Abstract

Aim

To investigate the bone-protective effects of salvianolate (Sal), a total polyphenol from Radix Salviae miltiorrhizae, on bone tissue in the spontaneous lupus-prone mouse model, B6.MRL-Faslpr/J, undergoing glucocorticoid (GC) treatment.

Methods

Fifteen-week-old female B6.MRL-Faslpr/J mice were administered either a daily dose of saline (lupus group), prednisone 6 mg/kg (GC group), Sal 60 mg/kg (Sal group); or GC plus Sal (GC + Sal group) for a duration of 12 weeks. Age-matched female C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice were used for control. Micro-computed tomography assessments, bone histomorphometry analysis, bone biomechanical test, immunohistochemistry and immunoblotting analysis for bone markers, and renal histology analysis were performed to support our research endeavor.

Results

Lupus mice developed a marked bone loss and deterioration of mechanical properties of bone due to an increase in bone resorption rather than suppression of bone formation. GC treatment strongly inhibited bone formation in lupus mice. Sal treatment significantly attenuated osteogenic inhibition, and also suppressed hyperactive bone resorption, which recovered the bone mass and mechanical properties of bone in both the untreated and GC-treated lupus mice.

Conclusion

The data support further preclinical investigation of Sal as a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus-related bone loss.

Keywords: SLE, osteoporosis, bone, MRL, skeleton

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a potentially fatal autoimmune disease characterized by multiorgan injuries and can include involvement of renal, cardiovascular, neural, musculoskeletal, and cutaneous tissues.1 Survival rate of SLE patients has increased, and increasing attention is being paid to the prevention of long-term complications such as bone loss and fracture. In a population-based cohort study, fracture occurrence in female SLE patients was nearly fivefold that of age-matched healthy subjects.2 Furthermore, increasing evidence indicates that, in the process of the pathogenesis of SLE, the disease itself would largely induce osteopenia and deterioration of bone quality, thereby increasing the risk of fracture.3 The inflammatory symptoms of SLE (eg, glomerular nephritis, arthritis, and neuropathy) can necessitate the long-term administration of glucocorticoids (GCs) and eventually cause serious side effects on the skeleton,4 including GC-induced osteoporosis and osteonecrosis, which put a subset of SLE patients at significantly high risk of fracture and disability. Concerns about this situation have prompted the development of new strategies aimed at preventing bone loss and deterioration of bone quality induced by GC and SLE for those SLE patients.

Salvianolate (Sal) is the total polyphenols extracted from Salvia miltiorrhiza. In People’s Republic of China, Sal preparation has been widely used in clinical practice for the treatment and prevention of cardiocerebral vascular diseases, and its safety profile is well established. Pharmacological research shows that S. miltiorrhiza not only has anticoagulant, vasodilatory, and anti-inflammatory, among other, therapeutic effects, but also increases blood flow and scavenges free radicals.5 Salvianolic acid B and tanshinol are well known to be among the most effective natural antioxidants.6 Our previous studies have demonstrated that tanshinol and salvianolic acid B (the major bioactive components of Sal) can protect against bone impairment induced by long-term excessive use of prednisone by stimulation of osteogenesis, inhibition of bone absorption, suppression of adipogenesis in bone marrow stromal cells (MSCs) and effectively improve the microcirculation of bone through the Wnt/FoxO pathway.7–9 Therefore, we hypothesize that Sal might have the potential to prevent bone deterioration in the SLE patients receiving GC treatment.

To test our hypothesis, we set out to investigate the bone-protective effect of Sal in the SLE murine model in combination with GC treatment. We used a spontaneous SLE transgenic mouse model (B6.MRL-Faslpr/J),10 which is characterized by a spontaneous mutation for lymphoproliferation (Faslpr), and displays systemic autoimmunity and massive lymphadenopathy associated with the proliferation of aberrant T cells, arthritis, and immune complex glomerulonephrosis. We performed micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) assessments, bone histomorphometry analysis, bone biomechanical testing, immunohistochemistry and immunoblotting analysis for bone markers, as well as renal histology analysis to support our research endeavor.

Materials and methods

Animals

Fifteen-week-old female B6.MRL-Faslpr/J mice (lupus mice, 20±2 g, background strain: C57BL/6J, donor strain: MRL/MpJ-Faslpr) were obtained from Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University, National Model Animal Research Center. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Guangdong Laboratory Animal Monitoring Institute and the National Laboratory Animal Monitoring Institute of China. The experiments have been conducted according to the protocols approved by Specific Pathogen Free animal care of the Animal Center of Guangdong Medical College, and approved by the Academic Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Guangdong Medical College, Zhanjiang, People’s Republic of China, Permit Number: SYXK (GUANGDONG) 2008-0007.

Experimental protocol

Thirty-two 15-week-old female B6.MRL-Faslpr/J mice were randomly allocated into five groups with eight mice per group and eight age-matched female C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice were used as blank control. The groups were: 1) WT group; 2) lupus group (saline, 0.1 mL, intraperitoneal injection); 3) prednisone acetate treatment (GC group, 6 mg/kg, oral gavage); 4) Sal treatment (Sal group, 60 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection; and 5) prednisone plus Sal treatment (GC + Sal group). All treatments were administrated daily for 12 weeks and the mice were weighed weekly. Mice were given subcutaneous injections of calcein (10 mg/kg; Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) on third, fourth, thirteenth and fourteenth day before they were sacrificed for the purpose of double labeling in vivo. At the endpoint, the mice were sacrificed by cardiac puncture under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia. Prednisone acetate was obtained from the Guangdong South China Pharmaceutical group Co., Ltd. (Guangdong, People’s Republic of China) Sal was obtained from Shanghai Green Valley Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China).

Micro-CT analysis

The left proximal tibia was processed for micro-CT analysis. The metaphyseal trabecular bone was scanned using viva CT40 (Scanco Medical, Zurich, Switzerland) in high-resolution condition (X-ray energy on 70 KVp, 114 μA, 8 W; integration time 200 ms). Briefly, the region of interest was the proximal tibial growth plate and the proximal tibial metaphysis located between 0 and 2 mm distal to the growth plate epiphyseal junction. Cortical bone was excluded outside the measurement range. Three-dimensional image reconstructions were generated using the following values for a Gauss filter (sigma 0.8) and a threshold of 180. Three-dimensional image analysis was performed to determine bone volume to tissue volume (BV/TV) ratio; bone surface to bone volume ratio; structure model index (SMI); connectedness density (Conn.D); bone mineral density of tissue volume; trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), number, and separation; and degree of anisotropy.

Bone mechanical properties test

The right femurs were used to determine bone mechanical properties through three-point bending test using a Bose Electro Force Testing System (ELF3510; Bose Corp., Eden Prairie, MN, USA). Bone samples were tested with a 1 mm indenter, at speed of 0.01 mm/s with 15 mm span (L). Force (F) and deflection (D) were automatically recorded. The output parameters include yield load (N), ultimate load (N), and stiffness (N/mm).

Serum bone biomarker measurements

Blood was collected by intracardiac puncture during necropsy. Serum was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRACP) 5b was measured using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (IDS, Fountain Hills, AZ, USA) by following the manufacturer’s instruction. Serum osteoprotegerin (OPG) was measured using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) by following the manufacturer’s instruction.

Bone histomorphometry

The right proximal tibia metaphysis was processed for undecalcified section and bone histomorphometric analyses as previous described.11 Frontal sections of 5 and 9 μm were obtained from each sample. The 5 μm sections were stained by toluidine blue for static histomorphometric analyses. The 9 μm unstained sections were used for dynamic histomorphometric analyses. A semiautomatic digitizing image analysis system (Osteometrics, Inc., Decatur, GA, USA) was used for quantitative bone histomorphometric measurements. Briefly, the region of interest was located between 1 and 3 mm distal to the growth plate–epiphyseal junction. The quantitative analysis was performed on one section of each sample. The abbreviations of the bone histomorphometric parameters used were recommended by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research Histomorphometric Nomenclature Committee.12 Static parameters included total tissue volume (TV), trabecular bone volume (BV), bone surface (BS), osteoclast surface (Oc.S) and osteoblast surface (Ob.S). Dynamic parameters include trabecular single-labeled surface, double-labeled surface, inter-label width and inter-label width in the growth plate. Inter-label width in the growth plate, interlabel width, single-labeled surface and double-labeled surface were measured on unstained sections under ultraviolet light and were used to calculate the mineral apposition rate (MAR), longitudinal bone growth rate (LBGR), the ratio of mineralizing surface to bone surface (MS/BS) and bone formation rate per unit of bone surface (BFR/BS). The osteoclast surface per unit of bone surface (Oc.S/BS) and osteoblast surface per unit of bone surface (Ob.S/BS) were measured on toluidine blue sections. All histomorphometric parameters and procedures were in accordance with previously published studies.7,13

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunostaining for interleukin 6 (IL-6) was performed on 4 μm decalcified distal femoral sections. The procedures were performed as described previously7 with an immunohistochemical kit (Boster, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China) by following the manufacturer’s instruction. The anti-IL-6 antibody was purchased from Abcam. The region of interest was the distal femur growth plate and the distal femur metaphysis located between 0 and 2 mm distal to the growth plate epiphyseal junction. The images in the region of interest of each sample were captured at 20× magnification. Six different images were randomly collected per sample and subjected to final analysis. The analysis was performed by the biomedical image analysis software (Image Pro plus 6.0, IPP 6.0; Media Cybernetics Inc., Silver Spring, MD, USA). The evaluation of IL-6 expression was determined by integral optical density values of the images. The integral optical density values of positive staining in the distal femur are presented as mean ± standard deviation. All image groupings analyzed using IPP 6.0 were blinded to the analysts.

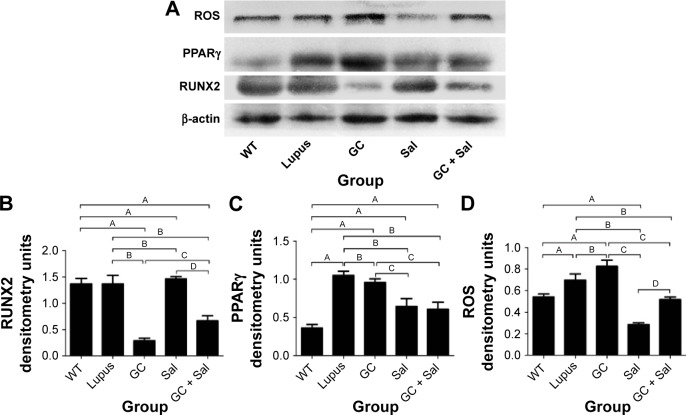

Immunoblotting analysis of ROS, PPARγ, RUNX2, IL-6, and RANKL in lumbar vertebrae

Lumbar vertebrae were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground into a powder. Tissue homogenates were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed by an immunoblot assay (Beyotime, Haimen, People’s Republic of China). Protein expression of RUNX2 (runt-related transcription factor 2), RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand), ROS (reactive oxygen species), IL-6, and PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma) were detected using the anti-RUNX2 antibody (Abcam), anti-sRANKL antibody (Abcam), anti-IL-6 antibody (Abcam); anti-ROS antibody (Bioss, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China) and anti-PPARγ antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), respectively. Anti-β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) was used as a loading control. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were used as secondary antibodies. Band detection was conducted using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system and quantified by ImageJ software. Band intensities were expressed as a ratio after normalization to β-actin.

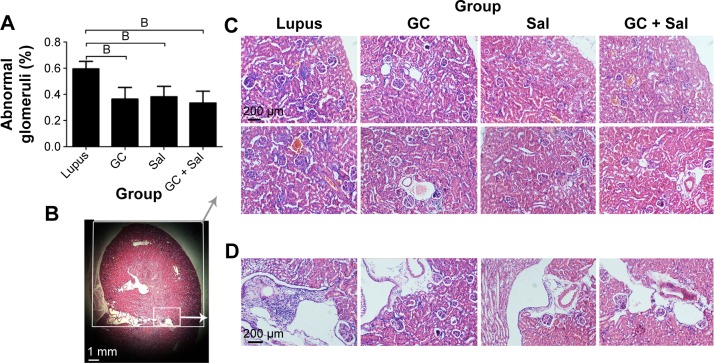

Kidney preparation and histology

Kidneys of mice were hemi-sectioned and portions were embedded in paraffin. Slices of 4 μm thickness were prepared on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histology analysis. The region of interest was half of the renal section. Seventy glomeruli in renal cortex per mouse were evaluated, and then the ratio of abnormal glomeruli was calculated. Glomerulonephritis was assessed using a semiquantitative 0–4 scale, in which 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 indicate that 0%, 1%–19%, 20%–50%, 51%–75%, and 75% of the glomeruli were affected, respectively. A score of 1 represents mild focal disease. A score of 2 represents moderate focal disease. Scores of 3 and 4 correspond to diffuse disease and as such were classified as “severe glomerulonephritis”.14 The analyst was blinded to all the treatments and groupings.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The statistical differences among groups were evaluated using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) by analysis of variance with Fisher’s protected least significant difference or Tamhane’s T2 test. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Lupus mice developed a marked bone loss

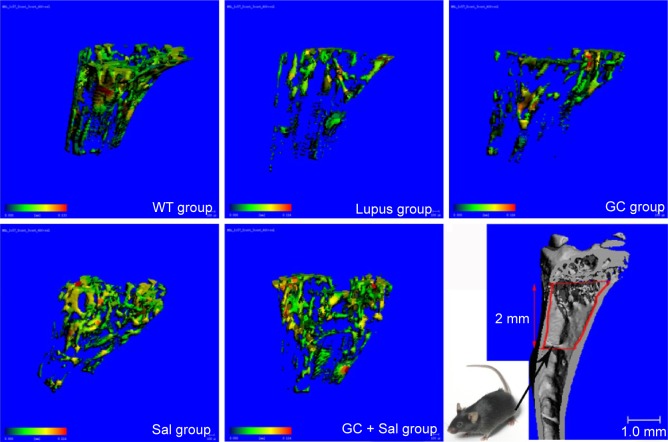

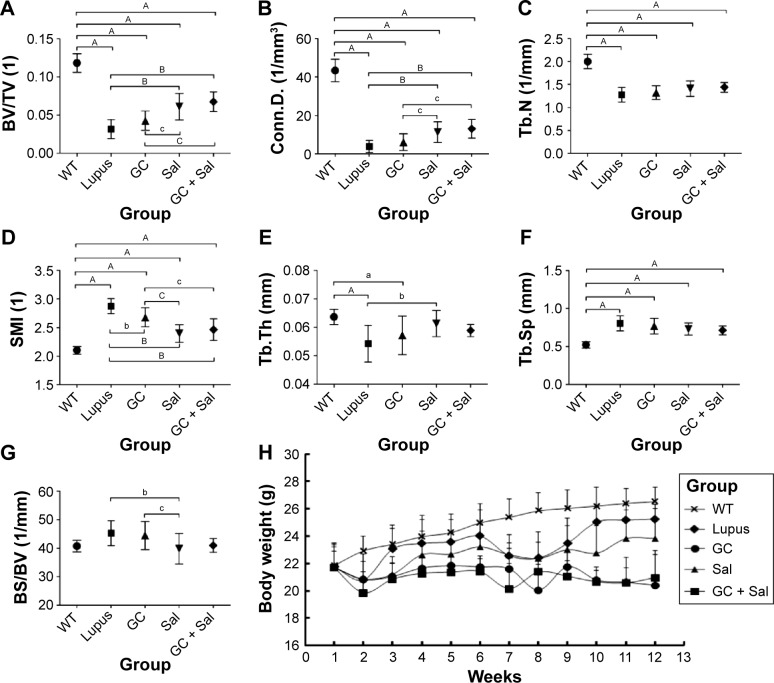

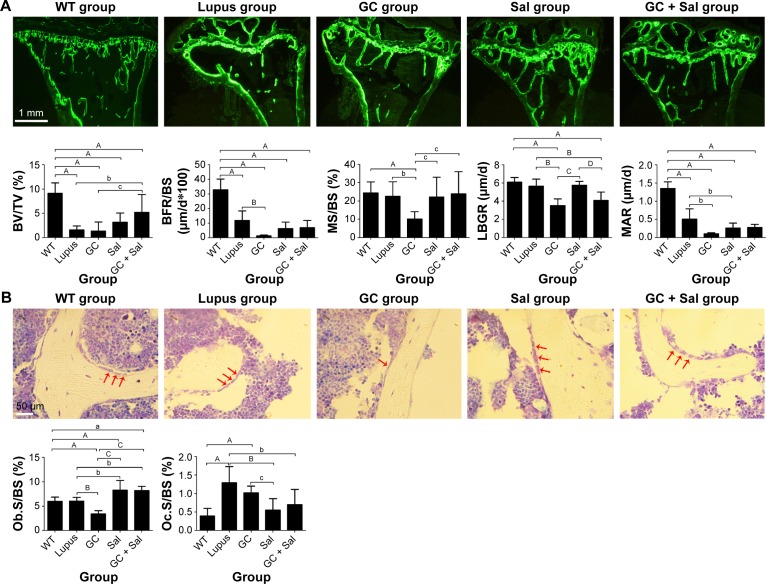

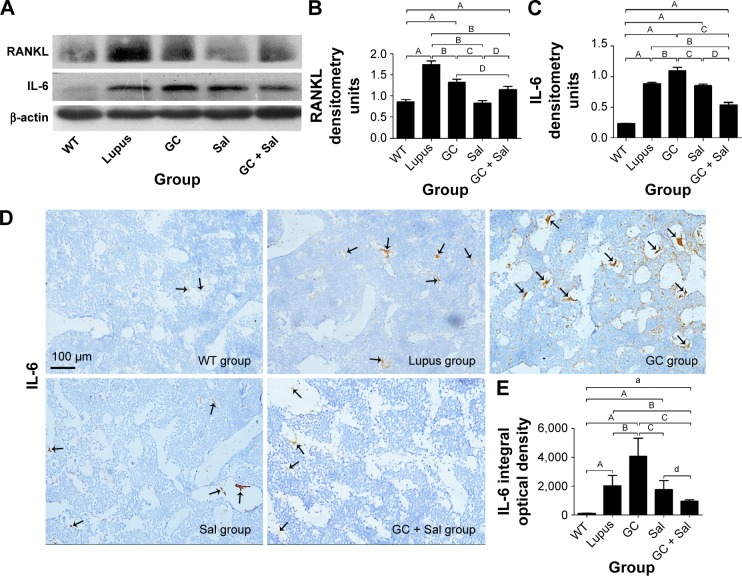

The area selected for micro-CT analysis in the animal model was located in proximal tibial metaphysis between 0 and 2 mm distal to the growth plate–epiphyseal junction (Figure 1). The results of the micro-CT indicated that trabecular BV/TV ratio decreased by 73.2% and was accompanied by significant deterioration in other related bone geometry and microstructure parameters (Conn.D, trabecular number, Tb.Th, trabecular separation, and SMI) (Figure 2). In histomorphometry analysis, the trabecular BV/TV ratio was only 1.6% in lupus mice, which was significantly lower than in the age-matched WT (9.1%) (Figure 3A). There were also significant differences in serum TRACP 5b and OPG levels between untreated lupus mice and WT. Bone mechanical data demonstrated significantly higher values for ultimate load, yield load, and stiffness in untreated lupus mice compared with WT (Table 1). Additionally significantly elevated osteoclast surface Oc.S/BS (Figure 3B), RANKL, IL-6 (Figure 4), PPARγ, and ROS (Figure 5) were observed in the untreated lupus mice. However, bone formation parameters “Ob.S/BS, MS/BS, LBGR (Figure 3), and RUNX2 expression (Figure 5)” did not change significantly in untreated lupus mice compared to WT.

Figure 1.

Representative micro-CT photographs of PTM in lupus mice undergoing different treatments.

Notes: The micro-CT photos were selected according to the mean BV/TV in different groups. Color images represent the thickness distribution of bone inside or outside the tibial metaphysis. Color changes from green to red indicate a gradual increase in bone thickness. The analysis area was located between 0 and 2 mm distal to the growth plate–epiphyseal junction. WT group, wild type mice; lupus group, lupus mice (B6.MRL-Faslpr/J); GC group, lupus mice with prednisone treatment; Sal group, lupus mice with salvianolate treatment; GC + Sal group, lupus mice with prednisone plus salvianolate treatment.

Abbreviations: BV, bone volume; GC, glucocorticoid; micro-CT, micro-computed tomography; PTM, proximal tibial metaphysis; Sal, salvianolate; TV, tissue volume.

Figure 2.

Micro-CT analysis of proximal tibial metaphysis (PTM) and monitored body weight data of lupus mice undergoing different treatments.

Notes: (A) BV/TV, (B) Conn.D, (C) Tb.N, (D) SMI, (E) Tb.Th, (F) Tb.Sp, (G) BS/BV, (H) Body weight data for lupus mice within different treatment groups. WT group, wild type mice; lupus group, lupus mice (B6.MRL-Faslpr/J); GC group, lupus mice with prednisone treatment; Sal group, lupus mice with salvianolate treatment; GC + Sal group, lupus mice with prednisone plus salvianolate treatment. Values are presented as mean ± SD, aP<0.05 vs WT; AP<0.01 vs WT; bP<0.05 vs lupus; BP<0.01 vs lupus; cP<0.05 vs GC; CP<0.01 vs GC.

Abbreviations: BS/BV, bone surface to bone volume; BV/TV, bone volume to tissue volume; Conn.D, connectivity density; GC, glucocorticoid; micro-CT, micro-computed tomography; Sal, salvianolate; SD, standard deviation; SMI, structure model index; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness.

Figure 3.

Representative bone fluorescence micrographs of PTM (calcein fluorescence, magnification: 40×), osteoblast morphology (undecalcified sectioning with toluidine blue staining, magnification: 40×), and bone histomorphometry analysis in lupus mice undergoing different treatments.

Notes: The regions of interest for analyses were located between 1 and 3 mm distal to the growth plate–epiphyseal junction. (A) Representative bone fluorescence micrographs and histomorphometry analysis. (B) Representative toluidine blue staining images of PTM and histomorphometry analysis of osteoblast and osteoclast. WT group, wild-type mice; lupus group, lupus mice (B6.MRL-Faslpr/J); GC group, lupus mice with prednisone treatment; Sal group, lupus mice with salvianolate treatment; GC + Sal group, lupus mice with prednisone plus salvianolate treatment. Values are presented as mean ± SD. aP<0.05 vs WT; AP<0.01 vs WT; bP<0.05 vs lupus; BP<0.01 vs lupus; cP<0.05 vs GC; CP<0.01 vs GC; DP<0.01 vs Sal. Red arrows point to osteoblasts.

Abbreviations: BFR/BS, bone formation rate to bone surface; BV/TV, bone volume to tissue volume; GC, glucocorticoid; LBGR, longitudinal bone growth rate; MAR, mineral apposition rate; MS/BS, the ratio of mineralizing surface to bone surface; Ob.S/BS, osteoblast surface per unit of bone surface; Oc.S/BS, osteoclast surface per unit of bone surface; PTM, proximal tibial metaphysis; Sal, salvianolate; SD, standard deviation.

Table 1.

Bone biomechanical properties and serum biochemical analyses of lupus mice undergoing different treatments

| Group | WT group | Lupus group | GC group | Sal group | GC + Sal group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ULT (N) | 20.68±2.25 | 14.32±1.96A | 14.31±0.93A | 16.87±2.03A,b,c | 15.74±2.03A |

| YLD (N) | 17.32±1.80 | 8.77±1.72A | 8.49±0.58A | 11.93+0.96A,b,c | 10.61±2.32A |

| STIFF (N/mm) | 138.29±14.6 | 50.5±5.33A | 44.48±8.47A | 68.82±10.01A,b,c | 61.01±2.28A,b,c |

| TRACP 5b (U/L) | 0.72±0.04 | 1.01±0.04A | 1.05±0.06A | 0.92±0.03A,B,C | 0.96±0.02A,b,C |

| OPG (pg/mL) | 209.31±27.04 | 77.85±12.77A | 106.88±33.4A | 208.8±34.8B,C | 175.8±29.5B,C |

Notes:

P<0.01 vs WT;

P<0.05 vs lupus;

P<0.01 vs lupus;

P<0.05 vs GC;

P<0.01 vs GC. Values are presented as mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: GC, glucocorticoid; Sal, salvianolate; SD, standard deviation; STIFF, stiffness; TRACP 5b, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b; ULT, ultimate load; WT, wild-type; YLD, yield load; OPG, osteoprotegerin.

Figure 4.

Immunoblotting analysis of RANKL and IL-6 expression in lumbar vertebrae and immunohistochemistry staining for IL-6 expression in the distal femur.

Notes: (A) Representative immunoblotting images of RANKL and IL-6. (B) RANKL expression. (C) IL-6 expression. (D) Immunohistochemistry staining for IL-6 expression, arrows indicate positive expression of IL-6. (scale 100 μm, magnification: 20×) (E) IL-6 expression in the distal femur. WT group, wild type mice; lupus group, lupus mice (B6.MRL-Faslpr/J); GC group, lupus mice with prednisone treatment; Sal group, lupus mice with salvianolate treatment; GC + Sal group, lupus mice with prednisone plus salvianolate treatment. Values are presented as mean ± SD. aP<0.05 vs WT; AP<0.01 vs WT; BP<0.01 vs lupus; GC; CP<0.01 vs GC; dP<0.05 vs Sal; DP<0.01 vs Sal.

Abbreviations: GC, glucocorticoid; IL, interleukin; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand; Sal, salvianolate; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Immunoblotting analysis of ROS, PPARγ, and RUNX2 in the lumbar vertebrae of lupus mice undergoing different treatments.

Notes: (A) Representative immunoblotting analysis images of ROS, PPARγ, and RUNX2; (B) RUNX2; (C) PPARγ; (D) ROS; WT group, wild type mice; lupus group, lupus mice (B6.MRL-Faslpr/J); GC group, lupus mice with prednisone treatment; Sal group, lupus mice with salvianolate treatment; GC + Sal group, lupus mice with prednisone plus salvianolate treatment. Values are presented as mean ± SD. AP<0.01 vs WT; BP<0.01 vs lupus; CP<0.01 vs GC; DP<0.01 vs Sal.

Abbreviations: GC, glucocorticoid; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RUNX2, runt-related transcription factor 2; Sal; salvianolate; SD, standard deviation.

GC treatment inhibited bone formation in lupus mice

GC treatment strongly inhibited the bone formation parameters and markers BFR/BS, MAR, LBGR, MS/BS, Ob.S/BS (Figure 3), and RUNX2 (Figure 5) compared to untreated lupus mice. GC treatment significantly elevated IL-6 (Figure 4), ROS, and PPARγ expression (Figure 5) levels compared to untreated lupus mice.

Sal treatment attenuated bone loss and improved mechanical properties of bone in lupus mice

Sal treatment significantly increased trabecular BV/TV (92.6%), Conn.D, and Tb.Th, and decreased SMI and bone surface to bone volume according to micro-CT analysis (Figure 2). Histomorphometry analysis revealed that it also increased trabecular area ratio up to 3.14% (Figure 3) when compared to untreated lupus mice (1.6%). Serum TRACP 5b and OPG levels in Sal-treated lupus mice were significantly different than those of lupus untreated mice and GC-treated lupus mice. Bone mechanical data demonstrated significantly higher values for ultimate load, yield load, and stiffness in Sal-treated lupus mice compared with both lupus mice and GC-treated lupus mice (Table 1). When compared to untreated lupus mice, Sal treatment significantly increased expression of RUNX2 (Figure 5) and Ob.S/BS (Figure 3B), but significantly decreased the Oc.S/BS (Figure 3B), RANKL (Figure 4), ROS, and PPARγ expression (Figure 5).

Sal supplemental treatment increased bone mass, restored bone formation, and suppressed bone resorption in GC-treated lupus mice

As observed in micro-CT analysis, GC + Sal treatment significantly increased trabecular BV/TV and Conn.D, and decreased SMI when compared to lupus mice treated only with GC (Figure 2). Additionally, GC + Sal treatment increased trabecular BV/TV ratio by 224.7% in histomorphometry analysis (Figure 3) compared to GC-treated lupus mice. Serum TRACP 5b and OPG levels in GC + Sal-treated lupus mice showed significant differences when compared with untreated lupus mice and GC-treated lupus mice. Bone mechanical data demonstrated higher ultimate load, yield load, and significantly higher stiffness value in GC + Sal-treated lupus mice compared with GC-treated or untreated lupus mice (Table 1). GC + Sal treatment increased BFR/BS, MS/BS, and MAR and significantly increased MS/BS, Ob.S/BS (Figure 3), and RUNX2 expression (Figure 5), but significantly decreased Oc.S/BS (Figure 3B), RANKL, IL-6 (Figure 4), ROS, and PPARγ (Figure 5) when compared to GC-treated lupus mice.

Renal histology analysis

Both the glomeruli basement membrane and the mesangial membrane of lupus mice showed active proliferation and inflammation. The abnormal glomeruli at 59.5% (score of 3) and massive inflammatory cell invasion that occurred in lupus mice indicated severe glomerulonephritis. GC, Sal, and GC + Sal treatments, all significantly inhibited glomerulus pathological changes decreasing abnormal glomeruli to 36.3%, 38.2%, and 33.4%, (score of 2), respectively, and also inhibited invasion of inflammatory cells (Figure 6). The body weights of lupus untreated mice were higher than other treatment mice (Figure 2), which suggests that the mice might gain weight because of edema caused by renal inflammation.

Figure 6.

Renal pathological changes in lupus mice undergoing different treatments (magnification: 10×, H&E stained).

Notes: (A) Quantification of the abnormal glomeruli ratio in each treatment group. (B) The region of interest of the renal cortex, in half of the renal section. (1×) Gray box/arrow shows the renal pathological analysis located in the region of renal cortex, in half of the renal section (C). White box/arrow shows the renal interstitial space (D). (C) Glomeruli in the renal cortex in half of the renal section. (D) Inflammatory cell invasion in the renal interstitial space. WT, wild-type mice; lupus, lupus mice (B6.MRL-Faslpr/J); GC group, lupus mice with prednisone treatment; Sal group, lupus mice with salvianolate treatment; GC + Sal group, lupus mice with prednisone plus salvianolate treatment. Values are presented as mean ± SD. BP<0.01 vs lupus.

Abbreviations: GC, glucocorticoid; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; Sal, salvianolate; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

Our data indicated that SLE disease itself induced bone loss and deteriorated the trabecular architecture, and that significant bone loss in lupus mice had resulted in tremendously deteriorated bone mechanical properties. We found that lupus significantly increased bone resorption parameters (TRACP 5b, osteoclast surface Oc.S/BS, RANKL, IL-6, PPARγ, and ROS), yet only moderately decreased bone formation parameters (Ob.S/BS, MS/BS, LBGR, and RUNX2), which demonstrated that bone metabolism in lupus mice is in a phase of high bone turnover. Our current data suggest the potential hypothesis that SLE disease is intrinsically responsible for the bone loss evident in the lupus mice, and occurs in a manner that strengthens bone resorption rather than suppresses bone formation. Increasing evidence demonstrates that SLE would induce osteopenia, and low bone mineral density was found even in SLE patients without any prior GC exposure,15 followed by high prevalence of fragility fractures.3 A marked loss of cortical area as well as trabecular volume were exhibited in the femur of mice without any GC treatment.16 Moreover, the true prevalence of fractures in patients with SLE might be higher than what was observed in clinical practice.17 Tang et al18 demonstrated that SLE/non-GC patients had significantly lower areal bone mineral density (BMD) at the femoral neck and total hip, and diminished radial total volumetric BMD, cortical area, and thickness, as well as significantly compromised bone strength. Inflammation-mediated bone loss was associated with an increased frequency of osteoclast precursors in the bone marrow, and a higher number of osteoclasts in the epiphyseal regions of the distal femurs and proximal tibiae.19 Not surprisingly, patients with SLE are at risk for the development of systemic osteoporosis and associated osteoporotic fractures.

For decades, natural and synthetic GCs have been the cornerstone of SLE treatment. To date, SLE patients are still one of the largest populations undergoing GC administration. However, GC treatment was considered to negatively affect bone metabolism and increase the possibility of fractures.20 GCs directly inhibit both osteoblast differentiation and function, while simultaneously inducing osteoblast apoptosis, and increasing osteoclast proliferation and activity.21 In addition to their direct effects on bone cells, GCs also exert effects on other organs, such as intestine (decrease calcium absorption), kidneys (increase renal calcium clearance), gonads (affect the synthesis and secretion of sex hormones), and most likely the parathyroid glands as well (increase parathyroid hormone [PTH] and PTH sensitivity).22 These effects indirectly lead to osteoporosis. Our current data demonstrated significant inhibition of osteogenesis accompanied by strong bone resorption in GC-treated lupus mice. In addition to direct effects on osteoblasts, GC also increased PPARγ in GC-treated lupus mice, suggesting that GC treatment stimulated differentiation of MSCs to adipocytes, thereby reducing the pool of local progenitor cells available to differentiate into osteoblasts. These findings were consistent with our previous publications.7,23 The high expression of ROS in GC-treated lupus mice suggests that one of the potential mechanisms of bone formation inhibition could be attributed to oxidative stress, which would elicit a series of deleterious events in osteoblasts and ultimately contributes to osteoporosis.24 We also noticed that our IL-6 data was not consistent with data observed in SLE patients treated with GCs,25 in which IL-6 analysis was performed in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients, whereas we performed IL-6 analysis in the bones of mice. Different experimental subjects and different GC administration regimens may explain these different results. IL-6 is an inflammatory cytokine that was expected to be inhibited by GC treatment, but is also a biomarker of bone resorption. TRACP 5b is a biomarker of bone resorption and osteoclastogenesis,26 which is specifically secreted by osteoclasts and is indicative of strong bone resorption. The elevated bone resorption in GC-treated lupus mice in this study might be caused directly or indirectly by the elevated levels of IL-6.

The most common treatment for osteoporosis nowadays is still oral bisphosphonates,27 which function primarily by inhibiting bone resorption, thereby preventing bone loss and further reducing the fracture risk. However, with these antiresorptive agents, bone remodeling remains coupled, therefore, a decrease in bone formation was still observed.28 While SLE patients receive GC treatment, antiresorptive agents may not be a good choice for the prevention of osteopenia, as GC treatment would induce inhibition of bone formation, thereby leading to the potential worsening of osteogenesis. Therefore, a superior option would be anabolic agents, which act primarily by stimulating osteoblast activity, and lead to new bone growth. Currently, the only approved anabolic agent for the treatment of osteoporosis in the US is teriparatide (parathyroid hormone 1–34). Teriparatide has been shown to significantly improve BMD and reduce vertebral and nonvertebral fracture risk, which makes it a potential alternative therapy for osteoporosis patients at high risk for fracture or with severe osteoporosis.29 Nevertheless, teriparatide application is currently limited, partially, due to its high economic cost and potential to cause osteocarcinoma. Thus, there is an urgent need for a safer alternative anabolic agent or strategy with a lower economic cost.

In this study, Sal treatment increased the bone-formation parameters RUNX2, OPG, and Ob.S/BS and decreased the bone-resorption parameters TRACP5b, RANKL, IL-6 expression, and Oc.S/BS. This demonstrated the uncoupling effects of osteoblast and osteoclast activity for rescuing bone mass in GC-treated lupus mice/lupus mice. Furthermore, Sal treatment demonstrated greater significance in the improvement of bone mechanical properties in lupus mice, rather than GC-treated lupus mice. The uncoupled osteoblast/osteoclast modeling is contrary to what was found in PTH/bisphosphonates treatment studies.

S. miltiorrhiza and its bioactive components have been used for the treatment of cardiovascular disease for years in People’s Republic of China, as their therapeutic effect and safety profile are well established. In 2009, our team first reported that the aqueous extract of S. miltiorrhiza provided effective bone protection in GC-induced osteoporosis,30 and we subsequently began further investigation into its potential mechanism.7,9 First, salvianolic acid B, one of the main components in Sal, could stimulate osteogenesis by upregulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. It is known that canonical Wnt/β-catenin is a key pathway in the regulation of bone formation and remodeling, and contributes to osteoblastic differentiation,31 in which DKK-1 is one of the inhibitors of Wnt signaling. Studies have demonstrated GC treatment to be a very strong inducer of DKK-1 protein, leading to a decrease in osteoblasts.32 Salvianolic acid B could facilitate a decrease in DKK-1 expression and stimulate osteoblast cell growth and MSC differentiation into osteoblast maturation, defined by secretion of ALP and osteocalcin in a dose- and time-dependent manner that mimics the action of an osteoblast inducer. Moreover, in GC-treated mice, salvianolic acid B stimulated femoral bone BMP-2 and BMP-7 messenger RNA expression and protected against a decrease in femur bone BMP-2 and BMP-7 protein expression. Previous studies have shown that BMPs comprise a subfamily within the transforming growth factor-β superfamily and exert an important role in skeletal development and adult bone homeostasis.33 In this study, RUNX2, OPG, and Ob.S/BS were significantly increased by Sal, which provided evidence that Sal stimulated osteogenesis and thus ameliorated the suppression of bone formation caused by GC treatment. RUNX2 was found to integrate Wnt signaling for mediating osteogenic differentiation of MSCs,34 and is also known to be involved in BMP signaling.35 Second, our current data demonstrated bone resorption parameters (TRACP 5b, RANKL, IL-6, and Oc.S/BS) were suppressed by Sal, suggesting that Sal inhibited the elevated bone resorption in GC-treated lupus mice. RANKL plays the critical role in bone physiology of stimulating osteoclastic differentiation/activation and inhibiting osteoclast apoptosis.36 RANKL in association with macrophage-colony-stimulating factor is necessary and sufficient for the complete differentiation of osteoclastic precursors into mature osteoclasts. The RANKL and IL-6 produced by stromal/osteoblast cells are closely related in osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption situations.37 IL-6 is also involved in RANKL and tumor necrosis factor-α signaling pathways, which stimulate osteoclast differentiation and growth, as well as increase the activity of osteoclasts.38 The RANKL and OPG data in this study lend support to the hypothesis that Sal treatment attenuates bone loss in lupus/GC-treated lupus mice partially through the RANK/RANKL/OPG system. Third, our current data demonstrated that both ROS and PPARγ expression were suppressed by Sal treatment, and the ROS data suggested that oxidative stress was decreased and that this contributed to increased osteoblast viability and activity. Furthermore, our previous publication reported that tanshinol, one of the main components in Sal, attenuates oxidative stress via downregulation of FoxO-3a signaling, and rescues the decrease of osteoblastic differentiation through upregulation of Wnt signaling under oxidative stress.9 Oxidative stress induced a progressive increase in the prevalence of osteoblast apoptosis, and caused the increase of osteoclast activity and upregulation of osteoclast differentiation.39 A further publication indicated that Sal inhibits ROS production through the transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway.40 Because osteoblasts and adipocytes share common bone stromal progenitors, the decrease in PPARγ suggested that adipogenesis in the bone marrow was suppressed, which indicated that the pool of marrow progenitors were available to differentiate into osteoblasts and not be preferentially stimulated to form adipocytes by GC treatment, therefore eventually contributing to an increase in osteoblasts and osteogenesis.41 Previous research also indicated that salvianolic acid B treatment increases marrow angiogenesis, which in turn increases blood flow to improve nutrition and serves as a source of circulating progenitors,7 as well as increases osteocyte lacunar canaliculi and blood vessel fluid volume, which would both increase bone strength and reduce the risk of fracture.42

In this study, serious inflammatory cell invasion and glomerular lesions were observed in lupus mice (Figure 6), and Sal treatment demonstrated an anti-inflammatory effect in the kidneys. Both Sal treatment and GC + Sal treatment significantly decreased the ratio of impaired glomeruli and inhibited inflammatory cell invasion compared to untreated lupus mice. These results suggested that Sal treatment could provide supplementary beneficial effects to antiglomerulonephritis without affecting the anti-inflammatory effects of GC treatment, which will improve GC safety without compromising its efficacy. Some previous publications have suggested that Sal can inhibit the proliferation of mesangial cells and the release of endothelin in vitro,43 and that Sal in combination with alprostadil effectively slows down the deterioration of chronic kidney disease in vivo.44

Overall, the multiple benefits that supplemental Sal treatment provided to GC-treated lupus mice include: 1) suppression of activated bone resorption; 2) attenuation of the osteogenesis inhibition caused by GC treatment; which, together with suppression of resorption leads to attenuated bone loss caused by the disease itself as well as GC, and rebalancing of abnormal bone metabolism; 3) providing an anti-inflammatory effect in the kidneys and attenuating renal insufficiency. Although the effects of Sal are not as potent as PTH in bone, its safety and lower economic cost may provide multiple benefits. We envision that supplemental treatment with Sal can be effectively developed as a strategy in treatment of SLE-related bone loss.

Conclusion

Lupus mice developed a marked bone loss and deterioration of bone mechanical properties, in a manner involving strengthening of bone resorption rather than suppression of bone formation. GC treatment strongly inhibited bone formation in lupus mice. Sal treatment significantly attenuated osteogenic inhibition and also suppressed hyperactive bone resorption, which recovered the bone mass and mechanical properties of bone in GC-treated lupus mice/lupus mice. The acquired data provide support for further preclinical investigation of Sal as a potential strategy for the treatment of SLE-related bone loss.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 81273518) and Guangdong Province Science and Technology Project (No: 2012B060300027). The authors would like to thank Laura Weber and Jinjin Zhang in Nebraska Medical Center for their help in revising the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Gu Z, Akiyama K, Ma X, et al. Transplantation of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviates lupus nephritis in MRL/lpr mice. Lupus. 2010;19(13):1502–1514. doi: 10.1177/0961203310373782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramsey-Goldman R, Dunn JE, Huang CF, et al. Frequency of fractures in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with United States population data. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(5):882–890. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<882::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bultink IE. Osteoporosis and fractures in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(1):2–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein RS. Clinical practice. Glucocorticoid-induced bone disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(1):62–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1012926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams JD, Wang R, Yang J, Lien EJ. Preclinical and clinical examinations of Salvia miltiorrhiza and its tanshinones in ischemic conditions. Chin Med. 2006;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li YG, Song L, Liu M, Hu ZB, Wang ZT. Advancement in analysis of Salviae miltiorrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (Danshen) J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216(11):1941–1953. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui L, Li T, Liu Y, et al. Salvianolic acid B prevents bone loss in prednisone-treated rats through stimulation of osteogenesis and bone marrow angiogenesis. PloS One. 2012;7(4):e34647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui L, Wu T, Liu YY, Deng YF, Ai CM, Chen HQ. Tanshinone prevents cancellous bone loss induced by ovariectomy in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25(5):678–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y, Su Y, Wang D, et al. Tanshinol attenuates the deleterious effects of oxidative stress on osteoblastic differentiation via Wnt/FoxO3a signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:351895. doi: 10.1155/2013/351895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry D, Sang A, Yin Y, Zheng YY, Morel L. Murine models of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:271694. doi: 10.1155/2011/271694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Cui Y, Chen Y, Gao X, Su Y, Cui L. Effects of dexamethasone, celecoxib, and methotrexate on the histology and metabolism of bone tissue in healthy Sprague Dawley rats. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1245–1253. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S85225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(1):2–17. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin S, Huang J, Zheng L, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in growing rats. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;95(4):362–373. doi: 10.1007/s00223-014-9899-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bynote KK, Hackenberg JM, Korach KS, Lubahn DB, Lane PH, Gould KA. Estrogen receptor-alpha deficiency attenuates autoimmune disease in (NZB x NZW)F1 mice. Genes Immun. 2008;9(2):137–152. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pineau CA, Urowitz MB, Fortin PJ, Ibanez D, Gladman DD. Osteoporosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: factors associated with referral for bone mineral density studies, prevalence of osteoporosis and factors associated with reduced bone density. Lupus. 2004;13(6):436–441. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu1036oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schapira D, Kabala A, Raz B, Israeli E. Osteoporosis in murine systemic lupus erythematosus – a laboratory model. Lupus. 2001;10(6):431–438. doi: 10.1191/096120301678646182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekblom-Kullberg S, Kautiainen H, Alha P, Leirisalo-Repo M, Julkunen H. Frequency of and risk factors for symptomatic bone fractures in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol. 2013;42(5):390–393. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2013.775331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang XL, Qin L, Kwok AW, et al. Alterations of bone geometry, density, microarchitecture, and biomechanical properties in systemic lupus erythematosus on long-term glucocorticoid: a case-control study using HR-pQCT. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(6):1817–1826. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engdahl C, Lindholm C, Stubelius A, Ohlsson C, Carlsten H, Lagerquist MK. Periarticular bone loss in antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(11):2857–2865. doi: 10.1002/art.38114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manolagas SC, Weinstein RS. New developments in the pathogenesis and treatment of steroid-induced osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(7):1061–1066. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henneicke H, Gasparini SJ, Brennan-Speranza TC, Zhou H, Seibel MJ. Glucocorticoids and bone: local effects and systemic implications. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25(4):197–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patschan D, Loddenkemper K, Buttgereit F. Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Bone. 2001;29(6):498–505. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00610-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Chen Y, Zhao H, Zhong L, Wu L, Cui L. Effects of different doses of dexamethasone on bone qualities in rats. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi. 2011;28(4):737–743. 747. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almeida M, Han L, Ambrogini E, Weinstein RS, Manolagas SC. Glucocorticoids and tumor necrosis factor alpha increase oxidative stress and suppress Wnt protein signaling in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(52):44326–44335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.283481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song L, Qiu F, Fan Y, et al. Glucocorticoid regulates interleukin-37 in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(1):111–117. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9791-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Igarashi Y, Lee MY, Matsuzaki S. Acid phosphatases as markers of bone metabolism. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;781(1–2):345–358. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, Benson G. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis – where do we go from here? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2048–2051. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gatti D, Viapiana O, Adami S, Idolazzi L, Fracassi E, Rossini M. Bisphosphonate treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis is associated with a dose dependent increase in serum sclerostin. Bone. 2012;50(3):739–742. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraenzlin ME, Meier C. Parathyroid hormone analogues in the treatment of osteoporosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(11):647–656. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui L, Liu YY, Wu T, Ai CM, Chen HQ. Osteogenic effects of D+beta-3,4-dihydroxyphenyl lactic acid (salvianic acid A, SAA) on osteoblasts and bone marrow stromal cells of intact and prednisone-treated rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30(3):321–332. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8(5):739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohnaka K, Taniguchi H, Kawate H, Nawata H, Takayanagi R. Glucocorticoid enhances the expression of dickkopf-1 in human osteoblasts: novel mechanism of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318(1):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors. 2004;22(4):233–241. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamidouche Z, Hay E, Vaudin P, et al. FHL2 mediates dexamethasone-induced mesenchymal cell differentiation into osteoblasts by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling-dependent Runx2 expression. FASEB J. 2008;22(11):3813–3822. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-106302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, et al. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2002;108(1):17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khosla S. Minireview: the OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Endocrinology. 2001;142(12):5050–5055. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.12.8536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwan Tat S, Padrines M, Theoleyre S, Heymann D, Fortun Y. IL-6, RANKL, TNF-alpha/IL-1: interrelations in bone resorption pathophysiology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishimi Y, Miyaura C, Jin CH, et al. IL-6 is produced by osteoblasts and induces bone resorption. J Immunol. 1990;145(10):3297–3303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wauquier F, Leotoing L, Coxam V, Guicheux J, Wittrant Y. Oxidative stress in bone remodelling and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(10):468–477. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fei AH, Cao Q, Chen SY, et al. Salvianolate inhibits reactive oxygen species production in H(2)O(2)-treated mouse cardiomyocytes in vitro via the TGFbeta pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34(4):496–500. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shockley KR, Rosen CJ, Churchill GA, Lecka-Czernik B. PPAR-gamma2 regulates a molecular signature of marrow mesenchymal stem cells. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:81219. doi: 10.1155/2007/81219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liebschner MA, Keller TS. Hydraulic strengthening affects the stiffness and strength of cortical bone. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33(1):26–38. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8960-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu M, Wang YP, Luo WB, Xuan LJ. Salvianolate inhibits proliferation and endothelin release in cultured rat mesangial cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2001;22(7):629–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu P, Huang XQ, Yuan AH, Yu G, Mei XB, Cui RL. Effects of salvianolate combined with alprostadil and reduced glutathione on progression of chronic renal failure in patients with chronic kidney diseases: a long-term randomized controlled trial. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2012;10(6):641–646. doi: 10.3736/jcim20120607. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]