Abstract

Objective. To determine whether exchanges of emotional language between health advocacy organizations and social media users predict the spread of posts about autism spectrum disorders (ASDs).

Methods. I created a Facebook application that tracked views of ASD advocacy organizations' posts between July 19, 2011, and December 18, 2012. I evaluated the association between exchanges of emotional language and viral views of posts, controlling for additional characteristics of posts, the organizations that produced them, the social media users who viewed them, and the broader social environment.

Results. Exchanges of emotional language between advocacy organizations and social media users are strongly associated with viral views of posts.

Conclusions. Social media outreach may be more successful if organizations invite emotional dialogue instead of simply conveying information about ASDs. Yet exchanges of angry language may contribute to the viral spread of misinformation, such as the rumor that vaccines cause ASDs.

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) affect 1 in 68 children in the United States—up from 1 in 2500 during the 1960s. More than $241 billion is spent annually on services for this rapidly growing population.1,2 Numerous advocacy organizations work to educate the public about ASDs, raise funds, and lobby for new policies.3–5 Social media sites have become a primary forum for public outreach about ASDs and other public health issues.6–8 According to recent surveys, 97% of advocacy organizations and 74% of all Americans use social media.9,10 These sites are popular because they create the potential for health advocacy campaigns to “go viral,” or inspire large groups of social media users to share advocacy organizations’ messages across their own social networks. Social media are particularly instrumental for public discussion of ASDs because virtual interaction alleviates the social anxiety of many who are on the spectrum and enables broader communities affected by this issue to come together without geographic constraints.11

Yet the rapidly expanding conversation about ASDs on social media faces fierce competition for public attention. The typical social media user views multiple messages from advocacy organizations, friends, family members, colleagues, businesses, celebrities, and other public figures each day. Although a growing number of studies has examined whether social media interventions transform health behaviors in small populations, health communication scholars are only beginning to develop theories of why certain social media posts go viral.6 This lack of research is noteworthy because social media are fundamentally interactive and therefore cannot be analyzed via conventional media theories that posit a 1-way channel between advocacy organizations and their audiences.6,7,12,13

I examined the participatory nature of social media by asking whether exchanges of emotion between advocacy organizations and social media users increase viral views of posts about ASDs. Numerous studies suggest that emotional public health campaigns are more likely to reduce negative health behaviors than are those that employ dispassionate, scientific language.14 So-called fear campaigns, for example, have created substantial shifts in public knowledge about lung cancer, HIV, and many other public health issues by highlighting the grave consequences of negative health behaviors, such as smoking and unprotected sex.15 Emotional appeals have a powerful priming effect on cognitive processes, affect the depth of mental processing, and enhance information recall.16

Parallel literature in sociology and social psychology indicates that the priming effect of emotions on cognitive processes is even more powerful when emotions are exchanged in social settings.17–19 Emotional appeals tend to provoke emotional reactions that amplify the emotional bias of cognitive processes in turn.20 The potential for such emotional feedback is rife in social media sites, which enable the rapid spread of emotional conversations across large populations.

I hypothesized that (1) emotional posts produced by ASD advocacy organizations would provoke emotional comments from their fans—or those who elect to receive regular messages from the organization in their news feed—and (2) these emotional comments would attract viral views—or views of the message by social media users who are friends or followers of those who comment but not the organization that produced the message (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

METHODS

Studying how exchanges of emotion shape viral views of public health messages on social media sites presents several challenges. First, viral social media messages are rare. Failure to situate these messages within the broader population of messages that do not go viral creates selection on the dependent variable. Second, evaluating the theory of emotional feedback requires information about many interactions between advocacy organizations and social media users across time. Third, emotional feedback is only 1 of many factors that may shape virality at multiple levels of analysis—including additional characteristics of social media messages; the organizations that produce them; the social media users who view or comment on them; and broader external factors such as news coverage of an organization.12

The text of all posts and comments on Facebook fan pages that advocacy organizations create for public outreach are publicly available. Yet Facebook Insights data that describe the viral reach of each post—and aggregate characteristics of those who view posts—cannot be accessed without permission from the owner of a fan page. Moreover, these data cannot be used to address many alternative explanations of virality.

To overcome these obstacles, I created a web-based Facebook application called Find Your People. This application offered advocacy organizations a free automated analysis of their social media strategy in return for sharing nonpublic data about their page and completing a brief survey. After I obtained permission from a representative of an advocacy organization, this application

collected the text of all posts and comments from the organization’s fan page,

surveyed the individual who installed the app to evaluate additional characteristics of the organization,

extracted aggregate Insights data,

collected additional information about the organization and aggregate information about its audience from Google, and

generated a report comparing the organization with its peers and providing recommendations about how to optimize its social media outreach.

Because Facebook does not provide a list of advocacy organizations that host fan pages, I identified potential participants using a 3-stage sampling procedure (Figure B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). First, I used a database of government-recognized nonprofit organizations to create a list of all US organizations dedicated to creating awareness about ASDs.21 This database excludes organizations that have not yet registered for this status or cannot afford to do so. Therefore, I used Facebook’s search function to identify all such organizations in the United States (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, describes the 132 organizations identified via these first 2 sampling techniques). Finally, the app-based research design enabled a third stage of respondent-driven sampling to identify additional organizations that were omitted from the first 2 stages of sampling because organizations were encouraged to recruit their peers.

Measures

Viral views.

I used Facebook Insights data to measure the number of unique social media users who viewed an advocacy organization’s post who were not among its fans.

Percentage of emotional language in Facebook posts and comments.

Each row in the data set corresponds to a post produced by an advocacy organization. I used Linguistic Inquiry Word Count software version 2007 (Pennebaker Conglomerates, Austin, TX) to measure the emotional valence of each post, text in images associated with the post, and corresponding comments from Facebook users.22 This software identifies the percentage of words in a document that are associated with positive (joy) or negative (fear, anger, or sadness) emotions. These calculations compare each text to a dictionary of emotional words created by a combination of expert coding and studies wherein individual research participants in more than 28 studies in 3 English-speaking countries were primed with a particular emotion (e.g., sadness) and asked to write diary entries about this feeling. Linguistic Inquiry Word Count has been used in more than 100 studies in public health and other fields.23–25

Nevertheless, this type of dictionary-based approach occasionally fails to recognize that words can assume multiple meanings in different contexts. I therefore compared the Linguistic Inquiry Word Count categorization of the Facebook posts and comments in the sample with those produced by another popular sentiment analysis algorithm.26 The pairwise correlation between these 2 measures was 0.73 (P < .001). I used the Linguistic Inquiry Word Count software to produce a variable that describes the number of unique people who made comments about each post with a percentage of emotional words that was above the sample mean to evaluate hypothesis 1. I created continuous variables that describe the percentage of emotional words in each post and the group of comments it received—if any—to evaluate hypothesis 2.

Post-level controls.

Because audiovisual cues focus public attention, I created a binary indicator to describe whether posts contained images or video.27 Emotional comments or viral views may also be associated with the novelty of an advocacy organization’s post. I created a continuous variable to describe the number of words in each post that were not previously mentioned by any organizations in the study sample. This measure excluded extremely common words (e.g., “and,” “the”) and URLs. Models used to evaluate my second hypothesis included a count of the number of unique people who commented on each post, because such engagement may increase viral views regardless of its emotional valence.

Organizational-level controls.

Previous studies have revealed a very strong correlation between the size of an advocacy organization’s social network and the success of its public outreach.28 The models therefore included a count of the number of people who were fans of each advocacy organization on the day it produced a post. The application’s survey also queried respondents about their organization’s total number of members or volunteers, total yearly budget, and age, because large or well-established organizations may have more financial and social resources to promote the viral diffusion of their posts.29 In addition, the application extracted the number of post views created via Facebook’s own advertising tools: fee-based services designed to promote posts. Finally, the models included a continuous measure of the number of posts each organization made during the previous week.

Audience-level controls.

Previous studies indicate that women are slightly more active social media users than are men—particularly in gendered fields such as public health.10,30 Thus, all models included a variable measuring the percentage of post views by women. I also included a variable measuring the percentage of post views by those younger than 35 years because of the negative correlation between age and frequency of social media use.10 I included additional variables to assess the number of views of each post from 6 US regions because of previous studies indicating that residents in the eastern United States are more active social media users than are those in other regions.31

Broader external environment controls.

Broader external factors, such as news or blog coverage of advocacy organizations, may also provoke viral views.12 I therefore created a variable to count the number of times the name of each advocacy organization appeared in the Google News and Google Blogs databases each day. Emotional comments and viral views may result from the degree of public interest in the subject of autism in an advocacy organization’s locale. Therefore, I used Google Trends data to create a measure of the relative volume of searches for the term “autism” in the state of the organization’s headquarters.

Data Analysis

I performed analyses via the following packages from R software version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria): mice, AER, ICC, MASS, car, lme4, ggplot2, and mediation. I imputed missing data using chained equations with 15 replications. I used quantile–quantile plots to inspect the distribution of the dependent variables used to evaluate hypotheses 1 and 2, which relate to the number of people who made emotional comments about each post and the number of viral views of each post. Although these plots indicated that a Poisson distribution was the best fit for these outcomes, I used negative binomial regression models because of overdispersion. Negative binomial regression models account for the heavy skew of the outcome variable and allow variation in the dispersion parameter in the conditional mean rather than the post-level parameter used by most conditional likelihood fixed-effect models.32

Because of the multilevel structure of the data, I performed diagnostic tests to assess the clustering of error at the organizational level. The intraclass correlation exceeded recommended thresholds, so I used multilevel negative binomial regression models with a logit-link function.33 These models included a random intercept for each advocacy organization and fixed effects for all other variables.34 I performed log transformations on the variables for an organization’s total number of Facebook fans and its annual budget because they were nonnormal and biased model residuals. I divided all continuous measures by 2 times their SE to produce standardized coefficients. I have reported incidence rate ratios that describe the multiplicative effect of a 2 SE increase in emotional language in posts or comments for each outcome controlling for all controls.

Finally, I used mediation analysis to further evaluate hypothesis 2, which suggests that viral views result from amplified emotional bias created by exchanges of emotional language between organizations and their fans. I used the technique of Imai et al. for causal mediation analysis with observational data to estimate the average causal mediation effects of emotional language in posts and comments on viral views, controlling for the other indicators.35 I estimated confidence intervals (CIs) using nonparametric bootstraps with bias-corrected and accelerated intervals.

RESULTS

During November 2012, 42 of the 134 organizations in the target sample installed the application. I deemed 5 additional ASD advocacy organizations recruited via respondent-driven sampling eligible for inclusion, for a cumulative response rate of 33.81%. Because Facebook enables the collection of both retrospective and prospective data, the application obtained information about 8 015 244 views of 7336 posts produced by these 47 organizations between July 19, 2011, and December 18, 2012. The application also collected data on 9680 comments about these posts produced by 3835 social media users during the same period.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the key indicators. As expected, the distribution of unique emotional commenters and viral views was highly skewed. There was no evidence of response bias according to the social media popularity of organizations despite the application’s incentive designed to increase social media engagement (Figure C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The mean percentages of emotional words in each post and in comments to each post were 5.86 and 3.46, respectively. The mean length of posts was 28 words (SD = 46.4).

TABLE 1—

Descriptive Characteristics of Analytical Sample of Facebook Posts, Advocacy Organizations, Social Media Users, and Broader External Factors That Shape Social Media Virality: July 19, 2011–December 18, 2012

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Min | Max |

| Post-level indicators | |||

| Viral views | 31.05 (176.42) | 0.00 | 6 749 |

| No. unique people who made emotional comments about post | 0.25 (1.05) | 0.00 | 36 |

| Emotional language, % | |||

| All | 5.86 (6.65) | 0.00 | 100 |

| Positive | 5.25 (6.45) | 0.00 | 100 |

| Negative | 0.58 (2.09) | 0.00 | 33 |

| Contains audiovisual | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.00 | 1 |

| Novel words in post, % | 0.12 (0.16) | 0.00 | 100 |

| Emotional language in comments about post, % | |||

| All | 3.46 (10.02) | 0.00 | 100 |

| Positive | 3.24 (9.88) | 0.00 | 100 |

| Negative | 0.21 (1.25) | 0.00 | 33 |

| No. people who commented on post | 0.78 (2.49) | 0.00 | 55 |

| Organization-level indicators | |||

| No. Facebook fans | 1 546.73 (2 772.00) | 33.00 | 17 952 |

| No. volunteers or members | 454.11 (2 314.60) | 0.15 | 17 136 |

| Total year-end budget, US$ | 1 644 508.00 (4 813 029.00) | 0.00 | 35 569 996 |

| Age, y | 10.17 (12.97) | 1.00 | 88 |

| No. views from Facebook post advertising | 46.98 (2 621.53) | 0.00 | 212 422 |

| No. posts during previous week | 0.70 (0.50) | 0.08 | 2 |

| Audience-level indicators | |||

| Female post viewers, % | 0.70 (0.11) | 0.15 | 1 |

| Post viewers younger than 35 y, % | 0.46 (0.19) | 0.05 | 100 |

| No. post viewers by US region | |||

| New England | 348.78 (1 109.35) | 0.00 | 11 857 |

| Middle Atlantic | 1 141.59 (2 460.70) | 0.00 | 33 248 |

| East Central | 826.20 (1 474.46) | 0.00 | 12 903 |

| West North Central | 130.59 (390.33) | 0.00 | 5 739 |

| South Atlantic | 26.64 (132.15) | 0.00 | 3 327 |

| West South Central | 564.61 (907.86) | 0.00 | 8 526 |

| No. post viewers outside US | 27.39 (33.42) | 0.00 | 130 |

| Broader external indicators | |||

| No. news articles about organization | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.00 | 2 |

| No. blog mentions about organization | 0.13 (0.42) | 0.00 | 7 |

| Google autism search index | 35.02 (9.53) | 13.00 | 95 |

Note. Table shows data of 7366 Facebook posts produced by 47 advocacy organizations.

Positive emotions were expressed far more commonly than were negative emotions in both posts and comments. The average post contained 5.25% words associated with positive emotions and 0.58% words associated with negative emotions. The average set of comments about a post contained 3.24% words associated with positive emotions and 0.21% words associated with negative emotions. The mean length of comments was 20.83 words (SD = 32.28), 20.00% of posts contained audiovisuals, and the average post contained 12.00% novel words.

Table 1 also presents descriptive statistics for the control variables. A wide variety of ASD advocacy organizations participated in the study. By the end of the study period, the smallest organization had only 33 fans, whereas the largest had 17 952. The sample included organizations with no financial resources and those with annual budgets exceeding $35 million. There was no evidence of response bias according to financial resources even though the application offered a free resource to participating advocacy organizations (Figure D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). There was also no evidence of response bias according to the age of organizations (Figure E, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

On average, 70% of post viewers were female, and 46% were younger than 35 years. Post viewers from the East Coast were slightly more common than were those from other regions. Very few people viewed posts from outside the United States. News and blog coverage of organizations was also very rare. The relative volume of Google searches varied considerably in the states where advocacy organizations were headquartered.

Table 2 presents results from the model designed to evaluate hypothesis 1. This model shows that the percentage of emotional words in each post has a modest significant association with the number of unique people who make emotional comments about the post. A 12% increase in emotional words in a post is associated with a 9% increase in the number of emotional commentators. This effect is far smaller than the association between the outcome and an organization’s number of Facebook fans or the use of audiovisuals in posts. The percentage of novel words in each post and the percentage of post viewers who are female are negatively associated with the number of people who produce emotional comments about each post.

TABLE 2—

Results of Multilevel Negative Binomial Regression Models Predicting Number of Unique Emotional Comments: July 19, 2011–December 18, 2012

| Variable | IRR (95% CI) |

| Post-level indicators | |

| Emotional language in post, % | 1.09 (1.02, 1.17) |

| Contains audiovisuala | 2.59 (2.34, 2.89) |

| Novel words in post, % | 0.87 (0.76, 0.99) |

| Organization-level indicators | |

| No. Facebook fans, log | 10.91 (7.54, 15.64) |

| No. volunteers or members | 0.77 (0.46, 1.28) |

| Total year-end budget, US$, log | 3.22 (0.5, 20.91) |

| Age, y | 0.58 (0.24, 1.39) |

| No. views from Facebook post advertising | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) |

| No. posts during previous week | 1.00 (0.88, 1.13) |

| Audience-level indicators | |

| Female post viewers, % | 0.76 (0.66, 0.86) |

| Post viewers younger than 35 y, % | 1.03 (0.89, 1.19) |

| No. post viewers by US region | |

| New England | 1.01 (0.91, 1.12) |

| Middle Atlantic | 0.96 (0.86, 1.07) |

| East Central | 1.05 (0.89, 1.26) |

| West North Central | 1.14 (0.99, 1.31) |

| South Atlantic | 0.86 (0.72, 1.04) |

| West South Central | 0.96 (0.85, 1.08) |

| Broader external indicators | |

| No. news articles about organization | 1.04 (0.95, 1.14) |

| No. blog mentions about organization | 0.93 (0.85, 1.01) |

| Google autism search index | 0.97 (0.85, 1.11) |

| Organization-level variance | 0.72 |

| Intraclass correlation | 0.18 |

| AIC | 8072.26 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; CI= confidence interval; IRR = incidence rate ratio. The results predicted the number of unique social media users who made emotional comments about Facebook posts produced by autism advocacy organizations. Data are from 7366 Facebook posts produced by 47 advocacy organizations.

1 = yes; 0 = no.

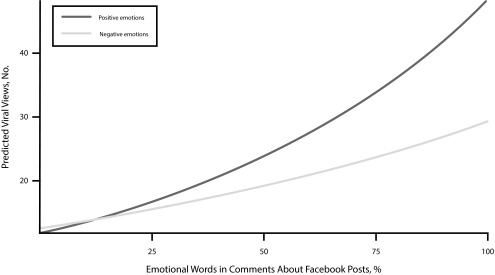

Table 3 presents results from the 3 models used to evaluate hypothesis 2. The first model reports the results for all types of emotional language in comments, the second model reports results for positive emotions, and the third model reports results for negative emotions. The first model reveals that the percentage of emotional words in comments about a post has a strong, significant association with viral views. A 13.3% increase in emotional words in comments about a post was associated with a 34.0% increase in viral views. The second and third models in Table 3 indicate that this association holds for both positive and negative emotional language—although the effect is much stronger for positive than for negative emotional language. Figure 1 illustrates these findings by plotting the predicted number of viral views against the percentage of positive and negative emotional words in comments, with all other variables held at their mean values and without random intercepts for each organization.

TABLE 3—

Results of Multilevel Negative Binomial Regression Models Predicting Viral Views of Facebook Posts Produced by Autism Advocacy Organizations: July 19, 2011–December 18, 2012

| Variable | All Emotions, IRR (95% CI) | Positive Emotions, IRR (95% CI) | Negative Emotions, IRR (95% CI) |

| Post-level Indicators | |||

| All emotional language, % | |||

| In post | 1.04 (1.04, 1.05) | ||

| In comments about post | 1.34 (1.32, 1.34) | ||

| Positive emotional language, % | |||

| In post | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | ||

| In comments about post | 1.32 (1.31, 1.32) | ||

| Negative emotional language, % | |||

| In post | 1.12 (1.11, 1.13) | ||

| In comments about post | 1.06 (1.06, 1.07) | ||

| No. people who commented about post | 1.38 (1.38, 1.39) | 1.38 (1.38, 1.39) | 1.36 (1.36, 1.38) |

| Contains audiovisuala | 2.61 (2.59, 2.64) | 2.61 (2.59, 2.64) | 2.80 (2.77, 2.83) |

| Novel words in post, % | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) |

| Organization-level indicators | |||

| No. Facebook fans, log | 8.50 (8.17, 8.94) | 8.67 (8.33, 9.03) | 9.78 (9.39, 10.18) |

| No. volunteers or members | 0.48 (0.30, 0.76) | 0.48 (0.30, 0.76) | 0.44 (0.27, 0.71) |

| Total year-end budget, US$, log | 3.67 (0.70, 19.11) | 3.67 (0.76, 17.81) | 3.74 (0.77, 18.36) |

| Age, y | 0.64 (0.30, 1.40) | 0.64 (0.31, 1.36) | 0.64 (0.30, 1.36) |

| No. views from Facebook post advertising | 1.05 (1.05, 1.05) | 1.05 (1.05, 1.05) | 1.05 (1.05, 1.05) |

| No. posts during previous week | 1.16 (1.15, 1.17) | 1.16 (1.15, 1.17) | 1.16 (1.15, 1.17) |

| Audience-level indicators | |||

| Female post viewers, % | 1.28 (1.27, 1.31) | 1.28 (1.27, 1.31) | 1.28 (1.26, 1.30) |

| Post viewers younger than 35 y, % | 1.20 (1.17, 1.21) | 1.19 (1.17, 1.21) | 1.16 (1.15, 1.19) |

| No. post viewers by US region, % | |||

| New England | 0.91 (0.90, 0.92) | 0.91 (0.90, 0.92) | 0.93 (0.92, 0.94) |

| Middle Atlantic | 0.85 (0.84, 0.86) | 0.85 (0.84, 0.86) | 0.85 (0.84, 0.86) |

| East Central | 1.12 (1.09, 1.13) | 1.12 (1.09, 1.13) | 1.12 (1.09, 1.14) |

| West North Central | 1.54 (1.52, 1.55) | 1.54 (1.52, 1.55) | 1.60 (1.58, 1.62) |

| South Atlantic | 0.93 (0.92, 0.95) | 0.94 (0.92, 0.95) | 0.94 (0.92, 0.95) |

| West South Central | 1.26 (1.25, 1.27) | 1.26 (1.25, 1.27) | 1.23 (1.22, 1.25) |

| Broader external indicators | |||

| No. news articles about organization | 1.07 (1.07 1.08) | 1.07 (1.07 1.08) | 1.07 (1.06, 1.07) |

| No. blog mentions about organization | 1.13 (1.12 1.14) | 1.13 (1.12 1.14) | 1.13 (1.12, 1.14) |

| Google autism search index | 0.67 (0.66 0.68) | 0.67 (0.66 0.68) | 0.69 (0.68, 0.70) |

| Organization-level variance | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.73 |

| Intraclass correlation | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| AIC | 500162.77 | 500582.30 | 508753.00 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; CI= confidence interval; IRR = incidence rate ratio. Table shows data of 7366 Facebook posts produced by 47 advocacy organizations.

1 = yes; 0 = no.

FIGURE 1—

Predicted Virality of Social Media Posts by Autism Advocacy Organizations: July 19, 2011–December 18, 2012

Note. Predicted virality is according to percentage of words associated with positive and negative emotions in comments about the post, holding control variables at their mean values. Viral views are those by social media users who are not fans or followers of an advocacy organization. I used Linguistic Inquiry Word Count software version 2007 (Pennebaker Conglomerates, Austin, TX) to measure the percentage of words associated with positive (joy) and negative (fear, anger, or sadness) emotions. I did not use organization-level intercepts to calculate predicted values.

As Table 3 shows, all post-level control variables had positive and significant associations with viral views in each model. Among organizational-level variables, organizations’ number of Facebook fans had a very strong and significant association with the outcome. The number of posts organizations made during the previous week and the use of Facebook’s paid post promotion tools also had small correlations with viral views in the 95% CIs. Audience-level controls indicate that the percentage of post viewers who were female and younger than 35 years had a positive association with the outcome, and the number of views from those in central US regions had a modest but significant association with the outcome. News and blog coverage of organizations had a small but significant association with the outcome, but the relative volume of searches for autism in the state of organizations’ headquarters was negatively associated with viral views.

Mediation analysis revealed that emotional comments were largely responsible for the positive effect of emotional posts on viral views described in the 3 models presented in Table 3. The average causal mediation effect for emotional language in comments was 8.24% more viral views (P < .05), whereas the average direct effect of emotional language in posts was not significantly different from 0.

DISCUSSION

Theories of health communication typically describe the flow of messages from the organizations that produce them to their audiences. However, my results indicate that such linear models of health communication are not appropriate for explaining the viral spread of advocacy messages about ASDs on Facebook. Social media sites are fundamentally interactive, and the viral spread of posts requires active participation from social media users.

Although numerous studies indicate that fear-based messages attract more attention than do dispassionate appeals, my results show that exchanges of emotional language between advocacy organizations and social media users—particularly positive emotional language—further increase the virality of advocacy messages. Nonetheless, the size of an ASD organization’s Facebook fan base and the use of audiovisuals in posts had the strongest associations with viral views. Future studies should examine possible interactions between these factors and emotional feedback. For example, exchanges of emotions may become more strongly associated with viral views as the size of social networks increases, and visual cues may encourage more emotional responses than do messages that include only text.

My results have significant implications for future research. First, they suggest that social media campaigns must not simply communicate information or use fear-based tactics to call attention to their claims. Instead, health advocacy organizations may be most successful if they invite positive emotional reactions from social media users. Public health organizations cannot control whether people react to their posts with positive emotional language, but they can take steps to increase the likelihood of positive emotional feedback. Many of the ASD advocacy organizations I analyzed used dispassionate language describing recent advances in complex fields (e.g., epigenetics, neuroscience, virology) or technical details about legal battles for financial resources to support individuals on the spectrum. These types of Facebook posts largely received little or no engagement—perhaps because they encouraged responses only from those with significant knowledge of science or the law.

Instead, ASD advocacy organizations might connect such developments to the emotions they generate among individuals on the spectrum, their families, or the institutions that support them. Public health organizations might also design campaigns that invite positive emotional exchanges. For example, the widely successful Ice Bucket Challenge raised more than $120 million to support research on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by challenging people to douse themselves with freezing water in exchange for monetary donations from Facebook friends.

Second, my results showed that exchanges of negative emotional language between advocacy organizations and social media users—although less common—are also associated with viral views. This finding may help explain how public myths about health conditions such as ASDs persist despite impassioned attempts to discredit them. Emotional or angry denunciations of misinformation—such as the rumor that ASDs result from thimerosal in vaccines—may have unintended consequences. Instead of discrediting false narratives, emotional condemnations by social media users or public health advocacy organizations may inadvertently call further attention to sensational claims. The relative anonymity created by social media may contribute to the viral escalation of emotional feuds between social media users who are otherwise separated by sizable geographic and social chasms. Health organizations should therefore confront emotional posts containing misinformation about health issues with plain facts that do not goad the fear or anxiety of those who may be genuinely upset about the inability of the medical professionals to help them or of bystanders who may sympathize with these feelings.

Limitations

This study has important limitations. The observational and cross-sectional research design prevented analysis of the causal relationship between exchanges of emotional language and viral views. In addition, I did not directly observe emotional bias in cognitive processing. Instead, I assumed social media users who produce or view exchanges of emotional language on social media sites experience a visceral response that focuses their attention on emotional social media messages or comments instead of others. Emotional feedback may have a less powerful effect in online settings because users cannot read nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions and tone, that might contribute to such feelings. However, the very structure of Facebook may generate positive bias because users are encouraged to like one another’s posts.

Positive bias may also exist in social media discourse because users are reluctant to share negative or embarrassing information about themselves in public settings. This may not be true of closed Facebook groups, in which people can view each other’s posts only if they are members—but I did not include these types of pages. Exchanges of emotions in posts or comments about ASDs may also have a strong association with viral views because the issue often generates strong emotions. Finally, it is unclear whether viral views have downstream consequences. Many who are exposed to viral social media posts about public health issues may not approve of them, become more knowledgeable, or transform relevant health behaviors.

Conclusions

Social media sites have become a critical tool for public health outreach because they enable the rapid spread of information across the hundreds of millions who frequent such forums daily. Yet, the interactive nature of these sites means that public reaction to social media posts may be at least as important as the content of posts themselves. Using innovative computational techniques that tracked more than 8 million views of 7336 Facebook messages about ASDs over 1.5 years, this study provides the first analysis, to my knowledge, of how exchanges of emotional language between advocacy organizations and social media users shape the viral diffusion of social media posts.

Future studies should examine whether similar processes can be observed in other health advocacy fields or on different social media sites (e.g., Twitter) and, perhaps most importantly, whether the viral diffusion of social media posts has significant long-term consequences for improving public understanding of health or positive health behaviors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (award 1551476), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Odum Institute at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Linda George, Sarah Gollust, Jim Moody, and Edward Walker provided helpful comments on previous drafts. Nathan Carrol, Jay Thaker, and Raina Sheth assisted with data collection and cleaning.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This project received an exempt determination from the University of Michigan and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill because it did not collect nonpublic information about individual social media users.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 28;63(2):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buescher A, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell D. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):721–728. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker JP. Mercury, vaccines, and autism: one controversy, three histories. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):244–253. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Offit PA. Autism’s False Prophets Bad Science, Risky Medicine, and the Search for a Cure. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K-Y, King M, Bearman PS. Social influence and the autism epidemic. Am J Sociol. 2010;115(5):1387–1434. doi: 10.1086/651448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou WS, Prestin A, Lyons C, Wen K. Web 2.0 for health promotion: reviewing the current evidence. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):e9–e18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lister C, Royne M, Payne HE, Cannon B, Hanson C, Barnes M. The laugh model: reframing and rebranding public health through social media. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2245–2251. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris JK, Moreland-Russell S, Tabak RG, Ruhr LR, Maier RC. Communication about childhood obesity on Twitter. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e62–e69. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes NG. Social Media Usage Now Ubiquitous Among US Top Charities, Ahead of All Other Sectors. Dartmouth, MA: Center for Marketing Research, University of Massachusetts; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pew Research Center. Social media update, 2013. 2013. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/12/30/social-media-update-2013. Accessed March 23, 2016.

- 11.Silverman C. Understanding Autism: Parents, Doctors, and the History of a Disorder. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitzberg BH. Toward a model of meme diffusion (M3D) Commun Theory. 2014;24(3):311–339. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neiger BL, Thackeray R, Wagenen SAV et al. Use of social media in health promotion purposes, key performance indicators, and evaluation metrics. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(2):159–164. doi: 10.1177/1524839911433467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(5):591–615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leshner G, Bolls P, Thomas E. Scare ’em or disgust ’em: the effects of graphic health promotion messages. Health Commun. 2009;24(5):447–458. doi: 10.1080/10410230903023493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledoux J. The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner J, Stets JE. The Sociology of Emotions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. BMJ. 2008;337 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2338. a2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins R. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hallett T. Emotional feedback and amplification in social interaction. Sociol Q. 2003;44(4):705–726. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minkoff D, Aisenbrey S, Agnone J. Organizational diversity in the U.S. advocacy sector. Soc Probl. 2008;55(4):525–548. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tausczik YR, Pennebaker JW. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J Lang Soc Psychol. 2010;29(1):24–54. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pennebaker JW, Mehl MR, Niederhoffer KG. Psychological aspects of natural language use: our words, our selves. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54(1):547–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer ADI, Guillory JE, Hancock JT. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(24):8788–8790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320040111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golder S, Macy M. Diurnal and seasonal mood vary with work, sleep, and daylength across diverse cultures. Science. 2011;333(6051):1878–1881. doi: 10.1126/science.1202775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu B. Sentiment analysis and subjectivity. In: Indurkhya N, Damerau FJ, editors. Handbook of Natural Language Processing. 2nd ed. Boca, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2010. pp. 627–667. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasi IB, Walker E, Johnson J, Tan HF. No fracking way! Documentary film, discursive opportunity, and local opposition against hydraulic fracturing in the United States, 2010–2013. Am Sociol Rev. 2015;80:934–9959. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weng L, Menczer F, Ahn Y-Y. Virality prediction and community structure in social networks. 2013. Available at: http://www.nature.com/articles/srep02522. Accessed December 16, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Andrews K, Caren N. Making the news: movement organizations, media attention, and the public agenda. Am Sociol Rev. 2010;75(6):841–866. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polletta F, Chen PCB. Gender and public talk accounting for women’s variable participation in the public sphere. Sociol Theory. 2013;31(4):291–317. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell L, Frank MR, Harris KD, Dodds PS, Danforth CM. The geography of happiness: connecting twitter sentiment and expression, demographics, and objective characteristics of place. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allison PD, Waterman RP. Fixed-effects negative binomial regression models. Sociol Methodol. 2002;32(1):247–265. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hox J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gelman A, Hill J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imai K, Tingley D, Yamamoto T. Experimental designs for identifying causal mechanisms. JR Stat Soc. 2013;176(1):5–51. [Google Scholar]