Summary

Interleukin (IL)-17-producing helper T cells (Th17 cells) play an important role in autoimmune diseases. However, not all Th17 cells induce tissue inflammation or autoimmunity. Th17 cells require IL-23 receptor (IL-23R) signalling to become pathogenic. The transcriptional mechanisms controlling the pathogenicity of Th17 cells and IL-23R expression are unknown. Here, we demonstrate that the canonical Notch signalling mediator RBPJ is a key driver of IL-23R expression. In the absence of RBPJ, Th17 cells fail to upregulate IL-23R, lack stability, and do not induce autoimmune tissue inflammation in vivo whereas overexpression of IL-23R rescues this defect and promotes pathogenicity of RBPJ-deficient Th17 cells. RBPJ binds and transactivates the Il23r promoter and induces IL-23R expression and represses anti-inflammatory IL-10 production in Th17 cells. We thus identify Notch signalling to regulate the development of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Th17 cells by reciprocally regulating IL-23R and IL-10 expression.

Keywords: Th17 cells, pathogenicity, IL-23R, RBPJ, Notch

eTOC blurb

Meyer zu Horste et al. find that RBPJ promotes the pathogenicity of Th17 cells by directly enhancing expression of the interleukin-23 receptor and repressing interleukin-10 production.

Introduction

Interleukin (IL)-17-producing helper T cells (Th17 cells) have been identified as a distinct subset of effector CD4+ T cells and are considered as critical drivers of autoimmune tissue inflammation (Bettelli and Kuchroo, 2005; Korn et al., 2009). Differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th17 cells is achieved with the cytokines transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and IL-6 (Bettelli et al., 2006). This cytokine combination, however, generates Th17 cells, that co-produce IL-10 together with IL-17 and do not induce autoimmunity (Lee et al., 2012; McGeachy et al., 2007) and have therefore been called non-pathogenic Th17 cells. To acquire the ability to induce autoimmunity in vivo, IL-17 producing T cells need to either be re-stimulated with IL-23 (McGeachy et al., 2009) or be generated with alternative cytokine combinations triggering IL-23 receptor (IL-23R) expression and signalling such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23 (Ghoreschi et al., 2010) or TGF-β3 and IL-6 (Lee et al., 2012). IL-23R controls the production of a proinflammatory transcriptional module in Th17 cells (Lee et al., 2012) including many essential effector cytokines (Codarri et al., 2011; El-Behi et al., 2011). IL-23R is thus a key determinant of the pathogenicity of Th17 cells and of autoimmunity in general. Understanding the mechanism by which IL-23R regulates the functional phenotype of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Th17 cells and how this balance is transcriptionally regulated is therefore critical for the selective inhibition of pathogenic Th17 cells in human autoimmune diseases.

Differentiation of Th17 cells is transcriptionally controlled by the lineage defining transcription factor RORγt (Ivanov et al., 2006; Xiao et al., 2014) and the transcriptional networks controlling Th17 cell differentiation have recently been identified in large-scale transcriptomic analyses (Ciofani et al., 2012; Yosef et al., 2013). Our study predicted that Notch signalling and RBPJ, a downstream regulator of Notch signalling, were two of the 22 major nodes that positively regulated the development of Th17 cells (Yosef et al., 2013). This is consistent with previous studies which demonstrated that pharmacological and antibody-mediated inhibition of Notch ameliorated Th17-dependent autoimmune disease models (Bassil et al., 2011; Jurynczyk et al., 2008; Keerthivasan et al., 2011; Reynolds et al., 2011). Despite these detailed transcriptomic data, the molecular mechanism by which Notch regulates Th17 development has not been identified. In addition, what subtype of Th17 cells (pathogenic or non-pathogenic) is regulated by Notch signalling has not been addressed.

Here, we demonstrate that the canonical Notch signalling molecule RBPJ in Th17 cells regulates the development of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Th17 cells. We show that RBPJ directly promotes the expression of IL-23R by binding and trans-activating the Il23r promoter and repressing anti-inflammatory IL-10 production in Th17 cells. Consistent with this observation is that RBPJ-deficient Th17 cells show a non-pathogenic Th17 transcriptional profile and RBPJ-deficiency in Th17 cells protects mice from the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) and IL-23R overexpression rescues this defect. We have therefore identified a transcription factor, which controls the generation of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Th17 cells by directly driving IL-23R expression and repressing production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.

Results

RBPJ is required for the pathogenicity of Th17 cells

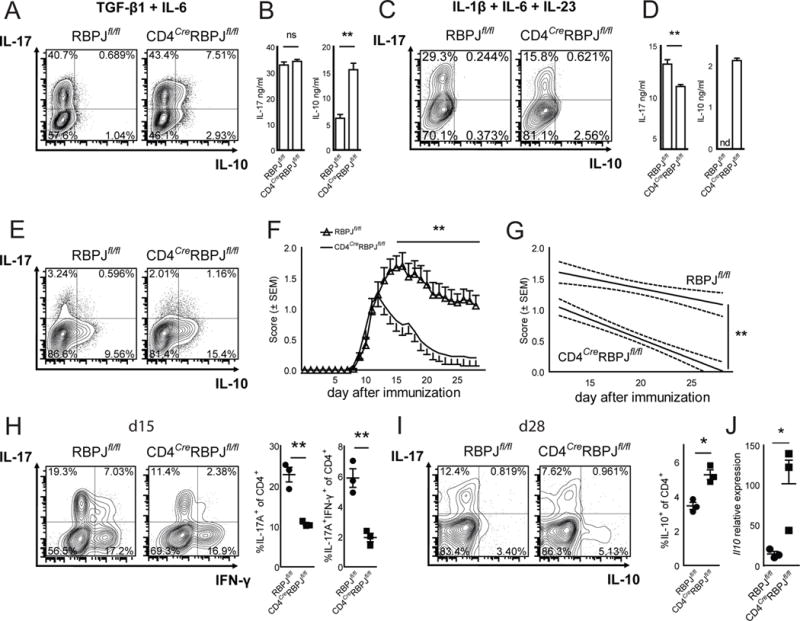

IL-23R is essential for the pathogenicity of Th17 cells but its transcriptional control is unknown. We previously identified Notch1 and RBPJ, which form the Notch signalling pathway, as predicted positive regulators of Th17 cell differentiation (Yosef et al., 2013). However, the exact role of Notch signalling in Th17 cells was not analyzed. In a time-course expression analysis, RBPJ had high expression and was continuously upregulated in Th17 cells (Fig. S1A–C). We therefore generated CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice and found that RBPJ-deficiency in T cells did not affect Th17 differentiation in the presence of TGF-β1 and IL-6, a condition that induces non-pathogenic Th17 cells independent from IL-23 (Lee et al., 2012) (Fig. 1A). Under these non-pathogenic conditions, CD4CreRBPJfl/fl Th17 cells instead showed a dramatic increase in IL-10 production (Fig. 1A, B). When differentiated with IL-1β + IL-6 + IL-23, which generates pathogenic Th17 cells dependent on IL-23 (Ghoreschi et al., 2011), naïve CD4CreRBPJfl/fl cells showed a significant decrease in IL-17 expression (Fig. 1C, D). In addition, such pathogenic Th17 cells from CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice began to produce IL-10 (Fig. 1D), which is normally not observed under these conditions. Also, memory T cells from the CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice, which were stimulated with IL-23 showed an increase in IL-10 (Fig. 1E), although IL-23 suppresses IL-10 production from wildtype Th17 cells (Lee et al., 2012; McGeachy et al., 2009). Lack of RBPJ thus affected the ability of Th17 cells to adequately respond to IL-23.

Figure 1. RBPJ in T cells maintains pathogenicity of Th17 cells.

(A) Naïve CD4+CD62LhighCD44lowCD25− T cells were sorted from RBPJflox/flox and CD4CreRBPJflox/flox mice, differentiated with TGF-β1 and IL-6, and analyzed by intracellular cytokine staining after 4 days. (B) Cytokine ELISA of cultures described in A. (C) Naïve T cells were differentiated with IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23. (D) Cytokine ELISA of cultures described in C. (E) CD4+CD62LlowCD44highCD25− memory T cells were sorted from RBPJflox/flox and CD4CreRBPJflox/flox mice and cultured with IL-23 for 5 days and stained for intracellular cytokines. One representative out of five independent experiments is shown in A–E; nd not detected. (F) Active EAE was induced in RBPJflox/flox (n = 26) and CD4CreRBPJflox/flox (n = 26) mice by subcutaneous immunization with 100μg of MOG35–55 peptide in complete Freund’s adjuvant together with intraperitoneal injection of pertussis toxin (200 ng) on day 0 and 2. (G) Regression analysis of the clinical scores observed between day 12 and day 28. (H) CNS infiltrating mononuclear cells were extracted and stained for intracellular cytokines at day 15 after immunization (d15). The percentage of CNS infiltrating cytokine producing CD4+ cells was calculated. (I) The cytokine production by CNS infiltrating CD4+ cells was assessed at d28 and the proportion of IL-10 producing CD4+ T cells was calculated. (J) CNS infiltrating CD4+ T cells were sorted from RBPJflox/flox (n = 3) and CD4CreRBPJflox/flox (n = 3) mice and relative Il10 expression was measured by qPCR using GAPDH as housekeeping gene. Results are summed from three independent experiments in F–I with three indidivual mice analyzed per group in H and I. See also Figure S1.

To test for the in vivo relevance of these findings, we induced the autoimmune disease model EAE in CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice using myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)35–55 peptide. CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice developed reduced peak severity and had faster recovery from EAE while disease onset was unchanged (Fig. 1F, G) consistent with RBPJ-deficiency affecting the generation of pathogenic Th17 cells. We isolated CNS infiltrating mononuclear cells from mice with EAE (Fig. S1D) and found a decrease in IL-17A producing and in IL-17A/IFN-γ double producing CD4+ T cells in the CNS of CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice at the peak of EAE (Fig. 1H) and IL-17A+IFN-γ+ T cells are generally considered to be pathogenic in EAE (Abromson-Leeman et al., 2009). There was no effect on IFN-γ producing single positive T cells and on the production of other cytokines in the CNS at early time points (Fig. S1D). At the time of recovery, production of anti-inflammatory IL-10 by CD4+ T cells in the CNS in CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice was increased (Fig. 1I, J) while IL-23 dependent early generation of Th17 cells in draining lymph nodes in CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice was reduced (Fig. S1E). We thus hypothesized that RBPJ promotes the pathogenicity of Th17 cells by altering their ability to respond to pro-inflammatory IL-23 and/or by repressing the production of anti-inflammatory IL-10.

RBPJ is known to have a role in the differentiation of other T helper cell (Amsen et al., 2009) and accordingly we observed an increased differentiation of Th1 cells (Fig. S1F) and decreased generation of iTregs (Fig. S1G) in CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice. To circumvent these non-Th17 derived effects, we crossed RBPJfl/fl mice to IL17ACre mice to delete RBPJ only in IL-17A producing cells. The differentiation of Th1 (Fig. S2A) and iTreg (Fig. S2B) cells was unchanged in IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl cells supporting that the loss of RBPJ is indeed restricted to IL-17 producing T cells in this mouse line.

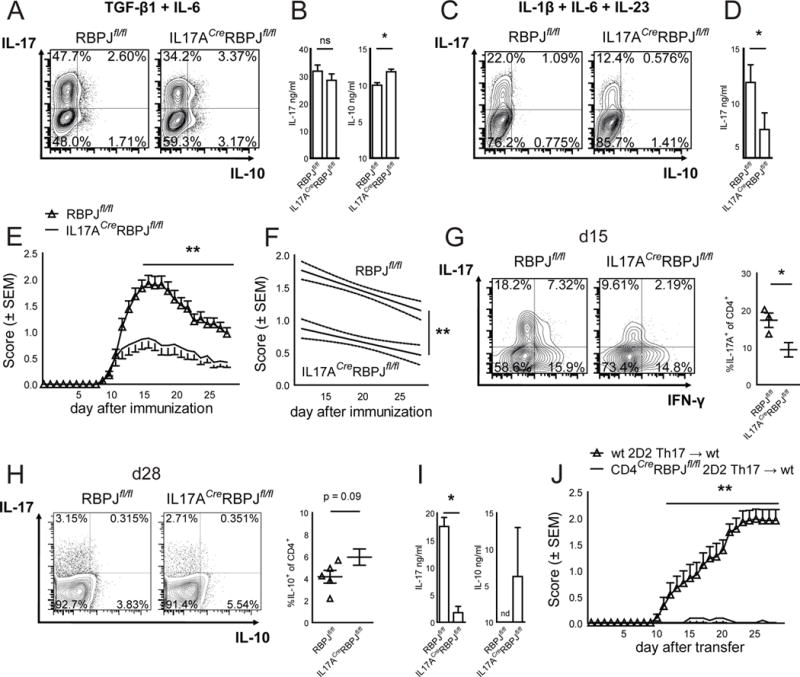

When differentiating IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl cells under non-pathogenic Th17 conditions (TGF-β1 + IL-6), RBPJ was indeed deleted (Fig. S2C) and we observed an increase in IL-10 production but little effect on IL-17 production (Fig. 2A, B). In contrast, under pathogenic differentiation conditions (IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23), which require the effect of IL-23R signalling, IL-17A production was significantly reduced in IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl cells (Fig. 2C, D) while IL-10 protein was not detectable (data not shown). After immunization with MOG35–55, IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl mice developed less severe EAE than wildtype controls (Fig. 2E, F) with a significant reduction in peak EAE severity but no change in disease onset. At the peak of EAE, fewer CNS infiltrating CD4+ cells produced IL-17 and IL-17/IFN-γ concurrently (Fig. 2G) in IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl mice and there was a trend towards more IL-10+ CD4+ T cells at recovery, which did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2H). Production of other cytokines was unchanged (Fig. S2D). Moreover, the IL-23 dependent generation of Th17 cells was affected in the periphery (Fig S2E) and IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl cells produced more IL-10 at recovery (Fig. 2I). We next co-cultured IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl cells with congenically marked wildtype cells and found a marked reduction in pathogenic Th17 cell differentiation only in CD45.2+ IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl cells in comparison to the cocultured CD45.1+ wildtype cells arguing for a cell-intrinsic effect of RBPJ in Th17 cells (Fig. S2F). Thus, Th17 cell-restricted RBPJ-deficiency also impairs their response to pro-inflammatory IL-23 and their pathogenicity.

Figure 2. RBPJ is required in Th17 cells to maintain their pathogenicity.

(A) Naïve CD4+CD62LhighCD44lowCD25− T cells were sorted from RBPJflox/flox and IL17ACreRBPJflox/flox mice, differentiated with TGF-β1 and IL-6, and stained for intracellular cytokines after 4 days. (B) Cytokine ELISA of cultures described in A. (C) Naïve T cells were differentiated in vitro with IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 and analyzed as in A. (D) Cytokine ELISA of cultures described in C. One representative of five independent experiments is shown in A–D. (E) RBPJflox/flox (n = 43) and IL17ACreRBPJflox/flox (n = 28) mice were immunized subcutaneously with MOG35–55 peptide emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant with intraperitoneal injections of pertussis toxin. (F) Regression analysis of the clinical scores observed between day 12 and day 28. Data in E and F are summed from five independent experiments. (G) CNS infiltrating cells were extracted and analyzed by intracellular cytokine staining at day 15 after immunization (d15). (H) CNS infiltrating lymphocytes were stained for intracellular cytokines at d28 and the percentage of IL-10+ CD4+ cells was calculated. (I) Draining lymph node cells of mice at d15 were restimulated in vitro with 10μg/ml MOG35–55 peptide and IL-23 for five days. Cytokine concentrations were measured by ELISA, nd not detected. Data in G–I are summed from three independent experiments with three to five mice per group. See also Figure S2. (J) Naïve CD4+CD62LhighCD44lowCD25− T cells were sorted from wildtype 2D2 and CD4CreRBPJfl/fl2D2 mice and differentiated in vitro with TGF-β1, IL-6 and IL-23 and after 7 days of culture 5*106 cytokine producing T cells were intravenously injected into C57BL/6 wildtype recipients.

IL-17A is also expressed by γδ T cells and innate lymphoid cells. To exclude the contribution of such cell types and to address the role of RBPJ specifically in pathogenic Th17 cells in vivo, we crossed CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice to 2D2 mice, which express a MOG35–55-specific T cell receptor (TCR) transgene (Bettelli et al., 2003). Th17 cells differentiated in vitro under pathogenic Th17 conditions from CD4CreRBPJfl/fl2D2 mice, were unable to induce EAE upon adoptive transfer in contrast to wildtype 2D2 Th17 cells (Fig. 2J) although their IL-17 production before transfer was unchanged (Fig. S2G). Our data obtained with this targeted deletion of RBPJ thus indicate that RBPJ is required specifically for the differentiation of pathogenic Th17 cells generated with IL-23, and that loss of RBPJ results in an increase of anti-inflammatory IL-10 and loss of pathogenicity in vivo. RBPJ-deficiency thus causes the generation of non-pathogenic Th17 cells even under pathogenic Th17-differentation conditions.

Notch signalling controls various aspects of CD4+ T cell function including chemokine receptor expression (Reynolds et al., 2011) and viability of memory T cells (Helbig et al., 2012; Maekawa et al., 2015). We did not find evidence for an altered expression of Ccr6 (Fig. S3A) or an altered survival of RBPJ-deficient Th17 cells in vitro (Fig. S3C) or in vivo (Fig. S3D–E) arguing for a specific effect of RBPJ on the pathogenicity of Th17 cells under IL-23 dependent Th17 differentiation conditions. We next investigated the mechanism of how RBPJ enhanced pathogenicity of Th17 cells.

RBPJ controls the expression of IL-23R in Th17 cells

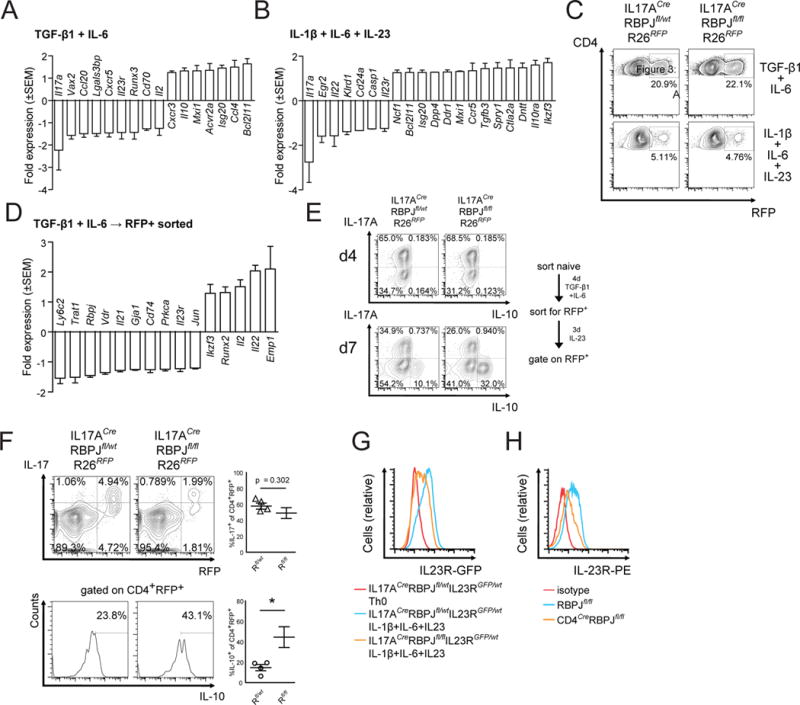

We therefore performed multiplex gene expression analysis using nanostring technology applying a codeset of 200 predefined Th17-related transcripts (Yosef et al., 2013) comparing the results with a previously defined pathogenic/non-pathogenic Th17 gene signature (Lee et al., 2012). Non-pathogenic Th17 cells (TGF-β1 + IL-6) differentiated from IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl mice showed a reduced expression of Il23r and increased expression of Il10 (Fig. 3A), that is part of a regulatory module in non-pathogenic Th17 cells. Conversely, the expression of Il23r, Il22, and Casp1, was reduced in pathogenic Th17 cells (IL-1β + IL-6 + IL-23) differentiated from IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl mice (Fig. 3B). These transcripts were previously identified as part of a pro-inflammatory module in pathogenic Th17 cells (Lee et al., 2012). In addition, Il17a which is the effector cytokine of pathogenic Th17 cells was downregulated under both conditions in IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl cells. RBPJ thus partly controls the expression of both pathogenic and non-pathogenic signature genes in Th17 cells.

Figure 3. RBPJ-deficient Th17 cells show non-pathogenic gene expression and are unstable in vitro due to a lack of IL-23R expression.

(A) Naïve CD4+CD62LhighCD44lowCD25− T cells were sorted from IL17ACreRBPJflox/wt and IL17ACreRBPJflox/flox mice and differentiated with TGF-β1 and IL-6. Expression of a predefined set of Th17-relevant genes was quantified using Nanostring nCounter after 4 days of culture. (B) Identical experiment as in A using naïve CD4+ cells differentiated with IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23. Average values from three independent experiments with technical duplicates per sample are depicted in A and B as fold change of IL17ACreRBPJflox/flox versus IL17ACreRBPJflox/wt cells. Please note that Il10 is upregulated 1.47-fold (data not shown), but does not reach the defined cut-off for minimum read counts i.e. transcript abundance. Cut-off for differentially regulated genes was ≥1.25-fold regulation. (C) Naïve T cells from IL17ACreRBPJflox/wtR26RFP and IL17ACreRBPJflox/floxR26RFP mice were differentiated in vitro with TGF-β1 and IL-6 or IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 for 4 days and the proportion of CD4+RFP+ cells was assessed by flow cytometry. (D) CD4+RFP+ cells were sorted from cultures differentiated with TGF-β1 and IL-6 described in (C) and analyzed for gene expression using Nanostring nCounter. Expression is depicted as fold-change of IL17ACreRBPJflox/floxR26RFP versus IL17ACreRBPJflox/wtR26RFP cells. Cut-off for differentially regulated genes was ≥1.25-fold and changes are averaged from three independent experiments. (E) Naïve T cells were differentiated with TGF-β1 and IL-6 from IL17ACreRBPJflox/wtR26RFP and IL17ACreRBPJflox/floxR26RFP mice as in D. Live CD4+RFP+ cells were sorted from the cultures and restimulated in vitro for 3 days with IL-23 only. Cytokine production was assessed before (d4) and after (d7) restimulation after gating on live RFP+ cells. (F) IL17ACreRBPJflox/wtR26RFP (Rfl/wt) and IL17ACreRBPJflox/floxR26RFP (Rfl/fl) mice were immunized with MOG35–55 and at peak of EAE, draining lymph nodes cells were cultured in the presence of 1 μg/ml MOG and IL-23 for 5 days. Intracellular cytokine production was assessed after gating on CD4+ (top) and on CD4+RFP+ (bottom) cells. Data in F are summarized from 4 independent mice in three independent experiments. (G) Il23r promoter driven GFP fluorescence was quantified in naïve T cells differentiated for 4 days without cytokines from IL17ACreRBPJflox/wtIL23RGFP/wt mice (red histogram), or with IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 from IL17ACreRBPJflox/wtIL23RGFP/wt mice (blue histogram) and IL17ACreRBPJflox/floxIL23RGFP/wt mice (orange histogram). (H) Naïve CD4+ T cells were sorted from RBPJflox/flox and CD4CreRBPJflox/flox mice, differentiated with IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 for 4 days, and IL-23R was detected by cell-surface staining for IL-23R. Data in C, E, G, H are representative of three independent experiments. See also Figure S3.

IL-23 promotes the pathogenicity and stability of Th17 cells. We next addressed whether RBPJ affects the stability of the Th17 cell lineage by crossing IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl mice with R26RFP mice thus generating IL-17A fate reporter mice as previously described (Hirota et al., 2011) (Fig. S3F). Th17 cells differentiated in vitro from IL17ACreRBPJfl/flR26RFP mice had unchanged RFP expression (Fig. 3C) indicating an unchanged initial commitment to the Th17 lineage. Instead, we observed a reduced production of IL-17 by CD4+RFP+ (i.e. lineage committed Th17 cells) generated under pathogenic differentiation conditions (IL-1β + IL-6 + IL-23) but not under non-pathogenic conditions (TGF-β1 + IL-6) from IL17ACreRBPJflllfR26RFP mice (Fig. S3G). This indicates that RBPJ-deficiency affects Th17 stability only under IL-23 dependent differentiation conditions. We also tested how efficiently the RBPJfl/fl allele was deleted by the IL17ACre allele and found a marked reduction, but no absence of RBPJ in CD4+RFP+ cells (Fig. S3H). Even the reduction of RBPJ expression in the IL17ACreRBPJflox mouse line is thus sufficient to impair an adequate response to IL-23 in Th17 cells.

We next sorted CD4+RFP+ cells, which constitute lineage committed Th17 cells, following in vitro differentiation with TGF-β1 + IL-6 and subjected them to nanostring analysis. Of note, expression of Il23r and Il21 was lower in RBPJ-deficient CD4+RFP+ cells compared to RBPJ-competent cells (Fig. 3D). When we cultured these sorted CD4+RFP+ cells in the presence of IL-23 to test their stability, IL17ACreRBPJflllfR26RFP cells lost IL-17 and gained IL-10 production to a greater extent than controls (Fig. 3E). We also used the IL17ACreRBPJflllfR26RFP mouse to address the lineage ontogeny of the CD4+IL-10+ population we had observed in draining lymph nodes in the absence of RBPJ (Fig. 2I). We found that a greater proportion of RFP+ cells were IL-10+ in IL17ACreRBPJflllfR26RFP mice (Fig. 3F) indicating that the increased IL-10+ cells in the absence of RBPJ derive from Th17 cells. Together, these data indicate that RBPJ-deficient T cells are unaffected in their initial commitment to the Th17 lineage, but lose stability and lose expression of members of the pathogenic transcriptional module including IL-23R while gaining expression of members of the regulatory module. We thus speculated that RBPJ helps to maintain the stability of the Th17 lineage by directly regulating the expression of IL-23R.

To address this, we examined the protein expression of IL-23R in pathogenic Th17 cells, which are known to express high levels of IL-23R (Lee et al., 2012). We crossed IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl mice with IL23RGFP reporter mice (Awasthi et al., 2009) and found that pathogenic Th17 cells from IL17ACreRBPJfl/flIL23RGFP mice showed reduced GFP expression compared to heterozygous IL17ACreRBPJfl/wt controls (Fig. 3G). IL-23R surface levels were also reduced in pathogenic Th17 cells from CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice stained with an anti-IL-23R antibody (Fig. 3H) confirming that RBPJ is in fact required to induce IL-23R protein expression in Th17 cells. A reduction in IL-23R expression was also observed in RBPJ-deficient non-pathogenic Th17 cells albeit at lower levels due to the low expression of IL-23R under these conditions (data not shown). Furthermore, activation of the Notch pathway by overexpression of the intracellular domain of Notch receptors 1–3 (NICD) also induced surface expression of IL-23R in Th17 cells (Fig. S4A). RBPJ and the Notch signalling pathway thus promote expression of the IL-23R and RBPJ is consequently required for the stability and pathogenicity of Th17 cells.

RBPJ binds and transactivates the Il23r promoter in cooperation with RORγt

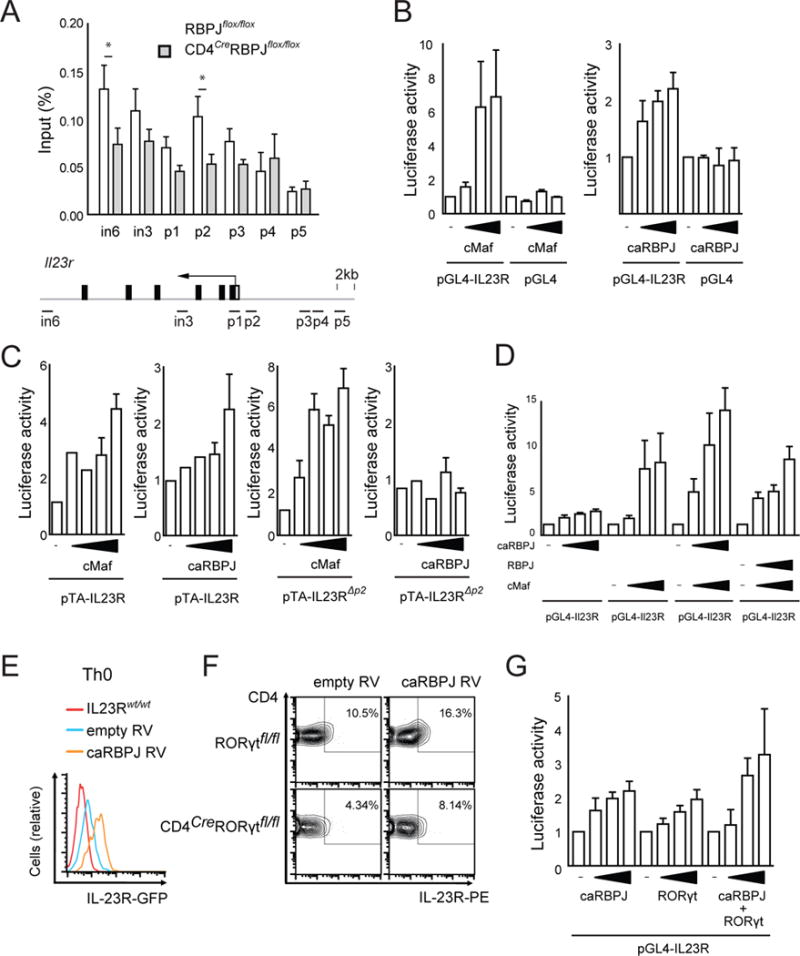

We next addressed how RBPJ controls the expression of IL-23R on a transcriptional level. We identified canonical RBPJ binding sites (Wang et al., 2011) in the proximal and distal promoter region (Fig. 4A) and in both enhancer regions in intron 3 and intron 6 of the Il23r gene (Fig. 4A), where Th17-related transcription factors such as RORγt bind (Xiao et al., 2014). To experimentally test for binding of RBPJ, we performed ChIP-PCR of the predicted RBPJ binding sites. Il23r promoter regions – preferentially a region ~1100bp upstream of the transcriptional start site termed p2 – showed enriched binding (Fig. 4A) indicating that RBPJ indeed binds the Il23r promoter. Of note, the site with most enrichment (p2) is distinct from sites bound by other Th17 cell related transcription factors (Ciofani et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2014; Yosef et al., 2013).

Figure 4. RBPJ binds and transactivates the Il23r promoter and induces IL-23R expression in cooperation with RORγt.

Naïve CD4+ T cells were sorted from RBPJflox/flox and CD4CreRBPJflox/flox mice and differentiated with TGF-β1 and IL-6 for 4 days followed by IL-23 for 3 days. Cross-linked protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated using an anti-RBPJ antibody. DNA was purified and used for qPCR with primers spanning parts of the Il23r promoter predicted to contain RBPJ binding sites indicated as horizontal bars in the scheme of the Il23r locus; in intron, p promoter. DNA binding was calculated as percentage of input DNA. One representative out of three independent experiments with three replicate samples per IP is shown. (B) Il23r promoter activity was measured in HEK293T cells transfected with a luciferase vector driven by 2.7kb of the IL23R promoter (pGL4-IL23R) and increasing amounts of constructs encoding c-Maf and consitutively active (ca)RBPJ (RBPJ-VP16). (C) IL23r promoter activity was measured after transfection with a luciferase vector driven by 1.5kb of the IL23R promoter (pTA-IL23R) and constructs encoding c-Maf and caRBPJ (RBPJ-VP16). Luciferase activity induced by c-Maf and RBPJ-VP16 was measured using an pTA-IL23R promoter construct with mutatetd RBPJ binding site p2 (pTA-IL23RΔp2). (D) pGL4-IL23R luciferase activity was measured after transfection with combinations of RBPJ, caRBPJ, and c-Maf constructs. Data in B–D are representative of five independent experiments. (E) Naïve T cells were sorted from IL23RGFP/wt reporter mice and transduced with either empty retrovirus (RV) (MSCV-Thy1.1) or RV encoding caRBPJ (MSCV-RBPJ-VP16-Thy1.1) and cultured without cytokines. GFP expression was detected after gating on live CD4+Thy1.1+ cells after 4 days of culture. (F) Naïve T cells were sorted from Rorγtflox/flox andCD4CreRorγtflox/flox mice and transduced with either empty RV or caRBPJ RV. Cell surface expression of IL-23R was analyzed after 4 days in culture after gating on live CD4+Thy1.1+ cells. (G) IL23r promoter activity was measured in HEK293T cells transfected with the pGL4-IL23R vector and increasing amounts of caRBPJ and Rorγt constructs or both. Luciferase activities were calculated as fold empty vector in B–D, G. One representative out of three independent experiments is shown in E–G.

Using a previously described IL23R promoter luciferase construct spanning 1.2kb of the Il23r promoter (pTA-Il23r), constitutively active (ca)RBPJ (RBPJ-VP16) transactivated the Il23r promoter (Fig. 4B). c-Maf which is known to activate Il23r expression (Sato et al., 2011) was used as a positive control. Mutating site p2 in this construct abrogated its activation by caRBPJ but not by c-Maf (Fig. 4C). This indicates that RBPJ directly controls transcription from the Il23r promoter dominantly through the p2 binding site, that is distinct and independent from other Th17 cell related transcription factors. We next tested whether non-modified RBPJ exerted repressive effects on the Il23r promoter. Non-modified RBPJ had no effect on c-Maf induced Il23r promoter activation while caRBPJ had additive effects together with c-Maf on the Il23r luciferase construct (Fig. 4D). Thus, the Notch pathway drives IL-23R expression through direct transcriptional control.

We next addressed whether RBPJ acted independently or in cooperation with the Th17-cell lineage defining transcription factor RORγt that was previously shown to bind the Il23r promoter at moderate levels (Ciofani et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2014). Retroviral overexpression of caRBPJ induced IL23RGFP reporter expression even in Th0 cells that do not express RORγt (Fig. 4E). Also, caRBPJ induced surface expression of IL-23R in the absence of RORγt in CD4CreRORγtflox/flox cells cultured in the presence of IL-1β + IL-6 + IL-23 (Fig. 4F). In accordance, both caRBPJ and RORγt individually activated the Il23r promoter luciferase construct, and when combined exhibited an additive effect in inducing IL-23R expression (Fig. 4G). RBPJ did not interact directly with RORγt on the protein level (Fig. S4B). Taken together our data indicate that the Th17 transcriptional program is not required for RBPJ to promote the expression of IL-23R but that RBPJ and RORγt may work in a combinatorial manner to induce maximum expression of IL-23R, but do not form a protein-protein complex.

The dominant function of RBPJ in Th17 cells is to maintain IL-23R expression

Our data indicate that RBPJ controls the generation and stability of pathogenic Th17 cells by directly driving IL-23R transcription. Previous studies, however, had reported that Notch controls transcription of IL-17A and RORγt itself although not testing for changes in IL-23R expression (Keerthivasan et al., 2011; Mukherjee et al., 2009) and we replicated these findings (Fig. S5A–C). We thus wanted to address whether RBPJ primarily controls Th17 cell differentiation through regulating IL-17A expression or through regulating IL-23R expression.

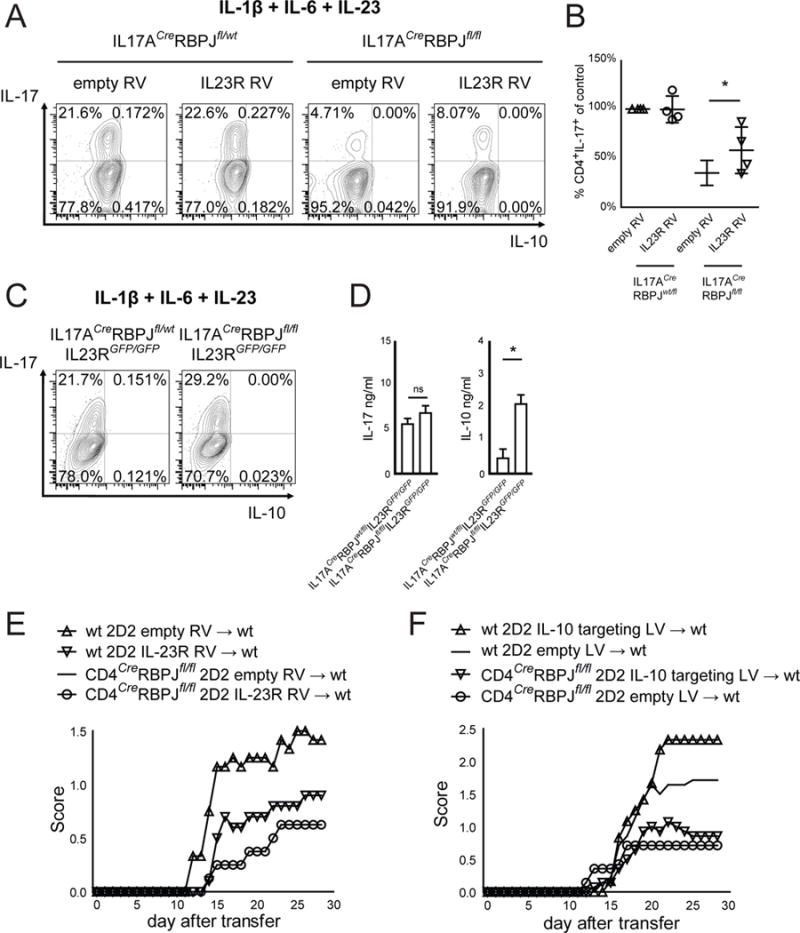

To this end, we retrovirally overexpressed IL-23R in IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl Th17 cells during differentiation under pathogenic Th17 conditions (IL-1β + IL-6 + IL-23), where IL-23R is required to stabilize IL-17 production and is maximally expressed in wildtype cells. Overexpression of IL-23R partly rescued the loss of IL-17A production in IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl cells (Fig. 5A, B) although the effect was small. To further dissect whether RBPJ mainly controls expression of IL-17 or IL-23R, we generated IL-23R / RBPJ double deficient mice by crossing IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl mice with IL23RGFP/GFP mice that lack functional IL-23R at homozygosity (Awasthi et al., 2009). Pathogenic Th17 cells (IL-1β + IL-6 + IL-23) differentiated from IL-23R / RBPJ double-deficient IL17ACreRBPJfl/flIL23RGFP/GFP mice showed no significant change in IL-17 production compared to IL-23R deficient / RBPJ-competent IL17ACreRBPJfl/wtIL23RGFP/GFP mice (Fig. 5C, D). This was in contrast to the reduced differentiation of pathogenic Th17 cells we had observed in IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl mice (Fig. 2C,D) and indicates that RBPJ-deficiency impairs Th17 cell differentiation only in the presence of IL-23R. Similar effects were observed in CD4CreRBPJfl/flIL23RGFP/GFP mice (data not shown).

Figure 5. RBPJ is required to promote IL-23R expression rather than IL-17 in Th17 cells.

(A) Naïve T cells from IL17ACreRBPJflox/wt and IL17ACreRBPJflox/flox mice were transduced with either empty retrovirus (RV) or with RV encoding mouse IL-23R and stained for intracellular cytokines after differentiation with IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 for 4 days. Gating was on live CD4+GFP+ cells. (B) The percentage of IL-17+ cells was calculated, defining empty RV in IL17ACreRBPJflox/wt cells as 100% in each experiment. Significance is calculated using Student’s t-test for paired samples. Data in A are representative and in B are summarized from 4 independent experiments. (C) Naïve T cells were sorted from IL17ACreRBPJflox/wtIL23RGFP/GFP and IL17ACreRBPJflox/floxIL23RGFP/GFP mice and differentiated with IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed after 4 days. (D) Cytokine ELISA of cell culture supernatants described in C. One representative of three independent experiments is shown in C and D. (E) Naïve T cells were sorted from wildtype 2D2 and CD4CreRBPJfl/fl2D2 mice and during Th17 differentiation were transduced with either empty or IL-23R encoding RV. After 7 days of culture, 6*106 cytokine producing T cells were intravenously injected into C57BL/6 wildtype recipients. The clinical score was assessed daily. (F) Naïve T cells were sorted from wildtype 2D2 and CD4CreRBPJfl/fl2D2 mice and during Th17 differentiation in vitro were transduced with a lentivirus (LV) encoding both Cas9 and an IL-10 targeting CRISPR guide RNA or Cas9 only (empty). After 7 days of culture, 8*106 cytokine producing T cells were intravenously injected into C57BL/6 wildtype recipients.

To address the importance of RBPJ in driving IL-23R expression versus IL-17 expression in vivo, we retrovirally overexpressed IL-23R in pathogenic 2D2 (expressing a MOG35–55-specific TCR) Th17 cells before transferring them into wildtype hosts. We found that overexpression of IL-23R partially rescued the protection from EAE conferred by RBPJ deficiency (Fig. 5E). Conversely, knock-out of IL-10 in 2D2 Th17 cells using a CRISPR/Cas9 lentiviral system did not rescue the protection from EAE conferred by RBPJ deficiency (Fig. 5F) and neutralization of IL-10 did not revert protection from actively induced EAE in CD4CreRBPJfl/fl mice (Fig. S5D). Together, these data indicate that driving IL-23R expression, not driving IL-17 or repressing IL-10 is the dominant function of RBPJ in Th17 cells in vivo.

Of note, RBPJ-deficient IL17ACreRBPJfl/flIL23RGFP/GFP pathogenic (IL-1β + IL-6 + IL-23) Th17 cells also produced higher amounts of IL-10 detected by ELISA although not by intracellular cytokine staining, than RBPJ-competent IL17ACreRBPJfl/wtIL23RGFP/GFP Th17 cells (Fig. 5D). Thus, RBPJ-deficiency enhances production of the non-pathogenic cytokine IL-10 even in the absence of IL-23R. This indicated that RBPJ may also serve as a repressor of IL-10 production in Th17 cells in vitro independently from its effect on IL-23R expression and although this is not its dominant function in vivo (Fig. 5E, F).

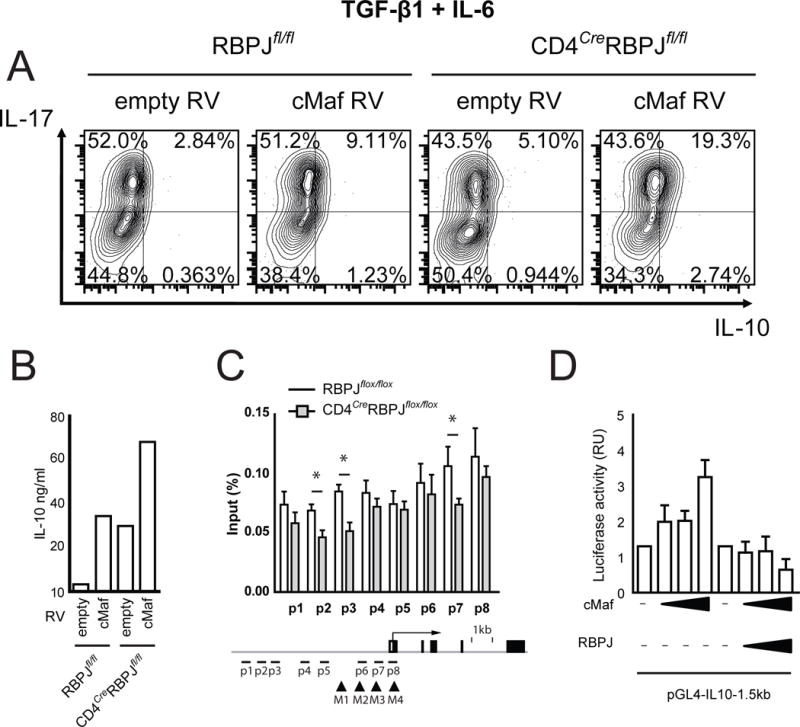

RBPJ serves as a repressor of c-Maf induced IL-10 production in Th17 cells

The transcription factor c-Maf is a known inducer of IL-10 in type 1 regulatory (Tr1) cells induced by IL-27 (Apetoh et al., 2011) and in Th17 cells (Bauquet et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2009) and we thus speculated that RBPJ may act as a repressor of the regulatory module including IL-10 controlled by c-Maf in Th17 cells. We overexpressed c-Maf in Th17 cells generated in the presence of TGF-β1 + IL-6 and found that in CD4CreRBPJfl/fl cells, c-Maf overexpression induced more IL-10 than in wildtype cells (Fig. 6A, B). We conclude that RBPJ may serve as a transcriptional repressor of c-Maf induced IL-10 expression in Th17 cells. The IL-10 genomic locus contains multiple predicted RBPJ binding sites and ChIP-PCR confirmed binding of RBPJ to the IL-10 locus in Th17 cells (Fig. 6C). Of note, two previously identified c-Maf response elements (MARE) in the Il10 promoter (Apetoh et al., 2011) were located within a 150bp range of predicted RBPJ binding sites (Fig. 6C). We did not observe protein-protein interaction between RBPJ and c-Maf (Fig. S6). Using a luciferase assay, we observed that non-modified RBPJ inhibited c-Maf induced activation of the IL-10 promoter (Fig. 6D) indicating that RBPJ can indeed repress IL-10 production induced by c-Maf. In conclusion, we identify RBPJ as an essential transcriptional regulator controlling the generation of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Th17 cells by promoting the expression of IL-23R and repressing the production of IL-10. However, effects of RBPJ on IL-23R are dominant in promoting the pathogenic phenotype of Th17 cells in vivo.

Figure 6. RBPJ represses c-Maf induced IL-10 production in Th17 cells.

(A) Sorted naïve RBPJflox/flox and CD4CreRBPJflox/flox CD4+ T cells were transduced with either empty MSCV-GFP or MSCV-cMaf-GFP retrovirus (RV) and cultured with TGF-β1 and IL-6 for 4 days and analyzed by intracellular cytokine staining. (B) Cell culture supernatants from cultures described in A were analyzed by ELISA. (C) Naïve CD4+ T cells were sorted from RBPJflox/flox and CD4CreRBPJflox/flox mice and differentiated in vitro with TGF-β1 and IL-6 for 4 days followed by IL-23 for 3 days. Cross-linked protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated with an anti-RBPJ antibody. DNA was purified and used for qPCR spanning predicted RBPJ binding sites in the IL-10 promoter. DNA binding was calculated as percentage of input DNA. Predicted RBPJ-binding sites are indicated as p1 to p8 and previously identified MARE-sites (Apetoh et al., 2011) are indicated as M1 to M4. One representative out of four independent experiments is shown in C with three replicate IPs per sample. (D) Il10 promoter activity was measured in HEK293T cells transfected with the pGL4-IL10-1.5kb luciferase vector and constructs encoding c-Maf and RBPJ. Luciferase activities were calculated as fold change compared to empty vector. One representative out of three independent experiments is shown in A, B, and D.

Discussion

Our previously generated transcriptional network of Th17 cells implicated RBPJ, the canonical Notch signalling molecule, as a positive regulator of Th17 differentiation (Yosef et al., 2013). While the previous study had relied on analysis and perturbation on the mRNA level, here we examined RBPJ in Th17 cells with technically more stringent approaches by testing for 1) the in vitro differentiation and 2) the in vivo function of Th17 cells in the absence of RBPJ and 3) identifying the mechanisms by which RBPJ controls Th17 cell differentiation. Using different genetic approaches we observed that RBPJ-deficiency does not affect the early stage of Th17 cell differentiation, but rather affects the stabilization stage when Th17 cells are rendered pathogenic through the effects of IL-23. We further demonstrate that RBPJ is required to maintain a pathogenic state of Th17 cells by driving expression of IL-23R and by repressing production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. RBPJ thus serves a highly specific purpose in Th17 cells – namely to promote the pathogenicity of Th17 cells by promoting the expression of members of the pro-inflamamtory module and repressing expression of the regulatory module. Therefore, this observation expands the array of functions of the Notch signalling pathway in the differentiation of various T cell subsets (reviewed in (Amsen et al., 2009)).

Consistent with our observations, pharmacological inhibition of Notch cleavage or Notch ligand binding was previously shown to ameliorate EAE (Bassil et al., 2011; Jurynczyk et al., 2008; Keerthivasan et al., 2011; Maekawa et al., 2015; Reynolds et al., 2011), but the mechanisms were not elucidated. Here, we did not rely on pharmacological inhibitors, but rather used genetic approaches to ablate the canonical Notch signalling molecule RBPJ in a cell type specific manner in Th17 cells. Driving Cre expression from the endogenous Il17a promoter or from an Il17f BAC transgenic line (Croxford et al., 2009; Hirota et al., 2011) allows deletion of RBPJ in all IL-17-expressing cells. RBPJ-deletion by Il17a promoter driven Cre expression was well detectable, but did not reach 100% deletion indicating that RBPJ mRNA may persist after recombination of the Rbpj genomic locus providing a potential explanation for the more subtle in vitro phenotype in IL17ACreRBPJfl/fl than in CD4CreRBPJfl/fl cells. Therefore, combining our data derived from the CD4Cre and IL17ACre lines and using the 2D2 adoptive transfer model in which RBPJ-deletion was specifically targeted to CNS-specific pathogenic Th17 cells and by overexpressing IL-23R, we demonstrate that RBPJ is required for the pathogenicity of Th17 cells by directly controlling IL-23R expression. IL-23 did not induce the expression of RBPJ indicating that RBPJ is an important up-stream controller of IL-23R expression, but does not form a positive feed-forward loop with IL-23R signalling.

Canonical Notch signalling serves a multitude of functions in T cells. It controls thymic development of T cells (Tanigaki and Honjo, 2007), the differentiation of several T helper cell lineages (Amsen et al., 2009; Bailis et al., 2013), the longevity of helper cells in vitro (Helbig et al., 2012), the expression of chemokine receptors in vitro (Reynolds et al., 2011), and the survival of memory T cells in a re-stimulation paradigm in vivo (Maekawa et al., 2015). However, by using Th17 cell-specific deletion of RBPJ, we did not find evidence for survival-related effects in our experimental setting (Fig. S5A–E) and by overexpressing IL-23R (Fig. 5) we demonstrate that RBPJ regulates Th17 pathogenicity specifically by controlling IL-23R expression. By generating RBPJ / IL 23R double deficient mice and by overexpressing IL-23R in Th17 cells transferred in vivo, we also demonstrate that the dominant function of RBPJ in Th17 cells in vivo is to promote the expression of IL-23R and the pathogenic functional state of Th17 cells.

Th17 cells do not all induce autoimmune disease. It is becoming increasingly clear that Th17 cells mediate tissue homeostasis at mucosal surfaces. In fact, IL-17 production by T cells may serve a protective function in the gut without inducing tissue inflammation (O’Connor et al., 2009) and gut resident Th17 cells partly resemble non-pathogenic Th17 cells that co-produce IL-17 and IL-10 (Esplugues et al., 2011; Gagliani et al., 2015). These different functional states of Th17 cells may have evolutionarily arisen to defend against specific pathogens as shown in humans (Zielinski et al., 2012). Identifying the factors controlling the balance between such pathogenic and non-pathogenic Th17 cells may provide the key to understanding how to inhibit pathogenic Th17 cells that induce tissue inflammation and autoimmune diseases, but spare those that maintain gut barrier functions and promote tissue homeostasis. Our data indicate that the Notch signalling pathway may be one of the key check-points in determining the balance between the pathogenic and non-pathogenic states of Th17 cells. The biological importance is further strengthened by genetic linkage of the RBPJ genomic locus with rheumatoid arthritis (Stahl et al., 2010), in which Th17 cells are important (Miossec and Kolls, 2012).

In the canonical Notch signalling pathway, RBPJ is bound to DNA and acts as a transcriptional repressor in the absence of Notch intracellular domain (NICD) (Amsen et al., 2009). Only after ligand binding, NICD will translocate to the nucleus and convert RBPJ to a transcriptional co-activator (Amsen et al., 2009). RBPJ can thus exert dual functions as either a transcriptional repressor or inducer depending on the nuclear availability of NICD and thus on the activity of the Notch pathway. This dual function of RBPJ may account for the induction of IL-10 by NICD in Th1 cells (Kassner et al., 2010; Rutz et al., 2008), but inhibition of IL-10 by RBPJ, which we describe here. In fact, over-expression of NICD also induces IL-10 in Th17 cells (data not shown) in accordance with the dual role of RBPJ as transcriptional activator or repressor. We here describe that the Il10 and Il23r loci respond differently to RBPJ-mediated repression in the absence of Notch pathway activation. RBPJ does not alter cMaf induced transcription of the Il23r locus, but inhibits cMaf induced transcription of the Il10 locus (Fig. 6). The activity of the Notch signalling pathway may thus serve as a transcriptional switch to determine how c-Maf, and potentially other transcription factors control the transcription of IL-10 and IL-23R expression in Th17 cells.

We here describe a dual function of RBPJ in Th17 cells as both promoting pathogenicity by inducing IL-23R expression and inhibiting the production of anti-inflammatory IL-10. We therefore identify RBPJ as a transcriptional switch in Th17 cells and provide a mechanistic explanation of how RBPJ can promote the generation of pathogenic Th17 cells and inhibit the generation of non-pathogenic Th17 cells. Our identification of RBPJ as a regulator that can differentially affect pathogenic and non-pathogenic Th17 cells will offer targets to inhibit pathogenic Th17 cells yet spare beneficial tissue protective Th17 cells.

Experimental Procedures

Animals and EAE

CD4Cre mice were from Taconic. B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ mice (named CD45.1) and B6;129S6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J mice (Madisen et al., 2010) (named R26RFP), were from The Jackson Laboratories. IL17ACre (Hirota et al., 2011), RBPJflox (Tanigaki et al., 2002), IL23RGFP (Awasthi et al., 2009), and 2D2 (Bettelli et al., 2003) mice were previously described. All experiments were carried out in accordance with guidelines prescribed by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Harvard Medical School. Age and sex matched mice (7–9 weeks old) were immunized for EAE as previously described (Xiao et al., 2014). IL-10 neutralization in vivo was performed with 500 μg of low endotoxin azide free either rat IgG1 or anti-IL-10 antibody (clone JES5-16E3, Biolegend) intraperitoneally on day 0, 2, 7 as described (McGeachy et al., 2007). Adoptive transfer EAE using Th17 differentiated 2D2 cells was performed as described (Jager et al., 2009). For transduction before adoptive transfer, 2D2 cells were spin infected (600×g for 45 min at 25 °C) with retroviral supernatants on day 1 after plating with polybrene (8 μg/ml) or with lentiviral supernatants. Cells were not sorted or selected for transduction before transfer.

CD4+ T cell differentiation and retroviral transduction

CD4+CD44lowCD62LhighCD25− naive CD4+ T cells were purified by flow cytometry following MACS bead isolation of CD4+ cells. Naïve T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml, 145-2C11) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml, PV-1) antibody in 96-well or 24-well plates. In vitro T cell differentiation was performed for 96h. For non-pathogenic Th17 cell differentiation, cultures were supplemented with IL-6 (20 ng/ml) and TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml). For pathogenic Th17 cells differentiation cultures were supplemented with IL-1β (20 ng/ml), IL-6 (20 ng/ml) and IL-23 (10 ng/ml). Retrovirus containing supernatants were produced by transiently transfecting HEK 293T producer cells with retroviral packaging constructs (PCL-Eco, gag/pol) together with retroviral expression plasmids using Fugene HD (Roche). Culture supernatants were harvested after 72 hours, supplemented with polybrene (8 mg/mL), and added to sorted naïve T cells previously stimulated for 24h (1×105 per well, 96 well plate, plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28, both 2 μg/ml, and indicated cytokines). Cultures were centrifuged at 600×g for 45 min at 25 °C. After additional 72h of culturing, intracellular cytokine staining was performed. Gating was on CD4+7AAD−Thy1.1+ cells. The CRISPR/Cas9 was previously described (Parnas et al., 2015) and Cas9 is driven by a modified EF-S promoter, and sgRNA is driven by mammalian U6 promoter. Packaging was with a VSV-G envelope.

Generation of constructs and luciferase assays

The pTA-IL23R plasmid was previously described (Sato et al., 2011). The pTA-IL23RΔp2 plasmid was generated by PCR site directed mutagenesis modifying the GTGGGAA sequence at −1151bp from the Il23r TSS to GTAAAAA. The pGL4-IL23R construct was generated by PCR amplifying a 2.7 Kb part of the Il23r promoter (−2.714 – 0 bp from TSS) from a mouse BAC clone (RPCI-23-34P19, BACPAC CHORI repository) and cloning the product into the pGL4.10 vector (Promega) using NheI/EcoRV sites. The coding part of all constructs was verified by sequencing. Luciferase assays were performed in HEK 293T cells using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). The Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity and is expressed as relative values compared to empty vector control.

Statistics

The clinical score of EAE was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. All other results were analyzed by Student’s t test. p<0.05 was considered significant. * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

RBPJ promotes experimental CNS autoimmunity via the IL-23R.

BPJ-deficient Th17 cells fail to express IL-23R and related transcripts.

RBPJ binds and transactivates the Il23r promoter together with RORγt.

RBPJ represses expression of IL-10 in Th17 cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Deneen Kozoriz for cell sorting. We thank Dr. Ana C. Anderson (Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA) and Dr. Tobias Lautwein (University of Munster, Germany) for critically reading the manuscript. We thank Dr. Karsan (British Columbia Cancer Research Centre, Vancouver, BC, Canada) for providing us with the human RBPJ-VP16 construct. We thank Dr. D. Cua (Merck Research Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA) for providing us with the anti-IL-23R antibody. G.M.z.H. was funded in part by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG grant number ME4050/1-1) and a National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) postdoctoral fellowship. S.X. was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (K01DK090105). V.K.K. was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS030843, P01NS076410, P01AI056299).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

For a detailed description of all experimental procedures see the Supplemental Information.

Author contributions

G.M.z.H., C. Wu, C. Wang, L.C., M.P., Y.L., S.X. performed experiments. W.E., S.X., A.R. provided reagents. G.M.z.H., C. Wu, V.K.K. concepted the study. G.M.z.H., V.K.K. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Abromson-Leeman S, Bronson RT, Dorf ME. Encephalitogenic T cells that stably express both T-bet and ROR gamma t consistently produce IFNgamma but have a spectrum of IL-17 profiles. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2009;215:10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsen D, Antov A, Flavell RA. The different faces of Notch in T-helper-cell differentiation. Nature reviews Immunology. 2009;9:116–124. doi: 10.1038/nri2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apetoh L, Quintana FJ, Pot C, Joller N, Xiao S, Kumar D, Burns EJ, Sherr DH, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacts with c-Maf to promote the differentiation of type 1 regulatory T cells induced by IL-27. Nature immunology. 2011;11:854–861. doi: 10.1038/ni.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi A, Carrier Y, Peron JP, Bettelli E, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M, Weiner HL. A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8:1380–1389. doi: 10.1038/ni1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi A, Riol-Blanco L, Jager A, Korn T, Pot C, Galileos G, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M. Cutting edge: IL-23 receptor gfp reporter mice reveal distinct populations of IL-17-producing cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5904–5908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailis W, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Fang TC, Hatton RD, Weaver CT, Artis D, Pear WS. Notch simultaneously orchestrates multiple helper T cell programs independently of cytokine signals. Immunity. 2013;39:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassil R, Zhu B, Lahoud Y, Riella LV, Yagita H, Elyaman W, Khoury SJ. Notch ligand delta-like 4 blockade alleviates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by promoting regulatory T cell development. J Immunol. 2011;187:2322–2328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauquet AT, Jin H, Paterson AM, Mitsdoerffer M, Ho IC, Sharpe AH, Kuchroo VK. The costimulatory molecule ICOS regulates the expression of c-Maf and IL-21 in the development of follicular T helper cells and TH-17 cells. Nature immunology. 2009;10:167–175. doi: 10.1038/ni.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. IL-12- and IL-23-induced T helper cell subsets: birds of the same feather flock together. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201:169–171. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Pagany M, Weiner HL, Linington C, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T cell receptor transgenic mice develop spontaneous autoimmune optic neuritis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;197:1073–1081. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciofani M, Madar A, Galan C, Sellars M, Mace K, Pauli F, Agarwal A, Huang W, Parkurst CN, Muratet M, et al. A validated regulatory network for Th17 cell specification. Cell. 2012;151:289–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codarri L, Gyulveszi G, Tosevski V, Hesske L, Fontana A, Magnenat L, Suter T, Becher B. RORgammat drives production of the cytokine GM-CSF in helper T cells, which is essential for the effector phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Nature immunology. 2011;12:560–567. doi: 10.1038/ni.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxford AL, Kurschus FC, Waisman A. Cutting edge: an IL-17F-CreEYFP reporter mouse allows fate mapping of Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:1237–1241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cua DJ, Sherlock J, Chen Y, Murphy CA, Joyce B, Seymour B, Lucian L, To W, Kwan S, Churakova T, et al. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003;421:744–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ, Steinhart AH, Abraham C, Regueiro M, Griffiths A, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Behi M, Ciric B, Dai H, Yan Y, Cullimore M, Safavi F, Zhang GX, Dittel BN, Rostami A. The encephalitogenicity of T(H)17 cells is dependent on IL-1- and IL-23-induced production of the cytokine GM-CSF. Nature immunology. 2011;12:568–575. doi: 10.1038/ni.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esplugues E, Huber S, Gagliani N, Hauser AE, Town T, Wan YY, O’Connor W, Jr, Rongvaux A, Van Rooijen N, Haberman AM, et al. Control of TH17 cells occurs in the small intestine. Nature. 2011;475:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliani N, Vesely MC, Iseppon A, Brockmann L, Xu H, Palm NW, de Zoete MR, Licona-Limon P, Paiva RS, Ching T, et al. Th17 cells transdifferentiate into regulatory T cells during resolution of inflammation. Nature. 2015;523:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature14452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, Hirahara K, O’Shea JJ. T helper 17 cell heterogeneity and pathogenicity in autoimmune disease. Trends in immunology. 2011;32:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, Tato CM, McGeachy MJ, Konkel JE, Ramos HL, Wei L, Davidson TS, Bouladoux N, et al. Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2010;467:967–971. doi: 10.1038/nature09447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig C, Gentek R, Backer RA, de Souza Y, Derks IA, Eldering E, Wagner K, Jankovic D, Gridley T, Moerland PD, et al. Notch controls the magnitude of T helper cell responses by promoting cellular longevity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:9041–9046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206044109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K, Duarte JH, Veldhoen M, Hornsby E, Li Y, Cua DJ, Ahlfors H, Wilhelm C, Tolaini M, Menzel U, et al. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nature immunology. 2011;12:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager A, Dardalhon V, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. Th1, Th17, and Th9 effector cells induce experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with different pathological phenotypes. J Immunol. 2009;183:7169–7177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurynczyk M, Jurewicz A, Raine CS, Selmaj K. Notch3 inhibition in myelin-reactive T cells down-regulates protein kinase C theta and attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:2634–2640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassner N, Krueger M, Yagita H, Dzionek A, Hutloff A, Kroczek R, Scheffold A, Rutz S. Cutting edge: Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce IL-10 production in T cells via the Delta-like-4/Notch axis. J Immunol. 2010;184:550–554. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keerthivasan S, Suleiman R, Lawlor R, Roderick J, Bates T, Minter L, Anguita J, Juncadella I, Nickoloff BJ, Le Poole IC, et al. Notch signaling regulates mouse and human Th17 differentiation. J Immunol. 2011;187:692–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annual review of immunology. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Awasthi A, Yosef N, Quintana FJ, Xiao S, Peters A, Wu C, Kleinewietfeld M, Kunder S, Hafler DA, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature immunology. 2012;13:991–999. doi: 10.1038/ni.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa Y, Ishifune C, Tsukumo S, Hozumi K, Yagita H, Yasutomo K. Notch controls the survival of memory CD4+ T cells by regulating glucose uptake. Nature medicine. 2015;21:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeachy MJ, Bak-Jensen KS, Chen Y, Tato CM, Blumenschein W, McClanahan T, Cua DJ. TGF-beta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nature immunology. 2007;8:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/ni1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, Laurence A, Joyce-Shaikh B, Blumenschein WM, McClanahan TK, O’Shea JJ, Cua DJ. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nature immunology. 2009;10:314–324. doi: 10.1038/ni.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miossec P, Kolls JK. Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2012;11:763–776. doi: 10.1038/nrd3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Schaller MA, Neupane R, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW. Regulation of T cell activation by Notch ligand, DLL4, promotes IL-17 production and Rorc activation. J Immunol. 2009;182:7381–7388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair RP, Duffin KC, Helms C, Ding J, Stuart PE, Goldgar D, Gudjonsson JE, Li Y, Tejasvi T, Feng BJ, et al. Genome-wide scan reveals association of psoriasis with IL-23 and NF-kappaB pathways. Nature genetics. 2009;41:199–204. doi: 10.1038/ng.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor W, Jr, Kamanaka M, Booth CJ, Town T, Nakae S, Iwakura Y, Kolls JK, Flavell RA. A protective function for interleukin 17A in T cell-mediated intestinal inflammation. Nature immunology. 2009;10:603–609. doi: 10.1038/ni.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnas O, Jovanovic M, Eisenhaure TM, Herbst RH, Dixit A, Ye CJ, Przybylski D, Platt RJ, Tirosh I, Sanjana NE, et al. A Genome-wide CRISPR Screen in Primary Immune Cells to Dissect Regulatory Networks. Cell. 2015;162:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reveille JD. Genetics of spondyloarthritis–beyond the MHC. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2012;8:296–304. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds ND, Lukacs NW, Long N, Karpus WJ. Delta-like ligand 4 regulates central nervous system T cell accumulation during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2011;187:2803–2813. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutz S, Janke M, Kassner N, Hohnstein T, Krueger M, Scheffold A. Notch regulates IL-10 production by T helper 1 cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:3497–3502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712102105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Miyoshi F, Yokota K, Araki Y, Asanuma Y, Akiyama Y, Yoh K, Takahashi S, Aburatani H, Mimura T. Marked induction of c-Maf protein during Th17 cell differentiation and its implication in memory Th cell development. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:14963–14971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.218867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl EA, Raychaudhuri S, Remmers EF, Xie G, Eyre S, Thomson BP, Li Y, Kurreeman FA, Zhernakova A, Hinks A, et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis identifies seven new rheumatoid arthritis risk loci. Nature genetics. 2010;42:508–514. doi: 10.1038/ng.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigaki K, Han H, Yamamoto N, Tashiro K, Ikegawa M, Kuroda K, Suzuki A, Nakano T, Honjo T. Notch-RBP-J signaling is involved in cell fate determination of marginal zone B cells. Nature immunology. 2002;3:443–450. doi: 10.1038/ni793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigaki K, Honjo T. Regulation of lymphocyte development by Notch signaling. Nature immunology. 2007;8:451–456. doi: 10.1038/ni1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zou J, Zhao B, Johannsen E, Ashworth T, Wong H, Pear WS, Schug J, Blacklow SC, Arnett KL, et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals conserved and divergent features of Notch1/RBPJ binding in human and murine T-lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:14908–14913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109023108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Yosef N, Yang J, Wang Y, Zhou L, Zhu C, Wu C, Baloglu E, Schmidt D, Ramesh R, et al. Small-molecule RORgammat antagonists inhibit T helper 17 cell transcriptional network by divergent mechanisms. Immunity. 2014;40:477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Yang Y, Qiu G, Lal G, Wu Z, Levy DE, Ochando JC, Bromberg JS, Ding Y. c-Maf regulates IL-10 expression during Th17 polarization. J Immunol. 2009;182:6226–6236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef N, Shalek AK, Gaublomme JT, Jin H, Lee Y, Awasthi A, Wu C, Karwacz K, Xiao S, Jorgolli M, et al. Dynamic regulatory network controlling TH17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2013;496:461–468. doi: 10.1038/nature11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski CE, Mele F, Aschenbrenner D, Jarrossay D, Ronchi F, Gattorno M, Monticelli S, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Pathogen-induced human TH17 cells produce IFN-gamma or IL-10 and are regulated by IL-1beta. Nature. 2012;484:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.