Abstract

BACKGROUND

ARRY-520 selectively inhibits the mitotic kinesin spindle protein (KSP), which leads to abnormal monopolar spindle formation and apoptosis.

METHODS

A Phase 1 trial was conducted to establish the safety and the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of ARRY-520 given as a 1-hour infusion in either a single dose or on a Days 1, 3 and 5 divided-dose schedule per cycle in patients with advanced or refractory myeloid leukemias. Additional objectives were to characterize pharmacokinetics (PK), assess preliminary clinical activity and explore biomarkers of KSP inhibition with ARRY-520. A total of 36 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (n=34) or myelodysplastic syndromes (n=2) with a median age of 66 (range 21–88 years) were enrolled: 15 in the single-dose schedule (dose levels: 2.5, 3.75, 4.5 and 5.6 mg/m2) and 21 in the divided-dose schedule (dose levels: 0.8, 1.2, 1.5 and 1.8 mg/m2/day).

RESULTS

The MTD was 4.5 mg/m2 total dose per cycle for both dose schedules. Dose-limiting toxicities (DLT) included mucositis, exfoliative rash, hand-foot syndrome and hyperbilirubinemia. Grades 3 or 4 reversible drug-related myelosuppression were observed in 33/36 patients. Plasma PK analyses revealed low clearance of ARRY-520 (~3 L/hr), a volume of distribution of ~450 L and a median terminal t1/2 of > 90 hours. Monopolar spindles were observed in blood mononuclear cells using DAPI nucleic acid stain and anti-tubulin antibodies.

CONCLUSION

Based on the relative lack of clinical activity, further development of ARRY-520 as an antileukemic agent was halted. (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00637052).

Keywords: KSP inhibitor, ARRY-520, Phase 1, MTD, AML, MDS, relapsed

Introduction

Treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has been based for the past 30 years on a combination of an anthracycline and cytosine arabinoside. This approach is effective, and up to 70% of patients achieve remission,1–6 but disease recurrence is common (80%) without consolidation with an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)7–9 The majority of relapses occur in the first year after diagnosis,10–14 which is associated with lower chances of achieving and sustaining a second complete remission (CR), a pre-requisite for a curative allogeneic transplant15–19 Therefore, well-tolerated and effective new drugs in AML are desperately needed.

Anti-mitotics are effective anti-cancer agents, with mechanisms of action that involve inhibition of tubulin polymerization (vinca alkaloids) or stabilization of microtubule polymers (taxanes). However, their lack of specificity results in dose-limiting neurotoxicity from disruption of microtubule dynamics in synaptic vesicles and Golgi apparatus. Mitotic kinesins are a family of motor proteins involved in all phases of mitosis, including chromosome and mitotic spindle dynamics and microtubule depolymerization.20 These proteins convert the energy of ATP hydrolysis to mechanical force resulting in movement of microtubules.21 Kinesin spindle protein (KSP; also known as hsEg5) is one member of the mitotic kinesins involved in the early stages of mitosis responsible for centrosome separation, a pre-requisite for formation and maintenance of the bipolar spindle.22 Microinjection of KSP antibodies into cells resulted in monopolar spindles, mitotic arrest and apoptosis.23,24 Similar cellular effects and anti-cancer activity have been observed with several structurally distinct small-molecule KSP inhibitors,20,25–27 both in vitro and in mouse xenograft models.25,28–30 Targeting KSP is therefore an attractive novel approach in cancer, given that KSP inhibitors may theoretically permit dose escalation to overcome drug resistance without the concern for neurotoxicity.

ARRY-520 is a potent, highly selective inhibitor of KSP that induces mitotic arrest and tumor cell death at sub-nanomolar concentrations. ARRY-520 has demonstrated anti-cancer efficacy in mouse subcutaneous solid-tumor xenograft models (HT-29, HCT-116, A2780, K562, and HCT15).31 Therefore, a Phase 1 trial was conducted to identify the optimal dose schedule and determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of ARRY-520 in patients with relapsed and refractory AML and advanced myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

Material and Methods

Study Design

The study was an open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation trial aiming to assess safety, determine the MTD, preliminary efficacy, pharmacokinetics and to identify markers of pharmacodynamic activity of ARRY-520. Two dose schedules were sequentially explored: a single-dose schedule where ARRY-520 was given intravenously over one hour on Day 1 (Schedule 1), and a multi-dose schedule where ARRY-520 was given intravenously over one hour daily on Days 1, 3 and 5 (Schedule 2). The dose of ARRY-520 was escalated after a minimum of three evaluable patients were entered at each dose level. Initially, doses of ARRY-520 were increased by 50% until study drug-related Grade 2 nonhematological adverse events (AE) occurred; then, the escalation schema was changed to an increase of 30%. AEs were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE), Version 3.0. Dose escalation to a new dose level occurred in the absence of a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT). A DLT was defined as any Grade 2 non-hematological AE occurring in the induction cycle, and deemed related to ARRY-520. If a DLT was observed in 1/3 evaluable patients, three additional patients were recruited at the same dose level. Dose escalation continued unless a DLT was observed in > 1/6 evaluable patients; otherwise, the dose was considered a non-tolerated dose and dose escalation was stopped. When a non-tolerated dose was identified, three additional evaluable patients were recruited at the lower dose to confirm the MTD. Patients received subsequent cycles in the absence of toxicity or progressive disease. Intra-individual dose escalation was not permitted.

Safety was assessed on a continuous basis. Additionally, patients were monitored with complete blood counts three times per week, blood chemistries twice weekly, and coagulation parameters weekly. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy was done between Days 10–14 of the first course, and repeated at hematological recovery or between Days 28–31. Electrocardiograms were done prior to start of infusion, within 15–30 minutes and 24 hours after the end of infusion. A serious adverse event (SAE) was defined as an AE that was life-threatening, required inpatient hospitalization, or resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly/birth defect, or death.

Efficacy for patients with AML was assessed by determining the incidence of complete and partial remissions during induction therapy and subsequent courses. Response for patients with advanced MDS was evaluated according to the modified International Working Group (IWG) criteria.32

Pharmacokinetics. (PK)

Blood samples were collected during Cycle 1 for determination of plasma concentrations of ARRY-520 on Days 1 (1, 2 and 8 hours), 2, 3, 5 and 8 on Schedule 1; and on Days 1 (1, 2 and 8 hours), 2, 3 (pre-dose, 1 and 4 hours), 5 (pre-dose, 1, 2 and 8 hours), 8, 11 and 15 on Schedule 2. Bioanalysis was performed using a validated LC-MS/MS method with a lower limit of detection of 1 ng/mL. PK parameters were determined from the individual plasma concentration-time curves of ARRY-520 by non-compartmental analysis.

Pharmacodynamics. (PD)

Blood samples were collected for PD analyses during Cycle 1 and Cycle 2 (if applicable). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified from Cycle 1, Day 5 samples using FICOL separation. PBMCs were gently centrifuged at 500 RPM for 5 minutes onto poly-lysine treated cover slips, then fixed in PHEMO buffer (68 mM PIPES, 25 mM HEPES, pH 6.9, 15 mM EGTA, 3 mM MgCl2, 10% [vol/vol] DMSO) for 10 minutes. Cells were washed in PBS, then blocked in 10% normal goat serum and incubated with mouse antiacetylated alpha-tubulin (Sigma #T6793 1:1000) diluted into 5% normal goat serum for 16 hours at 4°C. Cells were washed in PBS, then incubated with a secondary antimouse Alexa 488-conjugated antibody (Invitrogen; 1:500) for 1 hour, and washed in PBS. Cells were then incubated with rat anti-tubulin (Millipore MAB1864) for 1 hour at room temperature, washed in PBS, then incubated with Alexa 565 anti-rat antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were washed again in PBS, incubated with 350 nM DAPI, then mounted onto slides. Confocal z-sections were acquired using a Zeiss LSM510 META microscope.33

Patients

Patients ≥ 17 years with relapsed or refractory AML or high-grade myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, including RAEB, RAEB-t and CMML), an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 – 2, and adequate hepatic and renal function were eligible for enrollment in the absence of central nervous system involvement by disease. Patients with newly diagnosed AML who were not eligible for, or refused, standard-of-care treatment were also eligible. All prior anti-leukemic therapy had to be discontinued ≥ 2 weeks prior to study entry. Concurrent use of hydroxyurea was allowed during the first 14 days of study to control WBC counts. The study was approved by the MD Anderson Cancer Center and Emory University ethics committees and all patients gave written informed consent.

Results

Patients

Between March 2008 and April 2010, 36 patients enrolled in this trial: 15 on Schedule 1 and 21 on Schedule 2. All patients received at least 1 cycle of ARRY-520.

Median age of the 15 patients treated according to Schedule 1 was 69 (range, 44–88); 8 were male and 7 were female. ECOG PS was 0 in 2, 1 in 7 and 2 in 6 (Table 1). All patients had AML and were diagnosed an average of 26 months (range, 6 – 108) prior to enrollment. The median number of prior chemotherapy regimens was 4 (range, 1–7). Two patients had relapsed AML after allogeneic HSCT. Median number of cycles of ARRY-520 administered was 1 (range, 1–4).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Schedule 1 (n=15) |

Schedule 2 (n=21) |

Total (n=36) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range, years) | 69 (44–88) | 63 (21–83) | 66 (21–88) |

| Gender: F/M | 7/8 | 7/14 | 14/22 |

| Race, n(%) | |||

| Black | 1 (7) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| Caucasian | 14 (93) | 19 (90) | 33 (92) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (3) |

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0 | 2 (13) | 3 (14) | 5 (14) |

| 1 | 7 (47) | 11 (52) | 18 (50) |

| 2 | 6 (40) | 7 (33) | 13 (36) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| MDS | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 2 (6) |

| AML | 15 (100) | 19 (90) | 34 (94) |

Median age of the 21 patients who received ARRY-520 according to Schedule 2 was 63 years (range, 21–83 years); 14 were male and 7 were female. ECOG PS was 0 in 3, 1 in 11 and 2 in 7 (Table 1). Nineteen patients had AML, 2 had MDS the median number of prior chemotherapy regimens was 3 (range, 1 – 5). Median time from diagnosis to start of ARRY-520 was 12 months (range, 0 – 45). Three patients had prior allogeneic HSCT. Median number of cycles of ARRY-520 administered was 1 (range, 1 – 4).

The starting dose for Schedule 1 was 2.5 mg/m2 administered on Day 1 based on DLTs observed in the Phase 1 study with this schedule of administration in patients with solid tumors (Study ARRAY-520–101). The starting dose for Schedule 2 was 0.8 mg/m2/day (2.4 mg/m2 total dose).

Safety Profile

All 36 patients were evaluable for safety analysis. All patients experienced at least one AE while on study; 27 patients (75%) experienced AEs that were related to study drug. Table 2 summarizes nonhematological AEs that were observed in more than 10% of patients in both schedules. Twenty six patients (72%) had an SAE (10 in Schedule 1 and 16 in Schedule 2). Ten patients (28%) had one or more SAEs considered related to study drug: mucositis (n=6, 17%), neutropenic fever (n=3, 8%), exfoliative rash (n=1, 3%), palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (n=2, 6%), and hyperbilirubinemia (n=1, 3%), bacteremia (n=1, 3%), pancytopenia (n=1, 3%), diarrhea (n=1, 3%), and stomatitis (n=1, 3%). Adverse events led to discontinuation in 3 patients (8%). Hematological toxicities were common and included Grades 3–4 anemia (n=20), Grades 3–4 leukopenia (n=21, present at baseline in n=6), Grade 4 neutropenia (n=26, present at baseline in n=21), and Grade 4 thrombocytopenia (n=33).

Table 2.

Non-hematological Adverse Events observed in > 10% of patients.

| Schedule 1 (N=15) | Schedule 2 (N=21) | Total (N=36) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-hematological AE | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| Total Patients With Any AE | 15 | (100) | 21 | (100) | 36 | (100) |

| Diarrhea | 4 | (27) | 11 | (52) | 15 | (42) |

| Mucosal inflammation | 6 | (40) | 9 | (43) | 15 | (42) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 6 | (40) | 7 | (33) | 13 | (36) |

| Nausea | 1 | (7) | 11 | (52) | 12 | (33) |

| Hypokalaemia | 4 | (27) | 5 | (24) | 9 | (25) |

| Rash | 3 | (20) | 4 | (19) | 7 | (19) |

| Constipation | 0 | (0) | 7 | (33) | 7 | (19) |

| Vomiting | 2 | (13) | 5 | (24) | 7 | (19) |

| Dyspnea | 2 | (13) | 4 | (19) | 6 | (17) |

| Cough | 2 | (13) | 3 | (14) | 5 | (14) |

| Headache | 2 | (13) | 3 | (14) | 5 | (14) |

| Peripheral edema | 3 | (20) | 2 | (10) | 5 | (14) |

| Pneumonia | 1 | (7) | 4 | (19) | 5 | (14) |

| Pyrexia | 2 | (13) | 3 | (14) | 5 | (14) |

| Anorexia | 0 | (0) | 4 | (19) | 4 | (11) |

| Asthenia | 0 | (0) | 4 | (19) | 4 | (11) |

| Cellulitis | 2 | (13) | 2 | (10) | 4 | (11) |

| Dizziness | 0 | (0) | 4 | (19) | 4 | (11) |

| Fatigue | 1 | (7) | 3 | (14) | 4 | (11) |

| Hyperphosphatemia | 4 | (27) | 0 | (0) | 4 | (11) |

| Hypomagnesaemia | 2 | (13) | 2 | (10) | 4 | (11) |

| Hypotension | 4 | (27) | 0 | (0) | 4 | (11) |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia syndrome | 2 | (13) | 2 | (10) | 4 | (11) |

| Pleural effusion | 1 | (7) | 3 | (14) | 4 | (11) |

When ARRY-520 was administered according to Schedule 1, no DLTs were observed at the 2.5, 3.75 or 4.5 mg/m2 doses, but 2 patients experienced Grade 3 mucositis at the 5.6 mg/m2 dose; therefore, the 4.5 mg/m2 dose was established as the MTD. In Schedule 2, no DLTs were observed at 0.8 mg/m2/day (2.4 mg/m2 total dose/cycle). Grade 3 mucositis was observed in 1 patient at 1.2 mg/m2/day (3.6 mg/m2 total dose/cycle) and in 1 patient at 1.5 mg/m2/day (4.5 mg/m2 total dose/cycle) (Table 2). DLTs were observed in 2 patients at 1.8 mg/m2/day (5.4 mg/m2 total dose/cycle), and included Grade 3 mucositis (n=1), hyperbilirubinemia (n=1), exfoliative rash (n=1), and hand-foot syndrome (n=1). The MTD was therefore also established to be 1.5 mg/m2/day (4.5 mg/m2 total dose) in Schedule 2. No Grade 3–4 QTc prolongation was observed, although; asymptomatic Grades 1 and 2 QTc prolongations were noted in 8 (22%) and 1 (3%) patients, respectively. No other clinically significant ECG changes were observed. Neurotoxicity was not observed at any dose up to the MTD.

Efficacy and outcomes

Of 34 patients for whom efficacy data were available, 1 (3%) achieved a partial response, 10 (28%) had stable disease, and 23 (64%) experienced disease progression. Thirty-three patients received subsequent therapies after discontinuation of this Phase 1 trial, and 6 (17%) died within 30 days following discontinuation of ARRY-520. At last follow-up, 32 patients had died. Causes of death included progressive disease (n=14), infection (n=7), and central nervous system bleed (n=1). Cause of death was not provided for 10 patients.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

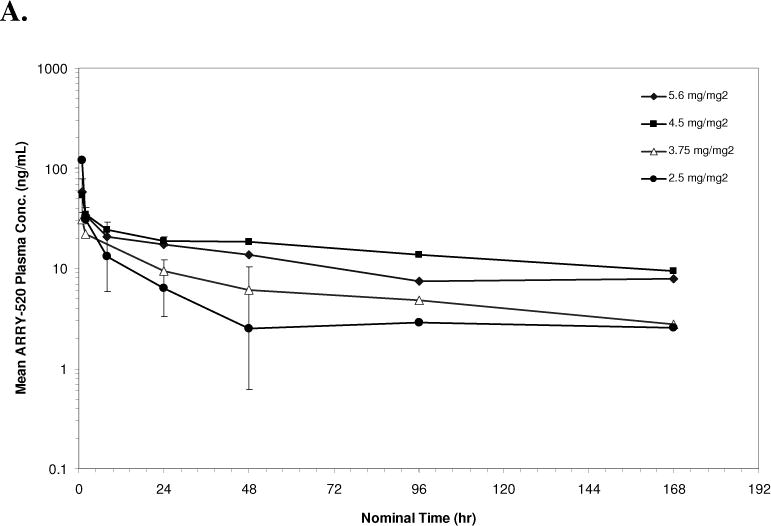

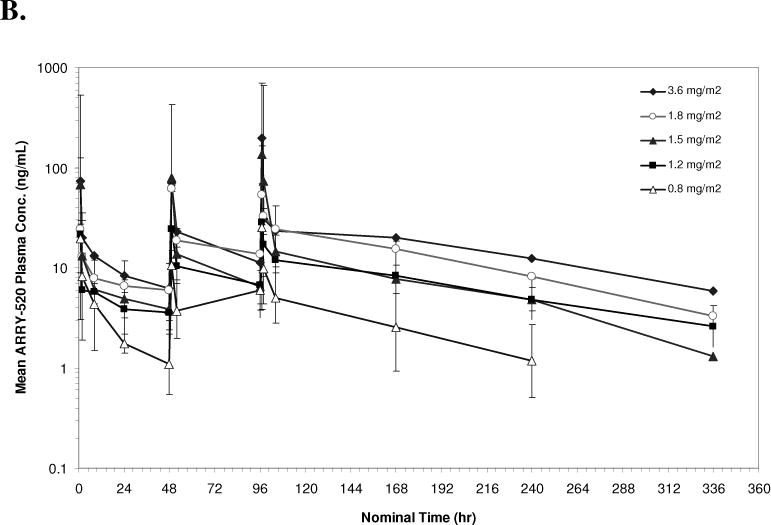

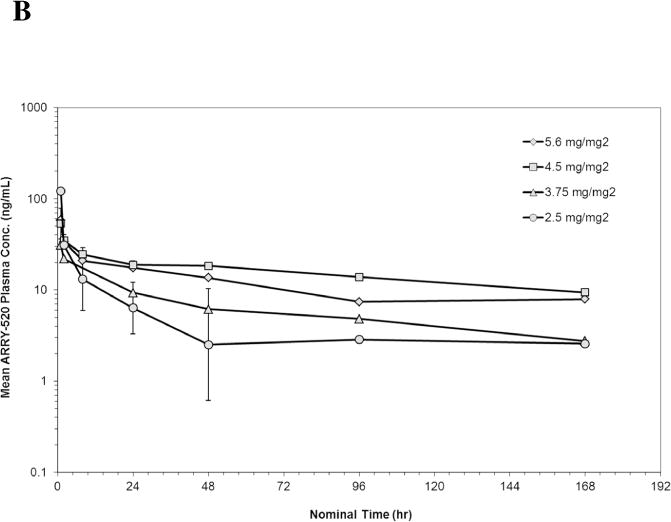

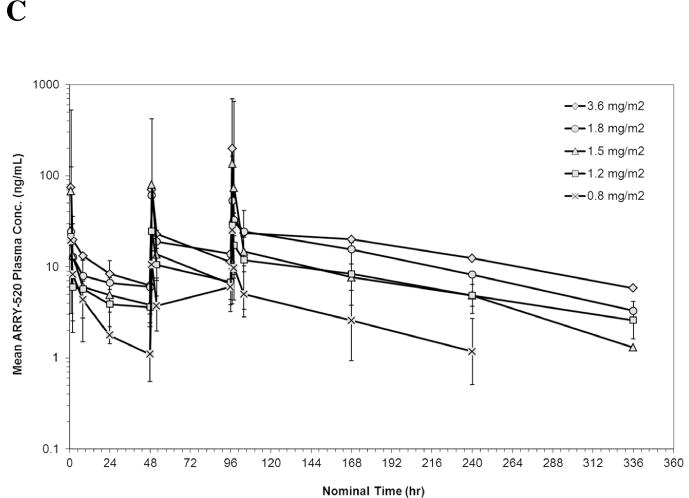

PK data were available from 10 patients in Schedule 1 and 18 patients in Schedule 2. The geometric mean plasma concentrations of ARRY-520 versus nominal sample collection time for Cycle 1 are shown in Figures 1A (Schedule 1) and 1B (Schedule 2). Summaries of PK parameters for Cycle 1 in both schedules are shown in Table 3. Following single doses of ARRY-520 (Schedule 1), geometric mean area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUCinf) values ranged from 1480 hr*ng/mL (3.75 mg/m2) to 3000 hr*ng/mL (4.5 mg/m2) while maximum observed plasma concentrations (Cmax) ranged from 31.1 ng/mL to 132 ng/mL. The geometric mean clearance (CL) across all patients was low, 3.36 L/hr (range: 2.69 to 6.77 L/hr). The geometric mean CL for Cycle 2 (all patients, N=4) was equivalent (3.02 L/hr) to Cycle 1, suggesting linear PK with repeat dosing. The coefficient of variation (CV) for CL was 50.7% (Cycle 1) and 77.1% (Cycle 2), indicating moderately high inter-patient variability in exposure. Similar CVs were observed when comparing Cycle 1 to Cycle 2 AUC values (intra-patient variability). Dose proportionality was difficult to assess given the narrow dose range and variability in exposure. The mean volume of distribution (Vss) was 446 L (55.2% CV) suggesting significant peripheral distribution. Consistent with the large volume and low clearance, the median terminal half-life (t1/2) was 98.6 hours. Similar values were observed for each cohort, indicating that terminal elimination of ARRY-520 was not dose-dependent over the dose range studied. Because of the long t1/2, plasma concentrations of ARRY-520 following a single infusion were maintained above 2 ng/mL for greater than 7 days postinitiation of infusion for all cohorts. The median of the mean residence time (MRT) for ARRY-520 was 127 hours (5.3 days). Following IV dosing on Days 1, 3 and 5 (Schedule 2), similar distribution and elimination phases were observed when compared to Schedule 1 concentration-time profiles for ARRY-520. Exposure tended to increase with each day of dosing. The overall ratio of AUC0–24 values on Day 5 compared to Day 1 was 2.23 (range across cohorts: 1.54 to 2.92), indicating a trend towards accumulation with repeated dosing at 48-hour intervals. Following the third infusion of ARRY-520 in Schedule 2, the median t1/2 (92.5 hours) and median MRT (130 hours) were equivalent to values observed following a single infusion in Schedule 1. As a result of the repeat dosing, accumulation and terminal phase, geometric mean plasma concentrations of ARRY-520 were maintained above 2 ng/mL for more than 14 days for all cohorts.

Figure 1.

Geometric Mean Plasma Concentration of ARRY-520 (with 1 Standard Deviation) for Schedule 1 (Panel A) and Schedule 2 (Panel B)

Table 3.

Cycle 1 Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Schedule 1 and Schedule 2.

| Schedule 1: Cycle 1 Day 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | 2.5 mg/m2 (N=3) | 3.75 mg/m2 (N=1) | 4.5 mg/m2 (N=4) | 5.6 mg/m2 (N=2) | Schedule Total (N=10) |

| AUCinf (hr*ng/mL) | 1650 (17.2) | 1480 (NC) | 3000 (66.1) | 2520 (NC) | NA |

| CL (L/hr) | 2.69 (6.90) | 6.77 (NC) | 2.95 (67.7) | 4.30 (NC) | 3.36 (50.7) |

| Vss (L) | 405 (87.4) | 857 (NC) | 340 (10.8) | 515 (NC) | 446 (55.2) |

| t1/2 (hr) | 97.2 (64.4 – 291) | 100 (100 – 100) | 100 (29.5 – 149) | 92.5 (44.9 – 140) | 98.6 (29.5 – 291) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 132 (1410) | 31.1 (NC) | 53.4 (39.9) | 49.6 (NC) | NA |

| Tmax (hr) | 2.00 (1.00 – 2.03) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.00) | 1.01 (1.00 – 1.08) | 0.959 (0.917 – 1.00) | 1.00 (0.917 – 2.03) |

| MRT (hr) | 92.7 (53.2 – 314) | 127 (127 – 127) | 142 (42.7 – 202) | 131 (63.7 – 198) | 127 (42.7 – 314) |

| Schedule 2: Cycle 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | 0.8 mg/m2 (N=3) | 1.2 mg/m2 (N=6) | 1.5 mg/m2 (N=6) | 1.8 mg/m2 (N=2) | 3.6 mg/m2 (N=1) | Schedule Total (N=18) |

| Day 1 | ||||||

| AUC0–24 (hr*ng/mL) | 116 (161) | 133 (58.1) | 264 (142) | 208 (NC) | 345 (NC) | NA |

| CL (L/hr) | 6.55 (87.2) | 7.82 (110) | 5.90 (92.5) | 7.81 (NC) | 11.2 (NC) | 7.12 (81.5) |

| Vss (L) | 295 (82.7) | 363 (50.7) | 251 (81.5) | 306 (NC) | 278 (NC) | 306 (57.6) |

| t1/2 (hr) | 29.8 (4.44 – 30.6) | 25.6 (22.2 – 61.1) | 26.1 (16.6 – 32.4) | 27.1 (25.8 – 28.4) | 18.7 (18.7 – 18.7) | 26.1 (4.44 – 61.1) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 19.5 (550) | 18.8 (22.9) | 57.9 (590) | 24.4 (NC) | 73.9 (NC) | NA |

| Tmax (hr) | 1.00 (0.983 – 1.00) | 1.09 (1.00 – 2.25) | 1.00 (1.00 – 2.00) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.00) | 1.00 (0.983 – 2.25) |

|

| ||||||

| Day 3 | ||||||

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 6.68 (108) | 29.8 (116) | 79.8 (393) | 47.1 (NC) | 70.3 (NC) | 35.6 (245) |

| Tmax (hr) | 1.08 (1.00 – 1.18) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.25) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.08) | 0.959 (0.917 – 1.00) | 1.08 (1.08 – 1.08) | 1.00 (0.917 – 1.25) |

|

| ||||||

| Day 5 | ||||||

| AUC0–24 (hr*ng/mL) | 179 (75.7) | 320 (96.9) | 667 (134) | 608 (NC) | 733 (NC) | NA |

| CL (L/hr) | 2.03 (62.5) | 0.947 (51.4) | 1.11 (70.9) | 1.10 (NC) | 1.33 (NC) | 1.19 (60.1) |

| Vss (L) | 193 (82.5) | 239 (95.8) | 169 (70.3) | 127 (NC) | 202 (NC) | 191 (78.0) |

| t1/2 (hr) | 92.5 (33.3 – 93.3) | 94.9 (75.3 – 572) | 82.2 (32.2 – 350) | 80.0 (77.4 – 82.6) | 108 (108 – 108) | 92.5 (32.2 – 572) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 25.3 (567) | 24.3 (80.8) | 134 (465) | 53.6 (NC) | 199 (NC) | NA |

| Tmax (hr) | 1.08 (1.00 – 1.08) | 1.00 (1.00 – 2.08) | 1.02 (0.983 – 2.00) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.00) | 1.08 (1.08 – 1.08) | 1.00 (0.983 – 2.08) |

| MRT (hr) | 130 (24.8 – 132) | 134 (108 – 819) | 119 (37.6 – 421) | 114 (108 – 119) | 152 (152 – 152) | 130 (24.8 – 819) |

Note: Parameters are reported as geometric mean (geometric %CV) with exceptions of MRT, t1/2 and Tmax which are median (min-max) and Vss which is mean (%CV). Not applicable (NA). NC (not calculated).

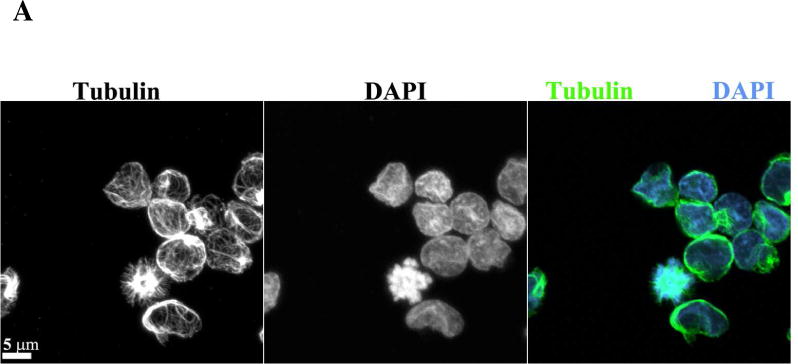

A common defect observed with KSP inhibition is monopolar spindle formation; therefore, microtubule spindle morphology was imaged in PBMCs from Cycle 1, Day 5 in patients dosed at 1.2 mg/m2/day. As shown in Figure 2, aberrant spindles along with misaligned DNA were observed in some PBMCs of these patients using confocal imaging of tubulin and DAPI (DNA). Thus, these results are consistent with the on-target activity of ARRY-520.

Figure 2.

Aberrant spindles are observed in PBMCs after ARRY-520 treatment. Confocal imaging of PBMCs from patients with (A) DAPI (B) tubulin and (C) merge of tubulin and DAPI staining.

Discussion

This Phase 1 trial sought to identify an optimal dose schedule and the MTD of ARRY-520 in patients with relapsed/refractory AML or advanced MDS. This study demonstrated that the single-dose schedule of ARRY-520 (Schedule 1) and the multi-dose schedule (Schedule 2) where ARRY-520 was given on Days 1, 3 and 5 were comparable. The MTD was defined at the same total dose per cycle for both schedules (4.5 mg/m2 total dose). The DLTs included oral mucositis at 5.6 mg/m2 with the single-dose schedule and at 1.2 mg/m2/day with the multi-dose schedule (3.6 mg/m2 total dose/cycle), with additional AEs of hand-foot syndrome and hyperbilirubinemia observed at 1.8 mg/m2/day (4.5 mg/m2 total dose).

Overall, ARRY-520 demonstrated an acceptable safety profile in both schedules at dose levels up to the MTD (4.5 mg/m2), with no difference in the toxicity observed between the two schedules. Drug-related SAEs occurred in 28% of patients and led to study discontinuation in 8%. Neurotoxicity was not observed at any dose up to the MTD.

PK parameters demonstrated moderately high inter-patient variability and overall dose-dependent increases in exposure. The half-life of ARRY-520 (> 90 hours) was consistent with the low clearance and relatively large volume of distribution when administered once per cycle and displayed a similar terminal phase with more frequent dosing. These values suggest the potential for prolonged exposure of ARRY-520 at the site of action. Based on imaging of PBMCs (Figure 2) ARRY-520 appears to be targeting the microtubule spindle, since abnormal spindles were observed in patients after 3 doses of ARRY-520. This is consistent with mitotic defects observed both in vitro and in vivo following KSP inhibition.34,35

ARRY-520 has shown activity in xenograft models of multiple myeloma,36 which led to a Phase 1/2 trial in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. The trial is currently in Phase 2 after the MTD was reached with ARRY-520 administered on Days 1 and 2 repeated every 2 weeks. This trial has shown promising preliminary responses, and led to the development of a Phase 1b study of ARRY-520 administered on Days 1, 2, 15 and 16 every 4 weeks in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone. Of interest, other KSP inhibitors are currently being investigated in clinical trials. These include: AZD4877, MK0371 and SB-715992/ispinesib. Preliminary results of a Phase 2 trial have shown that ispinesib has clinical activity in patients with resistant ovarian cancer.37

In the current study, although ARRY-520 demonstrated an acceptable safety profile in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory AML or MDS, we did not observe complete remissions in this patient population. The detection of monopolar spindles was suggestive of targeted KSP inhibition and it is possible that mucositis was a limiting factor for further dose escalation to identify an effective dose. Alternatively, it may be unrealistic to expect responses using a single agent in this highly resistant patient population. Combination of ARRY-520 with a synergistic drug is perhaps a more optimal approach to better evaluate the efficacy of this drug. Based on the relative lack of clinical activity, no further development of this agent as an antileukemic therapy is planned.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laura Bender for her contribution to the imaging techniques.

FUNDING STATEMENT:

This article was funded by P30 CA016672.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Salena Rush and Mieke Ptaszynski – Array BioPharma Inc. Employment, Hagop Kantarjian-Commercial Research Funding, Gautam Borthakur – Consultant and Advisory Board Member.

Presented as a Poster at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, December 2009

References

- 1.Mayer RJ, Davis RB, Schiffer CA, et al. Intensive Postremission Chemotherapy in Adults with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. NEJM Volume. 1994 Oct 6;331:896–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glucksberg H, Cheever MA, Farewell VT, et al. High-dose combination chemotherapy for acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia in adults. Cancer. 1981;48:1073–81. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810901)48:5<1073::aid-cncr2820480504>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preisler HD, Rustum Y, Henderson ES, et al. Treatment of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: use of anthracycline-cytosine arabinoside induction therapy and comparison of two maintenance regimens. Blood. 1979;53:455–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips GL, Reece DE, Shepherd JD, et al. High-dose cytarabine and daunorubicin induction and postremission chemotherapy for the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia in adults. Blood. 1991;77:1429–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tricot G, Boogaerts MA, Vlietinck R, et al. The role of intensive remission induction and consolidation therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1987;66:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb06887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiernik PH, Banks PL, Case DC, Jr, et al. Cytarabine plus idarubicin or daunorubicin as induction and consolidation therapy for previously untreated adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1992;79:313–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaise D, Maraninchi D, Archimbaud E, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: a randomized trial of a busulfan-Cytoxan versus Cytoxan-total body irradiation as preparative regimen: a report from the Group d’Etudes de la Greffe de Moelle Osseuse. Blood. 1992;79:2578–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linker CA, Ries CA, Damon LE, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia using busulfan plus etoposide as a preparative regimen. Blood. 1993;81:311–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassileth PA, Harrington DP, Appelbaum FR, et al. Chemotherapy compared with autologous or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in the management of acute myeloid leukemia in first remission. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(23):1649. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812033392301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson BA, Bloomfield CD. Long-term disease-free survival in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1981;57:1144–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rai KR, Holland JF, Glidewell OJ, et al. Treatment of acute myelocytic leukemia: a study by cancer and leukemia group B. Blood. 1981;58:1203–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstein HJ, Mayer RJ, Rosenthal DS, et al. Chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia in children and adults: VAPA update. Blood. 1983;62:315–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson BA, Bloomfield CD. Prolonged maintained remissions of adult acute non-lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet. 1977;2:158–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Passe S, Mike V, Mertelsmann R, et al. Acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia: prognostic factors in adults with long-term follow-up. Cancer. 1982;50:1462–71. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821015)50:8<1462::aid-cncr2820500804>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velu T, Debusscher L, Stryckmans P. Daunorubicin in patients with relapsed and refractory acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia previously treated with anthracycline. Am J Hematol. 1988;27:224–5. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830270315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willemze R, Zwaan FE, Colpin G, et al. High dose cytosine arabinoside in the management of refractory acute leukaemia. Scand J Haematol. 1982;29:141–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1982.tb00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herzig RH, Wolff SN, Lazarus HM, et al. High-dose cytosine arabinoside therapy for refractory leukemia. Blood. 1983;62:361–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzig RH, Lazarus HM, Wolff SN, et al. High-dose cytosine arabinoside therapy with and without anthracycline antibiotics for remission reinduction of acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3:992–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.7.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duval M, Klein JP, He W, et al. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute leukemia in relapse or primary induction failure. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3730–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman PJ, Fraley ME. Inhibitors of the mitotic kinesin spindle protein. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 2004;14:1659–1667. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vale RD, Milligan RA. The way things move: looking under the hood of molecular motor proteins. Science. 2000;288:88–95. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapoor TM, Mayer TU, Coughlin ML, et al. Probing spindle assembly mechanisms with monastrol, a small molecule inhibitor of the mitotic kinesin, Eg5. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:975–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawin KE, LeGuellec K, Philippe M, et al. Mitotic spindle organization by a plus-end-directed microtubule motor. Nature. 1992;359:540–3. doi: 10.1038/359540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blangy A, Lane HA, d’Herin P, et al. Phosphorylation by p34cdc2 regulates spindle association of human Eg5, a kinesin-related motor essential for bipolar spindle formation in vivo. Cell. 1995;83:1159–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakowicz R, Finer JT, Beraud C, et al. Antitumor activity of a kinesin inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3276–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer TU, Kapoor TM, Haggarty SJ, et al. Small molecule inhibitor of mitotic spindle bipolarity identified in a phenotype-based screen. Science. 1999;286:971–4. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox CD, Breslin MJ, Mariano BJ, et al. Kinesin spindle protein (KSP) inhibitors. Part 1: The discovery of 3,5-diaryl-4,5-dihydropyrazoles as potent and selective inhibitors of the mitotic kinesin KSP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:2041–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lobell J, Deihl R, Mahan E, et al. In vivo Characterization of an Inhibitor of the Mitotic Kinesin, KSP: Pharmacodynamics, Efficacy, and Tolerability in Xenograft Tumor Models. AACR-NCI-EORTC Int Conf Mol Targets Cancer Ther B. 2005:189. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzales P, Bienek A, Piazza G, et al. Breadth of anti-tumor activity of CK0238273 (SB-715992), a novel inhibitor of the mitotic kinesin KSP. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res (AACR) 2002:1337. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson R, Caulder E, Inlow-Porter L, et al. A potent and selective inhibitor of the mitotic kinesin KSP, demonstrates broad-spectrum activity in advanced murine tumors and human tumor xenografts. AACR Abstract. 2002:1335. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woessner R, Tunquist B, Lemieux C, et al. ARRY-520, a novel KSP inhibitor with potent activity in hematological and taxane-resistant tumor models. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4373–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood. 2006;108:419–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang S, Schafer-Hales K, Khuri FR, et al. The tumor suppressor LKB1 regulates lung cancer cell polarity by mediating cdc42 recruitment and activity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:740–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcus AI, Peters U, Thomas SL, et al. Mitotic Kinesin Inhibitors Induce Mitotic Arrest and Cell Death in Taxol-resistant and -sensitive Cancer Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:11569–11577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413471200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakowicz R, Finer JT, Beraud C, et al. Antitumor Activity of a Kinesin Inhibitor. Cancer Research. 2004;64:3276–3280. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tunquist BJ, Woessner RD, Walker DH. Mcl-1 Stability Determines Mitotic Cell Fate of Human Multiple Myeloma Tumor Cells Treated with the Kinesin Spindle Protein Inhibitor ARRY-520. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2010;9:2046–2056. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomez HL, Castaneda C, Pimentel P, et al. A phase I/II trial of ispinesib, a kinesin spindle protein (KSP) inhibitor, dosed q14d in patients with advanced breast cancer previously untreated with chemotherapy for metastatic disease or recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. (suppl; abstr 1077), 2009. [Google Scholar]