Abstract

Objective:

We aimed to analyse the peak CT number (PEAK) in CT number histogram of ground-glass nodules (GGN), meaning the most frequent density of pixels in the image of pulmonary nodule, based on three-dimensional (3D) reconstructive model pre-operatively, and the mean rate of PEAK change (V-PEAK) during a follow-up of GGN for differential diagnosis between pre-invasive adenocarcinoma (PIA) and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC).

Methods:

CT number histogram of pixels in GGN was made automatically by 3D measurement software. Diameter, total volume, PEAK and V-PEAK were measured from CT data sets of different groups classified by pathology, subtype and number of GGN, respectively.

Results:

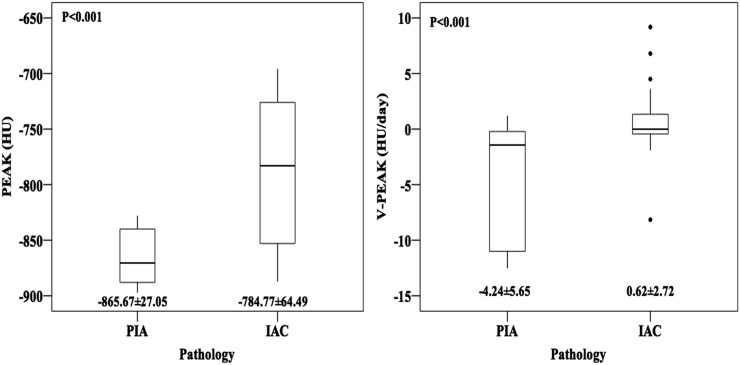

Among all 102 cases, 47 were PIA, including atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (n = 29) and adenocarcinoma in situ (n = 18), and 55 were IAC, including minimally IAC (MIA, n = 4). By Wilcoxon test, PEAK of IAC was significantly higher than that of PIA (p < 0.001). By receiver operating curve analysis, area under the curve (AUC) was 0.857 and threshold −820.50 Hounsfield units (HU) for differentiation between PIA and IAC. V-PEAK of IAC was unexpectedly remarkably smaller than that of PIA (p < 0.001) with AUC and threshold being 0.810 and −0.829 HU day−1, respectively.

Conclusion:

Pre-operative PEAK and V-PEAK, which interpret and evaluate the change of volume and density of pulmonary nodule simultaneously from both exterior and interior perspectives, can help to distinguish IAC from PIA.

Advances in knowledge:

This study provided researchers of GGN another perspective, taking both volume and density of nodules into consideration for pathological evaluation.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of low-dose CT and advances in high-resolution CT had greatly increased the detection of ground-glass nodules (GGN), which has been described as a hazy increased attenuation of the lung on CT with preservation of bronchial and vascular margins and been demonstrated as the precursor of lung adenocarcinoma according to data from many studies.1–5 Although inflammatory lesions may resolve spontaneously, or after treatment with antibiotics, both pre-invasive adenocarcinoma (PIA), including atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC), including minimally IAC (MIA), can often appear as similar GGN and may not enlarge for several months or more, making it difficult to differentially diagnose even at a follow-up.6–8

As we all know, follow-up plays a crucial role in clinical assessment and management of GGN.9–12 As a significant and effective indicator, volume-doubling time (VDT) could relatively assess pathological behaviour of GGN during follow-up.13,14 However, as derived from the volume of GGN, VDT was only applied to evaluate its exterior or outline features. As a matter of fact GGN is heterogeneous with plenty of interior information manifested by CT number within it. Recently, an awareness of the significance of CT number in assessing GGN has been reported.15–17

In the present study, the peak CT number (PEAK) before surgery and the mean rate of PEAK change (V-PEAK) during a follow-up of GGN with the pathology of PIA and IAC were measured based on a three-dimensional (3D) reconstructive procedure. PEAK means the most frequent CT number of the most pixels within the whole nodule corresponding to the highest bar in CT number histogram of nodule, whereas V-PEAK means variation of interior features of GGN during a follow-up.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Eligibility

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shanghai First People's Hospital (No. 2014KY115). Written informed consent for patients to participate in this research was obtained before the retrospective study.

Patients

According to the new International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society (IASLC/ATS/ERS) classification of pulmonary adenocarcinoma, we retrospectively reviewed the medical materials of 102 patients with the finding of GGN on the low-dose CT scans and undergoing surgical resection at our hospital from October 2012 to January 2015. All these nodules were diagnosed as PIA (AAH, n = 29 and AIS, n = 18) and IAC (MIA, n = 41 and IAC, n = 14).

All cases had been detected with at least one GGN on CT screening with diameters <3 cm and without history of primary or metastatic lung carcinoma. After the first detection of GGN patients should have been treated with antibiotics for 2 weeks. Then they would be suggested to take another CT scan at 3 months or later as a follow-up after the first time GGN were detected. Only stable or size-increasing lesions after anti-inflammatory could be selected into this research, with the exclusion of those transient ones reckoned as inflammatory in most cases. The exclusion criteria were transient GGN, lesions with diameters of the maximum area section >3 cm, small-cell lung carcinoma, squamous carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma exceeding T1N0M0, interval of pre-operative follow-up less than 3 months or absent, cases with a history of primary lung cancer or extrapulmonary cancer and cases with chemoradiotherapy or biopsy pre-operatively. The chest radiologist classified all 102 GGN as pure GGN (n = 30) and mixed GGN (n = 72) by imaging component of nodules as well as solitary GGN (n = 62) and multiple GGN (n = 40) by number of nodules in 1 patient. But coexisting nodules in the selected case have not been chosen for this study if they had not been resected simultaneously due to abscence of pathological diagnosis. Table 1 shows the clinical and radiologic characteristics of the enrolled cases.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of all ground-glass nodules (GGNs) with different pathological categoriesa (n = 102)

| Variables | PIA (n = 47) | IAC (n = 55) | p-valuec,d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Number) | 0.14 | ||

| Male | 23 | 34 | |

| Female | 24 | 21 | |

| Mean age (years) | 53.14 ± 5.80b | 60.61 ± 10.68 | 0.001 |

| GGN subtype | 0.226 | ||

| Pure GGN | 16 | 24 | |

| Mixed GGN | 31 | 31 | |

| GGN number (n) | 0.07 | ||

| Solitary | 26 | 42 | |

| Multiple | 21 | 13 | |

| Three-dimensional parameters | |||

| Diameter (mm) | 8.64 ± 2.42 | 15.76 ± 8.96 | <0.001 |

| Total volume (mm3) | 142.86 ± 112.47 | 1371.25 ± 1200.59 | 0.008 |

| PEAK | −865.67 ± 27.05 | −784.77 ± 64.49 | 0.001 |

| Increasing velocity of peak CT number (V-PEAK) | −4.24 ± 5.65 | −0.62 ± 2.72 | <0.001 |

IAC, invasive adenocarcinoma; PEAK, peak CT number; PIA, pre-invasive adenocarcinoma; V-PEAK, rate of PEAK change.

Classification according to the new IASLC/ATS/ERS International Multidisciplinary Lung Adenocarcinoma Classification system: PIA, including atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma in situ, adenocarcinoma including minimally invasive adenocarcinoma and IAC.

Unless otherwise indicated, numerical data were recorded as the mean ± standard deviation.

Gender, GGN subtype and GGN number were analyzed by χ2 test. Mean age, diameter, TV, PEAK and V-PEAK were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Wilcoxon test, given these data were abnormally distributed.

p-values for one-way ANOVA of all GGNs.

Image acquisition

CT images were obtained by using three CT scanners (Somatom® Plus 4, Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany; LightSpeed® Ultra, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI; or Mx8000, Philips Medical System, Andover, MA) exploring from the thoracic inlet to lung base with patients at full inspiration. No intravenous contrast material was injected. Axial images of 0.625 mm thickness were reconstructed with tube voltage ranging from 120 to 140 kV, tube current ranging from 200 to 400 mA and 512 × 512 matrix by using high-spatial-frequency algorithm and the smallest field of view including both lungs.

Three-dimensional reconstruction, histogram of CT number and measurement of PEAK and V-PEAK

In our study, we measured diameter, total volume (TV) and PEAK of all enrolled nodules every time at follow-up. These parameters were measured on a commercially available workstation (Advantage Workstation 4.3; GE Healthcare, Barrington, IL) by its lung analysis software (Lung VCAR; GE Healthcare). Lung nodules were segmented by the software on the basis of ground-glass attenuation value. The CT lung analysis software system automatically identified the GGN nodules in all x, y and z directions from the surrounding normal lung tissue. The elimination of normal structures within or around the nodule, such as vessels and bronchioles, was performed using several image-processing techniques. Some authors have described concrete procedures and operational methods of the exact software.14,18–22 CT number histogram of GGN can be obtained from not only this software but some similar ones as well. Additionally, other authors have already studied CT number histograms for differential diagnosis of GGN15,16,23,24 (Figure 1). Two chest radiologists, with 10 and 14 years' experience of reading thoracic CT images, respectively, identified measurement of these parameters by consensus before surgery.

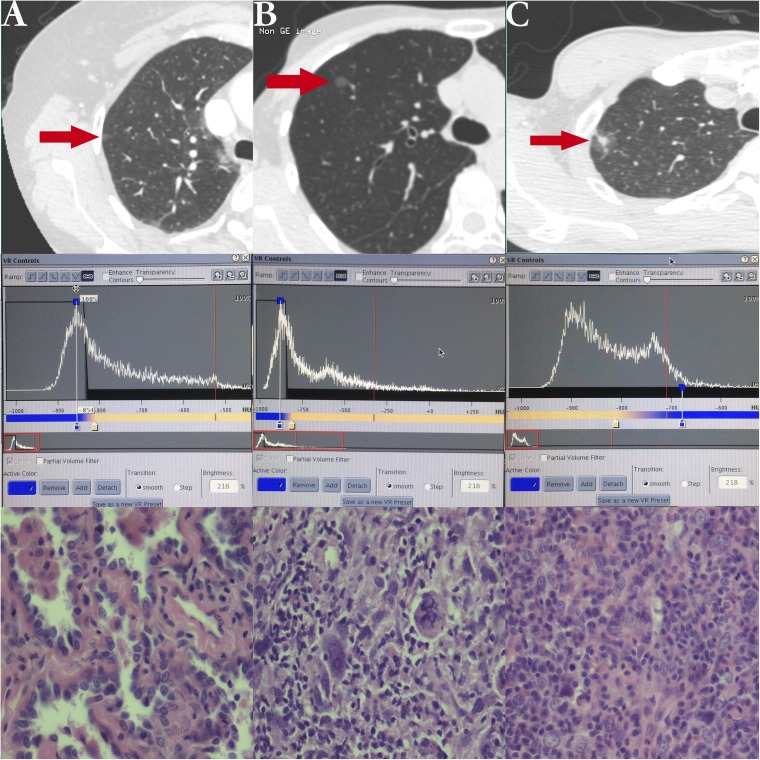

Figure 1.

Example of nodules displayed on CT (arrows) and their histogram and pathological outcomes. (a) A pure ground-glass nodule (GGN) on high-resolution CT adhering to pleura with pathology of atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and a single peak in the histogram of CT number. (b) A pure GGN with pathology of adenocarcinoma in situ and a single peak in histogram. (c) A mixed GGN with pathology of minimally invasive adenocarcinoma and two peaks in histogram.

PEAK is the most frequent CT number presented by the most pixels within the whole nodule, which corresponds to the highest bar in CT number histogram. V-PEAK was calculated by the following formula.

As proliferative curve of cancer cells presents a sigmoid one, the changing rate of CT number was alterable during the whole progress of lung cancer. Therefore, these parameters we defined above only indicated the mean rate of CT number change in GGN during 3 months of pre-operative follow-up.

Statistics analysis

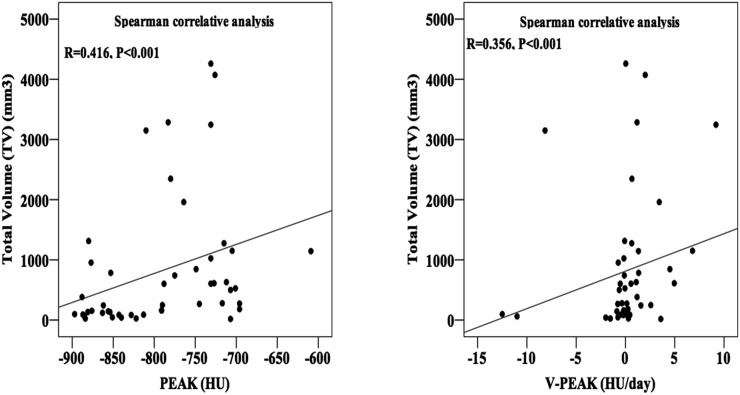

Numerical data were recorded as mean ± standard deviation. Wilcoxon test was performed for data of abnormal distribution to compare statistical significant differences of PEAK and V-PEAK between PIA and IAC. We also compared PEAK and V-PEAK between pure and mixed GGN, as well as between solitary and multiple GGN. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis has been used for assessing the diagnostic specificity and sensitivity of PEAK and V-PEAK. Given that data sets of PEAK and V-PEAK had abnormal distribution, Spearman correlation coefficient was used to evaluate correlations of PEAK and V-PEAK with TV of GGN, respectively.

All statistical analyses were performed by a software program (SPSS® v. 20.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). p-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULT

The measurements of diameter, TV, PEAK and V-PEAK of GGNs could be found in Table 1. Obviously, IAC group owned a significant larger mean age, diameter, TV and PEAK with a p-value <0.05 compared with those of PIA. However, we got a remarkably higher V-PEAK of PIA (−4.24 ± 5.65 HU day−1) with a minus before it than that of IAC (0.62 ± 2.72 HU day−1), which means that PEAK of PIA had decreased during a follow-up at a faster rate, whereas PEAK of IAC increased at a slower rate. Moreover, there is no statistical difference between PIA and IAC with regard to the subtype and position of GGN (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Boxplots comparing the peak CT number (PEAK) and mean rate of PEAK change (V-PEAK) of pre-invasive adenocarcinoma (PIA) and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC).

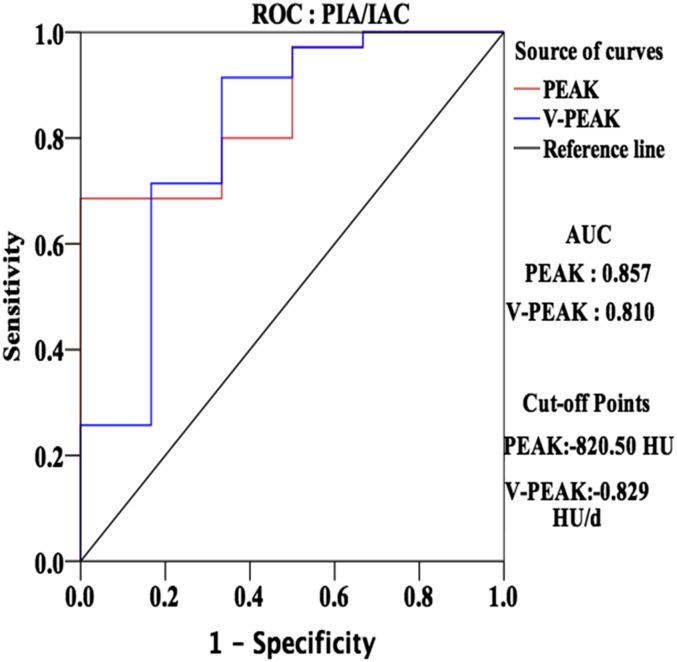

Area under the curve of PEAK and V-PEAK were 0.857 and 0.851, respectively, in ROC analysis. The optimal cut-off points were defined as those on the curves closest to the upper left-hand corner.25 Therefore, thresholds of PEAK and V-PEAK for pathological differentiation were −820.50 and −0.829 HU day−1, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the peak CT number (PEAK) and the mean rate of PEAK change (V-PEAK) of ground-glass nodule (GGN) for differentiation between pre-invasive adenocarcinoma (PIA) and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC). AUC, area under the curve.

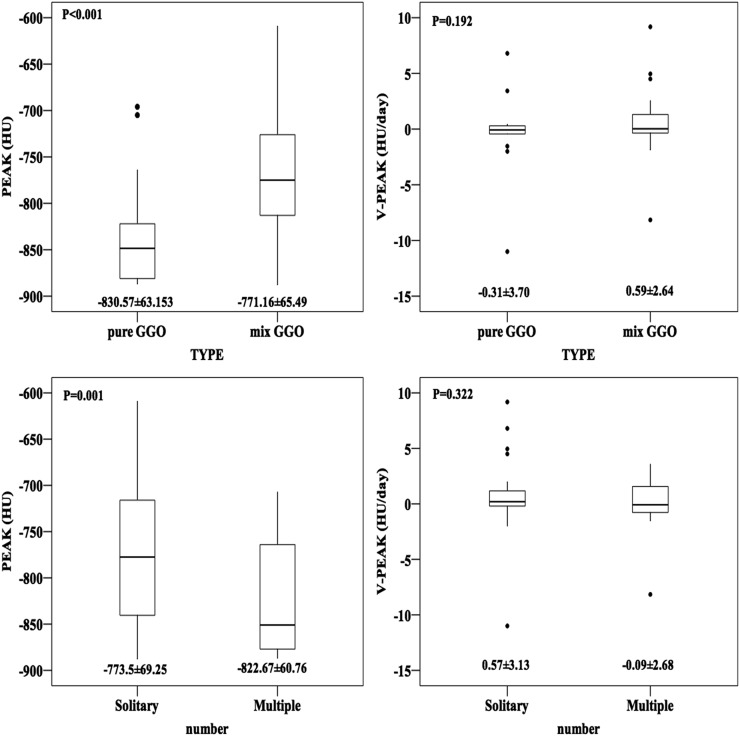

PEAK was −830.57 ± 63.15, −771.16 ± 65.49, −773.50 ± 69.25 and −822.67 ± 60.76 HU in pure GGN, mix GGN, solitary GGN and multiple GGN, respectively. V-PEAK was −0.31 ± 3.70, 0.59 ± 2.64, 0.57 ± 3.13 and −0.09 ± 2.68 HU day−1 in pure GGN, mix GGN, solitary GGN and multiple GGN, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Boxplots comparing the peak CT number (PEAK) and mean rate of PEAK change (V-PEAK) of different subtypes such as pure ground-glass nodule (GGN) and mixed GGN and different number status such as solitary GGN and multiple GGN. PIA, pre-invasive adenocarcinoma; IAC, invasive adenocarcinoma.

By Spearman correlation analysis, both PEAK and V-PEAK had significant correlations with TV of GGN (p < 0.001) with a moderated correlative coefficient of 0.416 and 0.356, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Graphs assessing the correlation between total volume (TV) of ground-glass nodule (GGN) and the peak CT number (PEAK) in histogram of GGN and mean rate of PEAK change (V-PEAK) by Spearman correlative analysis.

DISCUSSION

Recently, 3D quantitative assessment of pulmonary nodules on CT images has attracted increasing attention.26–31 Parameters, such as mean diameter, volume and all kinds of CT number, could be measured accurately in 3D reconstructive model of nodules, presenting a whole configuration with more intuitional, stereo and distinct vision.32–37

CT number histogram is a potentially useful method for quantitative analysis of early stage non-small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs).15,16,24,30 So far, most researches about CT number histogram are almost related to histogram pattern, mean CT number, 5th to 95th percentile CT number, skewness and kurtosis.38–44 Nomori et al17 found that single-peak pattern in histogram appeared in all AAH and bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) cases in their study and the PEAK and average CT number of AAH were smaller than those of BAC. Ikeda et al15 had studied number of peaks, PEAK, average CT number (50th) and the 5th to 95th CT number in the histogram of GGN. They concluded that 100% AAH represented single peak, whereas 38% BAC and 42% AC two peaks, and the 75th CT number had a preferable capability for differentiating AAH from BAC with a sensitivity of 0.90 and a specificity of 0.81 when the threshold comes to −584 HU.

Nevertheless, we unprecedentedly combined PEAK in CT number histogram with follow-up of GGN to explore radiopathological behaviour of early stage lung cancer. Although the average CT number of nodule is easy to calculate in any CT model of GGN, it still can be affected by the density of vessels or bronchioles through the tumour. However, PEAK is the most frequent CT number presented by the most pixels, or main body, within the whole nodule, most likely locating at the periphery of GGN. It is the highest bar in CT number histogram of nodules and allows the effect of vessels and bronchioles because not only the effects of vessels and bronchioles could be eliminated automatically by software but also these effects just can change the highest CT number within GGN instead of the main body density.16 PEAK means the most frequent CT number owned by the main part rather than the highest one owned by the centre part of GGN. For the same reason, V-PEAK indicates the mean changing rate of CT number of the main part of GGN during the progress of early lung adenocarcinoma.

In our research, we compared PEAK of PIA, including AAH and AIS, with that of IAC, also including MIA. As a result, we obtained a significant higher PEAK of IAC than of PIA. When it comes to CT number histogram, the highest bar of IAC would be inclined to appear at the right, whereas that of PIA would be to the left. The result means, expectedly, that IAC represented a higher density in the main body of nodules than PIA. From the perspective of pathological behaviour of lung carcinoma, invasive cancer cells most likely proliferate along the pulmonary alveoli and interstitial tissue and penetrate the basal layer resulting in higher density of the whole nodule than pre-invasive lesions, representing as a higher PEAK, given that PEAK belongs to the most frequent pixels in 3D CT images of GGN, and indicating CT number of the main body of nodules.45 When it comes to PIA, AAH was just localized lesion and mild proliferation of atypical Type II pneumocytes and Clara cells lining the alveolar walls and respiratory bronchioles. Gaps are usually seen between the cells consisting of rounded, cuboidal, low-columnar or “peg” cells with round to oval nuclei.46–48 Additionally, AIS is also a localized small (≤3 cm) adenocarcinoma with growth restricted to neoplastic cells along alveolar structures (lepidic growth), lacking stromal, vascular or pleural invasion. Thereafter, proliferation of PIA is restricted to primary lesion without diffusion such that the main body of nodules remains at a lower density or lower PEAK.45 (Figure 1)

However, during a follow-up, the mean rate of PEAK change, defined as V-PEAK, between groups were significantly different as well. V-PEAK of PIA was unexpectedly larger than that of IAC (PIA -4.25 ± 5.65 vs IAC 0.62 ± 2.72 HU day−1); the minus value of V-PEAKs means a decreasing trend. The research of Oda et al14 suggested that VDT was 859.2 ± 428.9, 421.2 ± 228.4 and 202.1 ± 84.3 days in AAH, BAC and IAC, respectively. Hence, during a follow-up, volume of most GGN, especially for malignant ones, would grow on one hand, and their density would also change on the other hand. As for PIA with a negative higher V-PEAK, the PEAK of PIA kept decreasing, meaning that the density of the main body of GGN kept closing to that of normal lung tissue. Therefore, this suggested that the growing rate of volume was faster than the increasing rate of mean density, which made the main body of nodules shift outwards from the inner part. When it comes to IAC, given the proliferative and invasive activity mentioned above, increase of density surpassed the growing of volume such that PEAK become higher during follow-up, which made pure GGNs and mixed GGNs gradually become solid lesions. As IAC lesions most likely already have a high density, the increasing rate of CT number of the main body in GGN was slow and therefore V-PEAK would be small.

ROC analysis could test the specificity and sensitivity of PEAK and V-PEAK for differential diagnosis. In our study, the area under the curve of PEAK and V-PEAK were 0.857 and 0.810 with optical cut-off points of −820.50 and −0.829 HU day−1, respectively. V-PEAK indicated comprehensive effects of growing volume and increasing density during a follow-up as previously mentioned. Therefore, we could evaluate invasive property of GGN by comparing PEAK and V-PEAK with these thresholds before surgery for indicating selection of surgical procedures such as wedge resection, segmentectomy or pulmonary lobectomy. When PEAK is higher than −820.50 HU or V-PEAK is larger than −0.829 HU day−1, a malignant lesion would trend to be an IAC, otherwise it would be PIA. We obtained sensitivity and specificity calculated by software during ROC analysis. In ROC, horizontal and vertical ordinate were 1-specificity and sensitivity, respectively. The optimal cut-off points were defined as those on the curves closest to the upper left-hand corner. Then, we got our thresholds, sensitivities and specificities. Threshold, sensitivity and specificity of PEAK were −820.50 HU, 0.92 and 0.67, and that of V-PEAK were −0.829 HU day−1, 0.69 and 1.00, respectively. According to these thresholds, we calculated positive- and negative-predictive values. In our research, the positive and negative of PEAK for differentiating IAC were 100% and 35.3%, and that of V-PEAK were 94.12% and 57.14%, respectively.

Additionally, we compared PEAK and V-PEAK in different groups divided by subtype and number of GGN. PEAK of mixed GGN (−771.16 ± 65.49) and solitary nodules (−773.5 ± 69.25) was remarkably higher than of pure GGN (−830.57 ± 63.15) and multiple ones (−822.67 ± 60.76), respectively (mixed GGN vs pure GGN p < 0.001, solitary nodules vs multiple nodules p = 0.001); however, significant difference of V-PEAK did not exist in these comparisons. As is well known, mixed GGN has a higher density than pure one. The reason why PEAK of solitary GGN was higher than of multiple GGN is still unknown to us. What we know is that the subtype and number of GGN cannot significantly affect the mean changing rate of PEAK. Eventually, positive correlation between PEAK and TV (R = 0.416, p < 0.001) means PEAK was higher in larger nodules because more pixels in 3D-model image presented high density. As a result, it is helpful for us preliminarily to evaluate PEAK before measurement.

The conception of precision medicine has been proposed in genomics and proteomics for precise and individual treatment. Traditional differential diagnosis of pulmonary nodule mostly rely on its morphological radiological features such as two-dimensional diameter, bronchus sign, spicule sign, pleural indentation sign and so on. All morphological signs are actually judged by observers subjectively, and most of such small nodules do not manifest these signs usually. Approach in our research quantitatively assessed radiological properties of GGNs. Moreover, PEAK and V-PEAK, the variables we defined, evaluated radiologic properties and their change from a perspective of substructure of heterogeneous GGN during follow-up. Radiology cannot completely differentiate pathological features of lesions with only one variable or sign, the same as molecular biology failed to diagnose cancer with one gene. In the future of management of GGNs, PEAK and V-PEAK could increase the differential diagnostic rate of GGN combining with other radiologic variables such as VDT.

CONCLUSION

Although follow-up is imperative for differential diagnosis of GGNs, interior growth was not considered into calculating VDT, and thus the actual VDT may be faster than the calculated VDT, especially for subsolid nodules. However, V-PEAK could describe the change of volume and density simultaneously from an overall perspective containing interior and exterior views. By our study, we found that PEAK and V-PEAK during a follow-up before surgery significantly contributed to differential diagnosis of GGN.

Contributor Information

Mingzheng Peng, Email: peng.mz@foxmail.com.

Zhao Li, Email: lizhao19881228@163.com.

Haiyang Hu, Email: huhaiyang1988@163.com.

Sida Liu, Email: 94164347@qq.com.

Binbin Xu, Email: 156816117@qq.com.

Wenzhuo Zhu, Email: iamzwz@hotmail.com.

Yudong Han, Email: chttc110@163.com.

Liwen Xiong, Email: xiong_li_wen@126.com.

Qiang Lin, Email: 156816117@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jang HJ, Lee KS, Kwon OJ, Rhee CH, Shim YM, Han J. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: focal area of ground-glass attenuation at thin-section CT as an early sign. Radiology 1996; 199: 485–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.2.8668800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki T, Nakata H, Watanabe H, Nakamura K, Kasai T, Hashimoto H, et al. Evolution of peripheral lung adenocarcinomas: CT findings correlated with histology and tumor doubling time. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000; 174: 763–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakajima R, Yokose T, Kakinuma R, Nagai K, Nishiwaki Y, Ochiai A. Localized pure ground-glass opacity on high-resolution CT: histologic characteristics. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2002; 26: 323–9. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200205000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakinuma R, Ohmatsu H, Kaneko M, Kusumoto M, Yoshida J, Nagai K, et al. Progression of focal pure ground-glass opacity detected by low-dose helical computed tomography screening for lung cancer. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2004; 28: 17–23. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200401000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakata M, Saeki H, Takata I, Segawa Y, Mogami H, Mandai K, et al. Focal ground-glass opacity detected by low-dose helical CT. Chest 2002; 121: 1464–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nomori H, Horio H. Colored collagen is a long-lasting point marker for small pulmonary nodules in thoracoscopic operations. Ann Thorac Surg 1996; 61: 1070–3. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(96)00024-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nomori H, Horio H, Fuyuno G, Kobayashi R, Morinaga S, Suemasu K. Lung adenocarcinomas diagnosed by open lung or thoracoscopic vs bronchoscopic biopsy. Chest 1998; 114: 40–4. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.1.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nomori H, Horio H, Naruke T, Suemasu K. Fluoroscopy-assisted thoracoscopic resection of lung nodules marked with lipiodol. Ann Thorac Surg 2002; 74: 170–3. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03615-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kodama K, Higashiyama M, Yokouchi H, Takami K, Kuriyama K, Kusunoki Y, et al. Natural history of pure ground-glass opacity after long-term follow-up of more than 2 years. Ann Thorac Surg 2002; 73: 386–92. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03410-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park CM, Goo JM, Lee HJ, Lee CH, Chun EJ, Im JG. Nodular ground-glass opacity at thin-section CT: histologic correlation and evaluation of change at follow-up. Radiographics 2007; 27: 391–408. doi: 10.1148/rg.272065061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah RM, Jimenez S, Wechsler R. Significance of ground-glass opacity on HRCT in long-term follow-up of patients with systemic sclerosis. J Thorac Imaging 2007; 22: 120–4. doi: 10.1097/01.rti.0000213572.16904.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soda H, Nakamura Y, Nakatomi K, Tomonaga N, Yamaguchi H, Nakano H, et al. Stepwise progression from ground-glass opacity towards invasive adenocarcinoma: long-term follow-up of radiological findings. Lung Cancer 2008; 60: 298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang B, Hwang JH, Choi YH, Chung MP, Kim H, Kwon OJ, et al. Natural history of pure ground-glass opacity lung nodules detected by low-dose CT scan. Chest 2013; 143: 172–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oda S, Awai K, Murao K, Ozawa A, Utsunomiya D, Yanaga Y, et al. Volume-doubling time of pulmonary nodules with ground glass opacity at multidetector CT: assessment with computer-aided three-dimensional volumetry. Acad Radiol 2011; 18: 63–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda K, Awai K, Mori T, Kawanaka K, Yamashita Y, Nomori H. Differential diagnosis of ground-glass opacity nodules: CT number analysis by three-dimensional computerized quantification. Chest 2007; 132: 984–90. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nomori H, Ohtsuka T, Naruke T, Suemasu K. Histogram analysis of computed tomography numbers of clinical T1 N0 M0 lung adenocarcinoma, with special reference to lymph node metastasis and tumor invasiveness. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003; 126: 1584–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nomori H, Ohtsuka T, Naruke T, Suemasu K. Differentiating between atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and bronchioloalveolar carcinoma using the computed tomography number histogram. Ann Thorac Surg 2003; 76: 867–71. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)00729-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linning E, Daqing M. Volumetric measurement pulmonary ground-glass opacity nodules with multi-detector CT: effect of various tube current on measurement accuracy–a chest CT phantom study. Acad Radiol 2009; 16: 934–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wormanns D, Kohl G, Klotz E, Marheine A, Beyer F, Heindel W, et al. Volumetric measurements of pulmonary nodules at multi-row detector CT: in vivo reproducibility. Eur Radiol 2004; 14: 86–92. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2132-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Awai K, Murao K, Ozawa A, Nakayama Y, Nakaura T, Liu D, et al. Pulmonary nodules: estimation of malignancy at thin-section helical CT–effect of computer-aided diagnosis on performance of radiologists. Radiology 2006; 239: 276–84. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2383050167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oda S, Awai K, Murao K, Ozawa A, Yanaga Y, Kawanaka K, et al. Computer-aided volumetry of pulmonary nodules exhibiting ground-glass opacity at MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010; 194: 398–406. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maksimovic R, Stankovic S, Milovanovic D. Computed tomography image analyzer: 3D reconstruction and segmentation applying active contour models–'snakes'. Int J Med Inform 2000; 58-59: 29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1386-5056(00)00073-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamura M, Shimizu Y, Yamamoto T, Yoshikawa J, Hashizume Y. Predictive value of one-dimensional mean computed tomography value of ground-glass opacity on high-resolution images for the possibility of future change. J Thorac Oncol 2014; 9: 469–72. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamiya A, Murayama S, Kamiya H, Yamashiro T, Oshiro Y, Tanaka N. Kurtosis and skewness assessments of solid lung nodule density histograms: differentiating malignant from benign nodules on CT. Jpn J Radiol 2014; 32: 14–21. doi: 10.1007/s11604-013-0264-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akobeng AK. Understanding diagnostic tests 3: receiver operating characteristic curves. Acta Paediatr 2007; 96: 644–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.00178.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yankelevitz DF, Reeves AP, Kostis WJ, Zhao B, Henschke CI. Small pulmonary nodules: volumetrically determined growth rates based on CT evaluation. Radiology 2000; 217: 251–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.1.r00oc33251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Klaveren RJ, Oudkerk M, Prokop M, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Vernhout R, et al. Management of lung nodules detected by volume CT scanning. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 2221–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Hoop B, Gietema H, van Ginneken B, Zanen P, Groenewegen G, Prokop M. A comparison of six software packages for evaluation of solid lung nodules using semi-automated volumetry: what is the minimum increase in size to detect growth in repeated CT examinations. Eur Radiol 2009; 19: 800–8. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1229-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Hoop B, Gietema H, van de Vorst S, Murphy K, van Klaveren RJ, Prokop M. Pulmonary ground-glass nodules: increase in mass as an early indicator of growth. Radiology 2010; 255: 199–206. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawata Y, Niki N, Ohmatsu H, Moriyama N. Example-based assisting approach for pulmonary nodule classification in three-dimensional thoracic computed tomography images. Acad Radiol 2003; 10: 1402–15. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)00507-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sumikawa H, Johkoh T, Nagareda T, Sekiguchi J, Matsuo K, Fujita Y, et al. Pulmonary adenocarcinomas with ground-glass attenuation on thin-section CT: quantification by three-dimensional image analyzing method. Eur J Radiol 2008; 65: 104–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludwig DR, Menon PG, Schwartzman D. CT-Electromagnetic three-dimensional tracking for renal endovascular sympathetic ablation catheter positioning in an animal model. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2015; 26: 741–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maldonado F, Boland JM, Raghunath S, Aubry MC, Bartholmai BJ, Deandrade M, et al. Noninvasive characterization of the histopathologic features of pulmonary nodules of the lung adenocarcinoma spectrum using computer-aided nodule assessment and risk yield (CANARY)–a pilot study. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8: 452–60. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182843721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritter M, Rassweiler MC, Häcker A, Michel MS. Laser-guided percutaneous kidney access with the Uro Dyna-CT: first experience of three-dimensional puncture planning with an ex vivo model. World J Urol 2013; 31: 1147–51. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0847-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freundt MI, Ritter M, Al-Zghloul M, Groden C, Kerl HU. Laser-guided cervical selective nerve root block with the Dyna-CT: initial experience of three-dimensional puncture planning with an ex-vivo model. PLoS One 2013; 8: e69311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun CJ, Li C, Yu JM, Li T, Lv HB, Luo YX, et al. Comparison of 64-slice CT perfusion imaging with contrast-enhanced CT for evaluating the target volume for three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy in the rabbit VX2 brain tumor model. J Radiat Res 2012; 53: 454–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tobita K, Ohnishi I, Matsumoto T, Ohashi S, Bessho M, Kaneko M, et al. Effect of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound stimulation on callus remodelling in a gap-healing model: evaluation by bone morphometry using three-dimensional quantitative micro-CT. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93: 525–30. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B4.25449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Son JY, Lee HY, Lee KS, Kim JH, Han J, Jeong JY, et al. Quantitative CT analysis of pulmonary ground-glass opacity nodules for the distinction of invasive adenocarcinoma from pre-invasive or minimally invasive adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 2014; 9: e104066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao X, Chu C, Li Y, Lu P, Wang W, Liu W, et al. The method and efficacy of support vector machine classifiers based on texture features and multi-resolution histogram from (18)F-FDG PET-CT images for the evaluation of mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with lung cancer. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 312–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flechsig P, Kratochwil C, Schwartz LH, Rath D, Moltz J, Antoch G, et al. Quantitative volumetric CT-histogram analysis in N-staging of 18F-FDG-equivocal patients with lung cancer. J Nucl Med 2014; 55: 559–64. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.128504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burger IA, Vargas HA, Apte A, Beattie BJ, Humm JL, Gonen M, et al. PET quantification with a histogram derived total activity metric: superior quantitative consistency compared to total lesion glycolysis with absolute or relative SUV thresholds in phantoms and lung cancer patients. Nucl Med Biol 2014; 41: 410–18. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawata Y, Niki N, Ohmatsu H, Kusumoto M, Tsuchida T, Eguchi K, et al. Quantitative classification based on CT histogram analysis of non-small cell lung cancer: correlation with histopathological characteristics and recurrence-free survival. Med Phys 2012; 39: 988–1000. doi: 10.1118/1.3679017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roeder F, Friedrich J, Timke C, Kappes J, Huber P, Krempien R, et al. Correlation of patient-related factors and dose-volume histogram parameters with the onset of radiation pneumonitis in patients with small cell lung cancer. Strahlenther Onkol 2010; 186: 149–56. doi: 10.1007/s00066-010-2018-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fay M, Tan A, Fisher R, Mac Manus M, Wirth A, Ball D. Dose-volume histogram analysis as predictor of radiation pneumonitis in primary lung cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 61: 1355–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society: international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol, 2011; 6: 244–85. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kitamura H, Kameda Y, Ito T, Hayashi H. Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the lung. Implications for the pathogenesis of peripheral lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1999; 111: 610–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takigawa N, Segawa Y, Nakata M, Saeki H, Mandai K, Kishino D, et al. Clinical investigation of atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the lung. Lung Cancer 1999; 25: 115–21. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(99)00055-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mori M, Rao SK, Popper HH, Cagle PT, Fraire AE. Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the lung: a probable forerunner in the development of adenocarcinoma of the lung. Mod Pathol 2001; 14: 72–84. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]