Abstract

Objective

The existing literature regarding preoperative cervical spinal tumor embolization is sparse, with few discussions on the indications, risks, and best techniques. We present our experience with the preoperative endovascular management of hypervascular cervical spinal tumors.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of all patients who underwent preoperative spinal angiography (regardless of whether tumor embolization was performed) at our institution (from 2002 to 2012) for primary and metastatic cervical spinal tumors. Tumor vascularity was graded from 0 (tumor blush equal to the normal adjacent vertebral body) to 3 (intense tumor blush with arteriovenous shunting). Tumors were considered “hypervascular” if they had a tumor vascular grade from 1 to 3. Embolic materials included particles, liquid embolics, and detachable coils. The main embolization technique was superselective catheterization of an arterial tumor feeder followed by injection of embolic material. This technique could be used alone or supplemented with occlusion of dangerous anastomoses of the vertebral artery as needed to prevent inadvertent embolization of the vertebrobasilar system. In cases when superselective catheterization of the tumoral feeder was not feasible, embolization was performed from a proximal catheter position after occlusion of branches supplying areas other than the tumor (“flow diversion”).

Results

A total of 47 patients with 49 cervical spinal tumors were included in this study. Of the 49 total tumors, 41 demonstrated increased vascularity (vascularity score > 0). The most common tumor pathology in our series was renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (N = 16; 32.7% of all tumors) followed by thyroid carcinoma (N = 7; 14.3% of all tumors).

Tumor embolization was undertaken in 25 hypervascular tumors resulting in complete, near-complete, and partial embolization in 36.0% (N = 9), 44.0% (N = 11), and 20.0% (N = 5) of embolized tumors, respectively. We embolized 42 tumor feeders in 25 tumors. The most commonly embolized tumor feeders were branches of the vertebral artery (19.0%; N = 8), the deep cervical artery (19.0%; N = 8), and the ascending cervical artery (19.0%; N = 8). Sixteen hypervascular tumors were not embolized because of minimal hypervascularity (8/16), unacceptably high risk of spinal cord or vertebrobasilar ischemia (4/16), failed superselective catheterization of tumor feeder (3/16), and cancellation of surgery (1/16). Vertebral artery occlusion was performed in 20% of embolizations. There were no new post-procedure neurological deficits or any serious adverse events. Estimated blood loss data from this cohort show a significant decrease in operative blood loss for embolized tumors of moderate and significant hypervascularity.

Conclusions

Preoperative embolization of cervical spinal tumors can be performed safely and effectively in centers with significant experience and a standardized approach.

Keywords: Spinal, angiography, embolization, cervical, preoperative

Introduction

The aim of preoperative tumor embolization of hypervascular lesions of the spine is to reduce the extensive intraoperative blood loss that may be associated with surgical resection. In addition to reduced intraoperative blood loss, other potential benefits of preoperative embolization include reduced operative time and improved visualization in the operative field, all of which may improve the extent of the resection and reduce surgical morbidity and mortality.

Metastatic lesions of the spine are more common than primary lesions; renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most frequently encountered hypervascular metastasis.1,2 Thus, the majority of the existing literature supporting the benefits of preoperative spinal tumor embolization has focused on RCC metastases.1,3–6 Furthermore, the existing literature primarily discusses the more prevalent thoracic/lumbar spine tumors,7 with only one large case series to date focused exclusively on preoperative embolization of cervical spinal tumors.8 The remaining publications that mention the use of preoperative embolization for cervical spinal tumors are either limited to case reports or only minimally discuss the technical aspects of embolization.9–19 The distinction between cervical spine and thoracic/lumbar spine lesions is important given that there is more complex vascular anatomy and blood supply for cervical spinal tumors; moreover, there are increased risks involved in embolization in the cervical region.7,20 In addition to the risk of inadvertent embolization of radiculomedullary arteries and resulting spinal cord ischemia, there is the risk of embolic material unintentionally traveling to the intracranial vasculature via the vertebral artery or through anastomoses with the carotid artery. Although the basic techniques are similar for cervical spine and thoracic/lumbar spinal tumor embolizations, the application of those techniques can differ greatly; additionally, care must be taken in the cervical spine region in order to avoid devastating complications. Patients with cervical spine lesions who were candidates for surgical resection (based on an attempt at tumor control or cure, spinal instability, and/or neurologic compromise)21,22 were referred for preoperative angiography and embolization if hypervascularity was suspected. In this report, we present our experience with the preoperative endovascular management of hypervascular cervical spinal tumors.

Methods

Our institutional review board approved this study. A retrospective review of all peri-procedural records and imaging for consecutive procedures performed between 2002 and 2012 was conducted. Our inclusion criteria were all patients who underwent spinal angiography (regardless of whether tumor embolization was performed) for primary and metastatic cervical spinal tumors (C1 to C7) with plans for subsequent surgical resection. Indications for angiography and potential embolization included those tumors that met our histological criteria and/or had imaging findings suspicious for hypervascular tumors. Histological criteria included benign hypervascular tumors (i.e. hemangiomas, aneurysmal bone cysts, and giant cell tumors), primary malignant hypervascular tumors (i.e. chordomas, osteosarcomas, chondrosarcomas, hemangiopericytomas, and plasmacytomas), and metastatic hypervascular tumors (i.e. RCC, thyroid carcinomas, and hepatocellular carcinomas). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings indicative of hypervascularity included intratumoral flow voids, tumoral hemorrhage, and avid contrast enhancement. Angiograms were reviewed for the type and number of identified tumor feeders, spinal artery feeders, embolized tumor feeders, type of embolic material used, and reasons for non-intervention (if embolization was not performed). The tumor vascularity was graded 0, 1, 2, or 3, where 0 = tumor blush (vascularity) equal to the normal adjacent vertebral body; 1 = tumor blush slightly more prominent than the normal vertebral body blush; 2 = considerable tumor blush without arteriovenous shunting; and 3 = intense tumor blush with arteriovenous shunting. Tumors were consider “hypervascular” if they had a tumor vascular grade from 1 to 3. If embolization was performed, a post-embolization angiogram was repeated on all tumoral feeders to assess the degree of embolization. The degree of embolization of a tumor feeder was recorded as complete if there was grade 0 or less of residual vascularity, near-complete if there was grade 1 of residual vascularity, and partial if there was grade 2 or 3 of residual vascularity. Post-procedural charts were reviewed for any complications; additionally, the final tumor pathology was reported. Estimated blood loss (EBL) during surgery was obtained from the anesthesia records. Differences between EBL were calculated using an unpaired t-test with a p value 0.05 indicative of significance. Surgical resection, with or without spinal stabilization, was typically performed one to two days following the embolization procedure.

Endovascular technique

Diagnostic angiography was performed via standard interventional neuroradiology techniques using 5 French-sized catheters. During angiography, we evaluated the vertebral arteries, subclavian arteries, and thyrocervical and costocervical trunks. For lower cervical and cervico-thoracic junction tumors, the supreme intercostal (branching from the costocervical trunk) and superior intercostal (branching from the aorta) arteries were also selectively catheterized. For upper cervical and cranio-cervical junction tumors, a common carotid artery injection was performed to evaluate the branches of the external carotid artery.

Balloon test occlusion (BTO) was performed in cases when there was a plan for vertebral artery occlusion. During the BTO, a compliant balloon (Hyperform, Covidien) was inflated at the level of possible occlusion while serial neurological examinations were performed along with angiography of the contralateral vertebral and carotid arteries to assess for collateral flow. The BTO lasted at least 20 minutes, provided the patient was tolerating this well. Heparin was administered with bolus dosing for BTO procedures (activated clotting time target, 200–250 seconds). Criteria for vertebral artery occlusion were: 1) significant tumor vascularity from the vertebral artery branches with risk of reflux of the embolic material into the vertebral artery despite selective catheterization of tumor feeder, 2) the presence of anastomoses from tumor feeders to the vertebral artery that could not be selectively occluded, 3) significant tumor involvement of the vertebral artery resulting in a high likelihood of vessel sacrifice during surgery, and 4) co-dominant vertebral arteries or a contralaterally dominant vertebral artery. Vertebral artery occlusion was performed only if there was robust collateral flow and a normal neurological examination during the BTO. All patients with post-vertebral artery occlusion were placed on a heparin drip for 12–24 hours after the procedure to prevent stump emboli.

Embolization was performed either under conscious sedation or general anesthesia, depending on the complexity of the procedure, the need for BTO, the patient’s ability to cooperate, and the level of pain when lying on the angiography table. The criteria for embolization included the presence of significant tumor vascularity, and the ability to achieve a stable microcatheter position without the risk of reflux into the aorta, vertebral, subclavian or carotid arteries. The presence of a spinal cord artery feeder (to the anterior or the posterior spinal artery) arising from the arterial feeder to the tumor feeder was an absolute contraindication for embolization. For embolizations via the vertebral or subclavian artery branches, a 6 French guide catheter was used. In the case of superior intercostal artery embolization, a 5 French catheter was typically adequate to serve as the guide catheter. The embolization techniques consisted of: superselective catheterization of the arterial feeders supplying the hypervascular tumor using a microcatheter followed by injection of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles (150–250 microns) (Figure 1) or Onyx liquid embolic directly into the tumor feeder. In cases with a dangerous anastomosis to the vertebrobasilar system, we considered occlusion of the anastomosis using detachable coils to prevent inadvertent embolization of the vertebrobasilar circulation (Figure 2). In cases of reflux into the vertebral artery, permanent (with detachable coils) occlusion of the vertebral artery was considered after BTO to prevent inadvertent embolization in the vertebrobasilar circulation (Figures 2 and 3). In cases in which superselective catheterization of the tumoral feeder was not feasible, we considered occlusion of a distal branch that did not supply the tumor in order to divert the embolic material to the tumor (“flow diversion”). Finally, vertebral artery occlusion was performed if there was significant tumor blush supplied by multiple short vertebral artery branches that were impossible to selectively catheterize; this was followed by infusion of the embolic material proximal to the tumor-feeding branches. The vertebral artery occlusion acted as a barrier to inadvertent embolization of arteries of the posterior fossa. Vertebral artery occlusion was followed by a heparin drip for 24–48 hours post-procedure to prevent stump emboli. Technical failure of embolization occurred when we were unable to achieve a microcatheter position that would allow embolization using the methodology described above. Intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring was never used.

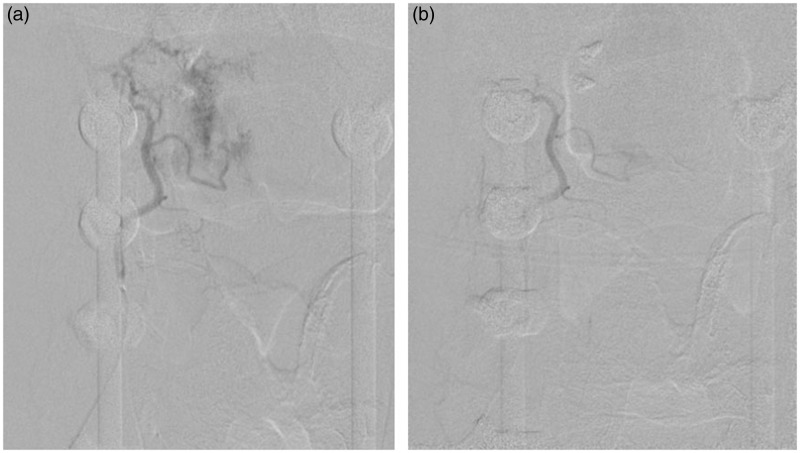

Figure 1.

A 64-year-old male with metastatic thyroid cancer status post-previous resection and fusion, now with recurrence at C2–C3 level, referred for preoperative embolization. (a) DSA of the right ascending cervical artery (Frontal view) demonstrates intense blush with arteriovenous shunting. (b) Post-embolization DSA of the right ascending cervical artery (Frontal view). The tumor was embolized with PVA particles. The tumor blush has been significantly reduced.

DSA: digital subtraction angiography; PVA: polyvinyl alcohol.

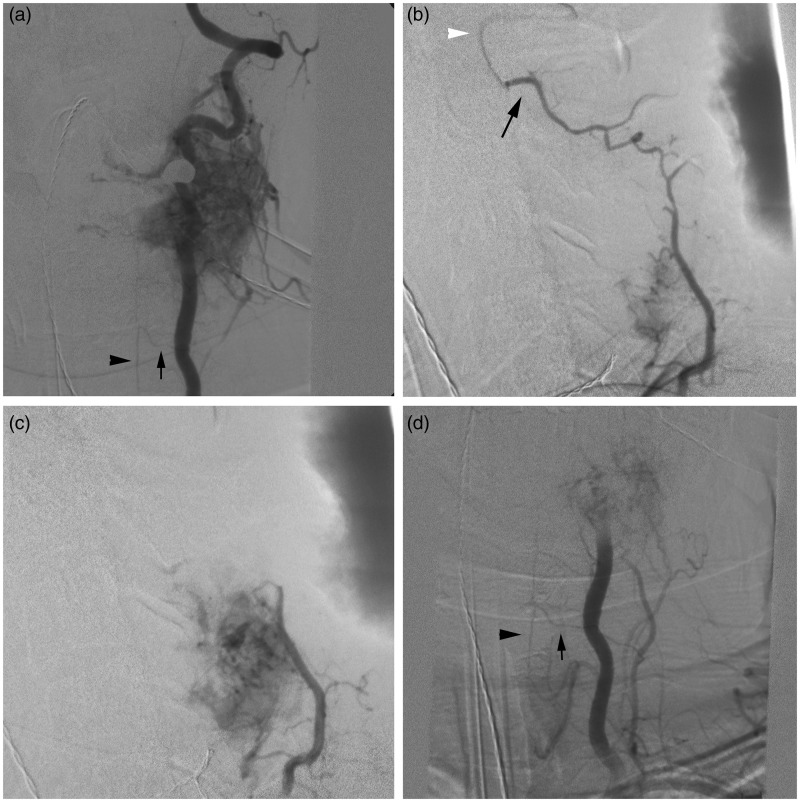

Figure 2.

(a) DSA of the left vertebral artery (Frontal view) demonstrates an intensely vascular RCC metastasis at C4–C5 with marked arteriovenous shunting. The artery of cervical enlargement (black arrow) is noted to arise from the vertebral artery with prominent filling of the anterior spinal artery (black arrowhead) visualized. (b) DSA of the left deep cervical artery (lateral view) demonstrates opacification of the hypervascular mass. An anastomosis (black arrow) between a distal branch of the left deep cervical artery and the left vertebral artery (white arrowhead) is also noted. (c) To prevent inadvertent cerebral embolization, a coil mass was deployed in the distal left deep cervical artery branch. Post-coil embolization DSA of the left deep cervical artery (lateral view) demonstrates marked tumor opacification but the anastomosis with the vertebral artery is no longer visualized. PVA particles were then safely injected into the left deep cervical artery tumor feeders. (d) Post-embolization DSA of the left vertebral artery (Frontal view) demonstrates occlusion of the vessel after deployment of coils and detachable balloons. PVA particles were delivered into small, tortuous vertebral artery tumor feeders from a proximal position in the vertebral artery. Particles were delivered distal to the origin of the artery of cervical enlargement (arrow) to avoid spinal cord ischemia. Filling of the anterior spinal artery (arrowhead) remains robust after embolization of tumor feeders.

DSA: digital subtraction angiography; RCC: renal cell carcinoma; PVA: polyvinyl alcohol.

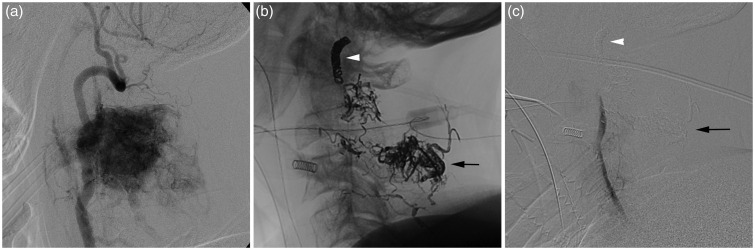

Figure 3.

(a) DSA of the left vertebral artery (lateral view) demonstrates an intensely vascular hemangiopericytoma at C2–C3 with marked arteriovenous shunting. The mass also receives vascular supply from the right vertebral artery, bilateral ascending cervical arteries, and left deep cervical artery (not shown). (b) Post-embolization unsubtracted image demonstrates the Onyx cast (black arrow) in the mass at C2–C3. The deployed coil mass (white arrowhead) is visualized at the junction of the V2 and V3 segments. (c) Post-embolization DSA of the left vertebral artery (lateral view) demonstrates occlusion of the left vertebral artery by the deployed coil mass (white arrowhead). There is considerably reduced tumor opacification after injection of Onyx (black arrow) into one vertebral artery branch and PVA particle embolization of remaining vertebral artery feeders from a proximal position in the vertebral artery.

DSA: digital subtraction angiography; PVA: polyvinyl alcohol.

Results

A total of 47 patients (49 cervical spinal tumors), consisting of 18 females (37%) and 31 males (63%), were included in this study. The mean age at presentation was 51 ± 14 years (range, 12–78 years). Of the 49 total tumors, 41 (83.7%) were identified as hypervascular (defined by having a tumor vascularity score from 1 to 3) on angiography. Embolization was attempted in 25 (60.1%) of the 41 hypervascular tumors. Notably, complete tumor embolization was achieved in 9/25 (36%), near-complete tumor embolization was achieved in 11/25 (44%), and partial tumor embolization was achieved in 5/25 (20%) of embolized tumors. For the remaining 16 cases of hypervascular tumors, embolization was not attempted (explanation below).

Tumor histology was confirmed from surgical specimens for 48 tumors. In one case surgery was deferred but the tumor was recurrent and we considered the same histological diagnosis as the original tumor. As these patients were scheduled for surgery, there was no biopsy prior to embolization and surgery. The most common tumor pathology in our series was RCC (N = 16; 32.7% of all tumors) followed by thyroid carcinoma (N = 7; 14.3% of all tumors). Mean tumor vascularity scores (MTVS) were calculated by averaging the individual vascularity scores of each tumor, according to histology subtype. The highest MTVS were reported for the giant cell tumor (MTVS = 3.0; N = 1), plasmacytoma (MTVS = 3.0; N = 1), hemangiopericytoma (MTVS = 2.7; N = 2), and RCC (MTVS = 2.1; N = 16) (Table 1). There were 93 angiographically visualized arterial tumor feeders supplying the 41 hypervascular tumors, and these feeders most commonly arose from the vertebral artery (43.0%) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Mean tumor vascularity scores (MTVS) among 49 cervical spinal tumors (in 47 patients) who underwent preoperative angiography at our institution (2002–2012).

| Low vascularity (MTVS < 1.0) |

Medium vascularity (MTVS, 1.0–1.9) |

High vascularity (MTVS ≥ 2.0) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean tumor vascularity score | Histology | Number of tumors (N = 8) | Mean tumor vascularity score | Histology | Number of tumors (N = 17) | Mean tumor vascularity score | Histology | Number of tumors (N = 24) |

| 0.5 | Chondrosarcoma | 2 | 1.6 | Thyroid carcinoma | 7 | 3.0 | Giant cell tumor | 1 |

| 0.5 | Leiomyosarcoma | 2 | 1.3 | Meningioma | 3 | 3.0 | Plasmacytoma | 1 |

| 0.0 | Aneurysmal bone cyst | 1 | 1.0 | Adrenal carcinoma | 1 | 2.7 | Hemangiopericytoma | 3 |

| 0.0 | Fibrous dysplasia | 1 | 1.0 | Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 2.1 | Renal cell carcinoma | 16 |

| 0.0 | Schwannoma | 1 | 1.0 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 | 2.0 | Chordoma | 1 |

| 0.0 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 | 1.0 | Laryngeal spindle cell carcinoma | 1 | 2.0 | Hemangioma | 1 |

| 1.0 | Lung carcinoma (mixed small-cell/ non-small-cell) | 1 | 2.0 | Synovial sarcoma | 1 | |||

| 1.0 | Neurofibroma | 1 | ||||||

| 1.0 | Osteochondroma | 1 | ||||||

Mean tumor vascularity scores (MTVS) were calculated by averaging the individual vascularity scores of each tumor. Individual tumor vascularity scores were calculated as the following: 0 = tumor blush (vascularity) equal to the normal adjacent vertebral body; 1 = tumor blush slightly more prominent than the normal vertebral body blush; 2 = considerable tumor blush without arteriovenous shunting; and 3 = intense tumor blush with arteriovenous shunting.

Table 2.

Parent artery origin of all cervical spine tumor feeders in 47 patients (49 tumors) who underwent preoperative angiography at our institution (2002–2012).

| Value (%, (N)) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeders, arranged by tumor cervical location |

|||||

| Parent artery | Total feeders (N = 93) | C1–C3 (N = 28) | C4–C5 (N = 18) | Below C5 (N = 37) | Tumors overlapping all cervical segments (N = 10) |

| Vertebral | 43.0 (40) | 60.7 (17) | 50.0 (9) | 27.0 (10) | 40 (4) |

| Thyrocervical trunk | 25.8 (24) | 14.3 (4) | 27.8 (5) | 35.1 (13) | 20 (2) |

| Costocervical trunk | 17.2 (16) | 10.7 (3) | 22.2 (4) | 21.6 (8) | 10 (1) |

| Occipital | 4.3 (4) | 14.3 (4) | – | – | – |

| Subclavian | 3.2 (3) | – | – | 5.4 (2) | 10 (1) |

| Superior intercostala | 3.2 (3) | – | – | 8.1 (3) | – |

| Inferior thyroid | 1.1 (1) | – | – | 2.7 (1) | – |

| Supreme intercostalb | 1.1 (1) | – | – | – | 10 (1) |

| Transverse cervical | 1.1 (1) | – | – | – | 10 (1) |

N: number of tumors. aOriginating from the aorta. bA branch of the costocervical trunk.

Tumor embolization was performed in 25 hypervascular tumors (25 patients; 40% females; age range, 25–78; mean age ± SD, 52 ± 14 years), resulting in complete, near-complete, and partial embolization in 36.0% (N = 9), 44.0% (N = 11), and 20.0% (N = 5) of embolized tumors, respectively (Table 3). We embolized 42 tumor feeders in 25 tumors. Embolization techniques consisted of a combination of PVA particles, detachable platinum coils, detachable balloons, and Onyx (Table 3). Onyx was used in two cases of hemangiopericytoma (Figure 3). No patients underwent repeat embolization of the same lesion.

Table 3.

Characteristics of 25 hypervascular cervical spine tumor embolization procedures (in 25 patients) performed at our institution (2002–2012).

| Variable | Percentage (N) |

|---|---|

| Embolization characteristics | |

| Embolized feeders | N = 42 |

| Thyrocervical trunk | 35.7% (15) |

| Costocervical trunk | 26.2% (11) |

| Vertebral artery | 19.0% (8) |

| Superior intercostal artery | 7.1% (3) |

| Occipital artery | 4.8% (2) |

| Inferior thyroid artery | 2.4% (1) |

| Subclavian artery | 2.4% (1) |

| Transverse cervical artery | 2.4% (1) |

| Embolization material used, by case | N = 25 |

| PVA particles only | 72.0% (18) |

| PVA, coilsa, and detachable balloons | 12.0% (3) |

| PVA, coils, and Onyx | 4.0% (1) |

| PVA and coils | 4.0% (1) |

| Coils and Onyx | 4.0% (1) |

| Coils only | 4.0% (1) |

| Post-embolization results (vascularity scores) | N = 25 |

| Complete (grade 0) | 36.0% (9) |

| Near-complete (grade 1) | 44.0% (11) |

| Partial (grades 2 or 3) | 20.0% (5) |

All coils were platinum coils. N: number; PVA: polyvinyl alcohol.

Regarding vertebral artery tumor feeders, direct superselective catheterization and embolization was performed in 12% of the embolization procedures; proximal PVA particle embolization after permanent vertebral artery occlusion was performed in 12% of the embolization procedures; and vertebral artery occlusion alone was performed in 8% of the embolization procedures.

Vertebral artery occlusion was performed in 20% (N = 5) of the embolization procedures (two cases with coils alone and three cases with detachable balloons (while they were still available in the United States) and coils) (Figures 2 and 3). Other flow control techniques included the placement of coils in the ascending and deep cervical artery branches to prevent flow into a distal anastomosis with the vertebral artery during PVA particle embolization from a more proximal branch (two cases) (Figure 2). In two additional cases, coils were deployed into the proximal tumor feeder artery to supplement tumor embolization after delivery of PVA particles more distally.

Sixteen hypervascular tumors (grade 1, N = 10; grade 2, N = 4; grade 3, N = 2) were not embolized. In eight of these 16 tumors, both the hypervascularity was minimal and it was decided that the risks associated with embolization and navigation of cervical arteries with a microcatheter outweighed the potential benefits. In two cases, tumor feeders were identified as branching off a dominant vertebral artery but were too small and tortuous to be safely catheterized to the point of no reflux; in these cases, there was an increased risk of vertebrobasilar stroke and the vertebrobasilar arterial anatomy did not favor vertebral artery occlusion. In three cases, stable superselective catheterization of a small vertebral artery tumor feeder was attempted but could not be achieved without reflux into the vertebral artery (i.e. technical failure). In two cases, embolization was not performed because an anterior spinal artery was visualized as arising from the main tumor feeder branch, which is an absolute contraindication for embolization.18 Lastly, in one case of a 61-year-old male with a recurrent C2 thyroid carcinoma metastasis who had undergone prior preoperative embolization and surgical resection, repeat angiogram for a possible surgical re-resection demonstrated intense tumor vascularity supplied by multiple, small, tortuous tumor feeders from the vertebral arteries bilaterally. Even with occlusion of one of the vertebral arteries, embolization would be partial at best; subsequent surgery would have been complicated by extensive intraoperative blood loss with a high risk of morbidity and mortality. After consultation with the neurosurgeon, the plan for aggressive surgical management was aborted and preoperative embolization was cancelled.

Estimated blood loss (EBL) was reported for 48 tumors that underwent surgery. The mean EBL for grade 0 tumors (N = 8, (none underwent embolization)) was 1057 ml. The mean EBL for grade 1 tumors that underwent preoperative embolization (N = 5) was 635 ml; the mean EBL for grade 1 tumors that did not undergo preoperative embolization (N = 10) was 625 ml. The mean EBL for combined grades 2 and 3 tumors that underwent preoperative embolization (N = 20) was 722 ml; the mean EBL for combined grades 2 and 3 tumors that did not undergo preoperative embolization (N = 5) was 1717 ml. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean EBL between embolized and non-embolized tumors with low (grade 1) hypervascularity (p = 0.486). There was, however, a significant difference (p = 0.0147) in the mean EBL when comparing embolized and non-embolized tumors of moderate or severe hypervascularity (grades 2 and 3).

The minor complication rate was 6%, which included one allergic anaphylactic response during angiography (which was successfully managed with corticosteroids and antihistamines), one case of neck pain, and one small post-procedure groin hematoma (that did not require intervention). The major complication rate was 0%. No patient developed new post-procedure neurologic deficits or strokes and there was no procedure-related mortality.

Discussion

Tumor embolization has become an important component in the multidisciplinary management of hypervascular tumors along the spinal axis. However, the existing literature for preoperative embolization dedicated to cervical spinal tumors is limited. Further evaluation of embolization techniques for cervical spinal tumors is important because the cervical spine vascular anatomy and blood supply to the tumors is more complex than that of thoracic/lumbar spinal tumors. Vascular supply to cervical spinal tumors may arise from branches of the vertebral, external carotid, or subclavian arteries. The tumor feeding branches may have a common origin with the radiculomedullary arteries that supply the spinal cord arteries or contain distal anastomoses with the vertebral artery; embolization of these arteries may lead to inadvertent embolization of the brain or spinal cord. Additionally, tumor feeders arising from the vertebral artery are often narrow, short, and tortuous, and are therefore difficult to selectively catheterize without significant risk of reflux of the embolic material. Thus, embolization of cervical spinal tumors carries more potential risk than that of thoracic/lumbar spinal tumors.7,20

Safety is paramount when dealing with embolization of cervical spinal tumors, as even a small vertebrobasilar stroke can be devastating. We present our methodology and results for embolization of hypervascular cervical spinal tumors in this series. We were able to effectively embolize the majority of tumors with significant hypervascularity (grades 2 and 3) without any neurological complications. In most cases, superselective catheterization of the tumor feeders was achieved; this allowed for safe embolization while avoiding occlusion of the vertebral artery. PVA was the most commonly used embolic material to penetrate the tumor vascularity. Onyx was chosen for embolization of two large hemangiopericytomas because of its ability to achieve greater penetration of the tumor vasculature and produce a more durable occlusion.16

We report EBL data with the caveat that there are many other variables that can affect intraoperative blood loss, including surgical technique, location and size of tumor, tumor histology, adjunctive intraoperative tools, and means of intraoperative blood loss assessment. We need to point out that there was no randomization between embolization or not, and that the decision to defer embolization was based on the perceived risk/benefit ratio of the procedure. In addition, we present a small cohort from a single institution, which must be extrapolated with caution and a healthy degree of skepticism. With these limitations in mind, our data suggest that for cervical spinal tumors of moderate and severe vascularity (i.e. grades 2 and 3), preoperative embolization is associated with significantly decreased blood loss during surgery. This benefit was not evident in tumors with mildly increased vascularity. Vetter et al. published the largest case series of cervical spinal tumor embolizations, which included 38 patients with mixed pathologies.8 Thirty-six embolization procedures were performed, of which 27 were complete and nine were partial. In 64% of embolization cases, a vertebral artery was occluded. In one case, the distal end of the coil mass for a vertebral artery occlusion reached the posterior inferior cerebellar artery origin; this resulted in dizziness that subsequently resolved. In another case in which the vertebral artery was occluded, the patient woke from the embolization procedure with no deficits; however, the patient suffered a pontine infarct after surgical resection, performed one day after embolization. Notably, the authors did not describe the routine use of anticoagulation post-vertebral artery occlusion; this may explain the possible thromboembolic complications that occurred in the above-mentioned two cases. Another large retrospective review of spinal tumor embolizations at a single institution described 20 patients with cervical spinal tumors.1 Specific technical details were not discussed, but the authors did report a post-procedural cerebellar infarct after embolization of a C6–T1 RCC metastasis. There have been three additional preoperative spinal tumor embolization studies involving a small number of patients; in these studies the authors either reported a small number of asymptomatic infarcts or there was no mention of complications.6,23 A survey of the existing literature regarding cervical spinal tumor embolization suggests there may be an increased risk of neurologic injury following embolization. However, there are limited descriptions of the technical nuances of these procedures, which is an important point for minimizing the risks associated with cervical spinal tumor embolization.

Our approach to cervical spinal tumor embolization involves careful review of angiographic images prior to and during embolization to identify radiculomedullary branches, vertebral artery anastomoses, and reflux into the carotid or vertebral arteries, all potential sources of spinal or cerebral stroke. The use of general anesthesia was not mandatory in our series. General anesthesia has a clear advantage of improved visualization of small spinal cord arteries. Cases that are performed under conscious sedation (when there is a need for BTO for example) should be converted to general anesthesia if there is any question of presence of a spinal cord artery; this allows for the use of paralytics and suspension of respirations to optimize angiographic image quality. Following a careful angiographic review, embolization of a tumor feeder was not undertaken because of the proximity of a radiculomedullary artery in 4.7% of our cases. In two cases, either the ascending cervical artery or deep cervical artery provided important tumor supply but were found to have distal anastomoses with the vertebral artery. Flow control was used during embolization by occluding the distal branch supplying the anastomosis and thereby preventing inadvertent flow of PVA particles to the intracranial circulation; this allowed for safe and effective tumor embolization.

In our series, the most common tumor feeders in the cervical spine were small vertebral artery branches, which was also observed by Vetter et al.8 These branches are usually small and tortuous, which often precludes superselective catheterization or catheterization to a point where there is no reflux into the vertebral artery. Not surprisingly, these small vertebral artery feeders were the most common technical reason for the inability to embolize a tumor feeder in our series. This is in contrast to embolization of thoracic/lumbar lesions for which the presence of a radiculomedullary artery is the most common reason for not occluding a tumor feeder.2 In a subset of our cases, (super)selective catheterization of the feeders was achieved; in a minority of cases, however, we used permanent vertebral artery occlusion to allow for PVA particle embolization from a more proximal position in the vertebral artery (Figures 1 and 2). Permanent vertebral artery occlusion was performed only when our criteria, as described in our Methods section, were met. Compared to the series by Vetter et al.8, we performed vertebral artery occlusion much less frequently, as we used it as a “last resort” choice. In other words, we sacrificed a vertebral artery only in cases in which a significantly hypervascular tumor would not be effectively or safely embolized otherwise.

Thromboembolism from a new vertebral artery occlusion may be the cause of post-procedure infarcts that have been observed in cervical spinal tumor embolization patients.8 We typically use BTO as an adjunct to assess safety of vertebral artery occlusion. We also use a short course of anticoagulation after vertebral artery occlusion to prevent stump emboli, at least in the short term. Even though there is no evidence to suggest that this approach should be standard of care, we feel that it maximizes the safety of vertebral occlusion.

As it is important to avoid inadvertent embolization and stroke, complete embolization of the tumor is often not feasible. As shown in our series, many of these tumors have multiple feeders from the vertebral artery, and complete tumor embolization would require either a high-risk embolization procedure or occlusion of the vertebral artery. Our team’s approach is to perform vertebral artery occlusion as infrequently as possible, even at the cost of partial tumor embolization. We believe that this approach is associated with fewer risks to the patient both in the short and long run.

Twenty-five embolization procedures were performed without any neurological complications. One patient with a large RCC metastasis did experience increased cervical pain after the embolization. The increased pain was presumably secondary to tumor necrosis and edema after embolization, which has been observed elsewhere,24,25 but was successfully managed with analgesics and increased steroids.

Conclusions

Preoperative embolization of cervical spinal tumors can be performed safely and effectively in centers with significant experience and a standardized approach. Knowledge of vascular anatomy, anticipation of possible adverse events, and judicious balance of risk versus benefit ratio are essential. In our series, the embolization benefit was evident for tumors of moderate and severe hypervascularity.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Wilson MA, Cooke DL, Ghodke B, et al. Retrospective analysis of preoperative embolization of spinal tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 656–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prabhu VC, Bilsky MH, Jambhekar K, et al. Results of preoperative embolization for metastatic spinal neoplasms. J Neurosurg 2003; 98: 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olerud C, Jónsson H, Jr, Löfberg AM, et al. Embolization of spinal metastases reduces peroperative blood loss. 21 patients operated on for renal cell carcinoma. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64: 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkefeld J, Scale D, Kirchner J, et al. Hypervascular spinal tumors: Influence of the embolization technique on perioperative hemorrhage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 757–763. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manke C, Bretschneider T, Lenhart M, et al. Spinal metastases from renal cell carcinoma: Effect of preoperative particle embolization on intraoperative blood loss. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22: 997–1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzman R, Dubach-Schwizer S, Heini P, et al. Preoperative transarterial embolization of vertebral metastases. Eur Spine J 2005; 14: 263–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heran MK. Preoperative embolization of spinal metastatic disease: Rationale and technical considerations. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2011; 15: 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vetter SC, Strecker EP, Ackermann LW, et al. Preoperative embolization of cervical spine tumors. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1997; 20: 343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirakuni T, Tamaki N, Matsumoto S, et al. Giant cell tumor in cervical spine. Surg Neurol 1985; 23: 148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akagi S, Saito T, Ogawa R. Maffucci’s syndrome involving hemangioma in the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995; 20: 1510–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro S, Scott J, Kaufman K. Metastatic cardiac angiosarcoma of the cervical spine. Case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999; 24: 1156–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohtakara K, Kuga Y, Murao K, et al. Preoperative embolization of upper cervical cord hemangioblastoma concomitant with venous congestion—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2000; 40: 589–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brennan JW, Midha R, Ang LC, et al. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the spine presenting as cervical myelopathy: Case report. Neurosurgery 2001; 48: 1166–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez-Ben R, Siegal GP, Hadley MN. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the cervical spine: Case report. Neurosurgery 2002; 50: 409–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaguchi S, Hida K, Nakamura N, et al. Multiple vertebral metastases from malignant cardiac pheochromocytoma—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2003; 43: 352–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trübenbach J, Nägele T, Bauer T, et al. Preoperative embolization of cervical spine osteoblastomas: Report of three cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 1910–1912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mindea SA, Eddleman CS, Hage ZA, et al. Endovascular embolization of a recurrent cervical giant cell neoplasm using N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate. J Clin Neurosci 2009; 16: 452–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santillan A, Zink W, Lavi E, et al. Endovascular embolization of cervical hemangiopericytoma with Onyx-18: Case report and review of the literature. J Neurointerv Surg 2011; 3: 304–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novais EN, Rose PS, Yaszemski MJ, et al. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the cervical spine in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93: 1534–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozkan E, Gupta S. Embolization of spinal tumors: Vascular anatomy, indications, and technique. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2011; 14: 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bilsky MH, Boakye M, Collignon F, et al. Operative management of metastatic and malignant primary subaxial cervical tumors. J Neurosurg Spine 2005; 2: 256–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher CG, DiPaola CP, Ryken TC, et al. A novel classification system for spinal instability in neoplastic disease: An evidence-based approach and expert consensus from the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; 35: E1221–E1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi HB, Suh DC, Lee HK, et al. Preoperative transarterial embolization of spinal tumor: Embolization techniques and results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 2009–2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soo CS, Wallace S, Chuang VP, et al. Lumbar artery embolization in cancer patients. Radiology 1982; 145: 655–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith TP, Gray L, Weinstein JN, et al. Preoperative transarterial embolization of spinal column neoplasms. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1995; 6: 863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]