Summary

The E3 ubiquitin ligase PARKIN (encoded by PARK2) and the protein kinase PINK1 (encoded by PARK6) are mutated in autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinsonism (AR-JP) and work together in the disposal of damaged mitochondria by mitophagy1–3. PINK1 is stabilised on the outside of depolarised mitochondria, and phosphorylates poly-ubiquitin (polyUb)4–8 as well as the PARKIN Ub-like (Ubl) domain9,10. These phosphorylation events lead to PARKIN recruitment to mitochondria, and activation by an unknown allosteric mechanism4–12.

Here we present the crystal structure of Pediculus humanus PARKIN in complex with Ser65-phosphorylated ubiquitin (phosphoUb), revealing the molecular basis for PARKIN recruitment and activation. The phosphoUb binding site on PARKIN comprises a conserved phosphate pocket and harbours residues mutated in AR-JP patients. PhosphoUb binding leads to straightening of a helix in the RING1 domain, and the resulting conformational changes release the Ubl domain from the PARKIN core; this activates PARKIN. Moreover, phosphoUb-mediated Ubl release enhances Ubl phosphorylation by PINK1, leading to conformational changes within the Ubl domain and stabilisation of an open, active conformation of PARKIN. We redefine the role of the Ubl domain not only as an inhibitory13 but also as an activating element that is restrained in inactive PARKIN and released by phosphoUb. Our work opens new avenues to identify small molecule PARKIN activators.

The RING-between-RING E3 ligase PARKIN contains a RING1 domain that binds ubiquitin (Ub)-charged E2 enzymes, and transfers Ub from the E2 to an active site Cys residue in the RING2 domain and subsequently to a substrate. Cytosolic PARKIN exists in an autoinhibited, “closed” conformation13–16, in which binding to E2 is blocked by the N-terminal Ub-like (Ubl) domain as well as by a ‘Repressor’ element (REP), and access to the RING2 active site Cys is blocked by the Unique PARKIN Domain (UPD, also known as RING0)(Extended Data Fig. 1). PhosphoUb binding and/or PARKIN Ubl phosphorylation are presumed to induce conformational domain rearrangements to activate PARKIN13–16, however the mechanism and sequence of events are unclear. Once activated, PARKIN ubiquitinates numerous mitochondrial and cytosolic proteins17, eventually triggering mitophagy.

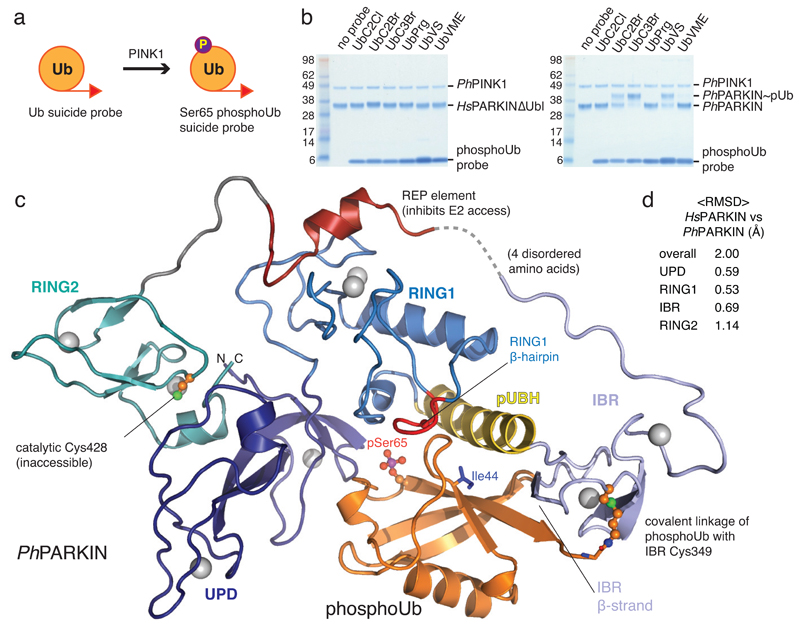

To understand how phosphoUb induces PARKIN activation, we used PINK1-phosphorylated ‘Ub suicide probes’18 that can modify Cys residues near a Ub binding site in vitro19 (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1d). Probes could not modify a previously crystallised construct of human PARKIN lacking the Ubl domain14 (HsPARKINΔUbl, aa 137-465) (Fig. 1b). Unexpectedly, a similar fragment of Pediculus humanus corporis (human body louse) PARKIN (aa 140-461, hereafter PhPARKIN) was modified by a subset of phosphoUb suicide probes (Fig. 1b), enabling purification of the PhPARKIN~pUb complex and determination of a crystal structure at 2.6 Å resolution (Fig. 1c, Methods, , Extended Data Fig. 1e, 2a). PhPARKIN~pUb resembles autoinhibited structures of HsPARKIN (Fig. 1c, 1d, Extended Data Fig. 2e), with key differences as described below. The phosphoUb suicide probe had modified Cys349 in the PhPARKIN IBR domain (Fig. 1c, 2a), which in HsPARKIN corresponds to probe-unreactive Gln347. Notably, HsPARKIN Q347C is modified by phosphoUb suicide probes (Fig. 2b), indicating a similar binding mode of phosphoUb in HsPARKIN. Hence, our complex structure serves as model for phosphoUb binding to HsPARKIN.

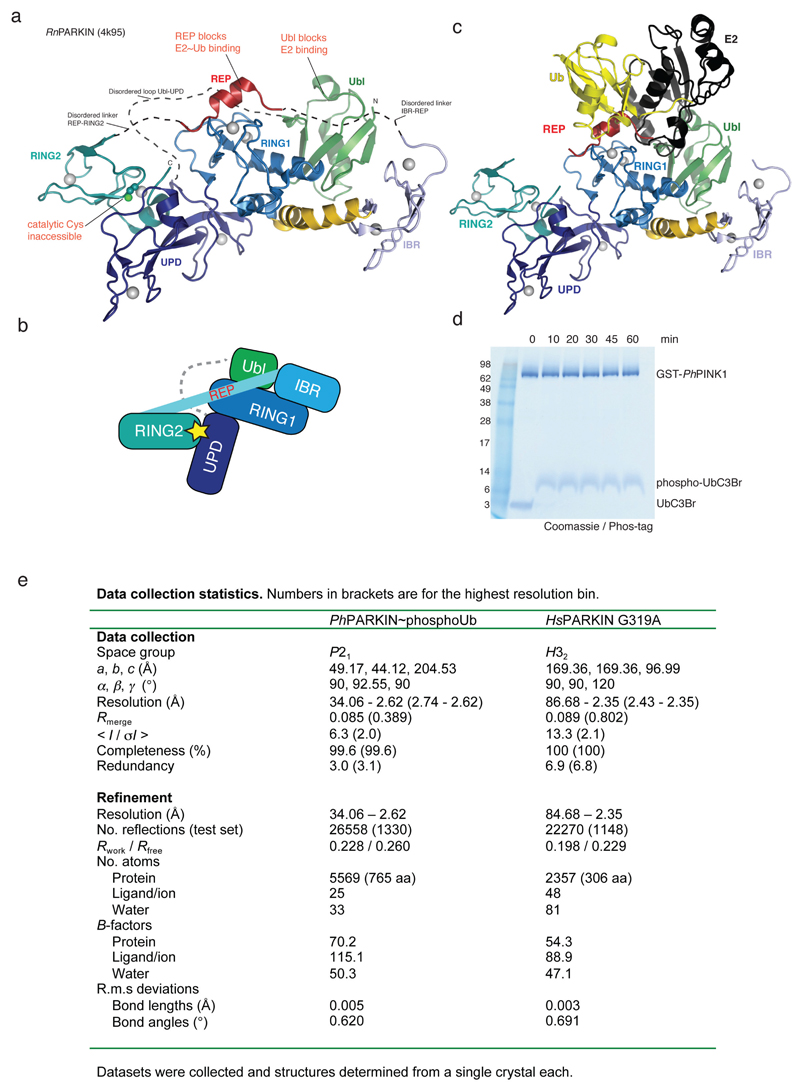

Figure 1. Generation and structure of PhPARKIN-phosphoUb complex.

(a) Schematic of generating phosphoUb suicide probes used in this study. (b) HsPARKINΔUbl (left, aa 137-465) and PhPARKIN (right, aa 140-461) were incubated with indicated Ub suicide probes18 for 1 h in presence of PhPINK1 (Methods, Extended Data Fig. 1d) and resolved on Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE gels. UbC2Cl, Ub chloroethylamine; UbC2Br, Ub bromoethylamine; UbC3Br, Ub bromopropylamine; UbPrg, Ub propargyl; UbVS, Ub vinylmethylsulphone; UbVME, Ub vinylmethylester. The experiment was performed three times with consistent results. (c) Structure of the PhPARKIN~pUb complex with domains coloured from blue to cyan (UPD, RING1, IBR, RING2), grey zinc atoms, red REP, yellow phosphoUb binding helix (pUBH), and orange phosphoUb. The Catalytic Cys in RING2, and key phosphoUb residues are indicated. (d) RMSD values for PhPARKIN in comparison to HsPARKIN (pdb-id 4bm9, 14).

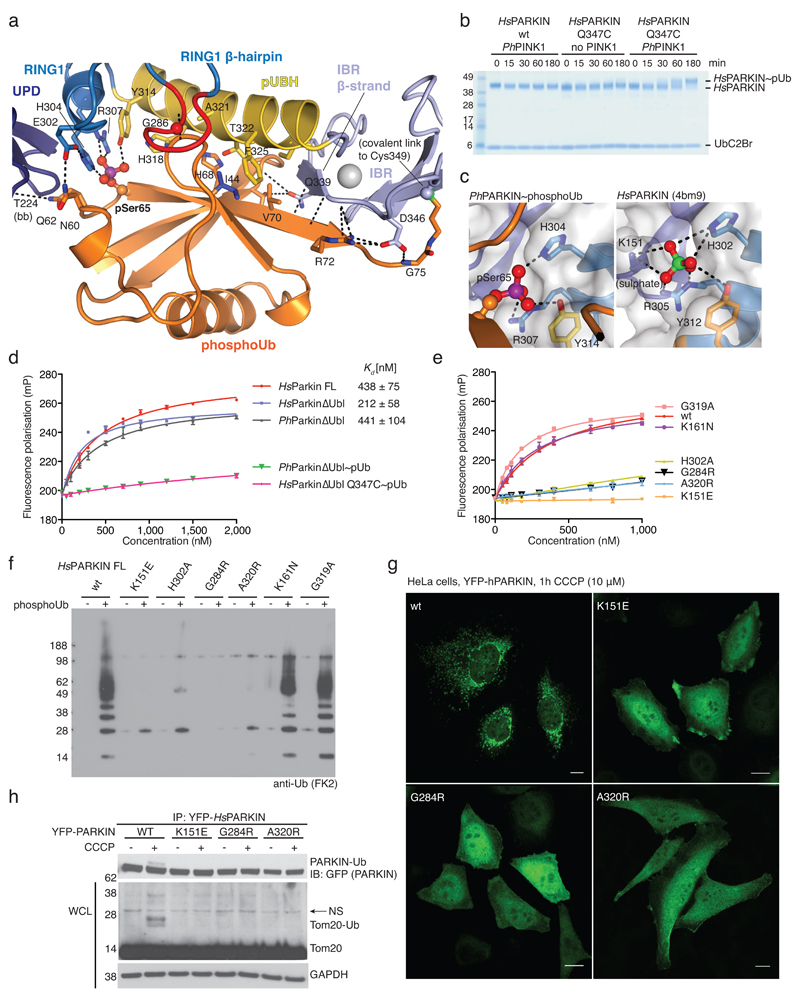

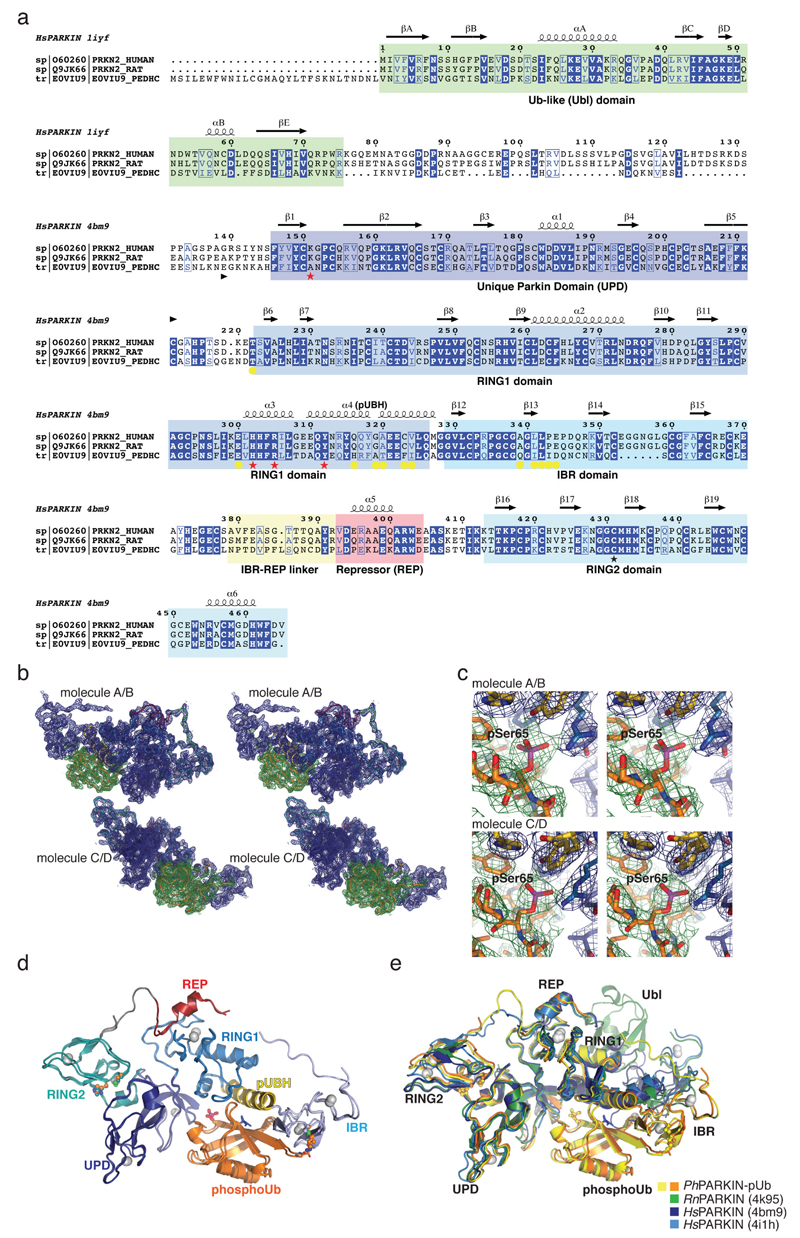

Figure 2. PhosphoUb binding to PARKIN.

(a) PhosphoUb binding site on PhPARKIN as in Fig. 1c. Dotted lines indicate hydrogen bonds. The RING1 β-hairpin that harbours patient mutations, is highlighted in red. bb, backbone contacts. (b) PhosphoUb suicide probe reactions as in Fig. 1b with UbC2Br and GST-PhPINK1. The experiment was performed three times with consistent results. (c) (Left) Occupied Ser65 phosphate pocket in PhPARKIN, (right) identical pocket in HsPARKIN occupied by a sulphate ion in PDB 4bm9 14. (d) Fluorescence polarisation experiments characterizing the binding of FlAsH-tagged phosphoUb to PARKIN variants. Measurements were performed in triplicate and error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. mP, milli-polarization unit. (e) Binding assays as in d with full-length HsPARKIN and mutants in the phosphoUb binding site. Binding curves were compiled from experiments shown in Extended Data Fig. 3d. Measurements were performed in triplicate and error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. (f) Activity assays of full-length HsPARKIN variants with and without phosphoUb. After 2 h, reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and polyubiquitin visualised by anti-polyubiquitin Western blotting (FK2, Millipore). PARKIN protein normalization is shown in Extended Data Fig. 3e. The experiment was performed three times with consistent results. (g) YFP-HsPARKIN wt or mutants were transfected into HeLa cells, treated with CCCP (10 µM) for 1 h and visualised by immunofluorescence. See Extended Data Fig. 4 for controls and quantification. Scale bar, 10 μm. (h) HeLa cell lysates expressing YFP-HsPARKIN wt or mutants were western blotted for PARKIN (after immunoprecipitation (IP)) and Tom20 (in whole-cell lysate (WCL)). NS, non-specific band. The experiment was performed at least twice as biological replicate for every mutant with consistent results. See Extended Data Fig. 4d and Supplementary Information.

PhosphoUb forms an extended interface (1150 Å2, 25% of Ub surface) with the RING1 and IBR domains in PhPARKIN, and also interacts with side chains of the UPD (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3). Key interactions are formed (i) via the phosphate group, which is located in a pocket formed by His304, Arg307 and Tyr314 of PhPARKIN (Fig. 2c), (ii) via the hydrophobic Ile44 patch of phosphoUb, which binds to an extended helix in the RING1 domain (aa 311-329, hereafter referred to as phosphoUb binding helix, pUBH), (iii) via a conserved surface β-hairpin loop (aa 280-288) in RING1 that harbours AR-JP mutations and (iv) via the phosphoUb C-terminus, which forms an intermolecular parallel β-sheet with the second β-strand of the IBR domain (Fig. 1c, 2a). Most residues forming phosphoUb interactions in PhPARKIN are conserved in HsPARKIN (Extended Data Fig. 3a-c), and in our previous HsPARKIN structure14 the phosphate pocket is occupied by a sulphate molecule from the crystallization condition (Fig. 2c).

A fluorescence polarisation based phosphoUb binding assay revealed sub-micromolar interactions of phosphoUb with full-length HsPARKIN, HsPARKINΔUbl and PhPARKIN (Fig. 2d). Modification with phosphoUb suicide probes of PhPARKIN or HsPARKIN Q347C (HsPARKIN Q347C~pUb) abrogated phosphoUb binding (Fig. 2d), indicating that the covalently bound phosphoUb molecule satisfied the major phosphoUb binding site.

Mutations in the predicted phosphoUb interface in HsPARKIN reduced or abrogated phosphoUb binding (Fig. 2e, Extended Data Fig. 3d). HsPARKIN K151E (in the phosphate pocket, Fig. 2c, Ala152 in PhPARKIN), A320R (pUBH, Thr322 in PhPARKIN, Fig. 2a) or G284R (β-hairpin, Gly286 in PhPARKIN, Fig. 2a) abrogated phosphoUb binding (Fig. 2e). HsPARKIN G284R is an AR-JP derived patient mutation, and our data provides a rationale for how this mutation leads to defects in PARKIN function (see below). Similarly, AR-JP mutation L283P20 and cancer-associated H279P21 in this region might also disrupt this loop and affect phosphoUb binding to HsPARKIN.

PARKIN activity can be assessed in autoubiquitination assays4–7,14. HsPARKIN was activated by phosphoUb, whereas HsPARKIN K151E, H302A, A320R or G284R showed impaired phosphoUb-induced activation (Fig. 2f). HsPARKIN K161N (an AR-JP mutation on the UPD14, see below) and HsPARKIN G319A (see below) bound to and were activated by phosphoUb (Fig. 2e-f, Extended Data Fig. 3d-e).

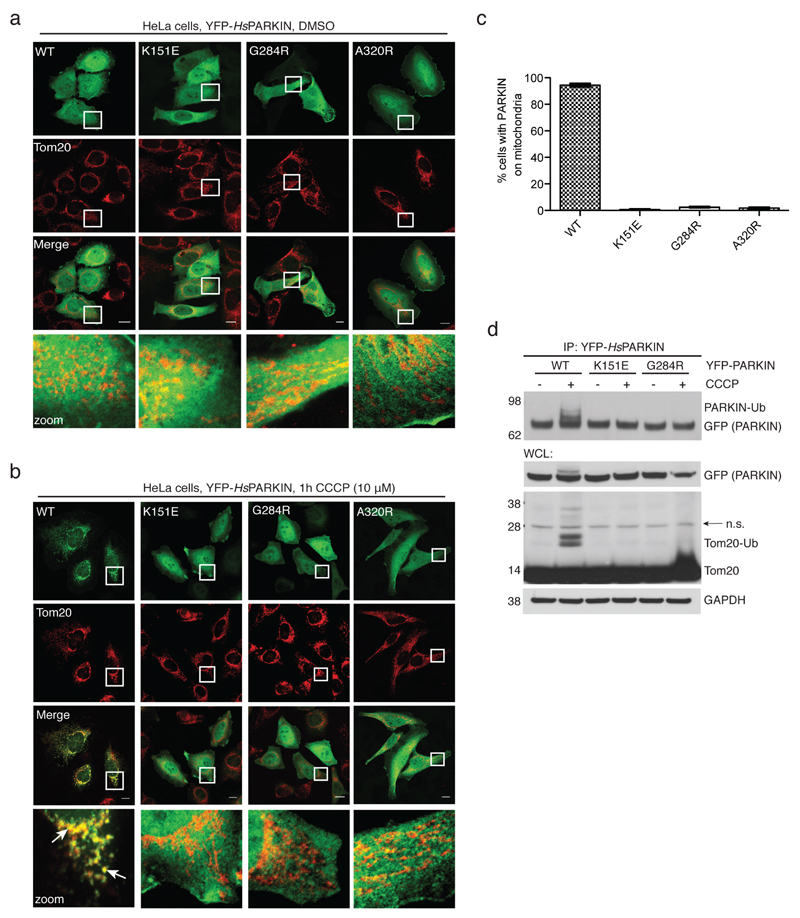

In HeLa cells, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP)-mediated depolarisation of mitochondria led to rapid mitochondrial localisation of YFP-tagged HsPARKIN, while phosphoUb-binding mutants did not show mitochondrial localisation (Fig. 2g, Extended Data Fig. 4a-c). Moreover, wild-type HsPARKIN ubiquitinated endogenous Tom20 after CCCP treatment, while phosphoUb-binding mutants showed no apparent activity (Fig. 2h, Extended Data Fig. 4d).

Hence, we reveal the phosphoUb binding site in PARKIN, which is conserved in the most divergent species, harbours AR-JP patient mutations and is important for PARKIN localisation in cells (Fig. 2). This provides the molecular basis for PARKIN translocation to mitochondrial phosphoUb7,11,22 (Extended Data Fig. 3g).

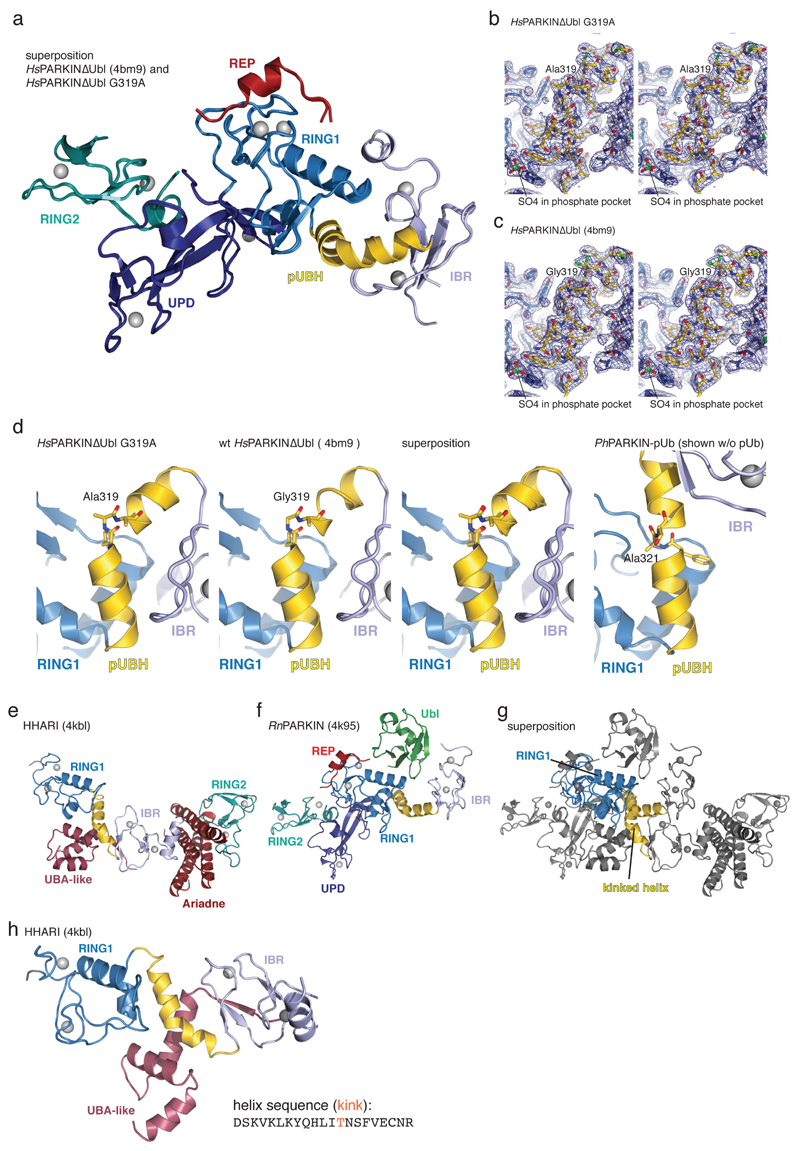

Next we addressed the question of how phosphoUb activates PARKIN. PhosphoUb binds to a straight helix, pUBH, in PhPARKIN (Fig. 2, 3). In previous PARKIN structures14–16 this helix is kinked at Gly319 (Ala321 in PhPARKIN). The distinct conformation of the pUBH does not originate from this sequence difference; a crystal structure of HsPARKINΔUbl G319A still shows a kinked pUBH conformation (Extended Data Fig. 1e, 5) and HsPARKIN wild type and G319A have similar biochemical properties (Fig. 2e,f, Extended Data Fig. 3d-e). Interestingly, RING1 of the RBR E3 ligase HHARI23 also features a kinked helix in the autoinhibited state (see Extended Data Fig. 5e-h).

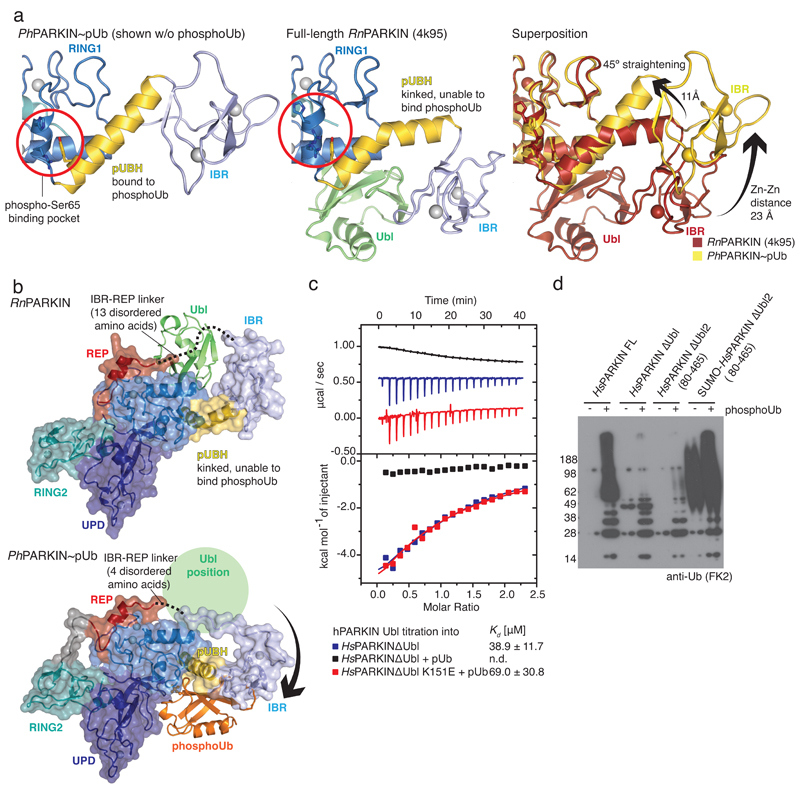

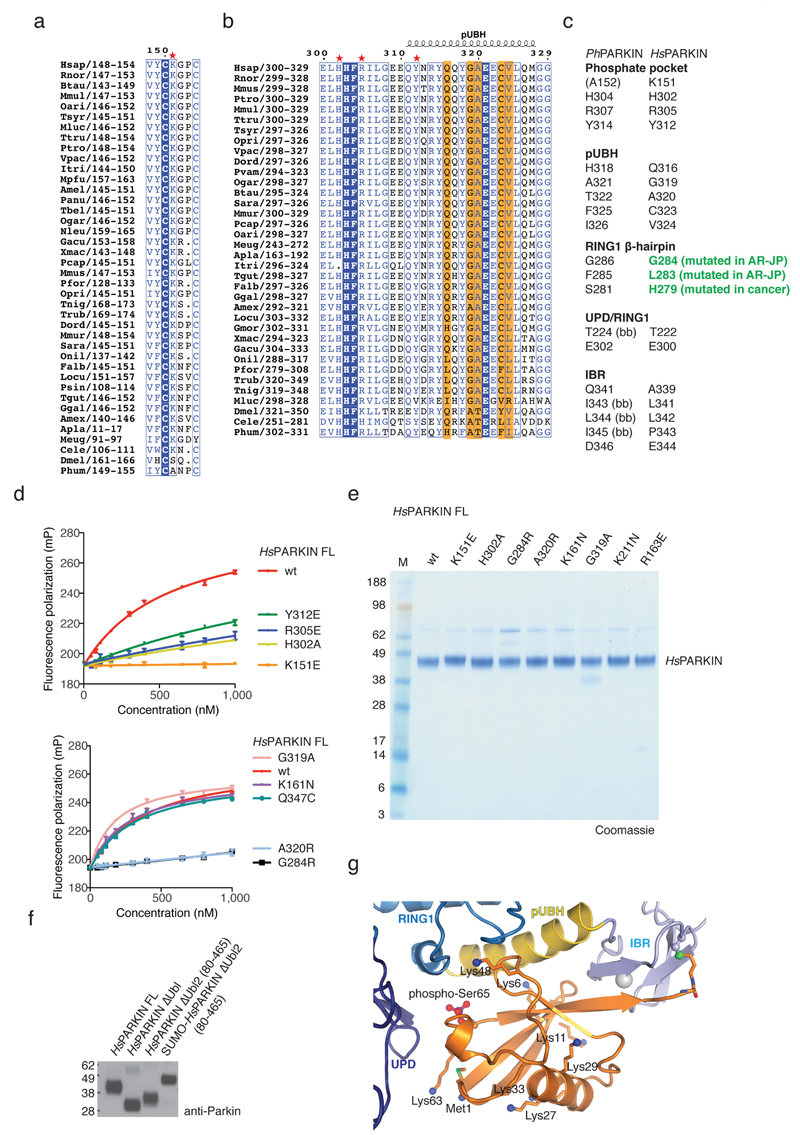

Figure 3. Conformational changes due to phosphoUb binding.

(a) Straight pUBH in PhPARKIN~pUb (left) vs. kinked pUBH in previous PARKIN structures (middle, shown is full-length RnPARKIN, pdb-id 4k95, 16). Superposition indicating IBR repositioning by >20Å (right). (b) Full-length RnPARKIN (top) with core domains under a transparent surface and Ubl as green cartoon, and PhPARKIN~pUb (bottom),with a green circle indicating the putative Ubl binding site; phosphoUb in orange. (c) ITC experiment titrating HsPARKIN Ubl domain into HsPARKINΔUbl without phosphoUb (blue curve, Kd ~39 µM), with phosphoUb present (black curve, Kd not detectable (n.d.)), and HsPARKIN K151E with phosphoUb present (red curve, Kd ~69 µM). Heat release curves (top panel) were shifted in their y-axis position for better visibility. Dissociation constant and curve fitting errors are indicated. All measurements were performed three times with consistent results. (d) Activity of full-length HsPARKIN, HsPARKINΔUbl (137-465), HsPARKINΔUbl2 (80-465) and SUMO-tagged HsPARKINΔUbl2 (80-465) without or with phosphoUb for 1 h (see Fig. 2f, Extended Data Fig. 3f). Experiments were performed three times with consistent results.

A kinked helix would be unable to bind phosphoUb, leading to a model in which the pUBH is dynamic and straightens upon phosphoUb binding. pUBH straightening hardly affects RING1 (Extended Data Fig. 6a) but impacts on the position of the IBR domain (Fig. 2, 3a-b), which rotates and moves by >20 Å as compared to full-length RnPARKIN16 (Fig. 3a). The conformational change stretches the IBR-REP linker (14-15 aa, Extended Data Fig. 2a) from spanning 31 Å in RnPARKIN to cover a distance of 43 Å in PhPARKIN~pUb (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 6b). This appears to destabilise inhibitory interactions of REP and RING2 as suggested by increased B-factors for these domains in PhPARKIN~pUb (Extended Data Fig. 6c-d).

More importantly, phosphoUb binding also destabilises the interface between the PARKIN Ubl domain and the RBR core, due to displacement of the IBR domain and reorganisation of the IBR-REP linker that no longer spans the Ubl surface (Fig. 3b). Using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), we detected binding of isolated HsPARKIN Ubl (aa 1-72) to HsPARKINΔUbl in trans (Fig. 3c, Kd ~40 µM). Importantly, binding is undetectable in presence of phosphoUb, but recovered with phosphoUb-binding deficient HsPARKINΔUbl K151E mutant (Fig. 3c). Hence, phosphoUb binding releases the Ubl from the PARKIN RBR core.

PARKIN variants lacking the Ubl domain are still autoinhibited14–16, and less well activated by phosphoUb, in comparison to full-length PARKIN7 (Fig. 3d). This indicates that presence of the Ubl domain is important for full PARKIN activity. Interestingly, replacing the Ubl domain (aa 1-79) with SUMO, which lacks a Ubl-like hydrophobic patch and would not bind RING1, activates PARKIN constitutively, even in absence of phosphoUb. This suggests that the released Ubl domain actively helps to unravel the autoinhibited PARKIN conformation. This, together with destabilisation of the REP and RING2 autoinhibitory interactions, enables RING1 to bind and discharge E2~Ub conjugates4, and explains how PARKIN is activated by phosphoUb.

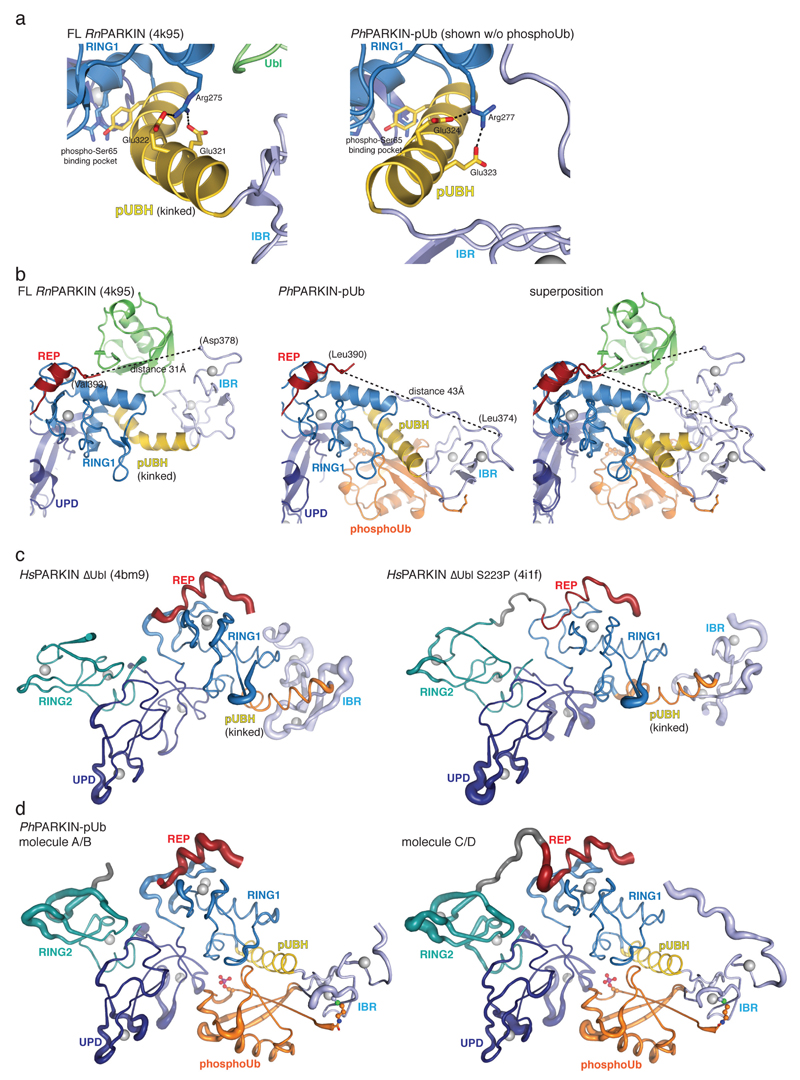

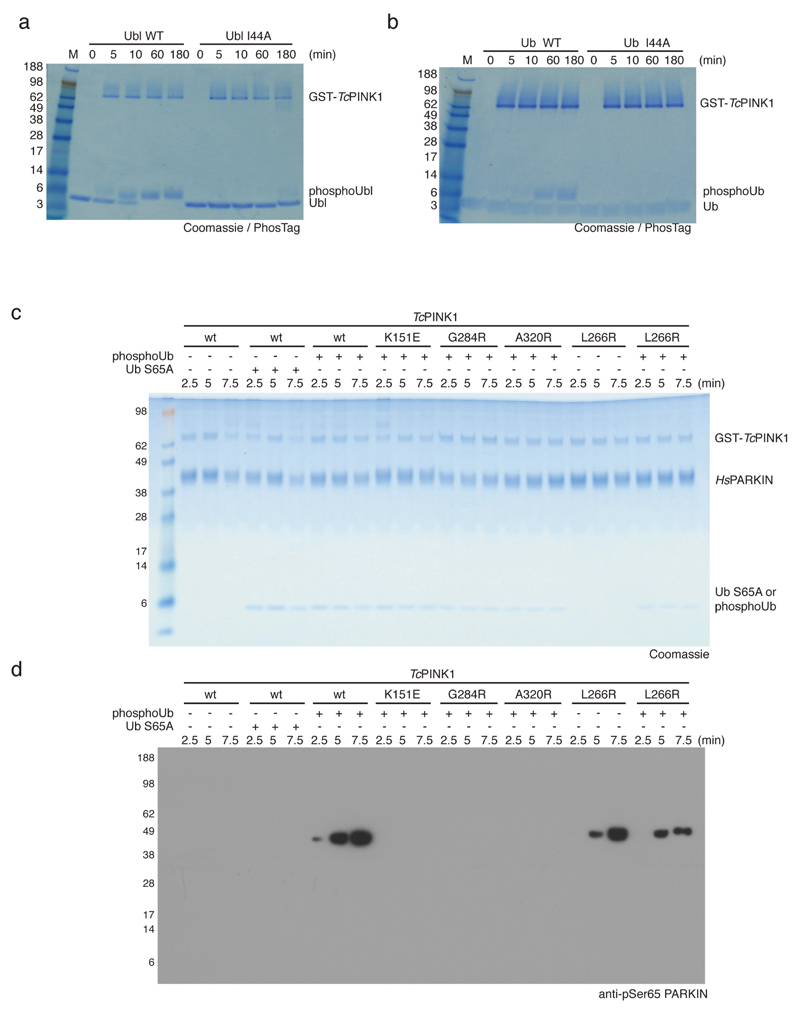

An alternative mechanism to activate PARKIN is PINK1-mediated phosphorylation of Ser65 in the Ubl domain7,9,10, which was also suggested to release the Ubl domain from the PARKIN core9,24. In the closed conformation of PARKIN, the Ubl domain binds via its Ile44 patch to RING113,16 (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 1). Importantly, PINK1 did not phosphorylate HsPARKIN Ubl I44A (or ubiquitin I44A) efficiently (Extended Data Fig. 7a-b). This suggests that PARKIN and PINK1 utilise overlapping binding sites on the Ubl domain, and that the Ubl has to be released from the PARKIN core for PINK1 to access and phosphorylate it.

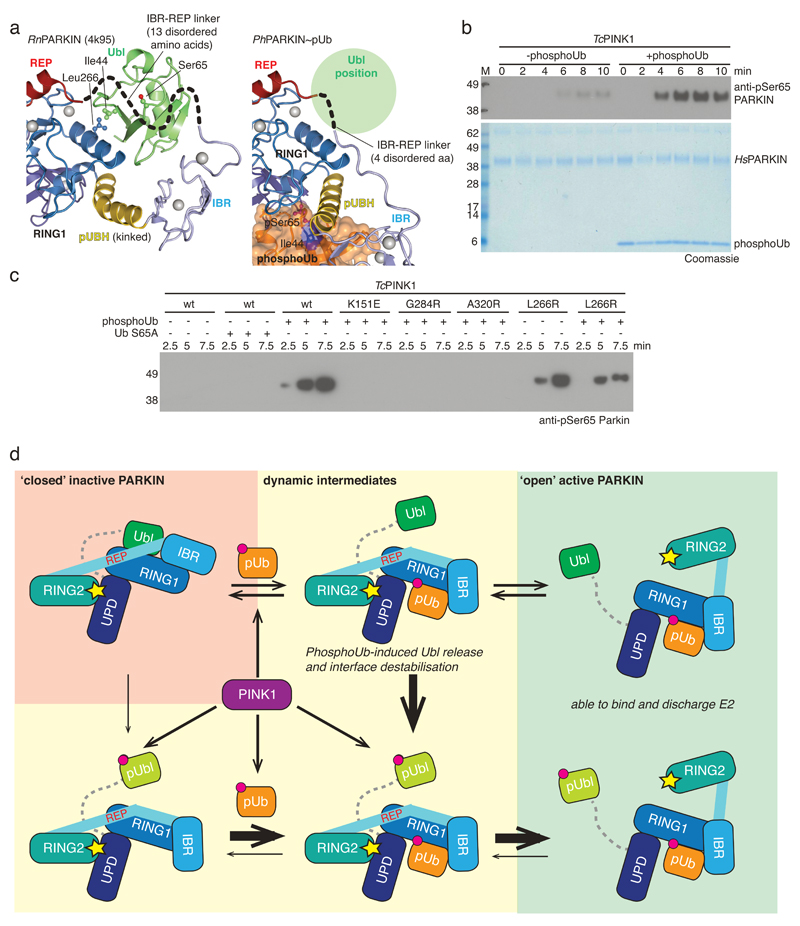

Figure 4. PhosphoUb induces PARKIN Ubl phosphorylation and model of PARKIN activation.

(a) Detail of the Ubl position on PARKIN. Ubl Ile44 and interacting Leu266 on RING1 are highlighted. The mostly disordered IBR-REP linker hovers atop Ser65 and moves out of the way in PhPARKIN~pUb (compare Fig. 3b). (b) Time course of phosphorylation of HsPARKIN by GST-TcPINK1 (Tribolium castaneum PINK1), in absence and presence of phosphoUb at 37°C, visualised with anti-pSer65 PARKIN antibody (Abcam cat no. ab154995) (top) and Coomassie (below). The experiment was performed three times with consistent results. (c) Experiment as in b but performed at 22°C with lower phosphoUb concentration (5.8 μM). The experiment was performed three times with consistent results. Also see Extended Data Fig. 7c-d. (d) Model of PARKIN activation. PARKIN is autoinhibited (top left) by multiple mechanisms (Extended Data Fig. 1). Inactive PARKIN can interact with phosphoUb, which releases the Ubl domain, destabilises inhibitory interactions and ‘opens’ PARKIN (top row). This process is reversible. PARKIN is phosphorylated by PINK1, either directly (bottom left) or with improved kinetics after phosphoUb binding (bottom middle). Phosphorylated Ubl undergoes a conformational change (Extended Data Fig. 8), probably preventing it from reverting back to the autoinhibited state. Phosphorylation of PARKIN hence stabilises an open, active conformation (bottom right). Thickness of arrows indicates preferred routes. Further information on role of Ubl phosphorylation is in Extended Data Fig. 9 and 10.

Consistently, using a phosphospecific antibody against PARKIN phospho-Ser65 (anti-pSer65 PARKIN), we found that PARKIN phosphorylation is significantly enhanced when phosphoUb is added to the reaction (Fig. 4b-c, Extended Data Fig. 7c-d), and this depends on Ub phosphorylation and phosphoUb binding (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 7c-d). Induced release of the Ubl domain by mutating the binding site on RING1 (HsPARKIN L266R, Fig. 4a) leads to phosphorylation by PINK1 in absence of phosphoUb (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 7c-d), indicating that Ubl release is crucial for enhanced phosphorylation. These results reveal a new function for phosphoUb, namely to enable phosphorylation of the Ubl (Fig. 4). However, PINK1 can phosphorylate PARKIN in absence of phosphoUb in vitro (albeit inefficiently, Fig. 4b) and in cells7,25, showing that PARKIN is a dynamic molecule (Fig. 4d) in which the Ubl domain is partially accessible by PINK1.

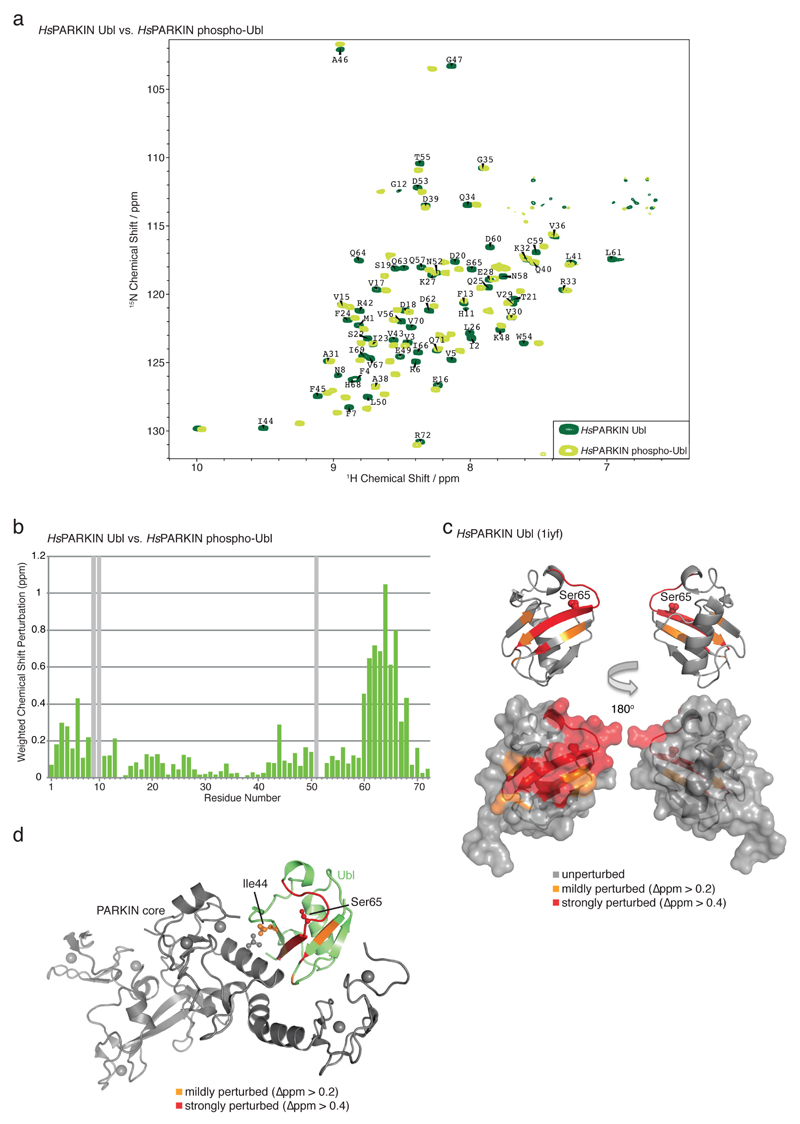

We next examined consequences of Ubl phosphorylation in HsPARKIN. Nuclear magnetic resonance measurements reveal that the Ubl undergoes significant changes when phosphorylated, in particular in the Ser65 loop and the Ile44 patch (Extended Data Fig. 8). Disruption of the Ile44 patch prevents re-binding of the Ubl to RING1, and probably stabilises a more open, active conformation of PARKIN13,24. Moreover, this may also explain why the phosphorylated Ubl cannot compete with phosphoUb for the phosphoUb binding site (Extended Data Fig. 9). Phosphorylated HsPARKIN does not impede binding of phosphoUb, but rather enhances it7 (Extended Data Fig. 9).

Together, this completes our model of PARKIN activation (Fig. 4d). Autoinhibited PARKIN (top left) responds to phosphoUb on mitochondria, which releases the Ubl to activate PARKIN in a reversible manner (top row). PINK1 phosphorylates PARKIN preferentially when the Ubl is released (bottom middle), and this leads to irreversible PARKIN activation (bottom right). Alternatively, inactive PARKIN may be phosphorylated by PINK1 directly7,25 (bottom left); this improves phosphoUb binding, retains PARKIN on mitochondria, and irreversibly activates PARKIN (bottom row).

The conformation of fully active PARKIN remains elusive. Phosphorylated PARKIN but not phosphoUb-activated PARKIN, exposes its active site Cys residue7 (Extended Data Fig. 10), further indicating that PARKIN phosphorylation leads to ‘opening’ of PARKIN. Interestingly, mutations in a putative second phosphate pocket in the UPD, which we reported previously14 and which is distinct from the pocket involved in phosphoUb binding, prevented phospho-Ubl induced PARKIN opening and activation (Extended Data Fig. 10c-d). The functional link between PARKIN phosphorylation and a putative phosphate binding pocket in the UPD may suggest that the phosphorylated Ubl binds back to the UPD; however, alternative activation mechanisms or the involvement of the Ubl-UPD linker cannot be excluded.

Our work is consistent with suggested models of PARKIN mediated mitophagy 7,25–28 and provides a structural understanding for phosphoUb binding and allosteric PARKIN activation. We refine the role of the PARKIN Ubl as an essential activating element that is restrained in autoinhibited PARKIN. The model ensures tight temporal and spatial regulation of PARKIN activity, and incorporates a commitment step whereby PARKIN phosphorylation locks PARKIN in the active, open conformation. Our insights may prove useful pharmacologically, since small molecules that dislodge the PARKIN Ubl from the PARKIN core may activate PARKIN and benefit patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

HsPARKIN full-length, HsPARKINΔUbl (aa 137-465), PhPARKIN (aa 140-461), PhPINK1 (aa 115-575) as well as Triboleum casteneum PINK1 (TcPINK1, aa 128-570) were expressed as GST-fusion proteins in Rosetta2 pLacI cells from pOPIN-K vectors as described14. In short, PARKIN cultures were induced by adding 200 μM ZnCl2 and 50 μM IPTG, whereas PINK1 variants and the PARKIN Ubl domain (aa 1-72) were induced with 150 μM IPTG followed by 12 h expression at 18°C. After harvest, the cell pellet was lysed by sonication in Lysis buffer (270 mM sucrose, 10 mM glycerol 2-phosphate disodium, 50 mM NaF, 14 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0)), in the presence of lysozyme, DNAseI and EDTA-free protease inhibitors. The suspension was centrifuged and the supernatant applied to Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare). After 1 h of agitation at 4°C the beads were washed with high salt buffer (500 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 25 mM Tris (pH 8.5)) and equilibrated in low salt buffer (200 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 25 mM Tris (pH 8.5)). GST-tagged proteins were either eluted from beads with low salt buffer containing 40 mM glutathione and purified by gel filtration (Superdex 200, GE Life Sciences), or cleaved on beads by incubating with GST-3C protease for 12 h at 4°C prior to further purification by gel filtration (Superdex 75, GE Life Sciences) in low salt buffer as a final step. When improved purity was necessary, such as for PhPARKIN used in crystallization, anion exchange (RESOURCE Q, GE Life Sciences) eluted with a linear gradient of 75-600 mM NaCl in 10 mM DTT, 25 mM Tris (pH 8.5) was included before final gel filtration.

N-terminally His6-SUMO-tagged HsPARKINΔUbl2 (aa 80-465) was expressed as described above and lysed in His6-lysis buffer (200-300 mM NaCl, 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 25 mM Tris (pH 8.5)). After centrifugation, the protein was affinity purified with Talon Superflow resin (GE Healthcare) and eluted in 200 mM NaCl, 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 25 mM Tris (pH 8.5) containing 200-250 mM imidazole. Elute protein was directly applied to gel filtration (Superdex 75, GE Life Sciences) in low salt buffer. Protein for SUMO-tag cleavage was dialyzed over night in 200 mM NaCl, 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 25 mM Tris (pH 8.5) containing His6-tagged SENP1. The sample was reapplied to Talon resin, and the flow-through purified by gel filtration (Superdex 75, GE Life Sciences) in low salt buffer.

Phospho-HsPARKIN for biochemical assays was generated by incubating 32-37 μM HsPARKIN, 5.4 μM GST-PhPINK1 and 10 mM ATP with 1x ligation buffer (40 mM Tris pH7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.6 mM DTT) for 1 h at room temperature. GST-PhPINK1 was removed with Glutathione Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare) and HsPARKIN was re-purified by gel filtration (Superdex 75, GE Life Sciences). Consistent phosphorylation levels were checked by western blot analysis using an anti-pSer65 PARKIN antibody (Abcam cat no. ab154995).

Modification with Ub-based suicide probes

Probe reactions for biochemical assays were performed by incubating 5 μM PARKIN with 40 μM indicated Ub suicide probe (Fig. 1b/2b) or 20 μM Ub-VS (Extended Data Fig. 10), 1 μM PhPINK1 where indicated and 5 μM phosphoUb where indicated in the presence of 1x reaction buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2). The reaction took place at room temperature after adding 10 mM ATP and was quenched by adding LDS sample buffer at the indicated time points. Samples were applied on NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and stained with Instant Blue SafeStain (Expedeon).

To generate the covalent PhPARKIN~pUb complex for crystallization, 46 μM PhPARKIN (aa 140-461) was reacted with 230 μM UbC3Br probe and 23 μM GST-PhPINK1 in the presence of 1x reaction buffer. The coupling was initiated by adding 10 mM ATP and incubated for 6 h at room temperature. The complex was purified by gel filtration (Superdex 75, GE Life Sciences) in low salt buffer. Fractions containing PhPARKIN~pUb were pooled, concentrated and used for crystallization without freezing.

Crystallization, data collection and refinement

PhPARKIN~pUb was crystallized in sitting-drop vapour diffusion at a concentration of ~5.3 mg/ml at 18°C. Crystals were grown in 100 nl protein solution mixed with 100 nl mother liquor (2% (v/v) PEG400, 2 M NH4SO4, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5). Prior to vitrification, crystals were soaked in 1.7% (v/v) PEG400, 15% (v/v) glycerol, 1.7 M ammonium sulphate, 0.085 M HEPES (pH 7.5) for cryo-protection. Diffraction data were collected at the Diamond Light Source (Harwell, UK), beamline I04, at 100K and a wavelength of 0.97949 Å, to a resolution of 2.62 Å.

The HsPARKINΔUbl (aa 137-465) G319A mutant was crystallized at a concentration of 2.4 mg/ml by mixing 400 nl protein solution with 400 nl mother liquor (1.8 M lithium sulphate, 0.01 M MgCl2, 0.05 M MES pH 5.6) in a sitting-drop vapour diffusion set-up at 18°C. Before vitrification in liquid nitrogen the crystals were briefly soaked in 1.6 M lithium sulfate, 0.01 M MgCl2, 0.05 M MES pH 5.4 containing 15% (v/v) glycerol. Diffraction data were collected at the Diamond Light Source (Harwell, UK), beamline I04-1, at 100K and a wavelength of 0.91730 Å, to a resolution of 2.35 Å.

Phasing of the PhPARKIN~pUb dataset was performed by molecular replacement with Phaser29 using isolated domains of HsPARKINΔUbl (pdb-id 4bm9, ref. 14) and Ub (pdb-id 1ubq, 30) as search models. The structure of HsPARKINΔUbl G319A was solved by using HsPARKINΔUbl (pdb-id 4bm914) as a refinement model. Subsequent rounds of model building in coot 31 and refinement in Phenix32 resulted in a final models with statistics shown in Extended Data Fig. 1e. The HsPARKINΔUbl G319A structure was refined with simulated annealing to reduce model bias. All structures were refined with TLS, using different protein chains as individual TLS groups. Final Ramachandran statistics were 95.3% / 4.7% / 0.0% (favoured / allowed / outliers) for the HsPARKIN G319A mutant structure, and 96.7% / 3.2% / 0.1% for the PhPARKIN~pUb structure. Structure figures were generated with PyMol (www.pymol.org).

Fluorescence polarisation phosphoUb binding assays

N-terminally FlAsH-tagged Ub was phosphorylated and purified as described for phosphoUb 8 with buffers supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol. Labelling was performed over night at 4°C with 60 μM FlAsH-tagged phosphoUb at a ratio of 37.5:1 (v/v) with Lumio Green (Invitrogen) in 1xFlAsH-dilution-buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Buffer exchange was performed with PD-10 desalting columns (GE Healthcare) in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and samples were concentrated to ~8 μM FlAsH labelled phosphoUb. For binding studies in 384-well low volume plates (Corning), 10 μl of 100 nM labelled phosphoUb was mixed with 10 μl of PARKIN serial dilutions in FlAsH-buffer (20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin). Fluorescence polarisation (FP= (I‖ - I⊥) / (I‖ + I⊥)) was measured using a PheraStar plate reader (BMB Labtech) with the optic module set to λex = 485 nm and λem = 520 nm. Measurements were performed in triplicate and error bars are given as the standard deviation from the mean. A least square fit for one binding site was performed using the following equation: FP=(Bmax*X/(Kd+X)) + NS*X + Background

With FP being fluorescence polarisation and X the concentration of the titrant, Bmax is the maximum specific binding, Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant and NS the slope for nonspecific binding, which was restricted to values greater than 0.

PARKIN activity assays

Spin filtered HsPARKIN (2 μM) was pre-incubated for 0.5 h at 30°C with 10 mM ATP, 1x ligation buffer (40 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM magnesium chloride, 0.6 mM dithiothreitol), a total concentration of 0.5 mg/ml Ub and 0.05 mg/ml phosphoUb or 0.1 μM GST-TcPINK1 where indicated. Ubiquitination was initiated by adding 0.1 μM E1 and 1 μM UBE2L3 (Fig. 2f, Extended Data Fig. 10d) or 0.2 μM E1 and 2 μM UBE2L3 (Fig. 3d). The reaction was quenched with LDS sample buffer containing DTT and iodoacetamide to prevent forming of disulphide bridges. NuPAGE 4-12% gradient Bis-Tris gels were used for separation and proteins were transferred on a nitrocellulose membrane with subsequent detection using an anti-polyUb FK2 antibody (Millipore).

Immunofluorescence

HeLa cells (originating from ATCC) were nucleofected with N-terminally tagged eYFP PARKIN (a kind gift from the Josef Kittler lab) and grown on coverslips for 24-48 h. After treatment with DMSO or CCCP (10 µM) for 1 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with 0.1 M glycine in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), at pH 7.4, briefly permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked with a blocking solution containing 10% goat serum and 0.5% BSA. Samples were further incubated with anti-Tom20 antibody (FL-145, Santa Cruz) followed by goat Alexa647-coupled anti-rabbit antibody (Life Technologies). Confocal images were taken using a Zeiss LSM780 microscope.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

HeLa cells (originating from ATCC) were transfected with eYFP-PARKIN. After 24 h-48 h, cells were treated with DMSO or CCCP as before, and lysed in cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) NP-40) supplemented with EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), PhosphoSTOP (Roche), as well as 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 mM chloracetamide (Sigma-Aldrich) for better detection of ubiquitinated proteins. For immunoprecipitation of eYFP-PARKIN, 500 µg of cell lysate were incubated with GFP-Trap agarose (Chromotek) for 1 h. The beads were washed three times with cell lysis buffer, and proteins were eluted with 1xLDS buffer. Cells were regularly checked for absence of mycoplasma infection using the MycoAlert Kit (Lonza). Antibodies were from commercial sources: goat anti-GFP (ab6673, Abcam), rabbit anti-Tom20 (FL-145, Santa Cruz), mouse anti-GAPDH (6C5, Ambion).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were performed in a MicroCal iTC200 machine (GE Healthcare) at 20°C with the sample and the ligand in low salt buffer. The cell contained 35 μM of HsPARKINΔUbl and 400 μM HsPARKIN Ubl was injected in 2 μL injections at 120 s intervals. Protein sample as well as ligand were in low salt buffer and HsPARKINΔUbl was mixed with phosphoUb at a 1:1.2 molar ratio as indicated. Binding curves were integrated and fitted to a one-site binding model by using the MicroCal PEAQ-ITC Analysis plug-in for Origin (Malvern).

Phosphorylation assays

PARKIN phosphorylation was performed by incubating 5 μM HsPARKIN with 0.5 μM GST-TcPINK1, 10 mM ATP, 1x reaction buffer and phosphoUb (14 μM unless stated differently). The reaction was quenched at the given time points with LDS sample buffer and proteins were separated on a NuPAGE 4-12% gradient Bis-Tris gel, transferred on nitrocellulose membrane and detected with anti-pSer65 PARKIN antibody (Abcam cat no. ab154995). Phosphorylation assays of HsPARKIN Ubl domain (aa 1-72) and Ub were performed as described above with 20 μM of HsPARKIN Ubl domain and ubiquitin, respectively. For the Ub phosphorylation assay, the GST-TcPINK1 concentration was increased to 1.5 μM. The reaction was quenched at the given time points with LDS sample buffer and proteins were separated on a 15% SuperSep Phos-tag™ gel (Wako Chemicals) and stained with Instant Blue SafeStain (Expedeon).

Phosphorylation of the PARKIN Ubl domain for NMR analysis

Isotope-labelled HsPARKIN Ubl domain (aa 1-72) was expressed in M9 minimal media supplemented with 4 g/L 13C-glucose, 2 g/L 15N-NH4Cl, trace elements and BME Vitamins (Sigma-Aldrich) and purified as described above. The final gel filtration was performed in NMR buffer (18 mM Na2HPO4, 7 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM TCEP). Isotope-labelled HsPARKIN Ubl was phosphorylated at room temperature by incubating 80 µM HsPARKIN Ubl with 2.5 µM PhPINK1, 1 mM ATP and 1x ligation buffer which was adjusted to 332.5 µl with NMR buffer, before addition of 17.5 µl D2O as lock solvent. The reaction was monitored by consecutive 1H,15N 2D BEST-TROSY (Band Selective Excitation Short Transients Transverse Relaxation Optimised Spectroscopy) experiments and quenched with apyrase.

Solution studies of the phosphorylated PARKIN Ubl domain

NMR acquisition was performed at 298 K on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic triple resonance TCI probe. The software packages Topspin3.2 (Bruker) and Sparky (Goddard & Kneller, UCSF; http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky/) were used for data processing and analysis, respectively. 1H,15N 2D BEST-TROSY experiments 33 were conducted with in-house optimized Bruker pulse sequences that contained a recycling delay of 400ms and 512*64 complex points in the 1H,15N dimension, respectively.

Standard HSQC based Bruker triple resonance pulse sequences were used to generate backbone chemical shift assignments. CBCACONH and HNCACB spectra were collected with 50% Non Uniform Sampling (NUS) of 1024*32*55 complex points in the 1H, 15N and 13C dimensions. HNCO and HNCACO experiments were acquired using NUS at a rate of 50% with 1024*32*48 complex points in the 1H, 15N and 13C dimensions, respectively. Data set processing was performed with Compressed Sensing using the MddNMR software package 34. Weighted chemical shift perturbation calculations were completed using the equation √((Δ1H)2+(Δ15N/5)2).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Autoinhibited PARKIN and phosphoUb probes.

(a) Structure of rat PARKIN (RnPARKIN, pdb-id 4k95, 16, chain A is used for all representations of RnPARKIN) with Ubl domain coloured in green, the Unique PARKIN domain (UPD) in dark blue, RING1 in blue, IBR in lightblue, REP in red, and RING2 in cyan. Zinc atoms are shown as grey spheres. The catalytic Cys431 is shown in ball-and-stick representation. Disordered linkers are indicated as dotted lines. The three mechanisms of PARKIN inhibition are pointed out in red. (b) Schematic diagram of the closed, autoinhibited conformation of full-length PARKIN. (c) Superposition of the E2~Ub complex from the BIRC7 structure (pdb-id 4auq, 35), superposed via its RING domain onto RING1 of full-length RnPARKIN (pdb-id 4k95, 16) to indicate the position of the E2~Ub on PARKIN RING1. Assuming that E2~Ub adopts a canonical conformation on RING1, the E2 would clash with the Ubl domain and partially with the REP, while the E2-linked Ub would clash with the REP. Hence, Ubl and REP have to be released to enable PARKIN E2~Ub binding at RING1. (d) Time course analysis of an exemplary reaction of UbC3Br (0.2 mg/ml) phosphorylated by GST-PhPINK1 (5 µM) as described previously for ubiquitin8. Phosphorylation of proteins was monitored by a band shift on Coomassie-stained Phos-Tag gels. The experiment was performed two times with consistent result. (e) Data collection and refinement statistics.

Extended Data Figure 2. PhPARKIN similarity with human and rat PARKIN and map quality.

(a) Structure-based sequence alignment of PARKIN from human (top), rat (middle) and Pediculus humanus corporis (PhPARKIN, bottom). The domains are indicated in boxes coloured according to structural figures. HsPARKIN and PhPARKIN are 45% identical within their crystallised constructs. Secondary structure elements are shown for HsPARKIN Ubl domain (pdb-id 1iyf, 36) and for HsPARKIN core domain (4bm9, 14). Red stars denote the phospho-Ser65 Ub binding pocket, and yellow spheres the residues contacting phosphoUb (see Fig. 2). A black star denotes the catalytic Cys in RING2. (b) Stereo representation of the asymmetric unit of PhPARKIN~pUb crystals, showing 2|Fo|-|Fc| electron density at 1σ, in blue for PhPARKIN and in green for phosphoUb. (c) Electron density detail, shown as in b, zooming in on phosphoUb phospho-Ser65, in stereo representation (d) Superposition of the two PhPARKIN~pUb complexes in the asymmetric unit, coloured as in Fig. 1. The RMSD is 0.76 Å. Electron density is missing for parts of the flexible linker between IBR and RING2. (e) Superposition of available PARKIN structures (4bm9 14; 4i1h 15; 4k95 16 and two PhPARKIN~pUb complexes) in different colours, showing similar domain positions with respect to each other, with exception of the IBR domain. Only the structure of full-length RnPARKIN16 contains the Ubl domain.

Extended Data Figure 3. Conservation of phosphoUb interacting residues and biochemical analysis.

(a-b) An alignment of PARKIN from species available in Ensembl (www.ensembl.org) was curated by removing sequences with truncations or poorly sequenced regions. The residues involved in phosphoUb binding, comprising (a) the phosphate pocket and (b) the pUBH are shown, and residues contacting phosphoUb are highlighted. (c) Comparison of residues from PhPARKIN and HsPARKIN involved in phosphoUb binding. Highlighted in green are HsPARKIN β-hairpin residues Gly284 (Gly286 in PhPARKIN) which is mutated to Arg in AR-JP. Other β-hairpin mutations, L283P (Phe285 in PhPARKIN) and H279P (Ser281 in PhPARKIN), introduce Pro residues, likely distorting the β-hairpin loop. (bb), backbone interaction. (d) FP assays performed with mutant PARKIN and phosphoUb. Assays from two independent experiments were combined to produce Fig. 2e. Measurements were performed in triplicate with error bars given as standard deviation from the mean. (e) Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE gel showing HsPARKIN proteins used in activity assays. (f) Normalised proteins for PARKIN activity assays in Fig. 3d. (g) Analogous to Fig. 2a, phosphoUb bound to PhPARKIN is shown with Lys residues in stick representation, and free amine groups as blue spheres. Several Lys side chains (Lys29, Lys33, Lys48 and Lys63) were disordered in the electron density maps, suggesting high flexibility and solvent accessibility, and were modelled in their preferred side chain rotamer for illustrative purposes. When bound to PARKIN, each Lys residue can be ubiquitinated, and the C-terminus which is covalently attached to PhPARKIN in the complex structure, is likely more flexible and could also be attached to a more proximal (phospho)Ub in a chain. This indicates that PARKIN could interact with phosphoUb-containing polyUb chains that were reported to be the PINK1 substrate on mitochondria 7,8,11.

Extended Data Figure 4. PARKIN phosphoUb-binding mutants do not translocate to mitochondria.

(a-b) HeLa cells that do not contain detectable levels of PARKIN were transiently transfected with YFP-PARKIN wt and indicated mutants (green). Tom20 staining with anti-Tom20 antibody indicated mitochondria (red). Images are representative of three biological replicates. (a) In DMSO-treated control cells, PARKIN does not co-localize with mitochondrial Tom20. (b) After treatment with CCCP (10 µM) for 1h, wt PARKIN but not phosphoUb binding mutants co-localize with Tom20. Scale bars, 10 µm. Split channels are shown with overlay to illustrate co-localization. The YFP channel is identical to Fig. 2g. (c) Quantification of cells with PARKIN localized at mitochondria in b, scored for 150 cells per condition in three biological replicates. PhosphoUb binding mutants do not show sustained mitochondrial localization. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. (d) HeLa cells transiently transfected with HsPARKIN wt and mutants were treated with CCCP and YFP-PARKIN immunoprecipitated (see Methods). Whole cell lysates (WCL) or immunoprecipitates (IP) were western blotted for PARKIN, Tom20 and GAPDH (loading control) as indicated. Ubiquitinated forms of PARKIN and Tom20 can be observed with wt PARKIN but not with PARKIN mutants. Also see Fig. 2h where in addition the A320R mutant was included. These experiments were performed three times as biological replicates with similar results. Note that PARKIN autoubiquitination varied and was weaker in some experiments, while Tom20 ubiquitination was more robust. See Supplementary Information for uncropped blots.

Extended Data Figure 5. The kink in the pUBH.

(a-d) To understand whether the straight pUBH in PhPARKIN was a consequence of a helix-favouring mutation of Gly319 (HsPARKIN) to Ala (Ala321 in PhPARKIN), the HsPARKINΔUbl G319A mutant was crystallised and a structure determined at 2.35 Å resolution (see Extended Data Fig. 1e, Methods). (a) Superposition of HsPARKINΔUbl G319A and wt HsPARKINΔUbl (4bm9, 14). The structures are virtually identical, both containing a kinked helix. (b-c) Electron density detail of the kinked helix for the mutant (b) and wt (c), shown in stereo representation, with 2|Fo|-|Fc| density contoured at 1 σ. The Cβ atom of Ala319 is clearly defined in electron density and does not induce helix straightening in this crystallographic setting. (d) Comparison of pUBH helices in HsPARKINΔUbl G319A (left), HsPARKINΔUbl wt (2nd from left), superposition of the two (2nd from right), and for comparison the straight pUBH in PhPARKIN~pUb. (e-f) Structure of the RBR E3 ligase HHARI (e) in an autoinhibited form (pdb-id 4kbl, 23) showing an entirely different RBR module as compared to full-length RnPARKIN (4k95, 16) in f. RING1, IBR, RING2 domains are coloured as for PARKIN in Fig. 1, and other domains (UBA-like domain and Ariadne domain in HHARI) are coloured in red. Interestingly, the pUBH equivalent helix in HHARI is kinked at a similar position as compared to mammalian PARKIN. (g) Superposition of structures from e and f on their RING1 domains. In HHARI, the pUBH-equivalent helix kinks in a different manner as compared to HsPARKIN. (h) In HHARI, the kinked helix seems to be stabilised by an interaction in cis with the UBA-like domain that binds NEDD8 37. The sequence of the helix does not contain Gly residues, but is kinked at a Thr residue (Thr263). It will be interesting to see whether helix straightening occurs in active forms of HHARI that can be induced by binding NEDD8-modified Cullins 37.

Extended Data Figure 6. Structural detail and B-factor analysis.

(a) PhosphoUb-induced pUBH straightening is energetically neutral as the two hydrogen bonds between helix residues and the RING1 core are not lost but only adjusted. Left, full-length RnPARKIN structure (4k95, 16), right, PhPARKIN~pUb structure. (b) Structure of full-length RnPARKIN (4k95, 16, left), PhPARKIN~pUb (middle), and a superposition of the two (right), in which Cα atoms of structurally identical, ordered residues of the IBR-REP linker are shown as spheres. The distance between these residues is indicated by a dotted line. The linker sequence is highlighted in Extended Data Fig. 2. (c) Structures of PARKIN in which B-factors were refined for individual atoms (4bm9 14; 4i1h 15) are shown in a ribbon representation, in which the ribbon thickness indicates B-factors differences, with thin ribbons indicating low and thick ribbon indicating high B-factors. The full-length RnPARKIN structure (4k95, 16) is not included since in this 6.5 Å structure overall B-factors were assigned. (d) Structures of PhPARKIN~pUb shown as in c for each molecule of the asymmetric unit. The REP and RING2 elements are destabilised as indicated by higher B-factors. The rigid core of the protein has shifted from the UPD-RING1-RING2 interfaces (compare c) to the UPD-RING1-IBR-phosphoUb interfaces. B-factor analysis may be distorted by neighbouring molecules and crystal contacts, which are not indicated here.

Extended Data Figure 7. The Ile44 patch is essential for PINK1-mediated phosphorylation of Ub and PARKIN Ubl, and controls for Fig. 4c.

All assays were performed three times with consistent results. (a-b) Coomassie stained PhosTag gels comparing the phosphorylation of (a) the HsPARKIN Ubl domain (aa 1-72) and (b) ubiquitin. In both cases, the wt form is compared with the I44A mutant form of the protein. GST-TcPINK1 does not efficiently phosphorylate the I44A mutants of ubiquitin or of the HsPARKIN Ubl domain. This is important since the Ile44 patch in the PARKIN Ubl domain is inaccessible and binds to RING1 in the structure of full-length RnPARKIN (4k95, 16) (see Fig. 4a). (c) Coomassie-stained gel for Fig. 4c with proteins labelled and (d) full-size blot for Fig. 4c.

Extended Data Figure 8. NMR analysis of phospho-Ubl.

(a) BEST-TROSY spectra for isotope-labelled HsPARKIN Ubl domain (dark green) and phospho-Ubl domain (light green) with resonances assigned for the Ubl domain. (b) Chemical shift perturbation of Ubl with respect to phospho-Ubl, showing significant perturbations in the region of phosphorylation (Ser65), the last β-strand and neighbouring β-strands. Grey bars, exchange broadened resonances. (c) Mapping of perturbed resonances onto the previously determined NMR structure of HsPARKIN Ubl (1iyf, 36). The perturbed residues cluster in the Ser65-containing loop and in proximity to the Ile44 patch of the Ubl. (d) Mapping of the perturbed resonances to the structure of RnPARKIN (4k95, 16) shows that they perturb the interface between the Ubl domain and the PARKIN core. Thus, phosphorylated Ubl may not be able to (re)bind PARKIN at the same binding site.

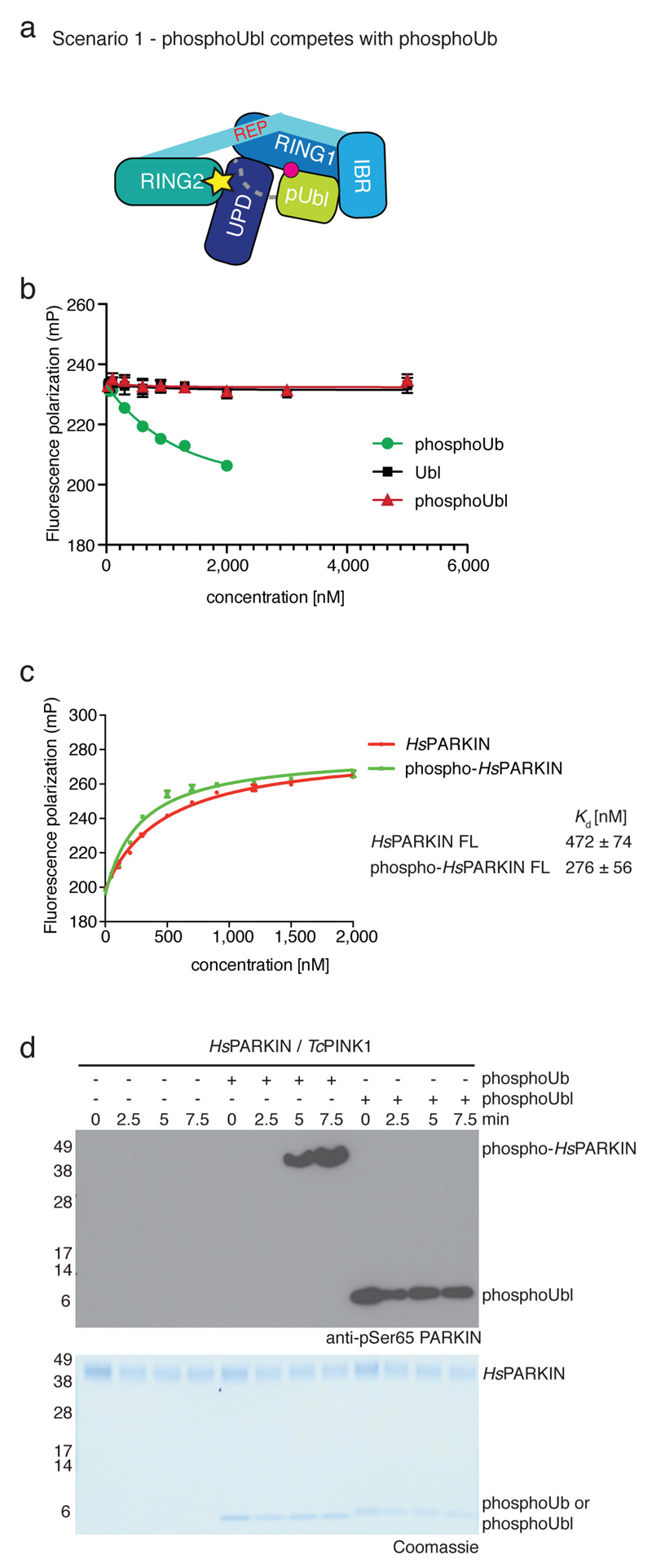

Extended Data Figure 9. PARKIN phosphoUbl does not compete with phosphoUb.

(a) A possible scenario is that the phosphoUbl competes with phosphoUb for the phosphoUb binding site on PARKIN. This could be favoured since the interaction would occur in cis. (b) Fluorescence polarisation competition experiment increasing the concentration of Ubl, phosphoUbl or phosphoUb with respect to full-length HsPARKIN in the presence of FlAsH-tagged phosphoUb. Measurements were performed in triplicate with error bars given as standard deviation from the mean. While unlabelled phosphoUb competes with labelled phosphoUb in the reaction, Ubl or phosphoUbl do not compete with phosphoUb. (c) Binding of FlAsH-phosphoUb to HsPARKIN and phospho-HsPARKIN. The measurements were performed in the same experiment as samples in Fig. 2d. If phosphoUbl interacts with HsPARKIN in cis, phosphoUb binding should be inhibited. In contrast, binding of phosphoUb to phospho-PARKIN is slightly enhanced as also reported in 7. Measurements were performed in triplicate and error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. (d) PARKIN phosphorylation assays as in Fig. 4c, including phosphoUbl as well as phosphoUb (both at 10 μM). While addition of phosphoUb induces PARKIN phosphorylation, addition of phosphoUbl does not, indicating that the Ubl is not released from the PARKIN core. The experiment has been performed three times with consistent result.

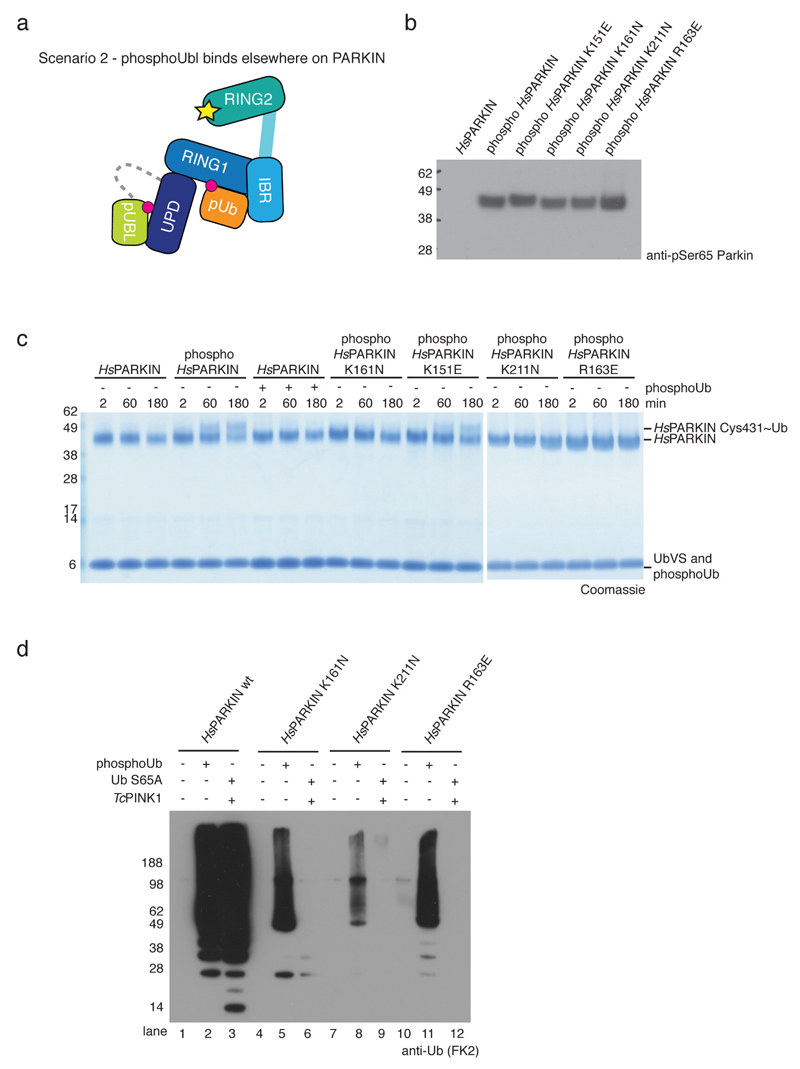

Extended Data Figure 10. PhosphoUbl-induced ‘opening’ of PARKIN relies on a phosphate pocket in the UPD.

(a) A second scenario would be that the phosphorylated Ubl rebinds to PARKIN at an alternative site. We previously speculated that the UPD contains a phosphate-binding site that is lined by two AR-JP patient mutations, K161N and K211N and also contains Arg163 14. (b) Full-length HsPARKIN mutants as indicated were phosphorylated in vitro with GST-PhPINK1, resolved on SDS-PAGE and Western blotted using an anti-pSer65 PARKIN antibody (Abcam cat no. ab154995). These proteins were used in c. (c) Ub-vinyl sulphone (Ub-VS) modification of the active site Cys431 of HsPARKIN and HsPARKIN mutants with and without phosphoUb from a time course experiment is assessed on Coomassie stained gels. Ub-VS reacts with ‘open’ forms of PARKIN, and was previously shown to modify phospho-PARKIN but not phosphoUb-activated PARKIN 7. Phospho-PARKIN mediated ‘opening’ depends on the phosphate pocket present in the UPD, since phospho-PARKIN K211N, K161N (two AR-JP patient mutations) and R163E abrogated or impaired modification by Ub-VS and do not appear to have an accessible catalytic Cys, while the phosphorylated phosphoUb-binding deficient mutant K151E is readily modified. The experiment was performed two times with consistent results and gels have been collated from two different assays (indicated by gap). (d) PARKIN ubiquitination reactions in presence of E1, UBE2L3, Ub or Ub S65A, ATP and GST-TcPINK1 for 2h. PARKIN is activated by phosphoUb or by PARKIN Ubl phosphorylation in absence of phosphoUb (with Ub S65A) (lanes 2/3). Mutants in the UPD phosphate pocket can still be activated by phosphoUb (albeit not to the same extent) (lanes 5, 8, 11) but are inactive when the Ubl is phosphorylated (lanes 6, 9, 12). This could suggest that the phosphoUbl binds back to the PARKIN UPD pocket. However we cannot exclude that e.g. the linker between the Ubl and the UPD plays a more active role in PARKIN activation. The experiment was performed three times with consistent results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Minmin Yu and beam-line staff at Diamond Light Source, beam line I-04 and I-04-1, S. Freund and J. Wagstaff for NMR data, C. Johnson and S. McLaughlin for help with biophysics, BostonBiochem for providing UbVs and UbVME, C. Gladkova for help with cloning, and N. Birsa and J. Kittler (UCL London) for providing YFP-PARKIN plasmids. We thank members of the DK lab for reagents and discussions and D. Barford, J. Pruneda and P. Elliott for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council [U105192732], the European Research Council [309756], the Lister Institute for Preventive Medicine, the EMBO Young Investigator Program (to DK), and an EMBO Long-term Fellowship (to MS).

Footnotes

Accession numbers

Coordinates and structure factors for the PhPARKIN~pUb complex and HsPARKINΔUbl G319A have been deposited with the protein data bank under accession codes 5caw and 5c9v, respectively.

Author contribution

TW and DK designed the research, and TW performed all experiments. MS performed cell-based studies. AS contributed to characterisation of Ubl and Ub phosphorylation. TW and DK analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with help from all authors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

DK is part of the DUB Alliance that includes Cancer Research Technology and FORMA Therapeutics, and is a consultant for FORMA Therapeutics.

References

- 1.Youle RJ, Narendra DP. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corti O, Lesage S, Brice A. What genetics tells us about the causes and mechanisms of Parkinson's disease. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1161–1218. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corti O, Brice A. Mitochondrial quality control turns out to be the principal suspect in parkin and PINK1-related autosomal recessive Parkinson's disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koyano F, et al. Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature. 2014;510:162–166. doi: 10.1038/nature13392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kane LA, et al. PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:143–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201402104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazlauskaite A, et al. Parkin is activated by PINK1-dependent phosphorylation of ubiquitin at Ser65. Biochem J. 2014;460:127–139. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ordureau A, et al. Quantitative Proteomics Reveal a Feedforward Mechanism for Mitochondrial PARKIN Translocation and Ubiquitin Chain Synthesis. Mol Cell. 2014;56:360–375. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wauer T, et al. Ubiquitin Ser65 phosphorylation affects ubiquitin structure, chain assembly and hydrolysis. EMBO J. 2015;34:307–325. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondapalli C, et al. PINK1 is activated by mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization and stimulates Parkin E3 ligase activity by phosphorylating Serine 65. Open Biology. 2012;2 doi: 10.1098/rsob.120080. 120080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiba-Fukushima K, et al. PINK1-mediated phosphorylation of the Parkin ubiquitin-like domain primes mitochondrial translocation of Parkin and regulates mitophagy. Sci Rep. 2012;2 doi: 10.1038/srep01002. 1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiba-Fukushima K, et al. Phosphorylation of Mitochondrial Polyubiquitin by PINK1 Promotes Parkin Mitochondrial Tethering. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okatsu K, et al. Phosphorylated ubiquitin chain is the genuine Parkin receptor. J Cell Biol. 2015;209:111–128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201410050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaugule VK, et al. Autoregulation of Parkin activity through its ubiquitin-like domain. EMBO J. 2011;30:2853–2867. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wauer T, Komander D. Structure of the human Parkin ligase domain in an autoinhibited state. EMBO J. 2013;32:2099–2112. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley BE, et al. Structure and function of Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase reveals aspects of RING and HECT ligases. Nature Communications. 2013;4:1982. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trempe J-F, et al. Structure of parkin reveals mechanisms for ubiquitin ligase activation. Science. 2013;340:1451–1455. doi: 10.1126/science.1237908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarraf SA, et al. Landscape of the PARKIN-dependent ubiquitylome in response to mitochondrial depolarization. Nature. 2013;496:372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borodovsky A, et al. Chemistry-based functional proteomics reveals novel members of the deubiquitinating enzyme family. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1149–1159. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang T, et al. Evidence for bidentate substrate binding as the basis for the K48 linkage specificity of otubain 1. J Mol Biol. 2009;386:1011–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macedo MG, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of Dutch patients with early onset Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:196–203. doi: 10.1002/mds.22287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veeriah S, et al. Somatic mutations of the Parkinson's disease-associated gene PARK2 in glioblastoma and other human malignancies. Nat Genet. 2010;42:77–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng X, Hunter T. Parkin mitochondrial translocation is achieved through a novel catalytic activity coupled mechanism. Cell Res. 2013;23:886–897. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duda DM, et al. Structure of HHARI, a RING-IBR-RING Ubiquitin Ligase: Autoinhibition of an Ariadne-Family E3 and Insights into Ligation Mechanism. Structure. 2013;21:1030–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caulfield TR, et al. Phosphorylation by PINK1 Releases the UBL Domain and Initializes the Conformational Opening of the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Parkin. PLoS Comp Biol. 2014;10:e1003935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ordureau A, et al. Defining roles of PARKIN and ubiquitin phosphorylation by PINK1 in mitochondrial quality control using a ubiquitin replacement strategy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112:6637–6642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506593112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazlauskaite A, Muqit MMK. PINK1 and Parkin – mitochondrial interplay between phosphorylation and ubiquitylation in Parkinson's disease. FEBS J. 2015;282:215–223. doi: 10.1111/febs.13127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickrell AM, Youle RJ. The Roles of PINK1, Parkin, and Mitochondrial Fidelity in Parkinson's Disease. Neuron. 2015;85:257–273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koyano F, Matsuda N. Molecular mechanisms underlying PINK1 and Parkin catalyzed ubiquitylation of substrates on damaged mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vijay-Kumar S, Bugg CE, Cook WJ. Structure of ubiquitin refined at 1.8 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1987;194:531–544. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90679-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams PD, et al. The Phenix software for automated determination of macromolecular structures. Methods. 2011;55:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Favier A, Brutscher B. Recovering lost magnetization: polarization enhancement in biomolecular NMR. J Biomol NMR. 2011;49:9–15. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kazimierczuk K, Orekhov VY. Accelerated NMR spectroscopy by using compressed sensing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:5556–5559. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dou H, Buetow L, Sibbet GJ, Cameron K, Huang DT. BIRC7-E2 ubiquitin conjugate structure reveals the mechanism of ubiquitin transfer by a RING dimer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:876–883. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakata E, et al. PARKIN binds the Rpn10 subunit of 26S proteasomes through its ubiquitin-like domain. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:301–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelsall IR, et al. TRIAD1 and HHARI bind to and are activated by distinct neddylated Cullin-RING ligase complexes. EMBO J. 2013;32:2848–2860. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.