Abstract

Objectives. To evaluate the additional burdens experienced by Texas abortion patients whose nearest in-state clinic was one of more than half of facilities providing abortion that had closed after the introduction of House Bill 2 in 2013.

Methods. In mid-2014, we surveyed Texas-resident women seeking abortions in 10 Texas facilities (n = 398), including both Planned Parenthood–affiliated clinics and independent providers that performed more than 1500 abortions in 2013 and provided procedures up to a gestational age of at least 14 weeks from last menstrual period. We compared indicators of burden for women whose nearest clinic in 2013 closed and those whose nearest clinic remained open.

Results. For women whose nearest clinic closed (38%), the mean one-way distance traveled was 85 miles, compared with 22 miles for women whose nearest clinic remained open (P ≤ .001). After adjustment, more women whose nearest clinic closed traveled more than 50 miles (44% vs 10%), had out-of-pocket expenses greater than $100 (32% vs 20%), had a frustrated demand for medication abortion (37% vs 22%), and reported that it was somewhat or very hard to get to the clinic (36% vs 18%; P < .05).

Conclusions. Clinic closures after House Bill 2 resulted in significant burdens for women able to obtain care.

Since 2010, US states have enacted nearly 300 abortion restrictions, with 51 new restrictions passed in the first half of 2015 alone.1 Of note is the increase in laws that make it more difficult to provide abortion services by imposing expensive or logistically difficult requirements on facilities and clinicians, which are often referred to as Targeted Regulation of Abortion Provider (TRAP) laws. In the summer of 2013, Texas passed House Bill 2 (HB2), a TRAP law that restricted abortion services in 4 ways: (1) physicians performing abortions must have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the facility, (2) medication abortion must be administered according to the mifepristone label approved by the Food and Drug Administration (with some dosage exceptions), (3) most abortions at or after 20 weeks “postfertilization” are banned, and (4) all abortions must be performed in facilities meeting the requirements of an ambulatory surgical center (ASC).2 The first 3 provisions of HB2 were enforced by November 1, 2013; the ASC requirement is currently enjoined pending a US Supreme Court decision, as is the admitting privileges requirement as it applies to 2 Texas facilities.

Eight of the 41 Texas facilities providing abortion care in April 2013 closed or stopped providing abortion services after the introduction of the HB2 bill.3 Eleven more facilities closed or stopped providing abortions when HB2 was enforced, primarily because physicians experienced barriers to obtaining hospital admitting privileges.3 Although some clinics were able to reopen once physicians successfully obtained admitting privileges, still others closed, resulting in 19 licensed facilities providing abortions in Texas by July 2014—a 54% reduction in the number of facilities since April 2013.4

Recent studies have reported the effects of state-level abortion restrictions on abortion rates, out-of-state travel for abortion, and the consequences for women of being denied a wanted abortion because of clinic gestational age limits, but less is known about the burdens that women experience as a result of clinic closures.5–9 Evaluating the impact of a substantially reduced number of abortion clinics in Texas on hardships experienced by women who are in need of abortion services is essential to determining the constitutionality of HB2, as the legal thresholds for abortion restrictions center upon the magnitude and nature of these burdens on women.10 However, such an evaluation presents a number of methodological challenges. Documenting the experiences of women who were unable to obtain a wanted abortion because of insurmountable hardship is difficult, primarily because those are the very women who were unable to reach an abortion clinic where they might be enrolled in a study.11,12 Indeed, the 13% decline in abortions performed in Texas during the first 6 months after HB2 went into effect gives an indication of the law’s impact.3

In addition, HB2 affected women who were able to obtain an abortion. These women include those who were directly affected by the closure of the clinic they would have used, as well as women whose nearest or preferred clinic did not close, but who nevertheless were burdened by the law through discontinued offering of medication abortion, longer wait times for appointment availability, or higher costs of the procedure at one of the remaining facilities.

In this study, we assess the impact of HB2 on women who obtained an abortion after the law was implemented. With survey data collected from a sample of women who obtained an abortion in Texas in 2014, we compared the experiences of women whose nearest clinic closed with those of women whose nearest clinic remained open. Through this comparison, we sought to assess the additional burdens experienced by women whose nearest clinic closed.

METHODS

Between May and August 2014, we surveyed women seeking abortion services in Austin, Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio. At the time of data collection, the only open abortion clinics were located in 5 metropolitan statistical areas: Austin, Dallas/Fort Worth, El Paso, Houston, and San Antonio. We purposively sampled 10 abortion facilities to include both Planned Parenthood–affiliated clinics and independent providers that performed more than 1500 abortions in 2013 and provided procedures up to a gestational age of at least 14 weeks from last menstrual period.3 At the time of data collection, the open clinic in El Paso did not meet these inclusion criteria. Between January and April 2014, these study sites provided 63% of procedures performed in all Texas abortion facilities open at the beginning of the data collection period. The 4 metropolitan statistical areas in which we recruited accounted for 95% of the total population for all 5 metropolitan statistical areas with open clinics.

A project coordinator recruited participants at each site for 3 to 6 days, depending on clinic schedule and volume. In 9 of the 10 facilities, every woman in the clinic waiting room was invited to participate in the survey. At 1 facility, clinic staff invited women to participate following their initial consult and interested women were directed to the project coordinator. Women were eligible to participate if they were seeking an abortion at one of the facilities in our study, were aged 18 years or older, spoke English or Spanish, and had completed their pre-abortion ultrasound consultation. Eligible participants could complete the survey at consultation, procedure, or follow-up visits. Participants reviewed and signed a consent form, and received instructions on how to use an iPad before completing the self-administered survey. The survey items were adapted from a previous study with Texas abortion clients and used a health care access framework to assess women’s experiences obtaining abortion care. In addition to questions on sociodemographic characteristics, reproductive history, and current pregnancy, the survey focused on several dimensions of access to abortion care, including accessibility (distance to clinics), availability (wait times for services, type of procedures offered), and affordability (out-of-pocket costs).13,14 For the purpose of determining distance traveled, we obtained zip code of residence. The survey was pretested and professionally translated into Spanish. After completing the 15-minute survey, participants received a $20 gift card.

Measures

For our analyses, we distinguished between participants whose nearest in-state abortion facility closed following the introduction of HB2 and those whose nearest facility remained open. For all clinics providing abortion care in the state, open or closed status had been previously documented through interviews conducted with clinic staff, reports in the press, and mystery-client calls to abortion facilities.3 We used 2 benchmark dates to assess the change in open facilities providing abortion services before and after HB2: April 2013, before the Texas legislature’s debate of HB2, and July 2014, the midpoint of study data collection. We used the clinics’ physical addresses and the participants’ zip codes of residence to determine the distance to each participant’s nearest open in-state clinic in April 2013 and distance to nearest open in-state clinic in July 2014; we also calculated the distance to the clinic where the participant was interviewed while seeking abortion care. Distance was estimated as the number of road miles from women’s zip codes of residence to each clinic using Traveltime3, a Stata program that accesses the Google Maps Distance Matrix Application Programming Interface to calculate number of miles by road between 2 geographic points (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). 15

We calculated mean and median values for each of the 3 distance measures for the whole sample, as well as for women whose nearest clinic in 2013 remained open, and for women whose nearest clinic had closed, by July 2014. We also calculated the percentile distribution of distance traveled to the clinic where women were interviewed for the nearest-clinic-open and nearest-clinic-closed groups. We performed t tests to assess differences between these groups.

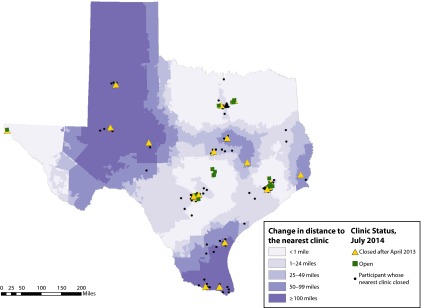

We also examined the geographical distribution of the increase in distance to the nearest clinic in 2014 because this was unlikely to be evenly distributed across the state. For all Texas zip codes, we computed the change in the distance to the nearest in-state clinic between April 2013 and July 2014, which we categorized as less than 1 mile, 1 to 24 miles, 25 to 49 miles, 50 to 99 miles, and 100 miles or more. We also plotted the zip code centroid for each survey participant whose nearest clinic closed between April 2013 and July 2014, as well as the location of the open and closed clinics.

In addition to distance traveled, we identified 4 burdens on access to abortion care that a woman might have experienced: (1) high out-of-pocket costs, (2) an overnight stay, (3) a delay in getting an abortion appointment, and (4) not obtaining her preferred type of abortion. For the first indicator, we aggregated self-reported out-of-pocket costs associated with getting to the clinic but not directly associated with the consultation or procedure visits (i.e., lost wages because of missing days of work, childcare or elder-care arrangements, transportation, and overnight costs).

Participants who spent more than $100 out of pocket were classified as having high out-of-pocket costs. Women who reported staying or planning to stay overnight because of the abortion were classified as having an overnight stay. Participants who answered “yes” to the question “I scheduled my appointment later than I would have liked” were classified as having a delayed appointment. Participants who reported a preference for medication abortion before seeking care but who received or expected to receive an aspiration abortion were classified as having frustrated demand for medication abortion, as we hypothesized that complying with the 4 required visits would likely impose less hardship if a clinic were within close proximity to a participant’s home. Finally, women who traveled more than 50 miles (20 miles more than the national average of 30 miles16) from their homes to their abortion clinic were classified as having traveled a far distance.

We then constructed a summary measure of the total number of hardships a woman had experienced. A second summary indicator capturing the participant’s own perception of burden came from the survey question: “Thinking about the time and travel related to your visit today, how easy or hard was it to come to the clinic for this visit?” The response categories were “very easy,” “somewhat easy,” “somewhat hard,” and “very hard.” The final indicator of hardship was the gestational age at the time of the clinic visit based on ultrasound (as reported by the participant). We hypothesized that women facing more obstacles to care would present later in pregnancy.

Experiences When Nearest Clinic Closed vs Remained Open

Before we compared measures of hardship between the nearest-clinic-open and nearest-clinic-closed groups, we compared women according to their social and demographic characteristics as the potential existed for systematic differences between participants whose nearest clinic closed and those whose nearest clinic remained open after HB2. The individual and household characteristics available in the survey included age, parity, race/ethnicity, language, educational attainment, poverty level, student status, relationship status, and whether the participant had had a previous abortion.

We examined the distributions in each group, and tested for differences by using Pearson χ2 statistics and 2 sample tests of proportions. However, even when no statistical difference exists between groups in observable characteristics, there may be confounding. For example, poor women may have been more likely to have had difficulty getting to a clinic and also more likely to live in areas where clinics closed. Alternatively, among women living in areas where clinics closed, perhaps only those with higher incomes and education were able to obtain abortion services at a more distant clinic. To select an internally valid comparison group for women whose nearest clinic closed after HB2,17,18 we employed an inverse-probability-weighted regression adjustment approach to balance observed covariates across the nearest-clinic-open and nearest-clinic-closed groups.19

We generated propensity scores to construct the regression weights; although the propensity score is often defined as the conditional probability of receiving a treatment or exposure, it also can be applied to other characteristics of a sample. In this case, we entered all of the available covariates including distance to the nearest clinic open in 2013 linearly into a probit model estimating the conditional probability that a woman’s nearest clinic closed. As a check on the properties of the estimated propensity scores, we reviewed the overlap and density profiles of the propensity scores across the nearest-clinic-closed and nearest-clinic-open groups. We then performed the inverse probability-weighted regression adjustment of the mean outcomes across groups, and estimated the average treatment effect on the treated—the mean impact of the closing of clinics on those who were affected by the closure. This procedure enjoys the formal property of being “doubly robust” in the sense that the estimated effect remains asymptotically unbiased even if the propensity score model or the outcome model (but not both) is misspecified.19–21

We compared the nearest-clinic-open and nearest-clinic-closed groups with respect to the individual measures of hardship, as well the 3 summary measures, by using χ2 and Wilcoxon rank sum tests as appropriate. We then estimated the average treatment effect on the treated for the individual and summary measures. All analyses were performed with Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX); the map of distance traveled was created by using ArcGIS 10.3 (Esri, Redlands, CA).

RESULTS

Overall, 439 women completed the survey. We were unable to calculate a response rate for the facility where staff recruited participants (n = 57). At the other 9 sites, 624 women were invited; 64 were ineligible, primarily because of age or not yet having completed the ultrasound, and 170 declined to participate. The primary reasons for declining were lack of time or interest. At these 9 sites, 68% of eligible women participated (n = 382). We excluded women whose zip code was not provided or was unidentifiable (n = 39) and non–Texas residents (n = 2) from analysis, resulting in a final sample of 398. For 151 participants (38%), the nearest in-state abortion clinic to their zip code of residence that was open in 2013 had closed when they sought an abortion in 2014. The distribution of participants according to selected sociodemographic characteristics is shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the distributions of any of these variables between participants whose nearest clinic had closed and those whose nearest clinic remained open. Although more than 20% of respondents did not answer survey items regarding household income and size, the proportion missing did not differ between groups and was included in later modeling.

TABLE 1—

Sociodemographics of Texas-Resident Women Seeking Abortions in 10 Abortion Facilities: Texas, 2014

| Variables | Total Population (n = 398), No. (%) | Women Whose Nearest Clinic in 2013 Was Open in 2014 (n = 247), No. (%) | Women Whose Nearest Clinic in 2013 Was Closed in 2014 (n = 151), No. (%) | P |

| Age, y (n = 397) | .41 | |||

| 18–24 | 177 (44.6) | 108 (43.9) | 69 (45.7) | |

| 25–35 | 188 (47.4) | 115 (46.7) | 73 (48.3) | |

| > 35 | 32 (8.1) | 23 (9.3) | 9 (6.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity (n = 395) | .40 | |||

| Black or African American | 75 (19.0) | 47 (19.3) | 28 (18.5) | |

| White | 118 (29.9) | 79 (32.4) | 39 (25.8) | |

| Latina or Hispanic | 163 (41.3) | 93 (38.1) | 70 (46.4) | |

| Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, or other race | 16 (4.1) | 11 (4.5) | 5 (3.3) | |

| ≥ 2 races/ethnicities | 23 (5.8) | 14 (5.7) | 9 (6.0) | |

| Education (n = 392) | .46 | |||

| High school or less | 127 (32.4) | 74 (30.3) | 53 (35.8) | |

| Some college | 171 (43.6) | 106 (43.4) | 65 (43.9) | |

| College graduate or higher | 94 (24.0) | 64 (26.2) | 30 (20.3) | |

| Current student (n = 396) | 133 (33.6) | 83 (33.7) | 50 (33.1) | .94 |

| Relationship status (n = 398) | .60 | |||

| Single | 137 (34.4) | 84 (34.0) | 53 (35.1) | |

| Relationship, not living together | 104 (26.1) | 70 (28.3) | 34 (22.5) | |

| Living together | 74 (18.6) | 41 (16.6) | 33 (21.9) | |

| Married | 60 (15.1) | 37 (15.0) | 23 (15.2) | |

| Separated or divorced | 23 (5.8) | 15 (6.1) | 8 (5.3) | |

| Primary language spoken at home (n = 392) | .79 | |||

| English | 319 (81.4) | 197 (80.7) | 122 (82.4) | |

| Spanish | 19 (4.8) | 14 (5.7) | 5 (3.4) | |

| Both English and Spanish | 50 (12.8) | 31 (12.7) | 19 (12.8) | |

| Another language | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.4) | |

| 200% FPG (n = 305) | .49 | |||

| ≤ 200% | 175 (44.3) | 114 (59.1) | 61 (54.5) | |

| > 200% | 130 (32.9) | 79 (40.9) | 51 (45.5) | |

| Parity (n = 362) | .17 | |||

| 0 | 153 (42.3) | 105 (46.5) | 48 (35.3) | |

| 1 | 80 (22.1) | 48 (21.2) | 32 (23.5) | |

| 2 | 73 (20.2) | 37 (16.4) | 36 (26.5) | |

| ≥ 3 | 56 (15.5) | 36 (15.9) | 20 (14.7) | |

| Previous abortion (n = 380) | 145 (38.2) | 88 (37.1) | 57 (39.9) | .28 |

Note. FPG = federal poverty guidelines. Includes women who reported their zip code and who lived in Texas at the time of the survey.

Clinic Closures and Distance to Clinics

In 2013, before HB2, the average distance to the nearest abortion provider among all participants was 15 miles, with no significant difference between women whose nearest clinic remained open and women whose nearest clinic eventually closed (Table 2). The average distance to the nearest abortion facility increased by 20 miles between April 2013 and July 2014, a change that was attributable entirely to an increase in distance (on average 53 miles) to the nearest clinic among participants whose nearest clinic closed after HB2. Among all participants, the mean one-way distance that women actually traveled to the clinic where they obtained an abortion was 46 miles (range = 1 to 381 miles). For women whose nearest clinic closed, the mean 1-way distance traveled was 85 miles (median = 35), compared with 22 miles (median = 15) for women whose nearest clinic did not close (P ≤ .001). In the nearest-clinic-closed group, large differences in distance occurred above the median, as indicated by the 75th and 90th percentiles (139 and 256 miles, respectively).

TABLE 2—

Distance Lived From Nearest Abortion Clinic and Distance Traveled to Abortion Clinic, in Miles, for Texas-Resident Women Seeking Abortions in 10 Abortion Facilities, Texas, 2014

| Variable | Total Population (n = 398), Miles, Mean (SD) | Women Whose Nearest Clinic in 2013 Was Open in 2014 (n = 247), Miles, Mean (SD) | Women Whose Nearest Clinic in 2013 Was Closed in 2014 (n = 151), Miles, Mean (SD) | P |

| Distance from residence zip code to nearest clinic in 2013 | 15.0 (17.9) | 13.7 (16.7) | 17.1 (19.5) | .07 |

| Distance from residence zip code to nearest clinic in 2014 | 35.0 (60.8) | 13.7 (16.7) | 69.9 (85.7) | < .001 |

| Distance from residence zip code to facility where recruited | ||||

| Mean | 46.2 (70.5) | 22.3 (28.1) | 85.1 (96.9) | < .001 |

| Range | 1–381 | 1–214 | 4–381 | |

| Distance to facility by percentiles | ||||

| 10th | 4.6 | 3.4 | 11.5 | . . . |

| 25th | 10.3 | 7.8 | 18.5 | . . . |

| 50th | 19.6 | 15.4 | 34.6 | . . . |

| 75th | 39.7 | 24.9 | 139.1 | . . . |

| 90th | 143.4 | 42.1 | 256.3 | . . . |

Note. Ellipses indicate that calculations were not applicable for these values.

Figure 1 shows how the increase in distance brought about by clinic closures was distributed throughout the state. Some respondents, especially those in South and West Texas, and the Panhandle, experienced a substantial increase in distance because of proximity to a clinic in 2013, but living much farther from an open clinic in 2014. Others experienced a smaller increase in distance because the nearest clinic that closed after HB2 was only marginally closer than the nearest open clinic in 2014. This was frequently the case for respondents living in the central, northern, and eastern parts of the state.

FIGURE 1—

Change in Travel Distance to the Nearest Texas Clinic Offering Abortion, 2013–2014

Hardships Experienced in Obtaining an Abortion

Before adjustment, the proportion of women having to travel more than 50 miles, stay overnight, and incur out-of-pocket expenses in excess of $100 were significantly greater in the nearest-clinic-closed group (Table 3). There was also a greater proportion experiencing frustrated demand for a medication abortion. There was no significant difference in the proportion of women who reported that they scheduled their appointment later than they preferred.

TABLE 3—

Measures of Hardship in Accessing Abortion Clinic Services Among Texas-Resident Women Seeking Abortions in 10 Abortion Facilities, Before and After Inverse-Probability-Weighted Regression Adjustment, Texas, 2014

| Before IPWRA |

After IPWRA |

||||||

| Variable | Women Whose Nearest Clinic in 2013 Was Open in 2014 (n = 247), % | Women Whose Nearest Clinic in 2013 Was Closed in 2014 (n = 151), % | P | Women Whose Nearest Clinic in 2013 Was Open in 2014 (n = 247), % | Women Whose Nearest Clinic in 2013 Was Closed in 2014 (n = 151), % | Average Treatment Effect on the Treated, % or Mean | P |

| Measures of hardship | |||||||

| Traveled > 50 miles | 8.1 | 44.4 | < .001 | 9.6 | 43.8 | 32.6 | < .001 |

| Stayed overnight | 3.2 | 15.9 | < .001 | 5.1 | 16.0 | 8.3 | .07 |

| Out-of-pocket expenses > $100 | 20.2 | 29.8 | .03 | 19.7 | 31.9 | 10.3 | .04 |

| Frustrated demand for medication abortion | 22.3 | 33.1 | .02 | 21.8 | 36.8 | 14.3 | .003 |

| Scheduled appointment later than preferred | 45.7 | 44.4 | .79 | 45.4 | 45.7 | 0.0 | .94 |

| Summary measures | |||||||

| Hardship score | < .001 | ||||||

| 0 | 35.6 | 23.2 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| 1 | 43.3 | 30.5 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| 2 | 17.0 | 23.8 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| 3 | 4.1 | 13.3 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| 4 | 0.0 | 5.3 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| 5 | 0.0 | 4.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| Mean | 0.9 | 1.6 | < .001 | 0.90 | 1.67 | 0.72 | < .001 |

| Perceived difficulty accessing abortion care | < .001 | ||||||

| Very easy | 45.5 | 32.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| Somewhat easy | 38.5 | 30.7 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| Somewhat hard | 11.5 | 28.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| Very hard | 4.5 | 9.3 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| Somewhat or very hard | 16.0 | 37.3 | < .001 | 18.0 | 35.9 | 19.0 | < .001 |

| Gestation at ultrasound, wk | .08 | ||||||

| < 7 | 42.5 | 34.4 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| 7–9 | 33.5 | 35.8 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| 10–11 | 13.9 | 15.2 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| ≥ 12 | 10.2 | 14.6 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| ≥ 10 | 24.1 | 29.8 | .20 | 26.4 | 30.2 | 1.1 | .83 |

Note. IPWRA = inverse-probability-weighted regression adjustment. Ellipses indicate that calculations were not applicable for these values.

The distribution of the aggregate number of hardships each woman experienced differed between the 2 groups, with 24% of women in the nearest-clinic-closed group experiencing 3 or more hardships versus 4% in the nearest-clinic-open group. The mean number of hardships experienced also differed between the 2 groups. Similarly, the 2 groups differed in their perception of difficulty accessing abortion care, with 37% in the nearest-clinic-closed group and 16% in the nearest-clinic-open group stating that this was somewhat or very hard. Finally, in both groups, the majority of participants were either less than 7 weeks pregnant or between 7 and 9 weeks at their ultrasound appointment. A larger proportion of women whose nearest clinic closed had gestations of 10 weeks or more compared with those whose nearest clinic remained open, but the difference was only marginally significant.

The inverse-probability-weighted regression-adjusted estimates of most of these parameters are similar to the estimates before correction. The only notable changes are the slightly smaller difference in the proportion staying overnight and the slightly larger estimate of the difference in the proportion experiencing frustrated demand for medication abortion. The trend toward a difference in gestational age between the 2 groups lost significance after adjustment.

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate a substantial additional travel burden experienced by women seeking abortion who live in areas of Texas where clinics closed after HB2 compared with those living in areas where clinics remained open. For women in our study whose nearest abortion clinic closed after HB2, the average distance to the nearest abortion provider increased 4-fold, and for 44% of this group, the new distance exceeded 50 miles. The distance women traveled to obtain their abortion was also 4 times greater among women whose nearest clinic closed compared with the distance traveled by women whose nearest clinic remained open, and nearly 3 times the average distance (30 miles) traveled in a 2008 national survey of women seeking abortion.16 In addition, both before and after inverse-probability-weighted regression adjustment, women whose nearest clinic closed had a higher probability of experiencing hardship, measured in multiple ways, than women whose nearest clinic remained open.

The only dimension of hardship in which there was no significant difference between the 2 groups was the gestational age at which women were able to receive abortion care. This is somewhat inconsistent with our previous research documenting a small but significant increase in the proportion of abortions performed after 12 weeks in the first 6 months after HB2 implementation.3 The finding here may be because we are underpowered for this outcome; alternatively, it may be because increases in wait times to get an appointment affected women regardless of whether their nearest clinic closed. The information we have on wait times suggests that they increased at some clinics, and varied over time at individual clinics, sometimes in reaction to the suspension of services at neighboring clinics.22

These results provide a partial estimate of the burdens imposed on women by the clinic closures that followed the introduction and implementation of HB2, and extend previous research on the impact of TRAP laws, most of which has relied on projected or hypothetical analyses of the increases in distance that would result from anticipated, rather than actual, clinic closures.3,23 The one previous study that estimated impact on travel distance and costs pertained to Texas’s 2003 law requiring that procedures at or after 16 weeks’ gestation be performed in an ASC or hospital.5 In that analysis, the authors documented the postlaw increase in Texas residents traveling out of state for abortion procedures at or after 16 weeks’ gestation, and calculated the increase in population-weighted average distance, for women of reproductive age, to the nearest provider of abortions at or after 16 weeks’ gestation. In comparison, our analysis used individual-level data to calculate increases in distance to the nearest provider among women seeking abortions.

Limitations and Strengths

This study has several limitations, the most important of which is that it cannot provide a basis for estimating the number of women for whom the additional burdens imposed by HB2 were sufficiently great to prevent them from accessing an abortion that they would have sought in the absence of clinic closures and other restrictions. Other research has documented cases of Texas women who were prevented from obtaining desired abortions because of the closure of nearby clinics as a result of HB2.4 In addition, recruitment sites were not selected at random, and our sample is not representative of women seeking abortion care in Texas after HB2. Moreover, our sample does not include Texas residents who may have traveled out of state for abortion care, sought abortions in Mexico, or successfully self-induced abortion after HB2 was enforced.23,24 Finally, our specific hardship measures do not fully capture the burden experienced by some women. For example, women who could not afford an overnight stay may have opted to travel in the middle of the night to reach a facility and return home the same day.

A strength of this study is that we surveyed women obtaining abortion services more than 6 months after the enforcement of HB2, minimizing the possibility that our findings are solely attributable to the confusion of sudden or acute changes in services. Also, in our sample, the women whose nearest clinic closed were similar to those whose nearest clinic remained open, and the statistical procedures we employed to adjust for possible confounding achieved a remarkable balance in the observed characteristics of the 2 groups.

Public Health Implications

In a large state, closures of abortion clinics following the implementation of a TRAP law can impose a substantial burden on women seeking abortion care by making them travel farther, making them spend more time and money, and causing them to undergo a different kind of procedure from the one they prefer. These burdens are in addition to any increase in wait times or costs that may be spread evenly over all women seeking abortion care and those that result in making legal abortion an unattainable option for some women.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, as well as a center grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5 R24 HD042849) awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

We thank Naomi Caballero for her assistance with data collection.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Texas at Austin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guttmacher Institute. Laws affecting reproductive health and rights: state trends at midyear, 2015. News in context. Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/media/inthenews/2015/07/01. Accessed November 23, 2015.

- 2.Texas 83rd State Legislature. Bill Text: Texas HB No. 2. 2013. Available at: https://legiscan.com/TX/text/HB2/id/870667. Accessed November 23, 2015.

- 3.Grossman D, Baum S, Fuentes L et al. Change in abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. Contraception. 2014;90(5):496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuentes L, Lebenkoff S, White K et al. Women’s experiences seeking abortion care shortly after the closure of clinics due to a restrictive law in Texas. Contraception. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.017. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colman S, Joyce T. Regulating abortion: impact on patients and providers in Texas. J Policy Anal Manage. 2011;30(4):775–797. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts SC, Gould H, Upadhyay UD. Implications of Georgia’s 20-week abortion ban. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e77–e82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biggs MA, Neuhaus JM, Foster DG. Mental health diagnoses 3 years after receiving or being denied an abortion in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2557–2563. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerdts C, Dobkin L, Foster DG, Schwarz EB. Side effects, physical health consequences, and mortality associated with abortion and birth after an unwanted pregnancy. Womens Health Issues. 2016;26(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts SC, Biggs MA, Chibber KS, Gould H, Rocca CH, Foster DG. Risk of violence from the man involved in the pregnancy after receiving or being denied an abortion. BMC Med. 2014;12:144. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson JA. Science disputes in abortion law. Tex Law Rev. 2015;93(7):1849–1883. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossier C. Estimating induced abortion rates: a review. Stud Fam Plann. 2003;34(2):87–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerdts C, DePineres T, Hajri S et al. Denial of abortion in legal settings. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41(3):161–163. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-100999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127–140. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones RK, Upadhyay UD, Weitz TA. At what cost? Payment for abortion care by US women. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(3):e173–e178. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Google Maps Distance Matrix API. Available at: https://developers.google.com/maps/documentation/distance-matrix/intro. Accessed November 23, 2015.

- 16.Jones RK, Jerman J. How far did US women travel for abortion services in 2008? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(8):706–713. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunning T. Natural Experiments in the Social Sciences a Design-Based Approach. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekhon JS, Titiunik R. When natural experiments are neither natural nor experiments. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2012;106(1):35–57. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Causal Inference for Statistics, Social and Biomedical Sciences: An Introduction. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robins JM, Ritov Y. Toward a curse of dimensionality appropriate (CODA) asymptotic theory for semi-parametric models. Stat Med. 1997;16(1-3):285–319. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970215)16:3<285::aid-sim535>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woolridge J. Economentric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Texas Policy Evaluation Project. Abortion wait times in Texas: the shrinking capacity of facilities and the potential impact of closing non-ASC clinics. 2015. Available at: http://sites.utexas.edu/txpep/files/2016/01/Abortion_Wait_Time_Brief.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2016.

- 23.Roberts SC, Fuentes L, Kriz R, Williams V, Upadhyay UD. Implications for women of Louisiana’s law requiring abortion providers to have hospital admitting privileges. Contraception. 2015;91(5):368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grossman D, Holt K, Pena M et al. Self-induction of abortion among women in the United States. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18(36):136–146. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]