Abstract

In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), intravenous (i.v.) injection of the antigen, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-derived peptide, MOG35-55, suppresses disease development, a phenomenon called i.v. tolerance. Galectin-1, an endogenous glycan-binding protein, is upregulated during autoimmune neuroinflammation and plays immunoregulatory roles by inducing tolerogenic dendritic cells (DCs) and IL-10-producing regulatory type 1 T (Tr1) cells. To examine the role of galectin-1 in i.v. tolerance, we administered MOG35-55-i.v. to wild-type (WT) and galectin-1-deficient (Lgals1−/−) mice with ongoing EAE. MOG35-55 suppressed disease in the WT, but not in the Lgals1−/− mice. The numbers of Tr1 cells and Tregs were increased in the CNS and periphery of tolerized WT mice. In contrast, Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice had reduced numbers of Tr1 cells and Tregs in the CNS and periphery, and reduced IL-27, IL-10 and TGF-β1 expression. DCs derived from i.v. tolerized WT mice suppressed disease when adoptively transferred into mice with ongoing EAE, whereas DCs from Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice were not suppressive. These findings demonstrate that galectin-1 is required for i.v. tolerance induction, likely via induction of tolerogenic DCs leading to enhanced development of Tr1 cells, Tregs and downregulation of pro-inflammatory responses.

Keywords: Tolerance, Galectin-1, Tolerogenic DCs, Tr1 cells, Tregs

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). Its animal model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), can be induced by immunizing mice with myelin antigens, and induction of antigen-specific tolerance can effectively ameliorate EAE [1–4]. Tolerance can be achieved by intravenous (i.v.) administration of antigen in various forms, including soluble peptide/protein [5, 6], and antigen-coupled nanoparticles [7]. I.v. administration of an encephalitogenic peptide following immunization for EAE induction, or after disease onset, induces antigen-specific tolerance and ameliorates disease [2, 8]. In mice immunized with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein 35-55 (MOG35-55) peptide for EAE induction, i.v. injection of MOG35-55 (MOG-i.v.) suppressed pro-inflammatory T cell responses and induced FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) [4, 6, 9, 10]. Increased proportions of CD11c+CD11b+ dendritic cells (DCs) were found in the spleens and CNS of mice i.v. injected with MOG35-55. This DC subset inhibited MOG35-55-specific T cell proliferation, induced Tregs and regulatory cytokines IL-10, IL-27 and TGF-β, and suppressed EAE when adoptively transferred [6, 11, 12].

Galectin-1, a β-galactosidase binding protein, plays an important immunoregulatory role in EAE [13, 14]. Galectin-1 is synthesized and secreted by Tregs, and is also upregulated in activated B and T cells, inflammatory macrophages, and decidual natural killer (NK) cells [15, 16]. Furthermore, galectin-1 promotes the differentiation of IL-27-producing tolerogenic DCs [14], which supports the development of regulatory type 1 T (Tr1) cells [14, 20–22]. Additionally, galectin-1-induced Tr1 cells suppress Th1- and Th17-mediated inflammation [17]. Mice deficient in galectin-1 (Lgals1−/−) have augmented Th1 and Th17 responses and are more susceptible to autoimmune diseases and immune-mediated fetal rejection when compared with WT mice [15, 23].

In the present study we investigate the role of galectin-1 in the induction of i.v. tolerance in EAE. Our findings highlight the importance of galectin-1 in the induction of i.v. tolerance by inducing tolerogenic DCs that promote expansion of Tr1 cells and Tregs in the CNS and periphery, leading to the downregulation of pro-inflammatory responses and suppression of EAE.

Results

Galectin-1 is required for induction of i.v. tolerance

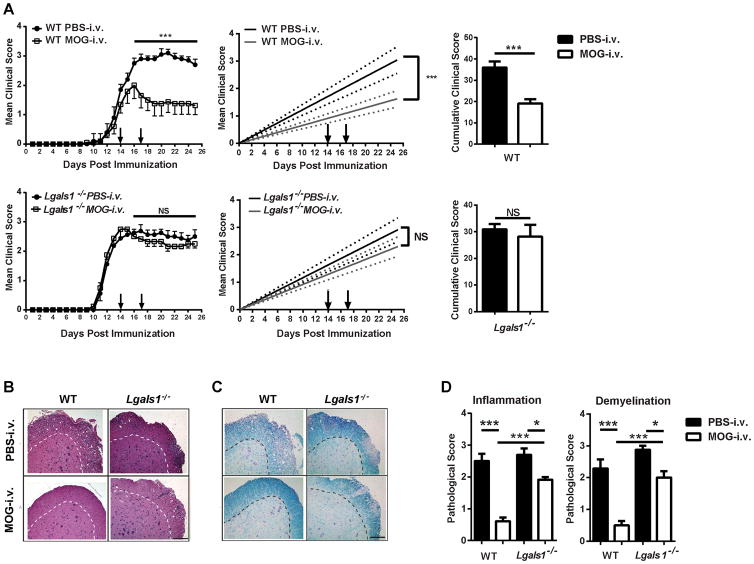

Our laboratory has shown that i.v. administration of MOG35-55 (MOG-i.v.) after EAE onset reduces clinical disease and induces immune tolerance by generating tolerogenic DCs and expanding FoxP3+ Tregs [6]. Galectin-1 plays a role in the induction of tolerogenic DCs and Tr1 cells and in the suppressive function of Tregs [14, 17, 18]. To investigate whether galectin-1 plays a role in i.v. tolerance, Lgals1−/− and wild-type (WT) mice were immunized with MOG35-55 for EAE induction and administered two doses of MOG-i.v. at days 14 and 17 p.i. or PBS-i.v. as control. WT MOG-i.v. mice had a significant reduction in clinical disease when compared to WT PBS-i.v. control mice (Fig. 1A), whereas Lgals1−/− mice were resistant to i.v. tolerance induction. Consistent with this clinical finding, histological analysis revealed multiple inflammatory loci and extensive demyelination in the lumbar spinal cord of WT PBS-i.v. mice. In contrast, the WT MOG-i.v. mice had few inflammatory loci and little demyelination (Fig. 1B–D). Similar to WT PBS-i.v. mice, Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. and MOG-i.v. mice both had multiple inflammatory loci and extensive demyelination. These data demonstrate that galectin-1 is required for i.v. tolerance induction in EAE.

Figure 1. Galectin-1 deficient mice are resistant to i.v. tolerance induction.

(A) WT (n=7) and Lgals1−/− (n=6) mice were immunized with MOG35-55 to develop EAE. Two hundred μg of MOG35-55 in PBS were injected i.v. on days 14 and 17 p.i. Mice that received PBS i.v. served as controls. Clinical EAE was scored on a 0–5 scale. Linear-regression curves (right panel). Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Cumulative clinical scores were pooled from four experiments. Data show mean ± SEM. (B, C) On day 25 p.i. spinal cords were harvested, and 5 μm sections from the lumbar spinal cord were stained with H&E and Luxol fast blue. Shown are examples of (B) H&E or (C) Luxol fast blue staining for WT and Lgals1−/− mice that received PBS or MOG35-55 i.v.; Magnifications, ×10; scale bar = 10 μm. (D) Mean scores of inflammation and demyelination ± SD in MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. mice. One representative experiment of four is shown. *, p<0.05; ***, p < 0.001. For EAE, the area under the curve was calculated for each mouse and values for experimental groups were compared for statistical significance using a Mann-Whitney test for non-parametric data. Parametric data sets were analyzed using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction. One-way ANOVA was used for comparisons between multiple groups.

Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice have fewer Tr1 cells, Tregs and tolerogenic DCs in the CNS

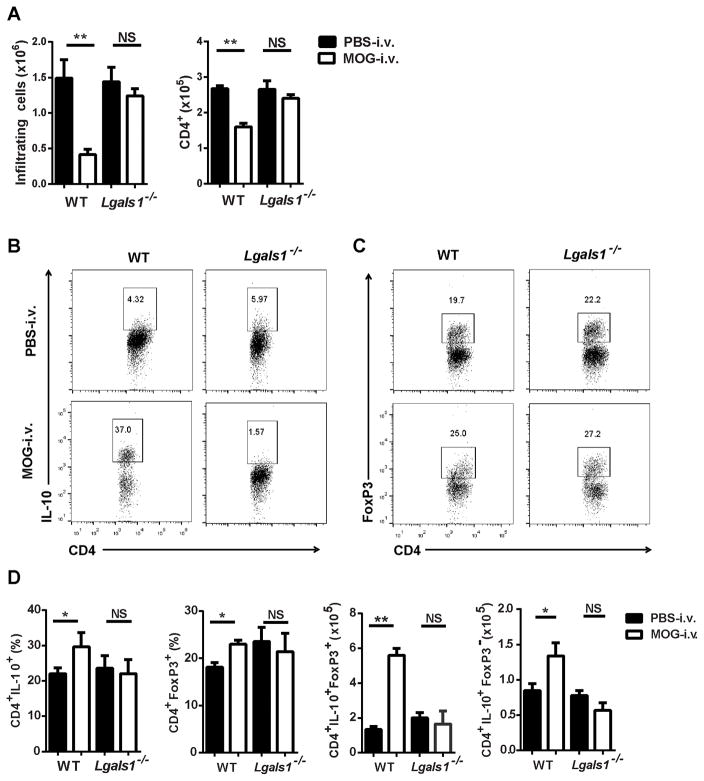

I.v. tolerance induction and long-lasting immunosuppression in EAE correlates with an increase in Tregs and tolerogenic DCs in the CNS [6]. We therefore examined cells from the CNS of mice 25 days p.i. WT MOG-i.v. mice had a significant reduction in the total numbers of CNS-infiltrating mononuclear cells (MNCs) and CD4+ T cells when compared to WT PBS-i.v. mice. There was no reduction in the total number of CNS-infiltrating cells or CD4+ T cells obtained from the Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice. However, WT MOG-i.v. mice had a significant increase in the proportions of CNS Tr1 cells and Tregs when compared with WT PBS-i.v. mice (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice had decreased proportions of Tr1 cells and Tregs in the CNS when compared with Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. mice; however, there was no change in Tr1 and Treg numbers (Fig. 2B–D). Additionally, WT MOG-i.v. mice had significantly reduced proportions and total numbers of CD4+IFN-γ+, CD4+IL-17A+, and CD4+GM-CSF+ T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1A–C). No significant decreases in these pathogenic T cell subsets were observed in the Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice (Supplemental Fig. 1A and B), which is consistent with the lack of i.v. tolerance induction in these mice.

Figure 2. I.v. tolerized Lgals1−/− mice have reduced numbers of Tr1 cells and Tregs in the CNS.

MNCs were isolated from the CNS of MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT (n=7) and Lgals1−/− (n=6) mice on day 25 p.i. (A) MNCs were cultured overnight with MOG35-55 (10 μg/ml), activated with PMA + ionomycin + Golgi plug (PMA/iono/GP), then stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing IL-10 expression in CD4+ T cells. (C) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing FoxP3 expression on CD4+ T cells. (D) Proportions and absolute numbers of infiltrating Tr1 cells and Tregs were determined for WT and Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. mice. Pooled data from four experiments are shown. Experiments show mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

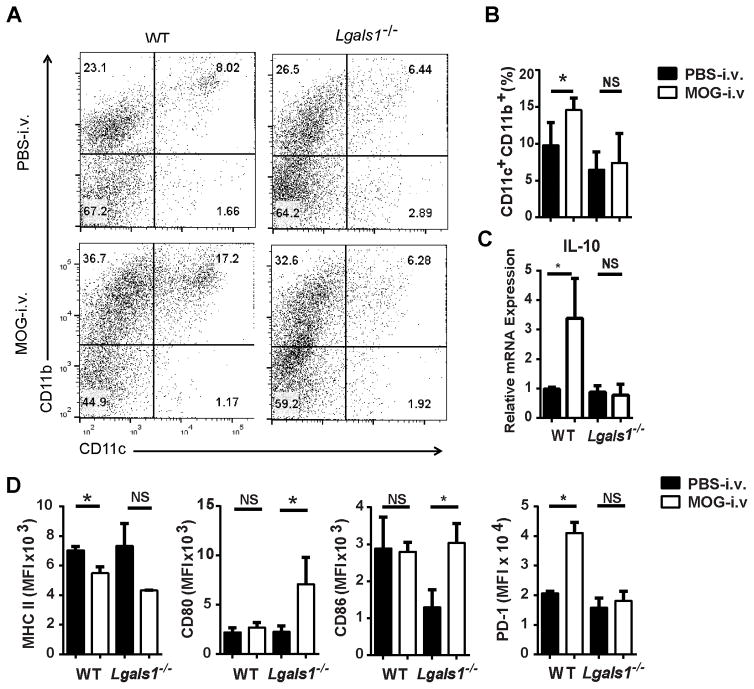

We next examined the CNS-infiltrating DCs. In comparison with Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. mice, Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice had decreased proportions of CD11c+CD11b+ DCs among cells from the CNS, and these DCs had decreased expression of MHC class II molecules, but increased expression of CD80 and CD86 (Fig. 3A–C and Supplemental Fig. 2). Expression of CD103, CD83 and CD40 was also measured and no significant changes were observed (data not shown). In addition, the DCs from Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice had decreased expression of the surface marker PD-1, which plays a role in T cell apoptosis and promotes the survival of Tregs [24–26]. This marker was increased in DCs from the WT MOG-i.v. mice, suggesting an increased tolerogenic function (Fig. 3C and Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 3. Lack of galectin-1 reduced numbers of tolerogenic DCs in the CNS.

MNCs were isolated from the CNS of MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT (n=7) and Lgals1−/− (n=6) mice on day 25 p.i. MNCs were cultured overnight with MOG35-55, then activated with PMA/iono/GP, stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing CD11c and CD11b expression in MNCs. (B) Proportions of CD11c+CD11b+ DCs were determined for WT and Lgals1−/− MOG i.v. and PBS i.v. mice. (C) MFI was measured for MHC class II, CD80, CD86 and PD-1 in CD11c+CD11b+ DCs. (D) IL-10 mRNA was measured using RT-PCR. Pooled data from four experiments are shown. Experiments show mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

Tolerogenic DCs secrete high amounts of IL-10 and IL-27 [6, 11, 14]. WT MOG-i.v. mice had increased expression of IL-10 mRNA in DCs from the CNS when compared to WT PBS-i.v. mice. This increased expression of IL-10 in DCs was not observed in the Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice (Fig. 3D). No significant increase in IL-27 was observed in DCs of WT MOG-i.v. and Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice (data not shown). Additionally, we observed no change in the proportions of M1 and M2 macrophages in the CNS of WT MOG-i.v. and Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice when compared to PBS-i.v. mice (data no shown). Taken together, these data indicate the need for galectin-1 in the expansion of Tregs and Tr1 cells, and for IL-10 production in CD11c+CD11b+ DCs in the CNS.

Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice have increased pro-inflammatory responses and fewer Tr1 cells and Tregs in the periphery

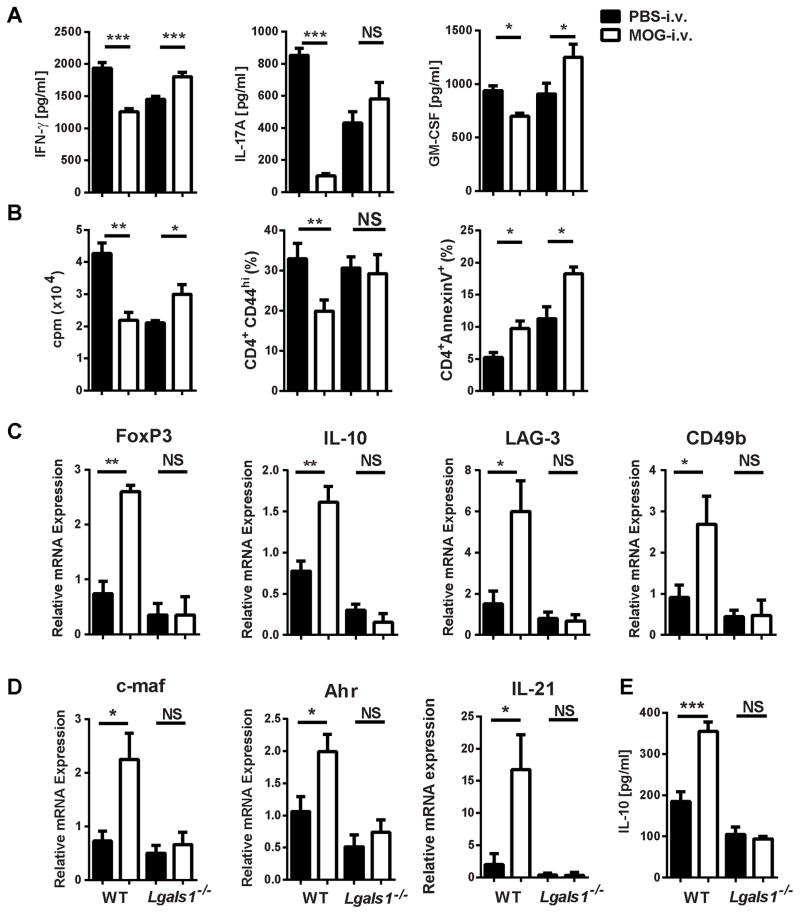

Successful tolerance induction involves the suppression of pro-inflammatory, antigen-specific T cell responses. To determine if cytokine expression in i.v. tolerance is affected by the absence of galectin-1 splenocytes from WT MOG-i.v., Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice and their respective PBS-i.v. controls were stimulated for three days with MOG35-55 and cytokine concentrations were measured in culture supernatants. We observed significant increases in IFN-γ and GM-CSF in Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice when compared with Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. mice (Fig. 4A), while antigen-specific proliferation remained unchanged (Fig. 4B). This was in stark contrast to the cytokine profile of WT MOG-i.v. mice, which had significant reductions in IFN-γ, GM-CSF and IL-17 secretion and in antigen-specific proliferation.

Figure 4. Lack of galectin-1 leads to increased pro-inflammatory responses and reduced numbers of Tregs in the periphery of i.v. tolerized mice.

Splenocytes from MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT and Lgals1−/− mice on day 25 p.i. were stimulated for three days with MOG35-55. (A) Cell culture supernatants were assayed for IFN-γ, IL-17A and GM-CSF by ELISA (B) Proliferation was measured in splenocytes after three days of culture with MOG35-55. Tritiated adenine was added after 54 hours of culture; its incorporation was measured after 18 hours. CD4+AnnexinV+ and CD4+CD44hi T cells from the spleen were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 25 p.i. (C) IL-10, LAG-3, CD49b and FoxP3 mRNAs in splenocytes were measured using RT-PCR. (D) IL-10 concentrations in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. (E) c-maf, Ahr and IL-21 mRNAs in splenocytes were measured using RT-PCR. Data shown are one representative of four experiments. Experiments show mean ± SD. *, p<0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, unpaired Student’s t test.

It has been shown that apoptosis of T cells occurs soon after i.v. peptide administration [9]. Annexin V staining of CD4+ T cells was measured in the spleens of mice on day 18 p.i., the day following the last dose of i.v. MOG35-55. As expected, in the WT MOG-i.v. mice there was a significant increase in CD4+ T cell apoptosis when compared to PBS-i.v. mice (5.2 ± 0.8% WT PBS-i.v. vs. 9.7 ± 1.2% WT MOG-i.v.) (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice had increased CD4+ T cell apoptosis when compared to Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. mice (Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. 11.3 ± 1.9% vs. Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. 18.3 ± 1.1%) (Fig. 4B). Despite this increased apoptosis in Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice, there was no change in T cell activation as measured by expression of CD44 on CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4B). Thus, lack of i.v. tolerance in Lgals1−/− mice correlates with increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased antigen-specific proliferation.

To characterize Tr1 and Treg populations, we determined expression of lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) and CD49b and IL-10 production [27] in MOG35-55-stimulated splenocytes. The WT MOG-i.v. splenocytes had a significant increase in IL-10, LAG-3 and CD49b when compared with WT PBS-i.v. splenocytes. Additionally, we found increased levels of FoxP3 in WT MOG-i.v. splenocytes but not in the Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. splenocytes (Fig. 4C and D). In contrast, Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. splenocytes had no significant change in the expression of IL-10, LAG-3 and CD49b when compared with Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. splenocytes. In WT MOG-i.v. splenocytes, there was also an increase in Tr1 cell transcription factors c-maf and Ahr, and the Tr1 inducing cytokine IL-21, which was not seen in the Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. splenocytes when compared to their respective PBS-i.v. controls (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these findings suggest that lack of i.v. tolerance induction in Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice is associated with impaired development of Tr1 cells and Tregs.

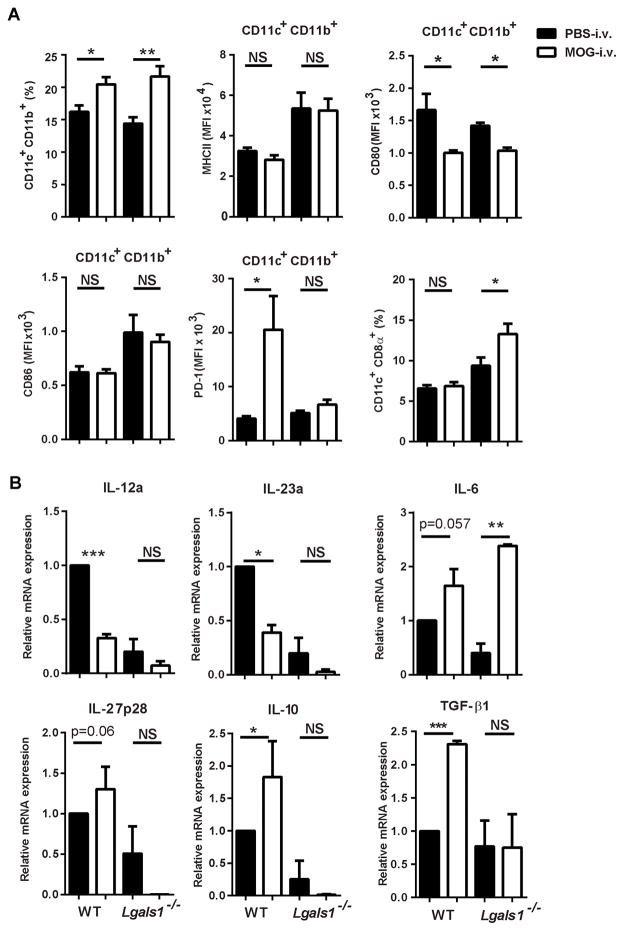

Lack of galectin-1 reduces tolerogenic DC function in the periphery of i.v. tolerized mice

Tolerogenic DCs were characterized in the spleen, as they are known to promote the expansion of Tregs and Tr1 cells [6, 12, 28]. WT MOG-i.v. and Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice had increased proportions of CD11c+CD11b+ DCs. These DCs had no significant changes in MHC class II expression when compared to PBS-i.v. control mice (Fig. 5A), and both sets of DCs from MOG-i.v. mice had reduced expression of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86. PD-1 expression was significantly increased in the WT MOG-i.v. mice when compared to WT PBS-i.v. control mice, while Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice showed no change in PD-1 expression. Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice had significantly increased proportions of pro-inflammatory CD11c+CD8α+ DCs [6, 29, 30] (Fig. 5A). No significant changes in expression of CD103, CD83 and CD40 were found in the WT MOG-i.v. or Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice when compared to PBS-i.v. controls (data not shown).

Figure 5. Lack of galectin-1 reduces tolerogenic DC phenotype in the periphery of i.v. tolerized mice.

Splenocytes from MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT and Lgals1−/− mice on day 25 p.i. were stimulated for three days with MOG35-55. (A) Splenocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry and the proportions of CD11c+CD11b+ DCs were determined. MFI was measured for MHC class II, CD80, CD86 and PD-1 in CD11c+CD11b+ DCs. (B) CD11c+ DC were purified from the splenocytes of WT and Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. mice, and IL-12a, IL-23a, IL-6, IL-27p28, IL-10 and TGF-β1 mRNAs were measured using RT-PCR. Data shown are pooled from three experiments. Experiments show mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, unpaired Student’s t test.

To further examine the functional profile of peripheral DCs, we analyzed cytokine production in CD11c+ DCs purified from the spleens of WT and Lgals1−/− mice. We detected reduced expression of IL-12 and IL-23 and increased IL-6 mRNA production in the Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice, which was similar to the CD11c+ cells from WT MOG-i.v. mice (Fig. 5B). Unlike the WT MOG-i.v. DCs, which had significantly increased expression of IL-10 and IL-27p28 mRNA, the Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. DCs had low to virtually inexistent expression of these mRNA transcripts. TGF-β1 levels were similar between Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. and Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. mice, while WT MOG-i.v. DCs had significantly increased levels of TGF-β1 when compared to WT PBS-i.v. controls (Fig. 5B). Recently, it has been shown that IL-27 induces DCs to express the immunoregulatory molecule CD39 [31], and levels of this mRNA transcript were increased in WT MOG-i.v. DCs and decreased in Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. DCs. These changes were not statistically significant when compared to PBS-i.v. controls (data not shown).

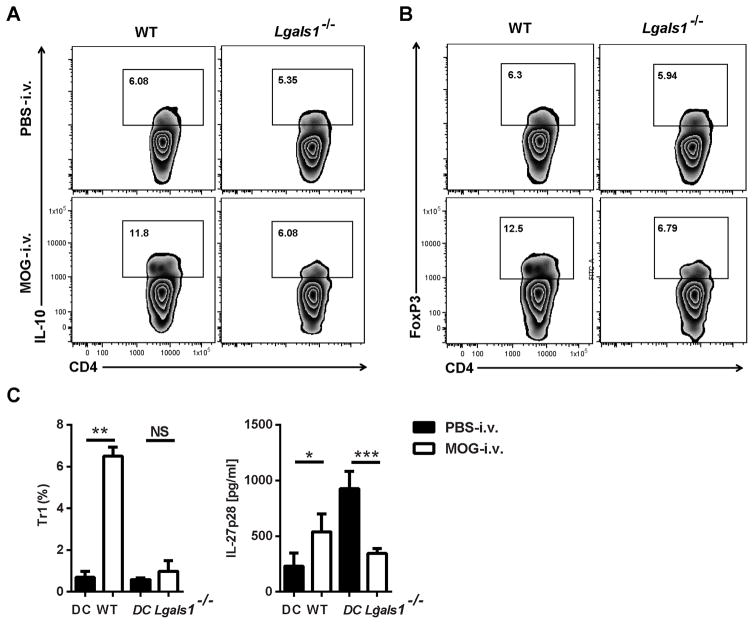

To characterize the capacity of DCs from Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice to induce Tr1 cells and Tregs, we co-cultured CD11c+ DCs with CD4+ T cells from MOG35-55-specific 2D2 mice. No significant increase in the proportions of Tr1 cells and Tregs was observed in the co-culture with Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. DCs when compared with Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. DCs (Fig. 6A and B). Significantly greater proportions of Tr1 cells were observed in the T cells co-cultured with WT MOG-i.v. DCs when compared with DCs from WT PBS-i.v. mice. In addition, increased concentrations of IL-27 were found in cell culture supernatants from the co-cultures with WT MOG-i.v. DCs when compared to co-cultures with WT PBS-i.v. DCs. However, there was a significant reduction in IL-27 concentrations in cell culture supernatants from co-cultures with Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. DCs when compared with supernatants from co-cultures with Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. DCs (Fig. 6C). The reduced expression of IL-27, IL-10 and TGF-β1 by DCs of Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice indicates that galectin-1 is necessary for the generation of DCs with the tolerogenic phenotype [14] and the expansion of Tr1 cells and Tregs.

Figure 6. Lack of galectin-1 reduces tolerogenic DC function in the periphery of i.v. tolerized mice.

CD11c+ splenic DCs were purified from MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT and Lgals1−/− mice on day 21 p.i. and pulsed with MOG35-55 peptide. DCs were co-cultured (1:1) with CD4+ T cells from MOG35-55-specific 2D2 mice for 72 hours. (A) CD4+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and representative dot plots showing expression of IL-10 and gated CD4+ T cells. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing expression of FoxP3 in gated CD4+ T cells. (C) The proportions of LAG-3+CD49b+ Tr1 cells were determined from within the IL-10 expressing CD4+ cells and IL-27p28 concentrations in cell culture supernatants measured by ELISA. Data shown are one representative of three experiments. Experiments show mean ± SD. *, p<0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, unpaired Student’s t test.

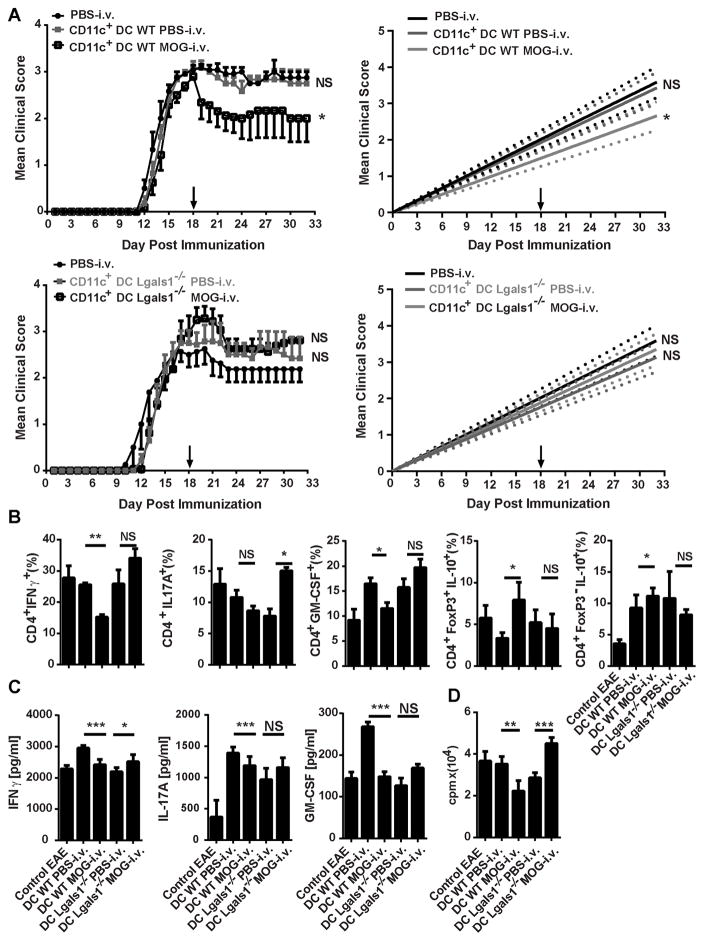

DCs from Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice do not suppress clinical EAE

Our laboratory has previously shown that CD11c+CD11b+ DCs from i.v. tolerized mice suppress ongoing disease when i.v. injected into EAE mice [6]. To ascertain if DCs from Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice are tolerogenic in vivo, we separated CD11c+ cells from the spleens of Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. and WT MOG-i.v. mice, and their respective PBS-i.v. controls. These cells were i.v. injected into WT mice with EAE, and clinical disease was followed for two weeks. Mice that received WT MOG-i.v. DCs had a significant reduction in clinical disease when compared with those that received WT PBS-i.v. DCs (Fig. 7A). In contrast, mice that received Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. DCs developed more severe disease (Fig. 7A). EAE mice that were given WT MOG-i.v. DCs had significantly decreased proportions of CD4+IFN-γ+ and CD4+GM-CSF+ T cells in the CNS when compared to mice that received WT PBS-i.v. DCs. Additionally, the mice that were given WT MOG-i.v. DCs had increased proportions of Tregs or Tr1 cells in the CNS. In contrast, EAE mice that received Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. DCs had significantly increased proportions of IFN-γ+, IL-17A+, and GM-CSF+ CD4+ T cells in the CNS when compared with EAE mice given Lgals1−/− PBS-i.v. DCs. Mice that received Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. DCs had no increase in the proportions of Tregs or Tr1 cells in the CNS (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. DCs from Lgals1−/− MOG i.v. mice do not suppress EAE.

(A) WT (n=6) and Lgals1−/− (n=6) mice were sacrificed 3 weeks after MOG35-55 i.v. tolerization. CD11c+ DCs were isolated from splenocytes and i.v. transferred into WT EAE mice (1×106 mouse; n=3–5 per group) at disease peak. Mice that received PBS-i.v. served as controls. (B) Two weeks after transfer, MNCs from the CNS of DC-transferred mice and EAE controls were isolated. MNCs were cultured overnight with MOG35-55, activated with PMA/iono/GP, stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. Total numbers of infiltrating cells were gated from CD4+ population. CD4+IFNγ+, CD4+IL-17A+, CD4+GM-CSF+, CD4+IL-10+FoxP3+, and CD4+IL-10+FoxP3− percentages in CD4+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry. (C) Splenocytes from MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT and Lgals1−/− mice on day 25 p.i. were stimulated for three days with MOG35-55. Cell culture supernatants were assayed for IFN-γ, IL-17A and GM-CSF by ELISA. (D) Proliferation was measured after three days of culture with MOG35-55. Tritiated adenine was added after 54 hours of culture; its incorporation was measured after 18 hours. Data shown are one representative of three experiments. Experiments show mean ± SD. *, p<0.05. For EAE, the area under the curve was calculated for each mouse and values for experimental groups were compared for statistical significance using a Mann-Whitney test for non-parametric data. Parametric data were compared for statistical significance using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

To characterize the peripheral immune response after DC transfer, we stimulated splenocytes from EAE mice i.v. injected with DCs for three days with MOG35-55 and measured cytokine concentrations in culture supernatants. We found significantly less IFN-γ, IL-17A and GM-CSF, and decreased MOG35-55-specifc proliferation of splenocytes from mice that received WT MOG-i.v. DCs (Fig. 7C). Significantly increased IFN-γ concentration was found in cell culture supernatants of mice that received Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. DCs but no significant increase in IL-17A and GM-CSF was detected. There was significantly increased MOG35-55-specific proliferation (Fig. 7D). Thus, galectin-1 contributes to the generation of tolerogenic DCs after administration of MOG-i.v. and their ability to promote the expansion of Tr1 cells and Tregs.

Discussion

Induction of i.v. tolerance is associated with suppressed Th1 and Th17 responses, expansion of Tregs and Tr1 cells and the generation of tolerogenic DCs [6, 32]. Recent studies have shown an immunoregulatory role for galectin-1 in EAE by inducing the expansion of Tr1 cells through the generation of IL-27-producing tolerogenic DCs [14]. We have shown here, for the first time, that galectin-1 is essential for i.v. tolerance induction. In the absence of galectin-1, the induction of Tr1 cells, Tregs and tolerogenic DCs was impaired in the CNS and peripheral immune system following administration of i.v. autoantigen. Notably, DCs of mice lacking galectin-1 were unable to suppress ongoing EAE and had a reduced capacity to induce Tr1 cells and Tregs. These findings demonstrate that galectin-1 bestows tolerogenic function on DCs after administration of i.v. autoantigen, which is crucial for the generation of regulatory T cell subsets and the downregulation of pro-inflammatory responses that lead to the suppression of EAE.

Administration of i.v. autoantigen reduces inflammatory cell infiltration in the CNS, which is associated with a decrease in inflammatory lesions and demyelination [6]. Previous studies have described a role for galectin-1 in inhibiting T cell recruitment, and showed increased homing of lymphocytes to lymphoid organs in Lgals1−/− mice under inflammatory conditions [33, 34]. Galectin-1 expression in the white matter of the spinal cord is increased at EAE disease peak, suggesting that galectin-1 may limit lymphocyte recruitment in the CNS [35]. In accordance with these findings, our data show the increased infiltration of lymphocytes into the CNS of Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice, which had more inflammation and demyelination when compared with WT MOG-i.v. mice.

I.v. injection of high doses of peptide induces apoptosis of antigen-specific T cells, which is important for the generation of tolerance [8, 9]. Toscano et al. showed that galectin-1 promoted apoptosis in antigen-specific Th1 and Th17 cells in EAE, whereas Th2 cells were protected because of differential sialylation of cell surface glycoproteins that renders them less susceptible to binding of galectin-1 [23, 36–39]. This process can modulate the threshold of T cell receptor signaling and favor the activation-induced cell death (AICD) of effector T cells [23, 40]. Consistent with this, our data showed that WT MOG-i.v. mice had increased proportions of Annexin V+ CD4+ T cells when compared with WT PBS-i.v. mice. In addition, Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice also had increased proportions of Annexin V+ CD4+ T cells, indicating that lack of galectin-1 does not reduce apoptosis of T cells. This finding highlights the notion that augmentation of T cell apoptosis alone is not sufficient for i.v. tolerance induction.

DCs can play opposing roles in EAE by either inducing or preventing disease [6, 41]. Tolerogenic DCs are identified within the CD11c+CD11b+ subset by low expression of MHC class II, CD80, CD86 and CD40. Decreased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IL-23, and upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10, IL-27 and TGF-β also characterize this DC subset [29, 30, 42, 43]. Treatment of DCs with galectin-1 reduces the expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules and induces a tolerogenic phenotype [14]. In accordance with previous findings, our data show that the CNS DCs from WT MOG-i.v. mice had reduced expression of MHC class II, CD80 and CD86, while expression of CD80 and CD86 was increased in DCs from the CNS of Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice. Additionally, we observed increased PD-1 on WT MOG-i.v. DCs in the CNS. Salama et al. showed that PD-1 blockade resulted in increased antigen-specific T cell proliferation and cytokine production in EAE [24, 25]. Increased PD-1 expression on DCs and engagement with B7-H1 receptor enhance IL-10 production [26], which could account for the increased IL-10 production we observed in the WT MOG-i.v. DCs. These findings indicate that in the absence of galectin-1, i.v. tolerance induction upregulates expression of costimulatory molecules and induces pro-inflammatory, rather than tolerogenic DC phenotype.

Galectin-1 has also been shown to stimulate the expansion and suppressive function of Tregs [14, 18]. Starossom et al. showed that CNS-infiltrating FoxP3+ Treg cells express high amounts of galectin-1 during preclinical disease, highlighting the role of galectin-1 as a mediator of the their immunosuppressive function [18, 35]. Moreover, our data show that the numbers of Tregs were reduced in the CNS of Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice, while they were significantly increased in WT MOG-i.v. mice, suggesting that galectin-1 directly contributes to Treg expansion in the CNS following i.v. autoantigen administration.

IL-27 is a potent inducer of IL-10 production in T cells and is secreted in high amounts by tolergenic DCs [11, 44]. It is known that galectin-1 promotes tolerance through the generation of IL-27-producing DCs [14]. In our i.v. tolerance model, the absence of galectin-1 led to reduced expression of IL-27 and IL-10 mRNA transcripts in MOG-i.v. DCs and diminished their capacity to promote the generation of Tr1 cells both in vivo and in vitro. DCs can induce Treg generation in the presence of IL-6 and TGF-β1 [45]. In DCs from Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. mice we observed significantly increased expression of IL-6 mRNA transcripts, but reduced expression of TGF-β1. Recipient mice that were given Lgals1−/− MOG-i.v. DCs had more pathogenic T cells and decreased proportions of Tregs and Tr1 cells in the CNS. Collectively, these data suggest a role for galectin-1 in the generation of IL-27-producing tolerogenic DCs and induction of IL-10-producing Tr1 cells after administration of i.v. autoantigen. We also highlight a function for galectin-1 in TGF-β1 production by DCs and induction of FoxP3+ Treg cells after administration of i.v. autoantigen.

Our findings demonstrate an essential role for galectin-1 in i.v. tolerance induction. We propose that i.v. injection of autoantigen increases the synthesis of galectin-1 [18]. Galectin-1 binds to DCs and induces IL-27- and TGF-β1-producing tolerogenic DCs, which lead to the generation of IL-10-producing Tr1 cells and Tregs. Tr1 cells and Tregs downregulate pro-inflammatory responses in the CNS and periphery, and suppress EAE. These results stress the importance of galectin-1 as the immunosuppressive signal that links Tregs, tolerogenic DCs and Tr1 cells in i.v. tolerance.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Eight- to 12-week old wild-type (WT) female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Lgals1−/− mice on C57BL/6 background were kindly provided by Dr. José Conejo-Garcia (Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA) and Dr. Naveen Rajasagi (University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN). These mice were previously described by Poirier and Robertson [46]. 2D2 mice on C57BL/6 background were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Thomas Jefferson University.

Induction of EAE and i.v. tolerance

Mice were immunized s.c. with 200 μg MOG35-55 (Genscript, CA), emulsified in CFA (IFA supplemented with 5 mg/ml M. tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) at two sites on the back. Mice were injected with 200 ng of pertussis toxin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS on days 0 and 2 p.i. and were scored daily using an EAE clinical scale as detailed below. Before tolerance, mice were divided into groups with similar average scores. To induce i.v. tolerance 200 μg/mouse of MOG35-55 peptide was i.v. injected at days 14 and 17 p.i. and mice that received the same volume (200 μl) of PBS i.v. in parallel served as EAE controls. Mice were scored daily according to the following scale: 0, no sign of clinical disease; 1, paresis of the tail; 2, paresis of one hind limb; 3, paresis of both hind limbs; 4, paresis of the abdomen; 5, moribund/death.

Histopathology

On week 3 p.i., mice were extensively perfused with ice-cold PBS and spinal cords were harvested. Lumbar sections of spinal cord were fixed with 10% formalin, extracted, embedded in paraffin and cut into 5 μm serial sections for H&E or Luxol fast blue (myelin stain) staining. Slides were assessed in a blind fashion for inflammation and demyelination. Spinal cord sections were scored for inflammation: 0, none; 1, a few inflammatory cells; 2, organization of perivascular infiltrates; and 3, increased severity of perivascular cuffing with extension into adjacent tissue. For demyelination: 0, none; 1, rare foci; 2, a few areas of demyelination; 3, large areas of demyelination.

Isolation of CNS cells

CNS tissues were mechanically dissociated through a 70-μm strainer and washed with PBS. The resultant pellet was fractionated on a 70/30% Percoll (Sigma, USA) gradient by centrifugation at 300 × g for 20 min. Mononuclear cells were harvested from the 70/30% interface.

T cell proliferation assay

In order to analyze proliferation, splenic cells (4 × 105) were cultured in IMDM medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, USA), 5% L-glutamine (Gibco, USA), 5% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Gibco, USA) and β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, USA) in triplicate with MOG35-55 (25 μg/ml), or alone. After 54 h, cells were pulsed for 18 h with 1 μCi of 3H-methylthymidine. Cells were harvested and analyzed using a β-counter.

Flow Cytometry

In order to detect intracellular cytokines, cells from the spleen and the CNS were activated with Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (50 ng/ml, Sigma), ionomycin (500 ng/ml, Sigma), and GolgiPlug (1 μg per 1×106 cells, BD Biosciences) for 4 h. Cells were then washed in staining buffer containing 3% FCS and 0.1% sodium azide in PBS and stained for surface and intracellular cytokines and markers with antibodies to mouse: CD4 Pacific Blue (RM4-5, BD Biosciences), CD8α PerCP-Cy5.5 (53-6.7, BD Biosciences), CD44 APC (IM7, BD Biosciences), Annexin V PE (BD Biosciences), GM-CSF PE (MP1-22E9, eBiosciences), IL-17A FITC (TC11-18H10, BD Biosciences), IFN-γ APC (XMG1.2, BD Biosciences), FoxP3 FITC (FJK-16s, eBiosciences), LAG3 APC (eBioC9B7W, eBiosciences), CD49b PE (DX5, eBiosciences), and IL-10 PerCP-Cy5.5 (JES5-16E3, eBiosciences).

Prior to surface staining, DCs were treated with anti-CD16/CD32 antibodies (BD Biosciences) and then stained with the following surface antibodies to: mouse CD11c Pacific Blue (HL3, BD Biosciences), CD11b PerCp-Cy5.5 (M1/70, BD Biosciences), MHCII FITC (2G9, BD Biosciences), CD80 PE (16-10A1, BD Biosciences), CD86 APC (GL-1, BD Biosciences), PD-1 PE (J43, BD Biosciences), CD103 FITC (M290, BD Biosciences), and CD40 APC (3/23, BD Biosciences). All flow cytometric analyses were performed using the following isotype controls: FITC Rat IgG1, Rat IgG2a; PE Rat IgG2a, Rat IgG2k; APC Rat IgG2a, Rat IgG1; PerCP-Cy5.5 Rat IgG2b. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with Caltag Fix/Perm reagents (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were acquired on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Cytokine quantification

Splenocytes were stimulated with MOG35-55 for three days; supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until the day of analysis. GM-CSF, IL-27, IL-10, IL-17A and IFN-γ concentrations were quantified by ELISA (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from the spleen, spinal cord and cells using RNeasy columns (Qiagen, USA); cDNA was then prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems). PCR was performed using the following primer-probe mixtures (Applied Biosystems); IL-12a (Mm00434165_m1), IL-23a (Mm00518984_m1), IL-6 (Mm00446190_m1), IL-10 (Mm0043614_m1), IL-27 (Mm00461162_m1), TGF-β1 (Mm01178820_m1), CD39 (Mm00515447_m1), FoxP3 (Mm00475162_m1), CD49b (Mm00434371_m1), LAG-3 (Mm00493071_m1). The values were compared to GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1) to normalize and compare to controls.

DC transfer

Donor mice were immunized and tolerance was induced on day 14 p.i. On day 21, the donor mice were sacrificed, and their spleens were harvested. DCs were extracted from the spleen by collagenase D digestion (Sigma, USA) and dead cells were removed with the Dead Cell Removal Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA). DCs were purified using anti-mouse CD11c-coated magnetic beads according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA). Cells selected on the basis of CD11c expression routinely consisted of >90% viable DCs. Following purification, DCs were washed with PBS and intravenously injected into recipients through the tail vein (200 μl, 1 × 106 cells/mouse).

DC co-culture

CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleen of 2D2 mice using anti-CD4 mAb-conjugated microbeads according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA). Cells (5 × 105) were then incubated with or without MOG35-55 (25 μg/ml), and with CD11c+ DCs (5 × 105) that had been purified from the spleens of tolerized and non-tolerized mice. After 3 days of culture, CD4+ T cells were analyzed using flow cytometry and supernatants were collected and stored at 20°C until the day of analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Prism GraphPad 6 software was used for determining statistical significance. For EAE studies, the area under the curve was calculated for each mouse, and values of experimental groups were compared for statistical significance using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. FACS, ELISA and RT-PCR data were compared using a two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction where appropriate. One-way ANOVA was used for comparisons between multiple groups. Data were considered statistically significant where p<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: I.v. tolerized Lgals1−/− mice do not have reduction in numbers of pathogenic CD4+ T cells in the CNS.

MNCs were isolated from the CNS of MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT (n=7) and Lgals1−/− (n=6) mice on day 25 p.i. MNCs were cultured overnight with MOG35-55, then activated with PMA/iono/GP, stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plot showing IFN-γ and IL-17A expression in CD4+ T cells from one experiment. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot-plots showing GM-CSF expression in CD4+ T cells from one experiment. (C) The absolute number of infiltrating CNS MNCs, CD4+IFNγ+, CD4+IL-17A+ and CD4+ GM-CSF+ T cells was determined. Pooled data from four experiments are shown mean± SEM. (A, B) One representative experiment of four is shown. *, p<0.05, **, p < 0.01, unpaired Student’s t test.

Supplemental Figure 2: Lack of galectin-1 reduces tolerogenic DC phenotype in the CNS.

MNCs were isolated from the CNS of MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT (n=7) and Lgals1−/− (n=6) mice on day 25 p.i. MNCs were cultured overnight with MOG35-55 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry histograms show MHC class II, CD80, CD86 and PD-1 in CD11c+CD11b+ DCs. Data shown are representative of four experiments. Experiments show mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank K. Regan for editorial assistance. This work was supported by grant R01AI106026 from the National Institutes of Health. J. Moore was supported by National Institutes of Health training grant T32GM008562. E.R.M., J.R. and J.N.M. performed experiments. E.R.M., G.X.Z. and A.R. were involved in the experimental design. J.R.G and N.R. provided the Lgals1−/− mice. E.R.M., B.C., G.X.Z., and A.R. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the methodology of the experiments and data analyses.

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cell

- MNC

mononuclear cell

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- Tr1

T regulatory type 1 cell

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no commercial or financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Weiner HL, Friedman A, Miller A, Khoury SJ, al-Sabbagh A, Santos L, Sayegh M, Nussenblatt RB, Trentham DE, Hafler DA. Oral tolerance: immunologic mechanisms and treatment of animal and human organ-specific autoimmune diseases by oral administration of autoantigens. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:809–837. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller A, Zhang ZJ, Sobel RA, al-Sabbagh A, Weiner HL. Suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by oral administration of myelin basic protein. VI. Suppression of adoptively transferred disease and differential effects of oral vs. intravenous tolerization. J Neuroimmunol. 1993;46:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90235-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitkanen J, Peterson P. Autoimmune regulator: from loss of function to autoimmunity. Genes Immun. 2003;4:12–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puentes F, Dickhaut K, Hofstatter M, Falk K, Rotzschke O. Active suppression induced by repetitive self-epitopes protects against EAE development. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilliard BA, Kamoun M, Ventura E, Rostami A. Mechanisms of suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by intravenous administration of myelin basic protein: role of regulatory spleen cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 2000;68:29–37. doi: 10.1006/exmp.1999.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Zhang GX, Chen Y, Xu H, Fitzgerald DC, Zhao Z, Rostami A. CD11c+CD11b+ dendritic cells play an important role in intravenous tolerance and the suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;181:2483–2493. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter Z, McCarthy DP, Yap WT, Harp CT, Getts DR, Shea LD, Miller SD. A biodegradable nanoparticle platform for the induction of antigen-specific immune tolerance for treatment of autoimmune disease. ACS Nano. 2014;8:2148–2160. doi: 10.1021/nn405033r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liblau RS, Tisch R, Shokat K, Yang X, Dumont N, Goodnow CC, McDevitt HO. Intravenous injection of soluble antigen induces thymic and peripheral T-cells apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3031–3036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang GX, Yu S, Calida D, Zhao Z, Gran B, Kamoun M, Rostami A. Loss of the surface antigen 3G11 characterizes a distinct population of anergic/regulatory T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;176:3366–3373. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang Z, Li H, Fitzgerald DC, Zhang GX, Rostami A. MOG(35-55) i v suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis partially through modulation of Th17 and JAK/STAT pathways. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:789–799. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awasthi A, Carrier Y, Peron JP, Bettelli E, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M, Weiner HL. A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1380–1389. doi: 10.1038/ni1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasanthakumar A, Kallies A. IL-27 paves different roads to Tr1. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:882–885. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toscano MA, Ilarregui JM, Bianco GA, Campagna L, Croci DO, Salatino M, Rabinovich GA. Dissecting the pathophysiologic role of endogenous lectins: glycan-binding proteins with cytokine-like activity? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilarregui JM, Croci DO, Bianco GA, Toscano MA, Salatino M, Vermeulen ME, Geffner JR, Rabinovich GA. Tolerogenic signals delivered by dendritic cells to T cells through a galectin-1-driven immunoregulatory circuit involving interleukin 27 and interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:981–991. doi: 10.1038/ni.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kopcow HD, Rosetti F, Leung Y, Allan DS, Kutok JL, Strominger JL. T cell apoptosis at the maternal-fetal interface in early human pregnancy, involvement of galectin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18472–18477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809233105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabinovich GA, Toscano MA. Turning ‘sweet’ on immunity: galectin-glycan interactions in immune tolerance and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:338–352. doi: 10.1038/nri2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cedeno-Laurent F, Opperman M, Barthel SR, Kuchroo VK, Dimitroff CJ. Galectin-1 triggers an immunoregulatory signature in Th cells functionally defined by IL-10 expression. J Immunol. 2012;188:3127–3137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garin MI, Chu CC, Golshayan D, Cernuda-Morollon E, Wait R, Lechler RI. Galectin-1: a key effector of regulation mediated by CD4+CD25+ T cells. Blood. 2007;109:2058–2065. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Lu ZH, Gabius HJ, Rohowsky-Kochan C, Ledeen RW, Wu G. Cross-linking of GM1 ganglioside by galectin-1 mediates regulatory T cell activity involving TRPC5 channel activation: possible role in suppressing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2009;182:4036–4045. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Leij J, van den Berg A, Harms G, Eschbach H, Vos H, Zwiers P, van Weeghel R, Groen H, Poppema S, Visser L. Strongly enhanced IL-10 production using stable galectin-1 homodimers. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toscano MA, Commodaro AG, Ilarregui JM, Bianco GA, Liberman A, Serra HM, Hirabayashi J, Rizzo LV, Rabinovich GA. Galectin-1 suppresses autoimmune retinal disease by promoting concomitant Th2- and T regulatory-mediated anti-inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2006;176:6323–6332. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stowell SR, Qian Y, Karmakar S, Koyama NS, Dias-Baruffi M, Leffler H, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Differential roles of galectin-1 and galectin-3 in regulating leukocyte viability and cytokine secretion. J Immunol. 2008;180:3091–3102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toscano MA, Bianco GA, Ilarregui JM, Croci DO, Correale J, Hernandez JD, Zwirner NW, Poirier F, Riley EM, Baum LG, Rabinovich GA. Differential glycosylation of TH1, TH2 and TH-17 effector cells selectively regulates susceptibility to cell death. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:825–834. doi: 10.1038/ni1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salama AD, Chitnis T, Imitola J, Ansari MJ, Akiba H, Tushima F, Azuma M, Yagita H, Sayegh MH, Khoury SJ. Critical role of the programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway in regulation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2003;198:71–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao S, Wang S, Zhu Y, Luo L, Zhu G, Flies S, Xu H, Ruff W, Broadwater M, Choi IH, Tamada K, Chen L. PD-1 on dendritic cells impedes innate immunity against bacterial infection. Blood. 2009;113:5811–5818. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Said EA, Dupuy FP, Trautmann L, Zhang Y, Shi Y, El-Far M, Hill BJ, Noto A, Ancuta P, Peretz Y, Fonseca SG, Van Grevenynghe J, Boulassel MR, Bruneau J, Shoukry NH, Routy JP, Douek DC, Haddad EK, Sekaly RP. Programmed death-1-induced interleukin-10 production by monocytes impairs CD4+ T cell activation during HIV infection. Nat Med. 2010;16:452–459. doi: 10.1038/nm.2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gagliani N, Magnani CF, Huber S, Gianolini ME, Pala M, Licona-Limon P, Guo B, Herbert DR, Bulfone A, Trentini F, Di Serio C, Bacchetta R, Andreani M, Brockmann L, Gregori S, Flavell RA, Roncarolo MG. Coexpression of CD49b and LAG-3 identifies human and mouse T regulatory type 1 cells. Nat Med. 2013;19:739–746. doi: 10.1038/nm.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamazaki S, Iyoda T, Tarbell K, Olson K, Velinzon K, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Direct expansion of functional CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells by antigen-processing dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:235–247. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maldonado-Lopez R, De Smedt T, Pajak B, Heirman C, Thielemans K, Leo O, Urbain J, Maliszewski CR, Moser M. Role of CD8alpha+ and CD8alpha- dendritic cells in the induction of primary immune responses in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:242–246. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillon S, Agrawal S, Banerjee K, Letterio J, Denning TL, Oswald-Richter K, Kasprowicz DJ, Kellar K, Pare J, van Dyke T, Ziegler S, Unutmaz D, Pulendran B. Yeast zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin-1, induces regulatory antigen-presenting cells and immunological tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:916–928. doi: 10.1172/JCI27203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mascanfroni ID, Yeste A, Vieira SM, Burns EJ, Patel B, Sloma I, Wu Y, Mayo L, Ben-Hamo R, Efroni S, Kuchroo VK, Robson SC, Quintana FJ. IL-27 acts on DCs to suppress the T cell response and autoimmunity by inducing expression of the immunoregulatory molecule CD39. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1054–1063. doi: 10.1038/ni.2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang GX, Gran B, Yu S, Li J, Siglienti I, Chen X, Kamoun M, Rostami A. Induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in IL-12 receptor-beta 2-deficient mice: IL-12 responsiveness is not required in the pathogenesis of inflammatory demyelination in the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2003;170:2153–2160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norling LV, Sampaio AL, Cooper D, Perretti M. Inhibitory control of endothelial galectin-1 on in vitro and in vivo lymphocyte trafficking. FASEB J. 2008;22:682–690. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9268com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabinovich GA, Sotomayor CE, Riera CM, Bianco I, Correa SG. Evidence of a role for galectin-1 in acute inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1331–1339. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200005)30:5<1331::AID-IMMU1331>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starossom SC, Mascanfroni ID, Imitola J, Cao L, Raddassi K, Hernandez SF, Bassil R, Croci DO, Cerliani JP, Delacour D, Wang Y, Elyaman W, Khoury SJ, Rabinovich GA. Galectin-1 deactivates classically activated microglia and protects from inflammation-induced neurodegeneration. Immunity. 2012;37:249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haak S, Croxford AL, Kreymborg K, Heppner FL, Pouly S, Becher B, Waisman A. IL-17A and IL-17F do not contribute vitally to autoimmune neuro-inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:61–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI35997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, Nambu A, Ishigame H, Kakuta S, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:566–573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kroenke MA, Carlson TJ, Andjelkovic AV, Segal BM. IL-12- and IL-23-modulated T cells induce distinct types of EAE based on histology, CNS chemokine profile, and response to cytokine inhibition. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1535–1541. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaser C, Kaufmann M, Muller C, Zimmermann C, Wells V, Mallucci L, Pircher H. Beta-galactoside-binding protein secreted by activated T cells inhibits antigen-induced proliferation of T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2311–2319. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199808)28:08<2311::AID-IMMU2311>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greter M, Heppner FL, Lemos MP, Odermatt BM, Goebels N, Laufer T, Noelle RJ, Becher B. Dendritic cells permit immune invasion of the CNS in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2005;11:328–334. doi: 10.1038/nm1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pulendran B, Smith JL, Caspary G, Brasel K, Pettit D, Maraskovsky E, Maliszewski CR. Distinct dendritic cell subsets differentially regulate the class of immune response in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1036–1041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fitzgerald DC, Zhang GX, El-Behi M, Fonseca-Kelly Z, Li H, Yu S, Saris CJ, Gran B, Ciric B, Rostami A. Suppression of autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system by interleukin 10 secreted by interleukin 27-stimulated T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1372–1379. doi: 10.1038/ni1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darrasse-Jeze G, Deroubaix S, Mouquet H, Victora GD, Eisenreich T, Yao KH, Masilamani RF, Dustin ML, Rudensky A, Liu K, Nussenzweig MC. Feedback control of regulatory T cell homeostasis by dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1853–1862. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poirier F, Robertson EJ. Normal development of mice carrying a null mutation in the gene encoding the L14 S-type lectin. Development. 1993;119:1229–1236. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: I.v. tolerized Lgals1−/− mice do not have reduction in numbers of pathogenic CD4+ T cells in the CNS.

MNCs were isolated from the CNS of MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT (n=7) and Lgals1−/− (n=6) mice on day 25 p.i. MNCs were cultured overnight with MOG35-55, then activated with PMA/iono/GP, stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plot showing IFN-γ and IL-17A expression in CD4+ T cells from one experiment. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot-plots showing GM-CSF expression in CD4+ T cells from one experiment. (C) The absolute number of infiltrating CNS MNCs, CD4+IFNγ+, CD4+IL-17A+ and CD4+ GM-CSF+ T cells was determined. Pooled data from four experiments are shown mean± SEM. (A, B) One representative experiment of four is shown. *, p<0.05, **, p < 0.01, unpaired Student’s t test.

Supplemental Figure 2: Lack of galectin-1 reduces tolerogenic DC phenotype in the CNS.

MNCs were isolated from the CNS of MOG-i.v. and PBS-i.v. EAE WT (n=7) and Lgals1−/− (n=6) mice on day 25 p.i. MNCs were cultured overnight with MOG35-55 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry histograms show MHC class II, CD80, CD86 and PD-1 in CD11c+CD11b+ DCs. Data shown are representative of four experiments. Experiments show mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.