Abstract

Objectives

The impact of policy and funding on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) activity and capacity, from 2003 to 2012, was assessed. The focus was on preschool children (aged 0–4 years), as current and 2003 policy initiatives stressed the importance of ‘early intervention’.

Settings

National service capacity from English CAMHS mapping was obtained from 2003 to 2008 inclusive. English Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) for English CAMHS was obtained from 2003 to 2012. The Child and Adolescent Faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists surveyed its members about comparative 0–4-year service activity and attitudes in 2012.

Participants

CAMHS services in England provided HES and CAMHS mapping data. The Child and Adolescent Faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists are child psychiatrists, including trainees.

Outcome measures

CAMHS mapping data provided national estimates of total numbers of CAMHS patients, whereas HES data counted appointments or episodes of inpatient care. The survey reported on Child Psychiatrists' informal estimates of service activity and attitudes towards children aged 0–4 years.

Results

The association between service capacity and service activity was moderated by an interaction between specified funding and age, the youngest children benefiting least from specified funding and suffering most when it was withdrawn (Pr=0.005). Policy review and significant differences between age-specific HES trends (Pr<0.001) suggested this reflected prioritisation of older children. Clinicians were unaware of this effect at local level, though it significantly influenced their attitudes to prioritising this group (Pr=0.02).

Conclusions

If the new policy initiative for CAMHS is to succeed, it will need to have time-limited priorities attached to sustained, specified funding, with planning for limits as well as expansion. Data collection for policy evaluation should include measures of capacity and activity.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study covered a 10-year period, including a current and previous policy initiative for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS).

Information on the timing of funding and policy were separately analysed.

The study included multiple measures of impact, which were analysed concurrently where possible.

Only the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data covered the full timescale, while the questionnaire was cross-sectional.

Inpatients and outpatients were not clearly and uniformly distinguished in CAMHS mapping data, whereas HES data use different metrics for each, necessitating sensitivity analysis to clarify the effect of these.

Introduction

The UK government is about to spend an additional £1.25 billion over 5 years on ‘Future in Mind’, a policy initiative for children's mental health services, including provision for pregnant women, young mothers and armed forces veterans,1 to overcome problems in accessibility and improve service delivery.2 This includes expansion of early intervention to help prevent the development of mental health disorders that then produce enduring disability across the life span. We have been here before. Early intervention to prevent later disadvantage, increased access to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) and improved service delivery were key themes underpinning the previous funding uplift, of £250 million over 3 years, attached to the previous initiative ‘Every Child Matters’, in 2003.3 4 In 2006, when the CAMHS-specific uplift was ended, the Chief Medical Officer5 reported,

In return for this investment, Government has set a Public Service Agreement (PSA) target that a comprehensive CAMHS should be commissioned in all parts of England by the end of 2006. For the reasons set out in this report, this is a very challenging target, and it will require continued, sustained efforts on the part of many people if it is to be achieved. However it is also true that CAMHS have come a very long way in a short period of time, demonstrating a remarkable ability to improve the service provided to children and families.

We now know this did not happen,2 6 despite the enormous effort put into encouraging and monitoring progress, for example, the CAMHS mapping programme,7 and we need to understand why, if we are to avoid disappointment repeating itself. Allowing for inflation of 45% over 12 years, the current uplift is ∼2.25 times that made in 2003, so the stakes are higher. Preschool children make a good focus for researching this. They are primary targets for early intervention on psychopathological and economic grounds,8 9 were specifically identified (as infants and/or young children) in the 2004 CAMHS Public Service Agreement10 and are identified once again (within 0–5 children) in the current policy initiative.2 Early intervention can also refer to service delivery to teens, in particular those at risk of, or developing psychosis; these were also identified in both initiatives. Curiously, CAMHS service engagement with preschool children declined, though that with teens increased between 2005 and 2009.11 Understanding what happened to these groups of children following the 2003 initiative should help improve the chances of a successful outcome now.

Methods

Motivation and rationale

Although policy initiatives are usually described in terms of organisational change, these changes are implemented by individuals. From this perspective, such initiatives are systems of incentives, or constraints, which affect behaviour when balancing competing demands against resources. This has been found to affect service delivery, sometimes perversely, in a wide range of settings.12–15 In 2003–2004, policies were applied through the imposition of targets, typically expressed as ‘markers of good practice’.5 This implies two potential reasons for the need to ‘top up’ the 2003 initiative, given that CAMHS was capable of significant change:5 the funding uplift was inadequate and that the targets set led to perverse incentives, which undermined implementation. Exploring incentives implies a mixed methods approach, with questionnaire as well as objective statistical data, so that the latter may be related to workers' expressed opinions. Published data on CAMHS activity were therefore supplemented with a questionnaire sent to all members of the Child and Adolescent Faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Available information

Data were available from three main sources:

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) for child and adolescent psychiatry services were obtained from the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) for children aged 0–18 in England between 2003–2004 and 2012–2013 (the most recent available). Inpatient and day-patient activity is recorded by HSCIC as Finished Consultant Episodes (FCE), approximating to discrete periods of care; outpatient appointments are differentiated by first and subsequent attendances.16 While the HSCIC also hosts NHS reference cost data, separate collection of CAMHS-related data has only begun recently and has used variable classification.17 It was therefore not suitable to examine funding trends.

The CAMHS mapping service,7 which published data between the financial years 2003–2004 (henceforth 2003) and 2008–2009 (henceforth 2008), reported the national English CAMHS caseload in November of each year, banded by age into 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15 and 16–18 years. Outpatient and inpatient data were separated for the first 3 years, but thereafter combined. The mapping service also provided funding information. Because this was collected part way through the financial year (November), two statistics were reported: the actual spend up to the date of collection, and the predicted spend from that point to the end of the financial year.

A questionnaire was circulated to members of the Child and Adolescent Faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in November 2012. There were 432 respondents, though not all respondents answered all questions. It sought to discover if members were aware of changes in service activity regarding children aged 0–4 years, what service provision members reported for this group, and what members' attitudes were to services for them. A detailed description of the survey and its findings were submitted to the Faculty Executive as a preliminary report.

Additional information about funding was available from a parliamentary written answer,18 reporting a total of £49 million (6%) in cuts in Primary Care Trust (PCT) expenditure on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Disorders between 2010 and 2013, the latest figures available.

Analysis

The HES data were grouped into year bands of 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15 and 16–18, to match the age bands of the CAMHS mapping data. From the descriptions above, it can be seen that the HES data describe CAMHS activity, whereas the CAMHS mapping data estimate CAMHS capacity. Thus, though correlated, these data sets are not exchangeable, and bivariate plotting from 2003 to 2008, when both were available, suggested that their association was moderated by year and age. The analysis was therefore structured as follows:

Trends in service activity

This analysed the HES data from 2003 to 2012 inclusive. Fixed-slope and variable-slope mixed effect models of the data were compared to test differences in trends across the age bands.

The impact of ‘Every Child Matters’

This analysis combined the HES and CAMHS mapping data sets from 2003 to 2008 inclusive. To manage the different metrics, the data source was nested within time in a mixed methods model.

Medical opinion on children aged 0–4 years

As this survey provided staff-based opinions and views in 2012, it was analysed separately, using cross-sectional statistical techniques and tabulation of opinions.

Analyses were conducted using Excel and R software (especially R packages rcommander, car, lme4 and vcd), linked by RExcel, with SigmaStat V.13 for graph preparation.

Results

Trends in service activity

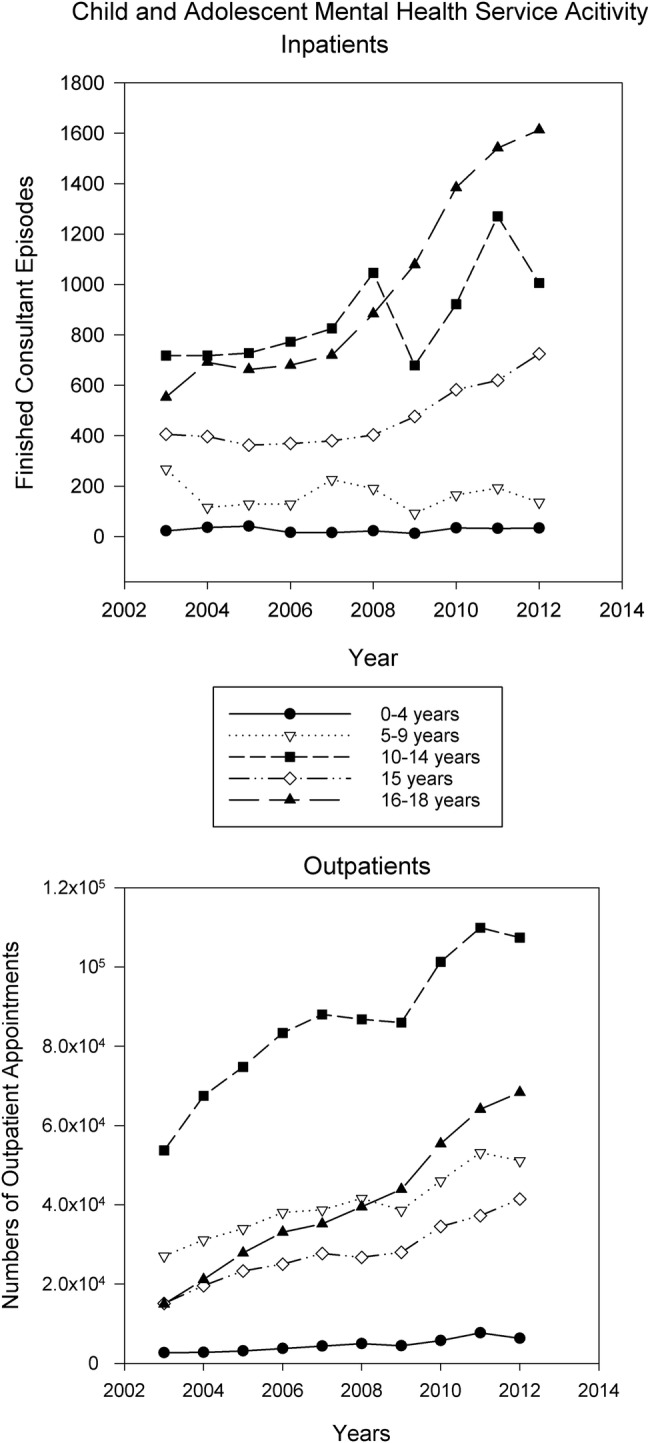

These, plotted by CAMHS mapping age bands, are reported in figure 1. Policy initiatives were concentrated in two groups as shown in table 1: 2003–2004 and 2010–2012. The CAMHS review, reported in 2008, was a report to government, and the second set of policy initiatives resulted from it.19

Figure 1.

Trends in CAMHS service activity 2003–2012. CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service.

Table 1.

Timeline of key policies and strategies for CAMHS

| Policy/strategy | Year |

|---|---|

| Every child matters | 2003 |

| NSF | 2004 |

| CAMHS review | 2008 |

| Governmental response to CAMHS review | 2010 |

| Talking therapies: a 4 year plan | 2011 |

| No health without mental health | 2011 |

| Implementation framework for no health without mental health | 2012 |

CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service; NSF, National Service Framework.

While the 2003–2004 period was associated with an increase in dedicated funding (the CAMHS uplift), which was maintained through 2005,4 in 2010–2012 funding decreased.18 Figure 1 shows that both, however, were associated with an increase in service activity of all types. It also suggests that younger age bands have smaller increases than older ones, and this is confirmed by the tests for parallelism (for inpatients and day patients, χ2=539.27, DF=4, p<0.001; for outpatients, χ2=18 341, DF=14, p<0.001).

The effect of ‘Every Child Matters’

The associations between CAMHS activity and capacity following the implementation of ‘Every Child Matters’ are displayed by CAMHS mapping age band in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Associations between CAMHS activity and capacity 2003/2004–2008/2009. CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service.

The first chart in figure 2 displays the association between CAMHS capacity, measured by CAMHS Mapping data, and CAMHS activity, from HES data. Between 2003 and 2005 (when the CAMHS uplift was in place), there was an increase in capacity and activity, but between 2005 and 2008 change in capacity varied by age band, while capacity continued to increase. Comparing a mixed-effects Poisson model including the interaction between CAMHS uplift and age, with one without, strongly supported the former (χ2=14.76, DF=4, Pr=0.005). The results did not require adjustment for overdispersion (χ2=2.11, DF=20, Pr>0.99). Actual and predicted funding were initially included as predictors, but were not found to significantly improve model fit, even when their non-linearity was modelled.

The second chart provides an alternative display of the data, reporting the ratio of the HES activity and CAMHS mapping capacity disorder as an aggregate average number of units of HES activity per CAMHS mapping-identified patient per year. It can be seen that the oldest children showed an increase in this metric between 2003 and 2005, whereas for the youngest the increase occurred between 2005 and 2008.

Medical opinions on children aged 0–4 years

In 2012, psychiatrists who confirmed that their services saw children aged 0–4 years were asked if they had noticed any change in the rate of referrals of these children to their services, their answers being on a 5-point scale, with a midpoint of ‘no change’. A total of 338 responded to the question: 279 working in services they considered ‘generic’ and another 59 in specialist services. For each group, the mode of the response distribution centred on ‘no change’, with no detectible bias (d'Agostino test for skew: generic respondents' skew=−0.23, z=−0.93, p=0.35; specialist respondents' skew=−0.41, z=−0.85, p=0.4).

However, consistent with the HES activity data, respondents working in either generic or specialist teams reported low referral levels: 73% of respondents from specialist teams and 93% from generic teams reported receiving no more than four referrals monthly in children aged 0–4 years.

The survey identified 30 respondents who reported their services had stopped seeing children aged 0–4 years. Their reasons are given in table 2 (one respondent gave more than one answer).

Table 2.

Reasons given for stopping seeing children aged 0–4 years

| Reason | n | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient resources available after meeting other demands | 12 | 40 |

| Inappropriate/inadequate skills or facilities available to team | 7 | 23 |

| Externally (management) imposed policy | 6 | 20 |

| Appropriate non-CAMHS service available | 6 | 20 |

CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service.

Resourcing and prioritisation was the most frequently reported reason for terminating CAMHS services to children aged 0–4 years. Thirty-four per cent of the survey's respondents, who reported working in teams which accepted children aged 0–4 years, reported that they thought CAMHS should stop seeing them. There was a relative excess of such respondents working in teams where they reported that prioritisation and resourcing of children aged 0–4 years was low, and a complementary excess of those who thought children aged 0–4 years should be seen, working in teams where they reported high prioritisation and resourcing for this group: this was significant (κ=0.15, z=2.17, p=0.02).

Discussion

The role of prioritisation in policy

The results show that, as hypothesised above, policy initiatives incentivise service activity, even when additional resources are not made available. This is shown not only in changes in overall activity, but also in how these changes differ across the age bands. Tables 3 and 4 identify the targets set in the 2004 National Service Framework and the overlap between those and the recommendations of the 2008 CAMHS service review.

Table 3.

2004 NSF markers of good practice (targets)

| Marker | Priority | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sufficient knowledge for all child staff | |

| 2 | Agreed protocols for referral, support and early intervention | |

| 3 | Flexible provision of services | |

| 4 | Capacity for rapid emergency response | Yes |

| 5 | Meet needs of 16–17 year olds | Yes |

| 6 | Meet needs of learning disabled children | Yes |

| 7 | Joint planning between health, education and social services | |

| 8 | Adequate multidisciplinary team staffing | |

| 9 | Appropriate setting for inpatient MH treatment | |

| 10 | Care Programme Approach for inpatient discharges and child–adult transfers |

MH, mental health; NSF, National Service Framework.

Table 4.

Recommendations from the 2008 CAMHS review and overlap with NSF markers of good practice

| Recommendation | NSF | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sufficient knowledge for children, parents, carers and all staff | 1 |

| 2 | Right to assessment if needed | No |

| 3 | Vulnerable children should have their mental health routinely assessed | No |

| 4 | Youngsters approaching 18 in CAMHS contact should have clear care plans for transition | 5 |

CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service; NSF, National Service Framework.

Although work with children aged 0–4 years is included in target 2 of the 2004 NSF, the prioritised targets focus on older teens. This is specifically identified in target 5, and implicitly in target 4, as older children are more likely to present as psychiatric emergencies, for example, with self-harm or psychosis. This focus is continued in recommendation 4 of the CAMHS review, which underpins the current initiative. Therefore, the differences in change in service activity across the age bands follow the prioritisation set by the policies.

The impact of prioritisation becomes clearer when service activity and capacity are considered together. When dedicated funding is available, capacity and activity increase. However, when the increase in funding stops, capacity drops in the youngest age band but continues to increase in the oldest (the other bands being intermediate). So, those children aged 0–4 years who are still in the service are being seen more frequently than before, as shown in chart 2 in figure 2. If one presumes that more severely affected children will be seen more frequently, then this is an indicator of either increasing severity in the patients, or rising thresholds for entry to the service. The former effect (of increasing severity) can also be seen in children aged 15–18, with increasing frequency of contact between 2003 and 2005 as well as increasing capacity, when CAMHS took over the care of children who had previously been seen in adult mental health services, for example, those with psychosis. As there is no equivalent change in service requirements for children aged 0–4 years, and capacity has fallen, the frequency change suggests threshold elevation is part of a rationing process, when funds for expansion are not available. This contrasts with the maintenance of service capacity relative to activity for the older children. The questionnaire data, collected in 2012, also report prioritisation having this effect, as shown in the table of reasons for CAMHS services no longer seeing children aged 0–4 years. The significant association among priorities, resources and child psychiatrists' opinion of whether CAMHS should provide 0–4 services is consistent with the paper's hypothesis that resourcing and policy initiatives incentivise at an individual level: overall, only 28% of respondents considered that CAMHS should not see this age range, and the majority opinion is consistent with the literature.11

The relationship between funding policy and practice

Funding appears to moderate the relationship between policy and practice. When dedicated funding is present, prioritised targets are resourced more than non-prioritised targets, but in its absence, prioritised targets are preserved at the expense of non-prioritised ones, with capacity being reduced by informal threshold changes. Between 2011 and 2012, the number of 0–4 first appointments given dropped by 229. Divided across the country, this would be very hard to observe at the clinic level, despite it being a 23% drop. So, as the questionnaire results suggest, this may occur without sustained awareness of those making these decisions. These findings may seem surprising. There can be no doubt that, at its lower extreme, funding must mediate between service delivery and policy, as the former requires funding to exist. However, if the bulk of routine (ie, unspecified) funding goes simply on maintaining service organisations, then meeting priorities when funding does not match expectations will require resource movement towards those priorities. If additional funds are not available, then those areas that are not prioritised will lose support.

Limitations

Possibly the most important limitation is the lack of service capacity data beyond 2008. This would have enabled a test of the hypothesis developed above, from the 2003 data. On the figures available, it is impossible to tell whether the increase in service activity from 2009 to 2010 reflects negative results of threshold changes, for example, an increase in re-referrals due to a larger number of inappropriately foreshortened treatments, or improvements in CAMHS activity resulting from novel policy-related changes, for example, Increasing Access to Psychological Treatments for Children and Young People (CYP IAPT).2 However, this does not modify the interpretation of the age-related differences in service activity in 2010–2012 as being related to service prioritisation.

The CAMHS Mapping and HES data, being collected separately and at different times, will have different denominators, errors and missing data patterns, despite referring to the same patients. Thus, the ratios reported in chart 2 in figure 2 are proxy, rather than direct estimators of how much activity patients actually receive. However, these differences are independent of year and age band, and the reported relationship was also tested by mixed methods ANOVA, which explicitly modelled their separate errors. This objection does not, therefore, undermine the threshold-rationing hypothesis they are used to illustrate.

Inpatient and outpatient service activity data are measured using different metrics, as pointed out above. Unfortunately, inpatient and outpatient data were not consistently separated in the CAMHS mapping data. Sensitivity analyses were therefore undertaken for children aged 0–4 years, where the pattern was strongest, comparing the results for separated and combined HES data. No significant difference was found in the results (as might be inferred from figure 1), so the inpatient and outpatient data were combined for the 2003–2008 analyses.

Much mental health support is given to children by many services across public and voluntary sectors.20 This study cannot explore the impact of policy changes across all those other organisations, but, as CAMHS is tasked and skilled to deal with the most difficult mental health problems children present, policy-based difficulties in accessing CAMHS are likely to affect the most disabled children and have the most severe costs for society as a whole.21

Conclusions

These results suggest that target prioritisation and funding focus moderate the likelihood of policy initiatives affecting service delivery. Prioritisation through policy, while being effective in ensuring that service delivery meets urgent targets, carries the potential to damage those targets that may be just as important, but less urgent. This could be effectively managed by ensuring that prioritisation is time limited, with other targets being newly prioritised when sufficient progress has been made. There is also a clear need to associate prioritisation with dedicated funding: without this, policymakers risk shrinking important services to meet priority needs which, while urgent, may contribute less in the long term. These simple recommendations could ensure that the current CAMHS investment strategy fully meets its expectations. In England, routine, independent monitoring of activity and capacity will be provided by the Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS),22 so enabling real-time detection of the threshold changes associated with informal rationing, and thus indicating when prioritisation will need adjusting. Surveys of service descriptions and designations, which were previously used to evidence policy progress,5 are insensitive to quantitative service-level outcome changes, as shown above. The medical research community is used to specifying and using quantitative end points and stopping criteria as a part of the evaluation of new interventions. This study indicates the risks of ignoring such criteria when then new intervention is a policy: improvements in health informatics, such as MHSDS, may allow the application of such techniques to policy evaluation, so improving their outcome.

Footnotes

Funding: The Royal College of Psychiatrists' Child and Adolescent Faculty Executive funded the preparation of the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) by the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The HSCIC process included ethical obtaining ethical approval from HSCIC.

Data sharing statement: The CAMHS Mapping data are in the public domain. The author is, with the agreement of HSCIC, happy to provide the HES data on request. Not all the questionnaire data have been published here, but the author is happy to provide additional information about the questionnaire, and non-identifiable data collected through it, on request.

References

- 1.King's Fund. Has the government put mental health on an equal footing with physical health? Kings Fund. 2015. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/verdict/has-government-put-mental-health-equal-footing-physical-health (accessed 31 Oct 2015).

- 2.Department of Health, NHS England. Future in mind—promoting, protecting and improving our children and young people's mental health and wellbeing—childrens_mental_health.pdf. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414024/Childrens_Mental_Health.pdf (accessed 31 Oct 2015).

- 3.Chief Secretary to the Treasury. Every child matters. HM Treasury, 2003. https://www.education.gov.uk/consultations/downloadableDocs/EveryChildMatters.pdf (accessed 6 May 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stella Charman. Mental health services for children and young people: the past, present and future of service development and policy. Ment Health Rev J 2004;9:6–14. 10.1108/13619322200400014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appleby L, Shribman S, Eisenstadt N. Report on the Implementation of Standard 9 of The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services. London: Department of Heath, 2006. http://www.bipsolutions.com/docstore/pdf/15001.pdf (accessed 25 Mar 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department for Education. Effectiveness of Child and Adolescent Mental Health (CAMHS) services: December 2010. GOV.UK, 2010. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/effectiveness-of-child-and-adolescent-mental-health-camhs-services-december-2010 (accessed 31 Oct 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Children's Services Mapping Data, 2006-2009. CKAN Research Data Discovery Service. http://ckan.data.alpha.jisc.ac.uk/dataset/6850 (accessed 30 Jul 2016).

- 8.Taylor SE, Way BM, Seeman TE. Early adversity and adult health outcomes. Dev Psychopathol 2011;23:939–54. 10.1017/S0954579411000411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heckman JJ. Schools, skills, and synapses. Econ Inq 2008;46:289–324. 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2008.00163.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. National Service Framework for Children and Young People and Maternity Services—The Mental Health and Psychological Well-being of Children and Young People (CAMHS Standard, National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services). 2004. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/199959/National_Service_Framework_for_Children_Young_People_and_Maternity_Services_-_The_Mental_Health__and_Psychological_Well-being_of_Children_and_Young_People.pdf (accessed 6 May 2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Foreman DM. Psychiatry in public mental health: easy to say, but harder to achieve. Br J Psychiatry 2015;207:189–91. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.158907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacob BA, Levitt SD. Rotten apples: an investigation of the prevalence and predictors of teacher cheating. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2003. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9413 (accessed 1 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferraz C, Finan F. Electoral accountability and corruption: evidence from the audits of local governments. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009. http://www.nber.org/papers/w14937 (accessed 1 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fryer RG. Teacher incentives and student achievement: evidence from New York City public schools. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2011. http://www.nber.org/papers/w16850 (accessed 1 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fryer RG Jr, Levitt SD, List JA. Parental incentives and early childhood achievement: a field experiment in Chicago heights. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015. http://www.nber.org/papers/w21477 (accessed 1 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health and Social Care Information Centre. Hospital Episode Statistics. 2012. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hes (accessed 5 May2015).

- 17.Health and Social Care Information Centre. Costing. 2015. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/casemix/costing (accessed 5 May 2015).

- 18.Burnham A, Lamb N. Mental health services: children: written question—218865. UK Parliam. http://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-question/Commons/2014-12-16/218865/ (accessed 2 Nov 2015).

- 19.Young Minds. CAMHS policy in England. http://www.youngminds.org.uk/training_services/policy/policy_in_the_uk/camhs_policy_in_england (accessed 5 May 2015).

- 20.Madge N, Foreman D, Baksh F. Starving in the Midst of Plenty? A study of training needs for child and adolescent mental health service delivery in primary care. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008;13:463–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott S, Knapp M, Henderson J et al. . Financial cost of social exclusion: follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. BMJ 2001;323:191 10.1136/bmj.323.7306.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health and Social Care Information Centre UK. Mental Health Services Dataset. 2015. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/mhsds (accessed 30 Mar 2016).