Significance

Steroid receptor coactivator-3 (SRC-3) sits at the nexus of many intracellular signaling pathways critical for cancer formation and proliferation. Although the oncogenic role of SRC-3 has been well established in breast and other cancers, coactivators are usually considered as “undruggable” because of their large and flexible structures. Herein, we developed SI-2 as a new class of potent small-molecule inhibitors for SRC-3. SI-2 can selectively reduce the transcriptional activities and the protein concentrations of SRC-3 in cells and significantly inhibit primary tumor growth in a breast cancer mouse model. This work not only has the potential to improve breast cancer treatment, but also to provide a viable strategy to target often “undruggable but important” protein targets without ligand-binding sites.

Keywords: steroid receptor coactivator, small-molecule inhibitor, breast cancer, drug development, protein–protein interactions

Abstract

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) play a central role in most biological processes, and therefore represent an important class of targets for therapeutic development. However, disrupting PPIs using small-molecule inhibitors (SMIs) is challenging and often deemed as “undruggable.” We developed a cell-based functional assay for high-throughput screening to identify SMIs for steroid receptor coactivator-3 (SRC-3 or AIB1), a large and mostly unstructured nuclear protein. Without any SRC-3 structural information, we identified SI-2 as a highly promising SMI for SRC-3. SI-2 meets all of the criteria of Lipinski’s rule [Lipinski et al. (2001) Adv Drug Deliv Rev 46(1-3):3–26] for a drug-like molecule and has a half-life of 1 h in a pharmacokinetics study and a reasonable oral availability in mice. As a SRC-3 SMI, SI-2 can selectively reduce the transcriptional activities and the protein concentrations of SRC-3 in cells through direct physical interactions with SRC-3, and selectively induce breast cancer cell death with IC50 values in the low nanomolar range (3–20 nM), but not affect normal cell viability. Furthermore, SI-2 can significantly inhibit primary tumor growth and reduce SRC-3 protein levels in a breast cancer mouse model. In a toxicology study, SI-2 caused minimal acute cardiotoxicity based on a hERG channel blocking assay and an unappreciable chronic toxicity to major organs based on histological analyses. We believe that this work could significantly improve breast cancer treatment through the development of “first-in-class” drugs that target oncogenic coactivators.

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) play a central role in most biological processes, and therefore represent an important class of targets for therapeutic development (1). Biologics-based therapeutics, such as antibodies, exemplify success in PPI regulation (2). However, antibodies usually can only be applied to protein targets on cell surfaces because of their impermeability to plasma membranes (2). Although small-molecule drugs can readily cross membranes, applying small-molecule inhibitors (SMIs) to disrupt PPIs is a challenging task because ∼750–1,500 Å2 of protein surface area is involved at the interface of PPIs (3), which is too large for SMIs to cover. In addition, these interacting protein surfaces do not have pocket-like small-molecule binding sites (2). Therefore, these PPI sites are deemed as “undruggable” targets for SMIs. The Holy Grail of drug development is to render small molecules the power of biologics to regulate PPIs.

The current strategies for designing small-molecule PPI inhibitors primarily rely on the structural information of the protein targets (4). Clackson and Wells discovered that only a small set of residues at the PPI interface are critical for their interactions, known as “hot spots” (5). Therefore, current drug design for PPIs is mainly focused on small hot spots that can be covered by a drug-sized molecule. Unfortunately, many important proteins do not have structural information available or well-defined structures, such as intrinsically disordered proteins. Alternative drug-discovery strategies are urgently needed to target this subset of proteins without knowledge of structural information.

Coactivators are non-DNA binding proteins that mediate transcriptional activities of nuclear receptors (NRs) and many other transcription factors (6–10). Since the O’Malley group identified the first coactivator, steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1) (11), there have been more than 400 coactivators identified and associated with a wide range of human diseases, including neurological and metabolic disorders, inflammatory diseases, and cancer (6–8). Taking estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer as an example, cancer cells can use a number of mechanisms to overcome selective estrogen receptor modulators to silence the NR activity. Although breast cancer cells can become resistant to endocrine therapies, it is essential for them to recruit coactivators to survive. Earlier efforts have been focused on developing peptides and SMIs to interfere with the interactions between NRs and coactivators (12–14). A major drawback of this strategy is that overexpression of coactivators, a hallmark of endocrine resistance, often occurs regardless of the context of which NR is expressed in the cancer cell. Coactivators also partner with other transcription factors; therefore, SMIs that can directly target the overexpressed coactivators and reduce their activity or stability should be preferred for drug development.

Identification of SMIs for coactivators is challenging because coactivators are usually considered as undruggable because of their large and flexible structures (6–9). We recently developed a cell-based functional assay for high-throughput screening to identify SMIs for steroid receptor coactivator-3 (SRC-3). Without any SRC-3 structural information, we identified and improved a series of SMIs that can target SRC-3 (15–17). We initially reported gossypol as our first “proof-of-concept” SRC-3 SMI (17). Despite the encouraging success of gossypol as the first selective SRC-3 SMI, the IC50 values of gossypol are in the micromolar range, which is suboptimal for drug development and may cause off-target toxicity (17). Subsequently, we reported bufalin, a cardiac glycoside, as a potent SRC-3 SMI (16). Bufalin is an active component in the Chinese medicine Huachansu, which is prepared from the skin and parotid venom glands of the Asiatic toad. Bufalin directly binds to SRC-3 in its receptor interacting domain (RID) and selectively reduces the concentration of SRC-3 in breast, lung, and pancreatic cancer cell lines without perturbing overall protein expression patterns (16). Additionally, bufalin is selectively toxic to cancer cells with IC50 values in the low nanomolar range, and normal cell viability is not affected (16, 18, 19). Importantly and most excitingly, bufalin sensitizes breast and lung cancer cells to the inhibitory effects of other chemotherapeutics and inhibits primary tumor growth in vivo. Other groups also reported that bufalin and other cardiac glycosides can inhibit transcription factors and induce synergistic immune responses (19–28). Unfortunately, cardiac glycosides are well known for their cardiotoxicity. Although we have developed bufalin nanoparticles (16) and a phospho-bufalin prodrug (29) to reduce cardiotoxicity, the potential of cardiac glycosides to cause cardiac arrest dampens the enthusiasm for their clinical use.

In this report, we describe a new class of SRC-3 SMI: SRC-3 inhibitor-2 (SI-2). Unlike gossypol and bufalin, SI-2 is an unnatural compound and identified through a combination of high-throughput screening and medicinal chemistry optimization. SI-2 meets all of the criteria for drug-like compounds. Because of the well-established roles of SRC-3 in endocrine resistance and tumor metastasis in breast cancer, we tested the therapeutic efficacy of SI-2 in a series of breast cancer cell lines and an orthotopic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) mouse model. Similar to bufalin, SI-2 can selectively reduce the protein concentrations and transcriptional activities of SRC-3, and selectively kill breast cancer cells with IC50 values in the low nanomolar range but not affecting normal cell viability. Different from bufalin, SI-2 has a much improved toxicity and pharmacokinetic profile. In addition, an animal study showed that SI-2 can significantly inhibit breast tumor growth in vivo without any observable toxicity. Based on our strong data, we envision that SI-2 is a promising drug candidate as an SRC-3 SMI that could potentially expand breast cancer treatment. In addition, our efforts to identify coactivator SMIs will build confidence for other researchers to develop approaches to target relatively unstructured, regulatory proteins that are designated as “important but difficult” targets in the future.

Results

Identification of SI-2 as a Potent SRC-3 SMI.

Through a high-throughput compatible luciferase assay, we screened with the Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers (MLPCN) library of the NIH to identify compounds targeting the intrinsic transcriptional activities of SRC-3 (PubChem AID 588352). In these assays, we evaluated the effects of compounds by measuring the output of a GAL4-responsive luciferase reporter (pGL-LUC) in the presence of GAL4 DNA binding (DBD) SRC coactivator fusion proteins (pBIND-SRC) (30). Compounds that inhibit the intrinsic ability of SRC coactivators to activate transcription will lead to a decrease in expression of the luciferase gene, resulting in reduced luminescence. Additionally, active compounds also were tested in a counter screen using cells transfected with a DBD-VP16 fusion protein to exclude those perturbing pGL/pBIND systems (AID 588794). Only those compounds that reduce SRC-3 activity greater than they do toward the VP16 control were defined as potential SRC-3 inhibitors. Active compounds retrieved from the primary screens were clustered according to structure similarities in PubChem. Through dose-dependent toxicity studies, we identified SI-1 (Fig. S1) as a promising candidate for further development. SI-1 has a submicromolar IC50 value in a MDA-MB-468 cell line, a TNBC cell line used as a model in this study.

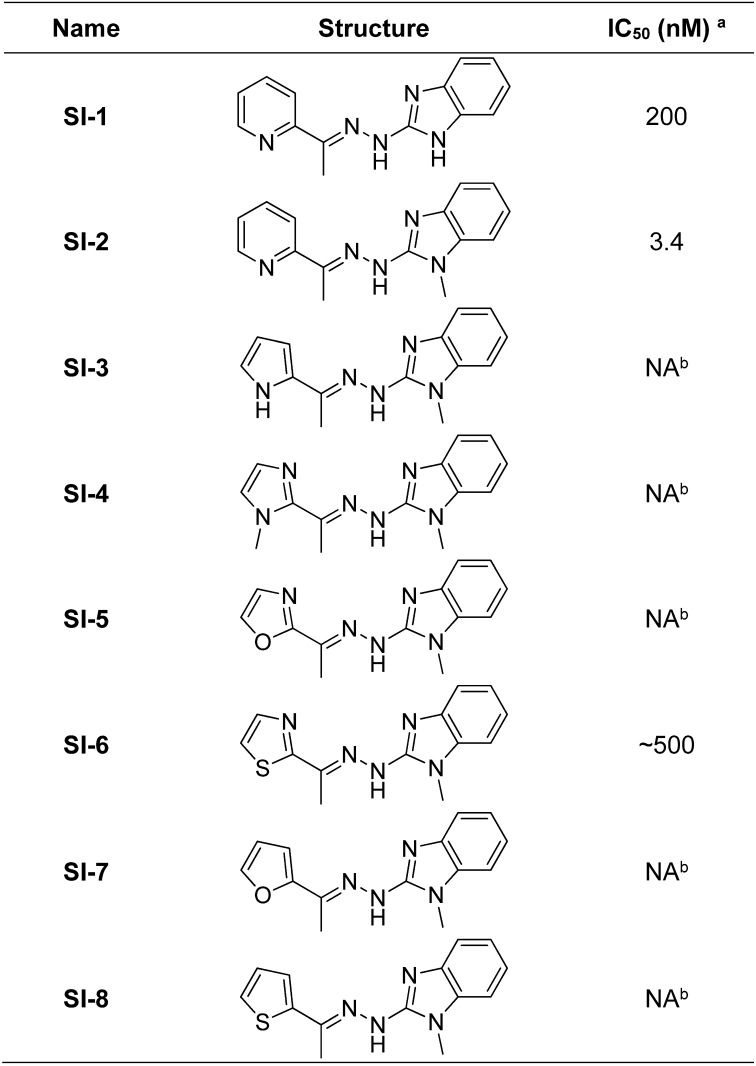

Fig. S1.

Chemical structures of SI-1 to SI-8 and the corresponding IC50 values in MDA-MB-468 cells. Superscript “a” signifies the IC50 values were measured in MDA-MB-468 cells by incubating a series of concentrations of the corresponding compounds for 72 h. Superscript “b” signifies no appreciable cell death was observed at a compound concentration of 500 nM.

Subsequently, we performed a series of medicinal chemistry optimizations to enhance the potency of SI-1. We discovered that SI-2 (Fig. 1A), which is formed by introduction of N-methylation to the benzimidazole ring in SI-1, can decrease the IC50 value by ∼60-fold in the same TNBC cell line. In addition, we also substituted the pyridine ring in SI-2 with a series of hetero-aromatic groups (Fig. S1). Unfortunately, this substitution significantly reduced the potency of these compounds in MDA-MB-468 cells. In this study, we chose SI-2 as a leading SRC-3 SMI candidate in the following in vitro and in vivo tests.

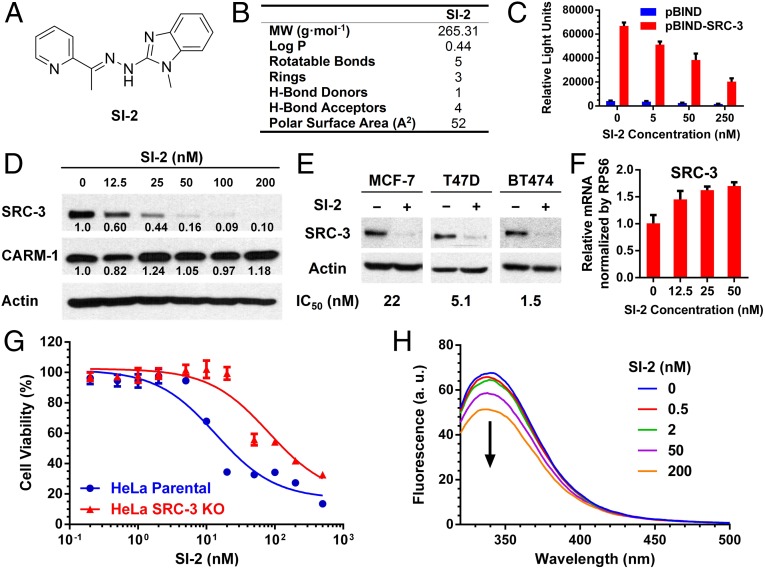

Fig. 1.

SI-2 as a potent SRC-3 SMI. (A) Structure of SI-2. (B) Physical characterization of SI-2 drug-likeness properties. (C) SI-2 can selectively reduce the SRC-3 intrinsic transcriptional activities. Luciferase assays were performed in HeLa cells transiently transfected with the reporter vector pG5-LUC in combination with expression vectors for pBIND and pBIND-SRC-3 before incubation with SI-2 for 24 h. (D) Selective inhibition of SRC-3 by 24 h of SI-2 treatment in MDA-MB-468 cells. SRC-3, CARM-1, and actin were detected using Western blotting. Relative band intensities were normalized by actin. (E) Endocrine sensitive MCF-7 and T47D, and endocrine resistant BT474 cells were treated with SI-2 (100 nM) for 24 h, followed by Western blotting for the SRC-3 levels and MTT assays for the IC50 values. (F) SI-2 treatment does not decrease the SRC-3 mRNA level. The relative mRNA levels vs. RPS6 were quantified using qPCR in MDA-MB-468 cells treated with SI-2 for 24 h. (G) The viabilities of HeLa and HeLa SRC-3 KO cells treated with SI-2 for 72 h. (H) SI-2 directly binds to the RID of SRC-3. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra of SRC-3 RID (λex = 278 nm) were quenched with increasing concentrations of SI-2. All of the data represent mean ± SD.

Drug-Like Properties of SI-2.

SI-2 is a drug-like molecule and meets all of the criteria for Lipinski’s rule (31), Veber’s rule (32), and Oprea’s rule (33) of drug-likeness (Fig. 1B). SI-2 has a molecular weight of 265 g·mol−1 and an experimental LogP value of 0.44. In addition, SI-2 has five rotatable bonds and its numbers of hydrogen bond (H-bond) donor and acceptor are 1 and 4, respectively. The molecular polar surface area of SI-2 is calculated to be 52 Å2 based on a topological method (34), which is well below 140 Å2 and suggests good oral availability based on Veber et al. (32) rules. The thermodynamic and kinetic solubilities of SI-2 in PBS are 168 and 327 µg/mL, respectively.

SI-2 Inhibits Intrinsic Transcriptional Activity of SRC-3.

We investigated the effects of SI-2 on the intrinsic transcriptional activities of SRC-3. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with a pGL5-LUC reporter and expression vectors for pBIND and pBIND-SRC-3, followed by 24 h of treatment with different concentrations of SI-2. As shown in Fig. 1C, SI-2 significantly reduced the luciferase reporter activities in cells transfected in pBIND-SRC-3 in a dose-dependent manner, but only minimally affected the activity of pBIND. This result suggests that SI-2 can selectively inhibit the intrinsic transcriptional activities of SRC-3. Similar to bufalin, SI-2 also can inhibit the transcriptional activities of SRC-1 and SRC-2 (Fig. S2A), the other two members of the p160 family of steroid-receptor coactivators.

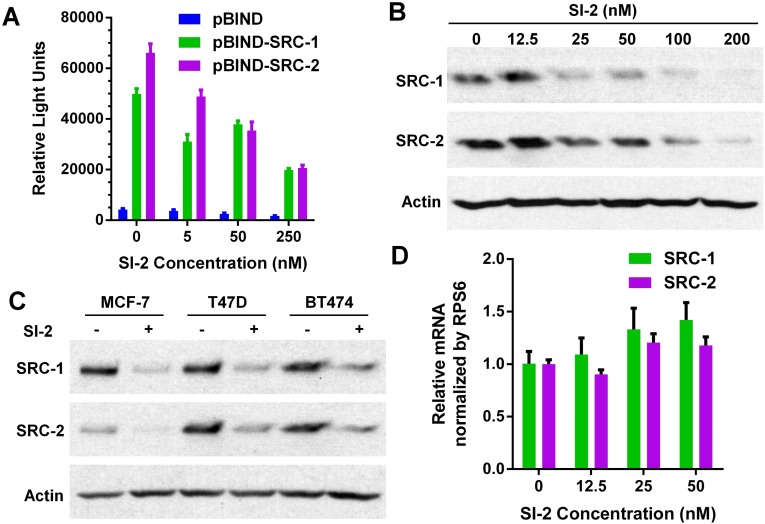

Fig. S2.

SI-2 inhibits the transcriptional activities and protein levels of SRC-1 and SRC-2. (A) SI-2 can reduce the intrinsic transcriptional activities of SRC-1 and SRC-2. Luciferase assays were performed in HeLa cells transiently transfected with the reporter vector pG5-LUC in combination with expression vectors for pBIND and pBIND-SRC-1 and pBIND-SRC-2 before incubation with SI-2 (0, 5, 50, and 250 nM) for 24 h [refer to Wang et al., (16) for details]. Data represent mean ± SD. (B) Inhibition of SRC-1 and SRC-2 by SI-2 in a dose-dependent manner. MDA-MB-468 cells were treated with different concentrations of SI-2 for 24 h. Cell extracts were then blotted and probed using antibodies against SRC-1, SRC-2, and actin. (C) Endocrine-sensitive MCF-7 and T47D, and endocrine resistant BT474 cells were treated with SI-2 (100 nM) for 24 h, followed by Western blotting for the SRC-1 and SRC-2 levels. (D) Relative SRC-1 and SRC-2 mRNA levels in MDA-MB-468 cells treated with different concentrations of SI-2 for 24 h. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

SI-2 Selectively Inhibits SRC-3 Protein Levels Posttranscriptionally.

We showed that the steady-state levels of coactivator proteins correlate with their transcriptional activities and with cancer progression (35). Therefore, we studied the effects of SI-2 on SRC-3 protein levels in MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells after 24 h of incubation. As shown in Fig. 1D, SI-2 selectively reduces cellular protein levels of SRC-3, but not that of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM-1), which is part of a multiprotein coactivator complex with SRC-3. Furthermore, inhibition of SRC-3 levels also was observed in other breast cancer cell lines, including endocrine sensitive MCF-7, T47D cells, and endocrine-resistant BT-474 cells (Fig. 1E). In addition, SI-2 can inhibit the protein levels of SRC-1 and SRC-2, but to a lesser extent than for SRC-3, especially at lower concentrations (Fig. S2 B and C).

To gain insights into the mechanism of SI-2–mediated SRC-3 protein down-regulation, we assessed whether 24 h of SI-2 treatment affected the production of mRNAs for each SRC family member in MDA-MB-468 cells. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) revealed that mRNA levels for SRC-1 and SRC-2 were not significantly altered (Fig. S2D), whereas the mRNA levels for SRC-3 were actually increased upon SI-2 incubation (Fig. 1F). This result is consistent with the mRNA level changes for the SRC family in bufalin-treated cells (16) and suggests that SI-2 reduces SRC protein levels posttranscriptionally.

SRC-3 Is Required for SI-2 Activity.

It is well established that targeting SRC-3 with siRNAs inhibits cell growth in many cancer types (7, 36). Considering the fact that the decreased cell viability induced by SI-2 is accompanied by reduced SRC-3 protein levels, we sought to investigate the specific role of the SRC-3 protein in blocking cancer cell proliferation. Previously, we used a zinc finger nuclease to knockout both SRC-3 alleles in the HeLa cell line and developed HeLa SRC-3 KO cells (16). Compared with parental SRC-3+/+ cells, the response of HeLa SRC-3 KO cells to SI-2 treatment is reduced by ∼fivefold (Fig. 1G). This finding supports the idea that SRC-3 protein is involved in mediating the cell response to SI-2 treatment. However, the remaining response of HeLa SRC-3 KO cells to SI-2 is likely because of the SRC-1 and SRC-2 that continue to be expressed in these cells and that also respond to SI-2 at a similar dose as SRC-3, in addition to any unknown off-target actions of the compound.

SI-2 Inhibits SRC-3 Through Direct Physical Interactions.

We used a fluorescence assay to demonstrate that down-regulation of SRC-3 by SI-2 proceeds through direct physical interaction with SRC-3. We found that the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra of the SRC-3 RID (λex = 278 nm) were quenched with increasing concentrations of SI-2, indicating that SI-2 binds directly to the RID of SRC-3 (Fig. 1H). In contrast, there were no changes of the intrinsic fluorescence observed for a KPC-2 β-lactamase, a negative control, upon addition of SI-2 (Fig. S3), which negates the possibility that the fluorescence changes of RID are a result of nonspecific interactions with SI-2.

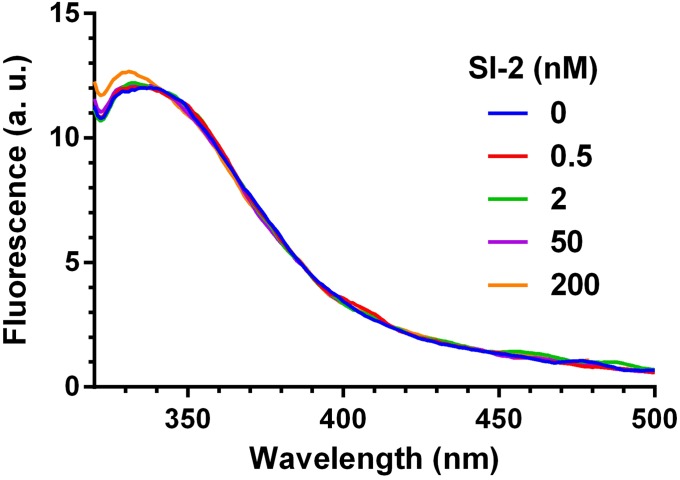

Fig. S3.

SI-2 does not interact with a β-lactamase–negative control protein. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra of β-lactamase (λex = 278 nm) were not affected with increasing concentrations of SI-2, suggesting that SI-2 binds SRC-3 through specific interactions.

SI-2 Selectively Kills Cancer Cells but Spares Normal Cells.

We then evaluated the cytotoxic effect of SI-2 on cancer cells. First, MTT assays were performed on MDA-MB-468 cells treated with SI-2 at different concentrations for 72 h. SI-2 can block MDA-MB-468 cell growth with an IC50 value of 3.4 nM (Fig. 2A), in line with the dose of SI-2 required to reduce SRC-3 protein levels in the cell (Fig. 2A). In addition, similar low nanomolar IC50 values also were observed for SI-2 in many other cell lines, including endocrine-sensitive, endocrine-resistant, and TNBC cells (Fig. 2B).

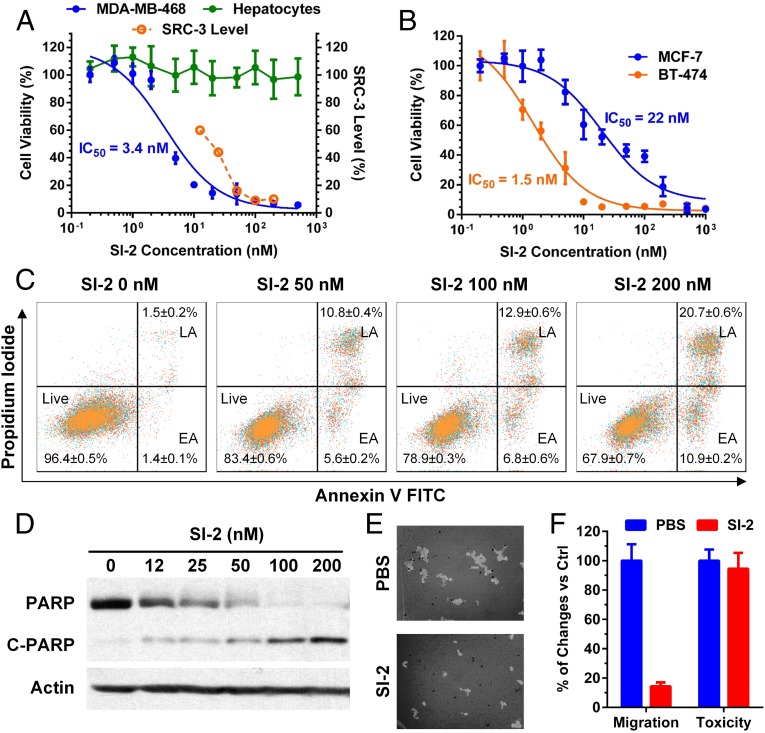

Fig. 2.

SI-2 selectively kills and inhibits migration of breast cancer cells, but spares normal cells. (A) SI-2 is selectively toxic to MDA-MB-468 cells with an IC50 value of 3.4 nM (Left axis), and normal cell viability (i.e., primary hepatocytes) is not affected. The toxicities were determined by MTT assays in cells treated with SI-2 for 72 h. Relative SRC-3 protein levels (Right axis, derived from Fig. 1D) after SI-2 treatment are shown as the dashed line. (B) SI-2 treatment kills MCF-7 and BT-474 cells with IC50 values in the low nanomolar range, measured using MTT assays. (C) SI-2 treatment induces apoptosis in cancer cells. MDA-MB-468 cells were treated with SI-2 for 24 h and stained with Annexin V and propidium iodide. Flow cytometry was performed to quantify the percentages of cancer cells in the early apoptosis (EA) and late apoptosis (LA) phases. (D) SI-2 treatment in cancer cells causes PARP cleavage, an apoptosis marker. MDA-MB-468 cells were treated with SI-2 for 24 h and PARP and cleaved PARP were quantified using Western blotting. (E) SI-2 inhibits migration of triple negative breast cancer cells. Cell migration assay of MDA-MB-468 cells was performed using a Cellomics cell motility kit. The bright area of 50 images for each sample were analyzed using ImageJ. (Magnification: 100×.) (F) Treatment of MDA-MB-468 cells with SI-2 (100 nM) for 12 h showed minimal toxicity but significant motility reduction. All of the data represent mean ± SD.

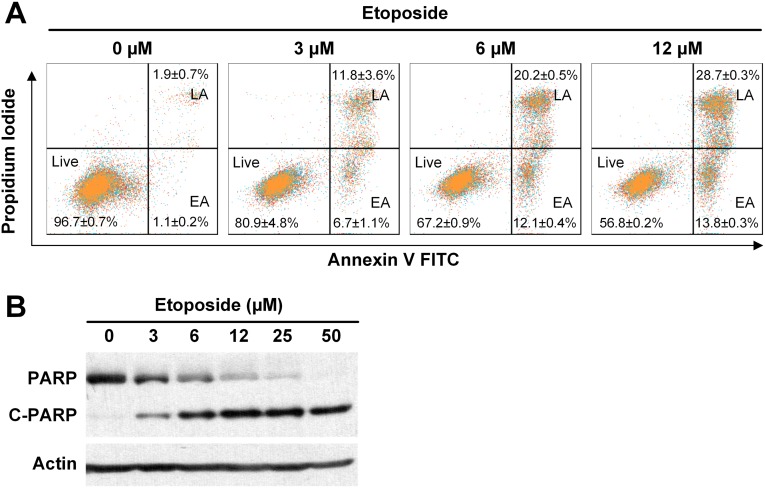

We performed apoptosis assays to examine the cause of the cytotoxic effect of SI-2 on cancer cells. Annexin V and propidium iodide were used to stain MDA-MB-468 cells treated with SI-2 at different concentrations for 24 h. Flow cytometry revealed that the percentages of cancer cells in the early and late apoptosis phases increase in a SI-2 dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C), which is similar to etoposide, a positive control, caused apoptosis (Fig. S4). In addition, we confirmed the apoptotic effect of SI-2 on cancer cells by measuring the poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage using Western blotting (Fig. 2D).

Fig. S4.

Etoposide induces apoptosis in cancer cells. (A) MDA-MB-468 cells were treated with different concentrations of etoposide and stained with Annexin V and propidium iodide. Flow cytometry was performed to quantify the percentages of cancer cells in the early apoptosis (EA) and late apoptosis (LA) phases. (B) Etoposide treatment in cancer cells causes PARP cleavage, an apoptosis marker. MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells were treated with different concentrations of etoposide for 24 h and PARP and cleaved PARP were quantified using Western blotting.

It is important to note that inhibition of SRC-3 is selectively toxic to cancer cells while sparing normal cells (16, 17), and prior data showed that knockout of the SRC-3 gene does not influence adult mice life span (37). Consistent with our previously reported SRC-3 SMIs, we did not observe any toxicity of SI-2 up to 500 nM (the highest concentration used) in primary hepatocytes (Fig. 2A), demonstrating the potential of SI-2 as a targeted therapy.

SI-2 Inhibits Migration of Breast Cancer Cells.

Down-regulation of SRC-3 can decrease cell motility, invasion, and tumor metastasis (38). We performed a cell migration assay of MDA-MB-468 cells in the presence and absence of SI-2 using a Cellomics cell motility kit. The bright areas of 50 images for each sample were analyzed using ImageJ. We found that SI-2 treatment can significantly reduce the motility of cancer cells (Fig. 2 E and F). It should be noted that under the same conditions, SI-2 caused minimal toxicity in MDA-MB-468 cells (Fig. 2F), indicating that the decrease of cell motility is not because of decrease of cell numbers.

SI-2 Is Nontoxic to Heart and Other Major Organs.

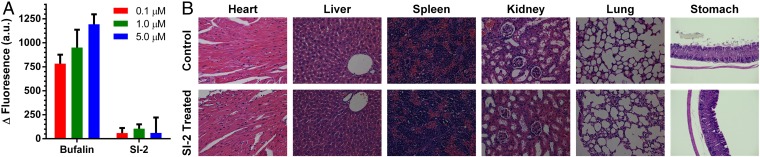

Minimizing cardiotoxicity is an important consideration in drug development. hERG (the human ether-à-go-go–related gene) is a gene that codes for a cardiac potassium ion channel (39). Blockage of hERG can cause cardiac arrhythmia and even sudden death. Therefore, hERG screening is commonly used in drug discovery (40). We compared the hERG blocking ability of bufalin and SI-2 using a well-established in vitro method (41). HEK293 cells that stably express hERG channels (HEK293-hERG) were used as the in vitro system. HEK293-hERG cells have a more negative membrane potential than do wild-type cells, as a result of the potassium channel activity, which can be monitored using a membrane potential-sensitive fluorescent dye DiBAC4(3). Blocking of hERG can increase the membrane potential and thus the fluorescence of DiBAC4(3). HEK293-hERG cells were treated with DiBAC4(3) and bufalin or SI-2 at different concentrations (0.1, 1.0, and 5.0 µM). The fluorescence of DiBAC4(3) was monitored using a plate reader. To offset the nonspecific interactions between the drug and DiBAC4(3), a similar experiment was performed in parental HEK293 cells. After correcting for the background, we found a dramatic fluorescence increase if cells were treated with bufalin, indicating strong cardiotoxicity (Fig. 3A). In contrast, SI-2 did not cause appreciable changes in DiBAC4(3) fluorescence, suggesting that SI-2 cannot block hERG even at 5 µM (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of SI-2 toxicity. (A) In vitro hERG blocking assay. HEK293-hERG and HEK293 (control) cells were incubated with a membrane potential-sensitive fluorescent dye DiBAC4(3) and different concentrations of tested drugs, bufalin, and SI-2. Increase of fluorescence indicates blocking of the hERG channels. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). (B) H&E histological analyses of major organs showed unappreciable chronic toxicity after mice were treated with SI-2 (2 mg/kg, i.p., twice per day) for 5 wk. (Magnification: 200×.)

SI-2 does not cause observable acute or chronic toxicity in vivo. Intraperitoneal or oral administration of SI-2 up to 20 mg/kg (the highest dose tested) did not cause appreciable stress in mice. In addition, continuous treatment of mice with SI-2 (2 mg/kg, twice per day) for 5 wk did not cause any loss of body weight (Fig. 4C) or observable damages to the major organs, including heart, liver, spleen, kidney, lung, and stomach based on histological analyses (Fig. 3B). Based on both the in vitro and in vivo studies of the toxicity profiles, SI-2 appears to be a relatively safe and promising candidate for anticancer drug development.

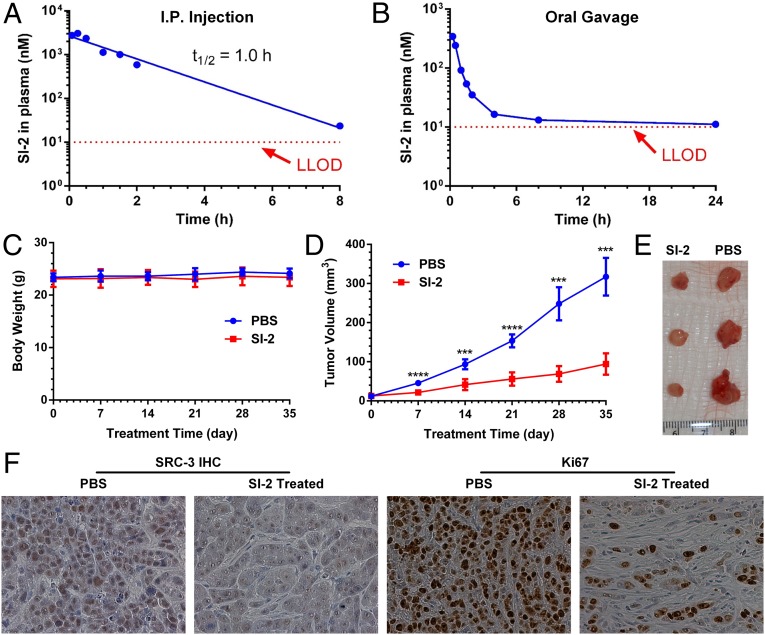

Fig. 4.

Therapeutic efficacy of SI-2 in an orthotopic breast cancer mouse model. (A) PK of SI-2 (20 mg/kg) in CD1 mice (n = 3) via intraperitoneal administration. SI-2 was quantified using LC-MS. The data were fitted into an extravascular noncompartment model. Cmax = 3.0 µM; tmax = 0.25 h; and t1/2 = 1.0 h. (B) PK of SI-2 (20 mg/kg) in CD1 mice (n = 3) via oral gavage. Lower limit of detection (LLOD) is 10 nM. MDA-MB-468 cells were inoculated into the mammary fat pads of SCID mice (female, 5–6 wk). Treatment started 14 d after tumor inoculation. The treatment group was treated with SI-2 (2 mg/kg) twice per day for 5 wk (n = 8). The control group was treated with PBS (n = 6). (C) Body weights and (D) tumor volumes were measured once per week. SI-2 can significantly inhibit tumor growth while not affecting mouse body weights. Data represent mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by Student t test. (E) Representative images of harvested tumors after 5 wk of treatment. (F) SI-2 down-regulates SRC-3 protein levels and reduces the number of Ki-67+ cells. Multiple tumor tissues (n > 3) collected from both the control group (treated with PBS) and the SI-2 treated group were processed and immunohistochemically stained with an anti–SRC-3 antibody, or an anti–Ki-67 antibody. (Magnification: 400×.)

SI-2 Has an Acceptable Pharmacokinetic Profile and Is Orally Available.

We measured the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of SI-2 (20 mg/kg) in CD1 mice (n = 3) via intraperitoneal administration. Twenty microliters of blood were collected at each time point by tail-nicking. The plasma concentration of SI-2 was quantified using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The PK data were fitted into an extravascular noncompartment model (Fig. 4A), affording half-life t1/2 of 1 h, the maximum plasma concentration Cmax of 3.0 µM, and the time to reach the maximum plasma concentration tmax of 0.25 h.

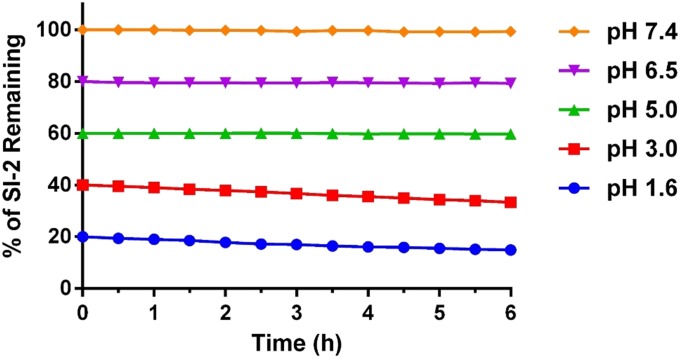

As a drug candidate, it is important for SI-2 to achieve a reasonable oral availability. SI-2 contains a hydrazone group (Fig. 1A), which is potentially sensitive to acid-catalyzed hydrolysis. We tested the stability of SI-2 in different simulated gastric fluids (SGFs) with different pH values to mimic fasted state (pH 1.6) SGF, and early (pH 6.4), middle (pH 5), and late (pH 3) fed-state SGFs (42). A phosphate buffer with the physiological pH 7.4 was also used as a control. We found that SI-2 only degrades slightly (less than 5%) at pH 1.6 and 3.0 within 6 h, and is stable in buffers with pH ≥ 5 (Fig. S5). Next, we measured the PK profile of SI-2 (20 mg/kg) via oral gavage in CD1 mice (n = 3). The PK profile is biphasic (Fig. 4B). We could still detect SI-2 at a 24-h time point, which approaches the lower limit of detection 10 nM. The area under the curve, an indicator of drug exposure, for oral administration is ∼30% of that for intraperitoneal administration. Based on these measurements, SI-2 showed acceptable oral availability and holds promise for drug development.

Fig. S5.

Stability of SI-2 in different SGFs. SI-2 (10 µM) is incubated in SGFs with different pH values to mimic fasted state (pH 1.6) SGF, and early (pH 6.4), middle (pH 5), and late (pH 3) fed-state SGFs. Note: all of the traces are separated by 20 units on the y axis for clarity.

SI-2 Significantly Inhibits Breast Tumor Growth and Reduces SRC-3 Levels in Vivo.

Next, we assessed the antitumor activity of SI-2 in an orthotopic MDA-MB-468 breast cancer mouse model. We determined the dosing schedule based on the PK profile of SI-2. In the PK study (20 mg/kg, i.p.) the plasma concentration of SI-2 is 23 nM at 8 h. Therefore, if a therapeutic dose 2 mg/kg were used, the plasma concentration of SI-2 should be ∼2.3 nM at 8 h, which is close to the IC50 value of SI-2 in MDA-MB-468 cells (3.4 nM). To maintain the plasma concentration of SI-2 above the IC50 value in cancer cells, we decided to treat the mice twice per day. To establish orthotopic breast tumors, 2 × 106 MDA-MB-468 cells were injected into one of the second mammary fat pads of SCID mice (female, 5–6 wk). When tumors became palpable, 14 d after injection, mice were randomized into two groups (n = 6 for the control group; n = 8 for the treatment group). The treatment group was injected with SI-2 (intraperitoneally, 2 mg/kg per dose, two doses per day), whereas the control group received PBS. Tumor lengths and widths and mouse weights were measured once per week. Tumor sizes were calculated by (length × width2)/2. As shown in Fig. 4 D and E, SI-2 treatment can significantly inhibit tumor growth. After 5 wk of treatment, mice in each group were killed and tumors were harvested. To test whether SI-2 can cause SRC-3 down-regulation in vivo, the SRC-3 levels in tumor tissues were measured by immunohistochemistry. As shown in Fig. 4F, the SRC-3 levels (brown color) in SI-2–treated tumor tissues were significantly lower than the PBS treated control group. Ki-67, a cell proliferation marker, also was immunochemically analyzed. Accordingly, the SI-2–treated tumor tissues have dramatically fewer Ki-67+ cells (the cells with brown staining, Fig. 4F). Based on these data, we conclude that SI-2 can significantly inhibit breast tumor growth through inhibition of SRC-3.

Discussion

SRC-3 is a critical coactivator that regulates many transcriptional signaling pathways for cancer formation and proliferation. Although selective estrogen receptor modulators, such as tamoxifen, are first-line treatments for ER+ breast cancer (43, 44), high expression of SRC-3 is associated with recurrence and poor overall survival in both ER+ and TNBC (29). Inhibition of SRC-3 can circumvent endocrine therapy resistance in ER+ breast cancer. Additionally, downregulating SRC-3 can reduce proliferation and migration in TNBC cells (29). Unlike gossypol and bufalin, SI-2 is a drug-like molecule and meets all of the criteria of Lipinski’s rule (31), Veber’s rule (32), and Oprea’s rule (33) for drug-likeness. As a SRC-3 SMI, SI-2 can selectively reduce the transcriptional activities and the protein concentrations of SRC-3 in cells through direct physical interactions with SRC-3, and can selectively induce breast cancer cell death with IC50 values in the low nanomolar range (3–20 nM) but not affect normal cell viability. It should be noted although SI-2 treatment in cancer cells can inhibit the transcriptional activities and protein levels of all three members of the p160 family of steroid receptor coactivators, this inhibitory effect against the SRC family should be advantageous because these three SRC proteins share many redundant functions (45). Furthermore, our in vivo study demonstrated that SI-2 can significantly inhibit primary tumor growth and reduce SRC-3 protein levels in a breast cancer mouse model. In addition, in a toxicology study, we showed that SI-2 caused minimal acute cardiotoxicity based a hERG channel blocking assay and unappreciable chronic toxicity to major organs based on histological analyses.

Our study should not only pave the way to development of “first-in-class” drugs that target oncogenic coactivators and make a potential impact on breast cancer treatment, but also provide an example and a viable strategy to target often “undruggable but important” protein targets without ligand-binding sites. Furthermore, SRC-3 is also an important oncogene in many other types of cancer, including prostate, ovarian, and lung cancer (36). It should be evaluated whether SI-2 can provide survival benefits in these cancers. In addition, deregulation of coactivators is associated with a wide range of human diseases. We will take advantage of our experience in developing SI-2 to develop SMIs for other coactivators to improve human health.

Materials and Methods

The synthetic procedures and characterizations of SI-1 to SI-8 and experimental procedures for SI-2 pharmacokinetics, cell culture assays, immunohistochemistry, and in vivo breast cancer models are described in Supporting Information. See Figs. S6 and S7 for the synthetic procedures of SI-1 and SI-2, respectively. All of the animal studies were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine.

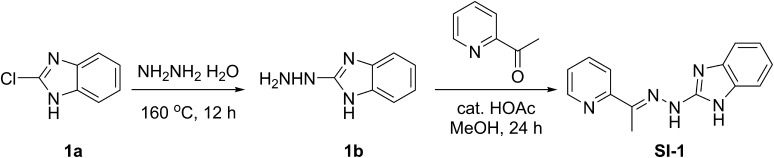

Fig. S6.

Synthetic procedures for SI-1.

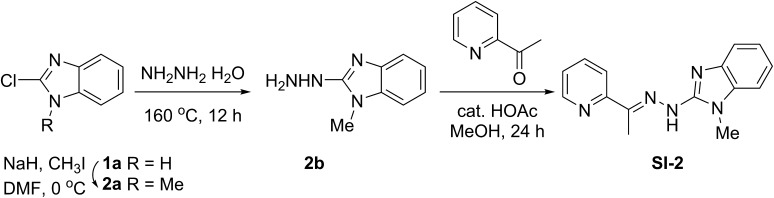

Fig. S7.

Synthetic procedures for SI-2.

SI Materials and Methods

Materials.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Alfa Aesar, unless otherwise specified. All other solvents and reagents were used as obtained without further purification.

Instrumentation.

NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian NMR (1H at 400 MHz spectrometer). Chemical shifts (δ) were given in ppm with reference to solvent signals [1H NMR: DMSO-d6 (2.50)]. UV-Vis measurements were performed in 10 × 10-mm quartz cuvettes with a Cary 60 UV-Vis Spectrometer. Flash chromatography was performed on a Teledyne ISCO CombiFlash Rf 200. Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry was measured on an Agilent Mass Spectrometer (6130 single quad).

Animal Studies.

All of the animal studies were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine. All of the mice were killed in a CO2 chamber. In addition, any animals that showed loss of mobility, weight loss, or other symptoms related to tumor growth were killed. Tumors were not allowed to reach >20% of body weight or ulcerate. All animals were killed and tumors were harvested at no more than 1,000 mm3 in volume. In addition, any animal that displayed immobility, huddled posture, inability to eat, ruffled fur, self-mutilation, vocalization, wound dehiscence, hypothermia, or greater than 20% weight loss were killed as per Baylor College of Medicine guidelines.

Synthesis of SI-1

Compounds SI-1 was synthesized according to a previously reported procedure (Fig. S6) (46). 2-Chloro-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (916 mg, 6 mmol) was heated at 160 °C in a sealed tube with 4 mL of hydrazine hydrate for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, the precipitate was filtered and washed several times with water and dried to give compound 1b (683 mg, yield 77%) as a gray solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.00 (br s, 1H), 7.77 (s, 1H), 7.30–6.93 (m, 2H), 6.95–6.66 (m, 2H), 4.42 (s, 2H).

A mixture of 2-acetylpyridine (0.5 mL, 4.39 mmol) and the hydrazine 1b (650 mg, 4.39 mmol) in methanol containing three drops of acetic acid was heated to reflux for 24 h. The product was precipitated at 5 °C overnight and filtered. The crude product was recrystallized from ethyl acetate/hexanes to give compound SI-1 (860 mg, 78%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.52 (s, 1H), 10.86 (br s, 1H), 8.58–8.52 (m, 1H), 8.48 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.89–7.72 (m, 1H), 7.36–7.30 (m, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.05–6.92 (m, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H). MS (ESI): m/z 252.1 [M+1]+.

Synthesis of SI-2

Compounds SI-2 was synthesized according to a previously reported procedure (Fig. S7) (46). To a solution of 2-chloro-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (916 mg, 6 mmol) in 10 mL of dry DMF, which was cooled to 0 °C, NaH (240 mg, 10.8 mmol) was added carefully in small portions. The mixture was stirred for another 15 min at this temperature. Then, methyl iodide (0.41 mL, 6.6 mmol) was added under continuous stirring for an additional 15 min. When TLC showed full conversion, the mixture was poured into 60 mL of water and a white solid precipitated, collected by filtration, and dried in vacuo to obtain 2a 650 mg (65%) of pure product as white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.62–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.34–7.27 (m, 1H), 7.27–7.20 (m, 1H), 3.80 (s, 3H).

Compound 2b was synthesized using the same procedure for 1b (230 mg, 36%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.79 (s, 1H), 7.29–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.20–7.13 (m, 1H), 7.01–6.91 (m, 2H), 4.26 (s, 2H), 3.46 (s, 3H).

A mixture of 2-acetylpyridine (0.16 mL, 1.418 mmol) and the hydrazine 2b (230 mg, 1.418 mmol) in methanol containing two drops of acetic acid was reacted at room temperature for 72 h. The solvent was removed. Recrystallization from methanol afforded SI-2 (290 mg, 77%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.06 (s, 1H), 8.55–8.50 (m, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.79–7.72 (m, 1H), 7.30–7.23 (m, 1H), 7.14–7.08 (m, 1H), 7.14–7.08 (m, 1H), 7.05–6.97 (m, 2H), 3.47 (s, 3H), 2.41 (s, 3H). MS (ESI): m/z 266.1 [M+1]+, 288.1 [M+Na]+.

Syntheses of SI-3 to SI-8

The syntheses of SI-3 to SI-8 followed a similar procedure as described for SI-2.

SI-3: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.78 (s, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.08–7.03 (m, 1H), 6.82 (s, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.10–6.00 (m, 2H), 3.50 (s, 3H), 2.22 (s, 3H).

SI-4: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.10–6.96 (m, 5H), 6.87 (s, 1H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.52 (s, 3H), 2.54 (s, 3H).

SI-5: [Z, E mixture (4:6)]: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.77 (s, 0.6 × 1H), 9.44 (s, 0.4×Z1H), 7.66 (s, 1H), 7.23–7.18 (m, 1H), 7.15–6.91 (m, 4H), 3.55 (s, 0.6 × 3H), 3.43 (s, 0.4 × 3H), 2.50 (s, 3H).

SI-6: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.79 (br s, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.18–6.95 (m, 4H), 3.57 (s, 3H), 2.57 (s, 3H).

SI-7: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.01 (s, 1H), 7.44 (s, 1H), 7.10–6.91 (m, 4H), 6.70 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 6.47–6.38 (m, 1H), 3.60 (s, 3H), 2.42 (s, 3H).

SI-8: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.33 (br s, 1H), 7.25–7.19 (m, 2H), 7.15–6.96 (m, 5H), 3.62 (s, 3H), 2.48 (s, 3H).

Stability of SI-2 in Simulated Gastric Fluids

A series of SGFs with different pH values (1.6, 3.0, 5.0, 6.5, and 7.4) were prepared according to the literature (42). SI-2 (10 µM) was dissolved in the SGFs and the stability of SI-2 was monitored using a UV-vis spectrometer. The normalized absorbance of SI-2 at 350 nm was plotted at different time points.

Pharmacokinetics of SI-2

SI-2 (20 mg/kg, i.p.) were injected into CD-1 mice (n = 3). Twenty microliters of blood was collected via the tail vein at 5, 15, 30 min, and 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. The proteins and cells in blood were precipitated by mixing the blood with an equal volume of acetonitrile, followed by centrifugation to remove the precipitates. The supernatants were used for LC-MS analyses. To calibrate the quantification of SI-2, solutions of each analyte were prepared by mixing acetonitrile with plasma purified from blood samples. Nine quality control (QC) samples at 10 ng/mL, 20 ng/mL, 50 ng/mL, 100 ng/mL, 200 ng/mL, 500 ng/mL, 1,000 ng/mL, 2,000 ng/mL, and 5,000 ng/mL of plasma were prepared independently of those used for the calibration curves. QC samples were prepared on the day of analysis in the same way as the calibration standards. Standards, QC samples, and unknown samples were injected into LC-MS for quantitative analysis. The PK parameters of SI-2 were analyzed using PK Solver Excel Add-in (47). The PK trace was fitted into a noncompartmental extravascular model.

Oral Bioavailability of SI-2

SI-2 (20 mg/kg) was administered into CD-1 mice (n = 3) via oral gavage. Twenty microliters of blood was collected via the tail vein at 15, 30 min, and 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. The calibration and quantification of SI-2 is the same as described above for intraperitoneal administration. The PK parameters were also analyzed using the PK Solver Excel Add-in (47). The PK trace was fitted into a noncompartmental extravascular model.

Measurement of Physical Interactions Between SI-2 and SRC-3

The GST fusion protein of the SRC-3 RID was expressed and purified (35). Fluorescence spectrometric measurements were performed using an Agilent Cary Eclipse Fluorescence spectrophotometer. A total of 1.5 μM of GST SRC-3 RID was placed in a fluorescence cuvette and excited with UV light at 278 nm with a 2-nm bandwidth, and the emission spectra of the tryptophan intrinsic fluorescence were recorded from 320 to 500 nm with a bandwidth of 4 nm. Subsequently, aliquots of concentrated SI-2 in DMSO were added to SRC-3 RID solution to achieve the SI-2 final concentrations at 0.5, 2, 50 and 200 nM. The intrinsic fluorescence of SRC-3 RID was measured in the presence of different concentrations of SI-2 to determine the physical interactions between SI-2 and SRC-3. The volume of the aliquots was maintained below 5% of the total sample volume to minimize the dilution effects. A β-lactamase was also used to substitute SRC-3 RID to determine the nonspecific interactions between SI-2 and proteins.

Cell Culture

Breast cancer cell lines MCF-7, MDA-MB-468, BT-20, BT-474, SUM-159PT were obtained from ATCC. LM3-3 cell line was isolated from a lung metastasis, which is derived from a MDA-MB-231-LM2 xenograft tumor in the mammary fat pad of a SCID mouse (48). MCF-7, LM3-3, BT-20, and BT-474 cell lines were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS. MDA-MB-468 was grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% FBS. SUM159PT was grown in Ham’s F-12 medium plus 5% (vol/vol) FBS, 5 μg/mL of insulin, and 1 μg/mL of hydrocortisone. All cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator filled with 5% (vol/vol) CO2 at 37 °C. Primary hepatocytes were isolated from an adult female CD-1 mouse through collagenase perfusion as described previously, and maintained in M199 medium with 10% (vol/vol) FBS (49).

Cell Cytotoxicity Assays

Breast cancer cells (4,000–7,000 cells per well) were seeded into 96-well plates containing 100 μL of medium supplemented with 10% FBS. On the next day, when cells reached 70–80% confluence, SI-2 was added to achieve a series of titrations (0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500, and 1,000 nM). After 72 h of SI-2 treatment, cell viability was measured by MTT assay. For statistical significance, six parallel repeats were tested in each SI-2 titration. Relative cell viabilities, referred to untreated control cells, were plotted using Graphpad Prism. The IC50 values, reflecting SI-2 cytotoxicity, were calculated, based on a Hill–Slope model.

Western Blotting Assays

Whole-cell proteins of breast cancer cells were extracted with RIPA lysis buffer, containing 25 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). The cell debris was precipitated and removed through 14,000 × g centrifugation at 4 °C. The concentration of proteins in supernatant was measured by a Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amount of total proteins from each sample was loaded on an 8% SDS/PAGE gel. The electrophoretically separated proteins on a SDS/PAGE gel were transferred to a PVDF membrane. Anti-SRC-3 (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 2126), anti–CARM-1 (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 3379), and anti-actin (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 8457) antibodies were used to probe the membranes.

Apoptosis Assay

MDA-MB-468 cells were seeded in six-well plates for 0.4 × 106 per well. Next day, cells were treated with different concentrations of SI-2 (12, 25, 50, 100, and 200 nM), or Etoposide (0, 3, 6, 12, 25, and 50 µM). After 24 h of treatment, a set of cells were collected for measuring the PARP cleavage (an indicator of cell apoptosis) by Western blotting. Another parallel set of cells were collected for detecting the exposed phosphatidylserine by an Annexin-V FITC staining (BD Biosciences Cat# 556547), as well as measuring the permeability for propidium iodide, through flow cytometry analysis. A minimum of 10,000 cells of each sample and three repeats for each drug treatment were analyzed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer. The acquired cytometric signals were further analyzed and presented using the FlowJo software.

Immunohistochemistry

Fresh mouse tumor tissues were fixed with formalin and then embedded in paraffin for subsequent sectioning. Tissue slices were deparaffinized by sequentially soaking in in xylene, ethanol, and water. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the slides in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 30 min. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by 3% (vol/vol) hydrogen peroxide solution. To reduce nonspecific probing, slices was blocked with 2.5% (wt/vol) normal serum. Primary antibodies, anti-SRC-3 (Mouse source, BD Biosciences Inc., Cat# 611104; 1:400 dilution) and anti–Ki-67 (Rabbit source, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#9027; 1:10,000 dilution) were used to incubate with slices at 4 °C for overnight. Slices were then stained with HRP-polymer conjugated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Cat#7401 for rabbit source antibody, Cat#MP-2400 for mouse source antibody). To visualize the immunostaining, the slices were reacted with fresh DAB solution (Dako, Cat# K3468). After ideal staining was observed under microscope, the DAB was rinsed off by water. Nuclear counterstain was performed by immersing slides in Mayer’s Hematoxylin, and bluing reagent.

hERG Activity Assay

hERG activity was measured through a fluorescent dye DiBAC4(3), the distribution of which across cell membrane depends on the membrane potential (50). The more hERG channel is blocked, the more DiBAC4(3) enter into cells. HEK293-hERG and HEK293 (control) cells, 4,000 cells per well, were seeded in 96-well plates. On the next day, cells were treated with SI-2, Bufalin for 24 h. Then, the cell culture medium was replaced with PBS plus Hepes (10 mM, pH7.2) buffer. DiBAC4(3) was added to cells with a final concentration of 4 µM. After 3 h of incubation at 37 °C, the fluorescence signals were measured by a plate reader (BioTek, Synergy Hybrid Reader) with set-up: excitation wavelength 485 nm, emission wavelength 520 nm. For statistical significance, six parallel repeats were tested.

Therapeutic Efficacy of SI-2 in an Orthotopic TNBC Mouse Model

To establish orthotopic breast tumors, 2 × 106 of MDA-MB-468 cells were injected into one of the second mammary fat pads of immunodeficient SCID mice (Charles River Laboratories; female, 6–7 wk, n = 8 for the treatment group, n = 6 for the PBS group). When tumors became palpable, 14 d after injection, mice were randomized into two groups. The treatment group received an intraperitoneal injection of SI-2, 2 mg/kg per dose, two doses per day, for a continuous 35 d, whereas the control group received PBS. Tumor lengths and widths were measured once per week. Tumor sizes were calculated by: length × width × width/2.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01GM115622 (to J.W.), HD076596 (to D.M.L.), DK059820 (to B.W.O.), and R01CA112403 (to J.X.); Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Grants R1104 (to J.W.), RP100348 and RP101251 (to B.W.O.), and RP120732-P5 (to J.X.); Welch Foundation Grant Q-1798 (to J.W.); Susan G. Komen Foundation Grant PG12221410 (to B.W.O.); the Clayton Foundation and the Dunn Foundation (B.W.O.); the Integrative Molecular and Biomedical Sciences (IMBS) Program (NIH 5 T32 GM008231) (to M.Z.); the Center for Comparative Medicine, the Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core, the Center for Drug Discovery, and the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine; and the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: J.C., T.P., J.X., D.M.L., B.W.O., and J.W. are coinventors of a patent application related to this work. T.P., J.X., D.M.L., B.W.O., and J.W. are cofounders and hold stock in Coregon, Inc., which is developing steroid receptor coactivator inhibitors for clinical use.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1604274113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wells JA, McClendon CL. Reaching for high-hanging fruit in drug discovery at protein-protein interfaces. Nature. 2007;450(7172):1001–1009. doi: 10.1038/nature06526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arkin MR, Wells JA. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: Progressing towards the dream. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(4):301–317. doi: 10.1038/nrd1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lo Conte L, Chothia C, Janin J. The atomic structure of protein-protein recognition sites. J Mol Biol. 1999;285(5):2177–2198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheng C, Dong G, Miao Z, Zhang W, Wang W. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting protein-protein interactions by small-molecule inhibitors. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(22):8238–8259. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00252d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clackson T, Wells JA. A hot spot of binding energy in a hormone-receptor interface. Science. 1995;267(5196):383–386. doi: 10.1126/science.7529940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson AB, O’Malley BW. Steroid receptor coactivators 1, 2, and 3: critical regulators of nuclear receptor activity and steroid receptor modulator (SRM)-based cancer therapy. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;348(2):430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lonard DM, O’Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: Modulators of pathology and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(10):598–604. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lonard DM, O’Malley BW. SRC-3 transcription-coupled activation, degradation, and the ubiquitin clock: Is there enough coactivator to go around in cells? Sci Signal. 2008;1(13):pe16. doi: 10.1126/stke.113pe16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lonard DM, O’Malley BW. The expanding cosmos of nuclear receptor coactivators. Cell. 2006;125(3):411–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pondugula SR, Mani S. Pregnane xenobiotic receptor in cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic response. Cancer Lett. 2013;328(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oñate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270(5240):1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang Cy, et al. Dissection of the LXXLL nuclear receptor-coactivator interaction motif using combinatorial peptide libraries: Discovery of peptide antagonists of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(12):8226–8239. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris JD, et al. Peptide antagonists of the human estrogen receptor. Science. 1999;285(5428):744–746. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold LA, et al. Discovery of small molecule inhibitors of the interaction of the thyroid hormone receptor with transcriptional coregulators. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(52):43048–43055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506693200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan F, et al. Identification of verrucarin a as a potent and selective steroid receptor coactivator-3 small molecule inhibitor. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, et al. Bufalin is a potent small-molecule inhibitor of the steroid receptor coactivators SRC-3 and SRC-1. Cancer Res. 2014;74(5):1506–1517. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, et al. Small molecule inhibition of the steroid receptor coactivators, SRC-3 and SRC-1. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(12):2041–2053. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman RA, Yang P, Pawlus AD, Block KI. Cardiac glycosides as novel cancer therapeutic agents. Mol Interv. 2008;8(1):36–49. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prassas I, Diamandis EP. Novel therapeutic applications of cardiac glycosides. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(11):926–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mijatovic T, et al. The cardenolide UNBS1450 is able to deactivate nuclear factor kappaB-mediated cytoprotective effects in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(2):391–399. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, et al. Digoxin and other cardiac glycosides inhibit HIF-1alpha synthesis and block tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(50):19579–19586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809763105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye J, Chen S, Maniatis T. Cardiac glycosides are potent inhibitors of interferon-β gene expression. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(1):25–33. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menger L, et al. Cardiac glycosides exert anticancer effects by inducing immunogenic cell death. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(143):143ra99. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Platz EA, et al. A novel two-stage, transdisciplinary study identifies digoxin as a possible drug for prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Discov. 2011;1(1):68–77. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huh JR, et al. Digoxin and its derivatives suppress TH17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt activity. Nature. 2011;472(7344):486–490. doi: 10.1038/nature09978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogawa H, Shinoda T, Cornelius F, Toyoshima C. Crystal structure of the sodium-potassium pump (Na+,K+-ATPase) with bound potassium and ouabain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(33):13742–13747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907054106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manna SK, Sah NK, Newman RA, Cisneros A, Aggarwal BB. Oleandrin suppresses activation of nuclear transcription factor-kappaB, activator protein-1, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Cancer Res. 2000;60(14):3838–3847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frese S, et al. Cardiac glycosides initiate Apo2L/TRAIL-induced apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells by up-regulation of death receptors 4 and 5. Cancer Res. 2006;66(11):5867–5874. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song X, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-3 (SRC-3/AIB1) as a novel therapeutic target in triple negative breast cancer and its inhibition with a phospho-bufalin prodrug. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lonard DM, Nawaz Z, Smith CL, O’Malley BW. The 26S proteasome is required for estrogen receptor-alpha and coactivator turnover and for efficient estrogen receptor-alpha transactivation. Mol Cell. 2000;5(6):939–948. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1-3):3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veber DF, et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J Med Chem. 2002;45(12):2615–2623. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hann MM, Oprea TI. Pursuing the leadlikeness concept in pharmaceutical research. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8(3):255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ertl P, Rohde B, Selzer P. Fast calculation of molecular polar surface area as a sum of fragment-based contributions and its application to the prediction of drug transport properties. J Med Chem. 2000;43(20):3714–3717. doi: 10.1021/jm000942e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu RC, Feng Q, Lonard DM, O’Malley BW. SRC-3 coactivator functional lifetime is regulated by a phospho-dependent ubiquitin time clock. Cell. 2007;129(6):1125–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J, Wu RC, O’Malley BW. Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(9):615–630. doi: 10.1038/nrc2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tien JCY, Xu J. Steroid receptor coactivator-3 as a potential molecular target for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(11):1085–1096. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.718330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qin L, et al. The AIB1 oncogene promotes breast cancer metastasis by activation of PEA3-mediated matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) and MMP9 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(19):5937–5950. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00579-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou PZ, Babcock J, Liu LQ, Li M, Gao ZB. Activation of human ether-a-go-go related gene (hERG) potassium channels by small molecules. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32(6):781–788. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowlby MR, Peri R, Zhang H, Dunlop J. hERG (KCNH2 or Kv11.1) K+ channels: Screening for cardiac arrhythmia risk. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9(9):965–970. doi: 10.2174/138920008786485083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerns E, Di L. Drug-Like Properties: Concepts, Structure Design and Methods: From ADME to Toxicity Optimization. Academic; Burlington, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marques MR, Loebenberg R, Almukainzi M. Simulated biological fluids with possible application in dissolution testing. Dissolut Technol. 2011;18(3):15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordan VC. Tamoxifen: A most unlikely pioneering medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(3):205–213. doi: 10.1038/nrd1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jordan VC. Selective estrogen receptor modulation: Concept and consequences in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(3):207–213. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu J, Li Q. Review of the in vivo functions of the p160 steroid receptor coactivator family. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(9):1681–1692. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hofmann J, Heinisch G, Easmon J, Purstinger G, Fiebig H-h. 2003. Heterocyclic hydrazones for use as anti-cancer agents. US Patent 20,030,166,658.

- 47.Zhang Y, Huo M, Zhou J, Xie S. PKSolver: An add-in program for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis in Microsoft Excel. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2010;99(3):306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minn AJ, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436(7050):518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu T, et al. Aberrantly elevated microRNA-34a in obesity attenuates hepatic responses to FGF19 by targeting a membrane coreceptor β-Klotho. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(40):16137–16142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205951109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dorn A, et al. Evaluation of a high-throughput fluorescence assay method for HERG potassium channel inhibition. J Biomol Screen. 2005;10(4):339–347. doi: 10.1177/1087057104272045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]