed that the perturbation of indispensable nodes is a common feature of human diseases (Fig. 2B, OMIM; and Fig. S3A). Interestingly, however, our analysis of disease genes identified from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (www.genome.gov/gwastudies) (19) revealed poor enrichment for indispensable nodes (Fig. 2B, GWAS; and Fig. S3A), most likely reflecting the fact that GWAS identify genomic regions but not specific coding genes that cause the disease (20). Because indispensable nodes are enriched for causal mutations (Fig. 2 A and B), our resource could help identify causal genes from GWAS.

We also characterized the network controllability in the context of host–parasite interactions, specifically human–virus interactions. Upon infection, viruses control the host cellular network to use the host resources to replicate and to evade the host immune response. Here, we analyzed the node types targeted by human viruses to drive the network from a healthy state to an infectious state. First, we analyzed the targets of HIV, a member of the lentivirus family that causes AIDS. Putative human genes, identified to have an effect on HIV-1 replication from large-scale functional genomic screens (data compiled from four RNAi datasets) (21–24) tend to be indispensable nodes (Fig. 2C, RNAi; and Fig. S3C). However, we did not detect a significant enrichment—most likely reflecting the quality of the HIV RNAi screens (25). To analyze direct targets of HIV, we compiled the HIV–human interactome (from recent literature and PPI databases) (26, 27), finding that indispensable nodes are enriched for physical interactions with HIV proteins (Fig. 2C, PPIs; and Fig. S3C). Analysis of 208 different human–virus networks (26–29) reveals that human viruses commonly target indispensable nodes to control the host network (Fig. 2C, Virus targets; and Fig. S3C). We noticed that after adjusting for literature bias indispensable nodes remain as viral targets, whereas adjusting for degree bias shows only weak enrichment (Fig. S3D). This finding is in agreement with the previous observations that viruses tend to target hubs (30).

Finally, we characterized the network controllability in the context of driving the system from disease to healthy state. Specifically, we analyzed the node types that are targeted by the drugs/small molecules (Fig. 2D). By analyzing the targets of drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (31), we found that indispensable nodes are enriched for drug targets (Fig. 2D, FDA targets; and Fig. S3 E and F). Extending the analysis to the list of proteins that are annotated as druggable (32), i.e., a presence of protein folds that favor interactions with drug-like chemical compounds, showed that the druggable genome list is not significantly enriched for indispensable nodes (Fig. 2D, D I; and Fig. S3E). Interestingly, analyzing the druggable genome list by excluding FDA-approved drug targets showed underrepresentation of indispensable nodes (Fig. 2D, D I; and Fig. S3E). This finding suggests a potential application of our analysis to redefine the druggable genome based on the network controllability.

All of the above analyses of disease mutations, viruses, and drugs consistently showed that indispensable nodes are preferred targets. We also analyzed how often indispensable nodes act as driver nodes by using a recently developed approach to identify the role of each node as drivers in the MDSs (33). We found that 378 nodes appear in all MDSs (i.e., they play roles in all of the control configurations), 3,330 nodes are in some but not all MDSs (i.e., they play roles in some control configurations but the network can still be controlled without directly controlling them), and 2,631 nodes do not belong to any MDS (i.e., they play no roles in control) (Dataset S1) (33). Interestingly, we found that indispensable nodes are never driver nodes in any MDS (Fig. S3G and Dataset S1). This fact can actually be rigorously proven (SI Text). Moreover, perturbing indispensable nodes increases the number of driver nodes to control, suggesting that, from a controllability perspective, these nodes are fragile points in the network.

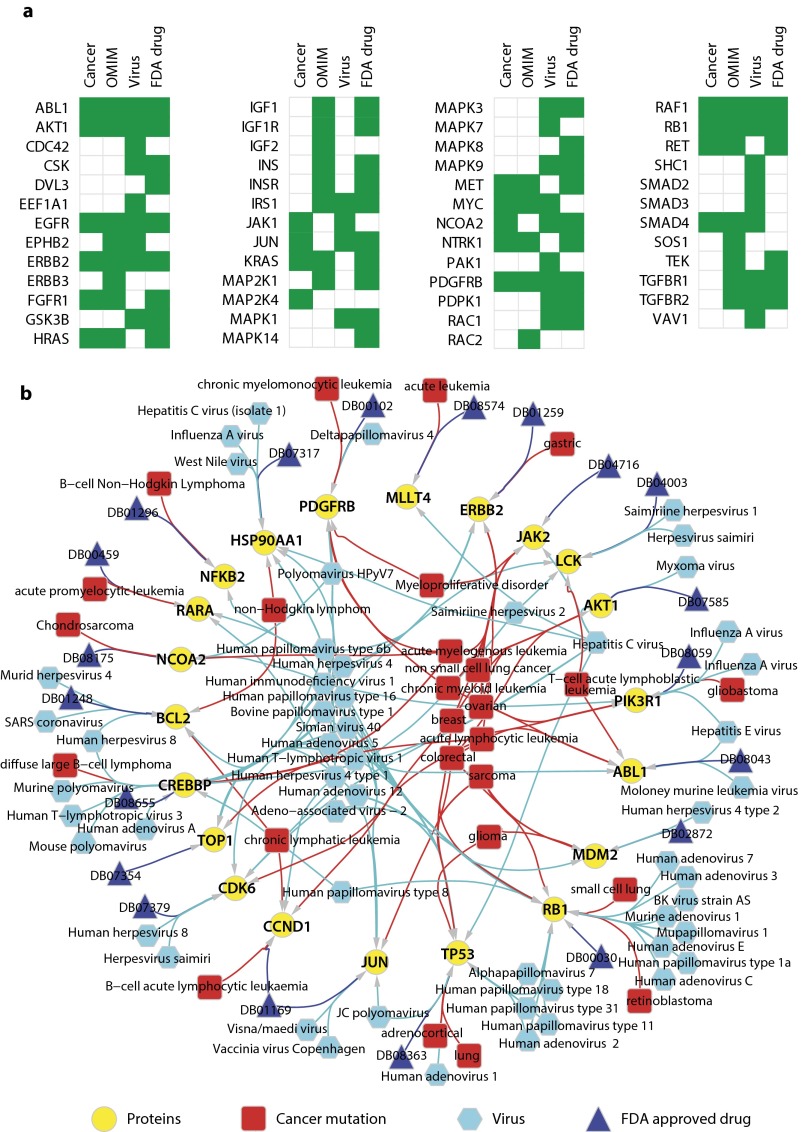

We further analyzed indispensable nodes in specific signaling pathways such as receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling pathways, which are commonly perturbed in cancer (34). Strikingly, 67 out of 170 RTK pathway members are indispensable nodes (P < 0.0001), including 51 indispensable nodes targeted by disease mutations, viruses, or drugs (Fig. S4A and Dataset S2). Furthermore, we identified 21 indispensable nodes from different signaling pathways that are shared targets of cancer mutations, viruses, as well as drugs (Fig. S4B and Dataset S2).

Fig. S4.

(A) Members of receptor tyrosine signaling pathways that are predicted as indispensable nodes and targeted by cancer mutations, OMIM disease, viruses, or FDA-approved drugs. RTK pathway members are as defined by the SignaLink database (60). (B) Indispensable nodes that are targeted by all three inputs (cancer mutation, viruses, and drugs). The labels of FDA drug nodes correspond to DrugBank IDs. The network was generated using Cytoscape (61).

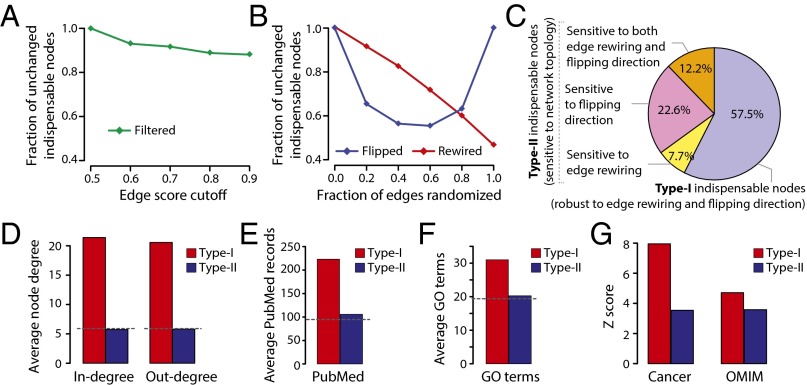

Robustness of Indispensable Node Classification.

The false-positive and false-negative interactions are major concerns in PPI networks, especially the false negatives because the current networks are vastly incomplete (35). Hence, we systematically analyzed the robustness of node classification with respect to adding or removing interactions. Specifically, we analyzed the indispensable node classification as a function of removing edges (or network filtering). The network filtering is achieved by using a confidence score assigned to edge directions, where the most stringent filtering resulted in smaller high-confidence–directed networks (20,151 edges and 5,317 nodes). We analyzed the controllability of filtered networks and compared them to the original network. The results show that 90% of the indispensable nodes in the stringent filtered network are indispensable in the original network (Fig. 3A, Fig. S5 A and B, and Dataset S3), suggesting that the indispensable node classification is robust with respect to adding or removing edges in the network.

Fig. 3.

Perturbation of network connectivity reveals two subtypes of indispensable nodes (type-I and type-II). (A) Plot showing the fraction of indispensable nodes in filtered networks that overlaps with the real network. The network filtering achieved using edge confidence score. (B) Fraction of indispensable nodes in rewired or direction-flipped overlap with the real network. (C) Identification of type-I and type-II indispensable nodes. The average node degree (D), PubMed record association (E), and Gene Ontology (GO) term annotations (F) for type-I and type-II indispensable nodes. (G) Enrichment of type-I and type-II indispensable nodes as cancer genes and OMIM disease genes.

Fig. S5.

(A and B) Robustness of node classification. (A) The fraction of indispensable, neutral, and dispensable nodes is plotted as a function of edge filtering (filtering using edge score). (B) The fraction of nodes in the filtered network sharing the same node classification as the real network (unchanged annotation) is plotted as a function of edge filtering. (C–F) Analysis of node classification in perturbed networks. (C) The fraction of indispensable, neutral, and dispensable nodes is plotted as a function of fraction of edges rewired. (D) The fraction of nodes in the rewired network sharing the same node classification as the real network (unchanged annotation) is plotted as a function of edge rewired. (E) Same as C, but the x axis corresponds to a fraction of flipped-edge directions. (F) Same as D, but the x axis corresponds to a fraction of flipped-edge directions. (G) Comparison of network properties of type-I and type-II indispensable nodes. The network betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, clustering coefficient, and neighborhood connectivity values are calculated using the NetworkAnalyzer Cytoscape plugin (62). The gray dotted line shows the average value of the network.

Next, we analyzed the controllability of networks with perturbations (e.g., edge rewiring or edge-direction flipping). In the case of random rewiring, up to 100% of the edges are rewired (node degrees are preserved), and in the case of direction-flipped networks, up to 100% of the edge directions are reversed. We observed that up to 50% of indispensable nodes in the rewired or direction-flipped network do not agree with the original annotation, showing that indispensability is highly sensitive to the connectivity pattern and edge direction (Fig. 3B, Fig. S5 C–F, and Dataset S3). Comparing indispensable nodes of the real network to that of the rewired (100% rewiring) and flipped (40% flipping) networks revealed two subtypes (type-I and type-II) of indispensable nodes (Fig. 3C and Dataset S3). If a node’s indispensability is robust to rewiring or flipping, then we call it a type-I node; if the node’s indispensability is sensitive to rewiring or flipping, then we refer to them as type-II nodes. We found that 57% of indispensable nodes are type-I nodes and 43% are type-II.

Degree distribution of the subtypes shows that type-I nodes tend to be hubs, whereas the average degree of type-II nodes is similar to the average degree of the network (Fig. 3D). Indeed, type-II nodes cannot be distinguished from the rest of the nodes based on any other network properties analyzed (Fig. S5G). Furthermore, type-I nodes show literature and annotation bias compared with type-II nodes (Fig. 3 E and F). With respect to diseases, both node types show similar enrichment for cancer genes and other human diseases (Fig. 3G). In contrast to type-I nodes that tend to be hubs and well-studied genes, type-II nodes are poorly studied and show no special network feature except indispensability, suggesting that control theory brings orthogonal information to traditional network analysis.

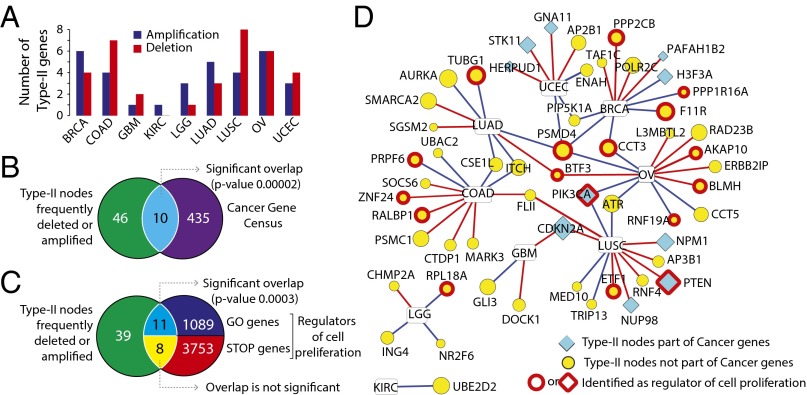

Applying Network Controllability Analysis to Mine Cancer Genomic Data.

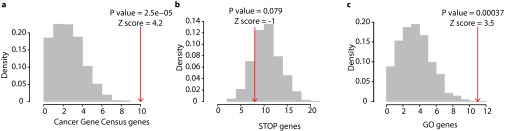

Our finding that indispensable nodes (both type-I and type-II) are more likely to correspond to cancer genes prompted us to systematically survey the perturbation of those genes in cancer. We analyzed data from 1,547 patients obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (cancergenome.nih.gov) and cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (36), representing nine different cancer types (Dataset S4). Specifically, we analyzed the amplification or deletion of type-II indispensable nodes in nine cancer types. Note that the copy number alteration (CNA) data are normalized to the expression levels to identify the amplification or deletion that results in expression level changes (SI Text). We ranked all genes based on the number of patients where the gene is amplified or deleted and selected the top 1% as frequently amplified/deleted genes; 56 type-II genes were identified as part of the top 1% of deleted/amplified genes in nine cancer types (Fig. 4A and Dataset S4). Strikingly, 10 of 56 type-II genes are known cancer genes, an overlap that is highly significant (P = 0.00002) (Fig. 4B and Fig. S6A). Interestingly, the frequency of deletion and amplification of type-II indispensable nodes is not significantly enriched compared with random sets, an observation that was similar to cancer gene census gene list (Dataset S4). Furthermore, we compared the type-II genes with results from a cell proliferation screen (37) that identified a subset of genes that regulate cell proliferation (“GO” genes induce the proliferation and “STOP” genes suppress the proliferation); 17 of 56 genes represent regulators of cell proliferation (11 GO genes, 8 STOP genes, and 2 genes part of both GO and STOP genes) (Fig. 4C and Fig. S6 B and C). The overlap between type-II genes and GO genes are statistically significant (P = 0.0003). Of 56 genes, 10 genes are frequently perturbed in multiple cancer types [e.g., proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase, 4 (PSMD4) in four different cancers], and all of them show similar deletion or amplification profile (e.g., PSMD4 amplified in all four cancers) (Fig. 4D). Almost half of the genes (23 genes) are poorly studied, with less than 50 associated PubMed records; for instance, small G protein signaling modulator 2 (SGSM2) is associated with only eight PubMed records (Fig. 4D). These contextual evidences, along with the indispensability, suggest that these 46 type-II nodes could be potential cancer genes.

Fig. 4.

Applying network controllability to mine cancer genomic data. (A) Type-II genes frequently amplified or deleted in cancer patients (part of top 1% genes). The bar plot shows number of type-II genes deleted/amplified in brain lower grade glioma (LGG), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV), uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC), breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), and glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cancers. (B) Overlap between frequently deleted/amplified type-II genes and known cancer genes. (C) Overlap between frequently deleted/amplified type-II genes and regulators of cell proliferation (STOP genes reduces cell proliferation and GO genes increases cell proliferation). The P values show the significance of overlap calculated based on 1000 random sets. (D) Network representation of 56 type-II genes frequently deleted (red edge) or amplified (blue edge) in nine different cancer types. The node size corresponds to the number of PubMed records associated with the gene.

Fig. S6.

Enrichment analysis of type-II indispensable nodes frequently amplified/deleted in cancer. Numbers of type-II indispensable nodes (frequently amplified/deleted in cancer) overlapping with genes causally associated with cancer (Cancer Gene Census) (17) (A), negative regulators of cell proliferation (STOP genes) (37) (B), and positive regulators of cell proliferation (GO genes) (37) (C) are shown in red arrows, and their respective size-controlled random set distributions in gray bars.

Database of Directed PPI Network with Predicted Controllability.

We created the DirectedPPI database (www.flyrnai.org/DirectedPPI) to navigate the directed human PPI network with predicted controllability. Users can enter a gene or upload a list of genes and our tool generates a network with directed edges connecting the input list. Our tool also accepts gene list with values (e.g., mutation frequency, P values from GWAS, or expression changes). Three different node types (indispensable, neutral, and dispensable) are distinguished with node shape and color and for these nodes all of the properties analyzed in this article are displayed. This tool will be useful to analyze disease datasets and other high-throughput datasets to identify indispensable nodes and their interconnections.

SI Text

Directed Human PPI Network.

The directed human PPI network was compiled from our previous study (13). Briefly, a Naïve Bayesian classifier was applied to predict potential direction of signal flow between the ith and jth interacting proteins pi and pj as pi → pj, pj → pi or both. The classifier uses features derived from the shortest PPI paths between membrane receptors and transcription factors and assigns confidence for each predicted edge directions ranging from 0.5 to 1. The weighted and directed edges are then encoded in an N × N matrix, and A is denoted as the weighted adjacency matrix of the directed graph for the PPI network. The element of A in the ith row and jth column is denoted as aij and is defined as follows: aij is in the range [0.5,1] if there is signal flow from protein pj to pi otherwise aij = 0.

Controllability Analysis and Node Classification.

Recently, we developed a mathematical framework and analytical tools to identify MDS, with size denoted as ND, whose control is sufficient to ensure the structural controllability of linear dynamics (14) and local structural controllability for nonlinear dynamics (SI Text, Local Structural Controllability) on any directed weighted network. This is achieved by mapping the structural controllability problem in control theory to the maximum matching problem in graph theory, which can be solved in polynomial time (15). Here, an edge subset M in a directed network or digraph is called a “matching” if no two edges in M share a common starting node or a common ending node. A node is “matched” if it is an ending node of an edge in the matching. Otherwise, it is “unmatched.” A matching of maximum cardinality is called a “maximum matching.” (In general, there could be many different maximum matchings for a given digraph.) We proved that the unmatched nodes that correspond to any maximum matching can be chosen as driver nodes to control the whole network. Identifying a minimum set of driver nodes is equivalent to choosing an input matrix (often denoted as B) with the minimum number of columns (see SI Text, Local Structural Controllability and ref. 14 for more details). The detailed construction of the input matrix B is not necessary for the identification of driver nodes. This is only mentioned to connect the notion of a driver node to the theoretical discussions in SI Text, Local Structural Controllability.

After a node is removed, denote the minimum number of driver nodes of the damaged network as ND′. In this work, we classified nodes into three categories. (i) A node is indispensable if in its absence we have to control more driver nodes (i.e., ND′ > ND). For example, removal of any node in the middle of a directed path will break the path and cause the ND increase. Hence, all but the start and end nodes of a directed path are indispensable. (ii) A node is dispensable if in its absence we have ND′ < ND. For example, removal of one leaf node in a star will decrease ND by 1. (iii) A node is neutral if in its absence ND′ = ND. For example, removal of the central hub in a star will not change ND at all.

Note that a driver node in any MDS can never be an indispensable node. This can be proven by contradiction. Assume a driver node i is indispensable. According to the minimum input theorem (9), driver nodes are just unmatched nodes with respect to a particular maximum matching. There are two cases; case 1: the driver node i has no downstream neighbors [i.e., kout(i) = 0], then in its absence, ND′ = ND − 1; and case 2: the driver node i has at least one downstream neighbors [i.e., kout(i) > 0]. There are two subcases; case 2.1: if in the maximum matching, one of node i’s downstream neighbors (node j) is matched by node i, then in the absence of node i, node j will become unmatched (i.e., a new driver node), rendering ND′ = ND; case 2.2: if none of node i’s downstream neighbors are matched by node i, then in the absence of node i, ND′ = ND − 1. In all of the cases, we do not have ND′ > ND, which is in contrast to the definition of indispensable nodes. Hence, driver nodes cannot be indispensable.

Enrichment Analysis.

To estimate the significance of overlap between a given node type S and given dataset D, we compute an enrichment z score as

where SD is number of proteins from dataset D overlapping with node type S and RD is the number of proteins from dataset D overlapping with random set of proteins of same size as N. Mean and SD of RD is computed from 1,000 simulations of random sets. Note that the entire network with 6,339 proteins is used as the background for random sampling. In addition to the z score, we also computed the P value (two-tailed) by comparing the SD with RD distribution (modeled as Gaussian distribution). In the case of degree- or literature-controlled random sets, the random sets are sampled such that the average degree or average PubMed records of random sets matches the average of node type S.

Datasets Used for Enrichment Analysis.

All of the datasets used for the enrichment analysis in this study are listed in Dataset S2. This includes the source of the data, reference, number of proteins compiled, and overlap with human directed PPI network. The datasets were downloaded from respective databases or publications as mentioned in Dataset S2. The gene or protein IDs from various resources were mapped to Entrez gene IDs. All compiled datasets are available as an integrated table that shows the nodes and the overlap with respective datasets (Dataset S1).

Analysis of Cancer Genomic Datasets.

Copy number alteration data for nine cancer types were downloaded from the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (version corresponds to April 2013; www.cbioportal.org). Using the GISTIC algorithm (46), the cBioPortal provides putative values of copy number alterations for each cancer patient. The GISTIC score −2, −1, 0, 1, 2 corresponds to deep loss (possibly a homozygous deletion), single-copy loss (heterozygous deletion), diploid, low-level gain, and high-amplification, respectively. The gene expression data for each cancer type were downloaded from the TCGA (version corresponds to April 2013; https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga). The tumor-matched datasets (for each participant have been analyzed and compared with normal tissue on the CNA and gene expression level) were used in the analysis. Level 3 TGCA data (expression calls for genes, per sample) was used in our study. The TCGA data were downloaded by using TCGA web interface with filters set as “Data Type: Expression-Genes”; “Data Level: Level 3”; “Tumor/Normal: Tumor-matched.”

Next, we filtered for patients with both CNA and expression data available (details are available in Dataset S4). We computed a z score for each gene in a patient to identify whether the amplification or deletion results in expression change for the corresponding gene. Briefly, for each gene the diploid mean and SD of expression values were calculated using the data from patients without any copy number alteration (GISTIC score, 0; diploid). Using the diploid mean and SD, we computed z score for each gene in a given patient. A gene is defined as amplified if the GISTIC score is ≥1 and the z score is ≥1.5 and deleted if the GISTIC score is ≤−1 and the z score is ≤−1.5. All of the data preprocessing and normalization were performed using Perl and Java scripts developed in house.

Local Structural Controllability.

A dynamic system is controllable if, with a suitable choice of inputs, it can be driven from any initial state to any final state in finite time (2). Most complex biological systems are characterized by nonlinear interactions between the components, and often only local properties can be verified. Similarly, it is often easier to obtain local analytical results for controllability of nonlinear systems. Here, we review a sufficient condition for “local controllability” of a nonlinear system about a trim point. A system is “locally controllable” if there exists a neighborhood in the state space such that all initial conditions in that neighborhood are controllable to all other elements in the neighborhood with locally bounded trajectories (47). This definition of controllability can be verified by checking the well-known “Kalman rank condition” used in the controllability analysis of linear systems. The rest of the section is tutorial in fashion so as to illustrate how the adjacency matrix can be used to analyze the local controllability of a PPI network.

Consider a dynamic system governed by a set of ordinary differential equations

where is the state vector and t is time. We are interested in determining an matrix B such that the controlled system

| [1] |

is locally controllable through the input Let be defined as and The matrix G(z*) is referred to as the Kalman controllability matrix. The dynamics in Eq. 1 are locally controllable around if is rank n (Theorem 7 in ref. 47; Proposition 11.2 in ref. 48). The local controllability analysis of Eq. 1 about a trim point therefore reduces to the classic Kalman controllability analysis (2) of the linear dynamics

| [2] |

Recall that the dynamics in Eq. 2 are deemed “structurally controllable” if there exists another pair (A0,B0) with the same structure as the pair (A,B) (49). That is, we are not concerned about the particular values in (A,B), just the pattern of the nonzero entries in (A,B). The dynamics in Eq. 1 are deemed “locally structurally controllable” if the linearized dynamics in Eq. 2 are structurally controllable.

For the purposes of this work, the adjacency matrix of the experimentally determined PPI network is used to find the structure of A in ref. 2, then the nodes are classified based upon their impact on the structural controllability (Methods).

Discussion

Studying the controllability of a complex biological network is rather difficult, because of the fact that we typically do not know the true functional form of the underlying dynamics. However, most biological systems operate near homeostasis, so local properties are indeed what we want to ascertain. Here, we showed that application of linear control tools to study the local structural controllability of inherent nonlinear biological networks provides meaningful predictions. Furthermore, we demonstrated that local controllability tools help identifies known human diseases genes and this can be used to identify novel disease genes and drug targets.

Our analysis of directed human PPI network identifies 36% of the nodes as driver nodes, which is similar to what has been observed in metabolic networks (∼30%) (14). The node classification based on network controllability shows distinct biological properties in the context of essentiality, conservation and regulation. Specifically, we found that indispensable nodes are well conserved, highly regulated at the level of translational and PTMs, and important for the transition between healthy and disease states. Interestingly, this enrichment pattern is partially shared by the nodes in the minimum dominating sets that are located in strategically important positions in controlling the network (38–40). Furthermore, identification of the indispensable nodes as primary targets of diseases causing mutations, viruses, and drugs revealed a potential application of this framework to identify novel disease genes and potential drug targets.

Interestingly, disease-causing mutations, viruses, and drugs target fragile points (indispensable nodes) that determine the number of driver nodes rather than the driver nodes themselves, suggesting that network controllability is crucial in transitioning between healthy and disease states. Although network topology-based properties such as hubs and modules are commonly used to identify disease genes (41–44), the controllability perspective provides a complementary network analysis framework for network medicine. In particular, type-II nodes that are not distinguishable from existing network properties and without publications bias were still identified by our controllability framework as nodes of special interest. We envision that in the future, improving the quality and the completeness of interactome maps and integrating dynamics of network components would hugely impact our understanding of biological networks both in the context of biological function and human disease.

Methods

Datasets and Enrichment Analysis.

All of the datasets used for the enrichment analysis in this study are listed in Dataset S2. Details on the directed human PPI network, random networks, and datasets used for enrichment analysis can be found in SI Text.

Controllability Analysis and Node Classification.

To identify MDS, with size denoted as ND, whose control is sufficient to ensure the structural controllability of linear dynamics (14) and local structural controllability for nonlinear dynamics (SI Text) on any directed weighted network, we can map the structural controllability problem in control theory to the maximum matching problem in graph theory, which can be solved in polynomial time (15).

After a node is removed, denote the minimum number of driver nodes of the damaged network as ND′. We can classify nodes into three categories: (i) a node is indispensable if in its absence we have to control more driver nodes (i.e., ND′ > ND); (ii) a node is dispensable if in its absence we have ND′ < ND); and (iii) a node is neutral if in its absence ND′ = ND. Note that indispensable nodes are never driver nodes in any control configurations or MDSs, which can be proven by contradiction (SI Text). More information on node classification and local structural controllability can be found in SI Text.

Random Networks.

To compare the real network with its randomized counterparts, we performed two types of randomization: (i) edge rewiring: we randomly choose a p fraction of edges to rewire, using the degree-preserving random rewiring algorithm (45); and (ii) edge flipping: we randomly choose a p fraction of edges to flip their directions. We tune p from 0 up to 1, resulting in a series of randomized networks.

Analysis of Cancer Genomic Datasets.

Copy number alteration data for nine cancer types were downloaded from the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (www.cbioportal.org). Gene expression data for each cancer type were downloaded from TCGA (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga). Next, we filtered for patients with both CNA and expression data available (details are available in Dataset S4). We computed a z score for each gene in a patient to identify whether the amplification or deletion results in expression change for the corresponding gene. A gene is defined as amplified if the Genomic Identification of Significant Targets in Cancer (GISTIC) score is ≥1 and the z score is ≥1.5 and deleted if the GISTIC score (46) is ≤−1 and the z score is ≤−1.5 (SI Text).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. W. Kirschner, S. E. Mohr, I. T. Flockhart, S. Rajagopal, and Bingbo Wang for helpful suggestions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants P01-CA120964, Centers of Excellence of Genomic Science (CEGS) 1P50HG004233, and 1R01HL118455-01A1 and John Templeton Foundation Awards PFI-777 and 51977. N.P. is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1603992113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Isidori A. 1995. Nonlinear Control Systems (Springer, Berlin, New York), 3rd Ed.

- 2.Kalman RE. Mathematical description of linear dynamical systems. J Soc Indust Appl Math Ser A Control. 1963;1(2):152–192. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slotine JJE, Li W. 1991. Applied Nonlinear Control (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ)

- 4.Iglesias PA, Ingalls BP. 2010. Control Theory and Systems Biology (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA)

- 5.Del Vecchio D, Murray RM. 2015. Biomolecular Feedback Systems (Princeton Univ Press, Princeton)

- 6.Balázsi G, van Oudenaarden A, Collins JJ. Cellular decision making and biological noise: From microbes to mammals. Cell. 2011;144(6):910–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luenberger DG. 1979. Introduction to Dynamic Systems: Theory, Models, and Applications (Wiley, New York)

- 8.Csete ME, Doyle JC. Reverse engineering of biological complexity. Science. 2002;295(5560):1664–1669. doi: 10.1126/science.1069981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangan S, Alon U. Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(21):11980–11985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133841100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callura JM, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Genetic switchboard for synthetic biology applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(15):5850–5855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203808109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nepusz T, Vicsek T. Controlling edge dynamics in complex networks. Nat Phys. 2012;8(7):568–573. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiel C, Yus E, Serrano L. Engineering signal transduction pathways. Cell. 2010;140(1):33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinayagam A, et al. A directed protein interaction network for investigating intracellular signal transduction. Sci Signal. 2011;4(189):rs8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu YY, Slotine JJ, Barabási AL. Controllability of complex networks. Nature. 2011;473(7346):167–173. doi: 10.1038/nature10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopcroft JE, Karp RM. An n^{5/2} algorithm for maximum matchings in bipartite graphs. SIAM J Comput. 1973;2:225–231. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashburner M, et al. The Gene Ontology Consortium Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Futreal PA, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(3):177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins ME, Claremont M, Major JE, Sander C, Lash AE. CancerGenes: A gene selection resource for cancer genome projects. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D721–D726. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hindorff LA, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(23):9362–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy MI, Hirschhorn JN. Genome-wide association studies: Potential next steps on a genetic journey. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(R2):R156–R165. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brass AL, et al. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008;319(5865):921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.König R, et al. Global analysis of host-pathogen interactions that regulate early-stage HIV-1 replication. Cell. 2008;135(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeung ML, Houzet L, Yedavalli VS, Jeang KT. A genome-wide short hairpin RNA screening of jurkat T-cells for human proteins contributing to productive HIV-1 replication. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(29):19463–19473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou H, et al. Genome-scale RNAi screen for host factors required for HIV replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4(5):495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goff SP. Knockdown screens to knockout HIV-1. Cell. 2008;135(3):417–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jäger S, et al. Global landscape of HIV-human protein complexes. Nature. 2011;481(7381):365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature10719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanzoni A, et al. MINT: A Molecular INTeraction database. FEBS Lett. 2002;513(1):135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navratil V, et al. VirHostNet: A knowledge base for the management and the analysis of proteome-wide virus-host interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D661–D668. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, et al. Interpreting cancer genomes using systematic host network perturbations by tumour virus proteins. Nature. 2012;487(7408):491–495. doi: 10.1038/nature11288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calderwood MA, et al. Epstein-Barr virus and virus human protein interaction maps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(18):7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knox C, et al. DrugBank 3.0: A comprehensive resource for ‘omics’ research on drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D1035–D1041. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hopkins AL, Groom CR. The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1(9):727–730. doi: 10.1038/nrd892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia T, et al. Emergence of bimodality in controlling complex networks. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2002. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411(6835):355–365. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkatesan K, et al. An empirical framework for binary interactome mapping. Nat Methods. 2009;6(1):83–90. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao J, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6(269):pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solimini NL, et al. Recurrent hemizygous deletions in cancers may optimize proliferative potential. Science. 2012;337(6090):104–109. doi: 10.1126/science.1219580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wuchty S. Controllability in protein interaction networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(19):7156–7160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311231111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nacher JC, Akutsu T. Dominating scale-free networks with variable scaling exponent: Heterogeneous networks are not difficult to control. New J Phys. 2012;14(7):073005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nacher JC, Akutsu T. Analysis of critical and redundant nodes in controlling directed and undirected complex networks using dominating sets. J Complex Netw. 2014;2(4):394–412. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rambaldi D, Giorgi FM, Capuani F, Ciliberto A, Ciccarelli FD. Low duplicability and network fragility of cancer genes. Trends Genet. 2008;24(9):427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barabási AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: A network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(1):56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor IW, et al. Dynamic modularity in protein interaction networks predicts breast cancer outcome. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(2):199–204. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin Y, et al. A systems approach identifies HIPK2 as a key regulator of kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. 2012;18(4):580–588. doi: 10.1038/nm.2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maslov S, Sneppen K. Specificity and stability in topology of protein networks. Science. 2002;296(5569):910–913. doi: 10.1126/science.1065103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beroukhim R, et al. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: Methodology and application to glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(50):20007–20012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sontag ED. 1998. Mathematical Control Theory: Deterministic Finite Dimensional Systems (Springer, New York), 2nd Ed.

- 48.Sastry S. 1999. Nonlinear System: Analysis, Stability, and Control (Springer, New York)

- 49.Lin C-T. Structural controllability. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 1974;19(3):201–208. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo H, Lin Y, Gao F, Zhang CT, Zhang R. DEG 10, an update of the database of essential genes that includes both protein-coding genes and noncoding genomic elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D574–D580. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen WH, Minguez P, Lercher MJ, Bork P. OGEE: An online gene essentiality database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D901–D906. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu Y, et al. An integrative approach to ortholog prediction for disease-focused and other functional studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:357. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hornbeck PV, et al. PhosphoSitePlus: A comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D261–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ben-Shlomo I, Yu Hsu S, Rauch R, Kowalski HW, Hsueh AJ. Signaling receptome: A genomic and evolutionary perspective of plasma membrane receptors involved in signal transduction. Sci STKE. 2003;2003(187):RE9. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.187.re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park J, et al. Building a human kinase gene repository: Bioinformatics, molecular cloning, and functional validation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(23):8114–8119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503141102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298(5600):1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Messina DN, Glasscock J, Gish W, Lovett M. An ORFeome-based analysis of human transcription factor genes and the construction of a microarray to interrogate their expression. Genome Res. 2004;14(10B):2041–2047. doi: 10.1101/gr.2584104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beck M, et al. The quantitative proteome of a human cell line. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:549. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woodsmith J, Kamburov A, Stelzl U. Dual coordination of post translational modifications in human protein networks. PLOS Comput Biol. 2013;9(3):e1002933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fazekas D, et al. SignaLink 2 - a signaling pathway resource with multi-layered regulatory networks. BMC Syst Biol. 2013;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doncheva NT, Assenov Y, Domingues FS, Albrecht M. Topological analysis and interactive visualization of biological networks and protein structures. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(4):670–685. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.