ABSTRACT

E4orf6 proteins from all human adenoviruses form Cullin-based ubiquitin ligase complexes that, in association with E1B55K, target cellular proteins for degradation. While most are assembled with Cul5, a few utilize Cul2. BC-box motifs enable all these E4orf6 proteins to assemble ligase complexes with Elongins B and C. We also identified a Cul2-box motif used for Cul2 selection in all Cul2-based complexes. With this information, we set out to determine if other adenoviruses also possess the ability to form the ligase complex and, if so, to predict their Cullin usage. Here we report that all adenoviruses known to encode an E4orf6-like protein (mastadenoviruses and atadenoviruses) maintain the potential to form the ligase complex. We could accurately predict Cullin usage for E4orf6 products of mastadenoviruses and all but one atadenovirus. Interestingly, in nonhuman primate adenoviruses, we found a clear segregation of Cullin binding, with Cul5 utilized by viruses infecting great apes and Cul2 by Old/New World monkey viruses, suggesting that a switch from Cul2 to Cul5 binding occurred during the period when great apes diverged from monkeys. Based on the analysis of Cullin selection, we also suggest that the majority of human adenoviruses, which exhibit a broader tropism for the eye and the respiratory tract, exhibit Cul5 specificity and resemble viruses infecting great apes, whereas those that infect the gastrointestinal tract may have originated from monkey viruses that share Cul2 specificity. Finally, aviadenoviruses also appear to contain E4orf6 genes that encode proteins with a conserved XCXC motif followed by, in most cases, a BC-box motif.

IMPORTANCE Two early adenoviral proteins, E4orf6 and E1B55K, form a ubiquitin ligase complex with cellular proteins to ubiquitinate specific substrates, leading to their degradation by the proteasome. In studies with representatives of each human adenovirus species, we (and others) previously discovered that some viruses use Cul2 to form the complex, while others use Cul5. In the present study, we expanded our analyses to all sequenced adenoviruses and found that E4orf6 genes from all mast- and atadenoviruses encode proteins containing the motifs necessary to form the ligase complex. We found a clear separation in Cullin specificity between adenoviruses of great apes and Old/New World monkeys, lending support for a monkey origin for human viruses of the Human mastadenovirus A, F, and G species. We also identified previously unrecognized E4orf6 genes in the aviadenoviruses that encode proteins containing motifs permitting formation of the ubiquitin ligase.

INTRODUCTION

Adenoviruses (AdVs) are a large group of double-stranded DNA viruses possessing nonenveloped icosahedral capsids of around 90 nm in diameter. Based on genome structures of individual AdVs isolated from or detected in a very wide range of animal species, AdVs have been divided into the following 5 genera: Mastadenovirus, Aviadenovirus, Atadenovirus, Siadenovirus, and Ichtadenovirus (1–3). The human adenovirus (HAdV) members of the genus Mastadenovirus have been the most studied, in part because of their known risk to human health and also because of the finding that they seem to possess oncogenic potential (reviewed in reference 4). Infection by adenoviruses can cause several conditions, including respiratory diseases, conjunctivitis, gastroenteritis, and in some cases death, depending on the species. The HAdVs have been divided into 7 species (Human mastadenovirus A to Human mastadenovirus G [HAdV-A to -G]), with species HAdV-A, -F, and -G often infecting the gastrointestinal tract (5–8).

Among the early products of HAdVs are those encoded by early region 4 (E4), which produces multiple proteins through extensive mRNA splicing. The E4orf6 protein has been of considerable interest since the 1980s, when for human adenovirus type 5 (HAdV-5), one of the most-studied human serotypes, it was shown that E4orf6 in cooperation with the viral E1B55K product reduced levels of the p53 tumor suppressor (9–13). We later demonstrated that reduction of p53 protein levels resulted from p53 degradation via the proteasome through the action of a Cullin-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex formed by the E4orf6 protein and also containing E1B55K (14). Subsequently, we and others demonstrated that additional, perhaps many, substrates exist to optimize viral replication (15–21). The E4orf6 gene can be found in all mastadenoviruses, and two closely related genes can be found in all atadenoviruses (22, 23). In both of these genera, the E1B55K gene or a gene related to E1B55K (LH3) can also be found (24). Interestingly, E1A is found only in the mastadenoviruses (see more in Discussion).

Cullin-based ubiquitin ligases are a class of ligases in which a Cullin moiety acts as a scaffold to bring the E2 enzyme in close proximity to a substrate to be ubiquitinated, leading to its proteasome-mediated degradation. In the best-known complexes, the SCF complexes, the substrate recognition proteins, also termed F-box proteins, bind through their F-box motifs to the linker protein SKP1, which is associated with Cul1 (25–27). By changing the F-box protein, these complexes can target several proteins for degradation, most of which are involved in regulation of the cell cycle. Complexes assembled with either Cul2 or Cul5 utilize the same linker proteins, Elongins B and C, and the substrate recognition proteins contain a BC-box motif to bind to the linker (28, 29). The substrate recognition proteins also contain an additional motif to specify which Cullin will be selected. These motifs are termed Cul2 and Cul5 boxes (28–30).

In our studies on HAdV-5 (HAdV-C), we showed that the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex assembled by E4orf6 and E1B55K (14) requires the presence in E4orf6 of a BC box (in fact, it contains three) (31, 32) that enables complex formation with the cellular proteins Cul5, Elongins B and C, and RBX1 before binding to E1B55K, which functions as the major substrate recognition protein (31, 32). Formation of this ligase complex was shown to be an important function of E4orf6 during infection, as a BC-box mutant unable to form the complex exhibited the same defective phenotype as that of a mutant lacking E4orf6 entirely (33). We found that the ability to assemble the ligase complex is conserved within all HAdV species (34, 35) but that there are differences in the identities of substrates among species. In addition, we and others found that E4orf6 from members of HAdV-A, -F, and most probably -G assemble ligase complexes with Cul2 rather than Cul5 (34, 36). The basis for the different Cullin usage is not yet known, but it may be linked to the fact that HAdV-A, -F, and -G members exhibit considerable tropism for the gastrointestinal tract, whereas members of the other species generally infect the respiratory tract and the eye.

The Cul5 box in cellular proteins that links Cul5 to the ligase complex has been defined as ΦXXLPΦPXXΦXX(Y/F)(L/I), with the LPΦP part appearing to have the most critical role in the interaction (29, 30). However, no such Cul5 box was found in HAdV-5 or in any human adenovirus E4orf6 protein that binds Cul5. In the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Vif protein, which also assembles a Cul5-based ubiquitin ligase, a zinc finger was found to be important for binding Cul5 (37). This motif is also lacking in Cul5-binding E4orf6 proteins. To date, the Cul5 box in E4orf6 remains unidentified. We have identified from studies on HAdV-5/HAdV-12 hybrid E4orf6 proteins that regions involved in binding of both Cul2 and Cul5 are found in the second quarter of the protein. More success was obtained in our search for a Cul2 box. Such a motif was identified in HAdV-12 E4orf6 that matched the cellular protein consensus motif ΦXXXΦXXXΦ (30, 38). When this motif was altered through mutagenesis, E4orf6 lost the ability to bind Cul2 (38). Furthermore, when this motif was created in HAdV-5 E4orf6 at the equivalent position, binding to Cul2 was observed (38).

All our studies on the adenoviral ubiquitin ligase have so far been limited to HAdVs. It was thus of interest to determine if the ability to assemble the ubiquitin ligase is conserved evolutionarily in all adenoviruses or if this function is a feature specific to HAdVs. Further, it occurred to us that if ligase formation is a general function of all adenoviruses, we might utilize our knowledge of the Cul2-box motif to predict the Cullin specificity of such complexes, and in doing so, we may be able to study the global evolution of all adenoviruses. We report here that the formation of the ubiquitin ligase complex is most likely completely conserved in all adenovirus types containing an E4orf6 gene and that the specificity of the Cullin protein can be predicted in most cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Human non-small-cell lung carcinoma H1299 cells (ATCC CRL-5803) were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Gibco) without antibiotics and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Multicell) at 37°C in 5% CO2. H1299-HA-Cul5 cells were described previously (31), and H1299-HA-Cul2 cells were generated in a similar fashion. Briefly, H1299 cells were transfected with plasmids pcDNA3-HA-Cul2 and pcDNA3-puro at a ratio of 10:1, followed by selection in medium containing 2 μg/ml puromycin. Individual colonies were picked and expanded, and the level of expression of HA-Cul2 was verified by Western blotting using anti-hemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibodies. A high-expression clone was chosen for further experiments. Both stable cell lines were maintained in 1 μg/ml puromycin.

Antibodies.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies used were as follows: actin C4 (Millipore), HA clone 16B12 (Covance), FLAG M2 (Sigma-Aldrich), p53 421 (39), herpes simplex virus (HSV) (69171; Novagen), and Myc 9E10 (Covance) antibodies. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies used were as follows: FLAG M2 (F7425; Sigma), HSV PC267 (Kamiya), eEF2 clone 2332 (Cell Signaling), Nedd8 (2745; Cell Signaling), Cul5 (Bethyl), and Cul2 NBP1-02780 (Novus) antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for detection on Western blots were goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Plasmids and cloning.

Plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged HAdV-5 and HAdV-12 E4orf6 (34), HA-tagged Cul2 and Cul5 (14), HSV-tagged Elongin C (40), mouse p53 (41), and mouse DNA ligase IV have been described previously. The corresponding genes from AdVs belonging to two different genera were studied. Murine AdV-1 (MAdV-1) E4orf6 and E1B55K (a kind gift from Kathy Spindler), tree shrew AdV-1 (TSAdV-1) E4orf6 (a kind gift from Gary Ketner), canine AdV-2 (CAdV-2) E4orf6 from the genus Mastadenovirus (a kind gift from Bernhard Dietzschold), and duck AdV-1 (DAdV-1) E4orf6 proteins and bovine AdV-6 (BAdV-6) E4orf6 proteins from the genus Atadenovirus were cloned by PCR, using the respective viral genomic DNAs as templates. MAdV-1 E4orf6 was cloned by PCR by using the plasmid Z, which contains the entire genomic E4 region, as the template. Sequences encoding the FLAG (E4orf6) and HA (E1B55K) tags were added to the primers. The following primers were used, with the restriction enzymes used for insertion into the pcDNA3 vector indicated in parentheses: for MAdV-1 E4orf6 (BamHI/XhoI), forward primer GATCGGATCCATGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGACTACGACTTTTTGTTTGCTTCC and reverse primer AATCTAGATTAACCCGTAAATAGGTGAGG; for MAdV-1 E1B55K (HindIII/XhoI), forward primer AAAAGCTTATGTACCCATACGACGTCCCAGACTACGCTGAGGACCGTCAAGCTCTCG and reverse primer AATCTAGACTATTCATCATCACTCAATTCC; for TSAdV-1 E4orf6 (EcoRI/XbaI), forward primer ATCGATGAATTCTCATATGAGCAGAACTCCGACTAACAGC and reverse primer ATCGTATCTAGACTATGAGGACAAACGAGGAGCG; for CAdV-2 E4orf6 (BamHI/XhoI), forward primer CCGGATCCATGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGGAAGGCAACTGCACTGC and reverse primer GGCTCGAGCTAAAAATGAAGAAACGCGTTGAGG; for DAdV-1 E4 (BamHI/XhoI), forward primer CCGGATCCATGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGTCCACCAGATCAACCTGC and reverse primer GGCTCGAGTTATTTGAAAGCAAATTCGTAC; for DAdV-1 orf10 (BamHI/XhoI), forward primer CCGGATCCATGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGGCCACAGCGGCGGG and reverse primer GGCTCGAGCTAGGGTACCACAGGAC; for BAdV-6 E4.3 (BamHI/XhoI), forward primer CCGGATCCATGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGTTTGTGAATTCTACTTGTTGTTG and reverse primer GGCTCGAGTTATCTCAATCTATTTTTTAATAAACG; and for BAdV-6 E4.2 (BamHI/XhoI), forward primer CCGGATCCATGGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGGAATTCAATTTGCAACTCATTGC and reverse primer GGCTCGAGTTACAGATGCCAAGAAGAC. Specific mutations in FLAG-tagged MAdV-1 E4orf6 were generated by PCR-based mutagenesis. Incorporated within each primer were additional silent mutations that either added or removed a restriction site close to the mutation. The following primers were used, with restriction enzymes used for screening indicated in parentheses: for the Y70R mutant (+NruI), forward primer CTACTTGAACTCGCGAGATAAGCATGTG and reverse primer CACATGCTTATCTCGCGAGTTCAAGTAG; for the V74K mutant (+HindIII), forward primer CTTATGATAAGCATAAGCTTCAGCAGCTTGACTG and reverse primer CAGTCAAGCTGCTGAAGCTTATGCTTATCATAAG; and for the MAdV-1 L78K-F mutant (none), forward primer GTGCTACAGCAGAAGGACTGTCTGTG and reverse primer CACAGACAGTCCTTCTGCTGTAGCAC. Colonies were screened by restriction enzyme digestion and then sequenced to confirm the incorporation of the mutation. These clones all matched the sequences in GenBank.

Cell transfection and lysis.

Stable cell lines (HA-Cul5 or HA-Cul2) were plated in 10-cm dishes and transfected with plasmid DNAs by using polyethylenimine (PEI) (linear, with a molecular weight of 25,000; Polysciences, Inc.) transfection reagent dissolved in 0.2 N HCl, as suggested previously (42), at 1 μg/μl for 48 h. The medium was changed after 24 h. A ratio of 5 μg of PEI reagent to 1 μg of transfected DNA was used. Due to the various expression levels of the different E4orf6 proteins, different amounts of DNA were used. Also, as HA-Cul2 was not expressed at the same level as HA-Cul5 in the cell lines, plasmid DNA expressing HA-Cul2 was additionally transfected into the HA-Cul2 cell line. However, in each set of E4orf6 transfection studies, the total amount of plasmid DNA transfected (and thus of the PEI reagent) was the same, as empty vector (pcDNA3) was added as required. The amounts of E4orf6-expressing cDNAs transfected were as follows: 0.75 μg HAdV-5, 5.4 μg HAdV-12, 4.0 μg MAdV-1, 0.75 μg TSAdV-1, 5.7 μg CAdV-2, 2.3 μg DAdV-1 E4, 0.8 μg DAdV-1 orf10, 2.2 μg BAdV-6 E4.3, and 8.6 μg BAdV-6 E4.2. The amount of HA-Cul2-expressing cDNA additionally transfected into the HA-Cul2 cell line was 3 μg. H1299 cells were plated in 10-cm dishes for immunoprecipitation and in 6-well plates for degradation assays and were transfected for 24 h with plasmid DNAs by use of Lipofectamine 2000 as described by the manufacturer, at a ratio of 3:1 (Lipofectamine:DNA). DNA amounts were equalized within each experiment by using pcDNA3 empty vector DNA. For degradation assays, the amounts of plasmid DNA used were as follows: 0.35 μg p53, 1.5 μg HA-E1B55K, and 1 μg FLAG-E4orf6. For immunoprecipitation experiments, the following amounts of plasmid DNAs were transfected: 3 to 4 μg for HA-Cul2, 2 μg for HSV-Elongin C, 4 μg for MAdV-1 HA-E1B55K, and 4 μg for myc-mouse DNA ligase IV. Also, the following amounts of DNAs for the various forms of FLAG-E4orf6 were transfected: 9 μg of the MAdV-1 wild type or the Y70R, V74K, or L78K mutant and 4 μg TSAdV-1. Cells were lysed for 20 min on ice in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1% Triton-X, 2 mM NaPP, 400 mM NaF, 100 mM Na3VO4, 0.2 mg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, and 0.7 μg/ml pepstatin A).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

A sample of 300 to 800 μg lysate (consistent within each experiment) was used for immunoprecipitation with 1 μl of appropriate antibody followed by incubation with a 50% slurry of protein A-protein G or with protein G beads for immunoprecipitation from the stable cell lines. Antibody-bound beads were extensively washed in lysis buffer, and immunoprecipitates were eluted in 2× protein sample buffer with 5% β-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were examined by Western blotting essentially as described previously (35). Briefly, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes and blocked using 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 1% Tween (TBST). Membranes were incubated with the indicated primary antibodies in TBST, followed by an appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Polypeptides on membranes were then visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence with ECL Plus Western blot reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Protein alignments and phylogenetic analysis.

Protein sequences were obtained from the NCBI protein database. Most of these are linked at the adenovirus taxonomy website (http://www.vmri.hu/∼harrach/AdVtaxlong.htm). The accession numbers for the adenovirus E4orf6 genes are listed in Table 1. E4orf6 protein sequences were aligned by using Clustal Omega, the alignment data were entered into Topali (43), and model selection was performed. PhyML trees were calculated using the appropriate model, with a bootstrap value of 100, and were visualized by use of Mega6.

TABLE 1.

GenBank accession numbers for adenovirus sequences

| Virus | Accession no. |

|---|---|

| A1139 | JN880448 |

| A1163 | JN880449 |

| A1173 | JN880450 |

| A1258 | JN880451 |

| A1285 | JN880452 |

| A1296 | JN880453 |

| A1312 | JN880454 |

| A1327 | JN880455 |

| A1335 | JN880456 |

| Baboon adenovirus 1 | KC693021 |

| Baboon adenovirus 2 | KC693022 |

| Baboon adenovirus 3 | KC693023 |

| Bat adenovirus 2 | JN252129 |

| Bat adenovirus 3 | GU226970 |

| Bovine adenovirus 1 | BD269513 |

| Bovine adenovirus 2 | AC_000001 |

| Bovine adenovirus 3 | AF030154 |

| Bovine adenovirus 4 | AF036092 |

| Bovine adenovirus 6 | JQ345700 |

| Bovine adenovirus 7a | |

| Bovine adenovirus 8a | |

| Bovine adenovirus 10 | AF027599 |

| California sea lion adenovirus 1 | KJ563221 |

| Canine adenovirus 1 | CAU55001 |

| Canine adenovirus 2 | U77082 |

| Chimp Ad3 | CS138463 |

| Chimp Ad6 | CS138464 |

| Chimp seq13 | HH760489 |

| Chimp seq62 | HH760538 |

| Chimp seq63 | HH760539 |

| Chimp seq65 | HH760541 |

| Chimp Y25 | JN254802 |

| Duck adenovirus 1 | AC_000004 |

| Duck adenovirus 2 | KJ469653 |

| Fowl adenovirus 1 | AC_000014 |

| Fowl adenovirus 2 | KT862806 |

| Fowl adenovirus 4 | GU188428 |

| Fowl adenovirus 5 | KC493646 |

| Fowl adenovirus 8 | KT862810 |

| Fowl adenovirus 9 | AC_000013 |

| Fowl adenovirus 10 | DQ208710 |

| Equine adenovirus 1 | JN418926 |

| Goose adenovirus 4 | JF510462 |

| Human adenovirus 1 | AF534906 |

| Human adenovirus 2 | J01917 |

| Human adenovirus 3 | DQ086466 |

| Human adenovirus 4 | AY487947 |

| Human adenovirus 5 | M73260 |

| Human adenovirus 6 | HC492785 |

| Human adenovirus 7 | AY495969 |

| Human adenovirus 8 | AB448767 |

| Human adenovirus 9 | AJ854486 |

| Human adenovirus 10 | JN226746 |

| Human adenovirus 11 | AY163756 |

| Human adenovirus 12 | X73487 |

| Human adenovirus 13 | JN226747 |

| Human adenovirus 14 | AY803294 |

| Human adenovirus 15 | AB562586 |

| Human adenovirus 16 | AY601636 |

| Human adenovirus 17 | AF108105 |

| Human adenovirus 18 | GU191019 |

| Human adenovirus 19 | JQ326209 |

| Human adenovirus 20 | JN226749 |

| Human adenovirus 21 | AY601633 |

| Human adenovirus 22 | FJ404771 |

| Human adenovirus 23 | JN226750 |

| Human adenovirus 24 | JN226751 |

| Human adenovirus 25 | JN226752 |

| Human adenovirus 26 | EF153474 |

| Human adenovirus 27 | JN226753 |

| Human adenovirus 28 | FJ824826 |

| Human adenovirus 29 | JN226754 |

| Human adenovirus 30 | JN226755 |

| Human adenovirus 31 | AM749299 |

| Human adenovirus 32 | JN226756 |

| Human adenovirus 33 | JN226758 |

| Human adenovirus 34 | AY737797 |

| Human adenovirus 35 | AY271307 |

| Human adenovirus 36 | GQ384080 |

| Human adenovirus 37 | DQ900900 |

| Human adenovirus 38 | JN226759 |

| Human adenovirus 39 | JN226760 |

| Human adenovirus 40 | L19443 |

| Human adenovirus 41 | DQ315364 |

| Human adenovirus 42 | JN226761 |

| Human adenovirus 43 | JN226762 |

| Human adenovirus 44 | JN226763 |

| Human adenovirus 45 | JN226764 |

| Human adenovirus 46 | AY875648 |

| Human adenovirus 47 | JN226757 |

| Human adenovirus 48 | EF153473 |

| Human adenovirus 49 | DQ393829 |

| Human adenovirus 50 | AY737798 |

| Human adenovirus 51 | JN226765 |

| Human adenovirus 52 | DQ923122 |

| Lizard adenovirus 1a | |

| Lizard adenovirus 2 | KJ156523 |

| Murine adenovirus 1 | AC_000012 |

| Murine adenovirus 2 | HM049560 |

| Murine adenovirus 3 | EU835513 |

| Ovine adenovirus 7 | U40839 |

| Pigeon adenovirus 1 | FN824512 |

| Porcine adenovirus 3 | AB026117 |

| Porcine adenovirus 4a | |

| Porcine adenovirus 5 | AF289262 |

| Psittacine adenovirus 3 | KJ675568 |

| Rhesus 23336 | KM190146 |

| Rhesus 51 | KM591901 |

| Rhesus 52 | KM591902 |

| Rhesus 53 | KM591903 |

| Simian adenovirus 1 | AY771780 |

| Simian adenovirus 3 | AY598782 |

| Simian adenovirus 6 | JQ776547 |

| Simian adenovirus 7 | DQ792570 |

| Simian adenovirus 8 | NC_028113 |

| Simian adenovirus 11 | KP329562 |

| Simian adenovirus 13 | NC_028103 |

| Simian adenovirus 16 | NC_028105 |

| Simian adenovirus 18 | CQ982407 |

| Simian adenovirus 19 | NC_028107 |

| Simian adenovirus 20 | HQ605912 |

| Simian adenovirus 21 | AC_000010 |

| Simian adenovirus 22 | AY530876 |

| Simian adenovirus 23 | AY530877 |

| Simian adenovirus 24 | AY530878 |

| Simian adenovirus 25 | AC_000011 |

| Simian adenovirus 26 | HB426768 |

| Simian adenovirus 27 | HC084988 |

| Simian adenovirus 28 | HC084950 |

| Simian adenovirus 29 | HC085020 |

| Simian adenovirus 30 | HB426704 |

| Simian adenovirus 31 | FJ025904 |

| Simian adenovirus 32 | HC085052 |

| Simian adenovirus 33 | HC085083 |

| Simian adenovirus 34 | HC000847 |

| Simian adenovirus 35 | HC085115 |

| Simian adenovirus 36 | HC191003 |

| Simian adenovirus 37 | HB426639 |

| Simian adenovirus 38 | HB426671 |

| Simian adenovirus 39 | HB426607 |

| Simian adenovirus 40 | HC000785 |

| Simian adenovirus 41 | HI964271 |

| Simian adenovirus 42 | HC191035 |

| Simian adenovirus 43 | FJ025900 |

| Simian adenovirus 44 | HC191097 |

| Simian adenovirus 45 | FJ025901 |

| Simian adenovirus 46 | FJ025930 |

| Simian adenovirus 47 | FJ025929 |

| Simian adenovirus 48 | HQ241818 |

| Simian adenovirus 49 | HQ241819 |

| Simian adenovirus 50 | HQ241820 |

| Simian adenovirus ch1 | KF360047 |

| Skunk adenovirus 1 | KP238322 |

| Snake adenovirus 1 | DQ106414 |

| Snake adenovirus 2a | |

| Titi monkey adenovirus 1 | HQ913600 |

| Tree shrew adenovirus 1 | AC_000190 |

| Turkey adenovirus 1 | GU936707 |

| Turkey adenovirus 4 | KF477312 |

| Turkey adenovirus 5 | KF477313 |

The sequence is unpublished.

RESULTS

Analysis of E4orf6 proteins from primate mastadenoviruses. (i) Cul2 and Cul5 binding sequences.

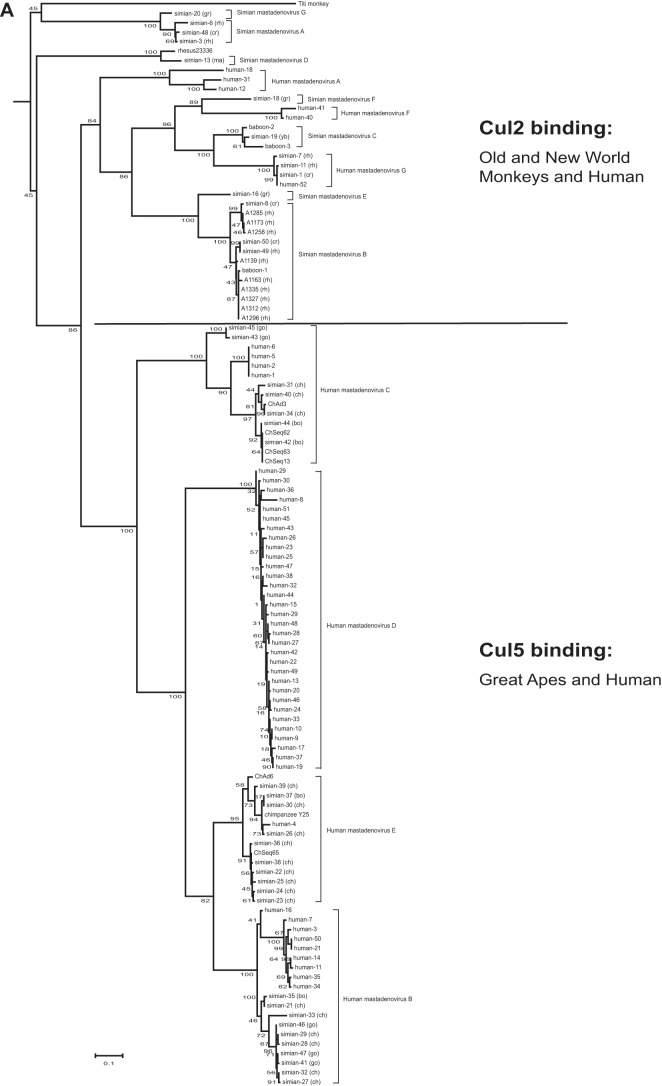

Our previous studies with human adenoviruses showed that the ubiquitin ligase formed by E4orf6 can utilize either Cul2 or Cul5, or in some cases both. Utilization of Cul2 was seen in viruses belonging to HAdV-A and -F (and presumably HAdV-G, based on sequence homology). To further our analysis, we decided to examine more generally other known primate adenoviruses. All the available E4orf6 sequences from primate adenoviruses were collected and aligned using Clustal Omega, and a phylogenetic tree was generated by maximum likelihood analysis. As shown in Fig. 1A, the phylogenetic tree assembled using E4orf6 protein sequences is generally similar to one made based on DNA polymerase sequences (44) in terms of species similarities. But when the tree was analyzed in combination with the sequence alignment of the amino termini shown in Fig. 1B, several interesting observations were made. First, in looking for the Cul2-box motif (highlighted in gray in Fig. 1B), it was evident that there is a clear separation in the tree between predicted Cul2 and Cul5 binding sequences based on the presence or absence of the Cul2 box. As we noted before for human adenoviruses, all human mastadenovirus B, C, D, and E members produce Cul5 binding proteins, whereas significant Cul2 binding is generally restricted to human mastadenovirus A, F, and G strains. Figure 1B shows that viruses from the Simian mastadenovirus A to F species and the unclassified titi monkey AdV all contain the Cul2-box motif. As the sequences adjacent to this motif are also well conserved, it is very likely that they all can bind Cul2, as do the HAdVs containing this sequence. This information also highlights the point that all the nonhuman primate virus E4orf6 proteins predicted to bind Cul2 are produced by monkey viruses, whereas all nonhuman primate virus E4orf6 proteins that lack the Cul2-box motif, and thus may bind Cul5, are produced by great ape (gorilla, bonobo, and chimpanzee) viruses. This finding strongly suggests that the ability to bind Cul5 by primate adenovirus E4orf6 products was acquired when the apes (and hominids) evolved from the other Old World monkeys (see more in Discussion).

FIG 1.

Analysis of primate adenovirus E4orf6 proteins shows a clear separation between Cul2- and Cul5-binding types. (A) Model selection by Topali for alignment of the 118 primate E4orf6 protein sequences suggested a JTT + I + G model. The PhyML calculated tree was visualized by use of Mega6 and rooted at the midpoint. Official species, if determined, are shown following the brackets. The scale bar shows an evolutionary distance of 0.1 amino acid substitution per position. The word “adenovirus” was removed from the type and strain names. Abbreviated names after the type numbers show the hosts of the simian adenoviruses, as follows: bo, bonobo; ch, chimpanzee; cr, crab-eating macaque; go, gorilla; gr, grivet; ma, macaque; rh, rhesus; yb, yellow baboon. (B) The portion of the alignment in which the Cul2 box and the BC boxes are present (roughly equivalent to the second quarter of HAdV-5 E4orf6) is shown in the same order as that for the E4orf6 proteins in the tree. The name of the virus is presented in bold if a Cul2 box is present. Residues present in Cul2 and BC boxes are shaded if the box is present. (C) (Top) Western blots of mouse lung and gut tissues were probed for Cul2, Cul5, or the actin loading control. (Bottom) The same tissue lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with Cul5 antibodies and the precipitates probed with Nedd8 antibodies as well as Cul5 antibodies.

(ii) Selection for Cul2 and Cul5 binding.

Human mastadenovirus A, F, and G members are gastrointestinal viruses, whereas the other human adenoviruses infect mostly the respiratory tract or the eye. Since the HAdV-A, -F, and G viruses employ Cul2, whereas the others use Cul5, we were curious if there might be some functional reason for the selection of Cullin for viruses with enhanced tropism for the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, we harvested the lung and gut tissues from two mice and subjected extracts to Western blotting using antibodies against Cul2 and Cul5. As clearly shown in Fig. 1C, significantly more Cul2 protein was present in extracts from the gut than in those from lung tissues. While the Cul5 levels appeared to be similar for both tissues, there was a clear increase in the abundance of a slower-migrating band for the lung tissues, with slightly more in mouse 2. To be fully active, Cullins must be conjugated to the ubiquitin-like molecule Nedd8. The results for lung tissue suggested that perhaps a more active form of the Cul5-based ligase complex was present in this tissue. To confirm that this species was indeed the Nedd8-conjugated form of Cul5, lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cul5 antibodies and precipitates analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Nedd8 antibodies. Figure 1C (bottom panel) shows that the Cul5 band recognized by the Nedd8 antibody (again most prominent in the lung sample from mouse 2) ran at the same size as the slower-migrating band in the Cul5 blots, confirming that this species was the neddylated form of Cul5. If this Cullin expression pattern resembles that for human gut and lung tissues, differences in such Cullin levels may have helped to promote selection of viruses exhibiting Cul5-based rather than Cul2-based ligase complexes to infect the respiratory tract optimally. It is also interesting that human adenovirus 16 (HAdV-16), which we previously showed to bind efficiently to both Cul2 and Cul5 (despite its lack of a classic Cul2 box), is significantly divergent overall from the other HAdV-B viruses, in keeping with the possibility that an alternative motif to bind Cul2 may have evolved in its E4orf6 sequence.

(iii) BC boxes.

From studies with cellular ligases, the BC-box motif was identified as (STP)LXXX(CSA)XXXΦ (29, 30). As noted earlier, the HAdV-5 E4orf6 protein contains three functional BC boxes (31, 32, 45). Our studies on the HAdV-5 BC boxes also showed that the first residue of this motif is not important and that a glycine can replace the hydrophobic residue at the last position. We also observed that in several E4orf6 BC-box 2 sequences from human AdVs, the leucine residue is replaced with the highly related amino acid isoleucine. This finding now suggests the following modified consensus motif for adenoviruses: (L/I)XXX(CSA)XXX(Φ/G). Using this updated BC-box motif, we examined the sequences of all available simian adenovirus E4orf6 genes and found complete conservation of BC-boxes 2 and 3.

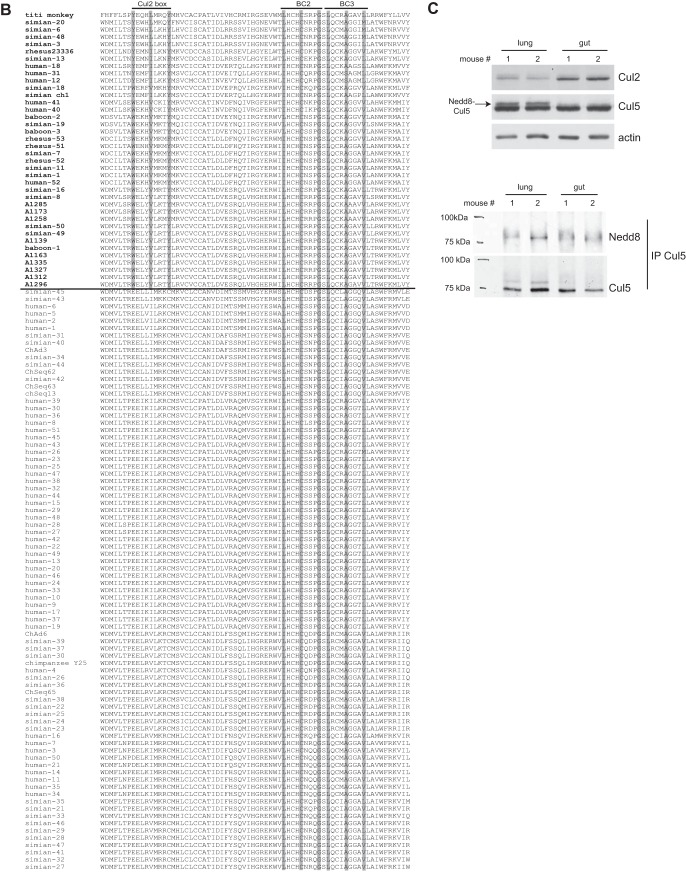

Analysis of E4orf6 proteins from nonprimate mastadenoviruses.

To extend our analysis, we also examined sequences from nonprimate mastadenoviruses. To simplify the visualization of the tree and alignment, only two members of each primate AdV species were included. There are 18 nonprimate mastadenoviruses for which the E4orf6 gene has been sequenced, and all were included in the analysis. The phylogenetic tree is shown in Fig. 2A, and the alignment of sequences for the region containing the motifs is shown in Fig. 2B. As can be seen, there is much more divergence and the potential Cul2 boxes do not exactly align with those in the primate sequences. Nevertheless, the motifs themselves are intact, and we predict the proteins to be Cul2 binding proteins. We also noted some divergence in the region of the BC boxes. Of the 18 nonprimate sequences, only 4 seem to contain an intact BC-box 2 motif; however, all contain the BC-box 3 motif. Other interesting observations can also be made. In this alignment, murine AdV-2 is quite divergent from murine AdV-1 and -3, unlike in an alignment made with several other adenoviral proteins (46). Despite being distant on the E4orf6 evolutionary tree, they still share the Cul2 binding motif. Bovine AdV-10, which is closest to murine AdV-1 and -3, also contains a Cul2 binding motif. Interestingly, this virus has been predicted to have a rodent origin (47). It is also noteworthy that a group of AdVs with a bat origin, including equine AdV-1, canine AdV-1 and -2 (48, 49), and skunk AdV-1 (50), share motifs for predicted binding to Cul5. These observations suggest that the predicted Cullin binding properly reflects adenovirus evolutionary lineages regardless of the current viral host, further supporting the use of the E4orf6-based E3 ubiquitin ligase as a tool to analyze the evolution of adenoviruses.

FIG 2.

Analysis of E4orf6 proteins from mastadenoviruses. (A) Phylogenetic tree for the mastadenovirus E4orf6 protein sequences, including those from the 18 nonprimate viruses. For simplification of the tree, only two representatives of each primate species were included. Model selection by Topali suggested a JTT + I + G model. The PhyML calculated tree was visualized by use of Mega6 and rooted at the midpoint. Actual or predicted Cullin binding is indicted on the right, based on the presence or absence of a Cul2 box, as shown in panel B. The scale bar shows an evolutionary distance of 0.5 amino acid substitution per position. (B) The portion of the alignment in which the Cul2 box and the BC boxes are present (roughly equivalent to the second quarter of HAdV-5 E4orf6) is shown in the same order as that for the E4orf6 proteins in the tree. The name of the virus is presented in bold if a Cul2 box is present. Residues present in the Cul2 box and the BC boxes are shaded if the box is present.

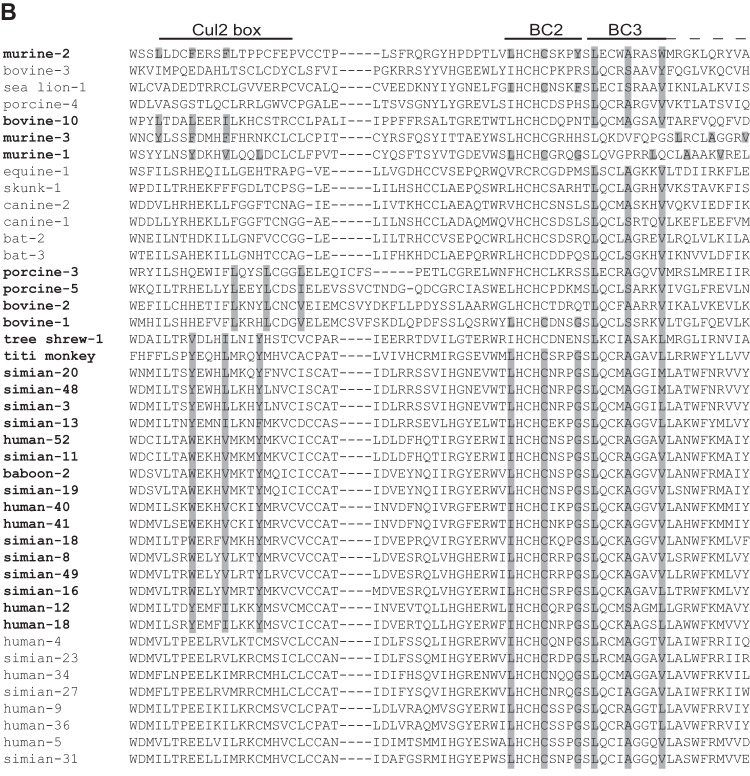

As the nonprimate virus E4orf6 sequences vary much more than those in primate viruses, it became important to test these predictions. To do so, we obtained genetic material from some of the viruses, cloned the E4orf6 gene sequences, and included a FLAG tag. We were also able to obtain and clone the E1B55K coding sequences from murine adenovirus 1. As both Cul2 and Cul5 are very well conserved throughout most animal species (over 95% protein identity in humans, mammals, birds, and reptiles), we tested binding of the various E4orf6 proteins to the human Cullins. First, we started by fully analyzing the complex from MAdV-1. To determine if it binds Cul2 as predicted, H1299 cells were transfected with plasmid DNAs encoding MAdV-1 E4orf6 or one of the controls, HAdV-5 (binding Cul5) and HAdV-12 (binding Cul2), and either HA-tagged Cul2 or HA-tagged Cul5. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies, and precipitates were examined by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Figure 3A shows that, as seen previously, HAdV-5 bound Cul5 and HAdV-12 bound Cul2. As predicted from the presence of the Cul2 box, MAdV-1 did indeed bind Cul2. To confirm that the identified Cul2 box is in fact utilized, key residues were mutated and the mutants also tested. H1299 cells were transfected with plasmid DNAs encoding either the wild-type protein or one of the three mutants and HA-Cul2. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies, and precipitates were examined by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Figure 3B shows that mutating any of the three hydrophobic residues was sufficient to eliminate the binding to Cul2. As shown in Fig. 2B, the MAdV-1 protein contains the two BC-box motifs. To confirm that the MAdV-1 protein binds to Elongin C, H1299 cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding HSV-tagged Elongin C and the FLAG-tagged E4orf6 protein from HAdV-5, HAdV-12, or MAdV-1. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HSV antibodies, and precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3C, all three E4orf6 proteins were able to bind to Elongin C. We also wanted to see if the MAdV-1 E4orf6 protein could bind to its corresponding E1B55K protein. Plasmid DNAs were transfected into H1299 cells, and lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3D, the MAdV-1 E4orf6 protein was indeed able to bind to the E1B55K protein. Thus, the ability of E4orf6 to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex is conserved in this nonprimate adenovirus. We then wanted to confirm that this complex is able to function in targeting substrates for degradation. With the HAdV-5 complex, the first identified substrate was p53. We thus tested the ability of the MAdV-1 complex to degrade mouse p53. H1299 cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding combinations of mouse p53 and MAdV-1 E4orf6 and E1B55K, and after 24 h, lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 3E, and as we have seen previously with HAdV-5, the coexpression of E4orf6 and E1B55K resulted in the degradation of p53, but expression of E4orf6 or E1B55K alone did not. The only common substrate for the ligase complexes of human viruses identified so far is DNA ligase IV (34). To determine if this protein is also a substrate of the MAdV-1 ligase, H1299 cells were transfected with plasmid DNAs as described for the experiment for Fig. 3E, but with a cDNA encoding a myc-tagged form of mouse DNA ligase IV. Shown in Fig. 3F is the surprising result that MAdV-1 E4orf6 alone was sufficient to degrade DNA ligase IV, suggesting that E4orf6 may bind it to induce its degradation. To determine if this is the case, we cotransfected mouse ligase IV with E4orf6 only and tested binding. As shown in Fig. 3G, E4orf6 from MAdV-1 was indeed capable of binding to mouse ligase IV. Together, these results show that E4orf6 from MAdV-1, a nonprimate virus, is fully able to assemble into a functional ubiquitin ligase complex containing E1B55K by using the predicted Cul2 box present in its E4orf6 protein (see more in Discussion).

FIG 3.

Detailed characterization of the MAdV-1 ligase complex. (A) H1299-HA-Cul2 and H1299-HA-Cul5 cells were transfected with a plasmid DNA encoding FLAG-tagged E4orf6 from the indicated virus (and HA-Cul2 for the Cul2 cell line) for 48 h. Immunoprecipitates obtained using anti-FLAG (E4orf6) antibodies and whole-cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated, using appropriate antibodies. (B) H1299 cells were transfected with MAdV-1 FLAG-E4orf6 or a Cul2-box mutant and HA-Cul2 for 24 h. Immunoprecipitates obtained using anti-FLAG (E4orf6) antibodies and whole-cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated, using appropriate antibodies. (C) H1299 cells were transfected with FLAG-E4orf6 from the indicated virus and HSV-tagged Elongin C for 24 h. Immunoprecipitates obtained using anti-HSV (Elongin C) antibodies and whole-cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated, using appropriate antibodies. (D) H1299 cells were transfected with MAdV-1 FLAG-E4orf6 and HA-E1B55K, as indicated, for 24 h. Immunoprecipitates obtained using anti-HA (E1B55K) antibodies and whole-cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated, using appropriate antibodies. (E) H1299 cells were transfected with a combination of plasmid DNAs encoding mouse p53, MAdV-1 FLAG-E4orf6, and MAdV-1 HA-E1B55K, as indicated. After 24 h, whole-cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated, using appropriate antibodies. (F) H1299 cells were transfected and analyzed as described for panel E, except with plasmid DNA encoding mouse DNA ligase IV instead of p53. (G) H1299 cells were transfected with plasmid DNAs expressing MAdV-1 FLAG-E4orf6 and mouse DNA ligase IV, as indicated. After 24 h, immunoprecipitates obtained using anti-Myc (DNA ligase IV) antibodies and whole-cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated, using appropriate antibodies. The asterisk denotes a background band.

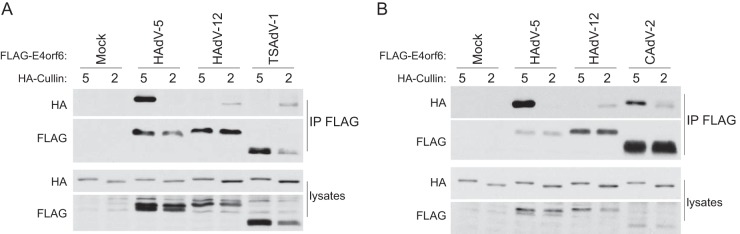

We also examined E4orf6 products from two more nonprimate viruses: tree shrew adenovirus 1 (TSAdV-1), predicted to bind Cul2, and canine adenovirus 2 (CAdV-2), predicted possibly to bind Cul5, as the Cul2 box is absent. In each case, the E4orf6 gene was cloned with introduction of a FLAG tag and the cDNAs transfected into H1299 cells in the presence of cDNA encoding HA-Cul2 or HA-Cul5. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting. Figure 4A shows the results for TSAdV-1, showing again, as predicted from the presence of the Cul2-box motif, that it does bind to Cul2. Figure 4B shows the results for CAdV-2 E4orf6. As predicted from the lack of the Cul2-box motif, it did bind to Cul5; however, we also detected a weak binding to Cul2. This places this E4orf6 protein in the same category as that of HAdV-16, which does not contain a Cul2 box yet binds both Cullins.

FIG 4.

E4orf6 proteins from TSAdV-1 (A) and CAdV-2 (B) bind the predicted Cullins. H1299-HA-Cul2 and H1299-HACul5 cells were transfected with a plasmid DNA encoding FLAG-tagged E4orf6 from the indicated virus (and HA-Cul2 for the Cul2 cell line) for 48 h. Immunoprecipitates obtained using anti-FLAG (E4orf6) antibodies and whole-cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated, using appropriate antibodies.

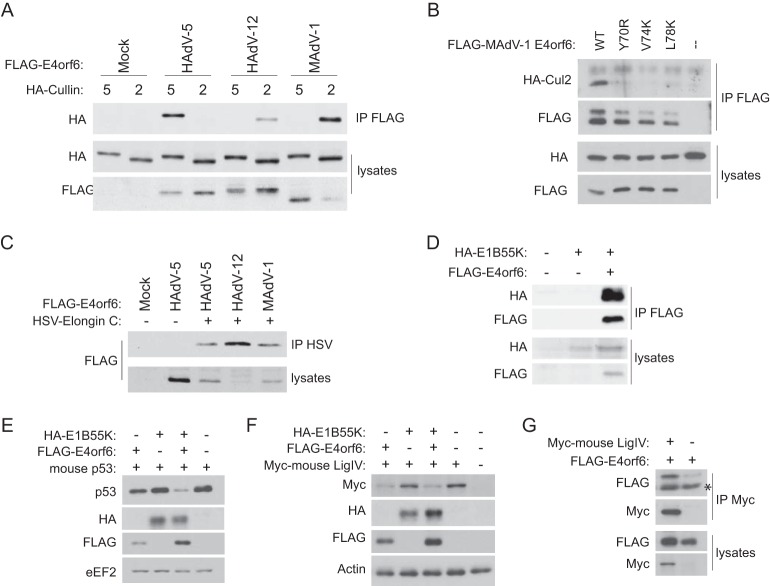

Analysis of E4orf6 proteins from atadenoviruses.

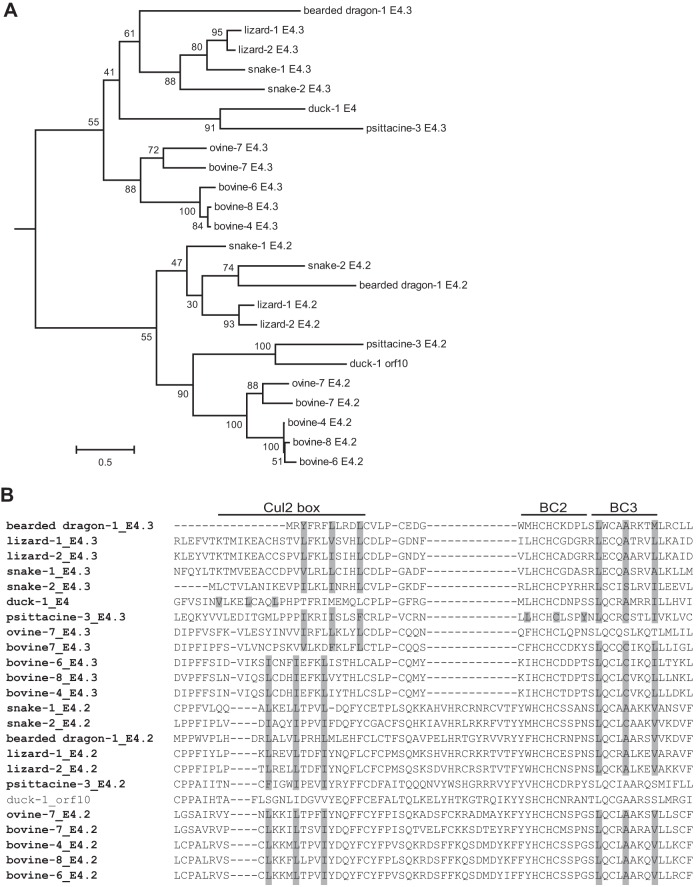

In addition to mastadenoviruses, there is another genus that contains E4orf6 sequences, i.e., Atadenovirus. However, atadenoviruses have a genome organization distinct from that of the mastadenoviruses, and all members contain two E4orf6-related genes. In this genus, there are 12 viruses for which the E4 region has been sequenced, giving a total of 24 E4orf6-like sequences. Figure 5A shows the phylogenetic tree for these sequences. It is very clear from this analysis that the gene duplication happened quite early in the evolution of this genus, or possibly just before the split of atadenoviruses from the other genera. Each form of E4orf6 (E4.3 and E4.2) is well conserved but significantly divergent from the other form in the same virus. Also, as shown in the sequence alignment in Fig. 5B, the ancestral adenovirus E4orf6 sequence contained a Cul2-box motif. All the proteins contain the Cul2-box motif, except for the duck AdV-1 orf10 protein (the same form as E4.2), which has an inserted amino acid between the first two hydrophobic residues. In the members of the genus Atadenovirus, we see an even more pronounced divergence of the BC boxes than that noted with the nonprimate mastadenoviruses. Of the 24 E4orf6 sequences, only 1 contains an intact BC-box 2 motif, while 21 contain the BC-box 3 motif. Most importantly, all 12 viruses contain at least one E4orf6 sequence with at least one BC-box motif, suggesting that each virus can form a ubiquitin ligase complex.

FIG 5.

Analysis of E4orf6 proteins from atadenoviruses. (A) Phylogenetic tree for the atadenovirus E4orf6 protein sequences. Each of the 12 atadenoviruses contained two E4orf6 genes. Model selection by Topali suggested a BLOSOM + I + G model. The PhyML calculated tree was visualized by use of Mega6 and rooted at the midpoint. The scale bar shows an evolutionary distance of 0.5 amino acid substitution per position. (B) The portion of the alignment in which the Cul2 box and the BC boxes are present (roughly equivalent to the second quarter of HAdV-5 E4orf6) is shown in the same order as that for the E4orf6 proteins in the tree. The name of the virus is presented in bold if a Cul2 box is present. Residues present in the Cul2 box and the BC boxes are shaded if the box is present.

To test the Cullin binding specificity of the E4orf6 proteins of these viruses, we cloned both of the E4orf6 genes from duck adenovirus 1 (DAdV-1) and bovine adenovirus 6 (BAdV-6) and introduced a FLAG tag into each. These were analyzed in the same manner as that described for the experiment shown in Fig. 3A. As shown in Fig. 6, there were some surprises. From the lack of a Cul2 box in the DAdV-1 orf10 protein, we predicted binding to Cul5; however, we failed to detect binding to either Cullin. On the other hand, the DAdV-1 E4 protein, predicted to bind Cul2, bound both Cullins. This was our first example of an E4orf6 product containing a Cul2-box motif that was also capable of binding Cul5. For the bovine atadenovirus, both E4orf6 products contain the Cul2 box, and thus both were expected to bind Cul2. Expression of BAdV-6 E4.2 was so weak that it was very difficult to detect in Western blots, but fortunately, concentration by immunoprecipitation was sufficient to allow detection of significant binding to Cul2. The other E4orf6 product was found to bind Cul5. This finding was very surprising, as the Cul2-box motif of BAdV-6 E4.3 aligned well with those of the other E4.3 proteins. It is interesting that binding to both Cul2 and Cul5 was found for both viruses tested, whether for one E4orf6 product or for the combination of both E4orf6 products.

FIG 6.

Cullin binding prediction for atadenovirus E4orf6 proteins shows a more complex picture. H1299-HA-Cul2 and H1299-HA-Cul5 cells were transfected with a plasmid DNA encoding FLAG-tagged E4orf6 from the indicated virus (and HA-Cul2 for the Cul2 cell line). After 48 h, immunoprecipitates obtained using anti-FLAG (E4orf6) antibodies and whole-cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated, using appropriate antibodies.

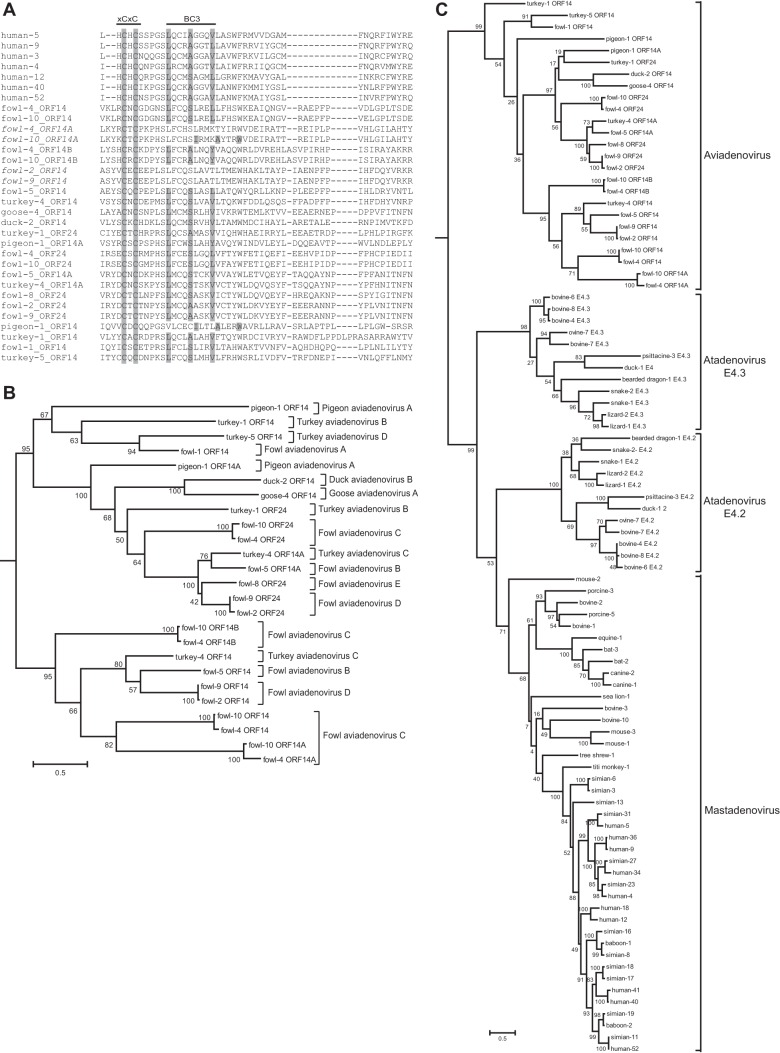

Analysis of E4orf6 proteins from aviadenoviruses.

As mentioned previously, E4orf6 sequences have thus far been identified (and annotated in GenBank) only from mast- and atadenoviruses; however, on manually checking sequences of two aviadenoviruses for the most conserved motif in E4orf6 proteins, the HCHC motif (present in BC-box 2), Nevels et al. found a similar XCXC motif (51). This finding prompted us to examine all sequenced avi- and siadenovirus genomes, and indeed, we identified E4orf6-like sequences in all the aviadenoviruses but none of the siadenoviruses. This sequence in aviadenoviruses is located near the left end of the viral genome (around nucleotide 3000), on the complementing strand and in a position completely different from that in mast- and atadenoviruses, possibly explaining its lack of recognition until now. In most aviadenoviruses, the gene has been duplicated such that up to four E4orf6-type genes exist in some fowl adenoviruses (FAdV-4 and -10 of the species Fowl aviadenovirus C). Figure 7A shows an alignment of a portion of the 25 E4orf6-type gene sequences from 13 aviadenovirus genomes, with the E4orf6 sequences from seven HAdVs added for comparison. All aviadenovirus E4orf6-type genes contain the XCXC motif, which is followed in most cases by a nearby intact BC-box motif (BC-box 3). This motif is missing in three proteins (fowl-4 ORF14A, fowl-2 ORF14, and fowl-9 ORF14) and displaced in two proteins (fowl-10 ORF14A and pigeon-1 ORF14). Shown in Fig. 7B is the phylogenetic tree for these sequences. From this analysis, one can observe that these sequences fall into two major groups, with one further subdivided into two additional groups. These findings may suggest a major gene duplication in an ancestral virus followed by further gene duplications and gene loss at later times. To see how divergent these sequences are from those of the other genera, we generated a phylogenetic tree with the sequences from all genera. To simplify the visualization of the tree, only two members of each primate AdV species were included. As shown in Fig. 7C, the E4orf6 sequences from aviadenoviruses are clearly separate from those of other adenoviruses.

FIG 7.

Identification of E4orf6 proteins from aviadenoviruses. (A) E4orf6 sequences were manually identified for the 13 sequenced aviadenoviruses. These sequences were aligned with seven human adenovirus sequences as a basis to compare motifs. The portion of the alignment in which the BC boxes are present (roughly equivalent to the second quarter of HAdV-5 E4orf6) is shown. Residues present in the conserved XCXC motif and the BC box are shaded if present. (B) Phylogenetic tree for E4orf6 sequences from aviadenoviruses. Model selection by Topali suggested a BLOSUM + I + G model. The PhyML calculated tree was visualized by use of Mega6 and rooted at the midpoint. Official species names are shown following brackets. The scale bar shows an evolutionary distance of 0.5 amino acid substitution per position. (C) Phylogenetic tree for E4orf6 sequences from all three genera. For simplification of the tree, only two representatives of each primate species were included. Model selection by Topali suggested a BLOSUM + I + G model. The PhyML calculated tree was visualized by use of Mega6 and rooted at the midpoint. The scale bar shows an evolutionary distance of 0.5 amino acid substitution per position.

DISCUSSION

Following our previous work with the E4orf6-based ubiquitin ligases of the human adenoviruses, we expanded our analysis to include additional adenoviruses. We found that all mast- and atadenoviruses for which the E4 region has been sequenced can in theory form the ligase complex, as all encode at least one E4orf6 product containing a BC-box motif. We also established, for the first time, that all aviadenoviruses contain one or more E4orf6-like genes. In addition to the conserved XCXC motif, most (and at least one sequence per virus) of the predicted gene products also contain a BC-box motif, suggesting that they may be able to assemble a ligase complex. Surprisingly, however, they do not seem to contain a Cul2 box. It remains to be determined if they do form the ligase complex and, if so, which Cullin they utilize. None of the siadenoviruses was found to contain such a gene. For the mast- and atadenoviruses, we found only three E4orf6 coding sequences (psittacine-3 E4.2, duck-1 orf10, and ovine-7 E4.3) that do not contain any BC-box motif; however, in each of these cases, a second E4orf6 product that does contain one is also present. For the other nine atadenoviruses, which retain BC boxes in both E4orf6 proteins, it is likely that as each protein evolved and became more sequentially diverse from its homologue, each E4orf6 product may have acquired its own unique group of degradation targets. The presence of not one but two differing viral proteins that may degrade different collections of substrates to enhance efficient viral replication is likely advantageous to the virus. Two mastadenoviruses (bovine AdV-3 and porcine AdV-5) have been reported to contain a duplicated E4orf6 gene (3, 47). While exploring this further, we also found duplication in bovine AdV-1 and bovine AdV-2, both of which are closely related to porcine AdV-5 (Fig. 2A). In all cases, the conserved HCHC motif has been lost in the duplicate, and it remains in question whether the duplicates are functional.

We did more extensive work with the murine adenovirus 1 proteins and showed that the E4orf6 and E1B55K proteins do form a functional ligase complex which has the capacity to degrade at least two substrates. Mouse p53 degradation required both viral proteins, as we have seen previously with human AdVs. It was somewhat surprising that only E4orf6 was required for degradation of mouse DNA ligase IV, as both viral proteins are required for degradation of the human counterpart by the human viruses. However, this type of effect is not unique, as it has been observed for the degradation of TOPBP1 by HAdV-12 E4orf6, which binds and degrades this substrate in the absence of E1B55K (36). In this case, MAdV-1 E4orf6 was also shown to associate with mouse DNA ligase IV. Thus, in this kind of situation, where E4orf6 is capable of both forming the ligase complex and binding to the substrate, the presence of E1B55K becomes redundant. However, we believe that with the majority of substrates, it is likely the role of the E1B55K protein to bring the substrate to the complex for ubiquitination.

With the different situations observed in the adenovirus genera, it is interesting to speculate on the evolution of E4orf6 and the ligase complex. The most ancient adenoviruses, siadenoviruses, do not appear to contain an E4orf6-type gene. The aviadenoviruses have up to four E4orf6 genes that mostly encode proteins with a BC box, although the ability to form a ligase complex has not yet been confirmed, and they do not contain an E1B55K gene. The atadenoviruses that contain a duplicated E4orf6 gene, whose product is able to assemble the ligase complex, also contain a gene, LH3, which has been identified as having homology to the E1B55K gene (24). Interestingly, and perhaps surprisingly, the LH3 protein has been found in the capsid (52, 53) and is simply absent in psittacine adenovirus 3. It is unclear at present if LH3 has an additional role as a nonstructural protein or participates in the ligase complex formed by E4orf6. Finally, in the mastadenoviruses, another gene has evolved to replace LH3 at the capsid, encoding protein IX, and this addition might have permitted E1B55K to become fully involved as a regulatory rather than structural protein and a full component of the ligase complex with E4orf6. There also may be an inverse relationship between the presence of a dedicated E1B55K-type protein and the number of E4orf6 genes, as aviadenoviruses contain the largest number of E4orf6-type sequences but no form of E1B55K. This observation can be explained if we assume that in these cases, E4orf6 proteins need to bind the substrates themselves rather than through E1B55K, as is usually the case in the mastadenoviruses. Thus, the presence of duplicated/diverged E4orf6 sequences would allow the virus to bind more substrates while still being able to form the ligase complex. It would be interesting to clone some LH3 genes to determine if the proteins can associate with their corresponding E4orf6 proteins, as well as some aviadenovirus E4orf6 genes to determine if the proteins are able to form a ligase complex.

From the phylogenetic analysis of the aviadenovirus E4orf6 genes presented in Fig. 7B, it might be of interest to consider changing their nomenclature. For example, turkey-4 ORF14A and fowl-5 ORF14A clearly segregate with the ORF24 series, and perhaps also duck-2 ORF14, goose-4 ORF14, and pigeon-1 ORF14A, while pigeon-1 ORF14, turkey-1 ORF14, turkey-5 ORF14, and fowl-1 ORF14 would be in a third group. However, another possibility for naming would be just the opposite, to call all these homologues ORF14s (ORF14 to ORF14C), as they clearly have a common origin and possibly also a common function.

Previous work with human cellular proteins identified the BC-box motif as (TPS)LXXX(CAS)XXXΦ (29, 30). From our detailed work with HAdV-5 and now our analysis of all available E4orf6-like sequences, we slightly modified this motif to (IL)XXX(CAS)XXX(ΦG), with the preceding residue often being a Φ, T, or S. Among adenoviruses, of the 3 BC-box motifs that we originally identified in HAdV-5 E4orf6, only the second and third are relatively well conserved. Of these two, the BC-box 3 motif is the most conserved of all, as it is present in 97% of E4orf6 proteins versus 67% of E4orf6 proteins for BC-box 2. Despite this, the most common motif present in mast- and atadenovirus E4orf6 proteins is the HCHC sequence, which is present within the BC-box 2 motif. It is missing only in the equine AdV-1 protein (where it is replaced with RCRC). Its exact function is not known, as it is also present when the actual BC box is not conserved. Taking into consideration the aviadenoviruses, this motif becomes XCXC and in most cases is followed by a BC-box motif (very often starting with SL or TL). Thus, this combination can effectively be used to identify the E4orf6 protein in a virus.

One of the most interesting observations from these studies is the clear separation of Cul2-binding and Cul5-binding E4orf6 proteins in primate viruses (Fig. 1A). Cosegregating with this separation is whether the viruses were isolated from monkeys or great apes (chimpanzees, gorillas, and bonobos). All viruses isolated from the great apes encode E4orf6 proteins predicted to bind to Cul5 (absence of a Cul2 box), whereas those from all the viruses isolated from monkeys are predicted to bind to Cul2 because of the presence of a Cul2 box. This finding suggests that the Cul5 binding motif, which has not yet been identified for human adenoviruses, was generated when the apes and hominids evolved from the other Old World monkeys. Following that, several host switches presumably occurred when monkey viruses were transmitted to humans, and these may account for the few human adenoviruses (in species HAdV-A, -F, and -G) with the Cul2 box. It is unclear why exactly these great ape viruses evolved the Cul5 box, but it is interesting to speculate that it may be related to the tropism of these viruses and the tissues infected. It has been observed that the viruses containing the Cul2 box are mostly gastrointestinal viruses, whereas those containing the Cul5 box are mostly respiratory viruses. If the Cullin expression pattern in humans is similar to that we observed in mouse tissues, then the abundances of the Cullins in their respective tissues may have helped to influence the evolution of Cullin selection and adaptation in their hosts.

In terms of predicting Cullin usage from the presence or absence of the Cul2-box motif, considerable verification was achieved in the case of the mastadenoviruses. The only case that did not fully conform to expectation was that of CAdV-2 E4orf6, which was predicted to bind Cul5 due to its lack of a Cul2 box but was found to bind both Cullins. This finding is similar to that for the HAdV-16 E4orf6 protein and suggests that these proteins may have evolved either another Cul2-box motif elsewhere in the protein or an alternative motif for binding Cul2. It also suggests that it may be beneficial for the virus to be able to use both Cul2 and Cul5, as seen with both atadenoviruses tested. Prediction of Cullin binding became a little more difficult for the more divergent atadenoviruses. Due to the presence of a Cul2 box, we predicted that three of the four atadenovirus E4orf6 proteins tested would bind Cul2. Two did (DAdV-1 E4 and BAdV-6 E4.2), but one of these predictions was incorrect, i.e., BAdV-6 E4.3 bound to Cul5 rather than Cul2. This was surprising considering that this protein contains a Cul2 box that aligns perfectly with those of the other viruses. This finding suggests that this protein has evolved a very efficient Cul5 binding sequence that preferentially binds Cul5 over the binding of the Cul2 box to Cul2. In fact, the region involved in Cul5 binding may overlap the Cul2 box, resulting in an efficient inhibition of interaction with Cul2. This protein, as well as DAdV-1 E4, which bound Cul5 in addition to Cul2, may be very useful in future studies to identify the as yet unknown Cul5 box in E4orf6 proteins. It would be interesting to determine if all E4.3 proteins can bind Cul5 or whether they predominantly bind to Cul2.

The atadenoviruses coevolved with the squamate reptiles, and some of them switched to avian and ruminant hosts later. The present work again confirmed the substantial differences between the atadenoviruses and mastadenoviruses, but also their similarities, pointing to the possible scenario that these two genera separated more recently than the other genera of Adenoviridae. The high similarity among the snake, lizard, avian, and ruminant atadenoviruses studied so far regarding the existence of the E4orf6/E1B55K ligase complex confirmed that this structure already existed in the ancestor of mast- and atadenoviruses. While we do not know the role of the E1B55K homologue (LH3) in this ancestor, in the atadenoviruses it is a structural protein. The past direction of losing or gaining the role of being a structural part of the virion (cementing the virion instead of protein IX, which exists only in mastadenoviruses) may be determined by finding more ancient mastadenoviruses (e.g., from marsupials or even from the more ancient Prototheria, such as platypuses or echidnas) or atadenoviruses from a more ancient reptile lineage (e.g., tuataras).

We also note the possibility that some of our in silico findings may be the result of mistakes in sequence data in GenBank; however, in all our careful comparative analyses, we made every effort to ensure the validity and interpretation of the presently studied gene sequences.

One last issue concerns the lack of an E1A-like gene in at- and aviadenoviruses. In human adenoviruses, E1A products serve as the central regulators that drive high-level replication even in terminally differentiated nondividing cells. Much of this effect derives from the activation of the E2F transcription factors, by uncoupling them from Rb-based repression complexes (54–59). We recently showed that the E4orf6/E1B55K ligase complex from HAdV-5 is able to mimic many of these effects, although at considerably lower levels than those induced by E1A (60, 61). Thus, it remains possible that with atadenoviruses, the ability to form functional E4orf6/E1B55K ligase complexes may represent a means to enhance at least some level of viral replication in nondividing cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kathy Spindler from the University of Michigan Medical School, Chien-Fu Hung from The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Suresh Tikoo from the University of Saskatchewan, Bernhard Dietzschold at Thomas Jefferson University, and Gary Ketner from The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health for reagents. We also thank Michel Tremblay from McGill University for providing us with mouse tissues.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benko M, Harrach B. 1998. A proposal for a new (third) genus within the family Adenoviridae. Arch Virol 143:829–837. doi: 10.1007/s007050050335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benko M, Harrach B. 2003. Molecular evolution of adenoviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 272:3–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison AJ, Benko M, Harrach B. 2003. Genetic content and evolution of adenoviruses. J Gen Virol 84:2895–2908. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shenk T. 1989. Oncogenesis by DNA viruses: adenovirus, p 239–257. In Weinberg RA. (ed), Oncogenes and the molecular origins of cancer, vol 18 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Jong JC, Wigand R, Kidd AH, Wadell G, Kapsenberg JG, Muzerie CJ, Wermenbol AG, Firtzlaff RG. 1983. Candidate adenoviruses 40 and 41: fastidious adenoviruses from human infant stool. J Med Virol 11:215–231. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890110305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones MS II, Harrach B, Ganac RD, Gozum MM, Dela Cruz WP, Riedel B, Pan C, Delwart EL, Schnurr DP. 2007. New adenovirus species found in a patient presenting with gastroenteritis. J Virol 81:5978–5984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02650-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitz H, Wigand R, Heinrich W. 1983. Worldwide epidemiology of human adenovirus infections. Am J Epidemiol 117:455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uhnoo I, Wadell G, Svensson L, Johansson ME. 1984. Importance of enteric adenoviruses 40 and 41 in acute gastroenteritis in infants and young children. J Clin Microbiol 20:365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cathomen T, Weitzman MD. 2000. A functional complex of adenovirus proteins E1B-55kDa and E4orf6 is necessary to modulate the expression level of p53 but not its transcriptional activity. J Virol 74:11407–11412. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.23.11407-11412.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Querido E, Marcellus RC, Lai A, Charbonneau R, Teodoro JG, Ketner G, Branton PE. 1997. Regulation of p53 levels by the E1B 55-kilodalton protein and E4orf6 in adenovirus-infected cells. J Virol 71:3788–3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth J, Konig C, Wienzek S, Weigel S, Ristea S, Dobbelstein M. 1998. Inactivation of p53 but not p73 by adenovirus type 5 E1B 55-kilodalton and E4 34-kilodalton oncoproteins. J Virol 72:8510–8516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steegenga WT, Riteco N, Jochemsen AG, Fallaux FJ, Bos JL. 1998. The large E1B protein together with the E4orf6 protein target p53 for active degradation in adenovirus infected cells. Oncogene 16:349–357. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wienzek S, Roth J, Dobbelstein M. 2000. E1B 55-kilodalton oncoproteins of adenovirus types 5 and 12 inactivate and relocalize p53, but not p51 or p73, and cooperate with E4orf6 proteins to destabilize p53. J Virol 74:193–202. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.1.193-202.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Querido E, Blanchette P, Yan Q, Kamura T, Morrison M, Boivin D, Kaelin WG, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Branton PE. 2001. Degradation of p53 by adenovirus E4orf6 and E1B55K proteins occurs via a novel mechanism involving a Cullin-containing complex. Genes Dev 15:3104–3117. doi: 10.1101/gad.926401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker A, Rohleder KJ, Hanakahi LA, Ketner G. 2007. Adenovirus E4 34k and E1b 55k oncoproteins target host DNA ligase IV for proteasomal degradation. J Virol 81:7034–7040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00029-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dallaire F, Blanchette P, Groitl P, Dobner T, Branton PE. 2009. Identification of integrin alpha3 as a new substrate of the adenovirus E4orf6/E1B 55-kilodalton E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. J Virol 83:5329–5338. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00089-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A, Jha S, Engel DA, Ornelles DA, Dutta A. 2013. Tip60 degradation by adenovirus relieves transcriptional repression of viral transcriptional activator EIA. Oncogene 32:5017–5025. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orazio NI, Naeger CM, Karlseder J, Weitzman MD. 2011. The adenovirus E1b55K/E4orf6 complex induces degradation of the Bloom helicase during infection. J Virol 85:1887–1892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02134-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiner S, Burck C, Glass M, Groitl P, Wimmer P, Kinkley S, Mund A, Everett RD, Dobner T. 2013. Control of human adenovirus type 5 gene expression by cellular Daxx/ATRX chromatin-associated complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 41:3532–3550. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schreiner S, Kinkley S, Burck C, Mund A, Wimmer P, Schubert T, Groitl P, Will H, Dobner T. 2013. SPOC1-mediated antiviral host cell response is antagonized early in human adenovirus type 5 infection. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003775. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stracker TH, Carson CT, Weitzman MD. 2002. Adenovirus oncoproteins inactivate the Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 DNA repair complex. Nature 418:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature00863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penzes JJ, Menendez-Conejero R, Condezo GN, Ball I, Papp T, Doszpoly A, Paradela A, Perez-Berna AJ, Lopez-Sanz M, Nguyen TH, van Raaij MJ, Marschang RE, Harrach B, Benko M, San Martin C. 2014. Molecular characterization of a lizard adenovirus reveals the first atadenovirus with two fiber genes and the first adenovirus with either one short or three long fibers per penton. J Virol 88:11304–11314. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00306-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.To KK, Tse H, Chan WM, Choi GK, Zhang AJ, Sridhar S, Wong SC, Chan JF, Chan AS, Woo PC, Lau SK, Lo JY, Chan KH, Cheng VC, Yuen KY. 2014. A novel psittacine adenovirus identified during an outbreak of avian chlamydiosis and human psittacosis: zoonosis associated with virus-bacterium coinfection in birds. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e3318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vrati S, Brookes DE, Strike P, Khatri A, Boyle DB, Both GW. 1996. Unique genome arrangement of an ovine adenovirus: identification of new proteins and proteinase cleavage sites. Virology 220:186–199. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyapina SA, Correll CC, Kipreos ET, Deshaies RJ. 1998. Human CUL1 forms an evolutionarily conserved ubiquitin ligase complex (SCF) with SKP1 and an F-box protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:7451–7456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulman BA, Carrano AC, Jeffrey PD, Bowen Z, Kinnucan ER, Finnin MS, Elledge SJ, Harper JW, Pagano M, Pavletich NP. 2000. Insights into SCF ubiquitin ligases from the structure of the Skp1-Skp2 complex. Nature 408:381–386. doi: 10.1038/35042620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng N, Schulman BA, Song L, Miller JJ, Jeffrey PD, Wang P, Chu C, Koepp DM, Elledge SJ, Pagano M, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Harper JW, Pavletich NP. 2002. Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 416:703–709. doi: 10.1038/416703a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamura T, Burian D, Yan Q, Schmidt SL, Lane WS, Querido E, Branton PE, Shilatifard A, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. 2001. Muf1, a novel Elongin BC-interacting leucine-rich repeat protein that can assemble with Cul5 and Rbx1 to reconstitute a ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem 276:29748–29753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamura T, Maenaka K, Kotoshiba S, Matsumoto M, Kohda D, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Nakayama KI. 2004. VHL-box and SOCS-box domains determine binding specificity for Cul2-Rbx1 and Cul5-Rbx2 modules of ubiquitin ligases. Genes Dev 18:3055–3065. doi: 10.1101/gad.1252404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahrour N, Redwine WB, Florens L, Swanson SK, Martin-Brown S, Bradford WD, Staehling-Hampton K, Washburn MP, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. 2008. Characterization of Cullin-box sequences that direct recruitment of Cul2-Rbx1 and Cul5-Rbx2 modules to Elongin BC-based ubiquitin ligases. J Biol Chem 283:8005–8013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanchette P, Cheng CY, Yan Q, Ketner G, Ornelles DA, Dobner T, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Branton PE. 2004. Both BC-box motifs of adenovirus protein E4orf6 are required to efficiently assemble an E3 ligase complex that degrades p53. Mol Cell Biol 24:9619–9629. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9619-9629.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng CY, Blanchette P, Branton PE. 2007. The adenovirus E4orf6 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex assembles in a novel fashion. Virology 364:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanchette P, Kindsmuller K, Groitl P, Dallaire F, Speiseder T, Branton PE, Dobner T. 2008. Control of mRNA export by adenovirus E4orf6 and E1B55K proteins during productive infection requires E4orf6 ubiquitin ligase activity. J Virol 82:2642–2651. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02309-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng CY, Gilson T, Dallaire F, Ketner G, Branton PE, Blanchette P. 2011. The E4orf6/E1B55K E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes of human adenoviruses exhibit heterogeneity in composition and substrate specificity. J Virol 85:765–775. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01890-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng CY, Gilson T, Wimmer P, Schreiner S, Ketner G, Dobner T, Branton PE, Blanchette P. 2013. Role of E1B55K in E4orf6/E1B55K E3 ligase complexes formed by different human adenovirus serotypes. J Virol 87:6232–6245. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00384-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blackford AN, Patel RN, Forrester NA, Theil K, Groitl P, Stewart GS, Taylor AM, Morgan IM, Dobner T, Grand RJ, Turnell AS. 2010. Adenovirus 12 E4orf6 inhibits ATR activation by promoting TOPBP1 degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:12251–12256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914605107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Z, Xiong Y, Zhang W, Tan L, Ehrlich E, Guo D, Yu XF. 2007. Characterization of a novel Cullin5 binding domain in HIV-1 Vif. J Mol Biol 373:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilson T, Cheng CY, Hur WS, Blanchette P, Branton PE. 2014. Analysis of the Cullin binding sites of the E4orf6 proteins of human adenovirus E3 ubiquitin ligases. J Virol 88:3885–3897. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03579-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Querido E, Morrison MR, Chu-Pham-Dang H, Thirlwell SW, Boivin D, Branton PE. 2001. Identification of three functions of the adenovirus E4orf6 protein that mediate p53 degradation by the E4orf6-E1B55K complex. J Virol 75:699–709. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.699-709.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamura T, Sato S, Haque D, Liu L, Kaelin WG Jr, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. 1998. The Elongin BC complex interacts with the conserved SOCS-box motif present in members of the SOCS, ras, WD-40 repeat, and ankyrin repeat families. Genes Dev 12:3872–3881. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soong RS, Trieu J, Lee SY, He L, Tsai YC, Wu TC, Hung CF. 2013. Xenogeneic human p53 DNA vaccination by electroporation breaks immune tolerance to control murine tumors expressing mouse p53. PLoS One 8:e56912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukumoto Y, Obata Y, Ishibashi K, Tamura N, Kikuchi I, Aoyama K, Hattori Y, Tsuda K, Nakayama Y, Yamaguchi N. 2010. Cost-effective gene transfection by DNA compaction at pH 4.0 using acidified, long shelf-life polyethylenimine. Cytotechnology 62:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s10616-010-9259-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milne I, Wright F, Rowe G, Marshall DF, Husmeier D, McGuire G. 2004. TOPALi: software for automatic identification of recombinant sequences within DNA multiple alignments. Bioinformatics 20:1806–1807. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alonso-Padilla J, Papp T, Kajan GL, Benko M, Havenga M, Lemckert A, Harrach B, Baker AH. 2016. Development of novel adenoviral vectors to overcome challenges observed with HAdV-5 based constructs. Mol Ther 24:6–16. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo K, Ehrlich E, Xiao Z, Zhang W, Ketner G, Yu XF. 2007. Adenovirus E4orf6 assembles with Cullin5-ElonginB-ElonginC E3 ubiquitin ligase through an HIV/SIV Vif-like BC-box to regulate p53. FASEB J 21:1742–1750. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7241com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hemmi S, Vidovszky MZ, Ruminska J, Ramelli S, Decurtins W, Greber UF, Harrach B. 2011. Genomic and phylogenetic analyses of murine adenovirus 2. Virus Res 160:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ursu K, Harrach B, Matiz K, Benko M. 2004. DNA sequencing and analysis of the right-hand part of the genome of the unique bovine adenovirus type 10. J Gen Virol 85:593–601. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19697-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kohl C, Vidovszky MZ, Muhldorfer K, Dabrowski PW, Radonic A, Nitsche A, Wibbelt G, Kurth A, Harrach B. 2012. Genome analysis of bat adenovirus 2: indications of interspecies transmission. J Virol 86:1888–1892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05974-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vidovszky MZ, Kohl C, Boldogh S, Gorfol T, Wibbelt G, Kurth A, Harrach B. 2015. PCR screening of the German and Hungarian bat fauna reveals the existence of numerous hitherto unknown adenoviruses. Acta Vet Hung 63:508–525. doi: 10.1556/004.2015.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kozak RA, Ackford JG, Slaine P, Li A, Carman S, Campbell D, Welch MK, Kropinski AM, Nagy E. 2015. Characterization of a novel adenovirus isolated from a skunk. Virology 485:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nevels M, Rubenwolf S, Spruss T, Wolf H, Dobner T. 2000. Two distinct activities contribute to the oncogenic potential of the adenovirus type 5 E4orf6 protein. J Virol 74:5168–5181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.11.5168-5181.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gorman JJ, Wallis TP, Whelan DA, Shaw J, Both GW. 2005. LH3, a “homologue” of the mastadenoviral E1B 55-kDa protein is a structural protein of atadenoviruses. Virology 342:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pantelic RS, Lockett LJ, Rothnagel R, Hankamer B, Both GW. 2008. Cryoelectron microscopy map of atadenovirus reveals cross-genus structural differences from human adenovirus. J Virol 82:7346–7356. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00764-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crescenzi M, Soddu S, Tato F. 1995. Mitotic cycle reactivation in terminally differentiated cells by adenovirus infection. J Cell Physiol 162:26–35. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041620105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fattaey AR, Harlow E, Helin K. 1993. Independent regions of adenovirus E1A are required for binding to and dissociation of E2F-protein complexes. Mol Cell Biol 13:7267–7277. doi: 10.1128/MCB.13.12.7267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mal A, Chattopadhyay D, Ghosh MK, Poon RY, Hunter T, Harter ML. 2000. p21 and retinoblastoma protein control the absence of DNA replication in terminally differentiated muscle cells. J Cell Biol 149:281–292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spindler KR, Eng CY, Berk AJ. 1985. An adenovirus early region 1A protein is required for maximal viral DNA replication in growth-arrested human cells. J Virol 53:742–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Svensson C, Akusjarvi G. 1984. Adenovirus 2 early region 1A stimulates expression of both viral and cellular genes. EMBO J 3:789–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whyte P, Buchkovich KJ, Horowitz JM, Friend SH, Raybuck M, Weinberg RA, Harlow E. 1988. Association between an oncogene and an anti-oncogene: the adenovirus E1A proteins bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature 334:124–129. doi: 10.1038/334124a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dallaire F, Schreiner S, Blair GE, Dobner T, Branton PE, Blanchette P. 2015. The human adenovirus type 5 E4orf6/E1B55K E3 ubiquitin ligase complex can mimic E1A effects on E2F. mSphere 1:00014-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dallaire F, Schreiner S, Blair GE, Dobner T, Branton PE, Blanchette P. 2015. The human adenovirus type 5 E4orf6/E1B55K E3 ubiquitin ligase complex enhances E1A functional activity. mSphere 1:e00015-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]