Abstract

Background:

Around 50% of primary melanomas harbour BRAF mutations, but their prognostic impact has not been clear. Recently, a BRAF-V600E mutation-specific antibody has become available for immunohistochemistry. Here, we investigated for the first time the prognostic impact of BRAF-V600E protein expression in primary melanoma.

Methods:

In a patient series of 248 nodular melanomas, BRAF-V600E and total BRAF expression were assessed by immunohistochemistry using tissue microarray sections of paraffin-embedded archival tissue. Mutation status was assessed by real-time PCR in cases with sufficient tumour tissue (n=191).

Results:

Positive BRAF-V600E expression was present in 86 (35%) of the cases, and was significantly associated with increased tumour thickness, presence of tumour ulceration and reduced survival. Further, BRAF-V600E expression was an independent prognostic factor by multivariate analysis, whereas BRAF mutation status was not significant. There was 88% concordance between BRAF-V600E expression and mutation status.

Conclusions:

Our findings indicate that BRAF-V600E expression is a novel prognostic marker in primary melanoma.

Keywords: BRAF-V600E, immunohistochemistry, PCR, primary nodular melanoma, prognosis, survival

The incidence of cutaneous melanoma has increased in fairly skinned populations worldwide during the last decades (Nikolaou and Stratigos, 2014). The prognosis is poor for patients with metastatic disease, and therapeutic opportunities have been limited. Recently, new targeted and immunotherapeutic agents that prolong progression-free and overall survival for patients with advanced melanoma have become available (Shah and Dronca, 2014). Detection of BRAF-V600 mutations is now mandatory to select patients with unresectable stage III and stage IV melanoma to targeted treatment with BRAF inhibitors. BRAF is the most frequently mutated oncogene in cutaneous melanoma, and nearly 50% of primary and metastatic melanomas harbour mutations in BRAF (Davies et al, 2002; Long et al, 2011; Colombino et al, 2012).

A mutation-specific antibody has been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity for immunohistochemical detection of the BRAF-V600E mutation in melanoma. Reported sensitivities range from 72% to 100%, and specificities range from 47% to 100% (Long et al, 2013; Ehsani et al, 2014; Liu et al, 2014; Thiel et al, 2014; Ritterhouse and Barletta, 2015). In a comparison of Sanger sequencing, pyrosequencing, real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC), IHC was comparable to pyrosequencing in detection of the mutation with a sensitivity and specificity of 100% (Colomba et al, 2013). This study recommended IHC as a first line method for detection of the BRAF-V600E mutation in melanoma, and to use DNA-based tests in addition for BRAF-V600E negative or uninterpretable cases.

The proto-oncogene, BRAF, is part of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Presence of an activating BRAF mutation in melanoma cells is believed to be constitutively stimulate and drive the MAPK-pathway, resulting in increased cell proliferation (Smalley, 2003). The BRAF-V600E mutation accounts for ∼80% of the BRAF mutations, and the BRAF-V600K mutation accounts for nearly 20%. Other less common mutations are the V600R and V600D mutations (Long et al, 2011; Bucheit et al, 2013).

Since the discovery of frequent BRAF mutations in melanoma by Davies et al (2002), multiple studies have investigated their association with distinct melanoma phenotypes and survival. The most common findings in previous investigations have been associations with younger age at diagnosis, melanoma arising on intermittently sun-exposed body-sites, and the superficially spreading melanoma subtype (Liu et al, 2007; Devitt et al, 2011; Long et al, 2011; Meckbach et al, 2014a). Regarding tumour features, two studies demonstrated an association with tumour thickness (Ellerhorst et al, 2011; Garcia-Casado et al, 2014), and some studies indicate a relation between BRAF mutation and increased proliferation such as higher mitotic count (Long et al, 2011; Meckbach et al, 2014a). Also, associations with presence of ulceration have been found in previous studies (Akslen et al, 2005; Ellerhorst et al, 2011; Si et al, 2012; Garcia-Casado et al, 2014).

Along with these findings, a prognostic value of BRAF mutation in primary melanoma has been discussed. Nagore et al (2014) found an independent prognostic impact of BRAF mutation on disease-free survival, but not for overall survival. Two other studies found an association with reduced survival, but multivariate analysis was not performed (Si et al, 2012; Wu et al, 2014). Recently, an independent impact of BRAF mutation on melanoma-specific survival has been demonstrated (Mar et al, 2015; Thomas et al, 2015). Still, there are previous studies reporting no association with survival (Akslen et al, 2005; Devitt et al, 2011; Ellerhorst et al, 2011; Meckbach et al, 2014a). For stage III and IV melanoma, the findings have also been diverse. BRAF mutation has been associated with reduced survival in some studies (Long et al, 2011; Mann et al, 2013; Barbour et al, 2014), although others found no association (Ellerhorst et al, 2011; Carlino et al, 2014; Meckbach et al, 2014b). One study has examined the predictive value of BRAF expression and response to BRAF inhibitors, without finding any association (Wilmott et al, 2013). In summary, the prognostic role of BRAF mutation in melanoma remains undetermined.

All previous studies analysing clinico-pathologic associations and prognostic impact of BRAF mutation in primary melanoma have used DNA-based tests for detection of the mutation, whereas the prognostic influence of BRAF-V600E protein expression has not yet been analysed. Here, we sought to determine whether BRAF-V600E protein expression in cutaneous melanoma is associated with clinico-pathologic features and disease-specific survival.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This patient series consists of 255 consecutive cases of nodular cutaneous melanomas diagnosed at the Department of Pathology, Haukeland University Hospital (Bergen, Norway) during 1998–2008. The presence of a vertical growth phase and absence of a radial growth phase, that is adjacent in situ or microinvasive components, were used as inclusion criteria. Cases with minor secondary involvement of the adjacent epidermis up to three epidermal ridges were included. There was no known history of familial occurrence. During this time period, the sentinel node procedure was not performed in Norway. This patient series therefore lacks complete staging.

Median age was 70 years, and the median tumour thickness was 3.6 mm (range 0.7–29.0 mm). Complete information on patient survival, time and cause of death was available in all 255 cases. Last date of follow-up was 31 December, 2008, and median follow-up time for survivors was 31 months (range 0–131 months). During the follow-up period, 60 patients (23.5%) died of malignant melanoma and 40 (16%) died of other causes. A summary of patient characteristics is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

|

Age (years) | |

| Median (range) | 70 (21–98) |

|

Sex | |

| Men | 138 |

| Women | 117 |

|

Tumour anatomic site | |

| Trunc | 77 |

| Non-trunc | 175 |

|

Causes of death | |

| Alive | 155 |

| Melanoma-specific death | 60 |

| Other death causes | 40 |

In the present study, previously reported information on clinico-pathologic characteristics, the mitotic marker PHH3 and survival data was included for comparison (Ladstein et al, 2012a, 2012b). The Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Regional Committee for Ethics in Research (Health Region III; 178.05) have approved this project. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

Clinico-pathologic variables

Previously recorded clinical data and histologic variables included in this study were: date of histologic diagnosis, sex, age at diagnosis, tumour anatomic site, tumour thickness according to Breslow (Breslow, 1970), level of invasion according to Clark et al (1969), mitotic count, microscopic tumour ulceration (Ladstein et al, 2012a) and tumour necrosis (Ladstein et al, 2012b).

Tissue microarray (TMA)

The TMA technique has been described and validated in several studies (Kononen et al, 1998; Nocito et al, 2001; Straume and Akslen, 2002). Three tissue cylinders from representative tumour areas identified on H&E stained slides, generally at the supra-basal area of the melanoma, were punched and mounted into a recipient paraffin block using a custom made precision instrument (Beecher Instruments, Silver Spring, MD, USA). The diameter of the tissue cylinders was 1.0 mm. Sections of the resulting TMA blocks (5 μm) were made by standard technique.

Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemical staining was performed on 5-μm-thick TMA sections of paraffin-embedded archival tissue. Sufficient tumour tissue for IHC was available in 248 of the 255 cases. For detection of BRAF-V600E expression we used the Ultraview Red procedure (catalogue # 760-501) (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) on the Ventana Benchmark Ultra immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems). The slides were deparaffinized with Ventana Ez-prep (catalogue # 950-102, Ventana Medical Systems) before antigen retrieval with Ventana Ultra Cell Conditioner 1 solution (catalogue # 950-224, Ventana Medical Systems) at pH 8–9 for 64 min at 95 °C. The slides were then incubated with undiluted anti-BRAF-V600E clone VE1 mouse monoclonal primary antibody (catalogue # 790-4855, Ventana Medical Systems) for 32 min in room temperature. Detection was done using the Ventana Ultraview Universal Alkaline Phosphatase Red detection kit (catalogue # 760-501, Ventana Medical Systems) with Ventana Amplification kit (catalogue # 760-080, Ventana Medical Systems). The slides were finally counterstained with hematoxylin. Two nodular melanomas with known BRAF-V600E negative and positive status confirmed by Therascreen PCR mutation analysis were used as negative and positive controls.

For detection of total BRAF protein expression, the slides were dewaxed with xylene/ethanol before microwave antigen retrieval for 20 min in Target Retrieval Solution (DAKO 1699, Glostrup, Denmark) (pH=6). Endogenous peroxidase activity was prevented by treating the slides with peroxidase block (DAKO S2001) for 8 min. The slides were incubated with a polyclonal anti-BRAF antibody (dilution 1:200) (catalogue # B1687) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The staining procedure was performed using the anti-rabbit EnVision labelled polymer method (DAKO K4011) with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) (DAKO K3469) as substrate chromogen. Brief counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin (DAKO S2020). Negative controls were obtained by omitting the primary antibody.

Evaluation of staining

Expression of both BRAF-V600E and total BRAF was characterised by cytoplasmatic staining of melanoma cells. The staining intensity was recorded as either negative, weak, moderate or strong (0–3). Proportion of tumour cells stained was recorded as either 1 (<10%), 2 (10–50%) or 3 (>50%). A staining index (SI) was calculated as the product of staining intensity and area score (proportion of tumour cells stained) (Straume and Akslen, 1997). For additional evaluation of the staining, a subset of cases (n=69) was scored blindly by two observers (EH, RGL) showing very good inter-observer agreement (κ=0.85, P<0.01) for BRAF-V600E staining and good inter-observer agreement (κ=0.68, P<0.01) for total BRAF staining. Evaluation of the cases was done blindly for patient characteristics and outcome.

DNA extraction

The tumour area was identified and marked by the pathologist (LAA) on hematoxylin and eosin stained slides. Marked tumour tissue was manually dissected from five slides (10 μm thick) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue for each case. DNA was extracted using the QIAmp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen 56404, Hilden, Germany) for the first 130 cases, and the E.Z.N.A tissue DNA kit (Omega Biotek D3396, Norcross, GA, USA) for the remaining cases (with no significant difference in mutation frequency). The DNA concentration was determined by the NanoDrop Spectrophotometer.

Real-time PCR

The Therascreen BRAF RGQ PCR Kit (Qiagen, Manchester, UK) was used for the BRAF mutation analysis. The assay detects five somatic mutations in BRAF codon 600: V600E, V600E complex (V600Ec), V600D, V600K and V600R, but cannot distinguish between V600E and V600Ec. Therascreen applies Amplification Refractory Mutation System (ARMS) and Scorpion technologies to ensure the specific amplification of mutated DNA. The real-time PCR was performed on the Rotator-Gene Q 5plex HRM instrument (Quiagen, Manchester, UK). All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Sanger sequencing

PCR amplification was performed using the AmpliTaq Gold PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR products were enzymatically treated by IllustraExoProStar 1-Step (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK) before sequenced in both directions using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit version 1.1 (Applied Biosystems). The sequence reactions were analysed on the Applied Biosystems3500xL Genetic Analyzer using Sequencing Analysis software, version 6 (Applied Biosystems), and the electropherograms were examined manually.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM Statistical package for the Social Sciences version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Associations between different categorical variables were assessed by Pearson's χ2 test. Non-parametric correlations were tested by the Spearman's ρ correlation coefficient. Comparison of two or more continuous variables not following the normal distribution was performed using the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests. Kappa (κ) statistics was used in analyses of inter-observer agreement of categorical data.

Univariate analyses of time to death due to malignant melanoma were performed using the product-limit procedure (Kaplan–Meier method), and differences between categories were estimated by the log-rank test, with date of histological diagnosis as the starting point. Patients who died of other causes were censored at the date of death. The influence of co-variates on patient survival was analysed by the proportional hazards method, and tested by the likelihood ratio (lratio) test. The variables were tested by log–log plot to determine their ability to be incorporated in multivariate models. All results were considered significant if P⩽0.05. In the statistical analyses, the cut-off points for categorisation were determined after considering the frequency distribution curve, size of subgroups and number of events.

Results

IHC for BRAF-V600E-VE1 and total BRAF protein expression

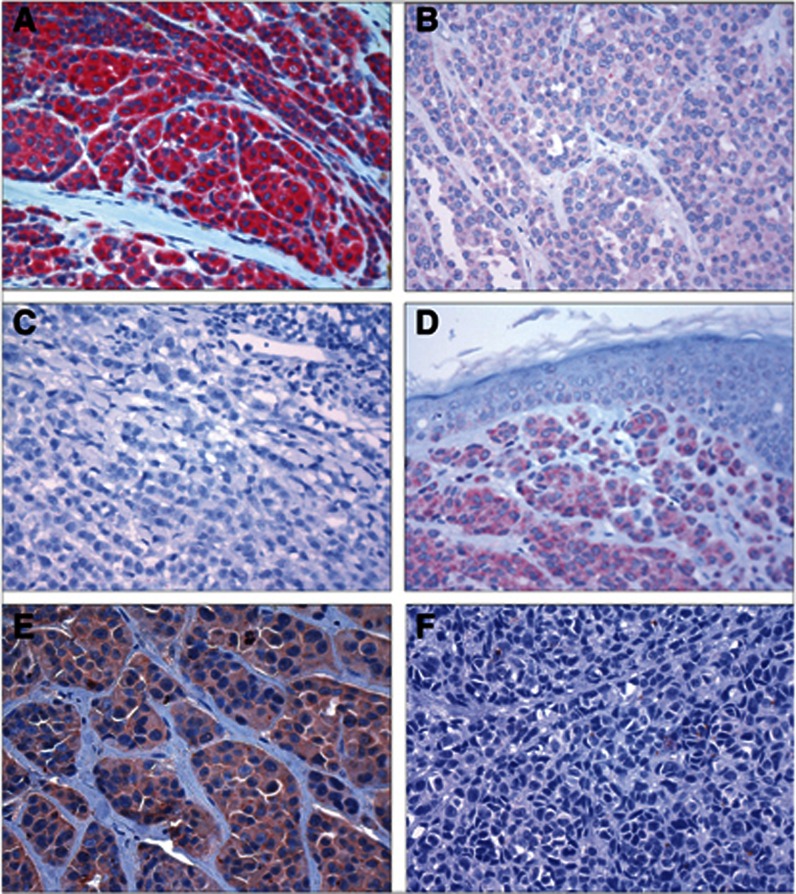

Staining obtained with the BRAF-V600E-VE1 antibody was assessed in 248 cases. The staining was cytoplasmic and generally homogenous, and differences in staining intensity between tumour areas were rarely observed. In statistical analyses, BRAF-V600E expression was categorised according to staining index as either negative (SI 0–2) (n=57; 23%), borderline/weak (SI 3) (n=105; 42%) or strongly positive (SI 4–9) (n=86; 35%), with cut-off points based on the lower quartile (SI 0–2) and median values (SI 3) (Figure 1). In the analyses of BRAF-V600E expression categorised in two groups (negative and weak vs positive), the cut-off point was based on the median value (SI 3).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining. Immunohistochemical staining showing nodular melanomas with positive (A), weakly positive (B) and negative (C) BRAF-V600E expression. Positive BRAF-V600E expression is shown in a BRAF-V600E mutation-positive benign naevus (D). Nodular melanoma with positive (E) and negative (F) total BRAF expression.

Staining obtained with the antibody for total BRAF protein was assessed in 248 cases. The staining was cytoplasmic and generally homogenous, and differences in staining intensity between tumour areas were rarely observed. In the statistical analyses, total BRAF expression was categorised as either negative (SI 0–2) (n=37; 15%) or positive (SI 3–9) (n=211; 85%) (Figure 1); the cut-off point was based on the distribution of the median values of tumour thickness and mitotic count, which both showed a shift in value between staining index 2 and 3.

Real-time PCR analysis of BRAF mutation status

BRAF mutation status could be determined in 191 of the 248 cases (77%) with sufficient tissue left in the paraffin blocks. Of these, 67 cases (35%) were BRAF-V600E/Ec-mutation positive, 9 cases (5%) were BRAF-V600K-mutation positive, and 2 cases (1%) were BRAF-V600R-mutation positive (Table 2). Cases with sufficient tissue for PCR analysis (n=191) were significantly thicker, had higher frequency of ulceration, higher mitotic count and were significantly associated with positive BRAF-V600E expression, when compared with the others (all P<0.05, χ2 test; data not shown).

Table 2. Summary of BRAF mutation status by PCR and BRAF-V600E expression.

|

BRAF-V600E expression (SI)a |

||

|---|---|---|

| Negative (0–3) | Positive (4–9) | |

|

BRAF

mutation status | ||

| Negative | 99 (86%) | 14 (18%) |

| BRAF-V600E | 8 (7%) | 59 (78%) |

| BRAF-V600K | 6 (5%) | 3 (4%) |

| BRAF-V600R | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 115 | 76 |

Cut-off point median.

BRAF protein expression in association with BRAF mutation status and clinico-pathologic characteristics

Positive BRAF-V600E expression was significantly associated with increased tumour thickness, presence of tumour ulceration, truncal anatomic site, and younger age at diagnosis (P<0.05, Kruskal–Wallis or χ2 tests), and a tendency to increased mitotic count (P=0.062, Kruskal–Wallis test) (Table 3). In pairwise analyses, the weakly stained (borderline) subgroup had significantly increased tumour thickness, presence of tumour ulceration and higher mitotic count when compared to the completely negative subgroup (all P<0.05, Mann–Whitney test and χ2 test) (data not shown).

Table 3. BRAF-V600E and total BRAF protein expression (n=248) and BRAF mutation status (n=191) in association with histopathologic variables.

|

BRAF-V600E expression (SI)a |

Total BRAF expression (SI)b |

Mutation status by PCR |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | 0–2 | 3 | 4–9 | P | 0–2 | 3–9 | P | Negative | V600E | Non-V600E | P |

| Tumour thickness (mm) | 0.01c | <0.01d | nsc | ||||||||

| Median | 2.2 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 4.0 | |||

| Ulceratione | 0.02f | nsf | nsf | ||||||||

| Absent (n) | 35 | 48 | 33 | 20 | 96 | 51 | 27 | 3 | |||

| Present (n) | 21 | 56 | 52 | 16 | 113 | 62 | 39 | 7 | |||

| Mitotic count (no./mm2) | 0.06c | <0.01d | ns | ||||||||

| Median | 3.8 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 4.7 | |||

| Tumour necrosis | nsf | nsf | nsf | ||||||||

| Absent (n) | 44 | 77 | 65 | 32 | 154 | 79 | 50 | 8 | |||

| Present (n) | 13 | 28 | 21 | 5 | 57 | 34 | 17 | 3 | |||

| Age (years) | <0.01c | nsd | <0.01c | ||||||||

| Median | 70 | 75 | 63 | 70 | 71 | 73 | 64 | 78 | |||

| Anatomic siteh | 0.04g | nsf | nsf | ||||||||

| Truncus (n) | 14 | 30 | 33 | 14 | 63 | 29 | 25 | 3 | |||

| Other (n) | 43 | 75 | 50 | 23 | 145 | 84 | 39 | 8 | |||

Abbreviation: SI=staining index.

Cut-off point lower quartile and median.

Cut-off point see text.

Kruskal–Wallis test.

Mann–Whitney U test.

3/248 and 2/191 missing cases; information not available.

χ2 test.

χ2 test SI 0–3 vs 4–9.

3/248 and 3/191 missing cases; information not available.

Assessing the combination of mutation negative and BRAF-V600E mutated cases (n=180), there was 88% concordance between BRAF-V600E protein expression and mutation status; 22 of the 180 cases (12%) were discordant: 8 cases (4%) were BRAF-V600E expression negative and BRAF-V600E-mutation positive, whereas 14 cases (8%) were BRAF-V600E expression positive and BRAF-V600E-mutation negative (Table 2). Positive BRAF-V600E expression was significantly associated with BRAF mutation status (negative vs V600E) (P<0.01, χ2 test) (not shown). Of the 9 BRAF-V600K mutated cases, 1 case was BRAF-V600E expression negative, 5 cases were BRAF-V600E weakly positive, and 3 cases were BRAF-V600E positive. Of BRAF-V600R mutated cases, 2 of 2 were BRAF-V600E expression weakly positive (Supplementary Table S1). There were significantly more V600K mutations in the BRAF-V600E weakly stained subgroup compared to BRAF-V600E positive cases (P<0.01, χ2 test) (data not shown). There were no associations between BRAF-V600E mutation status (negative vs V600E vs non-V600E mutations) and clinico-pathologic variables, except for significantly younger patient age in the V600E mutant cases (P<0.01, Kruskal–Wallis test) (Table 3).

Sanger sequencing was performed for the 14 discordant cases with positive BRAF-V600E expression and negative mutation status by real-time PCR analysis. One of these 14 cases showed a BRAF-V600E mutation by sequencing (GTG/GAG), the others were mutation negative by this method.

Total BRAF protein expression was significantly associated with increased tumour thickness and mitotic count when looking at all cases (P<0.01, Mann–Whitney U test) (Table 3), as well as when restricting the analysis to BRAF-V600E negative or weakly stained cases (P<0.01) (not shown). There was a weak but significant correlation between BRAF-V600E-VE1 and total BRAF expression (Spearman's ρ correlation coefficient 0.17, P<0.01), also when analysed as categorical variables (P<0.01, χ2 test) (Table 4). Including the BRAF-V600E expression negative and weakly stained cases, total BRAF protein expression was increased in the subgroup with weak BRAF-V600E expression (P<0.01, χ2 test) (not shown). When looking at the 14 discordant cases with positive BRAF-V600E expression and negative mutation status, all of these except one had positive total BRAF expression (not shown).

Table 4. Total BRAF expression in correlation with BRAF-V600E expression.

|

BRAF-V600E expression (SI)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (0–2) | Weakly positive (3) | Positive (4–9) | P | |

| Total BRAF expression (SI)b | <0.01c | |||

| Negative (0–2) | 21 (37%) | 7 (7%) | 9 (10%) | |

| Positive (3–9) | 36 (63%) | 98 (93%) | 77 (90%) | |

Cut-off point lower quartile and median.

Cut-off point see text.

χ2 test.

Survival analyses

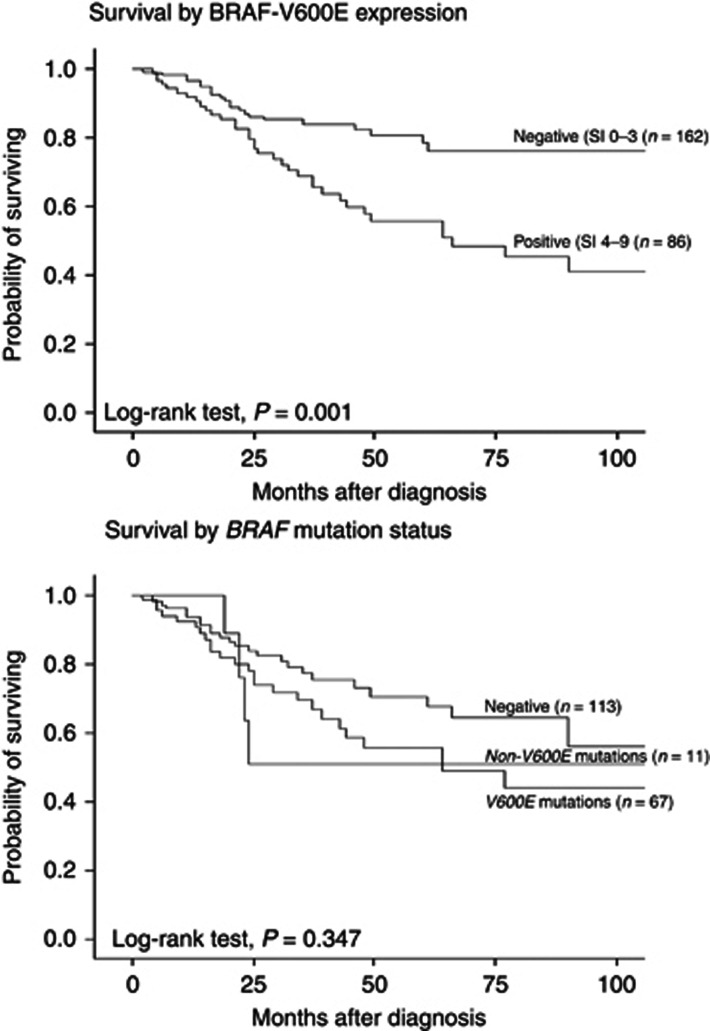

Univariate analysis showed significantly reduced survival for cases with strongly positive BRAF-V600E expression, both when categorised as two groups (negative and weak vs positive) (P=0.001) (log-rank test) (Figure 2), and three groups (negative vs weak vs positive) (P=0.001) (Supplementary Figure S1). Within the 191 cases in which mutation status could be assessed, BRAF-V600E protein expression was still associated with reduced survival (P=0.01) (not shown). Univariate analysis of total BRAF protein expression showed a tendency to reduced survival for cases with positive total BRAF expression (P=0.082) (data not shown). Univariate analysis of BRAF mutation status (negative vs V600E vs non-V600E) was not significantly associated with patient survival (P=0.35) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival curves. Survival curves by BRAF-V600E expression (n=248) and by BRAF mutation status (n=191) (Kaplan–Meier method, log-rank significance test). SI in parenthesis.

In multivariate analysis (proportional hazards method), we first examined the variables included in the pT classification from 2010 (Balch, 2009): tumour thickness, ulceration and mitotic count. In this basic model, tumour thickness >4.0 mm compared to tumours ⩽2.0 mm (HR 5.7, CI 1.7–19.3, P=0.003) and presence of ulceration (HR 2.3, CI 1.2–4.3, P=0.005) were independent predictors of reduced survival, whereas mitotic count did not obtain statistical significance (P=0.10). Next, the same variables were included together with BRAF-V600E protein expression. Tumour thickness >4.0 mm (HR 6.6, CI 1.5–29.0, P=0.007), presence of ulceration (HR 2.0, CI 1.1–3.8, P=0.026), mitotic count (HR 2.7, CI 0.9–7.7, P=0.036) and positive BRAF-V600E expression HR 2.3, CI 1.4–4.0, P=0.001) were all significant and independent predictors of prognosis in the final model (Table 5).

Table 5. Multivariate survival analysis (Cox' proportional hazards method), with the final model after inclusion of tumour thickness, ulceration, mitotic count and BRAF-V600E protein expression (n=245).

| Variable | N | HR | 95% CI | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour thickness (mm) | 0.007 | |||

| ⩽2.0 | 58 | 1 | ||

| 2.1–4.0 | 86 | 6.1 | 1.4–27.0 | |

| >4.0 | 101 | 6.5 | 1.5–29.0 | |

| Ulceration | 0.026 | |||

| Absent | 116 | 1 | ||

| Present | 129 | 2.0 | 1.1–3.8 | |

| Mitotic count (no./mm2)b | 0.036 | |||

| ⩽1.9 | 56 | 1 | ||

| >1.9 | 189 | 2.7 | 0.9–7.7 | |

| BRAF-V600E expression (SI)c | 0.001 | |||

| Negative (0–3) | 162 | 1 | ||

| Positive (4–9) | 85 | 2.3 | 1.4–4.0 |

Abbreviations: HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval.

Likelihood ratio.

Cut-off point lower quartile.

Cut-off point median.

Discussion

The detailed role of BRAF alterations in the progress and prognosis of cutaneous melanoma is still being discussed. To our knowledge, BRAF-V600E protein expression in association with patient survival has not been previously reported for these tumours. Here, we found that strong BRAF-V600E protein expression, present in 35% of the cases, was associated with aggressive tumour features like increased thickness and presence of ulceration, and represented an independent prognostic factor in a large cohort of nodular cutaneous melanoma. This indicates a strong relationship between BRAF-V600E protein in the primary tumour and long-term outcome in terms of melanoma-related deaths, and expression status should be determined on the primary tumours at the time of diagnosis, at least for this aggressive melanoma subtype.

The frequency of positive BRAF-V600E expression and the BRAF-V600E mutation rate were both slightly lower than expected from most previous reports on BRAF mutation rate in primary melanoma (Colombino et al, 2012), although the mutation rate was almost the same as the one we found in our previous study using Sanger sequencing on a different but similar cohort (Akslen et al, 2005). This might be related to the relatively high median age of our cases, which is likely to be a reflection of the nodular subtype (Moreno-Ramirez et al, 2015).

Previous studies have been diverse regarding the impact of BRAF mutation on patient survival in primary melanoma. However, population differences, patient selection and melanoma subtypes, methods of BRAF mutation detection, and subtypes of BRAF mutations varied in these studies making direct comparisons difficult. Here, we found no prognostic value of BRAF mutation status by PCR, similarly to our previous study using Sanger sequencing on a different but similar cohort (Akslen et al, 2005). Regarding the prognostic value, it is not clear why BRAF-V600E protein expression, but not mutation status, is associated with reduced survival, and this finding needs to be studied in more detail.

Methodological issues have to be considered. Mutation status was analysed by real-time PCR on all cases with sufficient DNA. Assessing the combination of BRAF mutation negative and BRAF-V600E positive cases (n=180), 22 cases showed discordancy compared to BRAF-V600E protein expression; 14 cases were BRAF-V600E-expression positive but mutation negative, and 8 cases were BRAF-V600E expression negative but V600E-mutation positive. This discordance rate is slightly higher than in previous studies. One possible explanation for the discordant cases might be intra-tumoral heterogeneity. Due to limited amount of tissue for many cases in our series, sections used for IHC and mutation analysis could be derived from different paraffin blocks in some cases. In support of this are reports on heterogeneity of the BRAF-V600E mutation within individual melanoma specimens (Miller et al, 2004; Yancovitz et al, 2012). Further, false-negative interpretation of BRAF-V600E protein expression might be due to impaired antigenicity of the epitope because of tissue coagulation or early necrosis (Capper et al, 2011), although this was not a frequent finding in our melanoma series. In a study by Ehsani et al (2014), 32% of melanoma tumours were BRAF-V600E-expression positive by IHC and mutation negative by PCR. Lade-Keller et al (2013) reported 4 of 13 melanoma cases as IHC positive and PCR negative. In an analysis of circulating melanoma cells, Hofman et al (2013) reported 15% of cases to be IHC positive and pyrosequencing negative. The mechanism behind these false-positive cases is not clear. False-positive interpretation might be due to antibody cross-reactivity to an unknown epitope. Another explanation for the discordancy in our study could be that the PCR method is not as sensitive as IHC, although it is proved to be more sensitive than Sanger sequencing (Colomba et al, 2013). Still, we found that one of the 14 discordant cases (7%) with negative mutation status by PCR was V600E-mutation positive by Sanger sequencing. Thus, a positive IHC result could represent the presence of a mutated BRAF-V600E protein even in the absence of a positive molecular test.

Importantly, our data do not allow for a conclusion as for which method is the best for detection of the BRAF-V600E mutation. It is likely, based on our findings, that both IHC and PCR have missed a few BRAF-V600E mutated cases, and the two methods might therefore be combined in the work-up of these tumours. This is also in line with the conclusion of previous studies assessing BRAF mutation status by IHC and molecular methods (Ihle et al, 2014; Uguen et al, 2015).

In a subgroup of the cases, weak BRAF-V600E staining was observed. Interestingly, these cases had similar thickness and mitotic rate as the BRAF-V600E-positive cases, and the survival was intermediary between positive and completely negative cases. In total, 67 of 79 BRAF-V600E expression weakly positive cases were mutation negative (85%), 5 had a V600E mutation (6%) and 7 (9%) had a non-V600E mutation. We hypothesised that the characteristics of the BRAF-V600E weakly positive subgroup could be caused by an upregulation of wild-type BRAF, and this was supported by our findings that weak BRAF-V600E expression was significantly associated with increased total BRAF. Further, total BRAF expression was associated with increased tumour thickness and mitotic count. Previously, an association of increased total BRAF protein expression and reduced survival has been reported (Safaee Ardekani et al, 2013). Our findings do suggest that cases with upregulation of wild-type BRAF might demonstrate a weakly positive staining also for BRAF-V600E. Another possible explanation for the findings could be the presence of non-V600E mutations in the group with weak or borderline BRAF-V600E expression, and this was found. In comparison with BRAF-V600E mutations, BRAF-V600K mutations have previously been found to be associated with shorter time from diagnosis of primary melanoma to first distant metastasis, but with no difference in survival thereafter (Menzies et al, 2012). We found significantly more non-V600E mutations in the BRAF-V600E expression weakly positive subgroup compared to the BRAF-V600E-expression positive subgroup. Further, the survival plot for the non-V600E mutations shows an early and steep fall which could represent early metastasis in these cases.

In summary, we find that BRAF-V600E protein expression detected by IHC is independently associated with reduced survival, whereas this was not the case for BRAF mutation status. Our data do not allow for a conclusion as for which method is currently the best for detection of BRAF-V600E mutation in melanomas, but indicate that IHC should be used complementary to molecular detection methods. Our findings suggest that BRAF-V600E expression is a novel prognostic marker in primary melanoma, and additional studies should be performed to confirm this finding.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Gerd Lillian Hallseth, Bendik Nordanger and Randi Hope Lavik for excellent technical assistance. This work was partly supported by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, Project Number 223250. Other funding sources were University of Bergen, Research Council of Norway (Grant # 802630), Norwegian Cancer Society (Grant # 803149) and Helse Vest Research Fund (Grant # 911873).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Akslen LA, Angelini S, Straume O, Bachmann IM, Molven A, Hemminki K, Kumar R (2005) BRAF and NRAS mutations are frequent in nodular melanoma but are not associated with tumor cell proliferation or patient survival. J Invest Dermatol 125: 312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch CM, Gershenwald J, Atkins MB (2009) Melanoma of the skin. In AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A (eds) 7th edn, pp 325–344.

- Barbour AP, Tang YH, Armour N, Dutton-Regester K, Krause L, Loffler KA, Lambie D, Burmeister B, Thomas J, Smithers BM, Hayward NK (2014) BRAF mutation status is an independent prognostic factor for resected stage IIIB and IIIC melanoma: implications for melanoma staging and adjuvant therapy. Eur J Cancer 50: 2668–2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow A (1970) Thickness, cross-sectional areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg 172: 902–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucheit AD, Syklawer E, Jakob JA, Bassett RL Jr, Curry JL, Gershenwald JE, Kim KB, Hwu P, Lazar AJ, Davies MA (2013) Clinical characteristics and outcomes with specific BRAF and NRAS mutations in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer 119: 3821–3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capper D, Preusser M, Habel A, Sahm F, Ackermann U, Schindler G, Pusch S, Mechtersheimer G, Zentgraf H, Von Deimling A (2011) Assessment of BRAF V600E mutation status by immunohistochemistry with a mutation-specific monoclonal antibody. Acta Neuropathol 122: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlino MS, Haydu LE, Kakavand H, Menzies AM, Hamilton AL, Yu B, Ng CC, Cooper WA, Thompson JF, Kefford RF, O'toole SA, Scolyer RA, Long GV (2014) Correlation of BRAF and NRAS mutation status with outcome, site of distant metastasis and response to chemotherapy in metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer 111: 292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark WH Jr., From L, Bernardino EA, Mihm MC (1969) The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res 29: 705–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomba E, Helias-Rodzewicz Z, Von Deimling A, Marin C, Terrones N, Pechaud D, Surel S, Cote JF, Peschaud F, Capper D, Blons H, Zimmermann U, Clerici T, Saiag P, Emile JF (2013) Detection of BRAF p.V600E mutations in melanomas: comparison of four methods argues for sequential use of immunohistochemistry and pyrosequencing. J Mol Diagn 15: 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombino M, Capone M, Lissia A, Cossu A, Rubino C, De Giorgi V, Massi D, Fonsatti E, Staibano S, Nappi O, Pagani E, Casula M, Manca A, Sini M, Franco R, Botti G, Caraco C, Mozzillo N, Ascierto PA, Palmieri G (2012) BRAF/NRAS mutation frequencies among primary tumors and metastases in patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol 30: 2522–2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, Davis N, Dicks E, Ewing R, Floyd Y, Gray K, Hall S, Hawes R, Hughes J, Kosmidou V, Menzies A, Mould C, Parker A, Stevens C, Watt S, Hooper S, Wilson R, Jayatilake H, Gusterson BA, Cooper C, Shipley J, Hargrave D, Pritchard-Jones K, Maitland N, Chenevix-Trench G, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Palmieri G, Cossu A, Flanagan A, Nicholson A, Ho JW, Leung SY, Yuen ST, Weber BL, Seigler HF, Darrow TL, Paterson H, Marais R, Marshall CJ, Wooster R, Stratton MR, Futreal PA (2002) Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 417: 949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devitt B, Liu W, Salemi R, Wolfe R, Kelly J, Tzen CY, Dobrovic A, Mcarthur G (2011) Clinical outcome and pathological features associated with NRAS mutation in cutaneous melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 24: 666–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehsani L, Cohen C, Fisher KE, Siddiqui MT (2014) BRAF mutations in metastatic malignant melanoma: comparison of molecular analysis and immunohistochemical expression. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 22: 648–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerhorst JA, Greene VR, Ekmekcioglu S, Warneke CL, Johnson MM, Cooke CP, Wang LE, Prieto VG, Gershenwald JE, Wei Q, Grimm EA (2011) Clinical correlates of NRAS and BRAF mutations in primary human melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 17: 229–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Casado Z, Traves V, Banuls J, Niveiro M, Gimeno-Carpio E, Jimenez-Sanchez AI, Moragon M, Onrubia JA, Oliver V, Kumar R, Nagore E (2014) BRAF, NRAS and MC1R status in a prospective series of primary cutaneous melanoma. Br J Dermatol 172(4): 1128–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman V, Ilie M, Long-Mira E, Giacchero D, Butori C, Dadone B, Selva E, Tanga V, Passeron T, Poissonnet G, Emile JF, Lacour JP, Bahadoran P, Hofman P (2013) Usefulness of immunocytochemistry for the detection of the BRAF(V600E) mutation in circulating tumor cells from metastatic melanoma patients. J Invest Dermatol 133: 1378–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihle MA, Fassunke J, Konig K, Grunewald I, Schlaak M, Kreuzberg N, Tietze L, Schildhaus HU, Buttner R, Merkelbach-Bruse S (2014) Comparison of high resolution melting analysis, pyrosequencing, next generation sequencing and immunohistochemistry to conventional Sanger sequencing for the detection of p.V600E and non-p.V600E BRAF mutations. BMC Cancer 14: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kononen J, Bubendorf L, Kallioniemi A, Barlund M, Schraml P, Leighton S, Torhorst J, Mihatsch MJ, Sauter G, Kallioniemi OP (1998) Tissue microarrays for high-throughput molecular profiling of tumor specimens. Nat Med 4: 844–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lade-Keller J, Romer KM, Guldberg P, Riber-Hansen R, Hansen LL, Steiniche T, Hager H, Kristensen LS (2013) Evaluation of BRAF mutation testing methodologies in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cutaneous melanomas. J Mol Diagn 15: 70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladstein RG, Bachmann IM, Straume O, Akslen LA (2012. a) Prognostic importance of the mitotic marker phosphohistone H3 in cutaneous nodular melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 132: 1247–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladstein RG, Bachmann IM, Straume O, Akslen LA (2012. b) Tumor necrosis is a prognostic factor in thick cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol 36: 1477–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Li Z, Wang Y, Feng Q, Si L, Cui C, Guo J, Xue W (2014) Immunohistochemical detection of the BRAF V600E mutation in melanoma patients with monoclonal antibody VE1. Pathol Int 64: 601–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Kelly JW, Trivett M, Murray WK, Dowling JP, Wolfe R, Mason G, Magee J, Angel C, Dobrovic A, Mcarthur GA (2007) Distinct clinical and pathological features are associated with the BRAF(T1799A(V600E)) mutation in primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 127: 900–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GV, Menzies AM, Nagrial AM, Haydu LE, Hamilton AL, Mann GJ, Hughes TM, Thompson JF, Scolyer RA, Kefford RF (2011) Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 29: 1239–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GV, Wilmott JS, Capper D, Preusser M, Zhang YE, Thompson JF, Kefford RF, Von Deimling A, Scolyer RA (2013) Immunohistochemistry is highly sensitive and specific for the detection of V600E BRAF mutation in melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol 37: 61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann GJ, Pupo GM, Campain AE, Carter CD, Schramm SJ, Pianova S, Gerega SK, De Silva C, Lai K, Wilmott JS, Synnott M, Hersey P, Kefford RF, Thompson JF, Yang YH, Scolyer RA (2013) BRAF mutation, NRAS mutation, and the absence of an immune-related expressed gene profile predict poor outcome in patients with stage III melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 133: 509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar VJ, Liu W, Devitt B, Wong SQ, Dobrovic A, Mcarthur GA, Wolfe R, Kelly JW (2015) The role of BRAF mutations in primary melanoma growth rate and survival. Br J Dermatol 173: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckbach D, Bauer J, Pflugfelder A, Meier F, Busch C, Eigentler TK, Capper D, Von Deimling A, Mittelbronn M, Perner S, Ikenberg K, Hantschke M, Buttner P, Garbe C, Weide B (2014. a) Survival according to BRAF-V600 tumor mutations—an analysis of 437 patients with primary melanoma. PLoS One 9: e86194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckbach D, Keim U, Richter S, Leiter U, Eigentler TK, Bauer J, Pflugfelder A, Buttner P, Garbe C, Weide B (2014. b) BRAF-V600 mutations have no prognostic impact in stage IV melanoma patients treated with monochemotherapy. PLoS One 9: e89218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies AM, Haydu LE, Visintin L, Carlino MS, Howle JR, Thompson JF, Kefford RF, Scolyer RA, Long GV (2012) Distinguishing clinicopathologic features of patients with V600E and V600K BRAF-mutant metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 18: 3242–3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CJ, Cheung M, Sharma A, Clarke L, Helm K, Mauger D, Robertson GP (2004) Method of mutation analysis may contribute to discrepancies in reports of (V599E)BRAF mutation frequencies in melanocytic neoplasms. J Invest Dermatol 123: 990–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Ramirez D, Ojeda-Vila T, Rios-Martin JJ, Nieto-Garcia A, Ferrandiz L (2015) Role of age and sex in the diagnosis of early-stage malignant melanoma: a cross-sectional study. Acta Derm Venereol 95: 940–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagore E, Requena C, Traves V, Guillen C, Hayward NK, Whiteman DC, Hacker E (2014) Prognostic value of BRAF mutations in localized cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 70: 858–862.e851-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou V, Stratigos AJ (2014) Emerging trends in the epidemiology of melanoma. Br J Dermatol 170: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocito A, Bubendorf L, Tinner EM, Suess K, Wagner U, Forster T, Kononen J, Fijan A, Bruderer J, Schmid U, Ackermann D, Maurer R, Alund G, Knonagel H, Rist M, Anabitarte M, Hering F, Hardmeier T, Schoenenberger AJ, Flury R, Jager P, Fehr JL, Schraml P, Moch H, Mihatsch MJ, Gasser T, Sauter G (2001) Microarrays of bladder cancer tissue are highly representative of proliferation index and histological grade. J Pathol 194: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritterhouse LL, Barletta JA (2015) BRAF V600E mutation-specific antibody: a review. Semin Diagn Pathol 32(5): 400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaee Ardekani G, Jafarnejad SM, Khosravi S, Martinka M, Ho V, Li G (2013) Disease progression and patient survival are significantly influenced by BRAF protein expression in primary melanoma. Br J Dermatol 169: 320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah DJ, Dronca RS (2014) Latest advances in chemotherapeutic, targeted, and immune approaches in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Mayo Clin Proc 89: 504–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si L, Kong Y, Xu X, Flaherty KT, Sheng X, Cui C, Chi Z, Li S, Mao L, Guo J (2012) Prevalence of BRAF V600E mutation in Chinese melanoma patients: large scale analysis of BRAF and NRAS mutations in a 432-case cohort. Eur J Cancer 48: 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley KS (2003) A pivotal role for ERK in the oncogenic behaviour of malignant melanoma? Int J Cancer 104: 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straume O, Akslen LA (1997) Alterations and prognostic significance of p16 and p53 protein expression in subgroups of cutaneous melanoma. Int J Cancer 74: 535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straume O, Akslen LA (2002) Importance of vascular phenotype by basic fibroblast growth factor, and influence of the angiogenic factors basic fibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 and ephrin-A1/EphA2 on melanoma progression. Am J Pathol 160: 1009–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel A, Moza M, Kytola S, Orpana A, Jahkola T, Hernberg M, Virolainen S, Ristimaki A (2014) Prospective immunohistochemical analysis of BRAF V600E mutation in melanoma. Hum Pathol 46(2): 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, Groben PA, Parrish E, Kricker A, Armstrong BK, Anton-Culver H, Gruber SB, From L, Busam KJ, Hao H, Orlow I, Kanetsky PA, Luo L, Reiner AS, Paine S, Frank JS, Bramson JI, Marrett LD, Gallagher RP, Zanetti R, Rosso S, Dwyer T, Cust AE, Ollila DW, Begg CB, Berwick M, Conway K (2015) Association between NRAS and BRAF mutational status and melanoma-specific survival among patients with higher-risk primary melanoma. JAMA Oncol 1: 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uguen A, Talagas M, Costa S, Samaison L, Paule L, Alavi Z, De Braekeleer M, Le Marechal C, Marcorelles P (2015) NRAS (Q61R), BRAF (V600E) immunohistochemistry: a concomitant tool for mutation screening in melanomas. Diagn Pathol 10: 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmott JS, Menzies AM, Haydu LE, Capper D, Preusser M, Zhang YE, Thompson JF, Kefford RF, Von Deimling A, Scolyer RA, Long GV (2013) BRAF(V600E) protein expression and outcome from BRAF inhibitor treatment in BRAF(V600E) metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer 108: 924–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Kuo H, Li WQ, Canales AL, Han J, Qureshi AA (2014) Association between BRAF (V600E) and NRAS (Q61R) mutations and clinicopathologic characteristics, risk factors and clinical outcome of primary invasive cutaneous melanoma. Cancer Causes Control 25: 1379–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancovitz M, Litterman A, Yoon J, Ng E, Shapiro RL, Berman RS, Pavlick AC, Darvishian F, Christos P, Mazumdar M, Osman I, Polsky D (2012) Intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity of BRAF(V600E))mutations in primary and metastatic melanoma. PLoS One 7: e29336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.