Abstract

Purpose of review

As the number of female cancer survivors continues to grow, there is a growing need to bridge the gap between the high rate of women's cancer-related sexual dysfunction and the lack of attention and intervention available to the majority of survivors who suffer from sexual problems. Previously identified barriers that hinder communication for providers include limited time, lack of preparation, and a lack of patient resources and access to appropriate referral sources.

Recent findings

This paper brings together a recently developed model for approaching clinical inquiry about sexual health with a brief problem checklist that has been adapted for use for female cancer survivors, as well as practical evidence-based strategies on how to address concerns identified on the checklist. Examples of patient education sheets are provided, as well as strategies for building a referral network.

Summary

By providing access to a concise and efficient tool for clinical inquiry, as well as targeted material resources and practical health-promoting strategies based on recent evidence-based findings, we hope to begin eliminating the barriers that hamper oncology providers from addressing the topic of sexual/vaginal health after cancer.

Keywords: Sexual health, cancer, provider communication

Introduction

As rates of cancer survivorship continue to improve, there is increasing concern that treatment-related sexual dysfunction will continue to go unaddressed for many female patients and survivors [1-3]. Despite calls for improving provider-patient communication about sexual health [4,*5], research shows that frank conversations about sexuality and vaginal health after cancer do not regularly take place between patients and medical providers [6,7]. Although cancer patients and survivors want to address cancer-related sexual problems with their medical team [8], the majority of female cancer patients/survivors are not communicating with their providers about this distressing consequence of their cancer treatment.

Studies have identified a range of barriers that hinder optimal patient-provider communication about sexual concerns of women with cancer. From the provider perspective, barriers include a lack of training about sexual health [9], limited time [10], concerns about offending patients or making them uncomfortable [8,11], and as uncertainty about how to manage this dimension of care [12]. Without appropriate training and confidence in addressing this subject, it can be challenging for clinicians to find appropriate language to ask about sexual health and decipher comments from patients [13].

Furthermore, patients/survivors are also not likely to initiate this discussion [14]. From the patient perspective, barriers include not wanting to make their doctor uncomfortable, belief that it is the provider's responsibility to initiate the discussion, and worry that sexual dysfunction will not be viewed as a valid concern [15]. These mutual barriers often result in an unfortunate stalemate in the consulting room, leading to unmet patient needs. Over and beyond the unmet need for communication about sexual health after cancer, survivors also perceive a loss of self-efficacy and confidence regarding how to address their sexual dysfunction [16]. When clinicians and patients do not communicate about sexual health after cancer, these perceptions may be reinforced and patients may wrongly conclude that little or nothing can be done to manage the sexual side effects of cancer and cancer treatments. Finally, communication about sexual health is further hampered by a lack of available brief and effectual patient resources, such as simple clinical checklists, educational materials, and appropriate referral resources [17]. Taken together, the multitude of challenges that patients and providers face in discussing sexual concerns after cancer and subsequent treatment leads to a “perfect storm,” which leaves these women in the midst of a vast, unaddressed lapse in comprehensive healthcare.

Clinicians who want to initiate discussions about sexual health with their patients need guidance in how to start these conversations and what types of questions to ask. In order help meet these needs, the aims of this paper are to: 1) present a brief checklist that has been adapted for use, based on expert opinion, with female cancer survivors in order to foster discussion about sexual health, 2) describe how the 5 A's model for approaching clinical inquiry about sexual health can be enhanced by integrating the use of the checklist, and 3) offer practical strategies for how to address concerns identified on the checklist, including specific examples of patient education sheets about particular common problems after cancer. By providing healthcare professionals with a concise and efficient tool for clinical inquiry and useful material resources, we can begin to eliminate barriers to addressing sexual and vaginal health after cancer.

Clinical Inquiry and “The Checklist”

A variety of sexual function measures developed for the general population have been used in clinical research investigating women's sexual function in the context of cancer. However, only a few have been validated in the female cancer patient or survivor populations such as the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) [18],and the Sexual Function Questionnaire [19]. More recently, the comprehensive Sexual Function and Satisfaction measure was developed by the National Institutes of Health's Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) Network [**20]. The PROMIS measure, composed of 81 items that span 11 domains [21], was created as a patient-reported outcome measure and may also have potential use in clinical practice. While standardized assessment tools enable clinical research, they tend to be too lengthy and time and labor intensive for routine use in a busy clinical practice [13]. They also may yield an overabundance of information for the provider to address. In addition, because a sexual function inventory such as the FSFI was not specifically developed for cancer survivors, there are particular challenges for female cancer survivors that may not be adequately captured on this general measure. Thus, although valid instruments assessing female sexual dysfunction have been developed, there remains a significant need for a brief checklist feasible for application within the clinical setting that is targeted to the particular problems of female cancer survivors.

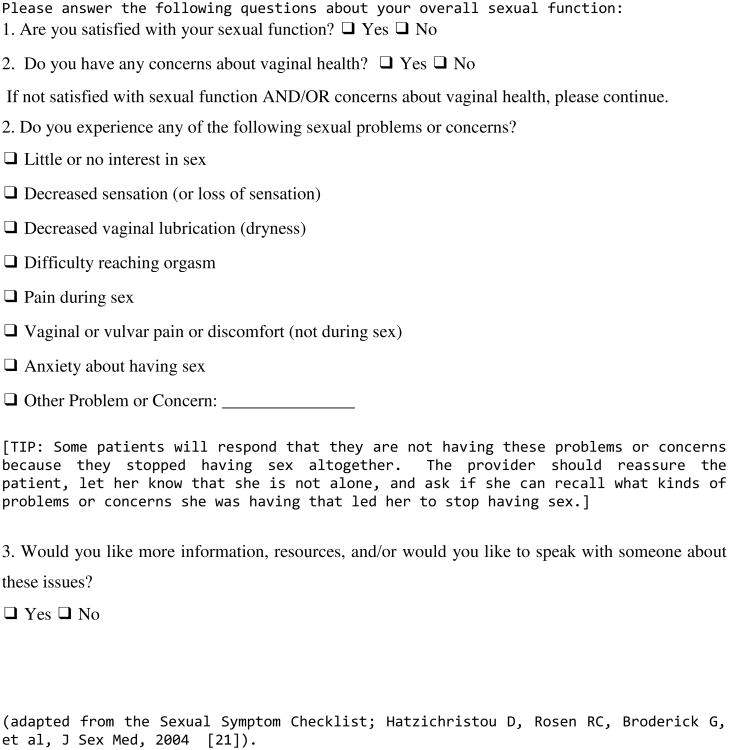

The Checklist

In 2004, an international collaboration of sexual medicine experts created consensus guidelines regarding clinical evaluation of sexual dysfunction in women [22]. They created a brief screening checklist intended for use in the general female population in primary care settings to facilitate initial identification of sexual problems. Members of the Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer [23], a multidisciplinary working group of experts in the field of female sexual health and cancer, have adapted this brief screening checklist to be used either as a self-report checklist or as a springboard for guiding clinical conversations about treatment-related sexual problems between female cancer survivors and their healthcare providers (The checklist can be found in Figure 1 [22]).

Figure 1. Sexual Symptom Checklist for Women after Cancer.

This checklist is intended for use with female cancer patients and survivors, regardless of age, partner status, sexual orientation, or current level of sexual activity. The symptom checklist can be used serially as an objective indicator of improvement in patient symptoms. Providers can review with the patient changes in symptoms reported on the checklist over time and use this information as a guide for ongoing treatment. The checklist also contains a prompt for providers to offer reassurance to women who are no longer sexually active due to treatment-induced problems, making them aware that they are not alone in this situation and that help is available.

It is also important to note that pre-existing issues of pain, dryness, and changes in sexual response can be longstanding, often preceding a woman's cancer diagnosis and treatment. However, these problems can be exacerbated by cancer treatment. The following recommendations apply regardless of onset or duration of sexual/vaginal health concern but may need to be additionally tailored to individual patients for the effective resolution and control of symptoms, ultimately leading to improved optimal sexual and vaginal health.

The Checklist in Context: Using the 5 A's Model

The benefits of identifying sexual health problems can only be realized if clinicians have a clear plan for both initiating the conversation and delivering appropriate resources and recommendations for follow-up care in a manner that is both efficient for physicians and clear for patients. The 5A's model (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist and Arrange Follow-up) for communication is a useful outline for communication about sexual health in medical settings that extends the well-known PLISSIT model [11, 24].

Specific elements of the 5 A's model

Ask

The very nature of ‘asking’ signals validation. It can be helpful start with a simply statement such as “Many women who have gone through similar cancer treatment notice changes in sexual function or vaginal health.”

Advise

A brief but important opportunity to advise women that problems can be addressed. For example, “Fortunately there are lots of resources for women with your concerns.”

Assess

Using the Checklist found in Figure 1, providers can gain a brief overview of current concerns. Of note, the Checklist begins by asking women about vaginal health, as well as sexual health, clinicians can both decrease the stigma associated with sexual dysfunction and signal the importance of self-care regardless of current sexual activity or partner status. Vaginal health has implications for overall well being, as well as compliance with further gynecologic screening [25], making it a vital topic for all women.

Assist

By providing patients with education, information and resources, patients not only become more knowledgeable, but also feel more competent [26]. Many patients benefit from educational or simple interventions only [27]; however, it is also imperative to have additional referral sources for counseling, pelvic physical therapy, urogynecological consult, etc. Collaborative relationships either within one's institution or within a community-based setting should be cultivated. Common strategies clinicians should be familiar with when providing Assistance are explained below.

Arrange Follow-up

This last step serves as a reminder to clinicians to both arrange follow-up for identified problems and to follow up by initiating inquiry at the next visit.

Assistance: Review of Common Problems and How to Help

Although the first item on the checklist addresses low desire, desire is a multi-factorial experience influenced by physical, psychological, and contextual elements. Because the experience of desire can be directly influenced by all of the other items on the checklist, we will address it at the end of this section.

Decreased sensation

When a woman endorses this symptom, it is imperative to query what kind of sensation she is referencing. Loss of sensation can include both genital sensation experienced during sexual activity as well as other types of diminished sensation caused by surgery, chemotherapy-related neuropathy, or possible lower extremity lymphedema. With regard to genital sensation, surgical intervention in the pelvic region for bladder, colorectal, and gynecological cancers can result in nerve damage that diminishes sensation. Lower extremity lymphedema can also cause swelling in the genital area that can also diminish sensation. Pelvic radiation can damage blood vessels and alter the density of nerve fibers in the vulva and vagina, which similarly can negatively impact sensation. If a patient endorses decreased sensation, strategies that help to facilitate arousal by drawing blood flow and promoting circulation in the pelvic area may be helpful [28,29]. Examples include pelvic floor exercises, self-stimulation, vibrators, and vacuum devices. A clitoral vacuum device has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of female arousal disorders, which includes diminished sensation. The vacuum device is applied over the clitoral area to pull blood flow to the pelvis, thereby promoting engorgement [30], and it has proven beneficial for cancer patients who have undergone radiation therapy [30,31], with possible rehabilitative effects to the tissues [31]. Use of a vibrator and/or self-stimulation may be as effective, because these options similarly promote oxygenated blood flow to the pelvic floor through sexual arousal [32]. Educational resources on pelvic floor exercises or a referral to a sexual health expert to discuss these strategies is recommended.

Another type of loss of sensation impacting sexual health is loss of nipple/breast sensation after breast surgery. After mastectomy, breast sensation may be profoundly altered, if not absent entirely [33, *34,35]. To the extent that breasts are an important component of a woman's arousal or a couple's prior “sexual script” [36], this may be a significantly distressing side effect of treatment. Partners may inadvertently magnify the problem by avoiding or overemphasizing the surgically altered breast. Women and partners may need to adjust to complicated feelings of loss and learn to create new sexual routines. Although many women and couples will resolve these concerns without professional guidance, others may benefit from a counseling referral to more effectively resolve sexual concerns.

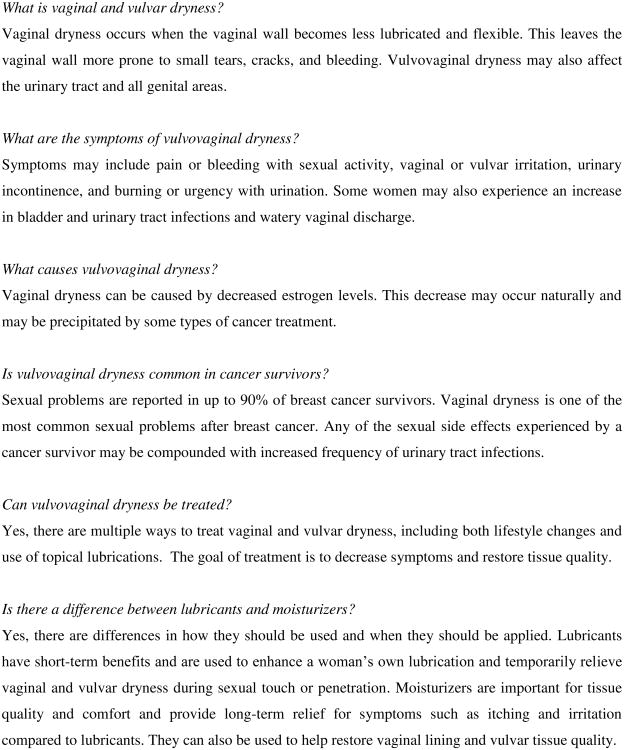

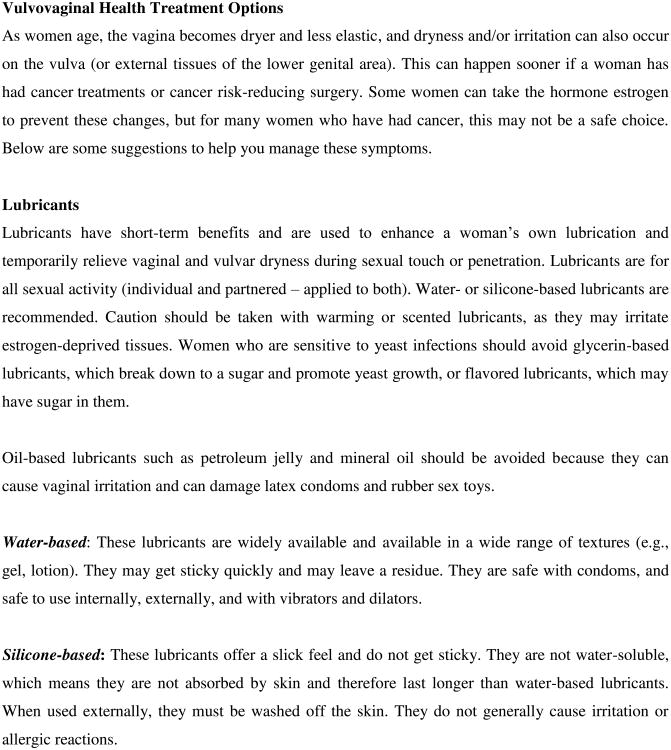

Decreased lubrication (dryness)

Vaginal dryness is one of the most common and distressing problems for female cancer survivors [25]. Surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy all have the capacity to cause estrogen deprivation and decrease genital blood flow, resulting in loss of vaginal lubrication and consequently loss of genital tissue elasticity. Vaginal dryness is often accompanied with burning, itching, or chafing. Female cancer patients/survivors need to be educated about how moisturizers and lubricants as well as the maintenance of sexual activity can be useful adjuncts in managing vaginal dryness and dyspareunia [37,38]. It is important to explain the benefits of non-hormonal vaginal moisturizers [39-41] and how intravaginal moisturizers (e.g., Polycarbophil) used once or twice weekly can be helpful in maintaining pH balance in addition to adding moisture [42]. Use of water-based or silicone-based lubricants should be encouraged during sexual activity. Recommendations for water-based lubricants with minimal additives, such as Good Clean Love: Almost Naked®, Astroglide®, KY Jelly®, or Slippery Stuff®, can be given. Patients should be advised to avoid additives like paraben, glycerin, propylene glycol, fragrance, bactericide and spermicide, as these may be irritating or caustic to the menopausal vaginal and vulvar epithelium, and opt for dye-free options instead. For women who are vulnerable to yeast infections, glycerin in glycerin-based lubricants can act like a sugar and promote yeast infections. A thorough presentation of vaginal health strategies can be found in a review by Carter and colleagues [25].

In addition, local vaginal estrogen (cream, ring, or tablet form) is a particularly effective but controversial treatment for vaginal dryness. Although acceptance of these products has gained popularity because there is minimal systemic absorption, long-term safety trials on the use of local estrogens in cancer patients, especially those with hormonally sensitive tumors, are lacking [43]. There is controversy regarding the minimal escape of estrogen into the systemic circulation and the clinical significance, if any, of this action [44]. Detailed risk-benefit discussions must occur between the patient and her medical team and should be appropriately documented in the medical record. A novel potential treatment for vaginal dryness is ospemiphene, a non-estrogen agonist/antagonist that increases vaginal lubrication; in addition, it has shown to improve many of the sexual domains in the FSFI. However, safety trials in cancer survivors are once again lacking.

Difficulty reaching orgasm

Often women experience difficulty with reaching orgasm or detrimental changes in arousal after undergoing treatment-related menopausal symptoms [25], yet these symptoms are often not discussed with clinicians. Although post-menopausal women typically need increased stimulation to reach orgasm, vaginal dryness can also make stimulation uncomfortable or painful, thus resulting in failure to reach climax. Women may find it helpful to use sexual aids such as vibrators in order to support oxygenated genital blood flow and enhance the experience of genital stimulation and arousal. Women should be educated on the use of lubricants with sexual aids. For example, they should be aware that silicone-based lubricants can compromise the material integrity of silicone vibrators

Pain during Sex

One of the most common reasons female cancer survivors experience pain with sexual activity is because cancer treatments often result in vaginal atrophy, which refers to a compromised lack of vaginal moisture, blood flow, and tissue elasticity [37, 38]. To address atrophy-related pain, these elements need to be restored [45,46]. Beyond replacing vaginal moisture, women with atrophy need to restore elasticity to the vaginal tissue. One approach is to have women employ a systematic regimen of using vaginal dilators, a set of tapered devices that vary in size, and facilitate mechanical stretch of vaginal tissue. Sex may also be painful for women who experience vaginal narrowing from pelvic radiation or foreshortening from surgical intervention. For these women, consistent dilator programs may also be helpful. Alternative sexual positioning and liberal use of pillows may also ease pain and discomfort. For women who experience severe foreshortening of the vaginal canal as a result of surgery or radiation, pain during penetrative intercourse may be due to ‘collision dyspareunia’. A promising option available in the United Kingdom is the Come Close® Ring, a cushioned ring placed at the base of the penis that serves as a spacer and precludes deep thrusting and circumvent collision.

A recent, small randomized controlled trial explored the use of a numbing agent (i.e., aqueous lidocaine) to reduce vulvar and vestibular tenderness in breast cancer patients experiencing dyspareunia. The results demonstrated that women who applied lidocaine to the vulvar and vestibular tissues prior to insertion experienced improved comfort and less distress with intercourse [47]. However, in this sample, only 28% of the women had ever used a moisturizer to address these issues.

Addressing pain during sexual activity is important, because if not addressed, female cancer survivors may begin to anticipate painful intercourse and thereby develop secondary vaginismus, an involuntary and habitual clenching of pelvic floor muscles. In this case, women need to become educated about their pelvic floor, including how to relax pelvic floor muscles that are chronically over-engaged. One of the benefits of dilator therapy is that women can also use this exercise to practice relaxing the pelvic floor during penetration and regain a sense of control with their body. Prompt intervention for women with sexual concerns is important so as to avoid other concomitant problems such as secondary vaginismus.

Vaginal or vulvar pain (not during sex)

Female cancer survivors may have vaginal discomfort or vulvar pain as a consequence of various treatments, including hormone blocking endocrine therapy, pelvic radiation, and vaginal graft versus host disease (GVHD) following allogenic bone marrow transplant (BMT). To address vulvar burning, itching, or chafing accompanying vaginal atrophy or as a result of radiation, women should be taught to moisturize the vulva and vagina.

Up to half of women who undergo allogenic BMT suffer from vaginal GVHD and experience burning, dryness, itching, or pain to the touch (tenderness) [48]. Upon examination, a clinician may notice ulcerated or thickened skin of the vulva or vagina, and narrowing and scarring of the vaginal entry. Typically, treatment of GVHD consists of a combination of immunosuppressants/corticosteroids and topical estrogen to treat vulvar pain [48-51]. Treatments for genital GVHD are quite successful and can lead to decreased vulvar pain in less than 2 months when administered early [49]. Ideally, women should be referred to a GYN specialist who has experience working with cancer survivors. Of note some women may have other pre-existing issues of pain, such as vulvar vestibulitis, which would require a more comprehensive evaluation with a sexual pain specialist.

Anxiety about sex

There are many reasons women might endorse this item, including not having been sexually active since treatment or worrying whether or not resuming sexual activity is even possible [52]. Potential sources of anxiety may include a history of body alterations, surgical scars, and surgical reconstructions that affect perceived attractiveness [53], as well as related challenges such as prostheses and ostomies [54]. Young women who undergo treatment-induced menopause are often anxious about sexual side effects [*55], as are some women who undergo preventive cancer risk-reducing surgery, such as BRCA mutation carriers who undergo prophylactic mastectomy and/or oophorectomy [*56]. This item is intended to help clinicians identify patients/survivors who are experiencing anxiety or distress and need resources or further support. It is not necessarily the role of the inquiring clinician to reduce women's anxiety but rather to identify that sexual function is a source of worry and to then guide them toward appropriate resources for counseling and/or psychopharmacological consultation.

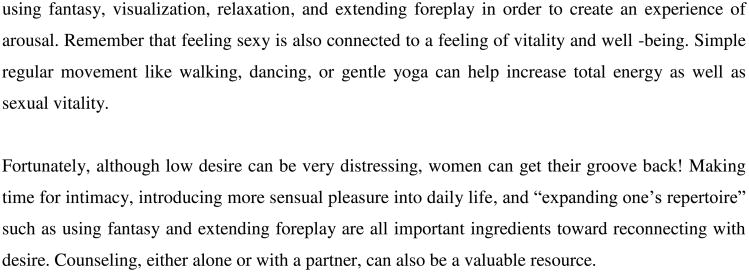

Low desire: Sexual desire is a biopsychosocial phenomenon with interrelated physical, hormonal, emotional, and relationship factors. Lack of desire is the most common complaint with regard to sexual health among women [57-61]. When women have post-treatment sexual activity that is uncomfortable or painful, it is not uncommon to find loss of desire as the initial presenting problem. For this reason, it is important to identify associated physical factors such vaginal dryness, vulvar discomfort and pain with sexual activity, on the checklist. Significant alterations in hormones (estrogen, progesterone, testosterone) can further contribute to loss of desire in addition to causing changes in vaginal health. Medical comorbidities can also negatively affect libido, as can various medications, including opiates, anticonvulsants, beta and calcium channel blockers, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [62]. For example, women with decreased desire who are taking antidepressants and/or anti-anxiolytics may need to be referred to a psychiatrist for consultation regarding medications with fewer sexual side effects. Partner and relationship factors should be acknowledged, although they are often not considered in clinical inquiry. Often, couples struggle with a lack of sexual communication and uncertainty about how to restart intimacy after cancer [63]. Both couple and individual counseling can be helpful [64]. For example, counseling can help women shift their focus toward enhancement of sensual pleasure by learning to use guided meditation and muscle relaxation, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and fantasy. A recent mindfulness intervention was shown to improve perception of arousal, despite no physical enhancement of engorgement, demonstrating the power of the mind-body connection to adapt and overcome physical impairments [65]. Women with arousal issues should be encouraged to explore exercises and strategies that address both the mental [66] and physical [67,68] aspects of the problem. Most recently, in August 2015, the US FDA approved Addyi™ (flibanserin 100 mg), a non-hormonal pill (developed as an antidepressant - 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT2A antagonist), for the treatment of acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women [69]. It should be noted that flibaserin has only been approved for premenopausal women and has not been studied in cancer populations.

Assisting with Resources

We suggest two categories of resources for clinicians to complement their clinical inquiry of sexual concerns in their female cancer patients. First, clinicians need robust referral networks, which would ideally include a gynecologist who has experience working with female cancer survivors, a counselor or therapist, a pelvic floor physical therapist and potentially a psychiatrist, a reproductive endocrinologist, and/or a specialist in urogynecology. It is possible to expand one's network from within an institution or reach out to community-based clinicians outside of one's home center who have an interest in working collaboratively. Furthermore, there are several professional organizations that can facilitate this process by allowing clinicians to identify professionals by location and areas of expertise, such as the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (http://www.isswsh.org), The North American Menopause Society (http://www.menopause.org), the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists (http://www.aasect.org) and the Society for Sex Therapy and Research (http://www.starnet.org). Secondly, clinicians need material resources to give to patients. Fortunately for clinicians who want to help patients/survivors, there is now a growing body of high-quality resources regarding sexual health and cancer that are easily accessible electronically, as well as in hard copy. Both the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute have comprehensive information about sex after cancer, e.g., “Sexuality and Cancer: For the woman who has cancer and her partner” (http://www.cancer.org) and “Sexuality and reproductive issues” (http://www.cancer.org). Comprehensive resources also include websites from abroad, including the MacMillan Cancer Support Community in the UK (http://www.macmillan.org.uk) and the Cancer Council of Australia (www.cancercouncil.com.au). A new international organization called the Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer has a website (http://cancersexnetwork.org/) that also overviews a range of resources in this area. Figures 2-4 include teaching sheets, or “tip sheets,” which give information about the specific topics of vaginal dryness and low desire and can be given to patients directly (Figures 2-4).

Figure 2. Vulvovaginal Dryness Information Sheet.

Figure 4. Patient Education Handout - Loss of Desire after Cancer Treatment.

Conclusion

Sexual health is a fundamental element of quality of life that patients and survivors struggle with throughout the cancer care continuum. Patients often want to discuss these issues, but clinicians face a range of barriers in addressing these concerns, including limited time, training, and experience in communicating and treating these problems. This review can provide clinicians with a straightforward plan regarding how to approach this topic, including having a framework and checklist to guide clinical inquiry, as well as readily available resources. Along with a relevant referral network, these tools can serve to reduce barriers and facilitate conversations about sexual health. Moreover, when patient experience is validated and patients are offered information in a way that allows them to feel a greater sense of competence to manage their own health, they may be more likely to follow through with intervention and to ultimately achieve a greater sense of overall well-being. Although there is an ongoing need for future research to develop a broader evidence base for state-of-the-art sexual health interventions, there are more resources available now than ever before. For the millions of cancer survivors who are left struggling with quality-of-life issues such as sexual dysfunction, it is imperative that we move toward systematic assessment and routine delivery of sexual health intervention as part of survivorship care.

Figure 3. Vulvovaginal Health.

Key points.

Providers need practical strategies and material resources to help foster clinical inquiry about sexual health

Women need to be queried about vaginal health as well as sexual health, regardless of age, partner status, or recent sexual activity

Providers can inquire about vaginal/sexual health with a brief checklist in order to facilitate communication about patient needs

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank fellow members of the Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer for their guidance and support of this project (cancersexnetwork.org).

Financial support and sponsorship: None

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Authors have no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Juraskova I, Butow P, Robertson R, et al. Post-treatment sexual adjustment following cervical and endometrial cancer: a qualitative insight. Psychooncology. 2003;12:267–79. doi: 10.1002/pon.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz A. The sounds of silence: sexuality information for cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:238–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landmark BT, 1, Bøhler A, Loberg K, Wahl AK. Women with newly diagnosed breast cancer and their perceptions of needs in a health-care context. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(7B):192–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5*.Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, et al. Talking about sex after cancer: a discourse analytic study of health care professional accounts of sexual communication with patients. Psychol Health. 2013;28:1370–90. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.811242. This article highlights challenges in sexual communication between patients and health care providers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, Abernethy AP, Lin L, Shelby RA, Porter LS, Dombeck CB, Weinfurt KP. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21:594–601. doi: 10.1002/pon.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hordern AJ, Street AF. Let's talk about sex: risky business for cancer and palliative care clinicians. Contemp Nurse. 2007;27:49–60. doi: 10.5555/conu.2007.27.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hordern AJ, Street AF. Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust. 2007;186:224–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, et al. Caring for cancer survivors: a survey of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4409–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiggins DL, Wood R, Granai CO, Dizon DS. Sex, intimacy, and the gynecologic oncologists: survey results of the New England Association of Gynecologic Oncologists (NEAGO) J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25:61–70. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL. Sexual health communication during cancer care: barriers and recommendations. Cancer J. 2009;15:74–7. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819587dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stead ML, Brown JM, Fallowfield L, Selby P. Lack of communication between healthcare professionals and women with ovarian cancer about sexual issues. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:666–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isidori AM, Pozza C, Esposito K, et al. Development and validation of a 6-item version of the female sexual function index (FSFI) as a diagnostic tool for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1139–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hordern AJ, Street AF. Constructions of sexuality and intimacy after cancer: patient and health professional perspectives. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1704–18. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ananth H, 1, Jones L, King M, Tookman A. The impact of cancer on sexual function: a controlled study. Palliat Med. 2003;17:202–5. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm759oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J. Embodying sexual subjectivity after cancer: a qualitative study of people with cancer and intimate partners. Psychol Health. 2013;28:603–19. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2012.737466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai YF. Nurses' facilitators and barriers for taking a sexual history in Taiwan. Appl Nurs Res. 2004;17(4):257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi JC, Syrjala KL. Sexuality after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer J. 2009;15:57–64. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318198c758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Jeffery DD, Barbera L, Andersen BL, et al. Self-Reported Sexual Function Measures Administered to Female Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review, 2008-2014. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2015;33:433–66. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2015.1046012. This article is a timely and comprehensive review of sexual function measures that have been used with female cancer patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flynn KE, Lin L, Cyranowski JM, et al. Development of the NIH PROMIS ® Sexual Function and Satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. J Sex Med. 2013;10(1):43–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Broderick G, et al. Clinical evaluation and management strategy for sexual dysfunction in men and women. J Sex Med. 2004;1:49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldfarb SB, Abramsohn E, Andersen BL, et al. A national network to advance the field of cancer and female sexuality. J Sex Med. 2013;10:319–25. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annon JS. The PLISSIT model: A proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioral treatment of sexual problems. A J Sex Educ Ther. 1976;2:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter J, Goldfrank D, Schover LR. Simple strategies for vaginal health promotion in cancer survivors. J Sex Med. 2011;8:549–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory in health care and its relations to motivational interviewing: a few comments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbera L, Fitch M, Adams L, et al. Improving care for women after gynecological cancer: the development of a sexuality clinic. Menopause. 2011;18:1327–33. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821f598c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowenstein L, Gruenwald I, Gartman I, Vardi Y. Can stronger pelvic muscle floor improve sexual function? Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:553–6. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billups KL, Berman L, Berman J, et al. A new non-pharmacological vacuum therapy for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:435–41. doi: 10.1080/713846826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroder M, Mell LK, Hurteau JA, et al. Clitoral therapy device for treatment of sexual dysfunction in irradiated cervical cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1078–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schover LR. Sexuality and fertility after cancer. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:523–7. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gahm J, Hansson P, Brandberg Y, Wickman M. Breast sensibility after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:1521–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.Peled AW, Duralde E, Foster RD, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and satisfaction after total skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate expander-implant reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(1):S48–52. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000020. This article highlights patient-reported outcomes after mastectomy and reconstruction including negative impact on sexual function. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shridharani SM, Magarakis M, Stapleton SM, et al. Breast sensation after breast reconstruction: a systematic review. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2010;26:303–10. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gagnon JH, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Cognitive and social aspects of sexual dysfunction: sexual scripts in sex therapy. J Sex Marital Ther. 1982;8:44–56. doi: 10.1080/00926238208405811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women's Health Care Physicians. Sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4 Suppl):85S–91S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000138796.21369.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. SOGC clinical practice guidelines. The detection and management of vaginal atrophy. Number 145, May 2004. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88:222–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J, Geng L, Song X, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid vaginal gel to ease vaginal dryness: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel-group, clinical trial. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1575–84. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costantino D, Guaraldi C. Effectiveness and safety of vaginal suppositories for the treatment of the vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: an open, non-controlled clinical trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2008;12:411–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ekin M, Yaşar L, Savan K, Temur M, Uhri M, Gencer I, Kıvanç E. The comparison of hyaluronic acid vaginal tablets with estradiol vaginal tablets in the treatment of atrophic vaginitis: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:539–43. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Laak JA, de Bie LM, de Leeuw H, et al. The effect of Replens on vaginal cytology in the treatment of postmenopausal atrophy: cytomorphology versus computerised cytometry. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:446–51. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.6.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Clinical Trial. Serum estradiol levels in post menopausal women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors and vaginal estrogen. [Accessed September 26, 2010];2009 NCT00984300. Available at: http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

- 44.Missmer SA, Eliassen AH, Barbieri RL, Hankinson SE. Endogenous estrogen, androgen, and progesterone concentrations and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1856–65. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kingsberg S, Kellogg S, Krychman M. Treating dyspareunia caused by vaginal atrophy: a review of treatment options using vaginal estrogen therapy. Int J Womens Health. 2010;1:105–11. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pruthi S, Simon JA, Early AP. Current overview of the management of urogenital atrophy in women with breast cancer. Breast J. 2011;17:403–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goetsch MF, Lim JY, Caughey ABA. Practical Solution for Dyspareunia in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jul 27; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.7366. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stratton P, Turner ML, Childs R, et al. Vulvovaginal chronic graft-versus-host disease with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1041–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000285998.75450.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shanis D, Merideth M, Pulanic TK, et al. Female long-term survivors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: evaluation and management. Semin Hematol. 2012;49:83–93. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spinelli S, Chiodi S, Costantini S, et al. Female genital tract graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Haematologica. 2003;88:1163–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zantomio D, Grigg AP, MacGregor L, et al. Female genital tract graft-versus-host disease: incidence, risk factors and recommendations for management. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:567–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bradford A, Nebgen D, Keeler E, Milbourne A. A comprehensive program to meet the sexual health needs of women with cancer. Seventh Biennial Cancer Survivorship Research Conference; Atlanta, GA. June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elder EE, Brandberg Y, Björklund T, et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction in breast cancer patients after immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective study. Breast. 2005;14:201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manderson L. Boundary breaches: the body, sex and sexuality after stoma surgery. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:405–15. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55*.Rosenberg SM, Tamimi RM, Gelber S, et al. Treatment-related amenorrhea and sexual functioning in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2014;120:2264–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28738. This article provides key insights into the relationship between treatment-induced menopause and sexual function in breast cancer survivors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56*.Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Bakan J, et al. Addressing sexual dysfunction after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy: effects of a brief, psychosexual intervention. J Sex Med. 2015;12:189–97. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12713. This study demonstrates the positive results of a novel psychosexual intervention for young women who undergo risk-reducing oopherectomy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Neves RC, Moreira ED, Jr GSSAB Investigators' Group. A population-based survey of sexual activity, sexual problems and associated help-seeking behavior patterns in mature adults in the United States of America. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21:171–8. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2009.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simons JS, Carey MP. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions: results from a decade of research. Arch Sex Behav. 2001;30:177–219. doi: 10.1023/a:1002729318254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moreira ED, Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al. GSSAB Investigators' Group. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181898cdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;23:762–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Segraves RT, Balon R. Sexual Pharmacology: Fast Facts. New York: WW Norton; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scott JL, Kayser K. A review of couple-based interventions for enhancing women's sexual adjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer J. 2009;15:48–56. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819585df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.MacPhee DC, Johnson SM, Van der Veer MM. Low sexual desire in women: the effects of marital therapy. J Sex Marital Ther. 1995;21:159–82. doi: 10.1080/00926239508404396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brotto LA, Erskine Y, Carey M, et al. A brief mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral intervention improves sexual functioning versus wait-list control in women treated for gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:320–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frühauf S, Gerger H, Schmidt HM, et al. Efficacy of psychological interventions for sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:915–33. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davis SR, Braunstein GD. Efficacy and safety of testosterone in the management of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1134–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heiman JR. Treating low sexual desire - new findings for testosterone in women. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2047–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0807808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Food and Drug Administration Joint Meeting of Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee. Flbanserin for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. NDA 022526. Advisory Committee Briefing Document. 2015 [Google Scholar]