Abstract

Objectives. To examine changes over 40 years (1970–2010) in life expectancy, life expectancy with disability, and disability-free life expectancy for American men and women of all ages.

Methods. We used mortality rates from US Vital Statistics and data on disability prevalence in the community-dwelling population from the National Health Interview Survey; for the institutional population, we computed disability prevalence from the US Census. We used the Sullivan method to estimate disabled and disability-free life expectancy for 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010.

Results. Over the 40 years, there was a steady increase in both disability-free life expectancy and disabled life expectancy. At birth, increases in disabled life and nondisabled life were equal for men (4.5 years); for women, at birth the increase in life with disability (3.6 years) exceeded the increase in life free of disability (2.7 years). At age 65 years, the increase in disability-free life was greater than the increase in disabled life.

Conclusions. Across the life cycle, there was no compression of morbidity, but at age 65 years some compression occurred.

Are we living longer healthy lives as well as longer lives? Over the past 30 years, researchers have addressed this question using data for relatively short periods of time, and the answer has not been a consistent yes or no.1–4 The answer depended on the years of observation as well as the measure of health examined and the composition of the population studied.

Interest in the length of high-quality life as well as the quantity of life began as life expectancy increased at older ages and mortality decline was concentrated in chronic diseases.5,6 The possibility was raised that we could be increasing the length of poor-quality life but not good-quality life. Opposing views on what would happen to healthy life with improvements in life expectancy in a population with high levels of chronic disease ranged from “compression of morbidity,”7 which foresaw an extension of healthy life and an elimination of unhealthy life, to “failure of success,”8,9 which focused on the fact that the sick and frail could become more numerous. In the middle was the view of Manton, who predicted “dynamic equilibrium”5 or balanced changes in healthy and unhealthy life.

Using data for the United States for 1970 to 1990, researchers identified different trends in disability-free life expectancy at birth.2 In the 1970s, almost all of the increases in life expectancy were in disabled years; by contrast, the 1980s were a period when increases in life expectancy were concentrated in years without disability. Examining change in time spent with severe disability among older age groups, Cai and Lubitz found increases in total life expectancy and decreases in disabled years.1 By contrast, Crimmins et al., using a different data set representing people older than 70 years and a somewhat different definition of disability, found increases in disability-free life equal to the increases in total-life expectancy and no change in life with disability between 1984 and 2000.3 Generalizing from a number of studies on time trends beginning in the 1960s and going through the early 1990s, Cambois and Robine concluded that the trend in the United States was toward increases in life free of severe disability that were keeping pace with increases in life expectancy, but also increases in years of life with mild disability.10

The United States is not exceptional in showing mixed results in terms of increasing healthy life. Examination of changes in disabled and disability-free life expectancy in 14 European countries from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s indicated that the countries fell into 3 groups: those with an increasing proportion of healthy life, those with stability in the proportion of life free of severe disability, and those where the proportion of life with severe disability increased.11 Cambois and Robine also found mixed trends in European countries through the 1980s and early 1990s—there were increases in disabled life in some and decreases in others, but in general they concluded that years with severe disability were not increasing.10

Understanding trends in healthy and disability-free life expectancy is important for planning and policy. For instance, changes in the age of full entitlement to social security should be made with knowledge of trends in disability-free life rather than total life expectancy. In light of this, governments and international agencies have begun to set goals for extending disability-free life as well as total life and for monitoring change in disability-free life.12,13

To get a long-term perspective, we examined 40 years of change—covering 5 decennial censuses (1970–2010)—in life expectancy, disabled life expectancy, and disability-free life expectancy for American men and women. To our knowledge, this is the longest series of disability-free life expectancy examined to date, beginning at about the time of the initiation of the substantial decline in old-age mortality that instigated interest in the question we address. Our analysis accounted for disabled life spent in institutions as well as in the community.

METHODS

Healthy life expectancy measures combine indicators of morbidity and mortality so that life expectancy can be divided into healthy and unhealthy expected life. Healthy life can be defined along any number of health dimensions (e.g., disease, disability, functioning) and can be computed with multiple methodological approaches.14 Here, we define “healthy life” as disability-free life and “unhealthy life” as life with disability, and we use the Sullivan method for computing healthy and unhealthy life expectancy.15 Disability-free life expectancy reflects the average number of remaining years at a specified age a person can expect to live without disability given current mortality and disability conditions; disabled years are the expected number of years to be lived with disability after a given age. Because of the way the data were collected, we distinguished between disabled years in the community and disabled years spent in institutions for health reasons. As with total life expectancy, disabled and disability-free life expectancy were estimated so they would be free of the influence of changing age structure and could be compared across time.

To compute disability-free and disabled life expectancy, we divided the years lived in each age group into disabled and nondisabled, using the prevalence of disability at each age. We summed years lived disabled at all ages after the specified age and divided them by the number of people alive at that age to get disabled life expectancy; we determined disability-free life expectancy by subtracting disabled life expectancy from total life expectancy.14,15 For the working ages (20–64 years), we computed partial life expectancy values (i.e., years lived between 2 ages). We computed standard errors and confidence intervals for the estimated values using the approach provided by Jagger et al.15

Estimating disability-free life expectancy over time requires information on mortality and disability for the entire population that is comparable at each date. We computed our life tables using data for 5-year age–gender groups. Mortality data for this analysis were from US National Vital Statistics. For 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000, we used the decennial life tables for the United States. Because the decennial life table for 2010 is not yet available, we used the annual life table for 2010.

To meet its charge of monitoring the health and health care utilization of noninstitutionalized Americans, the US National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) has regularly collected information on disability in the National Health Interview Survey since 1957, using reasonably comparable methods. This annual survey provides individual-level data for 51 years of the survey (1963–2013), which are available from the Integrated Health Interview Series developed by the University of Minnesota (https://www.ihis.us/ihis). Although disability has been measured throughout the period, the questions used to elicit reports of disability have changed somewhat over time (Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The questions allowed us to construct a series on disability in the community-dwelling population in which disability is defined as having any limitation of activity (i.e., being limited in any way in the performance of one’s usual or other activities). This definition encompasses all disability, both major and minor.

In earlier analyses, we adjusted the time series on disability for changes that occurred between 1981 and 1982 that affected selected age groups2; for this study, we also adjusted the annual data for changes between 1996 and 1997 so that the analysis would be fully comparable to the earlier series at each of the years. We used the final basic weight provided by the NCHS. Our approach to the adjustment was to estimate the trend within periods when the questions were consistent and then estimate the change between periods. Online Appendix A provides a detailed description of the methods used to do this. We then used 3 years of data for each date to get an estimate of age–gender-specific levels of disability in the community-dwelling population at 10-year intervals from 1970 to 2010. We provide confidence intervals for the prevalences based on the 3-year sample size and the complex sample design.

Information on those in institutions because of disability was collected in the decennial census. For the first 3 years (1970, 1980, and 1990), we used the age-specific prevalence data indicating institutionalization for health or functioning problems from Crimmins et al.2 For 2000 and 2010, we used census information on the population in group quarters who are in nursing homes or other institutions, including hospitals or wards, hospices, and schools for the handicapped. We assumed that all people institutionalized in these types of facilities were disabled. Appendix B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides details on procedures used to estimate age-specific prevalence of institutional disability. Because the data were from population censuses, we did not construct confidence intervals.

RESULTS

First, we discuss trends in the inputs to the life tables and then we discuss the trends in the life expectancy values that result from combining the inputs to create estimates of health expectancy states.

Trends in Prevalence of Disability

The trend over the 40 years in the prevalence of disability in the community population differed by age (Table 1). For those younger than 65 years, there was some increase in disability over the whole period, particularly at the younger ages. For those older than 65 years, there was a decline in disability after 1980. Over the entire period, the change was generally similar for males and females, with the exception of those aged 85 years and older, among whom only women experienced improvement.

TABLE 1—

Percentage of Individuals With Disability in the Community: United States, 1970–2010

| Age Group, y | 1970, % (95% CI) | 1980, % (95% CI) | 1990, % (95% CI) | 2000, % (95% CI) | 2010, % (95% CI) |

| Males | |||||

| 0–19 | 3.7 (3.6, 3.8) | 4.6 (4.4, 4.8) | 4.9 (4.7, 5.1) | 6.1 (5.8, 6.4) | 8.0 (7.7, 8.3) |

| 20–64 | 13.7 (13.5, 13.9) | 14.8 (14.6, 15.0) | 13.6 (13.4, 13.8) | 14.7 (14.5, 14.9) | 15.9 (15.7, 16.1) |

| 65–84 | 45.2 (44.3, 46.1) | 48.3 (47.4, 49.2) | 46.7 (45.9, 47.5) | 45.5 (44.7, 46.3) | 42.7 (41.8, 43.6) |

| ≥ 85 | 65.0 (61.5, 68.5) | 65.3 (61.9, 68.7) | 62.8 (59.6, 66.0) | 63.5 (60.3, 66.7) | 64.5 (61.6, 67.4) |

| Females | |||||

| 0–19 | 2.6 (2.5, 2.7) | 3.6 (3.4, 3.8) | 3.7 (3.5, 3.9) | 4.3 (4.1, 4.5) | 5.4 (5.1, 5.7) |

| 20–64 | 11.8 (11.6, 12.0) | 13.7 (13.5, 13.9) | 13.2 (13.0, 13.4) | 14.4 (14.2, 14.6) | 15.6 (15.4, 15.8) |

| 65–84 | 38.3 (37.6, 39.0) | 41.7 (41.0, 42.4) | 39.8 (39.1, 40.5) | 38.2 (37.5, 38.9) | 36.1 (35.3, 36.9) |

| ≥ 85 | 68.2 (65.5, 70.9) | 64.8 (62.3, 67.3) | 64.4 (62.3, 66.5) | 64.0 (61.9, 66.1) | 62.4 (60.3, 64.5) |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

Source. National Health Interview Survey (3 years of data around each date).

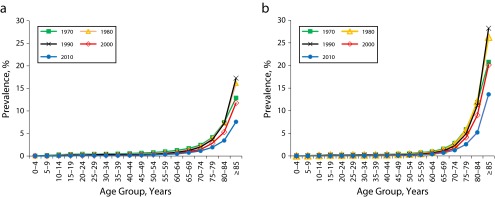

Over time, there was a marked drop in the percentage of the population in institutions for health reasons at all ages, although, except for the oldest age groups, the percentage in institutions was very low in all years (Figure 1). For the oldest age group (≥ 85 years), which had the highest level of institutionalization, the maximum percentage institutionalized was reached in 1990, after which there were marked declines. Although the change was similar by gender, among older people, more women than men were institutionalized at older ages.

FIGURE 1—

Age-Specific Prevalence of Institutionalization for Health Reasons at 5 Dates for (a) Males and (b) Females: United States, 1970–2010

Note. Details on sources of data are given in the online appendixes, available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.

Trends in Life Expectancy

In the United States, life expectancy at birth increased in each of the decades from 1970 through 2010: by 9.2 years (from 67.0 to 76.2 years) for men and by 6.4 years (from 74.6 to 81.0 years) for women (Table 2). For women, the increase was fairly rapid in the first decade of the period and fairly slow more recently; for men, the trend was more consistent.

TABLE 2—

Expected Years of Life Spent in Various States of Health, at Birth and at Ages 20–64, 65, and 85 Years, by Gender: United States, 1970–2010

| State of Health | 1970, Mean (95% CI) | 1980, Mean (95% CI) | 1990, Mean (95% CI) | 2000, Mean (95% CI) | 2010, Mean (95% CI) | Change, 1970–2010 |

| Males | ||||||

| At birth | ||||||

| Total | 67.0 | 70.1 | 71.8 | 74.1 | 76.2 | 9.2 |

| Free of disability | 56.5 (56.4, 56.6) | 57.2 (57.1, 57.4) | 58.8 (58.6, 58.9) | 60.0 (59.9, 60.2) | 61.0 (60.9, 61.2) | 4.5 |

| With disability in community | 10.0 (9.8, 10.1) | 12.2 (12.1, 12.4) | 12.4 (12.3, 12.6) | 13.6 (13.4, 13.7) | 14.7 (14.6, 14.9) | 4.7 |

| Institutionalized | 0.6 (0.6, 0.6) | 0.6 (0.6, 0.7) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.7) | 0.5 (0.5, 0.6) | 0.4 (0.4, 0.5) | −0.2 |

| At ages 20–64 y | ||||||

| Total | 40.8 | 41.6 | 41.8 | 42.4 | 42.6 | 1.8 |

| Free of disability | 34.9 (34.8, 35.0) | 34.7 (34.6, 34.8) | 35.3 (35.2, 35.4) | 35.6 (35.5, 35.7) | 35.8 (35.7, 35.9) | 0.9 |

| With disability in community | 5.7 (5.6, 5.8) | 6.7 (6.6, 6.8) | 6.4 (6.3, 6.5) | 6.7 (6.6, 6.8) | 6.8 (6.7, 6.9) | 1.1 |

| Institutionalized | 0.3 (0.2, 0.3) | 0.2 (0.2, 0.2) | 0.2 (0.2, 0.2) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.1) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.1) | −0.2 |

| At age 65 y | ||||||

| Total | 13.0 | 14.2 | 15.1 | 16.1 | 17.7 | 4.7 |

| Free of disability | 6.6 (6.6, 6.8) | 6.8 (6.7, 6.9) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.5) | 8.2 (8.0, 8.3) | 9.3 (9.1, 9.4) | 2.7 |

| With disability in community | 5.8 (5.7, 5.9) | 6.8 (6.7, 6.9) | 7.0 (6.9, 7.2) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.5) | 8.0 (7.8, 8.1) | 2.2 |

| Institutionalized | 0.5 (0.5, 0.5) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.6) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.7) | 0.5 (0.5, 0.6) | 0.4 (0.4, 0.5) | −0.1 |

| At age 85 y | ||||||

| Total | 4.7 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 1.1 |

| Free of disability | 1.4 (1.3, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | 1.6 (1.5, 1.8) | 1.8 (1.6, 1.9) | 1.9 (1.8, 2.1) | 0.5 |

| With disability in community | 2.7 (2.5, 2.8) | 2.8 (2.6, 3.0) | 2.8 (2.6, 2.9) | 3.0 (2.9, 3.2) | 3.5 (3.3, 3.6) | 0.8 |

| Institutionalized | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8) | 0.4 (0.4, 0.5) | −0.2 |

| Females | ||||||

| At birth | ||||||

| Total | 74.6 | 77.6 | 78.8 | 79.5 | 81.0 | 6.4 |

| Free of disability | 62.7 (62.6, 62.8) | 62.8 (62.6, 63.0) | 63.9 (63.8, 64.0) | 64.6 (64.4, 64.7) | 65.4 (65.3, 65.6) | 2.7 |

| With disability in community | 10.9 (10.7, 11.0) | 13.4 (13.3, 13.6) | 13.4 (13.3, 13.6) | 13.8 (13.6, 14.0) | 14.8 (14.6, 15.0) | 3.9 |

| Institutionalized | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 1.4 (1.3, 1.5) | 1.5 (1.4, 1.5) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 0.8 (0.8, 0.9) | −0.3 |

| At ages 20–64 y | ||||||

| Total | 42.8 | 43.3 | 43.5 | 43.6 | 43.7 | 0.9 |

| Free of disability | 37.4 (37.3, 37.5) | 36.7 (36.6, 36.8) | 37.0 (36.9, 37.1) | 36.9 (36.8, 37.0) | 36.8 (36.7, 37.0) | −0.6 |

| With disability in community | 5.2 (5.2, 5.3) | 6.5 (6.4, 6.6) | 6.3 (6.2, 6.4) | 6.6 (6.5, 6.7) | 6.8 (6.7, 6.9) | 1.6 |

| Institutionalized | 0.2 (0.2, 0.2) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.2) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.1) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.1) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) | −0.1 |

| At age 65 y | ||||||

| Total | 16.8 | 18.4 | 19.0 | 19.1 | 20.3 | 3.5 |

| Free of disability | 9.1 (9.0, 9.2) | 9.3 (9.2, 9.4) | 9.9 (9.8, 10.0) | 10.5 (10.3, 10.6) | 11.5 (11.4, 11.6) | 2.4 |

| With disability in community | 6.6 (6.5, 6.7) | 7.6 (7.5, 7.8) | 7.5 (7.4, 7.7) | 7.5 (7.3, 7.6) | 8.0 (7.8, 8.1) | 1.4 |

| Institutionalized | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 1.5 (1.4, 1.6) | 1.6 (1.5, 1.6) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | 0.9 (0.8, 0.9) | −0.2 |

| At age 85 y | ||||||

| Total | 5.6 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.9 | 1.3 |

| Free of disability | 1.4 (1.3, 1.6) | 1.7 (1.5, 1.8) | 1.7 (1.6, 1.8) | 1.9 (1.8, 2.0) | 2.2 (2.1, 2.4) | 0.8 |

| With disability in community | 3.0 (2.9, 3.2) | 3.0 (2.9, 3.2) | 3.1 (2.9, 3.2) | 3.3 (3.2, 3.5) | 3.7 (3.6, 3.9) | 0.7 |

| Institutionalized | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | 1.7 (1.5, 1.8) | 1.9 (1.8, 2.0) | 1.4 (1.3, 1.5) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | −0.3 |

Note. CI = confidence interval. Sum of life expectancy in states sometimes does not add to total expectation of life because of rounding.

A greater increase in male life expectancy over the period characterized each age up to 85 years. Gains in life expectancy during the working years were larger for men (1.8 years) than for women (0.9 years); the same was true at age 65 years: for men, the increase in life expectancy was 4.7 years (from 13.0 to 17.7 years), whereas for women it was only 3.5 years (from 16.8 to 20.3 years). At age 85 years, life expectancy over the 40-year period increased by 1.1 years for men and 1.3 years for women. For both men and women, about half of the increase in life expectancy at birth was due to increasing life expectancy after age 65 years.

Trends in Disability-Free Life Expectancy

Table 2 also shows the results of combining age-specific mortality with disability in the community and in institutions. There was a steady increase in disability-free life expectancy at birth over the 30 years after 1980 for women and over the entire 40-year period for men (Table 2). Over the 40-year period, the gain at birth was 4.5 years for men and 2.7 years for women. In the working ages, disability-free life expectancy increased for men (0.9 years) but decreased for women (–0.6 years); at age 65 years, the increase was greater for men (2.7 years) than for women (2.4 years), and the increases in each of the last 3 decades were significant for both men and women. When we compared increases in disability-free life expectancy at birth and at age 65 years across the life span, most of the increase occurred at older ages for women but was fairly evenly split before and after age 65 years for men. At age 85 years, the increase was half a year for men and 0.8 years for women. The increase was significant over the 40 years for both men and women, but the change from decade to decade was so small that it was statistically significant only from 2000 to 2010 for women.

Trends in Life Expectancy With Disability

Life expectancy with disability in the community and in institutions comprises total disabled life. Over the 40 years, expected years at birth of life expectancy with disability in the community increased by 4.7 years for men and 3.9 years for women. The increase was significant for both men and women during the 1970s and the 2000s and was significant for men in the 1990s. Over the 40 years, life with disability in the community was the category in which the increase in life expectancy at birth was largest. In the working years, for women, disabled life expectancy in the community increased (1.6 years) and nondisabled life expectancy decreased (0.6 years); for men, the changes in disabled and nondisabled life expectancy in the community were closer to equal (1.1 and 0.9 years of increase, respectively). Regarding institutional life, for men, change in total disabled and nondisabled life in the working years was equal; for women, the increase in disabled years was greater.

Over the 40 years, at age 65 years, the increase in disabled life expectancy in the community was 2.2 years for men and 1.4 years for women. The increase was significant in 3 of the decades for men and in 2 of them for women. At age 85 years, years with disability in the community increased similarly and significantly for men and women (0.8 for men vs 0.7 for women). Over the 40 years, average expected time spent in institutions was reduced by 0.2 and 0.3 years for men and women, respectively. This change occurred after the age of 85 years, when institutionalization is most common. At age 85 years, change in life expectancy for men was about equally distributed between disabled life (0.6 years) and nondisabled life (0.5 years); for women, the increase in nondisabled life (0.8 years) was twice that in disabled life (0.4 years).

Proportion of Life With and Without Disability

Combining these changes in life expectancy, we found reductions in the proportion of expected life at birth free of disability over the 40-year period (Table 3). For men, life free of disability at birth declined by 4.1 percentage points; for women, the decline was 3.3 percentage points. Data for the working ages indicated some reduction in the percentage of life free of disability for both men (1.5 percentage points) and women (3.2 percentage points). Both at birth and in the working ages, the negative change occurred in the first decade of the period.

TABLE 3—

Percentage of Expected Life in Various States of Health, at Birth and at Ages 20–64, 65, and 85 Years, by Gender: United States, 1970–2010

| Males, % |

Females, % |

|||||||||

| State of Health | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 |

| At birth | ||||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Free of disability | 84.2 | 81.6 | 81.8 | 81.0 | 80.1 | 84.0 | 80.9 | 81.1 | 81.3 | 80.7 |

| With disability in community | 14.9 | 17.4 | 17.3 | 18.4 | 19.3 | 14.6 | 17.3 | 17.0 | 17.4 | 18.3 |

| Institutionalized | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| At ages 20–64 y | ||||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Free of disability | 85.5 | 83.4 | 84.4 | 84.0 | 84.0 | 87.4 | 84.8 | 85.0 | 84.6 | 84.2 |

| With disability in community | 14.0 | 16.1 | 15.3 | 15.8 | 16.0 | 12.1 | 15.0 | 14.5 | 15.1 | 15.1 |

| Institutionalized | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| At age 65 y | ||||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Free of disability | 51.2 | 47.8 | 49.1 | 50.9 | 52.5 | 54.2 | 50.5 | 52.0 | 55.0 | 56.7 |

| With disability in community | 45.0 | 48.0 | 46.6 | 46.0 | 45.2 | 39.2 | 41.5 | 39.9 | 39.3 | 39.4 |

| Institutionalized | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 6.6 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 4.4 |

| At age 85 y | ||||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Free of disability | 30.4 | 29.0 | 30.8 | 32.7 | 32.8 | 25.2 | 26.0 | 25.5 | 28.8 | 31.9 |

| With disability in community | 56.7 | 55.0 | 51.9 | 56.4 | 60.3 | 54.0 | 47.6 | 46.2 | 51.5 | 53.6 |

| Institutionalized | 12.9 | 16.0 | 17.3 | 10.9 | 6.9 | 20.8 | 26.3 | 28.2 | 19.7 | 13.0 |

Note. Life expectancy in states sometimes does not add to 100% because of rounding.

After age 65 years, however, the proportion of expected life free of disability increased over the 40 years, by 1.3 percentage points for men and 2.5 percentage points for women; at age 85 years, the increase was 2.4 percentage points for men and 6.7 percentage points for women. This increase resulted from a decrease in the proportion of life spent disabled in institutions rather than in the community; across the 40-year period, the latter figure increased for men and stayed fairly stable for women.

DISCUSSION

The period we examined was one of increasing life expectancy, more consistently for men than for women. Over the 40 years, men’s gain in life expectancy exceeded that of women by 44%. At birth, for men, the increase in life expectancy was equally split between disabled and nondisabled years; for women, the increase in disabled life over the whole period exceeded the increase in nondisabled life by about 50%. During the working years, the change in disabled and disability-free years was equal for men but for women the increases in disability-free life were small relative to the increases in disabled life. At age 65 years, the increase in nondisabled life exceeded that in disabled life. After age 85 years, because institutionalized life was reduced, women’s increase in disability-free life exceeded that in disabled life; for men, however, the decrease in institutionalized life was not large enough to outweigh the increase in disabled life in the community, making the increase in disabled and nondisabled life about equal.

If we define compression of morbidity as an increase in the proportion of disability-free life, there was no compression across the total life span in the United States from 1970 through 2010 but rather some decrease in the proportion of life free of disability. Most of this decrease occurred in the first decade of the 40-year period; from 1980 through 2010, the proportion of life expectancy at birth free of disability stayed virtually constant. There was also no compression of morbidity during the working years. In general, the 1970s were a period of more negative trends, with some expansion of morbidity, and relative stability from the 1980s onward.

After 1980, there was some compression of morbidity at the older ages (≥ 65 and ≥ 85 years), with an increase in the proportion of life free of disability. This improvement among the old, but not the young, reinforces much of the existing work on trends in disability.16,17 Our study clarifies that these declines in disability at older ages combined with declines in mortality in recent decades to increase the length of life free of disability and decrease the length of life with disability in this age range.

Different factors may be affecting disability at different ages and among these different cohorts. Some of the increase in disability among the younger population likely resulted from change in emphasis in mental health, the rise in autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and the changing patterns of drug use across time. Changes in drug use, emotional well-being, and alcoholism in the working ages may have resulted in increased disability during those years. Changes in both the young and the working-age groups may also reflect change in ideas about how to define disability. Decrease in institutionalization among the old may be related to changes in costs, regulations, and norms for nursing home use rather than changes in innate disability. On the other hand, there are factors that have had similar impacts across the age range, such as the long-term increase in obesity.

Our analysis has demonstrated the importance of including the institutional population in an analysis of changes in disabled life over time. Even after major declines in the percentage institutionalized, in the United States in 2010, institutionalized life accounted for 7% of life expectancy at age 85 years among men and 13% among women. Reductions in this percentage since 1970 have decreased the relative importance of life in institutions and have been a force against reduction in disability levels in the community.

There are limitations to our analysis. Because of changing definitions of disability, we needed to harmonize our data over time by using estimating procedures. In addition, data availability limited us to 1 definition of disability, and we were not able to examine trends in minor and more major disability. Finally, we were not able to control for changes over time in people’s assessment of their health and ability, or changes in the environment that affect ability and disability. However, we believe that the unique characteristics of our analysis outweigh its limitations. We covered the longest period of time examined for trends in healthy life expectancy, the entire age range, the range of disability severity, and the institutional as well as the community-dwelling population.

Our analysis has produced results that add significantly to our ability to definitively describe the long-term trend in disability-free life expectancy and to interpret and integrate earlier work on trends in healthy life expectancy. The decade of the 1970s appears to have been one of expansion of morbidity, which coincided with the early years of preventing mortality from chronic conditions among the old. In this period, trends may have reflected saving the ill without gains from prevention, the beginning of the real growth in obesity, and increases in drug usage that may have led to increased disability among some age groups. After 1980, there appears to have been compression of morbidity among the older population. Trends for the younger population, including the working-age population, are problematic. Although the increase in life expectancy free from and with disability in these ages is keeping pace, indicating dynamic equilibrium, there is no indication that the working-age group’s ability to support an increasingly older population through higher Social Security and Medicare payments is growing. In sensitivity analyses, we examined the change over time in life expectancy assuming that the working ages were 20 to 70 years; the conclusions were similar to those we present for age 65 years. There is little evidence from this analysis of improving health in this age range that would support increasing the age at retirement.

The outlook for the future depends on the trends in disability across the age range. It appears that we may have begun to prevent or delay the onset of some diseases as well as their progression to disability, which would be a positive influence.18 In addition, the obesity epidemic appears to be abating.19 These very recent trends may be promoting an increase in the length of nondisabled life as well as total life expectancy. Clearly, there is a need to maintain health and reduce disability at younger ages to have meaningful compression of morbidity across the age range. The trends for the last 40 years do not support projections and policies based on assumptions of a reduced length of disabled life. This demonstrates the value of using health expectancy methods to understand the composite effect of trends in disability and mortality for considering policy changes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by a grant from the US National Institute on Aging (P30- AG17265) and a Special Research Grant by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (H26-Tokubetsu-Shitei-029).

The results of this study were presented at the Annual Meeting of REVES; June 2–4, 2015; Singapore.

We thank Steven Ruggles, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, and Matthew Sobek for developing the database used for the disability trends (Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0; Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2015).

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The study analyzed publicly available data and institutional review board approval was not required.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cai L, Lubitz J. Was there compression of disability for older Americans from 1992 to 2003? Demography. 2007;44(3):479–495. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crimmins E, Saito Y, Ingegneri D. Trends in disability-free life expectancy in the United States, 1970–90. Popul Dev Rev. 1997;23(3):555–572. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crimmins E, Hayward M, Hagedorn A, Saito Y, Brouard N. Change in disability-free life expectancy for Americans 70 years old and older. Demography. 2009;46(3):627–646. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manton K. Changing concepts of morbidity and mortality in the elderly population. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1982;60(2):183–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guralnik J, Fried L, Salive M. Disability as a public health outcome in the aging population. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:25–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fries JF. Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(3):130–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007173030304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruenberg E. The failures of success. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1977;55(1):3–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer M. The rising pandemic of mental disorders and associated chronic diseases and disabilities. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1980;62(S285):382–397. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cambois E, Robine J. An international comparison of trends in disability-free life expectancy. In: Eisen R, Sloan FA, editors. Long-Term Care: Economic Issues And Policy Solutions. 1st ed. Boston, MA: Springer; 1996. pp. 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagger C EHEMU Team. Healthy life expectancy in the EU15. REVES. Available at: http://www.eurohex.eu/pdf/Carol_Budapest.pdf. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- 12.Jagger C, McKee M, Christensen K et al. Mind the gap—reaching the European target of a 2-year increase in healthy life years in the next decade. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(5):829–833. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robine J, Cambois E, Nusselder W, Jeune B, Oyen H, Jagger C. The joint action on healthy life years (JA: EHLEIS) Arch Public Health. 2013;71(1):2. doi: 10.1186/0778-7367-71-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito Y, Robine J, Crimmins E. The methods and materials of health expectancy. Stat J IAOS. 2014;30(3):209–223. doi: 10.3233/SJI-140840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagger C, Matthews R, Matthews F, Robinson T, Robine J, Brayne C. The burden of diseases on disability-free life expectancy in later life. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(4):408–414. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.4.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman V, Spillman B, Andreski P et al. Trends in late-life activity limitations in the United States: an update from five national surveys. Demography. 2013;50(2):661–671. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0167-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seeman T, Merkin S, Crimmins E, Karlamangla A. Disability trends among older Americans: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):100–107. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.157388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crimmins E. Physiological differences across populations reflecting early life and later life nutritional status and later life risk for chronic disease. J Popul Ageing. 2015;8(1–2):51–69. doi: 10.1007/s12062-014-9109-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flegal K, Carroll M, Ogden C, Curtin L. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]