Abstract

Background

A new generation of highly navigable large-bore aspiration catheters and retriever devices for intracranial mechanical thrombectomy has markedly improved recanalization rates, time and clinical outcomes. We report collected clinical data utilizing a new technique based on combined large lumen aspiration catheter and partially resheathed stent retriever (ARTS: Aspiration (catheter)–(stent) Retriever Technique for Stroke). This technique is applied, especially in presence of bulky/rubbery emboli, when resistance is felt while retracting the stent retriever; at that point the entire assembly is locked and removed in-toto under continuous aspiration with additional flow arrest.

Methods

A retrospective data analysis was performed to identify patients with large cerebral artery acute ischemic stroke treated with ARTS. The study was conducted between August 2013 and February 2015 at a single high volume stroke center. Procedural and clinical data were captured for analysis.

Results

Forty-two patients (median age 66 years) met inclusion criteria for this study. The ARTS was successful in achieving Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (TICI) ≥2b revascularization in 97.6% of cases (TICI 2b = 18 patients, TICI 3 = 23 patients). Patients’ median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score at admission was 18 (6–40). A 3-month follow-up modified Rankin Scale value of 0–2 was achieved in 65.7% of the successfully treated patients (average 2.4). Two patients (4.8%) developed symptomatic intraparenchymal hemorrhages. Six procedure unrelated deaths were observed.

Conclusions

We found that ARTS is a fast, safe and effective method for endovascular recanalization of large vessel occlusions presenting within the context of acute ischemic stroke.

Keywords: Stroke, stent retriever, aspiration catheter, mechanical thrombectomy, TICI

Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is not only one of the worldwide leading causes of disability and mortality but is also a significant burden on health systems.1,2 Original experience with intra-arterial thrombolysis (such as with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (TPA)) as well as the use of first generation endovascular devices as a strategy for recanalization of large arterial occlusions in AIS patients raised concerns about their efficacy. However, recent advances in catheter technology and development of large, easily trackable aspiration thrombectomy catheters as well as latest generations of stent retrievers resulted in earlier and more efficient revascularization of large arterial occlusions and subsequent improved clinical outcomes.

Aspiration thrombectomy, utilizing flexible and highly navigable large bore distal access catheters (5 Max ACE, Penumbra, Alameda, California, USA) combined with mechanical thrombectomy, performed with stent retrievers (Solitaire FR, EV3 Neurovascular, Irvine, California, USA; Trevo, Stryker Neurovascular, Freemont, California, USA) has improved the recanalization time and rates as well as clinical outcomes when compared with older generations of thrombectomy devices (MERCI, Concentric Medical, Mountain View, California, USA).3,4

In clinical practice failure of endovascular treatment is primarily related to the inability to effectively remove an occlusive thrombus, thrombus fragmentation with distal migration, and prolonged revascularization time.

Relying on the hypothesis that a combined thrombectomy procedure, utilizing the Aspiration (catheter)–(stent) Retriever Technique for Stroke (ARTS) treatment, may improve recanalization rates and time, we performed a retrospective monocenter analysis of procedure and clinical data.

Materials and methods

This monocenter retrospective study evaluated 42 consecutive patients treated for AIS over a 19-month period between August 2013 and February 2015.

Patient selection for endovascular treatment was based on advanced imaging with computed tomography (CT)/CT angiography and CT perfusion.5 In the event of undetermined symptoms onset (“wake-up stroke”) or posterior circulation ischemia diagnostic imaging was implemented with brain MRI including diffusion weighted imaging sequences.

Patients included in this series were found to have a large cerebral vessel occlusion with viable ischemic penumbra and ischemic infarction of less than one-third of the vascular territory supplied by the occluded target artery. Both anterior and posterior circulation AIS were included.

Procedural and clinical data of the subgroup of patients undergoing endovascular treatment of AIS with combined stent retriever device and large bore aspiration catheter (5 Max ACE) were recorded for evaluation.

Technique: ARTS

Access to the cerebral vasculature required a 6 French Neurosheath, usually a Shuttle (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, Indiana, USA) or a Neuron 088 Max (Penumbra, Oakland, California, USA), or an 8–9 French Balloon Guiding Catheter, usually a 9F Cello (Covidien, EV3 Neurovascular, Irvine, California, USA) or an 8F FlowGate (Stryker, Stryker Neurovascular, Freemont, California, USA).

The Neuron Max and the FlowGate were advanced as far distally into the internal carotid artery (ICA) as safely possible, usually to the skull base or petrous segment, whereas the Shuttle and Cello tips were positioned at the proximal third of the cervical ICA. For posterior circulation occlusion, only the Neuron 088 and FlowGate were used and navigated through the dominant vertebral artery into the distal V2 segment.

The Penumbra 5 Max ACE reperfusion catheter (Penumbra) was selected for carotid terminus, middle cerebral artery (MCA) M1 segment, basilar and posterior cerebral artery (PCA) P1 segment occlusions. Using a triaxial technique, the 5 Max ACE was advanced over a microcatheter (most commonly Excelsior XT-27 (Stryker) and 3 Max reperfusion catheter (Penumbra)) and microwire (0.014 inch Synchro2 wire (Stryker)) to the level of the thrombus. Initially, under biplane roadmap guidance, the wire and microcatheter were navigated through the thrombus into the proximal M2 trunks of the MCA or P2 segment of the PCA. Over this platform, the 5 Max ACE aspiration catheter was delivered and positioned immediately proximal to the site of occlusion. Initially in the study, if the ADAPT technique failed,6,7 especially in presence of cardio-embolic rubbery clots, the ARTS was attempted. A stent retriever device, such as Trevo XP or ProVue (Stryker) or Solitaire2 (Covidien), selected according to labeling indications, was placed across the thrombus and allowed to intercalate within the clot for 4 min (Figure 1). In most cases, the delivery microcatheter was removed before thrombus extraction, in order to increase the cross sectional luminal area and consequently the interaction between stent retriever/5 Max ACE and the suction surface. Before activating the Penumbra aspiration pump apparatus the balloon guiding catheter, if used, was inflated.8 When resistance was felt while retracting the stent retriever, the entire assembly (5 Max ACE aspiration catheter and the partially resheathed stent retriever) was locked and slowly withdrawn under continuous aspiration with additional flow arrest4,9,10 (Figure 2). Subsequent follow-up angiograms were performed to evaluate revascularization and the procedure was repeated as necessary.

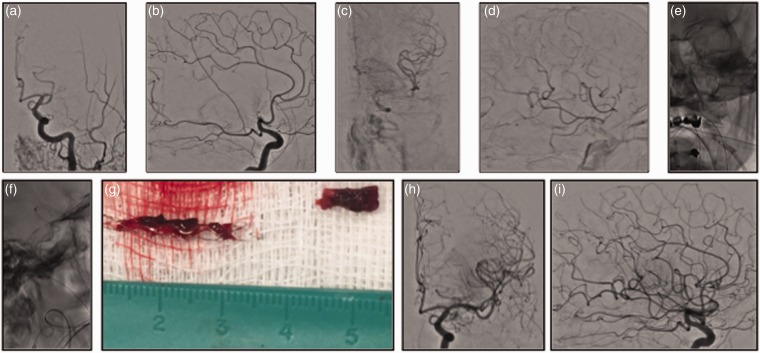

Figure 1.

Left middle cerebral artery M1 occlusion ((a) and (b)) with partial and delayed middle cerebral artery territory perfusion via ipsilateral anterior cerebral artery cortico-pial collateral supply ((c) and (d)). National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score 20 at admission. Aspiration–Retriever Technique for Stroke allowed removal ((e) and (f)) of the photographed specimen ((g)) with final Thrombolysis in Cerebral Ischemia 3 recanalization at control angiogram ((h) and (i)). Modified Rankin Scale score at discharge and 90 days respectively of 3 and 2.

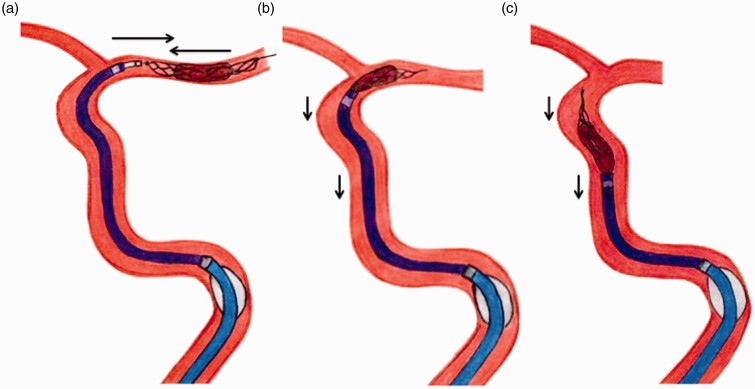

Figure 2.

Illustration of the Aspiration–Retriever Technique for Stroke in a middle cerebral artery M1 occlusion. (a) The Max ACE aspiration catheter is navigated into the patent segment of the middle cerebral artery to face the thrombus. A stent retriever device is placed across the thrombus and allowed to intercalate within the clot. Before activating the Penumbra aspiration pump apparatus the balloon guiding catheter, if used, is inflated. (b), (c) When resistance is felt while retracting the stent retriever, the entire assembly (5 Max ACE aspiration catheter and the partially resheathed stent retriever) is locked and slowly withdrawn under continuous aspiration with additional flow arrest.

Data collection and analysis

Multiple demographic, clinical and imaging variables were collected. The degree of vessel occlusion at presentation and after treatment was defined by the modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (TICI) classification and adjudicated by the operator. Procedure time, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH), National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score at admission, and functional outcomes were also recorded.

Successful revascularization was defined as post-procedural TICI score ≥2b. Procedure time was defined as the time from groin access to at least TICI 2b revascularization. sICH was determined as presence of post-treatment hemorrhage with associated worsening of NIHSS ≥4 points on clinical examination. A good functional outcome was represented by a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of ≤2 at 90-day follow-up. Mortality was defined as patient decease occurring within 90 days from initial presentation.

Results

Patient demographics and procedural data

Between August 2013 and February 2015, forty-two consecutive cases of acute ischemic stroke were treated with ARTS at our institution: 34 involving the anterior circulation and eight involving the posterior circulation. The sites of occlusion at the time of angiography included the M1 (left (L) = 20, right (R) = 7) and M2 (L = 2) segments of the MCA, ICA terminus (L = 3, R = 2), basilar artery (n = 5) and dominant/patent vertebral artery (n = 3). The patient cohort included 23 women and 19 men, with a median age of 66 years (SD = 16.9). The average time from symptom onset to groin puncture was 8 h (mean 493 min; median 360 min, SD = 340 min). In 10 cases (23.8%) the symptom onset was undetermined (“wake-up stroke”). The median presenting NIHSS score was 18 (range 6–40). Three patients were treated, despite an NIHSS value below the standard threshold of 8 (one patient = 6; two patients = 7), regarding the primary involvement of the patient’s speech and firm request from patients and family members to proceed with the endovascular treatment. Approximately 43% of patients (n = 18) had received in vitro (IV) TPA. Two stent retriever devices were used in conjunction with the 5 Max ACE aspiration catheter: Trevo (n = 38) and Solitaire (n = 17). In the vast majority of cases a 4 mm × 20 mm device was used. A combination of Trevo and Solitaire was used in 13 patients.

Success rate in navigating the aspiration catheter facing the proximal aspect of the thrombus, before starting stent retraction, was 100%.

Approximately 43% of patients (18/42) achieved successful recanalization with one single pass. The average number of passes required to achieve final recanalization was 2.2. With progressive systematic use of ARTS as first choice technique, there was a significant reduction in number of passes/procedures, decreasing to an average of 1.4 in the last 15 patients (11/15; 73.3% of single pass/2b-3 recanalization rate) (Figure 3).

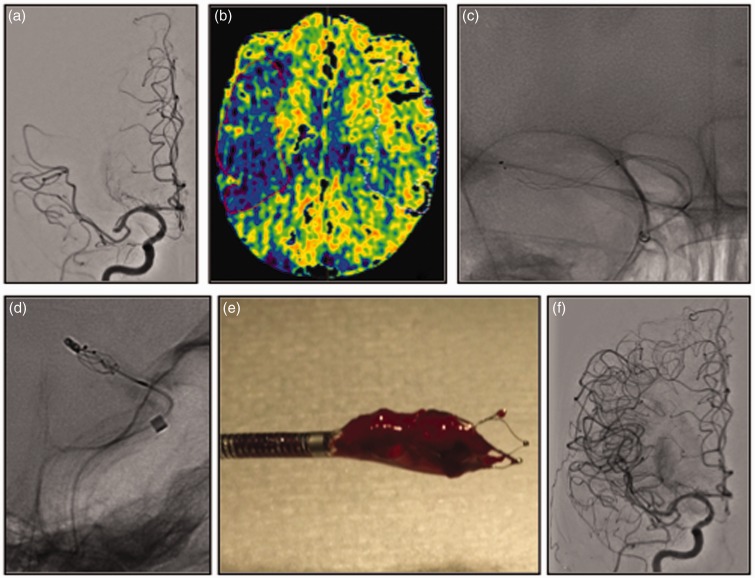

Figure 3.

Right middle cerebral artery M1 occlusion distal to the origin of the anterior temporal artery ((a)). Cone beam CT perfusion suggested a large area of penumbra ((b)). National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score 14 at admission. The Aspiration–Retriever Technique for Stroke allowed removal ((c), (d)) of the photographed specimen ((e)) with final Thrombolysis in Cerebral Ischemia 3 recanalization at control angiogram ((f)). Modified Rankin Scale score at discharge and 90 days respectively of 4 and 2.

The overall successful revascularization rate (TICI 2b-3) was 97.6 % of cases (TICI 2b = 18 patients, TICI 3 = 23 patients). TICI 3 recanalization was achieved 54.7 % of the time. Partial recanalization (TICI 2a) was achieved in one patient (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients cohort clinical, procedural and outcomes data.

| Patient number | Age (years) | Gender | NIHSS admission | IV tPA | Site occlusion | Tandem lesions | Guide Catheter | Intracranial angioplasty/stent | Final TICI score | Distal emboli | Intraprocedure SAH | sICH | mRS discharge | mRS F/U (90 days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75 | M | 22 | Y | Basilar-Apex | N | NMAx | Angioplasty | 2B | N | N | N | 5 | 6 |

| 2 | 70 | F | 26 | Y | L M1 | N | Shuttle | N | 2A | N | N | N | 4 | 3 |

| 3 | 58 | F | 6 | N | L M1 | ICA diss | Shuttle | N | 2B | N | N | N | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 67 | M | 16 | N | R M1 | N | Cello | N | 2B | N | N | N | 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 66 | F | 20 | Y | L M1 | N | Cello | N | 2B | M3 | N | N | 2 | 0 |

| 6 | 66 | F | 20 | Y | L M1 | N | Shuttle | Angio/Stent | 2B | N | N | N | 2 | 0 |

| 7 | 61 | M | 20 | N | L M2 | ICA diss | Shuttle | N | 2B | N | N | N | 5 | 3 |

| 8 | 68 | F | 14 | N | L M1 | N | Cello | N | 2B | N | N | N | 4 | 3 |

| 9 | 65 | M | 7 | N | Basilar-Apex | N | NMAx | N | 3 | N | N | N | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 61 | M | 12 | N | R M1 | N | Cello | N | 2B | N | Y | Y | 4 | 2 |

| 11 | 68 | M | 20 | Y | L ICA-T | N | Cello | Angioplasty | 3 | N | N | N | 2 | 3 |

| 12 | 48 | F | 8 | N | L M1 | N | Shuttle | N | 2B | N | N | N | 3 | 2 |

| 13 | 63 | F | 15 | N | L M1 | N | Cello | N | 3 | N | N | N | 3 | 6 |

| 14 | 84 | F | 19 | N | L M1 | N | NMAx | N | 2B | N | N | N | 5 | LFU |

| 15 | 57 | M | 20 | Y | R M1 | N | Shuttle | N | 3 | N | N | Y | 5 | 2 |

| 16 | 44 | F | 13 | Y | L M1 | N | Cello | N | 3 | N | N | N | 5 | 4 |

| 17 | 80 | F | 17 | N | R ICA-T | N | Cello | N | 2B | N | N | N | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | 73 | F | 18 | N | L ICA-T | N | Cello | N | 3 | N | N | N | 5 | 4 |

| 19 | 90 | F | 19 | N | Basilar-Apex | N | NMAx | Stenting | 2B | N | N | N | 5 | 4 |

| 20 | 66 | M | 19 | N | L ICA-T | ICA ath | Cello | N | 3 | N | Y | N | 2 | 1 |

| 21 | 62 | F | 7 | N | R ICA-T | N | Cello | N | 2B | N | N | N | 1 | 0 |

| 22 | 20 | F | 11 | N | L M1 | ICA diss | Shuttle | N | 3 | N | N | N | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | 70 | M | 14 | Y | R M1 | N | Cello | N | 3 | N | N | N | 4 | 2 |

| 24 | 66 | M | 10 | Y | L M1 | ICA ath | Cello | N | 3 | N | N | N | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | 82 | F | 23 | N | R M1 | N | Cello | N | 2B | N | N | N | 5 | 5 |

| 26 | 89 | F | 17 | Y | L M1 | N | FlowGate | N | 3 | N | N | N | 6 | 6 |

| 27 | 80 | F | 29 | N | L M1 | N | FlowGate | N | 3 | N | N | N | 4 | 3 |

| 28 | 27 | F | 22 | N | L M1 | N | Cello | N | 2B | L ACA | N | N | 2 | 2 |

| 29 | 33 | F | 20 | N | L M1 | N | Cello | N | 3 | N | N | N | 3 | 2 |

| 30 | 41 | M | 22 | N | L M1 | ICA diss | FlowGate | N | 3 | N | N | N | 2 | 2 |

| 31 | 90 | F | 25 | Y | L M1 | N | FlowGate | N | 3 | N | N | N | 4 | 3 |

| 32 | 72 | M | 19 | Y | Basilar-Apex | N | FlowGate | N | 3 | N | N | N | 4 | LFU |

| 33 | 68 | F | 24 | Y | L M1 | N | FlowGate | N | 2B | M4 | N | N | 2 | LFU |

| 34 | 69 | M | 13 | Y | VBJ (R VT occl) | N | NMAx | N | 3 | N | N | N | 1 | 1 |

| 35 | 49 | M | 28 | Y | VBJ (Bil VT occl) | N | NMAx | Stenting | 3 | N | N | N | 6 | 6 |

| 36 | 41 | M | 40 | Y | Basilar-Apex | VT diss | NMAx | N | 3 | N | N | N | 6 | 6 |

| 37 | 50 | M | 15 | Y | R M1 | N | FlowGate | N | 2B | N | N | N | 4 | 1 |

| 38 | 58 | M | 32 | N | L M1 | ICA diss | FlowGate | N | 2B | N | N | N | 5 | 2 |

| 39 | 34 | M | 17 | Y | L M2 | ICA diss | FlowGate | N | 3 | N | N | N | 2 | 1 |

| 40 | 61 | F | 14 | N | VBJ (L VT occl) | N | NMAx | Angio/Stent | 3 | N | N | N | 4 | 2 |

| 41 | 77 | F | 17 | N | R M1 | N | FlowGate | N | 3 | N | N | N | 6 | 6 |

| 42 | 88 | M | 16 | N | L M1 | N | FlowGate | Angioplasty | 3 | N | N | N | 3 | 2 |

ICA ath: ICA atherosclerotic stenosis; ICA diss: ICA dissection; IV tPA: IntraVenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator; LFU: lost to follow-up; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SAH: SubArachnoid Hemorrhage; sICH: symptomatic intra-cranial hemorrhage; TICI: Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction; VT diss: vertebral artery dissection.

The average time from groin puncture to at least TICI 2b recanalization was 65 min (range 17–182 min).

In nine patients (21.5 %), the association of a severe ICA stenosis/occlusion (two of which were due to severe extracranial atherosclerotic disease and six due to an underlying carotid dissection) or vertebral artery dissection (n = 1) and intracranial large vessel occlusion (tandem lesions) required deployment of a stent along the cervical segment of the internal carotid/vertebral artery.11

To preserve the restored patency of severely atherosclerotic or dissected intracranial vessels, three patients received angioplasty, two underwent stent placement and two were treated with a combination of angioplasty and stenting. A total of five stents, four Neuroform EZ3 (Stryker, Stryker Neurovascular, Freemont, California, USA) and one Resolute Integrity (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), were deployed in four patients.

When the procedure was performed exclusively with ARTS, two of 42 (4.7 %) cases had downstream emboli within the initially affected territory, along M3 and M4 MCA branches respectively, one (M3) successfully treated with intra-arterial thrombolytic drug infusion. There was one embolization to a new territory (left anterior cerebral artery), which was successfully treated with stent retriever thrombectomy.

A small subarachnoid hemorrhage was observed in two cases (4.8%) as a procedural complication during stent retriever withdrawal; however, without affecting patient clinical outcome. There were two (4.8%) symptomatic intraparenchymal hemorrhages (both centered within the right fronto-parietal region). One extracranial vertebral artery iatrogenic dissection was observed and successfully treated with placement of two overlapping Xience Alpine drug eluting stents (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA). There were four deaths before hospital discharge: three due to cerebral infarction sequelae and one due to cardiac arrest. Two patients had died by 90-day follow up: one secondary to sequelae of cerebral infarction and another due to decompensated congestive heart failure.

A total of 35 patients had a follow-up at 90 days. Among patients with follow-up, 23 (65.7%) had a favorable outcome (mRS 0–2); 10 patients (28.5%) had an mRS score of 3–5.

Three patients were lost to follow-up. At three-month follow-up the mean mRS value was 2.4 (Table 1).

Discussion

A new generation of mechanical embolectomy devices has demonstrated increasing rates of recanalization and subsequent improved clinical outcomes. Recent technological advances include the development of highly navigable large bore aspiration catheters12–14 as well as improvements in stent retriever design.15,16

Further increment in internal diameter of the 5 Max ACE aspiration catheter results in an increased surface area providing optimization in catheter tip–thrombus contact.17,18 In addition, the more capacious catheter proximal segment, implementing the luminal volume, provides an augmented aspiration capacity compared with previous generations of aspiration catheters.6,19

In the last decade, after the Food and Drug Administration cleared the MERCI device in August 2004 for acute AIS treatment,20,21 stent retriever configuration has been completely redesigned in order to improve clot integration, visibility, accurate and atraumatic placement and retrieval. Single or combined utilization of these thrombectomy systems (Penumbra, Solitaire, and Trevo) resulted in a technical efficacy and safety improvement as well as superior clinical outcomes when compared with MERCI.15,16,22 These improvements are likely synergistic effects of ease of use, speed of deployment, atraumatic design, and efficacy of clot removal.23 Nevertheless, it has been reported that single embolectomy device use is associated with a higher incidence of clot fragmentation with embolization to new or downstream territories (7–9% of cases in the SWIFT and TREVO trials, and up to 14% in subsequent registries; 10% of cases in ADAPT series). The ARTS has been specifically tailored to promote intracranial thrombus extraction, especially in presence of large “rubbery” cardiac emboli, and minimize iatrogenic embolic distal vessel occlusion (7.1% in our series). The ARTS was always preceded by removal of the delivery microcatheter from a 5 Max ACE catheter, resulting in larger cross sectional surface area for thrombus aspiration, thereby substantially increasing the suction force during the stent retriever device withdrawal. Then, after partially resheathing the stent retriever within the 5 Max ACE aspiration catheter, the complete assembly was slowly withdrawn under constant aspiration.

In those cases in which a stent was deployed along the cervical segment of the internal carotid artery to treat an underlying severe ICA stenosis/occlusion, the guiding catheter tip was advanced distal to the stent, in order to prevent the stent retriever–aspiration catheter assembly from getting caught in the carotid stent during retraction.

In 27 cases (64.3%) the ARTS was associated to balloon guiding catheter inflation at the proximal segment of cervical internal carotid or vertebral artery. The utilization of the ARTS provides several advantages, notably the “anchorage” produced by the exposed portion of the stent retriever on the mid-distal portion of the embolus, the avoidance of apple-coring effect produced by forced retraction of the stent retriever/bulky calcified or highly organized clot combination within the 5 Max ACE aspiration catheter, and localized suction along the proximal edge of the thrombus. Disadvantages of the ARTS entail the necessity to renegotiate catheter position in the event that a second pass is needed, a time consuming maneuver particularly in cases with challenging cervical-cerebral anatomy, and the need to retract the assembly along the entire cervical ICA and, potentially, in the case of tandem occlusion, through the proximal carotid stent.

There are significant limitations to this study, including the small initial experience population, the retrospective and non-randomized nature of the analysis, the absence of a control group and the involvement of a single center.

Conclusions

The findings of this study support the hypothesis that the combination of evolving technology and “creative” technical nuances significantly impacted angiographic and clinical outcomes in AIS patient management. Mechanical thrombectomy in conjunction with ARTS is a fast, safe and effective method for endovascular recanalization of large vessel occlusions presenting within the context of AIS.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Rha JH, Saver JL. The impact of recanalization on ischemic stroke outcome: A meta-analysis. Stroke 2007; 38: 967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fargen KM, Meyers PM, Khatri P, et al. Improvements in recanalization with modern stroke therapy: A review of prospective ischemic stroke trials during the last two decades. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5: 506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walcott BP, Boehm KM, Stapleton CJ, et al. Retrievable stent thrombectomy in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke: Analysis of a revolutionizing treatment technique. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20: 1346–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humphries W, Hoit D, Doss VT, et al. Distal aspiration with retrievable stent assisted thrombectomy for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turk AS, Magarick JA, Frei D, et al. CT perfusion-guided patient selection for endovascular recanalization in acute ischemic stroke: A multicenter study. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5: 523–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turk AS, Spiotta A, Frei D, et al. Initial clinical experience with the ADAPT technique: A direct aspiration first pass technique for stroke thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turk AS, Frei D, Fiorella D, et al. ADAPT FAST study: A direct aspiration first pass technique for acute stroke thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen TN, Malisch T, Castonguay AC, et al. Balloon guide catheter improves revascularization and clinical outcomes with the Solitaire device: Analysis of the North American Solitaire Acute Stroke Registry. Stroke 2014; 45: 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgado Almandoz JE, Kayan Y, Young ML, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes in patients with acute ischemic strokes treated with mechanical thrombectomy using either Solumbra or ADAPT techniques. J Neurointerv Surg 2015. Epub ahead of print, doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-012122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chueh JY, Puri AS, Wakhloo AK, et al. Risk of distal embolization with stent retriever thrombectomy and ADAPT. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: 197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu GF, Suh DC, Choi CG, et al. Aspiration thrombectomy of acute complete carotid bulb occlusion. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2005; 16: 539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jankowitz B, Aghaebrahim A, Zirra A, et al. Manual aspiration thrombectomy: Adjunctive endovascular recanalization technique in acute stroke interventions. Stroke 2012; 43: 1408–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jankowitz BT, Aleu A, Lin R, et al. Endovascular treatment of basilar artery occlusion by manual aspiration thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg 2010; 2: 110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiotta AM, Hussain MS, Sivapatham T, et al. The versatile distal access catheter: The Cleveland Clinic experience. Neurosurgery 2011; 68: 1677–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davalos A, Pereira VM, Chapot R, et al. Retrospective multicenter study of Solitaire FR for revascularization in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2012; 43: 2699–2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira VM, Gralla J, Davalos A, et al. Prospective, multicenter, single-arm study of mechanical thrombectomy using Solitaire Flow Restoration in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2013; 44: 2802–2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frei D, Gerber J, Turk A, et al. The SPEED study: Initial clinical evaluation of the Penumbra novel 054 reperfusion catheter. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5(Suppl. 1): i74–i76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarr R, Hsu D, Kulcsar Z, et al. The POST trial: Initial post-market experience of the Penumbra system: Revascularization of large vessel occlusion in acute ischemic stroke in the United States and Europe. J Neurointerv Surg 2010; 2: 341–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turk AS, III, Campbell JM, Spiotta A, et al. An investigation of the cost and benefit of mechanical thrombectomy for endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nogueira RG, Lutsep HL, Gupta R, et al. Trevo versus Merci retrievers for thrombectomy revascularisation of large vessel occlusions in acute ischaemic stroke (TREVO 2): A randomised trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 1231–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saver JL, Jahan R, Levy EI, et al. Solitaire flow restoration device versus the Merci retriever in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (SWIFT): A randomised, parallel-group, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 1241–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaidat OO, Castonguay AC, Gupta R, et al. North American Solitaire Stent Retriever Acute Stroke registry: Post-marketing revascularization and clinical outcome results. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: 584–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chueh JY, Wakhloo AK, Gounis MJ. Effectiveness of mechanical endovascular thrombectomy in a model system of cerebrovascular occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 1998–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]