Abstract

Several studies have implicated the sexual networks of Black men who have sex with men (MSM) as facilitating disproportionally high rates of new HIV infections within this community. Although structural disparities place these networks at heightened risk for infection, HIV prevention science continues to describe networks as the cause for HIV disparities, rather than an effect of structures that pattern infection. We explore the historical relationship between public health and Black MSM, arguing that the current articulation of Black MSM networks is too often incomplete and counterproductive. Public health can offer a counternarrative that reconciles epidemiology with the social justice that informs our discipline, and that is required for an effective response to the epidemic among Black MSM.

Black men who have sex with men (MSM) make up between 20% and 25% of all new HIV infections in the United States,1 and have 3 times the odds of testing HIV positive compared with other MSM.2 (We acknowledge the limitations of the term “MSM” but use it to be inclusive of same-sex sexual behavior and gay, bisexual, or same-gender loving identities.3) The rate of new infections among young Black MSM is notably concerning; recent prospective cohort studies have reported annual incidence rates of between 5.9% and 12%.4–6 Although individual behaviors such as unprotected anal intercourse and substance use increase the likelihood of HIV infection, Black MSM are no more likely to engage in these behaviors than other MSM, perhaps even less so.7 Factors that explain individual HIV risk do not adequately explain racial disparities in HIV infection. However, HIV-positive Black MSM are less likely than MSM of other races/ethnicities to achieve viral suppression.2 This disparity is attributable to a variety of structural factors, including lower income, reduced likelihood of having health insurance, medical mistrust, and experiences of stigma in the health care setting.8,9 Barriers in maintaining a detectable viral load not only harm the health of individual HIV-positive Black MSM but also limit their ability to take advantage of Treatment as Prevention, which can prevent additional HIV infection within sexual networks.10–12

Although it is not our intention to limit the concerns of Black MSM to the HIV epidemic—these men face myriad other challenges as well—the high incidence and prevalence of HIV infection does have enormous impact on these communities. As public health researchers, we must acknowledge our ability to affect Black MSM communities through our discourse about HIV. Although the scientific discussion of the sexual networks of Black MSM represents a useful step forward from undue focus on individual sexual risk behavior to explain disparities, it comes with a unique set of consequences that must be challenged if we are to avoid causing unintended harm. In his seminal 1986 essay “Brother to Brother: Words From the Heart,” Black gay author and activist Joseph Beam famously wrote, “Black men loving Black men is the revolutionary act.”13(p240) Invoking this spirit, and the spirit of other Black gay male activists, we aim to critique public health discourse concerning sexual networks as a facilitator of the HIV epidemic among Black MSM, discuss its consequences for HIV prevention, and offer ways forward as we promote the health of all Black MSM.

RESEARCH FINDINGS AROUND BLACK MSM SEXUAL NETWORKS

“Whom did he love? It makes a difference.”14

—Essex Hemphill, poet and essayist (1957–1995)

Millett et al. conducted a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors and found no difference in individual sexual behavior between Black MSM and other MSM,7 prompting a renewed search for factors sustaining the marked disparity in HIV incidence and prevalence. Several explanations have been offered, largely revolving around the ability of HIV-positive Black MSM to navigate the HIV care continuum, achieve viral suppression, and limit transmission to their sexual partners.11 Black MSM are more likely than men of other racial groups to have sex with men of their same race.15–18 Although consensus about what drives these dense intraracial networks has yet to be established,18–20 racial homophily in the sexual networks of Black MSM does mean that as infections increase within a comparatively smaller but more interconnected group, new infections readily propagate throughout the network.21

A 2006 systematic review of the literature examined the level of support for 12 separate hypotheses explaining the racial disparities in HIV infection among Black MSM.22 Of relevance to our discussion are 2 related hypotheses. The authors concluded at the time that there was not sufficient evidence to support the hypotheses that “Black MSM are more likely than other MSM to have sex with partners known to be HIV positive” and that “The sexual networks of Black MSM place them at greater risk for HIV infection than the sexual networks of other MSM.” Almost a decade later, many have provided empirical support for racial homophily among Black MSM.15–17,23–26 Although studies differ in their operationalization of how homophily among Black MSM facilitates HIV infection within sexual networks, they essentially communicate 1 primary mechanism: even if one assumes parity in sexual risk behaviors, HIV-negative Black MSM are at increased risk for infection because they have more partners who are Black MSM, who in turn are more likely to be HIV positive. For brevity, we hereafter refer to those lines of inquiry related to this mechanism as the “network hypothesis.”

CONTEXTUALIZING THE DISCUSSION

“The place in which I’ll fit will not exist until I make it.”27

—James Baldwin, author and poet (1924–1987)

The studies exploring the network hypothesis and the consistency of results have since made their way into more widely consumed popular sources of information. Media reports from the 2014 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections highlighted a large study of prospective HIV incidence among MSM in Atlanta that provided strong support for the network hypothesis.28 In the same year, the Washington Post brought the network hypothesis to the attention of a broader audience.29 Although these findings and their subsequent mass media dissemination are important, a more layered discussion of these dynamics is necessary. Otherwise, our understanding of the epidemic merely reassigns pathology from individual Black MSM to communities of Black MSM.

The network hypothesis takes into account individual behaviors such as consistent condom use or preexposure prophylaxis in HIV prevention efforts.30 It represents a useful step forward because the public health perspective requires that our questions go beyond what facilitates risk of individual HIV infection to determine what patterns rates of HIV infection.31 Arguably, the meta-analysis from Millett et al. established consensus that not only was individual sexual risk behavior not higher among Black MSM, but it could not explain the racial disparity in the HIV epidemic among MSM.7 Accordingly, this fueled the pursuit of the elusive factors that were responsible. Although it is difficult to identify a tipping point regarding the proliferation of the network hypothesis, an explosion of peer-reviewed publications, many of which we have cited, are evidence that it has occurred.

But what makes the network hypothesis so appealing? First, the idea behind the hypothesis makes intuitive sense, and it has demonstrated utility in explaining other infectious disease epidemics.21 Second, although formal studies of networks and their corresponding analysis remain time and resource intensive, they can be easily approximated through cross-sectional egocentric studies of partner characteristics, although there are notable exceptions in which researchers examine network-level variables.32 Finally, the network hypothesis represents a palatable shift from blaming individual behaviors (i.e., condom use) of Black MSM for disparities in HIV incidence by implicating an extraindividual factor. The blame remains on individual Black MSM, though; it has simply been relocated from decisions about condom use onto decisions about having sex with one another.

THE PROBLEM WITH PROBLEMATIZING BLACK MSM NETWORKS

“It’s necessary to constantly remind ourselves that we are not an abomination.”33

—Marlon Riggs, filmmaker and educator (1957–1994)

Public health scientists have been rightly eager to explain the seeming contradiction between relatively lower levels of individual Black MSM sexual risk behaviors and increased risk of HIV infection. Interventions addressing root sources of disparities require this information. Pathologizing Black MSM sexual networks does not appear to be a result of deliberate intention, but rather an unintended consequence of the popularity of the network hypothesis itself. Other studies that sought to understand and ameliorate health disparities were used to stigmatize populations as well. For example, a study that documented the relationship between sexual orientation and health risk behaviors was subsequently used to implicate sexual minority status itself as the causal factor.34,35 Similarly, an epidemiological modeling exercise to illustrate how the HIV epidemic among gay men reduced potential years of life was used as evidence that gay men live an unhealthy “lifestyle.”36,37 Even absent malicious intent, in an age when people increasingly consume information via their online social networks,38 nuance presented in journal articles is distilled to a headline that can easily result in misinterpretation. Although the network hypothesis may be intended as useful shorthand for public health scientists to communicate the limitations of employing individual-level factors as a means to understand and end disparities, we must seize the opportunity to develop and articulate a comprehensive mechanism that appropriately situates the role of Black MSM sexual networks. Failure to do so runs the risk of this literature falling prey to a misinterpretation, in which the manifestation of disparities becomes synonymous with their origins rather than their root causes. Black MSM networks do not function as the causal agent in producing health disparities, but are better seen as a proxy for structural disparities that create and maintain infections to begin with.

Another danger of the uncritical application of the network hypothesis is how readily it communicates to MSM that they should avoid romantic and sexual intimacy with Black MSM if they want to remain healthy. The prevalent and potent racism within gay communities is well-documented and certainly predates the network hypothesis.39–42 However, the two are not unrelated. Both qualitative and quantitative studies have shown that much of what drives racial homophily among Black MSM has to do with a “hierarchy” in which Whiteness is actively prized and Blackness is actively devalued.18,19,43 Our concern is that the network hypothesis unwittingly exacerbates racism in partnership dynamics, increasing existing harmful influences of racism on the health and health behaviors of Black MSM.9,43–47 For example, exposure to racism is negatively associated with HIV testing and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. And although there remains no difference between Black and other MSM in rates of condomless sex, among Black MSM, racism is negatively associated with condom use. It is beyond the scope of this article to review the many mechanisms through which racism influences the health of Black MSM; however, others have engaged in this analysis,44,45,48 adding to an impressive body of theoretical and empirical literature that extends to other populations across the United States.9

Lest the pendulum swing too far in the other direction, however, we strongly caution against the equally problematic assumption that absent these pathologizing influences, Black MSM would not choose to partner with one another. Relationships between Black MSM should be celebrated and not viewed as a “consolation prize” resulting from constraints of partner selection imposed by others.18,19 Although they occupy a relatively small space in the peer-reviewed research literature, some studies have challenged many of the common stereotypes associated with Black male—and specifically Black MSM—sexuality.49,50 Acknowledging the reality of healthy relationships between Black men is likely why campaigns such as New York City’s “I Love My Boo,” which depicts asset-based and normative relationships, have been so positively received.51,52

THE TRANSLATION FROM SCIENCE TO POPULAR DISCOURSE

“When an individual is protesting society’s refusal to acknowledge his dignity as a human being, his very act of protest confers dignity on him.”53

—Bayard Rustin, civil rights strategist and pacifist (1912–1987)

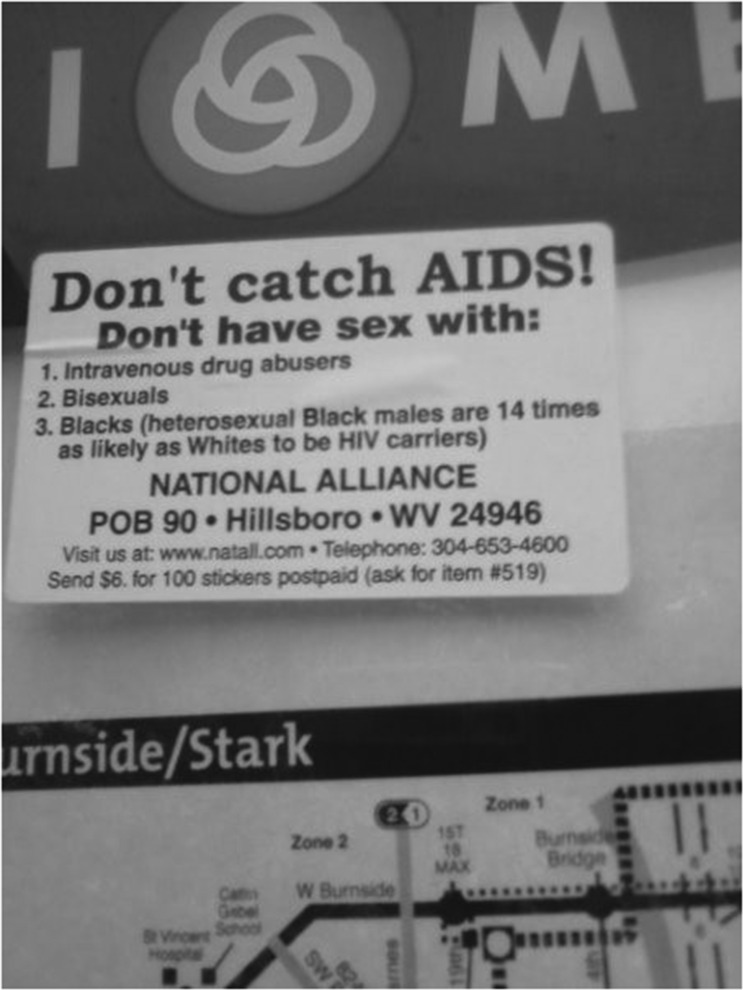

Public health has unwittingly interfered with the autonomy of all MSM to select their partners under the specter of HIV risk reduction, in turn reinforcing the very structures that led to heightened HIV prevalence among Black MSM to begin with. In the 1990s the National Alliance, a White nationalist organization, notoriously perverted the epidemiology of the HIV epidemic to reinforce their organization’s preexisting prejudice.54 Although it is easy to dismiss this as an extreme example, it is contingent upon us in public health to be more explicit about what our data do and do not say, and anticipate their misapplication. As seen in Figure 1, the ease with which a legacy of misinformation and stigma can persist should prove a cautionary tale. In retrospect, it is easy to critique the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for naming homosexuals, heroin users, hemophiliacs, and Haitians as themselves risk factors for HIV infection rather than groups at risk, leading to the infamous and stigmatizing coining of HIV as “the 4H disease.”55 But if our conclusion today remains that Black MSM experience heightened HIV incidence because they have sex with other Black MSM, how far have we truly come?

FIGURE 1—

A National Alliance Sticker Visible on Portland, OR, Public Transportation in 2009 That Usurps the Language of HIV Prevention

Source. qPDX.com; photo credit: Keller Henry.

Contemporary manifestations of this discourse are easily seen surrounding the search for the “Black bisexual bridge,” the pathway through which Black women are infected with HIV from male partners who became infected through clandestine sex with other men. Related discussions of the “Down Low,” and its selectively pejorative application to Black men who have sex with both men and women, is a notably problematic example.56–58 These labels have direct implications for the network hypothesis, as Black MSM are once again reduced to disease vectors.

The challenge before us now is how we in public health think about and employ language around sexual networks that both maintains scientific utility and values the lived experiences of Black MSM. Although in this article we have focused largely on those elements unique to the network hypothesis and the HIV epidemic among Black MSM, the issues we raise about the links between racism and health, as well as the role of science to address health inequities, are not confined to this 1 public health issue. Rather, the robust role of discrimination in producing and sustaining disparities—though certainly evident in the HIV epidemic—has implications for a variety of health disparities that span an assortment of populations and health outcomes. In the next section, we discuss how—through science, presentation of results, and necessary policies and interventions—public health professionals can employ a greater consciousness of Black MSM networks, keeping in mind that this exercise is useful for all those committed to the elimination of unjust differences in health.

PUBLIC HEALTH ACTION WE CAN TAKE NOW

“I tire so of hearing people say, let things take their course. Tomorrow is another day. I do not need my freedom when I’m dead. I cannot live on tomorrow’s bread.”59(p200)

—Langston Hughes, poet and novelist (1902–1967)

It is worth repeating that our goal is not to outright dismiss the network hypothesis nor to stifle scientific inquiry—we need more, not less, examination into the factors that place entire communities of Black MSM at risk for infection. Even though individual investigators or studies rarely chart the way forward by themselves, we all have a responsibility to provide tangible and actionable intervention options with our research. The network hypothesis has left us wanting because it does not readily address a fundamental question: What does the applied discipline of public health do with this information?

One immediate response to this question lies in how we present our research to the scientific and broader community. Although it is not exhaustive, we provide a list of questions that we challenge scientists to think through when discussing their research of the network hypothesis, as well as accompanying suggestions for how research presentation might be reframed to minimize the issues we have raised (Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Our goal is for readers to take these general examples and apply them to their own work to illustrate ways in which the conceptualization, execution, language, and dissemination of their own research process are all subject to the issues raised in this article. We anticipate that readers may walk away in want of a more concrete to-do list to address these challenges. Yet that presumes that the problems and their solutions are confined to 1 specific step in the research process. Furthermore, although individually we can make important strides by challenging our own assumptions about the network hypothesis, ultimately, addressing its systemic effect on communities requires the commitment of the broader public health workforce. Finally, it must be acknowledged that Black MSM are not a monolithic community, so generalized approaches are ineffective. Leveraging the diversity that exists within this population can help boost the efficacy of existing interventions while informing innovative programs and policies.

Another challenging, but necessary, task is to rethink, expand, and rearticulate the role of networks in the causal pathway to disparities in HIV infection.60 Variables that lie within the causal pathway are frequently treated as targets of intervention, and so it raises the question, where do networks belong? We acknowledge the epidemiological role of racial homophily and networks in producing health disparities, but since they are immune to direct intervention to sever the link between race and risk of HIV infection, they too frequently function as distractions from the work that must be done. And with rates of HIV infection increasing among young Black MSM, we cannot afford to be distracted.

An application of the fundamental causes framework offered by Link and Phelan requires that we not simply acknowledge the epidemiological risk associated with networks, but that we ask what places networks at “risk of risks.”61 Seen in this light, sexual networks are not the cause of racial disparities in HIV infection; they are the effect of those fundamental causes that create racial disparities in HIV infection. Although the HIV prevention literature frequently documents racial disparities, too rarely does it attribute those disparities to social adversities experienced by Black men of all sexual orientations. Factors such as neighborhood violence, poverty, incarceration, and racial discrimination are examples of contexts not unique to Black MSM, but that nevertheless influence their health and well-being.62,63 We highlight a modified version of the social-ecological framework that situates the role of networks alongside nonexhaustive examples of known drivers of infection for Black MSM—and possible solutions as well (Appendix B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).64 As Kraemer et al. suggest, the value of the network hypothesis is its ability to serve as a signpost to structural conditions that shape fundamental causes of disease.60 Its detriment is when it becomes our destination. The network hypothesis was born from a desire to move the field toward a more comprehensive understanding of mechanisms responsible for HIV disparities; we simply desire to continue this journey.

Beyond an examination of what public health can do with the network hypothesis is the more important consideration of its utility for Black MSM to promote the health of their communities. If we acknowledge the strength of these networks to spread infection, it is long past time to work with Black MSM in leveraging these networks in a meaningful way to spread health. As others have suggested, we would do well to push back against the fallacy of “hard to reach populations” and shift the onus onto public health as “hard to access.”65,66 This approach is not without challenge. As long as the primary available spaces for MSM to meet and socialize with one another are bars, clubs, and online sex-seeking Web sites, opportunities will be limited.

Acknowledging the value of structural intervention means that public health has a role in facilitating the ability of Black MSM communities to create and formalize spaces for themselves where they can thrive.31,61 Qualitative studies offer a useful window for public health scientists to understand the diverse reasons why Black MSM choose to love one another despite hearing a litany of negative messages about HIV, being a Black man, loving someone of the same sex, and combinations of all three. Indeed, Black MSM already have a high capacity as a community and for resilience. Given the vast amount of adverse social experiences Black MSM face, one might expect worse health profiles. Focusing on existing resiliency—at both the individual and community level—as a means to eliminate health disparities is community driven, efficient, and practical, and because these are the very strategies and structures that have been field tested, they are among the most likely to succeed among Black MSM.67,68

Even this approach, however, is but an ameliorating effort. Resiliency in the face of adversity is important, but it also places undue burden on those negatively affected by those very adversities. Acknowledging structural drivers such as income inequality, racism, and homophobia means that we have a responsibility to advocate for the elimination of these factors that place Black MSM at a greater risk of risks.69 And because these factors tend to cluster within the very networks that public health is already examining, the leap represents 1 way researchers can use the network hypothesis to evolve our understanding of the HIV epidemic.70,71

Finally, we have to be wary of research that pathologizes the sexual networks of Black MSM because it too easily dismisses their importance. In the United States, funding mechanisms, and associated research and intervention, are by design focused on individual outcomes.72 Yet this is counter to the very concept of how structures pattern health. The networks created by Black MSM are themselves a structure that exists in response to a host of social inequities. Moving forward, we have to prioritize those interventions and policies that realize that the HIV epidemic is but 1 star in a constellation of social inequalities that affect Black men. The creation of community spaces could provide a platform from which these issues could be simultaneously addressed. Already we are seeing some success across the country with this approach, such as Project Silk in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and The Evolution Project in Atlanta, Georgia.73,74 Public health would do well to think of the impressive synergy that could be achieved by partnering with Black MSM and situating interventions within spaces dedicated to their complete wellness. The approaches that hold the key to ending the HIV epidemic are those that acknowledge that Black MSM communities—like any other communities—are primarily defined not by a disease but through shared experiences, culture, adversity, and history.

CONCLUSIONS

“Black men loving Black men is the revolutionary act.”13

—Joseph Beam, author and journalist (1954–1988)

Beam’s contemporary, Black gay filmmaker and activist Marlon Riggs, further popularized these words by placing them at the end of Tongues Untied,33 a 1989 semiautobiographical documentary that explored the complex relationships between race, civil rights, sexuality, and the HIV epidemic among Black gay men. We must remember that despite impressive scientific advances in HIV prevention and treatment, these social contexts remain just as relevant today as they did 25 years ago. Good intentions are a vital starting point, but lest we forget our ability to cause harm in the communities we intend to serve, we must advance our understanding and discussion so that our actions are also beneficial. The fact that Black MSM are at increased risk for HIV infection, a disparity that is not solely a function of individual sexual behavior, should remind us to examine and change structural inequity. We cannot afford to focus on the individual sexual behaviors of Black MSM or their decisions to partner with one another; rather, we must strengthen the contexts in which Black MSM live to ensure that these networks are not exposed to increased risk. In moving forward with public health practice, we must ensure that we do not usurp the role of Black MSM communities and perpetrate an act of scientific violence in the process.

We call on public health to continue in the advancement of science and action, but not at the expense of reframing the revolutionary act—part of the very fabric of what has kept Black MSM communities together and likely staved off worse harm. Despite a history full of loss from HIV, racism, stigma, violence, and homophobia, Black MSM have chosen to love one another. This simple fact is in the data, yet so often we fail to interpret it for what it is. If we are to put an end to the HIV epidemic among Black MSM, these sexual partnerships cannot be pathologized, but should be celebrated for the victory they already represent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Training Program to Address HIV-Related Health Disparities in MSM (men who have sex with men), National Institute for Mental Health award T32MH094174.

We thank the University of Pittsburgh Center for LGBT Health Research for comments on an earlier draft of the article.

Note. This article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was required because no human participants were involved in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African American gay and bisexual men. 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/racialethnic/bmsm/facts. Accessed August 4, 2014.

- 2.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young RM, Meyer IH. The trouble with “MSM” and “WSW”: erasure of the sexual-minority person in public health discourse. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1144–1149. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.046714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Eshleman SH et al. Correlates of HIV acquisition in a cohort of black men who have sex with men in the United States: HIV prevention trials network (HPTN) 061. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg E, Millett G, Sullivan P, Del Rio C, Curran J. Understanding the HIV disparities between black and white men who have sex with men in the USA using the HIV care continuum: a modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2014;1(3):e112–e118. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)00011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews DD, Herrick A, Coulter RW et al. Running backwards: consequences of current HIV incidence rates for the next generation of black MSM in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1158-z. Epub ahead of print August 13, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21(15):2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Kegler C et al. The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):e75–e82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brondolo E, Gallo LC, Myers HF. Race, racism and health: disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodger A, Bruun T, Cambiano V, et al. HIV transmission risk through condomless sex if HIV+ partner on suppressive ART: PARTNER Study. Paper presented at: 21st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 3–6, 2014; Boston, MA.

- 12.Skarbinski J, Rosenberg E, Paz-Bailey G et al. Human immunodeficiency virus transmission at each step of the care continuum in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):588–596. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beam J. Brother to brother: words from the heart. In: Beam J, editor. In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology. Boston, MA: Alyson Publications; 1986. pp. 230–242. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemphill E. Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 1992. Loyalty; pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Racial differences in same-race partnering and the effects of sexual partnership characteristics on HIV risk in MSM: A prospective sexual diary study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(3):329–333. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e5f8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clerkin EM, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Unpacking the racial disparity in HIV rates: the effect of race on risky sexual behavior among Black young men who have sex with men (YMSM) J Behav Med. 2011;34(4):237–243. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry M, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Same race and older partner selection may explain higher HIV prevalence among black men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2007;21(17):2349–2350. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f12f41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raymond HF, McFarland W. Racial mixing and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):630–637. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han C-s. They don’t want to cruise your type: gay men of color and the racial politics of exclusion. Soc Identities. 2007;13(1):51–67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phua VC, Kaufman G. The crossroads of race and sexuality date selection among men in Internet “personal” ads. J Fam Issues. 2003;24(8):981–994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(5):250–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tieu H-V, Murrill C, Xu G, Koblin BA. Sexual partnering and HIV risk among black men who have sex with men: New York City. J Urban Health. 2010;87(1):113–121. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9416-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan PS, Peterson J, Rosenberg ES et al. Understanding racial HIV/STI disparities in black and white men who have sex with men: a multilevel approach. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudhinaraset M, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Convergence of HIV prevalence and inter-racial sexual mixing among men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2004–2011. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1550–1556. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Cranston K et al. Sexual mixing patterns and partner characteristics of black MSM in Massachusetts at increased risk for HIV infection and transmission. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):602–623. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9363-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baldwin J, Stein S. Native Sons. New York, NY: One World; 2004. pp. 96–97. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, Kelley CF, et al. Race and age disparities in HIV incidence and prevalence among MSM in Atlanta, GA. Paper presented at: 21st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 3–6, 2014; Boston, MA.

- 29.Guo J. The black HIV epidemic: a public health mystery from Atlanta’s gay community. Washington Post. August 4, 2014. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/storyline/wp/2014/08/04/the-black-hiv-epidemic-a-public-health-mystery-and-love-story-from-atlantas-gay-community. Accessed March 10, 2015.

- 30.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14(1):32–38. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah NS, Iveniuk J, Muth SQ et al. Structural bridging network position is associated with HIV status in a younger black men who have sex with men epidemic. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):335–345. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0677-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riggs M. Tongues Untied [documentary film] 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Kessel S, Palfrey J, DuRant RH. The association between health risk behaviors and sexual orientation among a school-based sample of adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):895–902. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kornblut AE. Boston doctor says ads distort his work on gays. Boston Globe. 1998 B1. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hogg RS, Strathdee SA, Craib K, O’Shaughnessy MV, Montaner J, Schechter MT. Modelling the impact of HIV disease on mortality in gay and bisexual men. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(3):657–661. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hogg RS, Strathdee SA, Craib KJ, O’Shaughnessy MV, Montaner J, Schechter MT. Gay life expectancy revisited. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(6):1499. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.6.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pew Research Center. The evolving role of news on Twitter and Facebook. 2015. Available at: http://www.journalism.org/2015/07/14/the-evolving-role-of-news-on-twitter-and-facebook. Accessed March 16, 2015.

- 39.Plummer MD. Sexual Racism in Gay Communities: Negotiating the Ethnosexual Marketplace [dissertation] Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith JG. Sexual Racism in a Gay Community on the US–Mexico Border: Revisiting the Latin Americanization Thesis Online. [master’s thesis]. El Paso, TX: University of Texas; 2012.

- 41.Icard LD. Black gay men and conflicting social identities: sexual orientation versus racial identity. J Soc Work Hum Sex. 1986;4(1–2):83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Rhue S. The impact of perceived discrimination on the intimate relationships of black lesbians. J Homosex. 1993;25(4):1–14. doi: 10.1300/J082v25n04_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson PA, Valera P, Ventuneac A, Balan I, Rowe M, Carballo-Diéguez A. Race-based sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering among men who use the Internet to identify other men for bareback sex. J Sex Res. 2009;46(5):399–413. doi: 10.1080/00224490902846479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnold EA, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. “Triply cursed”: racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young black gay men. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16(6):710–722. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.905706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayala G, Bingham T, Kim J, Wheeler DP, Millett GA. Modeling the impact of social discrimination and financial hardship on the sexual risk of HIV among Latino and black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 2):S242–S249. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paul JP, Ayala G, Choi K-H. Internet sex ads for MSM and partner selection criteria: the potency of race/ethnicity online. J Sex Res. 2010;47(6):528–538. doi: 10.1080/00224490903244575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith J. Getting off online: race, gender, and sexuality in cyberspace. In: Farris N, Davis MA, Compton DLR, editors. Illuminating How Identities, Stereotypes and Inequalities Matter Through Gender Studies. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wohl AR, Galvan FH, Myers HF et al. Do social support, stress, disclosure and stigma influence retention in HIV care for Latino and African American men who have sex with men and women? AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1098–1110. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberger JG, Herbenick D, Novak DS, Reece M. What’s love got to do with it? Examinations of emotional perceptions and sexual behaviors among gay and bisexual men in the United States. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):119–128. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calabrese SK, Rosenberger JG, Schick VR, Novak DS. Pleasure, affection, and love among black men who have sex with men (MSM) versus MSM of other races: countering dehumanizing stereotypes via cross-race comparisons of reported sexual experience at last sexual event. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(7):2001–2014. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0405-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis MA, Uhrig JD, Ayala G, Stryker JE. Reaching men who have sex with men for HIV prevention messaging with new media: recommendations from an expert consultation. Ann Forum Collab HIV Res. 2011;13(1):10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cahill S, Valadéz R, Ibarrola S. Community-based HIV prevention interventions that combat anti-gay stigma for men who have sex with men and for transgender women. J Public Health Policy. 2013;34(1):69–81. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2012.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kates N, Singer B. Brother Outsider [documentary film]. 2003.

- 54.Lewis F. White noise. Philadelphia City Paper. May 1–8, 1997. Available at: http://www.citypaper.net/articles/050197/article015.shtml. Accessed November 12, 2015.

- 55.Cohen J. Making headway under hellacious circumstances. Science. 2006;313(5786):470–473. doi: 10.1126/science.313.5786.470b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ford CL, Whetten KD, Hall SA, Kaufman JS, Thrasher AD. Black sexuality, social construction, and research targeting “The Down Low” (“The DL”) Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malebranche DJ. Bisexually active black men in the United States and HIV: acknowledging more than the “Down Low.”. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37(5):810–816. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saleh LD, Operario D. Moving beyond “the Down Low”: a critical analysis of terminology guiding HIV prevention efforts for African American men who have secretive sex with men. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(2):390–395. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hughes L. One Way Ticket. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press; 1949. Democracy; pp. 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(4):337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;(spec no):80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilson PA, Nanin J, Amesty S, Wallace S, Cherenack EM, Fullilove R. Using syndemic theory to understand vulnerability to HIV infection among black and Latino men in New York City. J Urban Health. 2014;91(5):983–998. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9895-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nazroo JY. The structuring of ethnic inequalities in health: economic position, racial discrimination, and racism. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):277–284. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riggs E, Gussy M, Gibbs L, Gemert C, Waters E, Kilpatrick N. Hard to reach communities or hard to access services? Migrant mothers’ experiences of dental services. Aust Dent J. 2014;59(2):201–207. doi: 10.1111/adj.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crozier G, Davies J. Hard to reach parents or hard to reach schools? A discussion of home–school relations, with particular reference to Bangladeshi and Pakistani parents. Br Educ Res J. 2007;33(3):295–313. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Herrick AL, Lim SH, Wei C et al. Resilience as an untapped resource in behavioral intervention design for gay men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(suppl 1):S25–S29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herrick AL, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Egan JE, Mayer KH. Resilience as a research framework and as a cornerstone of prevention research for gay and bisexual men: theory and evidence. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0384-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gostin LO, Powers M. What does social justice require for the public’s health? Public health ethics and policy imperatives. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(4):1053–1060. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Calvo-Armengol A, Jackson MO. The effects of social networks on employment and inequality. Am Econ Rev. 2004;94(3):426–454. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(suppl 1):S115–S122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Chovnick G. The past, present, and future of HIV prevention: integrating behavioral, biomedical, and structural intervention strategies for the next generation of HIV prevention. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:143–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Project Silk. 2014. Available at: http://projectsilk.org. Accessed November 15, 2014.

- 74. The Evolution Project. 2014. Available at: http://evolutionatl.org. Accessed November 15, 2014.