Abstract

Objectives. To review how disasters introduce unique challenges to conducting population-based research and community-based participatory research (CBPR).

Methods. From 2007–2009, we conducted the Head-off Environmental Asthma in Louisiana (HEAL) Study in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in a Gulf Coast community facing an unprecedented triple burden: Katrina’s and other disasters’ impact on the environment and health, historic health disparities, and persistent environmental health threats.

Results. The unique triple burden influenced every research component; still, most existing CBPR principles were applicable, even though full adherence was not always feasible and additional tailored principles govern postdisaster settings.

Conclusions. Even in the most challenging postdisaster conditions, CBPR can be successfully designed, implemented, and disseminated while adhering to scientific rigor.

Natural disasters and other public health emergencies introduce unique challenges to conducting population-based research.1 Overcoming such challenges is essential to obtaining information and data that can be used to enhance our capacity to mitigate the effects of disasters, and thereby improve preparedness and response. Community-based participatory research (CBPR), a collaborative bidirectional approach to research, allows community and academic partnerships to explore and solve complex health problems throughout each step of the research process, all the while emphasizing the unique strengths of each partner.2–4 Lurie et al. recently proposed an integrated approach that gives attention to special needs in the community and suggests CBPR as an appropriate model to consider in postdisaster settings.5

One example of the use of CBPR within a disaster setting is provided by our experience in conducting a study in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which put 80% of the city of New Orleans, Louisiana, under water.6 In some areas of the city, homes, schools, and streets were flooded for at least 4 to 6 weeks, resulting in widespread mold infestation and fear of a number of illnesses, including childhood asthma. Against this backdrop, a diverse partnership, consisting of community leaders, research scientists from academia and private research enterprises, and federal and local governmental partners, carried out the Head-off Environmental Asthma in Louisiana (HEAL) Study from 2007–2009 to answer the affected community’s central health concern: “What will all this mold do to our health, and how can we best address it?” The study examined the relationship between mold and other environmental exposures and asthma morbidity while implementing and testing an asthma counselor intervention among children with asthma in post–Hurricane Katrina New Orleans. To govern the study, we convened a Community Advisory Group (CAG), a Steering Committee (SC) consisting of all study team coinvestigators, and a Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB). Results from home assessments and a successful environmental asthma counselor intervention are reported elsewhere and are summarized in the following paragraph.7–9

HEAL demonstrated that an evidence-based environmental asthma counselor intervention can be implemented in a postdisaster setting to improve asthma management and assess environmental exposures. We used a novel combination of the efficacious National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Consortium (NCICAS) asthma counselor intervention10 and the Inner-City Asthma Study (ICAS) environmental intervention11 to intervene on 182 participants enrolled in the HEAL Study. Postintervention changes in asthma symptoms were consistent with the trials on which HEAL was based (45% reduction in symptoms from baseline to 12 months [P < .001] compared with 35% reduction in NCICAS and 62% reduction in ICAS).8 Baseline characteristics of HEAL participants showed that the majority of participants lived in homes that had some type of damage from Hurricane Katrina (62%; Table 1). However, with the exception of Alternaria found in dust, all other dust and air samples for mold and other allergens showed that homes had lower levels of allergens compared with measurements found in other studies, including pre-Katrina findings.8,11–13 This is likely attributable to extensive remediation taking place after Hurricane Katrina and people moving into cleaner homes.7 In fact, 94% of HEAL families had moved at least once since Katrina, 68% had initiated renovations that continued during the study, and 47% had completed home renovations before enrollment.9

TABLE 1—

Baseline Demographics and Housing Characteristics of Children in the Head-off Environmental Asthma in Louisiana (HEAL) Study: New Orleans, LA, 2006

| Characteristic | % or Mean ±SD (n = 182) |

| Demographics | |

| Male | 54 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African American | 67 |

| Hispanic | 7 |

| White or other | 26 |

| At least 1 household member employed | 91 |

| Household income < $15 000 | 25 |

| At least 1 smoker in household | 32 |

| Total no. of people in household | |

| 2–3 | 29 |

| 4–5 | 57 |

| ≥ 6 | 14 |

| Caretaker married | 54 |

| Caretaker completed high school | 88 |

| Housing | |

| No. of times moved since Katrina | 3.09 ±2.03 |

| Current housing type | |

| Single-family detached house | 64 |

| Multifamily house (duplex, triplex, or row house) | 23 |

| Apartment | 8 |

| Federal Emergency Management Agency trailer | 5 |

| Current housing damage | |

| Flooding only | 23 |

| Roof leak only | 25 |

| Flooding and roof leak | 14 |

| None | 38 |

| Mold air samplinga | |

| Indoor total | 502 |

| Outdoor total | 3958 |

Spores per cubic meter reported as geometric means.

In this article, we describe our experience applying CBPR principles in conducting the study, assess their utility in the context of specific strategies we employed, and thereby provide an important perspective for future environmental public health studies conducted in postdisaster communities. Our experience in conducting the HEAL Study was predicated on tenets similar to those of Lurie et al.5 To our knowledge, no comprehensive assessment has been conducted to systematically examine the utility of specific CBPR principles in a postdisaster context, especially in health-disparate, disaster-prone communities served by a fragile health system.

It should be noted that, although disasters vary widely in terms of their impact on communities, we conducted the HEAL Study in a particularly challenging postdisaster environment. Even prior to Hurricane Katrina, Louisiana ranked at the bottom of most health indicators and social determinants of health.14,15 In addition, according to a 2013 Toxic Release Inventory report, Louisiana ranked sixth in the United States for total onsite releases of chemicals and pollutants.16 Furthermore, Gulf Coast communities continue to face hurricanes, tornados, and technological disasters.17

Figure 1 provides an estimate of the number of Gulf Coast community members affected by disasters since 2005. The impact of disasters on human health can range from property loss (Hurricane Ike) to evacuation (Hurricane Gustav) to lives lost (Hurricane Katrina). The cumulative nature of disasters delays recovery, increases vulnerability, and negatively affects resilience.

FIGURE 1—

Timeline and Magnitude of Gulf Coast Disaster Occurrences, 2005–2013

METHODS

Given the mixed method study design, we adopted validated methods standards.18 Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) describes the methods standards deployed and the accompanying strategy to achieve those standards; many of these pertain to the overall HEAL Study components described extensively in previous publications.7,8,19 Methods most directly applicable to the current investigation are discussed more specifically in the following subsections, in the context of the specific aims outlined in this section.

Aim 1: Identify Strategies to Mitigate Postdisaster Challenges

Given the significant challenges faced by the community and the prevailing distrust and disappointment in “the system,” the study team considered a participatory approach to be a prerequisite for success. Therefore, we engaged the CAG to ensure that community concerns were reflected in both the study design and implementation, and as a critical link between the study and the community.

More broadly, we drew from the 9 basic principles of community participation in research identified by Israel et al.:

recognize community as a unit of identity;

build on strength and resources within the community;

facilitate collaborative, equitable involvement of all partners in all phases of the research;

integrate knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all partners;

promote a colearning and empowering process that attends to social inequalities;

involve a cyclical and iterative process;

address health from both positive and ecological perspectives;

disseminate findings and knowledge to all partners; and

involve a long-term commitment to all partners.2

As we anticipated challenges unique to the postdisaster context or encountered in the course of conducting the study, we developed specific methodological strategies to overcome those, guided by the CAG as well as the SC, DSMB, and other oversight bodies. Where possible, we developed these strategies consistent with these CBPR guiding principles.

Aim 2: Assess the Effectiveness of Identified Strategies

To assess the effectiveness of strategies used to achieve study success based on the postdisaster context, we examined each strategy using a specific evaluation method. These methods generally involved descriptive analyses of study monitoring and tracking data, anonymous feedback from study participants, ongoing staff evaluation and feedback, and review of meeting minutes. To evaluate the effectiveness of design changes discussed in the Results section, we calculated visit activity for the 6-month home evaluation for each 3- to 4-month time period in the HEAL Study. We computed it as the number of 6-month home evaluation visits per 100 children who had been enrolled in the study. We calculated visit activities by parish as the number of days between the baseline and 12-month clinic visits for 139 participants, and compared them by using the t test. We used the χ2 test to compare the rate of missed 12-month clinic visits by parish for all enrolled participants.

Aim 3: Examine the Utility of CBPR Principles

To accomplish this aim, we conducted a gap analysis to ascertain which existing CBPR principles we were able to leverage and the degree of adherence. In addition, we analyzed the influencing factors identified through aim 2 to identify CBPR tenets specifically relevant to postdisaster research.

An important aspect of that analysis was a participant survey distributed at the end of the study.

RESULTS

We characterize the primary challenges, describe associated strategies and the degree of effectiveness we experienced with each, and present the results of our assessment of CBPR utility in the context of each specific aim.

Aim 1: Identify Strategies to Mitigate Postdisaster Challenges

In this section, we describe several fundamental challenges faced by the study, strategies we designed to overcome those challenges, and associated CBPR principles. More data on challenges A through H are provided in Table B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Challenge A: need for rapid startup, informed by local awareness.

Although both the SC and our CAG were able to anticipate many potential difficulties from conducting this study in a postdisaster environment, we knew that it would not be possible to fully anticipate all challenges, nor to address those on an individualized basis. In addition, we needed to accelerate the development and implementation of the study to minimize the time that passed after the introduction of disaster-related exposures and other impacts.

Strategy A: hire local study staff; employ community health workers and others as members of the research team.

CBPR principles 1 and 2 recognize the community as a unit of identity and build on its strengths and resources. With both needs and these principles in mind, the team deliberately employed and embedded local community members into the study as trained community health workers (CHWs), benefiting from their vast knowledge and day-to-day postdisaster experience.

Challenge B: wide variation in recruiting-site capacity and needs.

We conducted study recruitment primarily through local schools.19 In early community meetings, school systems expressed general support for the study but some requested that study personnel carry out all activities, whereas other schools preferred to be trained to conduct study recruitment activities themselves.

Strategy B: tailored recruitment.

Consistent with CBPR principle 2 (“builds on strengths and resources within the community”), we attempted to accommodate each system through tailored recruitment strategies that allowed for a range of levels of involvement, on the part of both school officials and study personnel.

Challenge C: difficulty locating study participants because of higher-than-usual mobility associated with challenging living conditions.

It is important to maintain high retention among participants in any study, to maximize statistical power, and to minimize the potential for bias. Specifically, high retention requires the ability to locate and follow study participants over time. Baseline characteristics of HEAL participants show that most participants lived in homes that had some type of damage from Hurricane Katrina (62%) and that the average participant endured multiple relocations (Table 1).

Strategy C: ongoing tracing and tracking of study population; frequent communication among study team members.

We interspersed regular follow-up steps, including quarterly follow-up telephone calls, with scheduled study visits.19 In addition, preplanned, frequent tracing, including on-the-ground locating by study staff familiar with the area, was an integral component of HEAL’s retention strategy. Built into the study design were extensive repeat telephone calls—often more than 20 attempts at different days and times, including weekends and a reminder call the day of the appointment as well as a phone tree for arranging study appointments with those who were difficult to reach. Likewise, in developing retention strategies, we leveraged the importance of study participants’ relationship with locally familiar study staff, and such discussions were cross- and bidirectional, consistent with CBPR principle 2. Investigators could hear and respond to CHW needs, and CHWs could receive improvement plans to address study implementation challenges.

Challenge D: involvement and interdependence of multiple local institutions.

Engaging local institutions and staff made it necessary to establish strong and effective communication among those institutions.

Strategy D: strong, locally based coordination.

In addition to the involvement of data and administrative coordinating centers, we hired a study coordinator in midstudy who was local to the community and culturally competent but not affiliated with any one local institution, consistent with CBPR principle 3 (“facilitates collaborative, equitable involvement of all partners in all phases of the research”). This person assisted with many aspects of study organization, ensured follow-through, and cultivated cross-communication, all from a perspective of strong familiarity with the community.

Challenge E: addressing community concerns.

Community meetings confirmed the significant concern among residents regarding the environmental consequences of Katrina, and specifically the potential impact on children’s and other family members’ health.

Strategy E: developing robust frequently asked questions (FAQs), intensive staff training, informative reporting.

In response to this concern, we relied on CBPR principle 4 (“integrates knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all partners”). Study staff developed robust FAQs for CHWs serving as study technicians who conducted home environmental assessments, and tailored these fact sheets to inform parents and guardians about common environmental questions and concerns. These experiences informed the development of individualized reports provided to each participant, summarizing and putting in context the measures taken of their home environments.19

Challenge F: participants’ availability for the study affected by competing needs.

Study participants in this postdisaster environment were focused on meeting their own immediate needs, including reconstituting their homes and employment and coping both physically and emotionally in their everyday lives. Participation in the study necessarily took lower priority, reducing participants’ availability to participate in study activities, sometimes on very short notice.

Strategy F: flexibility in study implementation; robust scheduling infrastructure.

Mindful of these challenges and consistent with CBPR principle 6 (“involves a cyclical and iterative process”), the team developed a robust scheduling and rescheduling infrastructure for all study components, both technologically and through training of personnel. For example, in advance of a high rate of cancellations and no-shows for various study activities, the team intentionally overscheduled clinic visits, knowing that the actual volume of participation and work would be less than planned each day.

Challenge G: impact of disaster on turnover among local study staff.

The strategy of engaging local institutions and staff to conduct the study enhanced the team’s ability to anticipate and respond effectively to many challenges facing study participants. However, one consequence of that strategy was higher-than-usual turnover among the study staff themselves, through the disaster’s impact on their own homes, lives, and families.

Strategy G: frequent retraining, shadowing.

Operational plans included retraining for inevitable staff turnover. However, consistent with CBPR principle 6, in the course of conducting the study, retraining sometimes had to be conducted on short notice or had to intensify.

Challenge H: combined impacts on adherence to study design.

The high mobility among study participants, combined with a lack of reliable population data, challenged adherence to certain aspects of the study design. For example, 6-month home evaluations were originally intended to occur after initiating an asthma intervention among study participants in 1 study arm.19 However, participant relocations created a need for repeated baseline home evaluations, affecting the team’s ability to introduce the intervention, all of which delayed 6-month home evaluations. This high mobility among the population also affected the usefulness of the prestudy data on the community, leading to overestimation of the size of the target population and therefore overstatement of the likely study power.

Strategy H: balancing flexibility in study design with ensuring scientific rigor.

Taking CBPR principle 6 (“involves a cyclical and iterative process”) to its logical extreme, we worked with our DSMB and CAG to entertain study design modifications that would accommodate frontline challenges, while ensuring that the study would address many of its original objectives and remain capable of answering the community’s real concerns. Among the protocol adjustments were decoupling the 6-month home evaluation from the introduction of the case management intervention and transitioning from a randomized 2-arm trial to a pre–post intervention design.8

Aim 2: Assess the Effectiveness of Identified Strategies

An assessment of the effectiveness of the strategies deployed and the resulting outcomes is presented here in conjunction with strategies A through H, and in Table C (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Strategy A: hiring study staff from within the community.

The team’s first strategy, to hire study staff from within the community—despite the community’s own real challenge simply to survive—was highly successful. In the post-Katrina setting, it emphasizes the shared fate of postdisaster devastation rather than the traditional geographic location as the unit of identity called for in CBPR principle 1. We used anonymous feedback, collected in a survey at study completion, to assess the success of this strategy; surveys revealed that participants were very satisfied with all aspects of the study measured. For example, on a scale from “very dissatisfied” (1) to “very satisfied” (6), the “professional attitude” of the CHWs rated 6 (mean). Comments from caretakers included appreciation of the respectful staff, flexible visits (location and time), and knowledge gained.

Strategy B: tailored recruitment methods.

Despite the critical involvement of the CAG and our CHWs, the study’s second key strategy, to deploy an institutional-tailored recruitment, delivered only incremental success; the recruitment phase was prolonged and the study population was below that desired for a randomized clinical controlled trial. As depicted in Figure A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), virtually all of the 2821 eligible participants were recruited from the school recruitment letter. An indication of the postdisaster hardship was the inability to recontact 957 participants eligible for a phone screen because of frequent moves attributable to unstable housing, resulting in changes in school enrollment. The significant decrease in eligible participants for the clinical screening (320 eligible out of 1864 phone screened) was because most families with children with moderate to severe asthma evacuated to parts of the country where better health care was available. However, recruitment improved significantly (84 enrolled per 1076 phone screened vs 98 enrolled per 542 phone screened) when we implemented staged strategies; as a result, we were able to change direction in time to continue the study.

Strategy C: ongoing tracing and tracking of study population; frequent communications among study team members.

Retention was equal to that of other inner-city studies (88%).19 Of note is the low loss to follow-up (13 participants by study end), demonstrating the commitment to the study of those enrolled. The strategy of built-in frequent contact between CHW team members and the rest of the study team proved to be a successful method for achieving participant retention. In particular, the number of participants with at least 1 visit overdue by 6 months or more was reduced from 62 to 19 after 4 months of proactive tracking and iterative communication among team members.

Strategy D: strong, locally based coordination.

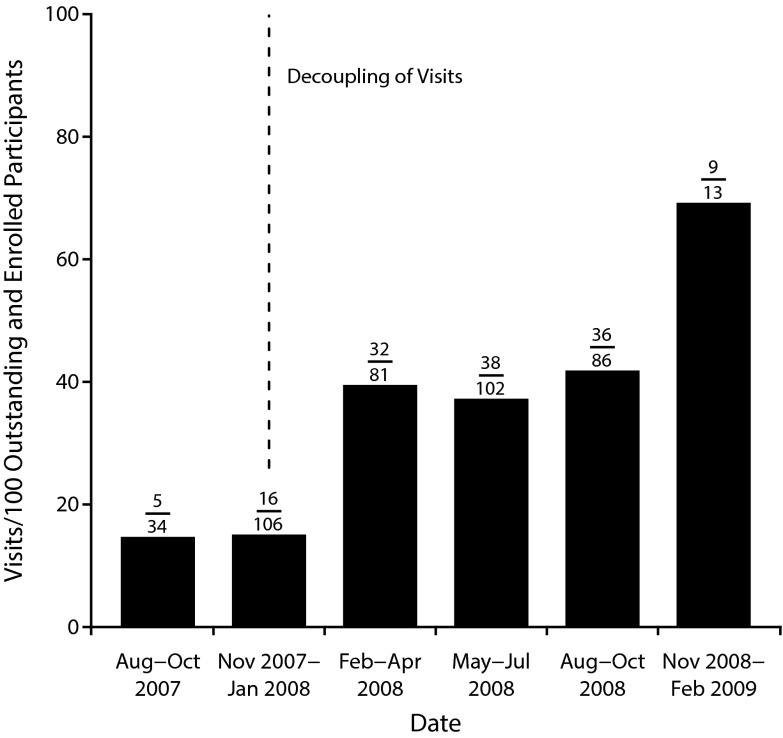

On the basis of ongoing data monitoring and feedback from the data coordinating center and local study institutions, the local study coordinator served as an effective, streamlined point of contact to monitor implementation activities, and was successful in improving communication and coordination among local and remote institutions. Some study personnel attributed the observed improvement in home evaluation activities (Figure 2) in part to the introduction and effectiveness of this position. It should also be noted that there was some initial and ongoing distrust at the local level of this role—for example, with study staff and investigators feeling that they were, in a sense, being evaluated.

FIGURE 2—

Six-Month Home Evaluation Visit Activity in the Head-off Environmental Asthma in Louisiana (HEAL) Study: New Orleans, LA, 2007–2009

Note. The actual fraction for completed versus expected visits is annotated above each bar (i.e., the number of home evaluations performed divided by the total number of participants enrolled during the specified time period). A dashed line indicates a change in the protocol requirement that the 6-month home evaluation had to occur after an asthma counselor visit. After this point, the 6-month home evaluation could occur prior to the asthma counselor intervention. Increased visit activity is observed after the visits were decoupled. Also, the Study Coordinator was hired in October 2007, which may have also led to increased visit activity.

Strategy E: robust FAQs, intensive staff training, informative reporting.

On the basis of verbal feedback from participants and responses to the poststudy completion survey, the home assessments and visits were appreciated by the study participants because this study component answered for them the central community concern. Home evaluators were told by parents and caretakers that they were welcomed into their homes because they were concerned about environmental (mold) exposure after Hurricane Katrina, and this was also demonstrated by the high number of participants agreeing to the environmental assessment in their home.7

Strategy F: flexibility in study implementation; robust scheduling infrastructure.

The robust scheduling infrastructure was generally reasonably successful, albeit extremely resource intensive. For example, note that the lack of resources in the prolonged recovery phase posed proportionally greater postdisaster hardships on Orleans Parish participants than on Jefferson Parish participants, and therefore greater difficulty in adhering to scheduled visits to the study clinic.19 Although the rate of missed 12-month clinic visits was similar for participants from Orleans and Jefferson Parishes, the time between baseline and 12-month clinic visits tended to be longer for Orleans Parish participants, generally reflecting significant rescheduling of visits (Figure 3). Thus, participation among Orleans Parish participants benefited from the extra cushion provided in expanded visit windows in which a study visit could be completed; without these expanded timelines for visits, more of these participants would have been lost. However, expanded nurse staffing (donated to the study) was needed to implement these 12-month clinical evaluations, placing a strain on study resources.

FIGURE 3—

Twelve-Month Clinic Visit Activity in the Head-off Environmental Asthma in Louisiana (HEAL) Study, by Parish: New Orleans, LA, 2007–2009

Note. The time between the 2 visits tended to be longer for Orleans than Jefferson Parish (mean number of days [95% confidence interval] = 408.8 [396.6, 421.1] for Orleans and 385.2 [366.9, 403.4] for Jefferson Parish; P = .03). However, the number of missed 12-month clinic visits was similar between the 2 parishes (26% [33/126] of Orleans Parish and 22% [12/54] of Jefferson Parish had a missed visit). The shaded portion of the box represents the interquartile range. The black line inside the shaded portion indicates the median value. Whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Strategy G: planning for frequent retraining to address high staff turnover.

Training of new study staff required an extraordinary degree of flexibility of trainers who already had a full study workload. Detailed training plans for both retraining of existing staff and training new staff were needed to address the high staff turnover. The most critical assessment of this method’s effectiveness was the evaluation of each trainee’s learning performance to identify gaps in knowledge and skills as well as gaps in the training content based on the trainee’s ability to perform the assigned tasks. In general, the outcome was positive in that we experienced only 1 temporary gap in qualified staffing that affected study schedules. In addition, 4 asthma counselors became certified asthma educators by virtue of their involvement in HEAL.

Strategy H: balancing flexibility in study design with ensuring scientific rigor.

At a high level, the modified study design was essential to enabling continuation of the study at a time when overall participation had been found to be lower than anticipated. As a more specific example, the positive impact of decoupling the environmental assessments from the asthma counselor visit is depicted in Figure 3. Specifically, as a result of the decoupling, we achieved a clear improvement in completion of the home evaluations. Without this flexibility in the study visit structure, participants would have missed their 6-month home evaluation while waiting for their first asthma counselor visit and the home evaluators may not have been able to catch up on the 6-month visits.

Aim 3: Examine the Utility of CBPR Principles

Although the CBPR principles were designed for nondisaster settings, we found that principle 6 (“cyclical and iterative process”) was particularly essential to conducting many aspects of the study, principles 4 (“integrates knowledge and action for mutual benefit”) and 8 (“disseminates findings and knowledge to all partners”) were nearly as critical, and principle 2 (“builds on strength and resources within the community”) was important but both over- and underrealized in different aspects of the study. Adherence to principles 7 and 9 was difficult; for example, addressing all the social determinants of health and disease from an ecological perspective (principle 7) was not feasible given the unprecedented destruction of the physical infrastructure affecting every aspect of the communities’ social fabric. Likewise, securing a “long-term commitment by all parties” (principle 9) beyond asthma would have placed an undue burden on already stressed communities. Finally, principles 1 and 5 were fundamental to the intervention itself, in that we designed the evidence-based intervention for impoverished inner-city populations and the challenges these communities face, empowering participants to address disparities (e.g., housing issues, health care access) and modify behavior.

DISCUSSION

We conducted this poststudy investigation primarily to assess the degree to which CBPR principles can be applied and indeed leveraged in conducting postdisaster research. To our knowledge, this represents one of the first comprehensive assessments to systematically examine the effectiveness of strategies borne of specific CBPR principles in a postdisaster context, especially in a health-disparate, disaster-prone community served by a fragile health care system.

On the basis of our experience, postdisaster health studies aiming to deploy a participatory design can benefit from addressing inherent challenges through the application of several key CBPR principles. Foremost among these is the benefit of implementing a cyclical and iterative process (principle 6), as exemplified by our work in redesigning the study and various components based on a combination of community feedback and operational realities that we encountered. Our work also serves to demonstrate the importance of CBPR principles 4 (“integrates knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all partners”) and 8 (“disseminates findings and knowledge to all partners”) in postdisaster research. In particular, study data combined with feedback from participants served to emphasize the importance of the development and ongoing tailoring of information, as well as collaboration and communication among study partners and the community. For example, reports of the individual home environmental assessments were provided by study personnel to each child’s caretaker; asthma counselors and CHWs then discussed tailored interventions that caretakers could undertake to reduce—and, where possible, eliminate—asthma triggers and other sources of allergens. This collaborative feedback loop mutually benefited participants, the study team, and the study itself.

We found CBPR principle 2 (“builds on strength and resources within the community”) to be very important in some ways and yet problematic in others. The multiple and widely varying study challenges could not have been successfully overcome without leveraging community resources—for example, by hiring study staff locally—nor without the advisement of CAG members. These members included mothers of children with asthma, school principals, pediatricians, environmental justice leaders, faith-based leaders, and local not-for-profit organizations. On the other hand, the benefits of principle 2 were limited in part because of the lack of data on existing assets that could be leveraged. Furthermore, pre-Katrina local data regarding assets were not available to communities, hampering their role as a successful CBPR partner. Such data would have represented pivotal baseline information since the same communities frequently face both natural and technological disasters, as demonstrated by the subsequent Gulf of Mexico oil spill and Hurricane Gustav.17,20 Although existing community resources became more apparent during the later components of the implementation phase, the recruitment efforts could have been accelerated if those assets were available earlier. As a result of Hurricane Katrina and other more recent events such as the Gulf of Mexico oil spill,20 there is a growing body of research focusing on resilience. Although more is known about individual resilience, data on community resilience remains sparse.21 Specifically, postdisaster health studies can build on factors influencing community resilience, while avoiding adding to those that affect vulnerability.

On the basis of the lessons learned through HEAL, postdisaster environmental health studies aiming to deploy a participatory design would benefit from incorporating several key additional CBPR principles: integrating a disaster plan within study design, mapping and taking into account a community’s predisaster resilience or vulnerability, ensuring that the study is informed by a community’s cultural context, and embedding the research into existing community assets.

A central challenge faced by many qualitative studies is quantifying findings. The study team attempted to use Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research, with reasonable success. Key challenges affecting full adherence to all standards18 include an unprecedented postdisaster study setting affecting traditional CBPR strategies and a study population suffering from historic health disparities and living in an environment both physically and psychosocially poor.

Limitations

The postdisaster study implementation and setting resulted in some limitations. For example, prolonged disaster recovery of study participants affected the study timeline, making quantitative assessments of operational effectiveness difficult. We assessed factors influencing adherence to CBPR principles during study implementation and not design, since those factors could not be well characterized in the novel postdisaster setting. From a data analysis perspective, we attempted to quantify results using Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (Table A), but this may not be fully feasible in a postdisaster setting. Furthermore, we did not include measures to assess the quality of the asthma counselor–participant interaction (e.g., STAR assessment22); even if those had been included, high turnover among counselors because of their own postdisaster hardships would have made results less reliable. Despite these limitations, the strategies put in place effectively overcame most study challenges, demonstrating the strength of the community–academic partnership.

Conclusions

Despite doubt among many researchers, it is possible to conduct postdisaster CBPR while adhering both to scientific rigor and “flexibility in action.” As with the disaster management paradigm—prepare, detect, respond, mitigate, recover—postdisaster studies should take a “whole community” approach. However, such a strategy is more viable if public health research and practice investments are made in pre- and interdisaster assessments of assets and vulnerabilities. In disaster-prone communities with a historic burden of health disparities, research associated with natural and technological disaster-related environmental insults pose a complexity of challenges from design to dissemination—and can benefit from the application of CBPR principles tailored to postdisaster settings. One of the key study design challenges is the lack of baseline exposure and population data. Efforts currently under way to develop “shovel-ready” research protocols with preexisting human participant approval provisions, representing “research preparedness,” can capture critical immediate community-specific postdisaster “baseline” data to accommodate not only pre–post disaster comparison but longitudinal cohort studies examining health outcome trends over time. The lessons learned from designing and implementing the HEAL Study affirmed the value of community–academic partnerships and offer new insights into deploying CBPR principles in postdisaster settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by the National Center of Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD, now the NIMHD); the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), National Institutes of Health (NIH; contract NO1-ES-55553); and the Merck Childhood Asthma Network, Inc (MCAN). Public–private funding provided by the NIH and MCAN was managed under the auspices of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. Other organizations that contributed include the National Toxicology Program (NIEHS), the US Environmental Protection Agency (Cincinnati, OH), and the de Laski Family Foundation. The Clinical and Translational Research Center of Tulane and Louisiana State Universities Schools of Medicine was supported in whole or in part by funds provided through the Louisiana Board of Regents RC/EEP.

HEAL was a collaboration of the following institutions, investigators, and staff: Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, M. Lichtveld (PI), F. Grimsley (investigator), L. White (investigator), William Hawkins (program management), Melissa Owsiany (senior program coordinator), S. DeGruy, D. Paul, Natasha Barlow, Nicole Bell, Erica Harris (home evaluators); Tulane University Health Sciences Center, J. El-Dahr (investigator); Tulane University School of Medicine, Maxcie Sikora (physician); Tulane Clinical and Translational Research Center of Tulane and Louisiana State Universities Schools of Medicine, Mary Meyaski-Schluter, Virginia Garrison, Erin Plaia, Annie Stell, Jim Outland, Shanker Japa, Charlotte Marshall (nursing staff); New Orleans Health Department, K. U. Stephens (PI), M. M. Mvula (investigator), S. Denham, M. Sanders, C. Hayes (asthma counselors), Alfreda Porter, Tenaj Hampton, Angela Sarker (community health workers), Mamadou Misbaou Diallo, Shawanda Rogers, David Ali (recruiters), Doryne Sunda-Meya, Ariska Fortenberry (administrative), Florietta M. Stevenson (personnel); Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center School of Nursing, Y. Sterling (investigator); Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Ken Paris (physician); National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, P. Chulada (investigator), W. J. Martin II (PI); Visionary Consulting Partners, LLC, E. Thornton (investigator); Constella Group, LLC, R. Cohn (investigator), K. Bordelon (study coordinator); Rho, Inc, H. Mitchell (PI), S. Kennedy (investigator), John Lim (data manager), Gina Allen (research associate), Jeremy Wildfire (statistician), and R. Z. Krouse (statistician). Merck Childhood Asthma Network, Inc, Floyd J. Malveaux (consultant). In addition, we thank David Schwartz (University of Colorado, past Director of NIEHS at time of HEAL) for his innovative input and willingness to support the project early in the process. We also acknowledge Diana Hamer, PhD, and Christopher Mundorf, PhD, MPH, for their diligent assistance in the review and editing phases of the article.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study received institutional review board approval from the Tulane University Human Research Protection Office, as well as the NIEHS and Louisiana State University institutional review boards.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramson DM, Morse SS, Garrett AL, Redlener I. Public health disaster research: surveying the field, defining its future. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2007;1(1):57–62. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e318065b7e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2001;14(2):182–197. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lurie N, Manolio T, Patterson AP, Collins F, Frieden T. Research as a part of public health emergency response. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1251–1255. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1209510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kates RW, Colten CE, Laska S, Leatherman SP. Reconstruction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: a research perspective. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(40):14653–14660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605726103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimsley L, Chulada PC, Kennedy S et al. Indoor environmental exposures for children with asthma enrolled in the HEAL study, post-Katrina New Orleans. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(11):1600–1606. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell H, Cohn RD, Wildfire J et al. Implementation of evidence-based asthma interventions in post-Katrina New Orleans: The Head-off Environmental Asthma in Louisiana (HEAL) Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(11):1607–1612. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grimsley L, Wildfire J, Lichtveld M et al. Few associations found between mold and other allergen concentrations in the home versus skin sensitivity from children with asthma after hurricane Katrina in the Head-off Environmental Asthma in Louisiana Study. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:427358. doi: 10.1155/2012/427358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans R, Gergen PJ, Mitchell H et al. A randomized clinical trial to reduce asthma morbidity among inner-city children: results of the National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Study. J Pediatr. 1999;135(3):332–338. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan WJ, Crain EF, Gruchalla RS et al. Results of a home-based environmental intervention among urban children with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1068–1080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabito FA, Iqbal S, Holt E, Grimsley LF, Islam TM, Scott SK. Prevalence of indoor allergen exposures among New Orleans children with asthma. J Urban Health. 2007;84(6):782–792. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9216-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abramson DM, Garfield RM. On the edge: children and families displaced by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita face a looming medical and mental health crisis. Columbia University Academic Commons, 2006.

- 15.Early Childhood Risk and Reach in Louisiana: Fall 2012. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University–Tulane Early Childhood Policy and Data Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toxic Releases Inventory. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arosemena FA, Fox L, Lichtveld MY. Reproductive health assessment after disasters: embedding a toolkit within the disaster management workforce to address health inequalities among Gulf-Coast women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):17–28. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chulada PC, Kennedy S, Mvula MM et al. The Head-off Environmental Asthma in Louisiana (HEAL) Study—methods and study population. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(11):1592–1599. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein BD, Osofsky HJ, Lichtveld MY. The Gulf oil spill. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1334–1348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1007197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abramson DM, Grattan LM, Mayer B et al. The Resilience Activation Framework: a conceptual model of how access to social resources promotes adaptation and rapid recovery in post-disaster settings. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2015;42(1):42–57. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9410-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGuire-Snieckus R, McCABE R, Catty J, Hansson L, Priebe S. A new scale to assess the therapeutic relationship in community mental health care: STAR. Psychol Med. 2007;37(1):85–95. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]