Abstract

Background: Flu-like symptoms (FLSs) and injection-site reactions (ISRs) have been reported with interferon beta treatments for multiple sclerosis (MS). We sought to obtain consensus on the characteristics/management of FLSs/ISRs in patients with relapsing-remitting MS based on experiences from the randomized, placebo-controlled ADVANCE study of peginterferon beta-1a.

Methods: ADVANCE investigators with a predefined number of enrolled patients were eligible to participate in a consensus-generating exercise using a modified Delphi method. An independent steering committee oversaw the development of two sequential Delphi questionnaires. An average rating (AR) of 2.7 or more was defined as consensus a priori.

Results: Thirty and 29 investigators (ie, responders) completed questionnaires 1 and 2, respectively, representing 374 patients from ADVANCE. Responders reported that the incidence/duration of FLSs/ISRs in their typical patient generally declined after 3 months of treatment. Responders reached consensus that FLSs typically last up to 24 hours (AR = 3.17) and have mild/moderate effects on activities of daily living (AR = 3.34). Patients should initiate acetaminophen/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment on a scheduled basis (AR = 3.31) and change the timing of injection (AR = 3.28) to manage FLSs. Injection-site rotation/cooling and drug administration at room temperature (all AR ≥ 3.10) were recommended for managing ISRs. Patient education on FLSs/ISRs was advocated before treatment initiation.

Conclusions: Delphi responders agreed on the management strategies for FLSs/ISRs and agreed that patient education is critical to set treatment expectations and promote adherence.

Adherence to multiple sclerosis (MS) disease-modifying therapies, such as interferons, has been linked to improved treatment outcomes and reduced health-care costs.1,2 Reasons for poor patient adherence to prescribed MS therapies include frequency of administration and adverse events, such as flu-like symptoms (FLSs) and injection-site reactions (ISRs), associated with interferon beta treatments.3–8

Peginterferon beta-1a is a pegylated form of interferon beta-1a approved for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS. The safety and efficacy of peginterferon beta-1a 125 μg administered subcutaneously every 2 or 4 weeks was evaluated during the 2-year, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled (year 1 only) ADVANCE study in patients with relapsing-remitting MS.9 Results from year 1 demonstrated that the use of peginterferon beta-1a 125 μg subcutaneously every 2 or 4 weeks significantly reduced the relapse rate, risk of relapse, disability progression, and number of magnetic resonance imaging brain lesions compared with placebo.9 The most common adverse events in ADVANCE were FLSs and ISRs.

Because FLSs and ISRs may lead to reduced adherence and treatment discontinuation,7,8,10 a better understanding of the impact and management of FLSs and ISRs associated with peginterferon beta-1a therapy could promote improved patient adherence and could potentially affect treatment outcomes. The Delphi technique, which is a widely accepted method that uses iterative rounds of questionnaires to build consensus,11 has previously been used to identify practice patterns and obtain recommendations for symptom management in patients with MS.12,13

The objective of this study was to obtain expert consensus on the characteristics, impact, and management of FLSs and ISRs associated with peginterferon beta-1a therapy based on experiences in the ADVANCE study using a modified, two-round, sequential Delphi technique.

Methods

The ADVANCE study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. Approval for the study protocol was obtained from local ethics committees. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before any evaluations were conducted for eligibility. The methods and results of the ADVANCE study have previously been published.9 Briefly, patients aged 18 to 65 years with an Expanded Disability Status Scale score between 0.0 and 5.0 and a confirmed diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS, as defined by the McDonald criteria,14,15 were included in the study. Patients were randomized to receive peginterferon beta-1a 125 μg subcutaneously every 2 or 4 weeks or placebo at 183 sites worldwide.

A steering committee (n = 4) composed of expert MS clinicians with substantial experience with peginterferon beta-1a (JH, DC, SDN, and DH) was responsible for overseeing the development of two questionnaires and provided input into the criteria for investigator participation. ADVANCE investigators involved in direct patient care at a site in the ADVANCE study with a predefined number of patients were offered the opportunity to participate. Because the United States and Western Europe had fewer patients enrolled in ADVANCE but a good geographic representation was desired for this expert panel, the following inclusion criteria were applied: ADVANCE sites with two or more enrolled patients in the United States and Western Europe (France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom) or ten or more patients in the rest of the world.

Both questionnaires were Web-based (http://www.surveymonkey.com), with access provided through an e-mail link. Participants were offered a monetary incentive to complete the survey. The first questionnaire consisted of 150 questions and was designed to help us better understand the frequency, duration, impact, and management of FLSs and ISRs in patients with MS treated with peginterferon beta-1a. Participants were asked to review their clinical findings from the phase 3 trial to accurately respond to all the questions on the questionnaire. Four question formats were used: yes/no, multiple choice, ranking, and open ended. Both qualitative and quantitative techniques were used to analyze the results. For some questions, investigators (ie, responders) were asked to provide responses for two separate periods: 0 to 3 months of treatment (within the first 3 months of treatment) and more than 3 months of treatment.

After completion of questionnaire 1 and analysis of the data, questionnaire 2 was designed to reach consensus on specific issues, clarify best practices, and generate consensus recommendations for the management of these adverse events. Questionnaire 2 consisted of 15 Likert scale questions. The results of questionnaire 1 were summarized and aggregated into a preliminary consensus and presented to responders before each question in questionnaire 2. The steering committee defined consensus a priori as at least 70% agreement for questionnaire 1 (when applicable) and an average rating (AR) of 2.7 or more based on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree) for questionnaire 2.

Results

Responder Demographics

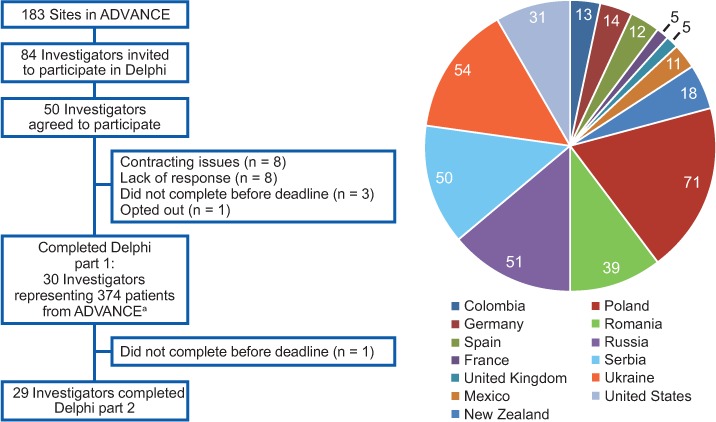

Questionnaire 1 responses were received between February 26 and May 4, 2014, and questionnaire 2 responses between September 15 and October 22, 2014. From the 183 sites that participated in ADVANCE, 84 investigators met the inclusion criteria and were invited to participate. Of 50 ADVANCE investigators who agreed to participate, 30 (ie, responders) completed questionnaire 1 and 29 also completed questionnaire 2 (Figure 1). The 30 responders represented 374 patients in 13 countries; most of the patient population represented came from Poland, Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine (68%). Responders came from academic (50%) and community (50%) settings, and self-identified credentials included physician (83%), doctoral professional (33%), nurse (10%), MS specialist (7%), and other (7%). The average length of time in practice was 20.4 years. Fifty-three percent of the clinical practices focused on MS and 47% on general neurology.

Figure 1.

Survey responder distribution

aThe number of patients from each country is presented in the graph.

Frequency and Duration of FLSs and ISRs

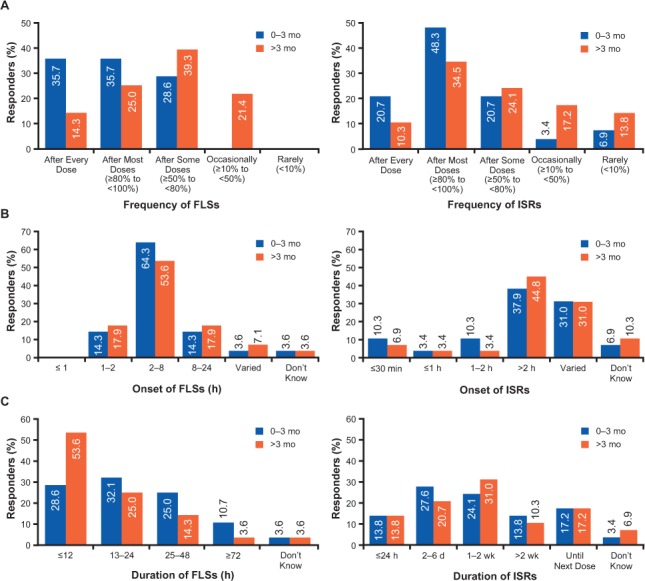

In the first questionnaire, 28 of 30 responders reported FLSs in one or more of their patients. Flu-like symptoms were reported in a typical patient after every dose or most doses by 71% of responders during 0 to 3 months of therapy versus 39% of responders after 3 months of therapy (Figure 2A). As reported by responders, the most prevalent subgroup of FLSs included fever (36% and 21%), chills (21% and 21%), and myalgia (25% and 39%) during 0 to 3 months and after 3 months of treatment, respectively. Most responders (>70%) reported the onset of FLSs to be 1 to 8 hours after dosing during both periods (Figure 2B). The duration of FLSs was reported to be up to 24 hours by 61% of responders during 0 to 3 months of therapy versus 79% after 3 months of therapy (Figure 2C). When asked about sex differences among patients who experience FLSs, 68% of responders reported that there was no difference between men and women, and 25% reported greater FLSs in women. However, additional responses indicated that some responders had enrolled only female patients. On questionnaire 2, all the responders reached consensus (AR ≥ 2.7) that FLSs typically begin within 24 hours after dose administration (AR = 3.72), and most agreed that FLSs typically last 24 hours or less (AR = 3.17). A total of 79% of responders (n = 23) agreed (AR = 2.90) that FLSs may last up to 3 days, with 3% (n = 1) strongly disagreeing with this statement (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Responder-reported frequency (A), onset (B), and duration (C) of flu-like symptoms (FLSs) and injection-site reactions (ISRs)

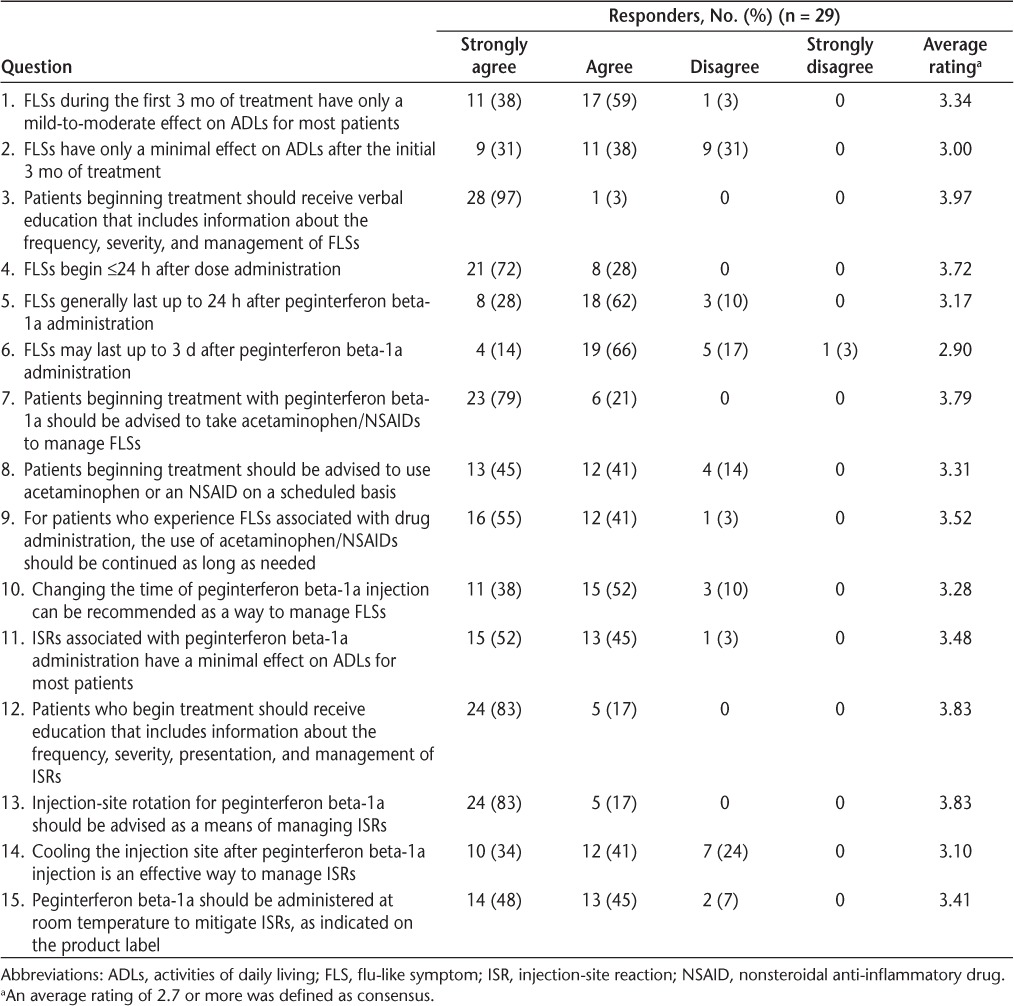

Table 1.

Delphi responder answers to questionnaire 2

In the first questionnaire, 29 of 30 responders reported ISRs in one or more of their patients, with 79% of responders reporting no sex difference and 17% reporting greater ISRs in women. Injection-site reactions were reported in a typical patient after every dose or most doses by 69% of responders during 0 to 3 months of therapy versus 45% after 3 months of therapy (Figure 2A). Erythema (86% and 76%) and pain (3% and 17%) were the most prevalent subgroups of ISR reported by responders during 0 to 3 months and after 3 months of therapy, respectively. Because responses regarding onset and duration of ISRs varied (Figure 2B and C), no follow-up questions were included in questionnaire 2.

Severe FLSs and ISRs

Eleven responders reported severe FLSs and two reported severe ISRs in one or more of their patients during ADVANCE. The severity of FLSs and ISRs with peginterferon beta-1a therapy was reported to be similar to or less severe compared with that of other intramuscular or subcutaneous disease-modifying drugs by more than 52% of responders.

Impact of FLSs and ISRs on Patients' Lives

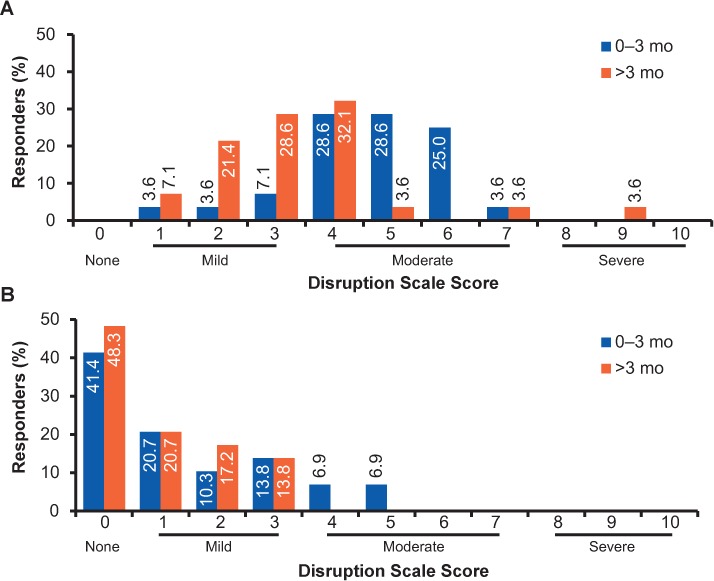

In the first questionnaire, 86% of responders reported that FLSs cause a 4- to 7-point (moderate) disruption in patients' daily activities on a scale from 0 (none) to 10 (severe) during 0 to 3 months, with 89% reporting a 1- to 4-point (mild) disruption after 3 months (Figure 3). In questionnaire 2, responders reached consensus that FLSs have only a mild-to-moderate effect on activities of daily living (ADLs) for most patients during 0 to 3 months of treatment (AR = 3.34) and a minimal effect after 3 months (AR = 3.00). One (3%) and nine (31%) responders, respectively, disagreed with these statements (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Responder-reported impact of flu-like symptoms (A) and injection-site reactions (B) on patients' lives

Responders reported disruption in their typical patients' lives on a scale from 0 (none) to 10 (severe).

Most responders reported that the overall impact of ISRs on patients' daily activities was not substantial; 25 (86%; 0–3 months) and 29 (100%; after 3 months) of 29 responders answered 0 to 3 on a scale from 0 (none) to 10 (severe) on questionnaire 1. A total of 72% of responders reported ISRs in their patients to be similar or less severe compared with standard interferon beta treatments. In questionnaire 2, responders reached the consensus that ISRs have only a minimal effect on ADLs for most patients (AR = 3.48), with one responder disagreeing with this statement (Table 1).

Management of FLSs and ISRs

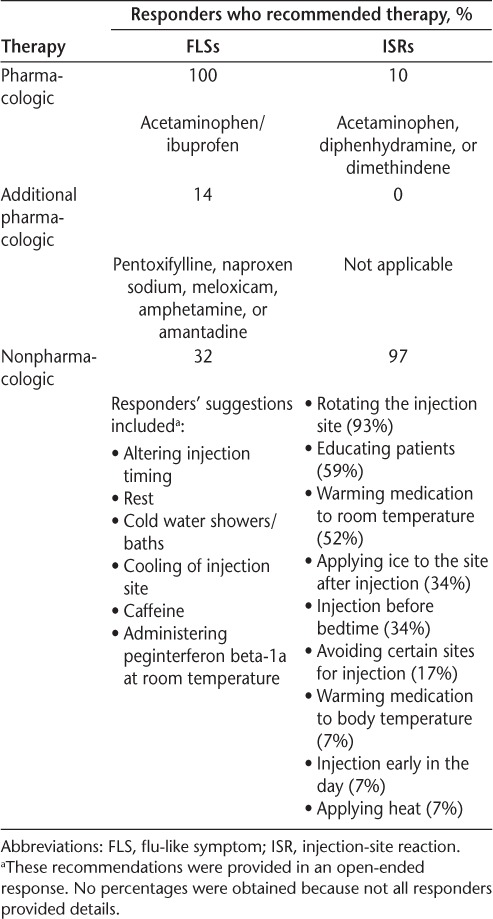

In questionnaire 1, all the responders reported that they recommend or encourage the use of prophylactic therapy to prevent or manage FLSs as recommended in the study protocol: acetaminophen or ibuprofen before each injection and for the 24 hours after each injection, and additional doses as necessary after 24 hours following injection (Table 2). Fourteen percent of responders also reported that they recommended additional pharmacologic therapy (pentoxifylline, naproxen sodium, and meloxicam), and 32% reported that they recommended nonpharmacologic interventions for managing FLSs to their patients. Nonpharmacologic interventions included altering injection timing, rest, cold water showers/baths or cooling of the injection site, caffeine, and administrating peginterferon beta-1a at room temperature. Most responders (57%) reported that their patients did not need additional treatment for FLSs compared with current recommendations for FLSs with standard interferon beta treatments (owing to the question format, no additional details were provided).

Table 2.

Responder-reported management strategies for FLSs and ISRs used in the ADVANCE study

Although only 10% of responders reported that they advised their patients to use pharmacologic therapy (acetaminophen, topical diphenhydramine, and topical dimethindene) to manage ISRs, nearly all (97%) had recommended the use of nonpharmacologic interventions (Table 2). The most commonly advised interventions were rotation of the injection site (93%), patient education (59%), and warming of peginterferon beta-1a to room temperature (52%).

In questionnaire 2, responders reached a consensus on the recommended management strategies for FLSs and ISRs and agreed that patients who begin treatment should be advised to take acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID; AR = 3.79), use it on a scheduled basis (AR = 3.31), and for as long as needed (AR = 3.52) to manage or prevent FLSs (Table 1). Changing the timing of peginterferon beta-1a injection also was recommended as a nonpharmacologic intervention (AR = 3.28). To manage or prevent ISRs, responders agreed that patients should be advised to rotate the injection site (AR = 3.83), cool the injection site after injection (AR = 3.10), and administer peginterferon beta-1a at room temperature (AR = 3.41).

In the first questionnaire, 23 responders indicated that they provided some verbal or written information about FLSs and ISRs to patients before initiating treatment (the remaining responders' answers did not relate to the question). In questionnaire 2, all the responders agreed that patients beginning treatment should be educated about the characteristics and management of FLSs (AR = 3.97) and ISRs (AR = 3.83).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to obtain expert consensus on the characteristics, impact, and management of FLSs and ISRs associated with peginterferon beta-1a therapy based on the investigators' experiences in the ADVANCE study. Both FLSs and ISRs are common adverse events with interferon beta treatments for MS, including peginterferon beta-1a.5,6,9,16 Typically, FLSs occur within 6 hours after injection, dissipate within 24 hours, and are most prevalent during the first 6 months of treatment.10,17,18 Consistent with this and based on the experiences in the ADVANCE study, the frequency and duration of FLSs generally declined after 3 months of treatment in a typical patient treated with peginterferon beta-1a. The responders reached the consensus that FLSs typically begin within 24 hours of drug administration and generally last up to 24 hours. Responders also agreed that for some patients, symptoms may last up to 3 days. However, the possibility of an artifact in the reported 48- to 72-hour duration cannot be ruled out; FLSs that begin in the evening of day 1 and last until the evening of day 2 may be reported to last 48 hours instead of 24 hours. Consequently, one responder (3%) strongly disagreed and five (17%) disagreed that FLSs may last up to 3 days. Because of the question design, it was not clear whether these responders disagreed because they believed that FLSs do not last up to 3 days or because they believed that FLSs may last more than 3 days.

Flu-like symptoms are burdensome and associated with poor treatment adherence and discontinuation of treatment.4,7,8,10 In this study, Delphi responders agreed that for most patients treated with peginterferon beta-1a, FLSs have a mild-to-moderate effect on ADLs during 0 to 3 months of treatment. Consistent with the reduced incidence of FLSs over time, the impact of FLSs on patients' lives seems to decrease and to have only a minimal effect on ADLs after 3 months of treatment.

Several management strategies for FLSs associated with interferon beta treatment have been suggested, including prophylactic over-the-counter (OTC) medications (acetaminophen and/or an NSAID), dose titration, and administration at bedtime.7,18–20 Consequently, scheduled use of acetaminophen and/or an NSAID and changing the timing of injection were recommended as management strategies for FLSs in this study. Because the onset and duration of FLSs are associated with drug administration, the use of OTC medications would be occasional and concurrent with the peginterferon beta-1a therapy administered once every 14 days.

Another adverse event commonly reported in patients with MS treated with injectable interferon betas is ISR, which is generally more frequent with subcutaneous interferon beta therapy than with intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy.5–7,16 As with FLSs, poor treatment adherence and treatment discontinuation also are reported to be associated with ISRs.5–7 In this study, responders reported erythema to be the most common ISR associated with peginterferon beta-1a therapy. The reported incidence, onset, and duration of ISRs varied, and no consensus was obtained on the characteristics of ISRs in patients treated with peginterferon beta-1a. However, most responders (97%) agreed that ISRs generally have only a minimal effect on ADLs.

Several studies have suggested that ISRs can be managed with injection-site practices such as massage, cooling the injection site before or after injection, and pharmacologic therapy, such as diphenhydramine and topical corticosteroids.6,7,18 In the present study, Delphi responders recommended that patients be advised to rotate the injection site, cool the injection site after injection, and administer peginterferon beta-1a at room temperature to manage or prevent ISRs. Pharmacologic therapy (acetaminophen, topical diphenhydramine, or topical dimethindene) was recommended by only a few responders (10%).

All Delphi responders agreed that educating patients about the characteristics and management of FLSs and ISRs before treatment initiation is critical. In previous studies, patient education and counseling was associated with high adherence and low treatment discontinuation due to FLSs and ISRs in patients with MS treated with injectable MS therapies.3 Additionally, setting realistic expectations regarding MS treatment and adverse events was associated with improved adherence.21–23 Because FLSs and ISRs are linked to treatment discontinuation and low adherence in patients with MS, setting realistic treatment expectations is critical and should be done before treatment initiation. Addressing concerns about treatment-related adverse events and educating patients about proper strategies to prevent and manage FLSs and ISRs could lower injection-related fears and treatment anxiety and, thus, increase adherence to peginterferon beta-1a therapy and ultimately improve treatment and patient outcomes.

Limitations of this study include its survey nature and that it asked responders to refer to data collected a few years earlier during a clinical study. In addition, only a limited number of Delphi responders participated in this study, and their observations were based on the number of patients enrolled in a clinical study. These results should be confirmed in clinical practice after gaining more real-world experience with peginterferon beta-1a.

Management of the adverse effects of injectable medications in MS has been well documented in the literature, particularly those encountered with interferon products administered subcutaneously. The present study reinforces the previous literature using a newly approved interferon product with an emphasis on the importance of patient education related to peginterferon beta-1a therapy. Before treatment initiation, it is vital to set realistic expectations regarding treatment and possible adverse events and to highlight the timing and impact of FLSs and ISRs and how these can be reduced and prevented by using OTC medications and other self-care practices. This is the first study to provide consensus agreement on management strategies for FLSs and ISRs associated with peginterferon beta-1a treatment. Overall, these results provide a consensus gained from investigators with substantive experience in MS and may have an effect on patient adherence to peginterferon beta-1a therapy and, ultimately, influence treatment and patient outcomes.

PracticePoints.

The results of this study highlight the importance of educating patients about the characteristics and management of flu-like symptoms and injection-site reactions associated with peginterferon beta-1a therapy.

It is vital that patients have realistic treatment expectations and understand the timing and impact of flu-like symptoms and injection-site reactions and how these adverse events can be reduced and prevented by using over-the-counter medications and other self-care practices.

Overall, these results provide a consensus gained from investigators with substantive experience in MS and may have an effect on patient adherence to therapy and, ultimately, influence treatment outcomes with peginterferon beta-1a.

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial support was provided by Maria Hovenden, PhD (Excel Scientific Solutions, Southport, CT, USA), with funding provided by Biogen (Cambridge, MA, USA). Biogen reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript. The authors had full editorial control of the manuscript and provided their final approval of all content.

Footnotes

From the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, Hackensack, NJ, USA (JH); Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Center, Policlinico Universitario Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy (DC); Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA (SDN); Neurology and Neuroscience Associates Inc, Akron, OH, USA (DH); and Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA (CR, XY, GS, VE, LL).

Financial Disclosures: Ms. Halper has received fees for non–continuing medical education services from Biogen. Dr. Centonze has received speaker/consulting fees and/or research support from Almirall, Bayer Schering, Biogen, Genzyme, GW Pharmaceuticals, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva. Dr. Newsome has participated in scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Genzyme, and Novartis and has received research support from Biogen and Novartis. Dr. Huang has served as a consultant and on advisory boards for Biogen and Teva. Drs. Robertson, You, Sabatella, Evilevitch, and Leahy are full-time employees of Biogen.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by Biogen.

References

- 1.Menzin J, Caon C, Nichols C, White LA, Friedman M, Pill MW. Narrative review of the literature on adherence to disease-modifying therapies among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(suppl A):S24–S40. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.s1.S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg SC, Faris RJ, Chang CF, Chan A, Tankersley MA. Impact of adherence to interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a non-experimental, retrospective, cohort study. Clin Drug Investig. 2010;30:89–100. doi: 10.2165/11533330-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caon C, Saunders C, Smrtka J, Baxter N, Shoemaker J. Injectable disease-modifying therapy for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a review of adherence data. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;42(suppl):S5–S9. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0b013e3181ee1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Rourke KE, Hutchinson M. Stopping beta-interferon therapy in multiple sclerosis: an analysis of stopping patterns. Mult Scler. 2005;11:46–50. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1131oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beer K, Müller M, Hew-Winzeler AM et al. The prevalence of injection-site reactions with disease-modifying therapies and their effect on adherence in patients with multiple sclerosis: an observational study. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart TM, Tran ZV. Injectable multiple sclerosis medications: a patient survey of factors associated with injection-site reactions. Int J MS Care. 2012;14:46–53. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073-14.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costello K, Kennedy P, Scanzillo J. Recognizing nonadherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol. 2009;256:568–576. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0096-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calabresi PA, Kieseier BC, Arnold DL. Pegylated interferon beta-1a for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (ADVANCE): a randomised, phase 3, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:657–665. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70068-7. et al; ADVANCE Study Investigators. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohr DC, Likosky W, Boudewyn AC et al. Side effect profile and adherence to in the treatment of multiple sclerosis with interferon beta-1a. Mult Scler. 1998;4:487–489. doi: 10.1177/135245859800400605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips JT, Hutchinson M, Fox R, Gold R, Havrdova E. Managing flushing and gastrointestinal events associated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate: experiences of an international panel. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan O, Miller AE, Tornatore C, Phillips JT, Barnes CJ. Practice patterns of US neurologists in patients with SPMS and PPMS: a consensus study. Neurol Clin Pract. 2012;2:58–66. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0b013e31824cb0ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the international panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:121–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria.”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840–846. doi: 10.1002/ana.20703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balak DM, Hengstman GJ, Çakmak A, Thio HB. Cutaneous adverse events associated with disease-modifying treatment in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1705–1717. doi: 10.1177/1352458512438239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munschauer FE, III, Kinkel RP. Managing side effects of interferon-beta in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Clin Ther. 1997;19:883–893. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calabresi PA. Considerations in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2002;58(suppl 4):S10–S22. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.8_suppl_4.s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langer-Gould A, Moses HH, Murray TJ. Strategies for managing the side effects of treatments for multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63(suppl 5):S35–S41. doi: 10.1212/wnl.63.11_suppl_5.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandes DW, Bigley K, Hornstein W, Cohen H, Au W, Shubin R. Alleviating flu-like symptoms with dose titration and analgesics in MS patients on intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy: a pilot study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:1667–1672. doi: 10.1185/030079907x210741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Likosky W, Levine E, Goodkin DE. Injectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self-inject. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:125–132. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2302_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W et al. Therapeutic expectations of patients with multiple sclerosis upon initiating interferon beta-1b: relationship to adherence to treatment. Mult Scler. 1996;2:222–226. doi: 10.1177/135245859600200502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandes DW, Callender T, Lathi E, O'Leary S. A review of disease-modifying therapies for MS: maximizing adherence and minimizing adverse events. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:77–92. doi: 10.1185/03007990802569455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]