Abstract

Objectives. To examine sex and racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of 9 substance-use disorders (SUDs)—alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogen or PCP, opiate, amphetamine, inhalant, sedative, and unspecified drug— in youths during the 12 years after detention.

Methods. We used data from the Northwestern Juvenile Project, a prospective longitudinal study of 1829 youths randomly sampled from detention in Chicago, Illinois, starting in 1995 and reinterviewed up to 9 times in the community or correctional facilities through 2011. Independent interviewers assessed SUDs with Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children 2.3 (baseline) and Diagnostic Interview Schedule version IV (follow-ups).

Results. By median age 28 years, 91.3% of males and 78.5% of females had ever had an SUD. At most follow-ups, males had greater odds of alcohol- and marijuana-use disorders. Drug-use disorders were most prevalent among non-Hispanic Whites, followed by Hispanics, then African Americans (e.g., compared with African Americans, non-Hispanic Whites had 32.1 times the odds of cocaine-use disorder [95% confidence interval = 13.8, 74.7]).

Conclusions. After detention, SUDs differed markedly by sex, race/ethnicity, and substance abused, and, contrary to stereotypes, did not disproportionately affect African Americans. Services to treat substance abuse—during incarceration and after release—would reach many people in need, and address health disparities in a highly vulnerable population.

The Department of Justice estimates that, among males born in 2001, 1 in 3 African Americans and 1 in 6 Hispanics will be incarcerated at some point during their lifetime, compared with 1 in 17 non-Hispanic Whites.1 Racial/ethnic minorities are disproportionately incarcerated, especially for drug crimes.2–4 More than 2.4 million youths and adults are currently incarcerated in the United States.5–7 Every year, there are nearly 1.4 million arrests of juveniles; more than 250 000 cases result in detention.8 Substance abuse is a significant problem among youths in the juvenile justice system.9,10 More than 90% report having used illicit drugs.11 Irrespective of sex or race/ethnicity, substance-use disorders (SUDs) are the most common psychiatric disorders among delinquent youths: 49% to 76%12,13 of males and 34% to 77%12–14 of females have an SUD.

After detention, SUDs present a continuing challenge for the community mental health system. Most stays in detention are brief (median, 15 days),15 and when detained youths return to their communities, a substantial proportion may need treatment of SUDs as they age.16 Delinquent youths face challenges attaining adult social roles,17 such as establishing stable careers18 and families19; continued substance abuse further compromises their futures.

Despite its importance, few longitudinal studies of delinquent youths have examined the prevalence of substance abuse during young adulthood. We searched the literature for prospective longitudinal studies of youths in the juvenile justice system conducted since 1990 that met the following criteria: (1) followed youths during young adulthood (≥ 21 years) and (2) measured alcohol or drug use or disorder. Only 3 studies met these criteria (summary table available from authors).16,20–22 These studies found that substance abuse remained prevalent as youths aged.

Although these previous investigations provide important information, they have limitations. Ramchand et al. examined only symptoms of dependence, not diagnoses.20 Diagnoses provide a more systematic, consensually understood, and clinically meaningful description of the frequency, severity, and recency of symptoms.23–26 Moreover, this study oversampled offenders referred for substance abuse treatment, thus biasing the sample.20 Chitsabesan et al. sampled fewer than 100 participants and had nearly 50% attrition; this study was conducted in the United Kingdom, limiting generalizability to the United States.22 Teplin et al. examined youths only up to a median age of 20 years.16,21 Most important, all 3 studies combined drugs with dramatically different etiologies and consequences—for instance, marijuana (now legal in some states27–33) and “hard drugs” (e.g., cocaine, hallucinogens or PCP [phencyclidine], opiates). This approach obfuscates important differences: substances vary widely in their immediate and long-term effects on brain chemistry,34–38 effects on health (such as risk for HIV, fatal overdose, drug-induced psychosis, myocardial infarction, liver disease, neurotoxic effects, and pancreatitis),39–43 and social consequences (e.g., unemployment44 and risk for adolescent pregnancy45).

We addressed the limits of previous investigations. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive epidemiological study of SUDs in delinquent youths during young adulthood (up to median age 28 years). We used data from the Northwestern Juvenile Project to assess 9 SUDs: alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogen or PCP, opiate, amphetamine, inhalant, sedative, and unspecified drug. Focusing on sex and racial/ethnic differences, we used multiple follow-up interviews to examine (1) lifetime prevalence of SUDs and (2) changes in the past-year prevalence of SUDs during the 12 years after youths leave detention. The sample is large (n = 1829), includes males (n = 1172) and females (n = 657), and is racially/ethnically diverse.

This study is timely, providing data needed to address health disparities. Hispanics are especially important to study because they are now the largest ethnic minority in the United States, constituting 16.3% of the population.46 Together, African Americans and Hispanics constitute more than one third of young adults in the general population47 but approximately two thirds of persons incarcerated in juvenile7 and adult facilities.48

METHODS

The most relevant information is summarized here. Additional detail is in the “eMethods,” available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, and is published elsewhere.12,16,49,50

Sample and Procedures

We recruited a stratified random sample of 1829 youths at intake to the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center in Chicago, Illinois, between November 20, 1995, and June 14, 1998, who were awaiting the adjudication or disposition of their case. The Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center is used for pretrial detention and for offenders sentenced for less than 30 days. To ensure adequate representation of key subgroups, we stratified our sample by sex, race/ethnicity (African American, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, other), age (10 to 13 years or ≥ 14 years), and legal status (processed in juvenile or adult court). The sample included 1172 males and 657 females; 1005 African Americans, 296 non-Hispanic Whites, 524 Hispanics, and 4 other race/ethnicity; mean age, 14.9 years (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Face-to-face structured interviews were conducted at the detention center in a private area, most within 2 days of intake.

We conducted follow-up interviews (1) at 3, 4.5, 6, 8, and 12 years after baseline for the entire sample; (2) at 3.5 and 4 years after baseline for a random subsample of 997 participants (600 males and 397 females); and (3) at 10 and 11 years after baseline for the last 800 participants enrolled at baseline (460 males and 340 females). Participants were interviewed whether they lived in the community or in correctional facilities. Interviews were conducted through 2011.

Participants signed either an assent form (if they were aged < 18 years) or a consent form (if they were aged ≥ 18 years). The Northwestern University institutional review board and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention institutional review board approved all study procedures and waived parental consent for persons younger than 18 years, consistent with federal regulations regarding research with minimal risk.23

Measures

Baseline.

We administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version 2.3 (DISC 2.3),51,52 based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition (DSM-III-R), the most recent version available at the time. The DISC 2.3 generates diagnoses for alcohol-, marijuana-, and “other” illicit drug–use disorders (e.g., “hard drugs” such as cocaine, opiates, hallucinogens or PCP) for the past 6 months. We derived diagnoses for specific “other” illicit drug use–disorders the same way the DISC 2.3 scores alcohol- and marijuana-use disorders.

Follow-up interviews.

For follow-up interviews, we administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version IV (DIS-IV)53,54 because the DISC was not sufficiently comprehensive to cover the substance use behaviors of aging delinquent youths. The DIS-IV assesses SUDs in the year before the interview for alcohol, marijuana, and the following specific “other” illicit drugs: amphetamines, sedatives, cocaine, opiates, hallucinogens or PCP, inhalants, and unspecified drugs. As in our earlier work,16 we checked that changes in prevalence over time were not attributable to changes in measurement. To facilitate comparison with other large-scale epidemiological studies of SUDs,55–58 we report both lifetime and past-year prevalence.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted all analyses with commercial software (Stata version 12; Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX) with its survey routines. To generate prevalence estimates and inferential statistics that reflect Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center’s population, we assigned each participant a sampling weight augmented with a nonresponse adjustment to account for missing data.59 We used Taylor series linearization to estimate standard errors.60,61

Because some participants were interviewed more often than others, we summarize prevalence at 6 time points for the entire sample: baseline (time 0) and time 1 through time 5, corresponding to approximately 3, 5, 6, 8, and 12 years after baseline. Table A summarizes sample demographics and retention, and shows that 83% of participants had a time-5 interview. Race/ethnicity (African American, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, other) was self-identified.

We used logistic regression to examine sex and racial/ethnic differences in lifetime prevalence 12 years after baseline.

Changes in prevalence over time.

We used all available interviews, with an average of 7 interviews per person (range = 1–10 interviews per person). We used generalized estimating equations62 to fit marginal models examining (1) differences in the prevalence of SUDs by sex and race/ethnicity over time and (2) changes in the prevalence of disorders over time. Unless otherwise noted, odds ratios contrast sex and race/ethnicity over time.

All generalized estimating equation models included covariates for sex, race/ethnicity (African American, Hispanic, or non-Hispanic White), aging (time since baseline), age at baseline (10–18 years), and legal status at detention. We excluded the 4 participants who identified as “other” race/ethnicity. We modeled time since baseline with restricted cubic splines. When main effects were significant, we estimated models with the corresponding interaction terms. We included only statistically significant interaction terms in final models. For models with significant interactions between sex and aging, we report model-based odds ratios for sex differences at 3, 5, 8, and 12 years after baseline. There were no significant interactions between sex and race/ethnicity; for the interested reader, however, we provide prevalence estimates for specific subgroups in the tables available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org. Because incarceration may restrict access to substances, all models included covariates for time incarcerated before each interview. We estimated all generalized estimating equation models with sampling weights to account for study design.

Missing data.

Although attrition was modest (Table A), and we augmented sampling weights with nonresponse adjustments, we used multiple imputation by chained equations63–65 to examine the sensitivity of our findings to unplanned missing data. We imputed data under the assumption that participants who dropped out had up to twice the odds of disorder compared with participants who remained in the study.66,67 Because there were no substantive differences in findings (tables available from authors), we present results with the original data.

RESULTS

Twelve years after baseline (median age = 28 years), more than 90% of males and nearly 80% of females had a lifetime SUD (Table 1). Compared with females, males had higher lifetime prevalence of any SUD and its subcategories alcohol-use disorder, any drug-use disorder, and marijuana-use disorder. By contrast, females had higher lifetime prevalence of cocaine-, opiate-, amphetamine-, and sedative-use disorder. Lifetime prevalence of “other” illicit drug–use disorder and its subcategories—cocaine, opiate, amphetamine, and hallucinogen or PCP (males only)—were significantly higher among non-Hispanic Whites, followed by Hispanics, then African Americans (Tables B and C, available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Among females, minorities had lower lifetime prevalence of alcohol-use disorder. Sex and racial/ethnic differences remained even when we excluded participants who had been incarcerated during the entire follow-up period (tables available from authors).

TABLE 1—

Lifetime Prevalence of Substance-Use Disorders by Sex From the Baseline Interview (1995–1998) Through Time 5 (12 Years Later): Cook County, Chicago, IL

| Prevalence, % (SE) |

||||

| Disorder | Total | Male | Female | Male vs Female, OR (95% CI) |

| Any substance–use disorder | 90.4 (1.3) | 91.3 (1.4) | 78.5 (1.7) | 2.9 (2.0, 4.2) |

| Alcohol-use disorder | 77.4 (1.9) | 78.6 (2.0) | 62.4 (2.0) | 2.2 (1.7, 2.9) |

| Any drug–use disorder | 85.1 (1.6) | 86.2 (1.7) | 71.0 (1.8) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.5) |

| Marijuana-use disorder | 83.4 (1.6) | 84.5 (1.8) | 68.3 (1.9) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.5) |

| Other illicit drug–use disorder | 22.5 (1.6) | 22.2 (1.8) | 25.3 (2.0) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) |

| Cocaine | 10.9 (0.9) | 10.5 (0.9) | 16.6 (1.9) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) |

| Hallucinogen or PCP | 11.3 (1.2) | 11.3 (1.3) | 11.6 (1.9) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.5) |

| Opiate | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.6) | 5.8 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) |

| Amphetamine | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) | 3.5 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.5) |

| Inhalant | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.2, 1.02) |

| Sedative | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | 5.0 (1.8) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) |

| Unspecified druga | 9.3 (1.3) | 9.4 (1.4) | 7.9 (1.0) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; PCP = phencyclidine. Descriptive statistics are weighted to adjust for sampling design and to reflect the demographic characteristics of the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center. All substance-use disorders are measured without impairment. At baseline, the sample included 1172 males and 657 females. At time 5, the sample included 943 males and 576 females.

Includes other drugs not listed (e.g., betel nut, nitrous oxide, amyl nitrate [poppers], and ecstasy). Not assessed at baseline.

Prevalence of Past-Year Disorders Over Time

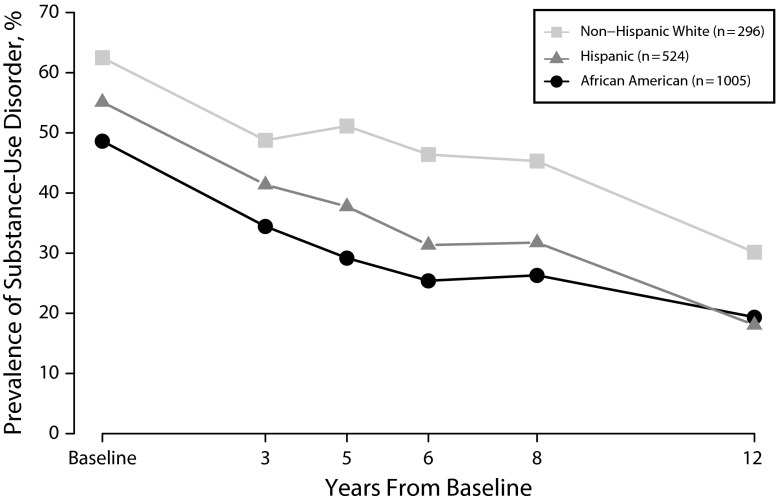

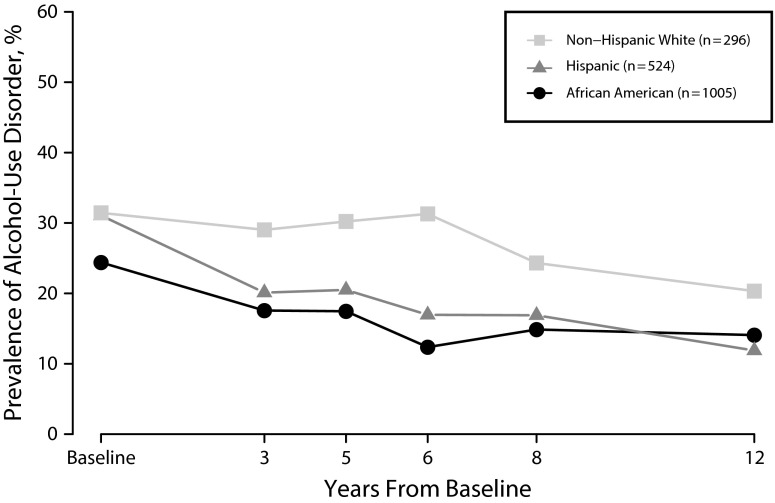

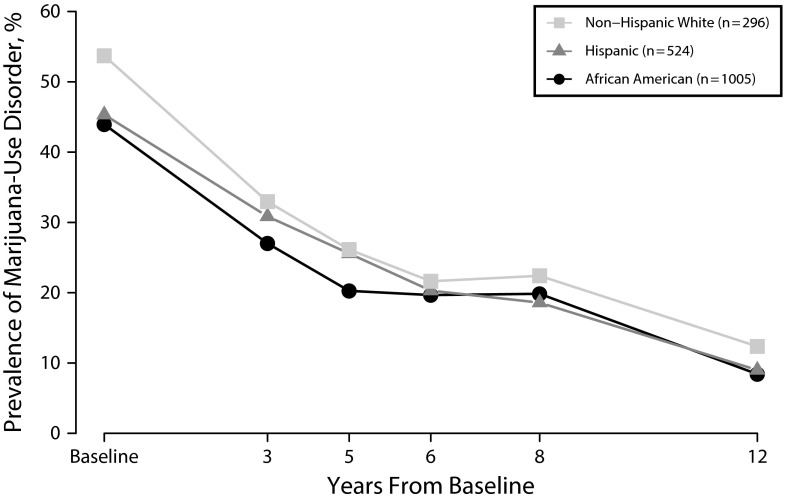

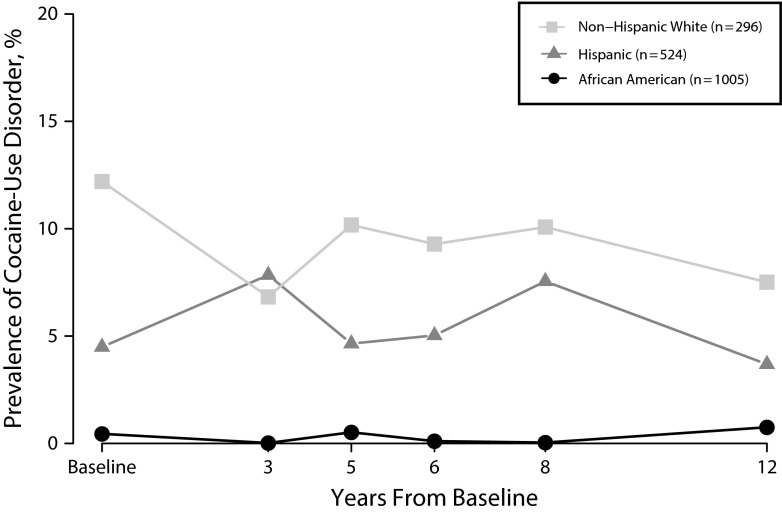

Figure 1 illustrates racial/ethnic differences over time for any SUD. Figures 2, 3, and 4 illustrate the differences for alcohol-, marijuana-, and cocaine-use disorders, respectively. Additional figures are provided in Figures A through N, available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org. Tables D through H (available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provide specific prevalence estimates for all disorders. We describe findings by type of disorder.

FIGURE 1—

Prevalence of Substance-Use Disorder by Race/Ethnicity From Baseline (1995–1998, at Detention) Through Time 5 (12 Years Later): Cook County, Chicago, IL

Note. Adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for racial/ethnic differences over time were 1.9 (1.5, 2.3) for non-Hispanic White vs African American, 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) for non-Hispanic White vs Hispanic, and 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) for Hispanic vs African American.

FIGURE 2—

Prevalence of Alcohol-Use Disorder by Race/Ethnicity From Baseline (1995–1998, at Detention) Through Time 5 (12 Years Later): Cook County, Chicago, IL

Note. Adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for racial/ethnic differences over time were 1.7 (1.4, 2.2) for non-Hispanic White vs African American, 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) for non-Hispanic White vs Hispanic, and 1.2 (0.96, 1.5) for Hispanic vs African American.

FIGURE 3—

Prevalence of Marijuana-Use Disorder by Race/Ethnicity From Baseline (1995–1998, at Detention) Through Time 5 (12 Years Later): Cook County, Chicago, IL

Note. Adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for racial/ethnic differences over time were 1.3 (1.02, 1.6) for non-Hispanic White vs African American, 1.05 (0.8, 1.3) for non-Hispanic White vs Hispanic, and 1.2 (0.96, 1.5) for Hispanic vs African American.

FIGURE 4—

Prevalence of Cocaine-Use Disorder by Race/Ethnicity From Baseline (1995–1998, at Detention) Through Time 5 (12 Years Later): Cook County, Chicago, IL

Note. Adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for racial/ethnic differences over time were 32.1 (13.8, 74.7) for non-Hispanic White vs African American, 1.5 (1.04, 2.2) for non-Hispanic White vs Hispanic, and 21.2 (9.0, 50.1) for Hispanic vs African American.

Any SUD, Alcohol-Use Disorder, and Any Drug-Use Disorder

Although prevalence decreased, 12 years after baseline nearly 1 in 5 participants had an SUD and more than 1 in 10 had a drug-use disorder. The rate of decrease depended on sex (Table I, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Sex differences.

There were no significant sex differences at baseline. After baseline, however, males had higher prevalence of SUDs than females (Figure A). For example, 5 years after baseline, males had 2.34 times the odds of alcohol-use disorder compared with females (95% CI = 1.76, 3.13). Sex differences were largest in the first half of the follow-up period.

Racial/ethnic differences.

Throughout the follow-up period, non-Hispanic Whites were significantly more likely than minorities to have any SUD and its subcategories, alcohol-use disorder and any drug–use disorder (Table I). For example, 8 years after baseline, nearly half of non-Hispanic Whites had any SUD compared with about a quarter of African Americans and nearly a third of Hispanics (Table E). Moreover, Hispanics had significantly higher prevalence of any SUD and its subcategory, any drug–use disorder, compared with African Americans.

Marijuana-Use Disorder

Prevalence of marijuana-use disorder decreased over time, but the rate of decrease depended on sex (Figure E and Table I).

Sex differences.

There were no significant sex differences at baseline or 12 years later. In the interim, however, males had significantly higher prevalence than females. For example, 5 years after baseline, prevalence was 22.1% among males and 13.5% among females (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.51; 95% CI = 1.93, 3.26).

Racial/ethnic differences.

Non-Hispanic Whites had greater odds of marijuana-use disorder compared with African Americans.

“Other” Illicit Drug–Use Disorder

“Other” illicit drug–use disorder includes “hard drugs,” such as cocaine-, hallucinogen or PCP-, opiate-, amphetamine-, sedative-, and unspecified drug–use disorder. Overall, prevalence did not decrease over time, and there were no significant sex differences (Table J, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Racial/ethnic differences.

African Americans had the lowest prevalence of “other” illicit drug–use disorder, followed by Hispanics, then non-Hispanic Whites (Tables E through G). For example, 5 years after baseline, prevalence was 1.7% (African Americans), 7.1% (Hispanics), and 20.0% (non-Hispanic Whites). At this time point, non-Hispanic Whites had more than 19 times and Hispanics had more than 8 times the odds of “other” illicit drug–use disorder compared with African Americans (Table J). However, prevalence increased over time among African Americans (e.g., 8 years after baseline, 2.6%; AOR = 1.16 per year; 95% CI = 1.14, 1.28).

Subcategories of “Other” Illicit Drug–Use Disorder

Prevalence of hallucinogen or PCP–use disorder and amphetamine-use disorder decreased; opiate-use disorder and unspecified drug–use disorder increased. Table K (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) shows AORs describing sex and racial/ethnic differences. Figure 4 and Figures I through N illustrate these differences for cocaine, opiate, and hallucinogen or PCP.

Sex differences.

Females had significantly higher odds of opiate-, amphetamine-, and sedative-use disorder.

Racial/ethnic differences.

Throughout the follow-up, prevalence was highest among non-Hispanic Whites, followed by Hispanics then African Americans. Compared with African Americans, non-Hispanic Whites had more than 30 times the odds of cocaine-use disorder (Figure 4), 18 times the odds of hallucinogen or PCP–use disorder, and 50 times the odds of opiate-use disorder (Table K). Hispanics had more than 20 times the odds of cocaine-use disorder, and more than 7 times the odds of hallucinogen or PCP–use disorder and opiate-use disorder compared with African Americans.

Substance-Use Disorders Among Participants in the Community

Because substance use is restricted in jails and prisons, we examined SUDs only among participants who had lived in the community the entire year before their 12-year interview. This subgroup consisted of 434 males and 480 females. The racial/ethnic distribution was 499 African Americans, 239 Hispanics, 174 non-Hispanic Whites, and 2 “other” race/ethnicity.

Tables L, M, and N (available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) show prevalence estimates and demographic differences at time 5 (12 years after baseline) for all SUDs. Prevalence estimates and demographic differences for the subgroup were substantially similar to those for the overall sample.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study of delinquent youths to document that SUDs during young adulthood differ markedly by sex, race/ethnicity, and substance abused. Drug-use disorders such as cocaine, hallucinogen or PCP, opiate, amphetamine, and sedatives were rare among African Americans, but prevalent among non-Hispanic Whites. Marijuana-use disorder was the most prevalent SUD during most of young adulthood, and more common among males than females. However, 12 years after baseline, alcohol-use disorder surpassed marijuana-use disorder.

Prevalence of SUDs dropped from about 50% at baseline (median age = 15 years) to nearly 20% 12 years later (median age = 28 years) among males and females. Similar to other delinquent behaviors, prevalence among females declined more rapidly than among males. This difference may be because delinquent females are more likely than delinquent males to receive services,68 which may hasten recovery. Moreover, males are incarcerated more frequently and for longer periods of time than females, thus decreasing their ability to build a stable life and positive connection in the community.17,69 Despite the decrease over time, prevalence of drug-use disorders is still higher than in the general population.55,56,70

We found striking racial/ethnic differences. Contrary to popular stereotypes of African Americans,71,72 prevalence of drug-use disorders such as cocaine and hallucinogen or PCP was lowest among African Americans, followed by Hispanics, then non-Hispanic Whites. For example, non-Hispanic Whites had more than 30 times the odds of having cocaine-use disorder than African Americans. These racial/ethnic differences persisted even after we controlled for the additional time that African Americans spend in correctional facilities, where access to substances is restricted. Our findings add to the growing debate about how the “War on Drugs” has disproportionately affected African American youths and young adults.73–75 Recent investigations have found that although African American adolescents are no more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to use or sell drugs, they are more likely be arrested on drug-related charges.76,77

Lifetime SUDs were the rule, not the exception. By median age 28 years, more than 90% of males and nearly 80% of females had 1 or more SUDs—rates substantially higher than in the general population—irrespective of sex or race/ethnicity. (Comparative analyses of estimates obtained from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions [NESARC], for those aged 25–30 years, are available from the authors.) The magnitude of difference, however, is notable. For example, two thirds of African American females had lifetime marijuana-use disorder compared with less than 10% of those in the NESARC; more than 85% of non-Hispanic White males had lifetime marijuana-use disorder compared with less than one fifth in the NESARC. A quarter of Hispanic females had ever had a hallucinogen or PCP–use disorder compared with about 2% in the general population.

Limitations

Our sample included participants from only 1 jurisdiction and may not be generalizable to other parts of the country. We had too few participants of “other” race/ethnicity to generalize to racial/ethnic groups such as Asian American or Native American.

Findings do not take into account mental health or substance abuse services. Although recent studies find few differences in results between DSM-IV and DSM-V criteria,78,79 prevalence estimates might have been somewhat different had we used DSM-V. We did not examine comorbid psychiatric disorders, or the age at onset of SUD relative to comorbid disorders. Despite these limitations, our findings have implications for future research and public health policy.

Directions for Future Research

First, investigate incarcerated persons after release. Incarcerated populations have among the highest lifetime prevalence of SUDs.12,80,81 Yet nearly all large-scale epidemiological studies of SUDs exclude them.16,82 Ironically, we know least about the people who are at the greatest risk for the consequences of SUDs. Studies of US populations are especially needed because it has the highest incarceration rate in the world83: 707 inmates per 100 000 residents, compared with 118 in Canada, 148 in England and Wales, and 470 in Russia.

Second, examine how patterns of incarceration affect substance abuse. Drug abuse and involvement in the drug economy often lead to arrest and incarceration. Incarceration may also exacerbate risk factors for substance abuse—for example, increasing depression,84 interrupting education,85 disrupting intimate relationships,86,87 and increasing deviant peer associations.88,89 Yet, to our knowledge, no large-scale study has examined how patterns of incarceration—number and duration of incarcerations, age when incarcerated, and experiences during parole and probation—affect the development, persistence, desistance, and recurrence of SUDs. Prospective studies are essential to address these public health concerns.

Implications for Public Policy

First, address—as a health disparity—the disproportionate incarceration of African Americans for drug offenses. Drug abuse appears to have greater consequences for racial/ethnic minorities, especially African Americans, than for non-Hispanic Whites. Poor people, who are disproportionately racial/ethnic minorities, may be less able to afford treatment and, if arrested, less able to obtain effective legal counsel than persons of greater means. Specialized drug courts have the potential to divert persons to treatment, avoiding incarceration and associated consequences.90–92

Second, improve the breadth and quality of preventive interventions, services during correctional stays, and care after prisoners are released. To date, insufficient services have been available to treat substance abuse. For example, about half of youths in detention93 and nearly 80%94 of adults in prison do not receive needed treatment of drug abuse.94–96 Although prisoners continue to be ineligible for Medicaid while serving time,97 the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act97 expands services after release: it mandates equal coverage for SUD treatment, including it as an “essential health benefit,”97 which must be provided by Medicaid and the insurance exchanges. Parity increases treatment provision for SUDs.98 Moreover, of people released from jails, 25% to 30% could enroll in Medicaid in states that expanded Medicaid, and about 20% could enroll in a marketplace insurance plan.99

Despite these improvements, service provision will continue to challenge the field for several reasons:

Prisoners are dependent on services provided by their facility.99 Evidence-based treatment of mental disorders and substance abuse is critical. Yet, availability and quality of services vary.99

Substance use disorders are often comorbid with other psychiatric disorders, particularly among youths in the juvenile justice system.21,49 Accurate diagnosis of comorbid conditions requires systematic assessment of both mental health and substance use problems.100,101 Traditional treatments are less effective for persons with comorbid disorders. Integrated treatment approaches are preferable, but not widely available.102

After release, residents of states that have not expanded Medicaid (19 states as of January 2016103) will have fewer resources available to them as federal funding declines for safety net services.104,105 Nearly 80% of funding for SUD treatment comes from public sources, of which Medicaid accounts for approximately one fourth.106

Even in states that expanded Medicaid, specialty outpatient services (where most SUD treatment takes place) that accept Medicaid are unavailable in 40% of counties105; inpatient programs that have more than 16 beds are not covered.107

Substance abuse is among the most serious health problems in the United States. Illicit drug use and excessive alcohol consumption cost $193 billion108 and $223.5 billion per year,109 respectively, which includes costs associated with disruptions in work, increased health problems, and crime. Services to treat substance abuse—during incarceration and after release—would reach a sizeable proportion of people in need,94 and address health disparities in a highly vulnerable population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R01DA019380, R01DA022953, and R01DA028763; National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH54197 and R01MH59463 (Division of Services and Intervention Research and Center for Mental Health Research on AIDS); and grants 1999-JE-FX-1001, 2005-JL-FX-0288, and 2008-JF-FX-0068 from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Major funding was also provided by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Center for Mental Health Services, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment), the NIH Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention), the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, the NIH Office of Rare Diseases, Department of Labor, Department of Housing and Urban Development, The William T. Grant Foundation, and The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Additional funds were provided by The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Open Society Foundations, and The Chicago Community Trust.

Zaoli Zhang, MS, prepared the data and generated modified diagnostic algorithms. Jessica Jakubowski, PhD, and Hongyun Han, PhD, provided assistance preparing data. Celia Fisher, PhD, provided invaluable advice on the project. We thank our participants for their time and willingness to participate, as well as the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center, Cook County Department of Corrections, and Illinois Department of Corrections for their cooperation.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The Northwestern University institutional review board and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention institutional review board approved all study procedures consistent with federal regulations regarding research with minimal risk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonczar TP. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2003. Prevalence of imprisonment in the U.S. population, 1974–2001. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. [Google Scholar]

- 2. James DJ. Profile of jail inmates, 2002. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2004. NCJ 201932.

- 3.Sickmund M, Sladky A, Kang W. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2014. Easy access to juvenile court statistics: 1985–2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bureau of Justice Statistics. Federal criminal case processing statistics. 2013. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/fjsrc/var.cfm?ttype=one_variable&agency=BOP&db_type=Prisoners&saf=IN. Accessed August 8, 2014.

- 5. Stephan J, Walsh G. Census of jail facilities, 2006. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2011.

- 6.Carson EA, Golinelli D. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2013. Prisoners in 2012—advanced counts. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sickmund M, Sladky TJ, Kang W, Puzzanchera C. Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement. 2013. Available at: http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp. Accessed August 8, 2014.

- 8.Puzzanchera C, Hockenberry S. National disproportionate minority contact databook: developed by the National Center for Juvenile Justice for the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. 2013. Available at: http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/dmcdb. Accessed February 20, 2014.

- 9.Dembo R, Wareham J, Schmeidler J. A longitudinal study of cocaine use among juvenile arrestees. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2007;17(1):83–109. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dembo R, Wareham J, Schmeidler J. Drug use and delinquent behavior: a growth model of parallel processes among high-risk youths. Crim Justice Behav. 2007;34(5):680–696. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClelland GM, Teplin LA, Abram KM. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2004. Detection and prevalence of substance use among juvenile detainees. NCJ 203934. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, Mericle AA. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(12):1133–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harzke AJ, Baillargeon J, Baillargeon G et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the Texas juvenile correctional system. J Correct Health Care. 2012;18(2):143–157. doi: 10.1177/1078345811436000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lederman CS, Dakof GA, Larrea MA, Li H. Characteristics of adolescent females in juvenile detention. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2004;27(4):321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hockenberry S. Juveniles in residential placement, 2011. Juvenile offenders and victims: National Report Series Bulletin. Rockville, MD: US Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2014.

- 16.Teplin LA, Welty LJ, Abram KM, Dulcan MK, Washburn JJ. Prevalence and persistence of psychiatric disorders in youth after detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(10):1031–1043. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massoglia M, Uggen C. Settling down and aging out: toward an interactionist theory of desistance and the transition to adulthood. AJS. 2010;116(2):543–582. doi: 10.1086/653835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiesner M, Kim HK, Capaldi DM. History of juvenile arrests and vocational career outcomes for at-risk young men. J Res Crime Delinq. 2010;47(1):91–117. doi: 10.1177/0022427809348906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopoo LM, Western B. Incarceration and the formation and stability of marital unions. J Marriage Fam. 2005;67(3):721–734. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramchand R, Morral AR, Becker K. Seven-year life outcomes of adolescent offenders in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):863–870. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.142281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abram KM, Zwecker NA, Welty LJ, Hershfield JA, Dulcan MK, Teplin LA. Comorbidity and continuity of psychiatric disorders in youth after detention: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):84–93. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chitsabesan P, Rothwell J, Kenning C et al. Six years on: a prospective cohort study of male juvenile offenders in secure care. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(6):339–347. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angold A, Costello EJ. Developing a developmental epidemiology. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1991. pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaffer D. Concepts of diagnostic classification. In: Wiener JM, Dulcan MK, editors. Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004. pp. 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newcomb MD, Galaif ER, Locke TF. Substance use diagnosis within a community sample of adults: distinction, comorbidity, and progression over time. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2001;32(3):239–247. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheier LM, Newcomb MD. Differentiation of early adolescent predictors of drug use versus abuse: a developmental risk-factor model. J Subst Abuse. 1991;3(3):277–299. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(10)80012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pacula RL, Powell D, Heaton P, Sevigny EL. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013. Assessing the effects of medical marijuana laws on marijuana and alcohol use: the devil is in the details. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Higher minimum wage passes in 4 states; Florida defeats marijuana measure. New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/05/us/politics/higher-minimum-wages-prove-popular-in-fla-marijuana-is-less-so.html?ref=topics. Accessed March 1, 2015.

- 29.State of Alaska. Ballot Measure No. 2. An Act to Tax and Regulate the Production, Sale, and Use of Marijuana. Available at: https://www.elections.alaska.gov/doc/bml/BM2-13PSUM-ballot-language.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2015.

- 30.State of Colorado. Amendment 64. Use and Regulation of Marijuana. Available at: http://www.leg.state.co.us/LCS/Initiative%20Referendum/1112initrefr.nsf/c63bddd6b9678de787257799006bd391/cfa3bae60c8b4949872579c7006fa7ee/$FILE/Amendment%2064%20-%20Use%20&%20Regulation%20of%20Marijuana.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2015.

- 31.State of Oregon. Measure 91: Control, Regulation, and Taxation of Marijuana and Industrial Hemp Act. November 4, 2014. Available at: http://www.oregon.gov/olcc/marijuana/Documents/Measure91.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2015.

- 32.State of Washington. Initiative Measure No. 502. July 8, 2011. Available at: http://sos.wa.gov/_assets/elections/initiatives/i502.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2015.

- 33. Washington DC. Marijuana Legalization, Initiative 71. November 2014. Available at: http://ballotpedia.org/Washington_D.C._Marijuana_Legalization,_Initiative_71_%28November_2014%29. Accessed March 1, 2015.

- 34.Lyoo IK, Streeter CC, Ahn KH et al. White matter hyperintensities in subjects with cocaine and opiate dependence and health comparison subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2004;131(2):135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundqvist T. Cognitive consequences of cannabis use: comparison with abuse of stimulants and heroin with regard to attention, memory and executive functions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81(2):319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.González S, Grazia Cascio M, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Fezza F, DiMarzo V, Ramos J. Changes in endocannabinoid contents in the brain of rats chronically exposed to nicotine, ethanol or cocaine. Brain Res. 2002;954:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.González S, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Sparpaglione V, Parolaro D, Ramos JA. Chronic exposure to morphine, cocaine or ethanol in rats produced different effects in brain cannabinoid CB receptor binding and mRNA levles. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medina KL, Schweinsburg AD, Cohen-Zion M, Nagel BJ, Tapert SF. Effects of alcohol and combined marijuana and alcohol use during adolescence on hippocampal volume and asymmetry. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29(1):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):55–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han B, Gfroerer J, Colliver J. Assocations between duration of illicit drug use and health conditions: results from the 2005–2007 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(4):289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J. Major physcial and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27(3):253–262. doi: 10.1080/09595230801923702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singleton J, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Zabransky T. Mortality among amphetamine users: a systematic review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105(1-2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Consequences of Adolescent Drug Use: Impact on the Lives of Young Adults. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeSimone J. Illegal drug use and employment. J Labor Econ. 2002;20(4):952–977. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mensch B, Kandel DB. Drug use as a risk factor for premarital teen pregnancy and abortion in a national sample of young White women. Demography. 1992;29(3):409–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. Suitland, MD: US Census Bureau; 2011.

- 47.Suitland, MD: US Census Bureau; 2013. Annual estimates of the resident population by sex, age, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States and States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.West HC, Sabol WJ, Grennman SJ. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2011. Prisoners in 2009. Bureau of Justice Statistics, statistical tables. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1097–1108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abram KM, Teplin LA, Charles DR, Longworth SL, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):403–410. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK et al. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):865–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwab-Stone ME, Shaffer D, Dulcan MK et al. Criterion validity of the NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version 2.3 (DISC-2.3) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):878–888. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robins L, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV) St Louis, MO: Washington University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [erratum Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(7):709] Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74(3):223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Anthony JC. Epidemiological patterns of extra-medical drug use in the United States: evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, 2001–2003. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(2-3):210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA. 1990;264(19):2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of Health Surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. pp. 159–191. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cochran W. Sampling Techniques. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levy P, Lemeshow S. Sampling of Populations: Methods and Applications. 3rd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219–242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Azur MJ, Stuart EA, Frangakis C, Leaf PJ. Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20(1):40–49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Siddique J, Harel O, Crespi CM. Addressing missing data mechanism uncertainty using multiple-model multiple imputation: application to a longitudinal clinical trial. Ann Appl Stat. 2012;6(4):1814–1837. doi: 10.1214/12-AOAS555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Siddique J, Harel O, Crespi CM, Hedeker D. Binary variable multiple-model multiple imputation to address missing data mechanism uncertainty: application to a smoking cessation trial. Stat Med. 2014;33(17):3013–3028. doi: 10.1002/sim.6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Washburn JJ, Pikus AK. Detecting mental disorder in juvenile detainees: who receives services. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1773–1780. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Crime and deviance in the life course: the salience of adult social bonds. Am Sociol Rev. 1990;55(5):609–627. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, National Survey on Drug Use and Health; 2008. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findings. Series H-34, DHHS publication no. SMA 08–4343. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Welch K. Black criminal stereotypes and racial profiling. J Contemp Crim Justice. 2007;23(3):276–288. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Windsor LC, Negi N. Substance abuse and dependence among low income African Americans: using data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health to demystify assumptions. J Addict Dis. 2009;28(3):258–268. doi: 10.1080/10550880903028510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dumont DM, Allen SA, Brockmann BW, Alexander NE, Rich JD. Incarceration, community health, and racial disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):78–88. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dumont DM, Brockmann B, Dickman S, Alexander N, Rich JD. Public health and the epidemic of incarceration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:325–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moore LD, Elkavich A. Who’s using and who’s doing time: incarceration, the war on drugs, and public health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(suppl 1):S176–S180. doi: 10.2105/ajph.98.supplement_1.s176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kakade M, Duarte CS, Liu X et al. Adolescent substance use and other illegal behaviors and racial disparities in criminal justice system involvement: findings from a US national survey. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1307–1310. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beckett K, Nyrop K, Pfingst L, Bowen M. Drug use, drug possession arrests, and the question of race: lessons from Seattle. Soc Probl. 2005;52(3):419–441. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(8):834–851. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Diamond PM, Wang EW, Holzer CE, Thomas C, Cruser DA. The prevalence of mental illness in prison. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2001;29(1):21–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1013164814732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Proctor SL. Substance use disorder prevalence among female state prison inmates. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(4):278–285. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.668596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Conway KP, Colliver JD. Developments in the epidemiology of drug use and drug use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(8):1494–1502. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. World prison brief. 2014. Available at: http://www.prisonstudies.org/world-prison-brief. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 84.Turney K, Wildeman C, Schnittker J. As fathers and felons: explaining the effects of current and recent incarceration on major depression. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53(4):465–481. doi: 10.1177/0022146512462400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hjalmarsson R. Criminal justice involvement and high school completion. J Urban Econ. 2008;63(2):613–630. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harman JJ, Smith VE, Egan LC. The impact of incarceration on intimate relationships. Crim Justice Behav. 2007;34(6):794–815. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Petersilia J. When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Level LD, Chamberlain P. Association with delinquent peers: intervention effects for youth in the juvenile justice system. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2005;33(3):339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3571-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Button TM, Stallings MC, Rhee SH, Corley RP, Boardman JD, Hewitt JK. Perceived peer delinquency and the genetic predisposition for substance dependence vulnerability. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100(1-2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.King RS, Pasquarella J. Drug Courts: A Review of the Evidence. Washington, DC: The Sentencing Project; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gottfredson DC, Najaka SS, Kearley B. Effectiveness of drug treatment courts: evidence from a randomized trial. Criminol Public Policy. 2003;2(2):171–196. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Koetse W, Lattimore PK. Assessing the long-term impact of drug court participation on recidivism with generalized estimating equations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mulvey EP, Schubert CA, Chung H. Service use after court involvement in a sample of serious adolescent offenders. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2007;29(4):518–544. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety. JAMA. 2009;301(2):183–190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Karberg JC, James DJ. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2005. Substance dependence, abuse, and treatment of jail inmates, 2002. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mumola CJ, Karberg JC. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2006. Drug use and dependence, state and federal prisoners, 2004. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub L No. 111-148 (March 23, 2010).

- 98.Wen H, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Gaydos LM, Druss BG. State parity laws and access to treatment for substance use disorder in the United States: implications for federal parity legislation. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1355–1362. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Regenstein M, Rosenbaum S. What the Affordable Care Act means for people with jail stays. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(3):448–454. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miele GM, Trautman KD, Hasin DS. Assessing comorbid mental and substance-use disorders: a guide for clinical practice. J Pract Psychiatry Behav Health. 1996;2(5):272–282. [Google Scholar]

- 101.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Comorbidity: Addiction and Other Mental Illnesses. [Google Scholar]

- 102.O’Brien CP, Charney DS, Lewis L et al. Priority actions to improve the care of persons with co-occurring substance abuse and other mental disorders: a call to action. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(10):703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion. Decision. 2016. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act. Accessed January 19, 2016.

- 104.Jones DK, Singer PM, Ayanian JZ. The changing landscape of Medicaid: practical and political considerations for expansion. JAMA. 2014;311(19):1965–1966. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cummings JR, Wen H, Ko M, Druss BG. Race/ethnicity and geographic access to Medicaid substance use disorder treatment facilities in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):190–196. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mark TL, Levit KR, Vandivort-Warren R, Buck JA, Coffey RM. Changes in US spending on mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1986–2005, and implications for policy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(2):284–292. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Social Security Act, 42 USC 1396d, §1905 (1965).

- 108.National Drug Intelligence Center. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2011. The economic impact of illicit drug use on American society. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(5):516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]