Abstract

Spirochetes, a genetically and morphologically distinct group of bacteria, are thin, spiral-shaped, and highly motile. They are known causes of several human diseases such as syphilis, Lyme disease, relapsing fever, and leptospirosis. We report a case of colonic spirochetosis in a healthy patient presenting for surveillance colonoscopy. The diagnosis of intestinal spirochetosis was made accidentally during the histological examination of colonic polyps, which were removed during colonoscopy. We also performed an extensive review on intestinal spirochetosis with a focus on clinical presentation and outcomes of reported cases from the past two decades.

Keywords: Spirochetosis, Colon, Immunocompetent host

Introduction

Spirochetes are a genetically and morphologically distinct group of bacteria. Morphologically, they are thin, spiral-shaped, and highly motile.1 Spirochetes are known causes of several human diseases such as syphilis, Lyme disease, relapsing fever, and leptospirosis. Intestinal infestation by spirochetes has long been recognized.2 Clinical presentations vary, ranging from asymptomatic to gastrointestinal (GI)-related symptoms such as bleeding or diarrhea.3 We report a case of colonic spirochetosis in a healthy patient who initially presented for surveillance colonoscopy. Additionally, we also perform an extensive review of previously reported cases in the literature.

Case Report

A 60-year-old asymptomatic man with no significant past medical history underwent a surveillance colonoscopy due to a previous history of a 1.8-cm hyperplastic polyp at the ileocecal valve. He denied weight loss and any GI symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, or rectal bleeding. Colonoscopy revealed 2 tubular adenoma polyps in the cecum and 6 hyperplastic polyps in the rectosigmoid junction, ranging from 2 to 4 mm. The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of these polyps showed several filamentous structures on the colonic epithelium (Figures 1 and 2). A Warthin-Starry stain was subsequently performed and confirmed the diagnosis of intestinal spirochetosis (Figure 3). He also tested negative for HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection.

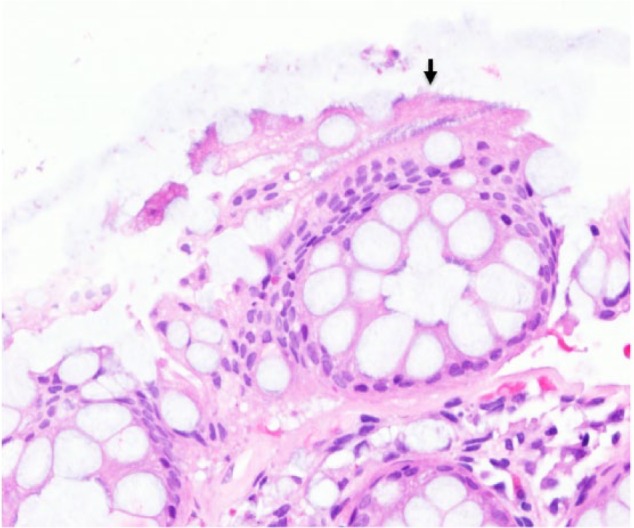

Figure 1.

Intestinal spirochetosis on H&E stain (20×). Solid black arrow indicates spirochetes attached to the luminal side of colonic mucosa forming a “false brush border.”

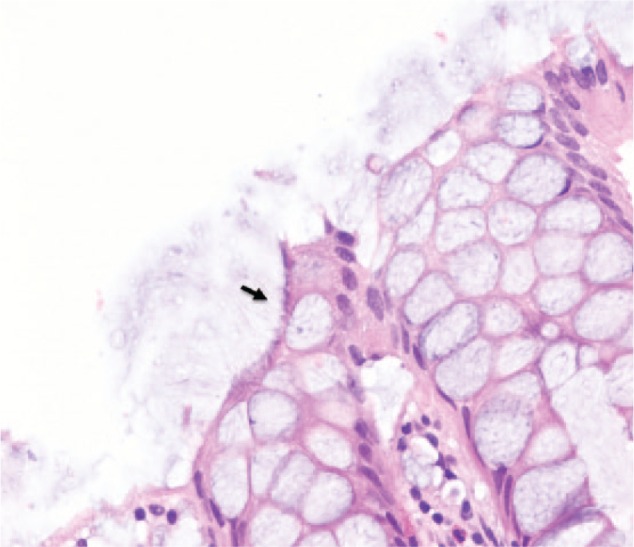

Figure 2.

Intestinal spirochetosis on H&E stain (40×). Solid black arrow indicates spirochetes attached to the luminal side of colonic mucosa forming a “false brush border.”

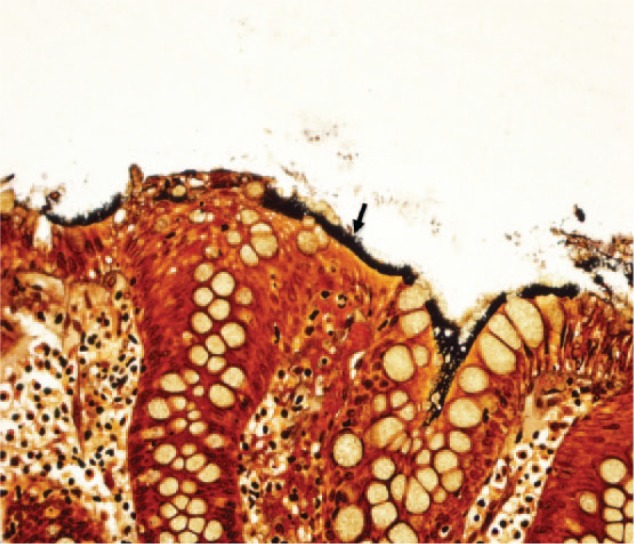

Figure 3.

Intestinal spirochetosis on Warthin-Starry (silver) stain (40×). Solid black arrow indicates spirochetes attached to the luminal side of colonic mucosa forming a “false brush border.”

Discussion

Intestinal spirochetosis (IS), first described by Harland and Lee in 1967 using electron microscopy,4,5 is an uncommon disease in humans defined by colonization of the luminal surface of colonic epithelial cells with anaerobic spirochetes of the Brachyspiraceace family, which include Brachyspira aalborgi (measuring 2-6 µm in length) and Brachyspira piloscoli (measuring 4-20 µm in length).6,7

The prevalence of IS varies from 2.5% to 32%, depending on geographic locations and diagnostic modalities.6,8,9 The reported prevalence of human IS found in rectal biopsy specimens ranges between 2% and 7% in Western countries, whereas the prevalence is considerably higher in patients from India and other parts of Asia.6 Of note, the overall prevalence is much lower when the diagnosis is made using stool culture (1.2% to 1.5%6,10) compared to that from mucosal biopsies. The highest prevalence of IS was previously reported in homosexual men (30% to 60%) as well as in HIV-positive patients.3,6,7,11 However, in a recent study from Japan including 5265 consecutive colorectal biopsies from 4254 patients, the authors found that 5.5% of those with HIV seropositivity had IS compared to 1.7% in those with negative serology.7 The lengths of the spirochetes were also significantly longer in HIV-positive patients.7

IS is found primarily in the colon, though there have been reported cases in the stomach and small intestine from the early 1900s.6 Similar to the case we present, most cases of IS are an incidental finding discovered during a screening/surveillance colonoscopy.5 The clinical as well as prognostic significance of IS are debatable. Given the lack of association between the presence of IS and GI symptoms, current theory suggests IS has a commensal relationship with the human host and is part of normal flora.2,6,12 However, spirochetes can become pathogenic and invasive in a subset of patients, due to diminishing host defenses or a pathologic factor favoring the virulence of the microorganism.6 In symptomatic cases, IS most commonly presents with chronic watery diarrhea and abdominal pain. Most cases are mild. However, some may present with an invasive and rapidly fatal course.6

Using PubMed, we searched the English-language literature published between January 1996 and May 2016. The terms utilized in the search were “intestinal spirochetosis” and “human subjects.” Reference lists of the identified articles were also reviewed to find additional cases. The baseline characteristics, clinical presentations, as well as outcomes of these cases are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Reported Cases With IS From 1996 to 2016a.

| Year (Reference) | Age (Years)/Sex | Underlying Condition/Risk Factor | Clinical Presentation | Endoscopic Findings | Histologic Findings | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult population (18 years of age and older) | |||||||

| 201517 | 39/male | HIV | Watery, nonbloody diarrhea, abdominal distention | Normal | IS | Penicillin (2 weeks) | Initially, responded well but then developed toxic megacolon 2 years later requiring total colectomy |

| 201518 | 63/male | Healthy | Asymptomatic, + FOBT | Intestinal stricture of transverse colon | Chronic infective colitis consistent with IS | Metronidazole (2 weeks) | Not effective, pathology showed mucinous adenocarcinoma associated with IS requiring subtotal colectomy |

| 201419 | 37/male | 15-year history of pan-ulcerative total colitis | Diarrhea 2-3 times per day, occasional bloody stools | Mild erosive mucosa in both sigmoid colon and rectum; longitudinal ulcer in transverse colon | IS | Mesalazine + prednisolone | Responsive to mesalazine and prednisolone but difficult to taper prednisolone; improvement after metronidazole |

| Metronidazole | |||||||

| 61/male | 20-year history of distal ulcerative colitis | Diarrhea 4-5 times per day, occasional bloody stools | Irregularly shaped ulcer in rectum | IS | Prednisolone | No resolution of ulcer with prednisolone; improvement with metronidazole | |

| Metronidazole | |||||||

| 201420 | 60/male | Hepatitis C cirrhosis | Progressive weight loss | Sessile polyp in ascending colon | IS | No treatment | No follow-up information |

| 201121 | 34/male | Healthy | Abdominal pain, diarrhea | Not performed; CT showed colocolic intussusception | IS; florid lymphoid hyperplasia in submucosa of terminal ileum and ileocecal valve | Right hemicolectomy | Resolution |

| 201022 | 60/male | Healthy | Lower abdominal pain, loose stools | Mild erythema of cecum and ascending colon | IS | Metronidazole (400 mg ×10 days) | Improvement |

| 200923 | Middle-aged | HIV | Soft stools, occasionally bloody | Small polyp in cecum | Tubular adenoma with IS on luminal epithelium | Amoxicillin | No follow-up information |

| 200824 | 23/male | Healthy | Diarrhea | Patchy edema with areas of erythema and small erosions | Patchy mucosal inflammation and IS | Clarithromycin (800 mg/day ×10 days) | Improvement |

| 201025 | 68/male | Healthy | Persistent diarrhea | Normal | IS | Metronidazole (750 mg/8 h ×10 days) | Resolution |

| 200726 | 17 cases in the series/age 4-75 | Healthy and those with HIV | Diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, abdominal pain, iron deficiency anemia | All cases with mucosal erosions/hyperemia | Inflammatory cells infiltrate | Metronidazole | Resolution except for one died from pulmonary embolism and one lost to follow-up |

| 200727 | 31/male | Healthy | Abdominal pain, watery diarrhea | Edematous mucosa with erythematous spots in ascending and transverse colon; sigmoid sessile polyp | IS | Metronidazole (1000 mg/day ×7 days) | Resolution |

| 200628 | 11 cases in the series/age 29-87 | Healthy and those with HIV | Diarrhea and abdominal pain | Normal to extensive area of inflammation | Normal mucosa to inflammatory cells infiltrate and mucosal ulceration | Metronidazole (500 mg PO 4 times per day) | Resolution except 2 with persistent diarrhea, and one subject with abdominal pain but without reported outcome |

| Some cases received benzathine penicillin 2.4 million units IM single dose | |||||||

| 200529 | 62/male | HIV | Flatulence, intestinal hemorrhage | Pan-colonic hypotonic diverticular disease | IS | Penicillin G | Resolution |

| 200430 | 41/male | HIV, neuropathy, GERD, depression | Abdominal pain, loose stools, hematochezia | Nonspecific inflammation without colitis | IS | Metronidazole | Resolution |

| 200431 | 57/female | Rectal prolapse | Asymptomatic | Not performed | IS and pneumatosis coli; IS within pneumatic cysts | No information on treatment | No follow-up |

| 200232 | 78/male | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Severe bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain | Not performed | IS | No information on treatment | No follow-up |

| 200133 | 50/male | Healthy | Diarrhea, abdominal cramping | Normal | IS | Metronidazole | Resolution |

| 200034 | 57/male | Healthy | Asymptomatic | Two polyps in descending and sigmoid colon | IS | No information on treatment | No follow-up |

| 200035 | 32/male | Healthy | Bloating, lower abdominal pain, watery diarrhea | Normal | IS | Metronidazole (500 mg 4×/day for 10 days) | Improvement |

| 199836 | 65/male | Presumed healthy (HIV test not performed) | Weight loss | Red spot on mucosa of cecum, small polyps in descending colon | IS | No treatment | No follow-up |

| 199637 | 21/female | Healthy; heterosexual | Rectal bleeding | Active proctitis, mild erythema of rectal and colonic mucosa | IS | Hydrocortisone 1% rectal foam | Resolution |

| 28/male | Healthy; heterosexual | Intermittent nausea and lassitude, weight loss | Patchy erythema in sigmoid colon, intense erythema, mucosal nodularity and friability in distal rectum | IS in rectal biopsy; lymphocytes and plasma cells within lamina propria, no spirochetes on sigmoid biopsy | High fiber diet (unsure etiology of symptoms and thought to have post-infectious IBS) | Improvement | |

| 45/male | Healthy; heterosexual | Colicky pain in left iliac fossa, flatulence, diarrhea | Normal | IS | No treatment (diagnosed with IBS due to uncertain significance of intestinal spirochetosis at that time) | No follow-up | |

| Pediatric population (0-18 years of age) | |||||||

| 201238 | 13/male | Recurrent aphthous stomatitis | Blood-stained diarrhea, urgency, weight loss | Mucosal edema in sigmoid and rectum | IS | Amoxicillin (2 weeks) | Cessation of rectal bleeding but continuous mucous diarrhea with amoxicillin; resolution with metronidazole |

| Metronidazole (10 days) | |||||||

| 201239 | 14/female | Healthy | Intermittent generalized abdominal pain | Normal | IS | Metronidazole | No follow-up |

| 201040 | 11/female | HSV, psoriasis, upper airway disease | Intermittent abdominal pain, hematochezia | Normal | IS | Metronidazole (250 mg 3×/day) | No improvement after repeated courses of metronidazole and vancomycin, spirochetes found on repeat endoscopy |

| Metronidazole (1000 mg for 2 weeks, 2 months, then 750 mg/day for 2 weeks) | No follow-up information | ||||||

| Vancomycin (7 days) | |||||||

| 6/male | Healthy | Stomach cramps, hematochezia, intermittent diarrhea, rectal prolapse, “pencil-thin” stools | Normal | IS | Metronidazole (250 mg 3×/day for 2 weeks) | Mild improvement but continuous alternating constipation with watery diarrhea, continuous regurgitation, rectal prolapse | |

| 11/female | Healthy | Right lower quadrant pain | Not performed | Mild acute appendicitis and IS in resected appendix | Cefoxitin (30 mg/kg/dose × 4 doses) | Resolution | |

| Appendectomy | |||||||

| 17/female | Healthy | Relapsing abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | Performed, no information | Mild eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate with IS | No treatment | No follow-up | |

| 10/male | Healthy | Periumbilical and epigastric pain, nausea, fever | Not performed | Acute appendicitis and IS in resected appendix | No treatment | No follow-up | |

| 200541 | 9/male | Healthy | Blood mixed in stool, diarrhea | Normal | IS | No therapy | Resolution, spirochetes eradicated |

| 200442 | 9/male | Healthy | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia | Mild erythema of rectal mucosa | IS | Erythromycin (40 mg/kg/day × 10 days) | Resolution |

| 200243 | 5/female | Enterobiasis | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, occasional blood | Edema in rectum | IS | Erythromycin 40 mg/kg/day × 10 days | Rectal bleeding ceased, recurrent abdominal pain; no follow-up |

| 7/male | Healthy | Abdominal pain, diarrhea | Slight proctitis | IS | Doxycycline (200 mg for 1 day, then 100 mg/day for 8 days) | Persistent abdominal symptoms, eradication of spirochetes | |

| 4/female | Healthy | Mucus and bloody stools | Proctitis, juvenile polyps | IS | Clarithromycin (50 mg/kg/day × 10 days) | Improvement | |

| 10/female | Healthy | Blood-stained diarrhea | Hyperemic membranes on rectoscopy | IS | Clarithromycin | Resolution | |

| 13/male | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea, weight loss, blood-stained stools | Slight inflammation of rectum | IS and HP-positive gastritis | Omeprazole | No improvement | |

| Clarithromycin, amoxicillin, omeprazole | Improvement with relapse | ||||||

| Clarithromycin, metronidazole, omeprazole | Sustained improvement | ||||||

| 8/male | Healthy | Abdominal pain | Juvenile polyp | IS | Penicillin V | No improvement | |

| Erythromycin (40-50 mg/kg/day × 10 days) | Resolution | ||||||

| 15/female | Healthy | Abdominal pain, blood-stained stools | Normal | IS | Clarithromycin 500 mg, BID for 2 weeks | Relieved discomfort,bleeding persisted; spirochetes eradicated | |

| 14/female | Healthy | Abdominal pain | Normal colonoscopy, HP-positive gastritis | IS | Ranitidine + amoxicillin | No improvement | |

| Metronidazole | No improvement of symptoms, IS eradicated | ||||||

| 200144 | 12/male | Healthy | Vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss | Normal | IS with mild focal colitis | Metronidazole and amoxicillin for 1 week | Resolution |

| 12/male | Healthy | Abdominal pain | Normal | IS | Penicillin V and metronidazole (1 week) | Symptoms persisted | |

| Metronidazole (800 mg 3×/day for 1 week) | Improvement | ||||||

| 16/female | Healthy | Right upper quadrant pain | Normal | IS | Metronidazole (10 days) | Resolution | |

| 9.5/female | Healthy | Diarrhea, bright rectal bleeding | Normal | IS | Amoxicillin and metronidazole (10 days) | Resolution | |

Abbreviations: IS, intestinal spirochetosis; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; CT, computed tomography; PO, per os; IM, intramuscular; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; HSV, herpes simplex virus; BID, twice a day.

Cases were limited to nonsyphilitic spirochetosis.

One crucial observation in our case is that the presence of colonic spirochetosis is found on mucosa adjacent to colonic polyps. This leads to the question of whether there is any association between IS and colonic polyps. Omori et al conducted a retrospective case-control study to determine the prevalence of IS in sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/Ps) in 19 SSA/P cases and 172 controls.13 They found that the rate of IS was significantly higher in the SSA/P cases (52.6%, 10/19 cases) compared to that in controls (8.1%, 14/172), suggesting the potential association between IS and SSA/Ps. The finding from this study is similar to results from an Italian study in which the authors also proposed an association between IS and hyperplastic/adenomatous colonic polyps.14 Further studies are needed to determine the implications of IS and the presence of colonic polyps.

The endoscopic examination of colonic mucosa has limited value in making diagnosis of IS. In a study of 15 cases with biopsy-proven IS, colonoscopic findings were normal in 6 subjects and nonspecific in the remaining cases (7 with polypoid lesions, 1 with erythematous mucosa, and 1 with questionable lesion).15 In general, IS cannot be detected with routine colonoscopy. However, a recent study showed the potential of in vivo diagnosis of IS using confocal endomicroscopy with fluorescein sodium as a contrasting agent and Acriflavine hydrochloride,as a topical agent to highlight superficial cell borders and nuclei.16 Using this technique, the spirochetes become visible as bright ring-like bands within the lumina of the crypts.16 Of note, in clinical practice, IS is normally found coincidentally in biopsies taken from areas of intestinal mucosa with an irregular appearance. However, in the majority of cases, it is discovered during random biopsies of normal appearing colonic mucosa.5 The histological apperances of IS on biopsy specimens using H&E stain is a diffuse blue fringe, approximately 3 to 6 µm thick, along the border of the intercryptal epithelial layer (Figures 1 and 2).5 The presence of spirochetes can be confirmed with Warthin-Starry stain (Figure 3).

The decision on whether to treat IS should be tailored to the clinical presentation, the severity of the patients’ symptoms, and their immune status.5,6,11 IS can either present asymptomatically, as the organisms responsible are thought to have a commensal relationship with normal gut flora, or symptomatically with associated GI symptoms, as the organisms can also have an invasive, pathogenic form (Table 1). For the former presentation and in a patient such as the one we present, a “wait-and-see” observational approach without any interventions is appropriate. For symptomatic patients, medical treatment with metronidazole (500 mg 4 times a day for 10 days) has been shown to be beneficial.5,6

In conclusion, IS can be found accidentally from colonic biopsies, and, in most cases, there is no correlation with clinical symptoms. The association of IS and the presence of colonic polyps has been reported, though further investigation is required to confirm these anecdotal findings. Most cases can be followed without specific treatment. For symptomatic cases, metronidazole is an effective treatment of choice.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Authors Taiwo Ngwa and Jennifer L. Peng share co-first authorship. Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Wolgemuth CW. Flagellar motility of the pathogenic spirochetes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;46:104-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lo TC, Heading RC, Gilmour HM. Intestinal spirochaetosis. Postgrad Med J. 1994;70:134-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lin RK, Miyai K, Carethers JM. Symptomatic colonic spirochaetosis in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:1100-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harland WA, Lee FD. Intestinal spirochaetosis. Br Med J. 1967;3:718-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsinganou E, Gebbers JO. Human intestinal spirochetosis—a review. Ger Med Sci. 2010;8:Doc01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Mook WN, Koek GH, van der Ven AJ, Ceelen TL, Bos RP. Human intestinal spirochaetosis: any clinical significance? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:83-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tateishi Y, Takahashi M, Horiguchi S, et al. Clinicopathologic study of intestinal spirochetosis in Japan with special reference to human immunodeficiency virus infection status and species types: analysis of 5265 consecutive colorectal biopsies. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lindboe CF. The prevalence of human intestinal spirochetosis in Norway. Anim Health Res Rev. 2001;2:117-119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Delladetsima K, Markaki S, Papadimitriou K, Antonakopoulos GN. Intestinal spirochaetosis. Light and electron microscopic study. Pathol Res Pract. 1987;182:780-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tompkins DS, Foulkes SJ, Godwin PG, West AP. Isolation and characterisation of intestinal spirochaetes. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:535-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Korner M, Gebbers JO. Clinical significance of human intestinal spirochetosis—a morphologic approach. Infection. 2003;31:341-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sato H, Nakamura S, Habano W, Wakabayashi G, Adachi Y. Human intestinal spirochaetosis in northern Japan. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:791-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Omori S, Mabe K, Hatanaka K, et al. Human intestinal spirochetosis is significantly associated with sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210:440-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Calderaro A, Gorrini C, Montecchini S, et al. Intestinal spirochaetosis associated with hyperplastic and adenomatous colonic polyps. Pathol Res Pract. 2012;208:177-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alsaigh N, Fogt F. Intestinal spirochetosis: clinicopathological features with review of the literature. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:97-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gunther U, Epple HJ, Heller F, et al. In vivo diagnosis of intestinal spirochaetosis by confocal endomicroscopy. Gut. 2008;57:1331-1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Honaker M, Paton BL, Kamionek M, Schiffern L. Spirochetosis resulting in fulminant colitis. Surgery. 2015;158:1738-1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Akiyama S, Kikuchi D, Mitani T, et al. A case of mucinous adenocarcinoma in the setting of chronic colitis associated with intestinal spirochetosis and intestinal stricture. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iwamoto J, Ogata S, Honda A, et al. Human intestinal spirochaetosis in two ulcerative colitis patients. Intern Med. 2014;53:2067-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kantekure K, Tischler A. Intestinal spirochetosis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2014;22:709-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lalit K, Hasan M, Charanjit K. Intestinal spirochetosis as a causative factor for colocolic intussusception. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1351-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Panackel C, Sebastian B, Mathai S, Thomas R. Intestinal spirochaetosis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:902-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higashiyama M, Ogata S, Adachi Y, et al. Human intestinal spirochetosis accompanied by human immunodeficiency virus infection: a case report. Acta Med Okayama. 2009;63:217-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsuzawa K, Fujisawa N, Sekino Y, et al. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: colonic spirochetosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suarez-Penaranda JM, Macias-Garcia F, Llovo J, Forteza J. Histopathological diagnosis of intestinal spirochetosis in a nonimmunocompromised patient. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18:73-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Calderaro A, Bommezzadri S, Gorrini C, et al. Infective colitis associated with human intestinal spirochetosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1772-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Umeno J, Matsumoto T, Nakamura S, et al. Intestinal spirochetosis due to Brachyspira pilosicoli: endoscopic and radiographic features. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:253-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Esteve M, Salas A, Fernandez-Banares F, et al. Intestinal spirochetosis and chronic watery diarrhea: clinical and histological response to treatment and long-term follow up. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1326-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lima MA, Barbosa AL, Santos VM, Misiara FP. Intestinal spirochetosis and colon diverticulosis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:56-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martinez MW, Petre S, Wisinger D, Temesgen Z. Intestinal spirochetosis and diarrhea, commensal or causal. AIDS. 2004;18:2441-2442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Korner M, Gebbers JO. Spirochaetes within the cysts of pneumatosis coli. Histopathology. 2004;45:199-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kanavaki S, Mantadakis E, Thomakos N, et al. Brachyspira (Serpulina) pilosicoli spirochetemia in an immunocompromised patient. Infection. 2002;30:175-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shah RN, Stosor V, Badve S. Pathologic quiz case. Colon biopsy in a patient with diarrhea—possible etiologic agent. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:699-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Palejwala AA, Evans R, Campbell F. Spirochaetes can colonize colorectal adenomatous epithelium. Histopathology. 2000;37:284-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peghini PL, Guccion JG, Sharma A. Improvement of chronic diarrhea after treatment for intestinal spirochetosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1006-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakamura S, Kuroda T, Sugai T, et al. The first reported case of intestinal spirochaetosis in Japan. Pathol Int. 1998;48:58-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Padmanabhan V, Dahlstrom J, Maxwell L, Kaye G, Clarke A, Barratt PJ. Invasive intestinal spirochetosis: a report of three cases. Pathology. 1996;28:283-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Helbling R, Osterheld MC, Vaudaux B, Jaton K, Nydegger A. Intestinal spirochetosis mimicking inflammatory bowel disease in children. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walia R, Shuja C, Hong D, et al. An unusual cause of abdominal pain. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:e141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carpentieri DF, Souza-Morones S, Gardetto JS, et al. Intestinal spirochetosis in children: five new cases and a 20-year review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2010;13:471-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. King NR, Fidda N, Gourley G. Colorectal spirochetosis in a child with rectal bleeding: case report and literature review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:673-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nodit L, Parizhskaya M. Intestinal spirochetosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:823-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marthinsen L, Willen R, Carlen B, Lindberg E, Varendh G. Intestinal spirochetosis in eight pediatric patients from Southern Sweden. APMIS. 2002;110:571-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Heine RG, Ward PB, Mikosza AS, Bennett-Wood V, Robins-Browne RM, Hampson DJ. Brachyspira aalborgi infection in four Australian children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:872-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]