Abstract

Study design

Systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCT).

Objectives

To examine the effects of a therapeutic home exercise program (HEP) for patients with neck pain (associated with whiplash, non-specific, or specific neck pain, with or without radiculopathy, or cervicogenic headache) on pain, function, and disability. Our secondary aim was to describe the design, dosage, and adherence of the prescribed HEPs.

Background

Neck pain is a leading cause of disability that affects 22–70% of the population. Different techniques have been found effective for the treatment of neck pain. However, there is conflicting evidence to support the role of a therapeutic HEP to reduce pain, disability, and improve function and quality of life (QOL).

Methods

A systematic review in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement for reporting systematic reviews. The full-text review utilized the Maastricht–Amsterdam assessment tool to assess quality among RCTs.

Results

A total of 1927 subjects included within seven full-text articles met our specific search strategy. It was found that HEPs with a focus on strength and endurance-training exercises, as well as self- mobilization, have a positive effect when used in combination with other conservative treatments or alone.

Conclusions

Home exercise programs that utilize either self-mobilizations within an augmented HEP to address specific spinal levels, or strengthening, and/or endurance exercise are effective at reducing neck pain, function, and disability and improving QOL. The benefit of HEPs in combination with other conservative interventions yields some benefit with a range of effect sizes.

Keywords: Neck pain, Non-specific neck pain, Home exercise program, Outcomes, Systematic review

Introduction

Neck pain is one of the leading causes of disability in the United States.1,2 Neck pain may be mechanical in nature and associated with degenerative process or other pathology identified during diagnostic imaging.2 Non-specific neck pain is more common, and the pathoanatomical cause of it is unknown.2 Neck pain may be present with or without whiplash, radiculopathy, or cervicogenic headache.3 The life- time prevalence of this condition ranges between 22 and 70% of the population and increases with age and female gender.3 The acuity of its clinical presentation may also vary and impact the patient’s level of pain, function, and disability. Acute neck pain com- prises 10–20% of the cases seen in physical therapy clinics.2,4−6 The literature shows that 54% of the population reports having an incident of neck pain; 37% of those develop chronic neck pain that limits function and reduces work capabilities.2,4−7

There are a variety of approaches that have been found to be effective for the treatment of neck pain. These treatment strategies include modalities, manual therapy, strength training, endurance training, and home exercise programs (HEPs).6,8−10 Home exercise programs have been used to extend clinically based physical therapy approaches with the treatment of neck pain; however, the influence of a home exercise prescription is widely understudied for musculoske- letal conditions. The evidence that exists is mixed regarding the effect of HEPs to reduce disability and improve the patient’s function and QOL.8,9 This discrepancy may result from variations in the HEP design, aim (i.e. Active Range Of Motion (AROM), stretching, strengthening, etc.), and/or dosage.11 To date, no systematic review has synthesized the impact of HEPs, when used alone or combined with clinical treatment, on specific outcomes such as pain and/or disability. Additionally, minimal attention has been given to the HEP design, aim, and dosage for patients with neck pain.

The primary objective of this systematic review is to examine the effects of adding a therapeutic HEP in the management of patients with neck pain (asso- ciated with whiplash, non-specific or specific neck pain, with or without radiculopathy, or cervicogenic headache) on pain, function, and disability compared to other conservative treatment measures and/or a placebo. As a secondary purpose, the design, aim, dosage, and adherence to HEPs included in these studies will be described.

Methods

Study design

A systematic review conducted at Walsh University was completed in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta- analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting systematic reviews.12 To improve the ‘transparency and scientific merit’ of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, PRISMA was followed using a 27-item checklist.13

Search strategy

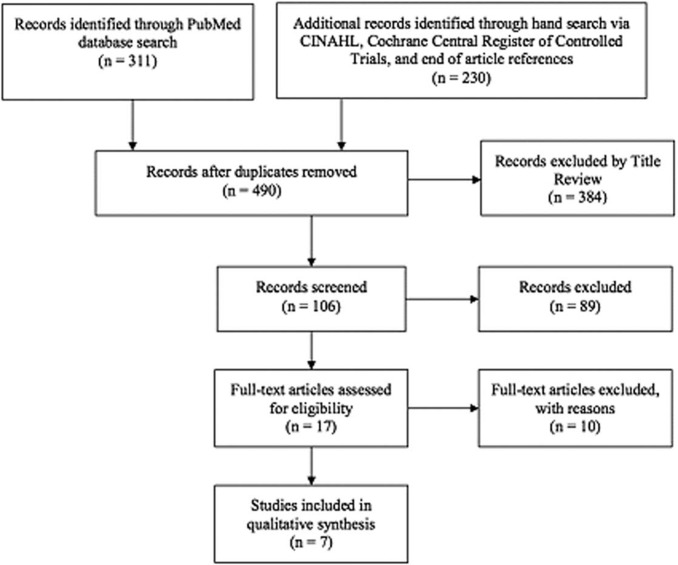

A comprehensive search was performed by two reviewers (HS and MZ) using the following electronic databases: PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Control Trials, CINAHL, and SPORTDiscus. The search strategy included both MeSH terms (Table 1) and keyword searches, as well as a combination of both, for a sensitive and specific search strategy. An outline of the systematic review process can be viewed in Fig. 1. Filters were utilized in order to refine the search for randomized control trials and articles written in English. Subsequent hand searches were completed and terminated on 4 February 2013.

Table 1.

MeSH terms

| MeSH terms |

|---|

| Neck pain |

| Neck pain* |

| Neck muscle |

| Neck muscle* |

| Cervical radiculopathy |

| Radiculopathy |

| Cervical vertebrae |

| Post-traumatic headache Post-traumatic headache* |

| Cervicalgia* |

| Neckache* |

| Neck muscles* and injury* or pain or ache* |

| Cervicogenic headache |

| Home exercise* |

| Muscle stretching exercise* |

| Exercise therapy |

| Exercise movement technique* |

| Exercise program* |

| Strength training Home |

| Home bas* |

| Physical activity |

Indicates a truncation character that encompasses all derivations of the word stem.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of retrieved, screened, and included studies.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion of articles for this systematic review needed to meet the following criteria:

it must be a RCT or randomized clinical trial;

it must include patients with neck pain for any duration;

it must include patients with neck pain with or without headache and/or whiplash and/or radiculopathy;

it must provide a HEP with or without co- interventions and/or control;

it must give an adequate description of the HEP intervention to allow for analysis;

it must provide statistical reporting of the outcome measures;

it must be available in English;

it must have utilized at least one or more validated outcome measures on the constructs of pain, disability, quality of life (QOL), return to work, and/or sick leave.

Studies were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria or were determined to have poor methodological quality (below our pre-determined cut-off point of 50% on the Maastricht–Amsterdam checklist).14

Study selection and data collection

All of the studies were independently reviewed for their compliance with the inclusion criteria. Two reviewers screened the titles (HS and MZ), abstracts (HS and JN), and full text (JN and MZ). Any disagreements were mediated by the third reviewer not involved in the specific search (HS, JN, or MZ). All three reviewers independently reviewed the full- text articles for quality standards. Kappa values were calculated for agreement measures.

Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated in order to determine whether there was a significant difference between two interventions. The calculations of the effect sizes were performed by one author (MZ) through the use of the mean and standard deviations provided in the articles. Two authors (HS and JN) reviewed the completed calculations.

Statistical analysis and quality assessment

Cohen’s kappa of agreement is a statistical analysis utilized to measure the inter-rater agreement for qualitative items including review of the titles, abstracts, and full-text articles.14 The kappa inter- rater agreement was performed between two raters who identified articles as ‘yes’ or ‘no’ for acceptance in this review. Overall, results were compared using the kappa formula: Kappa5Pr(a)2Pre(e)/12Pre(e), where Pr(a) was the relative observed agreement among raters and Pr(e) equaled the hypothetical probability of chance agreement.15

Cohen’s d effect size measurement was used to determine treatment effect in terms of the interven- tions’ influence on pain, disability, and functional outcome measures. This was calculated from the follow-up mean and standard deviation for behavior modifiers (Table 2). Cohen established an effect size of 0.0–0.19 as trivial, 0.20–0.49 as small, 0.50–0.79 as moderate, and more than 0.80 as a large effect size.22

Table 2.

Intervention groups compared with Cohen’s d

| Author | Groups compared | Outcome measure | Group with larger effect at end follow-up | Cohen’s d at endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen et al.16 | HEP 2 minutes vs control | VAS | HEP | 0.67 |

| HEP 12 minutes vs control | VAS | HEP | 0.59 | |

| HEP 12 minutes vs HEP 2 minutes | VAS | Same | 0.00 | |

| Bronfort et al.17 | HEP vs medication | Pain Scale | HEP | 0.11 |

| HEP vs SMT | Pain Scale | HEP | 0.16 | |

| Hall et al.18 | Augmented HEP vs sham mobilization | HA Severity Index | Augmented HEP | 1.79 |

| Kuijper et al.19 | Physiotherapy (PT) with | VAS | PT with HEP | 0.47 |

| HEP vs control | NDI | PT with HEP | 0.11 | |

| PT with HEP vs cervical | VAS | Cervical collar | 0.18 | |

| collar | NDI | Cervical collar | 0.10 | |

| Mongini et al.20 | HEP vs control | Days with HA (mean) | HEP | 0.27 |

| Headache Index (Fxl) | HEP | 0.26 | ||

| Days with neck/shoulder | HEP | 0.29 | ||

| pain (mean) | ||||

| Neck/Shoulder Pain Index (Fxl) | HEP | 0.33 | ||

| Nikander et al.11 | HEP endurance vs control | VAS | HEP | 0.84 |

| DI | HEP | 0.63 | ||

| HEP strength vs control | VAS | HEP | 1.07 | |

| DI | HEP | 0.96 | ||

| HEP strength vs HEP | VAS | Strength | 0.23 | |

| endurance | DI | N/A | 0.27 | |

| Salo et al.21 | HEP endurance vs control | HRQoL | HEP | N/A |

| HEP strength vs control | HRQoL | HEP | N/A | |

| HEP strength vs HEP | HRQoL | Strength | N/A | |

| endurance |

HEP=home exercise program, VAS=Visual Analogue Scale, NDI=Neck Disability Index, DI=Disability Index, HRQoL=Health-Related

Quality of Life, HA=headache, SMT=Spinal Manipulation Therapy, N/A=not available.

Effect size ranges: 0.0–0.19 (trivial), 0.20–0.49 (small), 0.50–0.79 (moderate), and >0.80 (large).22

The quality of each selected full-text article was assessed using the Maastricht–Amsterdam list (Table 3) for RCTs. This specific tool uses 19 items to collectively produce a total quality score with criteria including patient selection, intervention, outcome measurement, and statistics.14 In particular, this tool has strong face and content validity, as well as reproducibility (agreement/reliability).27 Based on the application of this tool in the current literature, previous researchers determined the cut-off percentage values as, <50% indicating poor quality, 50–80% indicating moderate quality, and >80% indicating good quality.23−26

Table 3.

Quality assessment of randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

| Criteria | Andersen et al.16 | Bronfort et al.17 | Hall et al.18 | Kuijper et al.19 | Mongini et al.20 | Nikander et al.11 | Salo et al.21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | |||||||

| A: Were the eligibility criteria specified | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| B1: Was a method of randomization performed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| B2: Was the treatment allocation concealed | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| C: Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Intervention | |||||||

| D: Were the index and control interventions explicitly described | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| E: Was the care provider blinded to the intervention | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| F: Were co-interventions avoided or comparable | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| G: Was the compliance acceptable in all groups | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| H: Was the patient blinded to intervention | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Outcome measurement | |||||||

| I: Was the outcome assessor blinded to the intervention | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| J: Were the outcome measures relevant | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| K: Were adverse effects described | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| L: Was the withdrawal/drop-out rate described and acceptable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| M1: Was a short-term follow-up measurement performed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| M2: Was a long-term follow-up measurement performed | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| N: Was the timing of the outcome measurement in both groups comparable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Statistics | |||||||

| O: Was the sample size for each group described | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| P: Did the analysis include an intention-to-treat analysis | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Q: Were point estimates and measures of variability presented for the primary outcome measures | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Total quality score | 16/19 | 16/19 | 13/19 | 12/19 | 10/19 | 12/19 | 12/19 |

| (84%) | (84%) | (68%) | (63%) | (53%) | (63%) | (63%) |

Results

Search results

The search strategy (using MeSH terms and keywords) through the large electronic database search yielded a total of 311 viable citations. The hand- search strategy revealed 230 additional studies. After removal of duplicate manuscripts, 490 studies remained for review. Of these, 473 studies were excluded based on the title and abstract review, leaving 17 for full-text review. The full text of the 17 remaining studies was retrieved and reviewed for inclusion. The PRISMA flow chart of this process is shown in Fig. 1. Ten studies were excluded based on the absence of a comparison group, lack of an exercise prescription, exercises not home or work based, and/or a poor quality assessment score. See Table 4 for excluded articles and the rationale for exclusion. The seven studies met all the inclusion criteria. All selected studies compared a HEP to a separate intervention and/or a control group defined by the authors.

Table 4.

Excluded articles and rationale for exclusion

| Author title | Exclusion rationale |

|---|---|

| Bronfort G, Evans R, Nelson B, Aker PD, Goldsmith CH, Vernon H | No home- or work-based exercises |

| A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of exercise for patients with chronic neck pain | |

| Marangoni AH | Lack of detail for exercises |

| Effects of intermittent stretching exercises at work on musculoskeletal pain | Poor quality measure |

| associated with the use of a personal computer and the influence of media on outcomes | |

| Andersen LL, Mortensen OS, Zebis MK, Jensen RH, Poulsen OM | No explanation of exercises |

| Effect of brief daily exercise on headache among adults – secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial | |

| Bernaards CM, Ariëns GA, Knol DL, Hildebrandt VH | No explanation of exercises |

| The effectiveness of a work style intervention and a lifestyle physical activity intervention on the recovery from neck and upper limb symptoms in computer workers | No formal HEP intervention |

| Bronfort G, Evans R, Nelson B, Aker PD, Goldsmith CH, Vernon H | No explanation of exercises |

| A randomized clinical trial of exercise and spinal manipulation for patients with chronic | Focus was more on inhouse exercise |

| neck pain | No control |

| Dellve L, Ahlstrom L, Jonsson A, Sandsjö L, Forsman M, Lindegård A, Ahlstrand C, | No home or work exercise |

| Kadefors R, Hagberg M | No explanation of interventions |

| Myofeedback training and intensive muscular strength training to decrease pain and improve work ability among female workers on long-term sick leave with neck pain: a randomized controlled trial | |

| Häkkinen A, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, Ylinen J | No home or work exercise |

| Strength training and stretching verses stretching only in the treatment of patients with chronic neck pain: a randomized one-year follow-up study | No control group |

| Maiers MJ, Hartvigsen J, Schulz C, Schulz K, Evans RL, Bronfort G | No home or work exercise |

| Chiropractic and exercise for seniors with low back pain or neck pain: the design of two randomized clinical trials | No control group |

| Martel J, Dugas C, Dubois JD, Descarreaux M | No description of exercises |

| A randomised controlled trial of preventive spinal manipulation with and without a home exercise program for patients with chronic neck pain | |

| Taimela S, Takala EP, Asklöf T, Seppälä K, Parviainen S | No home or work exercises |

| Active treatment of chronic neck pain | No description of exercises |

Kappa values calculated for the systematic review include 0.62 (95% CI 0.52–0.71) for the titles search, 0.33 (95% CI 0.12–0.54) for abstracts prior to mediation/discussion for inclusion and 1.00 after mediation, and 0.77 (95% CI 0.47–1.06) for full-text inclusion. Within the hand search, the kappa values for the abstracts were 0.40 (95% CI 0.02–0.78) and 1.00 for full text (full agreement). A population, interven- tion, comparison, outcomes and study (PICOS) design table was completed to describe the details of the final full-text articles in order to synthesize the information and compare home exercise interventions and their effectiveness (Table 5).

Table 5.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Reported outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen et al.16 RCT | 198 participants (174 women, 24 men) | HEP only: shoulder abduction (lateral raise), exercise to target perceived, ‘relevant neck and shoulder muscles’ 5 times per week During weeks 1–2, participants used moderate resistance training with elastic tubing. During weeks 2–4, participants progressed to higher level of resistance | Control group=weekly educational emails containing information including general health and physical activity. Internet links regarding this information were also provided | Clinically relevant reductions in pain and tenderness as well as muscle strength increases were found in approximately half of the participants of the training groups As little as 2 minutes of daily progressive resistance training for 10 weeks results in clinically relevant reductions of pain and tenderness and increased muscles strength in adults with frequent neck/shoulder symptoms |

| Mean age: | 12-minute group: | |||

| 2-minute group: 44 (±11) | Weeks 1–2=5–6 sets of 8–12 repetitions | |||

| 12 minute group: 42 (±11) control group: 43 (±10) | Weeks 2–4=6 sets of 12 repetitions 2-minute group: | |||

| Chronic neck pain with/or without shoulder pain for the previous 3 months lasting at least 30 days within 1 year28,29 | Weeks 1–2=single set until failure or until 2 minutes | |||

| Weeks 2–4=increased resistance band | ||||

| Bronfort et al.17 RCT | 272 patients; aged 18–65 years old | Within clinic treatment of spinal thrust/ non-thrust decided by the provider group lasting 15–20 minutes | Home exercise with advice (HEA): instructional 1-hour sessions (×2) | SMT had statistically significant advantage over medication at 26 weeks. No important differences in pain were found between SMT and HEA at any time point |

| Mean age: | ||||

| SMT group: 48.3 (±15.2) | placed 1–2 weeks apart for home exercise of ‘self-mobilization’ of gentle controlled general movements of neck retraction, extension, flexion, rotation, lateral bending motions, and scapular retraction (with no resistance) | |||

| Med group: 46.8 (±12.2) | 5–10 repetitions of each exercise up to 6–8 times per day | |||

| HEA group: 48.6 (±12.5) | Medication group: | |||

| Sub-acute non-specific neck pain for 2–12 weeks28,29 | visits lasted 15–20 minutes. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or both. Participants who did not respond to or could not tolerate drugs received narcotic medications or muscle relaxants | |||

| Hall et al.18 RCT | 32 subjects, mean±SD age, 36±3 years Chronic cervicogenic headache (CHA) for past 3 months28,29 | HEP only: | The control group was involved in a sham self-mobilization at C1–C2 using the cervical self-SNAG strap | C1–C2 self-SNAG reduced cervicogenic headache symptoms on the headache severity index over 1 year compared to the control group |

| The experimental group: C1–C2 self-SNAG. Position held for 3 seconds, 2 repetitions of the exercise, twice daily for 12 months | The strap was positioned in the same way at the experimental group, but the subject did not turn their head when they applied the 3-second sustained forward pressure at C1 | |||

| Kuijper et al.19 RCT | 205 patients, ages 18–75 years | Cervical collar group: | Control group: patients were advised to continue daily activities and document their normal routine | Treatment with a cervical collar plus rest or PT plus home exercises resulted in a statistically significant reduction of arm and neck pain compared to the control group |

| Mean age: collar group: 47 (±9.1) |

semi-hard collar throughout the day for 3 weeks | With the control group, disability index score improved by 9 points on the neck disability | ||

| PT: 46.7 (±10.9) | Weeks 3–6=patients were weaned from the collar until week 6 where they were advised to terminate the use of the collar Physiotherapy with HEP | Both the cervical collar and the PT groups disability index score improved by 14 points | ||

| control: 47.7 (±10.6) | Physiotherapy group: | |||

| Acute/sub-acute cervical radiculopathy, <1 month in duration28,29 | clinical treatment of deep and | |||

| superficial neck muscle exercises twice | ||||

| a week for 6 weeks in duration | ||||

| HEP: isometric and chin retraction exercises, 2 sets of 10 repetitions | ||||

| Mongini et al.20 RCT | 1040 participants between 43 and 52 | HEP only | Control group: one-month diary for daily recording of the presences, severity of their headache and neck/shoulder pain, and their intake of analgesics (by type) | Intervention group showed a higher respondent rate for headache and for neck/shoulder pain, and a larger reduction in the days per month with headache |

| Mean age: | Intervention group: | |||

| intervention group: 48 control group: 47 |

relaxation exercises: concentrated craniofacial-cervical facial relaxation for 1 repetition 2 times daily | |||

| Chronic headache, neck/shoulder pain28,29 | posture retraining of upright standing, horizontal forward and backward head movements, and isometric extension (counter-pressure): 8–10 repetitions, every 2–3 hours | |||

| Nikander et al.11 RCT | 180 female office workers aged 25–53 years | All three groups were encouraged to perform aerobic exercise 3 times/week for 30 minutes | The control group received written information with the same stretching exercises as the training groups to complete three times/week for 20 minutes | One MET-hour of training per week accounted for an 0.8-mm decrease of neck pain on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and a 0.5-mm decrease on the Disability Index; a training dose of 20 MET(hour) per month represented a 16-mm decline in the VAS |

| Mean Age: | ||||

| strength group: 45 (±6) | Both training groups exercised 3 times/ week and also completed a single series of squats, sit-ups, and back extensor | |||

| endurance group: 45 (±6) | exercises as well as 20 minutes of stretching | |||

| control group: 46 (±5) | HEP only: | |||

| Constant or frequent chronic neck pain and disability occurring.6 months28,29 | Both groups attended a 12-day rehabilitation period to learn exercises followed by performing exercises for 12 months at home | The effective dose of the specific training program to decrease chronic neck pain was 8.75 MET(hour) per week on a scale of 1.5 (light work) to 10 (extremely heavy work) | ||

| Strength training group targeted neck muscles with rubber band 1 set of 15 repetitions 3 times/week at a resistance level of 80% patient’s maximum isometric strength from baseline |

||||

| upper body exercises 1 set of 15 repetitions (4–13 kg gradually increasing the load) with dumbbell including dumbbell shrugs, presses, curls, bent-over rows, flies, and pullovers Endurance-training group: | ||||

| trained neck muscles in supine position by lifting up head in 3 sets of 20 repetitions 3 times/week | ||||

| same upper body exercises as the strength training group with 2 kg dumbbells with 3 sets of 20 repetitions | ||||

| Salo et al.21 RCT | 180 female office workers, ages 25–53 years | HEP only: | The control group received written information with the same stretching exercises as the training groups to complete three times/week for 20 minutes | Both training groups had statistically significant score improvements as shown with the HRQoL 15D measurement tool. There was no change in the control group (P=0.012). The strength training group improved in 5 of 15 dimensions and the endurance-training group improved in 2 dimensions. 12-month follow-up: both the strength or endurance training seemed to moderately enhance the HRQoL of female patients with chronic neck pain |

| Mean age: | Both groups attended a 12-day rehabilitation period to learn exercises followed by performing exercises for 12 months at home | |||

| strength group: 45 (±6) | Strength training group: | |||

| endurance group: 45 (±6) | trained neck muscles with rubber band 1 set of 15 repetitions 3 times/week at a resistance | |||

| control group: 46 (±5) | level of 80% patient’s maximum isometric strength from baseline | |||

| Constant or frequent chronic neck pain and disability occurring >6 months28,29 | upper body exercises 1 set of 15 repetitions (4–13 kg gradually increasing the load) with dumbbell including dumbbell shrugs, presses, curls, bent-over rows, flies, and pullovers | |||

| Endurance-training group: | ||||

| trained neck muscles in supine position by lifting up head in 3 sets of 20 repetitions 3 times/week | ||||

| same upper body exercises as the strength training group with 2 kg dumbbells with 3 sets of 20 repetitions |

Quality assessment

All studies accepted for inclusion were assessed for their overall quality using the Maastricht–Amsterdam criteria.23−26Andersen et al.16 and Bronfort et al.17 scored ‘good’ (>80%) on the quality assessment, whereas all the remaining studies scored in the moderate range (50–80%) (Table 3).11,18−21 Blinding throughout the studies was variable. All seven studies were unable to blind the examiner rendering treat- ment, and only one of the seven studies was able to blind the patients from the intervention.18 Treatment group allocation was not concealed in four out of the seven studies.11,19−21 Allocation concealment ensures precise implementation of a random allocation sequence without prior knowledge of treatment assignments.30 Two of the included studies, Mongini et al.20 and Kujiper et al19, failed to blind the outcome assessor to the intervention.

Study selection and characteristics

There were a total of 1927 subjects included within this systematic review. Subjects were heterogeneous populations with varying geographical location, acuity of symptoms,28,29 and follow-up periods. Acuity of neck pain was classified and defined in each study as either acute,19 sub-acute,17,19 and/or chronic symptom duration.11,16,18−21 Two of the included studies failed to perform a follow-up;11,16 others studies performed follow-up at 4 weeks,18 14 weeks,17 6 months,19,20 40 weeks,17 and 12 months post discharge.17,18,21

Home exercise program adherence definition and measurement

Within the seven included studies, one study used the HEP as a co-intervention to clinical treatment,19 whereas six studies used a HEP only11,16−18,20,21 Adherence was defined in six of the studies and varied as to what constituted adherence (Table 6). Bronfort et al.17 was the only study to not indicate adherence. Adherence to the prescribed HEP was measured in six of the seven studies using means such as training diaries11,19−21 and questionnaires.16,18

Table 6.

Description of HEP interventions, adherence rates, and co-interventions

| Author | Included in HEP | # of exercises (time) | Adherence rates and definitions | Co-interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen et al.16 | Resisted training | 1 exercise, 2 minutes, 10 weeks | Control group 90% 2 minutes 65% 12 minutes 66% HEP: number of training sessions completed via Internet-based questionnaire Control group: informational emails read | 12% 2-minute group, 12% 12-minute group, 13% control group stated that they received treatmentby a doctor or physiotherapist for neckand shoulder complaints |

| Bronfort et al.17 | ‘Self-mobilization’/general | 6 exercises, 5–10 repetitions, | Adherence was not defined | Study does not differentiate between |

| movements | 6–8 times daily, 12 weeks | the specific effects of treatment and | ||

| the contextual (non-specific) effects | ||||

| Hall et al.18 | Augmented manual | 1 exercise, 2 repetitions, 2 times | Exercise compliance was greater | No co-interventions noted |

| daily, 12 months | in the C1–C2 self-SNAG group | |||

| when compared to the placebo. | ||||

| Compliance was assessed by a | ||||

| questionnaire. Subjects were | ||||

| contacted by telephone if they | ||||

| did fill out questionnaire | ||||

| Kuijper et al.19 | ROM/strength training | 10 exercises, 2 sets, 10 repetitions, | Adherence measured through | No co-interventions noted |

| daily, 6 weeks | patient diaries Patients wore the | |||

| collar First three weeks: cervical | ||||

| collar: 91%, PT plus HEP: 88% | ||||

| During weeks three to six: 14% | ||||

| did not exercise at all | ||||

| Mongini et al.20 | Relaxation exercises, | Relaxation: 1 repetition, twice a | A question on the frequency of | No co-interventions noted |

| ROM exercises, | day, 7 months | exercise was added to the month | ||

| posture exercises | ROM: 8–10 repetitions, every2–3 hours, 7 months | seven diary | ||

| Nikander et al.11 | Muscle endurance training | 3 sets of 20 reps, 3 times a week, | 86% strength | No co-interventions noted |

| 12 months | 93% endurance | |||

| Muscle strength training | 1 set, 15 repetitions, 3 times a week, | 65% control | ||

| 12 months | Adherence was measured with | |||

| training diaries | ||||

| Salo et al.21 | Endurance training | 3 sets of 20 reps, 3 times a week, | 86% strength | No co-interventions noted |

| 12 months | 93% endurance | |||

| Strength training | 1 set, 15 repetitions, 3 times a week, | 65% control | ||

| 12 months | Adherence was measured with | |||

| training diaries |

Outcome measures utilized

Various outcome measures were used to quantify the patient’s symptoms of neck pain or headache. Outcome reporting on the pain construct (either frequency and/or intensity) occurred on different measures within the included studies: Visual Analog Scale (VAS),11,16,19 Pain Scale (0–10),17 Neck/ Shoulder Pain Index,20 headache frequency,20 and HA Severity Index.18 Outcome reporting on the disability construct occurred on two different measures within the included studies: Disability Index11 and Neck Disability Index (NDI).11, 19 Only one study included the Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) as an outcome measure to examine the QOL construct.21

Results and synthesis of individual studies

Andersen et al.’s16 study included 198 subjects (174 females, 24 males) with chronic neck pain, with or without shoulder pain, who worked full time without known major disease or disability. This study had one of the highest quality score (16/19) of the included studies.16 Their study found that the HEP groups, which included 2-minutes and 12-minutes of resistance training, had a moderate effect on the VAS when compared to the control group, which received no intervention (Cohen’s d=0.67, 0.59, respectively).16 When comparing the two HEP groups, no statistically significant difference on pain was reported on the VAS with an effect size of 0.00.16

Bronfort et al.’s17 study included 272 participants, between the ages of 18 and 65 years, who had subacute, non-specific neck pain for 2–12 weeks.17 Bronfort et al.17 also yielded a high quality score (16/19). They found that the intervention group, which included advice, basic anatomy, postural instructions, demonstrations of daily actions, and a HEP, had a larger effect on the Pain Scale when compared to medication or spinal manipulation (effect sizes of 0.11 and 0.16, respectively).31

Both Kuijper et al.19 and Hall et al.18 had moderate quality scores (12/19, 13/19, respectively). Kuijper et al.’s19 study included 205 patients, between the ages of 18 and 75 years, with signs and symptoms of cervical radiculopathy of less than 1 month in duration. Kuijper et al.19 found that physiotherapy, which included graded activity exercises for cervical mobilization and stabilization, combined with a HEP intervention had a greater effect size on the VAS (0.47) and the NDI (0.11) when compared to the control, which was instructed to continue normal daily activities. Interestingly, when the physiotherapy with HEP intervention group was compared to the cervical collar group on the VAS and the NDI, the cervical collar group had a slightly larger effect size on these measures (0.18 VAS and 0.10 NDI). Hall et al.’s18 study included 32 participants, with a mean age of 36±3 years, who complained of chronic cervicogenic headache for the past 3 months, at least once per week.18 Hall et al.18 found that having a patient self-mobilize a specific spinal level to augment spinal motion within a HEP group had a large effect (1.79) on the HA Severity Index when compared to sham mobilization.

Nikander et al.11 and Salo et al.21 also yielded moderate quality scores (12/19, 12/19, respectively). Nikander et al.11 found improvements, similar to Andersen et al.,16 in pain in both their HEP strength and HEP endurance groups. Their endurance HEP group had a large effect on the VAS (0.84) and moderate effect on the Disability Index (0.63) compared to the control group. The Nikander et al.11 study included 180 female office workers aged 25–53 years old with constant or frequent chronic neck pain and disability occurring greater than 6 months.11 Nikander et al.’s11 HEP strength group had a strong effect size on the VAS (1.07) and Disability Index (0.96) when compared to the control group, who was advised to perform aerobic and stretching exercises without strengthening.22, 31 Additionally, the strength group had a stronger effect size when compared to the HEP endurance group on the VAS (0.23) and Disability Index (0.27).22, 31 Salo et al.’s21 follow-up study used the participants within the Nikander et al.11 study to qualitatively compare the HRQoL of the strength and endurance groups to a control group. The authors reported that both the strength and endurance HEP groups showed a greater effect than the control group when addressing QOL. Additionally, the strength HEP group had a greater effect when compared to the endurance group. Unfortunately, despite attempts to contact the authors of this study, no effect sizes could be calculated due to insufficient data.

Mongini et al.20 had the lowest quality score on the Maastricht–Amsterdam criteria list (10/19). Despite the low quality score, results of this study are consistent with the results of the higher quality studies. This study included 1040 participants between 43 and 52 years who were municipal workers with chronic headache (including tension-type headache or migraine), myogenous neck/shoulder pain, or headache and/or myogenous neck/shoulder pain.20 Mongini et al.20 showed that the addition of a HEP is more effective for headache pain relief (0.26) meaured by Headache Index and neck and/or shoulder pain captured by the Neck/Shoulder Pain Index (0.33) when compared to a control group.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

The purpose of this systematic review was to examine and describe the effects of using a therapeutic HEP for patients with neck pain (associated with whiplash, or non-specific, specific neck pain, with or without radiculopathy, or cervicogenic headache) on pain, function, and disability compared to other conservative treatment measures or a true control. Additionally, as a secondary objective, we synthe- sized the design/type of HEP programs and reported on measures of adherence. Based on our calculations, evidence suggests that HEP designs have a range of effects when combined with an intervention or when used alone. The HEP designs within these studies included programs that emphasized strength-training exercises, endurance-training exercises, and self-mobilization techniques.

Based on this review, strength-based HEPs, when used alone or in combination with another treatment, yielded the largest effect sizes on pain reduction.11,16,20 Based on Nikander et al.,11 there may be a relationship regarding the intensity/dosage of the strengthening program and the severity of the neck pain. Therefore, a higher intensity strengthening level may decrease neck pain severity. Specifically, they found that a training dose of more than 8.75 MET hour week-1 specifically for the neck, shoulder, and upper extremities will decrease neck pain. One MET is equivalent to the approximate rate of oxygen consumption of a seated individual at rest (3.5 ml kg-1 minute-1).11 The training dose of 8.75 MET hour week-1 equates to moderate intensity (i.e. walking briskly or patient rate of perceived exertion of 11–13) for 30 minutes on 5 days, or 2.5 hours/week, of physical activity.32,33 The level of activity for pain reduction, as indicated in this study, has been further recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine for proper musculoskeletal health.16, 33 Both strength and endurance protocols were found to be effective, but based on Nikander et al.’s11 findings, the effect sizes may be dependent on the dosage of training (MET hour week-1). Strength training was found to have a greater effect size, but this may be due to a larger exercise dosage compared to the endurance group. Salo et al.21 performed a 12-month follow-up of Nikander et al.’s11 research study and found that the HRQoL scores were better in the strength group compared to the endurance group. Interestingly, Andersen et al.16 found that there was no difference in the effect sizes between the 2-minute and the 12-minute HEP groups. Therefore, the amount of time spent performing the HEP exercises in this study did not correlate to a larger effect size or larger reduction in pain.

Utilization of specific self-mobilizations within a HEP may benefit patients with neck pain and/or headache. Hall et al.,18 whose HEP included a self- mobilization to a specific region/segment, were found to have the highest calculated effect size on neck pain when compared to the sham selfmobilization HEP intervention group (Cohen’s d=1.79). The experi- mental group performed two repetitions of a C1–C2 self-SNAG mobilization, held for 3 seconds, twice daily for 12 months. Therefore, the authors showed that specifically targeting a problematic segment/ cervical level may benefit a patient. In contrast to targeting a specific problematic segment/cervical level, Bronfort et al.’s17 study used ‘self-mobilization exercises’ that involved general non-specific neck motions including retraction. Hall et al.’s18 study yielded a larger effect size compared to Bronfort et al.17 (1.79, 0.16, respectively). Targeting specific dysfunctional cervical segments levels, such as the cervical segments C1–C2, for treatment of cervicogenic headache has been supported in the literature.34−39

A finding from Kuijper et al.19 suggested that a passive treatment, such as a cervical collar, may be better than physiotherapy, which included graded activity exercises for cervical mobilization and stabilization, with HEP. However, the effect sizes were trivial when compared on the VAS and the NDI (0.18, 0.10, respectively).22,31 This is not consistent with the cervical practice guidelines for treatment of neck pain.2 Additionally, the effects of a cervical collar on whiplash-associated injuries were not found to provide obvious benefits on functional recovery, reduction of pain, or reduction of disability following whiplash injuries.40 Although there is a difference seen within Kuijper et al.’s19 study, the difference is minimal and further research is necessary to determine whether there is a significant difference.

While adherence was defined in six out of the seven included studies, none of the authors used the same definition. This may influence how their tudies should be interpreted.11,16,18−21 The most common modes of monitoring adherence were training diaries11,19−21 and questionnaires.16,19 None of the studies included in this review used a cut-off percentage to define adherence but did report the rates of adherence (adherent vs non-adherent). It has been found in the literature that rates as low as 50% have been used to define program adherence.41 Rates of adherence within the included studies ranged from 66 to 93%. The mode of adherence calculations varied from study to study (Table 6).

Implications for clinical practice

After synthesizing the results of our systematic review, the authors would recommend a mixed treatment approach for an effective home exercise prescription. The suggested clinical recommendations for patients with neck pain based on this systematic review include:

designing a HEP to emphasize both strength- and endurance-training exercises of moderate intensity to improve neck pain and HRQoL measures;

designing a HEP that uses self-mobilizations to augment spinal motion or cervical ROM for patients with cervicogenic HA may reduce pain.

Specific details regarding these exercises are further described within our PICOS table (Table 5).

Limitations

There were a number of potential limitations to this systematic review. Although classifications are helpful, we wanted to examine the effects of neck HEP across diagnostic sub-classifications.

Another limitation relates to the quality scores assigned to the original studies. As the Maastricht– Amsterdam criteria list was used quantitatively, readers should note that certain criteria are more likely to be important than others in rating the overall quality of a study. Therefore, two studies with the same scores may not have an equivalent level of quality.

Only qualitative conclusions were drawn from Salo et al.21 regarding HRQoL due to insufficient data. With limited data, the authors of this systematic review were unable to calculate effect sizes, which limited subsequent interpretation of the data. In addition, six of the seven studies reported the end point mean and failed to report mean change scores. Resultantly, some of the calculated effect sizes of the interventions may be smaller or larger than could be reported for these studies.

A final limitation included the number of outcome measurements used within the studies. Only three of the seven studies selected more than one outcome measure (Table 2). A greater number of outcome measures allow for greater interpretation of the effectiveness of the interventions used.

Conclusions

According to the results of the studies analyzed in this systematic review, a HEP that emphasizes strength- ening and/or endurance is effective at reducing neck pain, function, disability, and improving QOL. The use of a HEP in combination with other conservative interventions, or alone, yields benefits with effect sizes ranging from trivial to moderate. The definitions of patient adherence with standardized cut-off levels may help research in this topic area become less variable and better evaluated, as it may impact the overall effect of the intervention.

References

- 1.Strine TW, Hootman JM. US National prevalence and correlates of low back and neck pain among adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:656–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Childs JD, Cleland JA, Elliott JM, Teyhen DS, Wainner RS, Whitman JM, et al. Neck pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:A1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borghouts JAJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM. The clinical course and prognostic factors of non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. Pain. 1998;77:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pleis JR, Ward BW, Lucas JW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Vital Health. Stat. 2010;10(249):1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2724–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoving JL, Koes BW, de Vet HCW, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, van Mameren H, et al. Manual therapy, physical therapy, or continued care by a general practitioner for patients with neck pain. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:713–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Artner J, Cakir B, Spiekermann J, Kurz S, Leucht F, Reichel H, et al. Prevalence of sleep deprivation in patients with chronic neck and back pain: a retrospective evaluation of 1016 patients. J Pain Res. 2013;6:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ylinen J. Physical exercises and functional rehabilitation for the management of chronic neck pain. Eura Medicophys. 2007;43:119–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linton SJ, van Tulder MW. Preventive interventions for back and neck pain problems. Spine. 2001;26:778–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moffett J, McLean S. The role of physiotherapy in the management of non-specific back pain and neck pain. Rheumatology. 2006;45:371–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikander R, Malkia E, Parkkari J, Heinonen A, Starck H, Ylinen J. Dose–response relationship of specific training to reduce chronic neck pain and disability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:2068–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swartz MK. The PRISMA statement: a guideline for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Pediatr Health Care. 2011;25:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Tulder MW, Assendelft WJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group for Spinal Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:2323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stribos J, Martens R, Prins F, Jochems W. Content Analysis: what are they talking about? Comput Educ. 2006;46:29–48. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen LL, Saervoll CA, Mortensen OS, Poulsen OM, Hannerz H, Zebis MK. Effectiveness of small daily amounts of progressive resistance training for frequent neck/shoulder pain: randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2011;152:440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bronfort G, Evans R, Anderson AV, Svendsen MS, Bracha Y, Grimm RH. Spinal manipulation, medication, or home exercise with advice for acute and subacute neck pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall T, Chan HT, Christensen L, Odenthal B, Wells C, Robinson K. Efficacy of a C1–C2 self-sustained natural apophyseal glide (SNAG) in the management of cervicogenic headache. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuijper B, Tans J, Beelen A, Nollet F, Visser M. Cervical collar or physiotherapy versus wait and see policy for recent onset cervical radiculopathy: randomised trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mongini F, Evangelista A, Milani C, Ferrero L, Ciccone G, Ugolini A, et al. An educational and physical program to reduce headache, neck/shoulder pain in a working com- munity: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:E29637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salo PK, Hakkinen AH, Kautiainen H, Ylinen JJ. Effect of neck strength training on health-related quality of life in females with chronic neck pain: a randomized controlled 1-year follow-up study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. revised ed. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lystad RP, Bell G, Bonnevie-Svendsen M, Carter CV. Manual therapy with and without vestibular rehabilitation for cervico- genic dizziness: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2011;19:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olmos M, Antelo M, Vazquez H, Smecuol E, Maurino E, Bai JC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies on the prevalence of fractures in coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lystad RP, Pollard H, Graham PL. Epidemiology of injuries in competition taekwondo: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12:614–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swain MS, Lystad RP, Pollard H, Bonello R. Incidence and severity of neck injury in Rugby Union: a systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14:383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olivo SA, Macedo LG, Gadotti IC, Fuentes J, Stanton T, Magee DJ. Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2008;88:156–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) IASP task force for taxonomy Pain terminology. Seattle: IASP;2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guzman J, Hurwitz EL, Carroll LJ, Haldeman S, Cote P, Carragee EJ. A new conceptual model of neck pain. Linking onset, course, and care: the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and it’s associated disorders. Spine. 2008;33:S14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet. 2002;359(9306):614–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook C. Clinimetrics corner: use of effect sizes in describing data. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16:E54–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCullough ML, Patel AV, Kushi LH, Patel R, Willett WC, Doyle C, et al. Following cancer prevention guidelines reduces risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1089–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson WR, Gordan NF, Pescatello LS. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription Hubsta Ltd; 2009. Lippincott Williams + Wilkins: Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen OK, Nielsen FF, Vosmar L. An open study comparing manual therapy with the use of cold packs in the treatment of post-traumatic headache. Cephalalgia. 1990;10:241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jull G, Trott P, Potter H, Zito G, Niere K, Shirley D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:1835–43; discussion 1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsson N, Christensen HW, Hartvigsen J. The effect of spinal manipulation in the treatment of cervicogenic headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997;20:326–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen SM. Articular and muscular impairments in cervico- genic headache: a case report. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:21–30; discussion 30-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoensee SK, Jensen G, Nicholson G, Gossman M, Katholi C. The effect of mobilization on cervical headaches. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21:184–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whorton R, Kegerreis S. The use of manual therapy and exercise in the treatment of chronic cervicogenic headache. J Man Manip Ther. 2000;8:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crawford JR, Khan RJ, Varley GW. Early management and outcome following soft tissue injuries of the neck – a randomized controlled trial. Injury. 2004;35:891–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medina-Mirapeix F, Escolar-Reina P, Gascon-Canovas J, Montolla-Herrador J, Jimeno-Serrano F, Collins S. Predictive factors of adherence to frequency and duration components in home exercise programs for neck and low back pain: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:155–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]